ABSTRACT

Although support by experiential peers for individuals with criminal behaviour is increasing, an empirical basis for its effectiveness is lacking. The purpose of this review was to investigate outcomes, mechanisms, and contextual factors of individual support by experiential peers for individuals who display criminal behaviour. We conducted a systematic realist literature review to test and refine our initial programme theory, which included seven mechanisms that may play a role in the desistance-supportive outcomes of experiential peer support. We screened 6,530 scientific papers and eventually included 25 articles focusing on asymmetrical one-on-one support for and by individuals with criminal behaviour. The findings suggest that experiential peers show empathy and have a non-judgmental approach, are considered role models, establish a trusting relationship with clients, offer hope, connect clients to other services, and have a recovery perspective on desistance. We found results indicative of act-desistance, positive personal development and improvements in mental health and personal circumstances, although study results were not consistent. The information on contextual factors was too limited for a robust analysis. Future research should not only focus on objective measures (e.g. absence of criminal behaviour), but also on subjective measures (e.g. hope, self-esteem) and investigate long-term effects.

Background

In addition to professional knowledge, experiential knowledge is gaining more attention and appreciation in mental healthcare (Chamberlin, Citation2005). Clients’ perspectives have become more important, since they can help practitioners in the development of more meaningful and supportive approaches (Hughes, Citation2012). Specifically, in mental health services oriented at recovery, the involvement of (former) clients has become important (Kortteisto et al., Citation2018). This is visible in their involvement in the development of interventions and in the delivery of support to clients. In this study, we refer to this support as ‘experiential peer support’, which we define as intentional unidirectional peer support, a formalised mentorship type of peer intervention (Barker et al., Citation2020). It involves an asymmetrical relationship, with a designated recipient (the client) and a designated provider of the support (the experiential peer – EP) (Davidson et al., Citation2006). The experiential peer support takes place in a professional setting and is therefore not a naturally occurring relationship between people with similar experiences. In the field of criminal justice and the rehabilitation of individuals involved in criminal behaviour, this type of experiential peer support is upcoming. Several large cities in the United States have seen an expansion of state-funded peer-mentoring initiatives for young people involved in the criminal justice system (Lopez-Humphreys & Teater, Citation2019); and in the United Kingdom, peer mentoring was a central component of the 2012 government plans to transform rehabilitation of prisoners (Buck, Citation2018).

People displaying criminal behaviour do not necessarily consider their behaviour as problematic for themselves and may therefore be less interested in help. In addition, negative attitudes towards seeking help and negative experiences with formal care might form a barrier to seeking or accepting help (Lenkens et al., Citation2019a; Rickwood et al., Citation2007). Experiential peers (EPs), however, might have an advantage in reaching this population, because people are more likely to connect with people similar to themselves (McPherson et al., Citation2001). These similarities can refer to similar experiences, such as coping with certain problems, having lived through treatment, and the social consequences of a condition or treatment (e.g. stigma) experienced (Baillergeau & Duyvendak, Citation2016). In addition, in the delivery of support it can help if someone has been through a similar transition (Suitor et al., Citation1995), such as that from ‘offender’ to ‘ex-offender’.

Although experiential peer support in criminal justice has been increasing, a clear empirical basis for its effectiveness is lacking. It is also unknown what mechanisms are crucial in experiential peer support. Previous research has mainly focused on support by experiential peers in other areas of care, such as for patients with chronic conditions (Thompson et al., Citation2022) and mental health care (Repper & Carter, Citation2011). A literature review on peer support in mental health services showed that empowerment, empathy and acceptance, stigma reduction and hope are important mechanisms (Repper & Carter, Citation2011). It is unclear to what extent these results can be generalised to the forensic setting. First, treatment or help in this field is usually mandated by court and thus involuntary, meaning that clients might not be motivated for treatment or behavioural change. Previous research has shown that establishing a treatment relationship in a mandated setting is difficult since tasks and goals are often predetermined and there is limited confidentiality (Bourgon & Guiterrez, Citation2013). Second, the stigma and misconceptions surrounding peer workers in mental health services (Perkins & Repper, Citation2013) may be even more present for ex-offenders in similar roles, which may influence successful implementation of experiential peer support. Third, the risk of deviancy training, which is the increase of problem behaviour that can occur when deviant peers are brought together (Dishion et al., Citation1999), needs to be taken into account.

A systematic review in the forensic context concluded that there is a lack of research about the impact of peer education in prison on mental health issues (Wright et al., Citation2011). The conclusion of another systematic review was that peer support services in prison can have a positive effect on recipients’ mental health. However, the authors also point to the poor methodological quality of most studies (South et al., Citation2014). Although these reviews provide us with some insight into whether experiential peer support works, most studies focus on improving prisoners’ health only. Settings of such interventions are, however, not restricted to prison, but also include forensic care settings and rehabilitation programmes. This is particularly the case for juveniles adjudicated by the juvenile justice system in which diversion plays a larger role. In addition, knowledge about what happens in the relationship between the experiential peer and the client is limited. Increasing knowledge about experiential peer support can contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms of desistance.

Experiential peer support is complex to evaluate, as it is not a standardised or protocolised intervention but a human relationship operating within a formal setting. It is insufficient to view this type of support as merely the contact between two people; in order to understand the relationship, we need to know what happens when a client and an experiential peer are brought together, and how this can lead to positive effects. We also need to know whether there are contextual factors, such as personal characteristics or setting conditions, that may influence the existence of these mechanisms or their effects on outcomes. A realist approach is suitable to study complex interventions and fits the explanatory purpose of the review. The realist approach is based on the idea that in order to be useful, evaluations should go beyond answering the question ‘Does it work?’ and indicate ‘what works, how, in which conditions and for whom’. A realist review starts with a programme theory, which is then refined on the basis of research studies. In assessing the effectiveness of an intervention, the explanations are usually formulated as context-mechanism-outcome configurations (Pawson et al., Citation2005). The mechanisms are not synonymous to the intervention components; as Wong and colleagues (Wong et al., Citation2013) describe, the way participants respond to the intervention, instead of the intervention itself, may trigger change. A realist approach therefore allows us to test several mechanisms through which the interactions between the client and the experiential peer might contribute to desistance. In this systematic realist literature review, we will investigate the effects of support by experiential peers on desistance from criminal behaviour, and the mechanisms and contextual factors that play a role in these types of interventions.

Programme theory

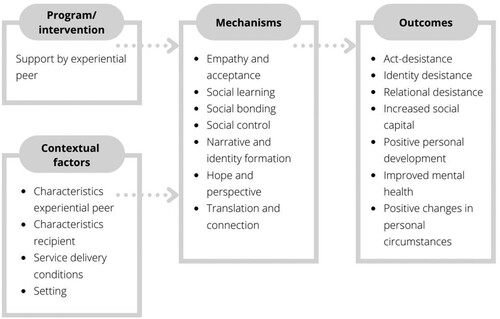

In this paper we test the initial programme theory regarding experiential peer support for people involved in criminal behaviour presented in our protocol paper (Lenkens et al., Citation2019b). In the following, we briefly describe the components (mechanisms, outcomes, contextual factors) of this theory. A graphic representation of this model can be found in .

Mechanisms

We propose several mechanisms that may play a role in the effects of experiential peer support on desistance-related outcomes. These mechanisms were based on interviews with experts and existing literature (Lenkens et al., Citation2019b). First, we proposed that experiential peers display empathy and acceptance. Second, the recipient may adopt new behaviours, attitudes, desires, and skills through social learning. Third, social bonding may take place with the experiential peer. Forth, the experiential peer may exert social control regarding the individual’s behaviour. Fifth, support by an experiential peer may help in the construction of a narrative and the formation of a new, alternative identity. Sixth, an experiential peer may instil hope in individuals with criminal behaviour or provide more perspective. Seventh, an experiential peer may translate and connect between the individual and other services and formal care providers.

Outcomes

The model includes three types of desistance: act-desistance (refraining from offending), identity desistance (internalisation of a new identity as a non-offender) and relational desistance (recognition of change by others). Other outcomes that may be achieved due to the support are increased social capital (social relationships of higher quality), positive personal development (e.g. self-efficacy, problem solving skills), improved mental health (decrease in symptomology) and positive changes in personal circumstances (e.g. employment, housing, school enrolment).

Contextual factors

Several contextual factors may influence the activation of the mechanisms. Characteristics of the individual receiving the intervention (age, severity of criminal behaviour, motivation) and the experiential peer (attitude towards criminality, specific experiences) may play a role. In addition, service delivery conditions may be important for implementation and acceptance of experiential peer support. The recruitment, training and support of experiential peers appears to be relevant. Lastly, the setting (e.g. prison, mental healthcare facility, community programme), including its function and security level, may moderate the effect of the intervention.

Method

Our realist review follows the process described by Pawson and colleagues (Citation2005). After identifying the review question, an initial theory was formulated that was described briefly in the introduction and more thoroughly in our protocol paper (Lenkens et al., Citation2019b). Our systematic realist literature review reported in line with the RAMESES publication standards (Wong et al., Citation2013).

Searching and selection of studies

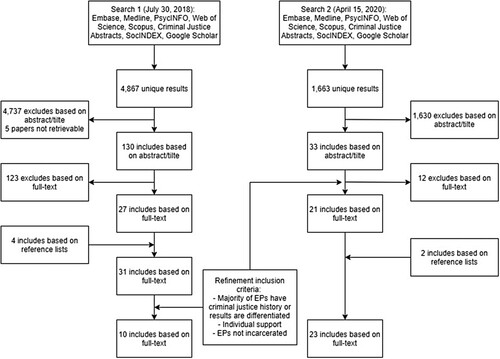

The initial systematic literature search was done on July 30, 2018, using multiple electronic databases: Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, Criminal Justice Abstracts, SocINDEX, and Google Scholar. The details of this search can be found in the protocol paper (Lenkens et al., Citation2019b), the complete strategy itself can be found in Appendix 1. This first search yielded 4867 unique results. All titles and abstracts were independently read and reviewed for inclusion by two researchers with a fast method using Endnote (Bramer et al., Citation2017), leading to 130 studies. After scanning and then reading the full articles that could be retrieved (all but five), this led to a selection of 27 papers and four additional papers from reference lists of included studies. After refining our inclusion criteria, which is not uncommon according to realist method (Pawson et al., Citation2005), 10 papers remained (see ). We conducted an updated second search on April 15th, 2020, using the same electronic databases. For this search we added several keywordsFootnote1 that we encountered while reading and evaluating the results from the first search. This search yielded 1663 new unique results. Following the same procedure as for the first search, this led to 33 additional included studies on the basis of title of abstract, of which 21 were eventually included based on the full-text article. Two additional papers were included based on reference lists of included studies, leading to a total of 23 included studies from the second search, and a final total of 33 papers (see ).

Table 1. In- and Exclusion Criteria.

Scope of the study

We included studies that examined individual, asymmetrical experiential peer support by and for individuals with criminal behaviour. The use of illicit drugs and sex work were not considered criminal behaviour in this study. Studies focusing on individuals displaying domestic abuse, intimate partner violence and/or driving under the influence offenses (DUI) were excluded. We did not have any restrictions based on methodology. An overview of our inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in .

Reading and evaluating literature

The research assistant and ML used a data extraction form to organise details of the literature (Appendix 2), including basic information about the paper, the aim of the study, and the methods used for collecting, recording, and analysing the data. We also described the size, composition, and selection of the sample. We registered information about the type of intervention (peer education, peer support, peer mentoring, bridging roles, other), whether it was the sole intervention or an element of a larger programme, the severity of criminal behaviour of both providers and recipients, and a description of experiential peers providing the intervention. The form also provided space for important limitations or other comments.

ML and GEN established the criteria for evaluating the studies (see Appendix 3). On the basis of the data extraction form, ML and GEN independently assessed the rigour and relevance (low, moderate, high). The rigour of studies was assessed based on participant selection, data collection, recording and analysis, sample size, and the description of the intervention and its providers. For qualitative papers, we additionally assessed the credibility of findings, referring to the extent to which claims and generalisations were supported by data and quotations (Green & Thorogood, Citation2014), and for quantitative papers we looked at study design and adjustment for confounders. The assessment of relevance included the question whether all providers and all recipients had been involved in criminal behaviour, whether the study focused on experiences and outcomes for recipients or providers, and whether experiential peer support was the only intervention (element) under investigation. ML and GEN’s independent assessments were combined and this file was returned to them, after which they could re-evaluate and/or explain their assessment. ML then evaluated the revised assessment and in most cases it was clear whose assessment was more substantiated. Elements of the assessment on which there was still no agreement were discussed by ML and GEN, until consensus was reached. Each paper was given a total score for rigour and relevance (see Appendix 4).

ML coded the results of the articles from the first search using the software programme NVivo, using both deductive and inductive coding. The deductive codes were based on the initial programme theory and therefore included codes for the seven proposed mechanisms, codes for the seven types of outcomes and codes for seven contextual factors (characteristics recipient, characteristics/prerequisites experiential peer, setting, support by organisation and staff, recruitment/training/supervision/monitoring, timing/duration/frequency/intensity, service delivery conditions). Based on the data, we added codes for new mechanisms and outcomes, and for several (organisational, security and personal) challenges that may be present in experiential peer support interventions. These results were transferred to an Excel file. For the results of the second search, results for mechanisms, outcomes and contextual factors were directly organised into an Excel file. For three papers (10%), a second researcher (GEN) independently coded the results regarding mechanisms, outcomes and contextual factors. ML and GEN then discussed their findings and agreed that ML was well equipped to do the further coding of the papers, also because of her familiarity with the themes, which had been central to an interview study she conducted (Lenkens et al., Citation2020).

Changes compared to protocol paper

We excluded papers that concerned domestic abuse, intimate partner violence and/or DUI-offenses, although the type of criminal behaviour was not always reported in articles. We were not able to only select studies in which the recipients of the experiential peer support were below the age of 30 years. Most studies were conducted with an adult population, and there were studies in which no information on age was given for the study sample. As an additional criterion, we only included studies in which the majority of those designated as ‘peer mentors’ or ‘peer supporters’ in the sample had a criminal justice history or in which results were differentiated for those with and without a criminal justice history, since we were mostly interested in experiential peer support in this population.

Results

Rigour and relevance assessment

The rigour and relevance assessment form was not suitable for seven (included) papers due to their study designs. The first paper was based on an expert symposium where positive and negative effects of peer interventions in prison were discussed (Woodall et al., Citation2015). Although these expert opinions were not substantiated by data and there is little information on the specific interventions, we considered this paper to be highly valuable due to the large sample (n = 54) of experts. The second paper concerned a social return on investment (SROI) study of a peer mentoring intervention that measured primarily its financial gains, but did, for instance, not include a sample of participants (Jardine & Whyte, Citation2013). We decided to still include the study because it reported on clients being returned to custody, which is linked to the outcome of act-desistance (Jardine & Whyte, Citation2013). The other five papers reported on an ethnographic study consisting of interviews, observations and documentary analysis in which multiple peer mentoring projects were investigated (Buck, Citation2014; Buck, Citation2017; Buck, Citation2018; Buck, Citation2019a; Buck, Citation2019b). Not all mentoring projects in this study worked solely with experiential peers and mentees with a criminal background. We classified this study as valuable and relevant due to the broad sample of projects and in-depth reflection on the data.

Our rigour assessment of the other 26 papers led to an initial 88% agreement and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.83, indicating strong agreement following McHugh’s (Citation2012) suggested interpretation. Most initial disagreement regarding the rigour of quantitative papers concerned how complete the description of experiential peers was, for instance regarding their lived experiences and whether they had received training for their role as EP (for three papers) (Bellamy et al., Citation2019; Cos et al., Citation2020; Lopez-Humphreys & Teater, Citation2020). Regarding the qualitative papers there was more disagreement. For four papers (Adams & Lincoln, Citation2020; Harrod, Citation2019; Nixon, Citation2020; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019), ML and GEN disagreed in their initial assessment of how elaborate the selection of participants was described. For the description of experiential peers in the study, there were four qualitative papers (James & Harvey, Citation2015; Lopez-Humphreys & Teater, Citation2019; Portillo et al., Citation2017; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019) for which ML and GEN disagreed in their initial assessment, with ML rating the description as lower than GEN in three papers. For the aspect of data collection and recording, they disagreed in their assessment of three papers (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Schinkel & Whyte, Citation2012). In the latter case, ML rated this aspect lower than GEN in all three instances. In total, eight full papers and the quantitative parts of two papers were assessed as having a low rigour, eleven full papers and the qualitative parts of two papers were assessed as having moderate rigour, and five papers were assessed as having high rigour (see Appendix 4). The eight full papers with low rigour were excluded from further analyses.

We assessed the relevance to the realist review of the remaining 18 papers (sixteen full papers and the qualitative part of two papers), leading to an initial 78% agreement and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.77, indicating moderate agreement (McHugh, Citation2012). Three papers were assessed as having a low relevance because they focused on experiential peers’ own work experiences (Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Barrenger et al., Citation2019) and on a job training programme in which not all providers and recipients had a criminal justice history (Matthews et al., Citation2019). These papers are not necessarily less relevant for the field of experiential peer support, but the lower scores indicate that these studies are less likely to contribute to our research question. We did not exclude papers with a low relevance score but took this score into account in analysing and discussing the results. Six and nine papers were rated as respectively having a moderate and high relevance.

Characteristics of included studies

An overview of the characteristics of the 25 included papers is given in , with information about papers describing the same study grouped together. Of all 19 studies, fifteen used qualitative methods, three used quantitative methods and one study was a social return on investment study (SROI). Twelve studies were conducted in the United States and seven in the United Kingdom. The interventions took place at (multiple) organisations or mentoring settings in the community (n = 6), (partially) in jail, prison, or other correctional facility (n = 5), at a residential drug treatment programme (n = 1), at a care clinic or health centre (n = 2), at a job training programme (n = 1), at a social enterprise (n = 1). For thirteen studies, it was explicitly mentioned that experiential peers involved in the intervention had received a training. Study participants were clients (n = 5), EPs (n = 4), a combination of EPs and clients (n = 2), EPs and staff (n = 2), clients and staff (n = 1) and clients, EPs, and staff (n = 2).

Table 2. Characteristics Included Studies.

In the following, studies will only be discussed if a certain mechanism, outcome, or contextual factor was mentioned. The terminology for EPs (e.g. peer mentor, peer navigator, peer coach) and clients (e.g. students, mentees) varies (see ). For consistency reasons, we use the terms ‘experiential peer’ (EP) for the provider and ‘client’ for the recipient of the support.

Mechanisms

The included studies provided empirical support for the proposed mechanisms. An overview of the mechanisms and how they are present in the studies can be found in .

Table 3. Main Findings with Regard to Mechanisms.

Empathy and acceptance

The results of eleven qualitative papers indicated that empathy and acceptance is important in the relationship between EPs and clients. In a study about the potential of experiential peer support, a professional described that EPs may have more understanding and empathy, and several youths mentioned that those with experiential knowledge may be better able to understand them or relate to them (Creaney, Citation2018). Empathy may be easier for individuals who understand the ‘woundedness’ of others (Nixon, Citation2020). In a qualitative study, EPs indicated that they have a deeper and empathic understanding of clients’ situations (Barrenger et al., Citation2019) and a more true understanding of the pain and isolation that clients experience, because of their own similar experiences (Barrenger et al., Citation2017). In a study among women re-entering society, clients indicated that they experience support and that the EP makes them feel comfortable and understood (Thomas et al., Citation2019). Finally, in a qualitative study focused on the impact of experiential peer support on the mentors, an EP said to have learned to be empathic and put themselves in someone else’s shoes, and to be open and receptive to everyone (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013).

In addition to being understood, the non-judgmental approach of EPs is a prominent theme. In a study at a social enterprise, both employees (clients) and EPs favoured such an approach by EPs. One EP mentioned that EPs do not judge clients, no matter ‘how horrible their past was’ (Harrod, Citation2019). A client in another study described the EP who had supported him as able to empathise and as non-judgmental. An EP also expressed ‘Who am I to judge?’, suggesting that not all EPs felt they were in a position to judge the client (Creaney, Citation2018). EPs saw themselves as more tolerant than other professionals (Barrenger et al., Citation2019) and, by refraining from judgment, offer clients space to share thoughts and experiences they do not share with other professionals (Barrenger et al., Citation2017). Clients also viewed EPs as non-judgmental (Thomas et al., Citation2019) and in a study of a job training programme, a quarter of clients felt they would be understood and not judged by EPs, thereby making it easier to talk to them and ask for help (Matthews et al., Citation2019). This was also found in a large qualitative study investigating four different peer mentoring interventions, in which clients experienced a sense of being openly accepted instead of being judged. EPs were perceived to be free of judgments since they had experienced judgments themselves, and understanding and judgment were considered incompatible by clients (Buck, Citation2018). It was also mentioned that clients articulated a desire to explore experiences without having to fear judgment or adverse consequences (Buck, Citation2019a). Finally, in a mixed-method study with semi-structured interviews, one client indicated to feel comfortable and accepted because his peer mentor helps him without demanding anything (Marlow et al., Citation2015).

In sum, these studies indicated that clients tend to feel comfortable and understood by EPs, who feel they have a more profound understanding of clients’ struggles. In addition, both clients and EPs considered EPs to have a non-judgmental approach, which creates space to share experiences and thoughts that are not easily discussed with other professionals.

Social learning

Nine qualitative papers reported results suggesting social learning as a mechanism of experiential peer support, mostly referring to EPs as role models. In a study with interviews, observations, and focus groups, clients spoke about the peer advocates as role models of what someone with a mental illness diagnosis and a criminal justice record can do to successfully re-enter the community (Portillo et al., Citation2017). In a study where EPs were interviewed, it was found that EPs realise that they can be a role model for others (Barrenger et al., Citation2017) and that they share their experiences so that others can learn from their mistakes (Barrenger et al., Citation2019). In another study, clients stated that they can learn from EPs’ experiences, and throughout the programme, more clients started to see EPs as role models. EPs mentioned that they mentor clients by being an example and modelling appropriate workplace behaviours. One client described that certain behaviour of EPs could be transferred to clients and mimicked by them (Harrod, Citation2019). A study found through semi-structured interviews that peer mentors modelled recovery habits, interpersonal skills, and effective coping (Marlow et al., Citation2015). Studies mentioned that clients are sometimes inspired to volunteer and become EPs too (Buck, Citation2017; Creaney, Citation2018; Nixon, Citation2020). Studies suggested that EPs’ history of criminal behaviour leads to more respect (Harrod, Citation2019) and that EPs’ lived experiences can contribute to their credibility (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). However, another study mentioned that EPs were sometimes described as inauthentic role models, because clients knew them from their previous lives as individuals involved in offending (Buck, Citation2017).

In conclusion, a few studies indicated that EPs consider themselves as role models who share experiences to enable clients to learn from their mistakes, but also to set an example of how to re-enter the community successfully. In several studies, clients shared this perception of EPs as role models. Based on the aforementioned literature, it is, however, unclear whether EPs’ experiences with criminal behaviour and the criminal justice system also contribute to making them more credible in the eyes of clients.

Social bonding

Ten qualitative papers addressed the quality of the relationship between EPs and clients. In a study in which mentors were interviewed, a mentor mentioned that the relationship between client and mentor is essential. Participants emphasised how the success they achieve with their clients reflects the type of relationship they have with them (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013). EPs indicated that connecting with clients is the main focus of their support (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019), and felt they add trust, care and commitment, which according to them is often lacking in relations with professional caregivers (Barrenger et al., Citation2017). In addition, they felt that treating clients like people is important to connect with them (Barrenger et al., Citation2019). In a qualitative study in which re-entering women were interviewed, participants indicated that they felt cared for and understood by the staff, which contributed significantly to their satisfaction with the programme (Thomas et al., Citation2019).

Studies found that both clients (Creaney, Citation2018; Harrod, Citation2019; Matthews et al., Citation2019) and EPs (Barrenger et al., Citation2017) felt they can relate to one another more authentically and easily, that a shared identity of ‘criminal justice system survivor’ strengthens their bond (Portillo et al., Citation2017), and that EPs’ lived experiences are instrumental in building rapport with clients who otherwise do not ask for help (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). EPs felt that their own criminal background has a positive effect on the dynamics of the relationship and enables them to work more effectively with clients. They emphasised that the success of the programme was related to this (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013). Many clients look for advice and answers in their conversations with EPs, which gives EPs an opportunity to show their support. Talking to EPs about personal issues was mentioned more often in initial interviews than in follow-up interviews with clients. EPs mentioned that one should not force clients to open up, but instead get to know them so this occurs naturally (Harrod, Citation2019).

Several studies emphasised trust as essential to the relationship. EPs indicated that gaining mentees’ trust and maintaining confidentiality is essential for clients to open up and deal with deeply rooted issues (Matthews et al., Citation2019) and for EPs to support them (Harrod, Citation2019; Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013). Building trust seems particularly important for the target population, who sometimes have trauma histories and difficulties with emotional regulation (Thomas et al., Citation2019) and have lacked supportive relationships, making them prone to be self-reliant in solving their problems (Matthews et al., Citation2019). Several studies suggested that identifying as a peer and having a shared history generate trust (Barrenger et al., Citation2019; Matthews et al., Citation2019). One youngster spoke about the trusted relationship he had developed with an EP and referred to their shared experiences as a reason (Creaney, Citation2018). Several clients of another programme indicated that the staff (including EPs) was reliable and trustworthy (Matthews et al., Citation2019). In another study, EPs were perceived as friends rather than authority figures. In such a relationship based upon collaborative ideals, there is potentially more space for trusting and open exchanges (Buck, Citation2019a).

In short, several studies described the relationship or connection between EPs and clients, which according to some studies is more easily made due to their shared identity. Trust is often mentioned as an essential component of the relationship. EPs indicate that it is essential to gain clients’ trust to support them, and feel like clients generally trust them.

Social control

Seven qualitative studies mentioned elements of social control. In two studies, it was mentioned that corrections or negative feedback are more easily accepted by clients when coming from EPs, who once struggled with similar problems (Buck, Citation2018; Matthews et al., Citation2019). It was suggested that recovery is related to feeling cared for, but also with a need for somebody who drills things into you (Buck, Citation2018) and clients accepted the necessity of being corrected (Matthews et al., Citation2019). Some clients even desire to be held accountable and corrected, although this should not entail yelling or belittling (Harrod, Citation2019). EPs in this study indicated that their mentor role includes making corrections, to prepare clients for other jobs but also to deal with difficult clients, although one EP warned about using scorn and some clients indicated being berated by EPs (Harrod, Citation2019). Another study described that several women felt controlled by staff, including EPs (Thomas et al., Citation2019). Yet, another study indicated that EPs saw themselves as nondirective; instead of trying to influence clients’ behaviour directly, they provide a space for clients to fail or succeed on their own terms (Barrenger et al., Citation2019). This leeway was also described in a large study, where both mentors and mentees said it is important to not over-react to mistakes, since relapses are likely and part of change. Mentors seemed to strive for such support and tolerance in their work (Buck, Citation2018). In another paper, the same author concluded that there is a desire for a relationship in which personal experiences can be explored with less consequences (Buck, Citation2019a). Finally, EPs in one study indicated that it is less likely that clients will fabricate information or push them too far, since they realise the EP will notice this (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013).

Regarding this mechanism, we conclude that there is not a clear pattern for the presence of social control, the process by which the EP (in)directly tries to influence the client’s deviant behaviour. Although several studies indicated that corrections may be necessary and that they might be easier for clients to accept coming from EPs, EPs themselves tend to see themselves as nondirective and not react too strongly to mistakes.

Narrative and identity formation

The result of one study is that two young participants in the music project performed a song, thereby practicing their new identities as ‘performers’, and were praised for their prosocial behaviour (Creaney, Citation2018). Another study described that making a transition from ‘offender’ to ‘ex-offender’ can elicit feelings of losing a known reality. EPs can then provide reassurance as they have already completed this change successfully (Buck, Citation2019a). Although these studies provided some indication for this mechanism, there is not enough empirical support to include it in the model.

Hope and perspective

Eleven papers found that EPs are a source of hope and perspective for clients. One EP emphasised the importance of imparting hope in youngsters and showing that change is feasible (Creaney, Citation2018). In another study, it was found that EPs demonstrate that change is possible (Buck, Citation2017) and can be coped with (Buck, Citation2019a), and that EPs provide a powerful source of inspiration (Buck, Citation2014). The author suggested that the image of ‘ex-offender’ symbolises new possibilities (Buck, Citation2014) and that seeing someone similar to you making this change can offer a sense of security (Buck, Citation2019a); EPs offer a template of a future life that appears attainable regardless of problematic histories (Buck, Citation2017). One peer mentor who had been incarcerated for a long time indicated that small changes give participants a bit of hope for the future because he was the same (Buck, Citation2018). Both EPs (Barrenger et al., Citation2019; Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Nixon, Citation2020) and clients (Marlow et al., Citation2015; Matthews et al., Citation2019; Portillo et al., Citation2017) felt that seeing someone succeed despite challenging circumstances is inspirational and provides hope for clients’ own future. Several EPs said that in particular those EPs who had been incarcerated can be inspirational, and that simply having a job as an ‘ex-offender’ is already an inspiration for clients (Barrenger et al., Citation2019).

These studies indicated that EPs can inspire clients and stimulate a sense of hope in them, since they embody the idea that change is possible. This was supported by statements of both EPs and clients and was described by several authors as an important theme.

Translation and connection

Nine studies described results related to this mechanism. In one study, peer mentors mentioned their value as a bridge between young people and staff (Hodgson et al., Citation2019). In another qualitative study, clients described this role of the EP as ‘resource broker’; peer navigators connect clients to other service providers, organisations and agencies (Portillo et al., Citation2017). EPs saw themselves as an intermediary between clients and other professionals (Barrenger et al., Citation2019) and draw on their experiences with navigating the system to help their clients (Barrenger et al., Citation2017). EPs’ knowledge of community resources helps them to refer re-entering women to necessary medical health care services. Clients indicated that EPs’ clear language helps them in understanding their health situation (Thomas et al., Citation2019). One study described this mechanism as an indirect way to address recidivism. Instead of concentrating directly on recidivism or rearrest, EPs in this intervention are focused on ensuring that clients’ treatment, housing, employment, and income needs are met. They help clients with identifying appropriate employment opportunities, but also assist them in transportation needs (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). In another study, clients mentioned several problems with which staff has helped them, such as getting an ID and getting into a better housing situation (Matthews et al., Citation2019). Another study mentioned that EPs refer participants to other services, mostly related to housing, drug and alcohol treatment, mental health services, education, employment and identification (Marlow et al., Citation2015). EPs refer clients to other services or resources for housing, education, finances, employment, mental health needs and legal issues, and one EP emphasised how important this is since clients also face challenges that cannot be fixed by only having conversations (Harrod, Citation2019). These studies indicated that connecting clients to services, in particular housing, employment, or schooling services, is one of the mechanisms in experiential peer support.

Additional mechanism: recovery perspective

Several studies (Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Barrenger et al., Citation2019; Buck, Citation2017; Buck, Citation2018; Cos et al., Citation2020; Harrod, Citation2019; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019; Thomas et al., Citation2019) described aspects of experiential peer support that cannot be categorised into one of the proposed mechanisms of the initial programme theory. This additional mechanism is best described as a recovery perspective on criminal behaviour and desistance. Desistance is conceptualised as a complex, non-linear process, and criminal behaviour is not seen as a demarcated problem that can be easily fixed by an external actor. Instead, the individual is considered as a whole person who is the owner of their own life, emphasising the important role that agency and empowerment play in this perspective on desistance.

Studies showed that a certain view on desistance plays a role in the support that experiential peers provide. In these studies, desistance was seen as a complex, non-linear process in which mistakes and second chances are considered normal (Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Barrenger et al., Citation2019; Buck, Citation2018; Harrod, Citation2019). EPs mentioned that they are able to sense when the time is right for a client to be discharged and that there is no universal timeline for this (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). A nondirective approach was considered important, which mainly originates in respondents’ own experiences with criminal behaviour and desistance (Barrenger et al., Citation2019). They described that it is essential to not over-react to slip-ups and they aim for an open dialogue instead of interpreting them as risks (Buck, Citation2018), and one EP said that it is useless to try to persuade clients (Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Barrenger et al., Citation2019). In another study, very few EPs mentioned recidivism prevention when asked about their activities with clients; EPs seemed less concerned with the ultimate outcome of rearrest, focusing instead on connecting with clients and ensuring treatment and housing needs are met (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). EPs understand the benefits of remaining supportive, while being careful not to support criminal offending (Barrenger et al., Citation2019). This is in contrast with approaches that directly confront criminality (Barrenger et al., Citation2019), or, as described by one EP, the punitive care system, that does not recognise clients as human beings who make mistakes (Barrenger et al., Citation2017). Respondents described their suffering as relating to ‘recovery’ (Buck, Citation2018) and motivating patients to adhere to their personal recovery goals was considered a main task of EPs (Cos et al., Citation2020).

In addition, respecting agency and stimulating empowerment were described as important elements in experiential peer support. Individuals involved in offending start seeing themselves as having agency, even in difficult situations, and become co-authors of their own lives (Buck, Citation2018). It seems important for both EPs and clients that they feel they own the decision and the desire to change. It cannot belong to the person that intervenes or inspires them; the client needs to be independently ready to change, and inspirational role models only serve to motivate this change, not to initiate it (Buck, Citation2017). This idea of agency was also visible in two studies in which EPs were interviewed. Rather than telling clients what to do and trying to influence them, EPs give them space to fail or succeed on their own terms, thereby empowering them to make their own choices and enhancing self-determination and self-efficacy (Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Barrenger et al., Citation2019). Creating an environment that fosters empowerment can be done, according to EPs, by complimenting clients, showing appreciation, and trying to motivate and inspire them (Harrod, Citation2019). Women in another study indicated that the staff helps them understand their needs and respected specific treatment preferences of their clients, placing an emphasis on both competence and autonomy (Thomas et al., Citation2019). These studies suggested that an additional mechanism may be at play in experiential peer support; a recovery-oriented attitude of EPs towards criminal behaviour and desistance.

Outcomes

The included studies provided empirical support for several proposed outcomes. An overview of these outcomes and how they present in each study can be found in . For several outcomes we found little to no evidence. In the following, we describe the results and also discuss the inconsistencies found in the literature. We did not find any results for identity desistance and relational desistance.

Table 4. Main Findings with Regard to Outcomes.

Act-desistance

Seven papers reported information on criminal behaviour after the intervention of experiential peer support. In one randomised Controlled Trial (RCT), in which the intensity of peer coaching differed across treatment levels, no significant group differences were found in rearrest or reincarceration rates (Nyamathi et al., Citation2016). A pilot RCT study, however, found that a significantly smaller proportion of participants who received peer mentoring violated parole compared to those who did not (Sells et al., Citation2020). A one-group pretest posttest study showed a decrease in criminal behaviour, but an increase in days in jail or prison (Cos et al., Citation2020). According to a study set at a job training programme, internal data indicated that continuing the relationship with an EP at least two years after graduation reduced clients’ likelihood of reoffending by 90% (Matthews et al., Citation2019). A qualitative study at a social enterprise found that the dialog between EPs and clients seems to at least sometimes prevent recidivism (Harrod, Citation2019). Lastly, in a study investigating the social return on investment of a peer mentoring intervention, it was found that there was no significant difference in being returned to custody between those who did and those who did not have a mentor (Jardine & Whyte, Citation2013). Based on these studies and taking into account the different designs of these studies, we do not have sufficient evidence to conclude that support by EPs decreases recidivism.

Positive personal development

Three studies reported results on outcomes relating to positive personal development. In a qualitative study among re-entering women, it was found that staff provided autonomy support, which stimulated motivation and navigation skills and enabled participants to work towards personal goals such as quitting smoking and maintaining sobriety. Many participants in this study described attitudinal and behavioural transformations (Thomas et al., Citation2019). A study examining a job training programme indicated that staff helped clients gain self-esteem by having confidence in them first. In addition, clients learned how to persist, how to cope with failing and how to avoid risky situations (Matthews et al., Citation2019). A final study suggested that peer mentoring encouraged self-esteem and coping mechanisms (Marlow et al., Citation2015).

These studies suggested that experiential peer support may contribute to positive personal development, which encompasses self-esteem and skills regarding coping and problem solving. It should be noted that the intervention in two of three studies entailed more than experiential peer support, indicating that other programme elements may also account for any positive changes. More research is necessary to investigate this potential outcome.

Improved mental health

Four papers reported on mental health, mainly discussing participants’ substance use. An RCT reported in two papers showed an overall reduction of drug use among participants, but this was not significantly associated with receiving support from an EP (Nyamathi et al., Citation2016; Nyamathi et al., Citation2016). A study without control group, also demonstrated a significant reduction in individuals’ recent substance abuse. In addition, participants showed reduced depression and anxiety symptoms (Cos et al., Citation2020). Another study mentioned that seven participants experienced a drug relapse in the first month of the intervention. However, the authors indicate that these participants were in residential substance abuse, and that this high relapse may therefore suggest more about the persistence of substance use disorders than represent a negative result of peer mentoring (Marlow et al., Citation2015). Although these studies indicated that substance use decreased, we do not have sufficient evidence to determine the exact contribution of experiential peer support for improvement in mental health.

Positive changes in personal circumstances

Six studies gave information on participants’ situation regarding schooling, housing, or employment after the intervention. An RCT demonstrated that there were no differences between treatment conditions regarding employment status (Nyamathi et al., Citation2016). A study without control group, however, showed that there was an increasing trend for school enrolment among participants and a significant increase in employment and monthly income during the programme (Cos et al., Citation2020). In a qualitative study clients talked about how staff had helped them with getting an identification card or finding better housing (Matthews et al., Citation2019) and one EP indicated that EPs were helping participants back into employment (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013). No other studies gave information about changes in housing situation for clients. One study, however, did provide a potential explanation. Finding suitable housing, although a priority, was a major challenge, as re-entering individuals are not seen as homeless and therefore have to wait to be eligible for housing. EPs also struggled to ensure that any employment of the client met certain standards and was not a risk for relapse (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). Participants in one study stressed the importance of the programme to their stability in the community and mentioned how their mentor had helped them find critical resources (Marlow et al., Citation2015). The evidence base for positive changes in personal circumstances is unclear; although several studies gave some indications for positive outcomes relating to school enrolment and employment, this was not corroborated by rigorous quantitative findings.

Increased social capital

No studies suggested that receiving experiential peer support leads to an improvement of one’s social network or social capital outside of the bond with the experiential peer. EPs indicated that improving clients’ social support is challenging since friends and family members can be triggers for offending and substance use (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019).

Other outcomes

Several papers reported other outcomes for recipients of support by EPs. An RCT demonstrated overall improvement in health, but no significant differences between groups. The authors concluded that the treatment level without peer coaching is less costly, and similarly effective (Nyamathi et al., Citation2016). Clients in another study displayed increased behavioural health access and utilisation (Cos et al., Citation2020). A final study suggested that referral by an EP makes it more likely that a client will utilise these services (Harrod, Citation2019).

Contextual factors

The amount of information about the characteristics of EPs and clients involved in the intervention (age, gender, ethnicity, criminal background, educational level, etc.) was limited in the included studies. Information about the peer support interventions (content, frequency and intensity of support, protocol, timing) and treatment fidelity was largely lacking. In addition, for most studies we do not know whether the support provided by the EP was the sole intervention for recipients or whether they received other types of support or treatment.

Most papers did indicate whether EPs had completed a training, although this varied from a brief mention to elaborate descriptions of the training. In most studies, EPs were trained, ranging between a training of several days with monthly meetings to a five-month training including an internship. These trainings were aimed at enhancing professional skills, including services navigation, (Buck, Citation2019b; Nyamathi et al., Citation2016; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019; Sells et al., Citation2020; Thomas et al., Citation2019), recovery-supporting interventions (Buck, Citation2019b; Cos et al., Citation2020; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019), interpersonal and communication skills (Buck, Citation2019b; Cos et al., Citation2020; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019; Sells et al., Citation2020), and problem-solving skills (Buck, Citation2019b; Nyamathi et al., Citation2016). Although this suggests that training and supervision are considered important to provide experiential peer support, we did not find any differences in mechanisms or outcomes between studies in which EPs had received training specifically aimed at providing peer support and studies in which they (seemingly) had not (Matthews et al., Citation2019; Portillo et al., Citation2017).

Looking at the setting of the intervention (prison/jail vs. after release), we also did not find any differences in mechanisms and outcomes. Some studies suggested that the delivery of the intervention, and thereby possibly the setting, plays a role in its effectiveness (Harrod, Citation2019; Matthews et al., Citation2019; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). In one study, EPs indicated that they would like to work with clients for a year or more, instead of the average of eight or nine months, as they estimated that it takes up to a year for clients to become independent and their role becomes more challenging as clients become more drawn to old friends using drugs (Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). Another study found no effect of timing of first contact or number of contacts on parole outcomes (Sells et al., Citation2020). A final study described that internal data showed that maintaining the client-EP relationship for at least two years after clients’ graduation reduced their likelihood of recidivism by 90% (Matthews et al., Citation2019). However, these data were not controlled for confounding variables. EPs working with clients in a social enterprise indicated that their daily presence, working alongside clients, benefits their relationship (Harrod, Citation2019). Unfortunately, as information about delivery (frequency, intensity, duration, timing) was lacking in most studies, it is impossible to determine whether these aspects influence the mechanisms and outcomes. In conclusion, the information on contextual factors provided in the included studies was limited and does not allow us to determine their importance to the triggering of mechanisms.

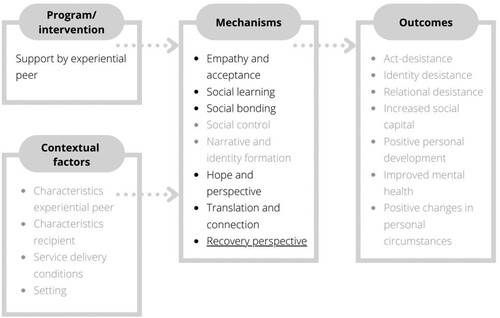

The findings of our realist review result in a revised model of the programme theory as presented in . In this figure, the mechanisms, outcomes and contextual factors for which we did not find sufficient evidence are displayed in grey. The dotted arrows between mechanisms, outcomes and contextual factors indicate that we have not been able to establish causal links between these elements.

Discussion

In this systematic realist literature review, we found evidence that experiential peers show empathy and have a non-judgmental approach, are considered role models, establish a trusting relationship with clients, offer hope, and connect clients to other services. We did not find enough evidence that points to the relevance of narrative and identity formation as a mechanism in experiential peer support. Contrary to what we hypothesised, EPs do not seem to exert much social control. Several studies in our review provide reason to consider a recovery perspective on criminal behaviour and desistance as an additional mechanism. Within this perspective, EPs aim to empower clients and emphasise their agency, see desistance as a non-linear pattern involving mistakes and relapses, and use a strengths-based approach. We did not find studies that specifically tested these factors as mediators of experiential peer support contributing to certain outcomes. We can therefore only conclude that they seem important components of experiential peer support, and not that they are (causally) related to achieving positive outcomes.

Our results do not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that experiential peer support leads to the hypothesised outcomes. There are some indications for the outcomes act-desistance, positive personal development, an improvement in mental health, and positive changes in personal circumstances, but the study designs do not allow us to draw the conclusion that these effects are due to the support provided by EPs and study results were not consistent. We found no results for the outcomes identity and relational desistance.

The information regarding contextual factors that might influence the instigation of mechanisms was too limited for a robust analysis. This means that we do not know whether certain mechanisms are more likely in specific settings or for specific people, or whether certain outcomes are more likely under specific circumstances.

The results of our study raise the question whether we are measuring the right variables, given the type of intervention. First, several elements proposed as mechanisms may also be considered important outcomes, such as increased hope and feeling understood and accepted. From a security perspective, non-recidivism is the primary goal of support for individuals involved in offending. However, from a care perspective, transformations in areas such as hope and self-esteem are in itself important to clients’ quality of life. This is in line with ‘positive criminology’, which centres around strengthening individual resilience and talents, instead of merely looking at criminal behaviour and risk factors (Ronel & Elisha, Citation2011; Ronel & Segev, Citation2014). Studies mainly focusing on desistance run the risk of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Second, we did not find studies that measure long term effects of experiential peer support. As described in several studies, desistance is a complex and non-linear process for which the individual needs to be ready. In our previous qualitative study, EPs indicated that they aim to ‘plant a seed’ in the client’s mind, but that it can take up to years before someone is able to internalise earlier lessons learned (Lenkens et al., Citation2020). Studies that only measure short-term effects thus potentially miss positive effects of experiential peer support that take longer to develop. Finally, several elements may be influenced by experiential peer support but may be difficult to measure, such as the mechanism narrative and identity formation and the outcomes identity and relational desistance. This also reflects the more general difficulty of evaluating experiential peer support. Although the majority of qualitative studies included in our review provided us with a richness of data and insights, the quantitative studies were not able to contribute significantly to the programme theory. This suggests that experiential peer support is too complex to be evaluated through conventional methods such as RCTs. Experiential peer support should not be understood as a specific event or a demarcated intervention, but rather conceptualised as a complex system. As the guidelines of the UK’s Medical Research Council suggest, evaluation of complex interventions goes beyond asking whether an intervention achieves its intended outcome. A programme theory that describes the mechanisms of the intervention and how the intervention interacts with the context in which it is implemented is considered a core element (Skivington et al., Citation2021). We tackled this in our literature review by using a realist methodological approach, and suggest that individual quantitative studies also take into account contextual factors and mechanisms when evaluating outcomes of experiential peer support.

Although our realist review is focused on outcomes for recipients of experiential peer support, it is important to note that experiential peers may also benefit from their role as EP. It gives them a purpose and an opportunity to contribute to society (Adams & Lincoln, Citation2020; Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Nixon, Citation2020), contributes to their financial independence (Adams & Lincoln, Citation2020; Barrenger et al., Citation2017), increases their self-esteem and (communication) skills (Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Woodall et al., Citation2015) and contributes to their empowerment (Buck, Citation2018; Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Woodall et al., Citation2015) and recovery (Adams & Lincoln, Citation2020; Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2019). This suggests that, even if research cannot unequivocally demonstrate positive (behavioural) outcomes for recipients, experiential peer support may still be promoted for the effects on providers’ recovery process. Of course, experiential peer support can then only be recommended if clients appreciate the support and if there are no risks involved for them, which should be further investigated.

Strengths and limitations

The current systematic realist literature review contributes to our knowledge of experiential peer support for individuals with criminal behaviour. The realist approach allowed us to test an elaborate model of mechanisms, outcomes, and contextual factors. The included studies represent a variety of experiential peer support interventions, in a broad range of settings. In addition, mechanisms and outcomes were described from several perspectives, mainly those of EPs and clients. This review, however, also has several limitations.

Our inclusion criteria limit the review’s generalizability. We only included studies published in English journals, resulting in a sample of studies from the US and the UK, which are both high-income countries. For feasibility reasons, we excluded grey literature which may have given us more insight into the inner workings of EPS interventions. Lastly, we only looked at interventions with an asymmetrical relationship between EP (provider) and client (recipient), meaning that our results cannot be generalised to mutual support interventions.

In most studies it was unclear whether clients received additional support or treatment, and what this entailed. This seems inherent to peer mentoring, which is often a complementary source of support, but makes it difficult to attribute any effects or even mechanisms to the support by the EP. This attribution paradox is more common in a realistic approach to evaluation, which is fit to assess complex interventions but also needs to confront multi-causality. This makes it virtually impossible to assess how one practice or a set of practices, in this case the support by the EP, contributes to the outcomes (Marchal et al., Citation2010). Similarly, not all providers and recipients of the interventions investigated had a criminal background, which means that we cannot know with certainty that having these particular experiences makes a difference.

It is crucial to note that the design of most studies does not allow us to falsify our initial programme theory, in particular regarding the proposed mechanisms. Most studies have investigated experiential peer support in an explorative fashion instead of testing the presence or absence of specific mechanisms. Researchers have reported their results accordingly, thus only providing positive evidence for mechanisms. This means that studies where participants mention ‘empathy’ as a key element will report this finding, but that we cannot conclude that this is not a key element of interventions in studies that do not report information about empathy. We can therefore discuss the amount of evidence for mechanisms, but we cannot with certainty eliminate mechanisms that are not mentioned in the studies.

Finally, the proposed model is perhaps more ‘artificial’ than the type of interventions studied allows for. Mechanisms may influence each other, and outcomes may also influence mechanisms. It should be noted, however, that research into these types of interventions is quite complex and that the insights that we gathered through our review form a valuable basis upon which knowledge can be further expanded.

Implications for research and practice

Future research should systematically investigate mechanisms of experiential peer support and their effects on outcomes for recipients of such support. Qualitative research examining the mechanisms for which we did not find enough evidence can help to unravel their importance to the programme theory. In addition, qualitative studies should be used to increase our knowledge of outcomes of experiential peer support from a client perspective. Longitudinal (quantitative and qualitative) quasi-experimental methods can then be used to measure differences in pre- and post-intervention variables and compare results to a comparison group receiving support from professional care providers without similar lived experiences. In conducting such research, we should not only look at more objective measures, such as absence of criminal behaviour and other indicators of stability in the community (e.g. employment), but also take into account ‘softer’ outcome measures, such as hope, self-esteem, and attitudes towards criminal behaviour and desistance. Additionally, it is important to investigate the development of the working alliance between clients and EPs, since a strong alliance is important for achieving positive outcomes (Flückiger et al., Citation2018; Shirk & Karver, Citation2003). In order to increase our knowledge on what works for whom under what circumstances, it is crucial that future research gathers and provides more information on contextual factors, such as characteristics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, criminal history) of clients and EPs, and delivery and fidelity of the intervention. More research investigating the role of formal training for EPs is also recommended, as there may be a difference in impact between EPs with and without training.

Our review also has implications for the practice of forensic care. The results suggest that involving experiential peers in the support for individuals with criminal behaviour elicits several mechanisms that are considered beneficial by both EPs and clients (see for instance Barrenger et al., Citation2019; Barrenger et al., Citation2017; Thomas et al., Citation2019; Buck, Citation2014; Portillo et al., Citation2017; Matthews et al., Citation2019). Organisations that do not yet work with experiential peers could explore this possibility. Organisations providing experiential peer support should strive to stimulate empathy, a non-judgmental attitude, and the portrayal of EPs as a positive role model, if they are not already doing so. In addition, several conditions should be met to increase the potential benefits of experiential peer support. Role descriptions and expectations need to be clear (Davidson, Citation2015; Hodgson et al., Citation2019). Studies also suggest that a supportive atmosphere in which EPs and their colleagues appreciate one another and collaborate is essential for positive outcomes (Hodgson et al., Citation2019; Lenkens et al., Citation2020; Nixon, Citation2020). This will be easier to embed in settings familiar with a recovery-oriented perspective. Studies describe that EPs are not always considered credible role models (Buck, Citation2017) and may even cause risk contamination (Creaney, Citation2018). Studies also indicate that there is a risk of overburdening EPs (Harrod, Citation2019; Hodgson et al., Citation2019; Kavanagh & Borrill, Citation2013; Nixon, Citation2020). Organisations should therefore carefully recruit, select, and coach EPs. Lastly, organisations should avoid exploitation of EPs and compensate them financially (Woodall et al., Citation2015; Adams & Lincoln, Citation2020; Nixon, Citation2020; Portillo et al., Citation2017).

Conclusion

Our systematic realist literature review investigated the mechanisms, outcomes, and contextual factors of experiential peer support for and by individuals with criminal behaviour and involvement in the criminal justice system. We found evidence that experiential peers show empathy and have a non-judgmental approach, are considered role models, establish a trusting relationship with clients, offer hope, connect clients to other services and have a recovery-oriented approach. Regarding outcomes of experiential peer support, we found results indicative of act-desistance, positive personal development and improvements in mental health and personal circumstances, although study results were not consistent. Our realist review does not allow us to draw conclusions about which hypothesised mechanisms are mediators of the relationship between experiential peer support and outcomes. However, this study does emphasise the importance of several mechanisms in interventions with experiential peer support. Research investigating long-term effects and more broadly defined desistance-supportive outcomes is needed.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Gerdien B. de Jonge and Elise Krabbendam of the Medical Library and Judith Gulpers of the University Library (all Erasmus University of Rotterdam) for their help and support with the systematic literature search. We would also like to thank Tessa Magnée of the Erasmus University Rotterdam and our research interns Emy Plaisier, Allisha Biesheuvel, and Lisa Dijkhoff for their assistance in reading and selecting studies for the review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In-custody, offend*, adjudicated, peer driven, peer work*, peer coach*, peer leader*, wounded healer, ex-offender, consumer survivor, consumer provider

References

- Adams, W. E., & Lincoln, A. K. (2020). Forensic peer specialists: Training, employment, and lived experience. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 43(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000392

- Baillergeau, E., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2016). Experiential knowledge as a resource for coping with uncertainty: Evidence and examples from The Netherlands. Health, Risk & Society, 18(7-8), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2016.1269878

- Barker, S. L., Bishop, F. L., Bodly Scott, E., Stopa, L. L., & Maguire, N. J. (2020). Developing a model of change mechanisms within intentional unidirectional peer support (IUPS). European Journal of Homelessness, 14(2), 161–191. https://www.feantsaresearch.org/public/user/Observatory/2020/EJH_142_Final_version/EJH_14-2_WEB.pdf#page=161.

- Barrenger, S. L., Hamovitch, E. K., & Rothman, M. R. (2019). Enacting lived experiences: Peer specialists with criminal justice histories. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000327

- Barrenger, S. L., Stanhope, V., & Atterbury, K. (2017). Challenging dominant discourses: Peer work as social justice work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 29(3), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2017.1399036

- Bellamy, C., Kimmel, J., Costa, M. N., Tsai, J., Nulton, L., Nulton, E., Kimmel, A., Aguilar, N. J., Clayton, A., & O’Connell, M. (2019). Peer support on the “inside and outside”: Building lives and reducing recidivism for people with mental illness returning from jail. Journal of Public Mental Health, 18, 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-02-2019-0028

- Bourgon, G., & Guiterrez, L. (2013). The importance of building good relationships in community corrections: Evidence, theory and practice of the therapeutic alliance. In P. Ugwudike & P. Raynor (Eds.), What works in offender compliance: International perspectives and evidence-based practice (pp. 256–275). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bramer, W. M., Milic, J., & Mast, F. (2017). Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(1), 84–87. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.111

- Buck, G. (2014). Civic re-engagements amongst former prisoners. Prison Service Journal, 214, 52–57. https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/PSJ%20214%20July%202014.pdf.

- Buck, G. (2017). “I wanted to feel the Way they Did”: Mimesis as a situational dynamic of peer mentoring by Ex-offenders. Deviant Behavior, 38(9), 1027–1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2016.1237829

- Buck, G. (2018). The core conditions of peer mentoring. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(2), 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817699659

- Buck, G. (2019a). “It’s a Tug of War between the person I used To Be and the person I want To Be”: The terror, complexity, and limits of leaving crime behind. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 27(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137316684452

- Buck, G. (2019b). Politicisation or professionalisation? Exploring divergent aims within UK voluntary sector peer mentoring. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 58(3), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12305

- Chamberlin, J. (2005). User/consumer involvement in mental health service delivery. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 14(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00001871

- Cos, T. A., LaPollo, A. B., Aussendorf, M., Williams, J. M., Malayter, K., & Festinger, D. S. (2020). Do peer recovery specialists improve outcomes for individuals with substance use disorder in an integrative primary care setting? A program evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 27(4), 704–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09661-z

- Creaney, S. (2018). Children’s voices—are we listening? Progressing peer mentoring in the youth justice system. Child Care in Practice, 26(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1521381

- Davidson, L. (2015). Peer support: Coming of age of and/or miles to go before we sleep? An introduction. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42(1), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9379-2

- Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Sells, D., & Rowe, M. (2006). Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: A report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(3), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj043

- Dishion, T. J., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54(9), 755–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Goldstein, E., Warner-Robbins, C., McClean, C., Macatula, L., & Conklin, R. (2009). A peer-driven mentoring case management community reentry model: An application for jails and prisons. Family & Community Health, 32(4), 309–313. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181b91f0d

- Grainer, D., & Higham, D. (2019). When assets collide: The power of lived experience. Prison Service Journal, 242, 38–43. https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/PSJ%20242%20March%202019_Prison%20Service%20Journal.pdf.

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2014). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Harrod, C. (2019). The peer mentor model at RecycleForce: An enhancement to transitional jobs programs. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 58(4), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2019.1596190

- Hodgson, E., Stuart, J. R., Train, C., Foster, M., & Lloyd, L. (2019). A qualitative study of an employment scheme for mentors with lived experience of offending within a multi-agency mental health project for excluded young people. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 46(1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9615-x

- Hughes, W. (2012). Promoting offender engagement and compliance in sentence planning: Practitioner and service user perspectives in Hertfordshire. Probation Journal, 59(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550511429844

- James, N., & Harvey, J. (2015). The psychosocial experience of role reversal for paraprofessionals providing substance misuse and offender treatment: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Forensic Practice, 17(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-10-2014-0032

- Jardine, C., & Whyte, B. (2013). Valuing desistence? A social return on investment case study of a throughcare project for short-term prisoners. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 33(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2013.768088

- Kavanagh, L., & Borrill, J. (2013). Exploring the experiences of ex-offender mentors. Probation Journal, 60(4), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550513502247

- Kortteisto, T., Laitila, M., & Pitkänen, A. (2018). Attitudes of mental health professionals towards service user involvement. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12495

- Lenkens, M., Nagelhout, G. E., Schenk, L., Sentse, M., Severiens, S., Engbersen, G., Dijkhoff, L., & Van Lenthe, F. J. (2020). ‘I (really) know what you mean’. Mechanisms of experiential peer support for young people with criminal behavior: A qualitative study. Journal of Crime and Justice, https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2020.1848608