ABSTRACT

Everyday users of public places are vital crime guardians because they are often present when formal security is absent. In this study, we use survey data from 940 Australian residents to examine the influence of place type, place attachment and perceived social cohesion on responses to disorder in public places. We find that individuals are more likely to intervene directly in disorder problems at places that are associated with a specific activity and have a defined in-group of participants (e.g. places of worship, health clubs) compared to consumption places (e.g. shops) or open public parks. We also find that perceived social cohesion can reduce the likelihood of guardianship-in-action when place attachment is high. We suggest that in public places the perception that other individuals are capable and willing to intervene may lead to diffusion of responsibility.

Introduction

Public places play an important role in our communities. Beyond their primary function places such as parks, transport stations and shops provide opportunities for social interaction, sense of community and belonging to develop (Felder & Pignolo, Citation2018; Zahnow et al., Citation2022). Despite the social and functional benefits of public places evidence shows that popular public places like shopping malls (Ceccato et al., Citation2018) and parks (Marquet et al., Citation2020; Taylor et al., Citation2019) can also generate crime (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1993a). Crime generators are places that bring large numbers of people together to engage in everyday legitimate activities but in doing so generate opportunities for crime to occur (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1995). While formal guardians such as police can provide some protection at potential crime generators everyday users are essential to preventing and reporting public crime and disorder problems.

Everyday users of public places are vital crime guardians because they are often present when formal guardians are absent and their mere visibility can deter would be offenders (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979; Hollis-Peel et al., Citation2011; Leclerc & Reynald, Citation2017). Guardianship varies in intensity from mere presence to active intervention which occurs when everyday users of public places act to prevent or respond to a crime event by consciously monitoring, proactively inhibiting and responding to unwanted behaviours (Hollis-Peel et al., Citation2011; Reynald, Citation2009, Citation2010). To date, the majority of empirical work on what motivates individuals to act as crime guardians has been conducted in residential or institutional settings (Lockitch et al., Citation2022). Studies show that active guardianship is more likely to occur in affluent, ethnically homogenous neighbourhoods (Wickes et al., Citation2017) and that sense of responsibility (Reynald, Citation2010), place attachment and social cohesion (Fledderjohann and Johnson, Citation2012) can encourage willingness to intervene when deviance occurs or there is a visible threat to neighbourhood social norms and conditions. Similarly, studies that examine bystander intervention note that social cohesion, among bystanders present during a crime in progress, may moderate the effect of bystander quantity such that the presence of more bystanders who are known to each other can lead to collective action (Levine et al., Citation2002). That is, while the number of bystanders alone can inhibit intervention through the diffusion of responsibility and audience inhibition (Latané & Darley, Citation1970), social connection between bystanders may overcome these problems if the behaviour modelled by co-present others supports the intervention.

Taken together, the guardianship and bystander intervention literature establish the role of social context in shaping intervention action but is yet to focus on the extent to which intervention: (1) varies across different physical place settings, and (2) may be influenced by routine activity spaces, territorial cognitions and place attachment (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). Guardianship action may be more likely at physical places where boundaries are clear, social roles are defined and behavioural expectations are explicit (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). When behavioural expectations are ambiguous individuals must rely more heavily on social influence and behaviours modelled by other individuals who are present. Some places, like places of worship or fitness centres, are sites of regular social gatherings between group members who come together with a shared purpose (Zahnow et al., Citation2022). These places, akin to Oldenburg’s third places encourage a sense of social cohesion and shared ownership which may stimulate the sense of responsibility for active guardianship (Kim & Hipp, Citation2022). Other places are truly public such as parks and transit stations. At these places, propensity for active guardianship may be lower because behavioural expectations, sense of ownership and situational responsibility for guardianship are more ambiguous (Altman, Citation1975; Critelli & Keith, Citation2003).

At places where people routinely visit they may display higher guardianship capacity and willingness because familiarity within their routine activity space will afford them greater awareness of behavioural expectations, social norms and the usual social milieu (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1993a). Thus, similar to the capacity for familiarity within activity spaces to enhance offending capacity among those with criminal motivation (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1995), place familiarity within activity spaces may enhance place attachment, territorial cognitions and guardianship capacity for individuals who do not have criminal intentions.

In this study, we draw on a survey of 940 Australians to examine when and where individuals engage in active guardianship at places within their routine activity spaces. We address two research questions: (1) what is the influence of place type, place attachment and perceived social cohesion on the propensity to enact guardianship in response to disorder at frequently visited places? (2) to what extent does the social context (measured as perceived social cohesion) moderate the influence of place attachment on the propensity to enact guardianship in response to disorder at frequently visited places?

In addressing these research questions, we extend current understandings of guardianship-in-action by incorporating concepts from the bystander intervention literature to theorise how the social context in public places may impede willingness to intervene. Adopting this integrated lens, we move beyond residential settings to assess the contextual conditions in which individuals enact guardianship in public places within their routine activity space. Our findings provide important insights for planning and regulating safe urban environments. Given more than half of the global population lives in urban settings (United Nations, Citation2018), understanding capacity for crowd-sourced safety is vitally important to inform low-cost, resource-efficient solutions to public crime and disorder problems. We begin by providing an overview of research on guardianship-in-action, territoriality, and bystander intervention. This is followed by an outline of the data, methods, and results. We finish with a discussion of the key findings of this research and highlight implications for theory and practice.

Routine activity space and guardianship

A large proportion of everyday activities are repeated over time such that individuals develop a routine activity space comprising activity nodes where people engage in daily activities and the paths they use to travel between them (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1993b; Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1981). In addition to home and work most people visit numerous regular activity nodes during their daily lives including the grocery store, fitness centre, park, or café. Some activity nodes are also crime generators because they draw in large numbers of people for legitimate purposes but in doing so, they bring motivated offenders into contact with potential crime targets (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1993a). Studies demonstrate various types of places can be crime generators including but not limited to bars (Pridemore & Grubesic, Citation2013), grocery stores, restaurants (Bernasco & Block, Citation2011; Block et al., Citation2004) and parks (Groff & McCord, Citation2012). Yet not all activity generators are associated with high levels of crime.

Research demonstrates a great deal of variation in the extent to which crime actually occurs at activity nodes. Scholars note the neighbourhood context can intensify or attenuate perceived opportunities for crime at activity nodes and point to social cohesion in the environmental backcloth as a protective factor against crime (Tillyer et al., Citation2021). Similarly, the social context at the activity node itself may influence opportunities for crime and disorder. Specifically, the presence and action of capable and willing guardians may minimise crime and deter would-be offenders.

Crime pattern theory suggests that motivated individuals commit offences within their routine activity spaces because they are familiar with target availability in these areas (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1993a). Given that studies in residential settings have shown that place attachment and social cohesion enhance guardianship-in-action we might expect that for those without criminal motivations place-familiarity and perceived social connection within routine activity spaces will facilitate guardianship (Felder, Citation2021). While crime pattern theory has been applied to examine the influence of routine activity space and visitation frequency on patterns of offending (Menting et al., Citation2019), research has yet to consider how routine activity spaces and visitation frequency may influence patterns of guardianship.

Of the three components that comprise a crime event: a motivated offender; target and guardian; the guardian has attracted the least scholarly attention. According to Hollis-Peel et al. (Citation2011, p. 55), a guardian is an individual who:

… keeps an eye on the potential target of crime, [and] includes anybody passing by, or assigned to look after people or property … . usually refers to ordinary citizens, not police or private guards … going about their daily lives but providing, by their presence, some degree of security.

In the original conceptualisation of routine activity theory guardianship refers to the presence of individuals as deterring crime through visibility and the threat of potential detection alone (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979). However, contemporary conceptualisations of guardianship delineate between the presence of potential guardians and active guardianship which entails conscious behaviours across a continuum of intensity from monitoring to directly intervening in a crime in progress (Hollis-Peel et al., Citation2011; Reynald, Citation2011, Citation2018).

To date, studies on individual guardianship behaviour have focused almost exclusively on residential settings (for exception see, Lockitch et al., Citation2022). In the context of the home Reynald (Citation2010) shows that guardianship intensity varies from presence to direct intervention dependent on self-efficacy, sense of responsibility and place attachment (see also Reynald, Citation2011; Reynald & Elffers, Citation2009). Other scholars draw attention to the socio-demographic profile of the neighbourhood showing that residents in affluent, homogenous neighbourhoods are more likely to intervene directly in crime and disorder compared to those living in more disadvantaged areas (Wickes et al., Citation2017). While individuals who live in socially cohesive neighbourhoods report greater willingness to act as a guardian (Reynald, Citation2009, Citation2010; Wickes et al., Citation2017), higher levels of generalised trust and self-esteem are associated with a lower propensity to intervene (Reynald & Moir, Citation2019).

Most of the empirical research on guardianship in public places focuses on population presence and absence (Felson & Boivin, Citation2015; Solymosi, Citation2019; Wo et al., Citation2022; Zahnow, Citation2023) without accounting for individual variations in guardianship intensity or factors that motivate intervention. For example, studies show the presence of potential guardians at the aggregate level measured as exposed and ambient population (Song et al., Citation2023), transit users (Zahnow, Citation2023), mall attendees (Felson & Boivin, Citation2015) and through twitter activity (Hipp et al., Citation2019; Solymosi, Citation2019; Wo et al., Citation2022), may deter some types of crimes but findings are inconsistent across crime and place types.

Bystander intervention

The bystander intervention scholarship provides some insights into the social and situational characteristics that influence an individual’s propensity to intervene in a crime in progress outside of the residential environment (Latané & Darley, Citation1970). Similar to the process of active guardianship (Reynald, Citation2010), bystander intervention requires individuals to first notice an event and recognise it as a problem in progress. However, bystander intervention differs from guardianship because it considers the influence of social contexts on an individual’s decision to intervene after they see and recognise offending behaviour.

The bystander effect suggests that a combination of diffusion of responsibility (i.e. people feel less responsible when others are present), audience inhibition (i.e. fear of negative evaluation by others) and social influence (i.e. look to the behaviour of others to consolidate social norms) can work to discourage individuals from intervening in crime and disorder when other bystanders are present (Fischer et al., Citation2006; Fischer et al., Citation2011; Latané & Darley, Citation1970; Levine & Crowther, Citation2008). Findings suggest that as the number of bystanders increases the propensity for any one individual to actively intervene reduces. However, Levine and colleagues (Citation2002) note that it is not only the number of fellow bystanders present but how the social context is perceived that influences an individuals’ propensity to intervene (Banyard et al., Citation2019; Levine & Manning, Citation2013). That is, social connection to fellow bystanders and perceived social cohesion may moderate the link between bystander presence and propensity for active intervention (Levine & Crowther, Citation2008).

Critics of the bystander effects literature have noted that the three explanatory processes: diffusion of responsibility; audience inhibition, and social influence, deal only with the social costs of helping and the social modelling of not helping without considering the costs of not helping and ignoring situations where fellow bystanders model intervention behaviour (Critelli & Keith, Citation2003). In response to these critiques, contemporary empirical studies have extended the concept of the bystander effect to highlight the positive influence of social connections between bystanders and positive behavioural modelling on instigating collective action in response to a problem. A study examining college students propensity to intervene in a violent event found that social cohesion moderated the effect of group size by eroding perceived anonymity and motivating students to conform to group-based norms that encouraged collective intervention (Rutkowski et al., Citation1983). Similarly, Banyard (Citation2008) found that college students who reported a greater sense of community also reported higher intentions to help in emergency situations and research examining security camera footage reported that witnesses to violent events were more likely to intervene when they were socially connected to other bystanders and/or the victim (Liebst et al., Citation2019). Yet, other studies find that social cohesion can exacerbate the diffusion of responsibility. Linning and Barnes (Citation2022) found that higher perceptions of social cohesion were associated with lower odds that bystanders would report crimes to the police. They suggested that in socially cohesive neighbourhoods residents assume someone else will report incidents to the police and are less likely to do so themselves (Linning & Barnes, Citation2022). Taken together these findings suggest that the association between social context and intervention may depend on the sense of social cohesion or identification with other bystanders rather than simply the number of people present (Rutkowski et al., Citation1983).

Place attachment

Studies also demonstrate the importance of place familiarity and psychological connection to place for generating a sense of ownership and responsibility that motivates active guardianship (Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019; Kuo et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020; Vaske & Kobrin, Citation2001). Place attachment is a sense of connection to a place that comprises two components: place identity and place dependence (Lewicka, Citation2010). Place dependence refers to the functional role of the place in the person’s life while place identity relates to feelings of attachment, connection and psychological sense of ownership. Place attachment varies across types of public places dependent on frequency and duration of occupancy and individualised place meaning (blinded for review). Stronger place attachment develops at places where individuals routinely spend time and where they feel a sense of congruence between self-identity and place characteristics (Lewicka, Citation2011). Place-identity is an essential element of psychological ownership and sense of responsibility for place which can manifest itself into guardianship actions (Kuo et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020). Students who report strong school connectedness are more likely to feel a sense of responsibility for reporting incidents of bullying (Ahmed, Citation2008) and retail employees are more likely to actively engage in shoplifting prevention when they feel a sense of psychological ownership towards their workplace (Potdar et al., Citation2021). In a study of park visitors, Li and colleagues (Citation2020) found that when visitors identified strongly with park characteristics they were more likely to participate in pro-social behaviours to protect the environment such as picking up litter and telling other visitors to stay on the tracks (Li et al., Citation2020).

The current study

Public places differ from residential environments in two ways and that may have implications for guardianship. First, the social context and therefore perceived cohesion is more fluid in public places, and this can generate behavioural ambiguity and individual anonymity. Second while individuals have one primary home neighbourhood, when choosing public places they can select from any number of places that provide the same functional features. This can impede place dependence and place attachment. Yet, at some public and semi-public places that individuals visit frequently, they may develop strong place attachment (i.e. place dependence), familiarity with social norms and establish social connections.

In this study, we draw on survey data from 940 Australian adults to estimate the influence of place type, place attachment and perceived social cohesion on individuals’ propensity to actively intervene when they witness disorder problems at places they frequent within their routine activity spaces. We also assess the moderating effect of social cohesion on the association between place attachment and guardianship action. We hypothesise that at places within individuals’ routine activity spaces, high social cohesion in combination with high place attachment will impede the propensity to intervene by exacerbating the effect of social factors such as diffusion of responsibility, audience inhibition and social influence, as purported by the bystander literature (Latané & Darley, Citation1970). Yet, when the individual does not have a strong attachment to place and is relatively anonymous in the social setting then social factors purported to effect bystanders such as audience inhibition and diffusion of responsibility may be less influential and instead, as reported in studies of active guardianship in neighbourhood settings (Reynald, Citation2010), perceived social cohesion may be positively associated with propensity to intervene.

Methods and data

This study draws on self-report survey data collected online and via telephone from a randomly recruited representative panel of Australian adults. The survey asks participants about places, people, and social processes in their local neighbourhood with specific reference to crime and responses to crime in public and shared places in the community. The specific variables used in this study are outlined in detail below. The survey was conducted by the Social Research Centre between 15 and 28 March 2022. Participants are 1015Footnote1 active Life in Australia™ members (https://srcentre.com.au/our-research#life-in-aus). Panel members were invited to complete the survey used in this study via email, SMS, or telephone call2. A total of 1400 active panel members were invited to participate in the survey, 1015 (72.5%) completed the survey, 26.6% were unable to be contacted and 0.9% refused. On average it took respondents 5.7 min to self-complete the survey online compared to an average of 21.5 min for individuals completing the survey over the phone.Footnote2 This study was approved by the University of XXX Ethics Review Board (number removed for peer review).

The social research centre life in Australia panel

The Social Research Centre’s Life in Australia™ panel comprises a representative sample of Australian adults who were recruited to take part in surveys on a regular basis. Established in 2016, the original members were recruited using a dual-frame random digit dialling (RDD) sample design with a 30:70 split between the landline RDD sample frame and mobile phone RDD sample frame. The sample was refreshed annually between 2018 and 2021 with a proportion of members being retired each year and new members recruited. This recruitment used a combination of methodologies: G-NAF (Geocoded National Address File) sample frame and push-to-web and mobile RDD sample frame. Life in Australia™ includes people both with and without internet access. Those without internet access or those who are not comfortable completing surveys over the internet are able to complete surveys by telephone. Participants receive a small incentive for joining the panel and additional incentives for each survey they complete (value of $10).

Dependent variable

Active guardianship. Participants were asked to nominate one ‘place in their local neighbourhood other than home or work that they frequently go to as part of their routine activities.’ To capture individuals’ responses to crime and disorder at their nominated place, we first asked them to report on a scale ranging from no problem (1) to a very big problem (5), how much of a problem five disorder issues were at their nominated place and secondly, what they did in response to the problem. The issues include: (a) young people being a nuisance, hanging out and getting into trouble, (b) vandalism and graffiti, (c) traffic problems like speeding or road rage, (d) people using alcohol or drugs in public, (e) people being abused, attacked, or harassed (including staff). The response options include (a) nothing (b) left the place (c) showed I disagreed non-verbally, (d) asked the person to change their behaviour (e) alerted staff (f) alerted police (g) did not witness the problem in progress. We recoded the responses into four categories that represent the different intensities of guardianship: (1) did not see any problems (2) saw problems took no action (3) responded directly (4) alerted police or staff. The dependent variable in the study is the participants’ modal response across the five disorder problems at their nominated place. The reference category in the multinomial logistic regression models is a category (2) saw problems took no actions.

Independent variables

Place types. To generate a variable capturing place types we categorised the places that individuals nominated as the place in the neighbourhood, aside from work or home, that they frequented as part of their routine activities. We assigned places into four types: (1) public places; (2) large consumption places; (3) local consumption places; and (4) socialisation places. Our categorisation of places was based on the average duration of visitation and opportunities for social experiences in the places nominated (Piekut & Valentine, Citation2017). In our study, public places are those that are theoretically accessible to all members of the community at all times of the day (Piekut & Valentine, Citation2017). These places include parks and playgrounds, dog parks, bike and walk paths and beaches. Public places represent Altman’s (Citation1975) public territory. Given that parks, nature strips and streets are all at once ‘everybody’s property and nobody’s property’ (Scott, Citation1955, p. 116), public places may be associated with a lower propensity for guardianship due to higher diffusion of responsibility and ambiguity around behavioural expectations.

Large consumption places include places that are generally accessible to all members of the community but are monitored and regulated by a place-manager. Accessibility is limited to opening hours and may be subject to conditions (e.g. following certain rules). These include places like shopping centres, malls, and supermarkets. While the primary function of these places is an economic one, because they are a necessity in the daily lives of the majority of individuals in the community, they may also support community sociality. However large consumption places tend to service large catchment areas and cater to a diverse population group. Therefore, a sense of social cohesion and place attachment at large consumption places may be lower and factors such as diffusion of responsibility, audience inhibition and social influence may impede willingness to intervene. Similar to public places we would expect the propensity for guardianship action to be low at large consumption places.

Local consumption places include small businesses where economic transactions may be accompanied by temporary dwelling and potential for the development of familiarity and acquaintanceships with employees and other regular consumers (Piekut & Valentine, Citation2017). These places include local cafes, specialty stores or take-aways, local pubs/bars and restaurants. Socialisation places provide opportunities for voluntary engagement in social ties and tend to be accessed by a smaller, defined group of people who are unified by a shared place identity. These places include gyms and health clubs, community clubs, volunteer associations and places of worship. Local consumption and socialisation places represent Altman’s (Citation1975) second or third territories. These places tend to be privately owned with a manager primarily responsible for their upkeep and protection. These places tend to have clear behavioural expectations and regular visitation is likely to engender feelings of attachment and social connection that may be associated with a higher propensity to enact guardianship.

In this study place type is a categorical variable indicating the type of place, nominated by the participant, that they frequently visit as part of their routine activities (1 = public places; 2 = large consumption places; 3 = local consumption places; 4 = socialisation places). The participants were directed to think about this particular place when answering all questions about perceived crime and disorder and how they responded to crime and disorder (dependent variable). Participants were again directed to think about this place when they answered the questions about place attachment.

Place Attachment. We measure place attachment using items adapted from the abbreviated place attachment scale (Boley et al., Citation2021; Williams & Vaske, Citation2003). The scale comprises nine items that ask respondents to rate their agreement with a series of statements on a scale of one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Respondents are directed to think about ‘the place in their neighbourhood that they frequently go to as part of their routine activities’ when answering these questions (this is the same place referred to throughout the survey questions). This scale has been used in previous studies examining place attachment at activity nodes outside the home including parks, nature reserves (Boley et al., Citation2021) public houses (Sandiford & Divers, Citation2011) and shopping malls (Debenedetti et al., Citation2014). This scale has an alpha reliability score of 0.84.

Social cohesion. Social cohesion is measured as the mean score of four items from the survey. This scale was adapted from the original social disorder scale utilised in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighbourhoods (PHDCN) Community Survey (Sampson & Raudenbush, Citation2004). The four items ask respondents to rate their level of agreement on a scale of one to five (strongly disagree to strongly agree) with four statements: People in this neighbourhood are willing to help their neighbours; This is a close-knit community; People in this neighbourhood generally get along with one another; People in this neighbourhood do not share the same values (reverse coded). The alpha reliability score of this scale 0.73.

Perceived disorder. To control for disorder at the level of the neighbourhood, we include a measure comprised of three items from the survey that asked participants how frequently the following three activities occur in their residential neighbourhood: graffiti and vandalism; drug use; youth getting into trouble with police. Participants were asked to respond on a scale of one (never) to five (daily). The measure used in the analyses is the mean of the three items. The scale has an alpha reliability score of 0.88.

We examine perceptions of place disorder as opposed to more serious crime given the well-established link between perceived disorder, feelings of safety and propensity to visit public and semi-public places (Perkins & Taylor, Citation1996; Wilson & Kelling, Citation1982). Disorder encompasses both illegal behaviours and social norm disturbances that have the potential to occur in many types of public places and that we could expect individuals to respond to using either direct or indirect active guardianship. Serious criminal offences are rare, and it is unusual for them to be visible in public places. While guardianship presence may prevent these types of crime, we would not expect individuals to enact direct guardianship (i.e. personally intervene) in serious criminal behaviour in public places such as shops or transit stations where security, staff or police were present. Therefore, examining disorder allows us to examine the full continuum of potential guardianship behaviours that individuals may choose to engage in.

Demographic characteristics. We control for social-demographic characteristics that are noted in the literature to influence individuals perceptions of crime and attachments to place (Lewicka, Citation2011; Proshansky et al., Citation1983). These include sex at birth (0 = man; 1 = woman), age (1 = 18–34 years; 2 = 35–54 years; 3 = 55–64 years; 4 = 65 years and above years); employment status (1 = work full-time; 2 = work part-time; 3 = retired/pension; 4 = unemployed looking for work; 5 = other duties); home ownership status (0 = own; 1 = rent); years at current address and language spoken at home (0 = English only; 1 = non-English speaking at home).

Analysis

We estimate two multinomial logistic regression models to assess the influence of place type, place attachment and perceived social cohesion on responses to disorder at frequently visited places within individuals’ routine activity spaces. In model 2 we include an interaction term to examine the moderating effect of perceived social cohesion on the association between place attachment and propensity to enact guardianship in response to disorder. We used the response category saw problems took no action as the reference category. We use large consumption places (2) as the reference category for place type. Results are reported as relative risk reduction (RRR) values. RRRs can be interpreted as the percentage decrease in the risk of an outcome associated with the presence or exposure to an independent variable. presents the descriptive statistics for all variables (correlation table in Appendix). Variance inflation scores were all below 2 (average = 1.18) suggesting that multicollinearity was not a problem in the models.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (N = 944).

Results

Most commonly when individuals observed disorder at places in their local neighbourhood, they took no action (n = 369, 39.30%). Almost one-third of individuals directly responded to problems they observed by intervening (n = 267, 28.43%). A small proportion of individuals reported problems to the police or staff (n = 56, 5.96%). 26.30% of the individuals stated they had not seen any disorder problems at the place they frequented (n = 247).

presents the results of multilevel regression model 1. Saw problems took no action is the reference category. In comparison to saw problems took no action, the odds of not observing disorder were higher in public places (RRR = 2.61, p < 0.001), local consumption places (RRR = 1.94, p < 0.05) and socialisation places (RRR = 4.30, p < 0.001), compared to large consumption places. Compared to saw problems took no action the odds of not observing disorder were also higher for older individuals (RRR = 3.51, p < 0.01) and individuals residing in regional areas (RRR = 1.72, p < 0.001) compared to younger people and city dwellers respectively. Alternatively, the odds of not observing disorder were lower among individuals who were undertaking other duties (home duties, carer duties) compared to full-time employed individuals (RRR = 0.46, p < 0.05).

Table 2. Multinomial logistic regression estimating response to disorder (reference category ‘no action’).

Compared to saw problems took no action the odds of directly intervening in disorder problems were higher at socialisation places compared to large consumption places (RRR = 1. 81, p < 0.05). Older individuals were more likely to directly intervene in disorder problems than younger people (RRR = 3.85, p < 0.001) while non-English speakers were less likely to directly intervene in disorder problems compared to English-only speaking residents (RRR = 0.44, p < 0.001).

Compared to saw problems took no action individuals with higher place attachment were more likely to notify staff or police when they observed disorder problems at places (RRR = 2.17, p < 0.05), as were older individuals (RRR = 4.46, p < 0.001) compared to younger people.

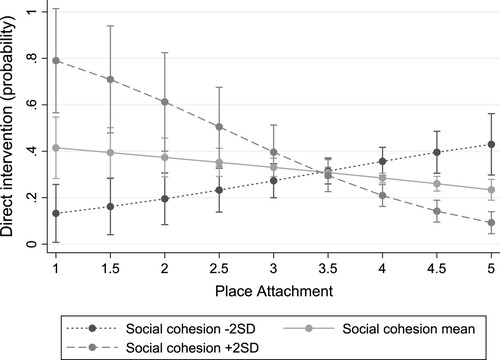

In model 2 we incorporate an interaction term to examine the moderating effect of perceived social cohesion on the relationship between place attachment and guardianship response. The results of model 2 (, ) demonstrate a moderating effect of perceived social cohesion on the association between place attachment and the odds of direct guardianship intervention in problems such that when social cohesion is low higher place attachment increases the odds of direct guardianship intervention, however when social cohesion is high stronger place attachment is associated with lower odds of direct intervention.

Figure 1. Moderating effect of social cohesion on the association between place attachment and active intervention.

Table 3. Model 2 Multinomial logistic regression estimating responses to disorder at places: place attachment ##social cohesion.

Discussion

Public places play an essential role in daily life and are the key to vibrant neighbourhoods. Crime and disorder can deter the use of public places and inhibit opportunities for social interactions and the development of a sense of community (Dines et al., Citation2006; Jaśkiewicz & Wiwatowska, Citation2018). Residents and frequent visitors play an important role in keeping neighbourhood places safe by acting as informal guardians when police and authorities cannot be present. In this study, we examined the influence of place type, place attachment and perceived social cohesion on individuals’ propensity to enact guardianship in response to disorder at highly frequented places within their routine activity spaces. In this discussion, we draw on the concepts of active guardianship, territory, and the bystander effect to interpret the key findings of our study.

First, similar to studies conducted on active guardianship in residential settings we found that active guardianship in public places is associated with place attachment. Specifically, there is a direct relationship between place attachment and notifying police or staff when disorder is observed. Given place attachment describes an affective bond to place that encompasses ‘feelings, thoughts and behaviours that demonstrate commitment’ (Woldoff, Citation2002, p. 87), greater propensity for guardianship reported alongside place attachment may reflect intentions to return to the place in the future and desire to maintain the future safety of the place for the individual’s own benefit (Altman & Low, Citation1992). Individuals with higher place attachment may also have greater familiarity with place-based processes and synergy with the place-based norms leading to greater guardianship capacity (Altman & Low, Citation1992). When individuals have greater confidence in their knowledge of the social norms they may also be less reliant on social influence (Latané & Darley, Citation1970) to inform their responses to place-based disorder.

Research shows that place attachment in the residential neighbourhood coincides with feelings of safety and confidence (Anton & Lawrence, Citation2014; Lewicka, Citation2011; Proshansky et al., Citation1983), sense of social connection (Debenedetti et al., Citation2014; Lewicka, Citation2010, Citation2011; Sandiford & Divers, Citation2019) and sense of ownership (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). These aspects of place attachment have been demonstrated to enhance guardianship in the home and residential territory (Reynald, Citation2011; Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). While previous scholars suggest a significant overlap between place attachment and territorial functioning place attachment differs from territoriality because it is less spatially delimited and is not, by definition, associated with defensive cognitions and behaviours such as guardianship action (Brown & Altman, Citation1981, Citation1983). Here our findings suggest that place attachment is indeed a component of guardianship action perhaps a precursor of guardianship at frequently visited public places but cannot alone account for guardianship action.

Similar findings emerge from studies examining place attachment, psychological sense of ownership and place protective behaviours among frequent park visitors and employees at shops (Potdar et al., Citation2021). Previous research demonstrates that place attachment is highly related to a psychological sense of ownership which in turn increases the propensity for frequent park visitors to engage in environmentally protective behaviours (Kuo et al., Citation2021; Rosenthal & Ho, Citation2020) and the likelihood that shop staff will intervene in customer deviance respectively (Potdar et al., Citation2021; Xiong et al., Citation2019). Thus, our first finding aligns with our hypothesis based on crime pattern theory and active guardianship and with previous scholarship on the relationship between place attachment and guardianship action in residential and public places.

Second, our results suggest that compared to the residential setting, active guardianship in public places may be more dependent on the social, situational context and therefore more temporally dynamic than guardianship behaviour in the home. We found that perceived social cohesion significantly moderated the association between place attachment and active guardianship such that when individuals reported both high place attachment and high social cohesion, they were less likely to personally engage in guardianship action. We offer two potential explanations for this finding. First, in line with the bystander effects literature this result suggests that when individuals identify strongly with place and are more dependent on returning to the place in the future, they may be more vulnerable to social factors such as diffusion of responsibility and social influence. Place attachment is a connection to place that emerges when individuals establish feelings of familiarity and a sense of congruence between self-identity and place characteristics (Lewicka, Citation2011). Social cohesion is associated with trust that others share similar values and will help in an emergency (Sampson & Raudenbush, Citation2004). Drawing on the bystander literature we may assume that under the conditions of both high place attachment and high social cohesion, there is a greater propensity for the diffusion of responsibility given that people are more likely to make assumptions about the behaviour of others, based on their familiarity with the place, and individuals are likely to trust others will do something to respond to problems (Linning & Barnes, Citation2022). Similar, to Linning and Barnes (Citation2022) research, we suggest that our findings may also indicate that high social cohesion and trust at familiar places hinder intervention by making individuals feel that someone else will respond to the problem and they do not have to.

An alternative explanation draws on Taylor’s concept of territorial functioning and suggests that the moderating effect of social cohesion on the link between place attachment and guardianship may be dependent on place types (Taylor et al., Citation1984). While we cannot establish this interpretation empirically from our study results, theoretically we suggest that in addition to place attachment and social cohesion at places, a third variable that must be considered is the social distance between the potential guardian and the transgressor. Taylor suggests that in public places, territories and related cognitions may be temporarily established during visitation (Taylor & Brooks, Citation1980) however defensive territorial behaviour will only emerge in regular use settings under certain conditions. He suggests that several cultural, social and physical elements of frequently visited places can influence territorial behaviour (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). First, defensive behaviours tend to covary with place dependence, that is the perceived desirability of the locale in a persons’ routine activity space (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988, p. 244); second, a sense of social cohesion with the majority group can enhance territorial behaviour. Third, from Taylor’s perspective, social distance between the individual and the transgressor can impede intervention action (Taylor & Covington, Citation1988). Thus at large consumption places, local consumption places and public places that are open to many people from diverse backgrounds and where individuals may encounter socially distant, non-regulars (outgroup) who are completely unfamiliar with place-based social norms, they may be unlikely to intervene even when place attachment and perceived cohesion is high. Alternatively, at socialisation places where others, even transgressors, are likely to be members of a club or collectively identify with a shared interest, place attachment combined with social cohesion may encourage intervention because the transgressor is more likely to be more socially similar and should be familiar with the appropriate place-based social norms. Thus, at places that are outside of the residential setting individuals with a higher sense of social cohesion may be less likely to directly intervene in more public places and when they perceive the transgressor as socially distant, even when place attachment and social cohesion are high.

Overall, our second finding shows support for the bystander effect and highlights how Taylor’s perspective on territorial functioning may help to understand the differences between our findings regarding active guardianship in public places (public territories) and previous research on active guardianship in private and secondaries territories around the residential home. However, more research is needed to investigate the influence of place attachment and social cohesion on guardianship-in-action across different types of places using various transgressor scenarios to empirically examine Taylor’s concept of temporary territories.

Two further findings of our study require noting. First is the influence of place type on guardianship responses. We find that guardianship enacted through both direct intervention or notifying police or staff of crime and disorder problems is most likely to occur at socialisation places. Socialisation places include places such as community clubs, fitness centres and places of worship. The physical and social characteristics of socialisation places reflect those that support behaviours and attitudes that Taylor et al. (Citation1984) suggest strengthening territorial functioning including: (1) definitive physical boundaries, (2) documented behavioural expectations and, (3) hierarchy of power and responsibility. Taylor et al. (Citation1984) purported that these characteristics support defensive guardianship in residential activity spaces when coupled with a strong sense of community. The physical design and social context of socialisation places may support guardianship capacity because when compared to consumption places and public parks, socialisation places tend to have clearer physical boundaries, access is limited to a sub-group of the population and people have defined social roles that structure interactions and regulate behaviours (Proshansky et al., Citation1972; Taylor & Stough, Citation1978).

A second additional point worth noting is that many participants reported they did not see any problems at the public places they frequented and even when they did, they did nothing about them. The bystander literature consistently finds that dangerous emergencies are perceived as a problem more consistently and clearly across the population than non-dangerous problems such as those featured in our survey (Fischer et al., Citation2011). Further, dangerous problems are more likely to motivate intervention (Fischer et al., Citation2011). In our study, the problems we assessed were relatively minor. This may have influenced individuals’ capacity to notice and their propensity to respond to place-based problems that we asked about in the survey. Given many participants frequently visited places that have place managers such as large consumption places, there may have been few problems visually evident. Place managers regulate disorder in real time and limit opportunities for crime and disorder to fester (Douglas & Welsh, Citation2020).

Recent research demonstrates that assessments of situations and willingness to enact guardianship vary across situational contexts. Here we add to this growing literature by assessing factors associated with responses to disorder in public places by applying concepts from routine activity theory, territoriality, and bystander intervention literature. While our findings extend to previous empirical work on guardianship-in-action, we acknowledge a number of limitations. First, due to the confidential nature of the survey, we were unable to control for objective neighbourhood characteristics and features within individuals’ activity spaces. We acknowledge that the socio-demographic backcloth has been shown to influence guardianship behaviours in the residential setting and we aim to incorporate these measures in future data collection. We are also only able to examine individuals’ guardianship behaviours at their most frequently visited public place in their routine activity space. This precludes the capacity to assess variation within individuals, across place types. Finally, due to sample size of only 940 participants, our models demonstrate relatively small (7.34%) (although statistically significant) variation between responses, and we were unable to empirically examine three-way interactions. However, given that this is the first study to empirically assess what individuals have done in response to problems witnessed at frequently visited places in their routine activity space, our findings offer significant insights and suggest further investigation into public place guardianship through experimental research and on a larger scale is warranted. For example, future research could consider conducting experiments with confederates, similar to those conducted in studies of the bystander effect (Critelli & Keith, Citation2003; Latané & Darley, Citation1970), who would be charged with undertaking minor nuisance behaviours such as playing loud music or littering in a range of public places. This would provide opportunities to examine individuals’ responses to low-level disorder in different physical and social settings.

Conclusion

Criminological perspectives of active guardianship founded on routine activities and situated in residential territories can partially explain active guardianship in public places. However, to further our understanding requires that we draw on perspectives beyond active guardianship to consider concepts from the bystander effect literature. The bystander effect may better account for how the social context and presence of other potential guardians impact guardianship-in-action at places outside of the residential setting where social roles are less clear, power hierarchies are flatter and the person responsible for norm enforcement is not immediately evident. For example, our findings suggest that perceived social cohesion in public places may hinder individual guardianship action, but place attachment can facilitate intervention in such situations. Taylor’s conceptualisation of territorial cognition and functioning offers important insights into why some types of public places are more likely to elicit active guardianship than others. Future research is required to follow up Taylor and Brooks (Citation1980) work on temporary territories in public places and to examine guardianship alongside other concepts from environmental criminology including risky facilities and hot spots to consider the extent to which active guardianship may be facilitated in high crime places through social norm interventions and targeted strategies that encourage place attachment through higher place occupancy, such as adopt -a-park. Local business owners and municipal councils can also help to encourage place identity by establishing iconic physical structures and introducing membership or loyalty schemes. These strategies may help to increase the sense of responsibility directly and indirectly through enhanced place attachment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The analytic sample comprises 940 individuals who named a public place they visited most frequently in their neighbourhood. Individuals who named their own residence or a friend’s residence were removed from the analysis. The final analytic sample retains accurate representation of the Australian adult population with the exception of age. In the analytic sample, 15.4% of the participants are aged 18–34 years compared to 20.6% of persons aged 18–34 years in the Australian population at the 2021 census. Sampling across states and territories was conducted relative to the contribution of the state population to the total Australian population to ensure relative weight of state representation. All data and models are available upon request.

2 97.4% (n = 917) of the final analytic sample completed the survey online, only 23 participants (2.4%) were surveyed over the phone.

References

- Ahmed, E. (2008). ‘Stop it, that’s enough’: Bystander intervention and its relationship to school connectedness and shame management. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 3(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450120802002548

- Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior: Privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- Altman, I., & Low, S. (1992). Place attachment. Plenum.

- Anton, C. E., & Lawrence, C. (2014). Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.10.007

- Banyard, V. L. (2008). Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: The case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims, 23(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.83

- Banyard, V. L., Edwards, K., & Rizzo, A. (2019). “What would the neighbors do?” Measuring sexual and domestic violence prevention social norms among youth and adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(8), 1817–1833. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22201

- Bernasco, W., & Block, R. (2011). Robberies in Chicago: A block-level analysis of the influence of crime generators, crime attractors, and offender anchor points. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810384135

- Block, J. P., Scribner, R. A., & DeSalvo, K. B. (2004). Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income - A geographic analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 211–217.

- Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., Yeager, E. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., & Mimbs, B. P. (2021). Measuring place attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, 101577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101577

- Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (1981). Notes on the geometry of crime. In P. J. Brantingham, & P. L. Brantingham (Eds.), Environmental criminology (pp. 27–53). SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

- Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1993a). Environment, routine and situation: Toward a pattern theory of crime. Advances in Criminological Theory, 5(2), 259–294.

- Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1993b). Nodes, paths and edges: Considerations on the complexity of crime and the physical environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80212-9

- Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1995). Criminality of place. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3(3), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02242925

- Brown, B. B., & Altman, I. (1981). Territoriality and residential crime – A conceptual framework. In P. J. Brantingham, & P. Brantingham (Eds.), Environmental criminology (pp. 55–76). Sage Publications.

- Brown, B. B., & Altman, I. (1983). Territoriality, defensible space and residential burglary: An environmental analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80001-2

- Ceccato, V., Falk, Ö., Parsanezhad, P., & Tarandi, V. (2018). Crime in a Scandinavian Shopping Centre. In V. Ceccato, & R. Armitage (Eds.), Retail crime: International evidence and prevention (pp. 179–213). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73065-3_8

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

- Critelli, J. W., & Keith, K. W. (2003). The bystander effect and the passive confederate: On the interaction between theory and method. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 24(3/4), 255–264. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43854004.

- Debenedetti, A., Oppewal, H., & Arsel, Z. (2014). Place attachment in commercial settings: A gift economy perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(5), 904–923. https://doi.org/10.1086/673469

- Dines, N., Cattell, V., Gesler, W. M., & Curtis, S. (2006). Public spaces, social relations and well-being in east London. Policy Press.

- Douglas, S., & Welsh, B. C. (2020). Place managers for crime prevention: The theoretical and empirical status of a neglected situational crime prevention technique. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 22(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-020-00089-4

- Felder, M. (2021). Familiarity as a practical sense of place. Sociological Theory, 39(3), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/07352751211037724

- Felder, M., & Pignolo, L. (2018). Shops as the bricks and mortar of place identity. In L. Ferro, M. Smagacz-Poziemska, M. V. Gómez, S. Kurtenbach, P. Pereira, & J. J. Villalón (Eds.), Moving cities – Contested views on urban life (pp. 97–114). Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18462-9_7

- Felson, M., & Boivin, R. (2015). Daily crime flows within a city. Crime Science, 4(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-015-0039-0

- Fischer, P., Greitemeyer, T., Pollozek, F., & Frey, D. (2006). The unresponsive bystander: Are bystanders more responsive in dangerous emergencies? European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(2), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.297

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023304

- Fledderjohann, J., & Johnson, D. R. (2012). What predicts the actions taken toward observed child neglect? The influence of community context and bystander characteristics. Social Science Quarterly, 93(4), 1030–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00859.x

- Groff, E., & McCord, E. S. (2012). The role of neighborhood parks as crime generators. Security Journal, 25(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2011.1

- Hipp, J. R., Bates, C., Lichman, M., & Smyth, P. (2019). Using social media to measure temporal ambient population: Does it help explain local crime rates? Justice Quarterly, 36(4), 718–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1445276

- Hollis-Peel, M. E., Reynald, D. M., van Bavel, M., Elffers, H., & Welsh, B. C. (2011). Guardianship for crime prevention: A critical review of the literature. Crime, Law and Social Change, 56(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-011-9309-2

- Jaśkiewicz, M., & Wiwatowska, E. (2018). Perceived neighborhood disorder and quality of life: The role of the human-place bond, social interactions, and out-group blaming. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 58, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.07.008

- Kim, Y.-A., & Hipp, J. R. (2022). Small local versus non-local: Examining the relationship between locally owned small businesses and spatial patterns of crime. Justice Quarterly, 39(5), 983–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2021.1879899

- Kumar, J., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Exploring destination psychological ownership among tourists: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 39, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.01.006

- Kuo, H.-M., Su, J.-Y., Wang, C.-H., Kiatsakared, P., & Chen, K.-Y. (2021). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior: The mediating role of destination psychological ownership. Sustainability, 13(12), 6809–6825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126809

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn't he help? Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Leclerc, B., & Reynald, D. (2017). When scripts and guardianship unite: A script model to facilitate intervention of capable guardians in public settings. Security Journal, 30(3), 793–806. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2015.8

- Levine, M., Cassidy, C., Brazier, G., & Reicher, S. (2002). Self-categorization and bystander non-intervention: Two experimental studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(7), 1452–1463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb01446.x

- Levine, M., & Crowther, S. (2008). The responsive bystander: How social group membership and group size can encourage as well as inhibit bystander intervention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1429–1439. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012634

- Levine, M., & Manning, R. (2013). Social identity, group processes, and helping in emergencies. European Review of Social Psychology, 24(1), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2014.892318

- Lewicka, M. (2010). What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.05.004

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Li, S., Wei, M., Qu, H., & Qiu, S. (2020). How does self-image congruity affect tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2156–2174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1800717

- Liebst, L. S., Philpot, R., Bernasco, W., Dausel, K. L., Ejbye-Ernst, P., Nicolaisen, M. H., & Lindegaard, M. R. (2019). Social relations and presence of others predict bystander intervention: Evidence from violent incidents captured on CCTV. Aggressive Behavior, 45(6), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21853

- Linning, S. J., & Barnes, J. C. (2022). Third-party crime reporting: Examining the effects of perceived social cohesion and confidence in police effectiveness. Journal of Crime and Justice, 45(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2020.1856706

- Lockitch, J., Rayment-McHugh, S., & McKillop, N. (2022). Why didn’t they intervene? Examining the role of guardianship in preventing institutional child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 31(6), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2022.2133042

- Marquet, O., Ogletree, S. S., Hipp, J. A., Suau, L. J., Horvath, C. B., Sinykin, A., & Floyd, M. F. (2020). Effects of crime type and location on park use behavior. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17(E73), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.190434

- Menting, B., Lammers, M., Ruiter, S., & Bernasco, W. (2019). The influence of activity space and visiting frequency on crime location choice: Findings from an online self-report survey. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(2), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz044

- Perkins, D. D., & Taylor, R. B. (1996). Ecological assessments of community disorder: Their relationship to fear of crime and theoretical implications. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(1), 63–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511883

- Piekut, A., & Valentine, G. (2017). Spaces of encounter and attitudes towards difference: A comparative study of two European cities. Social Science Research, 62, 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.005

- Potdar, B., Garry, T., Gnoth, J., & Guthrie, J. (2021). An investigation into the antecedents of frontline service employee guardianship behaviours. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31(3), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-06-2020-0124

- Pridemore, W. A., & Grubesic, T. H. (2013). Alcohol outlets and community levels of interpersonal violence: Spatial density, outlet type, and seriousness of assault. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50(1), 132–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810397952

- Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80021-8

- Proshansky, H. M., Ittelson, W. H., & Rivlin, L. G. (1972). Freedom of choice and behavior in a physical setting. [https://doi.org/10.1037/10045-003]. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10045-003

- Reynald, D. M. (2009). Guardianship in action: Developing a new tool for measurement. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2008.19

- Reynald, D. M. (2010). Guardians on guardianship: Factors affecting the willingness to supervise, the ability to detect potential offenders, and the willingness to intervene. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(3), 358–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810365904

- Reynald, D. M. (2011). Factors associated with the guardianship of places: Assessing the relative importance of the spatio-physical and sociodemographic contexts in generating opportunities for capable guardianship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48(1), 110–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810384138

- Reynald, D. M. (2018). Guardianship. In G. Bruinsma, & S. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 716–731). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.21

- Reynald, D. M., & Elffers, H. (2009). The future of Newman’s defensible space theory:Linking defensible space and the routine activities of place. European Journal of Criminology, 6(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370808098103

- Reynald, D. M., & Moir, E. (2019). Who is watching: Exploring individual factors that explain supervision patterns among residential guardians. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 25(4), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-018-9380-7

- Rosenthal, S., & Ho, K. L. (2020). Minding other people’s business: Community attachment and anticipated negative emotion in an extended norm activation model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101439

- Rutkowski, G. K., Gruder, C. L., & Romer, D. (1983). Group cohesiveness, social norms, and bystander intervention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(3), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.3.545

- Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67(4), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250406700401

- Sandiford, P. J., & Divers, P. (2011). The public house and its role in society’s margins. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.12.008

- Sandiford, P. J., & Divers, P. (2019). The pub as a habitual hub: Place attachment and the regular customer. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.005

- Scott, A. (1955). The fishery: The objectives of sole ownership. Journal of Political Economy, 63(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1086/257653

- Solymosi, R. (2019). Exploring spatial patterns of guardianship through civic technology platforms. Criminal Justice Review, 44(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016818813428

- Song, G., Zhang, Y., Bernasco, W., Cai, L., Liu, L., Qin, B., & Chen, P. (2023). Residents, employees and visitors: Effects of three types of ambient population on theft on weekdays and weekends in Beijing, China. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 39(2), 385–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09538-1

- Taylor, R. B., & Brooks, D. K. (1980). Temporary territories?: Responses to intrusions in a public setting. Population and Environment, 3(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01254154

- Taylor, R. B., & Covington, J. (1988). Neighborhood changes in ecology and violence. Criminology; An Interdisciplinary Journal, 26(4), 553–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00855.x

- Taylor, R. B., Gottfredson, S. D., & Brower, S. (1984). Block crime and fear: Defensible space, local social ties, and territorial functioning. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 21(4), 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427884021004003

- Taylor, R. B., Haberman, C. P., & Groff, E. R. (2019). Urban park crime: Neighborhood context and park features. Journal of Criminal Justice, 64, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2019.101622

- Taylor, R. B., & Stough, R. R. (1978). Territorial cognition: Assessing Altman's typology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(4), 418–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.4.418

- Tillyer, M. S., Wilcox, P., & Walter, R. J. (2021). Crime generators in context: Examining ‘place in neighborhood’ propositions. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 37(2), 517–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09446-5

- United Nations. (2018). 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN. United Nations. Retrieved 4 July from https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html.

- Vaske, J. J., & Kobrin, K. C. (2001). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960109598658

- Wickes, R., Zahnow, R., Schaefer, L., & Sparkes-Carroll, M. (2017). Neighborhood guardianship and property crime victimization. Crime & Delinquency, 63(5), 519–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716655817

- Williams, D. R., & Vaske, J. J. (2003). The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. Forest Science, 49(6), 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/49.6.830

- Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic Monthly, 249(3), 29–38.

- Wo, J. C., Rogers, E. M., Berg, M. T., & Koylu, C. (2022). Recreating human mobility patterns through the lens of social media: Using twitter to model the social ecology of crime. Crime & Delinquency, 70(8), 1943–1970. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287221106946

- Woldoff, R. A. (2002). The effects of local stressors on neighborhood attachment. Social Forces, 81(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2002.0065

- Xiong, L., So, K. K. F., Wu, L., & King, C. (2019). Speaking up because it’s my brand: Examining employee brand psychological ownership and voice behavior in hospitality organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.006

- Zahnow, R. (2023). Examining train stations as crime generators and the protective effect of “regular” riders. Crime & Delinquency, 00111287231160737. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287231160737

- Zahnow, R., Corcoran, J., Kimpton, A., & Wickes, R. (2022). Neighbourhood places, collective efficacy and crime: A longitudinal perspective. Urban Studies, 59(4), 789–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211008820