ABSTRACT

Urban planning/management is a complex process requiring multidisciplinary technical support and public approval. With the rapid development of information and communication technology, e-participation has brought unprecedented opportunities for urban planning and management in the sense that it potentially represents more efficiently and effectively the interests of different citizens. Nevertheless, the availability of new technologies does not guarantee success. In China, many local planning agencies began with enthusiastic ideas and investments but ended up with disappointment and frustration. Therefore, it is of critical importance to understand the general interest of the public to have access to and use information and communication technologies (ICT) in urban planning processes. This study develops a Stated Preference (SP) experiment to measure citizen’s preferences and intentions to use modern ICT media in urban planning processes. The results show that the intention to participate in urban planning processes using different ICT tools differs by socio-demographic variables. The research findings provide relevant information about the effects of different communication strategies on citizen engagement.

Introduction

Public participation has attracted considerable interest in urban planning theory and practice. Numerous studies (e.g., Arnstein, Citation1969; Forester, Citation1982; Healey, Citation1992; Barndt, Citation1998; Booher and Innes, Citation2002; Evans-Cowley and Hollander, Citation2010) have reflected on the meaning and role of participation, and described various experiences that can be viewed as showcases of successful or failed participation processes (e.g., Wang et al., Citation2007; Lauwaert, Citation2009; Williamson and Parolin, Citation2012; Cheng, Citation2013; Hemmersam et al. Citation2015; Minner et al., Citation2015). As witnessed in the vast literature on public participation, practices differ widely by country, city, theme, and time period.

The most basic level of public participation, focusing on information provision, tends to be widespread. As part of a more general democratization process, public hearings, discussion groups, and other forms of participation have been tried with mixed success starting in the 1970s, particularly in European countries with a strong urban planning tradition and powerful social democratic political parties. Pilots of small-scale plans, with the decision authority shifting to the local population, were also developed and executed. Worldwide, a diffusion of this practice can be observed, but with differentiating speed and intensity as a function of economic growth, democratization processes, the co-evolving political system and professionalism of the urban planning discipline, and the maturity of the urban planning tradition.

Over the last three decades, China has experienced the largest urbanization in its history and this trend is predicted to continue. Massive urban construction and transformation follow this rapid urbanization, requiring designs and plans for the new developments. Increasingly, local governments and planning professionals have become aware of the importance of public participation in plan-development and implementation. The potential benefits of public participation range from gaining up-to-date local knowledge that is not readily available from standard sources to soliciting planning/design ideas for problem solving, reducing the impact of NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard), and monitoring code violations. The Urban–Rural Planning Law in China enforced in 2008, points out the requirements for public participation in urban planning and management processes and participation procedures. It reflects that the Chinese central government is shifting from a control-type, top-down towards an open-minded planning approach, trying to collect citizens’ opinions as important information about possible future urban improvement (Zhou, Citation2018). The organization of public participation is strongly influenced by Western participatory planning theories, which have become more accessible (Zhang, Citation2008).

Achieving effective public participation, however, is not an easy task because engaging with the general public has not been practiced much. Planning authorities lack the experience of involving the public in planning processes, while at the same time the public is not used to being involved in planning issues. Although the terms and requirements of citizen participation have been legislated at the national level, public participation at the local level remains relatively under-developed (Fung, Citation2015). Especially in practice, some planners simplify participation processes and involve the public just to satisfy legislative requirements. Planning decisions are basically made by government with little citizen engagement. Although Chinese citizens with better education have become increasingly aware of their rights to be involved in urban planning decision-making processes that affect their living environment (Zhou, Citation2018), the lack of education and ability to participate and provoke change also prevent some segments of the population, such as low-income groups, from being fully involved in the planning process (Albrechts, Citation2002). Chinese planners need to develop the skills and tools for communicating with the public.

In the age of smart cities, public participation has received a new meaning. Although the concept of smart city has rapidly become a buzz word, in addition to smart mobility and energy, the development and use of digital technology to support involvement of the public in urban governance, is one of the key domains of application in smart cities (Albino et al., Citation2015). Smart cities are technology-oriented and designed to make cities sustainable through participatory governance (Caragliu et al., Citation2011). Developing new online technologies and platforms for communication is essential in promoting effective engagement in planning processes (Batty et al., Citation2012). Modern information and communication technology is gradually replacing traditional ways of public participation.

Several scholars have examined the impact of new ICT technology on citizen engagement (Boulianne, Citation2009; Skoric et al., Citation2016). ICT could make up for the shortcomings of traditional means of participation, such as public hearings and citizen panels, which have been criticized as time and money-consuming due to their fixed location and fixed time (Kolsaker and Lee-Kelley, Citation2006). The application of ICT tools, social media, and crowdsourcing potentially expand public participation in urban planning, promising a more immediate relationship between individual and local governments (Hemmersam et al., Citation2015). The arrival of the web and social media has changed our daily lives, including introducing new forms of personalized public engagement. It has intensified the interaction between planners and citizens because both data and plans are being shared (Hopkins, Citation2011).

Nevertheless, the availability of new ICT technologies does not guarantee success. Experts find that current main forms of web-based participation are largely passive, and that Web 2.0 technologies are becoming more interactive for participators, reflected in portals, software, crowd-sourced systems, and decision support systems (Batty et al., Citation2012). Online digital systems and extensive computation require substantial investments and have high maintenance costs. Some scholars argued that different types of ICT tools such as e-mail, online chatting, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter give citizens more choices and allow planners and citizens to communicate, share their views, and provide feedback (Zheng, Citation2017). These ICT tools improve the efficiency and effectiveness of citizen participation compared with traditional tools such as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, telephone notification, and face-to-face group discussion, but the use of e-participation remains at a low level. It follows that it is important and relevant to understand the general interest of the public to have access and use such urban technology. Under what circumstances would these tools be used and be the preferred mode of communication?

To better understand this phenomenon, researchers have highlighted different aspects of the factors affecting citizens’ e-participation. Socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, income, and education were tested (Hansen and Reinau, Citation2006). The roles of citizen perceptions or attitudes toward e-participation use and e-participation applications’ functionality were also examined (Kolsaker and Lee-Kelley, Citation2006). And the role of e-participation applications’ functionality was analyzed for citizens’ e-participation (Zheng, Citation2017). However, the factors of e-participation in urban planning have been overlooked. So, the present study sets out to elicit people’s preferences for using modern ICT media in urban planning processes. The city of Wuhan, China, serves as a case study area. To that end, we designed and implemented a stated preference experiment, in which a sample of respondents was asked to indicate their intention to participate in urban planning processes using modern information and telecommunication technology. This paper will report the design and main results of this study.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section documents the strategic decisions underlying the design of the study in general and the experiment in particular. Next, we outline the sampling and data collection process and provide the results of a descriptive analysis of sample characteristics. Then we discuss the results of the main analyses. We complete the paper by discussing the implications of the findings.

Design of the Study

Many public administration scholars and practitioners have drawn attention to the wide diversity in citizen participation in urban planning practice (e.g., Batty et al,. Citation2012; Koch, Citation2013; Fung, Citation2015). They pointed out that public participation as a means of empowering citizens in political decision-making should consider the full menu of design choices including different ways of exchanging information and different levels of empowerment. Understanding the interest of different segments of the population in participation as a function of contents and communication mode is thus of interest to organize effective and efficient participation. Researchers have highlighted different aspects of public participation and ICT use with regards to urban planning, but there is a lack of quantitative analysis of citizens’ willingness to participate in urban planning processes using ICT tools.

This paper tries to fill this gap by investigating the intention of citizens to become engaged in online participation in urban planning and management. To obtain data on the intention of citizens to engage in urban planning, this paper develops a Stated Preference (SP) experiment that provides a way to measure the willingness of online participation. Stated Preference experiments are based on descriptions of hypothetical or virtual decision contexts. Using a SP survey, researchers can specify specific situations based on influential attributes and contexts that are relevant to the choice behavior of interest.

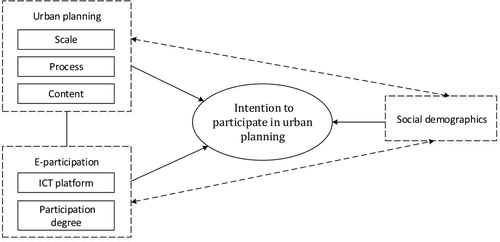

We contend that public participation depends on urban planning scale, stage, and content, the nature of available ICT platforms, and the degree of online participation (See ). The former three attributes are associated with urban planning, while the latter two attributes are associated with the ICT tools used to participate in urban planning.

Attributes

Attribute 1: Urban Planning Scale

Scale is an important issue in planning participation, which is recognized by both the magnitude of the population and the physical scale (Pickering and Minnery, Citation2012). The scale in this study is defined as the spatial geographic scale. Previous research has documented public participation practices and analysis for different spatial scales, but most studies have focused on the smaller scale, i.e., the neighborhood. Pickering and Minnery (Citation2012) explored metropolitan regional participation through two case studies in South East Queensland and Metro Vancouver. Hague and McCourt (Citation1974) focused on comprehensive planning, public participation, and public interest. Wu (Citation2012) examined the relationship between neighborhood attachment, social participation, and the willingness to stay in the context of low-income communities, which findings showed that the relation between participation in community activities and neighborhood stability is not straightforward.

In China, the Urban and Rural Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China and Measures for Formulating City Planning include urban system planning, city planning, town planning, township planning, and village planning. We recognize that it is necessary to have a change from direct participation to other forms of participation for different scales (Rockloff and Moore, Citation2006). Also, we hypothesize that the interest in public participation may increase if the scale of the plan influences people’s daily lives. In order to explore the effect of the scale of the plan on public participation, we classified spatial scale into four levels from large to small: regional planning, city planning, district planning, and neighborhood planning. Regional planning covers not only cities, but also farmland, military bases, and wilderness; it also includes a metropolis comprising multiple cities. City planning refers to the comprehensive planning of land of a single city whereas the development of socioeconomic targets, scales, and standard for development and construction are determined. District planning is the process of dividing land in a city into different zones within which the land use, population distribution, infrastructure, and public facilities are planned. Neighborhood planning is the most detailed level of planning, mainly involving housing and neighborhood environment.

Attribute 2: Urban Planning Process

The urban planning process involves the policy cycle of urban planning and implementation. The principle of citizen participation states that those whose residential environment is affected have a right to be involved in the whole urban planning process, especially in the decision-making stage. In China, the latest edition Urban and Rural Planning Law in 2007 confirmed its role as the milestone for citizen engagement in planning regulation. Public consultation is manifested in the form of a Public Notice whereby any development proposal has to be displayed on-site and on an official planning website for at least 30 days. In addition, planning authorities need to provide explanations for the adoption and rejection of opinions collected from the public. Obviously, the nature of the process differs substantially by stage. We hypothesize that the interest of the public to participate in urban planning process systematically increases through the increasingly more concrete stages of the planning process. In particular, we expect that interest will be at its maximum at the decision stage.

Attribute 3: Urban Planning Content

Urban planning content is concerned with the development and use of land, planning permission, protection and use of the environment, public welfare, and the design of the urban environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure, such as transportation, communications, and distribution networks. Facing different planning content, studies on public participation also differ in content. Foss (Citation2016) conducted research on environmental planning, pointing out how public participation and cultural framing contribute to sustainability and climate change planning. Researchers studying community involvement have debated whether and how to improve public services and infrastructure (Russ and Takahashi, Citation2013). We hypothesize that people’s interest in participating in urban planning varies by content either because the topic is closer to their profession or because they care more about that topic for a variety of reasons.

Attribute 4: ICT Platform

The ICT platform is considered because online communication comes in many forms. Batty et al. (Citation2012) identified four key ICT modes: portals, professional software, crowd-sourcing systems, and decision support systems. Portals, especially for government and functional departments, are ICT tools that allow users to access useful information. Professional software has the added functionality of processing the information. Previous types of professional software have been strongly supported by the popularity of Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) (Bugs et al., Citation2010), but more recent technologies are more interactive and communicative by web-based implementation such as MySideWalk, PlaceSpeak, CitySourced (Afzalan et al., Citation2017). Crowd-sourcing systems invite respondents to voluntarily answer queries and upload information. The PetaJakarta.org project is an application of crowdsourced data in flood mapping and disaster management (Ogie et al., Citation2019). Decision support systems enable citizens to engage in actual design and planning processes. The Eastern Lake greenway planning project in Wuhan, China is an example of web-based decision support systems. Through this online participation platform, citizens can become involved in the evaluation of planning scenarios (Zhang et al., Citation2019). At the same time, we cannot ignore the influence of popular social media, which offer multi-modal communicative platforms that can supplement traditional methods of participation (Vitak et al., Citation2011). In China, the most popular and important social media platforms include Microblog, Wechat, and Tencent. We hypothesize that people have different awareness, knowledge, and affinity with these different modes, and the platforms used will affect citizens’ willingness to participate in urban planning processes.

Attribute 5: Degree of Online Participation

The degree of online participation is related to the concept of the Ladder of Citizen Participation (Arnstein, Citation1969). The ladder differentiates between different levels of participation, including non-participation (manipulation and therapy), tokenism (informing, consultation, and placation), and citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control). With the development of information and communication technologies (ICT), this concept has been extended. Williamson and Parolin (Citation2012) expressed different levels and degrees of online public participation. The lowest step is passively supporting information and the highest is a system supporting decisions via the Internet. The broadened ladder of e-participation also includes the design by local society and virtual worlds. Such actions may involve more participants—actors of virtual scenes—than system supporting decisions (Hanzl and Planning, Citation2007). Maged and Sarah, cited in Senbel and Church (Citation2011: 425–426), identified the 6-I’s of Design Empowerment to match the typical and continuum design sequence from passive information acquisition, visioning response, and plan design to the end of the proactive process of decision making. The 6-I’s are categorized as Information, Inspiration, Ideation, Inclusion, Integration, and Independence.

Levels

For each of the attributes delineated in the previous section, it is necessary to identify levels/categories. Considering the actual situation in China and measurement scales, four levels were defined for all selected attributes. The urban planning scale factor includes regional scale, urban planning, district planning, and community. The urban planning process factor includes launch and field investigation; planning scheme collection; planning decision; and implementation and monitoring. The planning content considers the environment; infrastructure and traffic; historical and cultural protection; and public services. Moreover, four key modes of interactivity were defined: websites, such as portals and government official websites, which are the most widespread way of receiving information; professional software, with more specific content and background; social media platforms such as Wechat; and microblogs, which are new and booming platforms in the ICT age. For the degree of online participation, we selected information access; online survey; discussion (forum, comments, and feedback); and making decisions (voting). An overview of selected attributes and their levels is provided in .

Table 1. Attributes and levels varied in the SP experiment

Social demographics are also considered in our research framework. The literature shows that the decision to participate in planning processes is often conditioned by certain social characteristics. Results show that education, wealth, gender, and language skills are significant predictors of participation (Fung, Citation2006). In this study, not only the impact of personal characteristics, such as age, gender, occupation, education, and income, etc. is considered; we also examine whether the nature of respondents’ work is associated with their intention to participate.

In the SP survey design, the choice profiles were generated from an orthogonal fractional factorial design in which a fraction of all possible combinations of attribute levels is used. Orthogonality means that the attribute levels are uncorrelated. Because choice alternatives were defined by five attributes, each with four levels, a full factorial design will result in 45=1024 profiles. An orthogonal subset of 128 profiles was generated, allowing the estimation of all main effects, independently of 2-factor interactions. In this study, each respondent answered eight questions which were randomly selected from the 128 hypothetical situations.

The survey was divided into two sections: in the first section, information about social-demographic characteristics was collected. The second section included the SP experiment, in which respondents were asked to express their intention to become engaged in the described planning process. An example of the choice experiment is shown in . This case means that if a respondent has an opportunity to participate in regional planning at the plan launch stage about historical and culture protection through a website, would he/she intend to participate. A 7-point scale was used to measure the intention to participate, where –3 and 3 mean the intention definitively not to participate and the intention to definitely participate, respectively.

Table 2. Example of the SP experiment of the survey

Data Collection

The city of Wuhan was chosen as the study area. Wuhan is the capital of Hubei province, and is recognized as the political, economic, financial, cultural, education and transportation center of central China. It is known as “Jiusheng Tongqu (the nine provinces’ leading thoroughfare)”; it is a major transportation hub, with dozens of railways, roads and expressways passing through the city and connecting Wuhan to other major cities. With fast economic growth and rapid urban development, Wuhan is also one of the most competitive cities for domestic trade in China. The economic prosperity of Wuhan puts high demand on urban land for large infrastructure and housing construction. The issue of urban regeneration and community redevelopment inevitably requires listening to the opinions of residents (Zhou, Citation2018), and demands substantial public participation. Another reason for choosing Wuhan as the study area was because it has outstanding platforms for citizen participation at the forefront of online public participation development in China. There are all kinds of media and platforms of urban planning and management in Wuhan City, ranging from traditional tools (newspapers and TV) to digital tools (websites, software, and social media).

The survey involved two phases of data collection conducted over more than one month. Based on the previous literature, a self-completion, structured questionnaire was developed. First, the draft questionnaire was pilot-tested between 11 and 15 November 2016 among 107 respondents. Based on their comments, the questionnaire was finalized. Next, the final questionnaire was administered to 502 respondents residing in Wuhan City between January 20 and February 10, 2017. A total of 216 fully completed questionnaires was obtained. Based on the orthogonal experimental design, each respondent answered eight questions randomly selected from the 128 hypothetical situations. In total, 1,728 observations were used for estimating the regression model, in which intention to participate is the dependent variable.

The sample’s descriptive statistics, listed in , show that 49.5 percent of the respondents were male and 50.5 percent were female. Respondents aged between 18 and 30 years old represent 23.2 percent of the sample, while 55.1 percent of the respondents are aged between 31 and 60 years, and 21.7 percent are older than 60 years. The education of the majority of respondents (69.7 percent) is lower than an undergraduate degree, and only 30.3 percent of the respondents received a Bachelor degree or higher. also shows that 26 percent of the respondents are administrators and technical staff; 38 percent are clerks or service employees; students and retired respondents represent 26.9 percent; the remaining 9.1 percent is unemployed. Forty-seven point five percent of respondents have work that relates to urban planning, architecture, landscape, or real estate. The majority of the respondents (44.9 percent) have lived for more than five and fewer than 10 years in Wuhan, while only 31.5 percent of the respondents have lived there for fewer than five years, and 23.6 percent of respondents lived in Wuhan for more than 10 years. The majority of the respondents work and live in the city center (79.8 and 75.8 percent, respectively). Most of them commute by public transportation, including bus (21.7 percent), metro (26.3 percent), taxi (2.3 percent), or private car (30 percent). The remaining respondents use bicycle (4.2 percent) or walk (10.1 percent). Because these sample characteristics show the evidence of self-selection, for keeping the descriptive statistical distribution proportion of sample consistent with that of Wuhan, data were weighted using the statistics from the “Statistical communique on the 2015 national economic and social development of Wuhan.”

Table 3. Sample characteristics

Table 4. Regression results of public participation in urban planning

Analyses and Results

Based on the conceptual framework, regression analysis was used to examine the impact of social demographics and the attributes varied in the experimental design on the intention of online participation in urban planning. In this study, we not only estimate the effects of single factors, but also the effects of the interaction between social demographics and the main effects variables. The goodness-of-fit of the model is satisfactory, with an R-Squared of 0.228. Estimation results are listed in .

Result 1: Effect of “Urban Planning” Attributes on the Intention to Participate Online

Few studies have emphasized the relationship between urban planning scale, process and content with public participation from a citizen’s perspective, not to mention e-participation. In our study, all attributes related to “urban planning scale,” “urban planning process,” and “urban planning content,” which influence the intention to participate online are found to be significant (See ).

For the urban planning scale, we consider four scales of area planning (regional planning, city planning, district planning, and neighborhood planning). Since most approaches in participation are appropriate for neighborhoods (Graves, Citation1972), the level of neighborhood planning is defined as a reference. In previous studies, it was found that a large proportion of those participating were grounded in the smaller scale; however that does not mean that it is unimportant for metropolitan regions (Pickering and Minnery, Citation2012). Results show that citizens in general intend to participate more at the scale of city planning and district planning, compared with neighborhood planning, while they are less willing to participate in regional planning. The negative sign related to neighborhood planning, however, is different from the common understanding that assumes the smaller the planning area, the greater the willingness to participate. They have the strongest intention to participate in the city level, which is the area where commuting, work, and entertainment activities occur most frequently, followed by the district planning scale. The unwillingness to participate in regional planning is understandable because planning in regional scales is not directly and closely connected to people’s daily lives.

Regarding the process in urban planning, results show that people prefer mostly to participate in the phase of plan decision. For citizens, the plan decision stage is the most specific and concrete stage and form of empowerment in the whole planning process, and, therefore, it is highly attractive. Results of planning content indicate that people in general prefer to participate in infrastructure and transportation planning, than to participate in historical and cultural protection, also with public service, followed by ecological environment planning. This may be because transportation and infrastructure, which relate to the function and density of land use, are elementary for people’s daily commuting.

Result 2: Effect of Social Demographic Attributes on the intention to Participate Online

Results show that the level of education, length of residence, and commuting by private car have a significant effect on the intention to participate online. Respondents with a higher degree of education, on average, tend to have a stronger intention to participate. This complies with the findings of Hansen and Reinau (Citation2006) who argue that people who have completed higher levels of education are more likely to benefit from e-participation. In addition, the willingness to participate depends on length of stay. Residents who have lived for fewer than five years in Wuhan are more likely to participate. Moreover, people who commute with motorized transport such as public transportation, in general are more willing to participate online, compared to those who travel to work with other transportation modes. It may be that these people have more time to use the Internet during their commutes. Furthermore, the results show that males have a lower intention to participate, but this effect is not statistically significant. Young people seem less interested in participation in urban planning processes, but this effect is also not significant.

Result 3: Combined Effect of “Socio-Demographics” and “E-Participation” Attributes on the Intention to Participate Online

We examined the effects of social demographics on the use of different ICT platforms and the degree of participation (See ). For online participation platforms, workers prefer to use websites and professional software, while others like students and retirees prefer the tools of social media, e.g., Wechat. This is perhaps because students and retirees have more time to use social media compared with workers. Also, respondents holding a job that relates to urban planning are more willing to use professional software and Wechat, while people whose work is unrelated to urban planning are more likely to use normal websites and microblogs. It is reasonable that the use of websites and microblogs is more passive for information reception, and the professional software and WeChat are more active and participatory, which requires more professional knowledge.

Regarding the degree of e-participation, results show that the intention of individuals’ online participation is significantly related to age, income, and education. People who are older and who have higher education levels prefer to participate in planning decisions. Also, respondents who have a higher income are more willing to participate in online discussions. It is not difficult to guess that older people and those with higher education and higher income are more interested in participating in substantive activities in the decision-making stage of planning at the highest level. This may be related to their life experience and social status.

Result 4: Combined Effect of “Socio-Demographics and Urban Planning” Attributes on the Intention to Participate Online

Considering that the effects of urban planning attributes on people’s intention of participating online may vary across people, we estimated the interaction effects between social demographics and urban planning attributes (See ). We found that people who have higher incomes have a higher intention to participate in regional planning and city planning, while low-income people are more inclined to participate in neighborhood planning. This may be due to a wider regional scale of concern among high-income people.

The results of workplace and commuting tools interacting with urban planning scales was consistent. People who work in city center and/or commute with motorized modes are more willing to participate in regional and neighborhood planning, and less in other scales of planning. That may be because they travel farther and have parking needs in the community.

Regarding the stage of urban planning, results show that citizens with different characteristics have a different willingness to participate. Compared with students and retirees and other non-working people, workers are more likely to participate at the stages of plan-making, launch, field investigation, and proposal collection. Moreover, people whose jobs are related to urban planning and people who have higher incomes prefer to participate at the stage of plan decision and plan implementation/monitoring. This is perhaps because those people have already known or participated at the initial stages, and they would like to be involved more in stages related to operations.

The effects of urban planning contents also differ across different citizens. Young people are more willing to participate in historical and culture protection and public service, while older people with higher incomes and who have lived for more than five years in the study area are more likely to participate in ecological environmental planning and infrastructure planning. This shows that older people who live for a long time pay more attention to the material environment (ecological environmental planning and infrastructure planning) and young people and temporary residents take more notice of the cultural environment (historical and culture protection plaining, and public service planning).

Conclusions and Discussions

With ICT development, increasingly more participation services are being offered online. Consequently, people are increasingly adopting ICT tools to engage in activities, which they believe to be more effective and efficient. To explore the potential of e-participation in promoting citizen participation in urban planning processes, it is necessary to better understand the determinants of online participation. Thus, the motivation underlying this study is to examine how much citizens would like to participate online in urban planning. It aims to extend our understanding of the factors affecting the intention of online participation in urban planning. Using a stated preference experiment, this study examines citizen’s willingness to participate online as a function of medium, planning scale, content, and stage.

The results of this study compensate for the lack of literature discussing the factors influencing e-participation in urban planning. The impact of “Urban planning Scale,” “Urban planning process,” “Urban planning content,” “Participation ICT platform,” “Online participation degree,” and “Social demographics” were examined in our study. Results indeed indicate that the intention to participate online in public participation in urban planning varies by scales, stages, and contents and according to socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, income, and occupation. Also, the interaction factors of “Social demographics” and “E-participation (ICT platform/Online participation degree)” have important influence on the willingness to participate. This is consistent with the findings of prior research. There is, however, the extra filter of people's ability to use modern technology (Hansen and Reinau, Citation2006; Kolsaker and Lee-Kelley, Citation2006; Zheng, Citation2017).

This study is a supplement to e-participation literature and helps explain the intention of citizens’ online participation in urban planning. Previous literature and studies paid considerable attention to the traditional qualitative methods rather than quantitative analyses using survey data. Our experimental results demonstrate that not every attribute has a significant effect on the willingness to participate. From a practical perspective, the present study provides implications for the design, development for citizen demand, and motivation to participate. For decision- and policy-makers, the present study would help in building and managing strategic plans for participation, plans that could motivate and enhance an effective and sustainable environment for engagement. Nonetheless, our findings have some limitations. Some sampling biases may have occurred. The percentage of respondents holding a job that relates to urban planning is larger than other types of work. Although this is not a major issue for the current analysis, future studies on the prediction of participation may not skip the weighting scheme as presented here.

There is no denying that public participation may enhance the capacities of citizens to cultivate a stronger sense of engagement, and build trust and effective cooperation between planning authorities and the public. Although there are some successful cases of citizen participation programs in China, citizen participation is still in its infancy. To ensure widespread participation, ICT technologies are becoming important tools that enable citizens to participate in urban planning. Social media platforms are becoming easy channels where individualized opinions can be expressed (Bennett and Segerberg, Citation2012). ICT technology and platforms provide a convenient, open, transparent, and interactive dialogue for the general public, but ICT tools may not entirely replace traditional participation methods, particularly for the groups such as low-income or elderly groups who, as our results show, are distant from the new technologies. Groups of citizens with similar characteristics can easily collect and gather in the network society, which hinders objective appraisal from unusual, minority, or unpopular opinions as a result of crowd pressure, so it’s more important for dependence on qualified leaders and effective cooperation approaches during the whole organization process (Zhao et al., Citation2018). How to integrate both traditional and ICT-based technology into urban planning participation strategies needs to be further studied.

Finally, effective public participation requires that trust be developed throughout the participation process with good communication and commitment. New ICT tools for information dissemination and feedback, have provided more trusted and comfortable communication channels and platforms among users (Stern et al., Citation2009). Anonymity of online participation reduces the risk of undue influence of face-to-face contacts, e.g., gender, age, wealth, and ethnicity. In addition, we also need to pay attention to the influence of different agencies on the trust level of participation, between providing feedback to private consultants or a public agency. In sum, the establishment of e-participation norms could enhance fairness, feasibility, and effectiveness.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on Contributors

Wenshu Li is a post-doctoral researcher at Wuhan University.

Tao Feng is an associate professor in the Department of the Built Environment at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e).

Harry J. P. Timmermans is a professor and chair of the Department of Urban Planning at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Ming Zhang is a professor of community and regional planning in the School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin.

Additional information

Funding

References

- N. Afzalan, T. W. Sanchez, and J. Evans-Cowley, “Creating Smarter Cities: Considerations for Selecting Online Participatory Tools,” Cities 67 (2017) 21–30.

- V. Albino, U. Berardi, and R. M. Dangelico, “Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives,” Journal of Urban Technology 22: 1 (2015) 1–19.

- L. Albrechts, “The Planning Community Reflects on Enhancing Public Involvement: Views from Academics and Reflective Practitioners,” Planning Theory and Practice 3:3 (2002) 331–347.

- S. Arnstein, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35: 4 (1969) 216–224.

- M. Barndt, “Public Participation GIS: Barriers to Implementation,” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 25: 2 (1998) 105–112.

- M. Batty, K. Axhausen, F. Giannotti, A. Pozdnoukhov, A. Bazzani, M. Wachowicz, G. Ouzounis, and Y. Portugali, “Smart Cities of the Future,” European Physical Journal: Special Topics 214: 1 (2012) 481–518.

- W. L. Bennett and A. Segerberg, “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics,” Information, Communication and Society 15: 5 (2012) 739–768.

- D. Booher and J. Innes, “Network Power in Collaborative Planning,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 21: 3 (2002) 221–236.

- S. Boulianne, “Does Internet Use Affect Engagement? A Meta-Analysis of Research,” Political Communication 26: 2 (2009) 193–211.

- G. Bugs, C. Granell, O. Fonts, J. Huerta, and M. Painho, “An Assessment of Public Participation GIS and Web 2.0 Technologies in Urban Planning Practice in Canela, Brazil,” Cities 27: 3 (2010) 172–181.

- A. Caragliu, C. del Bo, and P. Nijkamp, “Smart Cities in Europe,” Journal of Urban Technology 18: 2 (2011) 65–82

- Y. Cheng, “Collaborative Planning in the Network: Consensus Seeking in Urban Planning Issues on the Internet—the Case of China,” Planning Theory 12: 4 (2013) 351–368.

- J. Evans-Cowley and J. Hollander, “The New Generation of Public Participation: Internet-Based Participation Tools,” Planning Practice and Research 25: 3 (2010) 397–408.

- J. Forester, “Planning in the Face of Power,” Journal of the American Planning Association 48: 1 (1982) 67–80.

- A. Foss, “Divergent Responses to Sustainability and Climate Change Planning: The Role of Politics, Cultural Frames and Public Participation,” Urban Studies 55: 2 (2016) 332–348.

- A. Fung, “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance,” Public Administration Review 66: S1 (2006) 66–75.

- A. Fung, “Putting the Public Back into Governance: The Challenges of Citizen Participation and Its Future,” Public Administration Review 75:4 (2015) 513–522.

- C. W. Graves, “Citizen Participation in Metropolitan Planning,” Public Administration Review 32: 3 (1972) 198–199.

- C. Hague and A. McCourt, “Comprehensive Planning, Public Participation and the Public Interest,” Urban Studies 11: 2 (1974) 143–155.

- H. Hansen and K. Reinau, The Citizens in E-Participation (Kraków: Springer, 2006).

- M. Hanzl and T. Planning, “Information Technology as a Tool for Public Participation in Urban Planning: A Review of Experiments and Potentials,” Design Studies 28: 3 (2007) 289–307.

- P. Healey, “Planning Through Debate: The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory,” Town Planning Review 63: 2 (1992) 143–162.

- P. Hemmersam, N. Martin, E. Westvang, J. Aspen, and A. Morrison, “Exploring Urban Data Visualization and Public Participation in Planning,” Journal of Urban Technology 22: 4 (2015) 45–64.M.

- L. Hopkins, “Planning Support Systems for Cities and Regions,” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 25: 2 (2011) 324–325.

- P. Koch, “Bringing Power Back In: Collective and Distributive Forms of Power in Public Participation,” Urban Studies 50: 14 (2013) 2976–2992.

- A. Kolsaker and L. Lee-Kelley, “Citizen-Centric E-Government: A Critique of the UK Model,” Electronic Government: An International Journal 3: 2 (2006) 127–138.

- Lauwaert, “Playing the City: Public Participation in a Contested Suburban Area,” Journal of Urban Technology 16:4 (2009) 143–168.

- J. Minner, M. Holleran, A. Roberts, and J. Conrad, “Capturing Volunteered Historical Information: Lessons from Development of a Local Government Crowdsourcing Tool,” International Journal of E-Planning Research 4: 1 (2015) 19–41.

- R. I. Ogie, R. J. Clarke, H. Forehead, and P. Perez, “Crowdsourced Social Media Data for Disaster Management: Lessons from the PetaJakarta.Org Project,” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 73 (2019) 108–117.

- T. Pickering and J. Minnery, “Scale and Public Participation: Issues in Metropolitan Regional Planning,” Planning Practice and Research 27: 2 (2012) 249–262.

- S. F. Rockloff and S. A. Moore, “Assessing Representation at Different Scales of Decision Making: Rethinking Local is Better,” Policy Studies Journal 34: 4 (2006) 649–670.

- L. W. Russ and L. M. Takahashi, “Exploring the Influence of Participation on Program Satisfaction: Lessons from the Ahmedabad Slum Networking Project,” Urban Studies 50: 4 (2013) 691–708.

- M. Senbel and S. P. Church, “Design Empowerment: The Limits of Accessible Visualization Media in Neighborhood Densification,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 31: 4 (2011) 423–437.

- M. Skoric, Q. Zhu, D. Goh, and N. Pang, “Social Media and Citizen Engagement: A Meta-Analytic Review,” New Media and Society 18: 9 (2016) 1817–1839.

- E. Stern, O. Gudes, and T. Svoray, “Web-Based and Traditional Public Participation in Comprehensive Planning: A Comparative Study,” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 36: 6 (2009) 1067–1085.

- J. Vitak, P. Zube, A. Smock, C. T. Carr, N. Ellison, and C. Lampe, “It’s Complicated: Facebook Users’ Political Participation in the 2008 Election,” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 3 (2011) 107–114.

- H. Wang, Y. Song, A. Hamilton, and S. Curwell, “Urban Information Integration for Advanced E-Planning in Europe,” Government Information Quarterly 24: 4 (2007) 736–754.

- W. Williamson and B. Parolin, “Review of Web-based Communications for Town Planning in Local Government,” Journal of Urban Technology 19: 10 (2012) 43–63.

- F. Wu, “Neighborhood Attachment, Social Participation, and Willingness to Stay in China’s Low-Income Communities,” Urban Affairs Review 48: 4 (2012) 547–570.

- L. Zhang, S. Geertman, P. Hooimeijer, and Y. Lin, “The Usefulness of a Web-Based Participatory Planning Support System in Wuhan, China,” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 74 (2019) 208–217.

- T. Zhang, “Urban Planning Theory and Reform in China’s Economic Transition,” City Planning Review 32: 3 (2008) 15–24.

- M. Zhao, Y. Lin, and B. Derudder, “Demonstration of Public Participation and Communication Through Social Media in the Network Society Within Shanghai,” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 45: 3 (2018) 529–547.

- Y. Zheng, “Explaining Citizens’ Usage: Functionality of E-Participation Applications,” Administration and Society 49: 3 (2017) 423–442.

- Z. Zhou, “Bridging Theory and Practice: Participatory Planning in China,” International Journal of Urban Sciences 22: 3 (2018) 334–348.