?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The integrative model of criminal choice proposes that cognitive and/or affective appraisals partially mediate the personality-crime relationship. The current study tests the integrated model of criminal choice across three different levels of subjective apprehension risk. Participants made hypothetical criminal choices in response to three vignette scenarios presenting criminal opportunities varying in the implied risk of apprehension. Consistent with the integrated model of criminal choice, when risk of apprehension was not manipulated, cognitive and affective appraisals (perceived risk and negative affect) partially mediated the relationship between personality (honesty-humility) and criminal choice. Higher levels of honesty-humility predicted increased perceived risk and negative affect, which in turn predicted decreased intentions to offend. When risk of apprehension was experimentally increased, personality did not affect either variable. As predicted, in both baseline and increased levels of risk of apprehension, higher levels of honesty-humility, perceived risk, and negative affect were found to significantly predict lower intentions to offend. Additionally, decreased perceived risk predicted reduced negative affect. These findings suggest that the mediating relationship between personality and crime may be dependent on the level of subjective risk of apprehension. Future studies may investigate whether different levels of situational risk moderate the relationship between personality and cognitive/affective appraisals.

Introduction

Since the ground-breaking work of Nagin and Paternoster in the 1990s, there has been considerable interest in the role of trait-based influences and situational factors in theories of criminal decision (Nagin & Paternoster, Citation1993, Citation1994). A number of studies have examined the competing contributions of emotions, cognition, and situational factors in determining whether a person will decide to commit a criminal offence, with results indicating the three are interconnected in ways not yet fully understood (Bouffard, Citation2015; Kamerdze et al., Citation2014; Pogarsky et al., Citation2017). One recent example in this tradition combined personality traits and situational factors, with consideration of affective responses, to produce an integrated model of criminal choice (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012). Based on this model, cognitive and affective appraisals partially mediate the personality-crime relationship. The current study extends Van Gelder and De Vries’ approach by experimentally manipulating participants’ perceived risk of apprehension. We test whether the direct and indirect associations between personality and criminal choice proposed by this model remain significant under conditions where perceived risk of apprehension is manipulated experimentally. We focus on individuals’ moral conscience as captured by the honesty-humility factor of the HEXACO model, which is the most important predictor of self-enhancement crime types (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014)

Theories of criminal decision-making

Rational choice and deterrence theories of criminal decision-making argue individuals take into account the perceived costs and benefits of a criminal opportunity when making a decision to offend (Clarke, Citation2009; Cornish & Clarke, Citation1986). Such cognitive and affective evaluations influence hypothetical criminal intentions and real-world criminal behavior (Erke et al., Citation2009; Painter & Farrington, Citation1999; Pickett et al., Citation2017). According to these theorists, a rational calculus of risk of apprehension and punishment influences criminal choice. However, findings stand equivocal (see Pratt et al., Citation2006, for a meta-analytic review). Some studies using self-reported delinquency measures report no effect of perceived risk of apprehension/punishment on crime-related activity (Paternoster, Citation1987; Piliavin et al., Citation1986; Steele, Citation2016). Others have shown that perceived risk mitigates both self-reported and officially verified delinquency (Anwar & Loughran, Citation2011; Lochner, Citation2007; McGrath, Citation2009; Nagin & Pogarsky, Citation2001; Thomas et al., Citation2013; Wright et al., Citation2004), as well as hypothetical criminal intentions (see Klepper & Nagin, Citation1989; Nagin & Paternoster, Citation1993, Citation1994; Pickett et al., Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014).

Affect may influence criminal decision-making in a number of ways. Emotional states can influence cognitions, and damage to brain areas that mediate emotional responses can impair decision-making (Pham, Citation2007). In relation to decisions to offend, Nagin and Paternoster (Citation1994) found perceptions of fun to be related to intentions to commit a range of crimes, and Kamerdze et al. (Citation2014) found positive mood states made participants less likely to cheat or drink drive. Affective states are themselves influenced by perceptions of sanction certainty and the consequences of apprehension (Roche et al., Citation2020). Roche et al.’s study of 829 young adults responding to vignettes describing a number of different crimes (drink driving, illicit drug use, theft, assault, burglary, robbery) found cognitive factors such as judgments of control over the situation, the severity of potential punishment and likelihood of apprehension influenced participants’ fear of apprehension which in turn influenced their reported willingness to commit these crimes in the future.

The influence of affect on criminal decision-making may also be conceptualized as the affect anticipated, rather than experienced, at the point of the criminal choice (Loewenstein et al., Citation2001). For example, expected shame and guilt (Tibbetts, Citation1997; Wikström & Treiber, Citation2007), anticipated fear (Lindegaard et al., Citation2014) and anticipated regret (Warr, Citation2016) can all deter offending behavior. Anticipated happiness (Lindegaard et al., Citation2014), joy (De Haan & Voss, Citation2003), excitement (Matsueda et al., Citation2006), calmness (Leclerc & Lindegaard, Citation2018), and sexual pleasure (Bouffard, Citation2002), and fun, social dominance and sexual gratification (Cornish & Clarke, Citation2006) can also function as perceived benefits. Anticipated affect involves contemplation of an expected outcome of the crime (albeit an affective one) and is thus presumed to operate through the cognitive mode (see Loewenstein et al., Citation2001; van Gelder et al., Citation2022), in contrast to the immediate affect experienced during the decision itself.

Immediate affect occurs as a proximate reaction to weighing up potential consequences (see Schlösser et al., Citation2013), or from extraneous influences unrelated to the criminal choice, and can either deter or encourage criminal acts (Bouffard, Citation2015; Van Gelder, Citation2013). Anger is related to decreased cost perceptions and can lead to more rapid criminal decisions (Ellwanger & Pratt, Citation2014; Exum, Citation2002; Topalli & Wright, Citation2014; Van Gelder et al., Citation2014), while fear leads to increased cost perceptions, more considered deliberations, and ultimately impedes illegal activities (Pickett et al., Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012). Immediate affect influences the criminal calculus differently than does anticipated affect (Schlösser et al., Citation2013). The current study focuses on immediate affect, including fear of apprehension (as a crime-related emotion, following the approach of Pickett et al., Citation2017) and negative state affect (which includes general feelings of fear, worry and insecurity, following Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012).

Personality and criminal decision-making

Self-control is viewed as the most reliable personality factor predicting offending behavior. The General Theory of Crime (GTC, Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990), attributes deviant behaviors of those low on self-control to desires to advance their own self-interest and maximize pleasure (Pratt & Cullen, Citation2000). Current models of personality, however, offer a more nuanced view. For instance, within the FFM (Five Factor Model; McCrae & Costa, Citation1987) and the HEXACO (Honesty-humility, Emotionality, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to experience; Ashton et al., Citation2004), conscientiousness (the ability to control impulses and think carefully prior to acting) and agreeableness (the tendency to be empathetic, forgiving, cooperative and trusting within interpersonal relationships) both negatively predict antisocial behavior (see also Jolliffe, Citation2013; O’riordan & O’connell, Citation2014; Samuels et al., Citation2004, for more recent FFM examples; see Ashton & Lee, Citation2008; Međedović, Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, for examples involving the HEXACO).

Low honesty-humility, the 6th trait of the HEXACO, which is not equivalent to any single trait within the FFM, manifests as an interest in personal gains and self-enhancement, and immoral behaviors (greed, hypocrisy, cunningness, arrogance and mischief, Ashton et al., Citation2004). People high in this trait avoid corruption and fraud, are reluctant to exploit others, are interpersonally genuine, and uninterested in wealth and status (Lee & Ashton, Citation2004). Honesty-humility negatively predicts a range of delinquent and antisocial behaviors (Rolison et al., Citation2013; Vrućinić, Citation2017), including workplace delinquency (De Vries & Van Gelder, Citation2015; Lee, Ashton, and De Vries, Citation2005; Lee, Ashton, and Shin, Citation2005), unethical business decisions (Ashton & Lee, Citation2008; Ogunfowora et al., Citation2013), cyberbullying (Smith, Citation2015), cheating (Hilbig & Zettler, Citation2015; Pfattheicher et al., Citation2018), sexual harassment (Lee et al., Citation2003), self-reported delinquency (Dunlop et al., Citation2012; Međedović, Citation2017), students’ antisocial behavior (Allgaier et al., Citation2015), and self-reported intentions to offend (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012). Honesty-humility exhibits the strongest incremental validity in predicting crime-related behaviors, over the remaining five HEXACO factors (see Lee, Ashton, and De Vries, Citation2005; Lee, Ashton, & Shin, Citation2005; Međedović, Citation2017) and the FFM (Ashton & Lee, Citation2008).

Integrating personality with cognition and affect in criminal decision-making

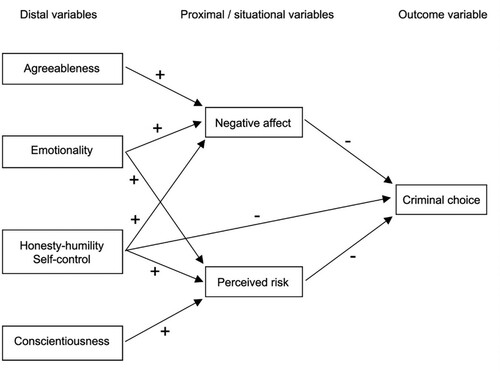

In the context of criminal decision-making, personality influences rational judgments (Bouffard, Citation2007; Fine & Van Rooij, Citation2017; Jacobs, Citation2010; Steele, Citation2016), and emotional reactions (Costa & McCrae, Citation1980; Komulainen et al., Citation2014; Loewenstein et al., Citation2001; Lucas & Fujita, Citation2000). Van Gelder and De Vries' (Citation2012) integrated model of criminal choice provides a detailed account of how personality, cognition, and immediate negative state affect (feelings of insecurity and fear) interact to increase the likelihood of offending behavior. The model incorporates the dual process model of information processing (Shulman et al., Citation2016) and argues differences in personality differentially activate either the cognitive (‘cool’) mode, or affective (‘hot’) mode (see ). For instance, Honesty-humility is argued to influence criminal choice directly (individuals low on this trait are more likely to perceive and act on criminal opportunities); as well as indirectly via both cognitive and affective pathways (individuals high in honesty-humility consider potential negative outcomes increasing their perceived risk of apprehension/punishment, and experience more negative emotions, both of which reduce their intentions to offend). In some cases personality operates through the cognitive mode. For instance, the criminal decision-making of people who are high in conscientiousness will operate through the cognitive rather than affective mode, and these individuals will carefully consider the negative consequences of offending in making these decisions. For others, criminal decision-making will be mediated by the affective mode. For instance, people low on agreeableness will have a lower threshold for offending because their affective mode of impatience and loss of temper is activated more readily. Correlational data, using choices made about hypothetical criminal scenarios, support these relationships (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2016).

Figure 1. Integrated model of criminal choice. Associations between honesty-humility, negative affect and criminal choice, as proposed by the integrated model of criminal choice (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012).

Though no other studies have investigated the mechanisms that link honesty-humility to criminal choice, several studies have investigated how self-control is related to criminal choice. For instance, individuals with higher self-control, are less likely to experience anger, and consequently less likely to engage in aggressive driving (Ellwanger & Pratt, Citation2014). Self-control also indirectly reduces self-reported delinquent behavior, via greater perceived risk of getting caught and/or rational considerations of losing respect of peers (Intravia et al., Citation2012). Self-control is closely related to honesty-humility, as it is an interstitial trait based on honesty-humility facets of the main HEXACO dimensions, including the honesty-humility facets of fairness and modesty (see De Vries et al., Citation2009; De Vries & Van Gelder, Citation2013; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012), so it is reasonable to expect similar mediating relationships for honesty-humility.

Methodological considerations

Using vignettes describing hypothetical criminal opportunities (drink driving and shoplifting), Piquero and Tibbetts (Citation1996) manipulated the perceived risk of being caught and punished (by including or excluding information about security cameras in the store, for example). Mixed support was found for the indirect effects of personality on criminal choice via perceived risk, with low self-control being related to shame and perceived pleasure, but not to perceptions about sanctions. However, the potential effects of the experimental manipulations on either participants’ perceived risk of sanction or their criminal decision are ambiguous as the authors reported only in a footnote that they had ‘no effect’ (p. 492), and they subsequently averaged across these manipulations in their primary analyses. Given this, it is not surprising that self-reported perceived risk of sanction did not correlate with personality across the combined groups.

The current study adopts a similar experimental manipulation of perceived risk of apprehension. If experimentally manipulating perceived risk of apprehension renders the indirect pathway, from personality to criminal choice insubstantial, then the presumed causal interactions between these variables may not be as Van Gelder & De Vries’ model (Citation2012) describes. Instead, the proposed mediating relationship between personality and crime may depend on specific situational characteristics. For example, in high-risk situations, where the effect of situational elements is greater (Pickett et al., Citation2017), personality may not play a crucial role in risk perceptions, whereas it may play a more important role in low-risk situations. No study, to our knowledge, has examined the indirect effects of personality on criminal choice, under varying levels of implied/perceived risk of apprehension.

Further, we aim to investigate the relationship between cognitive and affective appraisals. Immediate affect can itself result from rational considerations (see Schlösser et al., Citation2013), such as perceptions of risk (Gibbs, Citation1975). Deterrence may, therefore, be partly emotional (Jacobs & Cherbonneau, Citation2017). That being the case, cognitive judgments may affect criminal choice through affective appraisals, as well as directly (see Camerer et al., Citation2005; Loewenstein et al., Citation2001, for a discussion). This theory was recently tested by Pickett et al. (Citation2017). Using hypothetical vignettes, Pickett et al. (Citation2017) found that fear of apprehension partially mediated the effect of perceived risk on intentions to commit a crime. Although they found that perceived risk also had a direct effect on criminal choice, this direct effect was not significant across all scenarios. This finding is important as it suggests failing to explicitly incorporate affect in rational choice and deterrence models, may have resulted in underestimations of the strength of the relationship between perceived risk and criminal choice.

The current study

In the present study participants responded to three hypothetical criminal scenarios involving financially motivated crimes (theft, fraud, and drug dealing). Within these scenarios, across participants, the implied risk of apprehension was manipulated (decreased, baseline, increased) via descriptions of recent police/security behavior. For each scenario participants reported their subjective perceived risk of apprehension and expected sanction severity, levels of negative affect, and intentions to offend (their criminal decision). We also measured personality, with a focus on honesty-humility, and collected data on participants’ prior criminal behavior.

The aim of the current study was to test and extend the integrated model of criminal choice introduced by Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2012). We tested the predictions of the model against our baseline data (scenarios in which no attempt was made to experimentally manipulate perceived risk of apprehension); and examined whether the model’s indirect pathway from personality to criminal choice via perceived risk of apprehension/punishment persisted under conditions of artificially increased perceived risk of apprehension. Finally, we extended the integrated model of criminal choice (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012) to incorporate the theoretical position that cognitive perceptions of risk operate via the affective mode (Camerer et al., Citation2005; Loewenstein et al., Citation2001). To this end we tested whether personality (honesty-humility) is serially (as opposed to independently) mediated by both perceived risk and negative affect.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited online via study invitations posted on social media (including FaceBook, Twitter, and Reddit), and online (global) recruitment platforms Survey Circle (surveycircle.com), and Psychological Research on the Net (psych.hanover.edu/Research/exponnet.html), the participant pool of first-year psychology students from a regional Australian university, and through an Australian psychology private practice clinic. Six hundred and forty participants completed the survey. Thirty-nine participants were excluded for failing to identify as either male or female (N = 4), being less than 17 years old (N = 13, since ethical approval was obtained for participants above the age of 17), completing the study in less than 400 s (N = 14), or longer than 3.5 h (N = 5), or exhibiting negligible deviation across their responses (N = 3), leaving a final sample of N = 601 participants. The final sample comprised N = 296 men (49.3%) aged 18–81 (M = 29.02, SD = 10.97), and N = 305 women (50.7%) aged 17–68 (M = 31.18, SD = 11.32). Participants provided informed consent under protocol number H18028, issued by the Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants were predominantly Australian (40%), American (27%) and European (30%), and generally highly educated (80% possessed a university degree and 20% had graduated high school with no further education completed, see for additional details). Six per-cent reported prior arrests, 69% reported prior offences without an arrest, and 25% reported no prior offending or arrest experiences. Complete details of participants’ self-reported past offending behavior are presented in .

Table 1. Participants’ source, age, sex, country of residence and education.

Table 2. Types of crime, percentages, and totals for participants’ self-reported past offending behavior.

Scales and measures

HEXACO-60

A 60-item short version of the HEXACO Personality Inventory Revised (Ashton & Lee, Citation2009) was used to measure six traits (honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience). Responses are provided on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘Strongly agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’. Example items measuring the honesty-humility dimension include ‘I would never accept a bribe, even if it were very large’ and ‘Having a lot of money is not especially important to me’. shows Cronbach’s alpha values of the HEXACO 60-item scale, as reported in previous studies and as observed in the current study.

Table 3. Internal consistency estimates of reliability for the six individual domains of the HEXACO 60-item scale and BSCS 13-item scale.

Brief self-control scale (BSCS)

Self-control was measured using the Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS; Tangney et al., Citation2004), a short 13-item form of the longer 36-item self-control scale, which concentrates on processes directly involving self-control. Participants rated how well each statement describes them, using a 5-point rating scale ranging from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’. Examples of statements include ‘I am lazy’ and ‘I say inappropriate things’. shows Cronbach’s alpha values of the BSCS 13-item scale, as reported in previous studies and as observed in the current study.

Criminal scenarios

Vignettes

Nine vignettes in total (3 criminal scenarios × 3 levels of implied risk of sanction) were used. Since RCT may only account for criminal decisions that provide scope for an objective cost/benefit judgement of some kind (see Hayward, Citation2007, for a discussion), we used criminal scenarios with clearly defined and equivalent economic rewards. The scenarios described fraud, purchase of stolen goods, and drug trafficking opportunities, respectively, in which the actor (‘the participant’) stood to gain $2000. These are similar to scenarios used in several recent studies of criminal decision-making (Pickett & Bushway, Citation2015; Pickett et al., Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014). Perceived risk of sanction was experimentally manipulated for each offence type, by including (or not) an extra sentence, which provided relevant policing/security information. Each participant read and responded to three vignettes, encompassing all three scenarios and all three levels of perceived risk of sanction (decreased, baseline, increased). The level of risk reflected in each scenario was varied across participants according to a Latin-square design, such that each participant responded to one of the criminal opportunities at the experimentally decreased, baseline, and experimentally increased levels of risk of sanction. All vignettes and the combinations in which they were allocated to participants are shown in and , respectively.

Table 4. Vignettes with manipulations of perceived sanction certainty.

Table 5. Vignette scenario and level of implied apprehension risk combinations used.

Perceived risk

Perceived likelihood of apprehension and severity of sanction were measured via two 7-point items (‘How likely or unlikely do you think you would be to get apprehended by the police if you … ’ – ‘Very unlikely’ to ‘Very likely’) and (‘How severe do you believe the punishment would be?’ – ‘Not at all’ to ‘Extremely’). Following Nagin and Paternoster (Citation1993), and Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2014), an overall perceived risk score was calculated by multiplying participants’ responses to these items. Scores were then square-root transformed to approximate normality. An alternative perspective emphasizes the relative importance of the risk of apprehension, over the expected severity of sanction when making the criminal choice (Roche et al., Citation2020). We, therefore, also examined whether operationalizing perceived risk as the perceived likelihood of apprehension alone, as opposed to the combined measure, impacted our models’ outcomes.Footnote1

Negative state affect

Negative state affect was measured using five questions displayed after each scenario, such as ‘Do you find the situation frightening?’ and ‘Would you be worried?’. Participants responded using a seven-point scale from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’. The responses were averaged between the items to construct the scale (consistent with Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, who reported excellent alpha reliability of this scale, α = .96). Negative affect scale in this study also demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.95). The researchers asked the participants ‘How afraid would you be of getting apprehended?’, with a 7-point response scale from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’, as a specific measure fear of apprehension (as opposed to the more general negative state affect questions above). However, answers to this item correlated strongly with the combined score on the negative affect questions (r = .77), precluding the simultaneous use of both as separate predictors in the one model, and both ultimately predicted the criminal decision (fear of apprehension: r = −.44, negative affect: r = −.39) so these two measures were averaged to create a combined negative state affect score.

A point of difference in the methodology design between Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2012, Citation2014) and the current study is that in their study participants were asked to imagine they ‘have decided to commit the offence’. This placed participants in a hypothetical post-decision situation. Deciding to commit an offence may itself lead to the perception of new, more severe, consequences that may, as a result, lead to increased negative state affect (Copes et al., Citation2012; Van Gelder, Citation2013). Therefore, to best capture negative affect at the time of the criminal decision, participants in the current study were instructed to imagine the point at which they were faced with making the criminal decision.

Criminal decision

Participants were asked ‘If you were in this situation, what is the percent chance (0–100 percent) that you would actually commit the crime?’, measuring participants’ intentions to offend using a percentage slider. This non-dichotomous approach allowed participants to concede their ambivalence in choosing to commit an offence (Sitren & Applegate, Citation2006). This variable was log (base 10) transformed to approximate a normal distribution.

Combining participants’ responses to the different crime types

In the current study we tested the integrated model of criminal choice by combining the responses to the three crime types. This is because we were more interested in a generalizable test of criminal choice, than in examining differences in choice between the three specific scenarios adopted. Results showed participants exhibited significant differences across the three crime types in negative affect, F(2, 494) = 51.42, p < .001, = .172; perceived risk of sanction, F(2, 494) = 44.55, p < .001, = .153; and in the likelihood that they would make a criminal choice, F(2, 494) = 8.07, p < .001,

= .032. Participants perceived more risk and experienced more negative affect in response to the drug-trafficking scenario compared to the other two scenarios, and in the insurance fraud scenario compared to the stolen goods scenario (for all pairwise contrasts, p < .001). Participants were more likely to purchase stolen goods than to commit either insurance fraud (p = .012) or drug trafficking (p < .001), which they were equally disinclined to do (p = .764).

Past criminal behavior

Participants responded to 11 questions about common illegal behaviors (for example ‘Have you ever driven while intoxicated’, see ) using a six-point response scale (Never, Once, Two or three times, Four to six times, Seven to ten times, and Ten or more times). An additional question asked if they had committed any other criminal offence, to capture any offences not included on the list. Participants then indicated if they had ever been arrested or convicted (and if yes, how many times) for any of the offences they noted on the preceding 12 questions. From these responses, two dichotomous variables were calculated. Participants who reported having been arrested/convicted at least once in the past were coded as 1, while those who reported no past arrest experiences were coded as 0 (past arrest experience). Participants who reported an offence but no arrests were coded as 1, while other participants were coded as 0 (punishment avoidance experience). These questions were intentionally administered last, so that participants were not primed to think too much about their own criminal behavior during the preceding phases of the study.

Procedure

Data were collected online using the Qualtrics survey platform (https://www.qualtrics.com). After providing consent by progressing beyond an online information statement, participants reported their gender, age, nationality and educational level, and then completed the HEXACO and Brief Self-control scales (in random order). Participants were then presented (serially, and in a random order) with three vignettes, respectively describing three criminal opportunities (see ), each presented in a context of decreased, baseline, or increased likelihood of sanction (see ). Following each vignette, participants reported their perceived likelihood and severity of sanction, and their fear of apprehension. They then answered the five negative affect questions and indicated their criminal decision. After responding to all three scenarios participants provided information about their prior criminal behavior. Following completion of the study, participants were directed to an online debriefing statement.

Results

Criminal decision responses

A number of participants (N = 100) indicated zero likelihood that they would commit the hypothetical crime, across all three scenarios, creating bimodal distributions for this variable. Scholars have long debated whether deterrent effects exist across individuals with differing criminal propensities, with classic deterrence theorists arguing deterrent effects are consistent regardless of criminal propensity, and propensity theorists arguing deterrent effects are strongest among the least criminally prone (Wright et al., Citation2004). Using data from the Dunedin study, Wright et al. tested these propositions and found deterrent effects to be in fact strongest among the most criminally prone. From a policy perspective, it also makes sense that efforts to deter offenders should be aimed at those most likely to offend. Consequently, we determined to split the full sample into two groups: one group consisted of the ‘zero responders’ (N = 100), while the other group included all remaining participants (N = 501). Planned analyses were conducted on the larger group, while additional analyses examined differences between the two groups. This decision was in our view defensible theoretically, while also avoiding violations of assumptions of multivariate normality (normally distributed residuals) that would necessarily have occurred should the data have been analysed as a whole.

Relationships between key variables

An overview of the zero-order relationships between study variables are provided in . In terms of the relationships relevant to the integrated model of criminal choice, honesty-humility, conscientiousness, self-control, negative affect, and perceived risk all negatively predicted the tendency to commit a crime, as expected. Additionally, honesty-humility, emotionality, and self-control positively predicted both negative affect and perceived risk. Negative affect and perceived risk were positively associated. Conscientiousness predicted perceived risk, as expected, although it also predicted negative affect (not predicted by the model). Also inconsistent with the model, agreeableness did not predict negative affect or criminal choice.

Table 6. Correlation co-efficients between HEXACO personality traits, self-control, perceived risk, negative affect, and criminal choice.

Unique contribution of personality traits to criminal choice

Since the key personality variables shared significant variance, a hierarchical multiple regression tested which of the five traits (honesty-humility, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotionality, and self-control) predicted unique variance in criminal choice (as measured using the baseline scenarios), after controlling for the effects of age and sex. No multivariate (at p < .001 criterion for Mahalanobis distance) or univariate (cases with z values more than +/−3.29) outliers were detected, assumptions of linearity were met, and there was no evidence of multicollinearity, with tolerance levels greater than .10 and variance inflation factors (VIF) below 10. After controlling for age and sex (which both predicted criminal choice, (R2 = .039, F(2, 498) = 10.16, p < .001)), only honesty-humility predicted unique variance in criminal choice, with all 7 variables explaining 13% of variance in criminal choice (ΔR2 = .088, R2 = .128, adjusted R2 = .115, F(7, 493) = 10.26, p < .001, see ). Honesty-humility was also higher in participants who reported no criminal history (M = 3.62, SD = 0.60), as opposed to those who reported committing at least one crime (M = 3.33, SD = 0.63), t(498) = 4.164, p < .001, d = 0.47, confirming the real-world relevance of this variable to criminal behavior.

Table 7. Hierarchical multiple regression predicting criminal choice.

Mediation model – baseline sanction risk scenarios

Since honesty-humility was the only personality variable to predict unique variance in criminal choice, we focused on it to test the indirect of effects of personality on criminal choice, via perceived risk and severity of sanction and negative affect, respectively, as predicted by Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2012) integrated model of criminal choice. We also tested our hypothesis that negative affect itself would mediate the relationship between perceived risk and severity of sanction and criminal choice. Hayes (Citation2017) PROCESS multiple mediator model (6) tested these predictions, with honesty-humility as the primary predictor variable, perceived risk and severity of sanction and negative affect as mediators, and criminal choice as the outcome variable. We controlled for gender, age, past arrest and punishment avoidance experiences by entering these variables as covariates in the model. Bootstrapping (5000 resamples) was utilized to estimate the indirect effects, as recommended by Hayes (Citation2017).

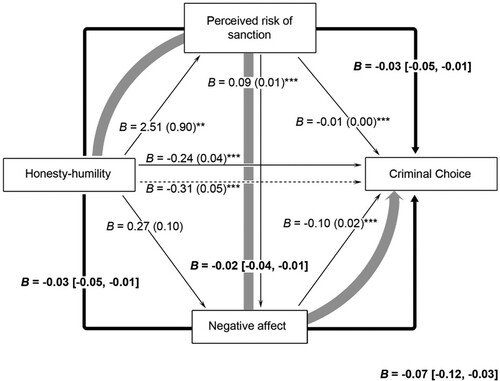

As demonstrated in , all three hypothesized indirect paths from honesty/humility to criminal choice (via perceived risk and severity of sanction, negative affect, and perceived risk of sanction and negative affect serially) were significant individually and in combination (B = −0.07, 95%CI [−0.12, −0.03]), as was the direct path from honesty-humility to criminal choice, indicating partial mediation of the honesty-humility – criminal choice relationship by perceived risk and severity of sanction and negative affect. Regarding the covariates, sex: B = 3.60, 95%CI [1.37, 5.90], p = .001; age: B = 0.17, 95%CI [0.05, 0.28], p = .002; and arrest experience: B = −4.69, 95%CI [−9.12, −0.32], p = .031 predicted perceived risk and severity of sanction (with women, older people, and those who have never been arrested perceiving more risk), while arrest: B = −0.62, 95%CI [−1.13, −0.14], p = .009; and punishment avoidance experiences: B = −0.32, 95%CI [−0.62. −0.02], p < .05 predicted lower negative affect. Finally, age predicted criminal choice: B = −0.01, 95%CI [−0.01. −0.00], p = .034, with older people less likely to commit the crime. Overall, 28.9% of the variance in criminal choice was accounted for by all the predictors in the model (R2 = .289).

Figure 2. Baseline risk of sanction. Model demonstrating partial mediation of the effect of honesty-humility on criminal choice by perceived risk of sanction, and negative affect, respectively (bolded pathways), and a third indirect pathway, which passes through both mediating variables (shown in grey). Unstandardized regression coefficients for each indirect pathway are shown in bold (alongside 5000-sample bootstrapped 95%CI in square brackets, none of which contain zero, so all of which indicate significant effects), while unstandardized regression co-efficients for remaining paths are unbolded (with standard errors in parentheses). The unstandardized regression co-efficient (and its 95% CI, which also does not include zero) for the three indirect pathways combined is shown to the bottom right of the figure. ** p < .01, *** p < .001. N = 501.

We also tested an alternative mediation model, which was identical to that above in all respects, except that it reversed the order of perceived sanction certainty and negative affect in the serial mediation pathway (now modeling the path from honesty/humility to criminal choice, via negative affect and perceived sanction certainty, in that order). This model was motivated by post hoc considerations that affective responses to stimuli can themselves affect risk appraisal (Barnum & Solomon, Citation2019). In this model, the four-term indirect pathway predicted criminal choice, but the effect is an order of magnitude smaller than in our original model (B = 0.003, 95%CI [0.0003, 0.0067]), confirming the data to be a better fit to our original hypothesis, than to this alternative theory.

We additionally explored whether our operationalization of perceived risk impacted the final model. Replacing our combined measure of perceived risk (a combination of risk of apprehension and expected sanction severity), with the single measure of risk of apprehension only, had no impacts on the final model. In this version of the model, all three indirect paths, as well as the direct path between honesty-humility and criminal choice remained significant.

Risk of sanction – manipulation check

To investigate whether our manipulation of key situational characteristics resulted in the intended effects on perceived risk of sanction (which would be expected to carry over to both negative affect and criminal choice, if perceived risk does indeed share a causal relationship with these other measures), mixed-effect univariate analyses of variance were performed. The primary independent variable of interest was implied risk of sanction (within-subjects, three levels: decreased, baseline, and increased), while gender was included as a between-subjects factor. The dependent variables were perceived risk of sanction, negative affect, and criminal choice. Visual inspection of distributions confirmed normality. The assumptions of homogeneity of variance-covariance were met for all models as indicated by the Box’s (p > .001) and Levene’s (p > .05) tests. Where assumptions of sphericity were violated, degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt estimates.

For all three dependent variables, a significant main effect of implied risk of sanction was observed (perceived risk of sanction: F(2, 998) = 10.92, p < .001, = .02; negative affect: F(1.96, 976.76) = 7.24, p < .001,

= .01; criminal choice: F(1.99, 990.61) = 15.85, p < .001,

= .03.). Planned contrasts confirmed that the increased risk condition (relative to the baseline condition) increased perceived risk of sanction, and negative affect, and decreased likelihood of making a criminal choice (all p < .001). The decreased risk condition significantly increased the likelihood of making a criminal choice, relative to baseline (p = .032), but did not reduce either perceived risk of sanction (p = .85), or negative affect (p = .40), relative to baseline. As such, the manipulations of implied risk of sanction successfully increased perceived risk of sanction, but were not successful in decreasing perceived risk, relative to baseline (see ).

Table 8. Scale totals and standard deviations for conditions of decreased, baseline, and increased levels of perceived sanction certainty.

Women reported significant greater perceived risk (F(1, 499) = 25.56, p < .001, = .049) and negative affect (F(1, 499) = 33.78, p < .001,

= .06), and a significantly lower likelihood of making a criminal choice (F(1, 499) = 6.62, p = .010,

= .01) than did men. Across all three models, though, the sex-by-risk level interactions were not significant (all p > .14), indicating that the manipulation of risk of sanction had similar effects for men and women (see ).

Table 9. Scale totals and standard deviations for males and females.

Mediation model – increased sanction risk scenarios

We had originally intended to test the integrated model of criminal under conditions of both increased and decreased perceived risk of sanction, however, only our attempts to increase (not decrease) perceived risk were successful. As such we present here the outcomes of a mediation model applied to predict criminal choice in response to the increased risk scenarios, which is identical to that applied to the baseline scenarios above.

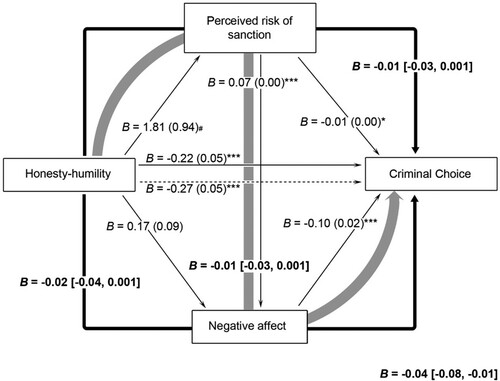

The three hypothesized indirect paths from honesty/humility to criminal choice (via perceived risk of sanction, negative affect, and perceived risk of sanction and negative affect serially) were significant in combination (B = −0.04, 95%CI [−0.08, −0.01], where the 95%CI was estimated according to 5000 bootstrapped samples), as was the direct path from honesty-humility to criminal choice, indicating partial mediation of the honesty-humility – criminal choice relationship by perceived risk of sanction and negative affect (see ). However, unlike in the previous mediation model, none of the indirect effects were reliably significant individually (all bootstrapped 95%CI contained zero), so it is impossible to determine which indirect effects were responsible for the partial mediation. Aside from this difference, the two mediation models were remarkably similar with respect to the size of the path coefficients, with the exception that the path from honesty-humility to perceived risk of sanction approached significance only in the increased risk model (B = 1.81, p = .055) compared to its significant effect in the baseline risk model (B = 2.51, p = .005).

Figure 3. Increased risk of sanction. Model demonstrating partial mediation of the effect of honesty-humility on criminal choice by perceived risk of sanction, and negative affect, respectively (bolded pathways), and a third indirect pathway, which passes through both mediating variables (shown in grey). Unstandardized regression coefficients for the indirect pathways are shown in bold (alongside 5000-sample bootstrapped 95%CI in square brackets, all of which contain zero, so none of which indicate significant effects), while unstandardized regression co-efficients for remaining paths are unbolded (with standard errors in parentheses). The unstandardized regression co-efficient (and its 95% CI, which does not contain zero and so represents a significant combined effect) for the three indirect pathways combined is shown to the bottom right of the figure. # p = .055, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. N = 501.

Regarding the covariates, sex: B = 3.22, 95%CI [0.91, 5.54], p = .005; arrest experience: B = −4.94, 95%CI [−9.59, −0.31], p = .003; and punishment avoidance experience: B = −3.86, 95%CI [−6.94, −0.83], p = .007 predicted perceived risk of sanction (with women, those who have never been arrested or had never avoided punishment for a crime they did commit, perceiving more risk), while arrest: B = −0.68, 95%CI [−1.14, −0.21], p = .003; and punishment avoidance experiences: B = −0.34, 95%CI [−0.57. −0.09], p = .020 predicted lower negative affect. Finally, age: B = −0.01, 95%CI [−0.01. −0.00], p = .001, and arrest experience: B = 0.22, 95%CI [0.01. 0.43], p = .048 predicted criminal choice with older people and those who had never been arrested, less likely to commit the crime. Overall, 21.8% of the variance in criminal choice was accounted for by all the predictors in the model (R2 = .218).

As with the baseline mediation model, we also replaced our combined measure of perceived risk (a combination of risk of apprehension and expected sanction severity), with the single measure of risk of apprehension only and estimated the model a second time. On this occasion, the second model differed from the first in that the direct pathway between honesty-humility and criminal choice remained significance, but the overall indirect pathway (nor any of the individual indirect pathways) was no longer significant (B = −0.003, 95%CI [−0.017, 0.010]).

An alternative integrated model?

An alternative model (and one which we only considered post hoc) places honesty-humility as a moderator of the relationships between perceived sanction certainty and negative affect, respectively, and criminal choice. Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2014) proposed that cognitive and affective processing modes influence criminal choices to varying relative extents, as a function of individual differences (such as personality traits). They modeled these as mediation relationships (as we have done above), but personality could alternatively be conceived as a moderator. In such models, the relationship between perceived sanction certainty and criminal choice would be strongest when honesty-humility is high, since individuals high on honesty-humility would be most likely to base their choice on a rationale calculus. Inversely, individuals low on honesty-humility would base their criminal choice on their affective response, so the relationship between negative affect and criminal choice would be strongest when honesty-humility is low. Moderation models (controlling for sex, age, and past arrest and punishment avoidance experiences, as well as for either perceived sanction certainty of negative affect – whichever variable was not involved in the moderation term), revealed that honesty-humility did indeed moderate the relationship between perceived sanction certainty and criminal choice (B = 0.007, 95%CI [0.001–0.013], p = .024, ΔR2 = .007) and between negative affect and criminal affect (B = 0.050, 95%CI [0.007–0.094], p = .024, ΔR2 = .007). Effects were small and the patterns of moderation were not entirely as predicted. Both perceived sanction certainty and negative affect had their greatest impacts on criminal choice when honesty-humility was low.

Participants who reported no intentions to make a criminal choice

We originally removed 100 participants from our primary analysis as they indicated no intention to make a criminal choice across all three scenarios. Here we briefly compare these participants with the remaining sample (to avoid issues arising from unequal sample sizes across groups) on our key study variables to inform on the potential consequences of their exclusion. The 100 excluded participants contained proportionately more women (67%) than the remaining sample (47.5%), and were also older (M = 35, SD = 13.3 years, compared to M = 29, SD = 10.4 years). We, therefore, compared the two groups on key variables using a series of ANCOVAs, controlling for age and sex.

Compared to the remaining sample, our excluded participants scored higher on honesty-humility, F(1,195) = 61.15, p < .001, = .239; conscientiousness, F(1,195) = 6.63, p = .011,

= .033; and self-control, F(1,195) = 12.39, p = .001,

= .060; though not on emotionality (p = .242), extraversion (p = .148), agreeableness (p = .089), or openness to experience (p = .432). They also reported greater negative affect, F(1,195) = 8.59, p = .004,

= .042; and greater perceived risk of sanction, F(1,195) = 10.50, p = .001,

= .051.

Discussion

The current study investigated how personality, affect, and situational factors are related to offending behavior, using the integrated model of criminal choice proposed by Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2012). We replicated this model but only in part, as we found the HEXACO trait honesty/humility to be the only unique personality predictor of intentions to offend, while controlling for the effects of all other personality variables including self-control. Our findings also advanced the original model, as we tested whether the predicted indirect pathway from honesty-humility to criminal choice (through perceived risk and negative affect) would be evident when risk of apprehension was manipulated. We observed this pathway in both the baseline and increased risk conditions, although in the increased risk condition we could not identify any significant individual indirect effects. We will now expand further on these findings.

Personality and self-reported intentions to offend

Consistent with previous research (De Vries & Van Gelder, Citation2015; Dunlop et al., Citation2012; Lee, Ashton, & De Vries, Citation2005; Lee, Ashton, & Shin, Citation2005; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2016) honesty-humility predicted intentions to offend, controlling for the effects of age, gender and the overlapping effects of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotionality, and self-control. This finding challenges the theoretical precedence given to low self-control in causing anti-social behavior (Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990; Pratt & Cullen, Citation2000). Although self-control and honest/humility are overlapping constructs, our findings indicate the latter to be of greater importance when determining intentions to offend. Honesty-humility is of particular relevance to financial crimes such as those examined in the current study, potentially accounting for this result (see also Miller & Lynam, Citation2001, for a discussion). Future research is warranted to examine the crime-specific impacts of personality on criminal choice.

Perceived risk and negative affect as mediators of the personality-crime relationship

As expected, and consistent with previous research (Pickett et al., Citation2017), higher levels of perceived risk and negative affect were observed when the subjective risk of apprehension was artificially increased (high-risk condition), compared to the baseline condition. By contrast, levels of perceived risk and negative affect did not decrease in the low-risk condition. We are unsure why this was the case but it is possible the offences used in the current study were already perceived as quite low risk in the baseline condition (creating a floor effect). Whatever the reasons for this failure to operationalize low risk adequately, the outcome was that we could only test our hypotheses in the baseline and in the high-risk conditions.

Consistent with the model of criminal choice (Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012), we observed honesty-humility to indirectly predict criminal choice (through perceived risk and negative affect), at baseline levels of situational risk. When the subjective risk of apprehension was not clearly stated, we found individuals lower in honesty-humility reported lower levels of perceived risk and severity of sanction (defined as perceived probability of apprehension, and severity of punishment) and higher negative affect (fear and insecurity), which were both related to increased intentions to offend. These findings also align with prior observations that perceived costs and/or negative affect partially mediate the relationship between personality and criminal choice (Ellwanger & Pratt, Citation2014; Intravia et al., Citation2012; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2016).

When the subjective risk of apprehension was experimentally increased, intentions to offend remained partially mediated by perceived risk of sanction and negative affect. The individual mediating pathways (i.e. perceived risk/severity of sanction, negative affect, and perceived risk/severity of sanction and negative affect serially) bordered on statistical significance only, meaning we could not determine with sufficient confidence that all indirect effects individually contributed to the mediation effect. Nevertheless, these findings support Van Gelder and De Vries’ model of criminal choice. Importantly, the indirect pathways were not observed to be collectively significant in this increased risk model, when we replaced our composite measure of perceived risk/severity of sanction, with a unitary measure of perceived likelihood of apprehension only. This finding refutes suggestions that the perceived likelihood of apprehension alone, and not the expected severity of sanction, feeds into risk assessments of criminal choices. Rather, when the implied risk of apprehension is high, the expected severity of the sanction may play an important role in the overall perceived risk associated with a criminal choice.

We also modeled honesty-humility as a moderator of the relationships between perceived sanction certainty and negative affect, and criminal choice. These models investigated an alternative conceptualization of the integrated model of criminal choice, that sees personality dictating the relative extents to which cognitive and affective processing influence the criminal choice. Honesty-humility did indeed moderate these relationships, but in both cases the relationships strengthened as honesty-humility decreased. This is not consistent with the suggestion that a rational calculus of risk influences criminal choices more in those higher in honesty-humility. These models instead suggest that those high in honesty-humility are generally disinclined to engage in criminal conduct, even when perceived sanction certainty and negative affect are low. Collectively considering the mediation and moderation models we report, we suggest that the current data support the mediation relationships proposed by Van Gelder and De Vries (Citation2014) model. This model places perceived sanction certainty and negative affect as mediators of the indirect relationship between personality and criminal choice, and is better supported by the current data than models that consider personality to moderate the relationships between cognitive/affective processes and criminal choices.

The direct relationship between honesty/humility and criminal choice remained robust, when perceived risk of sanction and negative affect were controlled for. Participants who reported no intentions to offend under all scenarios (and all levels of risk) were substantially higher in honesty/humility than those who reported any intention to offend. By excluding these individuals from our main analyses, we almost certainly sacrificed power. The effects predicted by the model of criminal choice are, therefore, probably even larger in the population than the current study suggests. Future studies should also more thoroughly investigate whether there is a threshold of honesty/humility above which perceived risk and negative affect no longer influence criminal choice.

The current findings help reconcile theories about offending propensity with theories about the conditions under which crimes are committed (Piquero & Tibbetts, Citation1996; Wortley, Citation2011). Although we could not manipulate personality traits (Revelle, Citation2007) to examine a causal chain relationship (Pirlott & MacKinnon, Citation2016), we increased both perceived risk and negative affect by experimentally increasing the apparent situational risk. Therefore, by observing the relationship between honesty-humility and the mediators under the high-risk condition, we are able to extend the generality of these relationships (Revelle, Citation2007). We cannot, however, dismiss the possibility that honesty-humility causally influences perceptions of risk and negative affect, or that an as yet unmeasured construct, independently drives both. In addition, although longitudinal data can better support causative associations between variables (Winer et al., Citation2016), a regression analysis revealed a negative association between honesty-humility and prior self-reported offending, which provided indirect evidence that honesty-humility is time-stable.

Examining the mediating relationships in more detail, perceived risk was directly and negatively related to criminal choice in both analyses we conducted (i.e. baseline and high risk). This finding is consistent with rational choice/deterrence theory (Cornish & Clarke, Citation1986), suggesting that when individuals perceive the potential consequences (risk of apprehension) of a criminal opportunity as greater, they are less likely to choose to offend. In the current study and in some previous studies, lower perceptions of risk have facilitated criminal choice (Klepper & Nagin, Citation1989; Nagin & Paternoster, Citation1993, Citation1994; Pickett et al., Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012, Citation2014). Elsewhere, perceptions of risk have not been found to significantly influence offending behavior (Paternoster, Citation1987; Piliavin et al., Citation1986; see also Steele, Citation2016). Most of the impact of perceived risk on criminal choice in the present study was indirect, through negative affect, rather than direct. This is consistent with Pickett et al.’s (Citation2017) results, who found that the effects of perceived risk on intentions to offend were mainly indirect through fear of apprehension. This suggests there is an important affective component in the processes of rational deterrence. This departs from traditional views of deterrence, which views it as largely a cognitive process of weighing the risks of detection and punishment against the benefits of criminal activity (Camerer et al., Citation2005; Loewenstein et al., Citation2001). The current findings are consistent with Pickett et al. (Citation2017), suggesting that individuals who perceive the probability and severity of apprehension as higher, also experience higher levels of negative affect (feelings of fear and insecurity), which in turn lowers their intentions to offend. Further, the significant direct relationship between immediate affect and criminal choice found in both our conditions supports the argument that emotions, evoked at the time of the decision, directly motivate behavior (Loewenstein & Lerner, Citation2003; Pickett et al., Citation2017; Van Gelder & De Vries, Citation2012).

The role of immediate affect in criminal decision-making reveals a potential focus for policies aimed at deterring individuals from engaging in criminal activities. Policies that consider individuals’ emotional reactions may effectively increase the perceived risk of apprehension in real world instances (Pickett & Roche, Citation2016). Aiming to increase the risk of apprehension by increasing actual levels of policing, may not be tractable or successful for all types of offences (Walter et al., Citation2011). In this regard we concur with Pickett et al. (Citation2017) that a policy that focuses on increasing the negative affect, associated with potential crimes (e.g. fear of apprehension), may be effective in reducing crime rates without the need to increase police enforcement levels.

The causal relationships between perceived risk and negative affect, could manifest in the opposite direction to that presumed here. Some scholars have suggested that affect comes prior to, and subsequently directs, judgments of risk (Lerner & Keltner, Citation2000; Slovic et al., Citation2005), while others have argued for bidirectional influences (Loewenstein et al., Citation2001). It is likely that feelings of fear and insecurity occur automatically and rapidly in response to certain situational elements (Slovic et al., Citation2005), and foster increased perceptions of risk. We applied such a model to our current data (reversing the order of the mediators in the serial mediation pathway). The serial pathway remained significant, but the associated effect was an order of magnitude smaller. The influences of perceived risk and negative affect may, therefore, be bi-directional, but the effects of perceived risk on negative affect may have more influence on criminal choices than the reverse effects. Further experimental, and or longitudinal research is required to crystalize the direction of the mediating relationships between perceived risk, affect, and criminal choice.

Limitations and future directions

We note the large and varied sample we recruited and the fact a range of theoretically relevant covariates (age, gender, criminal experience, and punishment experience) were all related to the dependent variable in the direction we expected, which increases our confidence in the overall veracity of these data. We nevertheless acknowledge that hypothetical scenarios measure hypothetical intentions to offend, not actual behavior. While there is evidence to support the predictive, ecological validity of behavioral intentions (Pogarsky, Citation2004), they may not always align with actual behavior in real-life situations (Exum & Layana, Citation2017). Our results may also be limited to the specific type of crimes (e.g. fraud and theft) used in the current study (Exum & Bouffard, Citation2010), or indeed to vagaries of individual vignettes. Combining data across crimes and vignettes, though, provides some insurance against idiosyncrasies of the stimuli cumulatively biasing the results. Hypothetical scenarios may also not evoke emotions in the same way as real-word criminal opportunities (see Exum, & Layana, Citation2017), meaning we are uncertain whether we have reliably captured affective states. However, by instructing participants to place themselves at the time of the decision-making, coupled with the use of scenarios that described relatively common criminal opportunities, the present study has reflected real-world situations, maximizing ecological validity to the best of our method’s ability (Ajzen, Citation1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975).

By using hypothetical vignettes the present study captured the (hypothetical) criminal choices of participants whose (real world) crimes have not been officially recorded, or indeed committed (Thornberry & Krohn, Citation2000). Future research may test the model using both conventional self-report methods and criminal records, in order to examine how well the model accounts for active, as well as hypothetical, offenders. Future studies may also replicate our study in settings designed to evoke emotional reactivity, so there is a greater deviation between emotional and cognitive evaluations. For example, studies may use virtual reality, to measure affective response, similar to that used by Van Gelder et al. (Citation2017; Citation2022). By doing so, the interrelationship between individual propensities and situational factors will continue to be elucidated and this will benefit policy interventions aimed at reducing criminal activity in the community.

Conclusion

The current study tested Van Gelder and De Vries’ (Citation2012) integrated model of criminal choice. We extended the findings of these authors by experimentally manipulating perceived risk of apprehension, and our findings overall provided support for this model. We found the trait of honesty-humility to be related to both perceptions of risk of apprehension and punishment, and negative affect, with individuals high in honesty-humility rating their risk of sanction higher, and also reporting higher levels of negative affect. In terms of the dual process model, the trait of honesty-humility activated both the ‘hot’, affective mode, and the ‘cool’, cognitive mode, in a way that reduced the likelihood of criminal involvement. In addition, we suggest a third pathway by which honesty-humility impacts criminal choice, serially via perceived risk, then negative affect, as appraisals of high risk themselves lead to increased negative affect. Honesty-humility was the primary personality factor implicated in criminal decision-making, and indeed, was the only significant unique predictor of criminal behavior from the HEXACO model in our analyses. Personality, affect, cognition, and situational factors are all evidently implicated in decisions to engage in criminal behavior, and our findings add to research that aims to disentangle the relative contribution of these factors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support this study are available at https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/datasets/understanding-criminal-decision-making-links-between-honesty-humi.

Notes

1 It is possible the relationship between risk assessment and subsequent affective reactions is not linear as we suggest here. For instance, Lerner et al. (Citation2015) argue certain emotional states can trigger changes in the content and depth of thought, as well as implicit goals, and this in turn triggers changes in behaviour. In this conceptualisation, the impact of emotions occurs when they pass a certain threshold. In the current study we argue incremental changes in emotions lead to changes in decision-making. However, we do acknowledge there are different conceptualisations of this relationship. We are grateful to a reviewer for pointing this out.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Allgaier, K., Zettler, I., Wagner, W., Püttmann, S., & Trautwein, U. (2015). Honesty–humility in school: Exploring main and interaction effects on secondary school students’ antisocial and prosocial behavior. Learning and Individual Differences, 43, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.005

- Anwar, S., & Loughran, T. A. (2011). Testing a Bayesian learning theory of deterrence among serious juvenile offenders. Criminology, 49(3), 667–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00233.x

- Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2008). The prediction of honesty–humility-related criteria by the HEXACO and five-factor models of personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1216–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.006

- Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(4), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890902935878

- Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., De Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K., & De Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.356

- Barnum, T. C., & Solomon, S. J. (2019). Fight or flight: Integral emotions and violent intentions. Criminology, 57(4), 659–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12222

- Bouffard, J. A. (2002). The influence of emotion on rational decision making in sexual aggression. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(01)00130-1

- Bouffard, J. A. (2007). Predicting differences in the perceived relevance of crime’s costs and benefits in a test of rational choice theory. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51(4), 461–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X06294136

- Bouffard, J. A. (2015). Examining the direct and indirect effects of fear and anger on criminal decision making among known offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 59(13), 1385–1408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X14539126

- Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2005). Neuroeconomics: How neuroscience can inform economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(1), 9–64. https://doi.org/10.1257/0022051053737843

- Clarke, R. V. (2009). Situational crime prevention: Theoretical background and current practice. In M. Krohn, A. Lizotte, & G. Hall (Eds.), Handbook on crime and deviance (pp. 259–276). Springer.

- Copes, H., Hochstetler, A., & Cherbonneau, M. (2012). Getting the upper hand: Scripts for managing victim resistance in carjackings. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 49(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810397949

- Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (1986). The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending. Springer-Verlag.

- Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2006). The rational choice perspective. In S. Henry, & M. M. Lanier (Eds.), Essential criminology reader (pp. 18–30). Westview Press.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(4), 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668

- De Haan, W., & Voss, J. (2003). A crying shame: The over-rationalized conception of man in the rational choice perspective. Theoretical Criminology, 7(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480603007001199

- De Vries, R. E., De Vries, A., & Feij, J. A. (2009). Sensation seeking, risk-taking, and the HEXACO model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(6), 536–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.029

- De Vries, R. E., & Van Gelder, J. L. (2013). Tales of two self-control scales: Relations with five-factor and HEXACO traits. Personality And Individual Differences, 54(6), 756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.023

- De Vries, R. E., & Van Gelder, J. L. (2015). Explaining workplace delinquency: The role of honesty-humility, ethical culture, and employee surveillance. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.008

- Dunlop, P. D., Morrison, D. L., Koenig, J., & Silcox, B. (2012). Comparing the Eysenck and HEXACO models of personality in the prediction of adult delinquency. European Journal of Personality, 26(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.824

- Ellwanger, S. J., & Pratt, T. C. (2014). Self-control, negative affect, and young driver aggression. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X12462830

- Erke, A., Goldenbeld, C., & Vaa, T. (2009). The effects of drink-driving checkpoints on crashes – A meta-analysis. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 41(5), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2009.05.005

- Exum, M. L. (2002). The application and robustness of rational choice perspective in the study of intoxicated and angry intentions to aggress. Criminology, 40(4), 933–966. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00978.x

- Exum, M. L., & Bouffard, J. A. (2010). Testing theories of criminal decision making: Some empirical questions about hypothetical scenarios. In A. R. Piquero, & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative criminology (pp. 581–594). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77650-7

- Exum, M. L., & Layana, M. C. (2017). A test of the predictive validity of hypothetical intentions to offend. Journal of Crime and Justice, 41(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2016.1244486

- Fine, A., & Van Rooij, B. (2017). For whom does deterrence affect behavior? Identifying key individual differences. Law and Human Behavior, 41(4), 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000246

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Gibbs, J. P. (1975). Crime, punishment, and deterrence. Elsevier.

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/auth/lib/sciences-po

- Hayward, K. (2007). Situational crime prevention and its discontents: Rational choice theory versus the ‘culture of now’. Social Policy & Administration, 41(3), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00550.x

- Hilbig, B. E., & Zettler, I. (2015). When the cat’s away, some mice will play: A basic trait account of dishonest behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 57, 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.04.003

- Intravia, J., Jones, S., & Piquero, A. R. (2012). The roles of social bonds, personality, and perceived costs. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56(8), 1182–1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X11422998

- Jacobs, B. A. (2010). Deterrence and deterrability. Criminology, 48(2), 417–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00191.x

- Jacobs, B. A., & Cherbonneau, M. (2017). Nerve management and crime accomplishment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 54(5), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427817693037

- Jolliffe, D. (2013). Exploring the relationship between the five-factor model of personality, social factors and self-reported delinquency. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.01.014

- Kamerdze, A. S., Loughran, T., Paternoster, R., & Sohoni, T. (2014). The role of affect in intended rule breaking: Extending the rational choice perspective. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51(5), 620–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427813519651

- Klepper, S., & Nagin, D. (1989). The deterrent effect of perceived certainty and severity of punishment revisited. Criminology, 27(4), 721–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb01052.x

- Komulainen, E., Meskanen, K., Lipsanen, J., Lahti, J. M., Jylha, P., Melartin, T., & Ekelund, J. (2014). The effect of personality on daily life emotional processes. PLoS One, 9(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110907

- Leclerc, B., & Lindegaard, M. R. (2018). The emotional experience behind sexually offending in context. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 55(2), 242–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427817743783

- Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(2), 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8

- Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., & De Vries, R. E. (2005). Predicting workplace delinquency and integrity with the HEXACO and five-factor models of personality structure. Human Performance, 18(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1802_4

- Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., & Shin, K. H. (2005). Personality correlates of workplace anti-social behavior. Applied Psychology, 54(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00197.x

- Lee, K., Gizzarone, M., & Ashton, M. (2003). Personality and the likelihood to sexually harass. Sex Roles, 49(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023961603479

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition & Emotion, 14(4), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402763

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

- Lindegaard, M. R., Bernasco, W., Jacques, S., & Zevenbergen, B. (2014). Posterior gains and immediate pains: Offender emotions before, during and after robberies. In Affect and Cognition in Criminal Decision Making (pp. 58–76). https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/auth/lib/sciences-po

- Lochner, L. (2007). Individual perceptions of the criminal justice system. American Economic Review, 97(1), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.1.444

- Loewenstein, G., & Lerner, J. S. (2003). The role of affect in decision making. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective science (pp. 619–642). https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/auth/lib/sciences-po

- Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267

- Lucas, R. E., & Fujita, F. (2000). Factors influencing the relation between extraversion and pleasant affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 1039–1056. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1039

- Malouf, E. T., Schaefer, K. E., Witt, E. A., Moore, K. E., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2014). The Brief Self-Control Scale predicts jail inmates' recidivism, substance dependence, and post-release adjustment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, (3), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213511666

- Matsueda, R. L., Kreager, D. A., & Huizinga, D. (2006). Deterring delinquents: A rational choice model of theft and violence. American Sociological Review, 71(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100105

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- McGrath, A. (2009). Offenders’ perceptions of the sentencing process – A study of deterrence and stigmatisation in the NSW Children’s Court. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 42(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.42.1.24

- Međedović, J. (2017). The profile of a criminal offender depicted by HEXACO personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.015

- Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2001). Structural models of personality and their relation to antisocial behavior: A meta-analytic review. Criminology, 39(4), 765–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00940.x

- Nagin, D. S., & Paternoster, R. (1993). Enduring individual differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law and Society Review, 27(3), 467. https://doi.org/10.2307/3054102

- Nagin, D. S., & Paternoster, R. (1994). Personal capital and social control: The deterrence implications of a theory of individual differences in criminal offending. Criminology, 32(4), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1994.tb01166.x