How health providers and clinical scientists obtain mechanistic information to improve their practice

Clinical healthcare practitioners face a fundamental challenge in maintaining up-to-date expertise in their field while spending the majority of their time on clinical practice rather than knowledge acquisition. While the application of knowledge is, by definition, the primary duty of the clinician, understanding how practitioners acquire new knowledge, and how knowledge gained in the research community can be more effectively transferred to the clinical setting, is essential.

The preferred source for information varies with the therapeutic field. Medical physicians have historically relied upon colleagues for information used in practice [Citation1]. Physical therapists have used journal publications and PubMed searches as methods to improve or update their understanding of clinical practice [Citation2]. Both chiropractors [Citation3] and physical therapists [Citation4] have invested in continuing education, with physical therapists ranking it as the most influential aspect of learning acquisition. Indeed, the Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE) accreditation standards include a meta-competency in Information and Technology Literacy, preparing students to ‘locate, critically appraise and use relevant scientific literature and other evidence.’

The use of the internet and social media has grown to dominate evidence acquisition, and despite the guidance such as from the CCE, the amount of use of the scientific literature by practitioners is not well measured. It has been reported that over 90% of physicians use the internet to research clinical issues (e.g. WebMD), making it the most common professional internet activity for physicians [Citation5]. Additionally, 70% of doctors claim the internet has influenced treatment and assisted in the diagnosis of patients [Citation5]. Medical physicians commonly use news sites and blogs both for professional and marketing reasons [Citation6]. A reliance on social media has both pros and cons [Citation7]. There is a danger of receiving false information [Citation8]. Notable amounts of misinformation have been reported, even among sites that attempt to provide useful healthcare tips and strategies [Citation9]. This has led to a lack of believability among health providers, specifically in areas such as the use of manual therapy [Citation10].

The clinical and research communities interested in these subjects bear the responsibility to make a concerted effort to coalesce and disseminate up-to-date information on all the different areas of research that may improve practice. These areas may include practical knowledge of common practices/techniques, but also basic science knowledge of the tissue mechanics, mechanotransduction, and the major pathways that connect skin to the brain regions that modulate well-being and pain relief. Bioengineering research has made progress on various fronts, including the development of better computational models [Citation11], the use of animal, ex vivo, and in vitro models for injury and treatment [Citation12], and the use of novel imaging and image analysis methods to analyze motion and brain responses [Citation13]. In addition, there’s many new exciting advances in the basic neurobiology of touch, including the discovery of mechanosensitive channels (Piezos [Citation14] and new research in our understanding of the skin-to-brain connections that tap into brain centers of ‘well-being’ [Citation15,Citation16]. These new advances represent an exciting opportunity for interactions between basic neuroscientists, physicians, engineers and technologists, and practitioners.

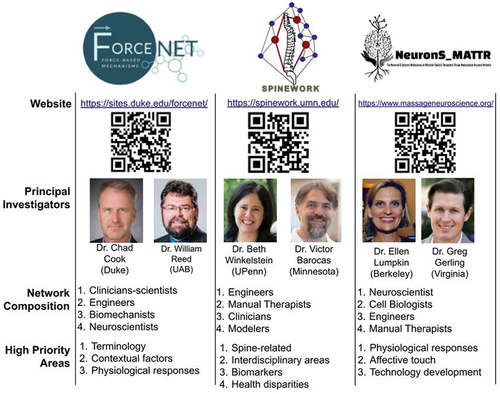

In an effort to nucleate these different fields and facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations, NCCIH and NINDS have jointly funded three U24 network grants. This report summarizes the objectives and deliverables of these network grants to raise awareness of their work, attract interested members, and excavate commonalities, as well as raising the challenges facing the field. Additionally, this report aims to provide clinicians with valuable context for the ongoing research included in these network grants, thus enhancing their knowledge of the appropriate use of manual therapies in the management of patients with pain.

Individual U24 network objectives

The research network deliverables are three-fold: 1) To establish flexible, highly-connected communities that conceive, develop, and guide the development of overarching research ideas to facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations between manual therapy practitioners and neuroscientists and engineers regarding FBM research, 2) to disseminate resources, products, and opportunities to a wider research and public audience, and 3) to increase interdisciplinary collaborative research through pilot awards, summer schools, workshops, educational content, and conferences. Here is a summary of three recently funded U24 research networks ( and also available on this NCCIH landing page).

ForceNet: Whereas a large body of mechanosensation knowledge exists, synergy between our current understanding of sensory mechanotransduction and FBM mechanisms across research disciplines remains severely limited. The lack of synergy between research fields has proven to be a formidable barrier to the advancement and therapeutic optimization of FBM. To accelerate interdisciplinary collaborative research and advance the FBM field, we aim to establish an international academic and professional Force-Based Manipulation network (ForceNet). The charge of ForceNet is to successfully overcome the long-established barriers pertaining to: 1) the lack of universal FBM force-related metrics, 2) the lack of FBM mechanistic knowledge (including how mechanosensitive receptors, neurons, and circuits change in pathological conditions), and 3) the undefined but potentially critically important role of contextual factors on FBM mechanisms. To accomplish those goals, the network will stimulate interdisciplinary research at the intersections of physiology, biomechanics, big data/artificial intelligence, neuroscience, immunology, imaging, and psychology. ForceNet will support the development of new interdisciplinary collaborations and the submission of novel experimental and translational pre-clinical pilot projects. These pilot project initiatives will encompass basic, theoretical framework, and translational designs, primary and secondary analyses, new and ancillary projects, and will be open to investigators across the entire academic career spectrum. ForceNet aims to grow and diversify the FBM workforce, develop a pipeline of new FBM interdisciplinary investigators, and encourage new collaborations between larger research-intensive public universities and smaller Integrative Medicine institutions. ForceNet will use a variety of avenues to create and share new FBM knowledge and resources including performing a FBM Delphi Study, publishing 6-10 articles in a special issue of Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, hosting face-to-face and virtual workshops and webinars designed to encourage new interdisciplinary FBM collaborations. ForceNet will create an interactive website where ForceNet members can locate future interdisciplinary collaborators and use social media to promote and share Network resources. Pilot grant awardees will present their research findings at annual ForceNet workshops. To sustain ForceNet network growth after the funding period ends, we will establish ForceNet ‘special interest groups,’ satellite events, and social events at large national/international scientific meetings in which ForceNet members attend regularly and/or serve in a leadership capacity. As current leaders in the field of basic and clinical FBM research, the resources provided to the ForceNet Leadership Team along with our highly visible institutions and established personal networks of interdisciplinary collaborators make this group well-positioned to substantially impact FBM mechanistic research and clinical care for decades to come. Overall, the mission of ForceNET is the emphasis of clinically translationally relevant research addressing FBM metrics of applied force, neural mechanisms of FBM mechanotransduction, and FBM contextual effects. ForceNET’s focus is on mechanisms research that has potential clinical ramifications.

SPINEWORK: Low back and neck pain impose major impediments to quality of life, are responsible for significant productivity loss, and are often treated with expensive, sometimes ineffective, and potentially addictive drugs. Complementary therapies, especially FBM, have the potential to address these challenges, but remain poorly understood especially for spine pain. The highly multifaceted nature of FBM and physiologic mechanisms involved with putative or real pain relief are currently discordant, requiring the integrative synthesis of neuroscience, physics, engineering, physiology, and clinical fields. To address this need, the SPINEWORK network brings together researchers from all disciplines interested in exploring the potential role of FBM in alleviating spine pain. The network provides members with the opportunity to identify new collaborators, to learn about other disciplines, to disseminate ideas and information to their colleagues and the larger community, and to foster better interdisciplinary communication. SPINEWORK supports the network of researchers and activities administered by a set of committees and will be organized into intersecting and evolving content-specific Working Groups, each made up of members from multiple institutions and traditional disciplines and focused on specific areas, such as Clinical Needs, Imaging or Experimental Models. The Working Groups promote interdisciplinary research through physical and virtual gatherings, white papers, journal special issues, and video content. Across SPINEWORK and the other two networks, a working group dedicated to Taxonomy and Terminology focuses on defining a common lexicon for spine pain (SPINEWORK-specific) and forced-based manipulations. This task is essential because even simple terms can have very different meanings to different communities, leading to confusion and impeding progress for collaborative teams. SPINEWORK sponsors pilot and facilitation grant programs for interdisciplinary collaborative teams formed by its members, with the goal of seeding or boosting larger scale parent proposals, activities that build intellectual infrastructure (e.g. think tanks or workshops), and opportunities for scientists from one discipline to immerse in disciplines outside their core area. Annually, SPINEWORK brings its members together for a Summit meeting to assess its activities, report findings, review and spawn new Working Groups, review progress, and plan for the coming year. Overall, SPINEWORK’s mission is to lay the intellectual groundwork for improved treatment of low back and neck pain using FBMs by creating and fostering a multidisciplinary, scientifically and culturally diverse network of researchers from across the spectrum of approaches to understand FBM and spine pain.

Neuronal & Systems Mechanisms of Affective Touch & Therapeutic Tissue Manipulation Research (NeuronS_MATTR) Network: Despite the recognized therapeutic potential of soft tissue manipulation (STM), there remains a significant gap in the holistic understanding of its underlying biological and neurological mechanisms, as well as its optimized implementation based on rigorous scientific backing. The goal of this network is to identify mechanisms through which soft tissue manipulation (STM), such as massage, exerts biological effects on the nervous system, non-neural cells, and somatic tissues. Neuromusculoskeletal pain afflicts up to half of the adult U.S. population and is the most commonly cited health reason for receiving massage. Soft tissue manipulation has been shown to promote relaxation, reduce anxiety, attenuate pain, mitigate inflammation, and promote functional change. STM also offers non-addictive alternatives to pharmacological interventions for short-term pain relief. Although STM has been used widely since ancient times, the underlying mechanisms of STM’s beneficial effects are not well understood, and STM interventions are not optimized based on rigorous and compelling scientific evidence. Although mechanistic studies over the past decade have identified molecular, cellular, and circuit mechanisms of discriminative touch sensation in mammals, how these neural pathways are engaged by STM is unknown. Moreover, the cells and circuits that mediate the affective components of touch sensation have not been defined. To enable mechanistic research into the therapeutic effects of STM, interdisciplinary research and new resources are needed. The field requires collaboration between manual therapists, neuroscientists, engineers, and cell biologists. Scientific conferences or other networking opportunities that bridge these disciplines are scarce. First, few quantifiable standards exist to rigorously measure either how therapists apply hands-on manipulations, or how these manipulations alter stress/strain fields in receiving tissues. Second, the field lacks technologies and computational models to quantify the spatiotemporal dynamics of STM techniques. Third, how non-neural signals and cell types, including cytokines, immune cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells, promote restorative repair versus fibrotic healing have not been defined. Our core investigative team consists of scientists and clinicians whose collective expertise spans physical therapy, neuroscience, engineering and tissue mechanics, and extraneural tissues including the immune, myofascial, and integumentary systems. The network will focus on three high-priority areas: 1) Mechanistic multiscale research measuring the physiological response to force-based manipulations in neural and non-neural cells and tissues, 2) Mechanistic understanding of the neurobiological basis of the psychosocial sense of affective touch, and how affect/mood modulates neural & physiological responses to mechanical stimuli, 3) Technology and methodology development for mechanistic studies, including computational approaches. To advance these three high-priority areas, the Neurons_MATTR aims to 1) Organize a Conferences Program to promote inclusive networking and cross-disciplinary collaborations, draw diverse researchers and clinicians to the field, and foster mechanistic, multi-scale research on the neurobiology of mechanotherapy. 2) Implement a Pilot Project Program to generate new tools for quantifying force-based manipulations, testable hypotheses, and new mechanistic knowledge. 3) Rapidly and freely disseminate high-impact research to advance the field by sharing innovative concepts and technologies that define neural mechanisms of the beneficial effects of STM. Overall, the goal of NeuronS_MATTR is to bridge interdisciplinary gaps, foster collaborative innovations, and pave the way for a more comprehensive, evidence-based application of soft tissue manipulation in therapeutic settings.

U24 cross-network group efforts

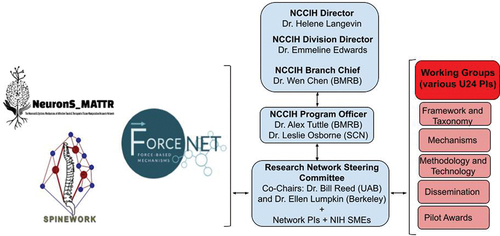

By definition, force-based manipulation involves the application of a force to the body. In addition, if one is considering pain, that therapy must, directly or indirectly, affect the nervous system, although not necessarily at the point of the force application. These two essential features, the application of force and the interaction of that force with the nervous system, form the foundation for two of our three U24 networks, ForceNet and Neurons_MATTR. The third U24 network, SPINEWORK, addresses both of those two effects but with a specific focus on their relationship to alleviating spine pain. All three networks interact synergistically to promote the development and dissemination of knowledge that can help improve force-based manipulative therapies. To this end, all U24 PIs and NCCIH leaders are working together to identify key areas for cross-network focus groups (). The purpose of those working groups is to address cross-cutting concerns/objectives among all three U24 networks:

Figure 2. Summary of how U24 networks pls and NCCIH leadership are working together to nucleate this new field.

Framework and Taxonomy: Develop overarching research frameworks and common terminologies to facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations between therapists, clinicians or interventionists using biomechanical forces and neuroscientists regarding Force-Based Manipulations research.

Mechanisms: Collaborate with the Framework and Taxonomy working group to further refine the classifications of mechanistic targets of force-based manipulations

Methodology and Technology: Evaluate current technologies and methodologies used to measure different types of forces used in FBMs in human studies and in other organismal or in-silico models

Dissemination: Develop and implement effective ways to disseminate the scientific deliverables from the Scientific Working Groups (e.g. research resources, major scientific advances, and publications, funding opportunities) to a wider research and public audience.

Pilot awards: Coordinate pilot award application processes across three different research networks to minimize redundancies and optimize timing and impact.

A summary of these joint efforts is depicted in .

Looking toward the future: building a framework to outlast the inception of these U24 networks

Seeding this new field is just the very beginning. Conferences, summer schools, and pilot grants formally establish the first few groups that will give this new field longevity. Once U24 pilot projects are completed, and novel/innovative grant applications are submitted from newly formed research groups, the networks will continue to work with NCCIH and NINDS leadership to further support these projects and new avenues of research. To this end NICCH/NINDS leadership and other NIH stakeholders in mechanisms of force-based manipulations are planning a Special Emphasis Panels to review these grant applications. Further, because by their nature the clinical syndromes for which FBMs are used are complicated, exhibit extensive variability in presentation and patient response to treatment, and engage multiple physiological systems, among other complexities, meaningful clinical translation will require very complicated, often expensive and labor intensive, study designs. By no means is this unique to other translational investigations, but for a budding research field, this adds an additional barrier to effective progress and advancement. As such, additional expertise will be required in statistics, data management, development of data repositories (clinical, imaging, other), and even novel technologies.

The last year has also brought about great changes in joint management of networks. Pilot funding timing will be harmonized to assure that the best grants, regardless of the network targeted, will be funded accordingly. Discussion has been initiated regarding joint workshops and training opportunities that optimizes the talents of all the U24 networks. Key network members have been involved in each others’ U24 training initiatives and network members have begun working together on different grant submissions. Although the U24 goals are distinct, the objective of NIH in building a network of researchers with a variety of backgrounds is working organically.

Conclusion

The networks exist to address the notable gap in force-based mechanisms research. A true test of the U24 networks will be their sustainability and mobility, as demands change and as gaps are addressed. Although all three networks have a mechanism-based focus, they will need to pivot to translational research as force-based mechanisms research matures. Deliverables will need to reflect the needs of clinicians and patients, as well as mechanisms-research constituents. Furthermore, due to the inherently complex nature of the clinical syndromes treated with FBMs, which involve extensive variability in presentation, patient response to treatment, and the interaction of multiple physiological systems, among other intricate and complex factors, achieving meaningful clinical translation will necessitate complicated study designs, involving high costs and significant labor-intensive efforts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Victoria E. Abraira

Victoria E. Abraira, with her undergraduate degree from the University of Southern California and a graduate degree in Neuroscience from Harvard University, established a foundation for her research during her postdoctoral fellowship at Johns Hopkins/Harvard Medical School. There, she delved into the complexities of touch perception, focusing on sensory neurons in mouse hairy skin and the neural codes in the spinal cord and higher brain centers. Now at Rutgers University, she leads a research group dedicated to advancing the understanding of touch and its integration with pain and proprioception. Her work, employing molecular genetics and neurophysiological techniques, has significant implications for understanding sensory disorders and enhancing sensory information processing in the central nervous system.

Victor H. Barocas

Victor H. Barocas received his bachelors and masters degrees at MIT and his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, all in Chemical Engineering. He has been on the faculty of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Minnesota since 2001, and his research involves the interaction between soft tissue mechanics and function across scales. He has particular interest in structural effects, growth and remodeling, and damage.

Beth A. Winkelstein

Beth A. Winkelstein, PhD is the Eduardo D. Glandt President’s Distinguished Professor in Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, where she also has an appointment in the Department of Neurosurgery. Her research focuses on defining mechanisms of mechanotransduction in pain, with the goal of improving clinical care and outcomes via developing diagnostic and intervention approaches.

Chad E. Cook

Chad E. Cook, PT, PhD, MBA, FAPTA is a professor at Duke University, where his primary appointment is in the Department of Orthopaedics; he has secondary appointments in the Department of Population Health Sciences and the Duke Clinical Research Institute. He is part of over 11 million dollars in external funding and is a prolific researcher with over 360 publications.

References

- Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Evidence-based approach to the medical literature. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(2):S5–14. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.12.s2.1.x

- Fell DW, Burnham JF, Dockery JM. Determining where physical therapists get information to support clinical practice decisions. Health Info Libr J. 2013;30(1):35–48. doi: 10.1111/hir.12010

- Wiggins D, Downie A, Engel R, et al. Factors that influence scope of practice of the chiropractic profession in Australia: a scoping review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30:19. doi:10.1186/s12998-022-00428-2

- Peterson S, Weible K, Halpert B, et al. Continuing Education Courses for Orthopedic and sports physical therapists in the United States often lack supporting evidence: a review of available intervention Courses. Phys Ther. 2022;102(6). doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzac031

- Podichetty VK, Booher J, Whitfield M, et al. Assessment of internet use and effects among healthcare professionals: a cross sectional survey. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(966):274–279.

- Which medical publications do doctors read most? The Script https://www.zocdoc.com/resources/which-medical-publications-do-doctors-read-most/(2017).

- Cook CE, O’Connell NE, Hall T, et al. Benefits and threats to using social media for presenting and implementing evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(1):3–7.

- Abdul Rashid A, Kamarulzaman A, Sulong S, et al. The role of social media in primary care. Malays Fam Phys. 2021;16(2):14–18. doi: 10.51866/rv1048

- Kjærulff EM, Andersen TH, Kingod N, et al. When people with chronic conditions turn to peers on social media to obtain and share information: systematic review of the implications for relationships with health care professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e41156. doi:10.2196/41156

- Cook CE, Bonnet F, Maragano N, et al. What is the believability of evidence that is read or heard by physical therapists? Braz J Phys Ther. 2022;26(4):100428.

- Nispel K, Lerchl T, Senner V, et al. Recent advances in coupled MBS and FEM models of the spine—A review. Bioeng. 2023;10:315. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering10030315

- Costi JJ, Ledet EH, O’Connell GD. Spine biomechanical testing methodologies: the controversy of consensus vs scientific evidence. JOR Spine. 2021;4(1):e1138. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1138

- Sadowska J, Gębczyński AK, Konarzewski M, et al. Metabolic risk factors in mice divergently selected for BMR fed high fat and high carb diets. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172892

- Martinac B. 2021 Nobel Prize for mechanosensory transduction. Biophys Rev. 2022;14:15–20. doi:10.1007/s12551-022-00935-9

- Middleton L. Identification of touch neurons underlying dopaminergic pleasurable touch and sexual receptivity. bioRxiv. 2021;2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.09.22.461355

- Bohic M, Abraira VE. Wired for social touch: the sense that binds us to others. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2022;43:207–215. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.10.009