Indigenous peoples forged their lives in present-day north-central Venezuela across millennia until confronted by Spanish conquerors in the early sixteenth century. Some historical trajectories were then abruptly disrupted whilst others were profoundly transformed. Using the direct historical approach, various scholars have assumed that the material signatures of the late pre-colonial archaeological cultures relate directly to the indigenous groups recorded for this region in the early colonial documents (Acosta Saignes Citation1954; Antczak Citation1999; Antczak and Antczak Citation2006; Antczak, Haviser et al. Citation2018; Biord Castillo Citation1992; Citation2001; Citation2005; Citation2006; Citation2016; Marcano Citation1971 [1889–1891]; Rivas Citation1994; Citation2002; Sanoja and Vargas Citation1974; Citation1999; Citation2002). However, the validity of societal reconstructions across the colonial divide based on the direct historical approach falls into doubt when adequate archaeological evidence is unavailable to support, contradict or complement such reconstructions (A. T. Antczak and Antczak Citation2015; Antczak, Urbani et al. Citation2017; Antczak, Antczak et al. Citation2018).

Archaeological evidence of early interactions between indigenous peoples and Spanish conquerors in north-central Venezuela is fragmentary. The presence of European ceramics apparently associated stratigraphically with pottery related to late pre-colonial styles suggests some such interactions in certain sites (Cruxent and Rouse Citation1958). There are also some surface findings of indigenous and non-indigenous materials in sites proximate to localities reported in early colonial documents. Some of these localities were allotments of village tribute and labor (encomiendas), and others were settlements (pueblos de doctrina) where Spanish-European colonists subjected indigenous peoples to religious indoctrination (Biord Castillo Citation2006; Rivas Citation2002; Bencomo Citation1993; Ganteaume Citation2012; Sanoja and Vargas Citation2002). Moreover, only in very few areas of north-central Venezuela have the documentary and the late pre-colonial and early colonial archaeological records been combined. This has been done, for example, within the area of influence of the modern city of Caracas (Sanoja and Vargas Citation2002) and in some rural peripheral areas in neighboring Vargas State (Rivas Citation2000; Citation2001; Citation2002). Yet the potential for further diachronic interdisciplinary research exists in even these sites.

The aim of this paper is to shed light on the indigenous lives in early sixteenth-century north-central Venezuela from an interdisciplinary perspective. The results will provide a backdrop for further historical archaeological research into fully colonial social realities, as well as invigorate investigation into ethnogenetic transformations that might have resulted from the European irruption. We use, as the main documentary source about early colonial times in the region, the Relación de Nuestra Señora de Caraballeda y Santiago de León written by Juan de Pimentel in 1578 (1964).Footnote1 Pimentel was the governor and captain general of the Province of Venezuela between 1576 and 1583 and the first to take up residence in recently conquered Caracas. He wrote the Relación as a series of responses to a questionnaire sent by King Philip II of Spain.Footnote2 Its aim was to ascertain the potentialities and limitations of this part of the Crown’s overseas territories (Arellano Moreno Citation1964). To meet this requirement, Pimentel not only set in motion a series of inquisitive administrative measures but personally visited some of the indigenous settlements in the province. We also draw on data both contemporaneous with and antecedent to Pimentel’s document, e.g. from Barbudo Citation1964 [1570–1575], Agreda Citation1964 [1581], and Aguado Citation1987 [1581]. Finally, we make use of later work, e.g. a chronicle by Oviedo y Baños (Citation1982 [1723]) called Historia de la Conquista y Población de la Provincia de Venezuela.

The wealth and diversity of ethnohistorical data contained in Pimentel’s document has previously been the object of studies published in Spanish (Oramas Citation1940; Dupouy Citation1945; Nectario María Citation1979; Rivas Citation1994; Biord Castillo Citation2001). Biord Castillo (Citation2001; Citation2003), following the proposal of Bermejo de Capdevila (Citation1967), compared Pimentel’s ethnohistoric content (1964 [1578]) to Oviedo y Baños’s (Citation1982) writings and concluded that the latter had to have utilized a manuscript originally prepared by a soldier and poet known as Fernán Ulloa. Ulloa’s manuscript was requested by the town council of Caracas in 1593. Unknown today, it could have contained detailed information about the indigenous population of this region, plausibly collected by Ulloa from his own observations and compiled with the support of the still-living Spanish conquerors of the Province of Caracas. We also use Biord Castillo’s (Citation2007b) distinction between ethnohistory and history, according to which ethnohistory is a methodology governing how ethnohistorical data are extracted in specific ways from historical documentary sources. Further, instead of referring to the ethnohistory of a region, we refer to the history or ethnic history of its inhabitants.Footnote3 Rivas (Citation1994; Citation2002) also summarized information provided by Pimentel, incorporating data obtained from other written sources dating from the sixteenth century through the Republican period. He confirmed the historical continuity of some communities mentioned in the Relación until well into the twentieth century when biological and cultural miscegenation virtually erased their sense of indigenous identity. Antczak (Citation1999) also thoroughly researched the above-mentioned documentary sources while searching for early historical correspondence to the late pre-colonial archaeological evidence recovered in this region. He realized that with the passing of the colonial centuries, some of the ethnographic traits of the indigenous peoples were lost or transformed, making it increasingly difficult to assess the continuation of the pre-colonial cultural heritage.

All the above-mentioned scholars arrived at the conclusion that what distinguishes the Relación from other sources of its time is that it likely constitutes a kind of ‘real’ picture of the traditional indigenous way of life when the conquerors invaded the Province of Caracas. Therefore, we critically analyze this source in the context of its documentary counterparts as well as current linguistics and archaeology in order to evaluate its validity.Footnote4

The Province of the Caracas and its conquest

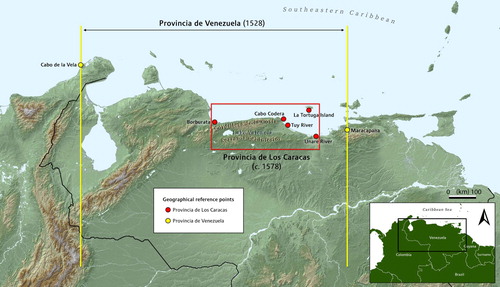

The Province of the Caracas covered the coastal range of north-central Venezuela during the early sixteenth century. It stretched between Cabo Codera (current Miranda State) and the Unare River in the east to the port village of Borburata (current Carabobo State) in the west (Barbudo Citation1964). To the north, it embraced the islands of Las Aves, Los Roques and La Orchila as well as La Tortuga Island. To the south, it included the Cordillera de la Costa mountain range as well as the valleys of Lake Valencia and the Caracas and Tuy Rivers, in addition to the central section of the Sierra del Interior (Pimentel Citation1964) ( and ).

Figure 1. The coast of present-day Venezuela depicted on the map of Juan de La Cosa dated to 1500 (Museo Naval de Madrid, MNM 00257).

Figure 2. Spatial demarcation of the Provincia de Venezuela in 1528 and of the Provincia de los Caracas in ca. 1578 (drawn by Konrad T. Antczak and Oliver Antczak).

The borders of the province were not well defined in any legal or administrative terms.Footnote5 Instead they delimited the cultural and linguistic unity of its indigenous inhabitants (Biord Castillo Citation2001; Citation2005). This spatiality also reflected the continued opposition of the local peoples to the Spanish colonial penetration which after Columbus’s third voyage in 1498 had begun in the northeastern (the island of Cubagua) and northwestern (the cities of Coro, El Tocuyo, and Barquisimeto) regions of today’s Venezuela (Antczak et al., Citationforthcoming). This territorial unit, based on the human geography of the time, was subsumed into a larger administrative unit, the Province of Venezuela.Footnote6 The Province of Caracas was largely inhabited by the Caraca Indians (Barbudo Citation1964; Pimentel Citation1964; Agreda Citation1964; Oviedo y Baños Citation1982).Footnote7 However, it also comprised other indigenous groups who resisted Spanish colonization. The term Caraca tends to disappear as an ethnic denominator in the late sixteenth century (Biord Castillo Citation2005). In some seventeenth-century documents, nevertheless, this name seems to identify a specific indigenous group settled around the town of Naiguatá in current Vargas State (Rivas Citation1994). In this paper, we refer to all north-central Venezuela indigenous peoples following the conceptualization of ‘aborigines’ in this region (Biord Castillo Citation2001; Citation2005; Citation2016).

The northeastern coast of today’s Venezuela had been explored by the Spanish after Columbus’s voyage in 1498 (Columbus Citation1988 [1498]; Perera Citation2000, 184–85). The first descriptions of the north-central area were produced a year later during the explorations of Alonso de Ojeda, Amerigo Vespucci and Pedro Alonso ‘Niño.’ Based on these surveys, Juan de la Cosa produced the first map of the coast of Tierra Firme which included the littoral section of the north-central region in 1500 (). This coastline extends approximately between Costa Pareja and Puerto Flechado and includes the villages of Cauchieto, Turma (possibly Tarma), and the Curiana of Pedro Alonso ‘Niño’ in current Vargas State (Rivas Citation1994).Footnote8 This region was inhabited by an allegedly numerous indigenous population but was uninhabited by Spanish colonists during the first decades of the sixteenth century.

The Europeans focused on the pearl fishery on Cubagua Island and on the capture of indigenous slaves, which was organized by armadas (formally authorized armed parties) from Cubagua, Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico (Arellano Moreno Citation1950; Otte Citation1977; Vila Citation1991). Other colonial mechanisms included rescate or enforced bartering aimed at obtaining food and gold from the indigenous people, as well as entradas or incursions into and conquest of new territories fueled by the fabled Province of the Meta and, later, the myth of El Dorado (Morón Citation1977; Perera Citation2000). During some rescates, the Spanish in Cubagua received information about the indigenous peoples in the north-central region, about the existence of Lake Valencia or Laguna de Tacarigua, and about local goods of commercial interest such as gold and textiles (Rivas Citation1994). All these colonial procedures had a destructive impact on the indigenous peoples’ traditional ways of life, mobility and exchange.

In 1555, Francisco Fajardo, a mestizo Guaiquerí–Spaniard, assisted by other GuaiqueríFootnote9 from Margarita Island who were led by his mother cacica (chief) Isabel, attempted to colonize the coast of the Province of Caracas and finally penetrated the Caracas Valley in 1560 (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982). Fajardo’s mother had kinship ties with several indigenous leaders settled on the central coast of current Vargas State as well as on its western border with current Aragua State (Puerto Maya) and gave her son proficiency in the Guaiquerí language (Biord Castillo Citation2005; Rivas Citation1994, 248–49; Citation2002, 110–12) (see below the section Some linguistic considerations).Footnote10 These kinship and language skills favored Fajardo’s first efforts, which nevertheless failed to consolidate the colonial enclaves he founded given the reluctance of some local indigenous leaders. Friction occurred in the Valle del Panecillo, the first coastal site in Vargas State where Fajardo arrived during his earliest colonization attempts (Altez Citation2002, 25–28; Rivas Citation2002, 132).Footnote11 The two enclaves he founded in 1560, i.e. the settlement of El Collado de Caraballeda on the coast and the Hato de San Francisco in the Valley of Caracas, also disappeared quickly. Indigenous peoples living in neighboring areas attacked Fajardo’s settlements and remained hostile to outside encroachment (Cruxent Citation1971; Ganteaume Citation2006; Nectario María Citation1979).

In 1567, the conqueror Diego de Losada entered the Valley of Caracas from the west and founded the city of Santiago de León de Caracas (Nectario María Citation1979, 111–29). The confederated indigenous peoples of the region under the chief Guaicaipuro commenced their last and unsuccessful offensive against the conquerors at the beginning of 1568.Footnote12 By 1578, the date of Pimentel’s Relación, the region was largely conquered. The process of assigning the north-central natives to the Spanish (repartimiento), converting them to Christianity, settling them in encomiendas or mandated reserves (assisted by Franciscan padres doctrineros) and, later, in missions (reducción), had begun across the entire province (Biord Castillo Citation2001; Rivas Citation1994). These measures provided the Spanish colonists with an initial labor force, knowledge of local natural resources, and communication routes which were soon utilized in the establishment of haciendas, country estates and some short-lived mining production centers.Footnote13 The Capuchins went into action on the eastern border of the province in the region of Barlovento,Footnote14 near the area of influence of the Province of Nueva Andalucía. Their enterprises were ephemeral given the reluctance of the Tomuza, the natives of this region, who resisted colonial control.Footnote15 The initiatives of Franciscan missionaries acting further east beyond the Unare River were more successful (Ruiz Blanco Citation1965 [1690]; Tauste Citation1888 [1680]).

Demography

Pimentel reported in 1578 that of 7,000 to 8,000 indigenes in the province, approximately 4,000 lived close to the towns of Caracas (inland) and Caraballeda (on the coast). Oviedo y Baños (Citation1982, 2:397) reported that in 1568, the confederated forces under the chief Guaicaipuro reached as many as 14,000 indigenous warriors. The real number must have been much smaller inasmuch as only about 10,000 inhabitants in all the province were reported for that time by López de Velazco (Citation1964 [1574]). Oviedo y Baños probably exaggerated the number of indigenous warriors to magnify the victory of the considerably less numerous Spaniards. Overestimation of indigenous forces, common in the documentation of that time, formed part of a strategy to garner more merit and thus better remuneration from the Crown in the form of land, positions in public administration, and number of allocated indigenous peoples under the rule of encomiendas.

As shown in and , the indigenous population of the province was reduced by half to three-quarters over an average of roughly 30 years. This is consistent with other estimates of the time (Rivas Citation1994, 183). Pimentel, supposed defender of the indigenous peoples (Nectario María Citation1979, 226), was nonetheless reluctant to recognize the aggressions of the colonizers. He attributed the marked drop in population to the effects of epidemic diseases such as smallpox (variola major), measles (rubeola), diarrhoea, catarrh and flu, in addition to warfare versus the Spaniards and to pre-conquest internal clashes. He emphasized that, after the city of Caracas was established, smallpox and measles eliminated fully one-third of the local indigenous population (Pimentel Citation1964). The smallpox epidemics reported in 1580–1581 and 1587–1590 in vast areas of northern South America together wiped out 90% of the indigenous population (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982; Morey Citation1979, 82; Hern Citation1994).

Table 1. Estimates for the indigenous population of the Province of Caracas 1567–1589.

Table 2. Estimates for the indigenous population of the Province of Caracas 1571–1607 (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 125).

Some linguistic considerations

Cariban languages were spoken along the northeastern coasts of South America between the Península de Paria in the east and the central Venezuelan coast in the west in an almost continuous territory ()Footnote16 in the mid-sixteenth century. Durbin (Citation1985) named the littoral peoples Coastal CaribsFootnote17 and classified them into a northern branch of Cariban languages that had purportedly migrated from their homeland in the Guiana land mass.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of the regional segments or ‘blocks’ of the ‘natives of north-central Venezuela,’ considered as a macro-ethnic grouping or as a subgroup of the northern Cariban speakers. The abbreviated form NNCV used in this figure refers to the north-central indigenous peoples according to the explanation provided in the main text (drawn by Konrad T. Antczak and Oliver Antczak).

The borders of the region occupied by the northern coastal Cariban speakers were, to the east, the Orinoco River Delta, occupied by the ancestors of the present-day Warao Indians whose non-Cariban language remains to be classified. To the west, the valley of the river Yaracuy (but not the mountainous lands of this region) was occupied by the Arawakan-speaking Caquetío (Arvelo and Oliver Citation1999; Rivas Citation1989, 1:xvii). To the south, the area was settled by the Guamo or Guamontey, another group of uncertain linguistic affiliation, some members of which were moved during the colonial period to encomiendas in the mountains of Yaracuy State (Rivas Citation1989, 1:xvii; Citation1997).Footnote18 Distribution of Cariban languages in present-day Venezuela and Colombia suggests a movement of Cariban speakers from the eastern and central Venezuelan coast through the plains into the Lake Maracaibo area, then north into the Sierra de Perijá, south through the foothills of these mountains, and to the Magdalena River (Durbin Citation1977, 30; 1985, 346, 349). These linguistic reconstructions are significant for creating and evaluating interdisciplinary models of pre-colonial settlement in the region. Archaeology, thus far, seems to confirm them (Antczak, Urbani et al. Citation2017; Arvelo and Wagner Citation1984; Rivas Citation1994; Citation2002; Sanoja Citation1969; Tarble Citation1985; Zucchi Citation1985).

However, it is still a matter of controversy whether all the natives of north-central Venezuela spoke a Coastal Cariban language (Loukotka Citation1968; Acosta Saignes Citation1946) or a Coastal Cariban dialect (Durbin Citation1985; Migliazza Citation1985; Biord Castillo Citation1995). This issue is crucial for our understanding of the role of the indigenous groups in the initial processes of European colonization. Marc de Civrieux (Citation1980, 40), drawing from the ethnohistoric sources, observed that the central (Cumanagoto) and eastern (Chaima) coastal Cariban speakers called themselves Choto (people, human beings) and spoke dialects of the same language (named Chotomaimú), permitting them to communicate with each other (Butt Colson and Heinen Citation1983–1984, 8; Butt Colson Citation1983–1984). Their western neighbors, such as the Caraca, Teque, and Meregoto (north-central indigenous peoples) would also have been considered as Choto and would also have spoken a dialect of Chotomaimú. If, as de Civrieux suggests, the suffix -goto in the Cariban languages means ‘the inhabitant of, or dweller of’ (thus Cumanagoto can be read as the inhabitant of Cumaná), then the term Meregoto (or Esmeregoto) seems to fit well into this structure (de Civrieux Citation1980, 37).Footnote19 This root is also present in the composition of other ethnonyms, anthroponyms and toponyms in the area (Rivas Citation2002, 111). Moreover, the name of the Toromayna or Toromayma indigenous group from the Valley of Caracas containing a final element -aima or -ima is clearly of Cariban origin (e.g., Adelaar and Muysken Citation2004, 114–15). The Toromayma peoples mentioned by Pimentel (Citation1964) were proceeding from an ancestral land they called Toromayma and were newcomers to the north-central Venezuela region. Toromayma is reminiscent of another ethnonym of the area, indicated in seventeenth-century documentation, where Tarama or Tarma was the name given to the Caraca who inhabited the mountainous area west of current Vargas State. This name still survives as a place name. It identifies a location of encomienda settlement and, later, resguardo in which indigenous peoples were concentrated from the beginning of the seventeenth century (Rivas Citation1994). If Tarama is indeed related to Toromaima, the Relación of Pimentel may suggest a regional shift from the west to the Valley of Caracas or on to the eastern coast of Vargas State (the city of Caraballeda) where Pimentel lived (Rivas Citation1994).

Data supporting the conclusion that inhabitants of the north-central region were Cariban speakers are drawn from two other sources: ethnohistoric information affirming mutual intelligibility with other contemporary colonial period idioms, and modern lexical comparisons with present-day Cariban languages. Two missionaries constitute the source of the ethnohistoric data. The first was Fray Francisco de Tauste (Citation1888), a Franciscan, who attended missions among the Chaima and learned their language. Tauste found that he could make himself understood, albeit with some difficulty, with the Caraca from the city of Valencia (west of Caracas). The second was the Jesuit missionary Felipe Salvador Gilij (Citation1965 [1782]), who, in 1782, commented that he had had a similar experience. Gilij lived at the La Encamarada mission located on the southern bank of the Middle Orinoco River between 1749 and 1767 and learned the Tamanaco language spoken there (Biord Castillo Citation1985, 84; Pache et al. Citation2017). This, as noted by Durbin (Citation1985) and Mattéi-Müller and Henley (Citation1990), was closely linked to coastal-northern Cariban languages. Gilij had to leave the country after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767. Before embarking for Italy, however, he spent a few months in La Guaira on the central Venezuelan coast. He noted there that the Caraca ‘language’ spoken by a native boy from La Guaira was closely related to the Tamanaco language (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 162). This observation seems to confirm the existence of a relatively close genealogical connection between the Caraca language and Tamanaco.

More evidence for the classification of Caraca as a Cariban language comes from the lexical comparisons performed by Juan Ernesto Montenegro (Citation1983), Rivas (Citation1994), and Biord Castillo (Citation2001; Citation2005). Based on Pimentel’s Relación, Biord Castillo and Rivas compiled a list of words possibly affiliated with the Caraca language and compared them with their counterparts in extinct Chaima, Cumanagoto and Tamanaco, as well as with some living Cariban languages such as Mapoyo/Wánai, Yabarana, E’ñepá, Kari’ña, Pemón and Yukpa. They found regular sound correspondences between the supposed Caraca-affiliated terms and those from different Cariban languages. This supports the inclusion of the Caraca language in the Cariban language family and reinforces the previous classifications (Durbin Citation1985; Loukotka Citation1968; Migliazza Citation1985; Oliver Citation1989; see also Montenegro Citation1983). Some linguistic data related to Caraca ethnonyms and regional toponymy may need further elaboration.Footnote20 Nonetheless, for the purposes of our discussion, we group the Caraca language alongside Chaima and Cumanagoto either as members of the Coastal (following Durbin Citation1985 and Villalón Citation1987) or the Northern Carib (Mattéi-Müller and Henley Citation1990) ensemble.

Pimentel’s Relación (Citation1964, 113) also enumerated the Guaiquerí among the indigenous groups that inhabited the Province of Caracas. This points to cultural or linguistic affinity or both between the Guaiquerí of Margarita Island and the people from the coast of north-central Venezuela. During the sixteenth century, the chiefs Charaima and Naiguatá on the central coast (and perhaps their villagers) can be considered direct relatives of the Guaiquerí, or at least of the Hispano-Guaiquerí leader Francisco Fajardo (Antczak Citation1999; Ayala Lafée-Wilbert et al. Citation2017, 347–51; Rivas Citation1994; Citation2002, 132). The question as to whether Guaiquerí was related to the Caraca language cannot be answered without analyses of additional ethnolinguistic data (Acosta Saignes Citation1954, 222–25). Studies carried out by Montenegro (Citation1983) and Ayala Lafée (Citation1994–1996; Ayala Lafée-Wilbert et al. Citation2017, 347–51) established several lexical parallels (possible cognates) between Guaiquerí and other languages of the coastal Caribs such as extinct Chaima and Cumanagoto as well as surviving Caraca.

Stating that ‘the language of all this province and nation […] is only one and in general caraca’ Pimentel (Citation1964, 119) provided further confirmation of the unity and intelligibility of the languages or dialects spoken by the indigenous peoples of the Province of Caracas. He mentioned a certain linguistic variance within the province by saying that ‘certain [Caraca] nations differ from each other in certain things, as Castilla and Montañas, Galicia and Portugal, and lastly they can understand each other’ (Pimentel Citation1964, 119). This observation is similar to Father Tauste’s century-older comment cited above (1888) about his experiences with the natives from the city of Valencia (see also Vásquez de Espinoza Citation1948 [1628]; Henley Citation1985). Based on this context, Biord Castillo (Citation1995, 129, 132; Citation2005) and Rivas (Citation1994) suggested that the indigenous peoples of the province would have pertained to one ethnic group divided into sub-groups speaking different dialects of the same language. In addition to geographical separation, contact with non-Cariban speakers may have tended to differentiate the Cariban dialects spoken in the area. For example, the non-Cariban languages in question may have been Arawakan languages, spoken by the late pre-colonial makers of Ocumaroid pottery (Antczak Citation1999; Antczak, Urbani et al. Citation2017; Rivas Citation1994). The language of these communities could have constituted a substrate providing distinctive elements to the Cariban of the northern central coastal area and could have resulted in a local dialect. At the least, those elements may have figured in the everyday lexicon as well as in geographical and people’s names (Rivas Citation1994; Citation2001).Footnote21

Who were the indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela?

The linguistic topics discussed above may be summed up by Gilij’s (Citation1965, 204) comment closely relating the Tamanaco of the Middle Orinoco to the Caraca of the central coast. He also noted small differences in the ‘same language’ spoken on the coast from Paria to Caracas. Such differences do not seem to have prevented mutual understanding amongst the indigenous peoples (Henley Citation1985, 154). Therefore, we may further ask: who were the indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela in sociocultural terms? To succinctly reply, we follow Biord Castillo (Citation1995), who compared two documentary sources: a primary (Pimentel Citation1964) and a secondary (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982) to weigh the content of the latter.Footnote22 Following the model of ethnohistorically and ethnographically known Cariban societies as proposed by Morales Méndez and Arvelo-Jiménez (Citation1981), the social formation of the Northern Caribs would have featured several subgroups speaking, in turn, dialectal variants of the same language (Chotomaimú or ‘language of the people,’ following de Civrieux Citation1980, 38). These subgroups would be the Cumanagotos, the Chaimas, the Guaiqueríes, and the indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela. Each of these four subgroups would have had regional components; it’s possible to speak in some detail of two of the subgroups. The Cumanagotos likely featured four or five as proposed by de Civrieux (Citation1980). The north-central indigenous peoples presented seven (Biord Castillo Citation2005): (1) Meregotos in the Valleys of Aragua; (2) Tarmas on the Caribbean coast; (3) Teques in the central mountain range; (4) Mariches in the eastern cordillera; (5) Guarenas in the central inland valleys; (6) Tomuzas in the Barlovento coastal area; and (7) Quiriquires in the depression of the plains (Depresión llanera). These regional components would have been characterized by closely interrelated villages. Rivas (Citation1994) includes the Caraca in this list although restricted to the surroundings of the coastal town of Naiguatá (Vargas state). Other indigenous peoples, including the Arbacos from the central mountains and the so-called ‘crazy Indians’ from an undetermined location, might have been non-Cariban communities, perhaps originally Arawakan speakers progressively displaced and finally assimilated by north-central indigenous peoples.Footnote23

Settlement pattern

Pimentel (Citation1964) observed that the villages in the north-central region were dispersed among the hills and ravines of the valleys and highlands of the interior and scattered on the slopes of the Cordillera de la Costa towards the Caribbean coast. This dispersed settlement pattern is distinctive of many lowland indigenous groups practicing slash-and-burn rotation horticulture (Balée Citation1989; Erickson Citation2003; Oliver Citation2008). Pimentel described the villages as being small in size and composed of from three to six houses. This pattern of nucleated rather than single communal house village structure is consistently described for many ‘nations’ of the Caraca,Footnote24 both inland and in the littoral zone. However, some collateral documentary sources describe round dwellings used by certain coastal communities (Rivas Citation1994, 177), perhaps analogous to the large multi-family churuata hut of the Ye’kuana Cariban speakers from southern Venezuela (el ëttë in Barandiarán Citation1979). Sanoja and Vargas (Citation2002) have examined archaeological remains of indigenous housing structures from the sixteenth century in Caracas.

The average number of indigenous villagers in north-central Venezuela may be estimated by taking note of modern-day Carib communities in Guyana which feature a mean of 30 and rarely exceed 50 (Rivière Citation1995, 198). Considering the ongoing warfare between the autochthons and the Spanish in the former region in the late sixteenth century, it seems probable that villages maintained a certain population below which they became too vulnerable to attack. Pimentel (Citation1964) seemed to suggest that small villages (barrios) inhabited by both kin relatives and non-kin co-residents clustered to form larger units (poblaciones or pueblos), separated by larger distances. Biord Castillo (Citation1995, 185) considers barrios sections or parts of a single village which he calls a pueblo. The larger social-political units (poblaciones or pueblos) were located at intervals of 2.7, 5.5, 11 and 17 kilometers from each other (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 202; Rivas Citation1994, 187). Temporary huts were also constructed close to the cultivated fields. Generally, this spatial organization fits well into the model of Carib social structure (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 187; Citation2005).

Pimentel (Citation1964) considered the villages ephemeral. They were not geometrically arranged and the houses were made of perishable materials instead of stones and bricks. The notion of civilization was inseparably linked in Pimentel’s mind (as in many of his contemporary Spanish writers’ mentalities) with the ability to build European-like cities (Fernández-Armesto Citation1987, 235). Regardless, his data permit us to infer that the indigenous peoples were semi-sedentary groups whose mobility patterns were associated with seasonally driven shifts in the location of their cultivated fields. The settlements of modern Guiana Caribs have an average duration of about six years due to exhaustion of food and raw materials in the vicinity, infested thatches, or misfortune (e.g. the death of the village leader) (Rivière Citation1995). Population mobility between settlements and the nucleation of settlements as a defensive response to warfare (Redmond Citation1994) also likely underscored the nature of their perceived ephemerality. It can be inferred from Pimentel’s Relación that temporary campsites of the coastal groups were also scattered on the islands of Las Aves, Los Roques, La Orchila and La Tortuga (Antczak and Antczak Citation1999; Citation2005; Citation2006; M. M. Antczak and Antczak Citation2015; Antczak, Antczak et al. Citation2017; Herrera Malatesta Citation2011; Rivas Citation1994).

Subsistence economy

The indigenous peoples in the interior valleys of the Caracas and Tuy Rivers were slash-and-burn horticulturists. According to Pimentel (Citation1964), their staple crops were maize (Zea mays L.), bitter manioc (Manihot esculenta C.) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) (Biord Castillo Citation2001; Citation2005; Rivas Citation1994). Their ability to produce manioc flour cakes (cassava) was exploited to supply food destined for the agricultural production units adjacent to the encomiendas (Rivas Citation1994). Other cultigens such as peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) and beans were of secondary importance. Pimentel stated that such fruit trees as the avocado (Persea americana), guava (Psidium sp.), mamone (Talisia hexaphylla), soursop (Annona muricata), mammee apple (Mammea americana) and anone (Annona sp.) were purposefully harvested and, perhaps, cultivated (Pimentel Citation1964, 129–30). Other ethnohistoric sources confirm the cultivation of fruit trees by other Cariban speakers to the east (Caulín Citation1966 [1779], 1:42–53; de Civrieux Citation1980, 155). The indigenous peoples also cultivated bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), cotton (Gossypium sp.) and tobacco (Nicotiana sp.) as well as a regional variant of coca (Erythroxylum sp. [Rivas Citation1994, 161–62]). Coca leaf with a high content of alkaloids served as a stimulant. Many indigenous peoples valued coca leaves; it comprised an important item of trade for Cariban-speaking societies. The leaf was dried and ground into powder, mixed with pulverized burnt shells and chewed by all adult members of Cariban-speaking groups along the Venezuelan coast (López de Gómara Citation1979 [1552], 295; Pimentel Citation1964, 131). De Civrieux (Citation1980, 166–68) reported that the Cumanagoto imported coca from the north-central part of Venezuela—principally from the Tomuza, the eastern neighbors of the central indigenous peoples. One of the few indigenous species of Erythroxylum currently reported for north-central Venezuela could have been the one the Tomuza cultivated and bartered (Pittier Citation1926, 255). Cultivated fields were located close to riverbanks, their entrances protected by buried and poisoned sharp points. Although the indigenes did not store their foodstuffs, they preserved manioc flour in the form of casabe cakes (Pimentel Citation1964, 126). If fish or molluscs were bartered from the coast to the interior, they were probably salted and sun-dried or smoked (Antczak and Antczak Citation2006). The Cariban-speaking Cumanagoto to the east smoked maize kernels, which preserved this important staple for a year (de Civrieux Citation1980, 156). The indigenes prepared a beverage of great value in their diet called yare from the boiled poisonous juice of the bitter manioc. They also drank fermented maize or manioc beverages called masato (Pimentel Citation1964, 126).

As with most indigenous peoples in the South American lowlands, hunting and fishing accounted for the most protein in the north-central indigenous peoples’ diets (see Gross Citation1975; Roosevelt Citation1991). They hunted a wide range of Neotropical mammals with bows and arrows (Dupouy Citation1946; Laffoon et al. Citation2016). Subsistence activities also included the gathering of wild fruits, medicinal plants, vegetal fibers, honey, wax and natural colorings (Rivas Citation1994, 171–74). Coastal groups captured marine fish, lobsters and turtles while collecting molluscs as well as salt from natural salt pans located on the coast and offshore islands (Antczak and Antczak Citation2005; Citation2006; Rivas Citation1994, 177, 180, 189).

Material cultureFootnote25

The material culture of the north-central indigenous peoples shares many features with other Cariban-speaking groups to the east, principally the Cumanagoto (de Civrieux Citation1980). However, certain differences must have existed between inland settlements and those on the Caribbean littoral due to the different habitats and subsistence economies. For example, the inhabitants of the coast engaged in fishing using canoes and fishing gear; they also collected salt. Pimentel’s Relación provides a very rich database regarding the material culture of the north-central indigenous peoples which will be thoroughly cited in this section.

The women wore the guayuco, a short cotton skirt, and adorned themselves with necklaces made of beads (see Guzzo Falci et al. Citation2017a and Citation2017b). Sometimes they used gold pendants and bracelets. Their legs were tied in different places with colored bands to modify them for aesthetic purposes. Both women and men wore tied colored cotton armbands and painted their bodies. These adornments and modifications would also have been markers of social status, age and group membership. The men wore no clothes. They used penis sheaths made from the mature and dry fruit of a bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria). Chiefs might hang gold anthropo- or zoomorphic figurines around their necks and use golden bracelets. The coastal chiefs Sacama and Niscoto offered Fajardo gold pendants (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982). These objects, named aguilillas (little eagles) by the Spaniards, were made of alloyed gold, silver and copper (guanín). They were often mentioned as booty or the result of barter between the Spanish and the indigenous peoples of the Venezuelan coast (Antczak et al. Citation2015). Guanín objects were probably obtained through down-the-line exchange with coastal communities in the northwestern region of modern-day Venezuela and northeastern Colombia. Locally available gold could have been bartered westwards with other communities which further elaborated it. Alternatively, it might have been worked locally (Rivas Citation1994, 190, 478). In warfare and on ritual occasions, chiefs and prominent warriors wore feather headdresses and animal skins. They used masks and engraved wooden animal figures during feasts. Their weapons included hardwood clubs called macanas; these were often engraved and painted. Another common weapon was the bow with poison-tipped arrows. They wove cotton materials and hammocks as well as a variety of cotton threads and ropes. They also manufactured a wide range of fiber cordage. Pimentel mentions a special type of basket called cataure used by women for all portable possessions. Each cataure was interred with its owner when she died.

Although Pimentel mentions spoons, water containers and penis sheaths made of bottle gourd, the indigenous peoples probably produced a much wider range of utensils from this versatile fruit. These utensils must have been omnipresent in indigenous settlements and houses. Except for a small olla or pot used for storing the substance for poisoning arrow tips, Pimentel does not mention other ceramic vessels. Nevertheless, such vessels must have existed, complementing the ceramic griddles employed for baking manioc cakes. Some sources report that communities located on the north-central coast bartered for decorated pottery which struck them as especially attractive. Further into the colonial period, at haciendas located near sites with encomiendas, indigenous peoples produced ceramic molds for papelón (unrefined whole sugar cane; Rivas Citation1994, 176).

Indigenes used yellow, gold, purple, black and red mineral dyes as well as vegetable colorings. The last two hues were used to paint the human body. Body paint was sometimes applied over a previously administered base of resin called orcay ymara. This resin was obtained from the carapita tree (Carapa guianensis). There are still a few modern localities called Carapita around Lake Valencia (Botello Citation1990, 36). In battle, the indigenous peoples here under study used various musical and signaling instruments including drums and aerophones such as shell trumpets (caracoles [almost certainly made of Lobatus gigas shell]). They also employed fotutos, long cane flutes like those used by Cariban speakers from the Middle Orinoco River (Gilij Citation1965, 2:228–29; Carrocera Citation1968, 3:438). Apart from the use of wood in residential structures, collateral sources allude to dugout canoes (Rivas Citation1994).

Sociopolitical organization

The indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela lived in small multi-house villages populated by closely related extended families and probably a certain number of non-consanguineous co-residents (see Heinen Citation1983–1984 for a pertinent example of Ye’kuana households). Exceptionally, villages would have been larger (Pimentel Citation1964, 118). These bigger villages, contrary to those of other Cariban speakers (Dreyfus Citation1983–1984, 43), were probably led by skillful aggrandisers, not renowned war chiefs (Rivière Citation1995, 191; Hayden Citation1995). The village of Guaicaipuro, the main war chief of all indigenous peoples confederated against the Spanish invaders, was clearly not a big village (Nectario María Citation1979, 135; Oviedo y Baños Citation1982).

The data suggest that clusters of small kin-related villages formed major territorial units and were interconnected by strong social and ideological linkages as well as by a common dialect. Since indigenous peoples used kin relations to structure their sociopolitical organization, both economic inter-household and, probably, inter-communal links were arranged into chains of reciprocity derived from such relations. Such was the case in other Cariban-speaking societies (e.g. Butt Colson and Heinen Citation1983–1984). This type of social organization could explain the initial success of Francisco Fajardo’s expeditions. His family ties extended to several indigenous leaders of the Central Coast (Montenegro Citation1983; Rivas Citation1994; Citation2002).Footnote26 Whether these larger political units encompassed heterogeneous ethnic groups is not possible to determine based on the available historical data (Biord Castillo Citation2001; Citation2005).

Indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela could have participated in the greater Cariban-speaking network of mutual interdependence via barter, marriage, ceremonial cooperation, war alliances and shamanic services exchange (see Villalón Citation1983–1984 for an example of E’ñapa [Panare] regional interactions). Moreover, Cariban political integration can even be tracked on an inter-regional scale through links of diverse nature and intensity. Biord Castillo (Citation2001; Citation2005) suggested that the sociopolitical structure of these groups (inferable from Pimentel and Oviedo y Baños) was very similar to the social structure model proposed by Morales Méndez and Arvelo Jiménez (Citation1981) for Cariban-speaking societies in the inter-ethnic system of the Orinoco River Basin and its contiguous areas (Arvelo-Jiménez and Biord Castillo Citation1994; Biord Castillo Citation1985; Citation2006; Biord Castillo and Arvelo Citation2007; Gassón Citation2007; Heinen and García-Castro Citation2000; Tiapa Citation2007). He further argued that the groups on the eastern and central Venezuelan coasts could also have been integrated into such a system (Biord Castillo Citation1985, 180). However, not only Cariban speakers participated in these interregional spheres of interaction (Dreyfus Citation1983–1984). Rivas (Citation1994, 189–90) reported that goods were exchanged between north-central indigenous peoples and other communities located to the west who had access to certain types of worked gold and decorated pottery (possibly including polychrome) most probably obtained through the intermediary Arawakan-speaking Caquetío from modern-day Falcón State.

Brizuela (Citation1957 [1655]) stated that Cariban speakers from the eastern coast (the Cumanagoto and their neighbors) ‘have a communication and trade […] with these from the inland that live toward the plains [llanos] and that these [inhabitants of the llanos have communication] with the Caribs and the other nations that live on the Orinoco River’ (de Civrieux Citation1980, 166–72). But alliances shifted frequently. As a result, Cariban speakers often confronted each other in battle (Da Prato Perelli Citation1981).

In an alternative interpretation influenced by archaeological data other than those related to specific ethnohistorical evidence, Vargas (Citation1990) suggested that the links of interdependence between communities along with the subordination of different groups under one leadership in the sixteenth century may reflect the existence of pre-Hispanic chiefdoms or lordships. However, this type of sociopolitical organization appears to be rare among Cariban-speaking groups (except perhaps for some northeastern coastal communities, e.g. the Palenques) in the context of the colonial penetration. It suggests a new reorganization that largely emerged as a response to European aggression; it does not necessarily support the continuation of an existing pre-Hispanic system. Using lexical evidence contained in sources collateral to the Relación, we may argue, however, that relations of production under conditions of servitude (improperly called ‘slavery’ by Europeans) existed among the north-central indigenous peoples. These relations were like those reported during the colonial period among the Kari’ña, and more recently including up to the present among the Ye’kuana and Pemón. They involve the recruitment of other ethnic groups for use as manpower in horticulture and other subsistence activities. Such persons were denominated macos or itotos (Rivas Citation1994; Citation1997; Citation2001). Also, at least in some sectors of the north-central area, primary and secondary community leaders appear to have coexisted. This is a form of social organization reminiscent of other Cariban-speaking groups in the Guyana region (Rivas Citation1994, 208–9). Likewise, at least one anthroponym that includes the tiau root has been recorded. It corresponds to the figure of a regional leader in an area where pre-existing Arawakan speakers could have been assimilated. This root in the western part of the country was applied to cacical leaders (Rivas Citation1994, 254). All in all, this more hierarchical form of social organization could have evinced some of the peculiarities that led Vargas (Citation1990) to propose the existence of a particular social stratification. Unfortunately, given the fragmented nature of the written documentation, it is impossible to know how widespread this form of economic and social organization became.

The small residential unit or household (sensu Wilk Citation1991) was the basic arena for production and consumption as well as for a wide range of activities, not all of which were strictly economic. Each household had its headman. Every village had its own leader whose kin relatives are termed in collateral sources as periamo (Biord Castillo Citation2004; Citation2005; Rivas Citation1994). This term of Cariban origin is cognate with words from the Chaima and Cumanagoto languages which were translated into Spanish as pariente (relative) (Rivas Citation1994, 203, 246). The prestige of a leader stemmed mainly from the horticultural productivity of his household. However, as with other Caribs, village leaders’ oratorical abilities, knowledge of the ancestral tradition, and skills in the management of rituals and social relationships probably surpassed those of the other headmen (de Civrieux Citation1980, 141 for the Cumanagoto). As has been reported about other Cariban speakers, a shaman (piache) closely assisted the village leader. The leader’s power was limited by the existence of councils composed of village elders.

In peacetime a leader’s mandate did not extend beyond his own village (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 207), but one chief could assume the command of a confederation of warriors forming wide intercommunal or regional alliances in times of conflict. Such a confederation meant a sudden and radical change in social structure. For example, the rise of Guaicaipuro as the main chief of the confederated north-central indigenous peoples in 1568 occurred when the Spaniards threatened the survival of all the inhabitants of the region. However, even in such exceptional conditions, Guaicaipuro’s authority was not absolute; instead it depended on his power of verbal persuasion (Biord Castillo Citation1995, 208). War councils of several chiefs to discuss military strategy were associated with intensive shamanistic ritual activities (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982).

The indigenous peoples of north-central Venezuela could attain social status in three different ways. Pimentel (Citation1964) placed the shaman at the top of the ladder. The shaman as a ‘man of power’ and a ‘man of prestige’ (Dreyfus Citation1983–1984, 46) could amass influence transcending communal and even regional borders (de Civrieux Citation1980, 141; Reichel-Dolmatoff Citation1986, 136). Old women could, exceptionally, be shamans as well among the north-central indigenous peoples (Oviedo y Baños Citation1982, 541). The emphasis on their age may relate to the fact these indigenous groups believed that menstruation negatively affected some ceremonial practices and even the production of certain materials such as poisons (Rivas Citation1994, 177–78). Below the shaman came the village (a group of kin-related households) leader. He had to be a ‘good farmer and [the person] who organized many borracheras [drunken bashes] and had many women, daughters, and sons and daughters-in-law […] from these comes any good [kin] relation, and they obey him as their highest-ranking relative’ (Pimentel Citation1964, 125).

The sources provide no data regarding inherited leader status. However, Cariban speakers from the eastern coast of Venezuela used to inherit this status even though lineage could be overridden by other requirements (de Civrieux Citation1980, 144). Sons succeeded their fathers when the community agreed. Another means of achieving social status was demonstrating exceptional bravery. Special rites were performed for those warriors who killed enemies in battle. These warriors were ranked as a function of such achievements. They received a new name after each slain foe as well as a number of feathered headdresses (Pimentel Citation1964, 125).

The above data suggest that a dual system of leadership existed among the north-central indigenous peoples. In peacetime, a community leader was that figure among the household headmen who most generously redistributed a major quantity of wealth such as foodstuffs and beverages. In wartime, the most highly ranked military chief centralized authority in his own hands. This chief and higher-ranked warriors were easily recognized by the gold ornaments, animal skins, feather headdresses and probably specific and unmistakable body paintings inherent to their status. The specific sociopolitical mechanisms involved in the processes of centralization and decentralization of authority remain unknown (see Oliver Citation1989, 290–94, for similar processes among the Caquetío).

Rivas (Citation1994) and Biord Castillo (Citation2001), based on Pimentel’s and Oviedo y Baños’s data, concluded that the north-central indigenous peoples operated not hierarchical but egalitarian societies. They considered that stratification could have resulted from the occasional rise of political or economic interests.Footnote27 The examples of cooperation and liberal communitarianism of labor among the indigenous peoples described by Pimentel, as well as among the Cumanagoto (de Civrieux Citation1980, 150–52), tend to confirm a rather widespread egalitarianism on the part of sixteenth-century Coastal Caribs. Other scholars have revealed quasi-egalitarian social relations among other historic Cariban-speaking societies (Butt Colson and Heinen Citation1983–1984). However, both Pimentel’s and Oviedo y Baños’s chronicles contain some specific data suggesting that certain indigenous groups of north-central Venezuela can be considered transegalitarian rather than truly egalitarian societies (Antczak Citation1999; Hayden Citation1995; Feinman Citation1995).

Notion of certain socioeconomic inequalities among the north-central indigenous peoples may derive from Pimentel’s description of their mortuary practices. He distinguished different mortuary rituals for deceased shamans and ‘well- [kin] related’ individuals (Rivas Citation1994, 206; Citation2002, 129–30). Pimentel did not refer directly to the funerals of leaders, but these ‘well-related’ individuals likely were the village leaders. Their social position may have roughly resembled the Melanesian Big Man institution (Sahlins Citation1963). Dreyfus (Citation1983–1984) suggested the Big Man leadership type for the Kaliña and Kalinango Cariban speakers. The same notion was taken up by Oliver (Citation1989) for the Barquisimeto Caquetíos and, perhaps, for the Caquetíos from the Coro area. However, the use of this notion has been questioned by historians (Ramos Pérez Citation1978) and contested by Caribbean archaeologists (Boomert Citation2000; see also Whitehead Citation1988). Biord Castillo (Citation2001, 134) considers that north-central indigenous peoples’ social organization corresponds more to the primus inter pares or first-among-equals model. This means there was no coercive power in the hands of dominant chiefs or institutions. Morales Méndez and Arvelo-Jiménez (Citation1981) maintain that prominent individuals among the Cariban-speaking Pemones, Ye’kuanas and Kari’ñas may have been the war chiefs (jefes guerreros) or elders rather than the Big Men figures. In any case, a qualitative investigation of this trans-Pacific resemblance, with all due caution against stereotyping (Oliver Citation1989, 291), necessitates deeper levels of analysis in future research.

Pimentel also noted that the north-central indigenous peoples recognized the institutions of marriage and divorce while practicing polygamy. A man could have as many women as he could sustain; however, ‘if the husband is not a good farmer,’ it was easy for a wife to leave him (Pimentel Citation1964, 124). If the husband was producing fewer foodstuffs than others, he could not attract and sustain enough women to have numerous offspring; in consequence, he could not come to control a large household. Therefore, the social prestige of the village leader and of his household, as well as the number of the latter’s members, were directly tied to the household’s productivity. Men aimed to acquire many family dependents, especially sons and daughters-in law. Rivière (Citation1983–1984, 357) has stressed the role of marriage in both the economy and the continuity of power through alliance structures in Cariban-speaking societies. Becoming affiliated with the household of one of these affluent and ‘well-related’ men could have been the aspiration of those in other households. These aspiring individuals, consequently, would have been buttressing the practice of family-arranged marriages. In the process they were enhancing socioeconomic inequality between households because over time only a small number of wealthy and high-status households would come to exist (see Arnold Citation1995, 97; Blanton Citation1995). Pimentel (Citation1964) seems to suggest that certain household headmen might have been able to manage their family members (whose obedience they could count on) so successfully that they were able to amass production surpluses. These in turn enabled them to give status-enhancing feasts or borracheras that were purportedly meant to attract yet more dependent sons and daughters-in-law to strengthen alliances and raise the social status of the ‘well-related men’ within and beyond the community (Dreyfus Citation1983–1984, 43–44). However, the limited amount of evidence constrains further analysis of possible socioeconomic inequality among the north-central indigenous peoples, especially among their inland groups. Given the constraint posed by ethnohistoric data, it is reasonable to conclude that indigenous leaders maintained their authority and alliances not through retaining economic wealth but instead through redistributing it back to the community during communal feasts (Oliver Citation1989, 291). This was a strategy tending to equalize social position rather than generate hierarchies (sensu Weiner Citation1992) which depend on inalienable possessions. Such strategies require further investigation (see Mills Citation2004; Antczak and Antczak Citation2017).

Warfare

Somewhat concealed in the Relación is the inter-group animosity and warfare. Pimentel (Citation1964, 118) attributed the fall in the indigenous population of north-central Venezuela to not only the effects of the European conquest, but also ‘the weariness [desasosiego] of their past wars.’ The warlike character of the north-central indigenous peoples might not have been restricted only to Cariban speakers (Arvelo Citation1995; Oliver Citation1989; Rivas Citation1989; Redmond Citation1994). De Civrieux (Citation1980, 172; see Chagnon Citation1968) suggested that fighting among the southerly Yanomamö groups can be viewed as the last vestige of a widespread pattern of pre-colonial warfare in Venezuela.

The poisoned sharp stakes buried at the entrances of cultivated fields (denominated potuco) were intended for humans as well as crop-damaging animals. The same stakes were placed on certain roads or tracks and near houses (Pimentel Citation1964, 125). Oviedo y Baños (Citation1982, 2:446) mentioned that during the area’s conquest in 1568, Diego de Losada found a series of villages (pueblos) he called Estaqueros featuring a ‘great quantity of poisoned stakes and spines which were sprinkled in the tracks [of this area].’Footnote28 If cultivated fields were equally or even better protected against humans than the villages, then presumably the prime reason for inter-group warfare was access to the best horticultural areas. Oliver (Citation1989, 292) reported warfare due to pressure of this kind among the Caquetío around Barquisimeto. However, the protection of villages and fields could have intensified in early colonial times as a measure against the Spanish intruders (traders, raiders and slavers). Depending on a variety of circumstances, the armadas de rescate sometimes raided indigenous communities, sometimes pillaged them, and sometimes bartered with them—frequently with an intimidating show of force.

Oviedo y Baños (Citation1982, 2:547) provided another possible explanation for the warlike character of the north-central indigenous peoples. He held that fierce Cariban-speaking raiders (Kalinago/Kaliña from the Lesser Antilles) periodically assaulted these peoples in search of slaves (Da Prato Perelli Citation1981; Dreyfus Citation1983–1984; de Civrieux Citation1976). The north-central indigenous peoples are portrayed in this account as people victimized by the ‘cannibals’ attacking them from the east and northeast, although this may have occurred at the onset of the colonial period only. It is impossible to infer only from the ethnohistoric data whether the coastal indigenous groups were themselves engaged in raiding expeditions.

Historic Cariban-speaking societies were observed implementing the strategy of marriage alliances between various villages. This committed the parties to mutual assistance in wartime (de Civrieux Citation1980, 173). The political importance of marriage was characteristic not only of Cariban-speaking societies. As Oliver (Citation1989, 281) and Ramos Pérez (Citation1978) noted, ethnohistoric sources show that Manaure, who was a supreme authority of the Arawakan Caquetío chiefdom in present-day Falcón State to the west of the north-central territories, was married to ‘daughters of the Caribs.’ This was in order to gain prestige and influence beyond his own ethnic and political boundaries, as well as to procure allies to support him when war threatened (Rivas Citation1989, 2:398–400).

A critical reading of the historical documents is pivotal here. A case in point is Biord Castillo’s (Citation2001, 168) observation that the marked differences between the major emphasis on indigenous bellicosity posited by Oviedo y Baños, as compared to Pimentel’s previous much milder characterization, could well be due to the fact that the two treated widely separate time frames. Attention to context could well account for the apparent contradiction.

Exchange

Despite some data related to the network of indigenous ‘markets’ (Biord Castillo Citation2005; Citation2006; Biord Castillo and Arvelo Citation2007; Rivas Citation1994), we know little about exchange conducted by the north-central indigenous peoples. Golden pendants in the form of birds probably reached the area from northeast Colombia (Antczak et al. Citation2015). Although Pimentel did not mention local manufacture of these objects, there is some lexical toponymic data that seem to indicate the indigenous population knew of veins of gold situated close to their communities, especially in the mountains to the southwest of the Valley of Caracas (Rivas Citation1994). These corporal adornments may be considered indicators of social status or wealth inequalities or both among families within the same community and among individuals within the same household. Pearls were exchanged for gold or guanín objects in addition to pottery at certain sites along the coast during barter fairs (Rivas Citation1994). In early colonial times, north-central indigenous peoples used gold objects for exchange with Spanish explorers. Other imported items would have been medicinal plants, rare colorful feathers (Antczak, Antczak et al. Citation2017), and the poison for arrows known as curare (see de Civrieux Citation1980, 210–11). Biord Castillo (Citation1995, 89) and de Civrieux (Citation1980) demonstrated that hammocks would have been the most valuable exchange items produced in the north-central region for export beyond its regional boundaries. Other exports could have included cotton material and blankets, baskets, maize, casaba (manioc cakes), honey, black wax and natural colorants. Coca (Erythroxylum sp.) leaves may have been bartered to the eastern groups (de Civrieux Citation1980). Long-distance exchange has been documented among the ethnographically known Cariban speakers of southern Venezuela (Coppens Citation1971).

The data suggest the regular exchange of goods between the inhabitants of two sharply different ecological systems: the Caribbean coast and the interior mountains and valleys. Marine products such as salt, fish, and oil extracted from marine turtles were exchanged for vegetables and fruits from the interior. Pimentel (Citation1964, 119) wrote that ‘these [inhabitants] from the interior go with the edible goods to the sea [shore] to […] exchange the salt and the fish for what they bring [with them].’ Exchange between the coast and inland inhabitants has been documented for almost the whole of the Venezuelan maritime coast from Lake Maracaibo (Sanoja Citation1969) to the farthest eastern shore (de Civrieux Citation1980). Remarkably, up to three or more tons of sun-dried or salted (or both) Lobatus gigas meat was brought yearly to the north-central Venezuelan mainland from the oceanic islands of the Los Roques Archipelago for at least three centuries before the Spanish conquest (Antczak and Antczak Citation2006).

The above-mentioned examples do not permit a clear temporal-spatial distinction between the exchange of alienable objects among indigenous peoples in a state of reciprocal independence, and gift exchange of inalienable objects between individuals submerged in reciprocal dependence. Therefore, we cannot draw a distinction between quantitative and qualitative relationships (sensu Gregory Citation1982). We can only hypothesize that certain individuals and higher-status households could develop and maintain wide regional contacts while others bartered locally. We can further hypothesize that by restricting the circulation of prestigious and inalienable goods (e.g. certain guanín adornments and pottery figurines), high-status households or individuals (e.g. leaders) could emerge. Yet the contrary could also have been true: the keeping of some of these ‘cosmologically authenticated’ goods (Weiner Citation1992) could have been used to defeat hierarchy (Mills Citation2004). Future research can further disclose the role of north-central Venezuela as an entrepôt in the far-flung interregional system of exchange in northeastern South America and the insular Caribbean (Antczak and Antczak Citation2006; Citation2017; Hofman et al. Citation2008).

Shamanism and feasting

Pimentel provides unique information about ideational aspects of indigenous north-central Venezuela soon after the Spanish conquest. Although the Relación is strongly tainted by the premises of Europocentric Catholicism, it provides an exceptionally detailed description of shamanic practices as well as the social position of the shaman within indigenous society. It also offers a picture of the ceremonial interaction among humans, other-than-human entities, and objects which—although painted by the thick brush of the Western ‘painter’—results in a vibrant portrait, one suitable for further elaborations.

The north-central indigenous peoples had no sanctuaries, specific houses or places dedicated to the adoration of supernatural beings. Nonetheless, Pimentel alludes to the association of specific spirits with certain natural places and phenomena. For example, he saw the indigenous peoples as pagan wrongdoers who worshipped demons.Footnote29 Coastal and northern Cariban speakers associated the fox with a certain category of spirits; this is borne out in the toponymy and anthroponymy of their words denoting fox. Catholics identified these spirits as satanic (Rivas Citation1994; Citation2002, 112). Only a few shamans or piaches were known in the whole of north-central Venezuela region during the sixteenth century. They inspired a level of respect and reverence among the commoners.Footnote30 Pimentel provides a detailed description of the transformation process and practices attributed to piaches. Candidates began their apprenticeship at 14 or 15 years of age. During their training, each apprentice was enclosed in an especially furnished room inside the hut of a piache. He could not talk to anyone. He could leave the house to do his chores but always had to return to the room of seclusion. The seclusion lasted for 20 or 30 days and was coupled with near-fasting. Solely a daily vase of maçato, a fermented beverage made of maize, sweet potatoes and cassava, was permitted him. From time to time during the night, the piache could enter the room of the apprentice and they would sing together. Pimentel remarks that they sang ‘with vanity and presumption’ in a guttural tone (cantando de papo), and that it was almost impossible for commoners to understand what they were saying. In fact, the piache was explaining to the disciple the words he used to invoke the spirit. The disciple ended his period of seclusion and fasting very thin.

Once the seclusion was over, a great ytanera feast was convoked with the participation of many invitees from neighboring settlements. The parameters were common to all north-central indigenous peoples’ feasts presided over by the piaches. Days before, large quantities of maçato were prepared. Invitees drank this beverage until they fell to the ground. Those from neighboring settlements came in groups anointed with a certain genre of resin called orcay and mara similar to turpentine. A vegetal paint was then applied on top of this ointment or directly onto the skin. This paint was a kind of bermellón (a reddish dye) called bariqueçaFootnote31 made of leaves and tree bark. The invitees also wore masks. Pimentel sarcastically remarks that those wearing the most ‘horrible’ masks were considered the most gallant. Some participants brought figuras del diablo, or devil-figures as Pimentel described them. Unfortunately, he did not describe these spirit-figures. They were likely wood carvings adorned with bark, fiber, feathers, and paint, and could have shared some material characteristics with the bird and other animal figures that were also brought by the invitees. These latter images were fashioned from wood and colorful threads of cotton and fiber. They were affixed to wooden clubs or sticks to help the humans imitate the suggested animals.

Pimentel goes on to describe the vivid choreography of the ceremonial part of the feast. The masked participants, their bodies painted, held colorful depictions of spirits, birds and animals as they entered the hosting house of the piache. The performance which ensued involved imitation of the most characteristic behaviours of the depicted animals. In addition, in Pimentel’s words, they staged some ‘other simple inventions.’ These semi-improvised acts creatively intertwined dancing, singing, and the strumming of musical instruments producing a vibrant, colorful, and richly multisensorial experience.

The pivotal part of the ceremony, however, belonged to the piache. He likely sat on a wooden bench surrounded by the crowd. Then he began to speak unintelligibly with, according to Pimentel, ‘vanity and presumption.’ This monologue was a necessary prelude to the state of visajes or ecstasy. The audience understood that the piache was calling the spirit. When he began to tremble, all knew that the spirit had entered him. Then the participants gave him the offerings they had brought. These were largely diverse kinds of food that the donors presumably understood were going to the spirit, not the piache. Possessed by the spirit, the piache talked to the participants ‘as a person that came from far away.’ Those present understood that it was the spirit who was speaking, not the piache. Thus, the participants began to ask for various favors such as rain and a good harvest. They begged not to be killed or fall sick. Pimentel noted that the replies of the spirit-infused piache were generally ambiguous, open to interpretation. Different spirits had proper names; sites where they dwelled also had names. Some were water and maize spirits. Others represented diverse diseases and ailments such as calenturas (fevers) or camaras (diarrhoea) of which many indigenous peoples were dying. Pimentel believed that some held piaches in low esteem and even laughed at them, considering this ceremonialism no more than an empty tradition inherited from their ancestors. He bluntly concluded that some feasters were less attracted by the shamanic séances than by their flawed and dishonest inclinations to overindulge in food and beverage.

Apart from invoking the spirits, the piaches also acted as hechiceros (sorcerers or medicine-men) and herbolarios (knowers of herbs and medicinal plants). These occupations brought them additional respect and fear. During a healing session they would blow and puff at the afflicted person, rubbing their hands on the place where the patient reported pain, which they would also treat with herbs. In addition, they would suck at the place of the pain, spitting out the saliva afterwards, arguing they had removed the sickness. One of the plants specified as having medicinal properties and enjoying high esteem among the natives was tobacco. The indigenous smoked it through the mouth and ground and inhaled it through the nose to cure fever and wounds. Pimentel complained that the Spanish did not yet know how to use it well. In some cases, when the patient died, the family would beat or even kill the shaman if, with the help of the spirit, he had not fled beforehand. Alternatively, the family might take back the presents they had given the shaman.

The piaches invoked the spirits at night yet maintained they arrived in a visible manner. The entrances to a hut being closed, they argued the spirit entered through openings in the roof. The shamans would be the first to talk to the spirit, alone; then villagers could enter and ask the spirit for favors. Pimentel held that the indigenous peoples feared spirits for their power to bestow either health or death. If people ate their harvests without holding a feast and giving offerings to the spirit, they might die. The spirits were considered responsible for death, especially when it arrived suddenly. Pimentel stated that this was known to occur when indigenous peoples had failed to convidarle, that is, to entreat the spirit to join them in the feast.

Coastal versus inland societies

Pimentel (Citation1964, 136) noted that ‘the natives [on the Caribbean coast] go there [to the Los Roques, Las Aves and La Orchila offshore islands] during the months of fair weather for salt and for the turtles to eat them and to make oil from them.’ Navigation to and exploitation of resources located on the offshore islands demanded, plausibly, inter-household cooperation. Though pertinent ethnohistorical data are very scanty, Antczak and Antczak (Citation1999; Citation2006; Citation2017) hypothesized that certain self-sufficient households aggregated around the leader of the most successful such to more efficiently control and exploit highly productive marine resources, as well as to take advantage of the high demand for these resources by interior societies. There are no data referring to the existence of communal or individual rights over the resources on the central coast. However, such a reference does exist for the north-central indigenous Cariban-speaking neighbors to the east. Encroachment on hunting and fishing spots was a common reason for the outbreak of war among the Palenque on the Unare River (Castellanos Citation1962 [1589]).

According to Antczak (Citation1999), the household groups would, through time, be manipulated by a leader into more surplus-oriented units which controlled (1) information about the location of fishing grounds, mollusc beds and salt pans, as well as navigational knowledge through the open sea; (2) the production of seagoing canoes enabling access to these distant resources; and (3) exploitation processes including the bioecological knowledge and skills necessary for the procurement and processing of the resources, production and operation of fishing-related gear and the ability to manage specialized work groups. Furthermore, the kin-related household groups could have become ranked in importance and prestige relative to one another (see Arnold Citation1995, 97). Finally, they would have clustered into larger kin-related corporate groups under a main leader. Nevertheless, as we have mentioned before, archaeological grounding for the existence of this type of social organization in pre-colonial north-central Venezuela is thus far lacking.

Corporate control of subsistence resources could have evolved only on the maritime coast. The resources of the interior hills and valleys would have remained under the control of relatively autonomous extended families. The coastal societies based their economies on the appropriation of resources from both the marine (fishing and gathering) and the terrestrial (hunting and gathering) environments, as well as on the slash-and-burn horticulture practiced in the valleys or on the slopes of the Cordillera. Pimentel (Citation1964) clearly indicates that the inhabitants of the interior went to the coast (in search of marine products); but this, apparently, did not happen in reverse. Consequently, there could well have existed certain differences in social organization, power, and perhaps wealth between the indigenous groups of the Caribbean coast and the interior.

According to Pimentel, the north-central indigenous peoples were still visiting and exploiting the natural resources of the offshore islands in the early decades of the European conquest. However, archaeologists have thus far not found any European artifacts at indigenous sites on the islands. This may indicate an early colonial interruption of a long indigenous seagoing tradition that goes back to ca. AD 1000 (Antczak and Antczak Citation2006; Citation2008). Because it is from the offshore islands that we do indeed possess systematically recovered archaeological data, further research is necessary on the central coast in order to determine if Pimentel’s information could refer to a rather ‘recent’ episode of island resource exploitation, quite disconnected from the older established pre-colonial activities performed by the Cariban-speaking peoples (Valencioid) and their non-Cariban allies (Ocumaroid) (Antczak and Antczak Citation2006).Footnote32 In any event, towards the second half of the sixteenth century under the encomienda regime, the Spanish colonists exploited indigenous peoples and their knowledge of marine resources and mountain paths to exchange fish and, perhaps, salt between coastal colonial enclaves and those located inland (Rivas Citation1994, 500–1). The processes of forced transfer of indigenous peoples in the wake of armed uprisings affected the ethnic composition of some localities (Rivas Citation2002, 144). Remarkably, indigenes’ efforts to defend the remnants of their ancestral territories survived into the nineteenth century in Aragua (Morales Méndez Citation1994; Ganteaume Citation2012) and even into the mid-twentieth century in the coastal state of Vargas (Rivas Citation1994, 518–28). However, all these processes were minimally recorded especially in the Lake Valencia region (Castillo Lara Citation1977; Citation2002) and early colonial sites have barely been investigated by archaeologists.