ABSTRACT

Pregnancy represents a crucial timepoint to screen for disordered eating due to the significant adverse impact on the woman and her infant. There has been an increased interest in disordered eating in pregnancy since the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected the mental health of pregnant women compared to the general population. This systematic review is an update to a previous review aiming to explore current psychometric evidence for any new pregnancy-specific instruments and other measures of disordered eating developed for non-pregnant populations. Systematic searches were conducted in PubMed, ProQuest, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, MEDLINE, and Embase from April 2019 to February 2024. A total of 20 citations met criteria for inclusion, with most studies of reasonable quality. Fourteen psychometric instruments were identified, including two new pregnancy-specific screening instruments. Overall, preliminary psychometric evidence for the PEBS, DEAPS, and EDE-PV was promising. There is an ongoing need for validation in different samples, study designs, settings, and administration methods are required. Similar to the original review on this topic, we did not find evidence to support a gold standard recommendation.

Clinical implications

There is an ongoing need for further psychometric investigation of pregnancy-specific instruments and general measures of disordered eating to provide an evidence-based instrument for inclusion in perinatal health guidelines.

Since the original systematic review conducted by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), two new pregnancy-specific screening instruments have been developed: the Prenatal Eating Behaviour Screening tool (PEBS, 12 items) and the Disordered Eating Attitudes in Pregnancy Scale (DEAPS, 14 items). An Arabic version of the DEAPS has also been explored (A-DEAPS, 10 items).

The preliminary psychometric evidence for the PEBS and DEAPS is promising, suggesting that both instruments may be reliable, valid, and user-friendly; however, further research is required to confirm clinical utility.

A reduced version of the EDE-PV (11 items) also demonstrated promising psychometric properties in a sample of pregnant women with a BMI greater than 25.

There is an ongoing need for further psychometric investigation of pregnancy-specific instruments and general measures of disordered eating to provide an evidence-based instrument for inclusion in perinatal health guidelines.

Supporting and optimising the mental health of women during the perinatal period, inclusive of pregnancy and the first-year post-birth, has been identified as a global priority (United Nations, Citation2014; World Health Organisation, Citation2009). Regardless of severity, maternal mental health difficulties have been shown to critically impact a woman, her child, and her family (Bauer et al., Citation2016; Meltzer-Brody & Stuebe, Citation2014).

Identifying, monitoring, and supporting women with eating disorders (EDs) and disordered eating during pregnancy is crucial as such symptoms have been linked to several negative consequences such as miscarriage, prematurity, low birth weight, increased need for caesarean section, and other obstetric and postpartum challenges (Chan et al., Citation2019; Linna et al., Citation2014; Watson et al., Citation2017). Antenatal care is an opportune window to screen for those at risk of disordered eating due to more frequent contact with healthcare providers (National Eating Disorders Collaboration, Citation2015, Tierney et al., Citation2013); however, for such screening to occur the healthcare provider must possess appropriate knowledge and have access to psychometrically sound screening instruments (see Swan et al., Citation2023, for further information about measurement in healthcare).

Currently, there are several instruments cited in literature to measure disordered eating during pregnancy. A previous systematic review by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) found insufficient evidence at the time (search conducted until March 2019) to support the use of existing, traditional measures of disordered eating in the pregnant population, highlighting the need for pregnancy-specific measures of disordered eating to be developed and research exploring the validity of existing self-report ED inventories to be conducted in pregnancy samples. Use of traditional measures of disordered eating (which are developed in non-pregnant populations) could result in incorrect interpretations of instrument data (Myers & Winters, Citation2002), especially given the reported overlap between pregnancy-related symptomatology and disordered eating pathology (Bannatyne et al., Citation2018b). Previous research has also suggested disordered eating during pregnancy may manifest in unique pregnancy-specific features that traditional instruments do not capture (Bannatyne et al., Citation2018b).

Since Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) search was conducted (up to March 2019), the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Mounting evidence has revealed the pandemic disproportionally affected the mental health of pregnant and postpartum women, in comparison to the general population. In particular, the prevalence of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances increased in pregnant and postpartum women (Iyengar et al., Citation2021; Tauqeer et al., Citation2023). Numerous studies have also reported an increase in EDs and disordered eating associated with the COVID-19 pandemic across the lifespan (Linardon et al., Citation2022; McLean et al., Citation2022). As a result, there has been increased investigation into disordered eating during pregnancy.

The aim of this systematic review was to conduct a systematic literature update from Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021)’s review to explore current psychometric evidence for any new pregnancy-specific instruments and other measures of disordered eating developed for non-pregnant populations. Similar to Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), disordered eating was conceptualised in this review to encompass subclinical manifestations of ED symptoms. Other variations of disordered eating such as external eating, disinhibited eating, or emotional eating, were not considered. A secondary aim was to explore the administration burden of any identified instruments.

Method

Data search strategy

Searches were conducted in the following databases: PubMed, ProQuest, PsycInfo (Ovid), CINAHL, Scopus (Elsevier), MEDLINE Ovid, and Embase (Elsevier) from April 01, 2019 to February 19, 2024. The search strategy involved looking for literature pertaining to (i) eating disorders or disordered eating, (ii) pregnancy, and (iii) screening tools for ED or disordered eating. The search string was adapted from Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) and included Boolean terms: (“eating disorder* OR disordered eating OR inappropriate eating OR maladaptive eating OR problematic eating OR eating disturbance”) AND (“pregnan* OR antenatal OR perinatal OR intrapartum OR maternity*”) AND (“screen* OR questionnaire OR scale OR instrument OR measure OR assessment OR tool”). To ensure all appropriate articles were identified, reference lists, key journals, and grey literature were manually searched. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) was used as a methodological framework.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if the following criteria were met: (i) the sample was pregnant at the time of data collection, (ii) were published in English or a translation was available, and (iii) the reliability and/or validity of the measure were reported. If there were multiple studies that used the same sample and reported the same psychometric property of a disordered eating measure, only the first citation was included. Studies were excluded by the following criteria: (i) review article, (ii) retrospective study in the postnatal period, and (iii) longitudinal design that did not discern prepartum from postpartum datasets.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text articles, utilising Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2019). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with other members of the research team.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers with any disagreement being resolved by discussion or with a third reviewer. The information collected during extraction was as follows: author, country of publication, sample size, setting, recruitment method, date of data collection, sample characteristics, screening instrument and method of administration, time taken, and psychometric properties (validity and/or reliability). Data for the assessment of quality domains were extracted simultaneously.

Quality assessment

As per Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), the modified QUADAS score was utilised for quality assessment; developed by Whiting et al. (Citation2003) and modifications based on Meades and Ayers (Citation2011). The QUADAS contains the following 11 domains: 1) explicit study aims, 2) adequate sample size and/or justification, 3) sample described in sufficient detail, 4) population representative of sample receiving test/measure in practice, 5) inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly stated, 6) use of appropriate reference standard, 7) reliability of measure reported, 8) validity of measure investigated and reported, 9) participant withdrawals and dropouts clearly explained, 10) adequate description of data, and 11) discussion of generalisability. Domains were scored with a “0” if the criterion was unmet, and “1” if met. The scores were totalled for a score out of 11. Consistent with Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), studies that achieved a score of 8 or above were considered of reasonable quality.

Performance adequacy was analysed using standardised criteria previously utilised by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) which was developed by Terwee et al. (Citation2007). This performance criteria examines the psychometric properties of screening tools, encompassing domains of validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Screening tools are assigned a rating of “+” for positive evaluation, ”?” for intermediate evaluation, “-” for negative evaluation, or “0” when no information is available or reported for a particular domain in a study (see Supplementary File 1).

Results

Search results

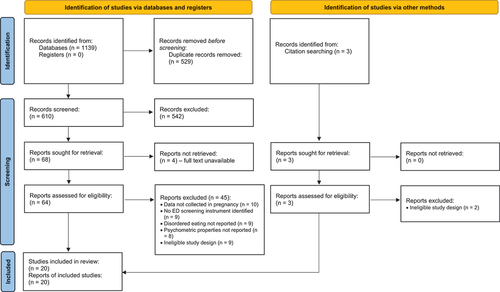

The literature search yielded 1139 potentially relevant citations. After duplicates were removed, 610 citations were title and abstract screened, with 64 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. After a full-text assessment, 19 citations met the criteria for inclusion. Backwards citation searching from the included studies revealed an additional three citations for consideration, one of these citations was just outside the date range and not included in the previous systematic review by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021). Given that the citation contained a new screening instrument, the authors made a consensus decision to include the citation. One additional citation from the backwards citation search met the criteria for inclusion. This resulted in a total of 20 citations for inclusion. Of these 20 citations, one publication (Dörsam et al., Citation2022) contained two studies with unpublished data from previous research. Two publications (Gerges et al., Citation2022, Citation2023) reported data from the same study/sample; however, were included as separate citations as each reported on different psychometric instruments. depicts the PRISMA flowchart of the article selection process.

Characteristics of included studies

Twenty citations based on 20 studies were included in this systematic review (). Studies included in this review were conducted in the USA (n = 7), Australia (n = 3), Germany (n = 2), UK (n = 1), Lebanon (n = 1), France (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Japan (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), China (n = 1), and split across USA and UK (n = 1). Sample sizes ranged from 42 to 1031 (<100 = 20%, 100–500 = 75%, 501–1031 = 5%). Fourteen studies (70%) were from a community setting, and six (30%) from primary care. The mean gestation at time of data collection ranged from 9 to 36 weeks. The women were aged between 19 t 37 years. Seventeen studies (85%) reported reliability in the form of internal consistency (see ). Only one study reported inter-rater reliability. Six studies (30%) reported validity, including content (n = 4), construct (n = 4), convergent (n = 3), and criterion-related (n = 5). See for further details.

Table 1. Overview of characteristics and demographics of included studies.

Table 2. Overview of screening instruments, methods of administration and psychometric properties in included studies.

Results of the modified QUADAS (see Supplementary File 2) indicated that most studies were of reasonable quality, defined as a quality assessment score of 8 or above. The lowest scoring domains were related to the use of an appropriate reference standard (23% of studies) and the validity of a measure being reported (33% of studies).

Psychometric tools identified

There were 14 screening instruments identified in this systematic review update, including: Prenatal Eating Behaviour Screening Tool (PEBS, n = 2), Disordered Eating Attitudes in Pregnancy Scale (DEAPS, n = 1), Arabic—Disordered Eating Attitudes in Pregnancy Scale (A-DEAPS, n = 1), Modified Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food (Modified SCOFF, n = 1), original SCOFF (n = 2), Eating Disorder Examination (EDE, n = 2), and the Eating Disorder Examination—Pregnancy Version (EDE-PV, n = 1), Eating Disorder Examination—Questionnaire (EDE-Q, n = 7), Eating Disorder Examination—Questionnaire Short (EDE-QS, n = 1), Eating Attitudes Test − 26 (EAT-26, n = 2), Eating Attitudes Test − 13 (EAT-13, n = 1), Eating Attitudes Test − 8 (EAT-8, n = 1), Eating Disorder Inventory − 2 (EDI-2, n = 3), and the Test for Orthorexia (ORTO-11, n = 1).

Of these instruments, PEBS and DEAPS were newly created screening tools for disordered eating during pregnancy. The A-DEAPS was an Arabic translation and modification of the DEAPS. The modified SCOFF and EDE-PV were pregnancy-specific modifications of general measures of disordered eating. The EDE, EDE-Q, EDE-QS, EAT-8, EAT-13, EAT-26, EDI-2, original SCOFF, and ORTO-11 were existing, general measures of disordered eating with no modifications for pregnancy.

Results for each instrument are reported individually in the following section. See for an overview of each of the instruments.

Table 3. Summary of psychometric instruments used in pregnancy samples in this review.

PEBS

The PEBS (Claydon et al., Citation2022) is a newly developed instrument designed to identify common ED presentations in pregnancy. Initial item development of the PEBS was based on items from existing general measures of disordered eating (e.g., EDE-Q, SCOFF, and EDI-3), in addition to pilot data themes from a previous study by the authors (Claydon et al., Citation2018).

The initial development and validation samples (Claydon et al., Citation2022) revealed a strong level of internal consistency (α = .96 and .91, respectively), confirmation of a unilateral structure (construct validity), and preliminary evidence of criterion-related with self-reported current ED diagnosis, using a cut-off score of 39 (development sensitivity = 80.7%, specificity = 79.7%; validation sensitivity = 69.2%, specificity = 86.5%). A separate study (Hormes, Citation2024) also revealed good internal consistency (α = .80).

DEAPS

The DEAPS (Bannatyne, Citation2018) is a newly developed (currently unpublished), brief instrument that aims to identify disordered eating attitudes in pregnancy. The original item pool was derived from symptoms that reached consensus across two Delphi panels (see Bannatyne et al., Citation2018b; Bannatyne et al., Citation2018a), reviewed and amended following consultation with 15 subject matter experts, and further refined after piloting with 12 pregnant women.

In initial psychometric analyses, the DEAPS demonstrated a high level of internal consistency (α = .85), appropriate content validity, evidence of a unilateral structure, convergent validity with the EDE-Q (r = .80) and SCOFF (r = .63), and concurrent criterion-related validity with a proxy gold standard (EDE-Q). Using various EDE-Q cut-off points identified in previous research, a cut-off score of 8 on the DEAPS demonstrated an overall sensitivity of 93.2% and specificity of 84.2% (AUC = .95).

A-DEAPS

The DEAPS was first developed by Bannatyne (Citation2018). Gerges et al. (Citation2022) conducted an Arabic translation of the DEAPS, labelled by the authors as the A-DEAPS. Exploratory factor analyses of the original 14 item-DEAPS (translated into Arabic) yielded a two-factor structure. Using confirmatory factor analysis, Gerges et al. (Citation2022) tested three models, with a one-factor model consisting of 10 items providing the best fit. Four items from the original DEAPS were removed in the A-DEAPS. In initial psychometric analyses, the A-DEAPS demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .80), evidence of construct validity, and convergent validity with the Restraint Subscale of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (Arabic version, r = .59) and SCOFF (Arabic version, r = .50).

Modified SCOFF

The modified SCOFF (Dörsam et al., Citation2022) is adaptation of the original SCOFF (Morgan et al., Citation1999) to be more appropriate for pregnancy. Initial psychometric analyses of the modified SCOFF (Dörsam et al., Citation2022) did not provide an estimate of internal consistency and revealed the modified SCOFF was more effective at identifying non-cases of lifetime ED history (as determined by the SCID) than correctly identifying cases when using cut-offs ranging from 1 to 4 (sensitivity = 8% to 62%; specificity = 67% to 100%).

Original SCOFF

The original SCOFF was administered as a secondary instrument in two studies (Bannatyne, Citation2018; Gerges et al., Citation2022). In Bannatyne (Citation2018), the original SCOFF had poor internal consistency (α = .41) but did have evidence of moderate convergent validity with the DEAPS (r = .63) and EDE-Q (r = .64). Similarly, in Gerges et al. (Citation2022), the Arabic version of the SCOFF had poor internal consistency (α = .41) but moderate convergent validity with the A-DEAPS (r = .50).

EDE

The EDE is a semi-structured interview to assess the frequency and severity of behaviours associated with an ED. It was created and validated for use in the non-pregnant population (Cooper & Fairburn, Citation1987). Jouppi et al. (Citation2024) who compared the EDE and EDE-PV, revealed appropriate internal consistency estimates for the EDE global score, Shape Concern subscale, and Weight Concern subscale (ω = .84, .84, and .73, respectively). Less than adequate internal consistency was reported for the Eating Concern subscale (ω = .67) and Dietary Restraint subscale (ω = .48). EFA analyses also revealed concerns about the factor structure of the EDE in a pregnancy sample, with nearly half the items excluded from the analysis due to low commonalities, including all Eating Concern subscale items and most Dietary Restraint subscale items. The other study in the current review that administered the EDE (Sommerfeldt et al., Citation2023) did not report any psychometric information.

EDE-PV

The EDE-PV is a modified pregnancy version of the EDE that excludes questions not applicable to the pregnant population (loss of menstruation and desire for a flat stomach) and includes the time periods before and during pregnancy. Using EFA, Jouppi et al. (Citation2024) revealed a two-factor solution for the EDE-PV, with analyses suggesting removal of all Eating Concern subscale items and most Dietary Restraint subscale items from the original EDE subscale. With the removal of those items, the Pregnancy Eating and Weight Change Concerns subscale (4 items) of the EDE-PV had acceptable internal consistency (ω = .70) and a moderate correlation with the Disinhibition subscale of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (r = −.37). The Pregnancy Shape and Weight Concerns subscale of the EDE-PV (7 items) had strong internal consistency (ω = .85) and a small correlation with the Disinhibition subscale of the TFEQ (r = −.14). The Global score for the EDE-PV also demonstrated good internal consistency (α =.84) and a small to moderate correlation with the Disinhibition subscale of the TFEQ (r = −.32). Tests of discriminant validity revealed that the EDE-PV differentiated between participants with and without lifetime histories of an ED (as determined by the SCID). Specifically, participants with lifetime histories of any eating disorder diagnosis had higher EDE-PV subscale and global scores than participants without.

EDE-Q

The EDE-Q (Fairburn & Beglin, Citation1994) is a self-report version of the EDE. Seven studies within the current review utilised the EDE-Q in pregnancy samples, with six studies (Bannatyne, Citation2018; Baskin et al., Citation2020; Christian et al., Citation2024; Hecht et al., Citation2021; Nagl et al., Citation2019; Vanderkruik et al., Citation2022) revealing excellent internal consistency (α = .89 to .95). Internal consistency of the EDE-Q was not reported by Sommerfeldt et al. (Citation2023). Only one study (Bannatyne, Citation2018) reported validity information for the EDE-Q in pregnancy in the form of convergent validity; the EDE-Q exhibited a strong, positive correlation with the DEAPS (r = .80) and moderate correlation with the SCOFF (r = .64). No other validity information was reported in any study.

EDE-QS

The EDE-QS is a short version of the EDE-Q. One study (He et al., Citation2023) included in this review reported excellent internal consistency (α = .92). No validity information was reported.

EAT

The EAT is a self-report measure originally designed to screen for symptoms of anorexia nervosa in non-pregnant individuals. The measure was revised to the EAT-26 (Garner et al., Citation1982). Various adaptations (shorter versions) have been published. Within this review, three versions will be discussed: EAT-26, EAT-13, and EAT-8.

Two studies (Dryer et al., Citation2020; Stubbs et al., Citation2019) in this review utilised the EAT-26 with good internal consistency (α = .87 in both). Validity information for the EAT-26 in pregnancy was not reported in either study. One included study (Incollingo Rodriguez et al., Citation2019) administered the EAT-13, with good internal consistency revealed (α = .83); however, validity information for the EAT-13 in pregnancy was not reported.

The EAT-8 was developed in a further attempt to increase efficiency as a brief, screening instrument. Within the synthesis published by Dörsam et al. (Citation2022), the diagnostic accuracy (criterion-related validity) of the EAT-8 was examined, with results revealing insufficient sensitivity and specificity using cut-offs of 2 or 3 (sensitivity = 100%; specificity = 36% to 59%). Dörsam et al. (Citation2022) did not report reliability information (e.g., internal consistency) for the EAT-8 in pregnancy.

EDI-2

The EDI-2 is a self-report questionnaire that assesses various psychological and behavioural features associated with EDs (Garner, Citation1991). Three studies in the current review utilised various subscales of the EDI-2. The Drive for Thinness subscale was administered in two studies (Goutaudier et al., Citation2020; Yamamiya & Omori, Citation2023), with good internal consistency revealed (α = .84 and .89, respectively). Goutaudier et al. (Citation2020) also administered the Bulimia subscale, with good internal consistency revealed (α = .81). The Body Dissatisfaction subscale was administered by Gerges et al. (Citation2023), with appropriate internal consistency reported (α = .81) and some evidence of convergent validity, with the Body Dissatisfaction subscale demonstrating moderate, positive correlations with the A-DEAPS (r = .45) and Restraint subscale of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Inventory (r = .35). CFA results of Gerges et al. (Citation2023) suggested a two-factor structure of the Body Dissatisfaction subscale.

ORTO-11

The ORTO-11 (Arusoglu et al., Citation2008) is a self-report questionnaire designed to cover various aspects of disordered eating behaviours and attitudes. One study (Taştekin Ouyaba & Çiçekoğlu Öztürk, Citation2022) in this review revealed poor internal consistency (α = .54) of the ORTO-11 in a pregnancy sample. No validity information for the ORTO-11 in pregnancy was reported.

Assessment of psychometric performance

The psychometric tools identified underwent evaluation according to the performance adequacy criteria (see Supplementary File 1 for descriptions). As shown in , the PEBS, DEAPS, and EDE-PV had five positive ratings across the nine domains. The modified SCOFF, A-DEAPS, and EDI-2 (Body Dissatisfaction subscale only) were assigned two positive ratings. All other measures had one or zero positive ratings.

Table 4. Psychometric performance using Terwee et al. (Citation2007).

Discussion

In the original systematic review on this topic, Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) revealed there was little to no psychometric evidence at the time to support the use of traditional measures of disordered eating in pregnancy, other than the EDE-Q which had preliminary evidence for possible utility. Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) identified a strong need for the development of pregnancy-specific instruments and further research exploring the psychometric properties of traditional measures of disordered eating in pregnancy samples. This systematic review update has highlighted an increased interest in the presence and manifestation of disordered eating in pregnancy over the past four years, with the development of two pregnancy-specific screening instruments (PEBS and DEAPS), a translation of one of the new pregnancy-specific instruments (A-DEAPS), pregnancy modifications to traditional measures of disordered eating (EDE-PV and modified SCOFF), and ongoing use of existing, traditional measures without any modifications.

New pregnancy-specific instruments

The PEBS (Claydon etal.Citation2022) and DEAPS (Bannatyne,Citation2018) are brief screening instruments (12 and 14 items, respectively) that can be completed in approximately five minutes, with the intention of identifying “high risk” cases for further consultation and assessment. Items on the PEBS focus more on behavioural signs of disordered eating, while the DEAPS items centre around attitudes and cognitions related to disordered eating. Previous research has indicated behavioural symptoms of disordered eating tend to be low or reduced during pregnancy, yet ED cognitions are often high (Blais et al.,Citation2000; Crow et al.,Citation2008; Easter et al.,Citation2013; Micali et al.,Citation2007).

Preliminary research with both scales has revealed good content validity, strong internal consistency, construct validity, and some evidence of concurrent criterion-related validity using self-reported current ED diagnosis for PEBS validation and various EDE-Q cut-offs for DEAPS validation. Both scale developers acknowledge that while comprehensive validation requires an accepted reference standard such as a clinical interview, the previous systematic review on this topic (Bannatyne et al., Citation2021) revealed insufficient evidence to support the utility of the traditional gold standard instrument (EDE interview) in pregnancy. At the time, the EDE-Q was the only instrument with preliminary evidence to suggest possible utility in pregnancy. As such, Bannatyne (Citation2018) used the EDE-Q as a gold standard proxy. While the development and initial validation of the PEBS and the DEAPS is promising, further psychometric exploration and validation is required to strengthen their utility. It should also be noted that the DEAPS is currently an unpublished instrument, with the scale developer intending to collect subsequent validation data before publication.

The DEAPS has also been translated into Arabic, labelled as the A-DEAPS (Gerges et al., Citation2022). The A-DEAPS involved some modification to the English DEAPS. Specifically, Gerges et al. (Citation2022) removed four items from the original DEAPS, resulting in a 10-item scale. The four items removed are related to binge eating and body image concerns, which Gerges et al. (Citation2022) noted do not characterise “pregorexia”. While the term “pregorexia” has circulated in popular media over the past decade, it is not a formally recognised diagnosis in the DSM-5 and typically describes women with features characteristic of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa, thereby failing to consider binge eating behaviours, the most prevalent eating disturbance during pregnancy (Bulik et al., Citation2007; Knoph Berg et al., Citation2011). As such, removal of these items may limit the scope of the A-DEAPS for screening all forms of disordered eating in pregnancy. Initial psychometric analyses have shown good internal consistency and preliminary evidence of construct validity. Criterion-related validity of the A-DEAPS has not been established and would be a warranted area for further research.

Pregnancy modifications to general instruments

The EDE-PV is a pregnancy-modified version of the EDE interview. The previous systematic review by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021) highlighted questionable internal consistency estimates with the EDE-PV global and subscale scores (Emery et al., Citation2017; Kolko et al., Citation2017) and a need for validation analyses. More recent research with the EDE-PV (Jouppi et al., Citation2024) has extended beyond item and time period modifications for pregnancy, identifying a two-factor solution (as opposed to the four-factor solution of the EDE), consisting of 11-items. When using the reduced EDE-PV, appropriate internal consistency was revealed for the global and subscale scores. The reduced EDE-PV also demonstrated preliminary evidence of convergent and discriminant validity with the lifetime history of an ED in a sample of pregnant women with a BMI greater than 25. These preliminary findings of the reduced EDE-PV are promising, with Jouppi et al. (Citation2024) acknowledging that future research across the weight spectrum is required.

The Modified SCOFF was the other traditional measure of disordered eating with pregnancy-specific modification, including adjustments for gestational weight gain and item changes to capture a broader range of purging behaviours. Initial psychometric exploration indicated the modified SCOFF was more effective at identifying non-cases of lifetime ED history than correctly identifying cases. Dörsam et al. (Citation2022) do caution the results may not necessarily reflect the screening abilities of the Modified SCOFF due to sampling and methodological limitations. Further exploration of the Modified SCOFF may, therefore, be warranted.

Use of general instruments in pregnancy

Similar to the findings of Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), most of the instruments used in pregnancy samples in this updated review were not pregnancy-specific (e.g., EDE-Q, EDE-QS, EAT-8, EAT-13, EAT-26, EDI-2 subscales, original SCOFF, ORTO-11), and the psychometric information (mostly internal consistency) was reported when describing the measures used in the study (rather than specific validation studies). In Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), the EDE-Q had the most psychometric information available, mostly in the form of internal consistency and construct validity. In the current review, the EDE-Q was the most frequently administered. Six studies indicated excellent internal consistency and one study provided evidence of convergent validity. Unfortunately, no studies using the EDE-Q in this review explored or reported construct or criterion-related validity for the EDE-Q. As such, while the EDE-Q appears to be reliable in pregnancy, its validity in pregnancy is still unclear.

Insufficient evidence precluded a thorough psychometric evaluation of the EDE-QS, EDI-2, EAT-8, EAT-13, EAT-26, original SCOFF, and ORTO-11, thereby limiting any recommendations regarding the suitability/appropriateness of these instruments in identifying or measuring disordered eating symptomatology in pregnancy.

Administration burden

A secondary aim of this updated review was to assess the burden of instrument administration. Notably, the PEBS, DEAPS, A-DEAPS, and modified SCOFF can be administered in less than 10 min, and do not involve complicated scoring. Previous research with expert researchers and clinicians has indicated that brief instruments are perceived to be most feasible for practitioners and women accessing antenatal care (Bannatyne et al., Citation2018a). Similarly, people with a lived experience of disordered eating report that screening prior to a more in-depth consultation contributes to preparedness and comfort in disclosing to the clinician (Fogarty et al., Citation2018). While the reduced EDE-PV takes longer to administer (though not as long as the EDE), it may be reserved for more in-depth assessment.

Recommendations for further research

It is clear from this updated review that while positive advances have been made in the development of two new pregnancy-specific instruments and pregnancy modifications to existing instruments, there is still a paucity of research in this area and the psychometric evidence available is preliminary and emerging. There is an ongoing need to further investigate the psychometric properties of the PEBS, DEAPS, A-DEAPS, EDE-PV, and modified SCOFF to firmly establish their clinical utility. The absence of a true gold standard measure in pregnancy is likely to have an ongoing impact on validation efforts, therefore researchers may consider use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (First, Citation2016) to identify lifetime history of ED diagnosis; however, this diagnostic instrument may not identify the broader experience of disordered eating and could be burdensome for researchers and participants to complete. The emerging evidence around the psychometric properties of the reduced EDE-PV is promising, but as yet, it cannot be considered a gold standard.

It is hoped that as further psychometric information becomes available in the future, carefully taking into account participant burden, explicit recommendations for clinical practice can be offered to guide both screening and more detailed assessment/monitoring of such symptoms in pregnancy. With telehealth and digital platforms for patient data being implemented across primary and secondary care, particularly since COVID-19, this may present an opportunity to explore the incorporation of digital screening strategies into perinatal care.

Limitations

Similar to the limitations experienced by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), the Terwee et al. (Citation2007) performance rating has been criticised by Burton et al. (Citation2016) as being conservative in the distribution of positive scores, potentially portraying instruments as insufficient. The absence of a positive score in a domain does not necessarily reflect inadequate performance, but in this review, it does highlight the absence of validation for most of the instruments.

Conclusion

This updated review revealed that two newly developed pregnancy-specific brief screening instruments (PEBS and DEAPS) and a pregnancy modification of an existing instrument (reduced EDE-PV) have promising psychometric evidence emerging. Ongoing validation in different samples, study designs, settings, and administration methods are required. Similar to the original review by Bannatyne et al. (Citation2021), we did not find evidence to support a gold standard recommendation. It is hoped that with further psychometric evidence, a comprehensive screening and assessment framework for disordered eating in pregnancy can be developed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arusoglu, G., Kabakci, E., Koksal, G., & Merdol, T. K. (2008). Orthorexia nervosa and adaptation of ORTO-11 into Turkish. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 19(3), 283–291.

- Bannatyne, A., Hughes, R., Stapleton, P., Watt, B., & MacKenzie-Shalders, K. (2018b). Signs and symptoms of disordered eating in pregnancy: A Delphi consensus study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1849-3

- Bannatyne, A. J. (2018). Disordered eating in pregnancy: The development and validation of a pregnancy-specific screening instrument. [Doctoral Dissertation, Bond University].

- Bannatyne, A. J., Hughes, R., Stapleton, P., Watt, B., & MacKenzie-Shalders, K. (2018a). Consensus on the assessment of disordered eating in pregnancy: An international Delphi study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21, 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0806-x

- Bannatyne, A. J., McNeil, E., Stapleton, P., MacKenzie-Shalders, K., & Watt, B. (2021). Disordered eating measures validated in pregnancy samples: A systematic review. Eating Disorders: Journal of Treatment and Precention, 29(4), 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1663478

- Baskin, R., Meyer, D., & Galligan, R. (2020). Psychosocial factors, mental health symptoms, and disordered eating during pregnancy. The International journal of eating disorders, 53(6), 873–882. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23264

- Bauer, A., Knapp, M., & Parsonage, M. (2016). Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005

- Blais, M. A., Becker, A. E., Burwell, R. A., Flores, A. T., Nussbaum, K. M., Greenwood, D. N., Ekeblad, E. R., & Herzog, D. B. (2000). Pregnancy: Outcome and impact on symptomatology in a cohort of eating-disordered women. The International journal of eating disorders, 27(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200003)27:2<140:AID-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-E

- Bulik, C. M., Von Holle, A., Hamer, R., Knoph Berg, C., Torgersen, L., Magnus, P., Stoltenberg, C., Siega-Riz, A. M., Sullivan, P., & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. (2007). Patterns of remission, continuation and incidence of broadly defined eating disorders during early pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1109–1118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000724

- Burton, A. L., Abbott, M. J., Modini, M., & Touyz, S. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of self-report measures of binge-eating symptoms and related psychopathology: A systematic review of the literature. The International journal of eating disorders, 49(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22453

- Chan, C. Y., Lee, A. M., Koh, Y. W., Lam, S. K., Lee, C. P., Leung, K. Y., & Tang, C. S. K. (2019). Course, risk factors, and adverse outcomes of disordered eating in pregnancy. The International journal of eating disorders, 52(6), 652–658. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23065Banna

- Christian, C., Zerwas, S. C., & Levinson, C. A. (2024). The unique and moderating role of social and self-evaluative factors on perinatal eating disorder and depression symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 55(1), 122–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2023.05.009

- Claydon, E. A., Davidov, D. M., Zullig, K. J., Lilly, C. L., Cottrell, L., & Zerwas, S. C. (2018). Waking up every day in a body that is not yours: A qualitative research inquiry into the intersection between eating disorders and pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18, Article 463.

- Claydon, E. A., Lilly, C. L., Ceglar, J. X., & Dueñas-Garcia, O. F. (2022). Development and validation across trimester of the Prenatal Eating Behaviors Screening tool. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25, 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01230-y

- Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. (1987). The eating disorder examination: A semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. The International journal of eating disorders, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:1<1:AID-EAT2260060102>3.0.CO;2-9

- Crow, S. J., Agras, W. S., Crosby, R., Halmi, K., & Mitchell, J. E. (2008). Eating disorder symptoms in pregnancy: A prospective study. The International journal of eating disorders, 41(3), 277–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20496

- Doersam, A. F., Moser, J., Throm, J., Weiss, M., Zipfel, S., Micali, N., Preissl, H., & Giel, K. E. (2022). Maternal eating disorder severity is associated with increased latency of foetal auditory event-related brain responses. European Eating Disorders Review, 30(1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2870

- Dörsam, A. F., Bye, A., Graf, J., Howard, L. M., Throm, J. K., Müller, M., Wallwiener, S., Zipfel, S., Micali, N., & Giel, K. E. (2022). Screening instruments for eating disorders in pregnancy: Current evidence, challenges, and future directions. The International journal of eating disorders, 55(9), 1208–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23780

- Dryer, R., Graefin von der Schulenburg, I., & Brunton, R. (2020). Body dissatisfaction and Fat Talk during pregnancy: Predictors of distress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.031

- Easter, A., Bye, A., Taborelli, E., Corfield, F., Schmidt, U., Treasure, J., & Micali, N. (2013). Recognising the symptoms: How common are eating disorders in pregnancy? European Eating Disorders Review, 21(4), 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2229

- Emery, R. L., Grace, J. L., Kolko, R. P., & Levine, M. D. (2017). Adapting the eating disorder examination for use during pregnancy: Preliminary results from a community sample of women with overweight and obesity. The International journal of eating disorders, 50(5), 597–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22646

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self‐report questionnaire? The International journal of eating disorders, 16, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(199412)16:4<363:aid-eat2260160405>3.0.co;2

- First, M. B. (2016). SCID-5-CV : structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders, clinician version. American Psychiatric Association.

- Fogarty, S., Elmir, R., Hay, P., & Schmied, V. (2018). The experience of women with an eating disorder in the perinatal period: A meta-ethnographic study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1762-9

- Garner, D. M. (1991). Eating disorder inventory-2: professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12(4), 871–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700049163

- Gerges, S., Obeid, S., & Hallit, S. (2022). Initial psychometric properties of an Arabic version of the disordered eating attitudes in pregnancy scale (A-DEAPS) among Lebanese pregnant women. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 175–175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00710-x

- Gerges, S., Obeid, S., Malaeb, D., Abir Sarray El, D., Hallit, R., Soufia, M., Fekih-Romdhane, F., & Hallit, S. (2023). Validation of an Arabic version of the eating disorder inventory’s body dissatisfaction subscale among adolescents, adults, and pregnant women. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00911-y

- Goutaudier, N., Ayache, R., Aubé, H., & Chabrol, H. (2020). Traumatic anticipation of childbirth and disordered eating during pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 38(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2020.1741525

- He, J., Zhang, X., Barnhart, W. R., Cui, S., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y., Yin, J., & Tan, C. (2023). Picky eating is associated with lower life satisfaction and elevated psychological distress and psychosocial impairment in Chinese pregnant women. The International journal of eating disorders, 56(9), 1807–1813. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23993

- Hecht, L. M., Schwartz, N., Miller-Matero, L. R., Braciszewski, J. M., & Haedt-Matt, A. (2021). Eating pathology and depressive symptoms as predictors of excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(13), 2414–2423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320913934

- Hormes, J. M. (2024). Preconception weight suppression predicts eating disorder symptoms in pregnancy. European Eating Disorders Review. Advance online publication. 32(4), 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3076

- Howard, L. M., Ryan, E. G., Trevillion, K., Anderson, F., Bick, D., Bye, A., Byford, S., O’ Connor, S., Sands, P., Demilew, J., & Pickles, A. (2018). Accuracy of the Whooley questions and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in identifying depression and other mental disorders in early pregnancy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.9

- Incollingo Rodriguez, A. C., Dunkel Schetter, C., Brewis, A., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2019). The psychological burden of baby weight: Pregnancy, weight stigma, and maternal health. Social Science & Medicine, 235, 112401–112401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112401

- Iyengar, U., Jaiprakash, B., Haitsuka, H., & Kim, S. (2021). One year into the pandemic: A systematic review of perinatal mental health outcomes during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 674194. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.674194

- Jouppi, R. J., Emery Tavernier, R. L., Call, C. C., Kolko Conlon, R. P., & Levine, M. D. (2024). Furthering development of the Eating Disorder Examination-Pregnancy Version (EDE-PV): Exploratory factor analysis and psychometric performance among a community sample of pregnant individuals with body mass index ≥ 25. Eating disorders, 32(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2259674

- Knoph Berg, C., Torgersen, L., Von Holle, A., Hamer, R. M., Bulik, C. M., & Reichborn Kjennerud, T. (2011). Factors associated with binge eating disorder in pregnancy. The International journal of eating disorders, 44(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20797

- Kolko, R. P., Emery, R. L., Marcus, M. D., & Levine, M. D. (2017). Loss of control over eating before and during early pregnancy among community women with overweight and obesity. The International journal of eating disorders, 50(5), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22630

- Linardon, J., Messer, M., Rodgers, R. F., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2022). A systematic scoping review of research on COVID-19 impacts on eating disorders: A critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. The International journal of eating disorders, 55(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23640

- Linna, M. S., Raevuori, A., Haukka, J., Suvisaari, J. M., Suokas, J. T., & Gissler, M. (2014). Reproductive health outcomes in eating disorders. The International journal of eating disorders, 46(8), 826–833. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22179

- McLean, C. P., Utpala, R., & Sharp, G. (2022). The impacts of COVID-19 on eating disorders and disordered eating: A mixed studies systematic review and implications. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 926709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.926709

- Meades, R., & Ayers, S. (2011). Anxiety measures validated in perinatal populations: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(1–2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.009

- Meltzer-Brody, S., & Stuebe, A. (2014). The long-term psychiatric and medical prognosis of perinatal mental illness. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.009

- Micali, N., Treasure, J., & Simonoff, E. (2007). Eating disorders symptoms in pregnancy: A longitudinal study of women with recent and past eating disorders and obesity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.003

- Morgan, J. F., Reid, F., & Lacey, J. H. (1999). The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ, 319(7223), 1467–1468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467

- Myers, K., & Winters, N. C. (2002). Ten-year review of rating scales. I: Overview of scale functioning, psychometric properties, and selection. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200202000-00004

- Nagl, M., Jepsen, L., Linde, K., & Kersting, A. (2019). Measuring body image during pregnancy: Psychometric properties and validity of a German translation of the Body Image in Pregnancy Scale (BIPS-G). BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 244–244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2386-4

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration. (2015). Pregnancy and eating disorders: A professional’s guide to assessment and referral. NEDC.

- Sommerfeldt, B., Skårderud, F., Kvalem, I. L., Gulliksen, K., & Holte, A. (2023). Trajectories of severe eating disorders through pregnancy and early motherhood. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1126941

- Stubbs, B., Hoots, V., Clements, A., & Bailey, B. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and efforts to quit smoking in pregnant women of South-Central Appalachia. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, 100174–100174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100174

- Swan, K., Speyer, R., Scharitzer, M., Farneit, D., Brown, T., Woisard, V., & Cordier, R. (2023). Measuring what matters in healthcare: A practical guide to psychometric principles and instrument development. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1225850. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1225850

- Taştekin Ouyaba, A., & Çiçekoğlu Öztürk, P. (2022). The effect of the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model variables on orthorexia nervosa behaviors of pregnant women. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(1), 361–372. 10.1007/s40519-021-01237-x

- Tauqeer, F., Ceulemans, M., Gerbier, E., Passier, A., Oliver, A., Foulon, V., Panchaud, A., Lupattelli, A., & Nordeng, H. (2023). Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A European cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 13(1), 063391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063391

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

- Tierney, S., McGlone, C., & Furber, C. (2013). What can qualitative studies tell us about the experiences of women who are pregnant that have an eating disorder? Midwifery, 29(5), 542–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.04.013

- United Nations. (2014). The millennium development goals report 2014.

- Vanderkruik, R., Ellison, K., Kanamori, M., Freeman, M. P., Cohen, L. S., & Stice, E. (2022). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in the perinatal period: an underrecognized high-risk timeframe and the opportunity to intervene. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25, 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01236-6

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2019). Covidence systematic review software. www.covidence.org/

- Watson, H. J., Zerwas, S., Torgersen, L., Gustavson, K., Diemer, E. W., Knudsen, G. P., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., & Bulik, C. M. (2017). Maternal eating disorders and perinatal outcomes: A three-generation study in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(5), 552. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000241

- Whiting, P., Rutjes, A. W. S., Reitsma, J. B., Bossuyt, P. M. M., & Kleijnen, J. (2003). The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-25

- World Health Organisation. (2009). Maternal mental health and child health and development in resource-constrained settings. WHO.

- Yamamiya, Y., & Omori, M. (2023). How prepartum appearance-related attitudes influence body image and weight-control behaviors of pregnant Japanese women across pregnancy: Latent growth curve modeling analyses. Body Image, 44, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.11.004