?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This online survey study explored how Australian laypeople (N = 147) define alcohol intoxication using language, standard drinks, blood alcohol concentration (BAC), and symptoms. Participants used an extensive vocabulary to describe intoxication and better understood intoxication in terms of standard drinks and symptoms compared to BAC. Lay intoxication definitions and perceived alcohol-induced impairment thresholds (memory and capacity for consent) were influenced by personal characteristics (e.g. age, personal alcohol consumption). Participants rated symptom-based evidence as most useful when evaluating a person’s intoxication status in a legal setting and welcomed expert evidence. Findings can inform litigation and educational strategies that facilitate accurate engagement with alcohol intoxication in the courtroom.

Victims and witnesses are regularly under the influence of alcohol when crimes occur (Kloft et al., Citation2021). The testimony of these victims/witnesses is often the only evidence available at trial and is heavily relied upon by jurors (Schweitzer & Nuñez, Citation2018). Jurors must accurately appraise intoxication and its consequences when evaluating such testimony. The present study addresses this challenge by exploring the language, standard drinks, blood alcohol concentration (BAC), and symptoms that laypeople use to describe intoxication levels – and the contribution of personal characteristics to these definitions. Findings may help jurors assess intoxication more accurately based on lay descriptions delivered in trial settings.

Alcohol and cognition

The consumption of large amounts of alcohol leads to acute alcohol intoxication (Vonghia et al., Citation2008). Alcohol intoxication produces symptoms across domains including ‘consciousness, cognition, perception, affect, behaviour, [and] impairment’ (World Health Organisation, Citation2019, 6C40.3). summarises these symptoms with respect to BAC according to the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (AGDHAC; Citation2022b).

Table 1. Short-term symptoms experienced by healthy adults following alcohol consumption.

The cognitive effects of alcohol are especially relevant in forensic contexts. Cognitive impairment is central to complex legal questions about memory (e.g. accuracy, completeness, suggestibility) that may affect jurors’ perceptions of intoxication-related testimony.

A meta-analysis of the applied memory literature indicated that alcohol consumption prior to encoding damages the completeness – but not accuracy – of recall (Jores et al., Citation2019; see Otgaar et al., Citation2022 for an alternative interpretation). However, this effect depends on several factors including dose, cue type, and question format. Alcohol intoxication reduces recall completeness following high doses (BAC > .10), for peripheral compared to central event details, and in response to cued-recall compared to free-recall questions (Altman et al., Citation2018; Jores et al., Citation2019).

Equivalent results have been observed in the context of memory suggestibility and line-up identifications (target-present and target-absent): moderately intoxicated victims/witnesses are not more vulnerable to false information or worse at line-up identifications compared to their sober counterparts (Kloft et al., Citation2021; Oorsouw et al., Citation2019; Sauerland et al., Citation2019; Schreiber Compo et al., Citation2012). Taken together, these findings assert that intoxicated victims/witnesses cannot be automatically dismissed as unreliable; their reliability depends on a complex network of factors that require thorough scrutiny.

Potential negative effects of alcohol also extend to forensically relevant cognitive functions including planning, attention, perception, and inhibition (Fillmore, Citation2007; Vonghia et al., Citation2008). These impairments are particularly relevant in sexual assault cases involving voluntary complainant intoxication, which are common (Abbey et al., Citation2001). Judgements about the complainant’s cognitive capacity to consent are crucial in these cases and intoxication-related evidence may inform them (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018).

The reviewed literature illustrates the complicated relationship between alcohol intoxication and cognition. It demonstrates the need to assess laypeople’s (1) definitions of alcohol intoxication, and (2) thresholds for alcohol-induced cognitive impairment, to determine whether jurors can accurately engage with this complexity.

Alcohol intoxication in the criminal justice system

Criminal justice systems frequently lack consistent, informed guidelines for the management of intoxicated individuals (Crossland et al., Citation2018; Evans et al., Citation2009; Hagsand et al., Citation2022). For example, Australia lacks a widely used and legislatively endorsed legal definition of intoxication (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Thorough investigation of the meaning and effects of intoxication is rare at trial, reinforced by an assumption that intoxication is a common knowledge issue. Courts also rarely allow experts to explain alcohol intoxication. Definitions and interpretations instead come from non-specialist parties (e.g. judges, police, lawyers, victims/witnesses; Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018).

These practices introduce significant potential for the mishandling of intoxication at trial. Jurors often decide if and how a person’s intoxication status is relevant to their testimony without precise, evidence-based support (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). The integrity of this exercise relies on the assumption that laypeople are equipped to answer complicated questions about intoxication and cognition.

Jurors’ perceptions of alcohol intoxication

However, empirical research points to the opposite conclusion. Jurors cannot accurately determine a person’s degree of intoxication. Both amateurs and those with training (e.g. police, bartenders) cannot reliably identify dose-specific alcohol intoxication using behavioural observation (Monds et al., Citation2021; Rubenzer, Citation2011). Jurors also cannot accurately interpret the consequences of a person’s intoxication status after-the-fact. Jurors are unaware of the abovementioned dose-dependent relationship between alcohol and completeness vs. accuracy, leading to an indiscriminate negative view of the credibility of victim/witness’ intoxication-related memory (Crossland et al., Citation2021; Evans & Schreiber Compo, Citation2010; Martin & Monds, Citation2023).

Critically, intoxication status can directly affect verdict: defendants are less likely to be convicted when a victim/witness was intoxicated during the crime (Lynch et al., Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation2023; Wall & Schuller, Citation2000). Jurors’ interpretation of victim/witness intoxication is therefore fundamental to whether guilt or innocence is established accurately at trial.

Jury decision-making in intoxication-related cases is also influenced by jurors’ personal characteristics. For example, gender, hostile sexism, personal alcohol consumption, and moralistic beliefs about alcohol (e.g. ‘people make bad decisions when they drink’) predict jurors’ decisions in these cases (Crossland et al., Citation2021; Evans & Schreiber Compo, Citation2010; Martin & Monds, Citation2023). The current study therefore investigates the influence of personal characteristics on lay intoxication definitions and thresholds for alcohol-induced impairment.

It is surprising that courts view intoxication detection and interpretation as common knowledge given evidence of skill deficits and the intrusion of personal characteristics on these assessments (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Quilter and McNamara (Citation2018) documented a variety of measures used in courtrooms to evaluate intoxication and its effects, including verbal descriptions (e.g. ‘under the influence’), drink counts, a score of intoxication out of ten, and judges’ interpretations. The current study explores which of these methods are preferred by laypeople when assessing intoxication in a legal context, as well as openness to expert interpretation. Findings may structure future attempts to improve lay understanding of alcohol intoxication by combining preferred evidence formats with expert knowledge.

The language of intoxication

While observable and/or objective indicators of intoxication (e.g. symptoms, BAC) are important, we must also understand qualitative definitions that reflect intoxication as a subjective experience. Laypeople use an expansive terminology to describe intoxication, with substantial discrimination between moderate and severe doses (Thickett et al., Citation2013). This vocabulary defines intoxication across domains including perception, behaviour, affect, and cognition, further asserting its descriptive utility (Linden-Carmichael et al., Citation2021).

However, intoxication language is culturally bound. For example, English, Dutch, and Swedish samples primarily employed behavioural terminology (i.e. described intoxication via behaviour following alcohol consumption), while Scottish samples preferred language that focused on psychological effects (Cameron et al., Citation2000). Existing language research is from Europe and the United States. Alcohol consumption is widely accepted and promoted in Australia, and drinking to excess is normalised (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2023). These characteristics suggest that Australian intoxication language may differ from countries with less dominant drinking cultures. The current study therefore aims to provide a snapshot of dose-specific intoxication language fit for use in Australian contexts.

Quilter and McNamara (Citation2018) identified frequent use of lay intoxication language in Australian courts. It is therefore essential to understand what laypeople mean when they use this language and whether definitional consensus exists. A dose-specific summary of lay intoxication language may improve language-based assessments by highlighting their associated quantitative features.

The current study

The current study aimed to achieve the following in an Australian context:

Aim 1: To produce systematic lay definitions of intoxication in terms of language, standard drinks, BAC, and symptoms.

Aim 2: To determine the impact of personal characteristics on these definitions.

Aim 3: To explore perceived thresholds of alcohol-induced impairment in the context of memory and capacity for sexual consent.

Aim 4: To investigate laypeople’s preferred forms of intoxication evidence when evaluating a person’s intoxication status in a legal context.

We did not propose hypotheses given the exploratory nature of the study.

Method

This study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 2022/361).

Participants

Participants were recruited via social media. A brief advertisement and a link to the survey were posted in local community Facebook groups by the first author. The study was described as an investigation of ‘how Australians perceive and measure alcohol intoxication’. An a priori G*Power analysis indicated that N = 146 would be sufficient to detect and effect size of f2 = .15 with power .95 given the intended linear regressions. Participants were required to be at least eighteen; the minimum age for legal alcohol consumption in Australia. They were also required to be Australian citizens or live in Australia and be fluent in English. Participants were not reimbursed.

Participants who responded incorrectly to at least one attention check question (e.g. ‘Select [5] here’) were excluded (n = 39). Two participants were excluded for failing to meet Australian citizenship/residency requirements. The final sample comprised 147 participants (32 males, 111 females, 4 gender diverse). The average age was 31.2 years (SD = 13.3; ranging from 18 to 70 years). The following ethnic backgrounds were present: European/Caucasian (85.0%); Asian (7.5%); Mixed (4.1%), Middle Eastern (2.0%); Hispanic (.7%); Other (.7%). In total, 32.0% of participants had served alcohol at work and 38.8% had received training for this purpose. Most participants (64.4%) consumed ‘1 or 2’ standard alcoholic drinks on a typical day and 6.1% were non-drinkers.

Design

The study was a cross-sectional online survey. Key dependent variables included the language, number of standard drinks, BAC, and symptoms used to define low, moderate, and severe intoxication. Additionally, the intoxication level, number of standard drinks, and BAC at which alcohol is believed to impair memory and capacity for sexual consent. Finally, preferred forms of evidence when evaluating another person’s intoxication status in a legal setting.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity, first/preferred language, and Australian citizenship and residency status.

Intoxication language

Participants provided up to three terms they use to describe how someone feels at a low, moderate, and severe level of intoxication, respectively. These three open-ended items (‘Please provide up to three terms you would use to describe how someone feels at a [low/moderate/severe] level of intoxication’) were adapted from Linden-Carmichael et al. (Citation2021).

Standard drinks

Text-entry items asked for the number of standard drinks an adult male must consume over two hours to achieve low, moderate, and severe intoxication. These items were replicated to assess female consumption. Separate standard drink definitions for males and females were obtained due to gender differences in intoxication following consumption of the same volume of alcohol (Baraona et al., Citation2001). Participants were provided with a definition and examples of an Australian standard drink according to the Alcohol and Drug Foundation (ADF; Citation2021). For example, an Australian standard drink constitutes 100 mL of a 13.0% alcohol wine.

Blood alcohol concentration (BAC)

Participants reported the BAC they associate with low, moderate, and severe intoxication via text-entry items. They were provided with an explanation of BAC and its parameters according to the ADF (Citation2017):

Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is a measure of the amount of alcohol in a person’s bloodstream. A BAC of 0.05% means there is 0.05 g of alcohol in every 100 mL of blood.

This is the legal limit for driving in Australia.

Symptoms

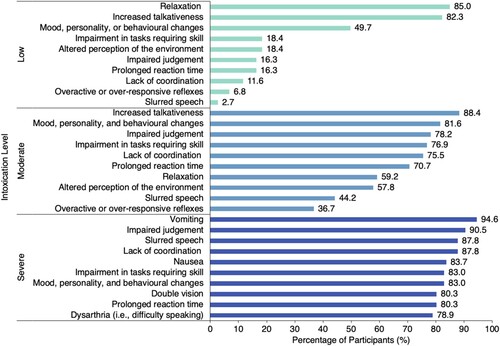

Three multi-answer items explored the symptoms associated with low, moderate, and severe intoxication. Participants selected any of the 21 response options they believed matched each intoxication level. Response options were sourced from Vonghia et al. (Citation2008) and included symptoms such as nausea, slurred speech, and impaired judgement.

Alcohol-induced impairment thresholds

Participants indicated when alcohol impairs a person’s memory for events in terms of intoxication level (low, moderate, or severe), standard drinks, and BAC. All three items were adapted from Monds et al. (Citation2022). These items were repeated to determine thresholds for impaired capacity for sexual consent.

Intoxication assessment

Participants rated the accuracy of their ability to judge their own intoxication level. Responses were delivered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not accurately at all, 7 = Extremely accurately), where higher scores indicated greater perceived accuracy. This item was replicated to explore perceptions of a typical person’s similar assessment ability.

Four items asked participants to rate the difficulty of judging another person’s degree of intoxication when they are sober and at a low, moderate, and severe level of intoxication. Responses were delivered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not difficult at all, 7 = Extremely difficult), where higher scores indicated greater difficulty. These six items will not be discussed further in this publication for brevity.

Intoxication evidence

A twelve-item measure assessed preferred evidence formats when judging a person’s intoxication status and its relevance to a legal case. Responses were delivered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not helpful at all, 7 = Extremely helpful), where higher scores indicated greater usefulness. The listed evidence was sourced from Quilter and McNamara (Citation2018) and included BAC, an expert’s interpretation, and a score of intoxication out of ten.

Alcohol stigma

Three items explored quantification of ‘too much alcohol’ via intoxication level, standard drinks, and BAC. These items will be explored in a future publication.

A four-item measure adapted from Dilevski et al. (Citation2024) assessed alcohol stigma. Responses to each statement (e.g. ‘Would you be afraid to talk to someone who consumes alcohol?’) were delivered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely not, 5 = Definitely). Item three was reverse coded so that higher scores indicated more negative attitudes toward alcohol use (i.e. greater stigma). The measure possessed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s = .74).

Personal alcohol consumption

The three-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C; Bush et al., Citation1998) assessed personal alcohol consumption. Higher total scores indicated greater alcohol consumption.

Alcohol-related work and training

Participants reported whether they had served alcohol at work and if they had received training for this purpose. Those who responded affirmatively to the second item were asked to provide the name of the training and the country it was completed in. These items were adapted from Monds et al. (Citation2022). Only alcohol-related training was included in relevant analyses given its strong positive correlation with alcohol-related work, r = .682, p < .001.

Defining intoxication and drunkenness

Text-entry items asked for brief definitions of ‘intoxication’ and ‘drunk’. These items will not be discussed further in this publication for brevity.

Procedure

The study was completed online via Qualtrics. Participants recorded informed consent and completed the demographic questionnaire. They provided terms to describe low, moderate, and severe intoxication, and reported the standard drinks, BAC, and symptoms they associate with these intoxication levels. Subsequent items explored the thresholds at which memory and capacity for sexual consent are impaired following intoxication. Participants rated the accuracy of their own and others’ ability to judge intoxication status, and the usefulness of intoxication evidence formats. They quantified ‘too much’ alcohol and completed the alcohol stigma questionnaire. The study concluded with questions exploring personal alcohol consumption, work/training experiences, and definitions of ‘intoxication’ and ‘drunk’.

Analyses

Intoxication language was coded into content-based categories.Footnote1 The first author conducted a qualitative description analysis guided by Sandelowski (Citation2000). They reviewed all intoxication language responses and categorised them according to conceptual similarities in the data (e.g. symptom-focused, slang terminology, description of the amount of alcohol consumed). Cameron et al.’s (Citation2000) coding framework was used as a starting point to guide interpretation. Categories were developed iteratively until saturation was achieved. Each category was assigned a code and codes were mutually exclusive. A second independent rater applied the coding system to 25.0% of the data and achieved = .807, indicating strong agreement.

Descriptive analyses were employed for language, standard drinks, BAC, and symptom variables according to intoxication level. Linear regressions explored the influence of personal characteristics (age; gender; personal alcohol consumption; alcohol-related training; alcohol stigma) on the standard drinks and BAC assigned to each intoxication level. Logistic and linear regressions assessed the contribution of these factors to impairment thresholds (memory and capacity for consent) in terms of intoxication level, standard drinks, and BAC. Descriptive analyses investigated preferred forms of intoxication evidence.

Results

Seventeen participants completed only the initial language-based items. Their data were included in the descriptive analysis of intoxication language (N = 164). All other analyses were performed using the final sample of 147 participants who completed the survey in full. Four participants reported their gender as ‘other’. These participants could not be included in analyses related to participant gender based on the low cell count. Their data were retained in all other analyses.

Lay definitions of dose-specific alcohol intoxication

Defining intoxication using language

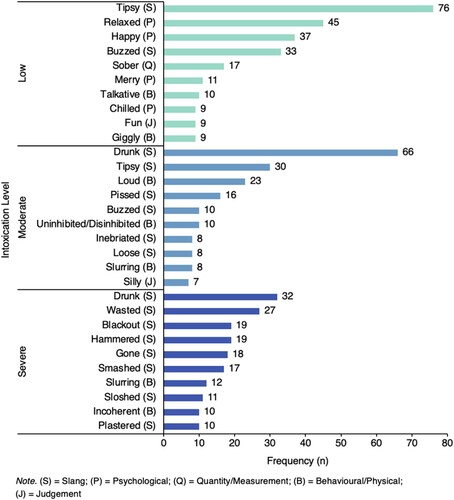

Language data were cleaned for obvious spelling errors and similar terms were collapsed (e.g. ‘blackout’ and ‘black out’). In total, 403 terms were generated to describe the intoxication spectrum. Moderate intoxication was associated with the largest vocabulary (188 terms), followed by severe and low intoxication (172 and 126 terms respectively). presents the most reported terms for each intoxication level. Seventy-one terms doubled up across intoxication levels, and eight terms were reported across the entire range of intoxication.

Intoxication language was coded according to the following categories:

Behavioural/Physical: Related to an individual’s behaviour and/or physical symptoms of intoxication (e.g. ‘stumbling’, ‘slurring’).

Psychological: Related to an individual’s cognition and emotions; psychological symptoms of intoxication (e.g. ‘mellow’, ‘emotional’).

Slang: A slang term or phrase (e.g. ‘tipsy’, ‘smashed’).

Quantity/Measurement: Related to how much alcohol a person has consumed and/or an assessment relative to sobriety (e.g. ‘had a couple’, ‘not sober’).

Identity: An identity label or description of a ‘type’ of person (e.g. ‘a lightweight’, ‘party animal’).

Judgement: A positive or negative judgement about the individual based on the observer’s experience and/or perception of them (e.g. ‘fun’, ‘worrying’).

Activity: Related to an activity or goal associated with alcohol consumption (e.g. ‘ready to party’, ‘drowning their sorrows’).

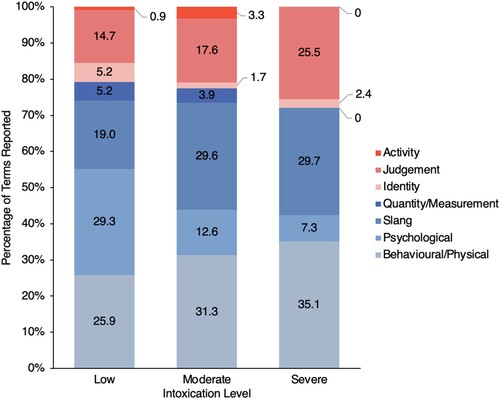

Terms lacking an interpretable meaning in the context of alcohol intoxication (e.g. ‘ARDL’, ‘dinner’) were not categorised (n = 22). presents the proportion of terms reported from each category according to intoxication level. Psychological and behavioural/physical terms were most used to describe low intoxication, while behavioural/physical and slang terms most described moderate and severe intoxication.

Defining intoxication using standard drinks

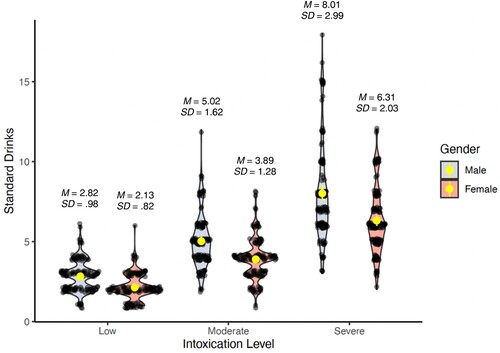

presents the distribution of standard drinks used to define each level of intoxication, separated by target gender. In general, the number of standard drinks assigned to an intoxication level increased further along the intoxication spectrum. Participants typically assigned more standard drinks to male alcohol consumption compared to female consumption.

Although most definitions were within the five to ten standard drinks range, some participants reported extreme numbers – especially for severe intoxication. The differences between the mean and median standard drinks for low, moderate, and severe male intoxication were −.18, .02, and 1.01 respectively. These differences for low, moderate, and severe female intoxication were .13, −.11, and .31 respectively.

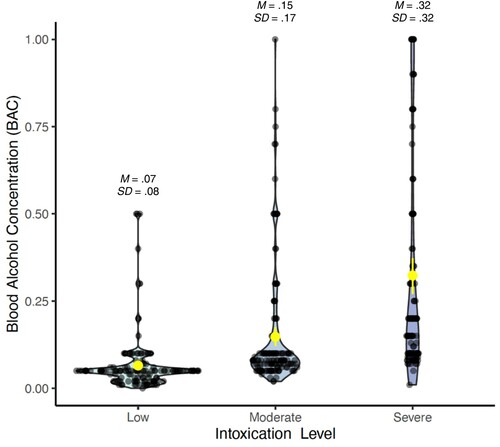

Defining intoxication using BAC

presents the distribution of BACs used to define each level of intoxication. In general, the BAC assigned to an intoxication level increased further along the intoxication spectrum. Definitions were influenced by extreme BAC values, particularly at the upper end of the intoxication spectrum. The differences between the mean and median BAC for low, moderate, and severe intoxication were .015, .067, and .173 respectively.

Defining intoxication using symptoms

presents the most selected symptoms at each level of intoxication. All symptoms except ‘relaxation’ and ‘increased talkativeness’ were selected more frequently as intoxication level increased. ‘Relaxation’ was selected less frequently as intoxication level increased, while ‘increased talkativeness’ was selected most often at moderate intoxication.

The impact of personal characteristics on lay intoxication definitions

Linear regressions explored whether the following personal characteristics influenced lay intoxication definitions in terms of standard drinks and BAC: age, gender, personal alcohol consumption, alcohol-related training, and alcohol stigma. Dependent variables were log transformed to account for extreme values.

Definitions using standard drinks

Age, gender, and personal alcohol consumption significantly predicted the relationship between intoxication level and intoxication definitions using standard drinks. and present these findings; results are interpreted below.

Table 2. Linear regressions: The impact of individual differences on intoxication definitions using standard drinks assigned to a male target.

Table 3. Linear regressions: The impact of individual differences on intoxication definitions using standard drinks assigned to a female target.

Younger participants were more likely to indicate more standard drinks were required for men to be severely intoxicated ( = −.241), and for women to be moderately or severely intoxicated (

= −.187;

= −.297). For interpretation, the first standardised coefficient should be interpreted as each standard deviation increase in age predicting a decrease of .241 (log) standard drinks required for men to reach severe intoxication.

Female participants were more likely to report that more standard drinks were required for women to experience low levels of intoxication ( = .188).

Personal alcohol consumption was also associated with differences in the number of standard drinks perceived necessary for both men and women to reach each intoxication level. Those who reported higher levels of personal alcohol consumption were more likely to indicate a higher number of standard drinks were required for men to reach low ( = .274), moderate (

= .295), and severe (

= .235) intoxication. The relevant coefficients were .197 (low), .203 (moderate), and .208 (severe) for female targets.

Definitions using BAC

presents the effects of personal characteristics on BAC-framed intoxication definitions. Older participants were more likely to report that a higher BAC was required for low intoxication ( = .196). No other personal characteristics predicted significant associations with BAC definitions for any of the intoxication levels.

Table 4. Linear regressions: The impact of individual differences on intoxication definitions using BAC.

Personal characteristics and alcohol-induced impairment thresholds

On average, participants believed alcohol begins to impair memory at a moderate level of intoxication, 6.01 standard drinks, or a BAC of .25. The average threshold for capacity to consent to sexual activity was a moderate level of intoxication, 5.50 standard drinks, or a BAC of .22.

Thresholds for impaired memory

Age, personal alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related training significantly predicted perceived thresholds for impaired memory ().

Table 5. Ordinal logistic regression: The impact of individual differences on perceived thresholds for alcohol-induced memory impairment in terms of intoxication levels.

Table 6. Linear regression: The impact of individual differences on the perceived threshold for alcohol-induced memory impairment in terms of standard drinks.

Table 7. Linear regression: The impact of individual differences on the perceived threshold for alcohol-induced memory impairment in terms of BAC.

Younger participants were more likely to report a higher number of standard drinks was required to reach the threshold of alcohol-induced memory impairment ( = −.233), as were those with higher levels of personal alcohol consumption (

= .218; ). Those without alcohol-related training were more likely to indicate a lower BAC was necessary to reach the threshold for alcohol-induced memory impairment (

= −.226; ). No other predictors were significant for these outcomes, or for intoxication level-based definitions ().

Thresholds for impaired capacity for sexual consent

Alcohol stigma and age significantly predicted perceived thresholds for impaired capacity for sexual consent ().

Table 8. Ordinal logistic regression: The impact of individual differences on the perceived threshold for alcohol-impaired capacity for sexual consent in terms of intoxication levels.

Table 9. Linear regression: The impact of individual differences on the perceived threshold for alcohol-impaired capacity for sexual consent in terms of standard drinks.

Table 10. Linear regression: The impact of individual differences on the perceived threshold for alcohol-impaired capacity for sexual consent in terms of BAC.

Participants who reported higher levels of alcohol stigma were more likely to indicate a lower intoxication level was required to reach the threshold for alcohol-impaired capacity for sexual consent (OR = .839; ). Older participants were more likely to report a higher BAC was necessary to reach the threshold for alcohol-impaired capacity for consent ( = .254; ). No other predictors were significant, including for standard-drinks based definitions of intoxication ().

Preferred forms of intoxication evidence

Participants rated the usefulness of intoxication evidence formats (e.g. cognitive symptoms, BAC, a score of intoxication out of ten) when evaluating a person’s intoxication status and its relevance to a legal case. presents means and standard deviations of these ratings, plus the proportion of participants who considered each format to be at least moderately helpful. Symptom-based evidence (e.g. cognitive, physical, and behavioural symptoms) were found most helpful, while a judge’s interpretation was viewed as least helpful. Notably, an expert’s interpretation was rated at least moderately helpful by 85.0% of participants.

Table 11. Forms of intoxication evidence ordered by perceived usefulness.

Discussion

This study established a taxonomy of the language, standard drinks, BAC, and symptoms used to define low, moderate, and severe intoxication. It also explored the contribution of personal characteristics to these definitions and perceived thresholds for alcohol-induced impairment, plus laypeople’s preferred forms of intoxication evidence.

Participants demonstrated a relatively poor understanding of standard drinks and BAC as quantitative measures because intoxication definitions using these metrics were affected by extreme values. Older participants defined intoxication levels using fewer standard drinks and lower BAC values, while those who habitually consumed more alcohol used more standard drinks to define each intoxication level.

Personal characteristics also informed perceived thresholds for alcohol-impaired memory and capacity for sexual consent. Older participants reported lower memory impairment thresholds in terms of standard drinks, and those lacking alcohol-related training reported lower thresholds in terms of BAC. Alternatively, higher personal alcohol consumption was linked to higher standard drinks thresholds for impaired memory. Older participants reported higher BAC thresholds for impaired capacity for consent, while those with greater alcohol stigma reported lower BAC thresholds.

Symptom-based evidence was rated most useful when evaluating intoxication status in a legal context. Most participants viewed an expert’s interpretation as useful, while a judge’s interpretation was viewed as least helpful.

Lay definitions of dose-specific alcohol intoxication

Defining intoxication using language

Participants used an extensive vocabulary across a variety of domains (e.g. symptoms, slang terminology) to describe the intoxication spectrum. Low intoxication was most described using psychological terms, while moderate and severe intoxication were most often defined using physical/behavioural terms. This finding aligns with the pattern of symptoms observed with increasing intoxication, as psychological effects tend to emerge first (AGDHAC, Citation2022b). Intoxication language therefore may be informed by the salience of self-experienced symptoms at each dose.

Language variation across intoxication levels implies a degree of dose specificity in intoxication terminology. Descriptive language (e.g. ‘a bit tipsy’, ‘drunk’) is frequently used to articulate intoxication in Australian courts, often with little scrutiny of what this language represents (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Linking language to dose may improve the efficacy of this currently imprecise tool. However, the utility of language is restricted as many terms were duplicated across levels (e.g. ‘drunk’ was the most common descriptor of both moderate and severe intoxication). Language-based assessments must be supplemented using other measures of intoxication and directly clarified to achieve accuracy.

Our findings also reinforce the need to engage with intoxication language through a culture-specific lens. Higher levels of intoxication were associated with larger vocabularies, while an American study documented the inverse (Linden-Carmichael et al., Citation2020). Additionally, popular Australian slang terms (e.g. ‘smashed’, ‘pissed’) were uncommon in the American sample (Linden-Carmichael et al., Citation2020). Therefore, courts should contextualise intoxication based on the culture of those delivering and interpreting intoxication language.

Defining intoxication using standard drinks

Intoxication definitions using standard drinks increased with intoxication level. Definitions describing male consumption were greater than those describing female consumption, reflecting a general understanding of gender differences in intoxication following comparable alcohol consumption (Baraona et al., Citation2001).

Quilter and McNamara (Citation2018) highlighted Australian courts’ frequent use of ‘drink counts’ to establish a person’s intoxication status during an event. These counts typically reference the type of alcohol consumed and its container (e.g. ‘two casks of white wine’) rather than standard drinks (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018, p. 179). The researchers argue that these ‘drink counts’ likely offer little more than a ‘crude indicator of the volume of alcohol consumed’ despite the appearance of specificity (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018, p. 180).

Courts may better achieve precision by estimating standard drink counts using evidence-based conversion guides (e.g. AGDHAC, Citation2020). However, the influence of factors such as drinking period, age, gender, height/weight, tolerance, and poly-substance use will complicate discussions (AGDHAC, Citation2022b). Nonetheless, evaluating intoxication using standard units offers a promising strategy to improve current practices characterised by imprecision and inconsistency (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Quantification via standard drinks provides a closer estimation of intoxication than unsystematic ‘drink counts’ if jurors, judges, and other legal actors are properly informed about this metric.

Defining intoxication using BAC

Intoxication definitions using BAC also increased with intoxication level. The average BAC associated with low intoxication (.07) reflected awareness that Australian driving laws define intoxication as BAC .05 (AGDHAC, Citation2022a). However, participants struggled with BAC beyond this benchmark as definitions were affected by extreme values. For example, the average BAC associated with severe intoxication (.32) is linked to coma and death (AGDHAC, Citation2022b). This may be related to peoples’ tendency to poorly estimate BAC and the rarity of BAC calculation in everyday life (Aston & Liguori, Citation2013; Rubenzer, Citation2011).

BAC is therefore not a fool proof solution to issues associated with subjective metrics (Rubenzer, Citation2011). It is also currently inadmissible outside driving-related cases in Australia (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Moreover, compulsory testing of victims and witnesses may convey harmful victim blaming or discourage cooperation. Finally, judges and jurors prefer ‘lay’ or observable intoxication evidence, even when a BAC result is available (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018).

Despite these challenges, we argue that BAC evidence belongs in the courtroom when available and properly contextualised. Interpretation of BAC information can improve with training, suggesting education can resolve the issues with comprehension we observed (Aston & Liguori, Citation2013). Nonetheless, we propose standard drinks are a more promising objective measure of intoxication. They are more familiar and easier to report/understand than BAC so better align with legal actors’ preference for simple intoxication evidence (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018).

Defining intoxication using symptoms

Impairment-based symptoms (e.g. impaired judgement) increased with intoxication level, while positive symptoms (e.g. relaxation) decreased. Fewer symptoms were associated with low intoxication compared to moderate and severe intoxication. These findings reflect an understanding that the negative effects of alcohol increase with dose (Dry et al., Citation2012).

Quilter and McNamara (Citation2018) documented strong reliance on visual cues (i.e. subjective qualitative accounts of how a person looked/behaved before, during, or after a crime) in Australian courts, highlighting an assumption that intoxication can be reliably observed. However, police, bartenders, and laypeople cannot consistently identify a person’s intoxication using symptoms (Rubenzer, Citation2011). Additionally, no symptom has been linked to a specific degree of intoxication without substantial variation between individuals (Rubenzer, Citation2011). Symptoms also depend on whether intoxication is rising or falling and can be caused by other substances or health conditions (Kloft et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation1993).

However, courtroom assessments of alcohol intoxication should not exclude symptom-based evidence, especially given the preference for this information (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). How an individual felt while intoxicated may be the only information available in cases where the person cannot remember how much alcohol they consumed and were not breathalysed. Instead – like each of the strategies discussed above – courts should cautiously evaluate symptom-based evidence alongside other sources of information when determining intoxication and its consequences.

Personal characteristics and lay intoxication definitions

Personal characteristics influenced many of the lay definitions discussed above, suggesting that personal experience anchors conceptions of intoxication. Older participants assigned fewer standard drinks to severe male intoxication, and moderate and severe female intoxication. Alternatively, participants who habitually consumed more alcohol defined moderate and severe intoxication with more standard drinks across male and female targets. Both effects may be informed by tolerance: sensitivity to alcohol generally increases with age and decreases with persistent alcohol use (Elvig et al., Citation2021; Meier & Seitz, Citation2008).

Personal characteristics exerted far less influence over intoxication definitions using BAC. This may be a product of the misunderstanding of BAC discussed above. Future research should re-examine these relationships following BAC education.

Australian courts regularly depend on laypeople to evaluate an individual’s intoxication status and its legal consequences (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). This process may amplify the role of personal characteristics and create strategic opportunities for lawyers. Jurors whose personal characteristics imply a favourable interpretation of intoxication evidence could be privileged during voir dire. Additionally, awareness of a victims/witness’ characteristics could be used to enhance their delivery of intoxication evidence at trial.

Alcohol-induced impairment thresholds

Memory

Participants believed alcohol impairs memory at a moderate level of alcohol intoxication, 6.01 standard drinks, or a BAC of .25. Age and personal alcohol consumption informed standard drink thresholds, likely driven by the same tolerance effects discussed above (Elvig et al., Citation2021; Meier & Seitz, Citation2008). Participants with alcohol-related training (e.g. Responsible Service of Alcohol accreditation) labelled the threshold for impaired memory using higher BACs. This finding may reflect a basic acknowledgement among trained individuals that memory impairment begins at higher BACs than the average layperson expects (Jores et al., Citation2019). However, alcohol impairment occurs at BAC levels much lower than .025. Thus, trained individuals still misinterpret BAC despite better understanding the overall trend of alcohol-induced memory impairment.

Capacity for sexual consent

Participants reported the threshold for impaired capacity for sexual consent as a moderate level of intoxication, 5.50 standard drinks, or a BAC of .22. Greater alcohol stigma predicted lower impairment thresholds when using descriptive labels (i.e. low, moderate, or severe). The belief that alcohol is ‘bad’ may encourage people to view alcohol as more harmful in sexual situations, lowering the perceived level of intoxication required to damage a person’s capacity for consent.

Impairment thresholds in the courtroom

Questions about impairment are central to legal proceedings and may inform how intoxication evidence is presented and interpreted (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). For example, impairment thresholds might determine whether a person’s testimony, line-up identification, or sexual assault claim is viewed as credible (Evans & Schreiber Compo, Citation2010; Lynch et al., Citation2013; Martin & Monds, Citation2023). Courts should acknowledge the potential contribution of personal characteristics and minimise erroneous decision-making by providing context-specific, evidence-based information about alcohol and impairment.

Preferred forms of intoxication evidence

Participants viewed symptom-based evidence as most helpful when evaluating a person’s intoxication status and its legal relevance, and a judge’s interpretation as least helpful. The preference for symptom information aligns with common questions in intoxication-related trials (e.g. Has alcohol damaged testimony credibility? Could an intoxicated complainant consent to sexual activity? How did an intoxicated person behave before, during, and after an event?) (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018).

Participants welcomed expert interpretation, indicating that existing reluctance to utilise expert intoxication evidence is unfounded (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Additionally, judges’ interpretations were least valued. This contradicts current practice: judges tend to believe they can accurately articulate and interpret intoxication despite lacking expertise (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). Targeted, serviceable education for judges may address this issue.

These findings reflect preferences rather than use. The evidence formats perceived as most helpful on paper may diverge from those preferred at trial. For example, judges’ interpretations may become more convincing when jurors rely on judges to help them navigate real legal complexities (Cordell & Keller, Citation1993). Moreover, preferred formats may differ from those that actually help laypeople to make informed decisions. Nonetheless, these results offer valuable preliminary insights into the most compelling forms of intoxication evidence and should inform future education strategies.

Limitations and future directions

Not every person will define intoxication in the same way. Australian courts are already hampered by a vague approach to intoxication, so it would be imprudent to recommend a one-size-fits-all application of our findings (Quilter & McNamara, Citation2018). The current study also remained abstract rather than referencing a specific case. Case details (e.g. crime type) can affect how people evaluate an individual’s intoxication status and their subsequent decision making (Bieneck & Krahé, Citation2011). Additionally, target factors that affect intoxication (e.g. drinking period, height/weight, tolerance) were not provided (AGDHAC, Citation2022b). These qualifications frame our findings as consensus-based guidelines for the articulation and interpretation of intoxication, rather than rigid standards. Context, specificity, and expert scientific/medical guidance are essential for accurate engagement with intoxication in the courtroom.

We must acknowledge the limitations of the convenience sample used. The study advertisement was posted in a range of Australian local community Facebook groups by the first author. Group selections or incidental associations with the author may have affected generalisability. Nonetheless, the final sample was diverse and successfully yielded demographic-based effects.

Additionally, the alcohol stigma measure may have been too ambiguous. For example, the measure did not specify a specific level of intoxication or context for the interaction. Future research should utilise a more detailed measure to accurately probe stigma-based effects.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that laypeople use a range of measures to define dose-specific alcohol intoxication and perceived thresholds for alcohol-impaired memory and capacity for consent. These definitions and thresholds were informed by personal characteristics. Awareness of the connection between personal characteristics and conceptions of intoxication may benefit lawyers during victim/witness preparation, jury selection, and oral argument. Participants welcomed many forms of intoxication evidence, especially symptom-based information, and expert interpretation. This reflects awareness that alcohol intoxication is complex and multi-factorial and asserts expert intoxication evidence belongs in the courtroom (Rubenzer, Citation2011).

Our findings have several implications within a legal context. Bartenders and friends/drinking partners are often ‘pre-witnesses’ to a crime: they might make decisions about how much alcohol to give a person and/or observe their state of intoxication. As such, these groups are crucial both in the lead-up to and following an alcohol-related crime because they witness the alcohol consumption. People present during a victim/witness’ drinking episode might be asked to provide an intoxication assessment to police and/or in the courtroom – and jurors highly value this evidence (Martin et al., Citation2023). It is essential we understand what these lay assessments mean with a high degree of specificity, highlighting the utility of our results.

Jurors also value expert guidance when making judgements about intoxication. Therefore, experts should be heavily involved in intoxication-related cases. However, they must manage the complex relationship between alcohol and cognition to facilitate juror comprehension. The current study established a lay taxonomy of intoxication across multiple domains that experts should utilise when communicating with a jury. We have since found that delivering intoxication evidence using these familiar metrics and definitions can improve jury decision-making: mock jurors could differentiate between the dose-specific effects of alcohol on memory in terms of perceived victim/witness credibility, cognitive impairment, and verdict decisions (Martin et al., Citation2023).

In summary, no single evidence format is free from limitations or will be available in every case. Therefore, courts should strive for accuracy by (1) using as many information sources as possible, and (2) utilising evidence-based expert guidance, to corroborate assessments of intoxication and its legal consequences.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Materials and Preregistered. The materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XG5W3 and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSD.IO/MXNW.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

1 Codebook available on Open Science Framework.

References

- Abbey, A., Zawacki, T., Buck, P. O., Clinton, A. M., & McAuslan, P. (2001). Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(1), 43–51.

- Alcohol and Drug Foundation. (2017). Blood alcohol levels. https://adf.org.au/insights/what-is-a-standard-drink/.

- Alcohol and Drug Foundation. (2021). What is a standard drink? https://adf.org.au/insights/what-is-a-standard-drink/.

- Altman, C. M., Schreiber Compo, N., McQuinston, D., Hagsand, A. V., & Cervera, J. (2018). Witnesses’ memory for events and faces under elevated levels of intoxication. Memory (Hove, England), 26(7), 946–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1445758

- Aston, E. R., & Liguori, A. (2013). Self-estimation of blood alcohol concentration: A review. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 1944–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.017

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2020). Standard drinks guide. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/alcohol/about-alcohol/standard-drinks-guide.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2022a). Alcohol laws in Australia. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/alcohol/about-alcohol/alcohol-laws-in-australia.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2022b). What are the effects of alcohol? https://www.health.gov.au/topics/alcohol/about-alcohol/what-are-the-effects-of-alcohol.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol/alcohol-tobacco-other-drugs-australia/contents/drug-types/alcohol#consumption.

- Baraona, E., Abittan, C. S., Dohmen, K., Moretti, M., Pozzato, G., Chayes, Z. W., Schaefer, C., & Lieber, C. S. (2001). Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 25(4), 502–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02242.x

- Bieneck, S., & Krahé, B. (2011). Blaming the victim and exonerating the perpetrator in cases of rape and robbery: Is there a double standard? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(9), 1785–1797. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510372945

- Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

- Cameron, D., Thomas, M., Madden, S., Thornton, C., Bergmark, A., Garretsen, H., & Terzidou, M. (2000). Intoxicated across Europe: In search of meaning. Addiction Research, 8(3), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350009004423

- Cordell, L. H., & Keller, F. O. (1993). Pay no attention to the woman behind the bench: Musing of a trial court judge. Indiana Law Journal, 68, 1199–1207.

- Crossland, D., Kneller, W., & Wilcock, R. (2018). Intoxicated eyewitnesses: Prevalence and procedures according to England’s police officers. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(10), 979–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1474216

- Crossland, D., Kneller, W., & Wilcock, R. (2021). Mock juror perceptions of intoxicated eyewitness credibility. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 38, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09430-5

- Dilevski, N., Cullen, H. J., van Golde, C., Flowe, H. D., Paterson, H. M., Takarangi, M. K. T., & Monds, L. A. (2024). Juror perceptions of bystander and victim intoxication by different substances. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, (Advance online publication). https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548241227543

- Dry, M. J., Burns, N. R., Nettelbeck, T., Farquharson, A. L., & White, J. M. (2012). Dose-related effects of alcohol on cognitive functioning. PLoS One, 7(11), e50977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050977

- Elvig, S. K., McGinn, M. A., Smith, C., Arends, M. A., Koob, G. F., & Vendruscolo, L. F. (2021). Tolerance to alcohol: A critical yet understudied factor in alcohol addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 204, 173155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2021.173155

- Evans, J. R., & Schreiber Compo, N. (2010). Mock jurors’ perceptions of identifications made by intoxicated eyewitnesses. Psychology, Crime & Law, 16(3), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802612890

- Evans, J. R., Schreiber Compo, N., & Russano, M. (2009). Intoxicated witnesses and suspects: Procedures and prevalence according to law enforcement. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 15(3), 194–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016837

- Fillmore, M. T. (2007). Acute alcohol-induced impairment of cognitive functions: Past and present findings. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 6(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2007.6.2.115

- Hagsand, A. V., Pettersson, D., Evans, J. R., & Schreiber Compo, N. (2022). Police survey: Procedures and prevalence of intoxicated witnesses and victims in Sweden. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2022a3

- Jores, T., Colloff, M. F., Kloft, L., Smailes, H., & Flowe, H. D. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of acute alcohol intoxication on witness recall. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(3), 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3533

- Kloft, L., Monds, L. A., Blokland, A., Ramaekers, J. G., & Otgaar, H. (2021). Hazy memories in the courtroom: A review of alcohol and other drug effects on false memory and suggestibility. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 124(1), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.012

- Linden-Carmichael, A. N., Allen, H. K., & Lanza, S. T. (2021). The language of subjective alcohol effects: Do young adults vary in their feelings of intoxication? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(6), 670–678. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000416

- Linden-Carmichael, A. N., Masters, L. D., & Lanza, S. T. (2020). “Buzzwords”: Crowd-sourcing and quantifying U.S. young adult terminology for subjective effects of alcohol and marijuana use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28(6), 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000344

- Lynch, K. R., Wasarhaley, N. E., Golding, J. M., & Simcic, T. (2013). Who bought the drinks? Juror perceptions of intoxication in a rape trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(16), 3205–3222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513496900

- Martin, C. S., Earleywine, M., Musty, R. E., Perrine, M. W., & Swift, R. M. (1993). Development and validation of the biphasic alcohol effects scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 17(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x

- Martin, E., & Monds, L. A. (2023). The effect of victim intoxication and crime type on mock jury decision-making. Psychology, Crime & Law. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2023.2176498

- Martin, E., van Golde, C., & Monds, L. A. (2023). Tipsy testimonies: The effect of alcohol intoxication status, crime role, and juror characteristics on mock jury decision-making. PsyArXiv Pre-Prints. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/v4en3.

- Meier, P., & Seitz, H. K. (2008). Age, alcohol metabolism, and liver disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 11(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f30564

- Monds, L. A., Cullen, H. J., Kloft, L., van Golde, C., Harrison, A. W., & Flowe, H. (2022). Memory and credibility perceptions of alcohol and other drug intoxicated witnesses and victims of crime. Psychology, Crime & Law, 28(8), 820–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1962871

- Monds, L. A., Riodan, B. C., Flett, J. A. M., Conner, T. S., Haber, P., & Scarf, D. (2021). How intoxicated are you? Investigating self and observer intoxication ratings in relation to blood alcohol concentration. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(7), 1173–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13241

- Oorsouw, K., Broers, N. J., & Sauerland, M. (2019). Alcohol intoxication impairs eyewitness memory and increases suggestibility: Two field studies. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(3), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3561

- Otgaar, H., Riesthuis, P., Ramaekers, J. G., Garry, M., & Kloft, L. (2022). The importance of the smallest effect size of interest in expert witness testimony on alcohol and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 980533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.980533

- Quilter, J., & McNamara, L. (2018). The meaning of “intoxication” in Australian criminal cases: Origins and operation. New Criminal Law Review, 21(1), 170–207. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2018.21.1.170

- Rubenzer, S. (2011). Judging intoxication. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.935

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Sauerland, M., Broers, N. J., & Van Oorsouw, K. (2019). Two field studies on the effects of alcohol on eyewitness identification, confidence, and decision times. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(3), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3493

- Schreiber Compo, N., Evans, J. R., Carol, R. N., Villalba, D., Ham, L. S., Garcia, T., & Rose, S. (2012). Intoxicated eyewitnesses: Better than their reputation? Law and Human Behavior, 36(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093951

- Schweitzer, K., & Nuñez, N. (2018). What evidence matters to jurors? The prevalence and importance of different homicide trial evidence to mock jurors. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 25(3), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2018.1437666

- Thickett, A., Elekes, Z., Allaste, A., Kaha, K., Moskalewicz, J., Kobin, K., & Thom, B. (2013). The meaning and use of drinking terms: Contrasts and commonalities across four European countries. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 20(5), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2013.798263

- Vonghia, L., Leggio, L., Ferrulli, A., Bertini, M., Gasbarrini, G., Addolorato, G., & Alcoholism Treatment Study Group. (2008). Acute alcohol intoxication. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 19(8), 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2007.06.033

- Wall, A. M., & Schuller, R. A. (2000). Sexual assault and defendant/victim intoxication: Jurors’ perceptions of guilt. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02315.x

- World Health Organisation. (2019). 6C40.3 alcohol intoxication. In International statistical classification of diseases and health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1339202943