ABSTRACT

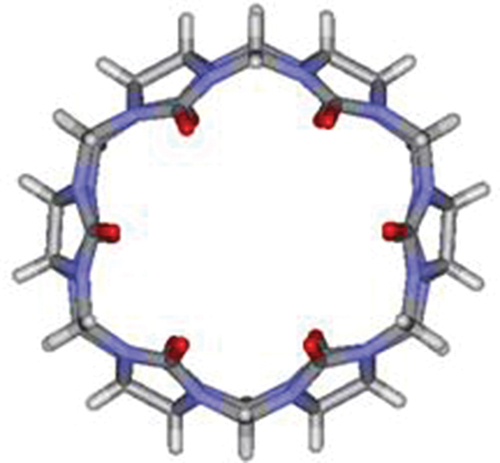

When Behrend, Meyer, and Rusche synthesised the first cucurbituril (a six subunit homologue) in 1905 [Citation1], they could not have known that an entire family of new macrocycles would be developed and researched. From their initial discovery not only do we now have more than seven different sized homologues, but they have expanded to include functionalised cucurbiturils, hemi-cucurbiturils, bambusurils, and inverted cucurbiturils, among many others [Citation2–6].

Not being able to elucidate its structure, the six subunit homologue was unnamed until its rediscovery by Freeman, Mock, and Shih in 1981. Liking it to the three-dimensional shape of a pumpkin, a prominent member of the Cucurbitaceae, or cucurbit, family of gourd plants, they suggested the ‘trivial’ name of cucurbituril [Citation7]. Given the knowledge of only a single homologue, no abbreviation was developed or suggested at this stage.

In 2000, when Kim and Day simultaneously discovered the 5, 7, 8, and 10 homologues it became necessary to use abbreviations to aid in reading and writing. While Kim chose the abbreviation CB[n] [Citation8], Day went with Qn [Citation9]. Since then, derivatives of both abbreviations, where the square brackets are omitted or added, Q[n] and CBn, have also been used. There have also been other rarely used abbreviations, such as Cuc and Cuc[6] [Citation10,Citation11].

The various abbreviations used for cucurbiturils are in contrast to other macrocycle families where consistent nomenclature is used. While there are many different sized cyclodextrins, the standard three commonly used in research are the 6, 7, and 8 homologues which are abbreviated as alpha-cyclodextrin (α-CD), beta-cyclodextrin (β-CD), gamma-cyclodextrin (γ-CD), respectively. Where other different sized cyclodextrins are referred to, the CD abbreviation is still used. Calixarenes are commonly abbreviated as CXn [Citation12] or CX[n] [Citation13], but there is no commonly used abbreviation for one of the newest members of the macrocycle family: pillar[n]arenes [Citation14].

So, of the four main cucurbituril abbreviations, Q[n], Qn, CB[n], and CBn, which one should remain in use?

The word cucurbituril is a blend of two words, ‘cucurbit’, and ‘glycoluril’, the latter being one of the two key reagents needed to make the macrocycle. Blends are formed through a morphological process in which portions of two separate words are fused together to create a single new word. This process does not follow a set of consistently specifiable rules that are common for other word formation processes, but the use of blends is common throughout the English language [Citation15].

Within the literature today, there are two main ways of pronouncing cucurbituril, which lead to the two different styles of its abbreviations: Q[n] and CB[n].

When pronounced as:

kew-kur-bi-tril /kjuːˈkəɹˌbɪtɹɪɫ/

this gives rise to the Q[n] or Qn abbreviation. In contrast, when pronounced as:

keh-kur-bi-tril /kəˌkəɹˈbɪtɹɪɫ/

this gives rise to the abbreviation as CB[n] or CBn.

These differences in pronunciation reflect the ways that speakers of English (from different dialectal groups) choose to assign stress to this word.

Stress is a phonological feature in which a syllable is pronounced to be more prominent than other syllables around it [Citation16]. The first pronunciation places the stress on the initial syllable of the word, while the second pronunciation shifts the stress to the second syllable, resulting in a vowel reduction on the initial syllable. It is a common feature of English that speakers can choose different stress patterns based on their dialect or subdialect for polysyllabic words, which is a flexible system provided by the language’s stress system itself. Other examples of differing stress patterns include /adult/ vs /a-dult/ or /par-ticipatory/ vs /partici-patory/.

Vowel reduction is a phonological process in which a vowel loses its prosody (the stress/importance formerly imposed on it) on an unstressed syllable and is reduced to a less polar (i.e. more neutral) sound; often a ‘schwa’, the vowel that requires the least movement of mouth and vocal cords to produce [Citation17], denoted in the International Phonetic Alphabet as [ə].

What this means is that the reduction of the initial-syllable vowel when the stress is on the second syllable leads to a different mental conception of the sound within the speaker’s mind. In the instance where stress is placed on the first syllable, the vowel quality is audibly recognisable as being similar to a /kju/ ‘que’ sound, and hence the Q[n]/Qn abbreviations.

In the case where vowel reduction is present, the representation of the sound isn’t recognisable as ‘que’ and instead it is pronounced as ‘keh’, and thus instead is abbreviated as CB[n]/CBn.

Of interest, there is no existing abbreviation that uses the letter ‘k’ based on the ‘hard c’ sound /k/, yet the Qn abbreviation is based on the ‘que’ /kju/ sound which is tied more strongly to its phonology. Instead, the CBn abbreviation is based on the orthography of the word, in which the two sounds of /k/ and /c/ are both represented through the Latin letter ‘c’.

Cucurbituril is partly derived from the term ‘cucurbit’, a term borrowed originally from French. Regardless of dialect, the stress for cucurbit has always traditionally been applied to the first syllable of the word (reference):

American: /kjuˈkərbət/ ‘kyu-kerbit’

British: /kjuːˈkəːbɪt/ ‘kyu-kebit’

Following the creation of the term ‘cucurbituril’, it would perhaps be best to adhere to the original pronunciation, with stress placed on the first syllable [Citation18].

Within academia, it is important to have general cohesion with terminology and abbreviations. This is to make work more accessible and easy to understand, as well as avoiding confusion and ambiguity.

Within linguistics, there can be variations in terminology that come from language-specific data, the theoretical beliefs of the author, or for stylistic choices. It is not the case that ‘cookie-cutter’ terms are applicable to every branch of the field. As such, it is hard to definitively claim something to be right or wrong (within a given set of parameters in which said variation is said to exist).

The English language does not have a singular rule for how stress should be applied to a polysyllabic word. Instead, it offers a variety of ways in which stress can be applied, which makes no one way more correct than another. This leads to different speech communities (dialectal groups, for example) choosing to conventionalise certain stress patterns.

As for the case of the stress on the word cucurbituril, both stress patterns are inherently correct, and allowable by English’s phonetic rules. With regard to the natural sciences, one style of abbreviation should be pushed for, especially with abbreviations. As such, deciding to settle on one convention must appeal to factors other than linguistic correctness.

One criteria could be to decide by means of common use and frequency by scientists within the recent literature and recent use shows a strong preference for CB over Q. From a Scopus database search using the key word ‘cucurbituril’ for 2023, 75 papers were found. Of these, 92% used some variation of CB with the other 8% using Q. For the CB abbreviations, 45 (69%) used CB[n], 15 used CBn, and 7 used just CB with no ‘n’ letter designation. One paper defined the abbreviation for cucurbituril to be CB[n], but then preceded to use CBn type abbreviations when referring to individual homologues and one paper used rounded brackets and a space: CB (n). For the six papers that used a Q abbreviation, four used Q[n] and two used Qn. Following this criterium, it could be argued that the CB abbreviation, accounting for 92% of usage in 2023, should become the sole abbreviation.

Alternatively, abbreviations have been in use in the English language since at least the 15th century for the purpose of allowing a message to be fitted into a shorter space or for the message to be written in a shorter time [Citation19]. So, if the purpose of the abbreviation is to save as much time and space as possible, then there is an argument for the use of Q (one character) over CB with two characters.

While saving space was particularly important prior to the 21st century for scientific journals when each edition was printed and shipped worldwide, and hence using Q would be more economical than the others, it becomes less significant in an era when most journal articles are accessed and stored electronically and so the common use criteria may dominate over economy.

Another argument in favour of CB over Q is potential confusion for readers who are not native speakers of English. Whereas the CB abbreviation comes from spelling of the word (Cucurbituril), the Q abbreviation comes from how the start of the word is pronounced in English. However, not all languages have similar orthographies with English, which can lead to various different pronunciations instead of ‘kyu’ in English. Likewise, there is also the problem that not all Latin-based writing systems, like Polish, use the Q letter. For these readers, it may not be clear from where the Q abbreviation comes and those new to the field may find themselves searching papers for a compound starting with the letter Q, which is not desired.

A final question is whether the abbreviation should use brackets? To help resolve this, it can be helpful to look for examples where confusion can arise from using one rather than the other. This is the case when discussing cucurbituril ions from mass spectrometry results, as the use of CB[n] can result in the awkward use of multiple square brackets; e.g. [CB[7]+Na+]+. In the absence of other drivers, this would indicate CBn to be a more appropriate abbreviation to adopt over CB[n].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Behrend R, Meyer E, Rusche F. I. Ueber condensationsproducte aus glycoluril und formaldehyd. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1905;339(1):1–37. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19053390102

- Lagona J, Mukhopadhyay P, Chakrabarti S, et al. The cucurbit[n]uril family. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44(31):4844–4870. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460675

- Mukhopadhyay RD, Kim K. Cucurbituril curiosities. Nat Chem. 2023;15(3):438. doi: 10.1038/s41557-023-01141-0

- Assaf KI, Nau WM. Cucurbiturils: from synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(2):394–418. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00273C

- Barrow SJ, Kasera S, Rowland MJ, et al. Cucurbituril-based molecular recognition. Chem Rev. 2015;115(22):12320–12406. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00341

- Shetty D, Khedhar JK, Park KM and Kim K. Can we beat the biotin–avidin pair? Cucurbit[7]uril-based ultrahigh affinity host–guest complexes and their applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(23):8747–8761. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00631G

- Freeman WA, Mock WL, Shih N-Y. Cucurbituril. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103(24):7367–7368. doi: 10.1021/ja00414a070

- Jaheon Kim I-SJ, Kim S-Y, Lee E, et al. New cucurbituril homologues: syntheses, isolation, characterization, and X-ray crystal structures of cucurbit[n]uril (n = 5, 7, and 8). J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122(3):540–541. doi: 10.1021/ja993376p

- Day A, Arnold AP, Blanch RJ, et al. Controlling factors in the synthesis of cucurbituril and its homologues. J Org Chem. 2001;66(24):8094–8100. doi: 10.1021/jo015897c

- Buschmann H-J, Cleve E, Jansen K, et al. The determination of complex stabilities between different cyclodextrins and dibenzo-18-crown-6, cucurbit[6]uril, decamethylcucurbit[5]uril, cucurbit[5]uril, p-tert-butylcalix[4]arene and p-tert-butylcalix[6]arene in aqueous solutions using a spectrophotometric method. Mater Sci Eng C. 2001;14(1–2):35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0928-4931(01)00206-5

- Neugebauer R, Knoche W. Host–guest complexes of cucurbituril with 4-amino-4′-nitroazobenzene and 4,4′-diaminoazobenzene in acidic aqueous solutions. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1998;2(3):529–534. doi: 10.1039/a708015h

- Kong Q, Liu L-L, Li Z. Synthesis of calix[4]arene-based porous organic cages and their gas adsorption. Chem Eur J. 2024;30(34):e202400947. doi: 10.1002/chem.202400947

- Gu A, Wheate NJ. Macrocycles as drug-enhancing excipients in pharmaceutical formulations. J Incl Phenom Macrocyc Chem. 2021;100(1–2):55–69. doi: 10.1007/s10847-021-01055-9

- Ogoshi T, Kanai S, Fuginami S, et al. Para-bridged symmetrical pillar[5]arenes: their Lewis acid catalyzed synthesis and host–guest property. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(15):5022–5023. doi: 10.1021/ja711260m

- Lahlou H, Abdullah IH. The fine line between compounds and portmanteau words in English: a prototypical analysis. J Lang Linguist. 2021;17(4):1684–1694. doi: 10.52462/jlls.123

- Matthews PH. The concise oxford dictionary of linguistics. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press UK, Great Britian; 2014.

- Hayes B, Kirchner R, Steriade D, editors. Phonetically based phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. p. 191–231.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. cucurbit (n.1). 2023 July. doi: 10.1093/OED/3560526883

- Honkapohja A, Marcus I. The long history of shortening: a diachronic analysis of abbreviation practices from the fifteenth to the twenty-first century. Engl Lang Linguist. 2023;28(1):43–71. doi: 10.1017/S1360674323000436