ABSTRACT

This paper argues against the claim by Chinese government officials and some scholars that China’s carbon emission trading scheme is market-driven. It finds that, in contrast to carbon markets that are characteristic of the marketization model, China’s carbon markets are led by the state, and the market mechanism plays a limited role at best. Consequently, China’s carbon markets are overwhelmingly challenged by a number of factors. These include the low efficiency of resource allocation, questionable market fairness, rent-seeking, and corruption. This paper argues that the state-led mechanism is not conducive to China’s green transition unless a market system is introduced.

1. Introduction

According to the World Bank, China’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reached over 12.7 billion tons in 2019, twice the emissions of the United States and four times those of India.Footnote1 Facing the challenge of carbon-extensive development, the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly stated that efforts should be made to ‘promote a sound economic structure that facilitates green, low-carbon, and circular development’,Footnote2 so as to advance China’s green transition. Accordingly, the National Development and Reform Commission of China (NDRC) announced in 2017 that China would also introduce a carbon emission trading scheme. The stated aims of the trading scheme were to establish a national carbon market ‘featuring clear ownership, full protection, free transfer, effective supervision, and transparency’; and, to ‘effectively stimulate the emission reduction potential of enterprises for control of GHG emissions’.Footnote3

In the six years from the establishment of the national carbon market, from 2017 to 2024, Chinese scholars and government officials offered various assessments regarding whether the trading scheme achieved its goals. For example: Qi Shaozhou posited that the carbon market is a market-based tool, and the development of carbon market in China is conducive to lowering GHG emissions, reducing costs and promoting a green transitionFootnote4; Huang Xianglan et al. believed that China’s carbon markets can effectively reduce carbon emissions and help China fulfill the environmental dividendFootnote5; and, Hu Yucai et al. claimed that carbon emissions have been significantly reduced in carbon market applicable industries.Footnote6 Furthermore, in terms of resource allocation equity, the Interim Regulations on the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading, an official document, explicitly stated that China’s carbon market management follows the principles of openness, fairness and impartialityFootnote7; Li Ronghua and other scholars also held that China’s carbon emissions trading can effectively reduce carbon emissions in pilot areas from perspectives such as efficiency and fairness.Footnote8 When it comes to regulation effects, officials from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) and the Ministry of Justice clearly stated that China’s carbon markets have established a complete, effective regulatory framework in areas such as registration and management of trading institutions, applicable industries and trading regulations, carbon allowance allocation and verification of carbon emission data,Footnote9 injecting considerable vitality into the markets. Based on these assessments, it can be found that the Chinese government and a substantial portion of scholars believe that China’s carbon markets have already achieved the intended goals of realizing efficient emission reduction, a fair allocation mechanism, as well as transparent and orderly regulation.Footnote10 However, the aforementioned claim by Chinese government officials and some scholars is not supported by our observation of China’s environmental governance in practice. As a socialist country where market mechanisms are not well established and social governance is primarily led by state power, is it even possible for China to foster a market-oriented carbon market?

This question will be addressed by presenting an objective observation of China’s environmental governance system. Findings include that China’s environmental governance system is characterized by centralized power, insufficient public participation, and reliance on comprehensive, rapid crisis response. This indicates that China’s approach to environmental governance differs greatly from the market-based governance model prevalent in the West. Based on this finding, this paper characterizes China’s state power-led environmental governance as an ‘administration-led’ model. This is done by first articulating what the model is and demonstrating how it is manifested in various aspects of China’s environmental governance regime beyond carbon markets, with a view to providing a theoretical analytical tool for observing and interpreting China’s environmental governance phenomena. Then, to evaluate the practical effectiveness of the administration-led model, this paper examines China’s carbon markets, which are an important component of environmental governance in China. Contrary to the assertions of official documents and academic research, it finds that China’s carbon markets are not market-oriented. Rather, viewed through the administration-led model, they fail to perform even the most basic functions of a market. In essence, they are merely tools for the exercise of state power that are disguised as ‘markets’. To further elucidate the potential implications of this model on China’s environmental governance, this paper analyzes the consequences faced by China’s carbon markets under the administration-led model. It makes the case that under this model, the goal of constructing China’s carbon market cannot be achieved, which will hinder China’s green transformation.

This paper offers several contributions to this discussion. Firstly, it offers a theoretical paradigm, the administration-led model, which differs from Western equivalents and can be used to interpret China’s environmental governance practices by probing into China’s environmental governance system. Secondly, it identifies the centralized, non-market attributes of China’s state power-led carbon markets by examining the markets’ operational mechanisms. Thirdly, building upon the administration-led model, it further reveals the actual effectiveness of China’s state power-led carbon markets, as well as its influence on China’s green transition.

2. Administration-Led Model: A Theoretical Paradigm of China’s Environmental Governance

This paper’s counter-claims of the aforementioned documents and scholars stems from the discrepancy between their description of China’s carbon markets and the observations presented in this paper. The said scholars claim that China’s carbon markets are characterized by ‘efficient emission reduction, a fair allocation mechanism, as well as transparent and orderly regulation’, while this paper finds that China’s environmental governance is led by state power. Therefore, it is imperative to have an accurate understanding of China’s environmental governance system to make informed judgments about the operational mechanisms of China’s carbon markets.

2.1. China’s Environmental Governance System

China’s environmental governance began in the 1970s, and the Environmental Protection Law of China (Interim) issued in 1979 established ‘a government-led command-and-control model of environmental administrative control’.Footnote11 Article 26 of the 1982 Constitution included ‘ecological environment’ in its amendment, stating that ‘The state shall protect and improve living environments and the ecological environment, and prevent and control pollution and other public hazards’. The state’s authority in environmental management was formally established at that time. In addition, Article 10 of the Environmental Protection Law further stipulates that the environmental protection administrative department of the State Council shall conduct unified supervision and management of environmental protection work throughout the country; and the environmental protection administrative departments of the local people’s governments at and above the county level shall conduct unified supervision and management of the environmental protection work within areas under their jurisdiction.Footnote12 This has established an administrative framework where, at the organizational level, governments at all levels play a leading role in environmental protection. Furthermore, Article 1 of the Constitution designates the Communist Party of China (CPC) as the governing party, which fulfills its core role of ‘exercising overall leadership and coordinating the efforts of all sides’ within China’s governance system.Footnote13 As a result, China has gradually formed an environmental governance system where ‘Party committees exercise leadership, the government plays a leading role’,Footnote14 and Party committees and the government jointly assume responsibility.

The characteristics of China’s environmental governance have important impacts on the nature of China’s carbon market. Thus, what are the characteristics of China’s environmental governance that set it apart from the West?

First, the power of environmental governance is increasingly concentrated at all levels of government. In order to address increasingly severe environmental issues, environmental governance aims to achieve environmental targets in a rapid and streamlined manner. Both legislative and judicial authority in China are distinguished by stringent guidelines and drawn-out processes. Acknowledging this, the administrative power supports ‘top-down implementation’ and ‘rapid mobilization’, which reinforces the tendency of China’s environmental management to prioritize Party and government departments.

Second, public participation plays a small role in environmental governance. Compared with other fields, administration-led environmental governance encounters particularities in two respects. On the one hand, environmental issues are rather complex and uncertain, which requires environmental decision-makers to be equipped with solid, comprehensive professional knowledge. On the other hand, due to the urgent nature of environmental problems, ‘decision-making timeliness’ has always been a top priority in the value hierarchy of environmental governance. As a result, government departments are more inclined to rely on technical experts and political elites in decision-making and have low expectations for and even show exclusion of public participation.

Third, fast-response mechanisms like ‘campaign-style governance’Footnote15 are being promoted. In the practice of social governance since 1949, ‘some strategies, approaches and methods of successful political mobilization have been employed in government administrative implementation, and have become an important means of accomplishing tasks regarding social reform and economic development proposed by the Party’.Footnote16 According to Xu, ‘Over time, these strategies, approaches, and methods of political mobilization have been internalized in the administrative implementation system to form a unique pattern’.Footnote17 China’s environmental governance, influenced by such a behavior model, has obvious characteristics of urgency, singularity, and temporariness. Therefore, various characterizations as ‘special governance’ and ‘campaign-style carbon reduction’ are well established as the norm.

The above analysis suggests that China’s environmental governance system, consistent with state intervention theory, is demonstrably different from the market-based governance model. This further supports the central argument of this paper. In fact, China’s environmental governance consistently reflects the will of the Party and the state and is always subject to the control of state power. This is the case regardless of the construction of governance organizations or the selection of governance mechanisms. China’s environmental governance is a process featuring centralized power and political mobilization, and it is the product that aligns with the characteristic of Chinese Party Politics. Based on this premise, this paper characterizes China’s environmental governance as an administration-led model, distinguishing it from the aforementioned market-based governance model.

2.2. Achievements and Application Scope of the Administration-Led Model

The so-called ‘administration-led model’ is an outcome that is unique to China’s political context and specifically refers to an environmental governance paradigm where the will of the Party and government is the main internal driving force. Administrative authority and elite participation serve as supporting forces, and operating costs are met through the mobilization and investment of national resources.Footnote18 Research on strengthening state intervention in environmental governance originated in the West as early as the 1970s.Footnote19 Despite this, it is the more recent example of environment governance in China that establishes and develops the interventionist administration-led model. The underlying reason for this is the significant compatibility between this model and China’s political party system, the economic foundation of public ownership as well as the practical needs of environmental governance.

First, the administration-led model aligns with China’s political party system. As a socialist country, ‘the leadership of the Communist Party of China is the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics’.Footnote20 With ‘the CPC Central Committee’s authority and centralized, unified leadership’,Footnote21 China’s environmental governance has relied on the ‘top-down’ power of the Party and government over the long term. The ‘marked advantages of socialism which has the ability to mobilize resources to accomplish major initiatives’ also indicate that environmental governance cannot be divorced from the unified mobilization by administrative power. Under the political system characterized by the Party’s overall leadership and the integration of the Party and the government, the process of China’s environmental governance is mainly driven by the Party and the government.Footnote22 Meanwhile, due to the institutional inertia of ‘Big Market, Small Government’, the strengthened role of the Party and the government has undermined the function of market mechanisms, influencing the development of market incentives in China’s environmental governance. Consequently, the administration-led model is China’s dominant model of environmental governance in practice.

Second, the administration-led model also caters to the socialist economic system, in which public ownership plays the leading role. In essence, environmental governance refers to the allocation and utilization of environmental capacity through institutional design. The Constitution of China stipulates that ‘All mineral resources, waters, forests, mountains, grasslands, unreclaimed land, mudflats and other natural resources are owned by the state’.Footnote23 Therefore, China established a ‘unitary model of public ownership of natural resources, where the state or government exercises ownership rights on behalf of all national citizens’.Footnote24 Environmental capacity, as an integral part of ecological resources, is also owned by the state. Given the system of state ownership of natural resources, the state determines the ownership and allocation of environmental capacity and has an absolute say in this regard. This determines that it is difficult to achieve the ideal market regulation in the allocation and utilization of China’s environmental resources, as well as the governance of environmental issues. Therefore, it makes sense that the government carries out environmental governance through administrative intervention.

Third, the administration-led model closely aligns with the practical needs of China’s environmental governance, exhibiting high compatibility with such typical environmental governance settings as formulation of environmental policy and enforcement, of environmental penalties. For instance, in China, governments at various levels are the main actors responsible for the formulation and implementation of environmental policies.Footnote25 However, local government leaders, influenced by the so-called ‘promotion tournament’ and departmental interests, can scarcely prioritize environmental protection over local economic interests. Facing inspections from higher-level authorities, some local governments are even willing to engage in ‘cat and mouse’ game-like collusion with polluting enterprises.Footnote26 In order to address local protectionism and respond to various unanticipated environmental crises, state intervention mechanisms such as the ‘Central Ecological Environmental Protection Inspector’, conducive to centralized power, have been proposed and adopted. Besides, China is facing severe resource and environmental constraints, and has to meet growing expectations for proactive environmental regulation. This necessitates the introduction of strong government intervention.Footnote27 To that end, the Environmental Protection Law of China (2014 Revision) stipulated ‘the Daily Penalty system’,Footnote28 Footnote29‘forced shutdown’, and other administrative penalties that highlight the command-and-control model,Footnote30 effectively addressing the imbalance between the costs of environmental compliance and non-compliance. The aforementioned examples demonstrate the effectiveness of the administration-led model in addressing environmental crises and ensuring public health.

While the administration-led model has shown adaptability and resilience in various environmental governance settings in China, it is also recognized that the model is primarily concerned with fast response to environmental crises, and that its high regulatory costs have been subject to criticism. This indicates that the scope of the model’s application is limited, which does not suit for the typical settings of Western environmental governance, such as carbon market.

3. The Operational Mechanism of China’s Carbon Markets

The aforementioned section stated that Western carbon markets exhibit typical features of efficient emission reduction, a fair allocation mechanism, as well as transparent and orderly regulation. The efficient emission reduction is achieved due to the extensive support and rapid response from the market entities as their actual demands have been considered during the establishment of the carbon market; the fair allocation mechanism is ensured because the carbon market operates based on the supply and demand relationship, allowing the law of value to function without administrative interference; orderly regulation is guaranteed because market rules gain widespread recognition and are voluntarily observed among market entities since these rules are derived from the long-term industry practices. In contrast, China’s administration-led carbon markets, determined by the state and implemented by governments, take rules formulated by the government as the trading basis. Therefore, its operational mechanisms and outcomes differ significantly from those of typical Western carbon markets.

3.1. China’s Carbon Markets Is Established by the State

Under the marketization model, the establishment of carbon markets is driven by market demand. In contrast, under the administration-led model, whether and how to build carbon markets are determined by state power. China’s carbon markets experienced two stages: pilot and the national carbon market. In the first stage, establishing the carbon emissions trading market was primarily based on the exploration of pilot areas. According to the Notice on Carrying out Pilot Programs on Carbon Emissions Trading (the Notice), governments in the pilot localities were responsible for setting up special task force, allocating special funds, developing their pilot schemes for carbon emissions trading, and implementing these schemes after they were reviewed and approved by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Local governments, authorized by the NDRC, formulated management measures for carbon emissions trading in their areas, which outlined the list of enterprises included in the carbon market, the allocation method for carbon allowances, designated carbon emissions trading venues, the carbon emissions trading process, and compliance details. In the second stage, the MEE was entirely in charge of the establishment of the national carbon market. In December 2020, the MEE promulgated the Measures for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (hereinafter referred to as the Administration Measures) and determined the allowance allocation plan and the list of key emitting enterprises. Subsequently, the MEE rolled out the Rules for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Registration, Rules for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading, and Rules for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Settlement for the ease of the implementation of the Administration Measures, as well as the registration, administration, and settlement in the national carbon market. The action and framework of the market establishment are completely government-led in both pilot markets and the national carbon market, and the role of the regulated enterprises and other market entities is rather limited.

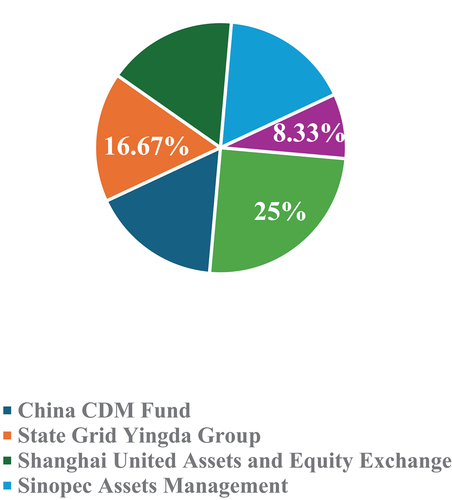

Taking the Carbon Emission Rights Exchange (CEREX), the core institution for operating the carbon market, as an example, the carbon emission rights exchanges in the seven pilot regions were set up by the government rather than by the market on its initiative. They run on a non-profit basis and can be classified as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) based on their nature of stock rights. presents the five largest shareholders of the Shanghai Environmental Energy Exchange (CNEEEX).Footnote31 They are China CDM Fund (16.67%); State Grid Yingda Group (16.67%); Shanghai United Assets and Equity Exchange (16.67%); Sinopec Assets Management (16.67%); and, China Baowu Steel Group (16.67%),Footnote32 all of which are policy funds or SOEs. Even if the remaining 25% of shareholders were to come from private or foreign-invested enterprises, it could not change the monopoly position of state-owned shareholders in the governance structure. Since their inception, the government has designated the exchanges as carbon emissions trading institutions and has taken over some administrative management functions on behalf of the respective pilot-area regulators.Footnote33

This is a far cry from the philosophy behind establishing carbon emissions exchanges in mature Western markets. Securities and futures exchanges, such as the Intercontinental Exchange, Chicago Climate Futures Exchange, European Climate Exchange, and Green Exchange, were built by market entities due to the ‘path dependence in businesses and meticulous cost-benefit considerations’.Footnote34 These trading agencies were established with a bottom-up model by social capital based on cost–benefit analysis and market reasoning. In contrast, carbon emission exchanges in China were built by the government based on a top-down model, which do not focus on profitability but responsive to central policies and assist the government in achieving its performance targets.Footnote35

3.2. The Operation of China’s Carbon Markets Is Driven by Governments

Under the marketization model, the operation of carbon markets relies on the mechanism of ‘property rights + market’ to ensure the fairness of carbon asset allocation and the effectiveness of market competition.Footnote36 Under the administration-led model, those allocation schemes for carbon allowances are predominantly led by governments at different levels. In such cases, market transactions are typically not primarily driven by supply–demand relations, and the occurrence of certain transactions may even result from ‘campaign-style’ law enforcement. According to the Administration Measures and Implementation Plan for the 2021–2022 National Carbon Emissions Trading Allowance Setting and Allocation (power generation industry) (hereinafter referred to as the Allocation Plan), only the MEE enjoys the power to allocate carbon market assets, while carbon market entities, carbon emission exchanges, third-party stakeholders and the public have little say in this process. Even when market entities believe that state power has unfairly treated or infringed upon their rights, no relief is available through the judiciary. The Administration Measures in force only stipulate that parties involved may apply to the provincial Department of Ecology and Environment for review if they have objections to the allowance allocation plan.Footnote37 It does not mention whether they can file an administrative review or lawsuit in such cases or how to do that. In addition, the Interim Regulation (draft) does not state how concerned parties can seek legal relief if faced with legal disputes resulting from allowance allocation. The Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (interim) only applies to disputes among trading parties or between trading parties and trading institutions, and it does not grant the parties rights to initiate a review or litigation.

‘Campaign-style’ carbon reduction has seriously distorted the supply-demand-oriented incentive mechanisms in China’s carbon markets. As a term exclusive to China, it describes the way that local governments mobilize the regulated enterprises to take immediate actions to meet the carbon reduction goals set by higher-level authorities. In recent years, environmental quality has gradually become one of the primary performance indicators for officials. Currently, the central government conducts routine assessments, special assessments, and annual assessments of environmental quality among local government departments and their leading officials. Local governments will generally set periodic carbon emission goals and tasks based on the assessment timetable to pass these assessments. As a result, the regulated enterprises will participate in carbon emission reduction campaigns upon the request of local governments before each assessment. In other words, decision-making on carbon emissions trading by regulated enterprises is being distorted by the incongruent cycles of administrative assessments and carbon market operations. Consequently, allowance trading veers away from the actual willingness of carbon market entities, and trading prices fail to reflect the carbon emission cost. For example, Hunan Province enforced the closure of dozens of coal mines to meet the carbon peak emission reduction targets in 2019. This led to a widespread shutdown of thermal power plants due to the surge in coal prices and caused extensive electricity shortages in the province in 2020. To address the power supply crisis caused by such a practice of ‘campaign-style carbon reduction’, the provincial government issued the ‘Emergency Notice on Starting the Orderly Electricity Consumption in Winter for Carbon Peak Targets’ at the end of 2020 and used power cuts to reduce energy consumption.Footnote38 This severely disrupted local businesses’ production and residents’ life and deeply distorted the order of power supply and the trading foundation of carbon markets.

3.3. The Trading Rules of China’s Carbon Markets Are Formulated by Governments

Trading rules serve as an approach to realizing carbon markets’ functions. Under the guidance of marketization model, carbon markets take advantage of detailed trading rules, diversified carbon asset trading methods, and categories to incentivize market entities to explore practical ways of carbon asset allocation by themselves. In contrast, carbon markets under the administration-led model retain the ‘planned’ pattern where state power authorities formulate trading rules and market entities passively accept trading products, causing a lack of incentives. The current Administration Measures stipulate that the scope of traders and traded products in China’s carbon markets are entirely determined by the MEE, and it does not consider the demand of the market entities. Therefore, it is possible to identify the market rules as the outcome of state intervention. Despite China’s carbon market being established for a number of years, it remains overwhelmingly challenged by a number of factors. These include its limited number of trading participants, the nature of its single-traded products, its narrow industry coverage, and its weak price adjustment mechanisms.

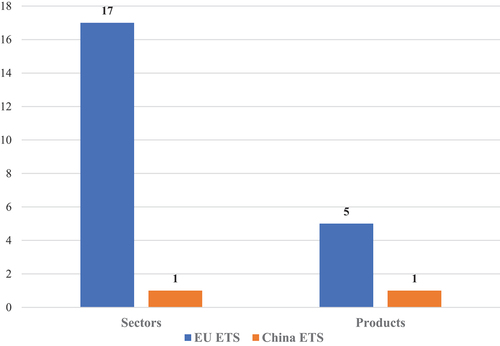

For example, as illustrated in , traded products in China’s carbon markets are currently limited to spot trading of carbon emission allowances without carbon futures or options. In comparison, the EU ETS has up to five trading varieties and applies to 17 industries, while the China ETS only applies to the power sector.Footnote39 The limited diversity of traded products and trading methods has undermined the market’s vitality.Footnote40 To address this problem, carbon market regulatory authorities once assumed supporting the development of carbon financial products and services and exploring the operation of carbon derivatives and businesses such as carbon futures.Footnote41 However, the Futures and Derivatives Law has yet to include carbon futures in its adjustment range.Footnote42

Figure 2. The sectors and products covered by the carbon markets in Europe and China

In addition to the limited number of traded products, another flaw of China’s carbon market is the lack of financial attributes. ‘Emission trading through time, emission trading between firms, and emission averaging between different sources within a firm’ are three main approaches to reducing compliance costs for regulated enterprises.Footnote43 The banking and borrowing of emission allowancesFootnote44 represent a crucial institutional innovation that makes allowance usage unconstrained by time and space. Banking allows enterprises to store their existing allowances for future use; borrowing means enterprises can consume more emission allowances within a period beyond the standard and pay them back in the future.Footnote45 Existing research shows that the mechanisms of banking and borrowing allow the regulated enterprises to adjust their emissions more flexibly over different periods, lowering the cost of complying with the emission standard.Footnote46 The mechanism of banking, which helps improve environmental performance and reduce cumulative compliance costs, provides a flexible solution to addressing problems regarding production levels, compliance costs, and other uncertain factors that affect allowance demand.Footnote47 In addition, it makes the emissions reduction plan more acceptable economically and politically for the regulated enterprises. With the allowance banking mechanism, achieving the overall emissions reduction target would be easier.Footnote48 Prohibition of carbon allowance banking will lead to low emission reduction efficiency and may hinder regulated enterprises from lowering compliance costs.Footnote49 Regrettably, these market-based trading mechanisms mentioned above can hardly perform effectively under the administration-led model, and thus have not been adopted by carbon exchanges in China.Footnote50

Based on these observations and analysis of the three aspects of the operational mechanism of China’s carbon markets, it can be seen that the operational logic of China’s carbon markets is not built on the ‘path dependence in businesses and meticulous cost-benefit considerations’,Footnote51 but is rather maneuvered by undue administrative intervention. The operation of the carbon market is essentially based on the governance of governments rather than self-governance. Emphasis on administrative goals makes the markets ignore the internal driving forces from market incentives. Overall, centralization of government power is a prominent feature of the carbon market. An imbalance of power between governments and markets has resulted in a lack of autonomy and initiative among market entities. Meanwhile, in order to win the promotion championship, local governments frequently launch ‘campaign-style carbon reduction’. This has seriously disrupted the carbon market’s functions of supply regulation and price discovery. Furthermore, due to the government’s heavy interference, financial derivatives like carbon futures, options, and forwards are not allowed to be traded, and the carbon market participants are limited to key emitting enterprises. The rule-design makes it clear that China’s carbon market does not promote competition, making it difficult to achieve the goal of effective emission reduction. Based on this, a primary conclusion is reached: Although the Chinese government endeavours to integrate with the mainstream rules and systems for global climate governance using the carbon market, a semi-market-oriented regulated instrument, China’s carbon markets are not market-oriented due to the longstanding practice of ‘big government, small market’. The pronounced administration-led feature has permeated all links of the generation and operation of the carbon market, and market mechanisms cannot be effectively stimulated to advance carbon emission reduction while this remains the case.

4. Consequences of Administrative Dominance on Carbon Market Operation

The above analysis shows that China’s carbon market under the administration-led model is merely an administrative tool in the guise of a market. This indicates that the claim of Chinese government officials and some scholars is doubtful. The paper will disprove such claim by revealing the severe consequences of the administration-led model.

4.1. Administrative Dominance Affects the Effectiveness of Resource Allocation in Carbon Markets

The emission reduction effect and market competition intensity are positively correlated. Fierce market competition contributes to more efficient resource allocation in the carbon market and greater positive incentives for the regulated enterprises to advance technological innovation and reduce emissions. In the absence of adequate competition, the carbon market’s ability to reduce carbon emissions is limited. This is because carbon emissions trading cannot offer sufficiently profitable incentives to market entities, and leads to a lack of willingness to voluntary engage with the carbon market. The market and price mechanism can hardly affect the atmospheric environmental capacity (AEC) allocation in the administration-led carbon market. Distortion of the market mechanism further leads to price mechanism failures, making it difficult for the carbon product prices to reflect the resource acquisition cost truly. This will not only sap the appetite of carbon market entities for trading but also inhibit market liquidity, which will seriously influence the effectiveness of resource allocation in the carbon market. The sluggish nature of China’s carbon market trading is a typical reflection of this market characterization.

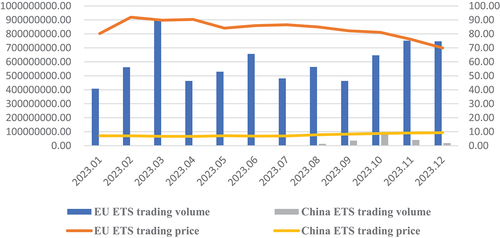

presents the 2023 annual trading data of the China ETS and the EU ETS, indicating that the trading activity of the China ETS lags far behind that of the EU ETS in terms of total trading volume and trading price. In terms of total trading volume, the EU ETS reached 7,162 million tons, which is 33.7 times that of the China ETS’s trading volume of 212 million tons. Regarding trading price, the EU ETS recorded a monthly highest trading price of €91.9 and a lowest of €69.92, while the China ETS had a monthly highest of only €9.28 and a lowest of only €6.66.Footnote52

Figure 3. The transaction data of China ETS vs. EU ETS 2023.

Another typical manifestation of administrative dominance is the ‘administrative cycles’ in China’s carbon allowance trading. In 2023, China ETS’s trading volume was concentrated in October, with a value of 93 million tons, accounting for 43% of the total annual trading volume. On the other hand, the monthly trading volume in the EU ETS was relatively balanced. Even in March, with the highest trading volume, the trading volume of 894.54 million tons only made up 12% of the total annual trading volume.Footnote53 This strange phenomenon can be attributed to the disruption of artificial compliance cycles as compared to the spontaneous operation of the market. The central government of China uses the year-end verified data as the basis for carbon reduction assessments for local governments. Given that the concentration of compliance at the end of December may affect data statistics and assessments, local governments often require companies to fulfill compliance requirements before November 15. It is this administrative practice of setting deadlines for compliance that leads to the surge in trading volume in China’s ETS in October each year. This compliance-driven mechanism has led to severe non-market-based distortions in carbon allowance trading, which should have been based on enterprises’ actual emission needs. The trading no longer serves as a barometer of supply and demand relations but has become a weatherglass of administrative interventions. It is evident that government policies have a significant impact on China’s carbon allowance market. To date, the compliance by enterprises is more motivated by the disincentive of severe penalties from the government, and there is lack of enthusiasm for voluntary participation.Footnote54

4.2. Damage to Market Fairness Caused by Administration-Led Carbon Asset Allocation

The allocation of carbon allowances is related to the realization of the public interest that includes multiple conflicting interests. When dealing with conflicts of interest, the government tends to prioritize organized entities and does not pay sufficient attention to the interests of those scattered, unorganized groups.Footnote55 Because the administration-led allocation mechanism is not based on public consultation,Footnote56 administrative decisions made by political bureaucrats and technical experts may undermine the ability for equitable outcomes to be distributed across a broad range of impacted groups. A general consensus exists among academics that the deficiencies in administrative decision-making under instrumentalism can be alleviated through broader public participation to direct institutional rationality toward serving the interests of the majority.Footnote57 Public participation mechanisms enable stakeholders to debate, negotiate, and compromise on their respective interests and ensure that government decisions consider a broader spectrum of interests, ultimately enhancing the acceptability of those decisions.Footnote58 China’s current carbon asset allocation mechanism adopts a one-size-fits-all approach of ‘intensity control’ and allocates carbon allowances to numerous state-owned major emitters for free. As a result, the allocation of emission allowances is rather uneven and cannot reflect the core concerns of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and the public. The absence of public participation in allocation mechanism has weakened the SMEs’ rights to fair competition and disregarded the public’s reasonable concerns. China’s carbon markets currently apply only to the electricity industry, which is largely monopolized by state-owned enterprises. Statistics indicate that the market share of state-owned power generators exceeds 90%. Private enterprises are in a relatively disadvantaged position in the carbon market and have little influence in allocating carbon emission allowances. From the perspective of substantial fairness, it is difficult for the existing allocation mechanism to ensure the fairness of competition in the carbon market.

The top-down allocation mechanism disregards the justified demands of carbon market entities and the public, and the inadequacy of right relief further undermines the legitimacy of carbon market operations. The setting of caps on emissions, the formulation and implementation of allocation plans, and the mandatory allowance surrender and the market exit mechanisms are critical to the core interests of carbon market entities. The construction of the legal framework for carbon markets should emphasize the proper relief for these participants in the carbon market, especially in such an administration-led, government-regulated carbon market. For example, since the launch of the EU ETS, it has become commonplace for EU member states to file lawsuits against their governments or the European Commission. Litigation typically involves the National Allocation Plans (NAPs), the coverage of carbon markets, and the actual allocation of emission allowances.

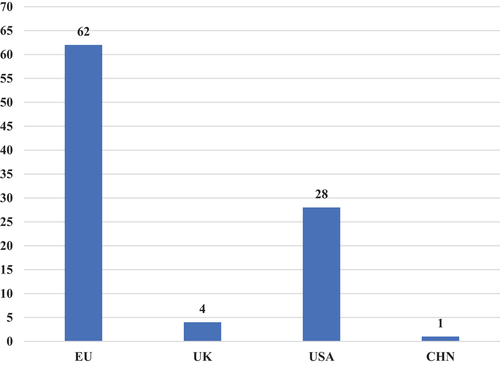

As of March 2024, there were 62 lawsuits related to carbon markets in the EU, four in the UK, and 28 in the USA, as depicted in Footnote59 Some representative cases include: Germany initiated litigation against the Commission over its right to amend the NAP; Drax Power sued the Commission for the right of EU member states to adjust the total carbon emissions; Société Arcelor Atlantique took legal action against the French government over the inclusion of the steel industry in the EU-ETS; and the UK brought a lawsuit against the Commission’s decision on public consultation.Footnote60 Broader access to judicial remedies on environmental issues has become one of the four critical pillars for the EU-ETS to achieve carbon emission reduction. This is especially the case in community decisions related to carbon emission allowance trading.Footnote61

Figure 4. The number of carbon market lawsuits in the European Union, the United Kingdom, the United States and China.

Regrettably, there was only one administrative lawsuit in China that was truly related to the carbon market, and the enterprise ultimately lost the case.Footnote62 The reason contributed to the outcome is that the proper relief pathways are only stipulated in the general provisions of the Environmental Protection Law and the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law, and there are no specific, detailed provisions to implement the legal responsibilities. As a new mechanism for climate governance, participant demands, dispute resolution procedures, and determinations of legal facts in the carbon market differ significantly from traditional environmental legal issues. Therefore, the lack of proper relief mechanisms and insufficient supply of law will severely undermine the foundation for fairness, further affecting the actual efficiency of the carbon market.

4.3. Rent-Seeking and Corruption in the Administration-Led Carbon Market

On the one hand, the government promotes public welfare by providing public services. On the other hand, due to departmental and individual interests, the government can hardly avoid its self-serving nature because it is also a rational economic entity acting in its own self-interest. Such self-interest leads to constant power expansion and artificial scarcity, giving rise to rent-seeking and exacerbation of corruption.Footnote63 In administration-led carbon markets in China, weak market mechanisms and the absence of public supervision have further intensified rent-seeking. It occurs during such processes as formulating emission policies, setting emission caps, allocating emission allowances, collecting and accounting emissions data, and executing administrative penalties.Footnote64

Under the free allocation model, rent-seeking will ultimately lead to unpaid AEC expenditure and earnings of regulatory agencies,Footnote65 seriously damaging the fairness and effectiveness of emissions trading schemes. Of the more than 2,000 power generation companies in China’s carbon markets, state-owned China Huadian Corporation, China Energy Corporation, China Datang Corporation, State Power Investment Corporation, and China Huaneng Group (the ‘big five’) have a combined market share of over 40%. They benefit from significant advantages in market control, capital influence, information dominance, and government lobbying capability. Furthermore, their interests are closely related to those of the multi-level government financiers, making it easier for the big five to persuade government officials and wield influence over their decisions regarding the carbon market. Such ‘legal’ but unique relations between these enterprises and governments have made rent-seeking harder to notice.Footnote66 Statistics showed that emission allowances allocated to the big five occupied up to half of the total, and these allowances they received exceeded their actual emissions to varying degrees. This set of circumstances has given rise to the problem of mismatched carbon assets. Furthermore, China’s carbon markets have also experienced systematic data falsification, which was used to conceal evidence of rent-seeking and corruption. For instance, GreenTech Group, a carbon emission verification agency, was involved in tampering and fabricating carbon content test data to meet the regulated entities’ illegal demands of artificially reducing carbon emissions and thus evading emission reduction obligations. It also prompted companies to falsify coal samples and to produce substitute samples to replace those legally collected mixed samples.Footnote67 Similarly, verification agencies such as Qingdao Xinuo New Energy Co., Ltd. and SinoCarbon Innovation & Investment Co., Ltd. have negligently allowed signatories to sign verification reports without conducting verification,Footnote68 making the verified data incongruent with carbon emissions in reality. Concurrently, the corrupt behavior of civil servants abusing their power for personal gains on carbon markets is equally concerning. For instance, a corruption case concerned an official named Zhang from the Finance Bureau in Beilin District, Suihua City, Heilongjiang Province. Zhang produced a false declaration of carbon emission data to assist Yongfeng Paper Mill in obtaining project approvals for bribes,Footnote69 causing severe reputational damage to state organ oversight of carbon markets. These cases serve as reminders that the authenticity of data that serves as the foundation of carbon market trading faces severe tests under the administration-led model lacking effective supervision.

5. Conclusion

Given the nature of China’s environmental governance as one characterized by government intervention, this paper has proposed and constructed a new administration-led model as a theoretical tool for studying environmental governance issues in China. It has taken this model as an entry point, and from this perspective offered observations on the establishment, operation, and trading rules of China’s carbon markets in reality. This paper has made a case for characterizing the carbon market in China as one with a significant degree of government centralization and a disproportionate reliance on ‘policy-driven governance’ rather than ‘market autonomy’. Consequently, China’s carbon market is essentially an administrative tool in the guise of a market. The carbon market transplanted to China has failed to achieve the desired goals set by the Chinese government and has led to serious issues such as institutional rent-seeking and emission data falsification. And the so-called ‘market-based mechanism’ has ultimately turned into a tool for showcasing political achievements in certain regions. It is anticipated that these systemic problems will lead to greater pressure on China’s climate governance and green transition.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The World Bank, ‘China Country Climate and Development Report’, October 12, 2022. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/publication/china-country-climate-and-development-report.

2 Xi Jinping, ‘Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era Delivered at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China’, October 27, 2017. Accessed April 1, 2024.

3 National Development and Reform Commission, ‘The Notice of the National Development and Reform Commission on the Issuance of the Establishment Plan for the National Carbon Emissions Trading Market (Power Generation Industry)‘, 18, December 2017. Accessed April 3, 2024.

https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/ghxwj/201712/t20171220_960930.html.

4 Qi Shaozhou, Cheng Shihan, ‘Experience, Effectiveness, Challenges and Policy Reflections on Carbon Market Construction in China’, International Economic Review 9, (2024).

5 Huang Xianglan, Zhang Xunchang and Liu Ye, ‘Does China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Policy Fulfill the Environmental Dividend?‘, Economic Review 6, (2018), p. 86.

6 Hu Yucai Ren Shenggang, Wang Yangjie and Chen Xiaohong, ‘Can Carbon Emission Trading Scheme Achieve Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction? Evidence from the Industrial Sector in China’, Energy Economics 85, (2020), pp. 104, 590.

7 See Interim Regulations on the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading, art 3.

8 Li Ronghua, Du Hao, ‘Emission Reduction Effects and Regional Differences of Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot Under the ‘Dual Carbon’ Goals‘, Research on Economics and Management 44(11),(2023), p. 25.

9 ‘Officials from the Ministry of Justice of the People’s Republic of China and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China answered questions from reporters regarding the Interim Regulations on the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading’, February 5, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywdt/zbft/202402/t20240205_1065855.shtml.

10 ‘Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Significant Increase in Activity of National Carbon Emissions Trading Market’, February 26, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.eco.gov.cn/news_info/68560.html.

11 LYU Zhongmei, Wu Yiran, ‘Seventy Years of Environmental Rule of Law in China: From History to the Future’, China Law Review 05, (2019), p. 102.

12 The competent department of environmental protection administration under the State Council is responsible for the formulation of policies and laws regarding environmental governance, while the competent departments of environmental protection administration of the local people’s governments at all levels are responsible for promoting and implementing environmental governance. Other relevant departments of governments at all levels shall cooperate within their area of responsibility in supporting the environmental regulatory governance system.

13 ‘Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century’, Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021–11/16/content_5651269.html.

14 The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council, ‘Guiding Opinions on Building a Modern Environmental Governance System’, Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020–03/03/content_5486380.html.

15 Campaign-style governance, a term exclusive to China, refers to an administrative means used by local governments to meet the certain targets set by higher-level authorities.

16 Xu Xianglin, ‘Systemic Constraints of Administrative Approval System Reform and the Transformation of the Administrative Implementation System’, Research Reports on the Politics of Contemporary China (2003), p. 166.

17 Xu Xianglin, ‘Constrains of Chinese Administrative Permit System and Institutional Innovation’, Journal of Chinese Academy of Governance 06, (2002), p. 20.

18 The term ‘administration-led’ in this paper is a concept in the context of environmental governance.

19 Ophuls W, Ecology and the Politics of Scarcity (San Francisco: W.H. Freeman Press, 1977); Ophuls, W, Requiem for Modern Politics: The Tragedy of the Enlightenment and the Challenge for the New Millennium (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997); Mark Beeson, ‘The coming of environmental authoritarianism’, Environmental Politics 19(02), (2010), p. 276.

20 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, art 1, cl 2.

21 ‘Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Upholding and Improving the System of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Advancing the Modernization of China’s National Governance System and Capacity’.

22 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, art 26; Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, art 6, cl 2.

23 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, art 9, cl 1.

24 Deng Haifeng, Luo Li, ‘Systematic Outline of the Pollution Emission Right’, Journal of Northwest University of Political Science and Law, 06, (2007), p. 76.

25 Shi Muhua, ‘Reform and Prospects of China’s Environmental Policy Making Mechanism’, Environmental Protection 41(Z1), (2013), p. 61.

26 Benjamin Van Rooij, ‘Implementation of Chinese Environmental Law: Regular Enforcement and Political Campaigns’, Development and Change 37, (2006), p. 57.

27 Tan Binglin, ‘Enforcement of the Regulatory Function of Environmental Administrative Penalties’, Chinese Journal of Law 40(04), (2018), p. 151.

28 ‘Where an enterprise, public institution or other producer or business operator is fined due to illegal discharge of pollutants, and is ordered to make correction, if the said entity refuses to make correction, the administrative organ that makes the punishment decision pursuant to the law may impose the fine thereon consecutively on a daily basis according to the original amount of the fine, starting from the second day of the date of ordered correction’. (Environmental Protection Law, art 59).

29 Du Qun, ‘Re-examination of the Daily Penalty in Environmental Protection Law: From the Perspective of Local Regulations’, Modern Law Science 40(6), (2018), p. 175.

30 Anthony I.Ogus, Regulation: Legal Form and Economic Theory (Luo Meiying tr, China Renmin University Press, 2008), p. 153

31 The Shanghai Environmental Energy Exchange is the only trading venue for the national carbon market.

32 Tianyancha(天眼查), Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.tianyancha.com/company/585253674.

33 You Mingqing, Wang Haijing, ‘Logic of the Change of Carbon Emissions Trading System in China: Comments on the Interim Regulations on the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (Draft for Soliciting Opinions)‘, Journal of Jishou University (Social Sciences) 41(01), (2020), p. 48.

34 Zhang Yang, ‘Local Alienation and Regulatory Rectification of China’s Carbon Emissions Exchanges’, Global Law Review 45(02), (2023), p. 160.

35 Zhang Yang, ‘Local Alienation and Regulatory Rectification of China’s Carbon Emissions Exchanges’, Global Law Review 45(02), (2023), p. 160.

36 Cheng Xinhe and Chen Huizhen, ‘On the Two Dimensions of the Legal System Concerning the Allowances Allocation in Carbon Emissions Trading: The Case of Guangdong’, Journal of South China Normal University (Social Science Edition) 02, (2014), p. 103.

37 Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (Interim), art 16.

38 Wang Wen, Zhao Yue, ‘Lessons from Carbon Emission Reduction Experience in Europe and America and Their Implications for China’, New Economy & Future Industry 02, (2021), p. 28.

39 The sectors covered by the EU carbon market include electricity and heat generation, oil refineries, steel works, production of iron, aluminium, metals, cement, lime, glass, ceramics, pulp, paper, cardboard, acids and bulk organic chemicals, aviation, and maritime. In addition, the products of the EU ETS include European Union Allowance (EUA), EUA Futures, EUA Options, European Union Aviation Allowance (EUAAs), and European Union Reduction Units (ERUs),while the products in the China’s carbon market currently only include Carbon Emission Allowance (CEA). See European Commission, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/scope-eu-emissions-trading-system_en; Shanghai Environmental and Energy Exchange, Accessed March 07, 2024. https://www.cneeex.com/c/2022-06-29/491306.shtml.

40 Yuan Jianqin, ‘Progress, Problems, and Policy Suggestions for the Construction of the National Carbon Market’, Energy of China 43(11), (2021), p. 63.

41 Opinions on Promoting Investment and Financing to Address Climate Change (Huan Qi Hou, 2020, No 57).

42 The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, China’s top legislature, passed the Futures and Derivatives Law of the People’s Republic of China (the Law) on April 20, 2022. Nevertheless, the Law only described the types of futures and derivatives in generalities. It indicated whether it could serve as an authorization basis for trading carbon futures and regulating the market.

43 Catherine Kling, Jonathan Rubin, ‘Bankable Permits for the Control of Environmental Pollution’, Journal of Public Economics 64(1), (1997), p. 101.

44 Banking and borrowing allow firms to transfer emissions at different times: ‘banking’ means that firms can save emission allowances for use at a future time, while ‘borrowing’ allows firms to borrow allowances to complete compliance and to repay the borrowed allowances in the future. See Catherine Kling, Jonathan Rubin, ‘Bankable Permits for the Control of Environmental Pollution’, Journal of Public Economics 64(1), (1997), p. 101.

45 Catherine Kling, Jonathan Rubin, ‘Bankable Permits for the Control of Environmental Pollution’, Journal of Public Economics 64(1), (1997), p. 101.

46 Jonathan D. Rubin, ‘A Model of Intertemporal Emission Trading, Banking, and Borrowing’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 31(3), (1996), p. 270.

47 Ellerman A. D, Harrison Jr D, ‘Emissions Trading in the US: Experience, Lessons, and Considerations for Greenhouse Gases’, Pew Center for Global Climate Change, (2003).

48 Burtraw, Dallas, Mansur, Erin, ‘Environmental Effects of SO2 Trading and Banking’, Environmental Science & Technology 33, (1999), p. 3489.

49 Joachim Schleich, Karl-Martin Ehrhart, Christian Hoppe, Stefan Seifert, ‘Banning Banking in EU Emissions Trading?’, Energy Policy 34(01), (2006), p. 112.

50 The Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (interim), the highest-ranking legal document, did not involve regulations on the banking mechanism for carbon emission allowances. Even those carbon market pilot areas that permit carbon allowance carrying over, such as Tianjin and Shenzhen, have yet to explain further the carrying over period and methods, let alone carbon allowance borrowing.

51 Zhang Yang, ‘Local Alienation and Regulatory Rectification of China’s Carbon Emissions Exchanges’, Global Law Review 45(02), (2023), p. 160.

52 ‘Annual comprehensive price and transaction information of the national carbon market (20230103–20,231,229)‘, Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.cneeex.com/c/2023-12-29/494958.shtml; Intercontinental Exchange, ‘Products—Futures & Options’, Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.ice.com/products/Futures-Options/Energy/Emissions.

53 Ibid.

54 Chen Xingxing, ‘China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Market: Achievements, Realities, and Strategies’, Southeast Academic Research 290(04), (2022), p. 167.

55 Richard B. Stewart, ‘The Reformation of American Administrative Law’, Harvard Law Review 88(08), (1975), p. 1667.

56 The allocation of allowances in China’s carbon markets is based on sectoral average emission intensity, with allowance distribution directly proportional to the power generation capacity of generating units.

57 Li Youmei, Xiao Ying, Huang Xiaochun, ‘Predicament of Publicness in Social Construction of China and Transcendence’, Social Sciences in China 196(04), (2012), p. 125.

58 Wang Xixin, Zhang Yongle, ‘Experts, the Public and Use of Knowledge: An Analytical Framework for Administrative Rule-Making’, Social Sciences in China 03, (2003), p. 113.

59 ‘Climate Change Litigation Databases’, Accessed March 8, 2024. https://climatecasechart.com/.

60 Wang Yan, Zhang Lei, The Localization of Legal Protection Mechanisms of Carbon Emissions Trading Markets in China (Law Press China, 2016), p. 254.

61 Nicolas Van Aken, ‘The “Emissions Trading Scheme’ Case-Law: Some New Paths for a Better European Environmental Protection’, in Climate Change and European Emissions Trading: Lessons for Theory and Practice, eds. Michael Faure and Marjan Peeters (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008), p. 115.

62 Case of Shenzhen Xiangfeng Vessel Co., Ltd. and Other Administrative Written Judgements of Shenzhen Development and Reform Commission (Yue 03 Xingzhong No. 450, 2016).

63 Krueger, A.O. ‘The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society’, The American Economic Review 64, (1974), p. 291.

64 Wei Zhimin, ‘On the Construction of China’s Carbon Trading Market’, Journal of Henan University (Social Science Edition) 53(05), (2013), p. 49; Chen Xiaohong, Wang Jing, Hu Dongbin, ‘Study on the Effect of Rent-Seeking on Carbon emissions trading Market Performance under Free Carbon Emission Allowances’, Systems Engineering—Theory & Practice 38(01), (2018), p. 94.

65 Yan Pu, Xia Liu, The Social Costs of Rent-Seeking in the Regulation of Vehicle Exhaust Emission [2013] in Chen, F., Liu, Y., Hua, G. (eds) LTLGB 2012: Proceedings of International Conference on Low-carbon Transportation and Logistics, and Green Buildings, 2012, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

66 According to the 2022 annual report of Huaneng Power International, the group had a net profit of RMB 374 million from carbon emissions trading alone. Behind huge profits from carbon trading are a slim possibility of making profits from the upgrading of emission reduction technologies and the ‘gap between the rich and poor’ caused by the uneven distribution of carbon assets. (Huaneng Power International, ‘2022 Annual Report’).

67 ‘Typical Cases Released by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment on Data Falsification in Carbon Emission Reports by Institutions like GreenTech Group (First Batch of Prominent Environmental Issues in 2022)’, Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202203/t20220314_971398.shtml.

68 Ibid.

69 Corruption Case Involving Sun XX and Others [2016] Hei 1202 Xingchu No. 335