ABSTRACT

The combination of a global pandemic and an ignited social justice movement created a digital environment in which people turned to social media to navigate a concentric firestorm fueled by both the Black Lives Matter movement and the COVID-19 pandemic. Through interviews with 25 supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement, we used the circuit of culture to build theory about the production and consumption of messages. Specifically, we examined the ways in which meaning was produced, interpreted, and contested in the context of a social movement occurring inside of a global pandemic. We engaged in theoretical bricolage by demonstrating how perspective by incongruity, appropriation, and the referent criterion can shape meaning within the context of the circuit of culture. This study concludes with a foundational conceptualization of concentric firestorms, and we relate this conceptualization to two concepts we propose based on our data: virtual density and virtual saturation.

In March 2020, many states ordered nonessential businesses to be closed while academic instruction and work moved online as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Just two months later, people took to the streets to protest police brutality in the name of George Floyd, a Black man from Minneapolis who was killed when a police officer knelt on his neck (Hill et al., Citation2020). In his final moments, he uttered “I can’t breathe” more than 20 times, and this utterance became one of the slogans of the Black Lives Matter movement (Oppel & Barker, Citation2020). Since Floyd’s death, the Black Lives Matter movement has been amplified to demand justice for many other Black people that were killed (Burch et al., Citation2021). This event occurred in an ongoing crisis of police brutality, and it coincided with a health crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic catalyzed a high volume of social media messages, reflecting clashes in views about topics such as mandatory mask-wearing, restaurant shut-downs, online education in schools, and questions regarding mandates for an eventual vaccine.

Both the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the death of George Floyd sparked a cultural shift. The confluence of two historical events, one rooted in a health crisis and the other in a social justice movement, not only shaped offline behavior but also resulted in an online firestorm. An online firestorm refers to an environment characterized by the rapid spread of intense, negative emotions and messages through social media, set into motion by an event, such as a crisis (Pfeffer et al., Citation2014). Although negative attention from firestorms is an especially notable source of concern for celebrities, brands, and politicians, online firestorms can catalyze social change (Johnen et al., Citation2018; Pfeffer et al., Citation2014).

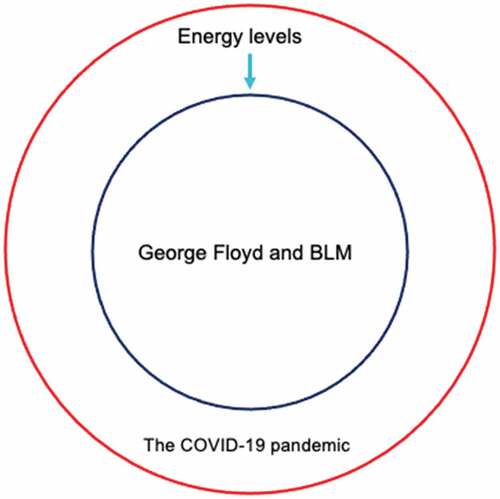

Traditionally, scholars focus on how the meaning of a single phenomenon is reinforced, resisted, and shaped through culture (e.g., Ciszek, Citation2016; Madden et al., Citation2016; Vardeman & Sebesta, Citation2020). This study is the first of its kind to examine a social movement inside of a global pandemic and to examine the crosswinds between two global phenomena that produced high levels of in-person and digital activism. Specifically, we examined how people engaged with the Black Lives Matter movement online and how COVID-19 affected that engagement in various ways. A concentric firestorm is arguably more explosive than either of the single firestorms would be on their own due to the added complexity and volume, and it is an important context for analyzing people’s online construction of identity and activism. This study introduces the term concentric firestorm to describe an environment in which negative emotion and negative messages abound about two firestorms–-one of which shapes the context of the other.

This study advances the public relations literature by proposing a conceptualization for concentric firestorms. Within this conceptualization, we depict the uneven impact the outer ring (in this case, the pandemic environment) can have on the inner ring (in this case, fueling or depleting individuals’ energy for generating activist content, participating in offline activism, and donating to the social movement). On a related note, we identify and problematize compelled speech in the context of the “silence is violence” slogan. In addition, we propose that the constraints imposed by the outer ring of some online firestorms will disproportionately affect people’s lived experiences, providing opportunities to expose injustices. The disproportionate impact of online education on learning loss among students of color during the pandemic is just one of many examples in the current context (Simon, Citation2021).

This study moves the literature forward in additional ways. We tentatively propose that the outer ring in any context will impose barriers of some kind to activities occurring in the inner ring – in the case we examined, image sharing of protesting crowds on social media was socially discouraged by outer ring mandates of social distancing. We also address the potential for the appropriation of highly charged slogans between the outer and inner rings of a firestorm (in this case, “I can’t breathe” between the Black Lives Matter movement and some members of the anti-mask community), and we present related moral guidelines for appropriation in the context of activism. Furthermore, we relate our conceptualization of concentric firestorms to two concepts we propose based on our data: virtual density and virtual saturation. In addition to conceptualizing these terms at the end of the study, we relate these concepts to coinciding features that we believe are likely to occur in the context of a social movement. Data collection consisted of in-depth interviews with 25 participants who identify as supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement. They shared their insights about how the pandemic has shaped their individual experiences and the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole.

Literature review

This section begins by addressing the sidelined role of activist scholarship in early public relations research and its subsequent growth. Next, the impact of social media on activist public relations is discussed to provide theoretical scaffolding for this study, which is situated in a context in which social media could play a heightened role in connecting people during a time of social distancing. Finally, the circuit of culture is presented to study the creation, absorption, and shaping of meaning online. Within this discussion, this study contributes to descriptions of the circuit of culture in the public relations literature by integrating rhetorical literature about meaning-making and by incorporating the role of the referent criterion from the situational theory of problem-solving (Jiang et al., Citation2019; Kim & Grunig, Citation2011, Citation2021).

Foundational activism PR literature

In Karlberg (Citation1996) published an article objecting to the focus of public relations scholarship on the advancement of corporate interests, and he called for scholarship from the vantage point of activists. Although valuable research from an activist standpoint existed at the time (e.g., Grunig, Citation1989; J. E. Grunig & Ipes, Citation1983; L. A. Grunig, Citation1989), most research either positioned activists as generating a turbulent environment requiring a company’s response or generalized research findings to any context, including activist organizations (Holtzhausen, Citation2007). Scholars continued to advance and expand upon Karlberg’s (Citation1996) arguments (e.g., Dozier & Lauzen, Citation2000; Reber & J. K. Kim, Citation2006; M. F. Smith & Ferguson, Citation2010; Taylor et al., Citation2001). A growing tide of activist-centered scholarship followed, which examined activist public relations through various theories such as dialogic theory (e.g., Bortree & Seltzer, Citation2009; Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018; Theunissen & Noordin, Citation2012), relationship management (e.g., Briones et al., Citation2011; Gallicano, Citation2009; Waters, Citation2009), and situational crisis communication theory (e.g., Sisco et al., Citation2010; Sisco, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). In addition, scholars have advanced theory building in areas that focus on social change rather than economic success, including rhetorical studies (e.g., Heath, Citation2000; Reber & Berger, 2005; Stokes & Atkins-Sayre, Citation2018); postmodern studies about valuing dissensus (e.g., Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018; Ciszek, Citation2016; Holtzhausen, Citation2000; Toth, Citation2002); and studies illuminating how meaning is created, consumed, interpreted, and regulated through the circuit of culture (e.g., Curtin & Gaither, Citation2006; Curtin, Citation2016; Quichoco & St. John, Citation2022; Tombleson & Wolf, Citation2017).

The present study is situated within the framework of the circuit of culture, specifically examining the Black Lives Matter movement. As such, our work produces race-related insights and can also be considered as a contribution to diversity research in public relations. As characterized by Mundy (Citation2019), diversity research in public relations tends to focus on female access to top management levels and equal pay, in addition to the representation of racial and ethnic minorities at every level of public relations. Thus, this study is also valuable in its contribution to a growing amount of social movement research pertaining to diversity issues (e.g., Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018; Edrington & Lee, Citation2018; Hon, Citation2015, Citation2016; Mundy, Citation2013; Ni et al., Citation2022; Vardeman & Sebesta, Citation2020).

Social media activism

Hon’s (Citation2015) study of the Justice for Trayvon Martin campaign integrates lessons about digital advocacy from a public relations perspective. She emphasized the importance of costs in activism and outlined the ways in which technology alleviates these costs. According to Hon, digital media “reduce or perhaps even eliminate the need for central organizational leadership” and allow for quick, low-commitment “flash activism,” although these benefits vary depending on how extensively the technology is utilized (p. 300). In these ways, digital media help to offset the advantages by big government and powerful companies that were problematized by scholars such as Karlberg’s (Citation1996) and Dozier and Lauzen (Citation2000).

Specifically, Hon’s (Citation2015) questioned whether big government and powerful corporations could ignore publics who can now turn to social media to raise awareness. She also expressed agreement for Grunig’s and Grunig (Citation1997) argument that a deep-seated personal motivation helps activists command power. As described in critical scholarship, employees are generally loyal to their employers, whereas members of an activist organization tend to be more loyal to the social movement than the organization itself (Dozier & Lauzen, Citation2000). Personal dedication, when combined with the resources of digital media, helps activist groups become more formidable opponents in a public relations space than they might otherwise be (Hon, Citation2015). However, just as activist organizations must focus on generating and maintaining energy for their efforts as a central goal (Gallicano, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2005), individuals must do so, as well, if they want to help sustain an online firestorm. Reasons for investing less energy in a social movement can be external to the movement (e.g., competing needs, Capner & Caltabiano, Citation1993; Nepstad, Citation2004) or internal to it (e.g., conflict among like-minded contributors, Gallicano, Citation2013; Ilsley, Citation1990; Vardeman & Sebesta, Citation2020). We are interested in exploring our participants’ insights about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their energy for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Public relations scholars are engaging in theory building in the area of digital social advocacy in various activist contexts, such as animal rights (Stokes & Atkins-Sayre, Citation2018), social justice (Bonilla & Rosa, Citation2015; Hon, Citation2015), and corporate political advocacy (Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018). In the context of the Black Lives Matter movement, scholars have examined activist organizations’ supportive efforts (Edrington & Lee, Citation2018; Gallicano et al., Citation2017), corporate social advocacy for the cause (Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018; Heatherly et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2020; Waymer & Logan, Citation2021), and uncoordinated participation in a social movement online (Gallicano et al., Citation2020; Hon, Citation2015). Of these three vantage points of supportive companies, activist organizations, and individual activists, the present study falls into the third category by examining the viewpoints of individual social media users who support the Black Lives Matter movement.

Qualitative studies of individual activists’ social media use in public relations are rare, and a variety of methods are needed to uncover different kinds of insights about activist public relations (Ciszek, Citation2019; Smith & Ferguson, Citation2010). Whereas quantitative and qualitative content analysis studies are valuable for focusing on activists’ messages (e.g., Hon, Citation2015), these studies are not able to rigorously delve into the reasons people share for how they act on social media, as well as how their social media behavior relates to their activism in other areas of life, such as protest participation. The closest qualitative study to our work is arguably Smith’s et al. (Citation2019) examination of 12 individuals who participated in the Taksim Square protests via social media. They concluded that an individual’s sense of communicative competence (i.e., the ability to communicate effectively; Hymes, Citation1972), empowerment (i.e., a sense of power and importance in speaking out; Chon & Park, Citation2020; Kang, Citation2014; also see related research on self-efficacy on social media, Chon & Park, Citation2020), and social stake (i.e., responsibility to support one another) influence their social media activities. In turn, engagement attributes––particularly sense of identity and challenge––influence their social media activities. All of these characteristics appear to lead to a person’s level of participation in a social movement.

Circuit of culture

The circuit of culture is a practical matrix that is situated in Curtin and Gaither’s (Citation2007) cultural-economic model of public relations. The model enables researchers to focus on understanding public relations as a “signifying practice that produces meaning within a cultural economy, privileging identity, difference, and power because of the central role these constructs play in discursive practice” (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2007, p. 110). The circuit of culture is one of many frameworks a researcher can apply to produce insights about public relations practices. Several public relations studies have used the circuit of culture (du Gay et al., Citation1997) to capture how meaning is constructed, shaped, and interpreted (Al-Kandari & Gaither, Citation2011; Ciszek, Citation2015; Curtin & Gaither, Citation2006; Curtin, Citation2016; Han & Zhang, Citation2009; QQuichoco & St. John, Citation2022; Schoenberger-Orgad, Citation2011; Terry, Citation2005; Toledano & McKie, Citation2007).

The circuit of culture is an ideal framework for our study because researchers can use it to study postmodern, asynchronous approaches to activism that involve struggles for identity making and cultural change (see Al-Kandari & Gaither, Citation2011; Ciszek, Citation2015). As noted by Gaither and Curtin (Citation2008), “The model makes culture the currency of this information age” (p. 119). In addition, the model acknowledges structural limitations based on factors such as economics and social norms while recognizing individual empowerment to engage in dominant and resistant meaning-making (Ciszek, Citation2015).

Through the circuit of culture, public relations is viewed as a practice that creates “meaning about cultural artifacts, artists, and audiences across … five ‘moments’ of the circuit of culture,” which include production, consumption, identity, representation, and regulation (Edwards, Citation2013, p. 243). Each moment provides analysts with a lens for examining how culture circulates through society. The combined moments produce meaning; however, each moment can be examined individually (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2007). The overlap of the moments, which are called articulations, represent areas where the moments mutually shape one another, which can be a useful focus for studying influence (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2005). As noted by Gaither and Curtin (Citation2008), holistically examining the interaction among components shows the mutual influence of each component, demonstrating that meaning is never static. Production and consumption are intertwined as facets of encoding and decoding meaning, while representation, identity, and regulation all involve legal or social constraints in how meaning is portrayed and compared. Each moment is examined in further detail below.

Two components of the circuit of culture that are intertwined in the circulation of meaning include production and consumption (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2005). Production refers to creating and encoding objects with meaning. It includes the creation of cultural discourses, as well as the technical and logistical challenges that shape the formation of them (Ciszek, Citation2015). Any public relations study contributing to knowledge about message production and message strategies is relevant to theory building in this area of the circuit. For example, Curtin’s (Citation2016) study of two Girl Scouts’ quest to end the use of palm oil in Girl Scout cookies yielded the following insights about production: Individuals can partner with activist organizations to bridge resource gaps, they can use compelling storytelling frames, such as casting the hero as an underdog against formidable foes; and they can ignore elements of a political reality that would disrupt the story frame. In this case, the two scouts ignored the issue of child labor in cultivating palm oil – even though it could have been used to advance the scouts’ advocacy – in favor of a feel-good story of their fight against the Goliath of the Girl Scouts organization to save a furry animal, which was cuter than the animal most threatened––not that any species was threatened by the palm oil impact of Girl Scout cookies.

Another example is Quichoco and St. John’s (Citation2022) study of the gas and oil industry campaign in Colorado to defeat a measure that would require any fracking from being within 2,500 feet of a structure intended for human occupancy. They proposed the narrative paradigm Nexus model as a development of the circuit of culture. The narrative paradigm Nexus model encompasses three production strategies that also pertain to the moments of identity and representation. The first production strategy is called values, which refers to the display of audience values in the campaign messages and the linkage of audience values to the proposed political measure, which relates to underlying public relations scholarship about shared values in campaign rhetoric (e.g., Heath, Citation2006) and rhetorical scholarship regarding identification and consubstantiality (Burke, Citation1950). A second production strategy in the narrative paradigm Nexus model is called aesthetics, which refers to the use of images in a way that supports the proponent’s story (i.e., narrative probability; Fisher, Citation1978, Citation1984, Citation1985, Citation1987) while conveying an unfiltered reality (i.e., narrative fidelity; Fisher, Citation1987). The final component of the model is resonance, which can be used in a message to represent the audience’s lived experience and encourage the audience to make meaning of their past lived experience in way that drives them toward choosing actions for how they want to live now, which are aligned with the campaign’s purpose.

Any insights from studies about the production of message strategies apply to the moment of production, regardless of whether they originate in the public relations literature. For example, Klumpp’s (Citation1973) study of the Columbia University student protest of 1968 has a relevant insight for activists in the moment of production: To gain support for a cause, activists can attempt to remove a middle ground position through their rhetoric to compel their audiences to either join the movement or be considered as opponents to it. This strategy can be seen in the polarizing slogan from the Black Lives Matter movement: “Silence is violence.” In essence, this slogan creates a reality in which people who do not speak out for the movement are interpreted as committing violence.

Consumption is the act of interpretation; it completes production through the decoding of meaning. One personal characteristic that could affect consumption is the referent criterion from the situational theory of problem solving (see Jiang et al., Citation2019; Kim & Grunig, Citation2011, Citation2021). Kim and Grunig (Citation2011) explained that the referent criterion consists of a person’s previous knowledge or prior way of making assessments from related situations. It can almost be thought of as the consumption equivalent to Quichoco and St. John’s (Citation2022) concept of resonance in the sense that people will look to their previous decision-making and consequences when determining their actions in the present; however, there does not need to be a producer’s campaign goals involved for the referent criterion to be used by an individual, which is just a matter of the referent criterion having a broader context in the moment of consumption than resonance has in the moment of production. The present study is among the first of its kind to seek evidence of the referent criterion in the moment of consumption.

Another consideration for consumption in the context of our study is the role of the environment on the consumption of messages. Huang et al. (Citation2021) studied a Chinese company’s social media use during the pandemic and concluded that the company’s messages about the pandemic predicted publics’ emotional engagement better than its non-pandemic messages involving relationship cultivation strategies. Specifically, the company’s messages involving invitations to help, raise awareness, convey emotions, share stories, and reveal personal experiences were more likely than non-pandemic messages in fostering positive emotions (Huang et al., Citation2021). Their study suggests the powerful role of an environment in shaping message consumption – an important theme that is underscored by our study of the pandemic’s role on the circulation of Black Lives Matter messages.

Identity is another part of the circuit of culture. Shaped by the other four moments, identity becomes an ongoing process of cultural descriptions that include race, gender, age, and other categories (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2005). Rather than treating these identity markers and other aspects of identity as essentialist categories, researchers using the circuit of culture view identity as “a kinetic site for social and political action” (Ciszek, Citation2015, p. 452). Identity is both an internal and external factor that affects or constrains how people interpret and create meaning (Curtin & Gaither,). Many socially constructed meanings circulate about identity. When focusing on this moment, researchers could consider information that is shared about the nature of having particular identities, such as what it means to be Black in the context that is studied. Inequities in the distribution of burdens can also be seen through the lens of identity. For example, in the context of the WHO’s smallpox eradication campaign, Curtin and Gaither (Citation2006) noted that a focus on identity in the circuit of culture enabled a view of “the North from the South, the developed nations from the developing nations, the rich from the poor, the colonizers from the colonized, science from religion” based on smallpox incidences (p. 82).

Representation refers to how meaning is shaped by situational and cultural contexts. Meaning often results from comparison through understanding a phenomenon based on what it is not (Burke, Citation1954; du Gay et al., Citation1997). In the rhetorical literature, a common approach to deriving meaning is described by Burke’s (Citation1954) perspective by incongruity, which refers to insight based on what something is not. For example, the difference in how Black and White men were treated in the context of the Vietnam War resulted in a perspective by incongruity. Black men were drafted at a higher rate than White men and were more likely to serve on front lines (Harrison, Citation1996; Lucks, Citation2014). Considering these separate yet related actions––the government’s concern for Black people in the context of the civil rights movement while giving preferential treatment to White people in the Vietnam War––results in a perspective by incongruity. Perspective of incongruity is included in this study as a form of representation that intersects with the other moments from the circuit of culture.

Another form of representation that is important to this study is appropriation, which occurs when an object’s original message is reshaped in a different context. A prominent form of appropriation in activism is the phrase “All Lives Matter,” which is an oppositional rebuttal to the “Black Lives Matter” slogan (Yancy and Butler, Citation2015). Appropriation aligns easily with representation and has manifestations in the other moments from the circuit of culture. Maiorescu-Murphy (Citation2021) studied cultural appropriation in her study of Christian Dior’s Sauvage perfume. She noted that the controversial appropriation of a slur against Native Americans had the consequences of publicizing the perfume and portraying the company as engaging in exploitation for profit. The company’s retraction of the ad for the perfume in the absence of renaming or removing the product itself was problematic, and moral outrage was heightened due to the preventable nature of the crisis. The company attempted to blunt the criticism by explaining the moral process it used of relying on Native American consultants and experts. Prior to Maiorescu-Murphy’s study, cultural appropriation had “remained unexplored” in public relations research, and additional research is needed about the ethics of appropriation (p. 1).

An additional moment in the circuit of culture is the moment of regulation, which encompasses the formal and informal controls on how meaning is shaped and transmitted (Curtin & Gaither, Citation2005). Formal controls include legal and institutional efforts and policies. Examples falling into this category include government rules pertaining to protests during a time of social distancing, social media algorithms that determine which content is served to people, and an employer’s or an industry’s social justice plan. Informal controls include attempts to influence culture in ways not involving official authority, such as activism and other efforts to shape cultural norms (see Ciszek & Gallicano, Citation2013). For example, the example of associating Girl Scout cookies with orangutan deaths problematized the use of palm oil in cookies, and once the cause dominated the public stage, the national organization was pressured to take action (Curtin, Citation2016).

Tombleson and Wolf (Citation2017) used the circuit of culture as a lens for their study of Facebook’s LGBT campaign. They addressed the changes to the activist landscape that have occurred as a result of social media, similar to Hon’s (Citation2015) discussion. They concluded that the ability to easily engage in activism via social media, the acceleration of communication through social media, and the removal of traditional geographic barriers has resulted in greater articulations among the moments in the circuit of culture.

Research questions

As described in the literature review, researchers have successfully used the circuit of culture to gain insight into the flow and contestation of culture in society, from which social norms are developed, contested, and reinforced. No research could be found, however, that examines the impact of a global pandemic on a powerful social movement’s efforts to produce and consume content, share messages about identity, and shape culture. Research is needed in this area to aid in understanding this historic moment in time, as well as guide predictions of what could be experienced in similar scenarios.

Although each moment in the circuit of culture can and should be analyzed separately, Curtin and Gaither (Citation2005) maintain the importance of not viewing any one moment in isolation permanently, as doing so would not reflect the other possible articulations of meaning. Similarly, although the pandemic and social justice movement deserve isolated, in-depth examination, they should also be studied in the context of the concentric firestorm they fueled, which is the focus of the present study. Specifically, this study explores each moment from the circuit of culture through the following research questions:

RQ 1:How has the pandemic influenced the production and consumption of Black Lives Matter culture among supporters and what articulations do these moments have withregulation?

RQ 2:How has the pandemic affected meaning-making in the moments of identity and representation, including these moments’ articulations with regulation?

Although there are articulations among all moments in the circuit of culture, this study is delimited to addressing the articulation of regulation with the other moments due to participants’ emphasis on this area.

Methods

We conducted in-depth interviews to respond to the research questions due to the exploratory nature of this study, which is focused on meaning-making (see Marshall & Rossman, Citation1999). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants during the COVID-19 pandemic, so Zoom was used in lieu of in-person interviews. The interviews lasted about an hour and were audio-recorded and transcribed. Each transcript was coded with NVivo 12, a qualitative analysis software program, and thematic analysis was applied to the data (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994).

Data collection

To qualify for this study, participants must have participated in a previous study, which explored how the shooting of Keith Lamont Scott, a black man from Charlotte, affected their emotions and engagement on social media. We made this a requirement for two reasons: We wanted to enable a longitudinal comparison in responses between two very different cultural moments in the social movement for a future study, and we wanted to gather responses during the national uprising of protests and expressions of dissent following George Floyd’s death. The opportunity to amend the IRB document rather than writing a new one and the ease of recruiting people who had already interviewed with us previously enabled us to gather our data in a timely manner.

For the Keith Lamont Scott study, participants must have been at least 20 years old and lived within 2 hours of Charlotte at the time of the shooting. Recruitment for the prior study was conducted through various means, including community Facebook groups, an all-campus e-mail list, posters on campus billboards and in local organizations, and tweets from the study’s Twitter page. Although the recruitment did not disclose this qualification, people had to at least somewhat support the Black Lives Matter movement to participate. Potential participants were screened through a pre-qualification survey, which contained questions about their level of support for the Black Lives Matter Movement and demographic questions. Participants who were not students (referred to as community members in this study) were offered a $40 Amazon gift card as an incentive to participate in the study, while students were offered a $10 Amazon gift card. These incentives were a continuation of the incentive structure used in the initial Keith Lamont Scott study interview where community members received a higher incentive due to the need to travel to the campus and cover related expenses (e.g., parking, childcare).

After IRB approval was obtained, recruitment for the current study was conducted by emailing all 41 participants from the previous Keith Lamont Scott study. Up to three e-mails, spaced out at weekly intervals, were sent to each participant. Data collection began at the start of September 2021 and ended at the beginning of November 2021. Researchers interviewed 5 students and 20 community members for a total of 25 participants. This return rate is high, given the length of time between data collection points and the need to re-consent all returning participants. Regarding other demographics, 11 participants were Black (10 of the 11 were female), 10 participants were White (4 of the 10 were male), 3 participants were mixed race (Black-Latina, Black-Asian, Black-White; two of the three were female), and 1 participant was an Asian female. Most participants identified as heterosexual, with the exception of a bisexual woman and a gay man.

When possible, the race of the interviewer matched the race of the participant, in accordance with best practices for race-related research (Seidman, Citation1998). Of the 25 participants, 18 shared the same race as the interviewer. Nine of the 11 Black participants were interviewed by a Black interviewer, while 9 of the 10 White participants were interviewed by a White interviewer. In one case, a Black interviewer was matched with a White participant. In two cases, a White interviewer was matched with a Black participant. In the other four cases, a Black interviewer was matched with an Asian participant and three mixed-race participants, respectively. Regarding gender, 19 of the participants were female and the remaining 6 were male. The generic pronoun of “they” is used when referring to individual participants. Five of the participants were between ages 18–24, 10 participants were between 25–39, 6 participants were between 40–56, and 4 participants were between 57–75. NVivo 12 was used to compare themes (i.e., patterns in responses) via race, gender and student status, resulting in no observable divisions along these demographic lines at the node level.

We organized a three-part protocol for the data reported in this study, which is entirely focused on the Black Lives Matter movement following George Floyd’s death. The interview questions in this study represent the second part of a three-part protocol. The first part of the protocol was focused on discussing George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement; consequently, participants had time to reflect on this topic before responding to questions that were specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, many participants brought up the pandemic during part one of the interview despite not being asked about it, and these responses were included in the data analysis of this study. Participants’ initiative in bringing up the pandemic on their own demonstrates the importance of the pandemic in shaping their response to George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement. Interview questions include the following:

Has the pandemic affected your response to the current Black Lives Matter conversation or activities in any way?

Do you think the pandemic has affected your emotions in any way as you relate to the Black Lives Matter movement online or in person?

Have there been any pandemic-related incidents, political policies, or news reports that revealed anything to you about racism in society?

Many follow up questions were asked, including invitations for explanations and examples. The third part of the protocol, which is not included in this study, explored responses to various social media messages.

Data analysis

We initially coded the data using NVivo 12 to establish intercoder reliability for the parent and child nodes (see the Appendix) and to easily read, analyze, and categorize relevant portions of participants’ responses inside of the broad-ranging nodes, which were used to organize the data. This step enhanced the rigor of our data analysis. The content organized within the nodes was analyzed via a traditional thematic analysis to yield deep insight into our research questions (see Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Additional details about each step of this process are included below.We started by examining a few transcriptions, followed by meeting to discuss them and draft a codebook. Then, nine of the 25 transcripts were coded in NVivo 12 for intercoder reliability, using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient via a coding comparison query (Fleiss et al., Citation1969). We did this in two rounds. Six of the 9 transcripts were coded independently and received an ICR score of 76% agreement. After working out the differences, the remaining 3 of the 9 transcripts were coded independently, resulting in 90% agreement across all nodes between the two coders. The averaged ICR score was 83% across the 9 transcripts that were used for intercoder reliability. The coders independently coded the remaining transcripts after this sufficient ICR score was established. During the process, we engaged in line-by-line coding, highlighting relevant paragraphs that were important to the meaning the participants expressed.

The following NVivo nodes were included in the data analysis: pandemic had an effect, pandemic did not have an effect, pandemic-related incidents and racism in society, appropriation, perspective by incongruity, and referent criterion. The Appendix shows a visual organization of these nodes with additional details. Within each node, thematic analysis was used by cataloging every type of response within each child node described in the Appendix and in each parent node for the parent nodes without children (i.e., appropriation, perspective by incongruity, and the referent criterion). We followed an iterative process of creating and revising themes in response to each research question and noted explanations to questions of “why” with each explanation we found for each response, as well as representative quotes (see Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Although the point of qualitative research is not to make statistical inferences, the prominence of themes can be insightful, so a tally was kept for every individual who expressed a theme. Quotes characterizing the themes were noted and referred to throughout the analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Reflexivity

As noted by the previous Journal of Public Relations Research editor, Bey-Ling Sha (Citation2016), reflexivity should be included in any study involving interviews or focus groups because the researcher acts as the instrument in gathering data, analyzing it, and making meaning of it: “Readers need to know more about you, your possible implicit biases in the treatment of data, and how you strived to mitigate those inherent biases” (p. 123). She compared this disclosure to the expectation that survey instruments would be sourced in quantitative manuscripts. Our author team includes two Caucasian White women (she/her), one of whom is from a multiethnic blended family, and two mixed-race individuals: One is White and Black (they/their), and one is White and Native American (she/her). One of the authors did not choose to disclose personal information but was not involved in the data collection or analysis. In addition, we hired a Black man (he/him) and a Black woman (she/her) to conduct some of the interviews; they are named in the acknowledgments section and were offered the opportunity to coauthor other papers from the data they helped to collect. We attempted to maintain neutrality during data collection by avoiding reactions that might appear to reward certain answers; however, we also refrained from a cold, impersonal demeanor. We believe we showed a professional level of warmth and empathy during the interviews.

With regard to the data analysis and the reporting of the data, we viewed our role as telling a story from our participants’ perspectives in the results section and then interpreting the stories for theory and practice in the discussion section. We needed to think as insiders to generate theoretical insights and practical insights from this vantage point; however, we also circled back through our work to ensure our framing was respectful toward with any reader, regardless of their approach to the pandemic or other issues.

Qualitative assessment

We followed several of Wolcott’s (Citation1994, Citation2001a, Citation2001b) recommendations for producing a compelling qualitative study. For the implicit challenge of validity, we asked questions and listened deeply. We did not pretend to know a lot about the individual’s experience to avoid becoming our own best informant. We transcribed the recorded interviews and discussed our interpretation of the findings among members of our team. We provided transparency through our reflexivity section and the other details regarding data collection and analysis. In the results section, we included emic quotes to help readers determine the credibility of our interpretation. We also acknowledge the limitations of our study. As a qualitative study, our work is not intended to be objective (although we aspired to be unbiased), and our work is not generalizable to all concentric firestorms. We were limited by the types of people who chose to participate in our study. Furthermore, our participants might not have represented their experiences completely. As noted by Wolcott (Citation1994), “We are better off reminding readers that our data sources are limited and our informants might not have gotten things right either rather than implying that we would never report an under-verified claim” (p. 351).

Results

All 25 participants noted the pandemic had some effect on the way they create and interpret meaning surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement. There were minor differences with regard to the way the pandemic was manifested in their content creation and interpretation. Nineteen of these participants also noted that the pandemic did not affect all aspects of their relation to the Black Lives Matter movement. Depending on the participant, production and consumption were largely influenced by factors such as health and safety concerns, emotional energy levels, desire to connect with others, and flexible at-home schedules in the context of the pandemic. Identity, representation, and regulation were shaped by racial incidents, financial status, safety concerns, and audience perceptions. Due to space limitations, one representative quote for each moment in the circuit of culture is included; in some cases, additional short quotes also appear.

RQ 1: How has the pandemic influenced the production and consumption of Black Lives Matter culture among supporters and what articulations do these moments have with regulation?

Most participants agreed that the pandemic had some effect on the culture of the Black Lives Matter movement. Some of these participants experienced the impact on the Black Lives Matter culture in a general sense. Other participants reported specific effects, particularly increasing or decreasing motivation to engage and affecting the extent to which they participated on social media and in person.

Production

The pandemic influenced the desire to protest in person, the amount of content people produced on social media, and the adaptation of social media content to reflect the collision of the Black Lives Matter firestorm with the pandemic firestorm. Specifically, many participants expressed a desire to protest in person that was eclipsed by worries for maintaining COVID-19 safety protocols, creating an articulation with formal regulation. Some people were concerned about their personal health, while others expressed concern about getting COVID-19 and passing it to a vulnerable family member. Instead of protesting in person, some of these participants used their energy to cope with emotional exhaustion from the pandemic, while others increased their production of social media content, citing a desire to be useful:

Because of the pandemic was going on, I wanted to be out there in the protests, but I have an elderly mother to take care of and so I can’t really be out there in the protests, risking it all. So, social media was a mechanism that I could use to support the protests.

One participant reported protesting in person because they believed in the efficacy of wearing a mask.

Regardless of how the pandemic affected energy levels, participants described a cultural expectation for taking a stand in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly when considering the “silence is violence” slogan. This slogan, which contributes to the area of informal regulation in the circuit of culture, portrays silent bystanders as perpetrators: “[There’s] that feeling that. belief that if I do nothing, you know, I’m complicit. … You can’t just not say something about it. You have to speak up, and you have to condemn these acts.” Despite the pandemic, most participants expressed a desire to engage in production by publicly taking a stand for Black Lives Matter. However, some White participants expressed hesitancy in the moment of production due to the fear of expressing their support in an inappropriate way, particularly on a highly charged issue that was in the social media spotlight. This situation created an articulation between production and identity.

In creating an articulation with informal regulation, most participants who declined to protest in person expressed support for those who did decide to protest in person. A few of these participants discussed the impact of the pandemic on their photo sharing via social media. One participant said it was “hard to show support for protestors during a pandemic” and hesitated in sharing photos of protesting crowds during a time of social distancing.

Consumption

Participants reported that the emotional effects of the pandemic, the home isolation resulting from the pandemic, or a combination of these two factors influenced their consumption of Black Lives Matter content for the purpose of seeking information, connecting with others, expending pent-up energy, or accomplishing a combination of these goals. A significant number of participants cited free time and a flexible at-home schedule that made it convenient for people to educate themselves, thus leading to information-seeking behaviors (e.g., scrolling through social media, catching up on traditional news, and conducting research related to Black Lives Matter). In fact, many responses pointed toward the role of home isolation during the pandemic as a crucial factor in heightening awareness of the details regarding George Floyd’s death and deepening knowledge about the Black Lives Matter movement. Not surprisingly, participants reported having pent-up energy, making this information-seeking a natural outlet for filling the time they would have spent on routine activities (e.g., work, school).

However, not all participants reported that the pandemic increased their consumption of Black Lives Matter culture. Some participants reported too much exhaustion, stress, or fear from the pandemic to seek out any more information, so they disconnected from social media and avoided the news. As seen through both heightened information-seeking and reduced information-seeking, formal regulations that led to home isolation had an impact on the consumption of Black Lives Matter content online.

These formal regulations also had a positive effect on how participants processed George Floyd’s death, allowing them to do so primarily in their homes as opposed to a workplace or any other public place: “I probably would have to code-switch more often than I would versus just being at home. I guess I was able to process it better actually because I was home.” This participant also discussed working as a Black female in a predominately White workplace, creating articulations with identity. This is another context in which regulation forms an articulation with consumption.

RQ 2:How has the pandemic affected meaning-making in the moments of identity and representation, including these moments’ articulations with regulation?

Overall, participants shared observations about how the pandemic affected what it meant to be Black, regardless of the participant’s race. Cases of appropriation and perspective by incongruity revealed disrespect and racism, respectively. A discussion of these moments and their articulations with regulation appears below.

Identity

The pandemic influenced meaning-making around identity as it relates to race-related rates of health outcomes, the opportunity to align with Black people and Black businesses through donations to Black Lives Matter or purchases from Black businesses to help them survive the pandemic, and a historical moment in deciding whether to trust the health establishment in the wake of the Tuskegee experiments (Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Citation2020). These themes are explored in greater detail below.

The pandemic provided a highly visible context for identifying disproportionate health consequences that accompany Black and Hispanic communities in terms of socioeconomic status and how political responses exacerbated those consequences:

Cuomo said that COVID affects the majority of Black and Brown people, when that word came out, Trump came on a news conference and said, “Everything’s opened up.” [That] just proved to me like, this man don’t give a hoot because he doesn’t care whose lives it affects.

This participant highlighted a moment of articulation between regulation and identity because safety protocols related to the people who are most harmed by COVID-19. One of the reasons for disproportionately negative health outcomes, as noted by several participants, was the dominant representation of Black and Hispanic communities in vulnerable frontline positions.

The pandemic also had an influence on identity through the decision to financially support the Black Lives Matter movement and help Black businesses survive. Participants who said they were in an unstable financial position reported one of two outcomes of their behavior–-one of which was reducing the amount they donated to Black Lives Matter causes. The other outcome was that participants stated they would continue to support Black Lives Matter regardless of their financial position, suggesting that their emotional ties to the movement were enough to override some of their economic concerns. Participants who were in a stable financial situation stated they were fortunate to have remained in stable financial situations and could therefore continue financially supporting the Black Lives Movement in the way they had done prior to the pandemic. A few participants said the precarious nature of the pandemic economy encouraged them to support Black businesses. Describing the financial impact of the pandemic, one participant commented:

African Americans [are] being disproportionately affected by the pandemic, on top of the jobs, economically speaking, they’re more affected. …I can’t think of anything that hasn’t been affected that doesn’t reveal certain levels of systemic racism that the pandemic hasn’t already revealed.

An articulation between the moments of identity and regulation can be seen through the effects of the pandemic on the economy and the people hurt most by this instability.

An additional way the pandemic influenced meaning-making in the moment of identity is through the decision of whether to trust the health establishment. The referent criterion can be seen in one participant’s mention of distrust in the current medical establishment based on the Tuskegee experiments: “We are still afraid to get flu shots because of Tuskegee experiments, so, just think if they come out with a COVID [vaccine], people aren’t going to go get that either, you know?” The participant wrestled with the decision of whether to trust a medical establishment with a history of abusing the Black community. The moment of informal regulation creates an articulation with identity as Black people are confronted by a torrent of information from the medical community about what to do in the pandemic without acknowledgment of past transgressions or resources to help overcome them.

Representation

The pandemic affected representation because disrespect for the Black Lives Matter movement was generated by pandemic-related cases of appropriation; also, racism was identified through a perspective by incongruity. Both of these cases had notable articulations with the moment of regulation. These themes are explored in detail below.

The safety regulations of the pandemic were among the most prominent themes in the data pertaining to representation, and this is a key context in which appropriation occurred. Anti-mask protestors appropriated the phrase “I can’t breathe” to refer to not wanting to wear masks. Many participants expressed disapproval, disgust, or anger at the appropriation:

I saw this White woman with an “I can’t breathe” T-shirt on and I like, had to get her together about that. … It’s a slogan that has been co-opted and … I have a really big problem with that fact. … People are literally dying and to see this – the combina – the comparison of police murdering Black bodies to literally the choice to just put on a mask? It’s sickening, it’s literally angering.

Many participants objected to the disrespect they experienced when consuming content about the trivialization of Floyd’s pleas for help, and some participants engaged in production by calling people out for it. In doing so, a war of informal regulation occurred by the existence of debates regarding the legitimate use of the slogan.

In addition to the disrespect many participants perceived through appropriating the words “I can’t breathe,” some participants also identified a form of racism they observed through a perspective by incongruity:

If we think about the protests against pandemic lockdown measures, right, and we kind of put those side-by-side with protests against George Floyd, right, there’s one powerful picture of Huntington Beach when a bunch of White protesters were out protesting about the closure of the beach. You don’t see any police around, all the protesters are fine, whereas protests against George Floyd’s death and against systemic racism in this country, like a couple weeks later at the very same intersection, there are at least 10 police SUVs and it was deemed an “unlawful gathering,” rather than a peaceful protest. So, stuff like that sort of highlights the continual racist nature of this country.

In an articulation with formal regulation, participants noted racial disparities in the way Black Lives Matter protests were policed more harshly than anti-shutdown protests.

Discussion

This study contributes to a handful of public relations studies that use the circuit of culture as a framework for theory building (e.g., Curtin & Gaither, Citation2006; Curtin, Citation2016; Han & Zhang, Citation2009; QQuichoco & St. John, Citation2022) by investigating concentric firestorms, which we situate within the broad category of literature about social media since concentric firestorms do not have to happen in the context of social movements. For example, researchers could study a company’s crisis management inside of another firestorm context, such as an economic depression or a war.

Through the first research question about production and consumption, this study found that the emotional effects and the regulations of the pandemic caused participants to either significantly increase or decrease their digital engagement, refrain from posting protest images that might suggest a disregard for social distancing rules, and process George Floyd’s death differently in home isolation. For some, the home environment was an additional layer inside of the pandemic environment, which further shaped meaning-making.

In response to the second research question, this study found that the pandemic created heightened awareness of race-related health and financial outcomes, as well as disproportionately policed protests––showing clear articulations with formal regulation through a perspective by incongruity. These observations created meaning in the moment of identity regarding elements of what it means to be Black in contemporary society. This finding parallels a discussion by Curtin and Gaither (Citation2006) about how an examination of the smallpox epidemic through the lens of identity produced clear distinctions between the “haves” and the “have nots.” The second research question also included representation and its articulation with regulation. Participants engaged in informal regulation by objecting to the appropriation and consequent trivialization of the words “I can’t breathe” by anti-mask protestors. These words revealed a grave disregard for George Floyd and were unacceptable to participants.

Theoretical implications

This study provides evidence for Ciszek’s (Citation2015) argument that the circuit of culture is a useful framework to advance theory building about activism in the public relations literature, and it contributes to the literature about online firestorms by introducing the concept of the concentric firestorm to refer to a double firestorm: There is an outpouring of negative emotion and negative messages from two firestorms rather than one, and the conditions of one firestorm shape the other firestorm. The concentric firestorm in the present study can be visualized as concentric rings in the sense that the surge of Black Lives Matter activism that was catalyzed by Floyd’s death occurred inside of the pandemic environment. The informal and formal regulations of the pandemic environment––ranging from the social taboo of joining a crowd of activists to stay-at-home orders and ripple financial consequences affecting jobs––tended to have an impact on the amount of time supporters invested in digital and in-person Black Lives Matter activism, as well as financial contributions to the movement.

For some people, the pandemic increased their investment of energy and emboldened the decision to donate during a time of global financial uncertainty, and for others, exhaustion from the pandemic resulted in scarce emotional stamina, time, and resources for Black Lives Matter activism. Regardless of these differences, the amount of energy an individual had for the inner ring was first magnified or reduced by the outer ring (see ). This revelation is important to consider in the context of Hon’s (Citation2015) discussion of the personal dedication and energy that fuels flash activism in the form of fast, low-commitment efforts such as social media activity. Specifically, personal dedication and fervor for a social movement does not stay at a high level for individuals contributing to a social movement, similar to challenges with maintaining volunteer energy for advocacy organizations (see Gallicano, Citation2013). Various forces can enhance or deplete personal energy for the movement, including the outer ring of a concentric firestorm.

Figure 1. The Concentric Firestorm.

Our finding about the outer ring’s influence also connects with Smith’s et al. (Citation2019) study in the sense that the outer ring of a concentric firestorm can amplify or reduce an individual’s level of empowerment toward social media activities. In addition, the outer ring can potentially play a role in social stake. For example, the pandemic resulted in a rule about not gathering in crowds, which reduced message production and message sharing of crowds of protesters. In addition, our finding about the hesitancy to speak out on social media for fear of saying the wrong thing among some of our White participants reinforces the importance of communicative competence and sense of identity in expression on social media. Additional theoretical insights about concentric firestorms are addressed below.

A perspective by incongruity from racial concentric firestorms

For cases in which one of the events fueling a concentric firestorm involves race, this study suggests that the duality of the firestorms creates a nested context in which attention to race is heightened by one firestorm, and racial injustice can be identified through the other firestorm through a perspective by incongruity (Burke, Citation1954). This perspective by incongruity can emerge through the lens of any moment in the circuit of culture. For example, participants noted racial inequities by comparing how Black Lives Matter protests were policed more harshly than anti-lockdown protests. This event can be seen through the lens of formal regulation, experienced through consumption, and discussed via production. The juxtaposition of what appears to be inconsistent regulation produces meaning in the moment of representation with consequences for what it means to occupy certain racial identities or align oneself with them as an ally. Related to Quichoco and St. John’s (Citation2022) model, individuals might struggle to believe in the narrative fidelity of equality in the face of lived experiences that appear to contradict it (also see Fisher, Citation1985).

We also want to note that our study reinforces Tombleson and Wolf’s (Citation2017) conclusion that social media increases the interplay among moments in the circuit of culture. Prior to social media, visuals contrasting the policing of the closure of a beach with the policing of a Black Lives Matter protest in the same city would arguably not circulate among activists as widely as they did through digital networks. In the case we examined, social media facilitated a vision for how formal regulation (i.e., policing) was applied differently in the same city during a similar timeframe.

The impact of concentric firestorms on virtual density

In this study, participants who would have protested in person if not for the pandemic were limited to the options of engaging with the Black Lives Matter movement through financial support, online engagement, or a combination of both actions. Those that increased their online engagement contributed to an environment where people were already digitally engaged regardless of the effects of the pandemic. This study contributes to theory building by suggesting that the heightened emotional energy resulting from a concentric firestorm increases what this study refers to as virtual density in online environments. The term virtual density is used to describe the extent to which people participate in shared digital spaces on a particular topic of interest. Characteristics of virtual density include the number of people participating in digital conversations; the number of messages shared; and the number of interactions, comments, and responses to the messages on a particular topic.

High virtual density appears to play a role in the articulation between production and informal regulation by creating a social norm that pushes people toward speaking out about the issue on social media. This effect is arguably related to social stake from Smith’s et al. (Citation2019) social media protest model by generally increasing social media activity and the sense of obligation to support one another in social media communities. In fact, high virtual density could possibly help to offset challenges described by Smith’s et al. (Citation2019) related to both empowerment and communication competence, seeing how some White participants set aside their fear of saying the wrong thing due to their sense of responsibility to express support in their online networks.

This study also introduces the concept of virtual saturation to refer to a tipping point in which virtual density has achieved the critical mass that characterizes issues of global significance. At the point of virtual saturation, we speculate that an issue has probably become polarized, with little neutral ground: In the moment of consumption, people have generally paid attention to the issue and chosen a side. Also by this point in the cycle of production and consumption, real dialogue becomes less likely, as sides talk at each other and compete to win arguments rather than really listening to understand one another. A benefit of this explanation is that it helps to understand the heartless appropriation of the “I can’t breathe” slogan by the anti-mask movement. By the time virtual saturation has occurred, distance between “us” and “them” is significant. The polarization between sides arguably reduces empathy. The appropriation of “I can’t breathe” by some pandemic anti-maskers perhaps becomes a way to be clever and get attention, with little thought to its impact on Black Lives Matter supporters. In addition, once virtual saturation has occurred, there is heightened attention to regulation, as each side is hypervigilant for inconsistencies and injustices in decision making.

Appropriation flashpoints in regulation battles

In the moment of informal regulation––the battlefield for the domination of cultural norms––appropriation from the Black Lives Matter movement to the anti-mask movement was found to be a flashpoint for contestations over the respect given to the Black Lives Matter movement. Many participants were angered enough to engage in confrontation by denouncing the anti-mask appropriation of “I can’t breathe.” Thus, there is potential for appropriation across the sources of a concentric firestorm (in this case, the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement), and this rhetorical device has the potential to instigate a battle in the culture war. Another observation is that while mask-wearing controversies and the phrase “I can’t breathe” sparked intense discussions separately, the anti-mask appropriation of the phrase “I can’t breathe” prompted reactions of shock, disgust, and anger. Thus, this study’s findings are similar to Maiorescu-Murphy’s (Citation2021) observations of appropriation in the context of Dior’s Sauvage perfume. Although the source of the offense in our study was another protest rather than a company, the cultural appropriation had the outcomes of broad publicity about the offensive message and anger. Although cultural appropriation is commonly examined in the context of a company’s moral lapses (e.g., Biron, Citation2016; Maiorescu-Murphy, Citation2021), our study is novel in its examination of appropriation by a protest representing a different social movement.

Sticky slogans, slippery meaning, and compelled speech

One of the viral slogans in the Black Lives Matter protests was “silence is violence,” which compelled some White supporters to overcome their fear of saying the wrong thing. Similar to the message distortions discussed in Curtin’s (Citation2016) study of the two Girl Scouts’ plight to remove palm oil from cookies, there is also a rhetorical manipulation involved in this message strategy. Just as eating a cookie does not kill an animal, individual silence on social media does not result in physical harm; it may cause distress but probably not at the level of “violence,” at least generally speaking. Beyond the accuracy issue of the two messages, the “silence is violence” slogan deserves additional scrutiny for its social condemnation of withholding speech. In the context of social justice movements, U.S. society has transitioned from merely suppressing unwanted views through informal regulation tactics, such as public shaming, boycotts, and job loss, to demanding collective expression of the desired views by equating silence with complicity (Turley, Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

This strategy of compelled speech, regardless of the moral context, is problematic from a Kantian perspective (see Bowen, Citation2005, for a summary of Kantian ethics). This coercive strategy plays off of guilt and fear, inhibiting an individual’s moral decision-making autonomy. Moreover, Kantian theory discards situational-based justifications. If coercing people into expressing a social viewpoint is wrong in any possible situation, it is also unjustifiable in the context of social justice movements. Moral issues aside, the “silence is violence” slogan appeared to be a persuasive form of informal regulation. In fact, this rhetorical removal of a neutral zone, coercing people to choose between “us” and “them,” is reminiscent of the polarization strategy used in other movements, such as the Columbia University student protest of 1968 (Klumpp, Citation1973).

Practical implications

In this section, we discuss the topics of virtual density, energy levels for engaging in activism, the perspective of incongruity, appropriation as it relates to expectations and ethics, and the referent criterion.

Virtual density and disparate energy levels

When considering the implications of virtual density, activists should note that the heightened visibility created by a virtually dense environment provides conflicting motivations between staying quiet and speaking out. Activists could quicken the resolution of conflicting pressures by providing easy ways for people to express their support, and they should understand that the outer ring of a concentric firestorm will impact supporters unevenly. In addition, activists can recognize the uneven impact of concentric firestorms and advocate on behalf of those in the movement who are too worn out to advocate for themselves. They can also consider ways to help lift the spirits of people who are worn down by the outer ring of the concentric firestorm.

Perspective by incongruity

Incidents of perspective by incongruity can help activists provide clear examples of unfair treatment and contradictory communication. For example, participants emphasized that Black and Hispanic workers were disproportionately represented as frontline workers in highly vulnerable positions. The rhetoric surrounding frontline workers praised them as heroes, yet in many other circumstances of the pandemic, Black and Hispanic lives were disregarded, as seen through negative health and financial outcomes. The contrast resulting from the juxtaposition can be a valuable strategy for sharpening perceptions of mistreatment. We also want to note that examples of racial injustice in the context of the pandemic received considerable attention. Similar to Huang’s et al. (Citation2021) discovery that the most emotionally engaging social media messages a Chinese company sent were ones about the pandemic, messaging about a powerful environmental circumstance that impacts daily living stands out in the consumption of messages. Our study adds fuel to this finding and connects it with Quichoco and St. John’s (Citation2022) discussion of the power of lived experiences in decision-making, represented by their concept of resonance.

Appropriation armor and ethics

Based on this study, activists can anticipate the possibility of appropriation between sources of a concentric firestorm and do their best to emotionally prepare themselves for it. The occurrence of appropriation between the anti-mask movement and the Black Lives Matter movement should serve as a referent criterion for future concentric firestorms. The expectation of appropriation between firestorm sources can potentially lessen the emotional shock and exhaustion that can result from an unanticipated attack. In doing so, this knowledge has the potential to make activists less emotionally vulnerable.

A second practical implication regarding appropriation is directed toward activists who might consider using appropriation to their advantage. Appropriation cannot be used in a moral vacuum: Activists are moral agents, as discussed by Jiang and Bowen (Citation2011) in their application of Kantian deontology to activist groups. The participants in the current study experienced a serious disregard for a member of the Black community through the appropriation of “I can’t breathe” by some members of the anti-mask movement. Although appropriation is not inherently unethical, activists should avoid it if it involves not treating a human being with dignity and respect (e.g., Bowen & Prescott, Citation2015). In this case, George Floyd, through the use of a repeated plea for his life, was used as a means to an end (in this case, a shocking way to demand maskless rights). Activists should build solidarity in the denouncement of appropriating phrases born out of grave injustices. In doing so, they can take a stand for integrity in the civic sphere and reduce the erosion of human civility.

Referent criterion

An additional implication of this study is the continued relevance of the referent criterion in the meaning-making process (see Kim & Grunig, Citation2011). In our study, a participant used the referent criterion of the Tuskegee experiments to express distrust when a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine was considered. Thus, the referent criterion can be an important factor in explaining distrust, and the medical establishment should consider strategies for strengthening relationships with communities it has hurt in the past, such as making small promises and keeping them (e.g., Hon & Grunig, Citation1999). From the standpoint of Quichoco and St. John’s (Citation2022) model, the medical establishment should also tap into positive lived experiences with the medical system (if available) to encourage continued trust.

Limitations and future research

As noted previously, the results cannot be generalized as ground truths that necessarily apply to every instance of a concentric firestorm; however, as noted by Wolcott (Citation1994), “there must be a capacity for generalization; otherwise, there would be no point to giving such careful attention to a single case” (p. 113). For example, we expect that theoretical insights from this study, such as the discussion of perspective by incongruity, can be helpful with navigating some concentric firestorms in the future. We also believe that experiences our interviewees shared will resonate with some other people’s experiences in a meaningful way. Future research can explore the extent to which the findings in the Floyd-pandemic firestorm apply to a different context while continuing to deepen knowledge about concentric firestorms, whether doing so through the circuit of culture or a different framework, such as a pentadic analysis (e.g., Burke, Citation1978) or critical discourse analysis (e.g., Brindusu Albu & Wehmeier, Citation2014; Ciszek & Logan, Citation2018; de Brooks & Waymer, Citation2009). In addition, future research can explore how organizations contribute to social movements inside of a concentric firestorm.

Acknowledgements

We thank our outstanding research assistants and independent study students for their contributions to this paper: Tremain Ingram for conducting 11 of the interviews; Iris Hudson for conducting one of the interviews, Josh Gordon for transcribing 13 of the interviews, and Nana Sledzieski for managing our records.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albu, B., & Wehmeier, S. (2014). Organizational transparency and sense-making: The case of Northern rock. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2013.795869

- Al-Kandari, A., & Gaither, T. K. (2011). Arabs, the west and public relations: A critical/cultural study of Arab cultural values. Public Relations Review, 37(3), 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.04.002

- Biron, G. (2016). The cultural appropriation of American Indian images in advertising 1880s-1920. Whispering Wind, 44(3), 20–25.

- Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. Journal of the American Ethnological Society, 42(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12112

- Bortree, D. S., & Seltzer, T. (2009). Dialogic strategies and outcomes: An analysis of environmental advocacy groups’ Facebook profiles. Public Relations Review, 35(3), 317–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.002

- Bowen, S. A. (2005). A practical model for ethical decision making in issues management and public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 17(3), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1703_1

- Bowen, S. A., & Prescott, P. A. (2015). Kant’s contribution to the ethics of communication. Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics, 12(2), 38–44.

- Briones, R. L., Kuch, B., Liu, B. F., & Jin, Y. (2011). Keeping up with the digital age: How the American red cross uses social media to build relationships. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.12.006

- Burch, A. D. S., Harmon, A., Tavernise, S., & Badger, E., (2021, April 20). The death of George Floyd reignited a movement. What happens now? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/20/us/georgefloyd-protests-police-reform.html

- Burke, K. (1950). A rhetoric of motives. Prentice-Hall.

- Burke, K. (1954). Permanence and change: An anatomy of purpose (2nd ed.). Bobbs-Merrill.

- Burke, K. (1978). Questions and answers about the pentad. College Compositions and Communication, 29(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.2307/357013

- Capner, M., & Caltabiano, M. L. (1993). Factors affecting the progression towards burnout: A comparison of professional and volunteer counselors. Psychological Reports, 73(2), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.2.555

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2020). The Tuskegee timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

- Chon, M. -G., & Park, H. (2020). Social media activism in the digital age: Testing an integrative model of activism on contentious issues. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(1), 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019835896

- Ciszek, E. L. (2015). Bridging the gap: Mapping the relationship between activism and public relations. Public Relations Review, 41(4), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.05.016

- Ciszek, E. L. (2016). Digital activism: How social media and dissensus inform theory and practice. Public Relations Review, 42(2), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.02.002

- Ciszek, E. L. (2019). Activism. In B. R. Brunner (Ed.), Public relations theory: Application and understanding (pp. 159–173). John Wiley & Sons.