ABSTRACT

This research examines how suspects attempt to influence interviewers during investigative interviews. Twenty-nine interview transcripts with suspects accused of controlling or coercive behavior within intimate relationships were submitted to a thematic analysis to build a taxonomy of influence behavior. The analysis classified 18 unique suspect behaviors: the most common behaviors were using logical arguments (17% of all observed behaviors), denial or denigration of the victim (12%), denial or minimization of injury (8%), complete denials (7%), and supplication (6%). Suspects’ influence behaviors were mapped along two dimensions: power, ranging from low (behaviors used to alleviate investigative pressure) to high (behaviors used to assert authority), and interpersonal alignment, ranging from instrumental (behaviors that relate directly to evidence) to relational (behaviors used to bias interviewer perceptions of people and evidence). Proximity analysis was used to examine co-occurrence of influence behaviors. This analysis highlighted combinations of influence behaviors that illustrate how different behaviors map onto different motives, for example shifting attributions from internal to external to the suspect, or to use admissions strategically alongside denials to mitigate more serious aspects of an allegation. Our findings draw together current theory to provide a framework for understanding suspect influence behaviors in interviews.

There has been much interest in the role of influence in investigative interviews to encourage cooperation. Studies have examined the relationship between interviewer behavior and suspect cooperation (Bull & Soukara, Citation2010; Kelly et al., Citation2016) and the role of moderating factors such as culture (Beune et al., Citation2009; Beune et al., Citation2010). Fewer studies have focused on the behaviors of suspects, despite the fact they also seek to influence the beliefs and behavior of their interviewer. In the current research, we develop a taxonomy of suspect influence behaviors and examine how these behaviors are brought together by suspects to achieve their goals. We define influence behaviors as any behavior which has the apparent goal of changing the beliefs and/or behaviors of the interviewer(s) in favor of the suspect, whether such behaviors are deployed strategically or not, and irrespective of if they are ‘successful’ or not. Our goal was to test a theoretically derived taxonomy of influence behaviors against the actual behavior of suspects. We identified potential influence behaviors through a review of the existing literature in three areas: suspect behavior in interviews, intimate partner violence perpetrators’ manipulative behavior outside of the interview setting, and the wider literature on persuasion and influence. We also allow for the inductive identification of influence behaviors within our data. We did this by using a corpus of interviews with suspects accused of controlling or coercive behavior in their intimate relationships. Unlawful in the UK since 2015, controlling or coercive behavior is a pattern of behavior that includes isolating individuals from other sources of support, controlling their finances, humiliating them, or regulating their everyday behavior (Serious Crime Act, Citation2015).

Control or coercion is an appropriate crime for the development of a suspect taxonomy for three reasons. First, it is a difficult crime to prosecute because there is often no physical evidence; where there is physical evidence (e.g. cases accompanied by physical or sexual assault), investigators often focus on prosecuting for that crime (Barlow et al., Citation2019). The lack of physical evidence makes the interview critical, since it is often the only opportunity to obtain evidence to secure a conviction. Second, manipulation of others is inherent in the definition of the crime (Serious Crime Act, Citation2015), meaning perpetrators are likely practiced at deliberately influencing others beliefs through their behaviors. Third, investigators have limited experience in trying to prosecute this newly established crime, and some evidence suggests they are failing to identify patterns of abuse indicative of control or coercion within their investigations (Barlow et al., Citation2019).

Suspect behaviors during investigative interviews

Suspects who are guilty typically seek to present plausible explanation for events that avoid incriminating details and minimize the likelihood or severity of any resulting punishment (Masip & Herrero, Citation2013; Strömwall & Willén, Citation2011). However, we know from wider research on offender motivation that they are often not only interested in weighing the personal costs and benefits of action, but also adhere to normative beliefs (Bottoms, Citation2001) and project a positive self-image despite engaging in behavior that may violate normative beliefs (Sykes & Matza, Citation1957). These actions are no different in the investigative interview where suspects have been shown to, for example, prioritize maintenance of a cultural norm (Giebels et al., Citation2017) or protection of a particular community (Taylor et al., Citation2017). There is, however, only limited research addressing how these diverse goals are enacted within investigative interviews by suspects.

Early evidence of how suspects seek to shape an interview comes from conversation and discourse analysis of transcripts. Auburn et al. (Citation1995) identified that offenders try to change police officer attributions of a crime from being a consequence of the inherent nature of the suspect, to a consequence of circumstance and victim behavior. Similarly, analyses of interviews with serial killer Harold Shipman revealed the ways in which he would seek to establish control over his interviewer while maintaining a façade of cooperation through, amongst other behaviors, asserting his superior medical expertise, avoiding confirmatory responses by voicing agreement from the perspective of the interviewer rather than himself (e.g. ‘If you say so’), and interrupting the interviewer’s intended interview plan with changes of topic (Haworth, Citation2006; Newbury & Johnson, Citation2006). These analyses highlight the high priority Shipman placed on identity needs, his desire to self-present in a way he considers desirable, through his refusal to either be overtly confrontational or to allow himself to be held in a subordinate position to his interviewer.

While conversation analytic work has provided detailed analyses of specific suspect behaviors and their consequences, a limited number of studies have tried to characterize a wider range of behaviors that may generalize across different suspects. Legal psychological examinations of interviews have generally focused on interviewer behavior, and characterized suspect responses insofar as they reflect a response to the interviewers questioning style (e.g. Leahy-Harland & Bull, Citation2017). This work has been incredibly valuable in improving the practice of investigative interviews and understanding how interviewer behavior impacts upon the cooperation of the suspect. However, this work does not directly address how the suspects themselves seek to influence the interviewer. Work that addresses this question is more limited.

Pearse and Gudjonsson (Citation2002) examined transcripts of interviews from 20 serious crimes where suspects moved from denial to confession. While their analysis emphasized police behaviors that led to this change, they also identified six categories of suspect responses: positive responses (agreements, admissions and giving accounts of their actions); negative responses (denials, disputing accounts, challenging inferences made by police, withdrawals of confessions, claiming no memory of events, staying silent); information or knowledge (seeking information from the officer, e.g. asking about early release, asking for a repeat of the question); rationalization (attempts to minimize the offence or responsibility for it or giving a motive.); projections (passing blame to someone else or the victim); and emotional responses (showing distress, crying, say they are tired or low, self-blame and remorse, confusion, anger or shouting). The aims of Pearse and Gudjonsson (Citation2002) study are analogous to ours and so informs our own analysis. However, there are two key differences between their study and our own. The first is that we have an explicit focus upon suspect rather than interviewer behaviors. The second is that we, in addition to identifying and classifying behaviors, analyze both the context in which different behaviors are used and how these behaviors co-occur to help provide insight into the possible function of these behaviors.

Additional work examining suspect behaviors was performed by Alison et al. (Citation2014). Alison et al. (Citation2014) analyzed 181 interviews with 49 suspects convicted of terrorism charges and focused specifically on counter interrogation strategies. Of the 31 identified strategies, only 9 were used by more than 10% of suspects, and these grouped into 5 categories: verbal strategies (e.g. discussing an unrelated topic in response to questions, providing only well-known information); passive-verbal strategies (e.g. responding with monosyllabic responses, claiming no memory of events); passive strategies (e.g. refusing to look at the interviewer, total silence); retracting information; and no comment. Importantly, the bulk of the identified strategies appeared to focus on withholding information, or else distracting interviewers, which may be a function of counter interrogation strategies that focus on resisting cooperation. The results do not necessary address possible suspect influence behaviors more widely, for example, those intended to maintain social norms or influence interviewer attributions rather than only prevent the provision of information. By taking a broader consideration of suspect aims and behaviors, we thereby address a significant gap in the current literature on suspect behaviors during investigative interviews.

Development of a theoretically informed taxonomy of suspect behaviors

Alison et al. (Citation2014) and Pearse and Gudjonsson (Citation2002) represent some of the scant research with the aim of classifying suspect behaviors within interviews. Consequently, we build upon their work to establish the starting framework for our own analysis. For example, we directly adopt the behaviors of shifting topics, claiming no memory of events, and responding with silence or no comment. However, unlike Alison et al. (Citation2014) and Pearse and Gudjonsson (Citation2002) we will classify these behaviors according to a qualitative and quantitative analysis of how these behaviors are enacted rather than only a quantitative appraisal. This comprehensive approach allows us to inform our classifications though inductive inference and semantic analysis which we believe will provide greater insight into how behaviors are used within interviews.

We inform our semantic analysis by considering the different motivations that suspects are likely to wish to express; that is, their instrumental, identity, and relational needs (Taylor, Citation2002). Instrumental motivations are focused on obtaining tangible rewards. Relational motivations refer to attempts to manage the relationship between parties. Identity motivations are concerned with managing one’s self-presentation. Suspects are likely often concerned with instrumental goals, especially convincing the interviewer that they are innocent by presenting a set of corroborating ‘facts.’ However, suspects also have identity and relational goals that may serve as end points in and of themselves (Giebels et al., Citation2017; Taylor et al., Citation2017). They may want the interviewer to perceive them as benevolent, or seek to intimidate the interviewer and control the interaction. Therefore, we will consider the extent to which suspect behaviors address each of these different motivations.

Given the scarcity of literature directly addressing suspect behaviors within interviews, we also inform the development of our taxonomy from research conducted within other contexts. One key area is the wider research on persuasion. Giebels (Citation2002) and Giebels and Taylor (Citation2010) drew on persuasion research by Cialdini (see Cialdini, Citation2008 for a full overview) in a law enforcement context to identify the ways in which crisis negotiators attempt to change the beliefs and behaviors of their negotiation partners. Giebels and Taylor developed the Table of Ten influence behaviors: being kind, being equal, being credible, emotional appeal, intimidation, imposing restrictions, direct pressure, legitimizing, exchanging, and rational persuasion. Given the shared aims of suspects and crisis negotiators, to change the attitude and behavior of their interaction partner in a high-stakes legal context, we incorporate these ideas into our initial taxonomic framework.

The group of suspects we analyze are all accused of controlling or coercive behavior within intimate relationships. Consequently we expect to find influence behaviors known to be used by perpetrators of intimate partner violence to excuse or otherwise justify their behavior. One example is that behaviors representing emotional appeals are of specific interest within domestic violence. One behavior of abusers is to excuse their abuse with pity seeking ‘remedial behavior’ (Cavanagh et al., Citation2001). The function of these behaviors is analogous to supplication (Bolino & Turnley, Citation1999). Supplication behaviors communicate dependency and a need for support within a relationship (Clark et al., Citation1996), in a way analogous to how Cavanagh et al. (Citation2001) argued remedial behavior is used to excuse abusive relationship behavior. Thus, it was highly plausible suspects would use similar behaviors – apparent contrition and supplicative behavior – for similar reasons within control and coercion interviews.

An important theoretical consideration in developing the behavior taxonomy was ways in which suspects would try to justify their behavior to themselves, because it is likely they would justify their behaviors to others in a similar way. Here we are informed by Techniques of Neutralization (Sykes & Matza, Citation1957). Techniques of Neutralization refer to the ways in which offenders rationalize their behavior that violates community norms which offenders would otherwise subscribe to. They include: Denial of Responsibility – claiming negative behaviors are a response to external pressures; Denial of Injury – claiming that no or little harm was caused by their actions; Denial of the Victim – claiming that negative actions were rightful due to the negative behaviors of the victim; Condemnation of the Condemners – shifting focus from the negative behaviors of the offender to the questionable motives of those that disapprove of the offenders conduct, and; Appeal to Higher Loyalties – the offenders behavior was in accordance of the norms of a social group they consider superordinate to the group that considers their behavior unacceptable.

Finally, we consider that for suspects arguments to be convincing, it is important for the offender to establish themselves as a trustworthy source of information. Therefore, we consider the ways in which suspects might seek to present themselves as worthy of such trust. Mayer et al. (Citation1995) usefully identify three constituent parts of trust: Ability – the extent one can show oneself to be capable of performing within a specific context; Benevolence – the extent to which one intends to do good for the trustor without an egocentric motive, and; Integrity – the extent one adheres to a set of principles acceptable to the trustor. Each of these elements can be adapted to the interview situation. Ability can straightforwardly be considered the extent to which the suspect shows themselves capable of providing accurate testimony. Benevolence toward the interviewer is perhaps of less immediate concern, but the suspect may wish to show themselves to be someone who generally holds good intentions towards others in general, and the alleged victim in particular. Similarly, suspects are likely to wish to demonstrate that they are someone that adheres to high moral standards in general, and honesty in particular.

The current study

Pearse and Gudjonsson (Citation2002) and Alison et al. (Citation2014) identified some of the ways that suspects try to avoid implicating themselves, and we highlighted some aspects of literature not yet applied to the behavior of suspects within investigative interviews that may nonetheless inform our approach. In this study we built on these efforts and developed a taxonomy of suspect influence behavior. We did this by seeking behaviors that aligned with the prior literature we have reviewed within our corpus, while also allowing for the inductive identification of new influence behaviors. We further sought to analyze when such influence behaviors were used in interviews in order to allow us to propose possible mechanisms by which behaviors may influence interviewers. Inferring (plausible) mechanisms of action could in the future help to develop strategies to resist influence attempts. We examine behavior usage via two methods. First, we conduct a qualitative thematic analysis which will both classify specific behaviors as well as examine the context in which behaviors are commonly deployed. Second, we conduct a proximity analysis (Taylor, Citation2006) that identifies behavioral co-occurrence. The underlying assumption being that arguments that tend to co-occur are likely to have similar underlying motives.

Method

Data

Data were transcripts of 29 interviews with 25 different suspects accused of controlling or coercive behavior in an intimate relationship, provided by a UK police force. Coercive behavior is ‘an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim’, while controlling behavior is ‘a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behavior’ (Crown Prosecution Service, Citation2017). This meant that our population was a group that could be anticipated to engage in manipulative behaviors, and that these manipulative behaviors could likely be informed by existing knowledge about the behavior of people with a history of intimate partner violence because it is common for control and coercion to coexist with other forms of intimate partner violence (Walby & Towers, Citation2018).

The interviews were selected using heterogeneous purposive sampling so as to capture variation in behaviors depending on case details and interview length. Specifically, cases were chosen because they were arrested and investigated for controlling or coercive behavior and had a duration of over 25 minutes to avoid no comment interviews. (One interview is shorter than 25 minutes, but this was a follow up interview with a suspect about the same case and so we did not exclude this because we have almost an hour and a half of total interview time with this suspect). Our qualitative analysis focused on identifying specific behaviors and inferring their (possible) mechanisms of action based on the immediate context of the moment of the interview in which they took place. Consequently, we did not adjust our coding process where suspects were interviewed on two occasions in order to account for their earlier behavior in a prior interview as the context in which the interview was conducted may have changed. The audio-recorded interviewers were transcribed verbatim (with identifying information such as names and addresses removed) by a Security Cleared transcriber. The sample included suspects aged between 19 and 51 (mean age was 34). Most of the sample were males accused of offending against females. However, the sample included one woman, and one (male) same sex offender to capture variation across a diversity of suspect characteristics (Ritchie et al., Citation2013). Nine suspects were subsequently convicted of controlling or coercive behavior. Of the other 16 cases, six suspects were convicted of a different crime (e.g. harassment, assault), five were found not guilty or had charges dismissed, and five suspects were not taken to trial. Combined, the interviews comprise 2,338 minutes of dialogue (M = 80.6 minutes, SD = 35.3, Range: 18–151 minutes) and 13,606 suspect utterances. Utterances are defined as a block of suspect speech which can be attributed to (at least) one code, or a block of speech which presents no clear attempt to influence and so which can be coded as being neutral. Utterances therefore represent units of meaning, and could comprise a single word or several sentences, and contain only a single or multiple overlapping codes (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). However, all utterances took place within a single turn in the conversation, and every suspect turn in the conversation was coded with at least one code. Where no influence behavior was present within a conversational turn the entire response was coded as being neutral.

Procedure

We used a positivist thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation1998) to identify instances of specific attempts by the suspect to influence the interviewer. That is, we aimed to develop a taxonomy of influence behaviors which is sufficiently objective to be applied to interviews not contained within our initial corpus and to be applied by researchers beyond the current research team. However, rather than develop a thematic framework, we seek to classify and provide a rich description of behavioral types.

While our approach is broadly positivist, it was important to allow space for an inductive approach to coding informed by the voice and experiences of the suspects within the interview. To reconcile the need to allow for inductive identification of codes within our taxonomy we adopted a hybrid approach to coding. Primarily we developed our initial behavioral taxonomy through a top-down theoretical approach to thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) whereby our initial framework was based upon our literature review which, given the relative scarcity of research examining influence behaviors, also considered literature from other scenarios where there is an aim to persuade another party, such as research on crisis negotiation (Giebels & Taylor, Citation2010), trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995), and impression management (Bolino & Turnley, Citation1999). We describe the identified behaviors and their relation to their theoretical origin when presenting the results of the study. That is, while we describe our initial ideas as to how behaviors are likely enacted within the interviews within our Introduction, we describe how these behaviors are enacted concretely within our sample in the Results. Where suspects engaged in behaviors that could plausibly influence the interviewer but the behavior could not be mapped to any existing theoretically derived code we intended to develop new codes inductively, however it transpired that all identified behaviors were versions of our theoretically derived codes.

These theoretically-derived codes were then developed iteratively by examining dialogue in the suspect-interviewer interactions. Behavioral codes were modified, merged with different behaviors, or removed where they were not represented in the data. Where codes were modified based upon the data, already analyzed interviews were re-analyzed according to the latest coding framework (Rabiee, Citation2004). This process was repeated until all utterances within the interviews were coded and no changes were required to the coding framework. It was possible for utterances to be represented by multiple codes. Codes were considered either present or absent for each utterance. contains the final coding manual alongside references for the theoretical origin of each code. Appendix 1 details the codes that were initially included in the coding manual but were removed from the final framework due to a lack of supporting evidence.

Table 1. Catalogue of identified influence behaviors.

Finally, we examined the coded data at the semantic level to understand the context in which different behaviors were used (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We drew inferences about when suspects employed different influence behaviors based primarily on what it is the suspects said. We were interested in identifying what suspects did and under what conditions they engaged in different behaviors. We did not try to map directly from interviewer to suspect behavior, but rather consider the wider context of the interview in which the behaviors occurred (e.g. whether the interviewer was following a persistent line of questioning, or was challenging the suspects account). We took this approach because we believe suspect behaviors are likely impacted by events beyond the most immediate interviewer behaviors, and we wanted our analysis to be able to capture this. Similarly, we did not try to code interviewer responses to suspect behaviors because it proved impossible to determine whether an interviewer’s response reflected their training or the success of an influence behavior. For example, if an interviewer changed the topic in response to an aggressive response from the suspect, we could not determine whether this reflected the success of an influence behavior or a deliberate strategy on the part of the interviewer to maintain cooperation from the suspect. We also did not attempt to differentiate behaviors that presented truthful and dishonest information, since it was not possible to determine veracity in this context. It should be noted that we did not have ground truth regarding the allegations against the suspect. While we did have information regarding whether suspects were found innocent or guilty, conviction rates were extremely low for control or coercion during the period this study was conducted. Further, there was a tendency to seek prosecution for different crimes which may have been easier to evidence (Barlow et al., Citation2019). Consequently, relying on conviction to infer the truth of a suspects account is likely to be very inaccurate. Rather, we coded behaviors that advocated for the suspect without judgement of whether the argument was honest or deceptive. Moreover, we did not seek to analyze the underlying structure of the conversation or the effects different behaviors had upon the interviewer or conversational dynamic as might be the case with a latent approach to thematic analysis or a conversation or discourse analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Interrater reliability

All transcripts were coded by the first author. To determine how well the identified codes could be independently applied to the data, the second author and fourth author second coded all suspect interviews using the final coding framework. Behaviors that were observed on less than 30 occasions across all 25 suspects were removed from the analysis because reliability of the code would likely be imprecise. The behaviors that were removed from the final analysis are included in the list of removed behavioral codes in Appendix 1. We compare interrater reliability using two metrics. First, we use Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, Citation1960) as the most common measure of interrater agreement. However, Kappa often underestimates agreement when the prevalence of rated behaviors is low (Wongpakaran et al., Citation2013). Since some of the behaviors we identify occurred infrequently, we also calculate interrater agreement via Gwet’s AC1, which is more robust to bias than Kappa with low prevalence codes (Gwet, Citation2008). Both metrics showed good interrater reliability across our taxonomy. The mean agreement across all behaviors, estimated using Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, Citation1960), was substantial (κ = .76, range: κ = .62-.90); (Landis & Koch, Citation1977) and Gwet’s AC1 indicated even stronger performance across measures (AC1 = .99, range: AC1 = .94 −1.). also presents agreement rates for all individual behaviors.

Assessing behavior cooccurrence

To examine the extent to which suspects use tactics concurrently we used proximity analysis (Giebels & Taylor, Citation2009). This analysis allowed us to identify behavioral constellations which could give us greater insight into how different behaviors may be used in conjunction, allowing us more confidence in inferring the potential function of individual behaviors. Proximity analysis involved two steps. First, we examined the interrelationships among suspects’ behaviors by calculating proximity coefficients (Taylor, Citation2006) from the sequence of coded behaviors for each interview. Multiple interviews with the same suspect were treated as a single interview to calculate proximity coefficients. This step produced a matrix of coefficients for each interaction that represents the average proximity of every influence behavior to every other influence behavior, within the overall sequence of behaviors for the interview. Second, we averaged these matrices across the interviews and represented the average coefficients visually using Smallest Space Analysis (SSA; see Salfati & Taylor, Citation2006). SSA represents each influence behavior as a labelled points in a spatial plot. SSA then arranges these points such that the distances among the points represents the rank order of average proximity coefficient. The closer two points appear in the space, the greater their average proximity/co-occurrence within the interviews. Thus, strategies that co-occur during interviews are located close together on the SSA plot. Those that appear far apart seldom co-occurred in the interviews. Consistent with Taylor and Donald (Citation2007), we examined this visual representation of the underlying structure of suspects’ influence behavior to support inferences about the function of different behaviors as gleaned from our qualitative analysis.

Results

Behavior frequency

Of the 13,606 suspect utterances identified across the 29 interviews, 8,857 (65.1%) could be coded with at least one of the identified influence behaviors (i.e. after removal of utterances that did not fit the criteria for any codes, for example, the direct provision of relevant information absent any additional qualification, or markers of attention such as continuers). The median (IQR) total number of instances of influencing behavior per suspect was 785 (484, 943.5). The extent to which suspects made utterances that did not meet the criteria for any influence behavior also varied between participants. The median (IQR) percentage of suspects’ speech that was free of any identified influence behavior was 22.5% (17.7%, 31.5%).

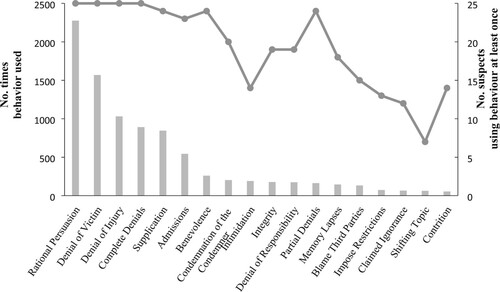

presents the frequency of behavior usage alongside the number of suspects that employed the behavior at least once. lists the number of total occurrences for each influencing behavior, along with the number of suspects that used the behavior at least once. Suspects used between 7–18 discrete behaviors (Mdn = 14, IQR 12–16) throughout the interview. However, use of discrete behaviors tended to be characterized by positive skew. As can be seen from the medians and quartiles presented in , suspects tended to heavily employ a few behaviors but rarely used others.

Figure 1. The frequency of all coded influence behaviors used by coercive control suspects across all interviews.

Table 2. Occurrences of influence behaviors across all 25 suspects.

Use of behavioral types

Contextual analysis

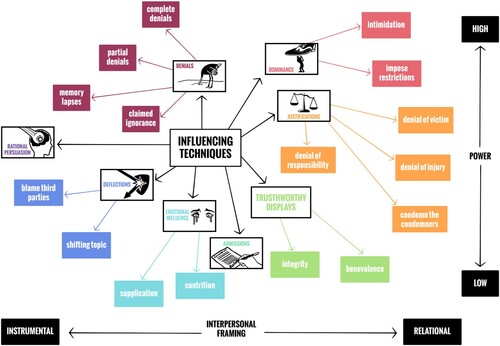

illustrates our semantic analysis of the context that underpinned when different influence behaviors occurred. This semantic analysis allowed us to place our classifications of different influence behaviors on a conceptual map that varies across two dimensions: Power and Interpersonal Framing. Power refers to influence behaviors that vary in apparent desired outcome from alleviating investigative pressure to imposing control over the interviewer and/or asserting authority during the interview. Interpersonal Framing refers to influence behaviors that vary in their emphasis from arguing an instrumental frame (suspects seek to make direct and tangible arguments about evidence), to a relational frame (suspects seek to alter the attributions made by the interviewer about them). We discuss each in turn with examples below.

Figure 2. Illustrative map of influence behaviors alongside dimensions of power and interpersonal framing.

Power

High power behaviors

Investigative interviews have an inherent power asymmetry (Abbe & Brandon, Citation2013). The suspect is in a stressful and ambiguous situation with the potential to face significant personal consequences, while the officer has control over the interview setting and can make vital decisions about the suspect’s future liberty (Haworth, Citation2006). However, the perceived difference in power is likely to vary across suspects. For example, there are significant individual differences in risk perception and in experience of police interviews. If past interviews had positive outcomes for the suspect, it is likely to affect the level of risk he or she perceives (Barnett & Breakwell, Citation2001). Those that perceive lower risk from their interviewers are less likely to feel intimidated and may try to take proactive measures to take control of the interview’s direction and content (Acedo & Florin, Citation2007).

The interviewer-suspect power balance is not fixed at the start of the interview, but rather something that is renegotiated constantly (Haworth, Citation2006). In our sample, suspects sometimes engaged in intimidating behaviors despite holding the supposedly subordinate role. For example, they belittled the line of questioning or directly asserted that they were unintimidated by the police. One suspect opened the interview by ridiculing the notion of his accusation for control or coercion, ‘I kept asking last night what, what I'd been arrested for because I wasn't quite sure, and it sounds a bit stupid, to be honest.’ The same suspect again used intimidation behaviors by going on to argue that the police had no role in private relationships:

‘So now you're not just the police (inaudible), now you're, like, relationship police … Who are you to judge, right, how my relationship is with my missus and that, yeah? And I, I don't jump on anyone else’s life and go, ‘You can't argue with your missus.’’

A related strategy was to impose restrictions by threatening to shut down communication. Suspects appeared to use their rights to silence and/or legal representation as threats to warn police about pushing too far. In the following extract, the suspect used his right to non-response to disrupt challenges about his account and to clearly articulate topics that he was or was not willing to provide substantive answers to (Stokoe et al., Citation2016). The police officer acknowledges his right to do so, and the suspect then feels able to continue talking while steering the conversation toward a favorable narrative:

Listen to me a second, please. We’re not …

I don't need to do nothing.

Well, no, you don't. We're asking …

Right, well, from now on I'm going to go, ‘No comment,’ from this point.

Okay, that's fine. So if I ask these questions you're going to go, ‘No comment.’

Just ask the questions and we'll see.

Okay, that's fine then. All right.

It does my head in, yeah, she's a young girl with a drug addiction and because she's screamed (inaudible), you've got straight to her. Go and have a look on her, on her records (inaudible) ex-boyfriend, she's done this time and time and time and time again (inaudible).

‘ … but he’ll either ignore me or say, ‘When I’m back, you better not be here.’’

I’ve, I’ve said to her, ‘When I’m back, you better not be here’?

Mmm.

That is a fucking lie.

Okay. So you never said that to her?

That is a lie, that is a lie.

And she says that she never wanted to push you because she said that you …

So I’ve, so I’ve said to her, ‘When I come back, you best not be in your house’? That is a, that is a bullshit story, mate.

Low power behaviors

At the other end of the Power spectrum were influence behaviors that could alleviate pressure on the suspect. When suspects were unable to explain their behavior, or were unable or unwilling to take a proactive high power approach, they often reframed the interviewer’s perception of their behavior. One reframing behavior was contrition. In the following exchange, the suspect interjects the line of questioning to make an apology and to garner sympathy:

Okay. So, you’d be asking her questions about other boys. If she said the wrong thing or you didn’t like one of the answers, you’d become abusive towards her, telling her she was a whore, slut and she was gonna die, yeah?

Yeah.

And if she said an answer that didn’t line up with something you’d said before or you thought she was lying, or you just didn’t believe her, then you would make her cut herself and send you, send you photos to prove you’d been cutting yourself, to send her photos that she’d been cutting herself as punishment. Did you ask … Did you ever ask COMPLAINANT to cut herself?

Yes.

Okay. Tell me about that.

I … (pause) Just before I do, I would like to say, erm, I … Okay?

Mmm-hmm.

Er, I have never, I have never felt so bad in all of my life, looking back and remembering everything I’ve done to that girl, to the point where if, like, it, it makes me want to hurt myself more, knowing that I ruined someone who’s very good. Erm, I told her so much that what I did was my, her fault, and what I heard in the voices and people I see were her fault, and it’s only now that I wish I could tell her that it’s okay and just hug her and just let her know that it wasn’t, because I thought I had it bad when I didn’t realise she was just hiding how bad she was feeling. I just can’t … I just really, I just really struggle to see the good in me anymore.

But … And … But I was … I, I did feel bad because yes, it was my fault and I ice pack her back, heat massages, I … Cos, at end of the day, I still take responsibility because, if I didn’t be silly …

I mean, she’s obviously saying that these assaults have happened. Er, she goes on to say that you were very apologetic and …

Yeah because it wasn’t intentional, madam.

Okay.

It was me being silly.

Er, well, you've not been charged with anything yet. The likelihood is that you probably won't be able to go back for some … For a couple of weeks at least. Erm, but then that’s, that’s, that’s a decision that’s not been made yet anyway. So we can't really cross that bridge yet. But what I'm, I'm wondering is, once you're released from here, what are the repercussions that if you find …

I don't think there is any, no. I've got no more fire left in me.

Right.

I've got nothing.

And what do you mean by that? Is that the end?

Just can't, I can't hold it together anymore.

Hold the relationship or life?

The relationship. I've got nothing.

Right. Do you feel quite low at the minute?

Yeah.

Yeah. Do you want a minute?

I'm all right.

Are you sure?

Interpersonal framing

Instrumental behaviors

Instrumental behaviors are those that relate directly to evidence. We applied the label ‘instrumental’ because these behaviors deal with tangible themes (i.e. evidence), and most often deal with tangible desires (i.e. to be seen as innocent; (Taylor, Citation2002)). Approximately one in four coded behaviors could be categorized as displaying characteristics of rational persuasion. Rational persuasion refers to attempts to use persuasive arguments and logic (Giebels & Taylor, Citation2010), and within our framework, to explain evidence against the suspect. For example, in the following excerpt, a suspect was accused of criminal damage whereby he destroyed his wife’s hijab during an argument. Here the suspect argues that he cannot be guilty of criminal damage because he bought the hijab as a gift for his wife, which she refused, and he therefore claimed the hijab is his property that he has the right to destroy.

… And I give her her present. Er, I … ‘It’s too big for me,’ for the hijab. It’s a blue hijab, yeah? That’s the present for her, I bought her the hijab and another something, you know, and the hijab, she says, ‘Oh, what’s that? It’s an M. It’s too big for me. I’m not a size … ’ I said, ‘What do you mean? What, you want me to get you a size 6?’ whatever, you know. ‘I told you what size, it’s 12.’ She says, ‘It’s too big for me, I don’t want it.’ I said, ‘Okay, then, I’ll,’ you know, ‘I’ll keep it, I’ll keep it,’ whatever. You know what I mean?

Yeah.

It’s mine, you know?

Okay.

I keep it. It’s mine. Wasn’t, like, for her. Once I bought it, if she likes it, she wear it. If she don’t like it, I keep it.

Okay.

You know what I mean? That’s why I got it, cos I was upset, when I got it, she wasn’t at home … I’m talking when I was packing my things. I went upstairs.

Yeah.

And I, I found it and I cut it.

Haworth (Citation2006) considered topic changing as a display of power within an interview because it challenges the interviewers’ control over what and when issues are discussed. While we do not disagree, changing topic is less direct a challenge to the interviewer’s authority than that posed by intimidation behaviors. It was not always clear that there was an explicit motive to challenge the interviewer, so much as to move on from topics where the suspect could not offer rational persuasion arguments. Changing the topic may also take the form of answering questions in such a way that does not answer the specific question asked. Haworth (Citation2006) and Newbury and Johnson (Citation2006) argued that the serial killer Harold Shipman used similar tactics to assert dominance over interviewers by providing a false veneer of cooperation to his resistance tactics. We observe that the extent to which this seems to be the case varies. Some suspects did provide evasive answers as part of a wider strategy of shifting focus onto negative behaviors of their alleged victims. Others seemed to simply change the topic as soon as possible and it was difficult to infer any deliberate agency or strategic intent beyond an aversion to answering the posed questions. While these behaviors may vary in the extent to which they reflect high or low power strategies, they are instrumental because they are a strategy for dealing with presented evidence, albeit deflecting attention away from the evidence rather than accounting for it.

Relational behaviors

Relational behaviors are those likely to influence the interviewer’s perception of the suspect or the evidence. They do not seek to explain evidence, but instead seek to persuade the interviewer that the suspect’s account is believable, or that the victim and witness statements are less credible than their own. Alternatively, they may seek to soften the interviewer’s perception of the suspect by making the interviewer more sympathetic toward the suspect, less sympathetic toward the alleged victim, or else to argue that external forces are responsible for the negative behaviors of the suspect.

Justifications are a category of influence behavior which are likely expected to minimize the negative attributions made about the suspects because of their negative behavior. This category is based on ‘techniques of neutralization’ (Sykes & Matza, Citation1957), which is a theory that explains the cognitive processes by which people justify their negative actions to themselves. We found that the same behaviors were used to justify negative actions to others, and thus perhaps minimize their impact or change the perception of the interviewer toward other pertinent details or people. The function of such behaviors may be to shift the interviewer’s perceptions of the suspect from violent person to victim of circumstance (Auburn et al., Citation1995). For example, the most widely employed justification behavior was denial of the victim. This strategy was commonly used by all 25 suspects and involves making claims that the victim directly provoked negative behavior, or else that such behavior was justified because of the victim’s own behavior or character. Examples include referring to previous infidelity to justify repeated demands for the victim to answer video calls late in the night, claiming the victim lied about working with males to justify calling by their workplace, or blaming the victim’s drinking habits for provoking arguments. Denial of the victim is common in domestic abuse (Henning et al., Citation2005) and seeks to minimize the actions of the abuser (Anderson & Umberson, Citation2001). Thus, this behavior may change the perception of the alleged victim so that they seem less deserving of help, or to change the perception of the suspect so that their actions seem justifiable and/or reasonable given the circumstances.

A second justification used by all suspects was denial of injury. Here suspects minimize the negative interpretation of their behavior by proposing innocent motives, claiming harm was less severe than alleged, or that harm should be discounted because it will not happen again (e.g. the relationship has ended no further harm will be done). Condemn the condemners was a less common justification where it was claimed allegations were spurious and motivated by ulterior motives such as spite or to strengthen a claim for child custody. Finally, denial of responsibility involved actions being justified as caused by events beyond the control of the suspect, such as addiction or mental health problems. While the exact form of justification varies, their common core was to shift the attributions interviewers make about the causes of negative behavior away from the suspect and onto external factors (Auburn et al., Citation1995).

Other categories of relational behaviors are trustworthy displays and admissions. When using trustworthy displays, suspects relied on arguments based on unrelated demonstrations of benevolence, such as referencing their standing in the community or specific examples of past good behavior, or integrity, such as referring to past displays of honesty, such as guilty pleas to other crimes. Trustworthy displays do not refer to the evidence in the case, but portray the suspect in a favorable light which may make other influence behaviors appear more credible, or else accusers less credible. Trustworthy displays were sometimes accompanied by admissions of negative behavior. The function of trustworthy displays when accompanied by admissions seemed similar to justifications, in that they may shift the interviewers attributions of the cause of negative behavior away from the suspect (Auburn et al., Citation1995). While justifications do this by referring to external causes of behavior, trustworthy displays highlight the atypicality of admitted behavior. In this way they suggest that behavior is externally caused, but without posing any direct alternative cause.

Admissions refer to instances where suspects may admit to part or all of an accusation because they have no alternative, wish to confess in full, or in order to influence the direction of the interview. For example, by admitting to a minor part of an accusation, the suspect may hope to ease pressure from the interviewer. Admissions differ from integrity displays because they refer directly to the evidence presented. However, admissions likely have a similar effect to integrity displays in that they may elicit lenient treatment and liking from the interviewer, or else support other arguments for their defense due to the honesty shown in specific instances. An admission may be used in conjunction with justification or a trustworthy display, which helps to highlight the role of these latter behaviors in shifting attributions for negative behaviors from the suspect onto external factors. In other words, suspects may admit to an accusation, but then use other relational behaviors to immediately imply that the specific negative behavior should not be attributed to them or their character.

Quantitative analysis

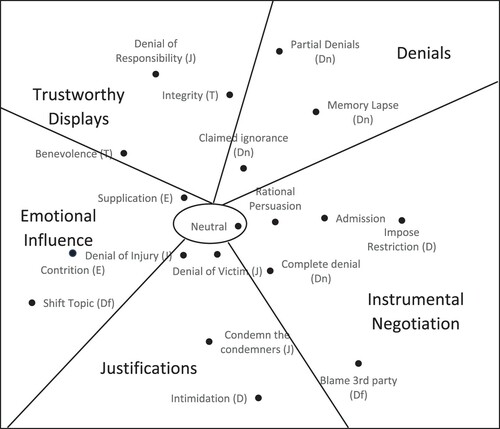

displays the SSA for the influence strategies identified in our study (it shows a two-dimensional solution; coefficient of alienation = .301; a three-dimensional solution revealed the same overall patterning of strategies; coefficient of alienation = .208). A visual examination of the SSA configuration reveals distinct regions of the solution space that correspond to the semantic analysis of the behaviors. For example, toward the top right-hand side of the SSA plot is a distinct region of strategies that deny involvement in the offence. Overall, an interpretation of the patterning of co-occurrences allows the identification of discrete regions of similar behaviors. They collectively form a ‘radex’ structure whereby each theme emanates out from a common core of neutral behaviors in a way that suggests a set of qualitative strategy types, as opposed to an ordering over time (Salfati & Taylor, Citation2006).

Rational persuasion is the behavior nearest to neutral behaviors, reiterating its common usage as a default mode of discussion. Moreover, rational persuasion co-occurs highly with admissions, which itself occurs highly with imposing restrictions. Collectively, these three behaviors suggest an instrumental negotiation of the facts between suspect and interviewer, which leads to an admission on some occasions. This reflects the investigative interview as a negotiation of an agreed narrative of events between interviewer and suspect (Alison, Citation2008; Auburn et al., Citation1995). That is, part of the objective of an interview with a suspect is to develop an evidential account of the alleged events that both the interviewer and the (at least somewhat cooperative) suspect is willing to accept. The evidential account necessarily involves the suspect making admissions, but these are unlikely to come without any accompanying argument (rational persuasion) or limits on what is open to be negotiated (imposing restrictions). Complete denials also tended to co-occur with both admissions – highlighting that the latter are often admissions of minor aspects of a crime that accompany stronger refutations of more serious allegations – and threats to impose restrictions – highlighting that complete denials could be about exerting dominance and threatening the withdrawal of cooperation. As such denials offer an additional element of instrumental negotiation over the shared narrative constructed during the interview.

Our SSA also showed that denial of responsibility was often used alongside trustworthiness displays rather than other justifications (i.e. it appears toward the top of the rather than at the bottom with the other justification behaviors). Denial of responsibility is an argument that external forces compelled negative behaviors. The co-location of these arguments with appeals about negative actions being out of character via trustworthy displays is coherent; this may also reflect denial of responsibility being a more defensive behavior. Other forms of justification (e.g. denial of injury or condemn the condemners) directly challenge the account of events presented to the suspect. Even denial of the victim seeks to reinterpret events in a way that is harmful for the victim. In contrast, denial of responsibility does not target specific others, rather it attempts to mitigate the strength of negative attributions made about the suspect by providing external explanatory factors for negative behavior.

Similarly, complete denials tended to not co-occur with other forms of denial (top right of ) but nearer justifications – especially denial of the victim and condemn the condemners which both explicitly shift blame toward other parties. The overt behavior of blaming third parties also lies near this constellation. This highlights that suspect attempts to shift attributions of blame from themselves to others are often a result of the presentation of evidence that the suspect wishes to refute. This also highlights the close association between providing an instrumental account of events within an interview directly alongside attempts to manage the relationship between interviewer and interviewee via attributional shifts. That is, instrumental and relational goals likely having different effects does not preclude that they often coexist, and this is especially so in the case of justifying behavior which necessarily must be accompanied to at least some extent with a narrative of enacted behaviors.

It is also notable that the pairing of Complete Denial and Denial of the Victim are also close in proximity to Denial of Injury and Supplication. This combination is highly reminiscent of the Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender (DARVO) strategy that has been shown to be a common response of psychological abusers when confronted by their victims (Freyd, Citation1997; Harsey et al., Citation2017). Within a DARVO response, abusers deny (Complete Denial) or minimize (Denial of Injury) their abuse, attack the victim’s credibility (Denial of the Victim) and then assume the role of victim (Supplication). Qualitatively, it was clear that suspects would dovetail repeatedly between Denial of the Victim, Denial of Injury and Supplication arguments. The combination with Complete Denials was less pronounced, which may reflect that only one initial denial is required before moving into a more protracted justification of any accusation.

Finally, the close co-location of attempts to shift the topic with contrition also support our identification of attempts to change topic as more often a low rather than high power strategy, in contrast to Haworth (Citation2006), and Newbury and Johnson (Citation2006). That is, suspects may hope that they are able to initiate a change of topic to avoid further questioning by offering attempts to appease interviewers about negative behavior using apologies.

Discussion

To date, most research on interviews has focused on what the interviewer does and what effect that has on the interview process. Here, we sought to explore suspect behaviors in the context of control or coercion interviews to help to develop an understanding of how suspects seek to influence interviewers. Our rationale for focusing on control or coercion cases was not because we view these interviews as a special case, though we do not claim that our results would necessarily generalize to other crimes. Rather, the recent establishment of control or coercion as a crime within the UK makes interviewing to gather evidence around control or coercion especially challenging for police, and so is an area where better knowledge of suspects’ behaviors would be especially valuable.

Our qualitative analysis identified 18 different behaviors suspects employed to influence the interviewer(s). Critically, several of the behaviors did not appear to about refuting evidence presented against suspects. While direct arguments against evidence and denials of evidence did occur and formed the most frequent types of suspect behavior, overall we found that attempts to influence were much more diverse and nuanced than only attempts to convince of innocence. We observed a complex pattern of behaviors that mixed such denials and arguments with behaviors to bias the perceptions the interviewer has about the suspect, alleged victim, other case relevant individuals, and the evidence presented.

Our proximity analysis helped us to understand the relationship between the influence behaviors. The map presented by the SSA broadly supported the findings of the qualitative analysis, in that suspects using specific influence behaviors that fell within a similar sector of our dimensional map of power and interpersonal framing are likely to use other behaviors from similar locations on that dimensional map. For example, justifications were usually used in combination, as were different forms of denial, emotional influence, and forms of trustworthy display. However, there were a small number of theoretically interesting deviations from this pattern. We observed denial of responsibility as co-occurring with trustworthy displays, rather than with other types of justification. Denial of responsibility involves making arguments that one’s actions that violate societal norms are the fault of external forces. Thus, it is not surprising that such arguments were co-located next to arguments about the general positive nature of one’s character (trustworthy displays). Conversely, we observed making complete denials as more closely aligned with making denial of the victim arguments than with other forms of denial. Complete denials were often accompanied by a denigration of the victim and an argument as to why they should not be trusted. Together with a clustering with denial of injury and supplication we propose that these reflect DARVO behaviors, whereby (suspected) abusers deny or minimize abusive behavior, attack the victims credibility, and assume the role of victim (Freyd, Citation1997). DARVO arguments have been shown to be common in how convicted offenders describe their crimes and when justifying their behavior when confronted by their victims (Harsey et al., Citation2017). Here we show that those accused of coercive and controlling behavior also employ similar arguments within investigative interviews when confronted by their interviewers. This might suggest that while the individual behaviors within our taxonomy are not developed to be specific to intimate partner suspects, the specific combinations of behavior used by suspects might be expected to vary depending on offence type. Finally, admissions co-occurring with rational persuasion, and near to denials, highlights that admissions are not theoretically the same as confessions. Admissions were often part of a wider narrative of arguing for innocence for more substantive accusations. That is, it is likely admissions serve a strategic purpose as a deliberate or instinctive reaction to presented evidence by which they are used to signal honesty and cooperation, but the substantive aspects of the accusation are denied or explained away in order to minimize the damage that evidence can do to the suspect’s overall argument.

Theoretical positioning of power and interpersonal dimensions

Despite individual suspects employing many different influence behaviors over the course of an interview, we found that these collapsed across just two dimensions of Power and Interpersonal framing. These dimensions are similar to a descriptor of motivational frames within negotiations. Taylor (Citation2002) identified instrumental, relational, and identity motivations. We observed these different aims reflected within our dimensions of interpersonal framing and power. Here, instrumental acts are interpreted as those that account for evidence and so can directly provide evidence for exoneration, at least in the eyes of the suspect; naturally not all arguments are truly effective. However, relational behaviors and power provide a somewhat different account of relational and identity motivations. Our power dimension dealt directly with both identity and relational issues. Both high and low power behaviors can be interpreted as attempts to ‘save face’ in line with identity aims, but within a differing relational mode. High power behaviors serve to introduce conflict or demand respect. Low power behaviors instead generally appear likely to establish affiliation, liking or trust.

Justification behaviors, such as denial of the victim, appear to have twin modes of action. First and foremost they may shift interviewer attributions of blame away from the suspect (Auburn et al., Citation1995). Second, they manage the relationship between the alleged victim or witnesses and the investigators by undermining their credibility (condemn the condemners, denial of injury, denial of the victim) or denying they are worthy of protection (denial of the victim). In this way they are clearly relational, but they also vary in the extent to which they are high or low power, and how far they reflect different identity concerns. By virtue of shifting attributions against the suspect, they are all to some extent ‘face saving’, but they do this some of the time by making the suspect appear more likeable (denial of responsibility, denial of injury) and at other times by making others seem less likeable in comparison to the suspect (condemn the condemners, denial of the victim).

Limitations

We believe we provided a rich and empirically-based analysis of suspect influence behaviors within interviews that will prove useful to researchers and practitioners. However, there are some important limitations to our analysis. Fundamentally, there are issues about the generalizability of our findings. Our sample contained only a single female suspect and a single male homosexual suspect, with all others suspected of control or coercion against a female partner. The sample is also drawn from a single constabulary in the UK with all accused of control or coercion within an intimate relationship. Consequently, it remains problematic to generalize the behaviors we observed to other crimes and populations. Because the behaviors we identified were drawn from the wider literature, rather than generated specifically from our data, we believe it is likely the specific behaviors we identified will translate to other crimes in other contexts, but whether they are all used or used to the same extent and in the same combinations as identified in our proximity analysis is an empirical question that can be addressed in future studies. Our identification of patterns of behavior reminiscent of DARVO does suggest that the use of behaviors is likely to be at least partly dependent upon the nature of the crime under investigation and the relationship between the suspect and the victim.

Next, we should consider that we cannot yet determine the effectiveness of the identified behaviors. It seems likely that some influence behaviors are more effective than others, and so future work should seek to determine whether specific forms of influence are more or less persuasive. Naturally, such work would have to consider that there are likely to be individual differences in terms of the proficiency with which behaviors are used, and that specific arguments cannot be divorced from the context to which they apply.

Conclusion

Overall, we demonstrated that suspects employed a wide range of influence behaviors. It is important to note that these behaviors collapse into two comparatively simple dimensions that reflect the extent to which behaviors: (a) relate directly to evidence or else likely shift attributions made by interviewers, and (b) are likely deployed to establish dominance over or else respond to pressure from the interviewer. We also found that while all suspects used a wide range of behaviors, there is a comparatively small number of behaviors that are used extensively by most interviewees. These behaviors should be prioritized in future studies that should both assess the efficacy of influence behaviors and identify countermeasures. Studying the effectiveness of common influence behaviors is imperative for ensuring interviewees are afforded a fair opportunity to present their case, but without investigators becoming vulnerable to biased evaluations of the testimony of suspects, victims or other evidence.

Acknowledgements

We thank Becky Stevens for producing the evidence map figure (). We also thank participants at the ‘International Investigative Interviewing Research Group’ in Porto, 2018 for feedback on a presentation of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Unfortunately we are not able to share our data because of the security assurances given to our partner organisation.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbe, A., & Brandon, S. E. (2013). The role of rapport in investigative interviewing: A review. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 10(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1386

- Acedo, F. J., & Florin, J. (2007). Understanding the risk perception of strategic opportunities: a tripartite model. Strategic Change, 16(3), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.787

- Alison, J. (2008). ‘From where we're sat … ’: Negotiating narrative transformation through interaction in police interviews with suspects. Text & Talk, 28(3), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2008.016

- Alison, L., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., Waring, S., & Christiansen, P. (2014). Whatever you say, say nothing: Individual differences in counter interrogation tactics amongst a field sample of right wing, AQ inspired and paramilitary terrorists. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.031

- Anderson, K. l., & Umberson, D. (2001). Gendering VIOLENCE. Gender & Society, 15(3), 358–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015003003

- Auburn, T., Drake, S., & Willig, C. (1995). `You punched him, didn't you?': Versions of violence in accusatory interviews. Discourse & Society, 6(3), 353–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926595006003005

- Barlow, C., Johnson, K., Walklate, S., & Humphreys, L. (2019). Putting coercive control into practice: Problems and possibilities. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(1), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz041

- Barnett, J., & Breakwell, G. M. (2001). Risk perception and experience: Hazard personality profiles and individual differences. Risk Analysis, 21(1), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/0272-4332.211099

- Beune, K., Giebels, E., & Sanders, K. (2009). Are you talking to me? Influencing behaviour and culture in police interviews. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15(7), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802442835

- Beune, K., Giebels, E., & Taylor, P. J. (2010). Patterns of interaction in police interviews. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(8), 904–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810369623

- Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (1999). Measuring impression management in organizations: A scale development based on the Jones and Pittman taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods, 2(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819922005

- Bottoms, A. (2001). Compliance and community penalties. In A. Bottoms, L. Gelsthorpe, & S. Rex (Eds.), Community penalties: Change and challenges (pp. 87–116). Willan.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bull, R., & Soukara, S. (2010). Four studies of what really happens in police interviews. In G. Lassiter, & C. A. Meissner (Eds.), Police interrogations and false confessions: Current research, practice, and policy recommendations (pp. 81–95). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12085-000

- Cavanagh, K., Dobash, R. E., Dobash, R. P., & Lewis, R. (2001). `Remedial work': Men's strategic responses to their violence against intimate female partners. Sociology, 35(3), 695–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/s0038038501000359

- Cialdini, R. B. (2008). Influence: Science and practice (5th ed.). Pearson education.

- Clark, M. S., Pataki, S. P., & Carver, V. H. (1996). Some thoughts and findings on self-presentation of emotions in relationships. In G. J. O. Fletcher, & J. Fitness (Eds.), Knowledge structures in close relationships: A social psychological approach. Psychology Press.

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Crown Prosecution Service. (2017, June). Controlling or Coercive Behaviour in an Intimate or Family Relationship. https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/controlling-or-coercive-behaviour-intimate-or-family-relationship.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Freyd, J. J. (1997). II. Violations of power, adaptive blindness and betrayal trauma theory. Feminism & Psychology, 7(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353597071004

- Giebels, E. (2002). Beinvloeding in gijzelingsonderhandelingen: de tafel van tien. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor de Psychologie en Haar Grensgebieden, 57, 145–154.

- Giebels, E., Oostinga, M. S., Taylor, P. J., & Curtis, J. L. (2017). The cultural dimension of uncertainty avoidance impacts police–civilian interaction. Law and Human Behavior, 41(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000227

- Giebels, E., & Taylor, P. J. (2009). Interaction patterns in crisis negotiations: Persuasive arguments and cultural differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012953

- Giebels, E., & Taylor, P. J. (2010). Communication predictors and social influence in crisis negotiations. In R. G. Rogan, & F. Lancely (Eds.), Contemporary theory, research, and practice of crisis/hostage negotiations. Praeger.

- Gwet, K. L. (2008). Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 61(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711006X126600

- Harsey, S. J., Zurbriggen, E. L., & Freyd, J. J. (2017). Perpetrator responses to victim confrontation: DARVO and victim self-blame. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(6), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1320777

- Haworth, K. (2006). The dynamics of power and resistance in police interview discourse. Discourse & Society, 17(6), 739–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506068430

- Henning, K., Jones, A. R., & Holdford, R. (2005). “I didn’t do it, but if I did I had a good reason”: minimization, denial, and attributions of blame Among Male and female domestic violence offenders. Journal of Family Violence, 20(3), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-3647-8

- Kelly, C. E., Miller, J. C., & Redlich, A. D. (2016). The dynamic nature of interrogation. Law and Human Behavior, 40(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000172

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Leahy-Harland, S., & Bull, R. (2017). Police strategies and suspect responses in real-life serious crime interviews. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 32(2), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-016-9207-8

- Masip, J., & Herrero, C. (2013). ‘What would You Say if You were guilty?’ suspects' strategies during a hypothetical behavior analysis interview concerning a serious crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2872

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Newbury, P., & Johnson, A. (2006). Suspects’ resistance to constraining and coercive questioning strategies in the police interview. International Journal of Speech Language and the Law, 13(2), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsll.2006.13.2.213

- Pearse, J., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2002). The identification and measurement of ‘oppressive’ police interviewing tactics in britain. In G. H. Gudjonsson (Ed.), The psychology of interrogations and confessions (pp. 75–114). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713297.ch4

- Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63(4), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

- Salfati, C. G., & Taylor, P. (2006). Differentiating sexual violence: A comparison of sexual homicide and rape. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500036871

- Serious Crime Act. (2015). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/9/contents/enacted.

- Stokoe, E., Edwards, D., & Edwards, H. (2016). No Comment” responses to questions in police investigative interviews. In D. E. Susan Ehrlich, & J. Ainsworth (Eds.), Discursive constructions of consent in the legal process (pp. 289–317). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199945351.001.0001

- Strömwall, L. A., & Willén, R. M. (2011). Inside criminal minds: Offenders’ strategies when lying. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 8(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.148

- Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 664–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089195

- Taylor, P. J. (2002). A cylindrical model of communication behavior in crisis negotiations. Human Communication Research, 28(1), 7–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00797.x

- Taylor, P. J. (2006). Proximity coefficients as a measure of interrelationships in sequences of behavior. Behavior Research Methods, 38(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192748

- Taylor, P. J., & Donald, I. (2007). Testing the relationship between local cue–response patterns and the global structure of communication behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466606X112454

- Taylor, P. J., Larner, S., Conchie, S. M., & Menacere, T. (2017). Culture moderates changes in linguistic self-presentation and detail provision when deceiving others. Royal Society Open Science, 4(6), https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170128

- Walby, S., & Towers, J. (2018). Untangling the concept of coercive control: Theorizing domestic violent crime. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817743541.

- Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., Wedding, D., & Gwet, K. L. (2013). A comparison of Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-61

Appendix

1. Codes included within our coding framework that were excluded for insufficient occurrences in the suspects testimony (< 30 instances)