ABSTRACT

How police and citizens behave during encounters can influence public perceptions of the deservingness of treatment citizens receive from police. Yet perceiving another citizen as deserving of police treatment may be explained by other factors. This study tests if minority observers’ identity with police and identity with the citizen in the encounter conditions how they judge that citizen’s deservingness of procedurally just or unjust treatment from police utilizing survey data with an embedded vignette experiment collected from 502 Muslim participants. The sample was split by the exhibited behavior of the police officer (as either procedurally just or unjust) to assess the effect of citizen behavior (either respectful or disrespectful) and identity processes on deservingness judgments. Findings show that the citizen in the encounter was perceived as less deserving of the treatment received when the police officer was procedurally unjust, particularly when the citizen acted respectfully. Additionally, identity with police shaped participants’ deservingness judgments, while identification with the citizen in the encounter did not. Importantly, identification with police moderated the relationship between citizen behavior and deservingness evaluations, but only for participants in the procedurally unjust police behavior condition. Implications for understanding minorities’ deservingness judgments in vicarious police-citizen encounters are discussed.

Public perceptions of vicarious police-citizen encounters are contingent on how the encounter unfolds (Mazerolle et al., Citation2013; Nix et al., Citation2017; Nix et al., Citation2019). When police behave professionally and treat individuals with procedural justice (i.e. with respect, dignity, and without bias), an encounter will generally be perceived more positively. When police are procedurally unjust, however, it can negatively influence perceptions of police in the encounter (Mazerolle et al., Citation2013; Murphy et al., Citation2014). How citizens behave in encounters can also influence observers’ perceptions of an encounter (Pickett & Nix, Citation2019; Reisig et al., Citation2004). When citizens behave disrespectfully toward police, this can result in more negative perceptions of the citizen.

Pertinent to the current study is the extent to which observers of a vicarious police-citizen encounter feel that a citizen involved in the encounter ‘deserves’ the treatment they receive from police (Sunshine & Heuer, Citation2002). Deservingness encompasses the idea that individuals who behave in a positive manner should experience and deserve positive outcomes, while those who behave in a negative or inappropriate manner should receive and deserve negative outcomes (Feather, Citation1999; Olson et al., Citation2010). The notion of deservingness is inextricably linked to perceptions of justice, and specifically, whether ‘people deserve to be treated fairly’ by authorities (Feather, Citation1999, p. 87). Consequently, if observers perceive that the treatment a citizen receives from police violates their expectations of what they believe they deserve, it can trigger hostile reactions toward police, including anger and outrage (Sunshine & Heuer, Citation2002).

Police officers’ treatment of citizens during encounters, and the associated consequences, has become a key research area in recent years. Procedural justice in policing speaks to the importance of police being neutral, trustworthy, and respectful of citizens, as well as providing citizens opportunities for voice in encounters (Tyler, Citation2006). Research consistently shows that when police treat citizens in a procedurally just way in both direct and vicarious encounters, it positively affects public perceptions of police legitimacy, trust in police, satisfaction with police, and willingness to voluntarily comply and cooperate with police (see Donner et al., Citation2015).

While procedural justice denotes a best practice approach for how police officers should behave in encounters, the impact of citizens’ behaviors during an encounter also plays a significant role in determining a police officer’s decisions on how to respond (Mastrofski et al., Citation2002). For example, if a citizen behaves in a disrespectful or hostile way towards a police officer, it can provoke a negative response from police officers which can exacerbate the citizen’s resistance. How police subsequently respond may also aggravate broader police-citizen tensions in the community (see e.g. Reisig et al., Citation2004). Moreover, disrespectful citizen behavior toward police may increase the likelihood that an officer will respond punitively. This might include fining the individual, arresting them, or using inappropriate force (see e.g. Engel et al., Citation2000; James et al., Citation2018). Yet empirical evidence also shows that members of the public are more likely to condone coercive and disrespectful treatment from police officers when they observe citizens being disrespectful toward police (Waddington et al., Citation2015). Hence, how both police and citizens behave is important to consider when determining how observers perceive vicarious police-citizen encounters, and in deciding how deserving a citizen is of the treatment they receive from police.

The current study examines the conditions under which minority observers perceive a citizen as either deserving or undeserving of the treatment they receive from police. It does so by exploring the interaction between a citizen’s behavior in a vicarious police-citizen encounter and the observer’s strength of identity with the police and the citizen depicted in the encounter. It uses survey data with an embedded vignette experiment collected from 502 Muslim observers. The vignettes depict a vicarious police encounter with a Muslim citizen. The behavior of both the police officer (procedurally just vs unjust) and the Muslim citizen (respectful vs disrespectful) are manipulated between participants. The sample is then split by the police officer manipulation and the effect of the citizen behavior manipulation on deservingness judgements is assessed. Importantly, we test if Muslim observers’ level of ‘identification with police’ and ‘identification with Muslims’ moderate the effect of the citizen’s behavior on subsequent deservingness judgments. By exploring these interaction effects, we can better understand the social psychological processes that may explain when and why minority citizens are perceived as more or less deserving of the treatment they receive from police. This is particularly important to disentangle in an era where social justice movements, such as ‘Black Lives Matter’, have spotlighted police treatment of minority communities, and minorities’ interpretations of such treatment.

The influence of police and citizens’ behavior during a police-citizen interaction

Evaluations of police conduct toward citizens have long been understood as a product of the fairness/justness of procedures employed by police during citizen encounters (Mazerolle et al., Citation2013; Tyler, Citation2006). As noted earlier, procedural justice is cited as key to positively influencing public perceptions of police legitimacy, trust in police, satisfaction with police, and willingness to cooperate with police. People value procedural justice from police because how police treat citizens communicates important symbolic information about that citizen’s perceived value and status in society (Tyler & Lind, Citation1992; see also Bradford et al., Citation2014). Procedurally just treatment conveys higher value and status, while unjust treatment expresses the opposite (Bradford et al., Citation2014).

A substantial research base shows how procedural justice can positively impact public perceptions of police officers (see Donner et al., Citation2015). Yet recent studies have started to explore the importance of citizen behavior in police-citizen encounters as well. This is due to the notion that procedural justice effects can only be holistically understood when considered ‘as a “perpetual dialogue” between citizens and police’ (Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2012, p. 129), meaning that police do not operate in a vacuum. Rather, their behavior during encounters with the public can also be influenced by how citizens behave and respond to police in encounters. Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012) note that most procedural justice policing studies typically focus on citizens’ reactions to police behavior. They suggest that accounting for the behavior of both police officers and citizens can yield greater insight into what mechanisms might explain public judgements of police treatment towards citizens.

Central to such judgments is whether individuals believe that they or others deserve respectful treatment from police. Deservingness judgments can be a product of a person’s behavior, and specifically, whether they behave in ‘morally acceptable or unacceptable ways’ (Feather, Citation1999, p. 8). Feather (Citation1999) elaborated on this when discussing his ‘matching hypothesis’. Feather posited that if an individual and authority both act in a positive way (e.g. respectfully), evaluations of the authority as fair will be more likely than if the individual or authority acts in a negative way (e.g. disrespectfully). Nix et al. (Citation2019) suggested that if an individual acts in a disrespectful way towards a police officer, that police officer may view the individual as morally deserving of punishment (see also Pickett & Nix, Citation2019).

Studies have empirically tested this ‘matching hypothesis’ in policing and non-policing contexts. For example, Heuer et al. (Citation1999) undertook an experimental vignette study that depicted a vicarious encounter between an employee and their direct manager. The authors manipulated both the manager’s treatment of the employee and the employee’s behavior as respectful or disrespectful. While they did not examine deservingness judgments as an outcome variable, they tested whether perceived deservingness moderated the relationship between behavior and fairness evaluations. Heuer et al. (Citation1999) showed that when the employee in the vignette behaved in a respectful way, participants judged the manager’s respectful treatment as fairer when compared to those who received the vignette describing the manager’s behavior as disrespectful. This effect was notably stronger amongst those who felt the employee deserved fair treatment. Yet participants were more likely to state that disrespectful treatment from the manager was fairer when the employee in the vignette acted disrespectfully (compared to respectfully).

Sunshine and Heuer (Citation2002) yielded similar results in their study of actual and vicarious experiences of police-citizen encounters. The authors examined the extent to which participants’ judgments of fairness were shaped by both the police officer’s behavior and whether participants themselves felt they deserved a certain type of treatment. Findings showed that while procedurally just treatment was strongly and positively associated with participants’ judgments of encounter fairness, this relationship was much stronger amongst those who felt they or the individual in the vicarious encounter deserved to be treated fairly. Together, these studies confirm Feather’s (Citation1999) ‘matching hypothesis’. They also suggest that how an authority and a citizen behave during an encounter, and evaluations regarding deservingness, can alter the perceived fairness of the authority’s behavior.

What remains unanswered from existing research is an understanding of the antecedents of deservingness judgments. While the behavior of both citizens and police during an encounter seems important for shaping public judgments of police fairness, the effect of such behaviors on evaluations of a citizen’s deservingness of procedurally just or unjust police treatment remains unclear. Adding to this, we propose that deservingness judgments may differ depending on whether an observer ‘identifies’ with each actor involved in the encounter. Social Identity Theory (SIT) researchers show that people view members of their own ingroup more favorably, and tend to support ingroup members more than outgroup members (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). Hence, the perceived deservingness of a citizen in a police-citizen encounter might be contingent not only on the police officer’s or citizen’s behavior in the encounter, but also on how strongly observers identify with both the police officer and citizen.

Group identity: an explanation for variation in deservingness judgments

Social Identity Theory (SIT) explains how shared group membership and strength of identification with groups is fostered, how groups behave based on shared identities, and how group membership impacts one’s feelings and behaviors towards ingroup and outgroup members (Scheepers & Ellemers, Citation2019). A key function of shared group identity is to ensure that the group a person identifies with (i.e. the ingroup) is positively distinct from groups perceived to be different (i.e. the outgroup) (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Individuals can identify with groups in different ways. They can identify with a group based on some shared physical characteristic (e.g. race, gender, age group) or they may identify with a group based on a shared social characteristic (e.g. values, worldviews, religious affiliation, citizenship with a particular country) (Brown, Citation2000). In this way, Muslim individuals, for example, may identify with other Muslims because of their shared religious affiliation. These same individuals may also identify with police officers because police share certain values and norms the individual deems important.

Tajfel and Turner (Citation1979) argue that those who identify strongly with their ingroup tend to see their own group more positively and view them as superior to other groups. A consequence of such perceived ingroup superiority is that derogation of outgroup members can be intensified (Brewer, Citation1999). Moreover, social identification emerging from membership in a marginalized or low-status group can create feelings of threat: in response to such feelings of threat, individuals will strive to maintain a positive sense of self (Aquino & Douglas, Citation2003). Resultantly, perceived outgroup members can be viewed negatively. However, more recent work has demonstrated that such processes can occur at the intragroup level as well (Brown, Citation2020). Central here is acknowledging the norms that govern ingroup behavior, and how deviations to these norms are managed (Tankard & Paluck, Citation2016). Those that behave in a way contrary to defined ingroup norms can exemplify what ingroup members consider to be acceptable and unacceptable (Abrams et al., Citation2000). Hence, how one formulates their identity within their defined ingroup and how they compare their group with perceived outgroups may play an important role in how they interpret intergroup contacts.

Policing research consistently reveals that ethnic/racial minority groups, relative to non-minorities, perceive police as more biased and procedurally unjust (e.g. Madon et al., Citation2022). Minorities are also more likely to perceive police treatment of minority citizens as more biased than the same treatment directed at non-minority citizens (Johnson et al., Citation2017). Such research implies that minorities might automatically judge a minority citizen from their own ethnic/racial group (i.e. a member of their ingroup) as less deserving of procedurally unjust police treatment, irrespective of how the citizen actually behaves in the encounter. Theorizing suggests that responding in this way assists minorities to maintain a positive sense of self and their group in response to a perceived threat (Aquino & Douglas, Citation2003). Feather (Citation1999, p. 92) specifically argues that ‘an ingroup member may be judged as more deserving of a positive outcome and less deserving of a negative outcome when compared with an outgroup member’. Hence, group identity processes may elucidate when and why individuals perceive others as more or less deserving of just or unjust treatment from police.

Having said that, research also suggests that individuals can sometimes be punitive toward ingroup members when ingroup members violate the ingroup’s norms (Lewis & Sherman, Citation2010; Marques et al., Citation1998). Research on the ‘black sheep effect’ shows that ‘deviant’ ingroup members are more likely to be disproportionately derogated by other ingroup members because their actions bring shame on the group (Marques et al., Citation1988; Marques & Paez, Citation1994). Marques et al. (Citation1988) argue that denigrating a deviant ingroup member is a technique employed to preserve the positive reputation of one’s ingroup (see also van Prooijen & Lam, Citation2007). Derogation of undesirable ingroup members is also a strategy that psychologically purges from the group those ingroup members who negatively contribute to the group (Marques & Paez, Citation1994).

One common norm in society is the expectation that group members respect group authorities and willingly abide by their rules and laws. This norm extends to respect for police officers (Tyler & Trinkner, Citation2017). Violation of group norms can be perceived negatively by group members, implying that when a citizen acts in a respectful manner towards police, observers who share group membership with that citizen will deem that individual as more deserving of procedurally just treatment from police. In contrast, when the citizen acts disrespectfully towards police, observers will deem that behavior as a violation of group norms and will judge the citizen as more deserving of procedurally unjust treatment. The ‘black sheep effect’ suggests that this effect is notably stronger if the violation is perpetrated by an ingroup member (Marques & Paez, Citation1994). The notion of the ‘black sheep effect’ might be particularly pertinent in the context of examining marginalized minority groups such as Muslim individuals affected by Islamophobia. As a highly stigmatized and marginalized community, Muslims often adopt strategies to distance themselves from other Muslims who may bring disrepute to them or the wider Muslim community (see O’Brien, Citation2011).

In addition to understanding how shared ingroup identity with citizens involved in a police-citizen encounter may influence observers’ deservingness judgments about that citizen, we propose that observers’ ‘identification with police’ – perceiving police to be part of one’s broader ingroup – might also affect deservingness judgments. Empirical studies have shown that individuals are more likely to support police officers and their actions when they identify with police as a distinct group (see Braga et al., Citation2014; Kyprianides et al., Citation2021; Murphy, Citationforthcoming; Murphy et al., Citation2022; Radburn et al., Citation2018). Braga et al. (Citation2014), for example, drew on American survey data and found that participants who identified more strongly with police were more likely to appraise police behavior more positively across various videos (even videos where police were behaving in a procedurally unjust manner).

Murphy (Citationforthcoming) revealed a similar association between Australians’ identification with police and their support for police (see also Murphy et al., Citation2022). Murphy (Citationforthcoming) showed that Australians who identified more strongly with police were more likely to rate police behavior in a vignette more positively and were more likely to say they trusted the police officer depicted in the vignette. Murphy also showed that strength of identification with police moderated how those Australians perceived different vicarious police-citizen encounters. Trust in the police officer conducting the encounter was significantly higher for those who observed a procedurally just encounter compared to a procedurally unjust encounter, but was significantly stronger for those who identified more strongly with police. Murphy posited that procedural justice from an ingroup authority mattered more to participants because procedural justice from an ingroup authority carried more identity-relevant information about their own status and value within Australian society (see also Tyler, Citation1997). Importantly, Murphy (Citationforthcoming) also found a 3-way interaction effect between police behavior, citizen behavior and identification with police on participants’ trust in the officer involved in the encounter. For participants who identified more strongly with police, trust was detrimentally affected when the police officer was procedurally unjust with a respectful citizen. In contrast, trust was less affected when the officer was procedurally unjust with a disrespectful citizen. These effects were not observed, however, for participants who identified weakly with police. Together, Murphy’s (forthcoming) findings support Feather’s (Citation1999) ‘matching hypothesis’. They also suggest that procedurally unjust treatment by an ingroup authority was not tolerated when used with a respectful citizen, but it was when the ingroup police officer encountered a disrespectful citizen.

In sum, group identity may be particularly useful for explaining when and why minority citizens are perceived as more or less deserving of procedurally just or unjust treatment in a vicarious police-citizen encounter. Specifically, deservingness judgments may be shaped not only by the behavior of the two actors involved in the vicarious encounter, but also by the extent to which the individual judging the encounter identifies with those actors (Feather, Citation1999).

Why focus on Muslims in police-citizen encounters?

Our study focuses on Muslims’ perceptions of vicarious police-citizen encounters in Australia. Muslims are the focus because they have experienced protracted stigmatization by police since the 9/11 terror attacks (Breen-Smyth, Citation2014). This stigma fosters the perception that police officers are biased towards Muslims, and subsequently may influence how Muslims evaluate police (Vermeulen & Bovenkerk, Citation2012; Williamson et al., Citation2023). Research drawing on SIT demonstrates how one’s identification with other ingroup minority members can strongly accentuate within group similarities and differences from outgroup members (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). Similarities within groups may be more pronounced amongst stigmatized groups whose social identities protect against the harmful effects of discrimination (Bourguignon et al., Citation2020).

In a study of several different minority communities in Australia (e.g. Vietnamese, Indian and Asian and Middle Eastern Muslims), Murphy et al. (Citation2015) revealed that Muslims were much more distrustful of police and were significantly more likely than other minority groups to perceive police as procedurally unjust. Thus, we suggest as a way to buffer the impact of felt stigma from police, many Muslims might express greater solidarity with other Muslims involved in a police encounter (Schmitt & Branscombe, Citation2002). Due to the salience of religious identification for many Muslims (Martinovic & Verkuyten, Citation2014), these individuals may perceive that other Muslims are more deserving of procedurally just treatment from police officers because of their ingroup status. If a Muslim individual engages respectfully with police officers during an encounter, it follows that a fellow Muslim observer would view that individual as particularly deserving of procedurally just treatment. According to the ‘black sheep effect’, however, a Muslim behaving in a disrespectful manner toward police may be perceived as violating group norms and bringing the entire Muslim community into further disrepute. In this case, procedurally unjust treatment from police may be perceived as more justified and deserving, particularly if the individual observer identifies more strongly with police.

The current study

The current study examines how evaluations of a Muslim citizen’s perceived deservingness of police treatment are contingent on the behavior of both the police officer and citizen during a police-citizen encounter. Most importantly, it examines the extent to which a Muslim observer's identification with police and their Muslim identity moderates the effect of different types of police behavior (procedurally just or unjust) and citizen behavior (respectful or disrespectful of police) on these deservingness judgments.

This study contributes to the literature on deservingness in several ways. Firstly, it seeks to understand how identity processes shape observers’ deservingness judgments. Prior studies have examined deservingness as an explanatory variable for understanding public perceptions regarding the fairness of procedures in policing and non-policing contexts (see e.g. Heuer et al., Citation1999; Olson et al., Citation2010; Sunshine & Heuer, Citation2002). Yet, how the behavior of both police and citizens involved in a vicarious policing encounter alter the perceived deservingness of treatment received may be explained by an observer´s identification with either police or the citizen. In this way, adopting an SIT lens may better elucidate how observers interpret police-citizen encounters.

Secondly, this study examines Muslims’ judgments of deservingness when a member of their own minority group (i.e. another Muslim) is involved in the vicarious police-citizen encounter. To the authors’ knowledge, this will be the first attempt to understand a minority observer’s perceptions of the deservingness of police treatment of a citizen who is a member of their own ethnic ingroup. Given the widespread condemnation surrounding police racial discrimination, this will enable us to explore how Muslim minority observers perceive police treatment of Muslim minority citizens (who share the same group identity as them).

Finally, this study contributes to the small but growing procedural justice policing research base that draws on a randomized experimental vignette methodology. By manipulating a police officer’s and citizen’s behavior in a vicarious police-citizen encounter, the causal effect of these behavior manipulations on the perceived deservingness of the citizen’s treatment by police can be ascertained. This experimental design also enables an examination of how observers’ pre-existing strength of identity with both police and Muslims (i.e. their ethnic ingroup) may moderate the effect of a citizen’s behavior on perceptions of their deservingness in both a procedurally just and unjust police encounter.

Method

Participants and procedure

This study utilizes data from the Police-Muslim Relations Survey, which contained an embedded 2 × 2 between groups vignette experiment. The survey comprises a sample of 502 Arab-Muslims residing in Sydney, Australia (Murphy & Williamson, Citation2021). The survey was developed to canvas Muslim-Australians’ perceptions of police, to examine why some Muslim participants feel reluctant to engage with police, and to understand whether procedural justice promotes Muslims’ willingness to interact with police and report terrorism threats, general crime and victimization to police (see Murphy & Williamson, Citation2021 for the technical report associated with this survey). The study received ethical approval through the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref No: 2019/291). The current paper utilized only a subset of this data (see more below).

Sydney was the chosen study site as it has the highest population of Muslims residing in Australia (45.1% of Australia’s Muslim population live in Sydney) (Hassan, Citation2018). Previous research also shows that Muslims in Sydney – particularly Arab-Muslims – have a more strained relationship with police than in other Australian jurisdictions (Murphy et al., Citation2015). Despite the relatively large population of Arab-Muslims residing in Sydney, Muslims comprise only 5.3% of Sydney’s overall population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016). Consequently, normal random probability sampling techniques were not feasible to recruit the sample. Instead, an ethnic naming sampling strategy was employed. This approach involved compiling a list of 525 common Muslim surnames (e.g. Ahmed, Mohammed), which was then used to randomly select individuals from Sydney’s Electronic Telephone Directory (the Directory includes landline and mobile phone numbers). From this search, a sampling frame of 8,699 potential participants was created.

Muslim interviewers fluent in both English and Arabic then randomly contacted potential participants by telephone from the compiled list. Once contact was made, interviewers ensured random selection within the household by asking to speak to a person in the home who was 18 years or older and whose birthday was most imminent. Study eligibility was assessed by asking the nominated household member if they were Muslim and from one of 22 Arab league nations. To ensure that the final sample closely resembled Arab-Muslims residing in Sydney, demographic quotas for gender (50% female, 50% male), age (+50% < 30 years of age; 50% > 30 years of age), and country of birth (50% Australia; 50% overseas) were also applied. Once study eligibility was established, interviewers organized face-to-face interviews with interested participants. All participants received $40 on completion of a survey.

A key component of the survey included a 2 × 2 between-groups vignette experiment.Footnote1 The 2 × 2 between groups vignette experiment was included in the final section of the survey. Each participant was presented with a vignette depicting a hypothetical vicarious police-citizen encounter. The encounter described a scenario where a police officer stops a young male Muslim driver on suspicion of a terrorism offence. Both the police officer’s and the Muslim citizen’s behavior was manipulated between participants, with participants only receiving one of the four vignettes. Officer behavior in the vignette experiment was manipulated by describing the officer’s conduct as either procedurally just (n = 250; 49.8%) or procedurally unjust (n = 252; 50.2%). All four procedural justice elements of respect, neutrality, trustworthiness, and voice were included in the vignettes. Citizen behavior was also manipulated between participants by describing the citizen’s behavior as either respectful (n = 252) or disrespectful (n = 250) of the officer (see Appendix for full wording of the vignettes). A randomization check across the four conditions revealed that participants did not differ significantly by gender, marital status, or educational attainment, although slightly older participants were more likely to be allocated to the two procedural injustice conditions (M = 35.36 years) compared to the two procedural justice conditions (M = 32.50 years; t(500) = 2.43, p < 0.02).

In total, 504 surveys were completed between August and September 2020 (response rate = 31.25%), but two participants were later removed from the dataset after variable screening (adjusted n = 502). As the survey was fielded using a face-to-face interviewing format, there was no missing data recorded. The final sample was representative of Sydney’s Muslim population (see Murphy & Williamson, Citation2021). Just over half of the sample were born overseas (50.2%; 49.8% were born in Australia), and 50.2% of the sample was male, with a mean age of 33.9 years (SD = 13.2; range 18–79 years). The majority of participants indicated that they were married or in de-facto relationships (50.8%), and nearly a third of participants reported that they were in full-time employment (33.1%). Over a third indicated they had completed tertiary education (35.5%).

Measures

Prior to constructing the multi-item scales used in this study, items were subjected to a principal axis factor analysis with varimax rotation. Each scale showed good discriminant validity (see ). presents the descriptive statistics and bi-variate correlations between the vignette manipulations, independent and dependent variables.

Table 1. Factor loadings for principal Axis factor analysis with varimax rotation of identity scales.

Table 2. Correlation Matrix and descriptive statistics for all measures.

Independent variables

Identification with police: Participants’ strength of identification with police was measured via a three-item scale (Mean = 3.59, SD = 1.04, α = 0.89) (items: ‘I identify strongly with police’; ‘I feel a sense of solidarity with police’; ‘Police and Muslims share a lot in common’). These items were included in the survey prior to introducing the vignette experiment; as such, they measure participants’ strength of identification with police before being exposed to the vignette experiment. Responses were measured on a 1(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) scale, with higher scores on the scale indicating stronger identification with police. The items were adapted from the work of Radburn et al. (Citation2018).

Muslim identification: Participants’ strength of identification as a Muslim was measured via a three-item scale (Mean = 4.71, SD = 0.63, α = 0.87) (items: ‘I am proud to be Muslim’; ‘I identify strongly as a Muslim’; ‘Being a Muslim is important to the way I think of myself as a person’). These items were also included in the survey prior to the vignette and measure participants’ identification as Muslim. Responses were measured on a 1(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) scale; higher scores on the scale indicate stronger identification as a Muslim. Items used for this scale were adapted from the work of Murphy et al. (Citation2007).

Dependent variable

Deservingness of police treatment: The perceived deservingness of police treatment was the key dependent variable. It was measured via a single survey item. After reading their respective vignette scenario, participants were asked to judge how deserving the Muslim in the scenario was to receive the treatment they did from police (‘The young man deserved the treatment he received’). Responses were measured on a 1(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) scale, with higher scores denoting more deservingness of that treatment (M = 2.74; SD = 1.47).

Demographic control variables

A series of control variables were measured: age (M = 33.9; SD = 13.2), gender, educational attainment (M = 5.38; SD = 1.81), country of birth, and marital status. Gender was coded into two categories (males n = 252; females n = 250). Country of birth was a binary measure that accounted for participants born in Australia (n = 250) or overseas (n = 252). Finally, marital status was a binary measure, representing those who reported being married (n = 255) or unmarried (n = 247).

Results

Analytic approach

The dependent variable is perceived deservingness of police treatment. Due to the way the officer’s behavior was manipulated in the vignette scenario, the dependent variable measures different constructs in the procedural justice and procedural injustice conditions. In one condition, participants rate deservingness of procedurally just treatment; in the other, they rate deservingness of procedurally unjust treatment. Hence, including data from both the officer behavior conditions in one analysis makes clean interpretation of the dependent variable difficult. To overcome this issue, the dataset was split so that deservingness of treatment in the procedurally just officer behavior (N = 250) condition could be considered separately from the procedurally unjust officer behavior (N = 252) condition. presents descriptive statistics for the key variables for each of the two split groups. Once the datafile was split according to the officer behavior condition, two ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses were then conducted in SPSS v.28 to examine the effect of the citizen behavior manipulation, and strength of identification with police and identification as Muslim, on participants’ judgments of the citizen’s deservingness of the police treatment they received. Also of interest was whether participants’ strength of identity with police or their Muslim identity moderated the effect of the citizen’s behavior manipulation on deservingness judgments.Footnote2 As shown below, the pattern of results varied substantially between the ‘procedurally just officer behavior’ subsample and the ‘procedurally unjust officer behavior’ subsample.Footnote3

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for split sample.

Variables were entered into the two OLS regression models in two blocks for each of the two subsamples. The three independent variables (citizen behavior; identification with police; identification with Muslims) were entered into Block 1. In Block 2, two 2-way interaction effects were entered: ‘citizen behavior × identification with police’ and ‘citizen behavior x identification as a Muslim’. The regression findings are presented in .Footnote4

Table 4. OLS regression predicting citizen’s deservingness of police treatment received.

OLS regression: ‘procedurally unjust’ police vignette condition participants

Analyses were first conducted with the subsample who received the vignette condition describing the police officer’s behavior as procedurally unjust. In Block 1, the three independent variables accounted for 9.3% of the variance in perceived citizen deservingness of the officer’s treatment. As expected, citizen behavior was negatively associated with deservingness judgments in the procedurally unjust police subsample group (b = −0.51, p < 0.001, 95%CI(−0.78, −0.25)); those who received the vignette describing the citizen as respectful during the police interaction were less likely to deem the citizen as deserving of the procedurally unjust treatment from the police officer. Also as expected, strength of identity with police was positively associated with deservingness judgments (b = 0.20, p < 0.01, 95%CI(0.07, 0.33)); the more participants identified with the police, the more they felt the citizen deserved the treatment they received, despite it being of a procedurally unjust nature. However, the Muslim identity main effect was not significant. This non-significant finding suggests that in this sample, Muslim identification does not seem to affect deservingness judgments of procedurally unjust police treatment.

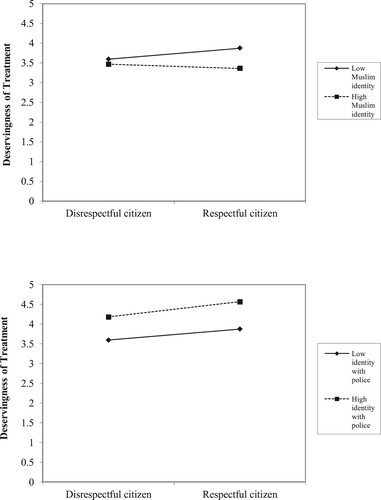

On entry of the interaction effects in Block 2, the model accounted for 18.5% of the variation in deservingness judgements. Block 2 revealed that the 2-way interaction between ‘citizen behavior and Muslim identity’ was not significant (b = −0.15, p = 0.65, 95%CI(−0.56, 0.25)), but the 2-way interaction between ‘citizen behavior and identity with police’ was significant (b = −0.65, p < 0.01, 95%CI(−0.90, −0.40)). To explore the nature of the non-significant and significant interaction effects further, we conducted simple slopes tests and plotted both the non-significant and significant interaction effects in A,B respectively.

Figure 1. Interaction effects between: (a) ‘citizen behavior’ × ‘Muslim identity’ or (b) ‘citizen behavior’ × ‘identification with police’ on perceived deservingness of police treatment, when the police officer was procedurally unjust.

In the case of the non-significant ‘citizen behavior × Muslim identity’ interaction (see A), simple slope analyses revealed that the citizen’s behavior had the same negative effect on deservingness judgements for those scoring lower on Muslim identity (b = −.51, p < .001) as for those scoring higher on Muslim identity (b = −.66, p < .01); when the citizen was disrespectful of police they were consistently evaluated as being less deserving of respectful treatment from police.

B plots the significant ‘citizen behavior × identification with police’ interaction effect. Simple slopes tests for this interaction revealed that when participants identified more weakly with police, the citizen behavior effect had a strong negative relationship with deservingness judgements (b = −0.50, p < 0.001). This effect was even stronger, however, for those who identified more strongly with police (b = −1.16, p < .001).

OLS regression: ‘procedurally just’ police vignette condition participants

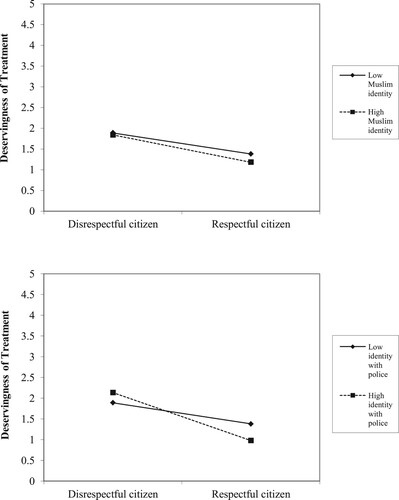

A second OLS regression analysis was conducted with the subsample who received the procedurally just officer behavior vignette condition. In Block 1, the three independent variables accounted for 22.6% of the variance in perceived citizen deservingness of the officer’s treatment. Citizen behavior was not significantly associated with deservingness judgments; participants who received the vignette depicting a respectful citizen were no more likely to evaluate them as deserving of procedurally just police treatment when compared to a disrespectful citizen. In contrast, identification with police was significantly and positively associated with deservingness judgments (b = 0.58, p < 0.001, 95%CI(0.44, 0.71)); that is, Muslim observers who identified more strongly with police were also more likely to believe the Muslim citizen was deserving of the police treatment received. Muslim identity was also unrelated to deservingness judgements amongst participants who received the procedurally just officer vignette.

In Block 2, the two 2-way interaction terms were entered into the model, contributing to a total of 23.4% variation in the model. Importantly, however, neither the ‘citizen behavior × Muslim identification’ interaction effect, nor the ‘citizen behavior × identification with police’ interaction effect were statistically significant. plots these two non-significant interactions effects.

Discussion and implications

This study tested the causal effect of a hypothetical vicarious police-citizen encounter on minority observers’ perceptions of the citizen’s deservingness of the police treatment received. In the hypothetical encounter, the citizen’s behavior was manipulated as either respectful or disrespectful and the police officer’s behavior was manipulated as either procedurally just or unjust. This study further explored whether participants’ strength of identification with police or with Muslims influenced the perceived deservingness of the citizen’s treatment by police between the two citizen behavior conditions.

While acknowledging previous research and the pivotal role of police behavior during a police-citizen encounter, this study was primarily interested in understanding how a minority citizen’s behavior during a police-citizen encounter influenced perceived deservingness of police treatment judgments. Findings revealed that variation in a citizen’s behavior (respectful or disrespectful of police) was associated with deservingness judgments. Those who received the ‘procedurally unjust police officer’ vignette were more likely to perceive a respectful citizen as undeserving of the treatment they received and the disrespectful citizen as deserving of the treatment they received. In contrast, those who received the ‘procedurally just police officer’ vignette were more likely to perceive a respectful citizen as deserving of the treatment they received and the disrespectful citizen as undeserving of that police treatment. These findings reinforce Feather’s (Citation1999) ‘matching hypothesis’, and also speak to the perceived moral deservingness of the Muslim citizen in the vicarious encounter.

The notion of moral deservingness has previously been discussed in the context of police officers’ attitudes towards members of the public. Research suggests that officers who receive disrespectful treatment from citizens tend to see those citizens as more deserving of punishment (Pickett & Nix, Citation2019). The current study suggests that Muslim observers may hold similar views of other Muslim citizens who disrespect police officers, even when those citizens share common ingroup membership with the observer. Thus, our study provides evidence suggesting that how a citizen behaves during a police-citizen encounter holds some weight in explaining whether a citizen is perceived as deserving or underserving of the treatment they receive from a police officer. Importantly, this finding also points to the dialogic nature of police-citizen encounters (Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2012; Lowrey-Kinberg & Sullivan Buker, Citation2017). That is, to fully understand when and why procedural (in)justice produces positive or negative effects during police-citizen encounters, studies need to consider the dialogue that occurs between both police and citizens.

The findings also highlight the role of identity processes in altering deservingness judgments, but not in the ways initially expected. On the one hand, we proposed that observers of the vicarious police-citizen encounter may have viewed the Muslim citizen in the vignette as more deserving of procedurally just treatment because the citizen belonged to a valued ingroup (i.e. shared Muslim identity by virtue of sharing the same minority and religious identity). Yet, we also proposed that disrespectful behavior by the Muslim citizen may have been evaluated more punitively by Muslim observers because of the so called ‘black sheep effect’ (Marques & Paez, Citation1994). According to the ‘black sheep effect’, when ingroup members are seen to behave in ways contrary to established ingroup norms and values (e.g. disrespecting police), other ingroup members can denigrate them as a way to distance themselves from the ‘deviant’ individual and to protect the positive reputation of their ingroup as a whole (Marques et al., Citation1998; Marques & Paez, Citation1994). In other words, we proposed Muslim observers may be more inclined to perceive a disrespectful Muslim citizen as undeserving of procedurally just treatment and deserving of procedurally unjust treatment from police to differentiate themselves from the deviant ingroup member. Doing so may serve to deflect the shame the deviant ingroup member has brought to their group as a whole (Marvasti, Citation2005).

While we expected this pattern of results, we actually found no direct relationship between strength of Muslim identity and deservingness judgments, nor did we find a significant interaction effect between Muslim identity and citizen behavior in either the ‘procedurally just’ officer behavior subsample or the ‘procedurally unjust’ officer behavior subsample. These findings suggest that in the context of police-citizen encounters, at least, strength of identification with one’s ingroup may not be as important for understanding the perceived deservingness of an ingroup citizen’s treatment by police.

Despite the null findings when considering Muslim identification, our results did point to the important role of minority citizens’ identification with police. We found that Muslim participants’ identification with police seemed important to understanding their evaluations of deservingness of treatment. Results first showed that participants who identified more strongly with police were more inclined to support police behavior (i.e. measured as perceived deservingness of police treatment received), regardless of the type of police behavior displayed. Specifically, the perceived deservingness of the Muslim citizen was higher when participants identified more strongly with police; this was so in both the procedurally just and procedurally unjust police officer behavior subsamples. This finding supports prior studies that show that identification with police can enhance public support for police actions (e.g. Braga et al., Citation2014; Murphy, Citationforthcoming).

We also found some support for the suggestion that identification with police moderated the citizen behavior effect on deservingness evaluations. Findings showed that deservingness judgments were much stronger for participants who reported identifying more strongly with police, but this was only the case when participants received the vignette describing the police officer’s behavior as procedurally unjust. That is, Muslim observers who identified more strongly with police were more likely to condone unjust police behavior when police interacted with a disrespectful Muslim citizen than a respectful citizen. When observers identified weakly with police, however, it did not seem to matter how the citizen behaved (respectful or disrespectful). The ‘identification with police × citizen behavior’ interaction effect was not observed in the procedurally just police behavior condition.

It is important to note that our findings demonstrated that identification with police mattered more than ingroup identification (as a Muslim) in shaping participants’ deservingness evaluations. At its core, the tenets of SIT suggest that an individual’s social context at a given time can influence the salience of elements of their social identities (Scheepers & Ellemers, Citation2019; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). In this way, the components of an individual’s identity that emphasize the importance of adhering to norms, rules and laws may have been activated more readily in a study that asked participants to consider their attitudes towards police. Moreover, when considering prior theorizing of the association between identity and evaluations of police, this is perhaps unsurprising. The Group Value Model (Lind & Tyler, Citation1988), for example, posits that police conduct becomes more salient to individuals who identify more strongly with the police.

Taken together, our findings suggest that if police wish to garner support for their decisions or actions, they need to be cognizant of how they treat Muslim citizens. Importantly, police need to ensure that the communities they serve feel a sense of solidarity with police and see police as ingroup members who share common values and goals. The implication of this is that a shared sense of group identity between police and Muslims may heighten individuals’ expectations that police will treat them or other members of their ingroup in the manner that they deserve (Nanes, Citation2020). Identification with one’s own minority group does not appear to play a role in how observers interpret or judge vicarious police-citizen encounters. This shifts the onus of responsibility back onto police to ensure that they treat all minorities justly – not just Muslims – and promote a shared sense of solidarity and identity with minority communities.

Limitations and future directions

Before concluding, it is pertinent to acknowledge this study’s limitations. Firstly, this study utilized written vignettes describing the behavior of a police officer and a Muslim citizen during a police-citizen encounter. While this format enabled a causal understanding of deservingness judgments to be determined, it failed to capture potential behavioral cues (e.g. eye contact, tone of voice, body language) that might exist in police-citizen encounters that can communicate respect or disrespect from both parties (Giles et al., Citation2012). This limitation may be overcome by utilizing video-recorded vignette scenarios where behaviors can be observed and evaluated.

Relatedly, the vignette wording describing the Muslim male as disrespectful does not disentangle the difference between the citizen’s demeanor and their subsequent non-compliance (i.e. when they began to walk away from the police officer). Thus, it is unclear whether observers’ reactions to the vignette were informed by the male’s demeanor (i.e. respectful or disrespectful behavior), their non-compliance, or a combination of both. Given the importance of citizen behavior and compliance on police officer decision-making, future experimental vignette research may wish to explicitly explore the distinct effects of these two behavioral factors on individual observers’ interpretations of police-citizen encounters.

Further, the vignettes used in this study depicted a vicarious police-citizen encounter. Vicarious experiences might elicit different responses when compared to personal experiences. Prior research has drawn on personal and vicarious encounters with police to understand the effects of those encounters (Sunshine & Heuer, Citation2002). Therefore, it may be fruitful to draw on actual experiences with police encounters to understand if the relationships tested in this study also exist amongst minority individuals who have experienced personal encounters with police. With respect to measurement, while the dependent variable gauges participants’ perceptions of the extent to which the young Muslim in the scenario deserved the procedurally unjust or just treatment they received from the police (depending on which vignette they received), future research may consider utilizing a multi-item scale that addresses perceived deservingness of different aspects of procedural justice or injustice. For example, the inclusion of items such as ‘The young man deserved to be treated with respect by the officer’ and ‘The young man was treated with a level of fairness he deserved’ would comprise a more accurate deservingness scale that accounts for whether the male in the scenario (a) deserved procedural justice and (b) received the treatment he deserved.Footnote5

Also, while this study focused on Muslim minority observers’ perceptions of the deservingness of a Muslim citizen in a police encounter, it only focused on Muslim participants’ attitudes. Thus, the generalizability of our findings to other population groups remains unclear. Determining if deservingness judgments may differ between Muslim and non-Muslim observers (both minority and non-minority observers) would be important to further explore how ingroup and outgroup identities might differentially affect deservingness judgments of a Muslim citizen’s treatment by police. While strength of Muslim identity did not seem to matter for deservingness judgements in our study, it might be the case that findings will differ for non-Muslim observers when their strength of identity with the Muslim suspect is captured. Related to this point, we should note that our participants scored very highly on the Muslim identity scale and there was low variability in these identity scores between participants. Hence, it is possible that a ceiling effect obscured the relationship between Muslim identity and deservingness judgements or obscured a potential interaction effect between Muslim identity and citizen behavior. In other words, it is possible that we failed to observe ‘Muslim identity × citizen behavior’ interaction effects on deservingness judgments due to the lack of variability in Muslim identity scores. This provides another justification for why including both a Muslim and non-Muslim sample in future studies would be of benefit.

Finally, as our sample comprised a hard-to-reach population, we used an ethnic surname sampling frame to recruit Muslim participants. Although this approach is statistically sound and can yield representative samples of specific small population groups (Challice & Johnson, Citation2005), this technique will not have identified all potential participants in Sydney’s Arab-Muslim population (e.g. women who had married outside their faith and may have changed their surname; those not listed in the telephone directory). Relatedly, it is also possible that Muslim participants who held more positive attitudes toward police were more likely to agree to participate in a study about policing. Such self-selection bias may have impacted the results so should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study demonstrated the ways that Muslim minority observers of police-citizen encounters make assessments regarding a Muslim citizen’s deservingness to receive procedurally just or unjust police treatment. Specifically, findings showed that the behavior of a Muslim individual involved in the encounter shaped Muslim observers’ deservingness judgments. Findings also showed some support for Social Identity Theory in explaining when and why Muslim observers viewed a citizen involved in a police-citizen encounter as more or less deserving of procedurally just or unjust police treatment. Specifically, we found that when Muslims identify more strongly with police, they are more likely to support police actions and judge other Muslims as more deserving of the treatment they received from police (regardless of whether that treatment was just or unjust). Shared identification with the minority citizen’s group did not appear to matter, however. Hence, the current study enhanced our understanding of the conditions that affect how Muslims interpret vicarious police-citizen encounters involving other Muslim citizens. As noted earlier, however, police should take note of how they treat all people; procedural justice should always be front and center, regardless of how a citizen behaves and regardless of how police think observers will evaluate their conduct. The findings also suggest that police would benefit from building Muslims’ sense of identification and solidarity with police.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the second author, Kristina Murphy, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A pre-study power analysis revealed that a minimum of 320 participants was required to detect medium effect sizes (i.e., minimum of 80 participants in each experimental condition).

2 We conducted OLS regression analyses as opposed to ordinal logistic regression analyses as we violated minimum sample size guidelines for a logistic regression (Bujang et al., Citation2018).

3 Before outlining the regression analyses in detail, a manipulation check test was performed. It revealed that participants assigned to the procedurally just officer condition perceived the officer as more procedurally just (M = 4.15; SD = 0.80) than participants assigned to the procedurally unjust officer condition (M = 2.10; SD = 0.98)(t(466) = 24.54, p < 0.001).

4 Two additional regression analyses were conducted whereby age was entered in Block 1 of the regression model. This was done to control for the differences in age across the vignette conditions. Inclusion of these variables had no effect on the results regardless of whether participants received the vignette describing the police officer’s behavior as procedurally just or unjust; hence, the final regression is presented without this variable included.

5 The authors would like to acknowledge an anonymous reviewer who read a previous version of this manuscript and suggested the wording of the items that are presented.

References

- Abrams, D., Marques, J. M., Bown, N., & Henson, M. (2000). Pro-norm and anti-norm deviance within and between groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 906. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.906

- Aquino, K., & Douglas, S. (2003). Identity threat and antisocial behavior in organizations: The moderating effects of individual differences, aggressive modeling, and hierarchical status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90(1), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00517-4

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). 2016 census. Australian Government. https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/2016

- Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 102(1), 119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23145787

- Bourguignon, D., Teixeira, C., Koc, Y., Outten, H., Faniko, K., & Schmitt, M. (2020). On the protective role of identification with a stigmatized identity: Promoting engagement and discouraging disengagement coping strategies. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(6), 1125–1142. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2703

- Bradford, B., Murphy, K., & Jackson, J. (2014). Officers as mirrors: Policing, procedural justice and the (re)production of social identity. British Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu021

- Braga, A. A., Winship, C., Tyler, T. R., Fagan, J., & Meares, T. L. (2014). The salience of social contextual factors in appraisals of police interactions with citizens: A randomized factorial experiment. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 30(4), 599–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9216-7

- Breen-Smyth, M. (2014). Theorising the “suspect community”: Counterterrorism, security practices and the public imagination. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 7(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2013.867714

- Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

- Brown, R. (2000). Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(6), 745–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0992(200011/12)30:6<745::AID-EJSP24>3.0.CO;2-O

- Brown, R. (2020). The social identity approach: Appraising the Tajfellian legacy. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12349

- Bujang, M. A., Sa’at, N., Bakar, T. M. I. T. A., & Joo, L. C. (2018). Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: Emphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 25(4), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.4.12

- Challice, G., & Johnson, H. (2005). The Australian component of the 2004 international crime victimisation survey technical and background paper. Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/tbp016.pdf

- Donner, C., Maskaly, J., Fridell, L., & Jennings, W. (2015). Policing and procedural justice: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(1), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2014-0129

- Engel, R., Sobol, J., & Worden, R. (2000). Further exploration of the demeanor hypothesis: The interaction effects of suspects’ characteristics and demeanor on police behavior. Justice Quarterly, 17(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820000096311

- Feather, N. (1999). Judgments of deservingness: Studies in the psychology of justice and achievement. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(2), 86–107. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0302_1

- Giles, H., Linz, D., Bonilla, D., & Gomez, M. L. (2012). Police stops of and interactions with Latino and White (Non-Latino) drivers: Extensive policing and communication accommodation. Communication Monographs, 79(4), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.723815

- Hassan, R. (2018). Australian Muslims: The challenge of Islamophobia and social distance. University of South. https://www.unisa.edu.au/contentassets/4f85e84d01014997a99bb4f89ba32488/australian-muslims-final-report-web-nov-26.pdf

- Heuer, L., Blumenthal, E., Douglas, A., & Weinblatt, T. (1999). A deservingness approach to respect as a relationally based fairness judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(10), 1279–1292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299258009

- James, L., James, S., & Vila, B. (2018). Testing the impact of citizen characteristics and demeanor on police officer behavior in potentially violent encounters. Policing: An International Journal, 41(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-11-2016-0159

- Johnson, D., Wilson, D. B., Maguire, E. R., & Lowrey-Kinberg, B. V. (2017). Race and perceptions of police: Experimental results on the impact of procedural (in) justice. Justice Quarterly, 34(7), 1184–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1343862

- Kyprianides, A., Bradford, B., Jackson, J., Yesberg, J., Stott, C., & Radburn, M. (2021). Identity, legitimacy and cooperation with police: Comparing general-population and street-population samples from London. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 27(4), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000312

- Lewis, A., & Sherman, S. (2010). Perceived entitativity and the black-sheep effect: when will we denigrate negative ingroup members? The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903366388

- Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Lowrey-Kinberg, B. V., & Sullivan Buker, G. (2017). “I’m giving you a lawful order”: Dialogic legitimacy in Sandra Bland’s traffic stop. Law & Society Review, 51(2), 379–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12265

- Madon, N., Murphy, K., & Williamson, H. (2022). Justice is in the eye of the beholder: A vignette study linking procedural justice and stigma to Muslims’ trust in police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09510-4

- Marques, J., Abrams, D., Paez, D., & Martinez-Taboada, C. (1998). The sole of categorization and in-group norms in judgments of groups and their members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 976–988. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.976

- Marques, J., & Paez, D. (1994). The ‘black sheep effect’: Social categorization, rejection of ingroup deviates, and perception of group variability. European Review of Social Psychology, 5(1), 37–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779543000011

- Marques, J., Yzerbyt, V., & Leyens, J. (1988). The “black sheep effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180102

- Martinovic, B., & Verkuyten, M. (2014). The political downside of dual identity: Group identifications and religious political mobilization of Muslim minorities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(4), 711–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12065

- Marvasti, A. (2005). Being Middle Eastern American: Identity negotiation in the context of the war on terror. Symbolic Interaction, 28(4), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2005.28.4.525

- Mastrofski, S., Reisig, M., & McCluskey, J. (2002). Police disrespect toward the public: An encounter-based analysis. Criminology, 40(3), 519–552. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00965.x

- Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

- Murphy, K., Bradford, B., Sargeant, E., & Cherney, A. (2022). Building immigrants’ solidarity with police: Procedural justice, identity and immigrants’ willingness to cooperate with police. The British Journal of Criminology, 62(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azab052

- Murphy, K., Cherney, A., & Barkworth, J. (2015). Avoiding community backlash in the fight against terrorism. Griffith University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273575879

- Murphy, K. (forthcoming). Minority appraisals of police-citizen encounters: The interaction between situational-context and social identity in a procedural justice experiment. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations.

- Murphy, K., Mazerolle, L., & Bennett, S. (2014). Promoting trust in police: Findings from a randomised experimental field trial of procedural justice policing. Policing and Society, 24(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2013.862246

- Murphy, K., Murphy, B., & Mearns, M. (2007). The 2007 public safety and security in Australia survey: Survey methodology and preliminary findings. Deakin University. https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30051868

- Murphy, K., & Williamson, H. (2021). Engaging Muslims in the fight Against terrorism project. Griffith University. https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/bitstream/handle/10072/408665/Williamson514814-Published.pdf?sequence=3

- Nanes, M. (2020). Policing in divided societies: Officer inclusion, citizen cooperation, and crime prevention. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 37(5), 580–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894218802580

- Nix, J., Pickett, J., & Mitchell, R. (2019). Compliance, noncompliance, and the in-between: Causal effects of civilian demeanor on police officers’ cognitions and emotions. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(4), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09363-4

- Nix, J., Pickett, J., Wolfe, S., & Campbell, B. (2017). Demeanor, race, and police perceptions of procedural justice: Evidence from two randomized experiments. Justice Quarterly, 34(7), 1154–1183. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1334808

- O’brien, J. (2011). Spoiled group identities and backstage work: A theory of stigma management rehearsals. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511415389

- Olson, J., Cheung, I., & Conway, P. (2010). Deservingness, the scope of justice, and actions toward others. I. In D. Bobocel, A. Kay, M. Zanna, & J. Olson (Eds.), The psychology of justice and legitimacy (pp. 125–149). Psychology Press.

- Pickett, J., & Nix, J. (2019). Demeanor and police culture: Theorizing how civilian cooperation influences police officers. Policing: An International Journal, 42(4), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2018-0133

- Radburn, M., Stott, C., Bradford, B., & Robinson, M. (2018). When is policing fair? Groups, identity and judgements of the procedural justice of coercive crowd policing. Policing and Society, 28(6), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1234470

- Reisig, M., McCluskey, J., Mastrofski, S., & Terrill, W. (2004). Suspect disrespect toward the police. Justice Quarterly, 21(2), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820400095801

- Scheepers, D., & Ellemers, N. (2019). Social identity theory. In K. Sassenberg & M. L. W. Vliek (Eds.), Social psychology in action: Evidence-based interventions from theory to practice (pp. 129–143). SpringerLink.

- Schmitt, M., & Branscombe, N. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 167–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772143000058

- Sunshine, J., & Heuer, L. (2002). Deservingness and perceptions of procedural justice in citizen encounters with the police. In M. Ross & D. T. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 397–415). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499975.022

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worche (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). Chapter 1: The SIT of intergroup behavior. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 113–154). Nelson-Hall Publishers.

- Tankard, M. E., & Paluck, E. L. (2016). Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1), 181–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12022

- Tyler, T. R. (1997). The psychology of legitimacy: A relational perspective on voluntary deference to authorities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1(4), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0104_4

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 115–191). Elsevier.

- Tyler, T. R., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Why children follow rules: Legal socialization and the development of legitimacy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190644147.001.0001

- van Prooijen, J. W., & Lam, J. (2007). Retributive justice and social categorizations: The perceived fairness of punishment depends on intergroup status. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(6), 1244–1255. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.421

- Vermeulen, F., & Bovenkerk, F. (2012). Engaging with violent Islamic extremism: Local policies in Western European cities. Eleven International Publishers. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.376232

- Waddington, P. A., Williams, K., Wright, M., & Newburn, T. (2015). Dissension in public evaluations of the police. Policing and Society, 25(2), 212–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2013.833799

- Williamson, H., Murphy, K., & Madon, N. S. (2023). The negative implications of relative deprivation: An experiment of vicarious police contact and Muslims’ perceptions of police bias. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(1), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2058472

Appendix

Vignette Key

Officer Behavior: [procedurally just] versus [procedurally unjust]

Citizen Behavior: [RESPECTFUL] versus [DISRESPECTFUL]

A young Muslim man is driving home after attending Friday prayers when he is pulled over by a police patrol car. As he waits in his car at the side of the road a police officer approaches the driver’s side of the car with his hand on his gun. The police officer says: ‘Step out of the car and keep your hands visible’. Once the young man is out of the car the police officer states ‘I will be undertaking a search of both you and your car’.

[THE YOUNG MAN REMAINS CALM, COMPLIANT AND RESPECTFUL OF THE OFFICER. HE RESPONDS POLITELY BY SAYING ‘YES SIR, I’VE DONE NOTHING WRONG’.] or [THE YOUNG MUSLIM MAN OBJECTS, BECOMES INCREASINGLY AGITATED, RAISES HIS VOICE AND YELLS ‘WHY ARE YOU PICKING ON ME? I’VE DONE NOTHING WRONG. IT’S BECAUSE I’M MUSLIM ISN’T IT?’ THE YOUNG MAN THEN YELLS ‘SCREW YOU!’ AND STARTS TO WALK AWAY FROM THE OFFICER.]

[The Muslim man is then asked to explain where he has come from, and the police officer listens patiently.] or [The police officer raises his voice at the young man and demands to know where the man has come from. When the young man tries to explain where he has been the officer cuts him off mid-sentence.]

The police officer states ‘I have received reports of a man attempting to stab members of the public and your car fits the description of a car seen fleeing the scene. I am responding to a suspected terrorism incident. [Are you the terrorist?]’

[The police officer explains that it is his duty to ensure the public remains safe. The police officer then pats the young man down and begins his search of the car.] or [The police officer then roughly pats the young man down and begins his search of the car.] The police officer finds nothing to suggest the man was involved in any terrorism incident.

[The officer then politely asks the young man for his contact details, provides his own badge number to the young man, invites the man to ask any questions before leaving, and apologizes for causing the man any inconvenience. The officer thanks the man and says he is free to go.] or [The officer then makes a condescending comment about the man’s appearance and takes down the young man’s contact details. The police officer tells the man he has wasted his time but tells him he is free to go.]

The police officer returns to his patrol car and drives away.