On 10 October 1768, a group of 26 Machachi Indians, Spanish officials, landowners and other witnesses climbed together an Andean foothill to participate in a vista de ojos, a colonial walkabout ritual that intended to verify and rectify Andean-Spanish boundaries to settle a land dispute. This walkabout was especially significant because it followed tumultuous events in which the Machachi ‘llactaios’ rioted against judicial officials, shouted Quechua admonitions, and, ultimately, sabotaged legal procedures.Footnote1 The llactaios intuited the land survey taking place would harm the community, since Joseph de Carcelén, the Spanish landowner behind it, claimed a portion of their lands as his.

The Machachi land dispute brings to the forefront of cultural and legal history the manipulation of symbolic representations, images and maps, by Spanish and Andean claimants alike in an under-studied region. I argue that vistas de ojos, land surveys or mensuras and the use of legal cartography instituted a colonial mediation between Indians and the space of the pueblos de indios that accelerated the privatization of Andean communal space. Although Spanish and Andean claimants shared a variety of ways to prove possession, the Machachi Indians shaped such mediation with their own ritualization of possession, which they positioned in dialogue with Spanish law. Andeans created ‘legal arguments’ out of deploying religious symbols of land possession in the landscape, mobilizing images and displacing themselves across the disputed space. They also intended to contour Spanish land maps with their own cartographical discussions and demands for rectifying the legal procedures that constructed and de-constructed their communal space. This case broadens our understanding of the co-creation of colonial legality by Andeans and Spaniards, particularly in the transformational process of privatization of communal lands and in locations peripheral to the centers of Spanish power. This co-creation also speaks to the pluralistic and complex structure of Spanish imperial law (legal sources and expressions of possession).Footnote2

Andeanists have largely approached the change of indigenous land tenure practices under Spanish rule within the broader scholarship examining the formation of colonial haciendas and the impact of Spanish colonial institutions on indigenous societies.Footnote3 These studies documented and linked the formation of the Spanish haciendas to the loss of indigenous lands at the hands of Spanish landowners. On Andean Ecuador more recent regional and micro-level studies have focused on the northern and southern Ecuadorian regions during the long span of precolonial and colonial times (Salomon Citation2007; Poloni-Simard Citation2006; Caillavet Citation2000). At the crossroads of historical anthropology, political economy, and social history, scholars rendered in-depth ethnohistorical monographs that treat Andeans and their societies as diverse and genuine colonial actors.

Despite notable exceptions, however, the dearth of studies on indigenous land tenure transformations is noticeable for the specific region of Machachi and the central Inter Andean valleys south of Quito. Sharing the Marxist-structuralist analytical approaches of the 1960s–1980s, the socioeconomic studies of Borchart de Moreno (Citation1980; Citation1998) and Moreno Yañez (Citation1980) offer microlevel data and analysis supporting the transformation of Andean land tenure as an increasing transfer of indigenous individual and collective lands to consolidate private Spanish estates. This development took place within the larger process of ‘original accumulation of capital,’ and through land appropriation and labor control.Footnote4 Valuable as these contributions were in their time, however, they remain constrained to a dichotomic view of colonial relations in which Andeans appear as utterly dependent on and exploited by Spaniards, and indigenous individual and collective interventions in the cultural and legal arena are rendered mute and, ultimately, powerless. For the region in question, little attention has been paid to the use of Andean cultural expressions performed in the landscape and their impact on the ways Spanish law was extended and redefined in remote locations of Andean America.

A closer reading and contextualization of land disputes in the Andean pueblos de indios that attends to the use of performative language and legal ceremonial movement across the agropastoral space illuminates little known ways in which Andeans understood and expressed possession in far-flung settings under Spanish rule. Simultaneously, Andeans’ legal actions performed in the landscape take on a deeper meaning when placed in conversation with the legal strategies of more powerful Spanish landowners in the courtroom. When challenging such strategies with discursive cartographic interventions in court, Andeans attempted to re-map textually their own ethnic space. They thus partook of an ongoing relationship of ‘intertextuality’ and in a kind of ‘spatial strategy’ also practiced elsewhere in colonial Latin America. In discussing discursive and spatial practices of mapping embedded in written texts, Yannakakis (Citation2008a, 164) points to a relationship of ‘intertextuality’ between various separate but ‘mutually constitutive’ spatial practices in colonial Oaxaca. Likewise, Hidalgo (Citation2012) argues that ‘spatial strategies’ by colonial Mixtec Oaxacans expanded the use of maps, witness testimony, land titles, and boundary inspections.

I extend and relocate these two notions, however, to show that both Andeans and Spaniards represented and secured space with a shared repertoire of spatial strategies and evidence, all of which attempted to define and deconstruct the common agropastoral space in Machachi. In this case, both parties in the dispute competed over what constituted the right to possession, ultimately dominion, and the scope and nature of communal space. Thus, this essay exposes larger sets of spatial strategies used by both Andeans and Spaniards and their intertextuality, which ultimately reveals the way Spanish law achieved hegemony in the Andes.

More comprehensively, this essay addresses hitherto unknown forms of ‘legal translation’ to discern how Andeans shaped interpretations of Spanish legal tenets and procedure in the very landscape and the court and in their own cultural idioms.Footnote5 Conversely, the discussion approaches the Spanish use of ‘legal capital’—manipulating maps as symbolic representations of space, land titles, and social networks to shape attributions of possession and inflect the outcomes of land disputes, in tandem with the counter-cartographic discourse by Andeans aimed at debunking Spanish land claims in court.

Figure 1. Map of Machachi. Courtesy of Aaron Cochran, Ohio State University, Engineering Technology Services.

About five miles south of the audiencia capital of Quito, the town of Machachi lies at the center of the five square kilometer Inter Andean valley of Panzaleo, traversed by the San Pedro River and pre-hispanic and Inca roads. Cold and humid, at about 2,940 meters high, the town is nested in a volcanic and fertile region devoted to food farming and rich in other forestry and marshy resources (Salomon Citation2007, 56; Caillavet Citation2000, 363). Culturally and linguistically, the Machachi valley’s inhabitants belonged to the complex of pre-colonial Panzaleo ethnic groups that extended from the central Highlands, north and South of Quito, down to the Pacific coast. In the late sixteenth century, the colonial pueblos of Machachi, Aliag, and Aoiassí were founded in the valley and maintained a close triangular interaction. Towards the 1760s economic recession and social unrest visited the city of Quito and the surrounding towns. The once-thriving textile industry and commerce of this region, to which Machachi had contributed, suffered from the impact of the trade liberalization policies of the Bourbons.Footnote6 Such a downturn also spread decline in the food production and markets of the region and Machachi was no exception (Borchart de Moreno Citation2013, chapter 13). While Andeans’ communal lands had decreased since the previous century, the Bourbon fiscal demands only exacerbated social discontent. A new royal tax caused most Quiteños and their neighbors in the surrounding valleys to rise up in the 1765 massive rebellion (Andrien Citation1990).Footnote7

In the Inter Andean valleys to the south of Quito, Machachi, Chillos, and Tumbaco, the composiciones de tierras triggered a prominent loss of native lands towards the late seventeenth century, after they had started only fragmentarily in 1647. By 1692, however, most land titles in the valleys resulted from composiciones. Although unsuccessfully, royal attempts to control the Spanish illegal land takeovers started under Philip II in 1591, but the results were insignificant until they began in earnest with the 1692 visita or inspection of don Antonio de Ron, the Quito Audiencia fiscal. The 1692 visita reported a majority of mid-size lands (10 caballerías [Cs] or 470 hectares [Hs]), and only 24 large estancias (local term for haciendas) with two large landowners already controlling 76.2% of the land in Machachi itself, totaling roughly 5000 Hs or 12,000 acres (Borchart de Moreno Citation1998, 102–3, 120, 123; Citation1980, 6).Footnote8

In the 1760s, indigenous property faced increasing encroachments and forced land sales combined with new composiciones. As opposed to enforcing land restitutions, the composiciones accelerated the dissolution of the communal land rights well into the late colonial period. In the end, the Crown’s financial urgencies made it more convenient to amend titles for lands obtained fraudulently than restoring communal lands (Borchart de Moreno Citation1998, 139). The consolidation of colonial landownership thus produced a ‘reserve’ of landless Indians, which supplied the labor demand of the new estates.Footnote9 Such was the case in colonial Machachi, where the joint interests of Spanish landowners and local colonial officials weighed heavily in land disputes involving Indian communal entitlements.

Contending possession: the legal power of ‘Nuestra Señora, the Mother of the Indians’

The wider land dispossession that followed the postconquest and mid-colonial years transformed unprecedentedly indigenous communities, and the ensuing expansion of colonial land ownership propelled Andeans to seek justice through legal settlements in Spanish courts. However, Andeans’ land disputes, perception, and enactments of possession in the Northern Andean region of Ecuador remain virtually non-studied.Footnote10 At the core of most land disputes was the question of posesión or possession, a Spanish legal tenet of Roman origin, generally understood as the effective use or holding of the land—which in Spanish law always took precedence over ownership claims.

Land possession was a contentious and complicated legal matter that exposed Andeans to protracted land insecurity and increasing legal costs to retain their lands.Footnote11 Although in the eighteenth century possession was still the prime validator of dominium in Spanish law, in practice, Spaniards’ property titles and landscape maps eventually superseded the Toledan-era commanding force of the protective amparos de posesión, which Andeans treasured for use in courts. In the absence of original titles and maps, Machachi Andeans used disputed communal spaces as a stage to assert their own performances of possession, disrupting the work of court officials, subverting well-established procedures of land inspection, and translating them all into a legal idiom amenable to the courts.

In 1768, the Cacica doña Basilia Pungutagsig, from the Machachi parcialidad (community) disputed Spanish landowner Joseph Carcelén’s pretensions over lands that her llactaios held in common in the sites or sitios known as ‘Puychicoto,’ ‘Batán’, ‘Cerro de Puysachua [volcano known today as Pasochoa],’ ‘San Agustín,’ and ‘Obraje.’Footnote12 Old age and health burdens moved doña Basilia to delegate the legal representation to don Francisco de Zamora, Cacique Gobernador of the Latacunga province. On 26 May 1698, at the rising time of the composiciones, doña Basilia’s grandmother, Cacica doña Magdalena Pungutagsig, filed a lawsuit for despojo (dispossession) against the Spaniard don Juan Lascano de Quevedo for encroaching ‘Cunchicoto,’ ‘Nagtimaq’ and the ‘Cerro de Puysachua.’ Doña Magdalena Pungutagsig sued Lascano again, for the same reason, on 10 November 1729.Footnote13 Doña Basilia Pungutagsig sued Carcelén for the first time on 13 November 1767, for the dispossession of the same sites.Footnote14 The court produced an amparo de posesion in favor of the Cacica, which also went unenforced, since the 1768 lawsuit reclaimed the last two sites again. Although a clear gender dynamic in the regions’ communal lands disputes is hard to ascertain, at least three Machachi cacicas (female cacical authority) from the same lineage had long faced dispossession of these lands.

In support of the cacica’s claims, the Protector de Naturales reiterated that doña Magdalena had initially received an amparo de posesión in 1698 for the sites’ names Nagsimaq and the Cerro de Puysuchua. But then don Domingo Andraca, a neighboring estanciero, claimed these two sites as his during the 1768 vista de ojos.Footnote15 He argued that, in 1759, his brother, don Pedro Andraca, had defeated the legal pretensions of doña Basilia’s mother, doña Maria Pungutagsig, over Nagsimaq.Footnote16 In 1768, doña Basilia recognized the legal vulnerability of cacicas as she delegated her legal power: ‘I beg V.E. (your excellence) […] that the said cacique be allowed to take over the defense I would otherwise do, because, besides me being a “mujer inabil” [lacking legal capacity], I am convalescent.’ She also stressed the legal disadvantage of their ethnic condition. ‘In the parcialidad there’s not even one Indian who knows how to speak the Castilian language, neither do they know how to defend themselves.’Footnote17

While the court ordered the pertinent vista de ojos and mensuras to verify the Indians’ claims, Carcelén’s lawyer challenged Cacica Pungutagsig to furnish the original title of Machachi’s tierras de repartimiento to verify sizes and boundaries. He claimed that many community lands had been sold to non-Indians.Footnote18 Indeed, since mid-colonial years, land transfers from Indians to Spaniards and mestizos transpired in myriad small and larger sales, a few composiciones, ‘donations’ to the king (lands auctioned to local landowners), donations to cofradías, or land inheritance by cacicas who married non-Indians (Borchart de Moreno Citation1980, 10–13, 15; Citation1998, 133).Footnote19 In spite of the corporate nature of communal lands, their sale was often a last resort of native authorities, who found themselves pressed to cover overdue tribute quotas, eventually jeopardizing land security in the long run.

In 1768, the unexpected appearance of court-appointed land surveyors in Batán alarmed scores of local Indian women and men. As it was clear that land mensuras were about to take place, the llactaios shouted words in Quechua and moved quickly to ‘sequester’ the officials’ measuring rope. They cut and ran away with it along the zanja (water canal), obstructing the legal procedures altogether.Footnote20 Upon learning of their agitation, Cacique Zamora prompted them to explain their actions to him in their own language. The Indians manifested their fears that the surveyors had come to wrest Batán and Puychicoto from them.Footnote21 Zamora warned the Indians that they were in trouble for having resisted the legal procedures. Apparently, they showed regret and begged the cacique to write on their behalf a memorial to the judge, in Castilian, explaining their involuntary mistake.Footnote22

The majordomo of Nuestra Señora del Rosario brotherhood, Agustín Suárez de Figueroa, with the surveyor and ‘many other white men’ persuaded the Indians that they intended no harm: they were simply conducting a customary measurement. The Machachi Indians apparently acquiesced and asked for forgiveness, reiterating that they had acted to protect their lands. In the memorial, Zamora explained the incident as a legal and cultural misunderstanding. The Indians had acted with a ‘sentimiento natural’ or idiosyncratic inclination for the imminent loss of their homeland, but they were sorry and pledged to surrender humbly to justice. As Indians, Zamora went on, they were ‘silvestres o estólidos’ [rustic or stolid], and ‘that is why the king, their captain, protects them through the alcalde ordinario.’Footnote23

The fact remained, however, that, despite all reassurances, the Puychicoto lands had been sold to Carcelén, thus confirming the Indians’ fears when witnessing the unexpected mensuras. On top of that, the judge charged against the Machachi Indians for ‘not having contradicted timely when proper notices had been issued about it.’Footnote24 Furthermore, the properties sold also included lands between the town plaza and the sites of Batán and San Agustín, which belonged to the pueblo. However ‘silvestres’ and ‘estólidos,’ as they were made out to be, the Indians attempted to recover their lands. This time around they chose to perform a land possession ceremony of their own, in front of the colonial officials and other parties present. They brought out an image of ‘Nuestra Señora [del Rosario]’ and processioned with her in a walkabout of sorts around the compromised sitios, occasionally stopping and placing the Virgin on the ground at the boundary markers. The cacique reported that ‘they carried Our Lady the Virgin in procession to the said sites, showing that, as the mother that she was of them, it was the Virgin who took possession [of the land] on behalf of the Indians [… . Therefore], she was both the true possessor and our lady, the mother of the Indians.’Footnote25

Christian Andeans also perceived the Virgin as mother earth, a nurturing and protective entity with superior authority to that of the court and Spanish law. She was the only one who could legitimately possess the land. And her children, the Indians, would be the true heirs of such possession.Footnote26 The procession was a ritualized act of possession reaffirmation, ratifying the boundaries and their markers akin to the legal vista de ojos and mensuras. Thus, even if accepting Spanish boundary-making procedures, the walkabout intended to offer Andeans’ own response to the mediating role of the surveyors, the judge, and the Spanish legal procedures standing between them and the land. This reminds one of the multiplicity of sources of law and evidence prevalent in the Spanish legal tradition as it played out in Andean America. Even though this is a microlevel study of possession from the vantage point of Machachi in the late colonial period, the cultural power dimension of symbolic images transcends the local ayllus. The deployment of Christian religious images by Andeans to reject dispossessing Spanish legal procedures exposes the larger dynamics of indigenous creative appropriation of the power of symbols for purposes that superseded the sanctioned ecclesiastical usage.Footnote27

But this visual and performative statement was not only a symbolic possession of their communal space by the Virgin ‘mother of the Indians.’ In Spanish ceremonies of land possession, it was required that those holding objections to either the measurements, the boundary markers, or to the beneficiaries of the possession came forward and expressed their contradicción or opposition in situ or in the court shortly after. In practical legal terms, what the Machachi Indians did, and which Cacique Zamora translated for the judge, was to express their contradicción with a powerful visual statement that conveyed their will to repossession on their own terms through a performance that had similar effects to those the judge would customarily conduct. Andeans thus conveyed their contradicción to the mensuras in a community language, which they probably could not explain in the technical language of the law, according to Cacique Zamora.Footnote28

The Machachi Andeans chose images and rituals of bicultural significance, effective to convey possession on stronger grounds, which also renewed the community’s own bonds in the face of colonial injustice. Nuestra Señora, the ‘mother of the Indians,’ conjured up notions of protection that carried higher moral value for Andeans than the mensuras, maps, and legal rituals of Spanish authorities and their allies. Sacred images and processions also constituted a sort of religious-legal brokerage: the Indians shifted the grounds of possession, translating the religious meaning of the Virgin into a collective legal argument. Discontent with the Bourbon disfavor of popular religious displays may have played a role in the redefinition of boundaries through religious theatre in 1768 Machachi. This theatre of possession, however, also evokes Andean spatial practices of land perambulation from pre-colonial times, reframed in colonial contexts to express collective memory, and eventually yielding colonial cartographies. A ritualized walkabout recorded on paper in 1595, made to recognize community space, produced maps upon demand of the imperial state which were adapted, engendering ‘paper-like mappings’ (Beyersdorff Citation2007, 129–60).Footnote29 While walking about with the Virgin, the Machachi Indians re-inscribed the boundaries of their communal lands, rehearsing the communal memory of Puychicoto and Batán, as inalienable lands. Although Machachi perambulations in 1768 are not necessarily exceptional, the choice of enacting possession through walking about with the Virgin as contestation to Spanish land surveys and cartographic strategies is rare in the late colonial Andes.Footnote30

Significantly, the Machachi Indians based their right to possession in no demonstrable use of the land since time immemorial (either the time of the Incas, of gentility, or since the time of conquest), as commonly argued before, but from a powerful rhetorical symbol of their present time of colonial Christianity: the motherly Virgin and her legitimizing force of Andeans’ rights to land. Rather than sourcing possession in either the Toledan-era repartimiento titles or amparos de posesión or from a more distant ethnic past, they drew on the symbol’s potential as a Christian-based legal argument, seeking common ground (legal and cultural) with the land judge and making native custom conform more visibly to the Christian basis of law.Footnote31 Cacique Zamora translated the legal rationale behind the Indians’ resistance to the mensuras and the meaning of the later procession with the Virgin as acts of possession. His rhetoric appears to endorse colonial stereotypes about Indians, depicting them as ‘rustic and stolid,’ to persuade the judge to pardon them for their transgressive performance. The cacique and the counter-performing Indians thus composed a unique canvas of cultural and legal translation strategies for the re-inscription of communal space with an Andean idiom, at times when the survival of collective lands was under imminent threat.

Mapping and space transformation

The contest over the redefinition of Andean space as a colonial domain lies at the core of the land dispute in Machachi. In contrast to the Indians’ own redefinition of possession, the Spanish opposing party set in motion sophisticated means to defeat the communal interests of the Machachi Indians. Carcelén established more firmly his land claims by the strategic use of ‘legal capital,’ or his privileged access to legal technologies and political resources unavailable to his opponents. Not only did Carcelén dispose of private attorneys, crucial notarial information and services, and membership in local and audiencia-level power networks, but he used landscape mapping strategically.

In this section I argue that Carcelén’s actions in court advanced the privatization of the Machachi lands through a combined maneuvering of legal capital: commissioned landscape maps, deeds, decrees, private legal assistance, and the ear of Quito’s Alcalde Ordinario (the judge). As the state implemented procedures that endorsed land transfers out of Andean hands, Andeans also had to confront landowners endowed with unmatched ‘legal capital.’ The use of legal cartography by Spaniards in legal disputes was not uncommon. But the Machachi dispute allows for a much-needed deconstruction of colonial legal cartography masquerading as unbiased evidence in colonial courts, which exposes the autonomy such maps acquired as legal argument in the dispossession of Andean collective landholdings.

Geographers, among other scholars, have long agreed that maps are fundamentally social constructs. Dym and Offen argued that maps are crucial instructive devices for the history of space transformation, as they explain how by way of either occupation or contestation, among other factors, spaces undergo redefinition and resignification for peoples over time (Citation2012, 3). I ponder further the role of landscape maps as strategic evidentiary artifacts in the legal conversion of Indian town lands into colonial spaces. Maps submitted to settle land disputes in court are selective descriptions of the land. They often acquired the status of evidence, empowering uncritically the map holder’s perceived entitlements. Landscape maps, therefore, are prone to erasures of the opponents’ land rights, presence, and history (Endfield Citation2001; Harley Citation2001; Jacob Citation1996; Monmonier Citation1991; Warf and Arias Citation2009). As visual renditions of space, maps also shape perceptions of reality, by producing a rhetoric of symbolic and knowledge systems that describe, interpret, and represent spatial reality. Since the early colonial years mapping was tied to the formation of landownership as petitions for mercedes de tierras or land grants were to be accompanied with a ‘pintura del lugar’ (Russo Citation2005, 18).Footnote32

Questioning the constitutive role of colonial legal practice in the privatization of communal lands, I challenge the neutrality of land inspection reports as ‘strategic representations of space’ in late colonial Ecuador.Footnote33 Although all maps are representations of space, my emphasis on their role as strategic evidence suggests that the judge accepted Carcelén’s map as an unproblematic departure point (a template of sorts) to design cartographically the official report of the inspection. Landscape maps embodied the court’s and the relevant parties’ own notions of productive space, ethnic space, possession, and ownership. In this case, the final report of the vista de ojos naturalized the land claims of the Spanish party by inscribing them visually in a landscape representation believed to be transparent for legal purposes. Maps and inspections’ written reports appear the sole products of meticulous investigations invested with an invisible halo of justice.

This maneuver required command of a legal capital to which the two parties in this dispute had unequal access. The cartographic evidence that only landowners enjoyed was largely predetermined, if not prefabricated, by maps that obeyed Spanish conventions of spatial representation, including the landowners’ own description of the indigenous communal space: ethnonyms, landmarks, and the naming of other ethnic landscape features. As pictorial representations of the Andean landscape, they make evident the role of the law in imagining and representing reality (Geertz Citation1973), and in advancing the privatization of the colonial communal space of indigenous peoples. In the end, the customary legal practice of the courts engendered legal evidence, out of self-interested cartographic representations, bolstering the consolidation of colonial landownership in the Andes. This section demonstrates that maps are constructs politically sustained by intra-elite alliances and endowed with the power to legally define landscape on paper while de facto intervening in territorial realities. Thus, early modern cartographic technology impeded the ability of indigenous peoples to retain their right of possession over communal and individual lands (Harley Citation2001), as such right was constantly ‘recomposed and decomposed while being recognized’ (Herzog Citation2013, 305).

The long-standing legal procedures conducted to sanction indigenous property and settle land disputes constituted the ethnic space as colonial space. This was effected visually and discursively through the legal ritualization of vista de ojos or land inspections with their surveys (mensura) and boundary demarcation along with the written and spoken narratives articulated in court. The colonial ethnic space was infused with Spanish notions and ceremonies of possession and further sanctioned with amparos de posesión, land titles, and maps. The vistas de ojos involved the displacement of multiple peoples around the land, imprinting the colonial space in the body and its relation to the land. In this case, the procedures mobilized nearly thirty people, including the Spanish landowners, government officials, Indian representatives and witnesses, and other non-Indians in the vicinity, in a concerted walkabout to the disputed lands. The vista de ojos and mensuras expressed contending understandings of productive space, possession, and ownership triggered by colonial relationships. For the Indians, the king entitled them to communal lands on his behalf, and the Virgin, as their mother earth, sanctioned their possession as only her sacred power could do. For the Spanish landowners, furnishing land titles and actively producing cartographic evidence sanctioned their ‘donations’ to the king, or ‘purchases’ of communal space.

Legal cartography and the privatization of Machachi’s communal space

In the late fifteenth century, when maps appeared to play purely illustrative and informational purposes in Castilian courts, landscape maps also became probatory and/or disproving tools in disputes over land and water rights (Vassberg Citation1996). In Spanish America, maps were connected to the land tenure transformation, with their legal use signaling the inception of the land dispossession process (Harley Citation1994). In colonial Machachi, landscape maps had been commonly used as legal evidence in the eighteenth century as appropriations of indigenous lands continued by Spanish land-grabbers connected to local authorities.

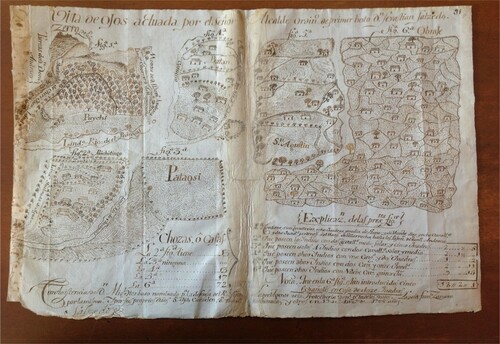

The two landscape maps this case are unusual cartographic records. Rarely do the archives hold sketches of maps such as the one shown in . Bearing no folio number, the revealing sketch appears on crude paper, uncolored, and filed back-to-back with the judge’s visual report of the vista de ojos (), suggesting the connection between the two. Carcelén’s lawyer even admittedly submitted the sketch before the vista de ojos took place. It is likely that the appointed judge, don Sebastián Salcedo, used Carcelén’s sketch as a kind of template to produce the maps in the vista de ojos’s report. He proved amenable to Carcelén’s demand that the Machachi community furnish their land titles. The two maps became legal evidence and functioned as the textual and graphic inscription of colonial Machachi’s communal space transformation. The maps projected Carcelén’s private interests onto an authorized register that sanctioned the conversion of Indian town lands into haciendas and private property more generally.Footnote34

Figure 2. Mapas planos y croquis [MP], 19. 1768. Courtesy of the Archivo Nacional del Ecuador, Quito (MP 19) (untitled and unnumbered). In 2007 all maps in the Serie Indígenas were separated from the original lawsuit files and filed in the section of Mapas, planos y croquis.

![Figure 2. Mapas planos y croquis [MP], 19. 1768. Courtesy of the Archivo Nacional del Ecuador, Quito (MP 19) (untitled and unnumbered). In 2007 all maps in the Serie Indígenas were separated from the original lawsuit files and filed in the section of Mapas, planos y croquis.](/cms/asset/f6851b0d-acac-48ba-89fb-903ba9e716d1/ccla_a_2104032_f0002_oc.jpg)

Figure 3. ‘Vista de Ojos actuada por el Señor Alcalde Ordinario de Primer Voto Don Sebastián Salcedo.’ MP 18. 19 de diciembre, 1768. Courtesy of the Archivo Nacional del Ecuador, Quito.

Scholars studying similar land disputes between Spaniards and Andeans in Machachi and elsewhere in the Ecuadorian Andes (Borchart de Moreno Citation1980; Moreno Yáñez Citation1980) have registered a pattern of land judges relying on the unilateral depositions and documents of the Spanish landowner party. Judges often performed land inspections without land surveys properly conducted by officially appointed independent surveyors.Footnote35 The monochromatic sketch Carcelén submitted bears ownership ascriptions that Salcedo readily ratified in the final report of the vista de ojos. Simultaneously, these maps reflect Carcelén’s cartographic power to define the indigenous communal space.

Through a peculiar use of place names, the sketch renders the lands of the two parties differently: toponyms served as textual designators of ownership. Thus, the lands self-attributed by Carcelén appear identified as ‘Puychicoto belonging to D. Joseph Carcelén’; ‘Potreros belonging to Carcelén;’ ‘Puychi, de Esparsa, and now belonging to Carcelén’ etc. On the other hand, the lands acknowledged to be the Indians’ are vaguely defined, of insignificant size, and the sites named ‘where the Indians lived’ are barely outlined and lacking significant detail in names, sizes, or belonging ascriptions. As opposed to the final map, intriguingly, the sketch gives the viewer a better sense of landscape continuity, whereas the different ‘figuras’ or partitions in are extricated from the actual layout of the landscape, their orientation appears rotated, and the location is altered for both Batán and Obraje. Thus, the connection of all land plots with each other and to the lands Carcelén claimed as his is rendered unknowable.Footnote36 The claims of ownership embedded in the sketch’s place names are missing in the final map, but they are actually ratified textually in the map’s legend.

The map report () shows six land plots (‘Figuras’) arranged in a kind of ‘jigsaw-puzzle’ composite map, a portion of those shown in the sketch, corresponding to the indigenous land plots of Puychitingo, Patagsi, Batán, San Agustín, and Obraje. Since these land maps are monochromatic only, it is likely, although not conclusive, that the two maps analyzed here are drafts of the final map. Since it is the only extant map or visual report of the vista de ojos (), I am using it as such. There is no information on the map artist’s identity, but it is possible that the judge commissioned the map from a local artist, perhaps an indigenous person on account of their local knowledge of the environs.

The map in the vista de ojos report () is rich in topographical detail and shows a mix of ethnonyms bearing names in the local Panzaleo language (Puichi, Puichitingo, Patagsi), and in Spanish (‘Obraje,’ ‘Batán,’ ‘San Agustín’). The term ‘ethnonyms’ here indicates the cartographic intervention of mapmakers on behalf of the Spanish landowner and the judge, ascribing ethnic identity to peoples and landscape features that linked ethnicity to colonial space (Erbig and Latini Citation2019). Likewise, the naming of landscape features in this graphic text reveal a hispanized tradition of land inscription through linderos (boundaries), land usage in agropastoral activity, and the buildings situated in each ‘paraje’ (site) all signaled with Spanish labels. Natural features (cerros or hills) and water bodies somewhat delineate linderos, demarcating productive spaces. Whereas the names of the Spanish parties involved in the lawsuit function as ownership ascriptions of the natural resources valuable for forestry or agrarian activity (the ‘montes of D. Domingo Andraca’), indigenous toponyms mostly appear to designate linderos (‘lindero Rio de Chisinchi’) and some land plots.

At the bottom right of the map (), two conspicuously distinctive legends reveal important clues about the discursive nature of legal cartography, and the judge’s ratification of Carcelén’s claims. The first one renders the size of each ‘figura’ in unit scales ranging from ‘caballerías,’ to ‘solares,’ and to ‘cuadras,’ while the map also registers the Spanish encroachment upon the Machachi communal lands, but without specifying the individual names of the invaders.Footnote37 Although the legend registers the presence of the Spanish party, the judge and the Indians’ representatives, as though giving legitimacy to the final map, in fact, the Indians neither had an option to furnish or produce a map of their own, nor were they there at the crafting of the map ‘for the defense of their own rights’ as the legend implies.

The second legend spells out the number and size of the houses in each sitio, ‘where the Indians lived.’Footnote38 The map legend is a statement anticipating the case’s verdict and suggesting the input of Carcelén’s map as evidence. In Figura 1a the measure of Puychi reads as ‘Seven Caballerías and eight cuadras of flat lands and eighteen caballerías and two cuadras of mountain lands that belong to Carcelén de Villarocha up to the hay fields of Domingo Andraca,’ which ratifies Carcelén’s claims.Footnote39 This is most striking since the lower part of Puychi, stated in the legend as belonging to Carcelén, included the lands which the Cacica and the Indians claimed as their communal lands, and because the case was still pending in court at the time the map was produced. In court, Carcelén claimed to have purchased these lands from the majordomo, Agustín Suárez de Figueroa, allegedly in an auction of lands that belonged to the cofradía.Footnote40

Carcelén’s ultimate legal argument thus appears constructed and inscribed cartographically. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the final map Salcedo crafted as the report of the vista de ojos sanctioned the ownership self-ascriptions of Carcelén as factual ‘findings’ of the land inspection and rendered invisible the community lands under dispute. This is striking since a portion of Puychi even appeared signaled in Carcelén’s sketch preceding the inspection. The inspection report map’s legend reflects Carcelén’s prior attempt to tip the balance of the inspection and the litigation further in his favor. Along with his sketch, he had submitted a self-authorized text or ‘memoria’ offering unsolicited estimates of what the Indians owned, with ethnonyms and sizes roughly assessed.Footnote41 Carcelén’s ‘memoria,’ however, only acknowledged as Indian lands areas unrelated to the sitios under dispute. He argued repeatedly that the Indians possessed extensive property, more than the legally stipulated one-league of lands, and swiftly dismissed their main claims over Puychicoto, which he asserted in the ‘memoria’ and marked in the map as his own. Other contemporary lawsuits from elsewhere in the Audiencia de Quito reveal similar arguments by Spanish landowners. Apropos of them, Herzog argues that, in the end, what Spaniards implied was that Indians should not accumulate or rent the land not needed, and that the Indians ‘were to be kept at the subsistence level’ (Citation2013, 317).

For their part, the judges arbitrated these land conflicts in ways suggesting that impartial decisions were not to be expected in the contest for land control, particularly when disputes involved the interests of Indian communities and Spaniards. The purpose of the vistas de ojos was for the judge to verify with his own eyes the location, size, and limits of the lands in question, to make necessary adjustments to achieve justice, according to Spanish law. In the Machachi Indians’ case, however, the place naming choice of Carcelén’s monochromatic sketch and the judge’s heeding both its cartographic argument and the self-authorized narrative in Carcelén’s ‘memoria’ preempted any challenge to his claims. The reality is that the Machachi plaintiffs were not asked to submit landscape maps of their own prior to the vista de ojos. Instead, by order of the judge Salcedo, the escribano don Francisco Javier Bustamante had summoned Cacique Zamora and the Indians’ Protector Bolaños prior to the vista de ojos, asking that those who claimed Puychi should:

come forward with their papers or sale documents, be they about technical, simple, or any other type of sales pertinent to the lands of this litigation and those [papers] pertaining to the sales of community lands that either caciques or Indians had sold in the past, to proceed to the vista de ojos, the land identification, and an exhaustive land survey.Footnote42 (my emphasis)

The emphasis of the requirement was clearly on the need for the Indians to furnish ‘instrumentos de ventas’ or land sales documents, with no mention of maps to counter Carcelén’s. In fact, at Carcelén’s behest, the escribano directly summoned Cacica doña Basilia Pungutagsig to submit the repartimiento titles for the communal lands of Machachi and to furnish the padroncillo or community registry, listing all the Indian subjects of the parcialidad that she led.Footnote43

Like many pueblo communities of the Andes, the Machachi Indians had no instrumentos that certified ownership or a sanctioned entitlement to the collective usufruct of the disputed lands. It is worth noting, though, that by 1768 such documents would have been about 200 years old, after the foundation of the reducciones that gave birth to the town of Machachi. Additionally, not all the foundations of reducciones were sanctioned with titles to the communal lands assigned on behalf of the king at that time. Many reducciones were created during visitas or inspections conducted orally by city officials, who left the town promptly after the ‘foundation’ had taken place. Some other times inspectors recorded the land assignments in ‘libros de repartos’ or registries books which only rarely appeared in the archives (Amado Citation1998).

And it was perhaps in this gray area of ‘paperless’ or ‘untitled’ property that Spaniards found the legal vacuum that facilitated these land ‘purchases’ and spurious titles. Carcelén argued that he had bought the land of Puychicoto from Suárez de Figueroa, an Indian cofradía majordomo who had no right over the disputed lands either, but likely knew that the Indians had no original repartimiento titles. Of all the documents required, the Indians could only furnish the padroncillos bearing the names and total numbers of tributaries of the Machachi parcialidad.Footnote44

From the cognitive perspective, this fragmentary landscape cartography conveys a flawless indigenous environment of standardized plots and economic usage (). The sites’ graphic rendition by Judge Salcedo assumes clearly demarcated boundaries, and, with a striking uniformity, projects a landscape of orderly, homogeneous land plots inhabited and in production. The graphic discourse almost presumes equality in land distribution since the absence of both spatial continuity among sites and integration of the sites into a whole renders size scales deceiving. The cartographic agenda of the report is thus exposed. Visually, Carcelén’s lands and those in dispute appear relatively small (Puychicoto), whereas the indigenous sites are made to appear significantly larger. Even from the judge’s reported sizes in the legend of , Carcelén’s individual land claims were disproportionally larger than the collectively used community’s sites. And this is the argument Carcelén’s repeated in his favor on and on: that the ‘Indians’ had too much land.

Cacique Zamora disputed vehemently both Carcelén’s cartographic misrepresentation and his self-attributed legal authority to determine the extension of the indigenous lands in his ‘memoria,’ ultimately arguing that the lands of the Indians were insufficient and that they needed more. He challenged the alleged ‘facts’ about the Indians’ lands size, which sought to undermine the community’s claims for Puychicoto and the other lands. Although not immediately, the cacique was able to obtain an order for a new land inspection to verify Carcelén’s roughly estimated figures of the Indian lands’ sizes.Footnote45 Zamora also protested Carcelén’s pretentious statement of what the Indians owned. It overlooked the fact that some of the sitios under dispute were very small plots purchased by indios forasteros or migrant Indians, and who had escrituras (deeds), although they were not summoned to the vista de ojos.

On 23 December 1768, the escribano don Francisco Javier Bustamante, designated to verify the sitios in question, reported: ‘I verified that the parcialidad Indians that resettled in the said pueblo were occupying their own lands, which do not include those belonging to the Pungutagsig’s parcialidad and cacicazgo.’Footnote46 In other words, Bustamante acknowledged that ‘Batán’ belonged to the indios forasteros, thus undermining Carcelén’s argument that the Indians possessed many large community lands. Zamora also provided the alcalde ordinario with the names of the indios living in those sitios and asked that the escribano also verify the actual size of those lands, because they were smaller than what Carcelén claimed in his ‘memoria.’ Furthermore, Zamora stated, those were overcrowded lands with several Indians working and living in the same quarters. Zamora further requested that this verification be attached to the file, and that the escribano specifically state that the Indians had purchased ‘Batán’ themselves ‘with much difficulty.’

Cacique Francisco Zamora, now referred to in the records as ‘defensor de los indios,’ or the Indians’ defender, insisted on having verifications of the actual distance between the disputed lands and the town itself. He ultimately wanted to demonstrate that Puychicoto and the other sitios of the community were actually within the stipulated one-league radius that circumscribed the domains of the pueblo communal lands, where no Spaniard was supposed to own property.Footnote47 Bustamante was able to verify that the disputed lands were part of the community landholdings: ‘As far as the distance of these lands from the town, it seems to me that the farthest ones are no more than a quarter of a league away from it, […] and, in any case, the tolling of the bells can be heard in all the sitios or parajes.’Footnote48 Such an assessment should have been sufficient to render Carcelén’s claims false. Nevertheless, Bustamante cleverly concluded that ‘the Indians have lands in two different places, and they could make up for the small size of the land plots by joining the two properties.’ Trying to prevent an assessment of communal lands existing in excess, the Indians moved to explain that ‘one after another, they had bought those lands and they would demonstrate their ownership with the titles they had.’Footnote49

As mutilation and document subtraction were not uncommon in the colonial archive, it is unsurprising that the last pages of the dossier are missing, and we can only ponder about the outcomes of the dispute. Most likely, the adjudication moved in favor of Carcelén’s interest, as he argued all along that the Indians had lands in excess, and that ‘Puychicoto,’ in particular, was sold to him in a legal auction which he designated as a ‘donation’ to the Bourbon king.Footnote50 In neighboring Andean areas, many late colonial land disputes involving communal lands were adjudicated in favor of hacendados and non-Indian parties.Footnote51 This outcome would have been consistent with the juridical practice of the time in the Andes. Land judges endorsed the auctioning of existing community lands deemed to be in ‘excess,’ which represented both additional revenue to the king (Spalding Citation1984, 205; Jacobsen Citation1993, 88) and an expeditious means to expand the neighboring haciendas. In the late colonial Peruvian Andes, for example, verdicts reflected the enlightened administrators’ upholding of production efficiency and individual property over corporate groups’ rights, particularly the Andean communities’. These officials also believed that not only should all community landholders enjoy the same amount of land each, but that they were to possess simply enough land to cover the family needs and only as much as they could utilize with just the family’s work (Jacobsen Citation1993, 88).Footnote52

It is possible that the court echoed the Crown’s interest in supporting the communities’ reproduction needed to secure their increasing labor and fiscal obligations. However, it is unlikely that the community’s amparos de posesión the Machachi Indians obtained in 1698 and 1767 would still hold validity in 1768, since the trend of the time was for the courts to give less credit to a community’s claims of past possession of lands (Jacobsen Citation1993, 88).Footnote53A third possible yet unlikely outcome, the judge may have favored the Machachi Indians with a new amparo de posesión, a likely ineffective verdict, given the past trend of non-enforced amparos like those from 1698 and 1767.

Conclusion

Beyond a religious commonality, the tolling of the town church’s bells would have given the 1768 Machachi Indians a sense of community and legal identity as Indian pueblo residents bound by the common possession of their lands. For sure, that sense of belonging made them confident in mobilizing both the image and the legitimating power of Andean Catholic symbols to assert their right to community landholdings endangered by Spanish claims. The Machachi community chose to stage their own understanding of possession through a more Andeanized vista de ojos. The Virgin ‘mother of the Indians’ became an alternative legitimating force made to function as the supreme judge: a motherly and earthly power superior to the juez nombrado, his inspection reports, and mensuras.

Spaniards also walked about with the judge and witnessed the vista de ojos and mensuras, just like the Andeans who partook in ceremonies of possession of their own. These legal rituals empowered Spanish claims to Andean lands, especially, because of the authoritative force of their land maps, land titles, and allies’ protection of their interests, which Carcelén buttressed by auctioning ‘donations’ to the royal treasury. Thus, Spaniards could claim full possession and ownership of increasing portions of the remaining pueblo lands in the Andes. Since the late sixteenth century, imperial Spain had used the spatial reorganization of Indian space in reducciones to convert part of the original Andean lands into Indian ‘pueblo lands,’ on behalf of the king, the ultimate colonial landowner of the realm. Thus, the law and its verdicts turned Indians’ possession of their communal lands into a colonial precarious and temporary possession, limited to individual usufruct of collective lands rather than full possession linked to ownership (Herzog Citation2013, 312, 314). More specifically, Spanish vistas de ojos and mensuras instituted a mediation between Indians and their land, imprinting such colonial character on the communal space of the pueblos de indios through walkabouts, boundary demarcations, and, arguably, oral discussions that went unrecorded.

The Machachi Indians attempted to demonstrate possession in ways influenced by Spanish law and their own local spatial relationships. They did it in their own cultural idiom by performing posesión through rituals and symbolic images that had both Christian and Andean meaning. Such assertions of possession thus recognized the interfaces between Spanish and Andeans’ arguments in court as well as their shared spatial practices of boundary-making. In Machachi, both parties engaged in the manipulation of images and symbols, cartographic discussion and mapping examination to either assert or debunk each other’s right of possession.Footnote54 Andeans and Spaniards participated in the vista de ojos and mensuras according to the Spanish practice, but Andeans expressed their contradicción or objections to the judge’s determinations with images, movements, and utterances of their own accord.

In land conflicts between communities elsewhere in the Andes, pueblo communities occasionally contested the encroachers’ land maps with maps of their own. That was not the case in 1768 Machachi, though. Nevertheless, the Cacique Gobernador don Francisco Zamora relentlessly disputed Carcelén’s legal moves with his own cartographic discussions, insisting on land measures and location verifications, and unmasking inaccurately reported land-plot sizes. Cacique Zamora performed as legal translator for the Indians, interpreting the law and writing memoriales on their behalf. He also performed as a cultural translator for the court, explaining the Andean motives and perceptions behind their actions.Footnote55 His mediation aimed at explaining their otherwise perceived transgressions in a legal language that supported the possession of both the lands of the parcialidad and the individual plots of the Indian forasteros who, by 1768, transitioned into community members.Footnote56

As a native witness, legal translator and advisor, and Cacique Gobernador, Zamora’s ‘oral performance’ in the trial carried weight. He crafted a persuasive cartographic rhetoric challenging the facts and interpretation of the boundaries graphically argued in Carcelén’s landscape map.Footnote57 While local knowledge and culture suffused the community assertion of boundaries and their interpretation in court by the cacique, the Spanish landowner deployed a well-endowed legal capital that ignored such claims altogether. Maps thus acquired the status of legal evidence thanks to powerful networks that not only secured Spanish interests but contributed to the long-term takeover of the last remaining communal lands in the Andes more generally. This is, in essence, the story of a localized ethnohistory of law and culture unveiling Andeans’ creative disruptions, recreations, and group empowerment.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to Yanna Yannakakis, Rachel Corr, Kris Lane, Santiago Muñoz, and Alexander Hidalgo for the generous feedback on earlier versions of this article and to the anonymous readers of CLAR for the valuable suggestions. Special thanks to the Fulbright Scholar Program and the John Carter Brown Library for funding this research. I am also grateful for the generous services of the staff of the Archivo Nacional del Ecuador.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alcira Dueñas

Alcira Dueñas has taught Latin American history extensively in Latin America and the United States where she is an Associate Professor at Ohio State University, Newark. Her research interests on indigenous intellectual history crystalized in her award-winning Indians and Mestizos in the ‘Lettered City’: reshaping justice, social hierarchy and political culture in colonial Peru (2010). The more diffused expression of the indigenous lettered world in the Andes took place in the pueblos de indios’ cabildos, whose legal culture constitute the core of Alcira’s second book, currently in progress. Among others, she has received fellowships from Fulbright, the NEH, the Max-Planck Institute, and the John Carter Brown Library. She has published peer-reviewed articles in Ethnohistory, The Americas, CLAR, Histórica among others.

Notes

1 4 Cuaderno. Quito, 10 de diciembre, 1768. Serie Indígenas. Caja 88, Expediente 19, f. 1 Archivo Nacional del Ecuador (ANEQ) (hereafter, 4 Cuaderno). In colonial documents, llajta often designated ‘pueblo de naturales.’ More rigorously, the llajta was an Andean settlement or llajtakuna. As a group, the llajtakuna shared a common ancestry and hereditary rights to lands and labor, among other things. They collectively recognized an elite member of the llajta as their native lord (Salomon Citation2007, 45).

2 For discussions of ‘legal pluralism’ see Merry Citation1988. And for this concept in Spanish imperial law, see Benton and Ross Citation2013.

3 Among other seminal studies for colonial Ecuador, see Borchart de Moreno Citation1998; Liehr Citation1976; Moreno Yañez Citation1980. For colonial Peru, see Guevara-Gil Citation1993; Larson Citation1988; Ramírez Citation1986; Spalding Citation1984.

4 Segundo Moreno Yañez (Citation1980) reached the same conclusions for Saquisilí (Latacunga), in the Quito province, from the late seventeenth through the early eighteenth centuries.

5 Andean translations of law thus aligned with Benton’s (Citation2012, 36) conclusion that indigenous strategies shaped ‘the formation and circulation of norms for negotiating and recognizing claims’ of possession.

6 The place names (‘Obraje’ [textile workshop] and ‘Batán’ [fulling mill], and ) suggest the presence of textile workshops in the town lands.

7 For the rebellion, see McFarlane Citation1996; Minchom Citation1994.

8 For the role of composiciones in the formation of haciendas in Saquisilí, see Moreno Yáñez Citation1980.

9 Mountain livestock and logging tied to the Quito market were, arguably, valued commercial activities by Spanish landowners in Machachi. By 1581, lime extraction or caleras, livestock grazing in estancias and barley and potato farming constituted the bulk of the local economy (Jiménez de la Espada [Citation1897], Apéndice No.1, Caja V).

10 Discussions of possession have focused on legal mediation and translation of rights (Herzog Citation2013); the symbolic means of possession during the conquest (Seed Citation1995). Bastias (Citation2020) discusses the early modern precedence of possession over later notions of ownership. For case studies in Andean Peru, see Guevara-Gil Citation1993; Lopera Mesa Citation2020. For New Spain, see Owensby Citation2008. See Hostnig, Palomino, and Decoster Citation2007 for a rich compilation of land dispossession records from Andean Peru.

11 Attaining the writ amparo de posesión, the Indians’ most frequent motive to use the Spanish courts, secured protection of their lands against imminent encroachments from Spaniards, other Indians, and non-Indians alike. The amparo would sanction the ocupación de hecho or having conducted productive activities, typically palpable signs in the landscape (planted fields, built fences, houses, and corrals).

12 Cacica doña Basilia reported that, other than Puychicoto, six indios forasteros (newcomers), whom she still considered community members, owned lands in the jurisdiction of the pueblo. Throughout the proceedings, Carcelén appears indistinctively designated as Carcelén de Villarocha and ‘Treasurer de la Santa Cruzada.’ The spelling for native sites is standardized based on first usage.

13 ‘Querella por despojo.’ Serie Indígenas, 26 de mayo de1698. Caja 23, Expediente 9, fs. 1–19. ANEQ; ‘Litigio por las tierras.’ Serie Indígenas, 10 de noviembre de 1729, Caja 42, Expediente 27, fs. 1–22. ANEQ.

14 ‘Litigio por las tierras denominadas Cunchicoto, Nagtimaq, y las del cerro Puysuchua.’ Serie Indígenas, 13 de noviembre, 1767. Caja 87, Expediente 14. ANEQ.

15 4 cuaderno, f. 27.

16 4 cuaderno, f. 26.

17 4 cuaderno, f. 6.

18 4 cuaderno, fs. 1, 14–15.

19 Earlier in 1692, a total of 175 Cs of Indian land had been transferred to Spanish hands through sales, inheritance, donations, and dowries. The Quito Alcalde Ordinario may have been appointed as judge given Machachi’s falling under the jurisdiction of Quito.

20 4 cuaderno, f. 15. Similar community challenges to judicial actions on the land were also known in early modern Spain. Challenges to boundary making are discussed in Herzog Citation2015, chapter 3.

21 ‘que todas las razones que considerasen en el asunto presente me dijesen en nuestro idioma de indios.’ 4 cuaderno, f. 15 (my emphasis).

22 4 cuaderno, f. 15.

23 ‘Por eso es que el Rey su capitán los protege con el alcalde ordinario.’ 4 cuaderno, fs. 1, 14–15.

24 4 cuaderno, f. 14.

25 ‘y llevaron a Nuestra Señora en procesión a dichos sitios e hicieron demostración que ella la tomaba [la tierra] en posesión, a nombre de los indios, como madre que era de ellos […] la verdadera poseedora, y nuestra señora, la madre de los indios.’ 4 cuaderno, fs. 1, 14–15.

26 Likewise, Guaman Poma de Ayala justified Andeans’ right to possession of their American territory on the mandate of god as opposed to the king’s (Adorno Citation2012, 75–76; Adorno Citation2007).

27 As was the case in Machachi, Cuadriello (Citation2010, 69–70, 72, 95) argues that in New Spain religious images were invested with power and they were not necessarily deployed for purposes of ‘domination, coercion, or confrontation.’ In both Machachi and Tlaxcala, the Indians construed the Virgin as their mother and true protector, their legal advocate or abogada, the true guardian of the land.

28 ‘para que le constase a vuesa merced en el propio idioma de los indios que de otro modo no pueden explicar la contradicción.’ 4 cuaderno, fs. 1, 14–15 (my emphasis). Zamora insisted that the Indians’ demostración (procession) was not intended as resistance or disobedience to the judge but rather, ‘by way of contradiction’ [‘por via de contradicción’], the way in which the Indians expressed the law in their own idiom. As in late colonial Tlaxcala, the Virgin’s name may have constituted ‘the very personification of the jurisdiction or the territory benefited by her […] thus, acquiring a political and social power of representation capable of convoking the corporations and the plain people’ (Cuadriello Citation2010, 73).

29 Thus, place name practices arguably underlay not only the Spanish-style identification and demarcation of boundaries but the very Andean walkabouts in late colonial times.

30 Instances of perambulatory practices existed among pre-colonial Inca. Abercrombrie (Citation1998, 9–10) traced their origin to Castile prior to the onset of an archival writing culture, to fix them in the ‘unwritten archive of social memory,’ at the intersection of writing, landscape, and ritual. For New Spain, see Yannakakis Citation2008a, 164; McDonough Citation2017.

31 Herzog (Citation2021) refers to these local variations as ‘a “vernacularisation,” concretisation, and “localisation” of the general law.’ Andeans cocreated the Spanish forms to represent possession in spite of the fact that, ‘native rights became Spanish, and the memory of a past was replaced by the (relative) certainty of a present’ (Herzog Citation2021, 47). For the 'vernacularization' or colonial justice by Oaxacan Indian judges and their innovative use of translation, see Yannakakis and Schrader-Kniffki Citation2016, 524, 542–43.

32 Spanish law penalized composiciones and other land transfers that demonstrably caused harm to indigenous land interests (‘Recopilación de Leyes’ Libro IV, Título XII, Leyes XV–XXI). Land maps submitted by Spanish defendants in pueblo lawsuits, thus, tended to deem their own aspirations as innocuous for Indians.

33 See Hidalgo Citation2012, 117. More broadly, Harley (Citation2001, 86) debunks the neutrality and inconsequential nature of maps in early modern Europe, emphasizing their ‘socially constructed perspectives.’

34 Andeanists from the Northern Andes have documented further instances of these landowners’ legal strategies, particularly notable after the wars of extermination of the Chimila Indians, within the larger context of colonial frontier control in late colonial New Granada (Muñoz Citation2007).

35 A revealing case in point relates to the Quito Real Audiencia Fiscal don Antonio de Ron’s, inspection (visita) of the Machachi Valley in 1692. De Ron managed to remove about 1100 Cs from the common land domains of Machachi, which eventually ‘merged’ into Spanish haciendas. This transfer resulted from dubious composiciones that ignored existing indigenous lands in the vicinity. Land surveys and other verification forms of pre-existing possession were either not conducted properly or did not happen at all (Moreno Citation1980, 9).

36 MP 18, and MP 18, f. 31. ANEQ.

37 In late colonial Ecuador, 1 caballería = 47 Hectares (Hs), 1 solar = 0.44 Hs, and 1 cuadra = 0.7 Hs. (Real Academia de la Lengua Española Citation1726). (MP. 18).

38 ‘2a. figura-13 casas; 3a. figura. -0 casas; 4a. figura-13 casas; 5a. figura-17 casas; 6a. figura-22 casas.’ MP. 18. 4 cuaderno, f. 31. Hereafter, Caballerías [C], Cuadras [Q], Solares [S].

39 MP. 18 (my emphasis). Carcelén reported the sites’ sizes thus: : ‘7C 8Q of flat terrain and 18C 2Q of hilly land that belong to Carcelén de Villarocha’; : ‘Indian lands for 2C and 1.5S’ (this ‘sitio’ is interchangeably named ‘Puychi’ and ‘Puychicoto’); , ‘lands possessed by four Indians for 2C and 1.5S’; Figure 4. ‘Indian lands for 1C and 2Q.’ Figure 5, ‘Indian lands for 2C and 11Q’; and Figure 6, ‘Indian lands for 9C and 15Q.’

40 4 cuaderno, f. 25. If true, how the cofradía majordomo got a hold of Machachi land titles is not explained in the proceedings. Suárez de Figueroa accompanied the officials that were trying to survey the land when the Machachi Indians disrupted the procedure, and before they paraded with Nuestra Señora, the Virgin ‘mother of the Indians.’ But he was not one of the ‘white men’ present. It is possible that Suárez de Figueroa unlawfully and surreptitiously sold the lands to Carcelén. Self-interest often challenged communal wellbeing and loyalties; cross-racial collaborations driven by personal interests within communities were not uncommon in the late colonial Andes (Stavig Citation2000). Also, as the majordomo of an Indian cofradía, one presumes that Suárez de Figueroa was an Indian. His ethnicity, however, is not indicated in the documentation with the usual ‘indio’ identifier. Given the history of collaboration between some Andean authorities and Spaniards to redirect lands and labor to the Spanish sphere, Figueroa’s behavior would have been unsurprising. For a historical reconstruction of Ecuadorian Andean caciques’ collaborating in such transfers, see Vieira Powers Citation1995; see also Caja 123, Expediente .23. Cotacallao, 1788 ANEQ; ‘Reclamación del común.’ Caja 130, Expediente 9, Loja, 1790. ANEQ. Other cases against cofradías majordomos selling communal lands illicitly can be seen in ‘Litigio de tierras.’ Cuenca, 1792; Caja 132, Expediente 25. ANEQ; Caja 112, Expediente 16 Guayaquil, 1784. ANEQ. These instances reveal that indigenous communities were not homogeneous, and that personal interest contributed to their territorial instability.

41 The ‘memoria’ lists all the ‘lands, hills, and hay fields possessed within the limits and jurisdiction of the town of Machache by the Indians reduced in parcialidades’ [‘tierras, montes y pajonales que poseen los indios que se hallan reducidos en las parcialidades en los términos y jurisdicción de este pueblo de Machache’].

42 4 cuaderno, f. 10v (my emphasis): ‘para que comparezcan con sus papeles o instrumentos de ventas, técnicas simples y otros cualesquiera pertenecientes a las tierras de este litigio, y también [comparezcan con los instrumentos] de las tierras de comunidad que hubiesen vendido los caciques e indios y proceder a la vista de ojos, reconocimiento y mensura prolija de tierras.’ Land sales designated as ‘técnicas’ may have included those that yielded notarized titles; ‘simples’ designated those sales that went recorded more informally outside notarial control, such as bills of sales. (I thank the CLAR anonymous reader who suggested these interpretations of the terms.) See registered sales for the years 1674, 1708, 1733, 1739, and 1768, in 4 cuaderno, fs. 95, 100–1, 104.

43 In the land inspection report, the escribano signing as ‘Bustamante’ states that the judge proceeded to the ‘mensura prolija’ or thorough survey of the lands, hills and sitios, rendering the size of some unidentified ‘montes’ or hills as ‘2C, 5Qs, and 0.5S’ (4 cuaderno, f. 23v). Bustamante rendered the total owned by the Indians as ‘18C, 2S, 1Qs.’ Separately, he lists ‘Carcelén’s lands,’ thus: ‘Puychi from the Carcelén de Villarocha, which have hills in the amount of 18C, 2Qs. The plains at the piedmont of the said Puychi have 7C y 8Qs. Total lands that Carcelén possesses: 25C 2S y 8Qs.’ (The map reports 10Qs instead of 8.) The total land measured amounted to 43Cs and 10Qs (the actual sum, however, is 41C, 41 Qs y 4Ss). 4 cuaderno, f. 23v (my emphasis).

44 4 cuaderno, fs. 19v, 21. In 1768, the Machachi submitted a padroncillo from the community’s tribute registries or ‘cuadernos de cobranzas,’ registering 108 tributaries, and another one from 13 December 1678, showing 64 tributaries.

45 4 cuaderno, f. 20. ‘Jeronimo Jácome, indio, adquirió caballería y media y tres cuadras de tierras en este sitio de Puichitungo.’ Furthermore, and upon an encroaching attempt by a Spaniard, the Real Audiencia had issued an ‘amparo in his favor, as an individual, because the land was not communal but individually owned by Jeronimo Jacome’ (4 cuaderno, f. 14r/v).

46 4 cuaderno, fs. 17v, 19.

47 Bustamante verified the size of five out of the seven sitios Zamora requested for verification and reported that none of them even exceeded the insignificant size of two or three cuadras. Bustamante remarked that some of the small land plots had houses built on them, but others did not, undoubtedly hinting at houses as signs of effective possession.

48 4 cuaderno, f. 20r/v.

49 4 cuaderno, fs. 20v–21.

50 Puychicoto may have been misconstrued as vacant land and auctioned out. Cultural differences in agricultural practices explain in part the contention over community landholdings. Whereas Andean ayllus practiced land fallowing to protect the fertility of the soil, Spaniards either misunderstood fallowing or purposely misconstrued it as lands unused or held in excess. Andeans usually kept lands in production for 3–4 years and subsequently in fallowing for 4–8 years (Klein Citation1993, 60–61).

51 The list of these lawsuits is long. An illustrative sample includes: ‘Pleito por ocho cuadras.’ Serie Indígenas, Caja 118, E.16. Alangasí, 1786. ANEQ; ‘Representación del Fiscal Protector.’ 1791, Ibarra. Serie Indígenas, Caja 131, Expediente 1, ANEQ; ‘Causa,’ Cuenca, 1791. Serie Indígenas, Caja 132, E.16. ANEQ.

52 Caciques denounced occasionally the scarcity of ‘tierras de repartimiento’ in their towns. ‘Pilaguin.’ Serie Indígenas, Caja123, Expediente 12, 1788. ANEQ.

53 According to Spalding (Citation1984, 206), in late colonial Peru, those holding communal lands lost their right to seek confirmation of their possession when population size did not match that of the previous possession, in which case the land would be redistributed reflecting the population trend of the time.

54 See Graubart’s (Citation2017, 63–64) argument of the ‘entanglement’ and interacting nature of Spanish and Andean ‘heterogeneous’ legal practices in Lima’s property relations. I focus on possession rather than property, however, because both the colonial law and the documentation emphasize possession as the basis for titled property.

55 For the role of indigenous intermediaries as legal and cultural translators in the Andes and Mesoamerica, see Dueñas Citation2015; Yannakakis Citation2008b.

56 The Cacica stated that ‘these Indians have become naturalized in this town and they remained on our hill because of the friendship and kinship ties they have among the Indians’ [‘estos indios están connaturalizados en este pueblo y se mantenían en nuestro monte por la amistad y parentesco que tienen entre los indios’]. Therefore, she asked the audiencia to ‘command that each forastero Indian receive three cuadras of land in addition to the plot that each Indian must have inside the pueblo as is commanded by Our Lord the King’ [‘Mandando que a cada indio forastero se le dé tres cuadras de tierras fuera del solar que debe tener dentro del pueblo como lo manda el Rey Nuestro Señor’]. 4 cuaderno, f. 6. Forasteros in Bolivia joined the ayllu through individual plot assignments and accessed communal lands through services performed to the community or to individual originario households to whom forasteros would become tied by ritual kinship and gift giving. These bonds were fragile, however, and forastero land rights were vulnerable in times of crisis (Klein Citation1993, 61).

57 See Yannakakis’s notion of ‘oral performance,’ by native witnesses in colonial Oaxaca land claims (Citation2008a, 165).

Bibliography

- Abercrombrie, Thomas. 1998. Pathways of memory and power: ethnography and history among Andean people. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Adorno, Rolena. 2007. The polemics of possession in Spanish American narrative. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Adorno, Rolena.. 2012. Court and chronicle: a native Andean’s engagement with Spanish colonial law. In Native claims: indigenous law against empire, 1500–1920, edited by Saliha Belmessous. Oxford Scholarship Online DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794850.003.0003.

- Amado González, Donato. 1998. Reparto de tierras indígenas y la primera visita y composición general, 1591–1595. Histórica 22 (2): 197–207.

- Andrien, Kenneth J. 1990. Economic crisis, taxes and the Quito Insurrection of 1765. Past & Present 129 (Nov.): 104–31.

- Bastias Saavedra, Manuel. 2020. The normativity of possession. Rethinking land relations in early-modern Spanish America, ca. 1500–1800. Colonial Latin American Review 29 (2): 223–38.

- Benton, Lauren. 2012. Possessing empire. Iberian claims and interpolity law. In Native claims: indigenous law against empire, 1500–1920, edited by Saliha Belmessous. Oxford Scholarship Online DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794850.001.0001.

- Benton, Lauren, and Richard J. Ross, eds. 2013. Legal pluralism and empires, 1500–1850. New York: New York University Press.

- Beyersdorff, Margaret. 2007. Covering the earth. Mapping the walkabout in the Andean pueblos de indios. Latin American Research Review 43 (2): 129–60.

- Borchart de Moreno, Christiana. 1980. La transferencia de la propiedad agraria indígena en el corregimiento de Quito hasta finales del siglo XVII. Cahiers du Monde Hispanique et Luso-brésilien 34: 5–19.

- Borchart de Moreno, Christiana.. 1998. La Audiencia de Quito: aspectos económicos y sociales (siglos XVI–XVIII). Quito: Ediciones del Banco Central del Ecuador; Abya Yala.

- Borchart de Moreno, Christiana.. 2013. Victorina Loza. In The human tradition in colonial Latin America, edited by Kenneth J. Andrien. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/lib/ohiolink/detail.action?docID=1168091.

- Caillavet, Chantai. 2000. Etnias del norte: etnohistoria e historia de Ecuador. Lima: Institut Français d’Études Andines; Quito: Abya Yala, Casa de Velázquez.

- Cuadriello, Jaime. 2010. La Virgen como territorio: los títulos primordiales de Santa María Nueva España. Colonial Latin American Review 19 (1): 69–113.

- Dueñas, Alcira. 2015. The Lima Indian letrados: remaking the 'República de Indios' in the Bourbon Andes. In Indigenous liminalities: Andean actors and translators of colonial culture, 55–75. Special issue of The Americas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dym, Jordana, and Karl Offen. 2012. Maps and the teaching of Latin American history. Hispanic American Historical Review 92 (2): 213–44. doi: https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.1215/00182168-1545674.

- Endfield, Georgina H. 2001. Pinturas, land and lawsuits: maps in colonial Mexican legal documents. Imago Mundi 53: 7–27.

- Erbig, Jeffrey A., Jr., and Sergio Latini. 2019. Across archival limits: colonial records, changing ethnonyms, and geographies of knowledge. Ethnohistory 66 (2): 249–73. doi 10.1215/00141801-7298765.2019.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Graubart, Karen. 2017. Shifting landscapes. Heterogeneous conceptions of land use and tenure in the Lima valley. Colonial Latin American Review. 26 (1): 62–84. http://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/10609164.2017.1287328.

- Guevara-Gil, Jorge Armando. 1993. Propiedad agraria y derecho colonial: los documentos de la hacienda Santotis, Cuzco (1543–1822). Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica, Fondo Editorial.

- Harley, John Brian. 1994. Maps, knowledge and power. In The iconography of landscape, edited by Denis Cosgrove and Stephen J. Daniels, 277–313. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harley, John Brian.. 2001. The new nature of maps. Essays in the history of cartography. Edited by Paul Laxton. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Herzog, Tamar. 2013. Colonial law and ‘native customs’: indigenous land rights in colonial Spanish America. The Americas 69 (3): 303–21.

- Herzog, Tamar.. 2015. Frontiers of possession. Spain and Portugal in Europe and the Americas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Herzog, Tamar.. 2021. Immemorial (and native) customs in early modernity: Europe and the Americas. Comparative Legal History 9 (1): 3–55. doi:10.1080/2049677X.2021.1908930.

- Hidalgo, Alexander. 2012. A true and faithful copy: reproducing Indian maps in the seventeenth-century Valley of Oaxaca. Journal of Latin American Geography 11: 117–44.

- Hostnig, Rainer, Ciro Palomino Dongo, and Jean-Jacques Decoster. 2007. Proceso de composición y titulación de tierras en Apurímac-Perú, siglos XVI–XX. Cusco: Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas y Asesoramiento: Asociación Kuraka: Instituto de Estudios Históricos sobre América Latina, Universidad de Viena.

- Jacobsen, Nils. 1993. Mirages of transition: the Peruvian Altiplano, 1780-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Jacob, Christian. 1996. Toward a cultural history of cartography. Imago Mundi 48: 191–98.

- Jiménez de la Espada, Marcos. [1897]. Relaciones geográficas de las Indias (Perú). Tomo 3. Madrid: Tipografía de los hijos de M. G. Hernández.

- Klein, Herbert. 1993. Haciendas and ayllus. Rural society in the Bolivian Andes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Larson, Brooke. 1988. Colonialism and agrarian transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Liehr, Reinhard. 1976. Orígenes, evolución y estructura socioeconómica de la hacienda hispanoamericana. Anuario de Estudios Americanos 33: 527–77.

- Lopera Mesa, Gloria Patricia. 2020. Creando posesión vía desposesión. Visitas a la tierra y conformación de resguardos indígenas en la Vega de Supía, 1559-1759. Fronteras de la Historia 25 (2): 120–56.

- McDonough, Kelly. 2017. Plotting indigenous stories, land, and people: primordial titles and narrative mapping in colonial Mexico. Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 17 (1): 1–30.