ABSTRACT

The Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPDP) was co-commissioned in 2011 to better manage high-risk offenders likely to have a personality disorder. Within the OPDP, forensic case formulation is used to develop a psychological understanding of each offender’s criminal behaviour, clinical problems, and criminogenic needs. Each formulation concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at addressing the problems and needs identified. However, no research has yet investigated the effectiveness of these recommendations. To address this, the present study used a multiple case-study method to investigate the effectiveness of recommendations generated within 10 OPDP formulations. Two sets of cases were examined: 5 with positive outcomes, and 5 with negative outcomes (known as a ‘two-tailed’ multiple case study). When these two sets of cases were compared, a clear pattern of differences emerged in the relevance, feasibility, utility, and impact of the formulation recommendations made (in favour of cases with positive outcomes). On the basis of these results, a provisional logic model was developed to operationalise the process by which formulation recommendations were hypothesised to have contributed to outcomes in ‘positive’ cases, and where and why this process commonly deteriorated in ‘negative’ cases. Implications of these results and avenues for further study are discussed.

Introduction

Addressing the needs of high-risk individuals with possible personality disorder has been a challenge facing criminal justice and forensic mental health settings for many years. Within the UK, governments have sought to use legislation to develop services in response to high profile cases. For instance, the introduction of Sentences of Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPPs) in 2005 was a legislative attempt to enable the justice system to manage potential risk through indeterminate custodial sentences, although using this sentencing option ceased in 2012 due to the coalition government terming it ‘non-defensible’ (Sturge & Beard, Citation2019). Similarly, DSPD services were established in 2002 (within mainly custodial and secure forensic inpatient settings) to enable interventions to be developed and delivered for high-risk individuals meeting the inclusion criteria. DSPD services were decommissioned in 2011 following indications of lacklustre short-term outcomes that could not justify the allocated costs (Barrett & Tyrer, Citation2012). Following this, DSPD resources were re-utilised by the National Offender Management ServiceFootnote1 (NOMS) and the National Health Service (NHS) in a ‘more effective and efficient way’ to create the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPDP). The aim of the OPDP is to manage and treat high-risk offenders likely to have a personality disorder (Joseph & Benefield, Citation2012) in order to reduce repeat offending, improve the psychological health of offenders, and increase public protection (National Offender Management Service & NHS England, Citation2015a). Currently, many offenders screened into the OPDP receive a bespoke package (or ‘pathway’) of management and treatment interventions, typically informed by an individualised case formulation.

Case formulation has been described as a ‘hypothesis about the causes, precipitants and maintaining influences of a person’s psychological, interpersonal, and behavioural issues’ (Eells, Citation2007, p. 4). Within the OPDP, case formulation is therefore used to gain a psychological understanding of each offender’s criminal behaviour, clinical problems, and criminogenic needs (Joseph & Benefield, Citation2012). Each OPDP formulation concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at reducing and addressing the problems and needs identified.

Although case formulation has been a core competency within clinical practice for many years (Division of Clinical Psychology, Citation2011), it has only recently been explicitly incorporated into forensic services such as the OPDP. Within the OPDP, the process of formulating a case typically begins with a case consultation meeting, attended by both the offender manager (OM) and a psychologist (without the offender present). Through discussion and collaboration, these meetings aim to improve the OM’s understanding of the case and to identify appropriate methods for the OM to best facilitate progress within the case (Knauer et al., Citation2017). After the consultation meeting has taken place, the psychologist produces a written case formulation using the information discussed within the meeting.

Uniquely, three different ‘levels’ of written case formulation are produced within the OPDP, which represent different levels of complexity. These formulation levels were introduced within the OPDP as a way of ‘providing formulations flexibly in response to widely divergent contexts and practitioner needs’ (NOMS & NHS, Citation2015b, p. 40). Level 1 formulations are the simplest, often consisting of a brief written understanding of an offender’s main presenting problem/s. Level 2 formulations are often more detailed, making more psychological connections between pieces of information to explain how and why the offender’s presenting problems may have developed. Level 3 formulations are the most complex, often incorporating information gained from formal assessments to develop a comprehensive understanding of the offender as a whole (including their presenting problems) by applying the use of an empirically supported psychological theory (Logan, Citation2017; NOMS & NHS, Citation2015b).

Whilst a small pool of research has now attempted to assess the quality and utility of formulations produced within forensic services (known as ‘forensic case formulation’; see Wheable & Davies, Citation2020, for a review of this research), none of this research has focused on assessing or evaluating the recommendations resulting from these formulations. Factors such as the relevance, feasibility, utility, and impact of formulation recommendations are, however, likely to influence the overall value of each formulation, suggesting that this is an important topic to explore.

Current study

The main aim of this study was to explore the relevance, feasibility, utility, and impact of recommendations made within level 2 OPDP formulations. A secondary aim of the study was to use these findings to develop a logic model displaying the process by which formulation recommendations may (or may be unable to) influence case outcomes. Approval for the study was granted by both HMPPS National Research Committee (ref. 2020-077) and University of Swansea ethics committee (ref. 4891).

Materials and methods

Design

A case-study design was used, making it possible to ‘explain the presumed causal links in real world interventions that are too complex for experimental methods’ (Yin, Citation2018, p. 18). A multiple (rather than single) case-study was performed, enabling the findings of individual case-studies to be compared, creating richer ‘cross-case’ conclusions (Burns, Citation2010).

Yin (Citation2018) describes the concept of a ‘two-tailed’ multiple-case-study in which two groups of cases can be compared (i.e. one group for which an intervention was delivered, and one group for which it was not). The present study adapted this approach to identify any observable differences in the relevance, feasibility, utility, or impact of formulation recommendations made in cases which resulted in ‘positive’ outcomes versus cases which resulted in ‘negative’ outcomes.

Participants

Due to research restrictions relating to COVID-19, the study was conducted using pre-existing data on National Probation Service (NPS) systems. These systems contain a log of ‘every occurrence, event, or face-to-face contact relevant to an offender’ (Beaumont Coleson Software & System Solutions, Citationn.d, p. 2). These systems also contain case formulations, parole reports, psychological evaluations, risk reports and calculations, and service referrals. Entries contained within these databases constitute the official record of proceedings within each case.

Number of cases

Yin (Citation2018) recommends that when performing a two-tailed multiple-case-study, at least two cases from each ‘tail’ should be examined, but five or six cases from each tail are likely to provide a high degree of certainty in the results obtained. Consequently, 10 cases were examined; five of which had ‘positive’ outcomes, and five of which had ‘negative’ outcomes.

Case selection

To select these 10 cases, a set of inclusion criteria was devised (). A dataset containing all active cases on the Wales OPDP caseload between 2018–2019 was acquired from the Welsh OPDP Data and Evaluation Officer. Each case within this file was allocated a random number using the RAND Microsoft Excel function before being sorted into ascending order. Each case was then assessed in turn against the inclusion criteria. For each case meeting these criteria, information contained on NPS databases was accessed to ascertain whether the outcome of the case had been ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. This process continued until five cases with ‘positive’ outcomes and five cases with ‘negative’ outcomes were identified.

Table 1. Inclusion Criteria.

Cases with ‘positive’ outcomes were defined as those in which the offender had no record of breaching their licence conditions or receiving any warnings within one year following formulation. Cases with ‘negative’ outcomes were defined as those in which the offender was recalled to prison within one year following formulation. By selecting cases from these two extremes (i.e. those with ‘very positive’ outcomes and those with ‘very negative’ outcomes), it was expected that any meaningful differences in the relevance, feasibility, utility, or impact of formulation recommendations would be more easily identified.

Each of the 10 selected cases represented a maleFootnote2 between the age of 25-50. All had a history of committing violent and/or sexual offences, and in all but one case, the index offence was also violent (the remaining one was sexual). Each had been flagged by their offender manager as requiring consultation and formulation. Prior to consultation and formulation, all had been placed in either the ‘Medium’ or ‘High’ Risk of Serious Harm Category (RoSH)Footnote3 (one ‘Medium Risk’ offender in each group).

Three of these offenders were in custody at the time of their formulation and were subsequently released within the one-year period following this; two of them were recalled to custody within this same year, resulting in ‘negative’ outcomes, whilst one of them had a ‘positive’ outcome and remained within the community.Footnote4 The remaining seven offenders were already in the community at the time of their formulation; three of them were recalled to custody in the one-year period following this, resulting in ‘negative’ outcomes, whereas four of them had a ‘positive’ outcome and remained within the community.

Procedure

Data collection procedures were carried out in accordance with case-study guidance developed by Yin (Citation2018). A case-study protocol was first developed, which included a list of key questions to be answered about each case accompanied by likely sources and locations of file-based evidence to address these questions (). To safeguard against possible unconscious bias during the data collection process, outcome information relating to each case (i.e. positive versus negative) was then removed from the dataset and the 10 cases were randomised. The first case examined was treated as a ‘pilot’ case-study, used to test the proposed data collection procedure. After discussion with the research team, it was agreed that this pilot case study indicated no considerable changes to the protocol were needed, and so this case was retained within the final dataset. Data collection for each remaining case then proceeded as follows:

Data collection

For each of the selected cases, the associated formulation was first accessed and examined in detail, with a particular focus on the recommendations made. To gain the context needed to judge the relevance of the recommendations (i.e. whether each recommendation matched a specific risk or need of the offender as described within case records), all case records made within the 6-month period preceding the formulation were accessed and examined. To judge the utility and impact of these recommendations (i.e. whether each recommendation was completed and whether this in turn had an impact on 1-year case outcomes), all case records made within the 1-year period following the formulation were accessed and examined.

Each piece of information of potential importance was logged in a ‘case-study database’ created in Microsoft Excel. When complete, this database contained a detailed overview of each case; descriptions and locations of each piece of information accessed; and initial thoughts about how this information could be used to answer key questions within the case-study protocol. The use of a case-study database enabled a detailed chain of evidence to be created, ensuring that later conclusions could easily be traced back to the evidence that they were based upon (Yin Citation2018).

Data analysis by case

For each case, information logged within the evidence database was re-read several times to develop familiarity and to identify initial patterns and insights. Key protocol questions were then answered sequentially (). To answer smaller/more straightforward questions (i.e. ‘What evidence is there that the recommendations made within the formulation were implemented or actioned?’), the case-study database was examined to identify any evidence that may be relevant to the question (e.g. searching for referral reports to ascertain whether recommended referrals were made). Tentative conclusions were then drawn from these findings. Wherever possible, each conclusion made was based upon more than one source of evidence (data triangulation).

For more complex key questions (i.e. ‘Did the case formulation recommendations have an impact on case progression? If so, how? If not, why not?’), all relevant information identified within the evidence database was sorted into chronological order, using the date as it was recorded on the NPS database. Visual displays and flowcharts also aided in this process. This method provided an understanding of which events were likely to have impacted case progression, based on the weight of all available evidence (i.e. identifying ‘presumed causal sequences’, Yin, Citation2018, p. 231). This process of examining and analysing information was repeated until all key questions outlined in the study protocol had been sufficiently answered for each of the 10 cases.

Within-group analysis

The main aim of a multiple-case-study is to develop a broad explanation that fits all cases generally, even though the specific details of individual cases will vary (Yin, Citation2018). After restoring case outcome information into the dataset, cross-case analysis was therefore performed next, starting with the findings of the five cases with ‘positive’ outcomes. This was done to identify any cross-case patterns in the relevance, feasibility, utility, or impact of the recommendations made within the formulations associated with these cases. This process began with a set of initial hypotheses formed from the findings of the first case, which were then developed and updated as evidence from each of the additional four cases with positive outcomes were considered. This process was then repeated for the five cases with ‘negative’ outcomes.

Between-group comparison

Overarching conclusions resulting from each group of cases (positive and negative) were then compared to each other identify any observable between-group differences in the relevance, feasibility, utility, or impact of formulation recommendations.

Analytical framework

To perform the cross-case analysis, a range of analytic techniques were used. As described earlier, the first technique used was chronological sequencing. This technique is useful for investigating causal relationships, because when examining events chronologically, ‘the basic sequence of a cause and its effect cannot be temporally inverted’ (Yin, Citation2018, p. 184). Within the present study, arranging events in chronological order enabled investigation of how the formulation recommendations may have impacted the outcome of each case (e.g. by identifying whether the formulation recommendations altered the way in which the case was being managed).

Chronological sequencing additionally facilitated the use of the ‘explanation building’ analysis technique (Yin, Citation2018), which involves gradually building an explanation of a case to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a certain outcome was achieved. The goal of this explanation building technique is to develop a set of hypotheses about causal sequences which can then be confirmed with further (possibly experimental) study. Within the present study. this involved examining whether the recommendations made within each formulation contributed to the outcome of each case, and if so, what the ‘causal sequence’ was behind this.

Chronological sequencing also facilitated the use of the ‘logic modelling’ analysis technique, which involves the ‘operationalisation of a complex chain of occurrences or events over an extended period of time, trying to show how a complex activity, such as implementing a programme, takes place’ (Yin, Citation2018, p. 186). Logic modelling takes chronological sequencing one step further, aiming to show how the outcome of one event can cause the next event to happen, which in turn can produce its own outcome (cause–effect-cause patterns, Yin, Citation2018). Logic modelling can be used as an evaluative tool (Morgan-Trimmer et al., Citation2018), aiding understanding of ‘what works and why’ (Kellogg Foundation, Citation2004, p. 1). This technique was highly relevant for use within the present study, as it is likely that if formulation recommendations can impact overall case outcomes, this will be through indirect or cumulative means, with recommendations first impacting smaller or more immediate outcomes (e.g. the offender manager’s methods of managing the offender) which in turn then impact larger and more longer-term outcomes (i.e. 1-year case outcomes).

Results

Number of recommendations

On average, slightly more formulation recommendations were made in cases which had positive outcomes than negative outcomes (eight versus six recommendations). The number of recommendations made in cases with positive outcomes ranged from 6-10, whereas the number of recommendations made in cases with negative outcomes ranged from 5-6.

Relevance of recommendations

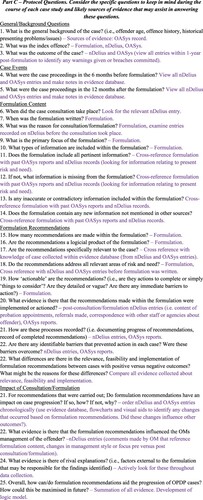

Included recommendations

As previously described, each formulation recommendation was assessed according to whether it matched a specific risk or need of the offender as documented within case records (6-months prior to formulation). Each recommendation was then sorted into one of three categories: ‘highly relevant to the case’ (clearly aimed to address a current risk or need of the offender as documented within case records), ‘moderately relevant to the case’ (broadly relevant but did not aim to address a specific risk or need of the offender as documented within case records), or ‘not a recommendation’ (described an action already taken prior to the formulation). There were no instances identified where a recommendation was ‘not relevant at all’.

When comparing these categories across cases, it was found that only those with negative outcomes (three of these cases) included formulation recommendations fitting into the third category (‘not a recommendation’). On average, slightly more ‘highly relevant’ formulation recommendations were made in cases which had positive outcomes than cases which had negative outcomes (five versus four highly relevant recommendations; see ).

Figure 2. Boxplot Displaying the Number of Relevant Formulation Recommendations Made within Cases with Positive Versus Negative Outcomes.

Note: ‘Unaddressed Issues’ refer to particular areas of risk or need identified in each case which would have been relevant to address within the formulation recommendations but were not.

Absent recommendations

Investigation was also made into whether there were any particular areas of risk or need in each case which may have been relevant to address with a formulation recommendation but were not. At least one such area was identified within each case, including substance abuse issues, lack of accommodation, violence in relationships, pro-criminal attitudes, and mental illness. More unaddressed issues were identified in cases with negative outcomes than in cases with positive outcomes (three versus two unaddressed issues on average; see ) It is possible that these issues were not addressed within the formulations due to an assumption that they would be addressed by other services (i.e. alcohol and drug services, housing authorities). However, psychological causes for substance misuse were often identified and discussed within case records, suggesting that these issues, at least, would have been appropriate to address. This point is strengthened by a quote from one offender (Case 6), who was documented (by his offender manager) as stating that the substance misuse service was only there to drug test him, and not to help him complete any ‘meaningful work looking at why he uses substances’.

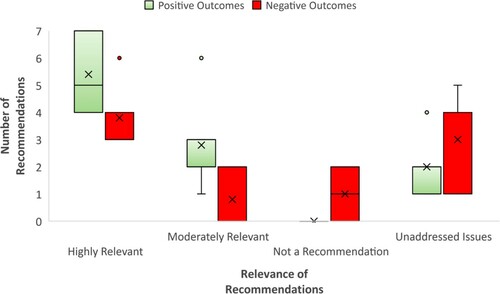

Feasibility of recommendations

To assess the feasibility of the recommendations (i.e. how feasible they were for the offender manager to action), two factors were considered; whether each recommendation was specific or concrete enough to action (i.e. whether the action to take was clearly defined), and whether each recommendation was possible to action (i.e. whether there were any known barriers to action at the time of formulation).

All recommendations were again sorted into one of three categories: ‘highly feasible’ (outlined a specific action to take and clear instruction on how to go about this), ‘moderately feasible’ (outlined an action to take, but not any instruction or clarification on how to go about this), or ‘not feasible at all/not a recommendation’ (not possible to action). An example of a recommendation fitting into the third category was one which advised the offender manager to complete some work with the offender once he had been accepted into a particular service, but this referral was subsequently rejected. The formulation was updated to note this, but no recommendation was made in its place (Case 7).

When comparing these categories across cases, it was found that many more ‘highly feasible’ formulation recommendations were made on average in cases which had positive outcomes than in cases which had negative outcomes (seven versus three highly actionable recommendations; see ).

Figure 3. Boxplot Displaying the Number of Feasible Formulation Recommendations Made within Cases with Positive Versus Negative Outcomes.

Differences were also observed between the two sets of cases (positive vs negative) in terms of the language used to describe recommendations. All except two of the 31 recommendations made across the five cases with positive outcomes instructed that an action should occur. Two of these cases also organised the recommendations in terms of their priority. In contrast, recommendations made across the five cases with negative outcomes often only suggested actions that could occur. In one of these cases, the recommendations section was also preceded by a note stating: ‘these are not intended as recommendations but rather as suggestions to consider’. None of the cases with negative outcomes organised formulation recommendations in terms of their priority.

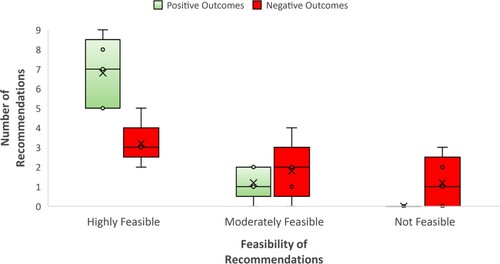

Utilisation of recommendations

To understand whether these two different approaches may have led to differences in the utilisation of recommendations, an investigation was next made into whether these recommendations were actioned or not (within the 1-year period post formulation). Again, each recommendation was sorted into one of three categories: ‘fully utilised’ (clearly evidenced as having been actioned), ‘partially utilised’ (evidenced as having been attempted in part), or ‘no evidence of utilisation’ (no evidence at all that the action had taken place).

When comparing these categories across cases, it was found that many more recommendations had been ‘fully utilised’ on average in cases with positive outcomes than in cases with negative outcomes (four versus one fully completed recommendation/s; ).

Figure 4. Boxplot Displaying the Number of Formulation Recommendations Utilised within Cases with Positive Versus Negative Outcomes.

This difference in the number of ‘fully utilised’ recommendations cannot simply be explained by those offenders in cases with negative outcomes being recalled to prison before the recommendations were completed. This is because within each of the five cases with negative outcomes, offenders were not recalled to custody (on average) until five months after the formulation was completed (range: 2–10 months), indicating that offender managers likely had sufficient time to put at least the most important formulation recommendations into action. In addition, when examining cases with positive outcomes, it was found that in the majority of instances where recommendations had been ‘fully utilised’, these recommendations had been completed within the initial period following formulation (33 days post-formulation on average).

To understand whether this difference in utilisation was instead due to cases with negative outcomes having fewer relevant and feasible formulation recommendations to act upon as compared to cases with positive outcomes, this was investigated. It was identified that although fewer relevant and feasible formulation recommendations had been made within negative cases overall, the proportion of recommendations assessed as being both highly relevant and highly feasible was relatively similar between the two groups of cases (56% versus 54%). When looking at relevance, feasibility, and utilisation combined, it was found that 65% of all highly relevant and feasible recommendations were fully completed in cases with positive outcomes, compared with only 26% of highly relevant and feasible recommendations in cases with negative outcomes.

Consequences of inaction

For cases with negative outcomes, in many instances, recommendations that may well have had the potential to positively impact case outcomes were not carried out. To understand whether this could be attributed to barriers faced when attempting to complete these recommendations, these cases were further examined in this regard. In many of these cases, however, no particular barriers were identified. Two case examples are provided to demonstrate this:

Example 1 – Consequences of Inaction (Case 6 – Negative Outcome)

One of the recommendations made within this formulation was for the offender manager to encourage and enable the offender to partake in meaningful activity. The offender was described (within an entry recorded on the NPS database) as being agreeable to this suggestion, requesting to be allowed to pursue employment or to be referred to an employability service. However, no evidence was found to suggest that these requests were facilitated, and a subsequent database entry made by the offender manager stated that she believed the offender should spend more time settling into the community before taking on employment. Within a month of being released, the offender was documented as having raised some concerns with his offender manager, stating that he was often bored and had nothing to do except drink alcohol, which was related to his risk of offending. The offender was subsequently recalled to custody due to attending appointments whilst under the influence of alcohol.

Example 2 – Consequences of Inaction (Case 7 – Negative Outcome)

One of the recommendations made within this formulation was that the offender manager should collaboratively construct a relapse prevention plan with the offender before his release from custody. As the offender’s risk of reoffending was related to his use of substances to deal with childhood trauma, the aim of this relapse prevention plan was to identify triggers that he was likely to encounter in the community, and to identify early warning signs that may be indicative of an imminent relapse. However, no evidence was found to suggest that this relapse prevention plan was ever discussed or developed. The offender was later recalled to custody as a result of relapsing into substance abuse due to feeling unable to cope with flashbacks of childhood trauma. The offender later described to his offender manager that these flashbacks had returned when he ran out of medication and developed insomnia, which are clear early warning signs that could have been better managed and potentially mitigated with the use of a relapse prevention plan.

To provide comparison, unactioned recommendations in cases with positive outcomes were also examined (although these were far fewer in number). It was identified that (in contrast to cases with negative outcomes), where highly relevant and feasible recommendations were not fully utilised in positive outcome cases, there was typically some valid reason for this such as an insurmountable barrier. Typically, the offender manager also attempted to overcome the barrier with the use of alternative methods, often achieving the intent of the recommendation by other means. Again, case examples are provided to demonstrate this:

Example 1: Overcoming Barriers to Action (Case 5 – Positive Outcome)

One of the formulation recommendations instructed the offender manager to try to develop a relationship with the parent of the offender. The reason for this was to better monitor the offender’s developing romantic relationships (relationships being a significant risk factor for the offender in this case). However, the offender manager was unable to complete this recommendation due to the parent falling ill soon after the formulation was written. To compensate for this, the offender manager instead developed a relationship with the offender’s sibling, and also made sure to question the offender regularly about any relationships he may be developing.

Example 2 – Overcoming Barriers to Action (Case 2 – Positive Outcome)

One formulation recommendation advised that the offender manager (OM) should try to gain a commitment from the offender to attend all future probation appointments sober. Although the offender was not motivated enough to make this commitment, the OM was aware that in order to have contact with his daughter, the offender was required to provide clean tests at his alcohol service appointments. The OM therefore first completed another of the formulation recommendations; to complete motivational interviewing with the offender to encourage him to provide clean weekly tests at the alcohol service. The OM then liaised with this alcohol service to ensure that probation appointments would always be scheduled immediately before alcohol service appointments, thereby increasing the likelihood that the offender would attend probation appointments sober.

Impact of recommendations

The impact of recommendations that were utilised in positive cases was examined, specifically, did the actions actually contribute to the positive case outcome that was achieved? A number of instances were identified where utilised recommendations were seen to have likely contributed to the outcome of the case, typically acting as a ‘springboard’ to further action, by first improving the offender’s engagement or compliance. Two such examples are provided:

Example 1 – Impact of Utilisation and Follow-Up (Case 4 – Positive Outcome)

Prior to formulation, the offender manager (OM) of this case reported that the offender had been ‘pushing boundaries’ in supervision due to wanting his reporting frequency reduced and wanting to go on holiday. Within the formulation, it was hypothesised that this may have resulted from the offender’s misunderstanding of his licence conditions and at what point these would end. In response to this, two of the recommendations made within the formulation were (a) for the OM to revisit each licence condition in detail with the offender and to reinforce the reasons for their implementation, and (b) to use a supportive authority approach to empower the offender to make his own choices and to take responsibility for the consequences of these choices. The OM recorded on the NPS database that in the first supervision session post-formulation, she had successfully explored each licence condition in detail with the offender and had explained the work she would like to complete with him. She reported that she had also explained to the offender that although it was his own choice to comply and engage with this work, if he did so, she would be willing to reduce his reporting frequency. The offender was reported as being agreeable to this proposition. After this supervision session, the offender was described as engaging well in the work provided, and as having an improved understanding of his licence conditions. After two months of continued engagement, the OM was able to reduce the offender’s reporting frequency as promised. Soon after this, the offender disclosed that although the holiday he had wished to take was happening that week, he had declined his invitation as he did not want to breach his licence conditions. Five months after the formulation was written, the OM recorded an entry on the probation database to say that the offender’s engagement and compliance over the previous months had been ‘excellent’.

Example 2 – Impact of Utilisation and Follow-Up (Case 2 – Positive Outcome)

The offender in this case suffered from short term memory issues caused by long term alcohol dependency. Prior to formulation, these memory issues resulted in the offender missing many appointments, eventually leading to his disengagement with probation and other services. Although the offender manager (OM) of this case did try to improve the offender’s attendance pre-formulation by occasionally sending text message reminders, these reminders were often forgotten or sent too late. The offender was then told that sending reminders for appointments was not a sustainable solution and that he should try harder to organise his own time and remember these appointments himself. One of the formulation recommendations instead advised that the offender should be sent text message reminders before every appointment to try to increase his engagement. This recommendation was immediately actioned by the OM, who sent three different text message reminders prior to his next appointments. The offender attended these appointments successfully. In the year following formulation, the OM continued with this method, and also recorded an entry on the NPS database stating that she had asked other services working with the offender to send text message reminders to ensure he also attended his other appointments. The OM also liaised with these additional services to ensure that all the offender’s appointments were scheduled for the same day each week, reducing the amount of information he had to remember. The result of this effort on the OM’s part was that the offender only missed a single appointment in the year following formulation, and this was due to a change in his scheduled appointment day owing to the Christmas holidays.

In contrast, when examining the impact of recommendations utilised in cases with negative outcomes, it was found that in many instances the completion of these recommendations did not have the positive impact intended. In several instances, although these recommendations were seen to have an initial positive impact, lack of further action or follow-up resulted in these impacts being diminished. Again, two case examples are provided below to demonstrate this:

Example 1 – Impact of Utilisation with Lack of Follow-Up (Case 9 – Negative Outcome)

Within this case, the majority of the offender’s criminal behaviour had been alcohol related. Previously, the offender had engaged well with an alcohol service until he was allocated to a different staff member and stopped engaging. One of the formulation recommendations was therefore for the offender manager (OM) to consider re-contacting this alcohol service to ask if the offender could be re-allocated to the original staff member.

Although the OM did not utilise this recommendation immediately, she did so once the offender’s drinking had become problematic again (i.e. the offender stopped attending probation appointments due to being under the influence). Due to this recommendation, the offender was eventually allocated to the original staff member at the alcohol service and engaged well for a period of time, during which he also successfully attended his probation appointments.

After three months, the alcohol service told the OM that they had not heard from the offender recently and wondered if he still needed support. The OM discussed this with the offender in his next probation appointment, before recording on the probation database that the offender felt he no longer needed support as he was employed and no longer drinking. Within this entry, the OM described that she was agreeable to this, and so had only requested that the offender re-contact the alcohol service if his situation should change again. Soon after this, the offender was recalled to custody due to committing a further offence during which he was intoxicated.

Example 2 – Impact of Utilisation with No Follow-Up (Case 10 – Negative Outcome)

The offender was in custody at the time of formulation. He was described by his OM as feeling extremely anxious about being released, having previously stated that he was desperate for support in the community and would rather commit suicide than return to prison. Due to his anxiety, the offender had previously acted out inappropriately to try to gain a sense of control in certain situations (e.g. starting a fight in order to be moved to a different prison). A formulation recommendation was therefore made for all staff working with this offender to try to identify and explore the emotions he feels when he is struggling, with the aim of developing his communication skills and decreasing his need to act out.

The offender’s prison keyworker utilised this recommendation when the offender began to struggle emotionally. Within a NPS database entry, the keyworker reported that she spent time exploring the offender’s feelings about being released, and what he could do to better manage these feelings instead of acting out inappropriately. The initial outcome of this conversation was positive; the keyworker reported that the offender had engaged well in this conversation and had expressed afterwards that he felt he could trust this keyworker. However, within the same entry, the keyworker also stated that she believed it was important for the offender to receive further support from other sources in relation to this issue to ‘keep his head straight and out of trouble’.

Once released into approved premises two months later, the offender was described as having disclosed to staff that he has ‘great difficulty with regulating emotions’ and relies on isolating himself so that he is not recalled to prison. However, no evidence was found to suggest that this discussion was followed up with any further work or dialogue around managing emotions. After one month in approved premises, the offender was described as becoming overly worried and upset about having missed a scheduled appointment with his offender manager. The offender then absconded and attempted suicide, leaving a note which stated that he would rather die than return to prison. The offender was recalled to custody soon after this.

These two case examples highlight that it is not always sufficient for formulation recommendations to be relevant, feasible and utilised; but that the initial impacts of utilising these recommendations must also be closely monitored and further developed to achieve continuation of this positive progress.

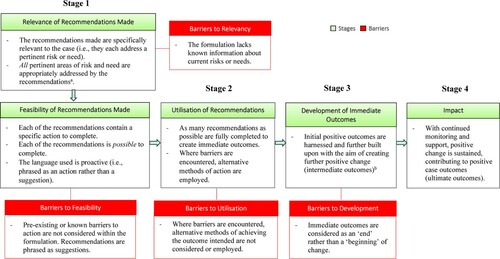

Logic Model

A logic model is a visual representation of ‘a chain of occurrences or events over an extended period of time, trying to show how a complex activity, such as implementing a programme, takes place’ (Yin, Citation2018, p. 186). To achieve this, logic models commonly showcase the theorised relationship by which an initial intervention or activity first produces its own immediate outcomes, which can in turn create intermediate outcomes, finally resulting in ultimate outcomes (cause–effect-cause patterns, Yin, Citation2018).

A logic model was therefore developed to operationalise the process by which formulation recommendations were theorised to have indirectly contributed to positive 1-year case outcomes in positive cases (). This model also indicates where and why this process commonly broke down in cases with negative outcomes, negating the intended impact of the recommendations made.

Figure 5. Logic Model Operationalising the Process by Which Formulation Recommendations May Influence Outcomes.

Note. The impact of each step is dependent on the successful completion of all prior steps in the chain. aIt may also be helpful for these recommendations to be prioritised so that those of most importance can be easily identified by the OM. bThis may also involve re-visiting the formulation to generate further recommendations.

Discussion

The logic model resulting from this two-tailed multiple case-study offers a useful overview of the value that formulation recommendations can provide within the OPDP when they are highly relevant, highly feasible, fully utilised, and appropriately followed-up. These findings could provide the basis of a useful addition to guidance presently offered by the OPDP, which focuses on what a high-quality formulation should contain (i.e. Case and Risk Formulation Self-Auditing Tool, NOMS & NHS, Citation2015b), rather than how to actively generate useful and impactful (i.e. relevant, feasible, and utilisable) recommendations.

The consistency of the differences found between these two sets of cases (i.e. recommendations made in cases with positive outcomes were more likely to be highly relevant, highly feasible, fully utilised, and appropriately followed-up) do suggest that the recommendations made within a forensic case formulations can have an influence on case outcomes. These findings therefore highlight the need for further focus on this topic within the OPDP and wider forensic services, and also emphasise the value of using a case-study approach.

The finding that at least one unaddressed issue was identified in each case, regardless of outcome, is indicative of a wider issue. For instance, although substance misuse issues were identified (via case records) as relating or contributing to offending behaviour within nine of the 10 cases examined (and also described as stemming from psychological issues or trauma in many instances), only one of the formulations associated with these cases included a recommendation aimed at addressing substance misuse issues (Case 5 – positive outcome). It is therefore advised that when generating formulation recommendations in future, all of the currently relevant risks and needs of each offender are considered, rather than only the most unique or complex ones.

The differences identified in the language used to describe formulation recommendations between cases with positive and negative outcomes is indicative of a difference in the purpose of generating these formulation recommendations. In cases with positive outcomes, this purpose was conveyed as being to identify appropriate next steps for the offender manager to take in order to manage/continue to manage the case effectively. In cases with negative outcomes, this purpose was instead conveyed as being to initiate thought around what could work or what might be effective in managing the offender, which the offender manager could then further consider at their own discretion. This might have contributed to the lower completion rate of recommendations in cases with negative outcomes, suggesting that when generating formulation recommendations in future, close attention should be paid to the language used.

A further important finding identified is that when faced with a barrier, OMs within positive cases often compensated for this by using alternative methods to achieve the intent of the recommendation. In cases with negative outcomes, recommendations were much less likely to be completed, even in the absence of any identifiable barrier. This suggests that targeted training should be provided to OMs to equip them with the necessary problem-solving skills to implement recommendations more effectively.

This two-tailed multiple case study has also identified that successful completion of formulation recommendations is often only the first step. Importantly, the initial positive impacts of completing these recommendations must then be harnessed and further developed to create further positive progress. For instance, it is recognised that the formulation recommendations earlier described within the ‘positive’ case examples were seemingly more practical or ‘surface-level’ in nature (i.e. ‘send text message reminders’ and ‘explain licence conditions’), rather than having an explicit psychological or risk related-focus. However, these examples highlight that formulation recommendations can be effective in first identifying and removing barriers to engagement and compliance, which is often the first step towards the ultimate goal of risk-reduction. This also highlights the benefits of ordering recommendations according to their priority, as was done in a number of the cases with positive outcomes; once barriers to engagement are removed, subsequent recommendations (i.e. those directing risk-management or intervention) can then be implemented. These examples also indicate that when formulation recommendations are highly practical and actionable, OMs are likely to be able to implement these more effectively, leading to more positive impacts. However, it may be helpful and important in future for the intent or purpose of these more ‘practical’ formulation recommendations to be made more explicit to OMs by connecting the recommendation to its ultimate goal of risk management. For instance, ‘the purpose of X (e.g. send text message reminders) is to increase Y (offender engagement), contributing to the ultimate goal of Z (risk-reduction)’. The impact of writing recommendations in this way could be reviewed with future research, and if helpful, could be reflected in the preliminary logic model presented here. This approach could also readily be rolled out to other services and settings.

The use of a case-study method might be seen as a limitation in some regards (as it was possible to examine only a few cases). However, Yin (Citation2018) likens each individual case-study to an entire experiment (replication logic) rather than a single participant within a study (sampling logic). This is because a full analysis is performed on each case (potentially involving the examination of hundreds or thousands of pieces of information), creating valuable hypotheses which can then be compared across cases. The use of a two-tailed design (i.e. examining cases with positive versus negative outcomes) is also likely to have strengthened the validity of the results obtained, as the theorised process by which formulation recommendations can contribute to outcomes in positive cases could be ‘tested’ by understanding whether this hypothesised process broke down in each of the negative cases. However, as the 10 cases were selected from Welsh OPDP teams, it would be useful for future research to ensure that these findings are representative of OPDP services more broadly.

It is important to stress that the barriers presented within the logic model are those that might have reasonably been avoided (e.g. low relevance, low feasibility, barriers to action that could likely have been overcome). However, it is also important to note that because they were not assessed within the present study, it is possible for alternative (non-formulation related) factors to have had some influence on the results found. For instance, the strength of the OM-offender relationship in each case may have impacted the OM’s ability or motivation to complete the recommendations made. This is something that should be explored with further study.

To maximise reliability, the variables to be rated and the criteria by which these were to be rated were clearly defined within the study protocol document before data collection began. The allocation of recommendations into each category (i.e. highly feasible, moderately relevant) was also recorded and compared throughout the study to ensure that the reasons behind these allocations remained consistent. However, it is important to note that only the primary researcher (a PhD candidate funded to complete the project) was involved in assessing the formulation recommendations in terms of their relevance, feasibility, and utility (meaning that no measure of inter-rater reliability is available). This is not necessarily a limitation, as McDonald, Schoenbeck and Forte (Citation2019) argue that ‘agreement (formal or informal) is rarely appropriate when a single researcher with unique expertise and experience is conducting the research’. To further improve reliability, potential rival explanations for the findings were considered (and subsequently rejected) throughout the study, and the logic model resulting from these findings was also critically examined by other researchers working within the OPDP before being finalised.

One carefully considered rival hypothesis was that those with ‘positive’ outcomes already significantly differed to those with ‘negative outcomes’ with regard to their pre-formulation offending characteristics or risk. However, no noticeable differences were identified; all had been flagged by their offender manager as requiring a consultation and formulation, all had been placed in the ‘Medium’ or ‘High’ Risk of Serious Harm Category (RoSH) prior to their formulation (one ‘Medium Risk’ offender in each group), all had a history of committing violent and/or sexual crimes (including their index offence), and all spent time in the community within the period studied. Although pre-formulation differences between the groups cannot be completely ruled out, the above factors and the clear differences identified between the recommendations made in cases with ‘positive’ versus ‘negative’ outcomes suggest that the findings identified within the present study do merit further serious consideration and exploration. To build upon these results, research should aim to further validate each step of the logic model. This could be achieved with a larger real-world prospective study where subjects are monitored closely (perhaps with the assistance of their OMs) over time to observe whether the relevance, feasibility and utility of formulation recommendations do have a significant impact on the development of outcomes, after controlling for personality, interpersonal functioning, emotional regulation, and risk-related characteristics.

A final point to note is that although a great volume of retrospective data was directly accessible from NPS databases, and data was triangulated wherever possible, it is still the case that this data was not directly observed or recorded for the purposes of the present study (due in part to restrictions relating to COVID-19) and was written from others’ perspectives. This may have introduced some level of error into the analyses, such as that resulting from missing or biased data. The use of a two-tailed case-study is likely to have mitigated the impact of this limitation somewhat, as clear differences between cases with positive versus negative cases were observed. In addition, as entries uploaded onto these NPS databases constitute the formal record of events in each case, it is likely the case that these systems do capture the most pertinent and relevant case information. However, this is a limitation that should be considered in future if the study were to be replicated or expanded, and perhaps could be mitigated with the collection of primary data directly from the source (i.e. conducting interviews or surveys with the offender manager of each case) when the case is ‘live’. If this were not feasible (i.e. in larger study designs), an alternative could be to explore ways of introducing additional structure to narrative NPS records (i.e. offender manager descriptions of events) at the point of entry. For instance, a framework could be introduced to aid offender managers in structuring their descriptions of meetings held with offenders, and/or their efforts to complete formulation recommendations. This would better ensure that these types of events can be captured and analysed in a more objective and consistent manner.

Additionally, future research could utilise primary research methods to gain staff input on the logic model developed here and to better understand (for instance) why avoidable barriers were often not overcome in cases with negative outcomes. This could involve interviewing OMs to further explore the types of barriers they typically face when attempting to utilise formulation recommendations, and what support might be useful in assisting them to overcome these barriers. In addition, it would be useful to explore the time point at which formulation is completed for each offender, and whether formulating earlier in an offender’s sentence could be useful. Finally, future research should explore how the possible impact of formulation recommendation fits into the wider contribution of the OPDP on offender outcomes.

In conclusion, this two-tailed multiple-case-study has illuminated the capacity of formulation recommendations to provide value within the OPDP. Further validation with (possibly experimental) research, would enable this model to be drawn on by OPDP staff (and others engaged in forensic case formulation) to identify common pitfalls more easily, ensuring that maximum value can be extracted from these formulation recommendations.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their sensitive nature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Replaced in 2017 by Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS).

2 Cases were not selected based on gender; around 95% of the OPDP caseload is male.

3 The RoSH is a structured professional judgement assessment resulting in each offender being placed in one of four risk categories: ‘Low’, ‘Medium’, ‘High’ or ‘Very High’ (HMPPS, 2019).

4 As this third offender was still in custody for the first two months of the one-year period following formulation, this reduced the period in which it was possible for him to be recalled within this year. Due to this, all records pertaining to this offender were examined for an additional two-month period. It was confirmed that within these two additional months, this offender was not recalled to prison and was not recorded as breaching any licence conditions.

5 Examining level 3 formulations was initially considered, but these were found to be very few in number, completed only within highly specialised OPDP environments, and not easily accessible.

References

- Barrett, B., & Tyrer, P. (2012). The cost-effectiveness of the dangerous and severe personality disorder programme. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1829

- Beaumont Coleson Software & System Solutions. (n.d). nDelius. Retrieved 2nd November 2020 from http://www.beaumont-colson.co.uk-nDelius_Factsheet.pdf

- Burns, J. M. C. (2010). Cross-case synthesis and analysis. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case study research (Vol. 1, pp. 264-266). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397

- Division of Clinical Psychology. (2011). Good practice guidelines on the use of psychological formulation. British Psychological Society.

- Eells, T. D. (2007). Psychotherapy case formulation: History and current status. In T. D. Eeels (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy case formulation (2nd ed (pp. 3–32). Guildford Press.

- Joseph, N., & Benefield, N. (2012). A joint offender personality disorder pathway strategy: An outline summary. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1835

- Knauer, V., Walker, J., & Roberts, A. (2017). Offender personality disorder pathway: the impact of case consultation and formulation with probation staff. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 28(6), 825–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2017.1331370

- Logan, C. (2017). Formulation for forensic practitioners. In R. Roesch & A. N. Cook (Eds.), Handbook of forensic mental health services (pp. 153-178). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315627823-6

- McDonald, N., Schoenebeck, S., & Forte, A. (2019). Reliability and Inter-rater Reliability in Qualitative Research. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359174

- Morgan-Trimmer, S., Smith, J., Warmoth, K., & Abraham, C. (2018). Introduction to logic models. Retrieved 12th December 2020 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-in-health-and-well-being-overview/introduction-to-logic-models

- National Offender Management Service, & NHS England. (2015a). The Offender Personality Disorder Pathway strategy. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2016/02/opd-strategy-nov-15.pdf

- National Offender Management Service, & NHS England. (2015b). Working with offenders with personality disorder: A practitioners guide. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/10/work-offndrs-persnlty-disorder-oct15.pdf

- Sturge, G., & Beard, J. (2019). Sentences of Imprisonment for Public Protection. Retrieved May 9 from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06086/#:~:text=What%20are%20IPPs%3F,presented%20a%20risk%20to%20society

- Wheable, V., & Davies, J. (2020). Examining the Evidence Base for Forensic Case Formulation: An Integrative Review of Recent Research. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 19(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2019.1707331

- W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action: Logic model development guide. W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications (6th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.