ABSTRACT

Research has regularly linked the five-factor model (FFM) or ‘Big Five’ personality model to behaviours, including antisocial behaviour and offending. Three of the five factors, namely, low agreeableness, low conscientiousness and high neuroticism, have consistently been identified as important for explaining offending of males and females. These conclusions have generally been based on considering the FFM as linearly related to offending, when the factors of the FFM could act as ‘risk’ factors (those with extreme negative scores having an increased likelihood of offending) or as ‘promotive’ factors (those with extreme positive scores having a decreased likelihood of offending). In this research the effects of the risk and promotive factors of the FFM on self-reported offending of the male and female children of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD) were examined. The results suggested that many of the factors of the FFM were better considered as promotive factors as opposed to risk factors or mixed (linearly related), and that promotive factors independently predicted offending after controlling for parental, social, socioeconomic and school factors. Limitations, directions for future research, and implications for interventions to reduce offending are discussed.

Introduction

The study of personality and crime has a long history (Berg, Citation1933), and the most influential theory linking these two concepts belongs to Hans Eysenck (Citation1997), who suggested that criminal and antisocial behaviour could be explained by three superordinate personality factors. These were extraversion (E; sensation seeking, venturesomeness), neuroticism (N; anxious, depressed) and psychoticism (P; aggressive, impulsive, unempathic), and those with high E, N and P scores were more likely to be offenders. Empirical support for Eysenck’s hypotheses has been somewhat mixed for E and N (e.g. Farrington et al., Citation1982), while P, which has shown the strongest relationship with offending, could be considered tautologically related, as many items ask about antisocial behaviour (Eysenck et al., Citation1985).

The Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality is currently one of the primary models of conceptualising personality. The FFM was developed using the lexical hypothesis which suggests that all personality traits are encoded in language (e.g. Costa & McCrae, Citation1995). This model is similar to that of Eysenck (Citation1997) as it includes the dimensions of E and N (defined similarly), as well as Agreeableness (A; altruism, modesty), Openness (O; imagination, aesthetic sensitivity) and Conscientiousness (C; self-discipline, competence). Research has suggested that Eysenck’s P is inversely related to both A and C (Costa et al., Citation1991), but these latter scales are not tautological.

There are a number of reasons for examining the relationship between the FFM and offending. This includes the FFM’s very strong empirical foundation, the evidence that personality can change, and the strong association that has been identified between personality and a host of behaviours and outcomes.

Empirical foundation

The FFM itself has a very strong empirical foundation. For example, the factor structure of the FFM has been replicated in a number of different cultures (e.g. McCrae et al., Citation1998) with similar patterns of gender differences identified in various cultures as well (Murphy et al., Citation2021). The factor structure has also been shown to be identical for offenders and non-offenders (Shimotsukasa et al., Citation2019). Taken together these findings suggest that the FFM model of personality could be a human universal, which is further supported by the identification of the corresponding neurological foundations of these factors (DeYoung et al., Citation2010).

In the past personality research has been criticised for its Lombrosian links to biological determinism and extensions of this approach (Prins, Citation1997). Crudely, this approach suggests that those with certain personality characteristics will be offenders and incapacitation is the only way to prevent this. However, current personality research adopts a much more thoughtful probabilistic model; that is, all else being equal, those with certain personality characteristics may be more likely to be offenders than those who do not possess such characteristics. This reasoning is rarely considered as problematic when referring to social factors such as low socioeconomic status or coming from deprived neighbourhoods, in part because there is an assumption that these factors can be changed, and that changes will result in a lower likelihood of offending.

Personality can change

There is evidence that personality, measured using the FFM, has rank-order stability, but also that these factors can change over the life course. Wortman et al. (Citation2012) assessed change and rank-order stability in personality in a nationally representative sample of 13,134 adults in Australia assessed at two time points four years apart. The results suggested a high degree of rank-order stability, with those who were the highest on a personality characteristic at one time point tending also to be the highest at the next time point, but also that this rank-order stability peaked in middle age. Also, Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Openness were found to decline over the life span, while Agreeableness increased among young cohorts, was stable among middle-aged cohorts, and declined among the oldest cohort. Similarly, a study of 1,100 Mexican-origin adults who completed the FFM up to six times across twelve years also found that individuals generally maintained their rank ordering on the FFM over time, and that the rank ordering of the FFM within persons was also highly stable. However, all five factors showed a small linear decrease across adulthood (Atherton et al., Citation2021).

In addition to the natural changes in the FFM that take place as a result of aging, studies have also shown that interventions can influence personality. Roberts et al. (Citation2017) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of personality change through intervention. They identified 207 evaluations that had measured personality change as a result of interventions, including both experimental (i.e. randomised controlled trials) and non-experimental (i.e. pre-, post measures) evaluations over an average length of 24 weeks. The interventions included pharmacological, cognitive–behavioural, supportive/humanistic and mixed approaches. The results showed statistically significant changes in Extraversion (d = .20 - .39), Agreeableness (d = .03 - .23), Neuroticism (d = .39-.69) and Openness (d = .24-.38). External events, such as the Covid pandemic, have also been shown to influence personality (Sutin et al., Citation2020). This means that, if offenders do differ from non-offenders on measures of personality associated with offending, there is the possibility that interventions could result in desirable changes in personality and consequent reductions in offending.

Personality and behaviour

Personality measured by the FFM has been associated with a range of behaviours and outcomes. In systematic reviews the factors of the FFM have been found to be associated with academic performance (Mammadov, Citation2021), resilience (Oshio et al., Citation2018), and second language acquisition (Chen et al., Citation2021). The FFM has also been found to predict psychological wellbeing in the recovery from strokes (Dwan & Ownsworth, Citation2019), as well as prosocial behaviours such as helping (Habashi et al., Citation2016) and volunteering (Carlo et al., Citation2005). The FFM has also been linked to antisocial behaviours such as gambling, addiction and academic dishonesty (Dash et al., Citation2019; Giluk & Postlethwaite, Citation2015), suggesting potential links with criminal behaviour.

A limited number of studies have compared the FFM to offending. For example, Pulkkinen et al. (Citation2009) examined the FFM, administered to a group of 196 Finnish males at age 42, in relation to a combined measure of self-reported and official offending from ages 15–42. The results showed that those who committed offences both before and after age 21 (persisters) had significantly higher Neuroticism, lower Agreeableness and lower Conscientiousness than those who had not committed offences. In addition, those who had committed offences only before the age of 21 had higher Neuroticism and lower Agreeableness than those with no offences, while those who had committed offences only after age 21 had higher Extraversion and Neuroticism.

O’Riordan and O’Connell (Citation2014) examined the association between the FFM and retrospective reports of criminal justice contacts in a large national sample (n = 7205) of males and females from England, Wales and Scotland. The FFM was administered when the sample was about age 50, and offending was assessed by asking the sample if they had received any criminal justice sanctions in the last decade. The results suggested that offending was associated with significantly higher extraversion, and significantly lower agreeableness, neuroticism, and conscientiousness. Gender and school problems were also independently associated with offending, but a host of other individual and social factors (e.g. academic attainment, large family size, paternal social class, occupational status) were not.

Slagt et al. (Citation2015) examined the relationship between personality, measured using the FFM, a friend’s self-reported delinquency (as perceived by the target child and also based on the friend’s actual reported delinquency) and self-reported offending one year later, in a sample of 177 predominantly female Dutch adolescents (Av. age = 15.5). The results showed that the perceived delinquency of friends predicted a stronger increase in adolescent delinquency 1 year later, especially among adolescents with low or average levels of conscientiousness. It is often difficult to disentangle self-reported delinquency from peer delinquency as much offending at young ages is committed in groups (Carrington, Citation2009). In addition, within-individual analyses have shown that peer delinquency is much more likely to be a correlate of offending as opposed to a cause of offending (Farrington et al., Citation2002).

Using the Pathways to Desistence study, a prospective study of 14 -17 year-old adjudicated delinquents or those convicted of a felony in Phoenix, Arizona or Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Walters (Citation2018) examined the relationship between the FFM and desistance 6–60 months later. The sample of 1126 predominantly non-white male participants were between the ages of 16 and 21 (M = 18.1, sd = 1.2) at the time they completed the FFM personality assessment. This was then compared to later self-reported offending (both variety and frequency), controlling for the time to accrue these offences. The result suggested that Agreeableness was the only factor that was significantly associated with desistance, again highlighting the potential importance of this factor in explaining offending.

Systematic reviews have generally suggested that antisocial and aggressive behaviour are more strongly associated with low agreeableness and low conscientiousness, and less strongly associated with high neuroticism, low openness, and high extraversion (Jones et al., Citation2011; Miller & Lynam, Citation2001).

Unfortunately, most studies have been based only on males or mixed samples, making it a challenge to determine whether the relationships between the FFM and offending are similar for males and females. Hines and Saudino (Citation2008), however, explored how the FFM was related to self-reports of intimate partner aggression amongst 179 male and 301 female undergraduates. For males, higher Neuroticism and Extraversion, as well as lower Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, were associated with the perpetration of various forms of intimate partner aggression. For females, only higher Neuroticism was significantly associated. Similarly, a study of 254 young Croatian secondary school students (54% female, mean age = 16.2) found that males had significantly greater Extraversion, Neuroticism and Openness than females and significantly lower Agreeableness, while also being more likely to self-report delinquency (Ljubin-Golub et al., Citation2017). When the relationship between the FFM and delinquency was examined separately for males and females the results suggested that, when controlling for age and SES, females who reported offending had significantly higher Extraversion and Neuroticism while males who reported offending had significantly lower Agreeableness.

There is evidence that particular personality features measured early in life can influence the likelihood of criminal behaviour many years later. For example, using a sample of 540 male Swedish school children followed up from age 14–26 af Klinteberg et al. (Citation1993) found that hyperactive behaviour (a combined measure of concentration difficulties and motor restlessness and an important component of Extraversion) was strongly associated with both later alcohol problems and convictions for violence. Similarly, Eklund and af Klinteberg (Citation2003) examined the relationship between childhood hyperactivity and later alcohol problems and violence in a sample of 192 males aged 11–14 who had received convictions as well as 95 nonoffending matched control children. The results showed that, by age 35, those who had a particular component of hyperactivity, namely attention difficulties (i.e. teacher rated lack of attention and concentration) were significantly more likely to have alcohol problems and convictions for violence, controlling for early aggressive behaviour.

Could the FFM be promotive for low offending?

Theoretically and empirically, the link between personality and offending has almost exclusively been conceptualised as linear; that is, those with low Agreeableness, for example, are considered more likely to commit offences than those with medium levels, and those with medium levels are considered more likely than those who have high Agreeableness. Each of the five factors of the FFM could be linearly related to offending, but alternatively, they may be better conceptualised as non-linearly related, and as risk or promotive factors. There is a considerable amount of confusion about the terminology associated with risk and promotive factors, the latter of which is often confused with protective factors (see Jolliffe et al., Citation2016), which are defined as those which interact with a risk factor to negate its impact (Rutter, Citation1985).

Loeber et al. (Citation2008) addressed these definitional issues by proposing that a variable which predicted a low probability of offending should be termed a promotive factor, while a variable that predicted a high probability of offending should be termed a risk factor. A mixed factor is one that is linearly related to offending. In order to determine whether a variable is a risk factor, a promotive factor or a mixed factor, these ideas must be empirically tested. One approach is to trichotomise a variable into the ‘worst’ quarter (e.g. low Agreeableness) the middle half, and the ‘best’ quarter (e.g. high Agreeableness) and compare both the risk end and the promotive end of the same variable to offending. If a variable is linearly related to offending, so that the percent offending is low in the best quarter and high in the worst quarter, then that variable could be regarded as both a risk and promotive factor, or what Loeber et al. (Citation2008) referred to as a mixed factor. However, if the percent offending is high in the worst quarter, but not low in the best quarter, that variable would be regarded as a risk factor. Alternatively, if the percent offending is low in the best quarter but not high in the worst quarter, that variable could be regarded as a promotive factor (see Farrington & Ttofi, Citation2011).

This approach is not the only way that non-linear effects could be examined (e.g. generalised additive models, quantile regression; Beller & Baier, Citation2013), but trichotomising is a more easily understood approach, and also makes the results more obvious. In addition, this approach has been used in a number of studies (e.g. Jolliffe et al., Citation2016; Loeber et al., Citation2008) to illustrate that many factors commonly conceptualised as risk factors, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, may better be considered as promotive factors. Practically this means that interventions which aim to address ADHD should include both those who have high levels of ADHD and those who have mid-range levels, as only those with low levels of ADHD have a low likelihood of offending.

The current study is the first of which we are aware that empirically tests whether the factors of the FFM may be promotive in predicting a low likelihood of offending and comparing males or females. In addition, this study examines whether these personality factors are related to offending independently of parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors.

Method

Participants

Data for this study was obtained from the children (the generation 3 or G3 sample) of the men from the famous Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD). The CSDD began in 1961 and is a prospective longitudinal study of 411 South London males (generation 2 or G2) followed up from age 8 to age 48, with 9 repeated face-to-face interviews and assessments. More information about this seminal study can be found in books (e.g. Farrington et al., Citation2013; Piquero et al., Citation2007) and summary articles (Farrington, Citation2019; Citation2021; Farrington et al., Citation2021). The CSDD males (the G2 sample) were overwhelmingly a traditional White, urban, working-class sample of British origin.

There were 691 G3 children whose name and date of birth were known. Only children aged at least 18 (born up to 1995) were targeted for interviews (2004-2013). The ethical requirements of the South-East Region Medical Ethics Committee required that we contact the G2 male and/or his female partner in trying to interview the G3 children and that we only interviewed G3 children aged at least 18. Twenty children whose fathers refused at age 48, and 7 children whose father was dead at age 48 (and where no female partner was available) were not eligible to be interviewed. An additional six G3 males who had died and three who were disabled (one Down’s syndrome, one mental health problems, one severe attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder), together with two who did not know that the G2 male was their father, were considered to be not eligible.

Of the 653 eligible G3 children, 551 were interviewed (84.4%), including 291 of the 343 G3 males (84.8%) and 260 of the 310 G3 females (83.9%). Of the remainder, 39 children refused, 33 parents refused, 13 children could not be traced, 14 were elusive (agreeing or not refusing but never being available to interview), and 3 were aggressive or problematic. Of the 29 children living abroad, 17 were interviewed, usually by telephone. The G3 children were interviewed at the average age of 25, and most were aged between 23 and 27. The mean age interviewed was similar for the 291 males (25.6) and the 260 females (25.4).

Measures

Personality

The Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, Citation1999) was used to assess personality in this sample. This 44-item scale was designed to assess the five domains of personality (Extraversion (E), Neuroticism (N), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C) and Openness (O)) by asking respondents to indicate how much each of the statements describes them. The Cronbach alpha coefficients for the entire sample were: E = .80, A = .64, C = .62, O = .78, N = .73.

Self-reported offending

Participants were asked whether they had committed any of the following offences in the last five years: burglary, theft of a vehicle, shoplifting, theft from a vehicle, theft from a machine, vandalism, assault, drug use (Class A and Class B, including cannabis), drunk driving, theft from work, and fraud (see also Farrington & Jolliffe, Citation2021). Over 87% of the males (255/291) admitted at least one offence, compared to 46.3% of females (173/260). This difference was statistically significant (chi squared = 35.2, p < .0001, OR = 3.6). Because of the large proportion of both males and females who self-reported offences, this variable was dichotomised into the ‘worst’ 25%, reporting the greatest variety of offences (the ‘offenders’), and the remaining 75% (the ‘non-offenders’), for males and females separately. For males this was 69 out of 291 (23.7%), and for females this was 83 out of 260 (31.9%).Footnote1

There were a number of reasons for adopting this approach with offending. First, this approach identifies the highest frequency offenders and therefore those most likely to be the most serious offenders (e.g. Farrington, Citation1998). This also accounts for the fact that in self-reported surveys offending is often normative, with most individuals reporting at least some self-reported offending (Farrington et al., Citation2001). In addition, the self-reported offending scale was not normally distributed, so arguably required transformation. Finally, studies which have compared the results of analyses using both continuous and dichotomous variables show similar results with very limited loss of information (e.g. Farrington, Citation2020; Farrington & Loeber, Citation2000).

Males and females were separated in this study because there are relatively few studies which have specifically examined whether the personality features of the FFM may be differently associated with offending for males and females. Comparatively, there is much less research conducted on factors associated with female offending, but the that research which has been conducted has shown that female offending may be explained by different factors from male offending (Blanchette & Brown, Citation2006). It is important to examine these potential mechanisms separately to develop evidence about female offending (Van Voorhis, Citation2012).

The ages of the males and females were not significantly associated with the measure of self-reported offending, and so were controlled in the analyses.

Parental, family, social and school risk factors

Data on parental, family, social and school risk factors for G3 children were available from both the G2 males (when the fathers were aged 32), and from the G3 children themselves. From the G2 males these were: having a convicted father or motherFootnote2, having an authoritarian father, having a young father or mother, physical punishment, poor parental supervision, parental conflict, being separated from the child, low take-home pay, large family size, poor housing, and low social class. From the G3 children these were: physical punishment, poor parental supervision, separated from the father, early school leaving and leaving school with no A Levels. (For more information about these variables, see Farrington et al., Citation2015).

Research Questions:

How does self-reported offending relate to the factors of the FFM when using the risk/promotive approach and the typical approach for males and females separately?

How does self-reported offending relate to the parental, family, social and school risk factors for males and females separately?

Are there independent relationships between self-reported offending and the significant personality factors using the risk/promotive approach, controlling for the parental, family, social and school risk factors for males and females separately?

How well do the identified independent factors predict self-reported offending using the area under the curve of the receiver operator characteristicFootnote3?

How would the results differ if personality had been conceptualised as a continuous variable?

Analytic Approach:

Bivariate statistics (and corresponding odds ratios) were used to examine compare the relationship between FFM and gender (t-tests) and also to examine the relationship between the promotive, middle and risk ends of the FFM with self-reported offending (chi square tests). This relationship was also examined using Pearson correlations. Chi square tests were also used to explore the relationship between the parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors with self-reported offending for males and females. Finally, two logistic regressions were used to identify which (if any) personality features were independently associated with self-reported offending controlling for the significant parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors.

Of the 291 males, full data was available for 276 and of the 260 females, full data was available for 259.

Results

shows the means and standard deviations for the Big Five personality dimensions for males and females. For example, males scored an average of 28.6 (sd = 5.5) on E, compared to 29.7 (sd = 5.8) for females. This difference was statistically significant (t = 2.3, p < .003, OR = 1.4) suggesting that females in this sample were higher on E .Footnote4 Females were also found to score significantly higher on A, C and N, while males scored significantly higher on O. Because of the gender differences in offending and in personality composition, all subsequent results for males and females were examined separately.

Table 1. Big five personality dimensions for males and females.

The first column of shows the Pearson (r) correlation between the FFM and self-reported offending for males and females. Agreeableness was significantly and negatively related to offending for both males (r = -.16, p < .01) and females (r = -.22, p < .01), while neuroticism was positively related (r = .18 and r = .19, p < .01 for both). Conscientiousness was significantly and negatively related for females (r = -.19, p < .01), but this comparison was not quite significant for males (r = -.12).

Table 2. Five-factor model of personality and percent with self-reported offences.

Empirical tests were conducted to determine whether the components of the FFM were best considered as risk, promotive, or mixed factors. This was done by trichotomising each factor into the ‘worst’ quarter (e.g. low Agreeableness), the middle half, and the ‘best’ quarter (e.g. high Agreeableness) and this was then compared to offending. The results can be seen in , which shows the percentage of males and females who self-reported offences in the promotive, middle and risk categories of each of the five factors. For example, just under 16% of the males who had high agreeableness self-reported an offence, while this was true of 20.6% of those with middle levels of agreeableness and 38% of those with low agreeableness. The comparison between the promotive and middle resulted in a non-significant odds ratio of 1.4, while between the middle and risk the OR was a significant 2.4, suggesting that Agreeableness was a risk factor that was significantly related to offending. In contrast, only 9.5% of males with low Neuroticism self-reported an offence, compared to 26.7% with middle levels and 31.3% with high Neuroticism. Comparing the promotive and middle categories resulted in a significant odds ratio of 3.5, while comparing the middle with the risk end resulted in a non-significant odds ratio of 1.4, suggesting that low neuroticism was a promotive factor for a low likelihood of offending. Extraversion was non-linearly related to offending in males.

For females, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness were found to be significant promotive factors associated with a low likelihood of offending, as was Neuroticism. Openness and Extraversion were non-linearly related to offending in females.

shows the relationship between the parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors and offending for males. For example, out of the 177 males whose father had not been convicted, only 33 were offenders (18.6%), compared to 36 out of 107 whose father had been convicted (33.6%). This was equivalent to an odds ratio of 2.2 (p < .01). The risk factors that were significantly associated with self-reported offending in males included having a convicted father, the child’s report of physical punishment, the child’s report of poor parental supervision, the father’s report of being separated from the child, living in poor housing and leaving school with no A Levels. There was evidence from the magnitude of the odds ratios that having a convicted mother (OR = 2.2), having a father with low take home pay (OR = 1.9, p < .10), and, counterintuitively having an involved father (OR = 2.5, the inverse of OR = 0.4), were also potentially associated with offending.

Table 3. Parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors versus self-reported offending in males.

The results for females (see ), showed that the risk factors that were significantly associated with self-reported offending were the child’s report of poor parental supervision (OR = 2.7), the child’s report of being separated from their parent (OR = 2.0), and leaving school early (OR = 2.6). The magnitude of the relationships between self-reported offending and having a convicted mother (OR = 1.9), the father’s report of being separated from the child (OR = 1.7), and leaving with no A Levels (OR = 1.7), suggested that these were also potentially associated with offending.

Table 4. Parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors and self-reported offending in females.

FFM and predicting offending in males

Forward stepwise logistic regression analyses were used to examine whether the FFM dimensions were independently related to self-reported offending after controlling for the significant relationships with parental, family, socioeconomic and school risk factors (). For males, offending was the dichotomous outcome variable, while Agreeableness (risk), Neuroticism (prom), convicted father, physical punishment (child), poor supervision (child), separated from child (father), poor housing (father) and no A Levels (child) were the explanatory variables.

Table 5. Independent predictors of offending.

The results suggested that low agreeableness (LRCS = 13.2, p < .0001) was a significant predictor of offending, as was having a convicted father (LRCS = 9.2, p < .002), the child’s report of physical punishment (LRCS = 5.0, p < .03) and the father’s report of being separated from the child (LRCS = 4.4, p < .04). Low neuroticism (LRCS = 9.3, p < .002) significantly predicted a reduction in offending, with a partial odds ratio of 0.15 (.05 – .48).

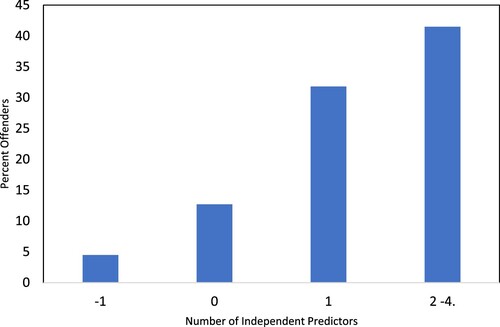

Each of the significant variables was coded as 1 if present and 0 if not present, except for low Neuroticism which, being promotive of a low likelihood of offending, was scored as −1 if present. These scores were then summed and compared to the percent of offenders (). Just under 5% of males who only had low neuroticism (−1) had self-reported offences, while those who scored zero (either none of agreeableness (risk)), convicted father, physical punishment, separated from parent, or one of these and low neuroticism) had a prevalence of offending of 12.7%. Those who had between 2 and 4 of the independent predictors had a prevalence of 41.5%.

When this risk score was compared to offending in males, the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was found to be 0.70 (0.63-0.77, se = .035). The AUC is a measure of predictive validity of a risk score and ranges from 0.5 (chance) to 1.0 (perfect prediction). An AUC of 0.70 is similar in range to the validity of tools designed to predict reoffending (e.g. Farrington, Jolliffe & Johnstone, Citation2008), indicating that these five variables are strongly associated with offending.

FFM and predicting offending in females

The factors that significantly predicted female offending were examined using the same procedure. Self-reported offending (dichotomous) was the outcome variable, while extraversion (prom), agreeableness (prom), consciousness (prom), poor supervision (child), separated from child (child), and early school leaving (child), were the explanatory variables. The results are shown on the bottom of and suggested that high agreeableness (LRCS = 12.7, p < .0001), the child’s report of poor supervision (LRCS = 11.6, p < .001), and the child’s report of being separated from her father (LRCS = 5.4, p < .02) were significant predictors of self-reported offending in females.

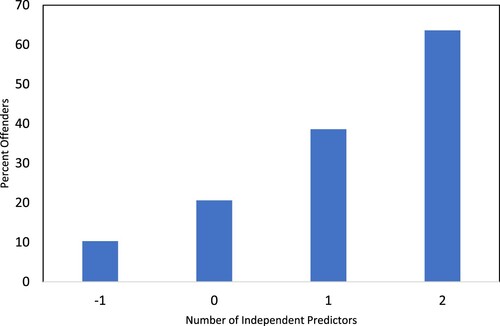

As with males, a prediction score was created by coding each independent factor as present (1) or absent (0), except for high agreeableness which was coded as −1 if present because this predicted a low probability of offending. shows that females who only had high agreeableness (−1) had a prevalence of offending of about 10%, while those who did not have poor parental supervision or were not separated from their father (or had either of these and high agreeableness) and had a score of 0 had a prevalence of over 20%. About 64% of females who had both poor parental supervision and were separated from their father, but did not have high agreeableness, reported offences. This was equivalent to an area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) of 0.69 (0.62-0.76, se = .035), again suggesting a strong relationship between these three variables and offending.

Predicting offending taking a linear approach

The logistic regressions were repeated for both males and females as described above, but instead of including the significant FFM factors as dichotomised promotive or risk factors, they were included in their continuous form. The results for males suggested that Agreeableness (LRCS = 9.4, p < .002, Exp (B) = .91, .84-.98) and Neuroticism (LRCS = 5.3, p < .02, Exp (B) = 1.08, 1.0 = 1.15) were again the only personality factors to significantly predict offending. For females, Agreeableness (LRCS = 13.6, p < .0001, Exp (B) = .91, .86-.96) was again the only personality factor to significantly predict offending.

Interpreting these results, one would draw the conclusion that, for both males and females, Agreeableness was negatively associated with offending. However, the results of the promotive approach indicate that this conclusion is imprecise. While it was true that males with low Agreeableness had a higher likelihood of offending, males who had moderate Agreeableness were not more likely to offend than those with high Agreeableness. For females, it was not that those with low Agreeableness were more likely to offend (as those with middle levels were equally likely), but that those with high agreeableness were significantly less likely to offend.

Discussion

This paper examined the relationship between FFM personality scales and self-reported offending for a UK community sample. As found in much previous research, the results suggested that males and females differed significantly in their levels of offending and also in their relative levels of the factors of the FFM (e.g. Jolliffe, Citation2013). Despite these relative differences, the link between personality and offending has often been considered to be similar for males and females, with low agreeableness, low conscientiousness and high neuroticism most commonly implicated (e.g. Eysenck, Citation1997; Jones et al., Citation2011; Miller & Lynam, Citation2001). Taking the traditional linear approach, this research generally replicated these findings, but the conclusion that the relationship between personality and offending is similar for males and females would be incorrect.

A key finding of this study was that many of the dimensions of the FFM may be better considered as promotive factors, which reduce the likelihood of offending, rather than risk factors which increase it, or the more typical mixed (or linear) factors. For males, low Neuroticism was associated with a lower likelihood of offending, and for females, high Agreeableness, high Conscientiousness and low Neuroticism were promotive. This finding is of considerable theoretical and practical importance as, when looking for those more likely to offend, it changes the focus from looking at only the risk end of these factors to looking at both the risk and middle categories.

For both males and females there was evidence that the FFM was related to offending. For females, not all factors of the FFM that were related to offending in univariate analyses were significant predictors of offending when a range of parental, social, socioeconomic and school factors were controlled. For example, Conscientiousness (prom) was significantly associated with offending in females but was not independently related. Interestingly, for males this was not the case, and both of the personality features that were identified, low Agreeableness and high Neuroticism, were also independently related to offending.

Overall, the results suggest that personality may have a role in contributing to (or preventing, in the case of promotive factors) offending, but that parental and family factors are still important in explaining offending. For females, the non-personality factors associated with offending were those indicative of an absence of parental attention (separation, poor supervision). For males there was some evidence of this (father’s report of separation), but offending was also predicted by factors indicative of a negative parental presence in having a convicted father and having been physically punished. In support of this assertion, when the relationship between uninvolved fathers (significantly related to SR offending, see ), father’s convictions and son’s SR offending was examined, the results showed that father’s convictions were related to son’s SR offending when the father was involved (OR = 2.7), but not when the father was uninvolved (OR = 1.0).

Whether a variable acts as a risk or promotive factor has significant implications for interventions designed to prevent or reduce offending. If a variable acts as a risk factor, interventions should aim to reduce it. If a variable acts as a promotive factor, interventions should aim to increase it. Different interventions are likely to be needed to reduce or increase particular factors. Aiming to enhance a promotive factor is a more positive approach, and may be more acceptable to potential participants, than aiming to reduce a risk factor, which focuses on negative features of individuals and families.

Limitations

This research has limitations which need to be considered when interpreting the results and drawing conclusions. First, data on personality and self-reported offending were collected concurrently, so it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about temporal ordering. Personality may influence offending, but equally offending, and the implications of offending, may influence personality. Also, given the strengths and weaknesses of self-reported offending (Jolliffe & Farrington, Citation2014), future research should use different measures of offending (e.g. official convictions), and other measures of criminal careers (e.g. age of onset, criminal career duration). It is also very important to empirically test whether the important relationships identified in this research exist for persons from more diverse backgrounds. It is being progressively appreciated that the cultural experiences of marginalised groups may result in different causal mechanisms linking personality and crime (e.g. Glynn, Citation2014; Jolliffe et al., Citation2016).

Conclusions

Personality and the FFM may contribute to our understanding of criminal and antisocial behaviour in both males and females. It is important that the common assumption of linear relationships between personality and offending is empirically tested in future research. This study found that many of the factors of the FFM were promotive factors predicting a lower likelihood of offending. This has theoretical implications for considering the link between personality factors and crime and practical implications for considering who may be likely to commit offences in light of their personality structure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, D.Jolliffe, upon reasonable request.

Notes

1 While above the target of 25%, the alternative of 44 out of 260 (16.9%) was considered too few.

2 Based on criminal records.

3 The Area under the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve (AUC; see Swets, Citation1986) is considered a strong measure of predictive accuracy. The ROC curve plots the probability of a ‘hit’ or true positive (the fraction of offenders identified at each cut-off point) against the probability of a false positive (the fraction of nonoffenders identified at each cut-off point).

4 The odds ratio (OR) is a measure of effect centred around 1.0, and as a rule of thumb odds ratios of 2.0 (a doubling of the effect), or 0.5 (a halving of the effect) are considered large (Cohen, Citation1996).

References

- af Klinteberg, B., Andersson, T., Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (1993). Hyperactive behavior in childhood as related to subsequent alcohol problems and violent offending. Personality and Individual Differences, 15(4), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90065-B

- Atherton, O. E., Sutin, A. R., Terracciano, A., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Stability and change in the Big Five personality traits: Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin adults. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000385

- Beller, J., & Baier, D. (2013). Differential effects: Are the effects studied by psychologists really linear and homogeneous? Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v9i2.528

- Berg, L. (1933). The criminal personality. In L. Berg (Ed.), The human personality (pp. 222–235). Prentice Hall/Pearson Education. https://doi.org/10.1037/11041-012

- Blanchette, K., & Brown, S. L. (2006). The assessment and treatment of Women offenders: An integrated perspective. Wiley.

- Carlo, G., Okun, M. A., Knight, G. P., & de Guzman, M. R. T. (2005). The interplay of traits and motives on volunteering: Agreeableness, extraversion and prosocial value motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(6), 1293–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.012

- Carrington, P. J. (2009). Co-offending and the development of the delinquent career. Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal, 47(4), 1295–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00176.x

- Chen, X., He, J., Swanson, E., Cai, Z., & Fan, X. (2021). Big Five personality traits and second language learning: A meta-analysis of 40 years’ research. Educational Psychology Review, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09641-6

- Cohen, P. (1996). Childhood risks for young adult symptoms of personality disorder: Method and substance. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 31(1), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3101_7

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Primary traits of Eysenck’s P–E–N system: Three and five-factor solutions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(2), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.308

- Costa, P. T., McCrae, R. R., & Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO personality inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(9), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90177-D

- Dash, G. F., Slutske, W. S., Martin, N. G., Statham, D. J., Agrawal, A., & Lynskey, M. T. (2019). Big Five personality traits and alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and gambling disorder comorbidity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000468

- DeYoung, C. G., Hirsh, J. B., Shane, M. S., Papademetris, X., Rajeevan, N., & Gray, J. R. (2010). Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the big five. Psychological Science, 21(6), 820–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610370159

- Dwan, T., & Ownsworth, T. (2019). The Big Five personality factors and psychological well-being following stroke: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(10), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1419382

- Eklund, J., & af Klinteberg, B. (2003). Childhood behaviour as related to subsequent drinking offenses and villent offending: A prospective study of eleven to fourteen-year-old youths into their fourth decade. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 13(4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.552

- Eysenck, H. J. (1997). Personality and crime: Where do we stand? Psychology, Crime & Law, 2(3), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169608409773

- Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(85)90026-1

- Farrington, D. P. (1998). Predictors, causes and correlates of male youth violence. In Tonry, M. and Moore, M. H. (Eds.), Youth Violence (Crime and Justice, vol. 24) (pp. 421–475). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Farrington, D. P. (2019). The Cambridge study in Delinquent development. In D. Eaves, C. D. Webster, Q. Haque, & J. Eaves-Thalken (Eds.), Risk rules: A practical guide to structured professional judgment and violence prevention. Hove (pp. 225–233). Pavilion Publishing.

- Farrington, D. P. (2020). Childhood risk factors for criminal career duration: Comparisons with prevalence, onset, frequency and recidivism. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 30(4), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2155

- Farrington, D. P. (2021). New findings in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent development. In J. C. Barnes, & D. R. Forde (Eds.), The encyclopedia of research methods in Criminology and criminal justice (vol. 1, pp. 96–103). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Farrington, D. P., Biron, L., & Leblanc, M. (1982). Personality and delinquency in London and Montreal. In J. Gunn, & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Abnormal offenders, delinquency and the Criminal Justice system (pp. 153–201). Wiley and Sons.

- Farrington, D. P., & Jolliffe, D. (2021). Empathy, convictions, and self-reported offending of males and females in the Cambridge study in Delinquent development. In D. Jolliffe, & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Empathy versus offending, aggression and bullying: Advancing knowledge using the basic Empathy scale (pp. 77–89). Abingdon.

- Farrington, D. P., Jolliffe, D., & Coid, J. W. (2021). Cohort profile: The Cambridge study in Delinquent Development (CSDD). Journal of Developmental and Life Course Criminology, 7(2), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00162-y

- Farrington, D. P. & Loeber, R. (2000). Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10, 100–122.

- Farrington, D. P., Jolliffe, D., & Johnstone, L. (2008). Assessing violence risk: A framework for practice. Edinburgh: Risk Management Authority Scotland.

- Farrington, D. P., Loeber, R., Yin, Y., & Anderson, S. J. (2002). Are within-individual causes of delinquency the same as between-individual causes? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 12(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.486

- Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. J. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age: Recent results from the Cambridge study in Delinquent development. Springer.

- Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2011). Protective and promotive factors in the development of offending. In T. Bliesener, A. Beelman, & M. Stemmler (Eds.), Antisocial behaviour and crime: Contributions of Development and evaluation research to prevention and interpretation (pp. 71–88). Hogrefe.

- Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., Crago, R. V., & Coid, J. W. (2015). Intergenerational similarities in risk factors for offending. Journal of Developmental and Life Course Criminology, 1(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-015-0005-2

- Giluk, T. L., & Postlethwaite, B. E. (2015). Big five personality and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 72, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.027

- Glynn, M. (2014). Black men, invisibility, and desistance from crime: Towards a critical race theory from crime. Routledge.

- Habashi, M. M., Graziano, W. G., & Hoover, A. E. (2016). Searching for the prosocial personality: A Big Five approach to linking personality and prosocial behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9), 1177–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216652859

- Hines, D. A., & Saudino, K. J. (2008). Personality and intimate partner aggression in dating relationships: The role of the “Big Five”. Aggressive Behavior, 34(6), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20277

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

- Jolliffe, D. (2013). Exploring the relationship between the five-factor model of personality and self-reported offending. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.01.014

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2014). Self-reported offending: Reliability and validity. In Bruinsma, G. J. N. and Weisburd, D. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 4716–4723). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Jolliffe, D., Farrington, D. P., Loeber, R., & Pardini, D. (2016). Protective factors for violence: Results using the Pittsburgh Youth Study. Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.02.007

- Jones, S. E., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2011). Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.03.004

- Ljubin-Golub, T., Vrselja, I., & Pandžić, M. (2017). The contribution of sensation seeking and the Big Five personality factors to different types of delinquency. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 11(11), 1518–1536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817730589

- Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & White, H. R. (2008). Violence and serious theft: Development and prediction from Childhood to adulthood. Routledge.

- Mammadov, S. (2021). Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality. (online first). https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12663

- McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Del Pilar, G. H., Rolland, J. P., & Parker, W. D. (1998). Cross-cultural assessment of the five-factor model: The revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(1), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022198291009

- Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2001). Structural models of personality and their relation to antisocial behavior: A meta-analytic review. Criminology, 394), 765–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00940.x

- Murphy, S. A., Fisher, P. A., & Robie, C. (2021). International comparison of gender differences in the five-factor model of personality: An investigation across 105 countries. Journal of Research in Personality, 90, 104047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104047

- O’Riordan, C., & O’Connell, M. (2014). Predicting adult involvement in crime: Personality measures are significant, socio-economic measures are not. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.010

- Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048

- Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge study in Delinquent development. Cambridge University Press.

- Prins, H. (1997). H. J. Eysenck: Personality and crime: Where do we stand? - a response. Psychology, Crime & Law, 3(3), 203–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169708410813

- Pulkkinen, L., Lyyra, A., & Kokko, K. (2009). Life success of males on nonoffender, adolescence-limited, persistent and adult-onset antisocial pathways: Follow-up from age 8 to 42. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20297

- Roberts, B. W., Luo, J., Briley, D. A., Chow, P. I., Su, R., & Hill, P. L. (2017). A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000088

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 598–611.

- Shimotsukasa, T., Oshio, A., Tani, M., & Yamaki, M. (2019). Big Five personality traits in inmates and normal adults in Japan. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.018

- Slagt, M., Dubas, J. S., Dekovic, M., Haselager, G. J. T., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2015). Longitudinal associations between delinquent behaviour of friends and delinquent behaviour of adolescents: Moderation by adolescent personality traits. European Journal of Personality, 29(4), 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2001

- Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Aschwanden, D., Lee, J. H., Sesker, A. A., Strickhouser, J. E., et al. (2020). Change in five-factor model personality traits during the acute phase of the coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0237056. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237056

- Swets, J. A. (1986). Indices of discrimination or diagnostic accuracy: Their ROCs and implied models. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.100

- Van Voorhis, P. (2012). On behalf of women offenders: Women's place in the science of evidence-based practice. Criminology & Public. Policy, 11(2), 111–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2012.00793.x

- Walters, G. D. (2018). Predicting short- and long-term desistance from crime with the NEO personality inventory-short form: Domain scores and interactions in high-risk delinquent youth. Journal of Research in Personality, 75, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.05.004

- Wortman, J., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2012). Stability and change in the Big Five personality domains: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Australians. Psychological Aging, 27(4), 867–874. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029322