ABSTRACT

How has Russia been studied by political scientists, economists, and scholars in cognate fields who publish in specialized area-specific and top disciplinary journals? To systematically analyze the approaches employed in Russian studies, I collected all publications (1,097 articles) on the country from the top five area studies journals covering the territories of the former USSR, the top 10 journals in political science, and the top five journals in economics from January 2010 to January 2022 and classified them based on the methods they utilized, empirical focus, and sub-fields within method. In this article, I discuss the results of this classification and the pitfalls associated with over-reliance on some methods over others, notably those that include self-reported data, in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the repressive domestic environment under Putin’s autocracy. I also propose some ways of addressing the new realities of diminished access to data and fieldwork.

Introduction

How have political scientists, economists, and scholars in cognate fields who publish in specialized journals studied Russia over the past decade? In what way do academic outlets differ when it comes to the methods employed in the accepted submissions? These questions are non-trivial. Area-specific journals influence how we think about Russia and indeed political processes across a wide variety of settings outside the narrow field of inquiry, but they are not as widely read by scholars outside of the sub-field. Top disciplinary journals have a stronger emphasis on shaping our knowledge about institutions, regimes, and social, political, and economic actors in a variety of contexts going beyond a single country. They enjoy wider readership and often have a higher impact factor than do the “area” outlets. The top disciplinary journals communicate to the “outside world”; their findings in important ways shape the wider political science knowledge about “big” processes and outcomes such as autocratic resilience, civil society, protest, or democratic/ autocratic impulses.

Method

To analyze the methods deployed in studies of Russia, I collected the titles, abstracts, and texts from all the publications in the top five area studies journals covering the post-Soviet space (), the top 10 journals in political science, and the top five journals in economics from January 2010 to January 2022 (). Drawing on these data and applying automated and manual search techniques, I selected the publications that focus on Russia as part of a small (n < 6) sample or that have a single-country focus.Footnote1 The collection of publications that I review here comprises 1,097 research articles and does not include book reviews and editorial notes. Using keyword searches as well as skimming through all the texts of the publications, I coded the articles by the method employed (quantitative and qualitative), empirical focus (single country or small-n, temporal and geographical domain), and sub-fields within a method.

Table 1. Publications in top area studies journals covering the former USSR.

Table 2. Publications in top disciplinary journals.

Results

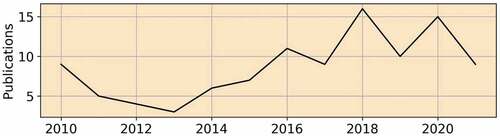

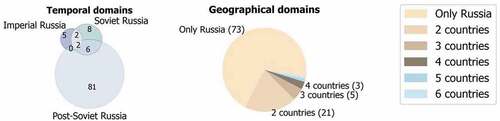

The analysis of the data reveals several interesting patterns. First, although Russia has been widely covered by area studies journals over the past decade (), a relatively small proportion of papers in top disciplinary political science and economics journals have featured the country. While academic interest in Russia has slightly increased after 2014 (), research on the country has been relatively scarce. Despite the country’s salient role in the global political and economic landscape and extensive coverage in mass media, academic publications on Russia account for less than 1% of all the articles in top disciplinary journals. By way of comparison, China, another relatively closed autocracy, features as the main case in 287 articles, which amounts to 2.6% of all publications (). There are 89 publications that feature Russia (i.e. that are either exclusively focused on post-Soviet Russia or deal with post-Soviet Russia) in top disciplinary journals covering the post-Soviet period. Not all publications that study Russia are country-specific. Of 104 research articles, 73 are focused on Russia exclusively, 21 address the country through studies that cover two geographical regions, and the remaining 10 publications analyze Russia as part of a sample of three to six country-cases ().Footnote2

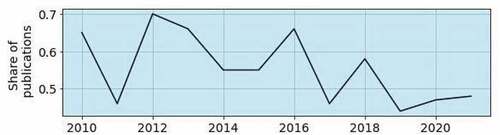

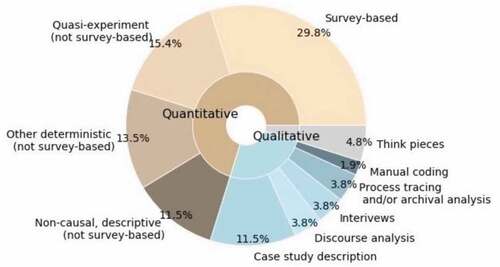

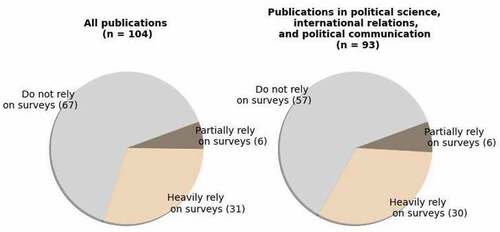

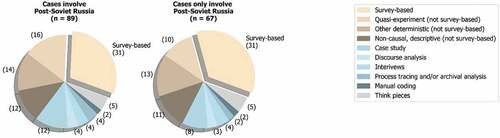

Another pattern that the exercise reveals is that a large proportion of the research on Russia published in top disciplinary journals relies on surveys. Of 104 studies, 31 (29%) draw on surveys as the main research method (heavily rely on surveys) and 6 (6%) use survey data supplementarily (partially rely on surveys) (). This reliance is particularly strong in publications that focus on politics and the economy in post-Soviet Russia, with 41% of the articles being survey-based (). The tendency is most prevalent in studies in political science, international relations, and political communication, with 30 articles (32%) employing survey information within quantitative tests such as regressions, Bayesian analysis, or dyadic comparisons, and 6 (6%) providing survey data as descriptive evidence (). Among the 11 articles published on Russia in economic journals, only one draws on surveys (). The number of publications that rely on surveys has increased slightly over time ().

Table 3. Survey-based publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals.

Figure 3. Publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals: methods.

Figure 4. Publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals: reliance on surveys.

Figure 5. Publications on Post-Soviet Russia in top disciplinary journals: methods.

Figure 6. Changes in number of survey-based publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals over time, 2010–2021.

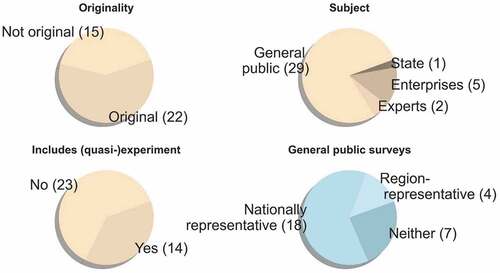

Among the papers in top disciplinary journals that rely on surveys, a large share, 22 (59%), are based on original author-commissioned data (). These predominantly focus on political attitudes (10 cases), reported behavior of organizations (5 cases),Footnote3 and individual-level political behavior (3 cases). The papers relying on externalFootnote4 surveys likewise analyze political attitudes (8 studies) and, in addition, address reported political behaviour (2 studies) and individual-level views on ethnic groups (2 studies). When it comes to the subjects, most studies survey the general public (29; 78%) (). Over half of these general public surveys – 18 (62%) – are nationally representative, while four (14%) are region-representative. The remaining seven (24%) address various subgroups such as individuals within one geographical area, an online audience, or university students.

Figure 7. Surveys employed in publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals.

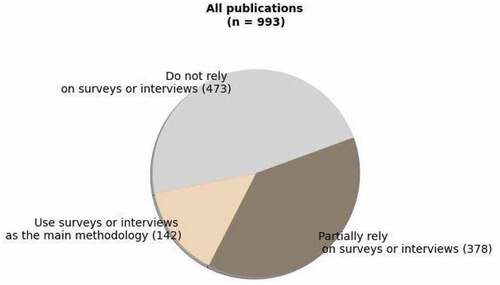

The reliance on self-reported individual-level information takes a different form among the publications on Russia in area-specific journals ( and ). Among 993 articles, 142 (14%) draw on surveys and interviews as the main method to collect data, with survey (list) experiments and quasi-experiments featuring in only 10 articles. However, a larger proportion of studies refer to self-reported data as supplementary information to corroborate their arguments and to introduce social context. In total, 520 articles (53%) in the data set refer to surveys or interviews (). When it comes to commissioning research firms, the Levada Center (Levada Analytical Center), a non-governmental research organization that conducts regular monitoring of Russian public opinion, has been the most popular and respected survey firm among the scholars (Frye Citation2022, 54), with 247 articles referring to the studies conducted by the company. VTsIOM, the country’s largest polling agency that had been effectively seized by the state in 2003 (Zygar Citation2016, 54), is referenced by 84 publications, whereas FOM, the Public Opinion Foundation controlled by the Presidential Administration of Russia, is the third-most popular and is referenced in 62 publications.

Table 4. Survey-based publications focused on Russia in area studies journals.

Figure 8. Publications on Russia in area studies journals, reliance on surveys.

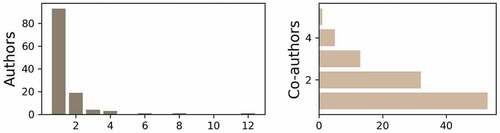

Heavy reliance on surveys is unlikely to be the result of the field being monopolized by a certain author or research team (). For instance, in top disciplinary journals, the range of authors covers a relatively large pool that includes 123 unique names. On average, one academic article is authored by 1.74 (SD = 0.92) scholars; 53 articles are solo-authored, 32 are co-authored by a group of two researchers, and the remaining 19 are co-authored by larger groups ranging from three to five members. The most-published scholar has co-authored 12 articles, the second- most-published contributed to eight publications, and the third-most-published author has co-authored six articles. Most authors (93 of 123) have co-authored only one academic article in the data set.

Figure 9. Publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals: authorship.

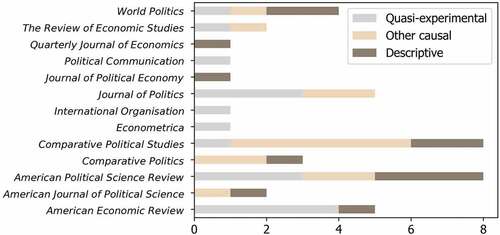

Among the publications in top disciplinary journals that do not heavily rely on surveys, statistical analysis of economic, demographic, or legal indicators is the most popular umbrella methodology (). Deterministic relationships between variables are explored in 30 studies (71%), and 12 (29%) publications analyze correlation rather than causation (). Among the studies that scrutinize causal links, 16 employ rigorous quasi-experiential techniques such as regression discontinuity design, instrumental variables estimation, matching, two-stage least squares regression analysis, or Granger causality tests. The remaining 14 publications study causal links using alternative approaches.Footnote5 These numbers provide quantifiable evidence in support of the argument that Alexander Libman (Citation2023) makes in his contribution to this special issue: that contemporary computational researchers in Russian Studies aim to focus on causal identification rather than simply reporting correlational evidence.

Figure 10. Publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals that do not heavily rely on surveys and primarily rely on quantitative methods.

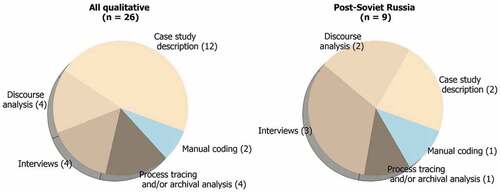

When it comes to non-computational approaches in Russian studies in top disciplinary journals, the prevailing research method that does not heavily rely on surveys is in-depth qualitative examination of a particular case. This approach is used in 12 articles (). Most of these case-study-based publications do not feature within-case analysis and address cohorts of two (five publications), three (two publications), four (two publications), or five (one publication) countries, with two publications focusing on Russia exclusively. Among the articles that are focused exclusively on Russia, interviews are the most popular method. Additionally, a portion of the publications does not involve any empirical analysis. Out of the 89 papers that include analysis of post-Soviet Russia, five (6%) offer an overview of the political landscape or develop theories about current affairs without qualitative or quantitative tests.

Figure 11. Publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals that do not rely on surveys and primarily rely on qualitative methods.

The situation is different in the studies in area studies journals, with 548 (55%) publications drawing purely on qualitative approaches without relying on any empirical tests and 229 (23%) using a combination of qualitative methods and descriptive statistics; the reliance on purely qualitative methods slightly weakens over time (). However, even in this context, many papers use self-reported information: 154 (28%) of the articles that deploy purely qualitative methods cite surveys and interviews to provide context. Among quantitative methods employed in field-specific journals, regression analysis is the most popular (216 articles); 11 articles use quasi-experiential (experiential) methods, which are, again, primarily based on the analysis of the self-reported information.

Discussion and conclusions

To summarize, publications on Russia in top disciplinary journals in political science and economics are fewer in number compared to those on other large global players and autocracies such as China; they heavily rely on quantitative methods and widely use surveys and, somewhat less often, interviews. Publications on Russia in area-specific journals primarily rely on qualitative methods but still frequently cite surveys and interviews, using them as additional sources of information rather than as the main method for data collection and analysis. In other words, self-reported individual information is an important source of data for Russian studies. In light of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the deepening of repression in Putin’s autocracy, these patterns present challenges for further research.

As the other contributors to this volume note, new realities invite a discussion of new ways to conduct surveys in repressive environments and a shift towards a more eclectic range of methods. One concern is that little is known about the extent to which self-reported data used in research on Russia are altered by self-censorship and social desirability bias. Previous studies suggest that under perceived social pressure, individuals tend to misrepresent preferences (Kuran Citation1997; Zerubavel Citation2006; Berinsky Citation2013). Therefore, in an autocracy that systematically sanctions those who challenge its official discourse, respondents, intimidated by the repressions, may choose to misreport thoughts, opinions, and sentiments concerning, for instance, Russia’s war against Ukraine. In their contribution to this special issue, Reisinger, Zaloznaya, and Woo (Citation2023) discuss how the fear of punishment drives survey misreporting. However, thus far, this important issue has not been very widely discussed in the past studies that have relied on surveys from Russia.

Another concern is that the degree to which survey and interview data are distorted by non-response bias is also uncertain. While scholars propose ways of partially capturing these gaps,Footnote6 the authors mostly discuss non-response to certain questions within a survey and pay less attention to the cases in which respondents refuse to participate in a survey at all, which may be critical in the society where laws prohibit references to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as “the war,” instead prescribing calling it a “special military operation.” Indeed, full non-response is common in Russia. Even before the war, Levada Center reported that 57% of the population almost never participate in surveys, 39% participate occasionally, and only 3% take part in opinion polls systematically (Levada Center Citation2020). Since the latter estimates were obtained from individuals who have agreed to respond to a survey at least once, it is reasonable to expect the actual non-response rate to be even higher, perhaps even more so since February 2022. At the same time, it remains unclear if the propensity of an individual to hold certain opinions and beliefs correlates with their predisposition to respond to pollsters. Unfortunately, studies that rely on surveys from Russia rarely discuss what these technicalities mean for broader research findings.

A third concern is that little is known about the credibility of survey organizations in present-day Russia. The major polling institutions VTsIOM and FOM are directly state controlled and, therefore, likely to only release information that facilitates regime survival (Zygar Citation2016, 54; Guriev and Treisman Citation2022, 199). As to private polling institutions, the Russian state presently has enough power to shut down, sanction, declare as a foreign agent, or harass any company that does not align with the regime. However, researchers employing these data rarely acknowledge the role of the state as an ultimate gatekeeper when it comes to public opinion surveys.

Fourth, national and region-representative surveys offer little information about the social groups that may be of particular interest to scholars from the point of view of understanding the motivations underlying popular support for (or challenge to) Russia’s war against Ukraine and Russian autocracy. For instance, a typical sample for a nationally representative survey is created based on respondents’ geographical location, gender, education, and age; it purposefully excludes army soldiers and individuals from remote territories or small settlements (Levada Center Citation2022). Therefore, the opinions, thoughts, and beliefs of hard-to-reach individuals from specific groups such as the military, potential protestors, or the elites are rarely scrutinized if aggregate surveys are used as the main method. At the same time, as Tomila Lankina (Citation2023) writes in her contribution to this special issue, paying little attention to marginal people and marginal topics may seriously distort our understanding of the big questions, such as support for democracy, autocracy, and the war. Answering questions like “Who are Putin’s foot soldiers in Ukraine?” and “Who are his police officers who punish anti-war protestors?” requires a knowledge of the deep divisions in society that find their institutional reflection in the machinery of state repression.Footnote7

As Regina Smyth (Citation2023), Vladimir Gel’man (Citation2023), and Tomila Lankina (Citation2023) argue in their essays in this special issue, there is no denying that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 revealed gaps in our collective knowledge. The future sustainability of the field of Russian studies will depend upon its ability to correct past oversights and search for new questions, approaches, data, and methods.

Even though present-day Russia is far from open to social scientists, there is still potential to diversify researchers’ toolkits and thereby not only limit the field’s over-reliance on self-reported individual-level information but also, at least to a certain extent, overcome the obstacles for researchers created by the war and the regime. Essays in this issue illustrate this argument. Alexander Libman (Citation2023) discusses how researchers can use cross-regional variation and bibliographical information to answer questions in political science. Vladimir Gel’man (Citation2023) mentions the opportunity for researchers to use data from social media and surveillance footage. Tomila Lankina (Citation2023) points to the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. To add to these, I suggest some ideas below.

Russian studies can and should take advantage of digital data sets. News archives and mass media data sets analyzed using computerized methods may serve as a source of information about the strategies employed by state propaganda and thereby inform political scientists about the strengths and weaknesses of the regime. The digital platform Yandex Toloka may be used to solve a variety of crowdsourcing tasks with the help of Russian speakers. Telegram channels and groups may help engage with the Russian population without physically crossing the border. And Spark and Integrum databases may help scholars study certain aspects of economic activity in the country. All these alternatives are available to researchers based outside of Russia, yet remain relatively untapped in scholarship that appears in top political science and economics journals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. I selected the articles that contain Russ*, Soviet*, USSR, or Moscow in their titles or abstracts, read their abstracts, and skimmed through the main text to ensure that the publications are Russia-focused.

2. These findings provide a region-specific focus to an ongoing debate about the representation of the single-country studies in top general interest and comparative studies journals. For instance, Pepinsky (Citation2019) argues that single-country research has been under-represented for years, whereas Munck and Snyder (Citation2007) and Schedler and Mudde (Citation2010) find that almost half of the articles published in journals dedicated to comparative politics are single-country studies.

3. Surveys of employees of commercial firms and enterprises.

4. -existing, already available reports.

5. Mostly by providing a qualitative explanation of a causal mechanism.

6. See, for instance, Timothy et al. (Citation2017), Berinsky and Tucker (Citation2006), and, primarily, Reisinger, Zaloznaya, and Woo (Citation2023) in their contribution to this special issue.

References

- Berinsky, Adam J. 2013. Silent Voices: Public Opinion and Political Participation in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Berinsky, Adam J., and Joshua A. Tucker. 2006. “‘Don’t Knows’ and Public Opinion Towards Economic Reform: Evidence from Russia.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 39 (1): 73–99. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2005.12.002.

- Center, Levada. 2020. “Uchastie V Voprosakh I Doverie [Survey Participation and Trust].” Accessed 15 July 2022. http://www.levada.ru/2020/11/13/uchastie-v-oprosah-i-doverie/

- Center, Levada. 2022. “Metodologiya omnibusnogo issledovaniya [Polling Methodology].” Accessed 15 July 2022. http://www.levada.ru/zakazchikam/omnibus/

- Frye, Timothy. 2022. Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gel’man, Vladimir. 2023. “Exogenous Shock and Russian Studies.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39(1–2): this issue.

- Guriev, Sergei, and Daniel Treisman. 2022. Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kuran, Timur. 1997. Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lankina, Tomila. 2023. “Branching Out or Inwards? The Logic of Fractals in Russian Studies.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39(1–2): this issue.

- Libman, Alexander. 2023. “Credibility Revolution and the Future of Russian Studies.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39(1–2): this issue.

- Munck, Gerardo L., and Richard Snyder. 2007. “Debating the Direction of Comparative Politics: An Analysis of Leading Journals.” Comparative Political Studies 40 (1): 5–31. doi:10.1177/0010414006294815.

- Pepinsky, Thomas B. 2019. “The Return of the Single-Country Study.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 187–203. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051017-113314.

- Reisinger, William M., Marina Zaloznaya, and Byung-Deuk Woo. 2023. “Fear of Punishment as a Driver of Survey Misreporting and Item Non-response in Russia and Its Neighbors.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39(1–2): this issue.

- Schedler, Andreas, and Cas Mudde. 2010. “Data Usage in Quantitative Comparative Politics.” Political Research Quarterly 63 (2): 417–433. doi:10.1177/1065912909357414.

- Smyth, Regina. 2023. “Plus Ça Change: Getting Real about the Evolution of Russian Studies after 1991.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39(1–2): this issue.

- Timothy, Frye, Scott Gehlbach, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Ora John Reuter. 2017. “Is Putin’s Popularity Real?” Post-Soviet Affairs 33 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2016.1144334.

- Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2006. The Elephant in the Room: Silence and Denial in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zygar, Mikhail. 2016. All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin. New York: PublicAffairs.