Abstract

Background: Prior research demonstrated the relationship between birth order and adolescent risky behavior. The possible connection between the presence of siblings and birth order and underage alcohol abuse is unknown. Methods: Our study involves 10 years of data collection on underage alcohol intoxication in Dutch hospitals. A total of 2,234 patients were included in the current study. Results: Adolescents treated for alcohol intoxication less often have no siblings (6.7%) than the population has (14.8%). Furthermore, middle and youngest children are overrepresented in the patient population. Conclusion: The presence of older siblings is a risk factor for acute alcohol intoxication.

Introduction

The adolescent brain is not a larger variant of a child’s brain, but the result of a unique process in the formation of a complex network of interconnecting neurons. This process is characterized by dendritic pruning, as well as by the strengthening of connections between neurons (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, Citation2005; Dennis, Citation2012). Genetic factors, as well as environmental factors such as birth order, play a key role during this process (Baroncelli et al., Citation2010). During this process, the adolescent brain is prone to risk-taking behavior. This behavior is of all time, can be found in all cultures, and from a sociological, as well as an evolutionary perspective, can be seen as very useful. Risk-taking drives the growth of independence from parents and allows teenagers to make enormous progress in socialization. On the other hand, this risk-taking behavior puts adolescents at risk for health hazards.

The emergence of hazardous risk-taking behavior arises from an asynchronous development of brain regions. It starts with the maturation of networks in the limbic system where emotions arise and impulsive response initiates and ends with the maturation of networks in the prefrontal cortex where impulses are controlled and judgment is promoted (Dennis, Citation2012). This asynchronous development of brain regions puts adolescents at risk for health hazards, such as motor vehicle accidents, unintentional sport injuries, and teenage pregnancy (Irwin, Igra, Eyre, & Millstein, Citation1997). Furthermore, adolescence is a time that can be marked by the emergence of harmful health behaviors, such as smoking, binge drinking, gambling, and substance use (Burnett, Bault, Coricelli, & Blakemore, Citation2010; The Lancet Public Health, Citation2018). Prevention of hazardous risk-taking behavior, such as alcohol use, requires awareness of both risk factors and protective factors.

In the Netherlands, this awareness has led to the development of national preventive strategies regarding underage drinking and eventually resulted in a decline in regular alcohol use among the general Dutch population between ages 12 and 16 years old (Van Laar, Citation2016). Although there has been a decline in regular alcohol use among Dutch adolescents, adolescent drinking behavior remains a subject of concern for parents, doctors, and politicians. The rising trend of admission to Dutch pediatric departments seen in the past decade increases this concern (Nienhuis, Van der Lely, & Van Hoof, Citation2017). Hospital admissions are associated with serious complications, such as reduced consciousness, hypothermia, and electrolyte disturbances (Bouthoorn, Van der Ploeg, Van Erkel, & Van der Lely, Citation2011).

The increase in hospital admissions for alcohol intoxication has prompted the addition of acute alcohol intoxication to the Dutch Pediatric Surveillance System (NSCK). In doing so, risk factors for high blood alcohol concentration (BAC) at admission have been identified: older age, male sex, and higher educational level (Van Zanten, Van der Ploeg, Van Hoof, & Van der Lely, Citation2013). Further identification of protective factors and risk factors remains necessary for the renewal of preventive strategies regarding acute alcohol intoxication. Birth order is considered to be an influential environmental factor and might be related to acute alcohol intoxication. In prior research, birth order has already been associated with both the useful, and the hazardous, aspect of risk-taking behavior.

Several studies have associated birth order with the useful aspects of risk-taking behavior. One study associated birth order with traveling to distant destinations. Compared to firstborns, youngest children are more attracted to traveling to unfamiliar places (Sulloway, Citation1996). Another study among brothers playing major league baseball found that younger brothers were more likely to attempt the high-risk activity of base stealing and more likely to steal bases successfully (Sulloway & Zweigerhaft, Citation2010).

Birth order has also been associated with the hazardous aspects of risk-taking behavior. Research among participants in extreme sports shows that ordinal position in the family predicted perception of health-related risks (Krause et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, prior research has shown that younger siblings of children displaying risky behavior are at increased risk of displaying that behavior themselves (Argys, Rees, Averett, & Witoonchart, Citation2006). This association has been found for risky sexual behavior (Haurin & Mott, Citation1990), delinquent behavior (Fagan & Najman, Citation2003), and smoking and drug use (Low, Shortt, & Snyder, Citation2012). It is known that regular drinking by an older sibling is associated with a higher risk of regular drinking for the youngest sibling (Scholte, Poelen, Willemsen, Boomsma, & Engels, Citation2008). It is, however, unknown whether the presence of siblings and birth order also influences excessive alcohol consumption.

This study aims to explore the relationship between birth order and the characteristics of acute alcohol intoxication. First, the study determines whether the absence or presence of siblings is associated with acute alcohol intoxication. Second, the study examines whether the distribution of firstborn, middle, and youngest children in the group of admitted intoxicated adolescents with siblings differs from the expected distribution in the general Dutch population ages 12 to 17 years old with siblings. In other words, is birth order associated with acute alcohol intoxication among Dutch adolescents? Finally, this study aims to analyze whether birth order and the presence of siblings are associated with a higher BAC at admission, corrected for the known covariates of age, sex, and educational level (Van Hoof et al. 2018).

Method

Data collection procedure

Since 2007, the NSCK has been collecting data from Dutch adolescents admitted to a pediatric department of a Dutch hospital with a positive BAC. Pediatricians from Dutch hospitals have been asked to report admissions to the NSCK and subsequently complete a questionnaire containing questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics of the child admitted, current intoxication and treatment data, and past substance (ab)use. All the data are collected in a national database. For the current analysis, patients admitted primarily because of alcohol intoxication were selected. Patients without known sibling status as well as patients without known position in the family were excluded from analyses.

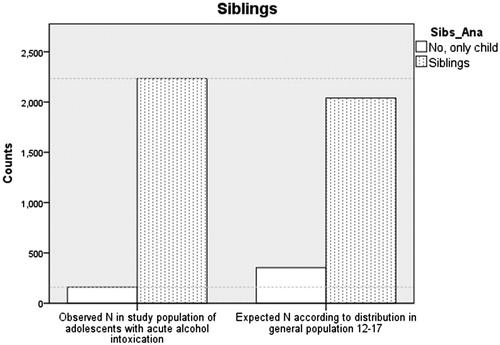

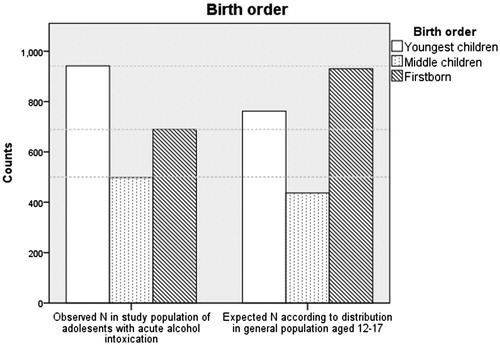

The study population was compared to the general population of Dutch adolescents 12 to 17 years old. Characteristics of this reference group were extracted from data collected by the Dutch Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS; 2017). CBS data were available from 2007 to 2016. The extracted data are displayed in and .

Table 1. Expected proportions birth order and sibling status Dutch population ages 12 to 17 (per Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics).

Table 2. Religious demographics Dutch population ages 15 to 18 (per Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics).

Measures

The questionnaire contained two questions that were crucial for the current research question. The first was a multiple-choice question in order to determine the presence of siblings: “Do you have siblings?” Answer A: yes, brothers. Answer B: yes, sisters. Answer C: yes, brothers and sisters. Answer D: no, I am only child. The second multiple-choice question determined birth order when siblings were present: “What is your position in the family?” Answer A: youngest. Answer B: oldest. Answer C: in between.

Additional data obtained by the questionnaire that were used for this study included general characteristics (age and sex), educational level (low, middle, high), religion (religiously unaffiliated, Christian, Muslim, other), and intoxication characteristics (blood alcohol content in gram/liter).

Participants

Between 2007 and 2017, a total of 6,416 underage adolescents were identified with a positive BAC during treatment in Dutch hospitals, and 77 of them were identified as recidivist alcohol-intoxicated adolescents. Of the 6,339 other cases, the question determining the presence of a sibling was answered in 2,394 cases (37.8%). Among adolescents with a sibling (N = 2,234), 2,129 (95.3%) answered the question regarding birth order.

Data analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 22. Frequencies are expressed as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous variables, such as age and BAC, are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD).

For the analyses, a new variable, presence of siblings, was created by pooling the answers brothers, sisters, and both brothers and sisters. Furthermore, statistics for missing years in the CBS data were estimated using the function replace missing values by linear trend at point. Weighted averages, with counts of study participants per year as weight, were used to determine expected frequencies of firstborn, middle, and youngest children. Using weighted averages also resulted in the correction of changes in the distribution of firstborn, middle, and youngest children over time. Throughout the past decade, the proportion of firstborn children remained stable (43%), but the proportion of middle and youngest children changed along with declining family sizes.

The aim of the first analysis was to compare the proportion of children without siblings in the study population to the proportion of children without siblings in the general Dutch population between 12 and 17 years. The chi-square goodness-of-fit test was used to determine how well the theoretical distribution (expected distribution extracted from CBS data) fits the empirical distribution found in the study population (Laerd Statistics, Citation2015).The significance level for this study was set to 5%.

The same statistical method was used for the second analysis of birth order. The distribution of birth order (firstborn, middle, and youngest child) in the study population was compared to the distribution in the general Dutch population ages 12 to 17 using Pearson’s chi-square goodness-of-fit test with a significance level p<.05. In the case of significant results, post hoc analysis was conducted to determine which categories deviate significantly from expected proportions. The post hoc analysis was performed using a chi-square test for each category versus the sum of the other categories. The Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons, resulting in a significance level of p equals 0.017 (three categories).

Finally, firstborn, middle, and youngest children were compared in terms of BAC, as well as only children versus children with siblings. Multivariable regression was used with BAC as an independent variable. The dependent variables used were birth order (using dummy variables) and known covariates (sex, age, and educational level). Univariate analyses were used to determine differences in sex distribution, age, and educational level among firstborn, middle, and youngest children. For nominal variables, chi-square tests were used, and for continuous variables, independent-samples t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Bonferroni was used.

Confounding factor: Religion

Religion should be considered a confounding factor, as it may influence both the exposure variable (position in the family) and the outcome variable (admissions due to acute alcohol intoxication) indirectly. Therefore, religious differentials may interfere in the association between birth order and acute alcohol intoxication.

Religious differentials have been associated with differences in fertility rates expressed as the average number of children per woman (Peri-Rotem, Citation2016). The fertility rate is the highest among Muslims (2.1), followed by Christians (1.6) and the religiously unaffiliated (1.4) (Hackett, Cooperman, & Ritchey, Citation2015). Therefore, religion is indirectly related to the proportion of adolescents being in the middle of the birth order. Religion might also influence the outcome variable indirectly, because religious norms regarding alcohol use vary among different religions. Therefore, religiously unaffiliated adolescents might be overrepresented in the study population.

Results

First, the results of the analysis on sibling status are presented. Second, the results of the analysis on birth order are discussed. Finally, the study population is compared to the general population in terms of religion.

Distribution of absence/presence of siblings

In the study population, 160 (6.7%) adolescents were only children and 2,234 adolescents (93.3%) had siblings. Given the national statistics of the past 10 years, the expected proportion of being an only child in the general population ages 12 to 17 was 14.7%. These percentages are displayed in .

The results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test are presented in . The test indicated that the proportion of adolescents who were only children was significantly lower in the study population than in the full Dutch adolescent population (X2(1, N = 2,394) = 124.60, p<.001).

Table 3. Chi-square goodness-of-fit sibling status.

The characteristics of acute alcohol intoxication are displayed in . An independent-sample t-test was conducted to compare average age between adolescents who had siblings and adolescents without siblings (p = 0.48). These results suggest that the presence of siblings is not associated with the average age at admittance. Chi-square tests indicated that both gender (p = 0.91) and distribution of educational level (p = 0.60) were equal among both groups. BAC was slightly higher among adolescents without siblings, but correction for known covariates (gender, age, and educational level) by multivariable regression analysis resulted in a non-significant association between BAC and sibling status (p = 0.09).

Table 4. Sibling status related to age, blood alcohol concentration gender, and educational level.

Distribution of birth order: Firstborn, middle, and youngest children

Of the 2,129 participants with siblings and known birth order, 689 (32.4%) were firstborn children, 498 (23.4%) were middle children, and 942 (44.2%) were youngest children. The expected proportions of firstborn, middle, and youngest children in the general Dutch adolescent population were derived from data of the Central Bureau of Statistics (). The expected distribution was 43.7% firstborn children, 20.6% middle children, and 35.8% youngest children. The expected distribution in the reference population and the observed distribution in the study population is displayed in .

The results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test are displayed in . The chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicated that the observed numbers of study participants who were firstborn, middle, and youngest children were significantly different from the expected numbers according to the proportions found in the general population (X2(2, N = 2,129) = 113.74, p<.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that firstborn children were significantly underrepresented in the study population compared to the general Dutch population ages 12 to 17. The middle and youngest children in the family were overrepresented in the study population compared to the general Dutch population ages 12 to 17.

Table 5. Chi-square goodness-of-fit birth order.

displays acute alcohol intoxication characteristics of firstborn, middle, and youngest children. Youngest children in the family were slightly younger (15.26 years) than firstborns (15.37 years), but one-way ANOVA indicated that average did was not significantly associated with birth order (p = 0.14). Chi-square test showed that the proportion of females was significantly higher in youngest children in the family than in middle children and firstborn children (p = 0.023). Educational level did not differ significantly between the groups (p = 0.08). Multivariate regression showed that BAC, corrected for age, gender, and educational level, was not significantly associated with birth order (p = 0.65–0.87).

Table 6. Family position related to age, blood alcohol concentration, gender, and educational level.

Confounding factors: Religion

As mentioned in the methodology section, religion should be considered a confounding factor. Therefore, the proportion of adolescents with a Dutch background in the study population of adolescents with acute alcohol intoxication was compared to the proportion of adolescents with a Dutch background in the general population of Dutch adolescents. For this analysis, the entire database was used.

In the general population of Dutch adolescents, 48.4% consider themselves religiously unaffiliated, 34.1% are Christian, and 8.6% are Muslim (). This distribution differs significantly from the study population of adolescents with acute alcohol intoxication (X2(3, N = 3997) = 269.9, p<.001). Religiously unaffiliated adolescents were overrepresented in the study population, and those who consider themselves to be Muslim or Christian were relatively underrepresented in the study population ().

Table 7. Chi-square goodness-of-fit religious distribution.

Discussion

This retrospective study expands on prior research on the effect of birth order on risky adolescent behavior by examining the relationship between birth order and admissions due to acute alcohol intoxication. Compared to the proportion in the general Dutch population of adolescents, the proportion of adolescents who were the oldest in the family is lower in the study population of adolescents with acute alcohol intoxication. This result is consistent with prior research on the association between birth order and risk-taking adolescent behavior as mentioned in the introduction.

Sex distribution was unequal among firstborn, middle, and youngest children admitted for acute alcohol intoxication. The proportion of girls was significantly higher among youngest children. This result suggests that girls might be more influenced by the presence of older siblings than boys are. This result is in line with prior research in which peer pressure was more positively associated with drinking in girls than in boys (Simons-Morton, Haynie, Crump, Eitel, & Saylor, Citation2001).

Although birth order had a significant effect on the number of admissions due to acute alcohol intoxication, the severity of intoxication measured by blood alcohol concentration did not differ significantly among firstborn, middle, and youngest children. Furthermore, age at admission did not differ among the groups. Youngest children in the family were not significantly younger than firstborns in case of admission. Similar results were seen in the analysis of sibling status. The proportion of adolescents who had siblings was significantly higher in the study population than in the general population. Differences in age and BAC were non-significant.

The results of this study should be considered in the context of certain limitations of the design. First, the presence of siblings and position in the family were known in approximately 40% of the cases. Missing data can be explained by the usage of various versions of the questionnaire. Questions about sibling status and position in the family were excluded in the online shortened version. Recall bias and response/nonresponse bias are unlikely, given the demographic nature of the questions. The low response rate can be compensated for by the strength of this study, which is the large number of patients included. The group was still sufficient in size to perform the analysis.

Second, this study did not examine the specific reasons why being an only child or being the firstborn child are protective factors. A possible explanation might be that firstborn children are raised more rigorously than their younger siblings. Prior research shows that certain parenting strategies, such as disapproval of adolescent drinking, general discipline, and rules about alcohol, result in delayed alcohol initiation and reduced levels of later drinking by adolescents (Ryan, Jorm, & Lubman, Citation2010). Hypothetically, being consistent in enforcing rules might be more difficult for younger siblings than for firstborn children. Furthermore, drinking by an older sibling (at legal age) can be imitated by younger siblings. Birth order is not significantly associated with blood alcohol concentration, because being a firstborn, middle, or younger child does not influence the exposure to social pressure from society to continue drinking once started.

The strength of this study is that religion as a possible confounding factor has been considered, as it may interfere with the association between birth order and acute alcohol intoxication. Certain factors, such as religion, influence family size and therefore the proportion of firstborn, middle, and youngest children. In the study population, religiously unaffiliated adolescents were overrepresented compared to the general Dutch population. Being religiously unaffiliated is associated with lower fertility rates, smaller families, and therefore a lower percentage of middle children. Instead, the results indicated that the percentage of middle children was higher in the study population than in the general Dutch adolescent population. Therefore, the association between birth order and acute alcohol intoxication might be underestimated in this study. Furthermore, relative underrepresentation of firstborn adolescents and overrepresentation of youngest children in the family cannot be explained by religion or other factors influencing family size and drinking norms.

Conclusion

Prior research indicated an association between birth order and risky behavior by adolescents. However, further research is needed to explore the relationship between birth order and admissions due to acute alcohol intoxication. This study shows that acute alcohol intoxication occurs more frequently in adolescents who have an older sibling. Therefore, being an only child or the firstborn child should be considered protective factors for acute alcohol intoxication. In contrast, middle and youngest children are at increased risk of acute alcohol intoxication.

Practical implications

Making parents aware of differences between their children and targeting preventive strategies to those most at risk for acute alcohol intoxication may lead to a reduction in hospital admissions due to acute alcohol intoxication. Special attention should be given to girls with older siblings, as they are more influenced by the presence of older siblings than boys are.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- Argys, L. M., Rees, D. I., Averett, S. L., & Witoonchart, B. (2006). Birth order and risky adolescent behaviour. Economic Inquiry, 44(2), 215–233.

- Baroncelli, L., Braschi, C., Spolidoro, M., Begenisic, T., Sale, A., & Maffei, L. (2010). Nurturing brain plasticity: Impact of environmental enrichment. Cell Death & Differentiation, 17(7), 1092–1093.

- Bouthoorn, S. A., Van der Ploeg, T., Van Erkel, N. E., & Van der Lely, N. (2011). Alcohol intoxication among Dutch adolescents: Acute medical complications in the years 2000 – 2010. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(3), 244–251.

- Burnett, S., Bault, N., Coricelli, G., & Blakemore, S. J. (2010). Adolescents’ heightened risk-seeking in a probabilistic gambling task. Cognitive Development, 25(2), 183–196.

- Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2016a). Huishoudens; kindertal, leeftijdsklasse kind, regio, 1 januari. Retrieved from http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=71487NED&D1=0-3&D2=4,9,12-15&D3=0&D4=6-15&VW=T

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2016b). Religieuze betrokkenheid; persoonskenmerken. Retrieved from http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=82904NED&D1=0,2-7&D2=3&D3=a&VW=T

- Dennis, E. L. (2012). Development of brain structural connectivity between ages 12 and 30: A 4-Tesla diffusion imaging study in 439 adolescents and adults. NeuroImage, 64, 671–684. doi. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.004

- Fagan, A. A., & Najman, J. M. (2003). Sibling influences on adolescent delinquent behaviour: An Australian longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 26(5), 564–558.

- Hackett, C., Cooperman, A., & Ritchey, K. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050, Why Muslims Are Rising Fastest and the Unaffiliated Are Shrinking as a Share of the World’s Population. PEW Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/europe/

- Haurin, R. J., & Mott, F. L. (1990). Adolescent sexual activity in the family context: The impact of older siblings. Demography, 27(4), 537–557.

- Irwin, C. E., Igra, V., Eyre, S., & Millstein, S. (1997). Risk-taking behavior in adolescents (The paradigm). Adolescent nutritional disorders prevention and treatment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 817(1 Adolescent Nu), 1.

- Krause, P., Heindl, J., Jung, A., Langguth, B., Hajak, G., & Sand, P. G. (2014). Risk attitudes and birth order. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(7), 858–868. doi. 10.1177/1359105313481075

- Laerd Statistics. (2015). Chi-square goodness-of-fit using SPS Statistics. Statistical tutorials and software guides. Retrieved from https://statistics.laerd.com/

- Low, L., Shortt, J. W., & Snyder, J. (2012). Sibling influences on adolescent substance use: The role of modeling, collusion, and conflict. Development and Psychopathology, 24(1), 281300. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000836

- Nienhuis, K. A., Van der Lely, N. A., & Van Hoof, J. J. B. (2017). Ten years of alcohol intoxication in adolescents and treatment in paediatric departments in Dutch Hospitals. Journal of Addiction Research, 1(1), 1–6.

- Peri-Rotem, N. (2016). Religion and fertility in Western Europe: Trends across cohorts in Britain, France and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population, 32(2), 231–265.

- Ryan, S. M., Jorm, A. F., & Lubman, D. I. (2010). Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(9), 774–783.

- Scholte, H. H., Poelen, A. P., Willemsen, B., Boomsma, D. I., & Engels, C. M. E. (2008). Relative risks of adolescent and young adult alcohol use: The role of drinking fathers, mothers, siblings, and friends. Addictive Behaviors, 33(1), 1–14.

- Simons-Morton, B., Haynie, D. L., Crump, A. D., Eitel, S. P., & Saylor, K. E. (2001). Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Education and Behavior, 28(1), 95–107. doi. 10.1177/109019810102800109.

- Sulloway, F. J. (1996). Born to Rebel: Birth order, family dynamics and creative lives. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18(5), 361–367. doi. 10.1016/S1090-5138(97)00032-9

- Sulloway, F. J., & Zweigerhaft, R. L. (2010). Birth order and risk taking in athletics: A meta-analysis and study of major league baseball. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(4), 402–416. doi. 10.1177/1088868310361241

- The Lancet Public Health. (2018). Addressing youth drinking. The Lancet Public Health, 3(2): e52. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30010-0.

- Van Hoof, J. J., Klerk, F. J., & Van der Lely, N. (2018). Acute alcohol intoxication: Differences in school levels and effects on educational performance. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 27(1), 42–46.

- Van Laar, M. W. (2016). Nationale Drug Monitor, Jaarbericht 2016. Utrecht, Den Haag. Trombos-instituut, Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en documentatiecentrum, Ministerie van Justitie en veiligheid. Retrieved from https://www.trimbos.nl/kerncijfers/nationale-drug-monitor/

- Van Zanten, E., Van der Ploeg, T., Van Hoof, J. J., & Van der Lely, N. (2013). Gender, age, and educational level attribute to blood alcohol concentration in hospitalized intoxicated adolescents: a cohort study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(7), 1188–1194.