?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this study, we examined the effects of complainant emotionality, presentation mode, and statement consistency on credibility judgments in an intimate partner abuse case. Male and female police trainees (N = 172) assessed the credibility of a domestic abuse complainant who appeared either live or on video, and behaved in an emotional (displaying sadness and distress) or a neutral manner. In addition, the consistency of the statement with other evidence was manipulated. Live (vs. video) and consistent (vs. inconsistent) statements were perceived as more credible, and the presentation mode effect was mediated by participants’ felt compassion and approach/avoidance tendencies toward the complainant. As predicted, emotional (vs. neutral) demeanor increased perceived credibility through its effect on expectancy confirmation, but this effect appears to have been masked by other mechanisms (compassion and approach/avoidance) operating in the opposite direction. These findings highlight the need to consider multiple, sometimes conflicting, mechanisms underlying extra-legal influences on credibility judgments. Legal implications are discussed.

March 25, 2007, 6:37 am: The Swedish Emergency Service receives a phone call from a woman who, crying and sobbing, struggles to describe what has happened and where she is. Again and again, she tries to bring herself together, but on each attempt she soon falls back into tears. The fact that this 19-year old woman was so emotional when making the phone call, immediately after she was allegedly drugged and brutally raped by two men, would later prove to be key evidence in the trial against the so-called ‘Stureplan profiles’ (the verdict of 16 October 2007 in Svea Court of Appeal, case B Citation3806-Citation07). It is a consistent finding that rape victims, who display negative emotions when disclosing the traumatic event, are more readily believed than victims behaving in a numbed or controlled manner (Ask & Landström, Citation2010; Kaufmann, Drevland, Wessel, Overskeid, & Magnussen, Citation2003; Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991). It is, however, not known whether this emotional victim effect (Ask & Landström, Citation2010) translates to adult victims of non-sexual crimes.

Yet another factor that may influence how crime victims are assessed is the presentation mode via which the victim is presented to observers. With rapid advances in criminal and courtroom technology, the use of video-recorded testimonies as evidence has become increasingly common. Research has consistently shown witnesses and victims testifying live are more positively evaluated, and rated as more credible, than those testifying on video (Landström, Ask, & Sommar, Citation2015; Landström, Granhag, & Hartwig, Citation2005, Citation2007). To date, however, the psychological mechanisms underlying this presentation mode effect (Landström et al., Citation2015) have not been adequately examined. In this study, we investigate the joint influence of presentation mode and emotional demeanor on credibility judgments of an intimate partner abuse complainant, and explore possible mediators of these effects. In addition, to put presentation mode and emotional demeanor in context, we examine how the effects of these extra-legal factors compare with the effect of a legally relevant factor – statement consistency.

Victim demeanor

In recent years, a growing number of experimental studies have shown that crime victims’ emotional display has a profound influence on their apparent credibility. This research has found consistent evidence for the emotional victim effect (EVE); adult victims who express strong negative emotions when talking about their victimization are perceived as more credible than victims who display little emotion or positive feelings (Ask & Landström, Citation2010; Bollingmo, Wessel, Eilertsen, & Magnussen, Citation2008; Bollingmo, Wessel, Sandvold, Eilertsen, & Magnussen, Citation2009; Golding, Fryman, Marsil, & Yozwiak, Citation2003; Hackett, Day, & Mohr, Citation2008; Kaufmann et al., Citation2003; Lens, van Doorn, Pemberton, & Bogaerts, Citation2014; Rose, Nadler, & Clark, Citation2006). This robust finding is problematic, given that there is considerable variation in how people respond to and cope with negative events (Krohne, Citation2003; Watson & Clark, Citation1984) and the fact that crime victims display a wide range of psychological reactions, ranging from mild to severe (Frieze, Hymer, & Greenberg, Citation1987). Hence, there appears to be no single emotional response that is telling of the type and severity of a criminal event. Moreover, victims may regulate their emotional expressions for self-presentational purposes (Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991), further underscoring the inappropriateness of using emotional expressiveness as a sign of credibility.

Most researchers have adopted a stereotype-based account to explain why the EVE occurs. That is, it has been assumed that people carry stereotypical expectations about what constitutes a ‘normal’ reaction to victimization, and that victims who do not display such a reaction are viewed as lacking in credibility (e.g. Calhoun, Cann, Selby, & Magee, Citation1981; Winkel & Koppelaar, Citation1991). Consistent with this assumption, Hackett et al. (Citation2008) showed that individuals with strong (vs. weak) expectations about emotional victim behaviors were more likely to exhibit the EVE. Moreover, Ask and Landström (Citation2010) found that perceived violation of expectations mediated the effect of victim demeanor on credibility judgments. The stereotype account represents a ‘cold’ cognitive approach because it assumes the mapping of prior expectations (i.e. stereotypes) onto incoming behavioral information (i.e. victim demeanor), without the involvement of motivational or affective elements.

In the first demonstration of this kind, Ask and Landström (Citation2010) showed that an emotional (vs. numbed) victim is judged as more credible not only because her demeanor better matched observers’ expectations, but also because it evoked stronger feelings of compassion. This ‘hot’ cognitive account thus suggests that the process of credibility judgment involves affective components. This notion resonates well with findings in lie-detection research, showing that people’s deception judgments are negatively correlated with the extent to which they have a generally positive impression (i.e. friendly, cooperative, pleasant) of the judgment target (Hartwig & Bond, Citation2011). Experimental evidence further corroborates the affective nature of credibility judgment. According to approach–avoidance accounts of self-regulation, positive and negative objects and persons automatically trigger approach or avoidance actions in observers (Cacioppo, Priester, & Berntson, Citation1993). Conversely, liking for concurrently perceived objects and persons change in a congruent manner depending on whether the observer is in an approach-related or avoidance-related body state (e.g. Cacioppo et al., Citation1993; Kawakami, Phills, Steele, & Dovidio, Citation2007) – a phenomenon that has been brought forward as an example of embodied cognition (e.g. Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric, Citation2005). Consistent with an affective account of credibility judgments, Ask and Reinhard (Citation2018) found that participants in an approach (vs. avoidance) state felt less negative feelings towards the target, and that this in turn led to more favorable judgments of the target’s credibility.

Just like sexual assault, intimate partner violence (IPV) is a prevalent worldwide problem (e.g. Kramer, Lorenzon, & Mueller, Citation2004). It occurs in all types of relationships, but it is often depicted, in accordance with traditional gender norms, as domestic violence committed by heterosexual men against their wives or girlfriends. Worldwide, no less than one in three women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner (WHO, Citation2013). IPV is a crime surrounded with feelings of guilt, shame and self-blame and approximately only about 20% of those offended report the crime to the police (e.g. BRÅ, Citation2009; Klein & Tobin, Citation2008; Tjaden & Thoennes, Citation2000). Of the offences reported to the police, about one third will be prosecuted and about half of these prosecutions will result in a conviction (see e.g. Garner & Maxwell, Citation2009). One reason why many cases fail to be prosecuted is the lack of objective (e.g. medical reports) and subjective (e.g. other witnesses; Belknap et al., Citation2000) evidence. Hence, assessing the credibility of a victim’s statement is of great importance for legal practitioners throughout the judicial system – from the initial judgments made by the police to judgments made by prosecutors and judges. In line with previous research on female rape victims (e.g. Ask & Landström, Citation2010), we predicted that the female IPV complainant would be perceived as more credible when behaving in an emotional manner (i.e. show signs of sadness and distress) than when behaving neutrally (Hypothesis 1a) and that affective (i.e. participants’ compassion with the complainant) and motivational (i.e. participants’ motivation to avoid and approach the complainant) components (Hypothesis 1b) as well as expectancy violation (Hypothesis 1c) would mediate this effect (Ask & Landström, Citation2010).

Presentation mode

The presentation mode effect (PME) means that witnesses and complainants that appear live (i.e. with the observers physically present) are more positively evaluated and perceived as more credible than targets that appear on video. The PME is robust for both adult (Landström et al., Citation2005, Citation2015) and child targets (Goodman et al., Citation1998, Citation2006; Landström & Granhag, Citation2010; Landström, Granhag, & Hartwig, Citation2007; Orcutt, Goodman, Tobey, Batterman-Faunce, & Thomas, Citation2001; Ross et al., Citation1994; Tobey, Goodman, Batterman-Faunce, Orcutt, & Sachsenmaier, Citation1995). The effect also generalizes to witnesses (Landström et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Landström & Granhag, Citation2010) and complainants (Goodman et al., Citation1998, Citation2006; Landström et al., Citation2015; Orcutt et al., Citation2001; Ross et al., Citation1994; Tobey et al., Citation1995), as well as to different events, like car accidents (Landström et al., Citation2005), interactions with a stranger (Landström et al., Citation2007; Landström & Granhag, Citation2010), inappropriate touching (Goodman et al., Citation1998, Citation2006; Orcutt et al., Citation2001; Tobey et al., Citation1995), and sexual (Ross et al., Citation1994) and physical (Landström et al., Citation2015) assault.

One frequently suggested explanation for the PME rests on the vividness effect (Bell & Loftus, Citation1985; Nisbett & Ross, Citation1980). In short, statements are considered vivid if they are detailed, emotionally interesting, concrete, imagery-provoking, and proximate in a sensory, temporal, or spatial way (Nisbett & Ross, Citation1980). That is, a statement is considered vivid not only due to the content of the statement it self (e.g. level of details) but due to the presentation of the statement (e.g. level of proximity). Vivid statements are better remembered, attract more attention and are perceived as more credible than pallid statements (Bell & Loftus, Citation1985). Vivid statements are also more difficult for jurors to disregard when deemed inadmissible as evidence (Edwards & Bryan, Citation1997). According to this view, as live in-court testimonies are both spatially and temporally more proximate than pre-recorded video testimonies, they can also be considered more vivid. Previous research has found that live statements are better remembered (Landström et al., Citation2007), attract more attention and are perceived as more credible (e.g. Landström et al., Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2015). On a general level, the vividness effect appears to account for the demonstrated PME.

In this article, we examine affective (Ask & Landström, Citation2010) and motivational mediators of the effects of PME. Given the demonstrated role of approach and avoidance motivations in credibility judgments (Ask & Reinhard, Citation2018), we propose that statements presented live (vs. on video) are considered more credible because observers are more strongly motivated to approach, and less inclined to avoid, a witness who appears in their physical proximity. Previous research in social psychology has shown that actual or perceived proximity increases interpersonal attraction and the motivation to approach a social target (e.g. Kahn & McGaughey, Citation1977). In the present study we predicted in line with previous research (e.g. Landström et al., Citation2005), that the complainant would be judged as more believable when she appeared live, compared to via video (Hypothesis 2a). We also made the novel proposition that affective (i.e. participants’ compassion with the complainant) and motivational (i.e. participants’ motivation to avoid and approach the complainant) components would mediate this effect (Hypothesis 2b). Possible interaction effects between presentation mode and victims’ displayed emotions have not been explored extensively in previous research (but see Heath, Grannemann, & Peacock, Citation2004, Exp. 1, for a study on the interaction between defendant emotions and presentation mode). A few year ago, Landström et al. (Citation2015) studied the effects of presentation mode (live vs. video) and emotional demeanor with a male assault complainant, and found that presentation mode, but not emotional display, influenced observers’ credibility judgments; the complainant was perceived as more credible when testifying live than on video. The authors, therefore, raised doubt as to the generalizability of the EVE as it may not be applicable to all types of crimes and all types of victims. The present study seeks to study this potentially limited generalizability of the EVE, by examining possible effects of emotional display on credibility judgments of a female victim of IPV.

Statement consistency

In real-life criminal cases, credibility judgments are determined jointly by extra-legal and legally relevant factors (see Landström, Willén, & Bylander, Citation2012). However, previous research on the effects of displayed emotion and presentation mode has ignored the extent to which participants use legally relevant information as a basis for their judgments. To evaluate how the influence of extra-legal factors operates in the presence of legally relevant information, it is necessary to combine both within a single study. We therefore included statement consistency as a third factor in our experimental design.

Real-life statements tend to vary in statement consistency. That is, the extent to which a person changes his or her statements over time by adding or omitting certain details. Consistency is sometimes described as one of the hallmarks of an accurate statement (Granhag & Vrij, Citation2005) and lay-judges as well as legal practitioners are often informed to pay attention to consistency when making judgments (e.g. New York State Committee on Criminal Jury Instructions, Citation2004; NJA, Citation2010). Indeed, within-witness consistency has been found to be the most frequently used cue for making judgment of whether or not a statement is true or false (Fisher, Brewer, & Mitchell, Citation2009; Granhag & Strömwall, Citation2000). Nevertheless, consistency is not a highly diagnostic cue to discriminate between truth and deception. Previous research has shown that a person who is telling the truth tends to alter his/her story just as much as a person who is lying (Strömwall, Granhag, & Jonsson, Citation2003). In addition, omitting details as well as adding details over time is consistent with the characteristics of the normal functioning of human memory. More specifically, omissions in a second interview could very well be the result of memory decline (Ebbinghaus, Citation1885/1913; Rubin & Wenzel, Citation1996), and added details in the second interview could very well be the result of reminiscence caused by repeated interviewing (Gilbert & Fisher, Citation2006). In light of research within this field (summarized in Granhag, Strömwall & Landström, Citation2017), the Swedish Supreme Court recently issued a precedent stating that within-witness consistency should no longer be viewed as a valid criteria of statement credibility (NJA, Citation2017).

Previous research has shown that variations in consistency tend to affect the perceived credibility of the witness (Berman, Narby, & Cutler, Citation1995; Desmarais, Citation2009; Pozzulo & Dempsey, Citation2009). In line with these previous findings, we predicted that the complainant would be perceived as more credible when her statement was consistent with the background information, than when it was inconsistent (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Participants and design

One hundred and seventy-two students (104 men, 68 women) at a Swedish Police Academy, with ages ranging from 19 to 38 years (M = 26.07, SD = 3.77), participated in the study. We recruited participants at a Police Academy, rather than from a general student or community population, due to their criminal and legal training and familiarity with the concept of assessing credibility of alleged victims. At the police academy, the students are all educated and trained in deception detection and credibility assessments. The recruited participants were at various stages in their police training and it is possible that some participants were more educated in this field than others. However, preliminary analyses showed that the dependent measures (see below) did not differ significantly as a function of which semester the participant were currently in (p > .05). Participants were randomly assigned to one of eight conditions defined by a 2 (complainant demeanor: emotional vs. neutral) × 2 (presentation mode: live vs. video) × 2 (statement consistency: consistent vs. inconsistent) factorial design. The number of participants in each cell of the design varied between 17 and 26. Participants received a movie ticket (approximately € 12) in exchange for their participation. The collected sample size rendered 80% power, using single-degree-of-freedom tests (applicable to our predicted main effects of complainant demeanor, presentation mode, and statement consistency), to detect effects with a size of r = .21 (i.e. small effects according to the conventions proposed by Cohen, Citation1988). While a larger sample would have been desirable for acceptable power to detect any two-way or three-way interaction effects (which tend to be quite small), the current sample size was the maximal amount of participants we could access given the uniqueness of the population (police students).

Procedure and materials

Participants attended the experimental sessions in a lecture hall in groups of about 20 persons. Upon arrival, they received verbal instructions that they were to watch a statement from a female IPV complainant, and later to answer questions about their perception of the statement and the complainant.

Background information

Before watching the statement, participants were given written background information (on paper), stating that the complainant had made a report to the police one week after the alleged abuse had taken place. The participants were informed that the complainant had agreed to volunteer in a research study about the psychological aspects of evidence evaluation. To avoid suspicion regarding the authenticity of the case, the assault complaint was accompanied during the experimental sessions by an alleged witness support person.Footnote1 The background information also contained a brief summary of the first police interview with the complainant, and a summary of the suspect’s statement to the police. The suspect (the complainant’s boyfriend) denied having assaulted the complainant, claiming instead that he had had an argument with the complainant and had left the apartment because he felt the argument was pointless. Finally, participants were told that the charges against the suspect had been dropped due to lack of evidence.

The background information was manipulated to be consistent or inconsistent with the complainant’s subsequent statement (see below). Specifically, three details reported by the complainant in the first police interview were manipulated: the time of the offence, the place where it happened, and the type of violence that had been used. In the consistent version, the complainant had reported (a) that she and the suspect had come home at 1 am, (b) that the assault had taken place in the hall, and (c) that the suspect had hit her several times in the face. In the inconsistent version, the complainant had reported (a) that she and the suspect had come home at 10 pm, (b) that the assault had taken place in the bedroom, and (c) that the suspect had taken a stranglehold on her for about half a minute. All participants were asked to read the background carefully at their own pace. Subsequently, the experimenter collected the background information and presented the complainant’s statement to the participants.

Complainant statement

A 29-year-old semi-professional actress, unknown to the general public, played the role of the complainant. The statement was presented to participants either live or on videotape. The videotaped statement was filmed from a distance of approximately 2 m (6.5 ft.), and the image was composed so that the upper body and face of the complainant, who was sitting behind a table, were visible from the front. The background in the recording was arranged to resemble, as closely as possible, the lecture hall where participants in the live condition watched the statement. The complainant’s demeanor was manipulated by instructing the actor to perform the statement with two different emotional expressions. In the emotional version, the complainant cried, looked down, and hesitated when disclosing delicate details from the event. In the neutral version, the complainant related the event in a factual manner, spoke with a steady voice, and showed little sign of emotions (cf. Ask & Landström, Citation2010). For logistical reasons, we were not able to present the very same statements live and on video. To decrease possible effects of this limitation, we selected an experienced actress that rehearsed the statement extensively to ensure equivalence of the live and video versions. To make sure that the statements would be perceived as realistic, the final versions of the actress’ statements (emotional and neutral) were selected by the principal researchers after careful deliberation. To decrease possible effects of this limitation further, we showed three different emotional (2 live and 1 videotaped) and three different neutral (2 live and 1 videotaped) versions of the complainant’s statement to large groups of 20–22 participants at the time. The verbal content of the statement was identical in all versions, and was congruent with the details provided in the consistent version of the background information (see above). In short, the complainant reported that she and the suspect had attended a party where she spoke to her ex-boyfriend. When she and the suspect had arrived home after the party, he accused her of having an affair. He then grabbed her by the arm, slapped her in the face, and pushed her. While she was lying on the floor, he hit her several times in the face and then left the apartment. The complainant had put her bloodstained clothes in the washing machine, and then gone to bed. Just like the majority of intimate physical assault victims, the complainant had a hard time deciding whether or not to tell anyone about the assault (Tjaden & Thoennes, Citation2000). However, one week after the attack the complainant told a friend what had happened, and encouraged by the friend she decided to report the assault to the police. To ensure perceived realism, the script for the verbal statement was created in collaboration with a real-life female assault victim.

Dependent measures

Immediately after having watched the complainant’s statement, participants rated the extent to which the complainant seemed to experience each of three negative emotions (discomfort, agitation, sadness; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much). These ratings were averaged into a composite index (Cronbach’s α = .81) used to test the effectiveness of the complainant demeanor manipulation.

Next, participants indicated whether or not they believed that the complainant had in fact been abused (yes/no) and rated their confidence in that judgment using a six-point scale ranging from 50% (completely unsure) to 100% (completely sure) with 10% increments. The dichotomous judgment and the confidence rating were combined into a measure of certainty: For participants who believed that the complainant had been abused, the original confidence rating was retained as the certainty measure. For participants who believed that the complainant had not been abused, the certainty measure was obtained by subtracting the original confidence estimate from 100%. Participants also rated the credibility of the complainant on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all credible, 7 = very credible). As intended, the measure of certainty and the credibility rating were strongly correlated, r = .70, p < .001; hence, the measures were transformed into z scores and averaged to form a veracity index variable.Footnote2

As a measure of expectancy violation, participants were asked to assess to what extent the woman’s behavior during the interview matched the behavior that they would expect from a rape victim (1 = did not match at all, 7 = matched completely). Because high ratings indicate confirmation rather than violation of expectancies, we will refer to this variable as expectancy confirmation. In addition, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they felt compassion with the complainant (1 = no compassion at all, 7 = very strong compassion). As measures of approach and avoidance motivations towards the complainant, participants rated to what extent the complainant seemed to be a person they would like to get to know, and a person they would try to avoid, respectively (1 = not at all, 7 = very much).

Finally, as a manipulation check for statement consistency, participants rated the extent to which the complainant contradicted the information she had previously reported in the police interview (described in the background information), and the degree to which she had changed her statement from the police interview. Both ratings were made on seven-point scales (1 = not at all, 7 = very much) and were averaged to form a composite measure of perceived consistency (r = .87).

Preliminary analyses showed that the dependent measures did not differ significantly as a function of participant gender (p > .05). The ratings from all participants are, hence, treated jointly in all the following analyses.

Results

The main analyses were conducted using 2 (complainant demeanor: emotional vs. neutral) × 2 (presentation mode: live vs. video) × 2 (statement consistency: consistent vs. inconsistent) between-participants analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Manipulation checks

To test the effectiveness of the complainant demeanor manipulation, participants’ ratings of complainant emotions were examined. As intended, there was a significant main effect of complainant demeanor, F(1, 164) = 58.04, p < .001, , 90% CI [.165, .339]; the complainant was perceived to experience significantly more negative feelings in the emotional condition (M = 5.59, SD = 0.87) than in the neutral condition (M = 4.23, SD = 1.38). The manipulation of complainant demeanor was, hence, successful. Unexpectedly, there was a significant effect of presentation mode, F(1, 164) = 14.69, p < .001,

, 90% CI [.026, .150], and a significant Complainant Emotion × Presentation Mode interaction, F(1, 164) = 9.23, p = .003,

, 90% CI [.010, .114]. Importantly, however, tests of simple effects revealed that the effect of complainant demeanor was significant both in the live (Memotional = 5.69, SD = 0.84 vs. Mneutral = 4.86, SD = 1.37) and in the video (Memotional = 5.52, SD = 0.90 vs. Mneutral = 3.75, SD = 1.19) conditions, both ps < .001. No other main or interaction effects were significant.

A similar analysis was performed to test the effectiveness of the consistency manipulation. Participants who watched an inconsistent statement (M = 5.02, SD = 1.35) perceived more contradictions in the complainant’s statement than did participants who watched a consistent statement (M = 2.92, SD = 1.17), F(1, 164) = 115.23, p < .001, , 90% CI [.311, .481]. Hence, the manipulation of statement consistency was successful. No other main or interaction effects were significant.

Veracity judgments

Participants’ mean ratings of statement veracity are presented in . Failing to support Hypothesis 1a, the main effect of complainant demeanor was not significant, F(1, 164) = 0.32, p = .573, , 90% CI [.000, .027]. In support of Hypothesis 2a, however, there was a significant main effect of presentation mode, F(1, 164) = 7.21, p = .008,

, 90% CI [.006, .099]. As predicted, participants who watched the statement live (Mz = 0.21, SD = 0.81) perceived the complainant as more truthful than did those who watched the statement on video (Mz = −0.17, SD = 0.98).

Table 1. Mean veracity judgments (and standard deviations) as a function of presentation mode, complainant demeanor, and statement consistency.

Moreover, the main effect statement consistency was significant, F(1, 164) = 4.44, p = .037, , 90% CI [.001, .076]. Supporting Hypothesis 3, participants who watched a consistent version of the statement rated the complainant as more truthful (Mz = 0.14, SD = 0.86) than did those who watched an inconsistent version (Mz = −0.14, SD = 0.97). None of the interaction effects was significant. Of particular note, the Complainant Demeanor × Presentation Mode interaction, which was significant for ratings of complainant emotions (see Manipulation Checks above), was virtually absent for veracity judgments, F(1,164) = 0.02, p = .888,

< .001, 90% CI [.000, .009].

Mediation analyses

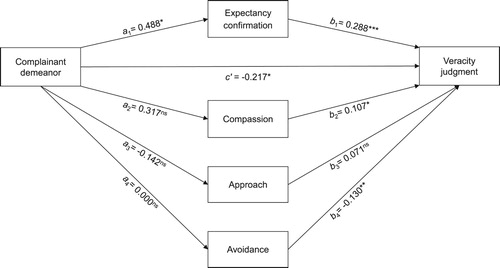

We had predicted that the effect of complainant demeanor on participants’ veracity judgments would be mediated by affective and motivational components (Hypothesis 1b) as well as by expectancy violation (Hypothesis 1c). The previous analysis suggested that demeanor did not influence veracity judgments, but we proceeded with the mediation analysis because it might provide clues as to why the null finding occurred. As argued by several scholars (e.g. Hayes, Citation2009; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, Citation2000; Shrout & Bolger, Citation2002; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, Citation2010), and as demonstrated by Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, and Petty (Citation2011), indirect effects (mediation) may exist even when there is not a zero-order relationship between the independent and the dependent variable (e.g. when a third variable suppresses the relationship). As can be seen in , demeanor did in fact seem to indirectly influence participants’ veracity judgments through its effect on expectancy confirmation. The emotional complainant was considered to behave more in line with expectations than a neutral complainant (a1 = 0.488, p = .025), and participants who considered the complainant to behave more in line with expectations judged the victim as more truthful (b1 = 0.288, p < .001). A 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (BCa), based on 5,000 resamples, for the indirect effect via expectancy confirmation (a1 b1 = 0.141) did not include zero (0.021, 0.285), indicating statistical significance. There was no evidence of indirect effects via approach tendencies, avoidance tendencies, or experienced compassion. Moreover, when controlling for the proposed mediators, a direct effect of demeanor on veracity judgments emerged, but in the opposite direction to the prediction of Hypothesis 1a (c’ = −0.217, 95% BCa [−0.428, −0.007]); the emotional complainant was considered to be less truthful than the neutral complainant. This indicates that while expectancy confirmation seems to carry a positive influence of emotional demeanor on veracity judgments, other forces exert an influence in the opposite direction.Footnote3

Figure 1. The effect of complainant demeanor on veracity judgments mediated by expectancy confirmation compassion, approach and avoidance. Numbers represent unstandardized regression coefficients. *p < .05. **p < .01 ***p < .001.

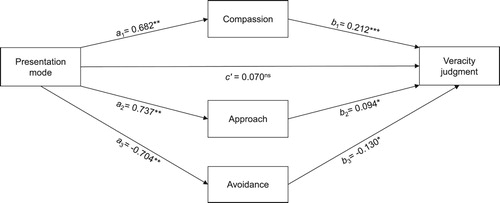

A second mediation analysis was conducted to test if the effect of presentation mode on veracity judgments would be mediated by affective and motivational components (Hypothesis 2b). As can be seen in , the results were consistent with mediation through all three proposed mediators. Live (vs. video) observers felt more compassion, were more inclined to approach, and were less inclined to avoid the complainant (a-paths). Compassion and approach tendencies were, in turn, positively related to rated veracity, and avoidance tendencies negatively related to rated veracity (b-paths), yielding significant indirect effects of presentation format via compassion (a1 b1 = 0.145, 95% BCa [0.054, 0.297]), approach tendencies (a2 b2 = 0.069, 95% BCa [0.008, 0.176]), and avoidance tendencies (a3 b3 = 0.092, 95% BCa = 0.019, 0.216). There was no evidence that presentation mode influenced veracity judgments independent of its influence on the mediators (c’ = .070, 95% BCa [−0.176, 0.316]). Participants’ mean ratings of the dependent measures are presented in .

Figure 2. The effect of presentation mode on veracity judgments mediated by felt compassion, approach and avoidance. Numbers represent unstandardized regression coefficients. *p < .05. **p < .01 ***p < .001.

Table 2. Mean ratings (and standard deviations) of dependent measures as a function of presentation mode, complainant demeanor, and statement consistency.

Discussion

Our experiment did not replicate the EVE as it has been observed in previous studies; veracity ratings for participants who watched the emotional complainant were not higher than for those who watched the neutral complainant. A closer examination of the data revealed that this null finding may be the result of opposing forces canceling each other out. On one hand, the data were consistent with the notion that expectancy violation mediates the EVE; the emotional (vs. neutral) complainant behaved more in line with observers’ expectations, which in turn was associated with higher veracity judgments. On the other hand, the residual effect of the complainant’s demeanor, after controlling for expectancy confirmation, was in the opposite direction to that expected; observers perceived the emotional complainant’s statement as less credible than the neutral complainant’s statement. Speculatively, this counterintuitive effect has to do with the affective and motivational variables that were expected, but failed, to mediate the EVE. The emotional (vs. neutral) complainant failed to evoke stronger compassion and approach tendencies, or weaker avoidance tendencies, among observers. This may have triggered skepticism among those watching the emotional complainant (i.e. ‘I should feel compassion for this crying woman, but I don’t’), which made them less inclined to believe what she was saying.Footnote4 Previous studies have found that, when emotional victims do succeed in eliciting compassion, it works to their advantage (Ask & Landström, Citation2010; Landström et al., Citation2015). Our findings suggest that cognitive (i.e. expectancy confirmation) and motivational/affective (i.e. compassion, approach/avoidance) mechanisms, while typically working in tandem, may sometimes exert different influences on observers’ judgments.

Consistent with previous studies (e.g. Landström et al., Citation2005, Citation2015) we found support for the predicted PME: live statements were perceived as more credible than videotaped statements. By replicating previous studies (e.g. Landström et al., Citation2015), with a target previously unexplored (a female assault victim), the present study adds to the robustness and the generalizability of the effect. The use of video recorded interviews in criminal and legal procedures is becoming increasingly common. Legislature in several countries now require or recommend the use of video recorded interviews as evidence in court (Landström et al., Citation2012; Sullivan, Citation2010), and research examining the mechanisms underlying the effects of presentation mode on perceived credibility is becoming increasingly relevant. In Sweden, all testimonies in the appellate courts consist of videotaped recordings of the testimonies given in lower courts (Swedish Ministry of Justice, Citation2004) and the defendant is typically the only party present in the courtroom during appellate hearings. The results indicate, once again, that witnesses and victims testifying via video are at a disadvantage compared to those testifying live.

In the present study, we took previous research one step further by providing evidence consistent with the notion that presentation mode influences credibility assessments through motivational (approach and avoidance) and affective (compassion) components. This has important implications for understanding credibility judgments made in legal settings. It has previously been assumed that live statements are more vivid and therefore considered more credible (Landström, Citation2008). This study suggests that the PME may also be due to the fact that live presentations evoke more compassionate responses. Consistent with previous research on the vividness effect (Bell & Loftus, Citation1985; Nisbett & Ross, Citation1980), it seems plausible that temporally and spatially proximate information also has a stronger potential to evoke compassion. Furthermore, the present study suggests that the PME rests on two motivational mechanisms – approach and avoidance tendencies. In everyday settings, people process social stimuli spontaneously and quickly, primarily to determine the social ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’ of others, and thus whether a target is to be approached or avoided (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, Citation2008; Scholer & Higgins, Citation2008; Wojciszke, Bazinska, & Jaworski, Citation1998). The present study showed that this fundamental process may be at work also in legal settings, and can account for how an extra-legal factor like presentation mode influence veracity assessments. The present study, hence, adds to the theoretical framework of the PME, by suggesting that it is mediated by both affective and motivational components. As always when interpreting statistical mediation analyses, however, one must keep in mind that the results are at best consistent with a proposed mechanism (as opposed to proving it), because they rest on correlations between variables rather than actual causal paths (Fiedler, Schott, & Meiser, Citation2011).

Our findings raise concern with regard to legal certainty. Research has found that people in an approach-related (vs. avoidance-related) state judge others as more honest, credible, and truthful (Ask & Reinhard, Citation2018). Moreover, persons who make a positive general impression (i.e. friendly, cooperative, pleasant) tend to be perceived as more truthful and credible than persons perceived less positively (Hartwig & Bond, Citation2011). If the positivity of people’s impression of a target is determined by some extra-legal factor like presentation mode, however, it is likely to reduce the accuracy of their veracity judgments.

Our findings regarding mediating processes can be helpful in informing policy measures to prevent the occurrence of the PME and EVE in criminal and legal settings. Affective and motivational mechanisms like those demonstrated here are unlikely to be under an individual’s conscious control, as they largely rest on automatic mental processes (Moors & De Houwer, Citation2006). Hence, educational measures that serve to increase awareness of the existence of the PME and EVE may not be effective at controlling the spontaneous psychological reactions that underlie these phenomena. In fact, instructions to disregard emotional information may paradoxically intensify the information’s influence on subsequent judgments (Edwards & Bryan, Citation1997). Awareness of these mechanisms should, however, make it possible to deliberately adjust for their influence ex post facto, in the same way as it is possible to retroactively correct for automatically activated stereotypes (Lepore & Brown, Citation2002), trait inferences (Uleman, Adil Saribay, & Gonzalez, Citation2008), and mood effects (Berkowitz, Jaffee, Jo, & Troccoli, Citation2000). It should be noted, though, that engaging in such correction introduces another potential source of bias, as the risk of under- or overcompensation is considerable (Wegener & Petty, Citation1997).

More cognitively oriented mechanisms (e.g. expectancy violation), in contrast, may be possible to regulate by means of instruction and deliberate control. There is some preliminary support for this possibility from research on the EVE. Bollingmo et al. (Citation2009) found that when observers were informed that their credibility assessments may be influenced by a victim’s emotional expression, and that emotional expression is not indicative of actual veracity, the EVE was greatly reduced. Moreover, Ask and Landström (Citation2010) found that police trainees displayed the EVE only when their cognitive resources were taxed while watching the victim’s statement, indicating that the effect can be counteracted given sufficient capacity for deliberate thinking.

In line with previous research (e.g. Desmarais, Citation2009; Pozzulo & Dempsey, Citation2009), the present study showed that statement inconsistency had a negative effect on rated veracity. This effect was present when tested in a model that also included extra-legal influences from emotional demeanor and presentation mode. However, our rather strong manipulation of consistency (i.e. presence or absence of three obvious contradictions; supported by a very large effect on perceived contradictions, ) created an effect on veracity judgments smaller than that of presentation mode. It, thus, appears that even when information considered diagnostic by legal decision makers (i.e. consistency) is available, there is substantial room for non-diagnostic information (i.e. presentation mode) to influence veracity judgments. Many real criminal cases resemble the fictitious scenario used in the present study: the complainant and the defendant provide conflicting accounts of the event, and, in the absence of much additional evidence, the court must base its verdict primarily on statement evidence. While statement consistency may be a rather unreliable indicator of veracity – true accounts may actually contain more inconsistencies than false ones (Gilbert & Fisher, Citation2006; Strömwall et al., Citation2003) – legal professionals often consider it to be a valid diagnostic cue (Fisher et al., Citation2009). Hence, we believe that the effect size associated with statement consistency provides a relevant reference against which the effects of extra-legal factors can be gauged.

Limitations

Before arriving at our conclusions, a couple of limitations should be considered. First, for logistical reasons, we were unable to present participants in the video conditions with the exact same statements as used in the live conditions. Instead, separate video versions had to be prepared beforehand. While considerable effort was put into ensuring that the live and video versions featured identical verbal content and nonverbal expressions, one might still argue that subtle differences in the performance of the statements may have caused the observed effect of presentation mode. We find it unlikely, however, that such unintended differences would have created an effect that was larger than that of the intentionally manipulated statement inconsistency. Moreover, as unintended differences in performance should be randomly distributed, they should not create consistent differences across all four live-video comparisons. Second, participants in this study were neither professional judges nor naïve jurors. Due to their basic legal training, in combination with their lack of professional experience, our sample of police trainees fall somewhere between the groups of decision makers occurring naturally in criminal and legal procedures. We therefore recommend some caution when inferring the real-life applicability of the current findings. Third, the sample size was smaller than optimal given the factorial nature of the experiment. Given the uniqueness of the population (police students), we were simply unable to access a larger sample for practical reasons. There was presumably limited power to detect any two- and three-way interactions had such existed, although this was not the purpose of the current research. The absence of interactions in the current findings should, thus, not be taken as an indication that the factors studied here do not produce interactive effects in the real world. It is important to note, however, that the experiment was adequately powered to detect even small effects with regard to our predicted main effects. Hence, our failure to replicate the EVE cannot be attributed to the lack of statistical power.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated the need to take the underlying mechanisms into consideration to understand extra-legal influences on veracity assessments. Such assessments involve a rich process that includes the interplay between observers’ cognitive, motivational, and affective reactions to the victim. Our findings suggest that veracity judgments are largely the result of how observers affectively and motivationally respond to the target. The results, which have both practical and theoretical implications, underline the need for further research examining the joint influence of legal and extra-legal factors on veracity judgments of crime victims.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Anna Larsson, who acted as complainant in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Sara Landström http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4894-2780

Karl Ask http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5093-5902

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The task of a witness support person is to help witnesses and injured parties, and to offer support and security during criminal proceedings, before and after court hearings.

2 Because participants rated complainant emotion prior to rating credibility, there is a possibility that the latter ratings were influenced by the former. In a recent study by Wrede, Ask, Strömwall, and Styvén (Citation2018), however, it was found that credibility judgments did not differ depending on whether they were made before or after emotion ratings (d = 0.16, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.45]).

3 Separate single-mediator models were run for each of the proposed mediators, confirming that only when controlling for expectancy confirmation did a significant negative direct effect of complainant demeanor on veracity judgments emerge.

4 It is important to note that this interpretation would predict non-existent rather than reversed indirect effects via compassion, approach, and avoidance; if complainant demeanor fails to affect those variables, they cannot logically carry indirect effects. Hence, the interpretation is entirely consistent with our data.

References

- Ask, K., & Landström, S. (2010). Why emotions matter: Expectancy violation and affective response mediate the emotional victim effect. Law and Human Behavior, 34, 392–401. doi: 10.1007/s10979-009-9208-6

- Ask, K., & Reinhard, M. A. (2018). Are lie judgments inherently evaluative? Embodied components in credibility attribution. Unpublished manuscript.

- Belknap, J., Graham, D. L. R., Hartman, J., Lippen, V., Allen, P. G., & Sutherland, J. (2000). Factors related to domestic violence court dispositions in a large urban area: The role of victim/witness reluctance and other variables. Executive summary. NCJ 184112. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

- Bell, B. E., & Loftus, E. (1985). Vivid persuasion in the courtroom. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 659–664. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4906_16

- Berkowitz, L., Jaffee, S., Jo, F., & Troccoli, B. T. (2000). On the correction of feeling-induced judgmental biases. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition (pp. 131–152). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Berman, G. L., Narby, D. J., & Cutler, B. L. (1995). Effects of inconsistent eyewitness statements on mock-jurors evaluations of the eyewitness, perceptions of defendant culpability and verdicts. Law and Human Behavior, 19, 79–88. doi:10.1007/BF01499074. doi: 10.1007/BF01499074

- Bollingmo, G., Wessel, E., Eilertsen, D. E., & Magnussen, S. (2008). Credibility of the emotional witness: A study of ratings by police investigators. Psychology, Crime & Law, 14, 29–40. doi: 10.1080/10683160701368412

- Bollingmo, G., Wessel, E., Sandvold, Y., Eilertsen, D. E., & Magnussen, S. (2009). The effect of biased and non-biased information on judgments of witness credibility. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15, 61–71. doi: 10.1080/10683160802131107

- BRÅ. (2009). Våld mot män och kvinnor i nära relationer: Våldets karaktär och offrens erfarenheter av kontakter med rättsväsendet [Violence against men and women in intimate relationships: Violence character and experiences of victims of contacts with the justice system]. Stockholm: Brottsförebyggande rådet.

- Cacioppo, J. T., Priester, J. R., & Berntson, G. G. (1993). Rudimentary determinants of attitudes: Ii. Arm flexion and extension have differential effects on attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 5–17. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.1.5

- Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., Selby, J. W., & Magee, D. L. (1981). Victim emotional response: Effects on social reaction to victims of rape. British Journal of Social Psychology, 20, 17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1981.tb00468.x

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 40, pp. 61–149). New York: Academic Press.

- Desmarais, S. L. (2009). Examining report content and social categorization to understand consistency effects on credibility. Law and Human Behavior, 33, 470–480. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9165-5

- Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Edwards, K., & Bryan, T. S. (1997). Judgmental biases produced by instructions to disregard: The (paradoxical) case of emotional information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 849–864. doi: 10.1177/0146167297238006

- Fiedler, K., Schott, M., & Meiser, T. (2011). What mediation analysis can (not) do. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.007

- Fisher, R. P., Brewer, N., & Mitchell, G. (2009). The relation between consistency and accuracy of eyewitness testimony: Legal versus cognitive explanations. In T. Williamson, R. Bull, & T. Valentine (Eds.), Handbook of psychology of investigative interviewing: Current developments and future directions (pp. 121–136). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Frieze, I. H., Hymer, S., & Greenberg, M. S. (1987). Describing the crime victim: Psychological reactions to victimization. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18, 299–315. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.18.4.299

- Garner, J. H., & Maxwell, C. D. (2009). Prosecution and conviction rates for intimate partner violence. Criminal Justice Review, 34, 44–79. doi: 10.1177/0734016808324231

- Gilbert, J. A. E., & Fisher, R. P. (2006). The effects of varied retrieval cues on reminiscence in eyewitness memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 723–739. doi: 10.1002/acp.1232

- Golding, J. M., Fryman, H. M., Marsil, D. F., & Yozwiak, J. A. (2003). Big girls don’t cry: The effect of child witness demeanor on juror decisions in a child sexual abuse trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1311–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.03.001

- Goodman, G. S., Myers, J. E. B., Qin, J., Quas, J. A., Castelli, P., Redlich, A. D., & Rogers, L. (2006). Hearsay versus children’s testimony: Effects of truthful and deceptive statements on jurors’ decisions. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 363–401. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9009-0

- Goodman, G. S., Tobey, A., Batterman-Faunce, J., Orcutt, H., Thomas, S., Shapiro, C., & Sachsenmaier, T. (1998). Face-to-face confrontation: Effects of closed-circuit technology on children’s eyewitness testimony and jurors’ decisions. Law and Human Behavior, 22, 165–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1025742119977

- Granhag, P. A., & Strömwall, L. A. (2000). Effects of preconceptions on deception detection and new answers to why lie-catchers often fail. Psychology, Crime & Law, 6, 197–218. doi: 10.1080/10683160008409804

- Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Landström, S. (2017). En modern brottmålsprocess anpassad även för stora mål: Några rättspsykologiska reflektioner [A modern criminal procedure adapted for major cases: Some legal psychologicalreflections]. In SOU 2017:7 Straffprocessens ramar och domstolens beslutsunderlag i brottmål – En bättre hantering av stora mål [The framework of the criminal procedure and legal decision-making in criminal proceedings - A better management ofmajor cases] (Appendix 7, pp. 201–215). Stockholm, Sweden: Wolters Kluwers.

- Granhag, P. A., & Vrij, A. (2005). Deception detection. In N. Brewer & K. D. Williams (Eds.), Psychology and law: An empirical perspective (pp. 43–92). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hackett, L., Day, A., & Mohr, P. (2008). Expectancy violation and perceptions of rape victim credibility. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 323–334. doi:10.1348/135532507x228458

- Hartwig, M., & Bond, C. F. (2011). Why do lie-catchers fail? A lens model meta-analysis of human lie judgments. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 643–659. doi: 10.1037/a0023589

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

- Heath, W. P., Grannemann, B. D., & Peacock, M. A. (2004). How the defendant’s emotional level affects mock juror’s decisions when presentation mode and evidence strength are varied. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 624–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02563.x

- Kahn, A., & McGaughey, T. A. (1977). Distance and liking: When moving close produces increased liking. Sociometry, 40, 138–144. doi: 10.2307/3033517

- Kaufmann, G., Drevland, G. C. B., Wessel, E., Overskeid, G., & Magnussen, S. (2003). The importance of being earnest: Displayed emotions and witness credibility. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17, 21–34. doi: 10.1002/acp.842

- Kawakami, K., Phills, C. E., Steele, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2007). (Close) distance makes the heart grow fonder: Improving implicit racial attitudes and interracial interactions through approach behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 957–971. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.957

- Klein, A. R., & Tobin, T. (2008). A longitudinal study of arrested batterers, 1995-2005: Career criminals. Violence Against Women, 14, 136–157. doi: 10.1177/1077801207312396

- Kramer, A., Lorenzon, D., & Mueller, M. (2004). Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics. Women’s Health Issues, 14, 19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.12.002

- Krohne, H. W. (2003). Individual differences in emotional reactions and coping. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 698–725). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Landström, S. (2008). CCTV, live and videotapes: How presentation mode affects the evaluation of witnesses (PhD Thesis). Department of psychology, Gothenburg University.

- Landström, S., Ask, K., & Sommar, C. (2015). The emotional male victim: Effects of presentation mode on judged credibility. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56, 99–104. Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12176

- Landström, S., & Granhag, P. A. (2010). In-court versus out-of-court testimonies: Children’s experiences and adults’ assessments. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 941–955. doi: 10.1002/acp.1606

- Landström, S., Granhag, P. A., & Hartwig, M. (2005). Witnesses appearing live versus on video: Effects on observers’ perception, veracity assessments and memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19, 913–933. doi: 10.1002/acp.1131

- Landström, S., Granhag, P. A., & Hartwig, M. (2007). Children’s live and videotaped testimonies: How presentation mode affects observers’ perception, assessment and memory. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 12, 333–348. doi: 10.1348/135532506X133607

- Landström, S., Willén, R., & Bylander, E. (2012). Rättspraktikers inställning till modern ljud- och bildteknik i rättssalen: en rättspsykologisk studie [Legal practitioners’ attitudes to modern courtroom technology: A psycholegal study.]. Svensk Juristtidning, 3, 197–219.

- Lens, K. M. E., van Doorn, J., Pemberton, A., & Bogaerts, S. (2014). You shouldn’t feel that way! extending the emotional victim effect through the mediating role of expectancy violation. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20, 326–338. doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2013.777962

- Lepore, L., & Brown, R. (2002). The role of awareness: Divergent automatic stereotype activation and implicit judgment correction. Social Cognition, 20, 321–351. doi: 10.1521/soco.20.4.321.19907

- MacKinnon, D., Krull, J., & Lockwood, C. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1, 173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371

- Moors, A., & De Houwer, J. (2006). Automaticity: A theoretical and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 297–326. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.297

- New York State Committee on Criminal Jury Instructions. (2004). Criminal jury instructions 2d. Retrieved from www.nycourts.gov/judges/cji/index.html

- Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 184–211. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1

- Nisbett, R., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- NJA. (2010). New legal archive: 671. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

- NJA. (2017). New legal archive: 316 I & II. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

- Orcutt, H. K., Goodman, G. S., Tobey, A. E., Batterman-Faunce, J. M., & Thomas, S. (2001). Detecting deception in children’s testimony: Factfinders’ abilities to reach the truth in open court and closed-circuit trials. Law and Human Behavior, 25, 339–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1010603618330

- Pozzulo, J. D., & Dempsey, J. L. (2009). The effect of eyewitness testimonial consistency and type of identification decision on juror decision making. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 27, 49–68.

- Rose, M. R., Nadler, J., & Clark, J. (2006). Appropriately upset? Emotion norms and perceptions of crime victims. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 203–219. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9030-3

- Ross, D. F., Hopkins, S., Hanson, E., Lindsay, R. C. L., Hazen, K., & Eslinger, T. (1994). The impact of protective shields and videotape testimony on conviction rates in a simulated trial of child sexual abuse.. Law and Human Behavior, 18, 553–566. doi: 10.1007/BF01499174

- Rubin, D. C., & Wenzel, A. E. (1996). One hundred years of forgetting: A quantitative description of retention. Psychological Review, 103, 734–760. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.734

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Scholer, A. A., & Higgins, E. T. (2008). People as resources: Exploring the functionality of warm and cold. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 1111–1120. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.509

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Strömwall, L. A., Granhag, P. A., & Jonsson, A.-C. (2003). Deception among pairs: ‘Let’s say we had lunch and hope they will swallow it!’. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 9, 109–124. doi: 10.1080/1068316031000116238

- Sullivan, T. P. (2010). The evolution of law enforcement attitudes to recording custodial interviews. The Journal of Psychiatry and Law, 38, 137–175. doi: 10.1177/009318531003800107

- Svea Court of Appeal, verdict 16 October 2007, in case B 3806-07.

- Swedish Ministry of Justice. (2004). Proposition 2004/05:131. En modernare rättegång - reformering av processen i allmän domstol [A more modern court – reforming procedures in general court].

- Tjaden, P. G., & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence. Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Tobey, A. E., Goodman, G. A., Batterman-Faunce, J. M., Orcutt, H. K., & Sachsenmaier, T. (1995). Balancing the rights of children and defendants: Effects of closed-circuit television on children’s accuracy and juror’s perception. In M. S. Zaragoza, J. R. Graham, G. C. N. Hall, R. Hirschman, & Y. S. Ben-Porath (Eds.), Memory and testimony in the child witness (pp. 214–239). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Uleman, J. S., Adil Saribay, S., & Gonzalez, C. M. (2008). Spontaneous inferences, implicit impressions, and implicit theories. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 329–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093707

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465

- Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1997). The flexible correction model: The role of naive theories of bias in bias correction. In P. Z. Mark (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 141–208). New York: Academic Press.

- WHO. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf

- Winkel, F. W., & Koppelaar, L. (1991). Rape victims’ style of self-presentation and secondary victimization by the environment: An experiment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6, 29–40. doi: 10.1177/088626091006001003

- Wojciszke, B., Bazinska, R., & Jaworski, M. (1998). On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 1251–1263. doi: 10.1177/01461672982412001

- Wrede, O., Ask, K., Strömwall, L., & Styvén, C. (2018). ‘I believe you, I would feel the same way’: Emotional overlap and perceptions of victims’ credibility. Manuscript in preparation.

- Zhao, X., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257