ABSTRACT

Present evidence regarding widely used risk assessment tools suggests that such tools may have inferior predictive validity for offenders with a migration background (MB), especially from Turkey and Arab countries. Based on a thorough literature review, we investigated additional risk and protective factors via a postdictive correlational study design. We assumed that delinquency is induced by discrimination, a conflict of values, norms of honour, a disapproval of sexual self-determination, and antisemitism. In contrast, we expected social support to diminish the risk of criminal behaviour. The sampling took place inside and outside prison, where adult men with an Arab or Turkish MB (n = 140) filled out a questionnaire. Individual norms of honour (r = .27−.41), antisemitism (r = .31−.37), and a disapproval of sexual self-determination (r = .23−.26) were positively correlated with delinquency. The best predictor was the individual’s perception of friends’ norms of honour (r = .34−.56). However, only a few significant correlations were found for a perception of individual discrimination (r = .08−.14) and an internal conflict of values (r = .11−.15), whereas global discrimination (r = .20−.29) clearly emerged as a risk factor for delinquency. Social support by nondelinquent peers could be confirmed as having a protective influence against delinquency (r=−.25−.27). Theoretical and practical implications for risk assessment are discussed.

Reflecting the diversity in European societies (Eurostat, Citation2017), offender populations are increasingly diverse as well (Aebi, Tiago, & Burkhardt, Citation2015; van der Put et al., Citation2011). Irrespective of socio-demographic factors (Albrecht, Citation1995), offenders with a migration background [MB] are overrepresented in most official statistics and among the prison population (Aebi et al., Citation2015; Veen, Stevens, Doreleijers, & Vollebergh, Citation2011). Although differences in arrest rates may be mediated by stereotypes and racial bias in law enforcement (Junger-Tas, Citation1997; Snowball & Weatherburn, Citation2016; Taillandier-Schmitt & Combalbert, Citation2017), the results of self-reported delinquency support the findings of overrepresentation in most studies (Baier & Pfeiffer, Citation2008; Belhadj Kouider, Koglin, & Petermann, Citation2014; Dimitrova, Chasiotis, & van de Vijver, Citation2016; Junger & Polder, Citation1992; Torgersen, Citation2010).

Many theories attempt to explain why someone engages in criminal behaviour. Prominent theories that comprise a lot of social and developmental influences endorse a multiple set of factors that increase (risk factors) or decrease (protective factors) the probability of delinquency (e.g. Farrington, Citation2005; Lösel, Citation2003; Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Wei, Farrington, & Wikström, Citation2002). However, these theories give hardly any consideration to cross-cultural variability of risk and protective factors. According to this view, the high percentage of offenders with a MB among offender populations can be explained by a different exposure to general risk factors (e.g. Schmitt-Rodermund & Silbereisen, Citation2008). The evidence supports this assumption (e.g. Baier & Pfeiffer, Citation2008) because people with a MB are often disadvantaged, especially with regard to education and employment (Heath, Rothon, & Kilpi, Citation2008). However, not all variance in offending rates can be explained by differences in the manifestation of common risk factors like low socio-economic status (Junger & Polder, Citation1992) or school level (Baier & Pfeiffer, Citation2008). Likewise, recent evidence suggests that the validity of common risk factors might vary between different cultural subgroups (Asscher et al., Citation2013; Oberwittler, Citation2007; Öncül, Citation2008; van der Put et al., Citation2011). Thus, some scholars have questioned the assumption of an invariant mode of action of risk factors (Jones, Masters, Griffiths, & Moulday, Citation2002; Marcell, Citation1994; Shepherd, Citation2015; van der Put, Stams, Dekovic, Hoeve, & van der Laan, Citation2013). Although many well-known risk factors (e.g. substance abuse) are supposed to be valid in every cultural subgroup, this approach overlooks the importance of cultural values in forming daily life and norms (c.f. Shepherd & Lewis-Fernandez, Citation2016). It also fails to notice specific challenges migrants face during acculturation (Phinney, Citation1992), namely the psychological process of adopting the cultural traits of another group (Berry, Citation2006).

Following the assumption of an invariant mode of action of risk factors, widely-used risk assessment procedures and instruments like Level of Service (LS) instruments (Andrews & Bonta, Citation2010) essentially build on common theories of crime. Moreover, nearly all studies confirming the validity of the LS instruments – taken here as an example of a widely used comprehensive risk assessment tool – were conducted in Euro-American countries (Olver, Stockdale, & Wormith, Citation2014). However, findings concerning the generalizability of these methods for diverse offender populations are ambiguous. First, standardized risk assessment tools highly depend on verified information about the biography (e.g. previous offences), which is often not accessible especially among immigrants (Schmidt, van der Meer, Tydecks, & Bliesener, Citation2018). Second, the cultural equivalence of the underlying constructs and measurements has rarely been verified (Cooke, Michie, Hart, & Clark, Citation2005; Veen, Stevens, Andershed, et al., Citation2011). Third, and most importantly, the predictive validity of these risk assessment procedures could not always be ensured. This may be the case when base rates of single risks are different among cultural groups and the calibration of an assessment tool may be biased (Fazel et al., Citation2016). The generalizability of validation parameters also is threatened when cultural factors constitute environmental characteristics that may have an impact on the design or feasibility of validation research (Fazel & Bjørkly, Citation2016), which might be connected to the first and second point. While some evidence suggests that there is cross-cultural validity (Bhutta & Wormith, Citation2016; Olver et al., Citation2014; Takahashi, Mori, & Kroner, Citation2013; Zhang & Liu, Citation2015), other studies have found reduced predictive power (Gutierrez, Wilson, Rugge, & Bonta, Citation2013; Onifade, Davidson, & Campbell, Citation2009; Schmidt et al., Citation2018; Singh, Grann, & Fazel, Citation2011; Wilson & Gutierrez, Citation2014; Wormith, Hogg, & Guzzo, Citation2015), and some have even reported a total lack of predictive validity for culturally diverse samples (e.g. Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Schlager & Simourd, Citation2007; Shepherd, Singh, & Fullam, Citation2015). In Germany, the LS instruments and their related risk factors show an inferior predictive validity – even when the reliability of biographical information was ensured – for adult inmates (Schmidt et al., Citation2018) and for young, violent inmates (Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014) with a Turkish or an Arab MB compared to non-minority controls. What makes these findings truly alarming is that offenders descending from Turkey, North Africa, and the Near East comprise the largest number of offenders with a MB in Germany and other European countries (Bauer et al., Citation2011; Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Hilterman, Nicholls, & van Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2014; Schmitt-Rodermund & Silbereisen, Citation2008; Senatsverwaltung für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz, Citation2015 [Berlin Senate Administration for Justice and Consumer Protection]; van der Put et al., Citation2011).

Notwithstanding the different migration histories (labour migration vs. asylum seeking) of migrants from Turkey, North Africa, and the Near East, research has shown that many of them are equally afflicted by acculturative stressors such as low economic status (e.g. Algan, Dustmann, Glitz, & Manning, Citation2010; Kogan, Citation2004) and discrimination (e.g. Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt, Citation2013; Kaas & Manger, Citation2012; Klink & Wagner, Citation1999; Rangvid, Citation2007). Furthermore, many people from Turkey, North Africa, and the Near East share similar cultural values, like a collectivist orientation, very close social bonds, low egalitarianism, low autonomy (Hofstede, Citation2001; Ingelhart & Baker, Citation2000; Schwartz, Citation2006), and a great importance of traditions and norms of honour (Schwartz, Citation2006; Uskul, Cross, Sunbay, Gercek-Swing, & Ataca, Citation2012). Contradicting the assumption of an invariant mode of action of risk factors, such acculturative stressors and culturally shaped values can be seen as additional risk and protective factors, as they moderate the pathways to delinquency (Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). Given the great similarity between value orientation and acculturative stressors, we have taken migrants from Turkey and Arab countries as examples to study the potential influences on delinquency that are sensitive to migration and culture. We are well aware that this summarization is very broad and somehow neglects potential differences in migration histories and cultural backgrounds. Given the fact that the offender population is highly diverse (e.g. more than 90 nationalities imprisoned in Berlin, Senatsverwaltung für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz, Citation2015 [Berlin Senate Administration for Justice and Consumer Protection]), some categorization has to be done to derive proper theoretical assumptions. We decided to use general cultural value orientation and acculturative stressors as criteria rather than nationality because the factors we studied are associated with cultural values and acculturation.

We have chosen factors that are discussed most often in the intercultural literature in connection with externalizing problem behaviour and delinquency (van Leeuwen, Rodgers, Bui, Pirlot, & Chabrol, Citation2012). Moreover, these factors have been highlighted by forensic experts as potential causes of delinquency. Schmidt, van der Meer, Tydecks, and Bliesener (Citation2017) asked 128 forensic experts in Germany how delinquency among people having an Arab or Turkish MB can be explained. They found that, next to common risk factors (e.g. drug abuse), the experts strongly emphasized additional aspects that are either associated with acculturation (e.g. perceived discrimination) or with culturally shaped values (e.g. norms of honour).

Risk factors associated with acculturation

Events that could cause stress to psychological and social adjustment after migration are experiences of discrimination in different areas of life. Discrimination can be experienced directly via interpersonal contact or it can refer to an individual’s perception of collective victimhood (Verkuyten, Citation1998). Collective victimhood can be further differentiated into structural violence (e.g. inequality in education) or direct violence (e.g. war; Noor, Vollhardt, Mari, & Nadler, Citation2017). Any kind of discrimination can be perceived as a threat to identity, which can foster negative emotions and diminish self-esteem (Fisher, Citation2000; Liebkind & Jasinskaja-Lahti, Citation2016). This may not only influence well-being (Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, Citation2014) and health (e.g. Harris et al., Citation2006; Mewes, Asbrock, & Laskawi, Citation2015; Pascoe & Smart Richman, Citation2009; Stevens, Vollebergh, Pels, & Crijnen, Citation2005), but it can also increase the propensity of antisocial behaviour. Empirical evidence from North America supports a discrimination-delinquency relationship (Burt, Simons, & Gibbons, Citation2012; Le & Stockdale, Citation2011; Martin et al., Citation2011; Prelow, Danoff-Burg, Swenson, & Pulgiano, Citation2004; Sittner Hartshorn, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, Citation2012). For example, Martin et al. (Citation2011) found perceived individual discrimination to be correlated to self-reported delinquency (r = .11−.22) among African-American children. Studies in Europe generally corroborate these findings (Liebkind & Jasinskaja-Lahti, Citation2016; van Leeuwen et al., Citation2012). However, nearly all the present evidence is related to child and adolescent samples of the general population. Discrimination as a risk factor for serious offences has rarely been studied.

A second aspect associated with acculturative stress is a confrontation with conflicting cultural values (Phinney, Ong, & Madden, Citation2000). If switching between different values is impossible, such confrontation can determine the experience of culturally based internal conflicts – a feeling of being caught between two cultures and exposed to unavoidable social rejection (Giguère, Lalonde, & Lou, Citation2010). On the one hand, this is closely associated with experiences of discrimination (Mena, Padilla, & Maldonado, Citation1987) because it diminishes adaptive strategies like switching identities and implies social rejection. On the other hand, intergenerational conflicts can boost interpersonal and intrapersonal value conflicts (Dennis, Basañez, & Farahmand, Citation2010; Rick & Forward, Citation1992). This is particularly the case when parents adhere to an authoritarian child rearing style and traditional norms (Park, Kim, Chiang, & Ju, Citation2010). An intense experience of a conflict of values can also foster deviant behaviour as a maladaptive strategy for coping with negative emotions (McQueen, Greg Getz, & Bray, Citation2003; Shrake & Rhee, Citation2004).

Risk factors associated with culturally shaped values

Culturally shaped values that often contradict the values of European host societies are traditional normative obligations regarding the family (Giguère et al., Citation2010). Accompanying a high familial embeddedness, the maintenance of family honour is required in honour cultures (Mosquera, Manstead, & Fischer, Citation2002; Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). Thereby, honour is defined as a social reputation that also permits violence in response to reputational threats (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, Citation1996). This reputation can either take the form of dignity and prestige in connection to masculinity (Turkish: seref; Arab: sharaf) or family honour as the sexual purity of female family members (Turkish/Arab: namus; van Osch, Breugelmans, Zeelenberg, & Boluk, Citation2013). The influence that traditional norms of honour have on the emergence of violent delinquency can be explained via social information processing theory (SIT: Crick & Dodge, Citation1994; cf. Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). Following this theory, culturally shaped norms are stored in the long-term memory, which can affect actual information processing. It has been shown that a strong commitment to norms of honour heightens anger (Maitner, Mackie, Pauketat, & Smith, Citation2017) and the impulse to defend oneself (Maitner et al., Citation2017). Especially in the context of a prevention focus (Shafa, Harinck, Ellemers, & Beersma, Citation2015), norms of honour trigger violent action schemata (Arsovska & Verduyn, Citation2007; Baker, Gregware, & Cassidy, Citation1999; Kulwicki, Citation2002) and the legitimization of violence (Baldry, Pagliaro, & Porcaro, Citation2013; Caffaro, Ferraris, & Schmidt, Citation2014; Caffaro, Mulas, & Schmidt, Citation2016; Hayes & Lee, Citation2005). Consequently, norms of honour also affect behaviour by enhancing aggressive reactions (Cohen et al., Citation1996; van Osch et al., Citation2013) and violent offences (Baier & Pfeiffer, Citation2008; Enzmann, Brettfeld, & Wetzels, Citation2004; Lahlah, van der Knaap, Bogaerts, & Lens, Citation2013). Given the preference for a collectivistic orientation in Turkey (Ayçiçegi-Dinn & Caldwell-Harris, Citation2011; Cukur, Guzman, & Carlo, Citation2004) and Arab countries (Buda & Elsayed-Elkhouly, Citation1998), two aspects are especially important with respect to norms of honour: the social situation that affords a particular behaviour (Kitayama, Citation2002) and the perception of others close to them (Beersma, Harinck, & Gerts, Citation2003). Therefore, it is crucial to study the honour-violence relationship in situational contexts and in connection with other’s expectations (Uskul et al., Citation2012). Here, norms of family honour are presumed to be key to explaining aggression in Turkey and Arab countries (van Osch et al., Citation2013).

Next to specific situations, the adherence to traditional cultural values can also be an indicator of a general dis-identification with norms and rules of the host society, which, in turn, can promote delinquency. According to the well-established Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation2004), dis-identification is caused by perceived threats to one’s identity. For example, experienced discrimination can strengthen a reactive ingroup affirmation (Mähönen, Jasinskaja-Lahti, & Liebkind, Citation2011; Verkuyten & Yildiz, Citation2007), which can – but need not necessarily – lead to the rejection of the outgroup (Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, & Solheim, Citation2009), especially in connection to a perceived identity incompatibility of values (Hutchison, Lubna, Goncalves-Portelinha, Kamali, & Khan, Citation2015; Martinovic & Verkuyten, Citation2012; Schwartz, Struch, & Bilsky, Citation1990). An oppositional identity might be formed when the host society is clearly rejected and devalued (Fordham & Ogbu, Citation1986; Shrake & Rhee, Citation2004). This can lead to a radical (Simon & Ruhs, Citation2008) or to a delinquent group affiliation (Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). A devaluation of western societies is often associated with a wholesale disapproval of sexual self-determination, with homophobia (Anderson & Koc, Citation2015; Brettfeld & Wetzels, Citation2007; Hooghe, Claes, Harell, Quintelier, & Dejaeghere, Citation2010), and with antisemitism (Arnold & Jikeli, Citation2008; Mansel & Spaiser, Citation2013).

Protective factors sensitive to cultural socialization

Going beyond, culturally shaped values can also provide strong protective influences against delinquency. People from Turkey or Arab countries most commonly display a collectivist orientation (Ayçiçegi-Dinn & Caldwell-Harris, Citation2011; Buda & Elsayed-Elkhouly, Citation1998; Cukur et al., Citation2004) and prefer an interdependent self-concept (Dwairy, Citation2006; Kagitcibasi, Citation2005). Emphasizing an interdependent self-concept, there is a strong tendency to emphasize the groups’ interests over the individual’s, to highly value social harmony, and to be closely connected to important others. This largely applies to migrants from these countries, too (Aelenei, Darnon, & Martinot, Citation2016; Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, Citation2008; Ayçiçegi-Dinn & Caldwell-Harris, Citation2011). Interdependent family structures and extended social networks among migrants can provide greater social support, which has been shown to be a buffer for acculturative stressors (Danzer & Ulku, Citation2011) and a protective influence against delinquency (Le & Stockdale, Citation2005). Social support is supposed to be a general protective influence against delinquency (Stouthamer-Loeber et al., Citation2002) that might be even more important in collectivist cultures than in individualist cultures, which can only be checked via a cross-cultural comparative study.

Next, it should be noted that interpersonal warmth is not always a protective influence by any means. When closeness goes along with an endorsement of hierarchy, it may hinder self-determined decision making (Liebkind & Jasinskaja-Lahti, Citation2016). This may even provoke deviant behaviour in relation to permitted norms of honour (Toprak & Alshut, Citation2013). Thus, the protective influences of social support should be constrained to the commitment to prosocial norms by important others.

Purpose of the study

Given the scattered evidence that the validity of common risk factors for delinquency might be reduced for offenders coming from Turkey or Arab countries (Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Schmidt et al., Citation2018; Shepherd et al., Citation2015), a consideration of potential additional influences seems to be important to ensure a culturally fair assessment procedure (Shepherd & Lewis-Fernandez, Citation2016) as well as effective prevention and intervention measures (Jones et al., Citation2002; van der Put et al., Citation2011). Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyse the postdictive validity of potential risk and protective factors that are sensitive to migration and culture for people with a Turkish or Arab MB. To contribute to offender risk assessment, we examine these factors not only among adult men from the general population, but also among adult inmates. Thereby, a greater variance of the frequency and severity of delinquency can be expected. In line with the intercultural literature (van Leeuwen et al., Citation2012) and forensic experts’ suggestions (Schmidt, van der Meer, et al. Citation2017), we assume the following:

Hypothesis 1: Risk factors associated with acculturation, like perceived discrimination and experience of an internal conflict of values, correlate positively with delinquency among men with a Turkish or Arab MB.

Hypothesis 2: Risk factors associated with culturally shaped values, like adherence to traditional norms of honour, disapproval of sexual self-determination, and antisemitism, correlate positively with delinquency among men with a Turkish or Arab MB.

Hypothesis 3: Protective factors sensitive to cultural socialisation, like a supportive relationship with family and nondelinquent peers, correlate negatively with delinquency. The protective influence of social support, however, should be influenced by the individual’s perception of the norms of honour of family and friends.

Method

Sample

The sample (N = 140) consisted of adult, male inmates with a MB from correctional institutions (n = 56, 40.0%) and adult male participants with a MB from the general population (n = 84, 60.0%) in Berlin. We asked the participants about the country of origin of their family. Half of the sample were of Turkish origin and the other half were of North African or Near Eastern descent (see ). Nearly two-third of the sample can be considered first-generation migrants as they were born abroad (see ). Many participants (60.7%) had a residential permit of unlimited duration or even German citizenship. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 63 years (M = 34.31, SD = 10.12). As shows, the educational level in the total sample was rather high, as 46.5% had completed A-Levels. One additional question assessed religious affiliation. Most participants considered themselves to be Muslim (see ).

Table 1. Participants demographic characteristics.

Measures

To broadly gather information about very different risk and protective factors sensitive to migration and culture, different scales were pooled into one questionnaire in this study.Footnote1 We often decided to use truncated scales and selected the most appropriate items to keep the length of the survey to an acceptable level for a community sample. This selection was based on theoretical considerations to use items that seemed to measure the constructs best, or – if available – on the psychometric properties of the items (e.g. factor loadings).

Concerning discrimination, we examined two different facets separately. General perception of individual discrimination in different areas of life was assessed with 5 items (e.g. ‘In looking for a good job, I sometimes feel that my ethnicity is a limitation’.) of the Acculturation Stress Scale used by Mena et al. (Citation1987). The authors reported good internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha [α] = .89) for the original 17-item scale in their student sample. Global discrimination included two different forms of discrimination. First, we adapted the 4 questions of Weitzer and Tuch (Citation1999) according to our context (black vs. migrant background) to measure discrimination by the police (e.g. ‘Racism is a widespread phenomenon inside the police’). Second, collective victimization was assessed via 2 items taken from the survey of Brettfeld and Wetzels (Citation2007, e.g. ‘Muslim children are disadvantaged in Germany’.) pertaining to structural violence and 3 items referring to collective violence according to Schori-Eyal, Halperin, and Bar-Tal (Citation2014). Because the original 4-item scale of historical collective victimhood designed by Schori-Eyal et al. (Citation2014) referred primarily on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and showed poor internal consistency (α = .63), we used only 3 items with acceptable factor loadings and adapted these items according to our context (e.g. ‘People in Islamic countries are often poor, because they are suppressed by the West’.). All questions regarding discrimination were answered using a four-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 3 = strongly agree).

The internal conflict of values scale contained 6 items (e.g. ‘It bothers me that family members I am close to do not understand my new values’) that had to be rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 3 = strongly agree). We selected items, which point to an internal conflict, from the original 17-item Acculturation Stress Scale used by Mena et al. (Citation1987).

Regarding norms of honour, we focused on family honour. Here, we investigated two different perspectives: individual norms of honour and the assumed norms of others close to them. Individual norms of honour was measured via a seven item scale by Neuhaus (Citation2011) assessing the concept of traditional family and female honour (e.g. ‘Women should be punished, if they violate the honour of the family’.) via a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). For Neuhaus’ sample of 1109 German adolescents with a MB a very good consistency (α = .89) was found for this scale. The family’s norms of honour and friends’ norms of honour perspectives were measured via two vignettes developed for this study (see Appendix). We used two short texts describing critical incidents that might lead to violence according to the culture of honour (Boiger, Güngör, Karasawa, & Mesquita, Citation2014; van Osch et al., Citation2013). Participants were instructed to carefully read the vignettes and imagine themselves as the protagonist. Afterwards, they were asked about the expected reaction (‘If I were Ali, my family would expect me … ’). Four different alternatives (prosocial, avoiding, verbally aggressive, and physically aggressive) were given that were to be rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 3 = strongly agree). The same question was also asked with friends as the social reference group. For the present study, ratings for verbally and physically aggressive answers were pooled together from the two vignettes, composing a 4-item scale for family and friends, respectively.

To measure devaluation of the host society, two indicators were chosen. The 4-item antisemitism-scale, was developed for this study – containing one item from Brettfeld and Wetzels (Citation2007, e.g. ‘Jewish people are arrogant and greedy for money’.) and 3 items taken from Mansel and Spaiser (Citation2013; e.g. ‘Jewish people have too much influence in the world’) that needed to be answered on a four-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 3 = strongly agree). Disapproval of sexual self-determination was measured using two items taken from the survey of Brettfeld and Wetzels (Citation2007; ‘The way western societies deal with sexuality is a sin’ and ‘Homosexuality is not acceptable’.) with a four-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 3 = strongly agree).

Social support was measured on a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree) for family and friends separately. Therefore, four items of the Social Support Questionnaire (Fydrich, Sommer, Tydecks, & Brähler, Citation2009) were selected and slightly adapted to the specific social context (e.g. ‘In my family, there are people who I can get help from at any time’.). According to Fydrich et al. (Citation2009), the original 14-item Social Support Questionnaire showed good reliability values (e.g. α = .94).

Information about delinquency was obtained via self-assessment following similar surveys among pupils in Germany (Baier, Citation2014). Participants were asked how often (never, one time, 2–5 times, more than 5 times) they committed 6 different non-violent crimes (e.g. drug trafficking) and 6 different violent crimes (e.g. robbery) in the past ten years. Items were summed up to the frequency of nonviolent delinquency, the frequency of violent delinquency and a total score frequency of overall delinquency. Previous convictions and the age of first conviction were assessed afterwards. On this basis, a sum score for the severity of delinquency was constructed for this study. Nine dichotomous variables regarding criminal history were summarized in accordance with Andrews and Bonta (Citation2010; see Appendix Table A).

Furthermore, the information about the delinquency was used to split the sample. Participants who did not serve a sentence during the assessment and who did not report any law violation during the past ten years were considered to be non-offenders (n = 35), the rest were labelled as offenders (n = 98). We split the sample of offenders again according to the type of crime the offenders reported. Participants who admitted at least one violent crime were labelled as violent offenders (n = 40), the rest as non-violent offenders (n = 58).

Procedure

To ensure question comprehension and usability especially for the specific population (Schwarz, Citation1999), the whole questionnaire was pretested and items reformulated when necessary. Therefore, we applied cognitive interview techniques of probing and thinking aloud (Fowler, Citation1995) among four participants who were male and had a Turkish or Arab MB. Similarly, the vignettes were tested with respect to their intelligibility and authenticity among five additional participants. Moreover, in an online survey, 89 psychology students rated the various reaction alternatives of the vignettes. Only vignettes and answers with more than 90% rater-agreement were used in this study. After the questionnaire was constructed in German, it was translated according to the back-translation method (Brislin, Citation1970) into Arabic and Turkish by two independent translators each (one of them being a psychologist).

Participants were recruited using flyers entitled: ‘Looking for Turkish and Arab men to take part in a study’. Next to the flyers, all participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, the total anonymity of the data collection, and participant compensation. Participants from the general population were recruited in pedestrian zones, cafes, and sport clubs in Berlin districts with a high percentage of immigrants. The selection of the participants in pedestrian zones and cafes was random. Volunteers filled out the questionnaire after all necessary information were given. Furthermore, soccer clubs were contacted, and the flyers were distributed there. The research team was invited to take part in one lesson to present the study. Volunteers filled out the questionnaire right after the sports lesson. The participants from the general population were informed about the study before they filled out the questionnaire. Afterwards, the participants received 5 € as compensation in cash.

Inmates were first contacted by flyers which were distributed in all prison facilities for convicted adult male offenders in Berlin. Similar to the sample from the general population, the research team provided study information in every detention centre via information events. The questionnaire was then distributed to volunteers by the prison staff or the research team. The inmates had to sign a written declaration of consent. These documents were collected and stored separately from questionnaires to provide anonymity. Completed questionnaires were collected in sealed envelopes. The inmates received coffee worth 5€ as a compensation.

Filling out the questionnaire took approximately 45 min. In addition to the variables relevant to this study, further information about conflict management and religion was collected. Demographic characteristics (such as cultural background) were assessed at the end to control for potential cultural priming effects (Kühnen & Oyserman, Citation2002). The study was approved by the Criminological Research Service at the Berlin Ministry of Justice and the commission of ethics at the Institute of Psychology of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Statistical analyses

Approximately 4.3% of data was missing, ranging from 0.7% to 10.6%, and the pattern of missing data was arbitrary. Following Wadsworth and Roberts (Citation2008) – who tested imputation methods for crime data – we imputed missing data to avoid potential bias. We applied stochastic regression as it was the most appropriate and economic solution for our data (Lüdtke, Robitzsch, Trautwein, & Köller, Citation2007).

One-Dimensionality of the different scales were examined through factor analyses. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to examine the internal consistency. In the case of less than 3 items per scale, a correlation coefficient (Spearmans rho) was used as a measure of consistency.

To examine differences between offenders (at least one offence in the past ten years) and non-offenders, we applied one-sided t-tests with adjusted degrees of freedom according to the Welch test. We used this method instead of the student t-test because it is supposed to be superior in cases of unequal sample sizes, especially when variances are not equal (Zimmerman, Citation2004). While conducting such multiple significance tests, we considered the false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini & Hochberg, Citation1995). We used this method because it shows substantially more statistical power than adjustments via the family-wise error rate (Benjamini & Hochberg, Citation1995). The FDR is the expected proportion of falsely rejected hypotheses among all rejections according to a defined threshold. For this purpose, p-values were arranged in descending order and compared to the reference value (position-number * 0.05/amount of the hypothesis) stopping at the first occasion where the p-value is smaller than the reference value and rejecting all following hypotheses (Benjamini & Yekuteli, Citation2001).

Bivariate correlation coefficients were used to investigate the relationship of risk and protective factors with delinquency and tested one-sided according to our hypotheses. Multiple linear regression analysis was applied to examine the potential mediation of social support by the approved norms. Finally, all risk and protective factors were tested simultaneously via multiple linear regression analyses.

Results

Reliability of scales and descriptive results

The scales individual discrimination, global discrimination, individual norms of honour, antisemitism, disapproval of sexual self-determination, family’s norms of honour, friends’ norms of honour, social support by family, and social support by friends were not adjusted and showed sufficient to very good internal consistency (see ). The reliability of the conflict of values scale was α = 0.71 after removing 2 items that were unrelated to the scale according to the factor analysis. As further indicates, all scales were not normally distributed according to the results of Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Most variables showed a positive skewness, implying low prevalence, particularly for family’s and friends’ norms of honour. Furthermore, friends’ norms of honour was reported more often than family’s norms of honour, t(139) = 3.50, p < .001, d = 0.26. In contrast, a negative skewness, indicating a high prevalence, was found for the risk factor global discrimination. More than half of the sample reported a high extent of discrimination. A remarkable negative skewness was also found for both protective factors of social support, indicating high assistance in general. Meanwhile, social support was more strongly provided by the family than by friends, t(139) = 4.18, p < .001, d = 0.41.

Table 2. Central tendency.

The inspection of the intercorrelations (see Appendix Table B) showed moderate to large correlations of individual norms of honour with friends’ norms of honour (r = .39, p < .001) and family’s norms of honour (r = .40, p < .001), antisemitism (r = .60, p < .001), and disapproval of sexual self-determination (r = .56, p < .001). Friends’ norms of honour and family’s norms of honour (r = .61, p < .001), as well as antisemitism and disapproval of sexual self-determination (r = .60, p < .001) were also interconnected. Furthermore, individual and global discrimination were highly correlated (r = .59, p < .001), while, individual discrimination and internal conflict of values (r = .39, p < .001), as well as global discrimination and internal conflict of values (r = .37, p < .001) were moderately correlated.

Differences between offenders and non-offenders

To check for equivalent sample properties, offenders (n = 98) and non-offenders (n = 35) were compared according to their basic demographic characteristics. No differences were found for age, t(48.57) = 1.81, p > .05, d = 0.38, their cultural background (a Turkish heritage), χ2 (N=133; df=1)=1.07, p > .05, phi = .09, and educational level, χ2 (N=129; df=3)=7.74, p > .05, phi = .24. However, offenders were more often second generation immigrants (49%) than non-offenders (8.6%), χ2 (N=131; df=1)=17.72, p < .001, phi = .36.

After considering the FDR, significantly higher scores for offenders compared to non-offenders were found for the risk factors, global discrimination, t(57.09) = −3.24, p < .001, d = 0.66, individual norms of honour, t(52.93) = −1.91, p < .031, d = 0.41, antisemitism, t(59.11) = −2.92, p < .002, d = 0.58, family’s norms of honour, t(96.94) = −3.21, p < .001, d = 0.51, and friends’ norms of honour, t(90.39) = −2.34, p < .011, d = 0.38. No differences were found for individual discrimination, t(56.82) = −1.01, p > .05, d = 0.21, internal conflict of values, t(57.14) = −1.44, p > .05, d = 0.28, and disapproval of sexual self-determination, t(55.85) = −1.36, p > .05, d = 0.28. The protective factors, social support by family, t(63.37) = −0.10, p > .05, d = 0.02, and social support by friends, t(63.77) = 1.19, p > .05, d = −0.23, were not able to differentiate between offenders and non-offenders. The analyses were also run with non-parametric tests that gave approximately the same results (see Appendix Table C).

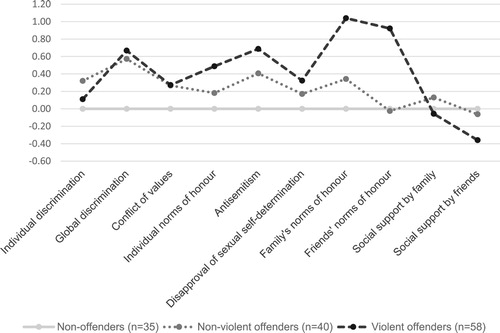

For illustration purposes, we z-standardized the means of the scales while non-offenders (n = 35) served as the reference group. Furthermore, we also differentiated between non-violent offenders (n = 40) and violent offenders (n = 58) to inspect differences in their risk profiles. shows that global discrimination, individual norms of honour, antisemitism, as well as family’s and friends’ norms of honour appear to be most prevalent among violent offenders. In contrast, social support by friends seems to be especially low for violent offenders.

Correlations with different measures of delinquency

To examine whether risk and protective factors are associated with more continuous measures of delinquency (frequency and severity), correlation coefficients were computed. As shows, all assessed factors correlated with at least one measure of delinquency. Small and sometimes nonsignificant positive effect sizes were found for risk factors sensitive to migration: individual discrimination (r = .08−.14) and conflict of values (r = .11−.15). Small to moderate effects were found for the risk factor global discrimination (r = .18−.29) and the protective factor social support by friends (r = −.25–.27). Moderate positive effect sizes were found for risk factors antisemitism (r = .31−.37), individual norms of honour (r = .37−.41), and family’s norms of honour (r = .27−.43), and large effects were found for the risk factor friends’ norms of honour (r = .34−.56).

Table 3. Correlations between risk and protective factors sensitive to migration and culture and different measures of delinquency.

In addition, we analysed offenders (n = 98) separately, to check whether the risk and protective factors are also relevant for an offender population (see Appendix Table D). Here individual norms of honour (r = .26−.46), antisemitism (r = .27−.33), disapproval of sexual self-determination (r = .24−.28), friends’ norms of honour (r = .35−.59), and social support by friends (r = −.26–.29) were related to the frequency and severity of delinquency. Family’s norms of honour significantly correlated to variables pointing to the frequency of delinquency (r = .36−.40).

Multivariate analyses

To test whether the correlation of social support by friends was affected by their norms of honour, a mediator analysis according to Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) was run. Friends’ norms of honour positively correlated with delinquency (r = .56, p < .001), while, in contrast, social support by friends correlated negatively with friends’ norms of honour (r = −.25, p < .002). The univariate correlation of social support by friends with delinquency (r = −.27, p < .001) was reduced to β = −.14 (p < .032; one-sided) in the linear regression analysis, F(132,2) = 32.34, p < .001, R2 = .33, indicating a partial mediation.

Furthermore, all the risk and protective factors that turned out to be valid in the univariate analyses were simultaneously examined for every measure of delinquency (see ). In sum, the regression analyses revealed the substantial predictive power of the culture-sensitive risk and protective factors (R2 = .27−.39). However, only one scale – friends’ norms of honour – contributed significantly within all models. Although the indices of collinearity showed acceptable values (Tolerance = .48−.93), many risk factors seem to share a great amount of variance.

Table 4. Multiple regressions of different measures of delinquency on risk and protective factors sensitive to migration and culture.

Discussion

Identifying valid risk and protective factors of delinquency is essential for risk assessment. In addition, these factors determine prevention and intervention measures (Andrews & Bonta, Citation2010). As present evidence suggests that common risk factors might have a reduced predictive validity among offenders with an Arab or Turkish MB (Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Schmidt, Pettke, Lehmann, & Dahle, Citation2017; Shepherd et al., Citation2015), an approach taking into account stressors of acculturation and culturally shaped norms might be very valuable. The aim of this study was to validate culture-sensitive risk and protective factors. Based on a thorough literature review, we assumed that acculturative stressors (individual and global discrimination, conflict of values; hypothesis (1)) as well as culturally shaped norms and attitudes (norms of honour, disapproval of sexual self-determination, antisemitism; hypothesis (2)) induce delinquency. In contrast, we expected social support by close others, which is highlighted by a collectivistic value orientation, to diminish the risk of criminal behaviour (hypothesis 3). Adult men with an Arab or Turkish MB filled out a questionnaire, assessing these specific factors. The analyses yielded the following main results: First, for most risk and protective factors, significant correlations with the frequency of delinquency were found. Many of these factors also showed significant correlations with the severity of delinquency among a subsample of offenders. Second, attitudes like individual norms of honour, antisemitism and a wholesome disapproval of sexual self-determination positively correlated with delinquency, which supported our second hypothesis. According to the multivariate findings, the individual’s perception of friends’ norms of honour was the best predictor for the frequency of delinquency, while global discrimination and antisemitism predicted the severity of delinquency best. Third, just a few significant correlations with delinquency were found for acculturative stressors like individual discrimination and an internal conflict of values. Only global discrimination clearly emerged as a risk factor for delinquency. Thus, our first hypotheses could not be rejected nor be supported. Fourth, social support by friends could be confirmed as a protective influence against delinquency, according to our third hypothesis.

Theoretical implications

As most of the risk and protective factors sensitive to migration and culture showed significant correlation with the frequency and the severity of delinquency, these factors should be included in comprehensive theories of crime. For example, individual adherence to norms of family honour correlated moderately with delinquency, which is in line with previous findings (Baier & Pfeiffer, Citation2008; Enzmann et al., Citation2004; Lahlah et al., Citation2013; Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). However, norms of family honour have not yet been integrated in wide-ranging theories of crime that underlie standardized risk assessment procedures (e.g. Andrews & Bonta, Citation2010). Honour was primarily discussed in connection to gang violence (Hayes & Lee, Citation2005) and masculinity (Hochstetler, Copes, & Forsyth, Citation2014; Horowitz & Schwartz, Citation1974). Even a more specific approach – the culture of honour (Cohen et al., Citation1996) – was mainly used to explain differences in homicide rates and their underlying motivation among white South American males (Campello de Souza, Campello de Souza, Bilsky, & Roazzi, Citation2016; Vandello & Cohen, Citation2003). However, our results indicate that traditional norms of family honour are also relevant for delinquency. Even though our findings suggest that norms of honour are particularly connected to violent delinquency, we also found positive correlations with non-violent delinquency, corroborating similar findings (Somech & Elizur, Citation2009). Thus, norms of family honour should be highlighted much more when explaining general delinquency among immigrants from honour cultures. Additionally, our results stress the importance of situation-dependent social obligations for individual behaviour in collectivist honour cultures (Dwairy, Citation2002; Uskul et al., Citation2012) because the best predictor of the frequency of delinquency in the present study was the individual’s perception of friends’ norms of honour.

Furthermore, we found a high degree of overlap between individual norms of honour and a devaluation of the outgroup characterized by antisemitism and a disapproval of sexual self-determination. This conglomeration of attitudes contradicting western values might be an indicator of a subculture due to segregation (Verkuyten & Yildiz, Citation2007) or an oppositional identity (Fordham & Ogbu, Citation1986; Shrake & Rhee, Citation2004). Deviant norms among culturally diverse subgroups might convert to a code of the street (Anderson, Citation2000), where violence is approved as a response to neighbourhood disadvantages, racial discrimination, and social problems (Stewart & Simons, Citation2006). Given the historical foundations of honour norms (Peristiany, Citation1974), however, a culture-sensitive reading of subcultural theories is definitely required when applied to Turkish or Arab immigrants.

In any case, when it is required to explain how such attitudes become more salient to some individuals than others and which circumstances promote delinquency, specific challenges of acculturation (Phinney, Citation1989) should be kept in mind. Here, the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation2004) provides promising insights that might, in the future, also be incorporated into comprehensive theories of crime. In particular, experiences of rejection by the host society and perceptions of global discrimination may explain the withdrawal into social structures that permit or promote deviant norms. However, perceived individual discrimination showed only small effects, which corroborates previous studies (Brittian, Toomey, Gonzales, & Dumka, Citation2013; Stevens, Veen, & Vollebergh, Citation2014). Our results seem to indicate that some acculturative stressors are less important than others when explaining delinquency. In particular, perceptions of collective disadvantages and discrimination may be connected to delinquency more indirectly than directly.

Practical implications

Generally, our findings suggest that culture-sensitive risk and protective factors may improve common risk assessment procedures because, for most risk and protective factors, significant correlations with delinquency were found. Currently, standardized risk assessment procedures rely on common risk factors that have been mainly studied within the Euro-American context (Hart, Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2002). Sometimes, these instruments show poor predictive power among offenders from diverse cultural contexts (e.g. Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Shepherd et al., Citation2015). Moreover, many risk assessment tools highly depend on verified information about the biography (e.g. previous offences). However, especially among immigrants, such information is often not accessible (Schmidt et al., Citation2018), greatly constraining the use of such tools. Consequently, risk and protective factors that point to attitudes in a culture-sensitive manner and within the actual situation provide a powerful supplement to risk assessment procedures in intercultural contexts. The factors that were tested in this study could be used as an additional checklist by practitioners next to their common risk assessment procedures. As demonstrated in our study, this assessment should thereby stress the social embeddedness. A direct assessment of the social context (for example via home visits) seems promising for two reasons. First, the social context can provide important resources that might not be detected when the assessment only focuses on the individual. According to our results, social support by friends seems to be such an important protective factor. Second, the social context can have a great influence on individual behaviour due to social affordances. Our results show, that the protective power of social support is constrained by the friend’s commitment to norms of honour. Thus, these norms should not only be assessed for the individual person, but also for important others and in the interaction with the important others.

Additionally, risk assessment is essential for planning intervention measures according to the principles promoted by Andrews and Bonta (Citation2010). First, estimating potential risks helps to decide who needs which amount of intervention (risk principle). According to our results, this also should include culture-sensitive factors such as norms of honour. Furthermore, and most importantly, identified risk factors should be tackled in intervention measures to be effective (need principle). Our findings suggest that, among offenders with a Turkish or Arab MB, norms of honour, devaluation of the outgroup, perceived global discrimination, and social support should be addressed in intervention measures. Since we derived these risk and protective factors from theoretical considerations, this may help to design interventions that clearly point to the causes of offending. For example, anti-violence training programmes might be adapted to specific cues and cognitions in honour-related situations. Finally, intervention measures should also incorporate important others and their expectations, as recommended by our results, in order to provide a sufficient responsivity of intervention measures.

Limitations and future directions

Our findings are constrained by some limitations. Most importantly, the sample sizes were unequal and rather small, which might have affected the validity of our findings. Therefore, we highly recommend to replicate our findings. For example, the regression on the severity of delinquency suffered from potential autocorrelations which limit the interpretability of the model. Thus, we were not able to make sound comparisons between the regression models. Further research is needed to examine the validity of these risk factors for different criteria in detail. On these grounds, we were also not able to control for potential confounds, like immigrant generation, age, and education, via complex multivariate analyses with enough power. For example, the number of second-generation immigrants was much higher among offenders compared to non-offenders. This difference may have influenced our results.

Furthermore, conditions for data collection varied in our study, which may have affected the results. The participants from the general population were assessed under varying conditions. Future studies should use more standardized and controlled sampling methods. For example, migrants with a similar background could be assessed in reception centres for immigrants in order to ensure similar acculturation and assessment conditions. Furthermore, the conditions of assessment and compensation for non-inmates and inmates were very different. This differences between inmates and non-inmates are confounded with delinquency as inmates tend to report a greater number of offences and more severe ones. Furthermore, also the incarceration per se might have influenced the results. For example, the importance of others might differ as well as the commitment to attitudes that are associated with subculture inside prison. Thus, further research is needed to investigate the impact of all these confounds more precisely. For example, future studies could examine the commitment to these attitudes at the beginning and at the end of the incarceration controlling for context effects, like the level of security and amount of intervention methods. Moreover, we subsumed different cultural backgrounds in this study, neglecting potential differences in migration histories and specific cultural values. According to our research design, we cannot say if the assumed cultural similarity of participants having a Turkish or Arab MB is greater than the differences between them. Therefore, future research should be more precise about the exact application of culturally shaped values and should take into account potential differences between different cultural contexts in order to analyse the meaning of these aspects. Other studies, for example, may categorize participants according to their cultural value orientation assessed before the primary survey.

In addition, gender may be another important influence that we did not investigated as we focused on males only. However, culture sensitive risk and protective factors need to be considered for woman as well and research is needed to examine these aspects in female samples.

Regarding discrimination and an internal conflict of values, the measures we have used might not be the most appropriate. This might explain our inconclusive results. It is possible that a more specific assessment of different individual discrimination events (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2011) as well as the cognitive and affective reactions to such events (e.g. Noh & Kaspar, Citation2003) might be a better predictor of delinquency. Similarly, the measure of internal conflicts of values, which showed low internal consistency, should be complemented by more complex scales. Thus, future research with more elaborate measures is needed in order to gain deeper knowledge of the discrimination-delinquency relationship. Future studies might also extend our research by using a multi-method approach. This should also include more indirect measures, because social desirability might have biased our results. Social desirability also pertains to the criteria of self-reported delinquency. Using self-reported delinquency is a common practice in criminal psychology (e.g. Stouthamer-Loeber et al., Citation2002), but it has been shown that the correlation of self-reports and official data is lower for minorities than for non-minorities (Asscher et al., Citation2013). Thus, the predictive validity of culture-sensitive risk factors definitely needs to be further examined with official crime data.

In order to really evaluate the possible additional value of culture-sensitive risk factors, a combined examination of these risk factors and commonly valid risk factors is inevitable. Until now, there are only some studies that suggest a limited validity of common risk factors (e.g. Dahle & Schmidt, Citation2014; Schmidt et al., Citation2018) without studying additional factors, and our study that showed a fairly good validity of culture-sensitive risk factors, however, without investigating common risk factors.

In addition, our study only referred to the self-reported delinquency of the past ten years as a criterion. Thus, a prospective longitudinal study design is needed in the future to investigate the predictive validity of these factors. For example, incarcerated offender could be assessed right before their release and official crime data after a follow up of five years could be used as a criterion. A prospective design is also crucial since correlations do not provide information about the cause–effect-relations. For example, perceived discrimination can also be the effect of delinquency due to the contact with the justice system and delinquent others in connection with rationalisations for offending.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding certain limitations of this study, our results provide some of the first comprehensive empirical evidence concerning the validity of risk and protective factors that are sensitive to migration and culture. These factors were derived from intercultural theories and studies, which offer a profound theoretical foundation. A strength of this study is that we investigated many different factors at the same time, which gave insights into their interrelationships. Moreover, it was possible to demonstrate the validity of these factors concerning the severity of delinquency because the sample includes non-offenders as well as serious violent offenders. Thus, our results propose a valid supplement for offender risk assessment – for example as an additional checklist – within intercultural settings.

GPCL-2018-0048_supplement_2ndRevision.docx

Download MS Word (41.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Dilara Isbara, Alaa Khattam, Wael Taha, and Cansu Turhan for translating. Thanks go to Orcun Cinel and Elisabeth Tuturea for assisting the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The original measures used in this study can be provided upon request. Please contact the first author.

References

- Aebi, M. F., Tiago, M. M., & Burkhardt, C. (2015). SPACE I – Council of Europe annual penal statistics: Prison populations: Survey 2014. Strasbourg.

- Aelenei, C., Darnon, C., & Martinot, D. (2016). When school and family convey different cultural messages: The experience of Turkish minority group members in France. Psychologica Belgica, 56(2), 111–117. doi: 10.5334/pb.283

- Albrecht, H.-J. (1995). Ethnic minorities, culture conflicts and crime. Crime, Law and Social Change, 24(1), 19–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01297655

- Algan, Y., Dustmann, C., Glitz, A., & Manning, A. (2010). The economic situation of first and second-generation immigrants in France. Germany and the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal, 120(542), F4–F30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02338.x

- Anderson, E. (2000). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: Norton.

- Anderson, J., & Koc, Y. (2015). Exploring patterns of explicit and implicit anti-gay attitudes in Muslims and Atheists. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(6), 687–701. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2126

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. Cincinnati: Anderson Publishing.

- Arends-Tóth, J., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2008). Family relationships among immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands: The role of acculturation. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 466–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00331.x

- Arnold, S., & Jikeli, G. (2008). Judenhass und Gruppendruck: Zwölf Gespräche mit jungen Berlinern palästinensischen und libanesischen Hintergrunds [Antisemitism and peer pressure: 12 interviews with young people from Berlin with Palestinian and Lebanese decent]. In W. Benz (Ed.), 17. Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung (pp. 105–130). Berlin: Metropol Verlag.

- Arsovska, J., & Verduyn, P. (2007). Globalization, conduct norms and ‘culture conflict': Antisemitism and peer pressure: Perceptions of Violence and Crime in an Ethnic Albanian Context. British Journal of Criminology, 48(2), 226–246. doi:10.1093/bjc/azm068

- Asscher, J. J., Deković, M., Wissink, I. B., van Vugt, E. S., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Manders, W. A. (2013. Ethnic differences in the relationship between psychopathy and (re)offending in a sample of juvenile delinquents. Psychology, Crime & Law, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2012.749475

- Ayçiçegi-Dinn, A., & Caldwell-Harris, C. L. (2011). Individualism–collectivism among Americans:Turks and Turkish Immigrants to the U.S. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(1), 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.006

- Baier, D. (2014). The influence of religiosity on violent behavior of adolescents: A comparison of christian and muslim religiosity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(1), 102–127. doi: 10.1177/0886260513504646

- Baier, D., & Pfeiffer, C. (2008). Disintegration and violence among migrants in Germany: Turkish and Russian youths versus German youths. New Directions for Youth Development, 119, 151-168, 13-4. doi: 10.1002/yd.278

- Baker, N. V., Gregware, P. R., & Cassidy, M. A. (1999). Family killing fields: Honor rationales in the murder of women. Violence Against Women, 5(2), 164–184.

- Baldry, A. C., Pagliaro, S., & Porcaro, C. (2013). The rule of law at time of masculine honor: Afghan police attitudes and intimate partner violence. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(3), 363–374. doi: 10.1177/1368430212462492

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Bauer, S. M., Steiner, H., Feucht, M., Stompe, T., Karnik, N., Kasper, S., & Plattner, B. (2011). Psychosocial background in incarcerated adolescents from Austria, Turkey and former Yugoslavia. Psychiatry Research, 185(1-2), 193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.052

- Beersma, B., Harinck, F., & Gerts, M. J. (2003). Bound in honor: How honor values and insults affect the experience and management of conflicts. International Journal of Conflict Management, 14(2), 75–94. doi: 10.1108/eb022892

- Belhadj Kouider, E., Koglin, U., & Petermann, F. (2014). Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in Europe: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(6), 373–391. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0485-8

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 57(1), 289–300.

- Benjamini, Y., & Yekuteli, D. (2001). The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. The Annals of Statistics, 29(4), 1165–1188.

- Berry, J. W. (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bhutta, M. H., & Wormith, J. S. (2016). An examination of a risk/needs assessment Instrument and its relation to religiosity and recidivism among probationers in a Muslim culture. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(2), 204–229. doi: 10.1177/0093854815604011

- Boiger, M., Güngör, D., Karasawa, M., & Mesquita, B. (2014). Defending honour, keeping face: Interpersonal affordances of anger and shame in Turkey and Japan. Cognition and Emotion, 28(7), 1255–1269. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.881324

- Brettfeld, K., & Wetzels, P. (2007). Muslime in Deutschland. Integration, Integrationsbarrieren, religion und Einstellungen zu Demokratie, Rechtsstaat und politisch-religiös motivierter Gewalt. [ Muslims in Germany. Integration, Barriers to Integration, religion, and Attitudes toward Democracy, Constitutional State, and Politically Motivated Violence]. Berlin: Bundesministerium des Inneren.

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

- Brittian, A. S., Toomey, R. B., Gonzales, N. A., & Dumka, L. E. (2013). Perceived discrimination, coping strategies, and Mexican origin adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Examining the Moderating Role of gender and cultural orientation. Applied Developmental Science, 17(1), 4–19. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2013.748417

- Buda, R., & Elsayed-Elkhouly, S. M. (1998). Cultural differences between Arabs and Americans: Individualism-collectivism revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(3), 487–492.

- Burt, C. H., Simons, R. L., & Gibbons, F. X. (2012). Racial discrimination, ethnic-racial socialization, and crime: A micro-sociological model of risk and resilience. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 648–677. doi: 10.1177/0003122412448648

- Caffaro, F., Ferraris, F., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Gender differences in the perception of honour killing in individualist Versus collectivistic cultures: Comparison between Italy and Turkey. Sex Roles, 71(9-10), 296–318. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0413-5

- Caffaro, F., Mulas, C., & Schmidt, S. (2016). The perception of honour-related violence in female and male University students from Morocco, Cameroon and Italy. Sex Roles, 75(11-12), 555–572. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0576-8

- Campello de Souza, M. G. T., Campello de Souza, B., Bilsky, W., & Roazzi, A. (2016). The culture of honor as the best explanation for the high rates of criminal homicide in Pernambuco: A comparative study with 160 convicts and non-convicts. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 26(1), 114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.apj.2015.03.001

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An “experimental ethnography”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 945–960. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.945

- Cooke, D. J., Michie, C., Hart, S. D., & Clark, D. (2005). Searching for the pan-cultural core of psychopathic personality disorder. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(2), 283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.004

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101.

- Cukur, C., Guzman, M. d., & Carlo, G. (2004). Religiosity, values, and horizontal and vertical individualism-collectivism: A study of Turkey, the United States, and the Philippines. Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 613–634.

- Dahle, K.-P., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Prognostische Validität des level of Service Inventory-Revised. [ Predictive Validity of the Level of Service Inventory – Revised]. Forensische Psychiatrie, Psychologie, Kriminologie, 8(2), 104–115. doi: 10.1007/s11757-014-0256-5

- Danzer, A. M., & Ulku, H. (2011). Integration, social networks and economic success of immigrants: A case study of the Turkish community in Berlin. Kyklos, 64(3), 342–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2011.00510.x

- Dennis, J., Basañez, T., & Farahmand, A. (2010). Intergenerational conflicts among Latinos in early adulthood: Separating values conflicts with parents from acculturation conflicts. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(1), 118–135. doi: 10.1177/0739986309352986

- Dimitrova, R., Chasiotis, A., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2016). Adjustment outcomes of immigrant children and Youth in Europe. European Psychologist, 21(2), 150–162. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000246

- Dwairy, M. (2002). Foundations of psychosocial dynamic personality theory of collective people. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(3), 343–360. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00100-3

- Dwairy, M. (2006). Adolescent-family connectedness among Arabs: A second cross-regional research study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 248–261. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286923

- Enzmann, D., Brettfeld, K., & Wetzels, P. (2004). Männlichkeitsnormen und die Kultur der Ehre: Empirische Prüfung eines theoretischen Modells zur Erklärung erhöhter Delinquenzraten jugendlicher Migranten [ Norm of masculinity and the culture of honour: An empirical validation of a model used to explain causes of the high prevalence of delinquency among young migrants]. In S. Karstedt, & D. Oberwittler (Eds.), Soziologie der Kriminalität (pp. 264–287). Wiesbaden: Verl. für Sozialwiss.

- Eurostat. (2017). Population and population change statistics. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Population_and_population_change_statistics

- Farrington, D. P. (2005). Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(3), 177–190. doi: 10.1002/cpp.448

- Fazel, S., & Bjørkly, S. (2016). Methodological considerations in risk assessment research. In J. P. Singh, S. Bjørkly, & S. Fazel (Eds.), International perspectives on violence risk assessment (pp. 16–25). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Fazel, S., Chang, Z., Fanshawe, T., Långström, N., Lichtenstein, P., Larsson, H., & Mallett, S. (2016). Prediction of violent reoffending on release from prison: Derivation and external validation of a scalable tool. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3, 535–543. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00103-6. online April 13, 2016.

- Fisher, C. B. (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(6), 679–695. doi: 10.1023/A:1026455906512

- Fordham, S., & Ogbu, J. U. (1986). Black students’ school success: Coping with the burden of acting white. The Urban Review, 18(3), 176–206. doi: 10.1007/BF01112192

- Fowler, F. J. (1995). Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Fydrich, T., Sommer, G., Tydecks, S., & Brähler, E. (2009). Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstützung (F-SozU): Normierung der Kurzform (K-14) [ Social Support Questionnaire: Norms of a representative sample]. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Psychologie, 18, 43–48.

- Giguère, B., Lalonde, R., & Lou, E. (2010). Living at the crossroads of cultural worlds: The experience of normative conflicts by second generation immigrant youth. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(1), 14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00228.x

- Glock, S., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers’ judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(1), 111–127. doi: 10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z

- Gutierrez, L., Wilson, H. A., Rugge, T., & Bonta, J. (2013). The prediction of recidivism with aboriginal offenders: A theoretically informed meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 55(1), 55–99. doi: 10.3138/cjccj.2011.E.51

- Harris, R., Tobias, M., Jeffreys, M., Waldegrave, K., Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. (2006). Racism and health: The relationship between experience of racial discrimination and health in New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 63(6), 1428–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.009

- Hart, S. D. (2016). Culture and violence risk assessment: The case of Ewert v. Canada. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 3(2), 76–96. doi: 10.1037/tam0000068

- Hayes, T. C., & Lee, M. R. (2005). The southern culture of honor and violent attitudes. Sociological Spectrum, 25(5), 593–617. doi: 10.1080/02732170500174877

- Heath, A. F., Rothon, C., & Kilpi, E. (2008). The second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 211–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728

- Hilterman, E. L. B., Nicholls, T. L., & van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2014). Predictive validity of risk assessments in juvenile offenders: Comparing the SAVRY, PCL:YV, and YLS/CMI with unstructured clinical assessments. Assessment, 21(3), 324–339. doi: 10.1177/1073191113498113

- Hochstetler, A., Copes, H., & Forsyth, C. J. (2014). The fight: Symbolic expression and validation of masculinity in working class tavern culture. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(3), 493–510. doi: 10.1007/s12103-013-9222-6

- Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hooghe, M., Claes, E., Harell, A., Quintelier, E., & Dejaeghere, Y. (2010). Anti-gay sentiment among adolescents in Belgium and Canada: A comparative investigation into the role of gender and religion. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(3), 384–400. doi: 10.1080/00918360903543071

- Horowitz, R., & Schwartz, G. (1974). Honor, normative ambiguity and gang violence. American Sociological Review, 39(2), 238–251.

- Hutchison, P., Lubna, S. A., Goncalves-Portelinha, I., Kamali, P., & Khan, N. (2015). Group-based discrimination, national identification, and British Muslims’ attitudes toward non-Muslims: The mediating role of perceived identity incompatibility. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(6), 330–344. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12299

- Ingelhart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51.

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., & Solheim, E. (2009). To Identify or not to identify? National disidentification as an alternative reaction to perceived ethnic discrimination. Applied Psychology, 58(1), 105–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00384.x

- Jones, R., Masters, M., Griffiths, A., & Moulday, N. (2002). Culturally relevant assessment of indigenous offenders: A literature review. Australian Psychologist, 37(3), 187–197. doi: 10.1080/00050060210001706866

- Junger, M., & Polder, W. (1992). Some explanations of crime among four ethnic groups in the Netherlands. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 8(1), 51–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01062759

- Junger-Tas, J. (1997). Ethnic minorities and criminal justice in the Netherlands. Crime and Justice, 21, 257–310. doi: 10.1086/449252

- Kaas, L., & Manger, C. (2012). Ethnic discrimination in Germany's labour market: A field experiment. German Economic Review, 13(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00538.x

- Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422. doi: 10.1177/0022022105275959

- Kitayama, S. (2002). Culture and basic psychological processes–toward a system view of culture: Comment on Oyserman et al. (2002). Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 89–96. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.89

- Klink, A., & Wagner, U. (1999). Discrimination against ethnic minorities in Germany: Going back to the field1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(2), 402–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01394.x

- Kogan, I. (2004). Last hired, first fired? The unemployment dynamics of male immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review, 20(5), 445–461. doi: 10.1093/esr/jch037

- Kühnen, U., & Oyserman, D. (2002). Thinking about the self influences thinking in general: Cognitive consequences of salient self-concept. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(5), 492–499. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00011-2

- Kulwicki, A. D. (2002). The practice of honor crimes: A glimpse of domestic violence in the Arab world. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 77–87. doi: 10.1080/01612840252825491

- Lahlah, E., van der Knaap, L. M., Bogaerts, S., & Lens, K. M. E. (2013). Making men out of boys? Ethnic differences in juvenile violent offending and the role of gender role orientations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(8), 1321–1338. doi: 10.1177/0022022113480041

- Le, T. N., & Stockdale, G. D. (2005). Individualism, collectivism, and delinquency in Asian American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 681–691. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_10

- Le, T. N., & Stockdale, G. D. (2011). The influence of school demographic factors and perceived student discrimination on delinquency trajectory in adolescence. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(4), 407–413. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.003

- Liebkind, K., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2016). Acculturation and psychological well-being among immigrant adolescents in Finland. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(4), 446–469. doi: 10.1177/0743558400154002

- Lösel, F. (2003). The development of delinquent behaviour. In D. Carson & R. Bull (Eds.), Handbook of psychology in legal contexts (2nd ed., pp. 245–268). Chichester, Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley.

- Lüdtke, O., Robitzsch, A., Trautwein, U., & Köller, O. (2007). Umgang mit fehlenden Werten in der psychologischen Forschung [ Handling of missing data in psychological research: Problems and solutions]. Psychologische Rundschau, 58(2), 103–117. doi: 10.1026/0033-3042.58.2.103

- Mähönen, T. A., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., & Liebkind, K. (2011). Cultural discordance and the polarization of identities. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(4), 505–515. doi: 10.1177/1368430210379006

- Maitner, A. T., Mackie, D. M., Pauketat, J. V. T., & Smith, E. R. (2017). The impact of culture and identity on emotional reactions to insults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2, 002202211770119. doi: 10.1177/0022022117701194

- Mansel, J., & Spaiser, V. (2013). Ausgrenzungsdynamiken: In welchen Lebenslagen Jugendliche Fremdgruppen abwerten [ Dynamic of exclusion: situations in which adolescences derogate members of the outgroup]. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa. Retrieved from http://www.beltz.de/fileadmin/beltz/kostenlose-downloads/9783779915010.pdf

- Marcell, A. V. (1994). Understanding ethnicity, identity formation, and risk behavior among adolescents of Mexican descent. Journal of School Health, 64(8), 323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb03321.x