ABSTRACT

With increasing numbers of prisoners, research on Swedish prison officers’ perceptions of management and support at work is warranted. Previous studies have mainly used a variable-centered approach, identifying several individual and organizational factors that influence prison staff's evaluation of their job. The present study adopted a person-centered approach, exploring the heterogeneity in a Swedish national sample of prison officers. Based on an extensive survey of the quality of prison job, 10 key predictors for overall prison regime evaluation were identified. Following latent class analysis, three distinct subgroups were discerned from the entire sample. Remarkably, a sizable subgroup with a relatively negative evaluation of the prison regime was observed. While most background covariates did not associate with the subgroup membership, prison officers who experienced violent or threatening incidents tended to report a negative evaluation of the prison regime. Intra-organizational social support, communication and loyalty are highlighted as key components of overall regime evaluation. Our findings suggest that enhancing collegial, management, and supervision support and communicative skills may increase prison officers’ job satisfaction. Beyond the organizational level of prisons, we also discussed the challenges that the Swedish prison system faces, along with the portrayal by social media of a violence-dominated environment.

Introduction

The role of prison officer (also known as correctional officer) has been found to be a stressful occupation across countries (Schaufeli & Peeters, Citation2000). They have poorer mental health than the general population to a worrying extent, although exposure to violent threats at work could exacerbate this detrimental effect (Jaegers et al., Citation2022; James & Todak, Citation2018). Therefore, it is important to understand how prison officers perceive their work environment, as such perceptions could inform future improvement in both work conditions and management. As Lambert et al. (Citation2005) have pointed out, the job satisfaction of prison officers is not merely a subjective attitude, but has real consequences for their life satisfaction, as well as for prison and society.

In the past decades, several determinants of prison officers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment have been identified. Noticeably, prison management is a key predictor of job satisfaction (Britton, Citation1997; Castle, Citation2008; Van Voorhis et al., Citation1991). Early research has noted that proactive management and perceived support at work are beneficial for prison officers (Härenstam et al., Citation1988). With more specific research foci, researchers found that better supervisory support is related to higher job satisfaction (Britton, Citation1997; Castle, Citation2008). Furthermore, a recent study examined the social support system of prison officers, noting that support from colleagues, supervisors and management are related to higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Lambert et al., Citation2016).

There have been ongoing debates about how individual characteristics (e.g. gender, age) as well as organizational factors (e.g. management, schedules) are important for the job satisfaction of prison officers (Castle, Citation2008; Farkas, Citation1999, Citation2001; Lambert et al., Citation2002; Lambert et al., Citation2010). While perceived dangerousness (i.e. the threat of violence and so forth which has been identified in other research) is a detrimental factor for job satisfaction among prison officers (Lambert et al., Citation2004; Lambert et al., Citation2005), studies consistently indicate that the prison security level (also known as ‘prison security classification’) is not a significant correlate (Dowden & Tellier, Citation2004; Garland et al., Citation2009). Similarly, whereas procedural justice (i.e. perceived fairness about the decision-making process in an organization) contributes to job satisfaction among prison officers in the U.S. (Lambert et al., Citation2007; Lambert et al., Citation2020), this pattern is absent among the Chinese prison officers (Jiang et al., Citation2016). Despite some conflicting findings, environmental work factors and how prison staff perceive them have been recognized as a research focus of job satisfaction because these issues are more manageable than the fixed individual background factors such as demographics (Lambert et al., Citation2002).

Like other client-driven occupations, emotional dissonance (i.e. prison officers feel and act in contradictory ways in their work) is related to prison officers’ work stress (Tewksbury & Higgins, Citation2006). Emotional demand is especially salient in prisons as relationships between prison officers and prisoners are usually emotionally charged (Crawley, Citation2004). As demonstrated in previous qualitative studies conducted among English (Crawley, Citation2004) and Swedish (Nylander et al., Citation2011; Wästerfors, Citation2007) prison officers, violence or threat (including a wide range of forms, from verbal abuse to riots) is an urgent issue in prison work. The aggressive behaviors from prisoners negatively impact on prison officers’ mental and physical wellbeing, especially in understaffed prisons (Clements et al., Citation2020). Exposure to these violent incidents and threats at work results in more job stress, which in turn lowers prison officers’ job satisfaction as well as organizational commitment (Griffin et al., Citation2010; Jaegers et al., Citation2022; Lambert & Paoline, Citation2008).

Although advanced statistical analysis was suggested for correctional management research decades ago (Farkas, Citation2001), this call has not been well responded to. Methodologically, a pragmatic and researcher-centered perspective may have overlooked the naturally emerged structure in the data because this perspective usually tests a set of preexisting theories following directional analyses such as multiple regression. As has been already recognized (Lambert et al., Citation2002; Mathieu & Zajac, Citation1990), a data-driven approach to understanding the perceptions regarding job satisfaction and organizational commitment is promising. With a large set of candidate predictors, one of this study's aims is to identify a parsimonious selection of model that best predicts participants’ overall regime evaluation. A similar analytical method has been applied to psychological studies when researchers need to select the most relevant beliefs of a certain behavioral intention (von Haeften et al., Citation2001). Compared with factor analysis which assumes that specific perceptions are formed by some known common causes, our approach could further capture the complex interactions among perceptions.

Most previous quantitative studies on prison officers’ attitudes or perceptions are variable-centered, while the person-centered approach has had few applications thus far. A person-centered perspective is another novel application of this study. Using latent class analysis and similar methods, the person-centered approach (McLachlan & Peel, Citation2000; Muthén & Muthén, Citation2000) focuses on unobserved subpopulations – subgroups of staff who can be defined on the basis of their individual differences such as personal traits, background and competence – rather than the mean scores of certain variables. So far, latent class analysis has been commonly applied in social sciences including the research field of job satisfaction. For instance, using a national dataset, Yeşilyaprak and Boysan (Citation2015) found four latent classes in job satisfaction among American school counselors, revealing a ‘very dissatisfied’ subgroup (12.14%). This application could also reveal whether there is a dissatisfied subgroup among prison officers.

Research objective

Our study focuses on prison officers in Sweden. Currently, the situation in Swedish prisons is subject to ongoing debates. As a result of growing problems in society with increasing criminality such as gang shootings and violence, Swedish prisons have become increasingly overcrowded (Aebi & Tiago, Citation2020). An important question is how this situation has affected prison staff and their work environment. As criminal justice authorities and politicians from different camps agree that the prison capacity in Sweden should be immediately expanded, our survey provided a timely understanding of prison staff's evaluation of their work.

Sweden had 46 prisons with approximately 5000 prisoners at the time of our study. The prisons are organized and classified in accordance with three security levels: high (Category 1), middle (Category 2) and low security (Category 3). Staff turnover was roughly 10% per year. Sweden has sometimes been described as belonging to a ‘Scandinavian exceptionalism’ tradition with low prison populations and better prison facilities than many other countries (Pratt, Citation2007). However, Swedish prisons have seen dramatic changes in the last decades. In the 1990s, a personal officer reform stated that every prison officer should be responsible for a number of prisoners, between three and ten, whom they should assist with social guidance and planning. In 2004, after several escapes from high-security prisons, a ‘security turn’ took place. This was comprised of the implementation of a large number of physical, technical and administrative security measures in all prisons. The prison services were centralized from local authorities to a few regional offices and a national headquarters. The recipe of New Public Management (NPM) – private company solutions introduced to public organizations – had finally reached the Swedish Prison and Probation Services (Kriminalvården). This implied coherent solutions and centralized decisions for all prisons. Moreover, this was accompanied by imported treatment programs mostly based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) applied to prisoners who were already motivated. Consequently, the personal officer role – with its aim of advancing the prison officer function toward more relational and motivational work with prisoners – was downplayed (see e.g. Bruhn, Lindberg, et al., Citation2017; Bruhn, Nylander, et al., Citation2017).

Employing a data-driven and exploratory research approach, the present study was guided by three major interrelated research aims. First, we utilized the evaluation of the overall prison regime as the target to select a best subset from the prison job scales. In contrast to simply entering all predictors in the model, this analysis would inform a parsimonious model selection. Second, latent class analysis was used to examine the existence of subpopulations who held distinct patterns of beliefs. As shown in previous research (Yeşilyaprak & Boysan, Citation2015), this person-centered analysis could illustrate the heterogeneity in Swedish prison officers’ perceptions. Third, based on the optimal latent class model, we examined the relationships between background variables and subgroup membership.

Methods

Procedure and participants

Our national survey was conducted among Swedish prison officers in November and December 2019. A paper survey was not allowed by the authorities, therefore, we undertook the survey online with the help of the unions. The recruitment of respondents was preceded via a private email or the staff email system at the Swedish Prison and Probation Services. Research and consent information was included in the recruitment invitation email. Once consent had been given, participants were able to access and complete the online survey. A research invitation email was sent to approximately 1400 email addresses that were randomly selected from the registers of the two unions; 516 valid answers were obtained (respondent rate: 36.9%). The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Board (DNR 2019-04825) before data collection.

The participants in our sample had a wide age range (from 20 to 65 years; Mage = 43.45 years, SD = 11.86); there were 60.2% men and the majority of the sample (84.2%) had been born in Sweden. The sample showed a similar distribution of age and gender to that of the official statistics of the entire population of Swedish prison officers. The majority (98.2%) had received at least some high school education. Most of the officers (92.8%) were fulltime employees. Over half (59.2%) of the participants had over five years of work experience in the prison system. With regard to security levels, 10.1% and 28.2% worked in Category 3 and 1 prisons, respectively, while 61.7% worked in a Category 2 prison. While 45.5% of the officers had not been subjected to violence, threats, or harassment by inmates in the previous year, 12.8% reported that they had been once, 19.8% reported that it had happened two to three times, and 21.8% reported more than three times.

Measures

The survey was composed of quality of job items and demographic variables. All questions were in Swedish. The items were first tested in small pilot studies.

Quality of prison job was assessed using 117 questions. The survey was almost identical with a survey originally developed and conducted in 2009 (Nylander, Citation2011). The items in these surveys had a wide range of questions about work environment and occupational issues, but subsequently, we will refer to them as ‘Quality of prison job’ (for complete items, see the Appendix). These items are inspired by the British quality of prison life (staff version) scale (Arnold et al., Citation2007). All questions were measured with a 5-point Likert scale with a neutral alternative in the middle ([1] totally agree to [5] totally disagree). For better interpretation, all scores were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated a greater degree of agreement with the statement.

From these 117 questions we used two items to represent Overall regime evaluation: ‘I have confidence in the management of the prison’, ‘This prison is well organized’. These two items are positively correlated (ρ = 0.61, p < 0.001). A mean score was calculated so that a higher score meant a more positive overall evaluation of the management in the respondent's prison.

Background variables included age, gender, working status (fulltime/temporary), prison work experience (less than 5 years/5–10 years/over 10 years), prison security level (Category 1, 2, or 3), highest education level, unit colleague number, place of birth (Sweden/other European place/non-European), violent or threat experience by inmates in the past year (never/once/2–3 times/over three times).

Analytical plan

To reduce the dimension of the quality of job items, we used stepwise regression with the overall regime evaluation as the target. Stepwise regression is typically used as a method to select a subset of independent variables that effectively predict the outcome variable (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). While there may be a structure within these 117 items, it is important to note that our research focus was to identify a parsimonious set of items that best predicted the overall regime evaluation. Utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0, we entered all 115 items from the quality of prison job scale as the model predictors with stepwise as the regression method.

The subset generated in the final model in the previous stage was subsequently used as the indicator of the latent class analysis. As a person-centered approach that focuses on individual response patterns and subgroups among respondents (Jung & Wickrama, Citation2008; Muthén & Muthén, Citation2000), the latent class analysis has not been widely used in prison staff research thus far. To select the optimal model, we performed 2-class to 5-class solutions. As suggested by Wickrama et al. (Citation2022), model selection was based on Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), entropy and adjusted Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR−LRT). Lower AIC and BIC values indicate better model fit (Feldman et al., Citation2009), higher entropy scores signify clearer cluster separation (Feldman et al., Citation2009), and significant results (i.e. p < 0.05) in the adjusted LMR–LRT show a statistical improvement when class number increased from k − 1 to k (Lo et al., Citation2001).

Based on the final latent class model, all demographic variables were included as background covariates to examine their relationships with the class membership. Although all solutions in our analyses are regarded as good class separations (i.e. entropy > 0.80), we utilized the pseudo-class draws to cope with the classification accuracy (Wang et al., Citation2005). The latent class analysis and analysis using pseudo-class draws methods were undertaken with Mplus 8.2.

Results

Subset for overall regime evaluation

Following stepwise regression, 10 models were generated as they showed significant ΔF results (i.e. p ≤ 0.01). In the final model (ΔF(1, 325) = 6.73, p = 0.010), 10 independent variables were included (). All variables reached a statistically significant level in the model, with perceived loyalty showing the strongest association (B = 0.26, p < 0.001) with overall regime evaluation. The final subset explained 72.2% of the variance in overall regime evaluation. Statistically, these 10 variables are key to explaining the overall regime evaluation.

Table 1. Final subset following stepwise regression predicting overall regime evaluation.

Identification of subgroups

Based on the fit statistics of 2- to 5-class models (), AIC and BIC values showed a decreasing trend when the class number increased. All entropy indices were over 0.80, indicating good class separations (Wickrama et al., Citation2022). However, the adjusted LMT–LRT results suggested that no statistical improvement was detected when the number of classes increased from 3 to 4. Thus, the 3-class solution was deemed as the optimal model.

Table 2. Model fit statistics from 2- to 5-class solutions.

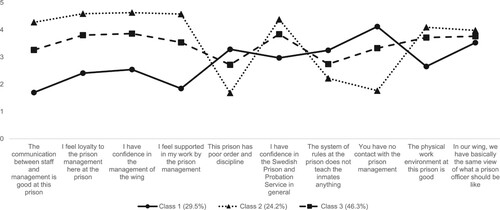

delineates three subgroups. Approximately half of the sample (Class 3; 46.3%) showed a generally neutral attitude toward all indicators. In contrast, Class 2 members (24.2%) had an overall positive view on all items, while Class 1 members (29.5%) possessed a relatively negative evaluation on the indicators.

Covariates of class membership

Using the pseudo-class draws method, only violence or threat experience was found as a significant predictor for Class 1 membership (B = 0.25, p = 0.046) using Class 2 as the reference subgroup. This finding means that, compared with Class 2 members, Class 1 members had more violence or threat experiences in their work as prison officers in the previous year. Interestingly, in the same comparison, Class 3 members did not show different violent experience than Class 2 members (B = 0.14, p = 0.244).

Discussion

Using a Swedish national dataset, our study identified the key variables for overall regime evaluation among prison officers. Three subgroups were discerned using latent class analysis, and violence or threat experience in the past year was found to be the only statistical meaningful subgroup covariate. Specifically, these three subgroups represent high, medium and low levels of job satisfaction and evaluation of work environment. The subgroup which possessed lower job satisfaction was more likely to have experienced violence in the last year. The implications from the findings and possible future research directions are discussed below.

Following our first research aim, we have successfully reduced the dimension of the original scale. Only 9% of the 115 items explained a substantial (72.2%) variance in the outcome variable. This result assists us in understanding the key variables influencing the overall regime evaluation, as well as helping us to develop future brief versions of the quality of prison job scale. Several themes exist in these key predictors. First, perceived management and support at work appears to be salient, in congruence with the three components of intra-organizational support proposed by Lambert et al. (Citation2016), highlighting the roles of management, supervision and colleagues in establishing job satisfaction among prison officers. Moreover, several predictors regarding communication within the organization are in line with intra-organizational support. Second, positive emotions toward the organization, such as confidence and loyalty, are highly associated with prison officers’ overall regime evaluation. Since work stress has been found as one major correlate of job satisfaction (Lambert et al., Citation2002), our finding with regard to these positive emotions provides unique knowledge in this field. With the egalitarian historical background of a social democratic regime (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990), and specific to the Swedish context, the organizational dynamics in Swedish prisons may have been infused with a group orientation. For example, a previous Swedish study found that solidarity could be a protective factor for pro-environmental behavior (Torbjörnsson & Molin, Citation2014). Research on prison officers may further investigate the relationships between loyalty and their organizational commitment.

Using a person-centered approach, our findings provide novel results in the field of prison staff research. A fact of particular concern relates to the Class 1 members, who account for 29.5% of the sample; they report a relatively negative view of all management items. Some previous findings based on variable-centered analysis suggest that officers’ background factors, such as gender and education level, are related to their perceptions of the working environment (Britton, Citation1997; Castle, Citation2008). In contrast, only the exposure to violence and threat was found to be a significant covariate between two subgroups in our person-centered analysis. Such discrepancy highlights the need to conduct more person-centered studies among prison staff, as this cohort may not be a homogeneous cohort as conventionally assumed. Future studies may also utilize longitudinal designs to capture the changing trajectories at the individual level (Jung & Wickrama, Citation2008).

In previous research, violence and work stress in the prison environment had a negative effect on job satisfaction (Castle, Citation2008). Violence and work stress could influence prison officers’ apprehension of supervision in their work (Tewksbury & Higgins, Citation2006). Consistently, more exposure to violence and threats have played a significant role in differentiating the subgroups with negative and positive attitudes toward prison management and regime in our study. With a focus on power types, Stichman and Gordon (Citation2015) found that higher expert power (i.e. perceived readiness and ability to handle disruptive situations) is related to less fear and perceived risk. Thus, it is possible that expert power, readiness and perceived abilities serve as unobserved variables mediating the relationship between job satisfaction and violence.

In recent years, there has been an ongoing trend of centralization in the Swedish prison system, following the recipe of New Public Management (Bruhn, Lindberg, et al., Citation2017) and similar tendencies seem to be also present in the prison systems of other countries (see e.g. Liebling et al., Citation2011). In addition, the Swedish prison population has been increasing, and many Swedish prisons today are overcrowded. Further, the trend of centralization has enforced the clinical use of low-performing prison programs at the expense of declining room for the ordinary prison officer's motivational and relational work with prisoners. This may have led to feelings of impoverishment in terms of the occupational role (Lardén et al., Citation2006). Last, we must point to the overall prioritizing of security and control measures, at the expense of rehabilitation goals, risking the widening of the gap between staff and prisoners. Such structural and systematic transformations may further explain ambiguities in the prison officers’ occupational role and their vulnerability to threats from prisoners, as well as the existence of a prison officer subgroup with negative attitudes toward the management and regime of prisons. Social media that often portrays prison as a place with violence could also have an impact on prison officers’ perceptions about their working environment (Mason, Citation2006). Swedish prison authorities should further investigate strategies to mitigate the effects of violence and threat at work, at the same time as considering the wider changes in the prison system and societal discourse about incarceration.

The present study provides several practical implications for prison management. In line with the intra-organizational social support system proposed by Lambert et al. (Citation2016), prisons need to create opportunities to enable support within the organization. As communication has been highlighted, a first step could be to understand the need and work stress among staff, so as to develop meaningful interventions (Griffin et al., Citation2010). As social support is a well-established area in social psychology, future research could utilize the two-way perspective to identify the direction (i.e. receiving, giving) and type (e.g. emotional, informational) of social support (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, Citation2011). It is also important to develop effective education to enhance prison officers’ readiness and ability to manage difficult cases at work (Stichman & Gordon, Citation2015). Future studies may also adopt frameworks from positive psychology and examine the culturally appropriate strategies to improve organizational loyalty. In the long run, such intervention and education could help to reduce the turnover rates among Swedish prison officers.

Our study has several limitations. The relatively low respondent rate (36.9%) may have unintentionally precluded the expression of different views about the institution by some officers. Given the response to an earlier similar study using a paper survey (Nylander, Citation2011), the respondent rate could have been improved with paper-based questionnaires. Our sampling was helped by unions, and it is possible that some newly employed staff were not included in the survey. This study is based on self-reported data, which could be enhanced if objective metrics (e.g. the number of violent incidents) had been simultaneously collected. As we are using a person-centered approach, future latent class analysis models could include indicators regarding personal traits – for example, individual and group loyalty traits (Beer & Watson, Citation2009) – to assist the subgroup interpretation. Similarly, psychosocial scales, such as stress and wellbeing, could also be included as covariates to explain the subpopulations. Given the cross-sectional nature of our research design, the associations between perceived threat and job satisfaction need further studies to clarify the causality. For instance, it is unclear whether perceived threat caused the formation of the subgroup with lower job satisfaction. However, our study uses a national dataset and quantitatively examined the sample identifying the subgroups among prison officers. This quantitative method is promising in criminology to thoroughly illustrate participants’ profiles, serving as a novel research avenue for future research.

In conclusion, intra-organizational support has been identified as an important component of overall regime evaluation among Swedish prison officers. A sizable subgroup featured in lower job satisfaction was found using a person-centered analytical approach. Our study highlights the roles of social support and communication at work. Education targeting collegial, supervisory, and management relationships could enhance prison officers’ job satisfaction. Training that prepares prison officers to handle difficult situations may be helpful in reducing their perceptions of danger and threat within their work environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Aebi, M. F., & Tiago, M. M. (2020). Prisons and prisoners in Europe in pandemic times: An evaluation of the short-term impact of the COVID-19 on prison populations. Council of Europe.

- Arnold, H., Liebling, A., & Tait, S. (2007). Prison officers and prison culture. In Y. Jewkes (Ed.), Handbook on prisons (pp. 471–495). Willan Publishing.

- Beer, A., & Watson, D. (2009). The Individual and Group Loyalty Scales (IGLS): construction and preliminary validation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890902794341

- Britton, D. M. (1997). Perceptions of the work environment among correctional officers: Do race and sex matter? Criminology; An Interdisciplinary Journal, 35(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1997.tb00871.x

- Bruhn, A., Lindberg, O., & Nylander, PÅ. (2017). Treating drug abusers in prison: Competing paradigms anchored in different welfare ideologies. The case of Sweden. In P. Scharff Smith & T. Ugelvik (Eds.), Scandinavian penal history, culture and prison practice: Embraced By the welfare state? (pp. 177–204). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58529-5_8

- Bruhn, A., Nylander, PÅ, & Johnsen, B. (2017). From prison guards to … what? Occupational development of prison officers in Sweden and Norway. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 18(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14043858.2016.1260331

- Castle, T. L. (2008). Satisfied in the jail?: Exploring the predictors of job satisfaction among jail officers. Criminal Justice Review, 33(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016808315586

- Clements, A. J., Kinman, G., & Hart, J. (2020). Stress and well-being in prison officers. In R. J. Burke & S. Pignata (Eds.), Handbook of research on stress and well-being in the public sector (pp. 137–151). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788970358.00018

- Crawley, E. (2004). Doing prison work: The public and private lives of prison officers. Willan Publishing.

- Dowden, C., & Tellier, C. (2004). Predicting work-related stress in correctional officers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2003.10.003

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- Farkas, M. A. (1999). Correctional officer attitudes toward inmates and working with inmates in a “get tough” era. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(6), 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(99)00020-3

- Farkas, M. A. (2001). Correctional officers: What factors influence work attitudes? Corrections Management Quarterly, 5(2), 20–26.

- Feldman, B. J., Masyn, K. E., & Conger, R. D. (2009). New approaches to studying problem behaviors: A comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 652–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014851

- Garland, B. E., Mccarty, W. P., & Zhao, R. (2009). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in prisons: An examination of psychological staff, teachers, and unit management staff. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808327343

- Griffin, M. L., Hogan, N. L., Lambert, E. G., Tucker-Gail, K. A., & Baker, D. N. (2010). Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(2), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809351682

- Härenstam, A., Palm, U.-B., & Theorell, T. (1988). Stress, health and the working environment of Swedish prison staff. Work & Stress, 2(4), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678378808257489

- Jaegers, L. A., El Ghaziri, M., Katz, I. M., Ellison, J. M., Vaughn, M. G., & Cherniack, M. G. (2022). Critical incident exposure among custody and noncustody correctional workers: Prevalence and impact of violent exposure to work-related trauma. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 65(6), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23353

- James, L., & Todak, N. (2018). Prison employment and post-traumatic stress disorder: Risk and protective factors. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 61(9), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22869

- Jiang, S., Lambert, E. G., Zhang, D., Jin, X., Shi, M., & Xiang, D. (2016). Effects of work environment variables on job satisfaction among community correctional staff in China. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(10), 1450–1471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816633493

- Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2002). Satisfied correctional staff: A review of the literature on the correlates of correctional staff job satisfaction. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 29(2), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854802029002001

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Griffin, M. L. (2007). The impact of distributive and procedural justice on correctional staff job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(6), 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.09.001

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Jiang, S., Elechi, O. O., Benjamin, B., Morris, A., Laux, J. M., & Dupuy, P. (2010). The relationship among distributive and procedural justice and correctional life satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intent: An exploratory study. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.11.002

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Paoline, E. A., & Baker, D. N. (2005). The good life: The impact of job satisfaction and occupational stressors on correctional staff life satisfaction—an exploratory study. Journal of Crime and Justice, 28(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2005.9721636

- Lambert, E. G., Keena, L. D., Leone, M., May, D., & Haynes, S. H. (2020). The effects of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction and organizational commitment of correctional staff. The Social Science Journal, 57(4), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2019.02.002

- Lambert, E. G., Minor, K. I., Wells, J. B., & Hogan, N. L. (2016). Social support’s relationship to correctional staff job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. The Social Science Journal, 53(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2015.10.001

- Lambert, E. G., & Paoline, E. A. (2008). The influence of individual, job, and organizational characteristics on correctional staff job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Criminal Justice Review, 33(4), 541–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016808320694

- Lambert, E. G., Reynolds, K. M., Paoline, E. A., & Watkins, R. C. (2004). The effects of occupational stressors on jail staff job satisfaction. Journal of Crime and Justice, 27(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2004.9721627

- Lardén, M., Melin, L., Holst, U., & Långström, N. (2006). Moral judgement, cognitive distortions and empathy in incarcerated delinquent and community control adolescents. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12(5), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500036855

- Liebling, A., Price, D., & Shefer, G. (2011). The prison officer (2nd ed.). Willan Publishing.

- Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

- Mason, P. (2006). Lies, distortion and what doesn’t work: Monitoring prison stories in the British media. Crime, Media, Culture, 2(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659006069558

- Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

- McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. John Wiley & Sons.

- Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(6), 882–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x

- Nylander, P-Å. (2011). Managing the dilemma: Occupational culture and identity among prison officers [Doctoral thesis]. Örebro University.

- Nylander, P-Å, Lindberg, O., & Bruhn, A. (2011). Emotional labour and emotional strain among Swedish prison officers. European Journal of Criminology, 8(6), 469–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811413806

- Pratt, J. (2007). Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess: Part i: The nature and roots of Scandinavian exceptionalism. The British Journal of Criminology, 48(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azm072

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2000). Job stress and burnout among correctional officers: A literature review. International Journal of Stress Management, 7(1), 19–48. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009514731657

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Obst, P. L. (2011). The development of the 2-Way Social Support Scale: A measure of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(5), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.594124

- Stichman, A. J., & Gordon, J. A. (2015). A preliminary investigation of the effect of correctional officers’ bases of power on their fear and risk of victimization. Journal of Crime and Justice, 38(4), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2014.929975

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Tewksbury, R., & Higgins, G. E. (2006). Prison staff and work stress: The role of organizational and emotional influences. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(2), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02885894

- Torbjörnsson, T., & Molin, L. (2014). Who is solidary? A study of Swedish students’ attitudes towards solidarity as an aspect of sustainable development. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.886153

- Van Voorhis, P., Cullen, F. T., Link, B. G., & Wolfe, N. T. (1991). The impact of race and gender on correctional officers’ orientation to the integrated environment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 28(4), 472–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427891028004007

- von Haeften, I., Fishbein, M., Kasprzyk, D., & Montano, D. (2001). Analyzing data to obtain information to design targeted interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 6(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500125076

- Wang, C.-P., Hendricks Brown, C., & Bandeen-Roche, K. (2005). Residual diagnostics for growth mixture models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 100(471), 1054–1076. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214505000000501

- Wästerfors, D. (2007). Fängelsebråk: analyser av konflikter på anstalt. Studentlitteratur.

- Wickrama, K. A. S., Lee, T. K., O’Neal, C. W., & Lorenz, F. O. (2022). Higher-order growth curves and mixture modeling with Mplus: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Yeşilyaprak, B., & Boysan, M. (2015). Latent class analysis of job and life satisfaction among school counselors: A national survey. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9491-2

Appendix

Complete quality of prison job items (English translation)

The physical work environment at this prison is good.

We prison officers have no place where we can ‘talk in private’ with colleagues undisturbed.

I feel safe in my work environment.

As a prison officer, you can feel secure about your employment.

Prison officers at this prison have too little personal responsibility for their work.

The opportunity to influence one's own work situation is too limited here.

The management at the prison encourages the staff to take initiatives in their own work.

Prison officers at this prison have too little influence over the design of the business.

The immediate management here does not have many possibilities to exert influence on higher levels of management.

The communication between staff and management is good at this prison.

I have enough time to keep up with my work tasks.

It is often difficult to reconcile the different requirements placed on a prison officer.

Mostly, I have time to reflect on my work during working hours.

Administrative tasks and institutional routines affect contact with inmates.

Constantly having to deal with inmates’ emotions and emotional outbursts is the most difficult part of this job.

Inmates violating staff is unusual in this prison.

It is often difficult to ‘turn off’ thoughts and feelings when I leave work.

The risk of suicide and suicide attempts by inmates is very stressful.

I get enough further education in my work.

The guidance support for personal officers works well.

There are too few development paths for prison officers.

I do not get the opportunity to fully use my skills in the work here.

I get support and help from my immediate superior when I have difficulties at work.

I feel supported in my work by the prison management.

I get support and help from my colleagues in my wing when I have difficulties at work.

I feel well informed about what is happening within the prison.

I rarely get appreciation for my work.

It's hard to get time off from here when I need to.

My working hours make it difficult to combine work with leisure and family life.

The prison officers are underpaid.

The emotional exertion of work means that I can barely get involved with my family in my spare time.

The workload is very uneven in this workplace.

Working never goes as planned.

I have confidence in the management of the wing.

I have confidence in the management of the prison.

I have confidence in the Swedish Prison and Probation Service in general.

The management of the wing has too little responsibility, here.

The management of the wing is available when I need to discuss an issue.

I have confidence in how our work efforts are valued at this prison.

This prison is well organized.

You have no contact with the prison management.

The principal officer is very present in the work.

I feel respected by my colleagues here at the prison.

There is good communication between colleagues in different departments at this prison.

The respect between colleagues with different tasks is good at this prison.

The view of how a prison officer should be differs greatly between officers in different wings, here.

I try not to get too involved in the prison management's plans for this prison.

In our wing, we have basically the same view of what a prison officer should be like.

The cohesion between the staff in our wing is strong.

There is quite a lot of ‘them and us’ between the staff in different wings, here.

I feel loyal to the prison management here at the prison.

Loyalty is mainly felt between colleagues in their own wing.

Our work at the prison corresponds well with the Swedish Prison and Probation Service's vision (Better at release).

Dealing with the inmates’ emotions takes up a significant part of my working time.

The general atmosphere within this prison is tense.

The morale is good among the staff at this prison.

This prison has poor order and discipline.

Security thinking has gone too far in this prison.

It is unusual for staff to abuse inmates at this prison.

Some staff don't do much at the prison.

I applied for the job as a prison officer because I wanted to work with people.

I saw the job as a prison officer as a way to gain experience and qualifications of other work (care, police, etc.).

It was a coincidence that I ended up in this job.

Comradeship with co-workers is probably the most important reason for why you enjoy a job.

For me to thrive, a job must contain good opportunities to develop.

Decent working conditions (working time, security, salary) are the most important things in a job.

In this region, you have to take the jobs that are offered.

I do not feel motivated to do more than exactly what is required by my work.

In recent years, the focus on improved external security has been necessary.

The most satisfying tasks are those that include contact with inmates.

The Prison and Probation Service's most important task is to keep criminals securely locked up.

The Prison and Probation Service's most important task is to contribute to criminals’ adaptation to a normal life.

I feel a strong concern about the increased emphasis on punishment in public debate.

The prison officers must work with motivational programs.

The motivational programs do not lead to the rehabilitation of inmates.

I like helping inmates work towards set goals.

In general, prison officers are not equipped to perform the work of a good personal officer.

Being a personal officer for inmates is one of the most stimulating tasks for a prison officer.

More training is needed regarding the administrative work required for a personal officer role.

There is not enough space for a prison officer to carry out good rehabilitation work.

Staff need more training and support to deal with the effects of suicide and suicide attempts.

It is important to keep one's distance from the inmates.

Inmates take advantage of you if you are lenient.

Prison officers need more training in understanding ethnic and cultural differences.

Sometimes you have to defend an inmate against your colleagues.

Inmates must be subject to strict discipline.

If an inmate lies, they get no help from me.

I often feel uncertain about how to support inmates and therefore refrain from doing so.

Most inmates can be rehabilitated.

This prison is too comfortable for the inmates.

The system of rules at the prison does not teach the inmates anything.

It is important to show the inmates respect.

Close relationships with the inmates undermine their respect for you.

I try to build trust with inmates.

Working at this prison is very emotionally demanding.

I try to ignore my real feelings when working with inmates.

I have enough authority to do my job well.

Inmates are happy to come to me with their problems.

It is important to get involved with inmates and their problems.

The feelings I show inmates are the ones I really feel.

Being a professional in this job often means hiding what you really feel.

Good and functioning relationships with the inmates are the best form of security.

The fact that rules and routines are applied equally by all staff is the best guarantee of safety.

At this prison, there are too many prison officers who overlook the inmates’ rule violations.

The Prison and Probation Service's management should be more flexible in how security rules are applied in different prisons.

Male prison officers often have more distance from the inmates than female prison officers.

An even gender balance among the prison staff is best.

Female prison officers often become overly emotionally involved when helping inmates.

Strong male dominance among the prison officers on a wing leads to an overly ‘boyish’ environment.

Too many female prison officers on a wing create more pressure on the male ones when it comes to safety.

Inmates are happy to seek out female prison officers when it comes to personal problems.

The Swedish Prison and Probation Service values me as a staff member.

The status of the prison officer job is too low in society.

I usually avoid saying where I work when I meet new people.

The formal training requirements for prison services should be improved.

Too many who do not know anything speak in the debate about the prison service.

The media influences criminal policy far too much.