ABSTRACT

As China’s economy has grown, its military capabilities have expanded commensurately, and Beijing has adopted a more assertive foreign policy stance. Perceiving its primacy to be under threat, the response in Washington has been a hard turn towards a Realist paradigm evident across both the military and economic domains. The first contribution of this article is to document that, despite Australia being a staunch US security ally and having its own anxieties about Chinese power, Canberra has undertaken a more modest Realist tilt. This tilt has focused heavily on the military domain, whereas more broadly, an approach informed by the paradigm of Liberalism endures. The second contribution is to theorise this attachment to Liberalism by drawing on Australia’s recent experience of being targeted by Chinese power in the form of geoeconomic coercion. Australia’s interests were not protected by the power of Canberra’s geopolitical friends. Instead, economic interdependencies constrained Beijing’s options, and risks were mitigated by Australian exporters having access to a global trading system underpinned by rules and institutions. Rather than being rooted in ideological and normative appeal, Canberra’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism mostly reflects utilitarian considerations. Australia’s experience likely offers lessons for other lesser powers.

1. Introduction

In a recently published history, historian James Curran tells the story of how Australia has approached Chinese power and managed relations with Beijing in the post-World War Two period, and particularly since diplomatic recognition was struck in 1972.Footnote1 The account is Canberra-centric, delivered from the vantage point of a succession of Australian Prime Ministers while also drawing in the assessments and policy advice proffered to them by ambassadors, advisers and bureaucrats. What is immediately clear is that no single International Relations (IR) paradigm has ever fully framed the way Australian governments have interpreted developments and formulated policy responses.

One paradigm plainly evident is Realism, with its emphasis on an autonomous state and the pursuit of national interest in an anarchic international environment.Footnote2 Indeed, Australian political leaders have long been fond of emphasising their Realist credentials. In 1973, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam wrote in his charter letter to Stephen Fitzgerald, Australia’s first ambassador to Beijing, that Canberra could not afford to convey an ‘impression that we are careless of our own interests’ given that China itself was ruled by ‘hard-headed realists’.Footnote3 In 2009, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd described himself as a ‘brutal realist on China’ during a meeting with US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton.Footnote4 In 2023, Australia’s Foreign Minister, Penny Wong insisted that she had been ‘a realist about China, a realist about foreign policy for some time’.Footnote5 Wong explained that in contemplating relations with China, the current Australian government led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese would ‘start with the reality that China is going to keep being China’, carrying the straightforward implication that Beijing would use ‘every tool at its disposal to maximise its own resilience and influence’.Footnote6

As China’s economy has grown, its military capabilities have expanded commensurately, and Beijing has adopted a more assertive foreign policy stance.Footnote7 In response, there have been discernible changes in Australian government positions that are consistent with Realist preoccupations. North-east Asian politics scholar James Reilly concluded that by the early 2010s Canberra was already following a Realist-inspired ‘classic balancing strategy’.Footnote8 This involved responding to China’s rapidly expanding economy and Australia’s growing exposure to it by strengthening the security alliance with the US, beefing up non-treaty security ties with other regional partners such as Japan, and bolstering its own military capabilities. IR scholars such as Kai He and Huiyun Feng discern that more recent Australian governments have continued to pursue a range of internal, external and ideological balancing endeavours, such as increasing defence spending to ‘a minimum of 2% of GDP’, instigating the AUKUS pact and according ‘values’ a higher profile in declaratory foreign policy.Footnote9 In the economic realm, some analysts have also detected a shift in Canberra’s statecraft to protect Australia’s prosperity and security away from ‘market-based’ actions towards ‘state-based’ ones.Footnote10 IR scholar Jingdong Yuan argues that, ‘realism (or neorealism) has been the predominant lens through which Australia views the world’.Footnote11

This article, however, cautions against exaggerating the pre-eminence of Realism. Another IR paradigm has, and continues to, prominently inform Canberra’s approach to Chinese power and managing relations with Beijing—that of Liberalism and its emphasis on the state and national interests being the sum of pluralist interests and the potential for rules and institutions to tame international anarchy. While presenting Realism and Liberalism as distinct paradigms, it is recognised that there are competing strands within each and the two are best seen as points on a spectrum.Footnote12 It is also recognised that Realism and Liberalism are not exhaustive and that other paradigms also offer explanatory power for understanding Australia’s approach to Chinese power and managing relations with Beijing.Footnote13 A country’s international assessments and foreign policy practice will inevitably reflect an amalgam of all these perspectives.Footnote14 Nonetheless, there is analytical value in attempting to tease out their relative weights.

The contributions of this article are two-fold. The first is a descriptive one documenting that while Washington has responded to the rise of Chinese power and perceived threats to its primacy by adopting a hard Realist turn evident across military and economic domains, Canberra has undertaken a more modest Realist tilt. This tilt focuses heavily on the military domain, whereas in the economic domain an approach informed by the paradigm of Liberalism endures. The second contribution is to theorise this attachment to Liberalism by drawing on Australia’s recent experience with being targeted by Chinese power in the form of geoeconomic coercion. Trade data show that Australia’s interests were not protected by the power of Canberra’s geopolitical friends. Instead, economic interdependencies constrained Beijing’s options, and risks were mitigated by Australian exporters having access to a global trading system underpinned by rules and institutions. The article concludes that rather than being rooted in ideological and normative appeal, Canberra’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism mostly reflects utilitarian considerations.

2. Washington’s Hard Realist Turn

In its final days, the Trump administration made a pointed decision to declassify and draw attention to its Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific, formulated in 2018. This revealed a hard Realist-inspired objective of maintaining US regional ‘strategic primacy’, or alternatively phrased, ‘diplomatic, economic and military preeminence’.Footnote15 At least rhetorically, the Biden administration has been less overt in its commitment to primacy. Some Australian analysts see indications that Washington now accepts the era of US primacy is over and that the region is multipolar. Defence studies scholar, Peter Dean, contends that US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin’s concept of ‘integrated deterrence’, and specifically the AUKUS agreement, is a ‘reflection of the reality that the US can no longer do conventional deterrence in the Indo-Pacific unilaterally’.Footnote16 Similarly, a recent report by the United States Studies Centre argues that there is a ‘strong consensus between the United States and Australia that a strategy of collective defence is needed to deter Chinese aggression’. This is because ‘the United States cannot balance China’s strategic weight alone’.Footnote17

Others, however, are less convinced. Peter Varghese, a former Secretary of the Australian government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, remarks that if the era of US primacy has passed, then ‘no one has told the Americans. Maintaining global US primacy and denying regional primacy to China remains the bedrock of US strategic thinking’.Footnote18 Varghese identifies Washington’s economic statecraft as the key tell. This is because containing China’s rise ‘is the logical end point of a policy which sets the preservation of primacy as the core objective’. The Biden administration rejects claims it seeks to contain China. In April 2023 Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated that while US policy actions ‘may have economic impacts [on China], they are motivated solely by our concerns about our security and values’.Footnote19 Yet a host of other data points suggest differently. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has stated publicly that the US seeks to work with allies ‘to slow down China’s rate of innovation’: a textbook definition of containment.Footnote20 In September 2022, Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s National Security Adviser, declared the US ‘leadership’ in the wide-ranging fields of ‘computing-related technologies, biotech, and clean tech’ to be a ‘national security imperative’. He added that given the ‘foundational nature’ of such technologies, spurring domestic innovation was an insufficient response. Rather, tools such as export controls needed to be bought to bear with the objective of not just maintaining a relative advantage over China but achieving ‘as large of a lead as possible’.Footnote21

Perhaps most instructive, however, is that such rhetoric has been backed by a broad suite of economic statecraft that is consistent with containment. The Biden administration has maintained the restrictive economic measures imposed by the Trump administration, including a tariff regime that arbitrarily levies an average duty on imports from China of 20%—and then gone further. In May 2024, additional tariffs were imposed on Chinese imports in sectors the administration had designated as being ‘strategic’, such as hiking an existing 25% tariff on Electric Vehicles (EVs) to 100%.Footnote22 In October 2022, an unprecedented package of export controls was unveiled aimed at cutting off China’s access to advanced semi-conductors. The package was enacted despite American companies continuing to capture half of the global industry value-added, the same share they held two decades earlier, and multiples of China’s share of 7%.Footnote23 While US officials described the measures as ‘targeted’, Emily Kilcrease, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, assessed that, ‘We [the U.S.] said there are key tech areas that China should not advance in. And those happen to be the areas that will power future economic growth and development’. Gregory Allan, a program director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), added that, ‘The new policy embedded in Oct. 7 [export controls package] is: Not only are we not going to allow China to progress any further technology, we are going to actively reverse their current state of the art’.Footnote24 Jon Bateman, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, evaluated that the controls were ‘effectively a form of economic containment’ because they targeted China’s access to dual-use technologies that were overwhelmingly used for legitimate civilian applications.Footnote25 Alan Estevez, the Under Secretary of Commerce with responsibility for the export controls package, remarked that the new rules did not ‘impede their [China’s] ability to make lower legacy level semiconductors … things for washing machines and the like’.Footnote26 In other words, the US was comfortable with China remaining in global manufacturing value chains, but only at the lower end: again, a textbook definition of containment.

Moreover, there are firm grounds to expect that US controls around technology will continue to expand. When asked whether technologies other than semi-conductors might be restricted, Secretary Estevez responded, ‘I meet with my staff once a week and say, “Okay, what’s next?…So will we end up doing something in those areas?” If I was a betting person, I would put down money on that’.Footnote27 The Biden administration’s policy moves have already gone beyond export controls on advanced semiconductors. There has, for example, been a dramatic ramping up in adding Chinese companies to the Department of Commerce’s Entity List, from 130 in 2018 to more than 800 in 2024.Footnote28 In August 2023, an outbound investment screening mechanism was also unveiled with China as the clear target.Footnote29

These moves were not made at the urging of US allies. A month after the export controls package on semi-conductors was promulgated, former Prime Minister and current Australian ambassador to Washington, Kevin Rudd observed that, ‘The [Biden] administration worked on this for six to 12 months trying to get the allies on board, which didn’t work entirely well because none of them did’.Footnote30 It required a further period of pressure to bring allies such as Japan, Korea and the Netherlands at least roughly into line.Footnote31 Even in aspects where US allies have led on policy moves, Washington has subsequently gone further. For example, Australia was the first country to ban Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei and ZTE, from participating in its 5 G telecommunications network rollout. Numerous other countries followed, including the US However, Washington then cited a national security justification to bar these companies from all sales in the US, including phones, home Wi-Fi routers and even cameras.Footnote32

Ratcheting US policy in one direction is a bipartisan ‘tough on China’ political consensus. In January 2023, a US House of Representatives that was finely balanced between Republicans and Democrats nonetheless voted overwhelmingly (365 for − 65 against) in favour of establishing a Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party. At its first public hearing, the Committee’s chairman, Representative Mike Gallagher, declared that its purpose was ‘to win this new Cold War with Communist China’.Footnote33 He elaborated that, ‘This is an existential struggle over what life will look like in the 21st century, and the most fundamental freedoms are at stake’.Footnote34 In September 2023, Gallagher stated that the long-term goal of US policy with respect to strategic competition with China should be ‘to seek to maintain our primacy’,Footnote35 while in April 2024, along with former Trump national security adviser Matt Pottinger, he argued that rather than simply ‘managing competition’, US policy ‘should not fear’ a goal of a ‘China that is able to chart its own course free from communist dictatorship’. In other words, one that involves regime change.Footnote36

What Washington sees as a threat to its national security has increasingly become all-encompassing. In August 2020, the Trump administration demanded that imports from Hong Kong come with a physical label stating that they were ‘Made in China’. This decision was in response to the imposition of a national security law in Hong Kong that, according to Washington, meant it was ‘no longer sufficiently autonomous to justify differential treatment in relation to China’.Footnote37 The move was despite Hong Kong being a Separate Customs Territory, and consequently, a World Trade Organization (WTO) member in its own right. When Hong Kong sought remedial action, the US defended its decision on the basis that imports with a label specifying that they were ‘Made in Hong Kong’ would be a threat to its ‘national security interests’. While WTO rules do provide a national security exception, they require ‘an emergency in international relations’ for the exception to apply. After a WTO panel found that this bar had not been reached, the response of the Biden administration was to declare that ‘the WTO has no authority to second-guess the ability of a WTO Member to respond to what it considers a threat to its security’ and that it had no intention of coming into compliance.Footnote38

Another notable element of Washington’s stated calculus is a dismissal of opportunity costs. Secretary Estevez has insisted that ‘we [the Biden administration] do not balance trade with national security. When I see an action that needs to be taken for national security, I have top-down coverage to go take care of that regardless of the impact’.Footnote39 Secretary Yellen repeated the position more recently: ‘We will not compromise on these [national security] concerns, even when they force trade-offs with our economic interests’.Footnote40

Rather than, as some have claimed, initiatives like AUKUS serving as evidence that Washington accepts that US regional primacy has ended, there is another interpretation: AUKUS is viewed as part of the strategy for maintaining it. While Australian political leaders and officials were responsible for instigating AUKUS, an Australian journalist with high-level US contacts described the proposal as having been ‘greeted rapturously in Washington’.Footnote41 This was because the agreement would see additional Australian resources being poured into developing military capabilities that would then be available to supplement US assets and support its warfighting objectives in the event of hostilities with China. As Rory Medcalf, the Director of the Australian National University’s National Security College, explained, ‘US forces and their allies will stand a far greater chance of finding Chinese submarines, hemmed into the South China Sea, than China will of finding America’s in the vast Pacific’.

In 2022, former Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull recounted comments from a senior US official justifying AUKUS as ‘getting the Australians off the fence. We have them locked in now for the next forty years’.Footnote42 The comments were widely attributed to Kurt Campbell, President Biden’s ‘Asia Tsar’ and now Deputy Secretary of State.Footnote43 In similar vein, Jonathan Caverley, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College, assesses that, given Canberra’s limited bargaining power vis-à-vis Washington, the decision to acquire nuclear-powered submarines from the US means it ‘will either be on its own or locked into the distinctive American approach to the Indo-Pacific region and the Sino-American competition’.Footnote44 Veteran Singaporean diplomat and frequent Beijing critic, Bilahari Kausikan emphasises that the Biden administration consults allies ‘not merely for the pleasure of their company’ but rather ‘to ascertain what they are prepared to do to meet the United States’ concerns’. Kausikan then nominates Australia and the UK as two countries that ‘meet U.S. expectations’ and views AUKUS as flowing from that.Footnote45 While Australia’s Defence Minister, Richard Marles insists that Canberra has not given Washington a commitment to make any nuclear-powered submarines it acquires available if, for example, there was a conflict in the Taiwan Strait,Footnote46 strategic studies scholar Hugh White respondsFootnote47

… the AUKUS program itself embodies Australia’s acceptance of America’s expectations. The US decision to give us access to its most sensitive military technologies, and especially to sell us Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines taken from the US Navy, is simply unthinkable unless it is sure that Australian forces would be fully committed to the fight …

In June 2023, Secretary Campbell did little to disabuse the notion, contending that any nuclear-powered submarines sold to Australia from US inventory will not be ‘lost’ because ‘they will be deployed by the closest possible allied force’.Footnote48 In April 2024, rather than demurring, he linked submarines provided to Australia under AUKUS to a possible Taiwan Strait contingency.Footnote49

3. Canberra’s Modest Realist Tilt

Against the backdrop of a hard Realist turn in Washington, Canberra’s response to Chinese power presents as a more modest tilt. It accepts a need for Realist-inspired power balancing. This is distinct, however, from actively supporting the preservation of US primacy, including via China’s containment. In April 2023, Minister Wong expounded that if Australia’s interests in a region ‘operating by rules, standards and laws’ were to be realised, this would require the formation of a new ‘strategic equilibrium’ and a recognition that this equilibrium ‘must be underwritten by military capability’. A new ‘strategic equilibrium’ was needed because Canberra now assesses the US to no longer be the region’s unipolar leader. While the US remained an ‘indispensable power’, this was not because it continued to enjoy primacy, but rather because it was ‘central to balancing a multipolar region’.Footnote50 Shortly afterwards, the Australian government published an unclassified version of a Defence Strategic Review it had commissioned that also stated the US was ‘no longer the unipolar leader’ of the region.Footnote51

Canberra’s Realist tilt has not, however, extended to endorsing or supporting China’s containment. An eschewing of containment was evident even amid a sharp downturn in political relations between Beijing and the previous Australian government. In 2019, Prime Minister Morrison went as far as poking fun at the notion of limiting China’s economic ascendencyFootnote52

Why would we want to contain China’s growth? That would be a bit of a numpty thing to do. I thought that was the point of engaging with China, that they would get to a level of maturity in the economy, where they’d bring hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.

The following year while on a visit to Tokyo, Morrison put deliberate distance between Australia’s position on China’s rise and that of the US.Footnote53

Both Japan and Australia agree and always have, that the economic success of China is a good thing for Australia and Japan. Now not all countries have that view, and some countries are in strategic competition with China. Australia is not one of those …

In March 2023, when Australia’s then-ambassador to Washington, Arthur Sinodinos, was asked how ‘an increasingly assertive China’ should be dealt with, his response was to state, ‘Look, I think the first thing to say is that I start from a proposition that a strong and prosperous China is in everybody’s interest’.Footnote54

Of course, unlike other regional US allies like Japan and Korea, Australia is not a globally significant producer of high-tech products. Accordingly, Canberra has not faced the same degree of pressure as Tokyo and Seoul to match Washington’s more recent geoeconomic moves. Nonetheless, there exist several data points suggesting that Canberra would not readily acquiesce.

First, Australian government ministers of both political persuasions have explicitly criticised the approach that Washington has taken. In 2018, Trade Minister Simon Birmingham was asked where Canberra stood in the trade war that the Trump administration had launched earlier that year against China. He responded, ‘[W]e’ve been very clear in our position all along that we do not approve or support the US actions of increasing tariffs in a unilateral way on Chinese goods’.Footnote55 While the Australian government has expressed some sympathy with US complaints about China’s economic practices and the shortcomings of rules governing global trade, after ongoing obstruction by Washington had driven the WTO’s appellate body into dysfunction in December 2019, Birmingham stated that, ‘The eroding of the dispute settlement function of the WTO undermines the effectiveness of the trading rules that we and many other nations rely upon and takes us closer to a “might is right” system without agreed enforceable rules’.Footnote56 The following month, Australia announced it was joining a makeshift appeals body—the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arrangement (MPIA)—set up with the leadership of the European Union, along with around two dozen other WTO members, including China but not the US, that would continue to make WTO rulings enforceable.Footnote57 In 2022, Trade Minister Don Farrell described the Biden administration’s package of export controls cutting off China’s access to advanced semiconductors as ‘draconian’.Footnote58

Second, while Australian government ministers and officials have increasingly emphasised the risks of overreliance on a single supplier or customer, they have also overwhelmingly shunned calls to take a more restrictive approach to economic exchanges. In May 2020, at the outset of Beijing’s campaign of trade disruption targeting Australia, Prime Minister Morrison stated that commercial interactions with China involve ‘a judgement Australian businesses can only make … those are not decisions that governments make for businesses’.Footnote59 In a speech the following year that homed in on the interplay between geopolitics and economics, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg nonetheless acknowledged that many Australian businesses had ‘worked hard to access the lucrative Chinese market’. This, he said, had ‘brought great benefits to them and to Australia overall. And they should continue to pursue these opportunities where they can’.Footnote60 In March 2022, even after several months of fanning a narrative that China was a strategic and security threat in the lead-up to a federal election, Prime Minister Morrison continued to back this position: ‘The ongoing engagement between private industry and business with markets like China is very important and I will continue to encourage that, but obviously the political and diplomatic situation is very, very different … ’.Footnote61 The current Australian government has continued the approach. In September 2022, Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs, Tim Watts told members of the Australia–China Business Council that their commercial ties with China were seen by Canberra as ‘complementary’ to their efforts to stabilise the broader relationship. He encouraged those in the audience to ‘stay engaged in the China market, while accounting for risk’.Footnote62 In February 2023, Prime Minister Albanese himself declared that ‘it quite clearly was in Australia’s interests to export more to China’,Footnote63 while in April, Minister Farrell clarified that Canberra’s idea of trade diversification was of the China-and variety, not China-or: ‘We have made it very clear that our policy is trade diversification. So that means getting back into China, but also opening up with India, the United Kingdom, with the European Union’.Footnote64

Some scholars identify that Canberra’s economic statecraft is increasingly embracing ‘state-based’ actions.Footnote65 Many of these actions, however, take the form of offering positive inducements to private sector actors as part of an economic resilience agenda. This is distinct from a reassertion of state authority to restrict economic exchanges with China in support of its containment. The most dramatic restrictive step taken by Canberra has been to bar Chinese participation in Australia’s 5G telecommunications network rollout. Chinese companies providing surveillance and data storage hardware, as well as mobile applications, have also had their ability to service government buyers and users curtailed.Footnote66 Nonetheless, access to the much larger private market remains intact. Chinese investment proposals have also been blocked with increasing frequency.Footnote67 Still, since 2016, the aggregate number of refusals on the public record stands at just seven, while in recent years the average number of approvals extended annually to Chinese investors is around 200–300.Footnote68With just one minor exception, Canberra has also not forced Chinese companies to relinquish their existing asset holdings, despite intense lobbying efforts aimed at achieving that outcome in certain cases.Footnote69

Aside from the limitations of Canberra’s Realist tilt, there are compelling indicators that in approaching Chinese power there remains an ongoing attachment to the paradigm of Liberalism. Canberra continues to regard a more prosperous Chinese economy and deeper regional economic integration as delivering benefits for both prosperity and security. Despite professing to be ‘a realist about foreign policy’, when delivering an address in London in January 2023 Minister Wong contendedFootnote70

Of course, Australia has its own benefits to gain from economic engagement in the region. But we also see two broader imperatives for economic engagement. Advancing prosperity for all is in itself a good thing … it is [also] an investment in our own security. Stability and prosperity are mutually reinforcing.

Two months later while visiting Beijing, Minister Farrell delivered a particularly ebullient version of Minister Wong’s sentiment: ‘Nothing’s going to do more to achieve peace in our region than strong trading relationships between Australia and China’.Footnote71 In December 2022, the ‘mutually reinforcing’ interplay between prosperity and stability had led Minister Wong to tell a Washington audience that ‘our national interest lies in being at every table where economic integration in Asia is being discussed’, pointing to Canberra’s active support and participation in the WTO, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) as evidence that this was not mere rhetoric.Footnote72 To be sure, Canberra’s enthusiasm for rules and multilateral arrangements and integrating China into them has not been without limits. It has not, for example, expressed the same full-throated support as Singapore, Malaysia and New Zealand for China’s entry into the CPTPP.

4. Theorising Canberra’s Attachment to Liberalism

Like most countries not able to protect their interests through power alone, the Australian government has long had an instinctive attraction to an international system where the exercise of power is constrained by international rules overseen by multilateral institutions.Footnote73 Yet in the face of growing Chinese power, this has been challenged by domestic policy advocacy that centres an analysis of relations with Beijing on the reality of that power and puts little store in the ability of economic interdependencies and international rules and institutions to restrain it.Footnote74 Moreover, while the notion in Liberalism of ‘complex interdependence’ raises the mediating potential of economic interdependencies led by non-state actors on Realist prognoses, it also acknowledges that if these interdependencies are asymmetric, then one country may well acquire power over another.Footnote75

That economic engagement with China is not an unalloyed opportunity has been a feature of Australia’s public discourse since at least 2007, when China overtook Japan to become the country’s largest trading partner. In 2013, a Sydney-based foreign policy think-tank commissioned an academic assessment of the risk ‘that the Chinese government will manipulate its trade and investment to undermine Australian autonomy or security’.Footnote76 This concluded that the risks were ‘overblown’, but they persisted, nonetheless. In 2016, Peter Jennings, the Executive Director of a Canberra-based strategic policy think-tank contended, ‘We’ve never had a greater dependency with any country … The risk that creates for us is if Beijing wants to adopt politically coercive policies, it’s in a fairly strong position to do so with us because of that level of trade dependence’.Footnote77 (Barrett & Wong, 2016). In 2020, Jennings reiterated that ‘economic dependence on China is dangerous and steps must be taken to reduce that dependence’,Footnote78 while more recently his tone has become even more strident: ‘The government should be advancing every possible measure to reduce economic dependence on China’.Footnote79

Such commentators identify an asymmetry in Australia–China trade at an aggregate level. While China accounts for more than 30% of Australia’s exports and around 20% of its imports, Australia only accounts for 2% and 5% of China’s goods exports and imports, respectively.Footnote80 However, assuming that this asymmetry grants Beijing leverage is to miss one of the IR scholars, Robert Keohane and Josphe Nye’s original insights, namely that an asymmetry in exposure only affords the possibility of exerting power: it is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Whether that power exists is contingent on the dimensions of interdependence, ‘sensitivity’ and ‘vulnerability’. The former refers to the speed and scale of costs incurred in one country in response to changes by another but with no changes in the overall framework. Vulnerability allows for the possibility that the framework can also be changed to mitigate costs. This, in turn, rests on the availability and costliness of the alternatives that the two countries face.

A key lesson from recent years, as Beijing has targeted Australia with power in the form of geoeconomic coercion, is that sensitivity and vulnerability are modest. For starters, Beijing has been constrained to exerting power through trade because Australia’s reliance on China as a source of foreign investment has always been marginal. Further, while Beijing’s actions saw the value of Australia’s goods exports to China fall by a not insignificant $A20 billion, the total value of Australia’s goods exports to China immediately prior to the disruption in 2020 was $A150 billion, and in 2023, the total value of Australia’s goods exports to China was 38% higher than in 2020. The main reason for this outcome was that, along with a fortuitous increase in global commodity prices, Beijing proved unwilling to disrupt most of Australia’s big-ticket trade items because for many Chinese businesses and households Australia was a critical supplier. This included iron ore, liquefied natural gas (LNG), lithium, wool, wheat and more. Beijing further proved unwilling to disrupt Australia’s supply chains, perhaps reflecting an unwillingness to crimp sales by domestic firms and/or reflecting that a previous attempt to do so involving Japan had backfired and hurt Chinese interests.Footnote81 Moreover, for Australia’s prosperity $A20 billion of disrupted exports to China is marginal compared with domestic sources of demand, such as household consumption, which stood at around $A1 trillion.Footnote82

The framework in which Beijing directed power against Australia was also adjusted almost immediately, further mitigating costs. The Australian economy benefits from ‘automatic stabilisers’, such as a flexible exchange rate. When hit with a negative external shock, whether in the form of geoeconomic coercion or otherwise, the value of the Australian dollar falls instantaneously, providing an across-the-board boost to the competitiveness of Australia’s exports on international markets. Macroeconomic tools, such as fiscal and monetary policy, provide the government and central bank with further means to offset adverse shocks. Many of Australia’s highest-value exports are also traded in competitive global markets. When Beijing forced Chinese importers to source supply from elsewhere, this meant these markets simply re-directed the Australian product to those customers that China’s new suppliers previously serviced. Market re-direction explains why a fall in the aggregate value of disrupted goods exports to China beginning in 2020 was mirrored by an equivalent increase in their value to the rest of the world.Footnote83 Australian exporters were able to find other markets because they were open thanks to the multilateral trading system. Neither exporters nor the Australian government knew exactly where those markets would be ahead of time, and in the subsequent accounting, they included the markets of Canberra’s geopolitical friends and foes alike. Geopolitical alignment between capitals also had no relevance for determining which countries’ companies would take commercial advantage of Australian exporters’ misfortune in losing access to the Chinese market. Trade data show that US companies snapped up the largest proportion of lost Australian export value to China, while those from Canada and New Zealand were also in the top five. Nor did Canberra’s geopolitical friends increase their own purchases. In aggregate, US purchases of Australian goods disrupted by Beijing fell. All this reflects an economic reality that in the world of international commerce Australia’s closest geopolitical friends are oftentimes its fiercest competitors, and businesses and consumers principally make purchases based on price and quality considerations, not the geopolitical leanings of their capitals. Finally, Australian exporters were also able to mitigate costs through ‘deflection’ and ‘transformation’.Footnote84 Market re-direction offered Australian rock lobster exporters little respite because prior to Beijing cutting off market access, China accounted for 90% of rock lobster imports globally.Footnote85 More useful was the ‘deflection’ evident in a jump in demand from Vietnam, Hong Kong and Taiwan, with the Australian product then being smuggled to the Chinese mainland.Footnote86 For timber exporters, meanwhile, ‘transformation’ offered some relief. After Beijing barred the importation of timber logs, some Australian exporters circumvented the restriction by processing their logs into wood chips, which continued to be able to pass freely through Chinese customs.

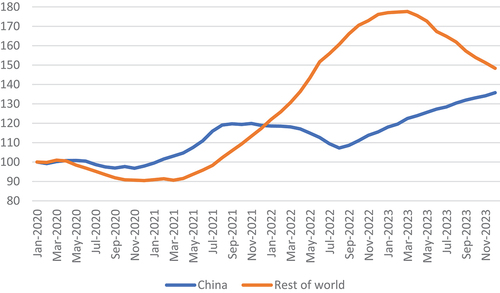

Australia’s lack of ‘sensitivity’ and ‘vulnerability’ to Beijing’s power is summarised in .Footnote87 Benchmarked against January 2020, the largest percentage fall in the annual value of Australia’s goods exports to China was just 3%. This compared with 9% for the rest of the world. In December 2023, the index for exports to China and the rest of the world increased by 36% and 48%, respectively.

Recent events have demonstrated the worth of international rules and institutions not simply for diffusing Chinese power by keeping global markets open and competitive, but also in providing a neutral forum in which Canberra and Beijing can engage to resolve their bilateral disputes. When Canberra instigated cases at the WTO seeking the removal of Chinese tariffs on Australian barley and wine, Beijing agreed to submit to the MPIA arrangement that both countries had voluntarily joined in 2020. This meant that neither side could appeal ‘into the void’ if the WTO adjudication panel returned an adverse finding. Canberra agreed to submit to the same process in a dispute case brought by Beijing.Footnote88 The WTO panel’s final report on the barley dispute was issued to both parties in March 2023, reportedly with an adverse finding against Beijing. The following month it was announced that the two sides had struck a deal whereby Canberra agreed to ‘suspend’ its WTO action in return for Beijing committing to undertake an ‘expedited review’ of the tariffs. This saw them removed in August. Between October 2023 and March 2024, the same process and outcome unfolded in the case of wine. At the same time, when Australia lost a WTO case involving anti-dumping tariffs that had been levied on a number of Chinese steel products, Canberra announced that it ‘accept[ed] the ruling’ and would return to compliance.Footnote89 This ongoing commitment to WTO rules and processes by Australia and China is distinct from the interplay between China and the US in their trade disputes. In November 2019, China won a WTO case against the US that was brought prior to President Trump launching a trade war. Several other wins for China followed. Washington responded to each by rejecting the rulings, and then denying Beijing access to legal recourse by appealing ‘into the void’. In September 2021, the US won a case against China, and Beijing responded in kind.Footnote90

Another part of Australia’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism likely involves a recognition of foreseeable risks from joining Washington’s hard Realist turn. First, Varghese seems correct in arguing that pursuing China’s containment would ‘render impossible the construction of guard rails for the [U.S.-China] relationship’, and as such, be a ‘recipe for geostrategic instability’.Footnote91 Second, it runs a high probability of failing. Per-capita incomes in China are currently less than one-third of those in the US Whatever hobbling measures Washington might impose, these would not preclude Beijing from implementing domestic reforms that could see per-capita incomes approach half that of US levels. Differences in population size then mean that Beijing would have vastly more economic heft than Washington that could be turned towards advancing its geopolitical objectives. Controls on exports and technology are also rarely watertight. For example, aside from smuggling operations, Chinese entities needing access to advanced semi-conductors for Artificial Intelligence applications have already turned to cloud providers able to supply the capability.Footnote92 Controls further incentivise the precise outcome they seek to limit. In prioritising immediate gains, Paul Scharre of the Center for a New American Security observes that the controls will predictably accelerate China’s drive towards semi-conductor independence. Beijing has long sorted to promote greater indigenous semi-conductor capabilities, but Chinese manufacturers needing semi-conductors had little incentive to purchase local options when higher quality, lower cost ones featuring US technology were readily available. The export controls package changes this. A better approach, Scharre argues, would be to ‘keep China dependent on U.S. technology’.Footnote93 Finally, rather than positioning Australia as a good faith regional actor committed to supporting a multipolar region in which international rules and institutions protect the interests of lesser powers, following Washington’s lead would mark Australia as a hypocritical outlier. There is little appetite in a region that prizes economic development and stability for a hardening geopolitical block dedicated to preserving US primacy by knee-capping the leading resident power.

5. Conclusion

This article reflected on the extent to which two IR paradigms, Realism and Liberalism, have informed Canberra’s approach to Chinese power and managing relations with Beijing. While the former has grown in prominence as Chinese power has grown and Beijing’s foreign policy behaviour has become more assertive, an ongoing attachment to Liberalism endures, particularly relative to Washington and beyond the military domain. Helping to explain Canberra’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism is Australia’s recent experience of being targeted by Chinese power in the form of geoeconomic coercion. Blunting Chinese power was not the power of Canberra’s geopolitical friends, but rather the key tenets of Liberalism: economic interdependencies that constrained Beijing’s options, and the risk mitigation afforded by Australian exporters having access to open and competitive global markets underpinned by international rules and institutions. Thus, rather than being rooted in ideological and normative appeal, Canberra’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism mostly reflects utilitarian considerations.

Other lesser powers might also draw lessons from Australia’s experience. Australia was unusually fortunate in that for many big-ticket items of trade, Chinese importers had few other supplier options. However, even when China did have ready access to alternative suppliers, Australia’s experience demonstrates that the risk this presents is limited so long as exporters also have access to alternative markets. This makes the point that the current Liberalism-infused multilateral trading system already diffuses the whims of great powers, even in the absence of a ‘collective economic security measure’ between the US and its allies of the type that is frequently called for but never delivered.Footnote94 It is also the case that Australia’s experience is far from the first that highlights Beijing’s lack of success in leveraging economic connections for geopolitical ends.Footnote95 None of this is to claim that economic statecraft in the form of ‘state-based’ actions has no utility in specific areas where Beijing has unusual and asymmetric leverage. Still, there remains a distinction between pursuing a resilience agenda that offers positive inducements to private sector actors to engage with alternative partners and one that restricts economic exchanges with China, including in support of its containment.

With the US–China strategic competition seemingly baked in, Canberra’s ongoing attachment to Liberalism will expectedly be increasingly challenged by Washington’s hard Realist turn and the pressure it places on allies to follow suit. For Australia and other lesser powers, however, there are sound reasons to assess that succumbing to this pressure would result in reduced prosperity, increased geopolitical instability and their own regional marginalisation.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Mark Beeson, Chengxin Pan, Corey Lee Bell, David Goodman, Darren Lim, Sam Zhao and participants in a workshop, ‘One Troubled Relationship, Many IR theories: Understanding Australia-China Relations and Beyond’, hosted by The Center for Governance and Public Policy (CGPP) at Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, on 17 July 2023, for helpful comments received on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 James Curran, Australia’s China Odyssey: From euphoria to fear (Sydney: NewSouth, 2022).

2 Stephen Kirschner, An Unwritten Future: Realism and Uncertainty in World Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

3 Stephen Fitzgerald, ‘Managing Australian foreign policy in a Chinese world’, The Conversation, March 16, 2017.

4 ‘US embassy cables: Hillary Clinton ponders US relationship with its Chinese ‘banker’, The Guardian, December 5, 2010.

5 Andrew Tillett, ‘Why Penny Wong says we can’t “reset” with China’, Australian Financial Review, February 24, 2023.

6 Penny Wong, ‘National Press Club Address: Australian interests in a regional balance of power’, April 17, 2023 (https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/speech/national-press-club-address-australian-interests-regional-balance-power).

7 Peter Robertson, ‘The Real Military Balance: International Comparisons of Defense Spending’, The Review of Income and Wealth 68(3), pp. 797–818.

8 James Reilly, ‘Counting on China? Australia’s strategic response to economic interdependence’, The Chinese Journal of International Politics 5(4), (2012), pp. 369–394

9 Kai He and Huiyun Feng, After hedging: hard choices for the Indo-Pacific states between the US and China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

10 Victor Ferguson, Darren Lim and Benjamin Herscovitch, ‘Between market and state: the evolution of Australia’s economic statecraft’, The Pacific Review 36(3), (2023), pp. 1148–1180.

11 Jingdong Yuan, ‘Australia-US Alliance Since the Pivot: Consolidation and Hedging in Response to China’s Rise’ in Trump’s America and International Relations in the Indo-Pacific eds. A Akaha, J. Yuan and W Liang (Springer, 2023), pp. 77–98.

12 James Richardson, ‘Contending Liberalisms: Past and Present’, European Journal of International Relations 3(1), (1997), pp.5–33. Thomas Walker, ‘A circumspect revival of liberalism: Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye’s Power and Interdependence’ in Classics in International Relations: Essays in Criticism, eds. H. Bliddal, C. Sylvest and P. Wilson (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 148–156. Matthew Specter, The Atlantic Realists (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022). Jonathan Kirshner, An Unwritten Future: Realism and Uncertainty in World Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

13 Kai He and Huiyun Feng, ‘IR theory and Australia’s Policy Change towards China, 2017–2022: An Introductory Essay’, Journal of Contemporary China, (this issue).

14 Brendon O’Connor and Danny Cooper, ‘Ideology and the Foreign Policy of Barack Obama: A Liberal-Realist Approach to International Affairs’, Presidential Studies Quarterly 51(3), pp. 635–666.

15 National Archives, ‘U.S. Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific’, 2018. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IPS-Final-Declass.pdf.

16 Peter Dean, ‘ANZUS Pivot Points: Reappraising “The Alliance” for a new Strategic Age’, University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, 2022. https://defenceuwa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Black-Swan-Strategy-Paper-Issue03_ANZUS-Pivot-Points.pdf.

17 Ashley Townshend, David Santoro and Toby Warden, ‘Collective deterrence and the prospect of major conflict’, United States Studies Centre, 2023. https://www.ussc.edu.au/collective-deterrence-and-the-prospect-of-major-conflict.

18 Peter Varghese, ‘How we can live with a weaker America’, Australian Financial Review, May 17, 2023.

19 Janet Yellen, ‘Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen on the U.S. – China Economic Relationship at John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies’, April 20, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1425

20 Amanda Macias, ‘U.S. needs to work with Europe to slow China’s innovation rate, Raimondo says, CNBC, September 28, 2021.

21 Jake Sullivan, ‘Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Special Competitive Studies Project Global Emerging Technologies Summit’, September 16, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/09/16/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-at-the-special-competitive-studies-project-global-emerging-technologies-summit/.

22 ‘Factsheet: President Biden takes action to protect American workers and business from China’s unfair trade practices’, The White House, May 14, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/05/14/fact-sheet-president-biden-takes-action-to-protect-american-workers-and-businesses-from-chinas-unfair-trade-practices/.

23 ‘2023 State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry’, Semiconductor Industry Association, 2024. https://www.semiconductors.org/2023-state-of-the-u-s-semiconductor-industry/.

24 Alex Palmer, ‘“An Act of War”: Inside America’s Silicon Blockade Against China’, The New York Times Magazine, July 12, 2023.

25 Jon Bateman, ‘Biden is Now All-In on Taking out China’, Foreign Policy, October 12, 2022.

26 Martijn Rasser, ‘A Conversation with Under Secretary of Commerce Alan F. Estevez’, October 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/transcript/a-conversation-with-under-secretary-of-commerce-alan-f-estevez.

27 ibid.

28 ‘Efficiency be damned’, The Economist, January 12, 2023. Alan Estevez, ‘Keynote remarks: BIS Update Conference 2024’, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/about-bis/newsroom/3487–2024-03-27-bis-update-conference-us-estevez-keynote-as-prepared/file.

29 ‘Executive Order on Addressing United States Investments in Certain National Security Technologies and Products in Countries of Concern’, The White House, August 9, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/08/09/executive-order-on-addressing-united-states-investments-in-certain-national-security-technologies-and-products-in-countries-of-concern/.

30 Elena Collinson and Corey Bell, ‘Australia-China Monthly Wrap-up: October 2022’, Australia-China Relations Institute, November 17, 2022, https://www.australiachinarelations.org/content/australia-china-monthly-wrap-october-2022.

31 Demetri Sevasopulo and Kana Inagaki, ‘US tries to enlist allies in assault on China’s chip industry’, Financial Times, November 14, 2022.

32 James Politi, ‘Chinese telecoms groups Huawei and ZTE barred from US sales’, Financial Times, November 26, 2022.

33 Connor O’Brien and Gavin Bade, ‘House establishes tough-on-China select committee’, Politico, October 1, 2023.

34 Charles Hutzler, ‘House Committee Lays Out Case for China Threat’, The Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2023.

35 ‘U.S. Strategic Competition with China’, September 11, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/event/us-strategic-competition-china.

36 Matt Pottinger and Mike Gallagher, ‘America’s Competition With China Must Be Won, Not Managed’, Foreign Affairs, April 10, 2024.

37 Kahon Chan, ‘Hong Kong hits out at US over “Made in China” rule for exports after meeting in Geneva’, South China Morning Post, April 29, 2023.

38 ‘Statement from USTR Spokesperson Adam Hodge’, Office of the United States Trade Representative, December 21, 2022, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2022/december/statement-ustr-spokesperson-adam-hodge-0.

39 Martijn Rasser, ‘A Conversation with Under Secretary of Commerce Alan F. Estevez’, October 27, 2022, https://www.cnas.org/publications/transcript/a-conversation-with-under-secretary-of-commerce-alan-f-estevez.

40 Janet Yellen, ‘Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen on the U.S. – China Economic Relationship at John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies’, April 20, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1425.

41 Peter Hartcher, ‘Why Washington was so ecstatic about Morrison’s AUKUS pact’, The Sydney Morning Herald, September 28, 2021.

42 Malcolm Turnbull, ‘Sleepwalk to War: Correspondence’, Quarterly Essay, 86, 2022, https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/correspondence/malcolm-turnbull.

43 James Curran, ‘Will “getting Australia off the fence” drag us into war in Asia?’, Australian Financial Review, December 11, 2022.

44 Jonathan Caverley, ‘AUKUS: When naval procurement sets grand strategy’, International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 78(3), pp. 327–334.

45 Bilahari Kausikan, ‘Navigating the New Age of Great-Power Competition’, Foreign Affairs, April 11, 2023.

46 ‘Interview with David Speers, ABC, Insiders’, Australia Government Department of Defence, March 19, 2023, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/transcripts/2023-03-19/interview-david-speers-abc-insiders.

47 Hugh White, ‘Penny Wong’s next big fight’, The Monthly, April 2023, https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2023/april/hugh-white/penny-wong-s-next-big-fight:

48 Adam Creighton, ‘US “aspirational” on timing of AUKUS submarines’, The Australian, June 27, 2023.

49 Liu Tze-hsuan, “US’ Kurt Campbell touts AUKUS benefit in Strait’, Taipei Times, April 5, 2024.

50 Penny Wong, ‘National Press Club Address, Australian interests in a regional balance of power’, April 17, 2023, https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/speech/national-press-club-address-australian-interests-regional-balance-power.

51 ‘National Defence: Defence Strategic Review 2023’, Australian Government Department of Defence, April 24, 2023, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

52 Matthew Doran, ‘Scott Morrison says Australia and the world will need to get used to US-China trade war’, ABC News, August 20, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-20/scott-morrison-says-world-should-get-used-to-us-china-trade-war/11430766.:

53 ‘Doorstop Interview—Tokyo, Japan’, Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, November 18, 2020, https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-43136.

54 ‘A Conversation with Arthur Sinodinos, Outgoing Ambassador of Australia to the U.S.’, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2 March 2023, https://www.csis.org/events/conversation-arthur-sinodinos-outgoing-australian-ambassador-united-states.

55 ‘Interview on RN Breakfast with Fran Kelly’, November 6, 2018, https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/simon-birmingham/transcript/interview-rn-breakfast-fran-kelly-1.

56 Eryk Bagshaw and Matthew Knott, ‘Australia hits out at dismantling of WTO appeals’, The Sydney Morning Herald, December 17, 2019.

57 Andrew Tillett, ‘Australia moves to end logjam over trade disputes’, Australian Financial Review, January 24, 2020.

58 Sarah Ison, ‘Don Farrell’s pitch for fair trading’, The Australian, November 14, 2022.

59 ‘Q&A, National Press Club’, Australia Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, May 26, 2020, https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-42824.

60 Josh Frydenberg, ‘Building Resilience and the Return of Strategic Competition, Melbourne’, 6 September 2021, https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/josh-frydenberg-2018/speeches/building-resilience-and-return-strategic-competition

61 ‘Q&A, Chamber of Commerce and Industry WA’, Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, March 16, 2022, https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-43862.

62 Tim Watts, ‘ACBC Networking Day Gala Dinner’, September 13, 2022, https://ministers.dfat.gov.au/minister/tim-watts/speech/acbc-networking-day-gala-dinner.

63 ‘Press conference—Mocca Childcare Centre, Canberra’, February 9, 2023, https://www.pm.gov.au/media/press-conference-mocca-childcare-centre-canberra.

64 ‘Sky News with Tom Connell’, April 4, 2023, https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/transcript/sky-news-tom-connell-0.

65 Victor Ferguson, Darren Lim and.

66 Ausma Bernot and Marcus Smith, ‘Understanding the risks of China-made CCTV surveillance cameras in Australia’, Australian Journal of International Affairs 77(4), pp. 380–398.

67 James Laurenceson, ‘Australia’s Narrative on Beijing’s Economic Coercion: Context and Critique’ in Different Histories, Shared Futures: Dialogues on Australia-China, eds. M. Gao, J. O’Conner, B. Xie and J. Butcher (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), pp. 65–87.

68 Australian Government—The Treasury, ‘Quarterly Report on Foreign investment − 1 July 2023 to 30 September 2023’, February 8, 2024, https://foreigninvestment.gov.au/news-and-reports/reports-and-publications/quarterly-report-foreign-investment-1-july-30-september-2023.

69 Stephen Dziedzic, ‘Federal government will not cancel Chinese company Landbridge’s Port of Darwin lease’, ABC News, October 20, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-20/port-of-darwin-chinese-company-lease-not-cancelled/103003452.

70 Penny Wong, ‘An enduring partnership in an era of change’, January 31, 2023, https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/speech/enduring-partnership-era-change.:

71 ‘Doorstop Beijing Capital International Airport, China’, May 11, 2023, https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/transcript/doorstop-beijing-capital-international-airport-china.

72 Penny Wong, ‘Speech to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’, December 7, 2022, https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/speech/speech-carnegie-endowment-international-peace.

73 Allan Gyngell, Fear of abandonment (Melbourne: LaTrobe University Press, 2017).

74 Peter Jennings, ‘USCC Hearing testimony—Peter Jennings’, January 28, 2021, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uscc-hearing-testimony-peter-jennings. Hugh White, ‘Sleepwalk to War: Australia’s Unthinking Alliance with America’, Quarterly Essay 86, (2022).

75 Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977).

76 James Reilly, ‘China’s economic statecraft: turning wealth into power’, Lowy Institute, November 26, 2013, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/china-s-economic-statecraft-turning-wealth-power.

77 Jonathan Barrett and Sue-Lin Wong, ‘China’s warns “protectionist” Australia on investment after grid deal blocked’, Reuters, August 17, 2016.

78 Peter Jennings, ‘National security strategy can help us build key alliances to counter China’, The Australian, May 2, 2020.

79 Peter Jennings, ‘Show some steel on China’s investment in our critical assets’, The Australian, February 23, 2023.

80 ‘China’, Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/chin-cef.pdf.

81 Shiro Armstrong and Tom Westland, ‘The lessons of the economic war on Russia’, East Asia Forum, March 20, 2022.

82 James Laurenceson, ‘Assessing the risks from Australia’s economic exposure to China’, Agenda—a Journal of Policy Analysis and Reform 28(1), (2021), pp. 3–26.

83 James Laurenceson and Shiro Armstrong, ‘Learning the right policy lessons from Beijing’s campaign of trade disruption against Australia’, Australian Journal of International Affairs 77(3), (2023), pp. 258–275.

84 Victor Ferguson, Scott Waldron and Darren Lim, ‘Market adjustments to import sanctions: lessons from Chinese restrictions on Australian trade, 2020–21’, Review of International Political Economy 30(4), pp. 1255–1281.

85 ‘Trade Map’, International Trade Center, https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

86 Brad Thompson, ‘WA lobster worth more than $150 m slips through China trade ban’, Australian Financial Review, February 12, 2024.

87 ‘International Trade in Goods’, Australian Bureau of Statistics, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/international-trade-goods/latest-release.

88 James Laurenceson and Weihuan Zhou, ‘Australia-China trade: Opportunity, risk, mitigation, ballast—progress?’ in Engaging China: How Australia can lead the way again, eds. J. Reilly and J. Yuan (Sydney: University of Sydney Press, 2023), pp. 103–130.

89 Don Farrell, ‘WTO Steel Products dispute’, March 27, 2024, https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/statements/wto-steel-products-dispute.

90 Chenxi Wang and Weihuan Zhou, ‘A Political Anatomy of China’s Compliance in WTO Disputes’, Journal of Contemporary China 32, pp. 811–827.

91 Peter Varghese, ‘How we can live with a weaker America’, Australian Financial Review, May 17, 2023.

92 Eleanor Olcott, Qianer Liu and Demetri Sevastapulo, ‘Chinese AI groups use cloud services to evade US chip export controls’, Financial Times, March 9, 2023.

93 Paul Scharre, ‘Decoupling Wastes U.S. Leverage on China’, Foreign Policy, January 13, 2023.

94 Fergus Hanson, Emilia Currey and Tracy Beattie, ‘The Chinese Communist Party’s coercive diplomacy’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, September 1, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinese-communist-partys-coercive-diplomacy.

95 James Reilly, ‘Economic statecraft’, in Handbook of the politics of China, ed. D. Goodman (Edward Elgar, 2015), pp. 381–396.