ABSTRACT

Background and objectives: Major negative life-events including bereavement can precipitate perceived positive life-changes, termed posttraumatic growth (PTG). While traditionally considered an adaptive phenomenon, it has been suggested that PTG represents a maladaptive coping response similar to cognitive avoidance. To clarify the function of PTG, it is crucial to establish concurrent and longitudinal associations of PTG with post-event mental health problems. Yet, longitudinal studies on this topic are scarce. The present study fills this gap in knowledge.

Design: A two-wave longitudinal survey was conducted.

Methods: Four-hundred and twelve bereaved adults (87.6% women) filled out scales assessing PTG and symptoms of depression, anxiety, prolonged grief, and posttraumatic stress at baseline and 6 months later.

Results: The baseline concurrent relationships between all symptom levels and PTG were curvilinear (inverted U-shape). Cross-lagged analyses demonstrated that symptom levels did not predict levels of PTG 6 months later, or vice versa.

Conclusions: Findings suggest PTG after loss has no substantive negative or positive effects on mental health. Development of specific treatments to increase PTG after bereavement therefore appears premature.

While bereavement is a universal experience, responses to this major negative life-event vary. Most people adjust to bereavement without needing professional help, yet bereavement can lead to negative health consequences. Mental health outcomes include development of major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance disorder and severe, enduring and disabling grief, also termed complicated grief or prolonged grief (Zisook et al., Citation2014). While negative health outcomes of bereavement have been well-documented, potential positive consequences have received limited attention.

The struggle with a stressful life-event can lead to the experience of positive life-changes, which have received various names, such as finding benefit (Affleck & Tennen, Citation1996), stress-related growth (Park, Cohen, & Murch, Citation1996) and – currently most commonly – posttraumatic growth (PTG: Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004).Footnote1 PTG includes feeling stronger, feeling closer to family and friends, and experiencing new possibilities, a greater appreciation of life, and/or positive spiritual change. PTG may be particularly likely to occur after bereavement. For example, losing a loved one may increase compassion towards other bereaved persons, thus increasing a feeling of connectedness. Similarly, losing a spouse could eventually lead someone to develop new activities to give new meaning to one’s life (Calhoun, Tedeschi, Cann, & Hanks, Citation2010). Indeed, PTG has been observed following bereavement through prenatal death, and the (non)violent death of family members and friends (e.g., Bartl, Hagl, Kotoučová, Pfoh, & Rosner, Citation2018; Currier, Holland, & Neimeyer, Citation2012; Engelkemeyer & Marwit, Citation2008; Shakespeare-Finch & Armstrong, Citation2010; Taku, Cann, Calhoun, & Tedeschi, Citation2008; Wagner, Knaevelsrud, & Maercker, Citation2007).

Despite ongoing interest in PTG, little consensus exists on factors leading to perceptions of positive life-changes, due to overreliance on cross-sectional designs, small samples, and unstandardized measures of PTG (for related critiques: Dekel, Ein-Dor, & Solomon, Citation2012; Engelhard, Lommen, & Sijbrandij, Citation2014). One key unresolved issue is whether PTG is an adaptive or maladaptive response to a stressful life-event. Traditionally, PTG is viewed as a beneficial outcome and/or an adaptive cognitive coping process (e.g., Park & Folkman, Citation1997; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004), but others consider PTG to be a similar to an avoidant/defensive strategy with self-deceptive elements which hamper recovery (e.g., Boals & Schuler, Citation2018; Frazier et al., Citation2009; Taylor & Armour, Citation1996; Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006). For instance, Zoellner and Maercker (Citation2006) posited the “Janus-face” model of PTG that holds that perceptions of PTG may be helpful in processing a major stressful life-event, but in part could also consist of distorted positive illusions that counterbalance emotional distress. For instance, a distressed widow could state that the experience of being bereaved has not made her poorer, but instead more richer and more mature, which may draw her attention away from her negative emotional reactions to this life-event. In line with this idea, PTG has been positively associated with emotion and problem-focused coping, but also with avoidant coping and denial in prior studies (Boals & Schuler, Citation2018). Avoidance of painful aspects of the loss is commonly assumed to hamper recovery from bereavement, as it limits the integration of the irreversibility of the loss with autobiographical memory, thereby maintaining acute grief reactions (Boelen, van den Hout, & van den Bout, Citation2006).

Clarifying the function of PTG is both theoretically and clinically important, as interventions to increase PTG in people suffering from stress-related psychopathology are increasingly applied (Roepke, Citation2015). One innovative method to shed light on the nature of PTG is by assessing the strengths of reciprocal longitudinal associations between PTG and post-event mental health (e.g., Blix, Birkeland, Hansen, & Heir, Citation2016; Dekel et al., Citation2012; Engelhard et al., Citation2014). In the present study, we aimed to investigate concurrent and – for the first time – reciprocal longitudinal associations between both constructs in bereaved people to gain a better understanding of PTG following loss.

Concurrent associations between PTG and mental health after loss

Addressing concurrent associations first, one might simply argue that if PTG is beneficial, more PTG should be negatively associated with mental health problems, and if it is a maladaptive process, PTG should be positively associated with mental health problems. However, previous studies in bereaved samples have yielded both positive and negative concurrent associations between prolonged grief symptoms and PTG (e.g., Currier et al., Citation2012; Engelkemeyer & Marwit, Citation2008) and positive and non-significant correlations between PTSD symptoms and PTG (e.g., Taku et al., Citation2008; Znoj, Citation1999). Such findings are largely comparable with research among people exposed to other stressful life-events (e.g., Kleim & Ehlers, Citation2009; Lechner, Carver, Antoni, Weaver, & Phillips, Citation2006). This has led some authors to suggest that curvilinear associations (inverted U-shape) might better explain the relationship under investigation (Kleim & Ehlers, Citation2009; Lechner et al., Citation2006; Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014).

Theoretically, this curvilinear effect holds that there are three basic ways of responding to a stressful life-event. A first group experiences little sense of crisis in response to the event and therefore little PTG; a second group may experience moderate levels of distress, yielding higher levels of PTG; and a third group experiences the event as too emotionally overwhelming to experience much PTG (cf. Lechner et al., Citation2006). Supporting this hypothesis, some studies demonstrated an inverted U-shaped association between prolonged grief and/or PTSD on the one hand and PTG on the other hand (Currier et al., Citation2012; Lechner et al., Citation2006; Znoj, Citation1999). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis showed that a curvilinear relationship more adequately describes the concurrent association between PTSD symptoms and PTG following a variety of stressful life-events (Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014). As for other types of psychopathology and PTG (which are rarely studied in bereaved samples), another meta-analysis showed that PTG is negatively associated with depression and unrelated to anxiety (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomic, Citation2006), but curvilinear associations were not assessed in this review. It thus remains to be established what the nature of the concurrent relationship is between PTG and typical post-loss mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and prolonged grief.

Longitudinal associations between PTG and mental health problems after loss

Turning next to the longitudinal associations between PTG and mental health, adaptive and maladaptive interpretations of PTG yield differential predictions. If PTG is the product of an adaptive cognitive coping process in response to distress experienced after a major negative life-event, one could expect a reciprocal relationship, where more event-related mental health problems would predict increases in PTG and – vice versa – more PTG would precede reductions in distress over time (Dekel et al., Citation2012). If PTG reflects a maladaptive coping process similar to self-deception and avoidance more event-related distress would also predict increased PTG; however, crucially, more PTG would also increase mental health problems over time.

Only one study to date has investigated longitudinal associations between mental health and PTG in bereaved persons. This study supported an adaptive interpretation. Davis, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Larson (Citation1998) showed that people who perceived more benefits of a loss generally experienced less general distress over time, especially longer after bereavement. That is, the longitudinal association between the answer to a one-item question “Have you found anything positive in the experience?” and self-reported distress became stronger over time, with benefit-finding at 13 months predicting lower distress at 18 months post-loss. However, when looking more generally at longitudinal associations between both constructs outside the bereavement area, results are (again) discordant. PTG has been longitudinally related to both lower and higher levels of post-event mental health problems (e.g., Davis et al., Citation1998; Engelhard et al., Citation2014; Zhou, Wu, & Chen, Citation2015). Similarly, mental health problems predicted increases in PTG in some studies but were non-significant predictors of PTG in others (e.g., Dekel et al., Citation2012; Engelhard et al., Citation2014; Hall, Saltzman, Canetti, & Hobfoll, Citation2015; Zhou et al., Citation2015). More research is therefore urgently needed to clarify the role of PTG in adaptation to major negative life-events.

The present study

We aimed to further clarify the function of PTG after bereavement. A first hypothesis was that curvilinear concurrent relationships exist between different mental health symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depression, prolonged grief, and post-traumatic stress) and PTG after loss. To test this hypothesis, we used data from archival community samples of bereaved people with varying (i.e., non-clinical to clinical) levels of mental health problems, which is necessary to study the existence of the curvilinear effect. Nevertheless, the investigation of these concurrent associations does not in itself clarify the role of PTG in post-loss adaptation. Therefore, the second aim of the present study was to assess reciprocal longitudinal associations between post-loss distress and PTG, using a cross-lagged panel model. Based on the only prior longitudinal study on PTG after bereavement (Davis et al., Citation1998), we expected more PTG would be related to lower levels of anxiety, depression, prolonged grief, and PTSD after six months. In line with both the adaptive and maladaptive interpretation of PTG, we further hypothesized that higher baseline anxiety, depression, prolonged grief, and PTSD symptoms would be associated with higher PTG after six months.

Method

Procedure and participants

Research was conducted in accordance with Dutch legislation and professional ethical regulations of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The current investigation is based on data from two longitudinal studies of bereaved samples, in which the mental health indices used in the present study were dependent variables. (Eisma et al., Citation2013, Citation2015). People bereaved of a first-degree relative less than three years previously were recruited for these studies through advertisements on websites of organizations for bereaved individuals and Google’s content network, linking to the project’s website.

In Study 1, people could fill out their address online and would receive a posted package containing an information letter (e.g., on goals, privacy, anonymity), informed consent form, questionnaire, and a return envelope. In Study 2, participants accessed an online questionnaire after reading the same study information and giving informed consent. After the baseline survey, participants were asked if they would be willing to fill out an additional questionnaire and, if so, were sent questionnaires again 6 and 12 months after baseline by post (Study 1) or e-mail (Study 2).

The present study combines data from Study 1 and Study 2 and focuses only on measures administered at 6 and 12 months follow-up, because measures of PTG were administered only at these time-points, which for easy reference will be referred to as T1 (N = 410) and T2 (N = 339 – including 2 participants who only filled out the T2 questionnaires), respectively. shows the total sample characteristics (N = 412). Participants (87.6% women, M age: 50.43 years; SD: 11.70 years) experienced the loss of a first-degree family member on average 20 months previously (M: 20.24; SD: 9.83). Most had lost a partner (46.7%) or parent (27.2%) due to natural causes (85.0%).

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 412).

Instruments

All instruments mentioned below were included in questionnaires administered at T1 and T2 in both studies, except the PTSD Symptom Scale (Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, Citation1997) which was only administered in Study 1 (N = 227).

Sociodemographic and loss characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics (age in years, gender (male/female), education level (low/high), and loss characteristics (kinship (partner, child, sibling, parent), time since loss in months, cause of death (non-violent or violent – i.e., accident, murder, or suicide), and expectedness of loss (expected, unexpected, other)) were assessed using a self-constructed questionnaire.

Posttraumatic growth

Posttraumatic growth was assessed with the 10-item Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form (PGI-SF: Cann et al., Citation2010). The PGI-SF assesses perceived positive life-changes after adversity across five domains: relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change and appreciation of life. Participants gave a number ranging from 0 (I did not experience this change as result of bereavement) to 5 (I experienced this change to a very great degree as result of bereavement) in response to each item. The PGI-SF was translated and back-translated by two independent persons fluent in both Dutch and English. Minor differences between the original PGI-SF and the back-translated version were resolved by making appropriate changes to the Dutch PGI-SF. Reliability of the PGI-SF in the current sample at T1 was good, α = .85.

Anxiety and depression symptoms

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS: Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983: Dutch translation: Spinhoven et al., Citation1997). The HADS consists of an anxiety and a depression subscale, each containing seven statements on experiences representing anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively. Participants filled out how often or to what extent they had these experiences in the past week on 4- point scales. Reliability of the anxiety and depression subscales was good to excellent at T1in this sample, α = .88, and, α = .90, respectively.

Prolonged grief symptoms

Prolonged grief symptoms were measured with the ICG–R, a reliable and valid instrument to assess symptoms indicative of pathological grief (Prigerson & Jacobs, Citation2001; Dutch translation: Boelen, van den Bout, de Keijser, & Hoijtink, Citation2003). The Dutch version includes 29 statements that each represent a symptom. Participants report how often/intensely they experienced each symptom in the past month on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (almost never) to 4 (always). Internal consistency of the ICG–R was excellent at T1 in this sample, α = .97.

Ptsd symptoms

Symptoms of PTSD were assessed with the PTSD Symptom Scale (PSS: Foa et al., Citation1997; Dutch translation: Engelhard, Arntz, & Van den Hout, Citation2007). The PSS consists of 17 statements tapping DSM-IV based symptoms of PTSD. Participants report on 4-point scales how often or how intensely they have experienced certain symptoms over the past month in response to their loss. The reliability of the PSS was excellent at T1 in the present sample, α = .90.

Statistical analyses

We used SPSS 24 and MPlus 5.2 for analyses. First, we tested whether there were group differences on demographic and loss-related characteristics and mental health problems between participants who did or did not drop out between T1 and T2, and between participants derived from Study 1 and Study 2, using Chi-square and t-tests. We also computed zero-order correlations between PTG and mental health problems.

Next, we used four multiple hierarchical regression analyses to calculate concurrent linear and quadratic associations between PTG and each indicator of mental health problems at T1, using a dichotomous dummy variable “sample” (representing in which study the participant was included (i.e., Study 1 or Study 2)) as a covariate. In each regression analysis, the dummy variable “sample” was entered in a first step. Next, baseline symptom levels were entered as a predictor to assess the linear relationship between symptom levels and PTG. In a third step, squared baseline symptom levels were entered to assess the curvilinear relationship between symptom levels and PTG.

Lastly, we conducted a series of cross-lagged panel models. Four models were estimated to test the reciprocal relationships between PTG and anxiety, depression, prolonged grief or PTSD symptoms. Autoregressive paths were included in each model to account for the association between the same constructs over time. Cross-lagged effects were estimated to test the predictive effect of a construct at T1 to the other construct at T2, while controlling for the autoregressive effect. If the results from zero-order correlation analyses showed significant associations between the constructs at the same time-point, these associations were taken into account in the cross-lagged models. A dichotomous variable “sample” representing in which study the participant was included (i.e., Study 1 or Study 2), was included as covariate by regressing each construct at both time points onto this variable. To explore whether type of loss (expected vs. unexpected) influenced the findings (given that an unexpected loss is a correlate of PTSD; Atwoli et al., Citation2017), we ran a second round of analyses, but now only including people who had experienced an unexpected loss (n = 215). A maximum likelihood estimator was used. Full information maximum likelihood was used to handle missing data. All significance tests were two-tailed (α = .05).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Prolonged grief levels ranged from non-clinical to clinical, with 56.0% of participants at T1 scoring above the cut-off of 25 on the summed 19 items of the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG: Prigerson et al., Citation1995), that are included in the ICG-R (Prigerson & Jacobs, Citation2001; Boelen et al., Citation2003). Two-fifth of the sample at T1 (45.5%) scored above 7, a clinical cut-off point for depression, on the HADS (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, Citation2002).

No significant differences were found between study completers (n = 339; 82.7%) and participants who only completed the T1 questionnaire (n = 71, 17.3%) on loss-related variables, demographics, or symptom levels. However, participants in Study 1 had a longer time since loss, t(408) = 9.13, p < .001, and were more likely to have experienced child-loss, 19.4% vs. 8.7%, χ²(4) = 19.2, p < .001, and unexpected loss, 59.0% vs. 43.5%, χ²(4) = 9.9, p = .01, compared to participants in Study 2. No differences were found between studies on the cause of loss, age, gender, education level, or symptoms of anxiety, depression, or prolonged grief at T1 (all ps > .05). A categorical variable “sample” (Study 1 = 0; Study 2 = 1) was included as a covariate in all main analyses, except those involving PTSD symptoms as these data were from Study 1 only. Zero-order correlations between T1 PTG and anxiety, depression, PTSD, and prolonged grief symptoms are depicted in .

Table 2. Zero-order correlations between T1 PTG and symptoms of anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and PTSD.

Concurrent curvilinear associations between posttraumatic growth and mental health

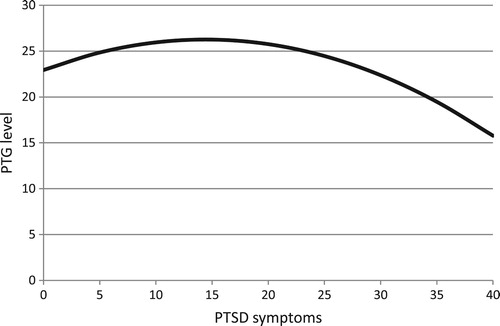

All hierarchical regression analyses of PTG on mental health symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and PTSD) showed a similar pattern of results: adding squared symptom levels as predictor to a regression model in which (unsquared) symptom levels predict PTG, significantly improved the explanatory value of the regression model. In all models, squared symptom levels were a stronger predictor of PTG than (unsquared) symptom levels (i.e., showing higher standardized regression coefficients), implying that a nonlinear model more adequately described the concurrent relationship between distress and PTG than a linear model. shows the final standardized model for each analysis. As an illustration of the patterns of results shows the unstandardized regression model of the curvilinear relationship of PTSD symptoms with PTG levels.

Figure 1. Unstandardized estimated curvilinear relation between PTSD and PTG at T1.

Note: PTG = posttraumatic growth. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. ŷ = 22.941 + 0.461 * x – 0.016 * x².

Table 3. Hierarchical regression analyses testing for curvilinear effects of T1 anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and PTSD symptoms on PTG.

Cross-lagged associations of posttraumatic growth and mental health symptoms

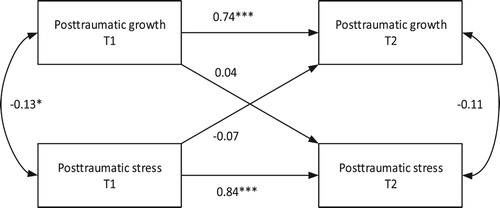

The bidirectional associations between PTG and anxiety, depression, prolonged grief, or PTSD levels were tested in four separate cross-lagged models. All models were saturated models with zero degrees of freedom and a comparative fit index of 1. As an illustration of the model that was applied, presents a schematic display of the cross-lagged model for PTG and PTSD levels. See for a summary of the results of all cross-lagged analyses.

Figure 2. Cross-lagged model with standardized coefficients for posttraumatic growth and PTSD.

Note: T1 = time point 1; T2 = time point 2; * p < .05. *** p < .001.

Table 4. Standardized results of the cross-lagged models.

All autoregressive effects for PTG and mental health symptoms were significant (all ps < .001) when controlling for all other parameters. PTG at T1 was significantly associated with each mental health outcome at T1 (all ps < .05). PTG at T2 was significantly associated with depression levels at T2 (β = −0.27, SE = 0.05, p < .001), but not with anxiety, prolonged grief, and PTSD levels at T2 (all ps > .05). None of the cross-lagged effects from PTG to mental health symptoms or vice versa were significant (all ps > .05, all R²s < .01). In a second round of analyses we estimated similar models for people who were exposed to an unexpected loss (n = 215). These models yielded similar results to the first cross-lagged analyses, i.e., it did not change the number and type of significant effects (see ). Since cross-sectional analyses indicated a curvilinear association between mental health and PTG, we additionally ran post-hoc analyses of all cross-lagged models including squared T1 symptom levels as an additional predictor of T2 PTG levels. These models also did not yield significant effects of mental health on PTG over time (all ps > .05, all R² s < .01) and are therefore not reported.

Discussion

The current investigation aimed to clarify the concurrent and longitudinal associations between distress and PTG after bereavement. Confirming expectations, the cross-sectional relationship between different types of post-loss mental health problems and PTG was curvilinear. The highest levels of PTG were on average reported by people who experienced moderate levels of anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and PTSD, whereas people who reported lower or higher symptom levels generally reported less PTG. Unexpectedly, symptom levels of anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and PTSD did not significantly predict PTG, or vice versa.

The concurrent nonlinear association between PTSD symptoms and PTG corresponds with results in populations who had experienced other types of stressful life-events (Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, Citation2014). Our study uniquely shows that this association may generalize across anxiety, depression and prolonged grief. The results confirm the idea that a person needs to experience a certain level of distress in order to perceive positive life-changes, but that high levels of distress will limit the benefits one can find. Our longitudinal analyses shed more light on the function of PTG. While traditionally considered a positive coping effort or positive outcome of an adverse event (e.g. Park & Folkman, Citation1997; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004), it has been suggested that PTG may (also) consist of illusory, self-deceptive components, thereby hampering adjustment (e.g. Boals & Schuler, Citation2018; Frazier et al., Citation2009; Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006). Intriguingly, longitudinal analyses did not strongly support either theoretical position: PTG did not predict symptoms of anxiety, depression, prolonged grief, or PTSD, or vice versa. Thus, findings did not confirm results from the only prior longitudinal study on this topic, which showed that perceived benefit was related to lower bereavement-related distress over time (Davis et al., Citation1998).

Considering our results in the context of previous findings in samples of bereaved samples and people who experienced other types of stressful life-events, our research demonstrates that PTG does not consistently predict better or worse outcomes (e.g., Davis et al., Citation1998; Dekel et al., Citation2012; Engelhard et al., Citation2014; Zhou et al., Citation2015). This suggests that it is important not to view PTG as either adaptive or maladaptive. Rather, findings support a view that PTG can have both adaptive and maladaptive effects under certain circumstances, and sometimes adaptive and maladaptive effects will balance each other out. A key challenge to future research is to uncover which factors moderate longitudinal effects of PTG on mental health (and vice versa). For example, one recent study focused on resource loss as a potential moderator of the longitudinal association between PTG and PTSD symptoms, finding no evidence for interaction effects (Zalta et al., Citation2017). Large-scale future research examining multiple potential moderators is warranted. Alternatively, some researchers are adopting a different approach, by taking steps to separate the adaptive components of PTG from its maladaptive components. For example, Boals and Schuler (Citation2018) developed an adaptation of the Stress-Related Growth Scale, which is aimed at reducing the odds that participants report illusory growth. Another method to circumvent the problem of distinguishing adaptive from maladaptive components of PTG is by assessing actual growth over time, eliminating the possibility that people indicate that they have experienced positive life-changes while in fact they have not (Frazier et al., Citation2009).

From a clinical viewpoint, it is noteworthy that several authors examined interventions focused on increasing PTG in people who experienced negative life-events (e.g., Chan, Chan, & Ng, Citation2006; Dolbier, Jaggars, & Steinhardt, Citation2010). Based on the results of the current investigation, and other studies showing negative effects of PTG on PTSD over time (e.g., Engelhard et al., Citation2014), it seems premature to develop similar interventions to help bereaved individuals. Increasing PTG may not reduce distress and it is possible that these interventions (under some circumstances) may even be harmful. For example, strongly stimulating non-realistic perceptions of positive life-changes in people who are highly distressed may strengthen cognitive avoidance, thereby hampering adjustment to bereavement (Boelen et al., Citation2006; Eisma et al., Citation2013).

Limitations

The following limitations warrant mention. First, participants were predominantly middle-aged women. While we have no reasons to assume that a different sample composition would change study outcomes, future research should aim to clarify whether results generalize across younger or older samples, with more men. Second, the sample was subclinical and it did not include persons in the acute phase of their loss (< 6 months). Nevertheless, the mental health difficulties experienced by our sample were still substantial, with close to half meeting proposed clinical cut-offs for depression and prolonged grief. Given that longitudinal associations between both constructs have been found among other samples exposed to a major negative life-event more than 6 months (and even several years) previously (e.g., Blix et al., Citation2016; Dekel et al., Citation2012; Zhou et al., Citation2015), time since the event probably does not (fully) explain these results. Third, this study employed a self-reported PTG measure, but it could be more informative to measure actual growth over time. Associations between scores on the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996) and actual growth are modest (Frazier et al., Citation2009). Fourth, to assess potential benefits of PTG we confined ourselves to mental health indices. Using additional indicators to measure potential benefits of PTG (e.g., life satisfaction, quality of life) could strengthen designs of future investigations.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrates that concurrent associations between multiple indices of mental health and PTG are nonlinearly related following bereavement. Moreover, the present study was the first to apply cross-lagged panel models on PTG and mental health in bereaved persons, showing that PTG did not predict post-loss mental health, or vice versa. Findings provided no support for theories that view PTG as adaptive or maladaptive, and suggest that development of treatments specifically designed to increase PTG in bereaved individuals may be inopportune.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Maarten C. Eisma http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6109-2274

Lonneke I. M. Lenferink http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1329-6413

Margaret S. Stroebe http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8468-3317

Paul A. Boelen http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4125-4739

Henk A. W. Schut http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8744-4322

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Definitions of the constructs representing the experience positive life-changes after stressful life-events differ between studies and over time. For clarity, we will refer to these constructs with the currently most often applied term: posttraumatic growth (PTG).

References

- Affleck, G., & Tennen, H. (1996). Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. Journal of Personality, 64, 899–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00948.x

- Atwoli, L., Stein, D. J., King, A., Petukhova, M., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., … Maria Haro, J. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder associated with unexpected death of a loved one: Cross-national findings from the world mental health surveys. Depression and Anxiety, 34, 315–326. doi: 10.1002/da.22579

- Bartl, H., Hagl, M., Kotoučová, M., Pfoh, G., & Rosner, R. (2018). Does prolonged grief treatment foster posttraumatic growth? Secondary results from a treatment study with long-term follow-up and mediation analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 91(1), 27–41. doi: 10.1111/papt.12140

- Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

- Blix, I., Birkeland, M. S., Hansen, M. B., & Heir, T. (2016). Posttraumatic growth - an antecedent and outcome of posttraumatic stress: Cross-lagged associations among individuals exposed to terrorism. Clinical Psychological Science, 2167702615615866. doi: 10.1177/2167702615615866

- Boals, A., & Schuler, K. (2018). Shattered cell phones, but not shattered lives: A comparison of reports of illusory posttraumatic growth on the posttraumatic growth Inventory and the stress-related growth scale—revised. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. doi: 10.1037/tra0000390

- Boelen, P. A., van den Bout, J., De Keijser, J., & Hoijtink, H. (2003). Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the Inventory of Traumatic Grief (ITG). Death Studies, 27(3), 227–247. doi: 10.1080/07481180302889

- Boelen, P. A., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2006). A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 109–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00013.x

- Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., & Hanks, E. A. (2010). Positive outcomes following bereavement: Paths to posttraumatic growth. Psychologica Belgica, 50, 125–143. doi:10.5334/pb-50-1-2-125

- Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Taku, K., Vishnevsky, T., Triplett, K. N., & Danhauer, S. C. (2010). A short form of the posttraumatic growth Inventory. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 23, 127–137. doi: 10.1080/10615800903094273

- Chan, C. L., Chan, T. H., & Ng, S. M. (2006). The strength-focused and meaning-oriented approach to resilience and transformation (SMART) a body-mind-spirit approach to trauma management. Social Work in Health Care, 43, 9–36. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n02_03

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2012). Prolonged grief symptoms and growth in the first 2 years of bereavement: Evidence for a nonlinear association. Traumatology, 18, 65–71. doi: 10.1177/1534765612438948

- Davis, C. G., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Larson, J. (1998). Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 561–574. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.561

- Dekel, S., Ein-Dor, T., & Solomon, Z. (2012). Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic distress: A longitudinal study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 94–101. doi: 10.1037/a0021865

- Dolbier, C. L., Jaggars, S. S., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2010). Stress-related growth: Pre-intervention correlates and change following a resilience intervention. Stress and Health, 26, 135–147. doi: 10.1002/smi.1275

- Eisma, M. C., Stroebe, M. S., Schut, H. A., Stroebe, W., Boelen, P. A., & van den Bout, J. (2013). Avoidance processes mediate the relationship between rumination and symptoms of complicated grief and depression following loss. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(4), 961–970. doi: 10.1037/a0034051

- Eisma, M. C., Schut, H. A., Stroebe, M. S., Boelen, P. A., van den Bout, J., & Stroebe, W. (2015). Adaptive and maladaptive rumination after loss: A three-wave longitudinal study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 163–180.

- Engelhard, I. M., Arntz, A., & Van den Hout, M. A. (2007). Low specificity of symptoms on the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom scale: A comparison of individuals with PTSD, individuals with other anxiety disorders and individuals without psychopathology. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(4), 449–456. doi: 10.1348/014466507X206883

- Engelhard, I. M., Lommen, M. J., & Sijbrandij, M. (2014). Changing for better or worse? Posttraumatic growth reported by Soldiers Deployed to Iraq. Clinical Psychological Science, 2167702614549800. doi: 10.1177/2167702614549800

- Engelkemeyer, S. M., & Marwit, S. J. (2008). Posttraumatic growth in bereaved parents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 344–346. doi: 10.1002/jts.20338

- Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445–451. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445

- Frazier, P., Tennen, H., Gavian, M., Park, C., Tomich, P., & Tashiro, T. (2009). Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychological Science, 20, 912–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02381.x

- Hall, B. J., Saltzman, L. Y., Canetti, D., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2015). A longitudinal investigation of the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth in a cohort of Israeli Jews and Palestinians during ongoing violence. PLoS ONE, 10, e0124782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124782

- Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797

- Kleim, B., & Ehlers, A. (2009). Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between posttraumatic growth and posttrauma depression and PTSD in assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22, 45–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20378

- Lechner, S. C., Carver, C. S., Antoni, M. H., Weaver, K. E., & Phillips, K. M. (2006). Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 828–840. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.828

- Park, C. L., Cohen, L. H., & Murch, R. L. (1996). Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality, 64, 71–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x

- Park, C. L., & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1, 115–144. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.115

- Prigerson, H. G., & Jacobs, S. C. (2001). Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder: A rationale, consensus criteria and a preliminary empirical test. In Stroebe M. S., Hansson R. O., Stroebe W., & Schut H. (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping and care (pp. 613–646). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds III, C. F., Bierhals, A. J., Newsom, J. T., Fasiczka, A. … Miller, M. (1995). Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1–2), 65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2

- Roepke, A. M. (2015). Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(1), 129–142. doi: 10.1037/a0036872

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Armstrong, D. (2010). Trauma type and posttrauma outcomes: Differences between survivors of motor vehicle accidents, sexual assault, and bereavement. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15, 69–82. doi: 10.1080/15325020903373151

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Lurie-Beck, J. (2014). A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.10.005

- Spinhoven, P. H., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P. A., Kempen, G. I. J. M., Speckens, A. E. M., & Van Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27(2), 363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382

- Taku, K., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2008). The factor structure of the posttraumatic growth Inventory: A comparison of five models using confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 158–164. doi: 10.1002/jts.20305

- Taylor, S. E., & Armour, D. A. (1996). Positive illusions and coping with adversity. Journal of Personality, 64, 873–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00947.x

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventor: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Wagner, B., Knaevelsrud, C., & Maercker, A. (2007). Post-traumatic growth and optimism as outcomes of an internet-based intervention for complicated grief. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(3), 156–161. doi: 10.1080/16506070701339713

- Zalta, A. K., Gerhart, J., Hall, B. J., Rajan, K. B., Vechiu, C., Canetti, D., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Self-reported posttraumatic growth predicts greater subsequent posttraumatic stress amidst war and terrorism. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(2), 176–187. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1229467

- Zhou, X., Wu, X., & Chen, J. (2015). Longitudinal linkages between posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors following the Wenchuan earthquake in China: A three-wave, cross-lagged study. Psychiatry Research, 228, 107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.024

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

- Zisook, S., Iglewicz, A., Avanzino, J., Maglione, J., Glorioso, D., Zetumer, S., … Pies, R. (2014). Bereavement: Course, consequences, and care. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(10), 482. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0482-8

- Znoj, H. J. (1999). European and American perspectives on posttraumatic growth: A model of personal growth. Life challenges and transformation following loss and physical handicap. Paper presented at American Psychological Association, Boston, USA. Paper Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED435886.pdf

- Zoellner, T., & Maercker, A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology - a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008