Abstract

This article critically examines the way in which the legitimation of emerging artists occurs in the digitalized art market. Based on a conceptual specification of intermediaries’ practices in the legitimation process, we have conducted a case study of Saatchi Art, a pioneering digital platform for trading artworks. We perform a deductive analysis of introduction, interpretation, and selection of artists based on a variety of qualitative data. Our findings show that the legitimacy of selected artists is constructed mainly by Saatchi Art’s curatorial programs. The exclusive practice of granting legitimacy to selected artists by curators stems from symbolic capital- that has accumulated from their career in the conventional art market, thus, implying a close linkage between the offline and online art worlds. Therefore, the disintermediation that is initiated by the digital art platform gives rise to reintermediation due to the necessity of interpreting and endorsing the uncertain value of contemporary artworks and artists.

Introduction

The rapid growth of the Internet has had a significant impact on the field of visual art. It has transformed the dissemination and consumption of art through the diffusion of virtual curation and trading. The advanced digital technology and increasing familiarity with e-commerce have contributed to overcoming technical obstacles for viewing and transactions (Horowitz Citation2012) and reduced the traditional requirement of tangible interactions between artwork buyers and sellers (Velthuis and Curioni Citation2015). As the digitalized art market matures (Lee and Lee Citation2019), the online sale of artworks has continuously grown since 2013 (Hiscox Citation2019).

Although the increasing use of digital platforms raises “a presenting and pressing issue” for academics (Alexander and Bowler Citation2014, 15), the digitalization of trading artworks has not been fully explored in previous research (Lee and Lee Citation2017). While Khaire (Citation2015) analyses three firms that use digital platforms to trade established artists’ works, she has overlooked their effects on young and emerging artists. Lee and Lee (Citation2019) address this issue by examining the perception and behavior of users (both buyers and visitors) in digital art platforms, while constructing the meaning and value of artworks. Responding to their call for research that focuses on other types of users of digital art platforms, this study pays more attention to artists’ experience in order to understand the institutional mechanisms for legitimation in the online art market.

In general, trading goods online facilitates direct transactions between sellers and buyers. Technological innovations make it possible to replace traditional intermediaries who support transactions with better and more efficient methods of transaction support, which results in disintermediationFootnote1 (Evans and Wurster Citation1997). Disintermediation or “cutting out the middle man” (Katz Citation1988, 30) is a controversial concept for some scholars (Bakos Citation1998; Sarkar, Butler, and Steinfield Citation1995) as intermediary relationships will always exist in some form or another (Sen and King Citation2003) with the emergence of new intermediaries. In some cases, reintermediation takes place when a player that was once disintermediated becomes an intermediary again (Chircu and Kauffman Citation1999). The digital marketplace for artworks is also subject to the debate between disintermediation and reintermediation (Lee and Lee Citation2019; Piancatelli, Massi, and Harrison Citation2020). However, the intricate cycle of intermediation, disintermediation, and reintermediation in the art world as a result of the emergence of digital platforms has not been fully explored. Thus, this study attempts to analyze the process by focusing on the legitimation of artists in digital platforms.

Indeed, the inherent characteristics of contemporary artworks do not allow any objective criteria of valuing them (Alexander and Bowler Citation2014). It is hard to judge the value of artworks based only on their beauty (Danto Citation1964), or the artists’ labor or economic value of the materials used to make them (Peterson Citation1997). Accordingly, contemporary artists seek legitimation, which is “a process that brings the unaccepted into accord with accepted norms, values, beliefs, practices, and procedures” (Zelditch Citation2001, 9) in order to attain valuable status for their artworks, which in turn necessitates intermediaries’ practice in the market by offering access to consumers (Currid Citation2007; Hirsch Citation1972). However, there is scant research on the changing role of intermediaries in legitimating artists in the context of digital platforms. To address this gap, this article raises two important questions, namely: (1) what are the institutional mechanisms for legitimizing artists in the digitalized art market; and (2) how do they differ from those of the conventional art market?

We attempted to address these questions by analyzing the role of digital platforms in shaping the legitimacy of young and emerging artists who are in the early stage of their artistic career, without having established a solid status and exclusive gallery contract (Delacour and Leca Citation2017). By critically examining previous research on market intermediaries such as dealers (Wijnberg and Gemser Citation2000; Peterson Citation1997), art fairs (Lee and Lee Citation2016; Morgner Citation2014), appraisers (Lizé Citation2016; Acord Citation2010; O’Neill Citation2007), and their relationships (Becker Citation1982; Bourdieu Citation1996), we conceptualized the legitimation process in the art world with particular attention to the salient role of curators. We conducted a case study of Saatchi Art, which is a pioneering digital platform for trading artworks by young and emerging artists, and performed a deductive qualitative analysis of the legitimation process based on a variety of data that were collected from direct observation, documentary review, and interviews.

Saatchi Art was launched in 2006 by Charles Saatchi, an influential collector in the art world, in order to offer a virtual space for artists to disseminate their artworks. It was re-launched in 2008 as an e-commerce platform. Since changing its ownership from Saatchi to the Leaf Group in 2014, the platform has gradually expanded and currently shows 1.4 million artworks by 94,000 artists (Hiscox Citation2020). The platform not only enables artists to sell their artworks directly to global collectors for a 30% commission of the original price, but also allows first-time buyers or serious collectors to meet various artists upon payment of a modest fee.

Our findings show that the legitimacy of selected artists is constructed by introduction, interpretation and selection of artists that are embedded in Saatchi Art’s curatorial programs. The exclusive practices of granting legitimacy to selected artists by its curators thus implies a close link between the offline and online art worlds. Therefore, we argue that disintermediation initiated by the online art platform necessitates reintermediation due to the necessity of interpreting and endorsing an uncertain value of contemporary artworks and artists.

Theoretical background

The value of contemporary art is uncertain and difficult to judge (Samdanis and Lee Citation2019). In a broad sense, cultural goods, including paintings, music, and designer clothes are inherently driven by consumer taste, rather than their function or utility. Thus, “what makes ‘good art’ (popular or elite) is seemingly arbitrary” (Currid Citation2007, 386). Consequently, there are no objective or widely acknowledged criteria to determine artworks’ esthetic value (Alexander and Bowler Citation2021). In particular, the valuation of contemporary art becomes more complex as contemporary artists may intentionally stress the underlying idea of the work, rather than its beauty (Danto Citation1964). The artwork, then, requires interpreters or educators (Joy and Sherry Citation2003) to explain its value which is legitimized by a layer of intermediaries called the art world.

The concept of the art world is originally devised by Danto (Citation1964) who highlights the role of critics in legitimizing objects as artworks. However, Danto’s esoteric valuation language disregards practical considerations that are necessarily involved in identifying the art world’s constituent elements. Unlike Danto, Becker (Citation1982) insists that critics constitute only a part of a critical evaluation network in the art market. While defining the art world in terms of network relationships, he suggests that the unstable consensus of judging artworks emerges through the collective actions of the art world’s inner members. Depending on their consensus, legitimacy may or may not be conferred to artworks and artists (Zelditch Citation2001).

Becker’s art world is similar to Bourdieu’s (Citation1996) field of art in the sense that they commonly perceive artists who are constrained by social structure and conventions (Alexander Citation2003). Both the art world and the field of art refer to the same sociological phenomenon of relationships, while delineating the realm that encompasses art. However, the significant difference between Becker and Bourdieu lies in explaining the power relations among social actors. Becker focuses on social networks that mediate the collaboration within the art world, whereas Bourdieu highlights the conflicts among field members in their competitive search of capital.

Legitimation in the art world

Bestowing the legitimacy of value on artworks occurs via intermediation between artists and consumers (collectors or appreciators). It commences with introducing artists and their artworks to buyers (or the public) and other intermediaries who comprise the consecration mechanism in the art world. Dealers and gallerists are chiefly in charge of conducting the introduction of discovered artists by organizing their exhibitions. Historically, after the 18th century, Salons or official exhibitions by French academies were the main contributor to débuting artists, which were gradually replaced by dealers with the appearance of innovative artworks by Impressionists (Wijnberg and Gemser Citation2000; White and White Citation1993). Since the 19th century, dealers and gallerists have become the focal point for discovering and introducing artists (Crane Citation1989; Moulin Citation1987). The identification of artistic talent is not only difficult, but also competitive among dealers (Peterson Citation1997). More recently, art fairs and biennales have also emerged as key players in introducing or discovering artists by establishing their curatorial programs (Lee and Lee Citation2016).

Introduction allows intermediaries to insert selected artworks in the mechanism of legitimation. Due to the overabundance of artists, such introduction to intensify their presence in the art world is crucial especially for young and emerging artists. However, it is hard for them to bolster awareness of their existence only with their own actions, which makes them seek the discovery and introduction by intermediaries.

Interpretation contributes to the instruction of collectors and other intermediaries on how to understand the meaning and value embedded in artworks. Interpretation practices embrace the direct engagement of “appraisers-prescribers” (Lizé Citation2016, 36) in constructing the artworks’ esthetic discourse. Critics are representatives who delineate the instruction of intermediaries and place artworks or artists in the history of art, although their influence has been weakened because of the increasing commercialism in the art market (Crane Citation2009). Thus, transforming an ordinary object into a work of art depends on critics’ theoretical interpretation in which the conceptions and intentions behind the artwork are manifested (Danto Citation1964).

Moreover, a wider audience is able to receive indirect instructions on the value of artworks from the collective arrangement in exhibitions. In a group show, the context in which a single artwork is regarded is often the setting in which the next is perceived (Morgner Citation2014). The role of curators is stressed in the process of allocating artworks in an exhibition; they not only display artworks in a certain space but encourage active engagement with artworks by offering interactive spaces to spectators. Such cultural mediation (O’Neill Citation2007) helps viewers construct their own interpretation about artworks. By organizing intangible themes and tangible interfaces in an exhibition, curators contribute to fabricating “artistic meaning” (Acord Citation2010, 447). As exhibitions are central to delivering the meaning of the art, the role of curators in framing indirect beliefs about artworks has become significant in the art world.

The layer of thick intermediaries in the art world selectively endorses the validity of few artists or artworks over others. The legitimacy of selected artists is granted by their selection activities, stressing a particular way of understanding their artworks. Artwork legitimation has been previously specified in terms of the introduction and interpretation practice of intermediaries. This article adds intermediaries’ selection practices as introducing and interpreting artworks that presupposes their selection. According to Bystryn (Citation1978, 393), the “initial screening of potentially successful artists” occurs to introduce artists to the art world or the public. As the art world is comprised of diverse artists and artworks, and invites numerous and competing interpretations by intermediaries, the overflow of discourses is hardly conveyed to consumers in the market. Rather, only the intermediaries as gatekeepers can deliver their filtered or selected information to a wider audience. (Hirsch Citation1972; Currid Citation2007).

The extent to which gatekeepers influence the legitimacy of new artists is unbalanced. Becker (Citation1982, 227) has highlighted that the legitimacy of valuable artworks is bestowed according to “the ability of an art world to accept it and its maker.” Such ability of intermediaries resides in their reputation and symbolic capital. According to Bourdieu (Citation1994, 8), “symbolic capital is any property (any form of capital whether physical, economic, cultural, or social) when it is perceived by social agents endowed with categories of perception which cause them to know it and to recognize it, to give it value.” In the art market, intermediaries’ fame or symbolic capital, which is constructed based on their wealth, social status, and cultural taste, is considered a sign of trust (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016). Thus, their accumulated symbolic capital influences the process legitimizing artists with varying degrees.

Distinctive features of legitimation

The legitimation of artists rarely relies on a single entity, but rather on collective actions taken by various intermediaries. Appraisers’ justification of artwork interpretation contributes to legitimizing their meaning and value. Becker (Citation1982, 131) has delineated the aesthetics’ role in validating particular artworks, as well as highlighting their “explications of what gives [artworks] that worth.” However, the justification of such explications resides in the struggle (Bourdieu Citation1993) or cooperation (Becker Citation1982) among cultural intermediaries. For instance, a newly unveiled work of art is rarely, if ever, completely new, as it is typically based on previously established artistic conventions (Becker Citation1974) that are used to simplify the coordination of collective action. When artists break completely with prevailing conventions, it could result in the decrease of circulation of their works despite an increase in their freedom (Joy and Sherry Citation2003). Whether following or breaking artistic conventions (Bottero and Crossley Citation2011), unveiling artworks requires the support of multiple intermediaries to attain their legitimacy.

Moreover, in the field of art, different degrees of legitimacy are bestowed on artists and artworks, depending on who or which event selects them. The impact of intermediaries’ symbolic capital on legitimation is not ambiguous (Lee and Lee Citation2019). According to their relative status, the decision on which artists and artworks are selectively introduced and interpreted is more acceptable to other intermediaries. For instance, artists’ career after exhibiting artworks at the Venice biennale do not guarantee the same level of economic success to all presented artists as the participation in national pavilions is not as prestigious as being invited to the Palazzo which is curated by renowned judges (Rodner, Omar, and Thomson Citation2011). Thus, artists could attain a diverse level of legitimacy, according to intermediaries’ status.

The process of legitimizing artists also contributes to constructing the legitimacy of intermediaries. By accepting a story about artists, which is proposed by certain intermediaries, the story could be considered as a consensus in the art world. Accordingly, certain intermediaries are able to gain or retain their legitimacy. In this sense, Bourdieu (Citation1991, 166) pointed out that “symbols make it possible for there to be a consensus on the meaning of the social world, a consensus which contributes fundamentally to the reproduction of the social order.” Therefore, the hierarchical ordering among art insiders becomes unequivocal through the process of legitimizing artists.

Research design and method

We have conducted a single instrumental case study through the use of a qualitative research method (Stake Citation1995). Based on purposive sampling (Merriam Citation1998), we have chosen Saatchi Art as a case for the analysis of legitimizing young and emerging artists in the digitalized art market. It is the only platform that represents artworks by young and emerging artists which is included in the top 10 of digital art platforms according to Hiscox (Citation2019). Moreover, its founder Charles Saatchi is influential in the conventional art world who established the Young British Artists (YBAs) by collecting and trading their works and curating several group shows (Hatton and Walker Citation2003). Despite its change of ownership in 2014, Saatchi Art has still kept the name of Saatchi, implying the intentional reputational spillover between the offline and online art world.

The data collection was based on direct observation, documentary reviews, and interviews. First, we observed Saatchi Art for six months, starting from October 2015, by focusing on relevant indicators, such as its curation methods, artists’ biographies, blog texts, and current and past events on the platform. The visually and textually recorded data from the observation is supplemented by reviewing secondary sources such as academic journals, magazines, newspapers, and books. Finally, we conducted 27 interviews with artists in order to capture their experience with and opinions about Saatchi Art.

Potential interviewees were selected through two filters, namely: (1) artists who had been introduced by Saatchi Art in their curatorial programs; and (2) artists who are working in the United Kingdom (UK). The filtering was important in identifying informative interviewees for this study since it influences the quality of data analysis (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). The curatorial practice in the first filter refers to Saatchi Art’s periodic events to promote artists on the platform, who are our target interviewees. It selected artists through an art competition called “Showdown,” a weekly selection of artists called “Features” (“One to Watch Artists” and “Inside Studio”), and a quarterly selection of a group of artists called “Invest in Art.”

As Saatchi Art is an active platform, the potential interviewees who satisfied the first filter had gradually increased due to the update in their curatorial practices. Thus, this study set December 2015 as deadline to confirm the list of 482 artists. The application of the second filter reduced the number to 106 artists. By sending out invitation emails, followed by two reminders, we have undertaken 27 interviews. We gave the interviewees the options of face-to-face or email interviews to increase their chance of participation. As a result, we managed to obtain a rich textual data from seven face-to-face and 20 email interviews. The average age of the interviewees is 35 years and they are still in a relatively early stage of their artistic career (average of 6 years) without being exclusively represented by offline galleries. summarizes the demographic and career backgrounds of the interviewees.

Table 1. Artist interviewed via face to face and email.

Our face-to-face, semi-structured interviews (Dunn Citation2005) were conducted in “a conversational manner” (Longhurst Citation2016, 143), guiding interviewees with the help of pre-established questions. The development of interview questions was initially drawn from our theoretical framework. The questions further evolved according to the outcome identified by direct observation and evaluation of secondary sources about Saatchi Art.

Each email interviewee had roughly two weeks to respond to the questions. Collecting data by email interviews could lead to misinterpreting the questions. To overcome this, the interviewer exchanged multiple emails with interviewees by asking several follow-up questions when “clarifications, illustrations, explanations, or elaborations” (Meho Citation2006, 1293) were required (e.g., clarifying the intention or meaning of what they wrote). These multiple communications have provided richer data for this research.

A deductive content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) is employed in which the analysis of the data is initiated with a review of previous literature. As we addressed the issue of legitimation of young and emerging artists and their artworks in a digital platform, three themes were identified, namely: the necessity for legitimation, the process of legitimizing artists, and the effects of the legitimation. We also pointed out that the data analysis was iterative and interactive as it systematically compares the suggested categories and data (Eisenhardt Citation1989).

The case of Saatchi Art

The context of emerging digital platforms in the art world

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a major shift to online events and contents in terms of the display and sales of art, intensifying the digital transformation of art organizations and institutions. Due to continuing social distancing and lockdowns, many art fairs, festivals, galleries, and auction houses around the world have replaced their offline events with digital initiatives and interactive contents, resulting in an upsurge of the online art market (Hiscox Citation2020). Even before such significant uplift in online market sales due to COVID-19, the online art market has noticeably grown and matured in the past 10 years (Lee and Lee Citation2019). Such growth is driven by three types of digital platforms, namely: (1) using the internet for selling artworks by traditional intermediaries; (2) converting the conventional art market into a digital environment by new entrants; and (3) offering a new business model, such as renting and sharing artworks.

Three representative platforms, as summarized in , belong to the second type, which includes gathering offline galleries in virtual space (Artsy), publicizing online data for sales of artworks at various auction houses (Artnet), and connecting artists and buyers (Saatchi Art). Digital platforms for artworks have seemingly resulted in the democratization of the traditional art world, as characterized by the information asymmetry between artists, intermediaries, and consumers (Noël Citation2014). Offline, artists and collectors rely heavily on intermediaries, particularly dealers, to seek information about price fluctuations, market trends, and artwork evaluation. However, the web’s democratic features enable users to freely create and access these kinds of information on the Internet (Horowitz Citation2012). Echoing the similar goals of said platforms, Artsy, Artnet, and Saatchi Art have publicized free editorial resources about artworks, artists, and the art market, contributing to the free flow and use of information about art. In a broader sense, the decentralization of authoritative knowledge about artworks by digital platforms enabled the erosion of the hierarchical order in the brick-and-mortar art market (Bloom Citation2006).

Table 2. Comparison between three online art platforms.

Curatorial practices of saatchi art

Saatchi Art offers an unparalleled selection of approximately 1,100,000 original artworks by over 74,000 artists from across the globe (Hiscox Citation2019). Its 2019 revenueFootnote2 increased to 29% year-over-year, from $12.2 million to $15.8 million (Leaf Group Citation2020). Its revenue stream includes commissions (30%) on sales from original works.

The platform was originally noncommercial and founded by Charles Saatchi in 2006. A former advertising mogul, Charles Saatchi exemplifies the branded collector. He is a major contemporary art market player (Freeland Citation2001; Rodner and Kerrigan Citation2014; Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016), embodying multiple roles as dealer, gallerist, and collector. He describes unknown artists’ situation, which motivates him to initiate the website in 2006:

The great majority of artists around the world don’t have dealers to represent or show their work. It makes it pretty well impossible to get your efforts seen, with most dealers too busy or too lazy to visit studios… (Saatchi Citation2012, 68)

In 2008, the website turned into an e-commerce platform after being acquired by Leaf Group, an American media company focusing online business. Its name, however, was kept despite absence of the renowned collector.

Saatchi Art presents a collection of artists’ personal pages on which the artists themselves provide digital images of their works with descriptive details (i.e., size, material, and explanation). It also provides a space for artists to publicize their biographies, including their educational background, exhibition lists and inspiration for creation. Artists are also able to set their own price and consumers may buy the artworks according to their preference. However, as most of Saatchi Art consumers are inexperienced (Lee and Lee Citation2019), it is difficult for them to make a purchasing decision on the platform. To help buyers, as we can see in , Saatchi Art has established several curatorial programs that recognize a limited numbers of artists on its platform.

Table 3. Curatorial practice on Saatchi Art.

The “One to Watch Artists” feature highlights a single artist while showcasing a selection of suitable artworks and publishing their interview transcripts. A similar concept is “Inside the Studio,” which introduces certain artists with a focus on their artistic environment and working procedure. Regarding giving more information about artists, Saatchi Art states:

…Wouldn’t it be great to actually see that this is the idea that the artist has and this is a work in progress here to finish? You can see what their environment is like, when they are making the work, what the inspiration is, and what’s on their wall at their studio. I think that is another thing that is really, very interesting for collectors… (Wilson Citation2013)

“Showdown” is a virtual arts competition sponsored by Saatchi Art which is open to artists all over the world as long as they register on the platform. Nineteen contests were held between 2010 and 2015, and includes publishing the nominators’ works and awarding the prizes in the offline exhibition. Moreover, Saatchi Art’s professional team has organized a virtual group exhibition, called “Collections,” in which curators select and gather digital images by various artists within diverse themes.

Disintermediation and the necessity for legitimizing artists

Saatchi Art is a digital platform that engenders disintermediation in the art market. Across various industries, digital disruptions cause disintermediation, “allowing manufacturers to switch or eliminate intermediaries whose added costs may exceed the value they provide” (Gielens, Benedict, and Steenkamp Citation2019, 367). Disintermediation offers registered Saatchi Art artists to eliminate conventional mediators between them and buyers. Thus, artists might increase their profit by reducing commission for sales from 50% to 30%. More importantly, disintermediation enables the registered artists to place their artworks in the valuation system without mediators, which scarcely occurs in the conventional art market.

To validate their works, artists need to be discovered and introduced by dealers or gallerists in the offline art market (Peterson Citation1997). However, only a tiny percentage of artists who have the chance to present their works in galleries can meet their prospective buyers, as “[b]rick and mortar galleries are great but most have a local clientele and you’d be lucky to show your work once a year” (SAATCHIART 2015b). The situation is even worse for unknown artists:

I suppose the major constrains for emerging artists are the difficulties of finding or approaching gallerists, and having the opportunity to sell and exhibit with the appropriate gallery and dealer. [Lily]

It is harder to find spaces to exhibit that you do not have to pay for. It is also harder to be part of group shows, unless they are organised amongst peers, as galleries are more likely to show more established artists. [George]

Saatchi Art aims to support artists and allows them to upload their works without being exposed to limitations in terms of their career-stage or quality of artworks on the site. A sculptor responded positively to such a democratic entry system,

One of the best things that Saatchi Art offers is that it opens the door to anyone who has the slightest tiniest bit of creativity, without judging, without being selective and it allows you to put whatever you want to put under the name of art and make the person out there have the choice of what they want to buy. [Jack]

Based on the unique characteristics of contemporary artworks, the uncertainty of the quality of goods on Saatchi Art has increased as the artworks are produced by young and emerging artists with unestablished reputations. Hence, the discourse on the value of the artworks on Saatchi Art is lacking, which challenges potential buyers. Moreover, this uncertainty is even higher in the online art market, which relates to the democratic filtering system on Saatchi Art. It is obvious that the artists have more chance of exposing their works as the participants of our research have pointed out. However, despite their positive comments to the effect that anyone could upload their work on Saatchi Art, the artists also acknowledged that art of poor quality was also displayed there. That is,

I may stand out on the platform but that’s because there is no filter for quality. Anyone can post images so there’s lots of very poor art on the site. [Isla]

It is accessible to anyone. This means there is a lot of bad ‘art’ on Saatchi Art… which might put some people off. [Isabella]

The environment where artworks are presented is important, and the combination of works displayed together is highly relevant to artists and collectors alike. Without filtering the good from the bad, Saatchi Art allows every artwork to be publicly exhibited. Our respondents have commented that the lack of a filtering system on Saatchi Art intensifies the difficulties of buyers to discover and value artworks:

Unlimited upload is perfect, and good for everybody, but it also means that the site becomes so filled with so much art that the chances of finding this or that artist becomes smaller. [Lily]

I think it is right that this is reflected on Saatchi Art where anyone is able to upload any type of artwork. However, this ‘anything goes’ attitude has the potential to undermine value judgement. [Sophia]

In other words, both good and poor artworks may appear on the same screen, which even discouraged an interviewee from continuing to use Saatchi Art:

I have actually stopped using Saatchi Art. At the end of 2014, I started to pull back. Because I don’t feel that they have a very strict filter system… And I want to be seen in the right group. [Sophie]

The lack of regulation for sellers in terms of the quality of their products on Saatchi Art allows too many artworks on the platform. Their democratic filtering system increases the uncertainty of the value of the artworks displayed. While such a volume and diversity of work can give user autonomy, most buyers—who are non-experts—have difficulty in judging their value.

Disintermediation and the democratic entry system on Saatchi Art leads to the reintermediation of online trading relationships over time. The artworks on the platform have inherently uncertain value (Samdanis and Lee Citation2019) which results in the necessity for justifying their value by intermediaries. Excluding such intermediaries in Saatchi Art, the legitimacy of the artworks is hardly secured. Moreover, its democratic filtering system challenges both artists and buyers, putting more weight on the necessity of reintermediation to legitimize artists and artworks on the platform.

Legitimation of artists on Saatchi Art

Introduction

Saatchi Art introduces artists to a wider audience. We have pointed out that there are two levels of introduction there. First, the aforementioned argument about disintermediation that is triggered by Saatchi Art is related to the first level of introduction. Saatchi Art contributes to “generating awareness of the existence of the entire range of works available in the market; not having vested interests” (Khaire Citation2015, 118). Hence, Saatchi Art’s role is just to provide a digital platform or marketplace. In such introduction to Saatchi Art, we need to focus on who introduces artworks. In an offline art market, the artist needs to be discovered and introduced by dealers or gallerists. In contrast, they can independently introduce their artworks in an online art market. Thus, Saatchi Art’s role in introducing artists on this level is ancillary and limited.

Another level of introduction in Saatchi Art is reintroduction. It selectively reintroduces artists who have already introduced themselves on the platform. Through its curatorial practice, such reintroduction plays a similar role to that of dealers who discovered and introduced artists in the offline art market. Such reintroduction contributes to helping potential buyers’ choice, as well as allowing the selected works to insert “into [the] art world’s taste-making machinery” (Velthuis Citation2005, 41). In other words, Saatchi Art’s reintroduction gives artists potential opportunities to increase their artworks’ value. An artist based in London described the effects of being featured as not only an increase in sales, but also the construction of a new network:

… I started selling my work more regularly…And, I got to know other artists and kind of made links with artist who are also on Saatchi Art. They started following me on Twitter and commented on my works. That is kind of obvious networking. [Alice]

A broadened network potentially leads an artist to exhibit her works, which can contribute to her recognition from others in the offline art market. Similarly, an interviewee considered the sizeable increase of visitors on his personal homepage to be the biggest change after winning a prize in Saatchi Art. Indeed, various media outlets, dealers, and galleries have paid attention to Saatchi Art. An interviewee revealed how a gallerist acknowledged the recognition on the online platform:

Some other things, I could see, was, for example, one gallerist who was already in contact with me saw ‘Invested in Art’. She said like ‘oh, you are featured’. And then, maybe she became more confident in me because somebody is also noticing me. [Sophie]

In addition, some dealers and galleries use the platform to discover new artists. A German artist said, “I also got offers for Residencies, Press and exhibitions all from the exposure with Saatchi Art” [Amelia]. Hence, exposing artists in the curatorial program on Saatchi Art opens up a variety of opportunities for selected artists:

I found that I got a lot of exposure via people’s blogs and lots of other ‘art selling’ websites getting in touch, wanting to have my work there. And some exhibition opportunities (nothing major). Also art print sites wanting me to sign up. [Emily]

… I received a fair few invitations, and many of the approaches were indirectly or directly through Saatchi Online. I know that a lot of gallerists are browsing the site and are looking for new artists, and I was contacted by some gallerists after they have seen my work on Saatchi. [Charlotte]

Based on our data, likewise, interviewees revealed that they had various and new opportunities after being introduced by Saatchi Art, such as offers for residency, exhibitions, collaboration, and others. This shows that the platform plays a role in introducing artists to other intermediaries in the art world.

Interpretation

Saatchi Art shapes the legitimacy of selected artists and artworks through its practice of interpretation. It instructs consumers on how to interpret the meaning of presented artworks. Constructing such instruction contributes to rendering selected artists and artworks as more suitable for pre-established norms and values in the art world. In the offline art market, the direct interpretation of an artwork is mainly offered by critics in order to confer the rationales for positing an history on the artwork (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016).

Such direct interpretation is also available on Saatchi Art through its curatorial practice. For instance, the articles in “One to Watch Artists” begin with a brief interpretation by its curators as they try to construct the esthetical discourse about the artists’ artworks with limited critical reviews. Along with such text, artists’ interview is also available in which they express themselves through answering questions such as the process, major themes, and inspiration of creating their works, and their next artistic project. These interviews can make users understand more about the artists and their artworks. By doing so, the interpretation through sharing knowledge about artworks (Khaire Citation2015) occurs via curatorial practices.

By exhibiting a group of artworks virtually, Saatchi Art also delivers indirect interpretation about artworks to a wider audience. In a group exhibition in a brick-and-mortar gallery, there is a close link among displayed artworks as “[a]rtworks are not viewed in isolation, but rather in the context in which the next one is viewed” (Morgner Citation2014, 43). Thus, it is important for artists to display their works in the right place as it disseminates the indirect interpretation about them. Saatchi Art offers indirect interpretations via the “Collections,” based on selecting artworks. As this virtual group exhibition occurs with certain principal curators, a compilation of artworks indirectly shares its esthetic discourse with the audience. However, gathering digital images of artworks in the “Collections” provides less knowledge about the artworks than offline exhibitions. Indeed, curators of a group exhibition in brick-and-mortar galleries consider a variety of physical factors that engage artworks and visitors such as the flow of visitors’ traffic, light controls, and work arrangement. By doing so, curators contribute to reconstructing, highlighting, and interpreting the meaning of artworks (Acord Citation2010). The digital environment delimits such curator activities, thereby delivering less esthetic instruction to users.

During the interview, a painter pointed out that her works being shown in the “Collections” was not significant compared to other curatorial programs:

The collections are an interesting way of being promoted. However, they have a much smaller influence on sales compared to the ‘invest in art’ or comparable features. [Amelia]

This smaller influence comes from the characteristics and frequency of the “Collections,” that is, this curatorial program does not focus on a single artist, but introduces a group of artists, which disperses its influence. Moreover, the “Collections” is more frequent than other “Features.” For instance, there are five average “Collections” every week compared with the “One to Watch Artists” and the “Inside Studio” which are once every week. For these reasons, an interviewee criticized the “Collections”:

It is quite frequent. I do not think that is so random, but it’s just a bit too frequent. And then, it does not do anything to me. It’s basically them telling to collectors, but themes are very general. So, you want colours and abstractions you want festivity… and then you get into a collection. [Sophie]

As one of our interviewees pointed out, apart from its frequency, the themes of the “Collections,” such as gathering artworks according to its materials, prices, styles, and so on, are too general. Without defining the persuasive reason for gathering digital images, the virtual group exhibitions do not deliver the collective storyline which occurs in offline group exhibitions. As a result, the indirect interpretation about the selected artworks via the “Collections” is not significantly influential in shaping the legitimacy of the artworks.

Selection

Selecting artists through Saatchi Art’s curatorial programs is the focal ritual of bestowing legitimacy upon its artists as the selection leads to reintroduction, and direct and indirect interpretation activities within the platform. In other words, after selection, the artists gain opportunities to introduce their works to users or instruct them how to interpret the meaning of artworks, which contributes to shaping the legitimacy of the selected artists.

In Saatchi Art, the gained symbolic status on the selected artists translates into economic capital (Rodner and Kerrigan Citation2014). The increase in sales for some interviewees after being included in its curatorial program shows an instant translation from Saatchi Art’s recognition to its economic value in the market. Some artists who were featured in a Saatchi Art curatorial program haver noted that the sales of their artworks on the platform immediately increased. For instance, one of our informants shared his experience of the dramatic change of his status after he was featured in an artistic competition:

Obviously a huge interest in my work on the Saatchi platform, followers and sales would follow any new feature, especially the Showdown. The impact of having myself and the work featured was nearly immediate. [Harry]

After being included in One to Watch Artists I noticed the number of followers increased as did sales. Similarly, when I was awarded a second prize at Saatchi Showdown with the piece, I saw an increase in followers and a rise in sales. The piece that I entered in Showdown was purchased shortly after the competition. This piece also has the most views at over 12,000. [Mia]

A lot…I mean I sold nine pieces on Saatchi after winning the prize. Nine already and it has only been two months. These are big originals and they are not like small pieces. Privately, I sold about five or six and three were my biggest pieces. [Charlie]

One of our informants provided a document that records the artwork sales on Saatchi Art, which is reproduced in . It clearly shows the positive influence of its curatorial practices on the value of the artworks. The number of sales increased considerably after the artist was featured in “Invest in Art” in February 2014. Before this, the artist had sold only one original artwork, whereas she sold eight within six months after that February. The number of sales then returned to normal, which shows that Saatchi Art’s curatorial practice instantly affects the sales of artworks by the selected artists. Likewise, some of our interviewees shared that they made sales or generated more interests from the public after being introduced in “Features”:

Table 4. An example of the sales record of a featured artist on Saatchi Art.

I think these opportunities [for being featured on Saatchi Art] impresses the buyers and give them confidence. I have made sales through these on occasions. [Lily]

Saatchi Art curates art in the sense that they’re constantly hand-picking featured artists and collections, so buyers can look at and buy things ‘approved’ by Saatchi Art if they prefer to have that security. [Emily]

After having featured in [a curatorial program], I have experienced a flow of interest in my work, both amongst a new audience but also amongst my current clients. A rubber-stamp in a large platform like Saatchi Art is extremely valuable. [Isla]

Gallery owners and commissioners contacted me just after [Saatchi Art] selected me for Invest in Art. One of my biggest outdoor pieces has been sold to a client in Taiwan. For the last couple of years Saatchi has paid me up to £20,000. I have received more offers and recognition since the curatorial events. [George]

This implies that the increased artwork sales reflect the buyer’s acknowledgement of the legitimacy of selected artworks in the curatorial practices. The following question then is how Saatchi Art selects artists and artworks.

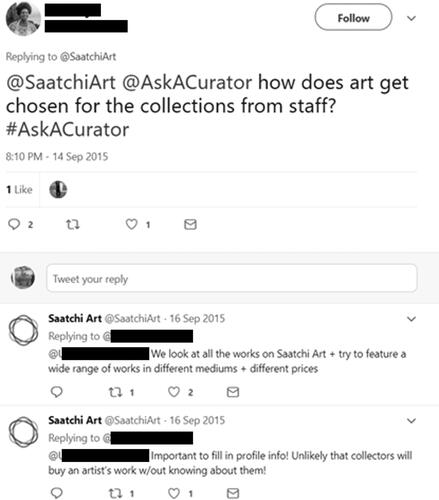

It is hard to trace the selection criteria for the virtual curation of the artists and their works on the platform due to lack of official information on the selection process, although Saatchi Art has described its transparency, as “there’s no grey area” (Spiritus Citation2013). However, we have found relevant data in their annual event regarding interacting digitally between users and the chief curator in which Wilson said, “I look at every work that is uploaded” (SAATCHIART 2015a). As shown in , an anonymous user asked how Saatchi Art included artists to their curatorial practices. Based on Wilson’s reply, which highlights the importance of filling artists’ profiles that are appealing to collectors, we conjecture that the curator reviews artist’s national and educational backgrounds, as well as their artistic careers.

Despite its ambiguous selection criteria, it is interesting to note that the artists who have been selected by Saatchi Art’s curator for a particular group are distinguished from the rest. Extending Bourdieu’s (Citation1996) logic, the accumulated symbolic capital of Saatchi Art is bestowed on the selected artists by giving them exposure in an exclusive virtual space. The symbolic capital of the platform was originated by Charles Saatchi’s brand, which is considered a powerful brand (Thompson Citation2008) and tastemaker (Walker, 1987 cited in Hatton and Walker Citation2003) in the realm of offline art market.

As the identities of intermediaries play an important role in rendering artworks or artists valid (Bourdieu Citation1996), article paper suggests that the influence of the renowned collector’s name is obviously relevant to the digital art market. The chief curator of Saatchi Art once commented on “Saatchi’s” brand as:

… the very powerful brand in the art world. I mean that the Saatchi name… is also completely synonymous with emerging art of a very high standard, so it has this very, very kind of powerful resonance amongst artists (Wilson Citation2013).

Our interviewees are also aware of the influence of Saatchi’s name in terms of making it possible for artists to enhance their career, which led them to join the platform in the first place:

Saatchi Art may give a positive impression [to an artist’s CV]…One big advantage is the name, Saatchi still means something even though you could post any terrible art you want on the site.[Oscar]

The name behind the platform certainly had an appeal because of the viewer attraction it could draw. [Isabella]

An artist also replied to the question about the noteworthy changes in her career after being selected by Saatchi Art: “I got into the finals for Saatchi’s ‘Showdown,’ it looks good on the CV, but it did not bring any sales, and made no difference to my practice” [Oscar]. This “looks good on the CV” response shows that the artist agrees on the benefits of the accumulated symbolic capital of Saatchi Art on her future career.

Moreover, according to a survey by Hiscox (Citation2015), the platform’s reputation offers credibility, allowing consumers to buy artworks confidently. As artworks are displayed by unestablished or emerging artists on the platform, purchase decisions are generated based on Saatchi’s name (Lee and Lee Citation2019). Khaire (Citation2015, 122) declared that “galleries and dealers with existing strong reputations would be more successful online than new-to-the world start-ups.” Acknowledging the effects of the Saatchi brand, Saatchi Art’s current owner (Leaf Group) has maintained the name despite Charles Saatchi’s absence in the business. The dealer influencing the offline art market valuation system continues to show the effects of his name on transactions in the online art market. Hence, Charles Saatchi’s reputation or symbolic capital transcends the offline and online art markets.

Apart from the name, Saatchi Art has retained the symbolic capital of Saatchi through Rebecca Wilson, who is currently its chief curator and vice president. She was formerly an editor of ArtReview and worked at the Saatchi Gallery, where she contributed to the launch of the digital gallery. She engages with a variety of cultural events, including curation, serving as a selection committee member at The Other Art Fair, art advisory, and so on. Some artists mentioned Wilson’s support during interviews,

I have sold the pieces online because Rebecca Wilson, the director has recommended clients to buy my work. She then gets in touch personally [Jack].

The best that happened to me in relation to Saatchi Online was when Rebecca Wilson and the LA CEO invited 10 artists for a private meeting and a little party at a nearby place close to the Saatchi Gallery [Lily].

As we can see in the above statements, Wilson plays an additional role in leading collectors to buy works and establishing close links within the artistic community. Through her multiple roles, artists and collectors are aware of the close link between Saatchi Art and Charles Saatchi. Echoing such perception, Wilson publicly represents the platform in various media.

Legitimizing artists in digital platforms

The initial phase of legitimizing artists in the online art market differs from the one in the offline art market (). Artists embark on the legitimation process by showing their works to distributors or dealers in the conventional art market (Velthuis Citation2005). Meanwhile, the disintermediation of such a relationship that is initiated by Saatchi Art offers an opportunity for artists to introduce their artworks to the audience without convincing intermediaries. In other words, the digitalized art market allows artists to participate in the construction of their legitimacy in their own volition.

Table 5. The comparison between the traditional art world and the digital art platform.

Despite such a structural change, the uncertain value of contemporary artworks in the online market and indirect interpretation of value rendered by Saatchi Art’s democratic filtering have given rise to a reintermediation of the relationship between artists and the audience, consequently granting proper legitimacy to artists. In this process, Saatchi Art’s selection comes prior to reintroduction and interpretation. With their curatorial programs, Saatchi Art selectively reintroduces artworks to viewers and instructs them in their embedded meaning, thereby constructing the legitimacy of the selected artists.

The symbolic capital of intermediaries is commonly stressed in the legitimation process of both online and offline art markets. Our interviewees have reported that after featuring in a Saatchi Art curatorial program, their legitimacy is influenced by the relative symbolic status of the curators. Saatchi Art users, who are either buyers (Lee and Lee Citation2019) or artists, acknowledge the significance of reputation of the chief curator, which accumulated from her education in art history and work experience in the offline art market, and significantly adds credibility in legitimizing selected artists in her curation.

Moreover, different levels of legitimacy can be generated by different types of online curatorial practices, just as different events confer different levels of legitimacy to artists in the offline art market, which underpins an artist’s progress to stardom (Robertson Citation2005). Being featured with other artists in “Collections” is not as influential as being selected as a single artist at other solo virtual shows (“One to Watch Artist” or “Inside Studio”) on the platform. Put differently, although these curatorial programs play a role in distinguishing the selected artists from the rest, the degrees to which they legitimize artists varies according to the method of the curatorship. This way, Saatchi Art creates a hierarchy of social status on its platform.

Another distinctive feature of legitimation in the online art market is that it profoundly relies on a limited number of experts. Saatchi Art curators are in charge of selecting, reintroducing, and interpreting artworks, which frame the legitimacy of artists. There is a subtle difference in such Saatchi Art practices in comparison to those of offline art markets. In the conventional art market, only few artists are legitimized by the consensus of the members of the art world (Becker Citation1982) or as the outcome of struggles between the members in the field of art (Bourdieu Citation1996). However, such collective actions hardly occur in Saatchi Art as it excludes the participation of other intermediaries, exclusively empowering curators to legitimize artists.

Conclusion

This article aims to elucidate the way in which artists and their artworks gain legitimacy in the digitalized art market. By drawing on the conceptual lens on the role of intermediaries in bestowing legitimacy upon artists, our analysis of Saatchi Art shows that the legitimation of artists occurs on its platform primarily through its curatorial programs. Saatchi Art’s curatorial practices selectively reintroduce artists by providing direct (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016) or indirect interpretations (Morgner Citation2014; Acord Citation2010) of their artworks. Hence, selected artists gain legitimacy and symbolic status that translate into economic rewards (Rodner and Kerrigan Citation2014). Our theoretical contribution lies in the amplification of legitimacy construction by introducing, interpreting, and selecting artists in the digital marketplace for contemporary art.

We also examined how the process of legitimating artists in digital platforms differs from that of the conventional art market. On the one hand, disintermediation (Jallat and Capek Citation2001) initiated by Saatchi Art causes a structural change toward direct transactions between artists and buyers in the trading environment of contemporary art. This allows artists to situate themselves directly in the process of legitimation unlike in the traditional art market where artists are represented and endorsed by powerful intermediaries. On the other hand, such disintermediation triggers a different mechanism for legitimation in Saatchi Art. Our findings show that it yields to the tension between democratization and limited ability to distinguish the registered artists on the platform due to the uncertain value of contemporary art (Samdanis and Lee Citation2019; Lee and Lee Citation2017; Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016). Such tension in Saatchi Art has led to the reintermediation of the relationship between artists and buyers (Piancatelli, Massi, and Harrison Citation2020) in order to render the value of presented artworks understandable.

Moreover, the absence of traditional intermediaries in Saatchi Art is a noteworthy difference between the online and offline art markets in terms of the way how artists are legitimized. In the offline market, diverse intermediaries from different professions collectively construct the legitimacy of artists whether their actions are based on cooperation (Becker Citation1982) or struggle (Bourdieu Citation1996). With the absence of traditional intermediaries in Saatchi Art, the legitimation of artists on the platform and the wider digital art market relies exclusively on the power of platform curators.

Contrary to the disintermediation hypothesis, the empowerment of curators in digital art platforms implies the close connection of the online art marketplace and the conventional art world. Indeed, who places value on specific artists is crucial to legitimization as artists are “offered as a guarantee for all the symbolic capital the merchant has accumulated” (Bourdieu Citation1996, 167). The symbolic capital of the Saatchi Art as merchant stems from the reputation of Charles Saatchi and Rebecca Wilson. Our findings reveal that the symbolic capital of the renowned collector transcends into the realm of the online art market, and is sustained by Wilson’s presence in Saatchi Art. Thus, the stratified structure among intermediaries in the offline art world (Robertson Citation2005) permeates into the online art marketplace.

However, our study has hardly addressed the way in which digital art platforms influence the legitimation of artists in the conventional art world (Alexander and Bowler Citation2021, 3) and highlights the ongoing contestation in the process of legitimation, rather than the “end-state of legitimacy.” The legitimacy of artists granted by Saatchi Art is continuously put into scrutiny in the offline art world. It could play a role in complementing or modifying the existing system of legitimation in the offline art world. The platform certainly contributes to fertilizing the art market by incubating selected young and emerging artists who could potentially enhance their careers further as they become recognized and labeled in the broader art world. In this sense, Saatchi Art shows the potential for disturbing the power of existing intermediaries in the offline art world (Lee and Lee Citation2019; Samdanis Citation2016; Khaire Citation2015). Thus, future research could investigate the shifting power relations between new entrants (digital platforms) and existing intermediaries.

Another limitation of this study results from the selection of interviewees by filters. As our target interviewees were delimited by the filters of being featured in Saatchi Art’s curatorial programs and residing in the UK, this could cause a survivor bias in our findings (Aldrich and Wiedenmayer Citation1993). Thus, future research is needed to incorporate unfeatured or unselected artists in the sample when investigating the legitimation process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The term of disintermediation is originally used in reference to households bypassing banks and placing saving with other financial institutions. In the context of the Internet, it is defined as the disappearance of intermediaries, creating “an enhanced sales network in which customers deal directly with service providers” (Jallat and Capek Citation2001, 55).

2 It includes revenue generated by transactions and sales of space to artists and tickets in “The Other Art Fair.”

References

- Acord, Sophia K. 2010. “Beyond the Head: The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art.” Qualitative Sociology 33 (4):447–67. doi: 10.1007/s11133-010-9164-y.

- Aldrich, Howard E., and Gabriele Wiedenmayer. 1993. “From Traits to Rates: An Ecological Perspective on Organizational Foundings.” Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth 1:145–95.

- Alexander, Victoria D. 2003. Sociology of the Arts: Exploring Fine and Popular Forms. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- Alexander, Victoria D., and Anne E. Bowler. 2014. “Art at the Crossroads: The Arts in Society and the Sociology of Art.” Poetics 43:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2014.02.003.

- Alexander, Victoria D., and Anne E. Bowler. 2021. “Contestation in Aesthetic Fields: Legitimation and Legitimacy Struggles in Outsider Art.” Poetics 84:101485. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101485.

- Bakos, Yannis. 1998. “The Emerging Role of Electronic Marketplaces on the Internet.” Communications of the ACM 41 (8):35–42. doi: 10.1145/280324.280330.

- Becker, Howard S. 1974. “Art as Collective Action.” American Sociological Review 39 (6):767–76. doi: 10.2307/2094151.

- Becker, Howard S. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Bloom, Lisa. 2006. “The Contradictory Circulation of Fine Art and Antique on Ebay Lisa Bloom.” In Everyday EBay: Culture, Collecting, and Desire, edited by Ken Hillis, Michael Petit, and Nathan Scott Epley, 231–44. London: Routledge.

- Bottero, Wendy, and Nick Crossley. 2011. “Worlds, Fields and Networks: Becker, Bourdieu and the Structures of Social Relations.” Cultural Sociology 5 (1):99–119. doi: 10.1177/1749975510389726.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Oxford, UK: Poliry Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, Loic J. D. Wacquant, and Samar Farage. 1994. “Rethinking the State: Genesis and Structure of the Bureaucratic Field.” Sociological Theory 12 (1):1–18. doi: 10.2307/202032.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bystryn, Marcia. 1978. “Art Galleries as Gatekeepers: The Case of the Abstract Expressionists.” Social Research 45 (2):390–408.

- Chircu, Alina M., and Robert J. Kauffman. 1999. “Strategies for Internet Middlemen in the Intermediation/Disintermediation/Reintermediation Cycle.” Electronic Markets 9 (2):109–17.

- Crane, Diana. 1989. The Transformation of the Avant-Garde: The New York Art World, 1940-1985. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Crane, Diana. 2009. “Reflections on the Global Art Market: Implications for the Sociology of Culture.” Sociedade e Estado 24 (2):331–62. doi: 10.1590/S0102-69922009000200002.

- Currid, Elizabeth. 2007. “The Economics of a Good Party: Social Mechanics and the Legitimization of Art/Culture.” Journal of Economics and Finance 31 (3):386–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02885728.

- Danto, Arthur C. 1964. “The Artworld.” The Journal of Philosophy 61 (19):571–84. doi: 10.2307/2022937.

- Delacour, Hélène, and Bernard Leca. 2017. “The Paradox of Controversial Innovation: Insights from the Rise of Impressionism.” Organization Studies 38 (5):597–618. doi: 10.1177/0170840616663237.

- Dunn, Kevin. 2005. “Interviewing.” In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, edited by Iain Hay, 2nd ed., 79–105. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4):532–50. doi: 10.2307/258557.

- Evans, Philip, and Thomas S. Wurster. 1997. “Strategy and the New Economics of Information.” Harvard Business Review 75 (5):70–82.

- Freeland, Cynthia. 2001. But is It Art? Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Gielens, Katrijn, and Jan Benedict, and E. M. Steenkamp. 2019. “Branding in the Era of Digital (Dis)Intermediation.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 36 (3):367–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.01.005.

- Hatton, Rita, and John Albert Walker. 2003. Supercollector: A Critique of Charles Saatchi. London, UK: Institute of Artology.

- Hirsch, Paul M. 1972. “Processing Fads and Fashions: An Organization-Set Analysis of Cultural Industry Systems.” American Journal of Sociology 77 (4):639–59. doi: 10.1086/225192.

- Hiscox. 2015. “The Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2015.” London, UK: Hiscox.

- Hiscox. 2019. “Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2019.” London, UK: Hiscox.

- Hiscox. 2020. “Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2020.” London, UK: Hiscox.

- Horowitz, Noah. 2012. “Internet and Commerce.” In Contemporary Art and Its Commercial Markets: A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios, edited by Maria Lind and Olav Velthuis, 85–114. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jallat, Frédéric, and Michael J. Capek. 2001. “Disintermediation in Question: New Economy, New Networks, New Middlemen.” Business Horizons 44 (2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0007-6813(01)80023-9.

- Joy, Annamma, and John F. Sherry. 2003. “Disentangling the Paradoxical Alliances between Art Market and Art World.” Consumption Markets & Culture 6 (3):155–81.

- Katz, Elihu. 1988. “Disintermediation: Cutting out the Middle Man.” Intermedia 16 (2):30–1. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/162.

- Khaire, Mukti. 2015. “Art without Borders? Online Firms and the Global Art Market.” In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art, edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Curioni, 102–28. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leaf Group. 2020. “Inverster Overview Presentation 2020.” Santa Monica, CA: Leaf Group.

- Lee, Jin Woo., and Soo Hee Lee. 2017. “Marketing from the Art World’: A Critical Review of American Research in Arts Marketing.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 47 (1):17–33. doi: 10.1080/10632921.2016.1274698.

- Lee, Jin Woo., and Soo Hee Lee. 2019. “User Participation and Valuation in Digital Art Platforms: The Case of Saatchi Art.” European Journal of Marketing 53 (6):1125–51. doi: 10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0788.

- Lee, Soo Hee., and Jin Woo Lee. 2016. “Art Fairs as a Medium for Branding Young and Emerging Artists: The Case of Frieze London.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 46 (3):95–106. doi: 10.1080/10632921.2016.1187232.

- Lizé, Wenceslas. 2016. “Artistic Work Intermediaries as Value Producers. Agents, Managers, Tourneurs and the Acquisition of Symbolic Capital in Popular Music.” Poetics 59:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2016.07.002.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 2016. “Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups.” In Key Methods in Geography, edited by Nick Clifford, Shaun French, and Gill Valentine, 3rd ed., 143–53. London: Sage.

- Meho, Lokman I. 2006. “E-Mail Interviewing in Qualitative Research: A Methodological Discussion.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (10):1284–95. doi: 10.1002/asi.20416.

- Merriam, Sharan B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Morgner, Christian. 2014. “The Art Fair as Network.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 44 (1):33–46. doi: 10.1080/10632921.2013.872588.

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1987. The French Art Market: A Sociological View. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Noël, Laurent. 2014. “Dealing with Uncertainty: The Art Market as a Social Construction.” In Risk and Uncertainty in the Art World, edited by Anna M. Dempster, 239–74. London: Bloomsbury.

- O’Neill, Paul. 2007. “Introduction.” In Curating Subjects, edited by Paul O’Neill, 11–9. London: Open Editions.

- Peterson, Karin. 1997. “The Distribution and Dynamics of Uncertainty in Art Galleries: A Case Study of New Dealerships in the Parisian Art Market.” Poetics 25 (4):241–63. doi: 10.1016/S0304-422X(97)00016-8.

- Piancatelli, Chiara, Marta Massi, and Paul Harrison. 2020. “Has Art Lost Its Aura? How Reintermediation and Decoupling Have Changed the Rules of the Art Game: The Case of Artvisor.” International Journal of Arts Management 22 (3):34–54.

- Preece, Chloe, Finola Kerrigan, and Daragh O’Reilly. 2016. “Framing the Work: The Composition of Value in the Visual Arts.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (7/8):1377–98. doi: 10.1108/EJM-12-2014-0756.

- Robertson, Iain. 2005. “The International Art Market.” In Understanding International Art Markets and Management, edited by Iain Robertson, 13–36. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Rodner, Victoria L., and Finola Kerrigan. 2014. “The Art of Branding—Lessons from Visual Artists.” Arts Marketing: An International Journal 4 (1/2):101–18. doi: 10.1108/AM-02-2014-0013.

- Rodner, Victoria L., Maktoba Omar, and Elaine Thomson. 2011. “The Brand-Wagon: Emerging Art Markets and the Venice Biennale.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 29 (3):319–36. doi: 10.1108/02634501111129275.

- SAATCHIART. 2015a. “I Look at Every Work That Is Uploaded.” Twitter. 2015. https://twitter.com/SaatchiArt/status/512368882917859328.

- SAATCHIART. 2015b. “Questions about Contemporary Art Trends, Investment, or Advice for Artists?” Instagram. 2015. https://www.instagram.com/p/7svQdzDQTR/.

- Saatchi, Charles. 2012. My Name is Charles Saatchi and I Am an Artoholic. London, UK: Booth-Cibborn Editions.

- Samdanis, Marios. 2016. “The Impact of New Technology on Art.” In Art Business Today: 20 Key Topics, edited by Jos Hackforth-Jones and Iain Robertson, 164–73. London, UK: Lund Humphries Publishers.

- Samdanis, Marios, and Soo Hee Lee. 2019. “Uncertainty, Strategic Sensemaking and Organisational Failure in the Art Market: What Went Wrong with LVMH’s Investment in Phillips Auctioneers?” Journal of Business Research 98:475–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.030.

- Sarkar, Mitra Barun, Brian Butler, and Charles Steinfield. 1995. “Intermediaries and Cybermediaries: Sarkar, Butler and Steinfield.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 1 (3):JCMC132. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.1995.tb00167.x.

- Sen, Ravi, and Ruth C. King. 2003. “Revisit the Debate on Intermediation, Disintermediation and Reintermediation Due to E-Commerce.” Electronic Markets 13 (2):153–62. doi: 10.1080/1019678032000067181.

- Spiritus, Margo. 2013. “Art in the Age of Digital Discovery: A Conversation with Rebecca Wilson, Chief Curator Saatchi Online [Video].” Livestream. 2013. http://livestream.com/smwla/events/2394384/videos/30975651.

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London, UK: Sage.

- Thompson, Don. 2008. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. London, UK: Aurrum Press Ltd.

- Velthuis, Olav. 2005. Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Velthuis, Olav, and Stefano Baja Curioni. 2015. “Making Market Global.” In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art, edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baja Curioni, 1–30. New York: Oxford University Press.

- White, Harrison C., and Cynthia A. White. 1993. Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World. Chicago, IL: The Chicago University Press.

- Wijnberg, Nachoem M., and Gerda Gemser. 2000. “Adding Value to Innovation: Impressionism and the Transformation of the Selection System in Visual Arts.” Organization Science 11 (3):323–29. doi: 10.1287/orsc.11.3.323.12499.

- Wilson, Rebecca. 2013. “Art in the Age of Digital Discovery: A Conversation with Rebecca Wilson, Chief Curator Saatchi Online [Video].” Livestream. LA. 2013. http://livestream.com/smwla/events/2394384.

- Zelditch, Morris. 2001. “Processes of Legitimation: Recent Developments and New Directions.” Social Psychology Quarterly 64 (1):4–17. doi: 10.2307/3090147.