ABSTRACT

The Saint Mary's Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) provides an integrated forensic medical and psychological support service, including support through the criminal justice process. The aims of this preliminary exploratory study were to establish the demographic characteristics of clients who self-refer to Saint Mary's SARC (i.e. those who have not been referred by the police), and to explore the nature of alleged assault and alleged perpetrator characteristics across cases. One-hundred and twenty-eight case notes of adult clients (64 police referrals and 64 self-referrals) from a 12-month period were selected for preliminary review and analyses. Results revealed that age, gender and relationship status were similar across both groups. Significant associations emerged, with the majority of self-referred clients being in either full-time employment or full-time education, with no reported additional needs (e.g. physical disability, learning disability). Self-referred clients also reported less information about the nature of the alleged assault and the alleged perpetrator, when compared to police-referred clients. Collectively, these preliminary findings suggest that self-referred clients present with a different case profile and potentially different service needs than those referred by the police. Further research is warranted with larger sample sizes from a wider range of SARCs.

Sexual assault is a prevalent crime that has well-documented negative effects. Research has established severe effects on mental health and psychopathology (for review and meta-analysis, see Dworkin et al., Citation2017), notwithstanding the presence of pre-existing mental health complaints (Manning et al., Citation2019). Sexual assault survivors have a variety of needs which can include emotional support, legal assistance and medical attention (Dworkin & Allen, Citation2018). For these needs to be met, survivors are required to make decisions about who, and when, to disclose information about their experience(s). While sexual assault is generally underreported, research has shown that the majority of survivors do disclose to somebody at some point (Ahrens et al., Citation2010).

Previous research suggests that most disclosures of sexual assault are initially made to informal support providers such as friends, family members and intimate partners (Campbell et al., Citation2015), rather than to formal support providers (Baker et al., Citation2012). Formal support providers are an avenue of disclosure that includes the police as well as services such as sexual assault centres or Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs). Sexual assault centres and SARCs offer multidisciplinary services to those who have experienced sexual offences. Services offered can include medical care for injuries, provision of contraception and testing for sexually transmitted infections. Further, forensic medical examinations may be conducted which includes gathering forensic evidence and documenting forensic samples. Intellectual and mental health needs can also be considered. For instance, many sexual assault centres assess clients for learning disability, history of mental health conditions, as well as current risk of self-harm and suicide ideation. Follow-on care psychological care in the form of counselling can be offered by some centres. Other risks and vulnerabilities may also be assessed and addressed. This may include domestic abuse, and risks associated with the reporting of a sexual assault. Some centres are also positioned to support clients with navigating the criminal justice system (see Eogan et al., Citation2013). In 1986, Saint Mary's became the first SARC to be established in the UK, with an initial remit to provide a medico-legal response to sexual assaults. Forty-seven such centres are now based on the same model in the UK. Saint Mary's SARC has a unique service delivery model whereby it provides a comprehensive and coordinated forensic, Independent Sexual Violence Advisor (ISVA) and counselling service to males and females, and children and adults who have reported sexual assault or rape. Unlike many of the UK's SARCs, Saint Mary's provides a 24/7 service.

Support from sexual assault centres and SARCs is usually offered following a referral being made by the police and a criminal investigation being initiated. In some countries, however, support from centres can be obtained directly, in the form of a ‘self-referral’ (Du Mont et al., Citation2007). This self-referral provision is available at Saint Mary's SARC in the United Kingdom and in other jurisdictions where the legal system allows for sexual assault centres and SARCs to see complainants without the police being involved. Most clients come to Saint Mary's SARC via the police, but about 10% of adults contact Saint Mary's directly and attend without police involvement (self-referral). The benefits of a self-referral system are that persons can access and receive medical and psychological help even if they feel unable to enter the criminal justice process. This is important to many survivors, especially those who may be discouraged from accessing such services if there is a requirement to report the assault to the police (Zinzow et al., Citation2012), but need care for injuries, assessment for risk of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections. A balance between the needs of the individual and public protection concerns will always need consideration.

Few survivors disclose to formal support providers during the acute period of seven days, with many survivors disclosing weeks, months and sometimes years after the assault occurred (Lanthier et al., Citation2018). When reporting does occur within 72 hours of an alleged assault, it is likely to be made to the police or to other formal support services such as sexual assault centres (Ullman & Filipas, Citation2001). Formal disclosure within this time frame typically affords clients of sexual assault centres a broader range of services – largely in the form of addressing physical and evidential needs, i.e. physical evidence collection, medical treatment and acute crisis support. It is well established, however, that regardless of when the assault took place, many survivors require services that do not just address short-term emotional and physical needs, but can also address long-term needs (Young et al., Citation2018). Some centres are positioned to provide these services to clients who present outside of the acute time period and where physical needs may not be appropriate to the clients’ case. As noted, follow-on psychological care in the form of counselling can be offered by some centres (Eogan et al., Citation2013), and a number of centres in the U.K. routinely assess mental health needs (Brooker & Durmaz, Citation2015).

Factors that influence disclosure and responses of sexual assault centres

Disclosures of sexual assault are influenced by multiple factors, some of which interact. Many sexual assault centres can respond by offering services that meet individual client needs, including responding to disclosures considered to be ‘crisis disclosures’ if the person qualifies for an acute forensic medical examination (Ahrens et al., Citation2010). Factors influencing disclosure includes, but is not limited to, the nature of the assault (Ullman, Citation2010), the relationship with the perpetrator (Felson & Paré, Citation2005) and the survivor's age (Nesvold et al., Citation2008). When considering the nature of the assault, help-seeking behaviours and formal disclosures can be affected by a person's perceived seriousness of the assault that they have experienced (Ameral et al., Citation2017; Stoner & Cramer, Citation2019). When sexual assaults include key features of stereotypical assumptions such as stranger rape and serious injury, survivors are more likely to formally report than survivors who experience sexual assault that has fewer ‘stereotypical’ features (Du Mont et al., Citation2003). In such instances, reports are likely to be made to formal services such as the police or sexual assault centres (Ullman & Filipas, Citation2001). For instance, in Norway, those who formally reported assault ‘early’ (defined by the authors as within one week since assault), were more likely to be older (average age of 28 years old) and reported that they had been assaulted by a stranger (Nesvold et al., Citation2008). In contrast, those who formally report sexual assault ‘later’ (‘later’ defined by the authors as longer than one week since assault), were typically younger (average age of 24 years old), and likely to have been assaulted by somebody known and without physical violence (Nesvold et al., Citation2008).

Outside of formal reports to police services, knowledge is limited about the timing of reporting patterns to other formal services in the U.K. However, it is clear that regardless of country, those presenting within an acute time frame are more likely to require specific services relating to medical care and forensic evidence gathering (Eogan et al., Citation2013). While physical health care and gathering physical evidence may not be required for those presenting ‘later’ (after the acute period), many sexual assault centres can provide psychological care to clients, regardless of the time since assault.

When the assault is committed by a person known to the complainant, reporting to the police is less common (Felson & Paré, Citation2005). This trend is amplified when the circumstances of the assault feature the use of alcohol or drugs (Resnick et al., Citation2000; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., Citation2011). Further, those who formally disclosed after a longer time period, are also significantly more likely to be ‘unable to tell’ if the perpetrator was known or unknown, and whether there was one perpetrator or multiple perpetrators (Nesvold et al., Citation2011). Being unable to provide alleged perpetrator information may indeed be a feature that prevents survivors from reporting sexual assault to the police, and thus results in alternative support avenues being explored. For instance, previous research suggests that fear of repercussions and perceived credibility are barriers to disclosure of sexual offending associated with specific settings such as workplaces (McDonald, Citation2012) and university/college establishments (Ameral et al., Citation2017). These barriers may account for employed females who used alternative services but did not report the sexual assault to the police (Jones et al., Citation2009). It is not yet clear whether such characteristics are features of reporting trends for those who self-refer to sexual assault centres in the U.K.

Gender of the survivor is also a key factor. Cis-females and heterosexual females are reported to experience victimisation at a higher rate and are regarded as at increased risk of sexual assault than cis-males, however, research suggests that regardless of gender, assaults occur more frequently in persons aged in their 20s and early 30s (Elliott et al., Citation2004; McLean, Citation2013). Nonetheless, while male sexual assault is not uncommon, patterns of disclosure are different because persons who identify as female are more likely to seek help. For instance, following a telephone survey in Virginia (United States of America), it was reported that 77% of men do not seek help after sexual assault and, when they do, they are less likely to disclose the nature of assault, and such disclosures are rarely made to the police (Masho & Alvanzo, Citation2010). Although knowledge about the impact of gender on patterns of formal disclosures to sexual assault centres is still in its infancy, recent US research has found that, compared to females, males are more likely to use formal channels of support, such as sexual assault helplines, because they perceive there to be limited or no support – including from family, friends and other professionals (Young et al., Citation2018). This pattern may be due to the lack of male-focused service provision in many countries, but in the U.K., some sexual assault centres have recorded growing attendance by males, for example, Saint Mary's SARC, where an increase in police reporting has also been noted (McLean, Citation2013).

Some specific groups are considered to be proportionately more at risk and report proportionally higher rates of sexual assault. These groups include females who do not identify as heterosexual (Ramirez & Kim, Citation2018), and persons who identify as transgendered (Hoxmeier, Citation2016; White & Goldberg, Citation2006). Females with additional needs, such as disability are also regarded to be disproportionately affected by sexual assault (Byrne, Citation2018). There is some emerging empirical evidence about the prevalence of clients with learning disabilities attending sexual assault centres and how services can address particular needs (Majeed-Ariss et al., Citation2020), but little is known about how often specific groups who are considered particularly vulnerable seek initial formal support directly from sexual assault centres, rather than via police services.

The current study

Regardless of the referral method, all sexual assault referrals received by sexual assault centres are considered to be disclosures – indeed ‘crisis disclosures’ if they qualify for an acute forensic medical examination (FME) (Ahrens et al., Citation2010). In Norway, research has explored the usefulness of FMEs in self-referred cases (Nesvold et al., Citation2011), but there is currently no research that has explicitly explored what characteristics distinguish persons who self-refer to those who are referred via the police. More specifically, there is currently no published literature focussing upon patterns of self-referrals in UK SARCs. A lack of research in this area means there is an absence of understanding about the diversity of many clients and their potential needs. Ultimately, this can impact the preventative or reactive interventions available. More broad understanding and identification of support barriers are key to the promotion of service engagement (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2017), especially for those who feel that support may be beneficial.

This study seeks to improve understanding of self-referral clients and associated case characteristics, potentially highlighting areas where greater client support is warranted. Due to the lack of published research in this particular area, our study is exploratory in nature and focusses only on adult clients. This removes any possible confounding variables relating to age and services which are only available to children and young people (those who are 17 years old and under). The aims of the study were as follows:

To establish the demographic characteristics of adult clients who self-refer to Saint Mary's SARC.

To explore the nature of alleged assault and alleged perpetrator characteristics for adult clients who self-refer and clients who are referred via the police.

Method

The study setting

Clients who come into contact with Saint Mary's Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) in the UK are typically referred by the police. In these instances, sexual assault has been reported and a criminal investigation has commenced. Police refer to Saint Mary's all clients who report a rape or sexual assault. Following referral from the police, a Saint Mary's Forensic Physician will triage cases to establish whether or not a forensic medical examination (FME) is needed. On average, over 500 cases are annually referred to Saint Mary's SARC and warrant an FME.

The FME includes: (i) collecting any available evidence including forensic samples, (ii) identifying, documenting and treating any injuries and (iii) assessment for the need of emergency contraception, post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and hepatitis B, as well as screening, where appropriate, for sexually transmitted infections. Mental health needs are also considered, which includes assessing clients for risk of self-harm and suicide ideation. Saint Mary's screens each client for experiences of domestic abuse, regardless of the relationship to the alleged perpetrator of the reported sexual assault. Here, clients are asked about any such history they have, which includes domestic abuse committed by a partner, an ex-partner or a family member. The purpose of this is to establish whether or not there are any additional risks that may make the client vulnerable, other than the risks associated with the reported sexual assault. All clients are offered follow-on services, which includes counselling and access to an Independent Sexual Assault Advisor (ISVA) who can support the client through the criminal justice process, if applicable.

It is important to note that some clients may decline a Saint Mary's referral from the police. However, these data do not get shared with Saint Mary's. Conversely, approximately 18% of clients come into contact with Saint Mary's SARC via an alternative route – by making direct contact and referring themselves for services (without being referred by the police). In these instances, information is gathered directly from the client in the form of an initial and brief account of the alleged assault, including finding out what is alleged to have happened and when. The purpose of collecting information at this stage is to establish which services may be required.

The benefits of this self-referral system are that clients are able to access the above-described services, including a forensic medical examination, followed by medical treatment as appropriate. Psychological support is also offered from counsellors and ISVAs, if self-referral clients feel unable at the point of contact to enter the criminal justice process. However, a proportion of cases do convert to criminal investigations, but these data are not readily available. For cases that do proceed, information gathered may be later used as evidence during criminal investigations and may inform legal decision-making, but samples collected by Saint Mary's are only processed by the police. It is appreciated that the legal system in a number of countries do not allow for services to see complainants without the police being involved. A balance between the needs of the individual and public protection concerns is always considered, but regardless of referral method, all work with clients at Saint Mary's takes place in a non-judgemental and empowering environment.

In this study, self-referral clients at Saint Mary’s are defined as those who have made direct contact with Saint Mary’s and require a forensic medical examination.

Data acquisition and analyses

When clients attend Saint Mary SARC for a forensic medical examination, the forensic physician routinely gathers demographic information as well as details concerning the alleged assault. The forensic physician records these data in the contemporaneous medical notes on Saint Mary's SARC pro forma. Saint Mary's SARC has several forensic physicians in their multidisciplinary team, and each is responsible for recording the above data within a proforma document that forms part of clients’ case notes.

The exploratory analyses in this study are based on retrospective data obtained through 128 case notes of clients who attended Saint Mary's SARC and had an FME. Self-referral clients’ case notes from a 12-month period (April 2014 to March 2015) were selected for review and analyses. This period was selected because at the time of undertaking our unfunded study, this was the most recent data set which was accessible for research. A full 12-month period was used to avoid any potential seasonal variation. These data did not include any information about whether or not self-referral clients later reported to the police.

Based on the above criteria, a total of 64 self-referred client case notes formed the final study sample (the total sum of the adult (aged 18 and over) self-referrals cases which included an FME). Case notes were composed by multiple forensic physicians and this factor was not controlled for. To form a comparison group, sixty-four case notes of adult clients referred by the police were selected based upon the above-mentioned inclusion criteria. As this study aimed to explore potential differences in demographic characteristics, we did not match cases based on these factors. Instead, we selected at random the first five to six cases in each calendar month. This method allowed the sample size to be matched while avoiding any potential selection bias.

Data from the clients’ case notes of both the self-referral group and the police referral group were extracted and coded into categories relating to self-reported characteristics focussing upon demographic information and alleged assault experiences. Demographic information gathered included: (i) age, (ii) gender, (iii) ethnicity, (iv) employment status, (v) marital status, (vi) additional needs, and (vii) distance travelled to Saint Mary's SARC. Alleged assault experiences focused upon: (i) nature of alleged assault, (ii) relationship to alleged perpetrator and (iii) domestic abuse history.

Data were analysed using SPSS software. Where appropriate, Pearson's chi-square tests of association were conducted on nominal level data, and t-tests were applied to continuous level data such as age and distance travelled to Saint Mary's SARC. The Health Research Authority declared that this project is exempt from ethical approval requirements and is service evaluation, since non-generalisable data collected as part of routine care is reviewed retrospectively.

Results

Demographic profile of Saint Mary’s SARC clients

The mean age of all clients in the study sample was 29 years old. Clients who self-referred to Saint Mary's SARC ranged from age 18 to 71 years (M = 30.05, SD = 11.6). Clients who were referred via the police ranged from age 18 to 54 years (M = 29.63, SD = 8.89). An independent samples t-test revealed that there was no significant difference in age between groups, t(125) = 0.231, p = .818.

The majority of clients across both referral groups identified as single, white British females, and this trend remained consistent across referral groups. A total of 20 clients self-reported additional needs. Additional needs were defined as learning difficulties, mobility impairment, deafness, and/or visual impairment. Police referred clients formed the majority of clients who reported having additional needs (N = 15). A significant association was found between referral method and reporting of additional needs, X2 (1, N = 128) = 5.296, p = .015.

We also explored the distance travelled to Saint Mary's by referring to the clients’ reported home address (where available). While the mean distance travelled by clients’ who self-referred (M = 10.05 miles, SD = 14.64 miles) was lower than clients who were referred by the police (M = 14.04 miles, SD = 25.45 miles), however, this difference was not statistically significant (t(119) = −1.065, p = .289). displays the demographic characteristics of clients, presented as a function of referral method. For each characteristic, the percentage of within group (i.e. self-referred vs police referred groups) is presented.

Table 1. Demographic profile of self-referred and police-referred clients.

To further explore associations between demographic characteristics and referral method, Pearson’s chi-square analyses were performed across several variables.

Prior to inferential analyses, data concerning employment status were condensed as (i) ‘employed / in full-time education’ and (ii) ‘not employed / not in full-time education’. A significant association was found between employment / full-time education status and method of self-referral, X2 (1, N = 124) = 17.097, p < .001. Significantly more self-referred clients were employed or in full-time education (N = 49; 39.5% of total cases) compared to clients who were referred via the police (N = 24; 19.4% of total cases). Within the group of police referred clients, the majority (N = 36; 60.0%) were not employed or in full-time education. Four clients referred by the police did not disclose their employment/education status and were excluded from these analyses.

A similar re-categorisation approach was taken with the data concerning relationship / marital status. These data were distributed into one of two categories: (i) ‘single’ and (ii) ‘married/civil partnership/in a relationship’. Across both referral groups, the vast majority of clients were single (N = 100; 82.6%), and this trend was the same within both the self-referred group (N = 50; 84.7%) and the police referred group (N = 50; 80.6%). Seven clients (five self-referred and two police referred) did not disclose their marital status and thus, were excluded from these chi-square analyses. No significant association was found between marital status and referral method, X2 (1, N = 121) = .354, p = .552.

Nature of alleged offence and alleged perpetrator

Data concerning the alleged offences reported by clients were analysed as a function of referral type. Reports of alleged offences were split across three subtypes: (i) ‘rape’: defined in England and Wales as penetration with a penis of the vagina, anus or mouth without consent; (ii) ‘sexual assault’: defined in England and Wales as penetration of a person's vagina or anus with any part of the body, other than a penis, or with any object, without consent. Sexual assault in England and Wales can also include a person being coerced or physically forced to engage in sexual touching against their will, or when a person touches another person sexually without their consent; (iii) ‘not disclosed’: refers to clients who provided no information about the alleged offence, or who suspected that a sexual offence may have occurred but were unsure, and could therefore not provide any details. These data are displayed in .

Table 2. Type of offence reported by self-referred and police-referred clients.

To explore the associations between these variables, Pearson chi-square was conducted. A significant association between the type of offence reported and client group was found, X2 (2, N = 128) = 17.529, p = .001. Here, the majority of clients across both groups reported rape. In contrast to clients who were referred via the police, a larger number of clients who self-referred reported sexual assault. Further, a larger number of self-referred clients did not disclose any information to Saint Mary's SARC about the alleged offence they had experienced (labelled in as ‘not disclosed’).

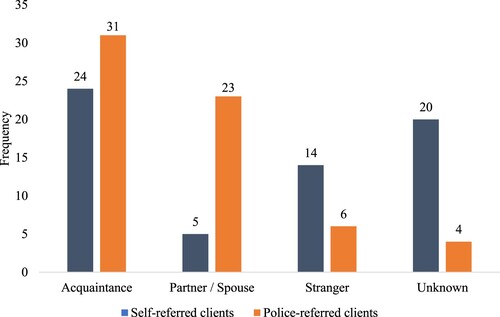

We also explored clients’ relationship to the alleged perpetrator as a function of referral group. A Pearson's chi-square test revealed a significant association between these variables, X2 (4, N = 134) = 27.329, p < .000. Most clients, regardless of referral group, reported the alleged perpetrator to be an acquaintance (N = 55) – see for display of perpetrator relationship as a function of referral group. Differences emerged between groups, for instance, where a larger proportion of police referred clients reported that they were raped or assaulted by their partner/spouse (including ex-partners/spouses). When compared to police-referred clients, more self-referred clients reported the alleged perpetrator to be a stranger. Similarly, more self-referred clients disclosed no information about the identity of the alleged perpetrator (labelled in as ‘unknown’) – this was because they either chose not to categorise the alleged perpetrator type or they were unable to, for example, unconscious.

Domestic abuse history

A total of 48 clients overall (37.5%) reported a history of domestic abuse (which, as defined by Saint Mary's screening procedure, may have been committed by a partner, a former partner or by a family member at any time). Of these clients, 25 attended Saint Mary's reporting a rape or sexual assault which was allegedly committed by a current partner or an ex-partner. However, our data did not include information about whether the same person was responsible for the domestic abuse.

Pearson's chi-square was conducted to test for associations between domestic abuse history and method of referral. The relationship between these variables was significant, X2 (2, N = 128) = 26.029, p < .000. The majority of police-referred clients reported a history of domestic about, but the majority of self-referred clients reported no history of domestic abuse. In the latter, self-referral group, a small proportion chose not to disclose any information about their domestic abuse history. This was in contrast with the police referred clients, where all reported whether or not they had experience domestic abuse in the past. presents these data as a function of the referral group.

Table 3. Domestic abuse history reported by self-referred and police-referred clients.

Discussion

This study aimed to establish the demographic characteristics of clients who self-referred to Saint Mary's SARC, in comparison with clients referred by the police. We also explore the nature of alleged assault and alleged perpetrator differences between referral groups. To do so, we reviewed adult self-referred client case notes and compared them to a sample of adult police-referred clients. Our study was exploratory in nature because the current literature regarding these factors is extremely limited specifically regarding trends in UK sexual assault referral centres. We, therefore, did not present any predictions for our data.

We begin by exploring a key finding which emerged between referral groups. Namely, clients who self-referred to Saint Mary's SARC were typically in full-time employment/education. In contrast, clients who were referred by the police, thus had reported the alleged offence(s) to the police, were typically unemployed – thereby corresponding with demographic characteristics produced by the Office for National Statistics (Citation2021) which only include police-reported crimes. Some evidence exists regarding relationships between employment status, victimisation and help-seeking behaviours. Employment status has previously been revealed as a factor present in the demographic profile of sexual assault and rape clients self-referring for the services of health-related departments. For instance, previous research has found that females who used such services but did not report the sexual assault or rape to the police were typically employed (Jones et al., Citation2009). It is possible that these patterns correspond with some clients’ health status and needs. Figures from earlier research suggest that women who self-reported ill health were the group most likely to report to the police an incident of sexual victimisation (Myhill & Allen, Citation2002). Indeed, 34% of police referred clients at Saint Mary's were not in employment, with a large proportion described as ‘unable to work’.

Our data also revealed that, in contrast to self-referred clients, a larger proportion of police referred clients reported having ‘additional needs’, which included learning difficulties, mobility impairment, deafness, and visual impairment. Overall, the lower proportion of unemployed clients in the self-referral group may reflect clients’ available resource. Indeed, employment status is typically associated with other variables such as financial means, level of education, health and independence. These factors are likely to influence accessibility to Saint Mary's via the self-referral method. At present, Saint Mary's SARC does not routinely record information concerning clients’ financial status and education nor how self-referred clients learn about the pathway. Broader understanding about the help-seeking behaviours that Saint Mary's clients typically adopt, is thus limited in this instance.

Our study also explored the relationship between the client and the alleged perpetrator(s). Clients who self-referred to Saint Mary's typically reported a more distant relationship with the alleged perpetrator. For this group, alleged perpetrators were mostly reported as acquaintances or strangers, and many of these clients disclosed no information about the relationship (either because they did not know or did not want to say). This finding is somewhat in line with previous research where many clients presenting at a sexual assault centre in Norway were unable to report perpetrator details (Nesvold et al., Citation2011), however, in these instances, the time frame since assault and presentation was longer than those who did provide details. Previous research has revealed that persons sexually assaulted by a ‘known’ person are less likely to formally report to the police (Felson & Paré, Citation2005), however, this was not the case in our study because police-referred clients were more likely than self-referred clients to report a relationship with the alleged perpetrator (partner/spouse).

The non-disclosure of alleged perpetrator details by self-referred clients may indeed reflect that perpetrator identities were not known to some clients. It is also possible that many people in this group did not wish to formally disclose any details, but the employment status of our self-referred and police referred clients may be relevant. Previous research suggests that fear of repercussions and perceived credibility are barriers to disclosure in workplace sexual offending (McDonald, Citation2012), and this may account for our rates of stranger and acquaintance assaults reported by self-referred clients. While it would be beneficial to better understand barriers in disclosing perpetrator information in SARCs, individual client needs are paramount. Care needs to be taken so that sexual assault services continue to provide open, accessible, and safe environments. These environments should harbour trust and enable a sense of control for clients where they have full autonomy and flexibility about the details they disclose. Indeed, these are factors that have been noted by survivors who disclose via other formal avenues, such as higher educational institutions (see Holland et al., Citation2020).

As briefly noted already, in contrast to the self-referral group, the police referral group in this study more often reported the alleged perpetrator as being a partner or spouse (including ex-partners). Interestingly, we also found a significant association between history of domestic abuse and method of referral. Clients who were referred via the police and assessed at Saint Mary's SARC were more likely to report such history. It may be the case that, for some clients who did report to the police, their reporting of sexual assault or rape was linked with reporting of domestic abuse, including acts of violence. Acts of violence are likely to warrant medical attention and are perceived by survivors as being more serious in nature (Ameral et al., Citation2017; Stoner & Cramer, Citation2019). However, it is not clear from our data whether the alleged rape or sexual assault was committed by the same person responsible for the domestic abuse which was noted in some clients’ history.

The findings regarding the nature of assault also revealed some referral group differences. More police referred clients reported rape. In comparison, self-referred clients reported more instances of sexual assault or did not disclose any details about the alleged offence(s). It was not clear from our data whether the lack of reported detail was a consequence of clients being unsure about what happened or whether there were other barriers to disclosure. We do know that victims’ belief about the seriousness of the assault is a contributing factor to reporting behaviour. A study published in 2017 found that those who perceived their assault experience as more serious, were more likely to seek help (as per the health belief model) (Ameral et al., Citation2017). Clients at Saint Mary's who self-referred, may have perceived their experience as ‘not serious enough’ to warrant reporting to the police. This perception may link with conceptions about the criminal justice system, and indeed be amplified when assault detail is lacking. Fear of not being believed and lack of confidence or trust in the legal system are known barriers (Taylor & Gassner, Citation2010), but our data do not allow us to draw firm conclusions.

Similarly, while substance use was not explored in this study, previous research has reported that recent alcohol and/or drugs use was a characteristic forming the profile of women who did not report to the police (Myhill & Allen, Citation2002). This factor may go some way in explaining our findings about clients who did not report the alleged perpetrator relationship, or indeed, what the exact nature of the assault was – intoxication may have not only interfered with memory of events, but it may also play a role in clients’ beliefs about the threshold of evidence required to make a report to the police. Further research should explore the relationship between reporting behaviour and offence-associated drug/alcohol consumption of clients who self-refer. This is important because, in 2009, previous research has revealed that environmental factors were primary reasons cited for not reporting to the police, rather than psychological barriers (such as fear, anxiety, and shame; see Jones et al., Citation2009).

The client profiles examined in this study, overall, revealed that users of services at Saint Mary's SARC, regardless of referral method, are typically single, female, and white British. These findings correspond with demographic figures produced by the Office for National Statistics (Citation2021) with regard to victims of sexual offences in England and Wales, but this does not reflect research that suggests that some diverse groups are at higher risk of sexual assault (Byrne, Citation2018; Hoxmeier, Citation2016; Ramirez & Kim, Citation2018; White & Goldberg, Citation2006). Further research which explores disclosure patterns and disclosure barriers of diverse client groups is warranted because without gaining a better understanding, it is possible that many survivors of sexual assault are not able to access support that meets a diverse range of needs.

When exploring the current findings in relation to gender, we know that women with a greater number of traumatic life events formally disclose assault more often (Ullman et al., Citation2008). Our data do not tell us, however, whether our sample of clients had indeed suffered a greater number of traumatic life events, or even whether they had previous history of sexual victimisation before presenting at Saint Mary's. Future research should explore any prior attendance at sexual assault centres because previous victimisation both as an adult, and as a child (occurring before the age of 14), is a risk factor for adult re-victimisation, particularly in younger adults (Humphrey & White, Citation2000). For instance, analyses of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have revealed that sexual victimisation in adulthood is significantly associated with higher ACEs scores. Early adversity, particularly childhood sexual abuse, is a known predictor of risk to adult victimisation (Briere et al., Citation2020; Ports et al., Citation2016). Further, clients at Saint Mary's are known to have high levels of pre-existing mental health complaints (Manning et al., Citation2019), which may potentially correspond with ACEs. Other interacting factors include the additional needs of clients. For instance, it is clear at St Mary's (and more broadly) that learning disability is a known vulnerability amongst those reporting sexual assault (Majeed-Ariss et al., Citation2020), and indeed, a high number of cases referred by police included persons with additional needs.

Limitations and future research

This current study reveals important characteristics of a relatively understudied population of sexual assault complainants, and we have noted some key results which expand knowledge about persons who self-refer to sexual assault centres. Nonetheless, there are several limitations to our research. Our retrospective data of self-referred clients originates from 2014/15 and only concern one sexual assault centre. The cases we examined follow extremely high-profile sexual offence allegations and inquiries in the UK such as Operation Yewtree (Metropolitan Police Service, Citation2012), the police investigation into sexual abuse allegations against Jimmy Savile. However, societal movements via media coverage of high-profile sexual offence allegations and convictions have continued to be publicly documented. It is possible that reporting patterns are further developing, and in new ways. For instance, we know that social media is providing a new platform for disclosure in many countries (Alaggia & Wang, Citation2020; Lin & Yang, Citation2019). These patterns may be revealed with future research in this area, and particular consideration should be given to disclosures at sexual assault centres in other UK SARCs and beyond.

The adult samples used in this study were not matched on demographic characteristics. Because this study was exploratory in nature, and one of our aims was to investigate differences in demographic characteristics across the two referral groups, we did not match the self-referral sample with police referred cases based on demographic characteristics. However, we did control for seasonal variation in referrals across the selected time period. This method reduced selection bias and enabled us to define differences in demographic characteristics. However, future research could adopt a sampling method which matches cases based on demographic information. Such an approach may enable more rigorous exploration of disclosure patterns, allowing for confounding variables to be controlled for. For instance, our data revealed that the majority of clients who come into contact with Saint Mary's are single females under the age of 30. While there were clear differences in the employment status between the two groups, a lack of detail about offences and perpetrators meant that it was not possible to better understand how demographic and offence-related features interact with help-seeking behaviours for clients who self-refer.

Despite some wider demographic patterns emerging, these warrant further investigation. The population is diverse in the areas that Saint Mary's serves, but the present study found that males and ethnic minority groups were less likely to self-refer to Saint Mary's. Although previous research suggests that ethnic minority women were less likely to disclose an assault to the authorities (Ullman et al., Citation2008), it is important to further establish disclosure patterns and barriers across self-referral and police referral clients from differing backgrounds. Such findings may inform future methods of victim engagement with services because the small sample of males and ethnically diverse clients in our study limits what conclusions can be drawn.

There are numerous other factors which warrant further exploration. For instance, examining the time interval between alleged assault and survivors self-referring to Saint Mary's SARC may reveal trends associated with reporting behaviour. Previous research found prolonged time intervals between the assault and forensic evaluation in those who did not report to the police (Myhill & Allen, Citation2002). These persons were typically employed with a recent history of alcohol or drug use. While we explored employment status, we did not explore alcohol or drug use. Nor did we explore pre-existing mental health conditions. These limitations in the current study may be pertinent to explore, especially if combined with gathering greater clarity regarding (i) the exact nature of some offences (including use of coercion) and perpetrator relationships (ii) the specific reasons for non-disclosure of offence and perpetrator information, (iii) the motivations for self-referral, and (iv) the number of self-referral cases which convert to police investigations and court cases. In some instances, it is possible that the timing of self-referral to a sexual assault centre may also be influenced by differences in how centres manage results from forensic examinations. At Saint Mary's results concerning samples are only processed by the police for legal decision-making purposes. It is possible that where practices are different, clients report more (or less) frequently to the police following a self-referral to a sexual assault centre.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights into the characteristics of self-referred clients, as well as their reported experiences. We note that self-referred clients potentially present with differing support needs than those who are referred to Saint Mary's by the police. Whilst the focus of this research has been on the origin of SARC referrals (police or self), it is accepted that for many survivors, reporting sexual offences to the police (or indeed, to any formal service), may not be perceived as appropriate or beneficial. Indeed, the criminal justice system itself may be a source of trauma and/or secondary victimisation (see Patterson, Citation2011). Nonetheless, lack of clarity concerning assault type and perpetrator characteristics is likely to influence the level, type and duration of support more broadly available to this group. Examining how self-referred clients engage with services, as well as gaining a more comprehensive understanding of long-term support needs may assist with the development of appropriate and effective support pathways in sexual assault centres.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

Due to the nature of this research, client case files cannot be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Ahrens, C. E., Stansell, J., & Jennings, A. (2010). To tell or not to tell: The impact of disclosure on sexual assault survivors’ recovery. Violence and Victims, 25(5), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.631

- Alaggia, R., & Wang, S. (2020). “I never told anyone until the# metoo movement”: What can we learn from sexual abuse and sexual assault disclosures made through social media? Child Abuse & Neglect, 103, 104312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104312

- Ameral, V., Palm Reed, K. M., & Hines, D. A. (2020). An analysis of help-seeking patterns among college student victims of sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 5311–5335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517721169

- Baker, L. L., Campbell, M., & Straatman, A. L. (2012). Overcoming barriers and enhancing supportive responses: The research on sexual violence against women. Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children Learning Network. http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/reports/2012-1-eng-LN_Overcoming_Barriers_FINAL.pdf

- Briere, J., Runtz, M., Rassart, C. A., Rodd, K., & Godbout, N. (2020). Sexual assault trauma: Does prior childhood maltreatment increase the risk and exacerbate the outcome? Child Abuse & Neglect, 103, 104421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104421

- Brooker, C., & Durmaz, E. (2015). Mental health, sexual violence and the work of Sexual Assault Referral centres (SARCs) in England. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 31, 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2015.01.006

- Byrne, G. (2018). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with an intellectual disability: A review of the recent literature. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(3), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629517698844

- Campbell, R., Greeson, M. R., Fehler-Cabral, G., & Kennedy, A. C. (2015). Pathways to help: Adolescent sexual assault victims’ disclosure and help-seeking experiences. Violence Against Women, 21(7), 824–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215584071

- Du Mont, J., Miller, K. L., & Myhr, T. L. (2003). The role of “real rape” and “real victim” stereotypes in the police reporting practices of sexually assaulted women. Violence Against Women, 9(4), 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801202250960

- Du Mont, J., White, D., World Health Organization, X., & Sexual Violence Research Initiative, X. (2007). The uses and impacts of medico-legal evidence in sexual assault cases: A global review. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43795

- Dworkin, E. R., & Allen, N. (2018). Correlates of disclosure cessation after sexual assault. Violence Against Women, 24(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216675743

- Dworkin, E. R., Menon, S. V., Bystrynski, J., & Allen, N. E. (2017). Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 56, 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.06.002

- Elliott, D. M., Mok, D. S., & Briere, J. (2004). Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 17(3), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23

- Eogan, M., McHugh, A., & Holohan, M. (2013). The role of the sexual assault centre. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.010

- Felson, R. B., & Paré, P. P. (2005). The reporting of domestic violence and sexual assault by nonstrangers to the police. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 597–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00156.x

- Fitzgerald, K., Wooler, S., Petrovic, D., Crickmore, J., Fortnum, K., Hegarty, L., … Kuipers, P. (2017). Barriers to engagement in acute and post-acute sexual assault response services: A practice-based scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 19(2), 1522–4821. https://doi.org/10.4172/1522-4821.1000361

- Holland, K. J., Cipriano, A. E., & Huit, T. Z. (2021). “A victim/survivor needs agency”: sexual assault survivors’ perceptions of university mandatory reporting policies. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 21(1), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12226

- Hoxmeier, J. C. (2016). Sexual assault and relationship abuse victimization of transgender undergraduate students in a national sample. Violence and Gender, 3(4), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2016.0008

- Humphrey, J. A., & White, J. W. (2000). Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(6), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3

- Jones, J. S., Alexander, C., Wynn, B. N., Rossman, L., & Dunnuck, C. (2009). Why women don't report sexual assault to the police: The influence of psychosocial variables and traumatic injury. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 36(4), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.077

- Lanthier, S., Du Mont, J., & Mason, R. (2018). Responding to delayed disclosure of sexual assault in health settings: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(3), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016659484

- Lin, Z., & Yang, L. (2019). ‘Me too!’: Individual empowerment of disabled women in the# MeToo movement in China. Disability & Society, 34(5), 842–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1596608

- Majeed-Ariss, R., Rodriguez, P. M., & White, C. (2020). The disproportionately high prevalence of learning disabilities amongst adults attending Saint Marys Sexual Assault Referral Centre. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12703

- Manning, D., Majeed-Ariss, R., Mattison, M., & White, C. (2019). The high prevalence of pre-existing mental health complaints in clients attending Saint Mary's Sexual Assault Referral Centre: Implications for initial management and engagement with the Independent Sexual Violence Advisor service at the centre. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 61, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2018.12.001

- Masho, S. W., & Alvanzo, A. (2010). Help-seeking behaviors of men sexual assault survivors. American Journal of Men's Health, 4(3), 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988309336365

- McDonald, P. (2012). Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00300.x

- McLean, I. A. (2013). The male victim of sexual assault. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.006

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2012). Operation Yewtree. http://www.operationyewtree.com/home

- Myhill, A., & Allen, J. (2002). Rape and sexual assault of women: The extent and nature of the problem (pp. 48-50). Home Office. https://doi.org/10.1037/e454842008-001

- Nesvold, H., Friis, S., & Ormstad, K. (2008). Sexual assault centers: Attendance rates, and differences between early and late presenting cases. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 87(7), 707–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340802189847

- Nesvold, H., Ormstad, K., & Friis, S. (2011). Sexual assault centres and police reporting—An important arena for medical/legal interaction. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 56(5), 1163–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01880.x

- Office for National Statistics. (2021). Sexual offences victim characteristics, England and Wales: Year ending March 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/sexualoffencesvictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/march2020#employment-status-and-occupation

- Patterson, D. (2011). The linkage between secondary victimization by law enforcement and rape case outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(2), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510362889

- Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., & Merrick, M. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual victimization in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.017

- Ramirez, M., & Kim, J. (2018). Traversing gender, sexual orientation, and race-ethnicity: Sexual victimization in a population-based sample of older adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 30(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2018.1445054

- Resnick, H. S., Holmes, M. M., Kilpatrick, D. G., Clum, G., Acierno, R., Best, C. L., & Saunders, B. E. (2000). Predictors of post-rape medical care in a national sample of women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 19(4), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00226-9

- Stoner, J. E., & Cramer, R. J. (2019). Sexual violence victimization among college females: A systematic review of rates, barriers, and facilitators of health service utilization on campus. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(4), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017721245

- Taylor, S. C., & Gassner, L. (2010). Stemming the flow: Challenges for policing adult sexual assault with regard to attrition rates and under-reporting of sexual offences. Police Practice and Research: An International Journal, 11(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260902830153

- Ullman, S. E. (2010). Talking about sexual assault: Society's response to survivors. American Psychological Association.

- Ullman, S. E., & Filipas, H. H. (2001). Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assault victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(10), 1028–1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626001016010004

- Ullman, S. E., Starzynski, L. L., Long, S. M., Mason, G. E., & Long, L. M. (2008). Exploring the relationships of women's sexual assault disclosure, social reactions, and problem drinking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(9), 1235–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508314298

- Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Resnick, H. S., Amstadter, A. B., McCauley, J. L., Ruggiero, K. J., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2011). Reporting rape in a national sample of college women. Journal of American College Health, 59(7), 582–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.515634

- White, C., & Goldberg, J. (2006). Expanding our understanding of gendered violence: Violence against trans people and their loved ones. Canadian Woman Studies, 25(1), 124–127. https://cws.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/cws/article/viewFile/5968/5157

- Young, S. M., Pruett, J. A., & Colvin, M. L. (2018). Comparing help-seeking behavior of male and female survivors of sexual assault: A content analysis of a hotline. Sexual Abuse, 30(4), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063216677785

- Zinzow, H. M., Resnick, H. S., Barr, S. C., Danielson, C. K., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2012). Receipt of post-rape medical care in a national sample of female victims. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(2), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.025