?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

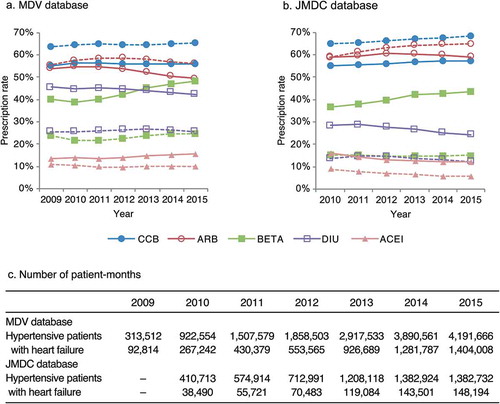

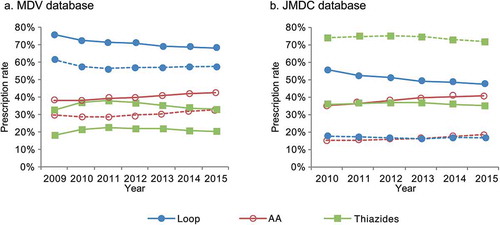

The number of patients with heart failure (HF) is rapidly increasing. Although hypertension is related to onset of HF, antihypertensive treatment status for these patients has not been fully examined. We conducted a claims-based study to discern the treatment status of Japanese hypertensive patients with HF. Two Japanese databases (2008–2016) from acute care hospitals and health insurance societies were used to analyze prescription rates for antihypertensive drug class or category of diuretics in all hypertensive patients and the subset of patients with HF. Totals of hypertensive patients and those with HF in each database in 2015 were 4,191,666 and 1,404,008 patient-months, and 1,382,732 and 148,194 patient-months, respectively. In the acute care hospitals database, calcium channel blockers (CCBs) (55.0–56.5%) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (49.4–54.7%) were prescribed most. β-blockers (38.7–48.0%) and diuretics (42.3–45.6%) were prescribed more for hypertensive patients with HF than for all hypertensive patients (21.5–24.8% and 25.5–26.7%, respectively). Loop diuretics were also prescribed more often for hypertensive patients with HF (68.3–76.0% from acute care hospitals and 47.8–55.8% from health insurance societies) than for all hypertensive patients (56.7–61.7% and 16.4–18.3%). The size of medical institution had a greater effect on drug selection than patient age in both patient groups. Given recommendations in guidelines for hypertensive patients with HF, the differences in drug choice in comparison with all hypertensive patients appear reasonable. However, some deviations, such as the high rate of CCBs in frontline and preference for angiotensin II receptor blockers over angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, did not appear to follow guidelines.

Introduction

The number of patients with heart failure (HF) has been rapidly increasing worldwide, including in Japan (Citation1,Citation2). Hypertension is reported to be the most frequent underlying cause of HF in epidemiological and registration studies (Citation3) and antihypertensive treatment reduces the incidence of HF in hypertensive patients (Citation4–Citation7). Many hypertensive patients require treatment with antihypertensive drugs to achieve the target blood pressure (Citation4–Citation8), and often various classes of antihypertensive drugs are used (Citation6,Citation8).

The 2017 guidelines by the Japanese Circulation Society/The Japanese Heart Failure Society (JCS 2017/JHFS 2017) recommend monotherapy with either angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (or angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs] (Citation9)), β-blockers, or a combination of the two for antihypertensive patients with comorbid HF who have reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (Citation10). Indeed, both ACE inhibitors (Citation11,Citation12) and β-blockers (Citation13–Citation15) improve the prognosis in patients with comorbid HF. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and diuretics can be added in patients without sufficient decreases in blood pressure (Citation10). In hypertensive patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), treatment is similar but tailored to individual patients, often favoring diuretics (Citation10). The overall approach in Japan largely mirrors that in the US and European guidelines (Citation16,Citation17).

However, in previous analysis, we found that choice of antihypertensive drugs in Japan did not always align with current treatment guidelines. For example, a CCB was the most commonly prescribed first-line drug for hypertensive patients with HF rather than renin-angiotensin (RA) system inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics (Citation18).

In the present study, we analyzed claims data to gain a comprehensive picture of the status of antihypertensive drug prescriptions in Japan; in particular, we investigated to what extent the guidelines have been followed for actual treatments in Japanese hypertensive patients with comorbid HF. The prescription rate for each drug class was investigated in association with patient age and size of the medical institution to examine factors that affect drug selection. As both our previous analysis (Citation18) and other previous work (Citation19) showed that use of diuretics in Japan is low, among all classes of antihypertensive drugs, treatment status of diuretics was specifically examined.

Methods

Study design and data sources

For this claims-based study, we used two databases provided by Medical Data Vision (MDV; Tokyo, Japan) and Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC; Tokyo, Japan). We analyzed data collected between April 2008 and April 2016 for the MDV database, and data collected between January 2010 and July 2016 for the JMDC database.

The MDV database includes information from acute care hospitals using the Japanese Diagnosis and Procedure Combination (DPC) fixed-payment reimbursement system. The MDV database includes 16 million individuals from 174 hospitals (11% of all DPC hospitals). All patients who received treatment in these hospitals are included regardless of the type of insurance. Because the records do not contain unique, hospital-independent patient identifiers, treatments given by other providers cannot be followed. Since the MDV database covers all patients receiving treatments in the hospital, regardless of age and type of insurance, the MDV database was mainly used for analyses of all the patient groups categorized by age.

The JMDC database includes information on people insured by health insurance societies, covering company employees and their family members, totaling approximately 3.8 million individuals (5% of all those insured) from more than 100 health insurance unions. The JMDC database includes limited information for individuals aged ≥65 years, and no information for those aged ≥75 years. Because the JMDC database includes a comprehensive record of all treatments, it was possible to determine when antihypertensive drugs were not being prescribed to particular patients. Therefore, first-line treatment could be identified in this database. The JMDC database was also used to compare treatment differences in patients of the medical institutions classified by size: clinics (defined as a setting with fewer than 20 beds) and hospitals (defined as a setting with 20 or more beds).

Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) were used for the statistical analyses.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We used unlinkable anonymized data that were exempted from obtaining approval of the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee, and individual informed consent based on Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Patient identification and analysis

We identified patients diagnosed at least once with hypertension according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10; coded as I10–I15) (Citation20). Hypertensive patients included in this study (defined as the general group) were the same as in our previous study: patients who received antihypertensive drugs at least once during the study period, between 2009 and 2015 for the MDV database and between 2010 and 2015 for the JMDC database (Citation18). Among them, the subgroup of patients with comorbid HF were identified as those diagnosed with HF (coded as I50) at least once (defined as the HF subgroup).

The definition of treatment with antihypertensive drugs was also the same as in our previous study (Citation18). Antihypertensive drugs were defined following the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System code. The classes of antihypertensive drugs analyzed were CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, β-blockers, renin inhibitors, centrally acting sympatholytic agents, and vasodilators. Diuretics were analyzed by category (loop diuretics, aldosterone antagonists, or thiazide diuretics) based on the general drug name. The prescription rate of the class (k) was calculated as:

First-line treatment was defined as a single-class antihypertensive drug prescription following a 6-month period with no antihypertensive drug prescriptions. First-line diuretic treatment was defined as the first single-category diuretic prescription. The prescription rate for first-line drugs was calculated for all of the patients who were initially prescribed antihypertensive drugs/diuretics, including those who received two or more classes/categories together.

The prescription rate in each class of antihypertensive drugs, or each category of diuretics, in all hypertensive patients and those with HF were calculated by year: 2009–2015 for the MDV database and 2010–2015 for the JMDC database. The same calculations were done for first-line treatments using the JMDC database only. Differences between all hypertensive patients and those with HF, age groups, and size of medical institution (clinics or hospitals) were compared.

Results

Patient identification

Among all of the patients diagnosed at least once with hypertension, 1,560,865 and 302,433 unique patients were extracted as those in the general group from the MDV database and the JMDC database, respectively. Numbers of patient-months in the general group and those in the HF subgroup used to calculate prescription rates, which were the sum of patients who received any antihypertensive drugs in each month in 2015, were 4,191,666 and 1,404,008 in the MDV database and 1,382,732 and 148,194 in the JMDC database, respectively (Table S1). Note that these represent patient-months rather than counts of unique patients.

Treatment status of antihypertensive drugs in hypertensive patients with HF

Prescription rates for each class of antihypertensive drugs for patients in the general group and HF subgroup each year in the MDV and JMDC databases are shown in . The trend was different for those in the HF subgroup (solid lines) by database: CCBs were the most frequently prescribed class, maintained at between 55.0% and 56.5%, and ARBs (49.4–54.7%) tended to decrease from 2010 onward in the MDV database (). On the other hand, over the entire study period the ARB prescription rate (58.9–60.6%) was higher than that for CCBs (55.0–57.3%) in the JMDC database (). Compared with prescription rates in the general group (dashed lines), prescription rates of ARBs and CCBs were lower and those for β-blockers, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors were higher in those in the HF subgroup in both databases ().

Figure 1. Prescription rate of antihypertensive drugs for both databases. The five most frequently prescribed classes for all hypertensive patients (dashed line: – -) and those with heart failure (solid line: ―) in the (a) MDV and (b) JMDC databases. ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BETA, β-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DIU, diuretic; JMDC, Japan medical data center; MDV, Medical data vision.

Prescription rates of ARBs and diuretics decreased modestly over time, while the rate of β-blockers increased in patients in the HF subgroup in all age groups: age <65 years, age ≥65 and <75 years, and age ≥75 years (Figure S1), which were patterns similar to those shown in all ages combined in the MDV database (). In 2015, numbers of patient-months were 280,051, 387,193, and 736,764 for <65 years, ≥65 years and <75 years, and ≥75 years, respectively (Table S1A); and the prescription rate of ARBs (51.2%) was slightly higher than that of CCBs (49.9%) in patients <65 years, while the prescription rate of CCBs (58.1%) was noticeably higher than that of ARBs (47.4%) in those ≥75 years (Figure S1). The use of β-blockers decreased but diuretics increased with age; prescription rates for β-blockers were 58.2% and 42.1%, and for diuretics 36.9% and 47.5%, in patients <65 years and those ≥75 years, respectively (Figure S1).

Regarding the size of the medical institution in the JMDC database, for hospitals the prescription rate of ARBs for patients in the HF subgroup gradually decreased from 57.6% in 2010, while for clinics the prescription rates increased until 2012 and stayed constant thereafter (Figure S2). CCBs and β-blockers tended to increase and diuretics to decrease over time in both hospitals and clinics (Figure S2). In 2015, numbers of patient-months were 62,549 and 87,717 for hospitals and clinics, respectively (Table S1B), while prescription rates of CCBs and ARBs were 51.0% and 52.1% in hospitals, around 10% lower than in clinics (61.2% and 63.0%, respectively) (Figure S2). β-blockers, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors were higher in hospitals, at 51.2%, 29.9%, and 16.3%, respectively, compared with clinics, at 37.6%, 19.9%, and 9.0%, respectively (Figure S2).

Treatment status of first-line antihypertensive drugs in hypertensive patients with HF

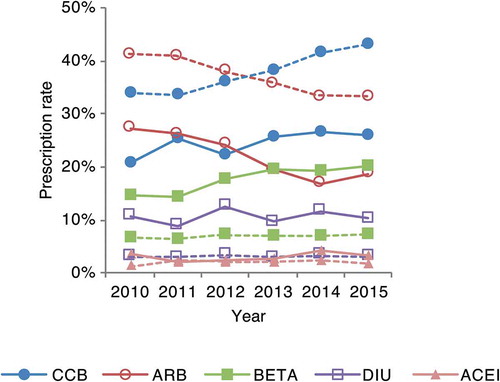

In the JMDC database, until 2012 ARBs were more often prescribed in both the general group (38.3–41.6%) and the HF subgroup (24.5–27.6%) than CCBs (33.9–36.4% and 21.3–25.6%) as the first-line antihypertensive drug for patients; thereafter, CCBs were most often prescribed from 2013 onward (38.6–43.5% and 26.0–26.8%) (). This seems to contrast with the HF treatment guidelines, which favor RA inhibitors and β-blockers before CCBs in patients with hypertension and HFrEF. The prescription rate of β-blockers steadily increased from 2011, reaching a rate similar to that of ARBs in 2013, and β-blockers were more frequently prescribed than ARBs in 2014 and thereafter in patients in the HF subgroup, but remained almost unchanged in patients in the general group (). In 2015, for 19,914 and 1310 patient-months of the general group and the HF subgroup (Table S1C), CCBs (43.5%) and ARBs (33.6%) were the main drugs prescribed in patients in the general group, while in patients in the HF subgroup various classes were prescribed: 26.4% for CCBs, 20.6% for β-blockers, 19.0% for ARBs, and 10.6% for diuretics ().

Figure 2. Prescription rate of first-line antihypertensive drug class in the JMDC database. The five most frequently prescribed classes for all hypertensive patients (dashed line: – -) and those with heart failure (solid line: ―). ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BETA, ß-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DIU, diuretic; JMDC, Japan medical data center.

The prescription pattern of first-line antihypertensive drugs in patients in the HF subgroup aged <65 years (Figure S3A) was similar to that in patients in all age groups (). For patients aged ≥65 and <75 years, the number of patients in the HF subgroup was small, 9 in 2010 and 93 in 2013 (Table S1C), and the order of prescription of the top four classes (CCBs, β-blockers, ARBs, and diuretics) changed each year (Figure S3B).

In both hospitals and clinics, the prescription rate of ARBs greatly varied each year in patients in the HF subgroup (Figure S3C and S3D). In 2015, for 799 and 511 patient-months of hospitals and clinics (Table S1C), the prescription rate of CCBs (25.7%) was slightly lower, while rates for β-blockers (22.5%) and diuretics (11.6%) were higher in hospitals compared with clinics, at 27.6%, 17.6%, and 9.0%, respectively (Figure S3C and S3D). The prescription rate of ARBs was highest in clinics, at 30.3% (Figure S3D) and was 11.8% in hospitals, which was lower than CCBs and β-blockers but similar to diuretics (Figure S3C).

Treatment status of diuretics by category in hypertensive patients with HF

Numbers of patient-months with any diuretic prescribed in 2015 were 1,074,335 for the general group and 594,255 for the HF subgroup in the MDV database (Table S1D), and 171,007 and 35,941 in the JMDC database (Table S1E). For nearly the entire study period, loop diuretics (MDV: 68.3–76.0%, JMDC: 47.8–55.8%) were most often prescribed, followed by aldosterone antagonists (MDV: 38.0–42.6%, JMDC: 35.2–41.1%) and thiazide diuretics (MDV: 18.3–22.2%, JMDC: 35.3–37.1%) in patients in the HF subgroup in both databases (). The prescription rate for loop diuretics decreased slightly over time in both databases, while that for aldosterone antagonists slightly increased. The prescription rate for thiazide diuretics remained constant over time. In the MDV database, loop diuretics were most often prescribed in patients in both the general group and the HF subgroup (). On the other hand, thiazide diuretics were more often prescribed, approximately 70%, and the prescription rates of aldosterone antagonists and loop diuretics were similar in patients in the general group in the JMDC database (). This finding is different from that in the HF subgroup in the JMDC database.

Figure 3. Prescription rate of each diuretic category for both databases. All hypertensive patients (dashed line: – -) and those with heart failure (solid line: ―) in the (a) MDV and (b) JMDC databases. AA, aldosterone antagonist; JMDC, Japan medical data center; MDV, Medical data vision.

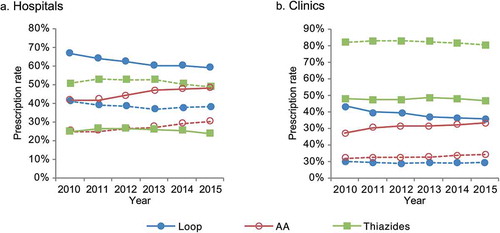

The order of prescription rate by category of diuretic was the same and the numerical rate in each category was similar among age groups in patients in the HF subgroup in the MDV database (Figure S4). By contrast, the order was different between hospitals and clinics in the JMDC database: thiazide diuretics (46.8–48.7%) were most frequently prescribed in clinics (), while they were less frequently prescribed (24.3–27.0%) than loop diuretics (59.7–66.9%) and aldosterone antagonists (41.9–47.9%) in hospitals ().

Figure 4. Prescription rate of each diuretic category for each medical institution in the JMDC database. All hypertensive patients (dashed line: – -) and those with heart failure (solid line: ―) in (a) hospitals and (b) clinics. AA, aldosterone antagonist; JMDC, Japan medical data center.

Numbers of patient-months with any diuretics prescribed for first-line treatment in 2015 were 672 for the general group and 139 for the HF subgroup (Table S1F). Over the entire study period, loop diuretics were the most frequently prescribed diuretics in patients in the general group (65.3–76.1%) and the HF subgroup (82.4–100%) in the JMDC database (Figure S5). Prescription rates of aldosterone antagonists (17.6–20.8%) and thiazide diuretics (14.6–22.3%) were similar in patients in the general group, while aldosterone antagonists (20.1–27.6%) were more common than thiazide diuretics (2.2–7.1%) in patients in the HF subgroup.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the treatment status of antihypertensive drugs in Japanese hypertensive patients with comorbid HF based on real-world data using two databases. For patients in the general group and the HF subgroup, CCBs and ARBs were the main antihypertensive drug classes. β-blockers were also frequently prescribed at a rate similar to that of CCBs and ARBs for patients in the HF subgroup. Diuretics and ACE inhibitors were more often prescribed for patients in the HF subgroup than for the general group. Differences in prescription choice were also seen for initial prescriptions; various classes of antihypertensive drugs were prescribed in patients in the HF subgroup, while CCBs and ARBs were most frequently prescribed in patients in the general group. These differences are reasonable when the recommendation of treatment with β-blockers, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors for patients with HFrEF in the JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 guidelines is considered (Citation10).

CCBs were frequently prescribed in patients in the HF subgroup at the same or greater rate than ARBs, although as first choice therapy, the Japanese guidelines do not strongly recommend CCBs for hypertensive patients with HF. One reason may be that CCBs are being selected without consideration for the recommendations for patients with comorbid HF, since CCBs have been frequently used for general antihypertensive treatment. It could also be that CCBs are prescribed for patients with HFpEF because antihypertensive drug recommendations for that population are not yet established. However, patients with a preserved ejection fraction could not be distinguished in this study. In addition, patients with HF were defined by only diagnoses on claims data; therefore, patients inaccurately diagnosed with HF might be included. A high prescription rate for CCBs, regardless of specialty, were also observed in the JCARE-GENERAL study, which examined the treatment status of Japanese HF patients based on analyses of patient registry databases (Citation3). In that study not all the patients had hypertension as comorbid per se, although the percentage of patients who had hypertension as an underlying cause of HF was high.

ACE inhibitors were prescribed with less frequency than ARBs in patients with HF. As for the RA system inhibitors, the JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 guidelines suggest that ACE inhibitors should be the first-line drug for antihypertensive treatment in patients with HFrEF, and ARBs should be used when there is no tolerance to ACE inhibitors (Citation9,Citation10). ACE inhibitors are recommended for antihypertensive treatment in various countries (Citation21–Citation24) based on evidence (Citation11,Citation12). However, in East Asian populations a higher incidence of adverse effects, such as coughing, has been reported to be associated with ACE inhibitors (Citation25), resulting in a lower dose being prescribed for Japanese patients in comparison with Western countries. In most clinical trials that showed evidence of a blood pressure-lowering effect in Western countries, patients received a dose of ACE inhibitors larger than the maximum dose in Japan. For example, participants in CONSENSUS (Citation11), a study that included Finland, Norway, and Sweden, received a daily dose of ACE inhibitor (enalapril) that ranged from 10 to 40 mg (average 18.4 mg), which is larger than a daily dose for antihypertensive treatment in Japan (5–10 mg) (Citation26). Lower doses consequently suppress the blood pressure-lowering effects in these populations. Therefore, ARBs are likely to be more frequently selected than ACE inhibitors as the class of RA system inhibitors in Japan. Additionally, we speculate that the decrease in ARB prescriptions over time may have been caused by retraction of some clinical studies of ARBs that were conducted in Japan (Citation27), thus reflecting a lack of confidence in these agents for Japanese patients.

Regarding the category of diuretics, a difference between patients in the general group and the HF subgroup was also observed in the JMDC database. Thiazide diuretics were more often prescribed in patients in the general group, while loop diuretics were more common in patients in the HF subgroup. Comparing hospitals and clinics in the HF subgroup, thiazide diuretics were most frequently prescribed in clinics while loop diuretics were most frequently prescribed in hospitals. Loop diuretics and aldosterone antagonists were frequently prescribed for patients in both the general group and the HF subgroup in the MDV database. Loop diuretics provide a more pronounced diuretic effect but have a lesser blood pressure-lowering effect than thiazide diuretics (Citation28); therefore, thiazide diuretics are more commonly used as an antihypertensive drug (Citation29). Loop diuretics are generally used as HF treatment to reduce symptoms caused by congestion (Citation10). Aldosterone antagonists reduce the risk of both morbidity and death among patients with severe HF when added to standard therapy (Citation30). Aldosterone antagonists, in particular, are recommended for patients with severe or refractory HF (Citation10). Therefore, the results suggest that treatment of hypertension might be prioritized in clinics, while treatment of HF might be a priority over that of hypertension for patients in the HF subgroup in hospitals, including DPC hospitals.

The selection of the class of antihypertensive drugs and the category of diuretics in patients in the HF subgroup varied more based on medical institution than based on patient age. In clinics, CCBs and ARBs were preferred in patients in the general group and were clearly preferred for patients in the HF subgroup as well. Less preference was observed in hospitals where β-blockers, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors were also routinely used. The preference for diuretics by category in patients in the HF subgroup was more similar to patients in the general group in clinics compared with hospitals. These observations may arise from differences in the percentages of specialists, who, one assumes, would be more likely to comply with specific treatment guidelines, as well as the severity of the symptoms between hospitals and clinics, as in clinics, a much greater emphasis is often placed on treatment safety profiles such as dry cough.

This study has potential limitations. Hypertension and HF were defined based on diagnoses according to the ICD-10 code. Therefore, coding accuracy is crucial in extracting appropriate patients, and analyses by subtype of HF could not be conducted. Although we examined prescription of antihypertensive drugs for hypertensive patients, prescriptions may not have been specified for treatment for hypertension because some drugs have indications for the treatment of conditions other than hypertension. Moreover, each database is inherently biased because of characteristics of data sources. The MDV database included data from only DPC hospitals; therefore, bias could exist in terms of clinical history and disease severity. The JMDC database included data of individuals insured by health insurance societies; therefore, the age distribution was different from that of the general Japanese population, and living standards stemming from employment could show bias. Despite these limitations, we used these two databases appropriately, and they were compared in a consistent manner to ensure the analysis was as robust and representative as possible.

In conclusion, we analyzed the treatment status of antihypertensive drugs prescribed to hypertensive patients with comorbid HF. There was a tendency for prescriptions to follow recommendations in the guidelines for hypertensive patients with comorbid HF compared with all hypertensive patients. However, some treatments that did not appear to follow the guidelines, such as the high proportion of patients receiving first-line CCBs or the preference for ARBs over ACE inhibitors, were also observed. Considering the differences in prescription status for hypertensive patients with HF compared with hypertensive patients in general, patients with other comorbidities should also be examined to help determine treatment status and appropriate treatment strategies for patients with each comorbidity mentioned in the guidelines.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (555.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Shinzo Hiroi, PhD, at the time employed by Takeda for contributing to the study design, and interpretation of data, respectively. We would also like to thank Kosuke Iwasaki, MBA, Yujiro Otsuka, Bsc and Tomomi Takeshima, PhD, employees of Milliman, for performing data analysis, and providing the manuscript draft and editorial support, respectively.

Disclosure Statement

MO has received honoraria from MSD, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Novartis Pharma, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, fees for promotional materials from Kyowa Kikaku, research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, and scholarships or donations from MSD, Astellas, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Boehringer Ingelheim. TY, NN, AO, and YS are employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Konishi M, Ishida J, Springer J, von Haehling S, Akashi YJ, Shimokawa H, Anker SD. Heart failure epidemiology and novel treatments in Japan: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2016;3(3):145–51. doi:10.1002/ehf2.12103.

- Shimokawa H, Miura M, Nochioka K, Sakata Y. Heart failure as a general pandemic in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(9):884–92. doi:10.1002/ejhf.319.

- Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kinugawa S, Goto D, Takeshita A, Investigators J-G. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with heart failure in general practices and hospitals. Circ J. 2007;71(4):449–54.

- Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213(7):1143–52. doi:10.1001/jama.1970.03170330025003.

- Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–98. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801369.

- Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi:10.1136/bmj.b902.

- Moser M, Hebert PR. Prevention of disease progression, left ventricular hypertrophy and congestive heart failure in hypertension treatment trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(5):1214–18. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00606-0.

- Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N, Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists Collaboration. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood pressure lowering treatment trialists’ collaboration. Lancet. 2000;356(9246):1955–64.

- Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Investigators C, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9386):772–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5.

- Japanese Circulation Society. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure (JCS 2017/JHFS 2017). Tokyo: Japanese Circulation Society; 2018. http://www.asas.or.jp/jhfs/pdf/topics20180323.pdf. [Japanese].

- CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the cooperative North Scandinavian enalapril survival study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med. 1987; 316(23):1429–35. doi:10.1056/NEJM198706043162301.

- Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN, SOLVD Investigators, Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(5):293–302. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108013250501.

- Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B, Wedel H, Waagstein F, Kjekshus J, Wikstrand J, El Allaf D, Vitovec J, Aldershvile J, et al. Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: the metoprolol CR/XL randomized intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). MERIT-HF study group. JAMA. 2000;283(10):1295–302.

- Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, Katus HA, Krum H, Mohacsi P, Rouleau JL, Tendera M, Castaigne A, Roecker EB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(22):1651–58. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105313442201.

- Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, Coats AJ, Katus HA, Krum H, Mohacsi P, Rouleau JL, Tendera M, Staiger C, et al. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation. 2002;106(17):2194–99.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart failure society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137–e161. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–200. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128.

- Ohishi M, Yoshida T, Oh A, Hiroi S, Otsuka Y, Takeshima T. Analysis of antihypertensive treatment using real-world Japanese data ― REtrospective study of antihypertensives for lowering blood pressure (REAL) study. Hypertens Res. Forthcoming.

- Kohro T, Yamazaki T, Sato H, Ohe K, Nagai R. The impact of a change in hypertension management guidelines on diuretic use in Japan: trends in antihypertensive drug prescriptions from 2005 to 2011. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(6):559–63. doi:10.1038/hr.2012.216.

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Statistical classification of diseases and cause of death. Tokyo: Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare; 2013. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/sippei/. [Japanese].

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, McBrien K, Butalia S, Zarnke KB, Nerenberg K, Harris KC, Nakhla M, Cloutier L, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557–76. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of hypertension (ESH) and of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2159–219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management: clinical guideline [CG127]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006.

- McDowell SE, Coleman JJ, Ferner RE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in risks of adverse reactions to drugs used in cardiovascular medicine. BMJ. 2006;332(7551):1177–81. doi:10.1136/bmj.38803.528113.55.

- Kk MSD. Enalapril maleate [Renivace] package insert. Tokyo: MSD KK; 2018. http://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/170050_2144002F1024_2_12. [Japanese].

- Japanese Society of Hypertension. Japanese society of hypertension official comment on valsartan papers. Hypertens Res, 2013;36(11):923.

- Sica DA, Carter B, Cushman W, Hamm L. Thiazide and loop diuretics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(9):639–43. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00512.x.

- Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ishimitsu T, Ito M, et al. The Japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37(4):253–390. doi:10.1038/hr.2014.20.

- Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized aldactone evaluation study investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):709–17. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909023411001.