ABSTRACT

Meta-analyses indicated detrimental effects on some psychological dimensions from job loss and extended periods of unemployment. This study analyses three phenomena: causes attributed to unemployment; processes for coping with unemployment; and the emotional impact of joblessness. Using an SEM approach, a model is created in which unemployment normalization acts as a mediator between locus of control and emotions. Method: questionnaires from 260 unemployed people in Luxembourg provided data on perceived control, coping, and emotions. Participants who attribute their situation to bad luck, believe more strongly that unemployment is due to external factors beyond their control, and recognize unemployment as being a common occurrence in life. Such cognitive attribution of unemployment has effects on job seekers’ emotions. Those who perceive unemployment in a more positive light experience more positive emotions and fewer negative affects. Negative perceptions of unemployment have no effect on the generation of positive emotion, but have an influence on negative affects. Finally, the influence of perceived-control on emotion is not direct, but is mediated by processes of unemployment normalization. Understanding how unemployed people perceive and experience their situations could help them be more effective in their search for new employment.

Introduction

Unemployment is one of the most important and heavily discussed phenomena of our time, and it is a serious economic and social problem all over the world. The topic of unemployment has certainly been the subject of many studies. For decades in psychology, a wide range of research has been conducted on the individual and social aspects that can explain the experience of unemployment, with the goal of defining an effective intervention strategy (Eisenberg & Lazarsfeld, Citation1938).

From a technical point of view, unemployment is defined as the status of all people above a specific age who are currently available for work, seeking work, but without work during some reference period (International Labour Office, Citation2000). Paul and Moser (Citation2006) argued that “This definition shows that unemployment is a complex, multidimensional construct, involving not only situational aspects (non-employment), but also motivational aspects (‘seeking work’) and medical and legal aspects (being ‘available for work’)” (p. 597).

The adverse effects of being unemployed are not just limited to socioeconomic factors (e.g., financial instability and lack of job security), but they also extend to psychological and emotional functions. Since the development of Jahoda’s latent deprivation theory (Citation1983), there has been wide acceptance that not only does employment have an evident economic function, but it also has latent functions that satisfy basic human needs. For these reasons, job loss is a problematic event that deeply influences a person’s life. Furthermore, Frey and Stutzer (Citation2002) referred to the psychic and social costs of unemployment by pointing out how unemployment causes depression, as well as the related stigma. Many studies in the social and behavioral sciences have shown the deleterious effects of unemployment on very different aspects of mental health and well-being. In particular it is linked to a gradual decrease in subjective well-being, or a gradual increase in negative emotions such as anger, fear, or sadness (McKee-Ryan et al., Citation2005; Paul & Moser, Citation2006, Citation2009). These effects are usually called stress reactions and are due to the feeling that one is not adequately able to cope with the situation (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). According to these results, and because unemployment may be considered as one of the main stressors of life, it has negative effects on well-being and emotions. Coping processes are used as a specific behavioral response in this stressful situation. Thus, some studies have proposed some partial models for coping with unemployment, including emotional processes and effects on subjective health.

Amundson and Borgen (Citation1982), for example, focused on emotional reactions after job loss. In their model, these authors suggested that the experience of unemployment begins with a reaction to job loss that is comparable to the grieving process. This process involves five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. According to this model, losing a job would represent a significant emotional and life involvement loss. Placing the process along a continuum, the end of the grieving process is the beginning of the job search. The authors maintained that the steps of the job search resembled the four steps of the burnout process: enthusiasm, stagnation, frustration, and apathy. After applying for different positions with no positive feedback, the unemployed person’s sense of motivation and hope decreases, and he or she seems to be resigned to give up. The model proposed by Amundson and Borgen (Citation1982) also describes the dynamics of unemployment as an “emotional roller coaster” characterized by different job-loss-job-seeking factors that are located along a continuum. In particular, the initial set of forces – related to the loss of one’s job and the grieving process – represents the downward trajectory of the roller coaster, which impedes the ability to engage in an effective job search. Next, the forces characterized by the acceptance of job loss and enthusiasm for the job search represent the positive and upward trend in the emotional path in the experience of unemployment. In the end, in the burnout process, a second set of negative factors, representing the other downward trajectory of the roller coaster, renders the job-seeking activity ineffective.

In the field of work, coping processes have been studied quite widely. In particular, this has concerned the experience of unemployment, and the use of strategies based on proactive behaviors which positively affect well-being and perceived uncertainty. To explain the active processes of coping with unemployment, several models have been suggested over many years (DeFrank & Ivancevich, Citation1986; Gowan & Gateway, Citation1997; Latack et al., Citation1995; Leana & Feldman, Citation1988; Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2018; Waters, Citation2000). Even if these models differed from each other, a general functional structure of coping with unemployment may be described. A period of unemployment is cognitively appraised by individuals. Its perception depends upon personal and individual factors, but also on social and economic conjuncture. As experiencing joblessness is considered to be a stressful experience, a coping process is created during a period of unemployment. This is composed of two dimensions: a cognitive reappraisal which balances (i.e., decreases) the gap between reality and expectations; and emotional adaptation which balances situational arousal. Thus, this kind of coping strategy implicates a double-behaviors process (with cognitive and emotional elements) to keep psychological equilibrium during unemployment. This process implicates the long-term effects or outcomes of psychological, social and physiological well-being.

From these various studies, and the heuristic models for coping with unemployment that they highlight, it appears that an emotional dimension must be taken into account in the psychological analysis of the effects of job loss. Firstly, some studies postulate that a period of unemployment leads to an increase in negative emotions, generated by the realities of being without work. The main effect of the coping process would tend to be towards a decrease in these emotions, thus allowing for emotional rebalancing during this period (e.g., Paul & Moser, Citation2009). At this level, emotions should be considered as an effect of the coping process. Nevertheless, at a secondary level, the emotional dimension should be seen as an integrated part of the process of personal reaction to unemployment (named dynamic of unemployment by Amundson & Borgen, Citation1982; or active processes of coping with unemployment by Gowan & Gateway, Citation1997). Thus, the emotional dimension of the strategy of coping with unemployment can then be understood in two ways: (1) a main effect of the process of coping with unemployment and (2) a main part of this coping process mechanism.

The main difference between these two processual positions is the place taken by emotions that are the consequences of the process, on the one hand, and the active part of the process itself, on the other hand.

At the end of the 1980s, some strands of research challenged the conventional view of the negative effects of unemployment. Given the increasingly high rate of unemployment and widespread job insecurity, defined as “employees’ perceptions and concerns about potential involuntary job loss” (Silla et al., Citation2009, p. 2), different authors hypothesized some changes in the way people view and react to this phenomenon. Clark (Citation2003) even suggested the development of “unemployment as a social norm” (p. 325), which might currently be replacing the classic social work norm. In Citation1992, Schaufeli and VanYperen adopted the new concept of unemployment normalization, emphasizing the idea that unemployment is becoming a more socially accepted phenomenon. Ashforth and Kreiner (Citation2002) defined normalization as a process that allows people to manage their emotions and render certain life experiences more acceptable and ordinary. In line with this perspective, Pignault and Houssemand (Citation2017) considered unemployment a stressful situation, subject to a normalization process that is a form of emotional regulation and an adaptive response to the new situation. In other words, the unemployment normalization process is considered an emotion-focused coping strategy, based on a cognitive reappraisal that allows people to look at unemployment as a normal and inevitable phase of life in a person’s career path that can be attributed to external and uncontrollable factors. This process of normalization can be considered as an emotion-focused coping strategy, used for regulating emotional response to a problem, which in this case is job loss and unemployment. It consists of cognitive processes directed at lessening or increasing emotional distress (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Thus, Latack et al. (Citation1995) pointed out that the distinction between different types of coping strategy is arbitrary because the same processes could be used to accomplish the desired goal. Moreover, Gowan and Gateway (Citation1997) proposed that “emotion-focused coping strategies can be considered to be cognitive” (p. 287), and thus differ from problem-focused coping strategies essentially because actions used are not directly related to modifying the external event.

In a study on the coping strategies of people facing unemployment, Pignault (Citation2011) found that unemployed people banalized and described unemployment as a result of external circumstances. One outcome of the normalization process is that the emotions and feelings that are related to the experience of being unemployed are perceived as less negative, and in turn, stress may decrease (Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2018). From these studies, the normalization process seems to be a potential coping strategy during a period of unemployment. It emerges from the stress caused by unemployment, it is based on cognitive reappraisal and emotional adaptation, and it permits a psychological re-equilibrium by increasing well-being. A process model of normalization was proposed (Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017) and included two successive and interrelated dimensional behaviors. The first, the cognitive dimension, is based on individual explanations made for unemployment. These could be external justifications (crisis, firms) or fatalistic explanations (social and economic changes). The second, the emotional dimension, is composed of two contradictory feelings which are moderately correlated: alternating periods of negative and positive perception of unemployment. The specific coping process had an impact on subjective health. Considering the general model of coping with unemployment and the specific model of normalization, some parallels can be found. Indeed, both models would explain a complex and multilayered process that takes place during unemployment, when an individual has to adapt and cope with a situation that generates stress for him or herself. In this sense, the cause of this reaction is the same for these two explanatory models. Moreover, these two models have a common operational structure which proposes two complementary components (a cognitive process and an emotional process) which are aimed at achieving cognitive reappraisal and emotional adaptation. Finally, the aim of these two models when coping with unemployment is a return to psychological equilibrium during this phase of life, a decrease in negative emotions, as well as better mental health and wellbeing. In this sense, and by the similarity at the descriptive, structural, functional and adaptive levels, a parallel between the general model of coping with unemployment and that of normalization can reasonably be postulated. This would therefore suggest that the normalization of unemployment would be a specific process for coping with unemployment, with this taking place according to particular psychological characteristics and specific social and economic conditions.

The experience of unemployment is fostered by several individual factors (Houssemand et al., Citation2014; Meyers & Houssemand, Citation2010). Coping strategies are moderated by personality (e.g., locus of control or self-esteem) and situational factors (e.g., labor economic conditions or social support) (Leana & Feldman, Citation1988). Locus of control in particular is one of the best predictors of finding re-employment (Houssemand et al., Citation2019). Locus of control (LOC) is the generalized belief of individuals that events in their lives depend on internal or external factors (Rotter, Citation1966). In particular, people with an internal locus of control feel that they are responsible for what happens to them, whereas people with an external locus of control feel that they are affected by events over which they have no influence. Levenson (Citation1974) reviewed this construct and adopted a new multidimensional structure for it with three factors: an internal locus on the one hand and two types of external locus on the other: chance and powerful others. In the literature, locus of control and perceived control have been studied and connected with the perception and experience of unemployment (Houssemand et al., Citation2014, Citation2019; Meyers & Houssemand, Citation2010). These authors found that when people face a negative or stressful situation (e.g., unemployment), they always ask themselves “Why?” and their answer has a significant influence on their emotional reactions (e.g., Wanberg, Citation1997). Some studies have also shown that LOC can change with the duration of the period of unemployment, becoming increasingly external over time (e.g., O'Brien & Kabanoff, Citation1979), whereas other studies did not mention this longitudinal evolution (Houssemand et al., Citation2019). Moreover, a negative correlation was found between internal locus and direct coping (Petrosky & Birkimer, Citation1991). Thus, the concept of locus of control might represent an important variable in the study of coping with the unemployment process – especially the normalization process – and its emotional consequences.

The present study

Even if some reviews about coping with unemployment have been published (e.g., Waters, Citation2000), its recurrent conclusion is the need for studies analyzing the unemployment coping process (e.g., Kinicki et al., Citation2000; McKee-Ryan et al., Citation2005; Rudisill et al., Citation2010; Waters, Citation2000). More precisely, little is known about the relations between perceived control over the experience of unemployment, unemployed people’s perceptions of unemployment, and their emotions toward this situation. Gaining insights into these matters is important to build knowledge about a potential coping process during unemployment (Thill et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the literature on the detrimental effects of unemployment has tended to focus on the broader impact of unemployment on mental and physical health or life satisfaction and not on the specific emotions that are experienced during this period (McKee-Ryan et al., Citation2005; Paul & Moser, Citation2009; Von Scheve et al., Citation2017). According to Gowan and Gateway (Citation1997), affect plays an important role in the coping process, and different methods of classifying emotions can be found in the literature. Russel (Citation1980) considered pleasantness (positive vs. negative) and arousal (high vs. low) to be the two major dimensions in his model. Later, other scholars (Diener et al., Citation1995, Citation1999) used positive and negative affect to identify the emotional components of subjective well-being. Thus we consider here that unemployment normalization can have an impact on both positive and negative affects (e.g., Diener et al., Citation1995).

This study principally focuses on the emotional elements of the process for coping with unemployment. This mechanism – named here the “emotion dimension”, as already described above – is considered in terms of both: an expected result and effect of the adaptive process engaged in reaction to a period of unemployment; and as a processual element used to safeguard the compulsory psychological balance of the unemployed person placed in this stressful situation.

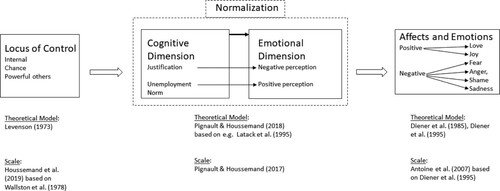

Thus, the main objectives of this study are (a) to confirm the importance of this emotional dimension when individuals normalize their experiences as part of the process of coping with unemployment (i.e., the coping adaptation process uses this emotional dimension and is not a purely cognitive regulation); (b) to verify the effects of coping with unemployment on an individual’s affects and emotions; and, (c) to confirm the effects of locus of control on the coping with unemployment process. Based on different models proposed in the literature (normalization of unemployment, as a coping strategy, with its double cognitive and emotional dimension, positive and negative affects and emotions, locus of control with its three causal attribution factors), empirical data were used to test the heuristic modeling of the process for coping with unemployment. This modeling supposed that types of locus of control affected the cognitive dimension of normalization, linked with the emotional dimension (Houssemand et al., Citation2019; Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017). The cognitive dimension of the normalization process was first part of the coping mechanisms and it subsequently impacted the emotional dimension. This order was retained because “cognitive processes are the primary intervening variables between involuntary job loss and subsequent behavioral outcomes” (Latack et al., Citation1995, p. 320). These processes are: a cognitive appraisal of the situation; cognitive reappraisal by reinterpreting the situation through external justifications or fatalistic explanations, and discrepancy appraisal between the current situation and unemployed person’s expectations (Edwards, Citation1992; Latack, Citation1986; Latack et al., Citation1995); and finally because perceived control has a potential direct impact on these (re)appraisal processes (Bandura, Citation1988; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Thus, the emotional dimension of a coping process then becomes the adaptive response of the cognitive dimension, and this is managed through the regulation of emotions. This latter point could influence personal affects and emotions (Diener et al., Citation1995). Because the structure and some relationships of the three constructs of the model were assessed previously, and because the final goal of the present study was to verify the proposed model of coping with unemployment, a confirmatory approach was used.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants consisted of 260 unemployed people seeking a job in Luxembourg. Participants were 43.15 years old (SD = 10.34) on average; 54.18% were men; 57.4% of the sample was unemployed for the first time; 62.2% were receiving an unemployment subsidy, and 55.7% of these reported that the subsidy was not enough to cover their financial needs.

The study was carried out in Luxembourg between April and July 2018 in collaboration with the public employment service ADEM (Agence pour le développement de l’emploi). It was a part of a broader research program funded by the National Research Fund of Luxembourg (CORE Program: Project UnemployNorm, under grant number C13/SC/5885577) of which ADEM was a partner. The state employment service gave access to its buildings, announced the study to unemployed people (by email, the press and during follow-up meetings with their guidance professionals), and introduced the researchers of the University of Luxembourg to job seekers. The questionnaire was offered in paper form and was anonymous. It was taken when job-seekers came in to ADEM’s offices for their mandatory individual appointments. The participating unemployed people were volunteers, and were given the option to stop the survey at any time. They received no compensation and no individual feedback. Participants were informed of these conditions before filling out the questionnaire. Oral and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Moreover, the Luxembourg Agency for Research Integrity (LARI) specified that according to the Code de Déontologie Médicale (CNR), Chapter 5, Article 77 of which states that the study was not linked to developing biological or medical knowledge, and thus CNR approval was not required.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg provides a specific context that, as identified by Houssemand and Meyers (Citation2011), is a favorable labor market with a low unemployment rate and a generous allowance system for unemployed people. In particular, during the period between April and July 2018, the unemployment rate in Luxembourg was approximately 5.5% (Statec, Citation2019).

Measures

To analyze the associations between locus of control, unemployment normalization, and emotions, and to confirm the proposed model of coping with unemployment, we carried out a transversal study employing three different scales. Additionally, certain characteristics of the participants were recorded: age in years, sex, redundancy of jobless (number of unemployment periods), and existence of social compensation. The questionnaire took approximately 10 min to be completed.

Perceived Control of Unemployment Scale. Unemployment locus of control and perceived control were measured by employing the PCUS (Perceived Control of Unemployment Scale, Houssemand et al., Citation2019). Based on Levenson’s (Citation1973) theory, this 16-item scale distinguishes between three dimensions of control in unemployment and job-seeking situations: internal locus of control (example: If I take care, I can avoid being unemployed again); powerful others (example: Being in regular contact with the administration office is the only way for me to find a job); and chance (possibly divided into two sub-dimensions: fate and luck – example: Most of the things that affect my job search happen by chance). The PCUS was created to respond to a general requirement for more domain-specific assessments of LOC and perceived control (e.g., Spector, Citation1988). It is also useful because assessment of perceived control in unemployment seemed to be a key question in contemporary society, and it helps scientists to better understand the coping process. The scale derived from the A-form of the Multidimensional Locus of Control Health Scales (MLCH; Wallston et al., Citation1978) where the causes of stress were changed from health to unemployment. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absolutely disagree) to 3 (absolutely agree). The scale was previously structurally validated (RMSEA = 0.050, CFI = 0.939, TLI = 0.926), a convergent validity analysis confirmed the links with general perceived control measures, a divergent validity analysis assured the specificity of the scale compared to other measurements of psychological constructs, and a predictive validity analysis concluded that the scale was the best predictor of becoming unemployed in the long term (Houssemand et al., Citation2019).

Unemployment Normalization Questionnaire. Unemployment normalization was assessed with the UNQ (Unemployment Normalization Questionnaire; Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017) characterized by 16 items. The questionnaire was derived essentially from the theoretical model presented by Latack et al. (Citation1995) based on coping theory, control theory, and self-efficacy, and where coping permits the maintenance of psychological equilibrium during a period of unemployment. The structure of the questionnaire was based on an initial study by Pignault and Houssemand (Citation2013), and on a confirmatory replication (Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017) having good adequation fits (RMSEA = 0.045, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.964). Relations between the unemployment normalization dimensions and mental health were found (Thill et al., Citation2018). Based on the nature and the contents of items, the questionnaire could be split into two dimensions, confirmed previously by different factor analyses and structural equations. Coherent with the theoretical model of processes for coping with unemployment was the structure of the normalization scale. Thus, the choice of items (made in order to reproduce the double dimensionality of the coping model and the statistical analyses confirming this structure) make it possible to ensure a plausible construct validity for the questionnaire. This scale described a cognitive dimension which impacts an emotional dimension. This affects in turn the subjective well-being of unemployed respondents. The two first factors are considered to represent the cognitive part of unemployment normalization. The unemployment norm factor consists of three items explaining that unemployment is perceived as a normal stage in one’s career, representing the perception of unemployment as a norm (example: Unemployment is now an inevitable stage in life). External justification of unemployment is also assessed with three items (example: Unemployment is a result of the crisis). These items explain the extent to which people perceive that their unemployment is due to external factors, such as the economic downturn. The cognitive factors have an impact on the two affective factors. Whereas the negative perception of unemployment factor consists of five items and explains the negative consequences of unemployment (example: Since I have been unemployed, I feel different from others), the positive perception of unemployment factor also consists of five items and evaluates the beneficial side of unemployment (example: Since becoming unemployed, I feel better than before). Items are answered on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 4 (totally agree).

Emotional Valence Measure. Emotions were assessed with the French version of the EVM (Emotional Valence Measure; Antoine et al., Citation2007; based on Diener et al., Citation1995). This questionnaire assesses the frequency of 23 emotions from the previous week. The validation of the scale was verified by different exploratory and confirmatory analyses (Antoine et al., Citation2007). Thus, the structure of the scale was confirmed (SRMR = 0.051, GFI = 0,91) and convergent validity assured correlations between positive emotions and life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation1995), and, between negative emotions and psychological distress (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (several times a day). Items can be assembled into six emotions: love, joy, fear, anger, shame, and sadness. These six emotions can be regrouped into positive and negative affect. Positive affect consists of the first two emotions, whereas negative affect is represented by the other ones (as described by Diener et al.’s model, Citation1995).

As the heuristic model of the study was composed of the three previously-established models (locus of control, normalization and emotions), the main statistical analysis consisted of structural equation modeling (confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis). It can be drawn () on the basis of the older models. To verify this model of coping with unemployment, and its influence on emotions and affects, some analyses were computed. In the first section, some descriptive statistical analysis was carried out and the structure of each scale was confirmed and verified using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012). The correlations between the constructs of the study are indicated. In a second section, the heuristic model was assessed using Mplus structural equation modeling. Here the latent constructs where defined by all the items of the corresponding scale (the path analysis was not just a regression analysis based on the computed composite scores). To confirm the mediation of normalization between locus of control and affects and emotions, direct and indirect links of the model where analyzed and compared using the Mplus bootstrapping technique (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012).

Results

Structures of scales and analysis of correlations

In a first step, we observed the internal consistency of each scale (). We noticed that all factors showed high internal consistencies except for two factors of the perceived control in unemployment scale. However, these results were similar and comparable to those from the original study (Houssemand et al., Citation2014, Citation2019). This is even though the databases used were totally independent of each other, as they were developed at different times with different jobseekers. This appears to be able to calculate composite scores for the different factors.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for assessed psychometric variables (N = 260).

To verify the theoretical structure of each scale, confirmatory factor analyses were calculated for each questionnaire used in the study. The main purpose of these calculations was to confirm empirically whether the operationalizations chosen for the psychological constructs of the research reproduced the previous structural results. This approach cannot be understood as an analysis of the validity of the tools, but as a simple preliminary verification of their dimensionality. To determine model fit, we computed the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The results of previous studies were repeated in this study indicating that the empirical data of the present study adequately reproduced the theoretical structures of each scale used: emotions scale (RMSEA = 0.081, CFI = 0.973, TLI = 0.970); locus of control scale (RMSEA = 0.080, CFI = 0.898, TLI = 0.876); normalization scale (RMSEA = 0.070, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.975).

Before running a path analysis, we calculated the correlations between the different psychological constructs. The result of these correlations can be found in .

Table 2. Correlations between the normalization dimensions and psychological variables.

The correlations between the unemployment normalization factors were as expected and confirmed results from previous research. We found a small negative correlation between positive and negative perception of unemployment. External justification of unemployment was positively correlated with negative perception. Unemployment norm was correlated with positive perception of unemployment. The two cognitive factors, unemployment norm and unemployment justification, were also positively correlated with each other.

The correlations between the emotions were as expected. The two positive factors, love and joy, were strongly correlated with each other. The four negative factors, fear, anger, shame, and sadness also showed strong positive correlations amongst themselves. Negative affect and positive affect were not significantly correlated.

The three locus of control factors were moderately and positively intercorrelated. As expected, the correlations were smaller between internal locus of control and both external loci, powerful others and chance, compared with the correlation between the two external factors. The link was higher between these latter loci, which are usually both considered part of an external locus of control (Rotter, Citation1966). Internal locus was not correlated with any of the other constructs. The factor powerful others was positively correlated with three dimensions of the unemployment normalization questionnaire: negative perception, positive perception, and external justification. Furthermore, powerful others was positively correlated with love. The chance factor was correlated with positive perception of unemployment and unemployment norm.

The affective factors of unemployment normalization showed significant correlations with various emotions. Negative perception of unemployment was only correlated with negative emotions and negative affect in general. Positive perception of unemployment showed a negative correlation with negative affect and the different negative emotions, but it was also significantly correlated with joy and positive affect. Finally, for the cognitive factors of unemployment normalization, only external justification showed positive correlations with negative affect and some of the negative emotions (i.e., anger, shame, and sadness). Unemployment norm did not show any significant correlations with emotions.

Path analysis

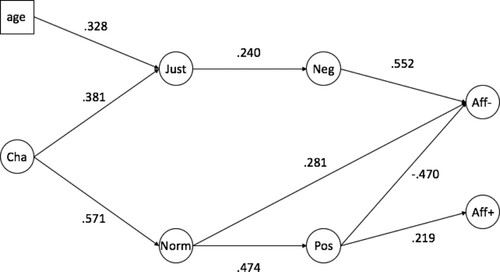

The following models were based on the previous correlations and were calculated with the Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012). The first model showed the results from an SEM analysis at the global level with seven latent factors: Chance from the unemployment locus of control scale (Cha), Unemployment Justification (Just), Negative Perception of Unemployment (Neg), Positive Perception of Unemployment (Pos), Unemployment Norm (Norm), Negative Affect (Aff-), and Positive Affect (Aff+). We present only the statistically significant links between these factors. According to the literature (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2011), the CFI, TLI, and RMSEA from our seven-factor model were very good (CFI = .956, TLI = .953, and RMSEA = .050).

We can see from that the latent factor Chance from the unemployment perceived control scale had a direct positive effect on the two cognitive dimensions of Unemployment Normalization: Justification and Norm. Moreover, Chance from the unemployment locus of control scale also had a positive fully mediated effect on the two affective dimensions of Unemployment Normalization: Negative Perception (via Justification) and Positive Perception (via Norm). With respect to affect, Negative Affect was directly affected in a positive way by Negative Perception and Unemployment Norm. As would be expected, Positive Perception had a direct positive effect on Positive Affect. Furthermore, Positive Perception had a negative effect on Negative Emotions. Finally, age, considered as a covariate, had a positive direct effect on Unemployment Justification. To specify these results, a bootstrapping method was used. This calculates the estimated direct and indirect effects confidence intervals of the model. The direct links between locus and affects possibly seemed not to be significant, neither positively (95% CI = [−0.273, 0.189]) nor negatively (95% CI = [−0.236, 0.275]). Conversely, some indirect effects (locus-normalization-affects) were possibly significant. Thus, the Unemployment Norm and Positive Perception seemed to mediate the effects on positive affects (95% CI = [0.005, 0.132]) and on negative affects (95% CI = [−0.233, −0.030]). The mediated effects of Unemployment Justification and Negative Perception on negative affects revealed possible cases where the link might not be significant (95% CI = [−0.018, 0.118]).

Figure 2. Process of coping with unemployment using Perceived Control, Normalization and Affects.

Note: Cha: Chance (unemployment locus of control scale); Just: Unemployment Justification; Norm: Unemployment Norm; Neg: Negative Perception of Unemployment; Pos: Positive Perception of Unemployment; Aff-: Negative Affect; Pos: Positive Affect.

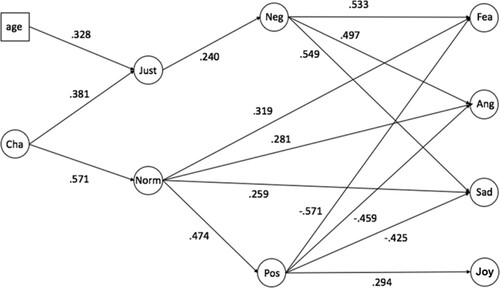

Next, we analyzed a more detailed model which specifies the individual emotional components impacted by the process of normalization of people experiencing unemployment. The aim of this analysis is to check whether emotions are influenced in the same way and globally by this coping process. Thus, the results of this analysis will specify the conclusions of the present study. shows the results from an SEM analysis at the specific level where the global dimensions of Negative and Positive Emotions were disaggregated into their individual components: Joy (Joy), Fear (Fea), Anger (Ang), and Sadness (Sad). Again, this model had a good fit (CFI = .959, TLI = .955, and RMSEA = .051).

Figure 3. Process of coping with unemployment using Perceived Control, Normalization and Emotions.

Note: Cha: Chance (unemployment locus of control scale); Just: Unemployment Justification; Norm: Unemployment Norm; Neg: Negative Perception of Unemployment; Pos: Positive Perception of Unemployment, Fea: Fear; Ang: Anger; Sad: Sadness; Joy: Joy.

shows that the basis of this model was identical to the previous model in . Age showed a positive effect on External Justification. Chance from the External Locus of Control scale showed a positive link with External Justification and Unemployment Norm. These cognitive factors of unemployment normalization positively affected the affective factors of unemployment normalization: positive and negative perception of unemployment. In this model, negative and positive affect had been replaced by the corresponding emotions. Again, Negative Perception of Unemployment had a positive effect on three of the negative emotions (i.e., Fear, Anger, and Sadness), whereas Positive Perception of Unemployment negatively affected these same negative emotions. Moreover, Positive Perception of Unemployment also positively affected Joy. Regarding the relation between Unemployment Norm and emotions, we found that Unemployment Norm had a direct positive effect on Fear, Anger, and Sadness. Finally, we found strong positive correlations between the three negative emotions. Concerning the model verification using the bootstrapping method, and because emotions and affects were totally interdependent, exactly the same results could be seen here as previously observed for affects.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relations between locus of control in the unemployment context, unemployed people’s experience of unemployment, and their emotions felt in this situation.

First, we verified the structural validity of each scale. The adequation fit might seem moderate by normal standards in these kind of analyses (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2011), but these cutoff points are sometimes questioned (e.g., Steiger, Citation2007) and depend on the number of respondents (e.g., Kenny et al., Citation2015). Thus, it can be considered that the empirical data of the study reflected the structures previously assessed.

Then, we calculated the correlations between the different factors. The locus of control factors were intercorrelated as expected. The two external factors showed a higher correlation than the correlations between an external factor and the internal factor (Houssemand et al., Citation2019). Internal locus of control did not show a significant correlation with any other variables. The external locus of control facet powerful others showed positive correlations with both affective factors of unemployment normalization (i.e., positive and negative perceptions of unemployment). Furthermore, powerful others was positively correlated with both external justification of unemployment and love. Chance was positively correlated with both perceived unemployment norm and positive perception of unemployment. The links between the unemployment normalization factors were as expected (Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017). Negative perception was negatively correlated with positive perception. External justification was positively correlated with negative perception, whereas unemployment norm was correlated with positive perception. There was also a correlation between unemployment norm and external justification. Unemployment norm was not significantly correlated with any emotions. However, external justification was positively linked with negative affect and more specifically anger and sadness. This is interesting because Thill et al. (Citation2018) hypothesized that the increase in external justification during a specific phase of unemployment could indicate a state of frustration. Our study confirmed relations between external justification, anger, and sadness. As expected, negative perception of unemployment showed a strong relation with negative emotions and negative affect in general. On the other hand, the positive perception of unemployment was not only positively related to joy and positive affect but also showed negative correlations with negative affect and all of the negative emotions. Finally, the correlations between emotions were also as expected. The negative emotions were strongly intercorrelated, and the relation between joy and love was also strong and positive (Antoine et al., Citation2007; Diener et al., Citation1995).

After the correlations, we focused on two path analyses. First, we investigated the relations between locus of control, unemployment normalization, and the two major affect factors. Our results showed that unemployment normalization acted as a mediator between the personality trait of locus of control and affect. People with high scores on chance had higher external justification scores and higher unemployment norm scores. Age also influenced external justification. The older the unemployed people were, the more they justified their situation as being due to external factors. This might be due to the fact that older people consider their age to be an important factor in their unemployment and also in their inability to find a new job. Meyers and Houssemand (Citation2010) showed that age was an important predictor of long-term unemployment. This point is important and should be analyzed in greater depth in further studies. For example, studies could use multiple-group SEM to verify invariance of the present model of coping with unemployment at different ages or career phases.

The structure of unemployment normalization in the model was as expected: external justification showed a positive effect on negative perception, whereas unemployment norm had a positive effect on positive perception. External justification showed no direct link with any of the emotion factors, only a fully mediated link with negative affect through negative perception of unemployment. However, the unemployment norm showed a direct positive effect on negative affect. This means that the perception of unemployment as a norm evoked more negative emotions. Here, the only link between unemployment norm and positive affect was through positive perception of unemployment. However, not only did positive perception have a positive influence on positive affect, but it also had a negative influence on negative affect. This means that people who perceive unemployment as a positive situation tend to experience more positive emotion and less negative emotion. The results could be discussed in the light of the analyses of direct against indirect links between locus of control and affects. This could be done through a mediation of normalization process. Considering the conclusions of bootstrapping analyses, the mediation of normalization process on negative affects (driven by Unemployment Justification and Negative Perception) could have no significance in the population of unemployed people. This conclusion would confirm the main impact of Unemployment Norm and Positive Perception, both for the positive and negative affects. In that way, these results downplay the normalization effects during unemployment. However at the same time it increased the importance of positive perception of unemployment, and that this moderates the strength of emotions. Because this stochastic method of resampling uses the same initial data, these conclusions, like the others, will have to be confirmed with other heterogeneous and larger samples of unemployed people.

The second model between locus of control, unemployment normalization, and four emotions showed similar results. The basis of the model was identical to the first model. Again, chance had an influence on the two cognitive factors of unemployment normalization: external justification and unemployment norm. Age had an influence only on external justification. The important part of this second model lay in the relations between unemployment normalization and four specific emotions: fear, anger, sadness, and joy. Results again revealed a positive link between unemployment norm and the three negative emotions. This means that the people who perceived unemployment as a normal stage in a career experience more fear, anger, and sadness during this situation. Negative perception also showed a positive link with these negative emotions. However, positive perception showed a positive relation with joy but a negative relation with the three negative emotions: fear, anger, and sadness. These results were similar to the previous model but showed the relations with specific emotions in more detail.

The main findings from this study illustrate that the negative perception of unemployment tends to heighten negative emotions and negative affect in general. This means that people who perceive unemployment as a negative event in life also feel more negative emotion. However, negative perception did not dampen the positive emotions, and thus, it was not the opposite of positive perception of unemployment. Not only did positive perception of unemployment have a positive effect on the positive emotions but it also had a negative effect on the negative emotions. This is an indication of the beneficial effect of positive perception during unemployment (Thill et al., Citation2018). This means that the positive perception of unemployment not only enhanced positive affect, love, and joy, but it also reduced negative affect and more specifically fear, anger, and sadness. This result illustrates that the positive perception of unemployment could be considered a form of emotion regulation during unemployment. Pignault and Houssemand (Citation2017) viewed unemployment normalization as a strategy that involves cognitive (re)appraisal. This idea is in line with Gruber et al. (Citation2014), who hypothesized that reappraisal can be done to decrease negative emotions and to increase positive emotions.

Contrary to what has been suggested by previous studies (Pignault & Houssemand, Citation2017, Citation2018; Thill et al., Citation2018), our findings imply that the unemployment norm did not shield unemployed people from experiencing negative emotions. However, unemployment is a complex experience as shown in the studies by Borgen and Amundson (Citation1987). More specifically, a recent study on unemployment normalization demonstrated that the unemployment norm had a buffering effect only in a group of people who had been unemployed for a long time (Thill et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, results of the social norm toward work have unveiled different results (Clark, Citation2003; Stam et al., Citation2015). This could also be the case for the unemployment norm. Latack et al. (Citation1995) also explained that a coping strategy could have a beneficial impact in one stage and a detrimental one in another stage of the coping process. Further investigations into this matter would therefore be profitable.

Finally, the results of the present study are part of a stream of research analyzing the links between health and reemployment. For example, Vinokur and Schul (Citation2002) showed that an individual’s propensity to be reemployed depends above all on the coping strategies that they may or may not implement during a period of unemployment. Unemployment normalization – a strategy that preserves the resources needed to implement measures and promotes reemployment – is shown to be an interesting strategy. As described in the Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation2002), people preserve their health and keep energy and means available, which in our context here relates to job seeking or even career development. Thus, because the normalization process could tend to decrease negative emotions and increase positive emotions, especially if the importance of its positive perception is confirmed, it could be a perfect driver for maintaining emotional equilibrium and well-being. Career counselors should take this dimension into account and help the unemployed people they advise to be more aware of the experience they are living and the emotions they feel and get people to see this transition as an opportunity to rethink their career and the meaning of work. The current global Coronavirus crisis is already having a major impact on employment worldwide and, while the catastrophic effects of these job losses on people should not be denied, it is perhaps more useful than ever to participate in new ways of experiencing (non) work and job searching.

Conclusion

The present study had as a main objective to suggest normalization as a process for coping with periods of unemployment. It is composed of one cognitive dimension that provides a reappraisal of the situation, and of one emotional adaption. Thus, normalization enables individuals to reach a psychological re-equilibrium during stressful periods of unemployment. Previous studies have indicated that locus of control had an impact on normalization, and that coping with unemployment processes affected well-being and affects. Based on that, we computed a heuristic model of coping with unemployment, where normalization mediated effects of locus of control on affects and emotions. Using confirmatory analyses, the model of this process is confirmed empirically. Thus, this study increased knowledge about coping with unemployment processes. It did this by confirming the importance of emotions during the coping with unemployment process. This was achieved by verifying the effects of coping with unemployment with individual affects and emotional feelings, and by ascertaining the moderation of coping process by locus of control. So it constitutes a certain theory-driven contribution or, at least a continuation for the better understanding of the individual's perception of unemployment, as well as reactions of how to overcome it psychologically. Moreover, some practical implications could be drawn from these conclusions. As already pointed out by Gowan and Gateway (Citation1997), stress must be seen as being central to understanding individual reactions to unemployment (Leana & Feldman, Citation1990). Thus, understanding coping mechanisms can help those in charge of setting up programs to help the unemployed, in particular by highlighting the relevant elements which contribute towards a better and more profitable adaptation to the situation. More specifically, in the current context of the health crisis, many jobs are at risk and the unemployment rate is likely to rise further in many countries. In Europe, public employment administrations are currently recruiting thousands of counselors to help and support new jobseekers. In line with adaptive counseling theory (Bernaud, Citation2013; Guénolé et al., Citation2015) – which highlights the relevance of taking into account the specific characteristics and preferences of each individual – better understanding of coping processes and emotion regulation during periods of unemployment is significant information which can serve to increase effectiveness of counseling strategies. In particular, this could help career advisors to give more informed advice in terms of stress management and helping unemployed people better understand their situation. This could help improve the overall effectiveness of counseling. These perspectives have already been highlighted by various authors (e.g., Gowan & Gateway, Citation1997; Latack et al., Citation1995) who advocated a more differential approach to helping the unemployed. This is because the same conditions would not be active while the same coping processes are being deployed. They would certainly not have the same effects in terms of mental health, the ability to job seek and ultimately to find reemployment.

Limitations and future research

We conclude by discussing some limitations of our study as well as possible avenues for further research. A first limitation of our study is its limited sample size. Therefore, it will be important to replicate the present study on a larger scale in order to verify the main findings. It would also be interesting to conduct a longitudinal study with short time intervals between questionnaires to determine whether Unemployment Normalization and Emotions change within the same day. Future research would profit from a longitudinal setting, which can show the different phases of emotions the unemployed go through (Amundson & Borgen, Citation1982) with respect to the unemployment normalization process (Thill et al., Citation2018).

Next, it is important to remember that each unemployed person has different experiences with unemployment because unemployment is a multidimensional concept that is influenced by many variables (Borgen & Amundson, Citation1987). Hence, a possible extension would be to study the relations between Emotions, Unemployment Normalization, and other personality traits besides Locus of Control. Similarly, another possible extension would be to look at the role of other emotions besides the ones considered in this study.

An additional potential limitation of our study is that it was carried out in the ADEM’s offices; therefore, participants could have been affected by a social desirability bias and might not have felt completely free to answer the survey honestly. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the ways unemployed people justify their situation vary according to the unemployment rate and economic history of their country (Houssemand & Pignault, Citation2017). Hence, our results should be interpreted within the context of The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, where the labor market is particularly favorable (Houssemand & Meyers, Citation2011). Therefore, another interesting direction for future research would be to replicate the current study in different social contexts.

Acknowledgements

We thank Agence pour le développement de l’emploi (ADEM Luxembourg) and Pôle emploi (France) for their assistance with this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amundson, N. E., & Borgen, W. A. (1982). The dynamics of unemployment: Job loss and job search. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60(9), 562–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1982.tb00723.x

- Antoine, P., Poinsot, R., & Congard, A. (2007). Évaluer le bien-être subjectif: La place des émotions dans les psychothérapies positives [Measuring subjective well-being: Place of the emotions in positive psychotherapies]. Journal de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive, 17(4), 170–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1155-1704(07)78392-1

- Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (2002). Normalizing emotion in organizations: Making the extraordinary seem ordinary. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-4822(02)00047-5

- Bandura, A. (1988). Self-conception of anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10615808808248222

- Bernaud, J.-L. (2013). Adaptive counseling theory: A new perspective for career counseling. In A. Di Fabio (Ed.), Psychology of counseling (pp. 171–183). Nova Science Publishers.

- Borgen, W. A., & Amundson, N. E. (1987). The dynamics of unemployment. Journal of Counseling & Development, 66(4), 180–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1987.tb00841.x

- Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/345560

- DeFrank, R. S., & Ivancevich, J. M. (1986). Job loss: An individual level review and model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(86)90035-7

- Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.130

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.125.2.276

- Edwards, J. R. (1992). A cybernetic theory of stress, coping, and well-being in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/258772

- Eisenberg, P., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1938). The psychological effects of unemployment. Psychological Bulletin, 35(6), 358–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063426

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161320

- Gowan, M. A., & Gateway, R. D. (1997). A model of response to the stress of involuntary job loss. Human Resource Management Review, 7(3), 277–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(97)90009-7

- Gruber, J., Hay, A. C., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Rethinking emotion: Cognitive reappraisal is an effective positive and negative emotion regulation strategy in bipolar disorder. Emotion, 14(2), 388–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035249

- Guénolé, N., Bernaud, J.-L., Desrumaux, P., & Di Fabio, A. (2015). Approche individualisée ou standardisée de l’accompagnement des demandeurs d’emploi: Une recherche inspirée de la théorie du conseil adaptatif. Pratiques Psychologiques, 21(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prps.2015.03.003

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

- Houssemand, C., & Meyers, R. (2011). Unemployment and mental health in a favorable labor market. International Journal of Psychology, 46(5), 377–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.554552

- Houssemand, C., Meyers, R., & Pignault, A. (2019). Adaptation and validation of the perceived control in unemployment scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00383

- Houssemand, C., & Pignault, A. (2017). Unemployment normalization in different economic contexts. In Y. Liu (Ed.), Unemployment - perspectives and solutions (pp. 37–51). InTech. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.69817

- Houssemand, C., Pignault, A., & Meyers, R. (2014). A psychological typology of newly unemployed people for profiling and counselling. Current Psychology, 33(3), 301–320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9214-9

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- International Labour Organisation. (2000). Yearbook of Labour statistics (58th issue). International Labour Office.

- Jahoda, M. (1983). Wieviel Arbeit braucht der Mensch? Arbeit und Arbeitslosigkeit im 20. Jahrhundert [How much work does man need? Employment and unemployment in the 20th century]. Beltz.

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods and Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

- Kinicki, A. J., Prussia, G., & McKee-Ryan, F. (2000). A panel study of coping with involuntary job loss. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1556388

- Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Latack, J. C. (1986). Coping with job stress: Measures and future directions for scale development. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 377–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.377

- Latack, J. C., Kiniki, A. J., & Prussia, G. E. (1995). An integrative process model of coping with job loss. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 311–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9507312921

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Leana, C. R., & Feldman, D. C. (1988). Individual responses to job loss: Perceptions, reactions, and coping behaviors. Journal of Management, 14(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400302

- Leana, C. R., & Feldman, D. C. (1990). Individual responses to job loss: Empirical findings from two field studies. Human Relations, 43(11), 1155–1181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679004301107

- Levenson, H. (1973). Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41(3), 397–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035357

- Levenson, H. (1974). Activism and powerful others: Distinctions within the concept of internal-external control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 38(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1974.10119988

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- Meyers, R., & Houssemand, C. (2010). Socioprofessional and psychological variables that predict job finding. European Review of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2009.11.004

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th Ed). Muthén & Muthén.

- O'Brien, G. E., & Kabanoff, B. (1979). Comparison of unemployed and employed workers on work values, locus of control and health variables. Australian Psychologist, 14(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067908260434

- Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2006). Incongruence as an explanation for the negative mental health effects of unemployment: Meta-analytic evidence. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(4), 595–621. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905 ( 70823

- Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001

- Petrosky, M. J., & Birkimer, J. C. (1991). The relationship among locus of control, coping styles, and psychological symptom reporting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(3), 336–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199105)47:3<336::aid-jclp2270470303>3.0.co;2-l

- Pignault, A. (2011). Chômage et stratégies d’adaptation des personnes face à cette situation. In P. Desrumaux, A.-M. Vonthron & S. Pohl (Eds.), Qualité de vie, risques et santé au travail (pp. 226–237). L’Harmattan, Collection psychologie du travail et ressources humaines.

- Pignault, A., & Houssemand, C. (2013). Le chômage : une situation « normalisée »? Etude menée auprès de demandeurs d’emploi séniors. In M. E. Bobillier Chaumon, M. Dubois, J. Vacherand-Revel, P. Sarnin, & R. Kouabenan (Eds.), La question de la gestion des parcours professionnels en psychologie du travail (pp. 101–115). L’Harmattan.

- Pignault, A., & Houssemand, C. (2017). Normalizing unemployment: A New Way to cope with unemployment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 372–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1373646

- Pignault, A., & Houssemand, C. (2018). An alternative relationship to unemployment: Conceptualizing unemployment normalization. Review of General Psychology, 22(3), 355–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000148

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

- Rudisill, J. R., Edwards, J. M., Hershberger, P. J., Jadwin, J. E., & McKee, J. M. (2010). Coping with job transition over the work life. In T. W. Miller (Ed.), Handbook of stressful transition across the lifespan (pp. 111–131). Springer.

- Russel, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

- Schaufeli, W. B., & VanYperen, N. W. (1992). Unemployment and psychological distress among graduates: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65(4), 291–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1992.tb00506.x

- Silla, I., De Cuyper, N., Gracia, F. J., Peiró, J. M., & De Witte, H. (2009). Job insecurity and well-being: Moderation by employability. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 739–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9119-0

- Spector, P. E. (1988). Development of the work locus of control scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61(4), 335–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1988.tb00470.x

- Stam, K., Sieben, I., Verbakel, E., & de Graaf, P. M. (2015). Employment status and subjective well- being: The role of the social norm to work. Work, Employment and Society, 30(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014564602

- Statec. (2019). The rate of unemployment in Luxembourg from May 2017 to May 2019. http://www.statista.com/statistics/603725/unemployment-rate-in-luxembourg/.

- Steiger, J. H. (2007). Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 893–898. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.017

- Thill, S., Houssemand, C., & Pignault, A. (2018). Unemployment normalization: Its effect on mental health during various stages of unemployment. Psychological Reports, 122(5), 1600–1617. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118794410

- Vinokur, A. D., & Schul, Y. (2002). The web of coping resources and pathways to reemployment following a job loss. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.7.1.68

- Von Scheve, C., Esche, F., & Schupp, J. (2017). The emotional timeline of unemployment: Anticipation, reaction, and adaptation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(4), 1231–1254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9773-6

- Wallston, K. A., Wallston, B. S., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MDHL) scales. Health Education Monographs, 6(1), 160–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817800600107

- Wanberg, C. R. (1997). Antecedents and outcomes of coping behaviors among unemployed and reemployed individuals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 731–744. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.82.5.731

- Waters, L. E. (2000). Coping with unemployment: A literature review and presentation of a new model. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00036