Abstract

Performing artists seem to remain in the culture sector despite the challenges with sustaining an artistic practice. Our research question is why the occupational commitment of the artistic precariat survives an external shock like the Covid-19 shutdown. We combined quantitative and qualitative survey data among performing artists in Norway (N = 607) one year into the pandemic. Innovation and portfolio management took place in tandem with intense identity work. The perception of “otherness” reinforced overall artist identity and thereby sustained occupational commitment. Any excess supply of practitioners in the sector seems to some degree disconnected from the actual economic conditions.

Introduction

The title of Victor Hugo’s novel is used to introduce our research topic: how to make sense of precarious conditions among performing artists. The cultural and creative industries worldwide were among the hardest hit by the economic consequences of the pandemic-induced lockdown (OECD. Citation2020). In addition, the sector is characterized by widespread self-employment, freelancing, and short-term project work (Bennett Citation2009; Bennett and Bridgstock Citation2015; Hennekam Citation2017), which aggravated financial distress on the individual level. Despite worsened conditions, cultural workers still express strong occupational commitment mid-pandemic (Elstad, Døving, and Jansson Citation2021). We therefore wanted to study “what goes on” through how its practitioners make sense of their apparently unattractive positions. Empirically, the study is situated in Norway, and we focused on the segment within the performing arts that includes musicians, music educators, and audio/light/studio professionals. We use mixed methods, combining quantitative analysis of self-reported survey data with qualitative analysis of corresponding written commentaries.

Careers within the creative industries involve extensive underemployment and unemployment (Bridgstock et al. Citation2015). A constant excess supply of artists fuels job uncertainty and low incomes (Menger Citation1999; Steiner and Schneider Citation2013). An excess supply of artists is also observed specifically for Norway, where self-employed work arrangements dominate, with corresponding lower income levels (Elstad, Pedersen, and Røsvik Citation1996; Heian, Løyland, and Kleppe Citation2015; Mangset et al. Citation2018). Scholars have pointed at how artists tend to remain poor (Abbing Citation2008; Menger Citation1999; Bain and McLean Citation2013).

The culture sector was vulnerable when the Covid-19 pandemic hit because it depends on open social arenas and many of its practitioners were already in precarious working situations. A large portion of the performing artist population found itself in a perfect storm – constricted in its ability to practice, a gloomy economic outlook, and an already weak starting position. Nonetheless, in our recent research, we have only observed a weak tendency to leave the sector (Elstad, Døving, and Jansson Citation2021; Elstad, Jansson, and Døving Citation2022).

Several studies on artists and the pandemic have been undertaken, covering an array of topics from technology adoption and financial implications to well-being and creative identity (Brooks and Patel Citation2022; Salvador, Navarrete, and Srakar Citation2022). These include data from the early phase of the lockdown in 2020. Our contribution is to go behind the immediate impact and investigate how artists make sense of their experiences one year into the pandemic.

Artistic practices are inherently associated with meaning and identity, and for many constitutes a profession of calling (Røyseng, Mangset, and Borgen Citation2007), where occupational commitment is deeply rooted. Specifically, we wanted to explore what happened with strongly committed artists when their working situation suddenly deteriorated due to a massive external shock such as the pandemic lockdown, and we posed the following research question: How do committed artists in economic distress make sense of their situation, as manifested by practical adjustment and identity work?

Precariousness and the ability to sustain an artistic practice

In a framework by Campbell and Price (Citation2016), the precariat concept captures a class-in-the-making emerging from precarious workers (Standing Citation2011). Given the relatively high educational level of artists (Heian, Løyland, and Kleppe Citation2015, 106), we instead understand precariousness in terms of work arrangements and work characteristics. We classify all other nonstandard work arrangements than permanent, full-time employment as precarious work arrangements. Examples include part-time employment, temporary employment, self-employment as a freelancer, working for one’s own company as an independent contractor (Cappelli and Keller Citation2013), or combining different work arrangements (Ashton Citation2015; Elstad, Døving, and Jansson Citation2020; Heian, Løyland, and Kleppe Citation2015). Careers in creative professions are characterized by precarious work arrangements and characteristics (Bennett Citation2009; Bennett and Bridgstock Citation2015; Hennekam Citation2017; Mangset et al. Citation2018; Menger Citation1999; Steiner and Schneider Citation2013) with notable income differences between employed cultural workers and those with precarious works arrangements (Elstad, Døving, and Jansson Citation2020).

Precarious work arrangements may imply precarious work characteristics, including uncertainty, instability, and insecurity, where the employee carries the risk of no work and enjoy limited statutory protection and few social benefits (Kalleberg and Vallas Citation2018). Such individualization of risk is a key feature of precarity in the cultural sector (Bain and McLean Citation2013). For those with precarious works arrangements, the lockdown induced more precarious work characteristics among artists as indicated by income losses in Norway for 2020 − 33% for the music sector and 53% for the performing arts (Røed et al. Citation2021). It should be noted that even in a comprehensive welfare state such as Norway, most social benefits are connected to permanent employment. Temporary workers, freelancers, and self-employed generally have less access to unemployment and sick pay, as well as weaker redundancy protection and pension rights (Jensen and Nergaard Citation2019). In addition, self-employed artists largely fell outside the Covid-specific compensation schemes in Norway (Arts Council Norway and Norwegian Film Institute Citation2021), similar to how performing artists in the UK experienced lack of government support and “falling through the cracks” (Spiro et al. Citation2020, 11).

Occupational commitment

An occupation is an identifiable line of work that the artists undertake, such as musician, music teacher, and studio engineer. Occupational commitment represents a psychological link between a person and his or her occupation based on an affective reaction to that occupation (Lee, Carswell, and Allen Citation2000). Such commitment usually implies a certain level of continuity – a desire to sustain a career in the current occupation. We define occupational commitment (OC) as the identification and feelings toward one’s occupation, both with regards to having chosen it in the first place and the wish to remain in that occupation. Our study includes the professionally educated as well as autodidacts and we use the term occupational commitment (Meyer, Allen, and Smith Citation1993) rather than professional commitment (Morrow Citation1993).

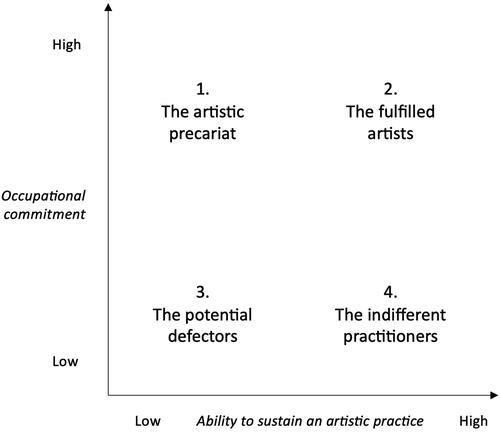

The two dimensions ASAP and OC define a population map as shown in . Our primary interest is in quadrant 1, what we have labeled as the artistic precariat. The research question is addressed partly by qualitatively analyzing this sub-population and partly by comparing quantitative indicators across the sub-populations.

Analytical framework

The research question draws attention to how performing artists experience the lockdown, how they understand its implications, create meaning from them, and act on them. We use the theory of organizational sensemaking (Weick Citation1995) as an interpretive frame for our study because it accommodates the interplay between understanding and agency as well as between agency and identity work. While somewhat eluding a single agreed definition, there is an emerging agreement that sensemaking refers to the processes by which people seek to plausibly understand ambiguous or confusing issues (Brown, Colville, and Pye Citation2015). Weick developed seven properties of sensemaking: it is (1) ongoing, with no clear beginning or end, (2) rooted in identity as well as an impetus for identity formation, (3) social, (4) triggered by cues as well as conducive of which cues we attend to, (5) retrospective, (6) enactive, and (7) favors the plausible over the accurate.

Although the concept was originally developed for organizations where the unit of analysis is the collective of individuals in a well-defined entity, it has also been found applicable to individuals in more open-ended structures such as a professional practice (Boggess Citation2018; Ng and Tan Citation2009; Sturges et al. Citation2019; Jansson, Elstad, and Døving Citation2021; Weick Citation1976). Performing artists operate within fuzzy organizations of peers and fellow practitioners. According to Weick (Citation1976), such loosely coupled systems imply increased pressure on individuals to construct their social reality.

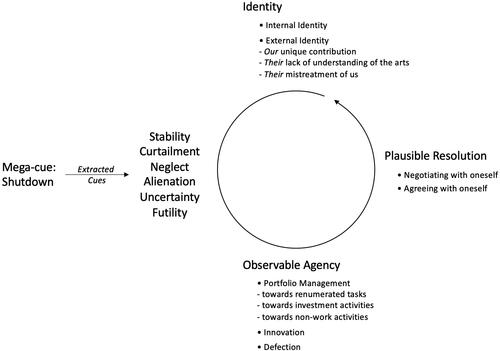

The seven properties of sensemaking are conceptually distinct, although inter-connected. Survey and interview questions impose themselves on respondents as cues that prompt articulation, although similar cues may already slumber beneath the surface. A key feature of the seven properties of sensemaking is that they are all present and interact in every sensemaking endeavor. Within the observational constraints of self-reported survey data, we focused on four of the sensemaking properties to constitute corresponding study variables: (1) The cue property was observed via how the lockdown as a shared “mega-cue” was experienced in the form of subsequent extracted cues. (2) The enactive property became salient via stated action – observable agency. (3) The identity property, both as antecedent and result, was observable as reinforced or modified identity. (4) The plausibility property emerged as aspects of satisfaction and as level of acceptance of the situation – as plausible resolution of the mega-cue. These four adapted study variables served as first level categories for interpreting the written commentaries.

Materials and methods

The present study is part of an ongoing research program investigating how artists and cultural workers are impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic (Elstad, Døving, and Jansson Citation2020, Citation2021; Elstad, Jansson, and Døving Citation2022). This article is based on data from January 2021.

The participants were members of Creo – Norway’s largest trade union for performing artists with 8 742 members. Creo members include musicians, singers, conductors, composers, music and drama teachers, organists, cantors, dancers, choreographers, actors, dramaturgs, directors, audio/light/studio engineers, scenographers, costume designers, producers, stage managers, and administrative staff. The web-based data collection was administered via Nettskjema, a platform enabling the processing of anonymous data and provided by the University of Oslo. Invitees were informed about anonymity and the right to not participate. Participants were asked to answer a range of structured questions as well invited to write longer or shorter commentaries about their experiences during the lockdown. The net sample consists of 607 responses.

Sample structure

General characteristics

The sample included 64% musicians, 29% music educators, and 7% audio/light/studio professionals, approximately the same structure as the Creo membership database. However, we do not pay attention to the sub-groups in the analysis, as the boundaries between the groups are somewhat fuzzy − 38% of the musicians are also educators and 95% of the music educators are also active performers. A majority hold a graduate degree. Mean gross annual income was 479,813 NOK (approximately 48,000 EUR). The median age was 41-45 years, 48% were female, 75% were married/cohabitators, and 36% had children under 18 years of age living at home. Among our respondents, 57% had permanent employment, which means that 43% had mixed work arrangements. The research questions pay particular attention to the artistic precariat – the group that was economically in the least favorable position while still being strongly committed to their artistic practice. We therefore split the sample into four sub-samples based on the two dimensions occupational commitment and ability to sustain an artistic practice. To classify according to these dimensions, we created two composite indices from available variables.

Characteristics of the artistic precariat

The index of occupational commitment (OC) combines items from two measurement instruments (Blau Citation1988; May, Korczynski, and Frenkel Citation2002), encompassing (1) occupational pride, (2) regrets about an art career (reverse coded), and (3) the importance of an art career. The responses were captured on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = does not at all agree to 5 = fully agree.

We constructed a composite index for the ability to sustain an artistic practice (ASAP) based on the combination of precariousness in work arrangements and work characteristics. Specifically, work characteristics included: (1) actual gross income, (2) perceived income potential, and (3) perceived economic security. As an additional criterion for distinguishing between ASAP levels, we considered only those with full-time employment as high ASAP and all other work arrangements as low ASAP. The measurement instruments for the two composite indices are shown in Appendix 1.

Because our focus was on the artistic precariat and variables have a skewed distribution, we defined the cutoff between high and low so that two thirds of the sample were in the category high OC and two thirds were in the category low ASAP, which also left a sufficiently large sub-sample.

Mixed methodology

A large portion of the respondents wrote rather lengthy stories, and we realized that the material was well suited for a qualitative analysis with numerical substantiation. The rationale for a mixed methodology within the same study is that the combination will enlighten the research question more effectively than the two separate methods (Cresswell and Piano Clark Citation2011).

Analytical steps

The qualitative analysis was done as a stepwise process. The initial steps included coding of raw text data with the four selected sensemaking categories, identification of sub-categories, and the generation of code-reports. The software application HyperRESEARCH was used for these steps. Based on the code-reports, each sub-category was interpreted and elaborated as an iterative reading and (re-)writing process.

Quantitative substantiation

The structured part of the survey included variables that indicate aspects of sensemaking activity, although not measure it in a strict sense. For the sub-categories of sensemaking identified within the artistic precariat, we used the variables in to investigate whether these findings were also reflected as quantitative differences between the sub-samples.

Table 1. Variables for quantitative analysis. Scored on a scale 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree).

The approach was characterized by a full mixing, concurrent timing, and somewhat equal status of the two methods. According to taxonomy by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (Citation2009), this approach is labeled as a fully mixed concurrent equal status design.

Qualitative analysis – sensemaking among the artistic precariat

During the analysis, equal attention was given to the four selected sensemaking categories. However, the following presentation is balanced according to how the various categories expose the non-trivial features of how sense is made.

Cue extraction

Cues are both a trigger of sensemaking and focusing mechanism when making sense. All the respondents were exposed to one mega-cue – the lockdown in March 2020. When respondents describe how it impacted them, it reflects the nature of what hit them as well as what aspects they attended to. We identified six cues that the respondents attended to: stability, curtailment, neglect, alienation, uncertainty, and futility. These often appeared in combinations and fueled the further sensemaking process, which was interpreted by using the categories observable agency, identity, and plausible resolution. This analytical logic is illustrated in . From the analysis, we identified sub-categories that exposed distinct facets of each main category.

Observable agency

According to the theory, all sensemaking is enactive, that is, oriented toward doing something, which includes overt action as well as identity work and even plausible resignation. When respondents describe how they have adapted their professional practices, we get access to their observable agency, primarily portfolio management and innovation. Defection only appears as hypothetical albeit credible future action.

Portfolio management

The prevalence of mixed work arrangements in the artistic precariat provides ample opportunity for shifting between activities and job rotation. Shifting toward the allowed includes going from live performance to studio recording, from large to small venues, from stage achievement to skill nurturing at home, from ensemble rehearsing to composing and arranging, and from artistic tasks to office tasks. Respondents describe highly individualized portfolios, often including multiple portfolio elements:

I lost all planned gigs. A few went digital. I also give bass lessons, a few of these were done digitally, but mostly canceled or delayed. I have handled a lot of free time by practicing a little every day to maintain my skills, in addition to keeping myself in physical shape.

Job rotation may to varying degrees retain income level and shifts usually imply more non-paid activities and activities with deferred income. A great many respondents compose, arrange, and record music as supporting activities to a performing or conducting practice, and expanding such activities is experienced as highly meaningful. At the same time, portfolio management may require intense labor in connection with cancelations, renegotiation of contracts, and maneuvering in the rather complex field of compensation schemes. From a sensemaking point of view, a varied portfolio may allow adaptation without excessively straining identity or pushing the limits of plausibility.

Innovation

Respondents have both renewed what they offer and the process of delivery. Innovating services is partially about complying with lockdown restrictions without canceling and partially about creating new formats. Process innovation largely means going digital with existing offerings.

I am one hundred percent an independent business and have nothing to fall back on. But I am adaptable, so I have adapted and adapted and adapted. Concerts have been canceled, moved, rebooked on and off again. The first months, I created new projects adapted to the new situation, digital concerts and combined digital and physical, sought funding for new concepts and made things happen.

Some respondents discovered that they reached new audiences by attracting more people to their digital channels and by expanding the number of appearances, for example by livestreaming rehearsals and offering shorter but more frequent concerts online.

Reinforced/modified identity

Identity is inherently a relational phenomenon because the understanding of self is intertwined with how the self-views others and vice versa. The notion of identity appears in the data from two angles, which we have labeled internal and external identity. Internal identity is constructed via an inside-out view. It deals with why the respondents are practitioners in this sector in the first place. External identity is constructed via an outside-in view, it lets society’s attitudes and policies frame the professional self, weakening or reinforcing internal identity.

Identity: internal

Being a performing artist appears in the data as a profession of calling, a dedication with an existential rationale. The lockdown presented a sudden caesura for these callings and exposed the significance of doing art, that is rehearsing and performing – together with ensemble peers, apprentices, and the public. Although the lockdown gave more time for practicing within the realm of home studios, this has also been offset by lack of motivation, effort, and more self-doubt in the absence of live venues.

[…] the problem is that one’s identity is so strongly attached to being on stage, playing music for an audience. The recent years have been extremely busy, so when everything stops and nothing happens, it is difficult to know who you really are. What’s valuable in life […].

A notable observation is that financial compensation has had little bearing on the grief from not being able to perform. There is a deep sense of loss from being inflicted a berufsverbot of sorts. The existential significance of the profession is in many cases articulated passionately and desperately, where example wordings include “every cell in my body screams for being allowed to perform,” “on the verge of breakdown after a year without the orchestra,” and “feeling of emptiness.”

Within the confines of home studios and offices, performing art loses its valued qualities and begins to resemble any other type of job. The combination of a precarious working situation and dwindling preciousness of a performing art profession seems to rattle identities only to a limited extent. Respondents may reflect on the future attractiveness of the sector for new entrants, but there are few, if any, expressions of reduced passion and changed view of self as a performing artist. On the contrary, grief and frustration incur narratives that make their identities more salient.

Identity: external

The construction of external identity appears as a demarcation process, making use of various signs and stakes in the ground that separate of “us” from “the others.” Three demarcation categories are being used by the respondents: (1) our contribution to society is unique, (2) the authorities don’t understand the arts and what we bring, and (3) we are being mistreated in pandemic regulations and compensation schemes.

Our unique contribution

If an artistic practice matters for the individual, some level of external justification is sought after. One statement summarizes quite succinctly how the arts contribute to society, implicitly in a way that no other sector can:

We pay taxes, we bring joy and meaning to people’s lives, we don’t bring environmental damage with what we do. If we disappear, the country will change. It will be grayer. People become sadder. We (or rather you, it seems) will have new social problems for which there are no humane solutions.

A notable distinction is made in the parenthesis – explicitly referring to “we” and “the others.” The statement also expresses the somewhat ambivalent relationship between the existential rationale for the arts and its instrumental purpose – meaning, but also taxes and mitigating social problems.

A notable feature of the respondents’ articulation of their contribution to society is an apparent ambiguity – highlighting uniqueness as well as the need to be like everyone else. The key observation is that uniqueness to some extent depends on not being appreciated or understood in its function as free expression and a provocative voice.

Their lack of understanding of the arts

When respondents articulate the lack of the others’ understanding, it is a rather blunt accusation of society and the authorities at large or the government in office specifically. Articulations of “not being understood” is a distinct feature of otherness. In some cases, the government is accused of “not understanding” more broadly, which appears more as an identity boost than rooted in sector fundamentals.

A rather painful undertone of this otherness is “not being seen,” that is, a perception that pandemic regulation and compensation schemes fail to recognize the nature of the performing art sector. Policies are experienced as blind toward its fragmented work arrangements and respondents express unequivocally a feeling of alienation in the encounter with complex regulations.

I don’t think the authorities are aware of how much of the culture sector in Norway is run by small, idealistic organizations on marginal budgets, who do not have access to the compensation schemes and who take great personal risks to keep culture going and who are in grave danger of bankruptcy.

Freelancers, especially in the beginning of their careers, wish that the authorities would see how “close to the poverty line” they are. At the same time, what they really want is not to collect easy compensation money, just to get through the lockdown and back to the professional practice they love.

Their mistreatment of us

The perception of being treated poorly is a mix of tangible effects of the lockdown and projecting a wide array of evils on to the government. Performing artists were indirectly hit by a poor fit between compensation schemes and the prevalence of mixed work arrangements. Respondents interpret this mismatch as a harsh discrimination against the arts, either as incompetence on the part of the authorities, but even as willful malfeasance.

There are newly graduated performers who feel lured into the sector, barred from working but without a sufficient safety net. On the other hand, the longevity of a career has accustomed performers to uncertainty – “learnt to endure this after twenty-five years as a musician.” For freelancers contracting with publicly funded institutions, the pre-pandemic economic conditions may create a particularly frustrating concurrence: being poorly paid in the first place and being poorly Covid-compensated based on previous low income.

I notice that I often do things almost like a volunteer or at a ridiculous price because the institutions don’t have much money to offer, and because I’m an idealist and believe that it is an important job. The alternative is to not do what I love.

The statement ties together several elements into a “complete” sensemaking strand. The cue of financial squeeze is handled be reinforced identity, acting by not leaving, and plausibly living with the situation.

Plausible resolution

The plausibility property of sensemaking implies that when trying to make sense, the success criterion is not completion or closure of an issue, but simply moving on. The respondents experienced massive dissonances between the ideal and the possible, with an unusually limited space for accurate problem solving. Plausibility appears in the data in two guises – respondents weighing and trading between dissimilar aspects of the lockdown and making summary assessments of their situation.

Negotiating with oneself

There are two prominent negotiations going on – weighing one’s financial situation against everything else and rebalancing within the non-financial aspects of one’s practice. One variant is experiencing positive aspects of negative situations, such as loneliness but reduced exhaustion and reaching new audiences by being forced to webcast performances. When respondents articulate their self-negotiations, they tend to explicitly contrast the factors being weighed:

I have struggled with motivation, creativity, and the joy of creating, at the same time, I am happy about more time for myself, calmer days, space for planning and contemplation, and time to do non-work-related things. I have become better at the administrative work and had the time to think longer and deeper thoughts, but when it comes to the [artistic] practice and implement these plans, it has been a struggle.

These two sentences each highlight a positive and a negative in a tensional relationship, however, the statement reflects someone moving along rather than standstill.

Agreeing with oneself

Although a sensemaking process is always ongoing, with no clear beginning or end, respondents at times bring it to a closure, at least temporarily. An internally focused closure means that things are difficult, but not worse than can be handled. A relative resolution has been readily available because there is always someone worse off. Unsurprisingly, when making overall assessments, the aspects being weighed can be rather extreme:

[…] financially it has been all right, and I have done new things, written and published a book, among other things. But I am now completely fed up. The air is out of the balloon, and I struggle with motivation to initiate new projects and make things happen. All in all, I have handled the situation well, and I am quite proud of myself, in fact.

When exasperation and pride interact to make sense, violent forces are in play. The plausibility property is a strong moderator of highly unattractive realities. By its portfolio nature, a precarious artist life situation seems to be a blessing in disguise. While it presents uncomfortable uncertainty, it also provides a varied repertoire of activities and the possibility of blending these in innumerable ways. Plausible assessments are temporary closures, and the open-endedness may appear as futility but also as aspirations. For example, one respondent attributes cathartic qualities to the lockdown, believing that great art will come out of this period and even help society onwards to a new normalcy.

Quantitative analysis: how the artistic precariat stands out

The artistic precariat finds itself in a desired but not particularly desirable position. We would expect quantitative indications of differences in sensemaking between the artistic precariat and the other groups. shows means for the variables that were selected as potentially indicative of sensemaking.

Table 2. Quantitative indicators of sensemaking based on mean scores (scales 1–5).

A conspicuous feature of the artistic precariat (Q1) is the high score for portfolio management. To some degree, this had to be expected, given the prevalence of mixed work arrangements from the quadrant definition. However, it should be noted that also permanent full-time employees commonly include freelance and temporary work in their portfolios. Innovation, on the other hand, seems somewhat more dependent on the ability to sustain an artistic practice. For Q1, there is a mixed maneuverability – they are able to operate flexibly with task portfolios under their own control, however, with less capacity for innovative external risk-taking when developing new concepts for their audiences. The artistic precariat (Q1) resembles the fulfilled artists (Q2) with regards to internal identity, a reasonable finding given its individual and rather stable foundation. Furthermore, internal identity is lower for Q3 and Q4 compared to Q1 and Q2, indicating the linkage between occupational commitment and internal identity for the artistic precariat. For external identity, in contrast, the Q1 scores are higher than Q2, which indicates more distance to the authorities and society at large and a higher frustration level from a weaker ability to sustain their practice. For the artistic precariat (Q1), external identity is more in line with the potential defectors (Q3). The sum of external and internal identity scores for the artistic precariat (Q1) stands out from all the other groups. Here, the Q1 scores mirror the qualitative analysis that demonstrated how identity derives from passion for the practice and is reinforced by the threats to sustaining an artistic practice.

Job satisfaction is extreme when the situation is unambiguous – highest for the fulfilled artist (Q2) and lowest for the potential defectors (Q3). Here, the artistic precariat (Q1) and the indifferent practitioners (Q4) have medium-level scores, arising from asymmetric conditions with regards to commitment and the ability to sustain a practice. The residual plausibility does not vary between groups.

Summing up, the analysis shows that the artistic precariat exhibits some distinct features. Portfolio management, enabled by mixed work arrangements, appears as the key tool when responding to the lockdown. While not necessarily being a voluntary choice, sophisticated multi-tasking among the self-employed enables survival. Although innovation is less prominent, it does not imply that they are less creative, however, they have fewer financial resources that allow them to experiment than those with permanent jobs. Increased precarity has the potential to impair occupational commitment, but at the same time, precarity is also congruent with an artistic identity, at least to the degree that it makes plausible sense.

Discussion

Artists have to some degree an outsider identity in relation to the political establishment, where a precarious situation is subsumed into that identity. When economic conditions worsen, the external identity is reinforced because it highlights the indispensable role of artists. Multiple work arrangements in the arts sector were particularly challenging when attempting to qualify for government compensation. The alienation that arises from Kafkaish encounters with pandemic policies and compensation schemes further adds to the outsider status. This observation concurs with the notion of in-group and out-group in social identity theory, where identity arises as an interplay and in particular a favorable comparison between “us” and “the others” (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979). For the artistic precariat, there is an interplay between internal and external identity that raises the exit bar. Other studies have found that the lockdown challenged creative identities (Spiro et al. Citation2020) as well as provided opportunity for rediscovering a musician identity through new types of encounters with the public (Cohen and Ginsborg Citation2021). Internal identity may initially be threatened by a worsened economic basis, for example by impairing motivation, but our results suggest that a more salient external identity compensates to the extent that overall artistic identity is reinforced.

While identity is a key driver of plausible solutions, the portfolio nature of the precariat’s working situation seems to be the key practical tool in processing the cues. Hence, mixed work arrangements are both a cause of precarious economic conditions and a solution for overcoming them, at least during a lockdown. A wider work portfolio offers a richer sensemaking affordance (Jansson, Elstad, and Døving Citation2021), that is, more opportunities for not only blending activity types but also more fluid shifting of identities, which could also be seen as shifting between multiple callings such as musician, composer, and teacher. This concords with Berg, Grant, and Johnson (Citation2010) proposition that people with multiple callings are somewhat protected from dissatisfaction. The fragmented nature of the artistic precariat’s work-life is therefore both a curse and a blessing.

Our study elucidates some of the mechanisms that sustain careers despite incentives to defect and therefore tend to generate an over-supply. The paradox is that attempts to improve the economic conditions for artists may lead to a larger precariat instead of a less precarious precariat. This notion raises a related policy issue: what is the appropriate balance between supporting the arts through sector-specific funding and being treated and helped through improved general industrial and labor policy? The qualitative analysis suggests that performing artists did not ask for charity during the pandemic, rather they called for better general support of small businesses, and not least, being treated with a better understanding of the inner workings of the performing art sector. This finding concurs with Comunian and England (Citation2020) recommendation that policy responses to creative and cultural workers’ concerns should be of structural nature rather than situational. To this end, demographic impact should be made more visible – exposing the untenable position of the precariat by being in a weaker starting position as well as losing out in the situational policies.

Conclusions, limitations, and further research

Among musicians, a large proportion may be characterized as the artistic precariat – with a low ability to sustain an artistic practice while being strongly committed to their occupation. Pervasive mixed work arrangements were both a cause of problems and the source of flexible agency when they faced the lockdown. However, innovation and work portfolio management took place in tandem with intense identity work. The external aspect of identity – driven by the perception of “otherness,” has reinforced overall artist identities and thereby sustained occupational commitment. The triad agency-identity-plausibility is the key to understanding how performing artists endure an apparently untenable situation. Reinforced identities help to stabilize occupational commitment but is supported by the notion of plausibility – an indispensable cushion between the desirable and the possible.

Our observations of sensemaking activity are captured at a single point in time, although informants describe aspects of time and development. Further research could investigate the sensemaking of the artistic precariat over time more systematically via longitudinal studies. There are few signs of exit from the art sector in the artistic precariat, even among the potential defectors. However, our data may be biased toward the stayers because leavers were less likely to participate in the study. The apparent stability of the artistic precariat could be deceptive – what would happen if conditions became even more precarious? Is there a threshold (‘the straw that breaks the camel’s back’) where some sort of exodus is unleashed? With enduring uncertainty, fatigue, and futility, would entry and exit in performing arts change permanently? Or, conversely, have artists invested so much in education, identity, and pride (‘sunk cost’) that defection is no longer an option?

Regarding external validity, our study is situated within the music and performing art sector. We cannot conclude that the findings apply to sectors that were less hit by the closure of social arenas. In fact, for visual arts and the literature, overall income increased from 2019 to 2020 in Norway (Røed et al. Citation2021). Our data were collected in a developed welfare state that offers rather wide and tight social safety nets. While this may be seen as an idiosyncratic context, the notion of the artistic precariat seems no less applicable under harsher conditions.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abbing, Hans. 2008. Why Are Artists Poor? The Exceptional Economy of the Arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Arts Council Norway and Norwegian Film Institute. 2021. Kunnskapsoppsummering. Konsekvenser av Pandemien i Kultursektoren og Tiltak for Gjenoppbygging [Knowledge Summary. Consequences of the Pandemic in the Cultural Sector and Measures for Reconstruction], edited by Ministry of Culture. Oslo: Arts Council Norway.

- Ashton, Daniel. 2015. “Creative Work Careers: pathways and Portfolios for the Creative Economy.” Journal of Education and Work 28 (4):388–406. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2014.997685.

- Bain, Alison, and Heather McLean. 2013. “The Artistic Precariat.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (1):93–111. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rss020.

- Bennett, Dawn. 2009. “Academy and the Real World: Developing Realistic Notions of Career in the Performing Arts.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 8 (3):309–27. doi: 10.1177/1474022209339953.

- Bennett, Dawn, and Ruth Bridgstock. 2015. “The Urgent Need for Career Preview: Student Expectations and Graduate Realities in Music and Dance.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (3):263–77. doi: 10.1177/0255761414558653.

- Berg, Justin, Adam Grant, and Victoria Johnson. 2010. “When Callings Are Calling: Crafting Work and Leisure in Pursuit of Unanswered Occupational Callings.” Organization Science 21 (5):973–94. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0497.

- Blau, Gary J. 1988. “Further Exploring the Meaning and Measurement of Career Commitment.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 32 (3):284–97. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(88)90020-6.

- Boggess, CorrinaM. 2018. Clarity through Clearing: The Aesthetic Leader and Effective Sensemaking. University of Charleston, SC: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Bridgstock, Ruth, Ben Goldsmith, Jess Rodgers, and Greg Hearn. 2015. “Creative Graduate Pathways within and beyond the Creative Industries.” Journal of Education and Work 28 (4):333–45. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2014.997682.

- Brooks, Samantha K., and Sonny S. Patel. 2022. “Challenges and Opportunities Experienced by Performing Artists during COVID-19 Lockdown: Scoping Review.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 6 (1):100297– 13. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100297.

- Brown, Andrew D., Ian Colville, and Annie Pye. 2015. “Making Sense of Sensemaking in Organization Studies.” Organization Studies 36 (2):265–77. doi: 10.1177/0170840614559259.

- Campbell, Iain, and Robin Price. 2016. “Precarious Work and Precarious Workers: Towards an Improved Conceptualisation.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 27 (3):314–32. doi: 10.1177/1035304616652074.

- Cappelli, Peter, and James R. Keller. 2013. “Classifying Work in the New Economy.” Academy of Management Review 38 (4):575–96. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.0302.

- Cohen, Susanna, and Jane Ginsborg. 2021. “The Experiences of Mid-Career and Seasoned Orchestral Musicians in the UK during the First COVID-19 Lockdown.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:645967. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645967.

- Comunian, Roberta, and Lauren England. 2020. “Creative and Cultural Work without Filters: Covid-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy.” Cultural Trends 29 (2):112–128. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577.

- Cresswell, J. W., and V. L. Piano Clark. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Elstad, Beate, Erik Døving, and Dag Jansson. 2020. “Usikkerhet i koronaens tid. En studie av kulturarbeidere med ulike tilknytningsformer til arbeidslivet. [Uncertainty in the Times of the Corona Virus. A Study of Cultural Workers with Different Work Arrangements].” Søkelys på Arbeidslivet 37 (4):299–315. ER. doi: 10.18261/issn.1504-7989-2020-04-06.

- Elstad, Beate, Erik Døving, and Dag Jansson. 2021. “Konsekvenser av koronasituasjonen blant Creos medlemmer. Hovedresultater fra oppfølgingsundersøkelsen i januar-februar 2021. [Consequences of the Corona situation among Creo’s members. Main results from the follow-up survey in January-February 2021]”. Oslo: Oslo Metropolitan University.

- Elstad, Beate, Dag Jansson, and Erik Døving. 2022. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Cultural Workers. Fight, Flight or Freeze in Lockdown?” In Cultural Industries and the Covid-19 Pandemic. A European Focus, edited by Elisa Salvador, Trilce Navarrete and Andrej Srakar. London: Routledge.

- Elstad, Beate, JonIvar Pedersen, and Kjersti Røsvik. 1996. Kunstnernes Økonomiske Vilkår: rapport Fra Inntekts- og Yrkesundersøkelsen Blant Kunstnere 1993–94 [The Artists’ Financial Conditions: Report from the Income and Occupational Survey among Artists 1993–94], vol. 1996:1, INAS Rapport (Trykt Utg.). Oslo: Institutt for sosialforskning.

- Heian, MariTorvik, Knut Løyland, and Bård Kleppe. 2015. Kunstnerundersøkelsen 2013. Kunstnernes inntekter [The Artist Survey 2013. The Artists’ Income].

- Hennekam, S. 2017. “Dealing with Multiple Incompatible Work-Related Identities: The Case of Artists.” Personnel Review 46 (5):970–987. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2016-0025.

- Jansson, Dag, Beate Elstad, and Erik Døving. 2021. “The Construction of Leadership Practice: Making Sense of Leader Competencies.” Leadership 17 (5):560–585. doi: 10.1177/1742715021996497.

- Jensen, Kristin, and Kristine Nergaard. 2019. Kunst og Kultur – Organisasjoner i Endring? [Arts and Culture – Changing Organizations?]. Oslo: Fafo.

- Kalleberg, Arne L., and Steven P. Vallas. 2018. “Probing Precarious Work: Theory, Research, and Politics.” Research in the Sociology of Work 31 (1):1–30.

- Lee, Kibeom, Julie J. Carswell, and Natalie J. Allen. 2000. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Occupational Commitment: Relations with Person- and Work-Related Variables.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 85 (5):799–811. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.799.

- Leech, Nancy, and Anthony Onwuegbuzie. 2009. “A Typology of Mixed Methods Research Designs.” Quality & Quantity 43 (2):265–275. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3.

- Mangset, Per, Mari Torvik Heian, Bård Kleppe, and Knut Løyland. 2018. “Why Are Artists Getting Poorer? About the Reproduction of Low Income among Artists.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 24 (4):539–558. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2016.1218860.

- May, Tam Yeuk‐mui, Marek Korczynski, and Stephen J. Frenkel. 2002. “Organizational and Occupational Commitment: Knowledge Workers in Large Corporations.” Journal of Management Studies 39 (6):775–801. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00311.

- Menger, Pierre-Michel. 1999. “Artistic Labor Markets and Careers.” Annual Review of Sociology 25 (1):541–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.541.

- Meyer, John P., Natalie J. Allen, and Catherine A. Smith. 1993. “Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (4):538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538.

- Morrow, PaulaC. 1993. The Theory and Measurement of Work Commitment. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press.

- Ng, Pak Tee., and Charlene Tan. 2009. “Community of Practice for Teachers: sensemaking or Critical Reflective Learning?” Reflective Practice 10 (1):37–44. doi: 10.1080/14623940802652730.

- OECD. 2020. Culture shock: COVID-19 and the cultural and creative sector.

- Røed, TirilSalhus, JonMartin Sjøvold, LarsIvar Slemdal, and PederLaumb Stampe. 2021. Kunst i Tall 2020. Inntekter Fra Musikk, Litteratur, Visuell Kunstog Scenekunst [Arts in Numbers 2020. Income from Music, Literature, Visual Arts, and Performing Arts], edited by Arts Council Norway. Oslo: Arts Council Norway.

- Røyseng, Sigrid, Per Mangset, and Jorunn Spord Borgen. 2007. “Young Artists and the Charismatic Myth.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 13 (1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/10286630600613366.

- Salvador, Elisa, Trilce Navarrete, and Andrej Srakar, Eds. 2022. Cultural Industries and the Covid-19 Pandemic. A European Focus, 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Spiro, Neta, Rosie Perkins, Sasha Kaye, Urszula Tymoszuk, Adele Mason-Bertrand, Isabelle Cossette, Solange Glasser, and Aaron Williamon. 2020. “The Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown 1.0 on Working Patterns, Income, and Wellbeing among Performing Arts Professionals in the United Kingdom (April–June 2020).” Frontiers in Psychology 11:594086–594086. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594086.

- Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Steiner, Lasse, and Lucian Schneider. 2013. “The Happy Artist: An Empirical Application of the Work-Preference Model.” Journal of Cultural Economics 37 (2):225–246. doi: 10.1007/s10824-012-9179-1.

- Sturges, Jane, Michael Clinton, Neil Conway, and Alexandra Budjanovcanin. 2019. “I Know Where I’m Going: Sensemaking and the Emergence of Calling.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 114:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.006.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. Organizational Idenity. A Reader.” In Organizational Idenity. A Reader, edited by M. J. Hatch and M. Schulz, 56–65. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weick, Karl E. 1976. “Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems.” Administrative Science Quarterly 21 (1):1–19. doi: 10.2307/2391875.

- Weick, KarlE. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations, Foundations for Organizational Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.