?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

What sort of military assistance has Ukraine received to date from North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members since 2014? What has driven NATO allies’ decisions to provide military assistance to Ukraine? This essay addresses both questions. It offers a preliminary examination of how strategic, economic, and risk considerations might have shaped NATO members’ decisions regarding arms transfers to Ukraine, a country that remains outside of the Alliance but nevertheless is an Enhanced Opportunities Partner. Using both a qualitative analysis of post-2014 assistance and a purpose-built dataset combining military aid to Ukraine since late January 2022, we find that prior strategic preparation in the form of investments in military readiness and infrastructure is strongly associated with military aid to Ukraine. Economic considerations and prominent risk factors such as fossil fuel dependency thus far have not.

Since Russia first seized Crimea from Ukraine and destabilized the Donbas region in 2014, a major question confronting European and North American decision-makers has been whether to provide military assistance to Ukraine and, if so, what sort. This policy debate intensified when Russia massed its military forces near Ukraine in 2021 and then launched its full-scale invasion – the so-called “special military operation” – of that country on 24 February 2022. The official Russian position on the Western armament of Ukraine has been straightforward. In a December 2021 interview, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov asserted that Western military support has made Kyiv believe that it has “carte blanche for a military operation” in the Donbas (RIA Citation2021). Throughout 2022, Moscow warned repeatedly that military assistance for Ukraine presented a major escalation risk, with the shipments themselves liable to Russian interdiction. Despite Moscow’s rhetoric, NATO members continue to send weapons to Ukraine.

Russian protests of Western arms transfers to Ukraine raise two questions. First, what sort of military assistance has Ukraine in fact received to date from North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members? Second, what has driven NATO allies’ decisions to provide military assistance to Ukraine? Providing military assistance allows NATO allies to signal support to Ukraine and to complicate Russian war-making. Yet scholarly discussion on military assistance to Ukraine remains absent, with little analysis of who provides what sort of military assistance and how much of it over time. This silence is peculiar, not least because states could conceivably use arms transfers to substitute for certain types of alliance commitments (Yarhi-Milo, Lanoszka, and Cooper Citation2016).

This essay assesses how much and what kind of military assistance that NATO allies have given to Ukraine since 2014 and considers some preliminary evidence as to why. The first part defines key terms, explains how alliances and arms transfers relate to each other, and reviews the strategic, economic, and risk considerations that shape decisions to transfer arms. The second part summarizes what Ukraine has received between 2014 and January 2022, examining how those considerations have influenced members’ decisions about transferring arms to Ukraine over time. The third part leverages greater data and regression analysis to explore whether those considerations might still shape military aid in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. One hypothesis we explore here is that states’ propensity to provide military aid to Ukraine depends largely on their previous investments in military readiness and infrastructure. We compiled and used a small, purpose-built dataset consisting of qualitative scores of military support for Ukraine before February 2022, continuous variables capturing aid relative to national wealth gathered by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, and theoretically relevant covariates that help evaluate what factors might be driving states’ choices to support Ukraine militarily. Because February 2022 marks a critical juncture in the war given the heightened intensity of the violence involved, we divide our analysis of arms transfers to gain a pre- and post-2022 picture of arms transfers.

Neither causal nor definitive, our findings are suggestive. To summarize, risk considerations initially tempered strategic ones. Even the strongest supporters of Ukraine have articulated concerns about escalation and so calibrated their tactical and operational support for Ukraine accordingly. Nevertheless, risk considerations were already waning by the time Russia began its military build-up near Ukraine in 2021. In the months after Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, the only variable that has correlated positively with military support is a country’s previous preparation in the form of investments in military readiness and infrastructure: states’ propensity to aid Ukraine militarily in 2022 has depended largely on their previous investments in military readiness and infrastructure. Indeed, economic vulnerability, at least in the form of fossil fuel dependency, has hardly dampened contributions. This finding is surprising: its persistence would reflect a strategic advantage for NATO in that a perceived source of leverage for Russia has not had the desired effect. As time passes, allies are likely to find alternatives to Russian fossil fuels, further mitigating the risk of energy blackmail. The conclusion outlines directions for future research.

Alliances and arms in theory

Below, we define key terms and discuss how alliances and arms relate to one another. We then examine the factors that determine how arms transfers convey commitment.

Alliances and arms: definitions and concepts

A defensive military alliance is a formal arrangement of two or more states that wish to coordinate their defense policies to some extent in view of a shared threat or security challenge. A state may desire a written commitment – specifically, an alliance treaty – from others, thereby engaging their reputation lest they decide not to fulfil their promises to provide military support when needed (Morrow Citation2000). Alliance treaties allow signatories to convey domestically and internationally their seriousness in strengthening their military ties. These treaties arguably raise the likelihood of receiving assistance in case hostilities break out with an adversary. Accordingly, scholars describe alliances as being ex post costly (Fearon Citation1997, 70). Signing an alliance treaty may mean few immediate costs, but – notwithstanding the destructiveness of war – reneging on it carries risk of reputational damage that might, at the very least, hamper future efforts at eliciting international co-operation.

Treaty alliances vary in their conditionality and precision. Imprecise treaties without conditions imply a broad alliance commitment that covers many different security contingencies. Blanket provisions of aid are often unattractive to give because of moral hazard (Benson Citation2012). A recipient of a broad commitment could become more aggressive, believing that the alliance would shield them from the costs of their actions. This behavior – which Lavrov described in his December 2021 RIA interview – could produce what scholars call entrapment if other members of the alliance find themselves, to their dismay, embroiled in the conflicts instigated by that recipient (Kim Citation2011). To minimize these risks, negotiators of an alliance treaty might insist on conditions or precise language that clarify the limits to the commitment, whether over its geographical scope or conflict participation. If the commitment becomes too narrow, however, the recipient may start feeling anxious about whether it will receive any alliance support (Snyder Citation1997). Such anxieties over abandonment may grow with time as threat perceptions diverge, priorities change, and capabilities relative to those of the adversary worsen.

In Ukraine’s case, the only military alliance mooted is NATO, a multilateral alliance comprising the United States and, as of 29 November 2022 other countries. Although Washington endorses Kyiv’s aspirations for NATO membership, it has never offered a bilateral treaty in its stead. At first glance, a NATO commitment seems broad: according to Article 5 of its founding treaty, an attack against any member would be construed as an attack against the entire Alliance. However, nothing in Article 5 guarantees any particular response, enabling allies to determine and to take “such action as it deems necessary” (NATO 1949 [Citation2019]). Because Ukraine is waging a high-intensity territorial conflict with Russia, and still claims legal sovereignty over the Donbas, Crimea, and their adjacent waters, the short-term probability of Ukraine joining NATO remains small. After all, following Russia’s 2014 invasion, NATO members have generally abided by the finding in their 1995 study on enlargement that “[s]tates which have ethnic disputes or external territorial disputes, including irredentist claims, or internal jurisdictional disputes must settle those disputes by peaceful means in accordance with OSCE principles. Resolution of such disputes would be a factor in determining whether to invite a state to join the Alliance” (NATO Citation1995) Of course, these considerations were absent in 2008 when NATO declined to offer a Membership Action Plan to Ukraine (and Georgia). Back then, Russian-Ukrainian relations were cool but not bellicose. In both peacetime and wartime, Ukraine has struggled to join NATO even though it became an Enhanced Opportunities Partner in 2020.

Military assistance is the provision of military hardware, equipment, training, and expertise. It can be gifted, provided with financing,Footnote1 or purchased outright. Theoretically, military assistance can substitute, albeit imperfectly, for alliance commitments, thereby signaling the depth of a security relationship between giver and receiver (Spindel Citation2018). Hypothetically, it could lead to stronger partnerships if given in large quantities (Walt Citation1987, 41). More often, however, military assistance (to include both giving and selling arms) complements alliance commitments (Pamp and Thurner Citation2017; Diguiseppe and Poast Citation2018). Thrall and his co-authors (Citation2020) find that, since 2001, the United States has tended to sell arms to treaty allies. After all, a treaty commitment may implicate the reputation of allies when an adversary acts so aggressively as to trigger the casus foederis (Latin for “case for alliance”), but a treaty alone is generally insufficient to affect the military balance. Even those states that are resolved to fight might need time to mobilize and to deploy their military assets before they can assist an ally under attack. The beleaguered ally might not last long enough before reinforcements can arrive, thus allowing the adversary to achieve a fait accompli. Provided that the receiver can integrate, operate, and maintain imported systems, military aid can improve the receiver’s own capabilities, possibly enhancing deterrence of an adversary and boosting its chances against an initial attack. For NATO members, military assistance can be a more attractive – and cheaper – policy alternative because it avoids direct participation in a conflict.

As an imperfect substitute, military assistance can assume many forms, with varying levels of risk to the giving country and implied level of commitment to the recipient. Oftentimes, military assistance may bear only ex-ante rather than ex-post costs, thereby constituting much weaker commitment devices. Unlike the ex-post costs that attend alliance commitments, ex-ante costs are costs incurred when transaction takes place, with no rational importance for future decision-making. Still, arms transfers can indicate how much a providing state values the recipient’s security: the bigger the arms transfer, the more valuable the relationship. This observation may also be true if arms transfers are institutionalized, and recipients subsequently have expectations that their inventories would be replenished. Abruptly suspending these transfers to a recipient could create a window of opportunity for an adversary to attack. Furthermore, many weapons deliveries take years to negotiate; it can be costly reputation-wise for the giver to suspend a pre-authorized sale. If the intended recipient loses on the battlefield, then the provider may no longer be seen as being “on the winning side” (Yarhi-Milo, Lanoszka, and Cooper Citation2016, 96).

Arms transfers can have different implications for commitment. A standard way to distinguish between arms transfers is whether they are primarily defensive or offensive. Weapons of an offensive character facilitate the attack because they tend to be highly mobile, capable of much firepower, or both (Lieber Citation2008). Defensive weapons lack those characteristics. Accordingly, providing offensive weapons to another country is inherently riskier than providing defensive weapons precisely because the recipient could use those received capabilities to launch an attack against its adversary, providing that the giving state hopes to quell local tensions. The giver may want to avoid getting ensnared in an unwanted conflict with the recipient’s own adversary. However, a state might provide offensive aid because it tolerates those risks, especially if the recipient’s adversary clearly intends on revising the status quo or recouping territory that it might have once controlled in the past. In contrast, offering defensive weapons serves to reassure that adversary that the abiding interest of the giver is upholding the status quo. The provider’s support for the recipient is highly conditional, as revealed by the arms transfer policy. Hence the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), legislated by the U.S. (Congress in Citation1979), specifies that “the United States will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability” (96th Congress Citation1979). The TRA is peculiar: it is institutional (which implies a strong commitment), it is restrictive (which weakens the commitment), and it allows for much discretion (which further softens the commitment) for the US executive.

Although the offense-defense distinction is intuitive, it does not survive scrutiny. Tanks and fighter jets alike can serve either offensive or defense purposes irrespective of their mobility and firepower. Tanks can help break through enemy lines and exploit openings, but they can also reinforce defensive lines and allow the defender to undertake counter-offensive operations against enemy landing zones and lodgments. Fighter jets can suppress enemy air defenses, harass surface ships, and gain local air superiority over enemy territory, but can also defend home air space against enemy aircraft. Many missile types confound the offense-defense distinction. Short-range ballistic missiles – which fly mostly unpowered along a ballistic trajectory of distances between 300 and 1000 kilometers – can hold at risk civilian targets just as much as they can fixed military targets. They may be more valuable against military targets if fitted with those warheads intended to bust bunkers with earth-penetrating warheads or to knock out radar sites with electromagnetic pulse devices. Nevertheless, they might dissuade a potential aggressor from attacking. Even air defense could help cement control over territory taken in a fait accompli and provoke concern over future intentions. Russia’s positioning of air defense assets in Crimea following its annexation is one example (Frühling and Lasconjarias Citation2016).

Problems with the offense-defense distinction notwithstanding, US (and German) decision-makers have used this language. Still, regarding Ukraine, the offense-defense distinction has partly given way to notions of lethality, with political and military leaders emphasizing whether the military aid given to Ukraine (prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion) is lethal. The word “lethality” itself seems straightforward: its common meaning denotes the capacity to kill and to maim. However, its definition has historically evolved, with scientists and engineers casting lethality in terms of how deep bullets penetrate wood, whether bullets could kill a cavalry horse, whether ammunition have stopping power over their target, or the effects of momentum on the human body (Ford Citation2020, 82–86). Nonlethal aid to Ukraine generally covers the provision of night goggles, helmets, hardened computers, first aid kits, winter clothing, and other such gear. In contrast, lethal aid to Ukraine can have clear kinetic effects by encompassing included machine guns, anti-tank weapons, and artillery systems. Sometimes the lethality and offensive-defensive binaries come together, as when the US Department of Defense (2021) declared that a $125 million package for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) “reaffirms the U.S. commitment to providing defensive lethal weapons to enable Ukraine to more effectively defend itself against Russian aggression.”

Factors affecting the use of arms transfers as signals of commitment

Why a state might transfer arms to others can also illuminate the level of commitment made. The international security literature identifies three sets of considerations – strategic, economic, and risk – that influence arms transfer policies, each with its own implications for commitment (Thrall, Cohen, and Dorminey Citation2020). These considerations are not mutually exclusive: strategic considerations might enable the use of arms transfers as a commitment device, but economic and risk considerations could weaken that commitment.

Strategic considerations

States might transfer arms to those with which they share a potential adversary. Arms transfers can allow the recipient to withstand an attack better, thereby enhancing deterrence, curbing the potential for the aggressor to escalate militarily, and reducing the short-term escalation risks and long-term material costs for the donor. Treaty allies and informal security partners will thus be most likely to obtain military assistance. Absent an alliance commitment, states can use military assistance to signal the depth of their security relationship (Spindel Citation2018), which in turn may reflect how closely aligned their threat assessments are.

In Europe, these strategic considerations may be most acute for those countries apprehensive of Russia undermining the European territorial status quo and the political sovereignty of its neighbors. Since 2000, such countries have tended to invest significantly in Operating & Maintenance (O&M) expenditures for their militaries (Becker Citation2017). By covering the costs associated with training, inspection, and repair, these expenditures help ensure that military capabilities are available, kept in good working condition, and have the necessary trained personnel to operate them. Becker and Malesky (Citation2017) found that states whose strategic outlooks were more “Atlanticist” in perceiving the United States as being a central security guarantor in Europe generally spend more on O&M when NATO undertook more “out-of-area” operations in the early 2000s. O&M expenditures enable militaries to train and to deploy, reflecting how much a country uses or expects to use its military instrument to support its foreign policy. The US General Accounting Office (Citation2000, 9) explains that “O&M is directly related to military readiness because it provides funds for training troops for combat and for maintaining tanks, airplanes, ships, and related equipment.”

For Ukraine in 2014, the kinds of military attributes supported by O&M spending were lacking. Just when Russian-backed proxy forces began to agitate in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in early 2014, the Armed Forces of Ukraine (ZSU) was seriously hobbled by the accumulated effect of years of poor training, low readiness, lack of modernization, and equipment shortfalls – all of which were abetted by policies adopted by Viktor Yanukovych during his presidency (Polyakov Citation2018, 100). This moment of weakness allowed agitators in the Donbas to seize control of territory and to defy Kyiv’s authority. Moreover, Russia’s seizure of Crimea meant not only a loss of significant territory for Ukraine, but also a large share of its naval power. Because of the disarray that marked the ZSU at the outset, Ukraine relied on various volunteer battalions to regain territorial control in its so-called “anti-terror operations.” Though highly motivated and ideological, these volunteer battalions lacked discipline and chafed under the leadership of senior military and political leaders. Regular units disobeyed orders, especially after the game-changing Battle of Ilovaisk in August 2014 where Ukraine suffered a major defeat to Russian forces (Cohen Citation2016, 8; Ivanovska Citation2017). That battle effectively halted the progress that Ukraine had been making in its “anti-terror operations.” As then–Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk noted in September 2014, “we can easily [stop, contain, and deter Russia] with the Russian-led guerrillas and the Russian-led terrorists. But it’s too difficult for us to fight against well-trained and well-equipped Russian military (sic)” (quoted in Council on Foreign Relations Citation2014).

For those vested in Ukraine’s success against such struggles, arms transfers have obvious value. Accordingly, the strongest signal of commitment would mean an institutionalized flow of lethal aid that Kyiv could use to bolster its land (and, prior to 2022, naval) forces, possibly allowing it to undertake (counter-)offensive military operations against Russian forces on its territory. An essential qualification here is that Ukraine cannot quickly absorb just any weapons platform it can possibly receive from abroad. Delivery and training may take time. Even if it freely obtained equipment, particularly between 2014 and 2021, Ukraine might still have had to bear the training, operating, and maintenance costs – costs that could have exceeded Ukraine’s fiscal constraints and organizational capacity at the time (Horowitz Citation2010).

Economic considerations

An economic logic might shape a state’s decision to transfer arms. To keep per unit production costs low, to sustain their defense industries, and, simply, to make money, countries provide arms to others in a manner that is not free of charge to others. Arms-producing/exporting states thus should be more likely to invest in and transfer arms, all else equal (Becker Citation2019). Similarly, receiving states covet arms transfers from donors when they can negotiate the ability to engage in joint arms production and so reap domestic economic gains such as increased revenue and reduced local unemployment (Brauer and Dunne Citation2004, 2). Recent research finds that equipment expenditures are less damaging to economic growth than personnel expenditures (Becker and Dunne Citation2021). In either case, the desire to enhance economic growth and economic security underpins arms transfers. Weapons transferred for economic reasons signal weak commitment since the interest of the giver is primarily financial. Because war is costly and risky, the giving state might still limit potential losses by withdrawing whatever support implied by its arms transfers in the face of potential military escalation.

Ukraine might be interested in joint arms production or trade offsets notwithstanding the potential lack of commitment implied here. Before 2014, the size of the Ukrainian defense industry was large enough to put it in the global top ten. Many of its exports were destined for China and countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Russia’s seizure of Crimea, however, meant that Ukraine lost 23 plants and shipyards that had specialized in producing such military hardware as amphibious assault ships. Indeed, Russian Deputy Premier Dmitri Rogozin noted in June 2014 that “Crimea currently has several large ship repair and shipbuilding plants … which were among the largest during the Soviet times. We have already evaluated their potential and have already decided to start production of some of vessels and marine equipment at their facilities this year” (quoted in Lombardi Citation2014, 4). Joint arms production could help Ukraine compensate its loss of defense plants in Crimea and elsewhere, thereby enabling the Ukrainian defense industry to recover from being abruptly ruptured from its pre-war integration with the Russian defense industry (Jacqmin Citation2020, 266–268). Pursuing joint arms production with NATO countries could also mean the transmission of technology and the adoption of certain standards that in turn improve the marketability of the Ukrainian defense industry and modernize the ZSU, thus enhancing its interoperability with NATO militaries. To be sure, Western military aid has sometimes posed problems for Ukrainian defense firms, especially if they feared losing orders. Allegedly because of his ownership stake in a struggling naval yard, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko refused U.S. Island-class patrol boats for several years (Yegoshyna Citation2018). Nevertheless, in 2022, Russia targeted key Ukrainian defense industrial sites. These economic considerations may have been salient for Ukraine between 2014 and 2021, but much less so after Russia’s invasion in 2022.

Risk considerations

Strategic and economic benefits might push states to transfer arms to others, but risk considerations can be a limiting factor, both in terms of what arms, if any, end up being provided, and the level of commitment they might signal. Risk can arise from multiple sources, some of which are inversely related to the foregoing benefits. One is blowback: a friend today may be an enemy tomorrow. Countries may have been uncertain of Ukraine’s future political direction even after 2014. After all, the experience of the 2004 Orange Revolution suggests that Ukraine’s pro-Western alignment may eventually end due to internal intrigues and external interference. Western military aid could be lost to pro-Russian elements. Technological spillover is another source of risk. To prevent unwanted technological transfers, states might not want to offer the most cutting-edge platforms. Even close treaty allies have been reluctant to share sensitive technologies with one another. With Ukraine, a non-treaty partner that has changed geopolitical alignments, has its own large defense industrial base, and exports to China, this reluctance might be strong for some countries.

Military escalation could be another source of risk. The giving state might not wish to tip the balance of power too much in favor of the recipient lest the latter would undertake offensive military operations against the adversary – operations that could end in catastrophic failure or generate pressure for military intervention. Initially, confusion abounded as to Russian intentions, let alone its own role in the unrest in the Donbas, in early 2014. While seizing Crimea, Russia went about nuclear signaling by conducting (pre-planned) intercontinental ballistic missile tests and other exercises involving its nuclear-capable forces (Moore Citation2014). Russia expanded its own direct participation in eastern Ukraine when Ukraine’s successes in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts became more apparent. Some observers argue that the United States and many of its treaty allies have far fewer interests at stake in the crisis between Russia and Ukraine, and only peripheral interests at that (see, e.g. Carpenter Citation2021). Accordingly, too much military assistance to Ukraine could invite a Russian retaliatory response that some wish to avoid.

Other forms of risk exist in the Ukrainian context. Many critics of arms sales highlight human rights concerns. The recipient may use weapons to repress members of its own population or to commit atrocities against civilians. Regarding Ukraine, unease surrounds those far-right groups that have contributed personnel to volunteer battalions. Although far right political parties in Ukraine such as Svoboda gain far fewer votes than the far right Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, the ideological and hyper-nationalist character of such formations as the notorious Azov Battalion has been controversial. Because of the command and control (C2) problems that Kyiv had with such volunteer battalions, especially during the initial phases of the conflict, western governments might be concerned with inadvertently arming these groups (Bukkvoll Citation2019). Indeed, C2 problems were a significant source of risk. In 2014, the Ukrainian constitution left uncertain the precise roles and responsibilities at the executive level of decision-making. Various agencies and ministers often did not coordinate with one another, and so jockeyed to preserve their own resources while jealously guarding their institutional autonomy. In 2014, internal security organizations urgently needed reform given their complicity in the repressive measures undertaken when Yanukovych was still President (Oliker et al. Citation2016, 7–15). These C2 problems had negative implications for receiving military assistance at the time. Different parts of the Ukrainian government were issuing their own, sometimes contradictory requests. Worries abounded that weapons sent to Ukraine would be misused or diverted elsewhere (Oliker et al. Citation2016, 88–92). Worsening matters has been the lack of oversight in defense procurement, which prompted the 2015 Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index to give Ukraine an abysmal grade of “D” (Transparency International Citation2016). To address these issues, NATO has provided significant guidance on Ukraine’s defense sector reform, not least through the Comprehensive Assistance Package (Fasola and Wood Citation2021, 45–47). The controversial Azov Battalion itself became integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard, though debates persist about whether it subsequently became depoliticized (see Colborne Citation2022).

The giving state could tolerate these risks if it is hawkish and has interests that align closely with those of the recipient. Alternatively, it can perhaps leverage its own aid to attenuate those risks by defining the conditions for its use and developing institutional mechanisms to provide oversight and enforcement. They may simply restrict the quality and quantity of what they might provide, and thus weaken the signal of support (Yarhi-Milo, Lanoszka, and Cooper Citation2016). Some countries might feel, however, that their interests are so insufficiently engaged in Ukraine as not to provide anything that could be construed as a commitment. After all, Ukraine’s interest is its own survival; for others, it may be conflict avoidance.

Risk and economic considerations could operate jointly in yet another manner for potential suppliers of military assistance. The European Union has grown more dependent on Russian hydrocarbons to meet its energy needs throughout the 2000s and 2010s. In 2020, for example, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Hungary had the largest share of their energy needs satisfied by Russian imports (Eurostat Citation2022). Germany embraced its reliance on Russian natural gas by approving the Nord Stream 2 project after Crimea’s seizure. These countries might not wish to antagonize Russia on commercial grounds lest it cuts off much-needed gas, oil, and coal in retaliation.

To assess how much weight these strategic, economic, and risk considerations have had for NATO countries, the following sections analyze Western military aid to Ukraine both before and after Russia’s 2022 full-fledged invasion. We first gather non-standardized (across countries) data on pre-2022 military aid, describing which countries chose to provide what types of aid, and outline theoretically grounded possibilities for why they may have chosen to do so. We then encode those data into an ordinal variable grouping states into six rank-ordered groups ranging from “first-tier” (scored as 5) to “absent” (scored as 0). This coding enables us to conduct a multivariate regression analysis that compares the relationship between this outcome variable and a theoretically driven battery of independent variables, on the one hand, with the relationship between a continuous variable capturing post–February 2022 aid as a share of national GDP (Antezza et al. Citation2022; Kiel Institute for the World Economy Citation2022) and that same battery of independent variables, on the other.

Ukraine and military assistance prior to 2022: who gave what and why

Who has given what military assistance to Ukraine, and why? As a first cut, we investigate when NATO countries have given military hardware and equipment, whether by way of gifting them or through some sort of financing arrangement. summarizes the relevant data collected on arms transfers by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) as well as a variety of government announcements, news articles (using LexisNexis), and think-tank reports. It distinguishes between certain classes of weapons and lists most NATO members.

Table 1. Western military assistance to Ukraine, February 2014–January 2022.

Some countries may still be absent given a lack of verifiable information. Eyewitness accounts, for example, purport the presence of Bulgarian weapons that may have found their way into Ukraine through private sales (Schwritz Citation2021). Further complicating any accounting of arms transfers to Ukraine is that the donors themselves had at times withheld information from each other. It was not, however, a free-for-all: having grown out of the bilateral Ukraine-US Commission, the Multinational Joint Commission (MJC) provided a mechanism that Canada, Denmark, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States used to coordinate security assistance to Ukraine. By early 2017, it coordinated about 80% of the security assistance that Ukraine received from abroad (Independent Defence Anti-Corruption Committee Citation2017, 26; Ministry of Defence of Ukraine Citation2020).

Several tentative observations pertaining to security, economic, and risk considerations can be made. One is that, of the 30 countries that made up NATO during this period, only 14 had apparently made arms transfers to Ukraine. With one exception – Germany – all countries that are either a Framework Nation or a Host Nation in NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) have given some form of military assistance to Ukraine. The eFP comprises battalion-sized battlegroups led by Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States and are stationed in Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Poland, respectively. First deployed in 2017, these battlegroups serve to reassure the Host Nations and to deter Russia from launching a major attack against them. Because these battlegroups train extensively, their presence has necessitated significant investments in local military infrastructure. Strategic considerations thus seem to have driven support for Ukraine: the countries that have major roles in these NATO efforts are the most likely to assist Ukraine militarily. Germany, along with France (not a Framework Nation in the Baltic region), were exceptions. As both participated in the Normandy Format, they have considered that giving military assistance to Ukraine would have prejudiced their involvement in those peace talks. They had also opposed granting a NATO Membership Action Plan to Ukraine in 2008. France limited its assistance to transport helicopters and several patrol boats for use by the Ukrainian interior ministry. For its part, Germany decided not to send any military aid, preferring instead to offer medical assistance exclusively. Germany affirmed this position in 2021 when it blocked Ukrainian purchases of lethal equipment made through the NATO Support and Procurement Agency (Olearchyk and Hall Citation2021). Other European NATO countries contributed some level of military assistance to Ukraine, but a slim majority of them sent nothing.

Another observation relates to economic considerations – or lack thereof. Much of the equipment given was second-hand. The United States drew exclusively from its own stocks to provide Javelin anti-tank weapons. Second-hand military equipment provided by countries that once were part of the Soviet bloc – Czechia, Poland, and the three Baltic countries – date from the Soviet era. Giving out this equipment has accelerated the replacement of Soviet weapons in these countries, a process that dates back to the early post-communist period (International Institute of Strategic Studies Citation2020).

Two important exceptions are Turkey and the United Kingdom. Turkish leaders have ambitions for their defense industry to achieve self-sufficiency and may be more willing to compete with Russia, as shown in their support for Azerbaijan against Russian treaty ally Armenia in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. Although Turkey’s dependence on foreign imports constrains such aspirations, the planned joint production of corvettes, frigates, and armed drones with Ukraine aligned with the Turkish defense industry’s aims for increasing exports, competitiveness, and domestic prestige (Bağcı and Kurç Citation2017). Geopolitical considerations have only somewhat shaped Turkey’s approach. Turkey might not want to see Russia dominate the Black Sea and has competed with Russia in the Caucasus and Libya (Çelikpala and Erşen Citation2018). However, it refrained from joining its NATO allies in imposing sanctions on Russia and has threatened to block NATO’s efforts to implement defense plans for the Baltic region unless its allies recognized Kurdish rebel groups as terrorist organizations (Emmott and Irish Citation2020; Stein Citation2022). Importantly, Turkey has given little, if any, military aid beyond such sales. Before 2022, Britain expanded its defense co-operation with Ukraine, signing a Memorandum of Understanding in December 2020 and a Memorandum of Implementation in June 2021. This bilateral co-operation involves projects that largely relate to Ukraine’s Naval Capabilities Enhancement Program and so fits with the United Kingdom’s intent, as per its 2017 shipbuilding and defense industrial strategic documents, to reinvigorate its shipyards and to rebuild its defense industrial capacity (Ministry of Defence Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The 2017 shipbuilding strategy noted that, with prosperity now being a “national security objective in its own right,” export success was essential (Ministry of Defence Citation2017b, 27). Yet British economic considerations are easy to exaggerate: the United Kingdom’s 2021 Integrated Review identified Russia as the “most acute threat” facing the Euro-Atlantic area given its aggressive posture and hostile activities against British interests (Her Majesty’s Government Citation2021, 18). Still, the involvement of Turkish and British defense industries in Ukrainian security highlights how not every NATO country with a major defense industrial base has supported Ukraine. Germany’s and Italy’s reluctance between 2014 and 2022 was absolute, whereas France offered only patrol craft for use by Ukraine’s State Border Guard Services.

A third observation is that none of the weapons shifted the balance of power between Ukraine and Russia. On the contrary, those countries that gave weapons to Ukraine were very circumspect in what they provided, possibly due to the risk considerations described above. Much of the hardware and equipment offered to Ukraine is important for various tactical situations, whether on land or at sea, but they did not confer any capability to launch military offensives or hold at risk Russian military assets at range. Russia apparently had judged that Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones have limited effectiveness in high-intensity combat operations with a powerful adversary (Stein Citation2021). In at least one instance, the provision of a certain piece of equipment was withdrawn. Canada made available to Ukraine use of the Radarsat-2 system in 2015, only to end its provision in 2017 (Pugliese Citation2016). As the war went on, more countries provided military aid to Ukraine, however small that aid may have been. Before 2016, only five countries (Canada, Czechia, Lithuania, the United Kingdom, and the United States) sent military aid to Ukraine. By 2021, at least seven more had transferred arms to Ukraine. Just before Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, all three Baltic countries secured US approval to export to Ukraine a portion of their US-made Javelin anti-tank missiles and Stinger surface-to-air missiles. Risk considerations have thus attenuated over time. Earlier in the war, most NATO members may have wanted the Minsk Accords to succeed and so were reluctant to give any military assistance that could jeopardize those attempted peace agreements. Even before 2022, some states overcame their reservations and became more willing to give military assistance to Ukraine.

Risk considerations have shaped US calculations. Of course, events in 2014 led Washington to expand its military aid – an indication that strategic considerations do matter for the United States. It gave more than $2.5 billion between 2014 and 2021 to Ukraine (US Department of State Citation2021). In official statements, the reasoning invoked by US decision-makers concerned escalation risks. The impact of US military assistance to Ukraine thus remained limited despite the dollar amounts. In his 25 February 2015 congressional testimony to the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Secretary of State John Kerry declared that “I think everybody understands that we are not going to be able to do enough under any circumstance, that, if Russia decides to match it and surpass it, they are going to be able to do it. Everybody knows that, including [Ukrainian] President [Petro] Poroshenko.” He later added that “I don’t think anybody in this committee is suggesting the United States ought to be sending the 101st Airborne at this moment.” Because the Second Minsk Accord had just been negotiated, these escalation risks were salient. Perhaps Kerry was too optimistic, however, when noting that “our preference is to deescalate this, get back to the norms, and restore a relationship with Russia that could be more public and more productive in many, many different respects” (House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs Citation2015a, 24, 41). In her testimony to the same committee a week later, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Victoria Nuland evaded questions on why the Obama administration had not yet decided on sending lethal aid to Ukraine. Eventually, she highlighted escalation risks, saying that “On the one hand it goes to the Ukrainian need and desire to defend against the incredibly lethal offensive things that Russia has put in place since January–February. On the other side it goes to whether this actually serves to harden or whether it escalates and is considered provocative and makes it worse.” She stressed the importance of giving the Second Minsk Accord a chance, despite recognizing that Russia was already not being faithful to it. Critics expressed disappointment with the White House (House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs Citation2015b, 7, 36). In March 2014, Republican Senator John McCain cautioned that “[w]e shouldn’t be imposing arms embargoes on victims of aggression” (Entous Citation2014). During Nuland’s congressional testimony, one Republican lawmaker noted the inconsistency of the Obama administration in arming Syrian rebels against Russian-backed forces but not Ukraine (House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs Citation2015b, 35). Still, the Obama administration had public opinion on its side: a weakening majority of US survey respondents opposed providing arms to Ukraine (Pew Research Center Citation2015, 1). Corruption was a relatively less salient, yet significant, factor. Nuland described corruption as a “country killer in Ukraine” and asserted the need for deep reforms (House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs Citation2015b, 32).

Washington nevertheless leveraged its military aid to compel Kyiv to make desired changes in its security sector. The 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) required that the Secretaries of State and Defense must certify that the Ukrainian government “has taken substantial actions to make defense institutional reforms, in such areas as civilian control of the military, co-operation and coordination with Verkhovna Rada efforts to exercise oversight of the Ministry of Defense and military forces, increased transparency and accountability in defense procurement, and improvement in transparency, accountability, and potential opportunities for privatization in the defense industrial sector, for purposes of decreasing corruption, increasing accountability, and sustaining improvements of combat capability” (114th Congress Citation2015, 2495), a stipulation reiterated in subsequent NDAAs. shows how Congress expanded its list of which forms of direct military assistance could be sent to Ukraine. Note that in the 2016 NDAA, which brought the USAI into existence, only $50 million (out of $300 million) “shall be available only for lethal assistance” (114th Congress Citation2015). USAI may be institutional in character, but the executive branch had been unwilling to provide the lethal assistance that could have strongly signaled commitment. Accordingly, congressional authorizations do not imply actual deliveries of military aid.

Table 2. Congressional authorization for military assistance to Ukraine per the USAI.

The United Kingdom shared these assessments. Like Washington, London was quick to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine but slow to offer significant military assistance to Ukraine. Part of the initial reluctance stemmed from perceived escalation risks. In an 8 March 2015 interview with broadcaster Andrew Marr, when asked about giving military assistance to Ukraine, Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond demurred, saying that “[w]e don’t think there can be a military resolution to this crisis. The disparity between the size of the Ukrainian armed forces and the Russian armed forces doesn’t make that a sensible way to go” (Andrew Marr Show Citation2015). Much of the equipment to Ukraine was gifted at London’s expense and was non-lethal, encompassing protective gear, decommissioned armored personnel vehicles, and other equipment intended to enhance tactical awareness (Mills Citation2015, 5; Gawęda Citation2016). Still, Hammond noted in a February 2015 parliamentary debate that “we cannot afford to see the Ukrainian army collapse” (Hansard Citation2015). Thus, the United Kingdom launched Operation ORBITAL in March 2015, which had overseen the provision of non-lethal military equipment as well as short-term training teams to improve Ukrainian military personnel’s basic infantry and medical skills. Between 2015 and 2020, these teams have purportedly trained about 20,000 Ukrainian soldiers (Ministry of Defence Citation2020).

The United States and the United Kingdom were exceptional, and so the preceding observations, provisional as they are, point to one conclusion: if arms transfers provide an option to substitute for an alliance, most NATO members were simply not availing themselves of it with respect to Ukraine before February 2022.

Military assistance to Ukraine amid Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion

NATO members’ military assistance to Ukraine expanded over the course of 2022, however. When a major Russian attack on Ukraine looked imminent in early 2022, the United States and the United Kingdom increased their provision of anti-armor weapons, with other previous providers of military assistance also stepping up lethal and non-lethal assistance as well. After Russia launched its full-scale invasion and Ukraine demonstrated that it could resist effectively, NATO countries sent more military assistance, typically of the sort that Ukraine had openly sought given Russian aerial and artillery advantages. Drawing from the Kiel Ukraine Weapons Project, which collects information on government-to-government humanitarian and military transfers made to Ukraine since 24 January 2022, () offers the summary data. The discussion that follows draws on these data to examine the correlates of post–24 January 2022 support for Ukraine and thus to understand better the drivers of NATO members’ decisions regarding Ukraine’s defense.

Table 3. Western military assistance to Ukraine, 2022.

Because more NATO members have begun providing military assistance, and the Kiel Institute has tracked this assistance in a way that is normalized across allies as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), we can test hypotheses using multivariate regression in a way that we could not do above, placing such assistance alongside data that cover strategic, economic, and risk considerations. Expressed formally, we test the below hypothesis using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression with a cross-sectional datasetFootnote2:

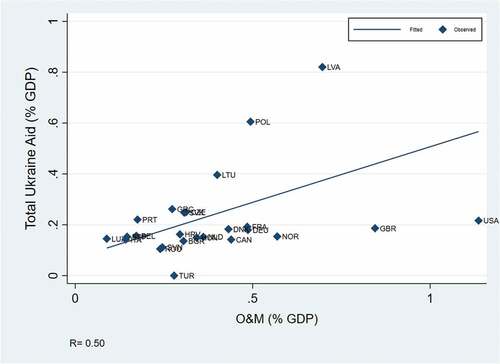

For strategic considerations, we examine the share of GDP allocated to operating and maintenance spending in 2019 (. We choose this measure over alternatives such as a more general one on military spending because it better captures preparedness and readiness to face military threats. Our main hypothesis is that the more a country committed itself to training, exercising, and deploying its military in the years leading up to Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, the more that country has contributed to Ukraine’s defense since that time. Preparation counts: generating forces after a crisis has emerged is difficult, and countries manage crises with the capabilities that they have developed before that crisis. We also include a measure BALTIC that is an indicator variable for Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, reasoning that those countries, due both to proximity with Russia and the difficulty of measuring historical legacies, might be more apprehensive towards Russia and more attuned to Ukraine’s security needs.

Regarding economic considerations, we include GDP/capita (GDPCAP) to capture the possibility that wealthier countries may have different preferences than less wealthy ones over whether to provide either indirect or direct aid. Though SIPRI data on arms exports could theoretically help capture potential indirect or spillover benefits that countries could gain from providing military aid to Ukraine, the most recent data are available for only nine NATO members in 2020, making it unproductive to incorporate them into a multivariate model.

Finally, for risk considerations, we include RUSSIANFUELDEP to track a country’s total fossil fuel dependency on Russia, defined as the “share of total energy supply for all fossil fuels” represented by Russian exports (International Energy Agency Citation2022). We hypothesize that the greater the dependency on Russia, the more reluctant a country would be to arm Ukraine lest Russia would retaliate by selectively withdrawing its energy exports. Straddling the line between strategic and risk considerations, we also incorporate measures that relate to how frequently a country votes with Russia in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). States whose votes more frequently align with Russia might withhold aid because they lack interest or perceive too much risk in supporting Ukraine against Russian aggression, or simply due to ideological affinity with Russa.

We present the results of this analysis in . The results in columns 1 and 2 are striking: previous O&M spending is significantly and positively correlated with both total (at the 10% level) and military (at the 5% level) aid to Ukraine following 24 February 2022. Unsurprisingly, the indicator variable for the three Baltic states and Poland is also positively correlated with both forms of aid provision, at the 1% level. Column 3 replicates the exercise using the pre-2022 qualitative, ordinal variable as the dependent variable, with similar results, significant at the 5% level for O&M spending, but insignificant for the BALTIC indicator. Columns 4–6 replicate the analysis using infrastructure spending rather than O&M as the independent variable: post-2014 developments (chiefly, NATO’s eFP) have encouraged those states that may have focused on O&M expenditures previously to invest heavily in infrastructure in support of allied military presence on their territory.

Table 4. Correlates of aid to Ukraine, post–24 January 2022.

The results for the post-2022 dependent variable are consistent with those from columns 1–3, but those for pre-2022 aid are not statistically significant for either O&M or the BALTIC indicator. Only UNGA alignment with Russia has a negative, statistically significant relationship with support for Ukraine: NATO countries that vote most consistently with Russia tend not to give military aid. Admittedly, this plausible finding must be treated with some caution given possible measurement error: Estonia, Turkey, and Greece are apparently the three most Russia-aligned countries within NATO, whereas Hungary is the third-least Russia-aligned. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that while non-neighboring countries with “expeditionary” approaches to the use of their militaries may have begun offering military aid to Ukraine prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, nearby countries with less capacity to do so only intensified support of this kind after that invasion had begun. To facilitate comparison of pre- and post-2022 aid, lists the scores on both metrics for each country.

Table 5. Pre–February 2022 qualitative aid score versus post–February 2022 aid/GDP.

visualizes the relationship between 2019 O&M spending and total aid for Ukraine in 2022. O&M spending is a strong predictor of total aid. The upside outliers are not surprising: Lithuania, Poland, and Latvia are likely more invested in a war at their doorstep and so offer more aid to Ukraine. Conversely, the United States and the United Kingdom, while they have offered major support to Ukraine in 2022, also have significant interests farther afield and thus have long spent considerably on O&M. Notably, Turkey appears in the Kiel dataset as being among the most anemic contributors of military aid to Ukraine. Although Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones have figured prominently in Ukraine’s defense against Russia, they and other Turkish defense articles are in Ukraine because they were sold to Ukraine, reflecting economic rather than strategic motivations (Malsin Citation2022).

This analysis also indicates that defense inputs – specifically, spending – are generally predictive of operational outputs (Becker Citation2017). Furthermore, it supports critiques of, for instance, German claims that national procurement systems would be unable to use effectively those funds provided by increases in defense spending (Kamp Citation2019), suggesting instead that such systems are even less likely to emerge in a crisis and that prior investment is critical. The countries that invested in training and readiness before Russia’s full-scale invasion were better positioned to support Ukraine after the outset of that operation than those that did not.

Because of the small number of observations and the cross-sectional nature of the data (covering only 2022), more sophisticated statistical analysis is unlikely to illuminate any further the relationship between the independent variables above and aid to Ukraine at present. The analysis is merely correlational – we cannot statistically ascertain causality. However, O&M spending may be causally prior to support for Ukraine given that O&M spending precedes Ukraine aid temporally – a finding that is aligned with the theoretical logic that countries more interested in exercising and undertaking military operations before Russia’s 2022 invasion generally offered more support to Ukraine after its launch. Nonetheless, because omitted variable bias might affect our analysis, we ran pairwise correlationsFootnote3 to determine that such bias is probably not driven by several other theoretically plausible variables that could affect Ukraine aid: Atlanticist foreign policy orientation (Becker and Malesky Citation2017), propensity to engage in Official Development Assistance (World Bank Citation2021), or the role of the arms industry in domestic economies (SIPRI Citation2019; Becker Citation2019). None of these variables correlates significantly with the dependent variable of interest or even other forms of aid (humanitarian and financial). We are confident that our statistical analysis offers a reasonable description of the factors that drive post–February 2022 support for Ukraine.

Conclusion

Russian leaders have long demanded that NATO countries curtail their military assistance to Ukraine, arguing that this military assistance constituted such a strong commitment to Kyiv as to give it a blank check. Upon launching its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Kremlin escalated such rhetoric by threatening to strike Western supply lines. Yet, on closer inspection, the record of military assistance to Ukraine suggests at best a partial and highly qualified commitment given that NATO members could have used arms transfers to signal some degree of support absent treaty-based security guarantees to Ukraine. Before 2022, less than half of NATO allies offered military assistance, and that which they provided has largely been in the form of second-hand equipment that could not plausibly allow Ukraine to tilt the balance against Russia, let alone undertake (counter-)offensive operations. NATO members’ provision of military assistance expanded after the full-scale invasion began. The quality also improved, especially because Ukraine proved highly capable and resolved in fighting Russian military aggression. Several NATO allies began to send heavy artillery, armored vehicles, and other systems.

Absent fine-grained decision-making data, any observations about states’ motivations for providing (or not) military assistance must be tentative. Still, strategic preparation in the form of prior investment seems to play a more prominent role than economic and risk considerations at this stage in the conflict. The countries that have offered the most military assistance to Ukraine have also been those most actively engaged in training, deployments, operations, and infrastructure development aimed at strengthening NATO’s eastern flank, whether because they are there or because they see Russia as a major threat. As of this writing, fossil fuel dependence has not materially dampened the provision of military aid. Countries with high dependency ratios, after all, include not only Germany and Italy, but also the Baltic countries. This phenomenon will be tested in the winter of 2022–23. Germany and Italy, for instance, will be particularly interesting test cases going forward, but scholars will have to disentangle the effects of fossil fuel dependence from those created by years when national defense capabilities saw limited investment. Currently available data point to the latter, but with time, additional data may help scholars identify the true drivers of support. Dysfunction in procurement systems may be an obstacle to spending and throughput prior to a crisis, but the current crisis has not seemed to resolve such dysfunction in the German case – a policy of investing now to be prepared for future crises would be better than simply hoping that such crises will not materialize.

Other considerations have mattered, but their salience has varied across time and countries. Even those states that have given weapons to Ukraine may have worried at one point about possible entrapment, corruption, and the possibility of diversion. Accordingly, multiple factors drive the extent and substance of military assistance to Ukraine. Yet important variation exists over time: more and more states have given more and more military assistance to Ukraine as the years pass, and particularly since Russia began its full-scale invasion. For example, Turkey now co-produces certain platforms with Ukraine, though its motives remain largely commercial, considering Turkish leaders’ interests in reconstituting their national defense industry and the lack of military aid to Ukraine beyond such sales. Notably, the United States began sending Javelins to Ukraine in 2018 and the United Kingdom has expanded its defense co-operation with Ukraine across the board: from naval capabilities to anti-air and anti-tank weaponry. These leading providers of military aid themselves have articulated concern over escalation risks. They have, after all, forsaken the direct use of military force to defend Ukraine during 2022. Concerns aired by the Kremlin about the commitment value of military assistance rendered to Ukraine from NATO countries are both exaggerated and disingenuous.

This article presents an initial analytical assessment of one dimension of an evolving war. Much remains to be done. Future research can use increasingly detailed data on military aid to Ukraine to determine if the observations made above still hold as the war continues. Crucially, scholars can investigate specific cases of countries that have – or have not – given military aid to Ukraine to produce more detailed assessments of their decision-making process. One major question involves apparent differences between material aid for Ukraine itself before and after Russia’s full-scale invasion: why does Ukraine-specific aid prior to February 2022 not appear to predict post-2022 military aid?

Paired comparisons between similar countries could also be a fruitful research strategy. Examining apparently deviant cases such as Turkey, Latvia, and the United States, which all show high residuals in , could help probe new explanations regarding differences in the military aid provided to Ukraine (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008). That fossil fuel dependency rates do not at this stage seem to drive decisions about providing military support for Ukraine is surprising, given the apparent consensus among analysts and practitioners that the war’s effects on global food and fossil fuel supplies represent a strategic vulnerability for Europe and North America, and a valuable tool for Russia (European Commission Citation2022; Welsh Citation2022). A “most similar” case study design comparing states with similar dependency ratios and different levels of aid provision could illuminate this apparent paradox (Gerring Citation2008).

As allied strategists and operational planners help Ukraine to secure its territorial integrity and national existence in the near term, a longer-term analysis of the incentives facing decision-makers in Western capitals holds promise in terms of both generating policy-relevant insights and understanding broader issues of theoretical importance to scholars, including alliance burden-sharing (McGerty et al. Citation2022), alignment (Gannon and Kent Citation2021), indirect support for partners in conflict (Gannon et al. Citation2021), and conflict dynamics between Russia and its neighbors (Åtland Citation2020; Hedgecock and Person Citation2022). This essay offers a framework for analyzing the Russo-Ukrainian war in dialogue with this scholarship while providing some initial empirical tests. Future research can extend this framework by further clarifying the drivers of wartime military assistance to Ukraine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew Bowen, Jordan Cohen, and Mauro Gilli as well as four anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback on earlier drafts of this essay. All errors are the authors’. A separate online appendix that records NATO members’ military assistance to Ukraine between 2014 and November 2022 is available at www.alexlanoszka.com. Alexander Lanoszka is assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo. Jordan Becker is Director of the Social Science Research Lab at West Point. He is an Associate Researcher at the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy in the Brussels School of Governance, and IHEDN and IRSEM in the French École de Guerre. This article reflects their analysis alone and does not reflect any official position of the US Government.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Sometimes military assistance refers to a gift of military training and equipment, whereas military aid can entail an approved sale or loan, usually done with some financing to ease the purchase for the recipient. Countries vary in the terms they use to describe arms sales. The United Kingdom, for example, uses the term “defence engagement.” For stylistic purposes, we use “military assistance” and “military aid” interchangeably. Our use of these terms does not cover instances where a state contributes to security-sector reform. Such contributions aim primarily at governance and institution-building across many issue-areas (Hanssen et al. Citation2016). Note that we largely lump together foreign military financing and foreign military sales to simplify the discussion.

2. We use ordered probit regressions to analyze the qualitatively coded pre–February 2022 aid (models 3 and 6) because of the ordinal nature of that variable.

3. See the online Supplementary Table 1.

References

- 114th Congress. 2015. “National Defense Authorization Act [NDAA] for Fiscal Year [FY] 2016”. Public Law 114-92.

- 114th Congress. 2016. “NDAA for FY 2017”. Public Law 114-328.

- 115th Congress. 2017. “NDAA for FY 2018”. Public Law 115-91.

- 115th Congress. 2018. “John S. McCain NDAA for FY 2019”. Public Law 115-232.

- 116th Congress. 2019. “NDAA for FY 2020”. Public Law 116-92.

- 116th Congress. 2020. “William M. Thornberry NDAA for FY 2021”. Public Law 116-283.

- 96th Congress. 1979. “Taiwan Relations Act”. Public Law 96-8.

- Antezza, A., A. Frank, P. Frank, L. Franz, I. Kharitonov, B. Kumar, E. Rebinskaya, and C. Trebesch. 2022. “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How?” Kiel Working Papers 2218 (August).

- Åtland, K. 2020. “Destined for Deadlock? Russia, Ukraine, and the Unfulfilled Minsk Agreements.” Post-Soviet Affairs 36 (2): 122–139. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2020.1720443.

- Bağcı, H., and C. Kurç. 2017. “Turkey’s Strategic Choice: Buy or Make Weapons?” Defence Studies 17 (1): 38–62. doi:10.1080/14702436.2016.1262742.

- Becker, J. 2017. “The Correlates of Transatlantic Burden Sharing: Revising the Agenda for Theoretical and Policy Analysis.” Defense & Security Analysis 33 (2): 131–157. doi:10.1080/14751798.2017.1311039.

- Becker, J. 2019. “Arms without Influence? Spatial Distribution of Defense Industrial Activity, Transatlantic Burden Sharing, and Strategy.” Working paper. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3343493.

- Becker, J., and P. Dunne. 2021. “Military Spending Composition and Economic Growth.” Defence and Peace Economics 1–13. doi:10.1080/10242694.2021.2003530.

- Becker, J., and E. Malesky. 2017. “The Continent or the ‘Grand Large’? Strategic Culture and Operational Burden-Sharing in NATO.” International Studies Quarterly 61 (1): 163–180. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw039.

- Benson, B.V. 2012. Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brauer, J., and J.P. Dunne. 2004. “Introduction.” In Arms Trade and Economic Development: Theory, Policy, and Cases in Arms Trade Offsets, edited by J. Brauer and J.P. Dunne, 1–19. London: Routledge.

- Bukkvoll, T. 2019. “Fighting on Behalf of the State—the Issue of Pro-Government Military Autonomy in the Donbas War.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35 (4): 293–307. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2019.1615810.

- Carpenter, T.G. 2021. “Why Ukraine Is a Dangerous and Unworthy Ally.” The National Interest, June 28. Accessed 19 July 2021. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/skeptics/why-ukraine-dangerous-and-unworthy-ally-188742

- Çelikpala, M., and E. Erşen. 2018. “Turkey’s Black Sea Predicament: Challenging or Accommodating Russia?” Perceptions 23 (2): 72–92.

- Cohen, M. 2016. “Ukraine’s Battle of Ilovaisk, August 2014: The Tyranny of Means.” Military Review 10: 1–11.

- Colborne, M. 2022. From the Fires of War: Ukraine’s Azov Movement and the Global Far Right. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Council on Foreign Relations. 2014. “Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk on Ukraine’s Challenges.” Council on Foreign Relations, September 24. Accessed 3 July 2021. https://www.cfr.org/event/ukrainian-prime-minister-arseniy-yatsenyuk-ukraines-challenges-0

- Digiuseppe, M., and P. Poast. 2018. “Arms versus Democratic Allies.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 981–1003. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000247.

- Emmott, R., and J. Irish. 2020. “Turkey Still Blocking Defence Plan for Poland, Baltics, NATO Envoys Say.” Reuters, June 17. Accessed 2 August 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-france-turkey-plans-idUSKBN23O1TN

- Entous, A. 2014. “U.S. Balks at Ukrainian Military-Aid Request.” Wall Street Journal, March 13. Accessed 31 December 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304914904579437523037894270

- European Commission. 2022. “REPowerEU.” May 18. Accessed 15 July 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3131

- Eurostat. 2022. “EU Energy Mix and Import Dependency.” March 4. Accessed 4 July 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_energy_mix_and_import_dependency

- Fasola, N., and A.J. Wood. 2021. “Reforming Ukraine’s Security Sector.” Survival 63 (2): 41–54. doi:10.1080/00396338.2021.1905990.

- Fearon, J.D. 1997. “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1): 68–90. doi:10.1177/0022002797041001004.

- Ford, M. 2020. “The Epistemology of Lethality: Bullets, Knowledge Trajectories, Kinetic Effects.” European Journal of International Security 5 (1): 77–93. doi:10.1017/eis.2019.12.

- Frühling, S., and G. Lasconjarias. 2016. “NATO, A2/AD and the Kaliningrad Challenge.” Survival 58 (2): 95–116. doi:10.1080/00396338.2016.1161906.

- Gannon, J.A., E. Gartzke, J.R. Lindsay, and P. Schram. 2021. “The Shadow of Deterrence: Why Capable Actors Engage in Conflict Short of War.” Working paper. Accessed 1 December 2022. https://peterschram.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/gray_zone_web.pdf

- Gannon, J.A., and D. Kent. 2021. “Keeping Your Friends Close, but Acquaintances Closer: Why Weakly Allied States Make Committed Coalition Partners.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65 (5): 889–918. doi:10.1177/0022002720978800.

- Gawęda, M. 2016. “‘Useless’ Saxon Vehicles Surprisingly Useful in Ukraine. Kiev Benefits from the ‘Cost-Effect’ Ratio.” Defence24, August 3. Accessed 17 July 2021. https://www.defence24.com/useless-saxon-vehicles-surprisingly-useful-in-ukraine-kiev-benefits-from-the-cost-effect-ratio

- Gerring, J. 2008. “Case Selection for Case‐Study Analysis: Qualitative and Quantitative Techniques.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by J.M. Box-Steffensmeier, H.E. Brady, and D. Collier, 645–684. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hansard. 2015. “Ukraine Volume 592: Debated on Tuesday 10 February 2015.” Accessed 15 July 2021. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2015-02-10/debates/15021030000001/Ukraine

- Hanssen, M. 2016. “International Support to Security Sector Reform in Ukraine: A Mapping of SSR Projects.” Folke Bernadotte Academy. Accessed 19 December 2022. https://fba.se/en/about-fba/publications/international-support-to-security-sector-reform-in-ukraine/

- Hedgecock, K., and R. Person. 2022. “Bargaining with Blood: Russia’s War in Ukraine.” Brussels School of Governance, Centre for Strategy, Diplomacy and Security. Accessed 15 July 2022. https://brussels-school.be/publications/policy-briefs/bargaining-blood-russia%E2%80%99s-war-ukraine

- Horowitz, M.C. 2010. The Diffusion of Military Power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs. 2015a. “Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs House of Representatives.” 114th Congress, February 25.

- House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs. 2015b. “Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs House of Representatives.” 114th Congress, March 4

- Independent Defence Anti-Corruption Committee. 2017. Making the System Work: Enhancing Security Assistance for Ukraine. Kyiv and London: Transparency International Defence and Security and Transparency International Ukraine.

- International Energy Agency. 2022. “Reliance on Russian Fossil Fuels in OECD and EU Countries—Data Product.” Accessed 19 December 2022. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/reliance-on-russian-fossil-fuels-in-oecd-and-eu-countries

- International Institute of Strategic Studies. 2020. The Military Balance 2020. London: Routledge.

- Ivanovska, M. 2017. “Mistakes and Mass Desertion: Report Identifies Causes of Ukraine’s Largest Military Defeat.” Hromadske, August 18. Accessed 2 July 2021. https://en.hromadske.ua/posts/mistakes-and-mass-desertion-report-identifies-causes-of-ukraines-largest-military-defeat

- Jacqmin, D. 2020. “Ukraine.” In The Economics of the Global Defence Industry, edited by K. Hartley and J. Belin, 265–281. London: Routledge.

- Kamp, K-H. 2019. “Myths Surrounding the Two Percent Debate: On NATO Defence Spending.” Bundesakademie für Sicherheitspolitik, September. Accessed 15 July 2022. https://www.baks.bund.de/en/working-papers/2019/myths-surrounding-the-two-percent-debate-on-nato-defence-spending

- Kiel Institute for the World Economy. 2022. “Ukraine Support Tracker.” Accessed 15 July 2022. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/

- Kim, T. 2011. “Why Alliances Entangle but Seldom Entrap States.” Security Studies 20 (3): 350–377. doi:10.1080/09636412.2011.599201.

- Lieber, K. 2008. War and the Engineers: The Primacy of Politics over Technology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Lombardi, B. 2014. “Crimea—Naval and Strategic Implications of Russia’s Annexation.” Defence Research and Development Canada, September 22. Accessed July 5, 2021. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1017642.pdf

- Majesty’s Government, Her. 2021. “Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy.” March 16. Accessed 19 December 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy

- Malsin, J. 2022. “Turkish Defense Industry Grows Cautious over Selling Weapons to Ukraine.” Wall Street Journal, June 21. Accessed 15 July 2022. https://www.wsj.com/articles/turkish-defense-industry-grows-cautious-over-selling-weapons-to-ukraine-11655803802

- Marr Show, Andrew. 2015. “Philip Hammond, Foreign Secretary.” British Broadcasting Corporation, March 8. Accessed 10 July 2021. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/08_03_15_philip_hammond.pdf

- McGerty, F., D. Kunertova, M. Sargeant, and A. Webster. 2022. “NATO Burden-Sharing: Past, Present, Future.” Defence Studies 22 (3): 533–540. doi:10.1080/14702436.2022.2082953.

- Mills, C. 2015. “UK Military Assistance to Ukraine.” House of Commons Briefing Paper Number SN07135, May 20.

- Ministry of Defence. 2017a. Industry for Defence and a Prosperous Britain: Refreshing Defence Industrial Policy. London: Her Majesty‘s Government.

- Ministry of Defence. 2017b. National Shipbuilding Strategy: The Future of Naval Shipbuilding in the UK. London: Her Majesty‘s Government.

- Ministry of Defence. 2020. “Operation ORBITAL Explained: Training Ukrainian Armed Forces.” Medium, December 21. Accessed 15 July 2021. https://medium.com/voices-of-the-armed-forces/operation-orbital-explained-training-ukrainian-armed-forces-59405d32d604

- Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. 2020. “Multinational Allied Support within the Reform of Ukraine’s Armed Forces: Implementation of NATO Standards in the Ukrainian Army.” June 6. Accessed 21 July 2021. https://www.mil.gov.ua/en/news/2020/06/19/multinational-allied-support-within-the-reform-of-ukraines-armed-forces-implementation-of-nato-standards-in-the-ukrainian-army/

- Moore, T.C. 2014. “The Role of Nuclear Weapons during the Crisis in Ukraine, A Working Paper.” Richard Lugar Center, July 4. Accessed 3 July 2021. https://www.thelugarcenter.org/newsroom-tlcexperts-8.html

- Morrow, J.D. 2000. “Alliances: Why Write Them Down?” Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 63–83. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.63.

- NATO. 1949 [2019]. “The North Atlantic Treaty.” Accessed 20 July 2021. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm

- NATO. 1995. “Study on NATO Enlargement.” Accessed 15 July 2022. http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_24733.htm

- NDAA for FY 2022. Public Law 117-81.

- Olearchyk, R., and B. Hall. 2021. “Ukraine Blames Germany for ‘Blocking’ NATO Weapons Supply.” Financial Times. December 12. Accessed December 30, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/1336c9be-f1c9-4545-9f85-3b07fcb746d6

- Oliker, O., L.E. Davis, K. Crane, A. Radin, C. Ward Gventer, S. Sondergaard, J.T. Quinlivan, et al. 2016. Security Sector Reform in Ukraine. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

- Pamp, O., and P.W. Thurner. 2017. “Trading Arms and the Demand for Military Expenditures: Empirical Explorations Using New SIPRI-Data.” Defence and Peace Economics 28 (4): 457–472. doi:10.1080/10242694.2016.1277452.

- Polyakov, L. 2018. “Defense Institution Building in Ukraine at Peace and at War.” Connections 17 (13): 92–108. doi:10.11610/Connections.17.3.07.

- Pugliese, D. 2016. “Red Tape Forces Canada to Stop Providing Ukraine’s Military with Satellite Imagery of Russian Forces.” The National Post, August 1. Accessed 23 July 2021. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/red-tape-forces-canada-to-stop-providing-ukraines-military-with-satellite-imagery-of-russian-forces