ABSTRACT

Recent critiques of integration and superdiversity scholarship pointed out a need to pay more attention to the positioning of established residents, also referred to as 'the mainstream', and to develop novel understandings of urban residents’ reactions to and contestations of the presence of newcomers. Drawing on ethnographic insights from 2015 in a large German city, this article identifies a spectrum of reactions to the installation of a large reception centre for asylum seekers among residents involved in a neighbourhood renewal programme. It delineates how established residents themselves mobilize an integration discourse, associate newcomers with an economic burden and rely on the state for integrating them. Drawing on the notion of ‘Emplacement’, the article highlights how established residents’ occupation with newcomers' integration can be understood in relation to their activity of carving out their place in contemporary diverse and stratified urban environments.

1 Introduction

When large numbers of asylum seekers arrived and were accommodated in neighbourhoods of large German cities in the summer of 2015, this was accompanied by a dominant political discourse that ‘we can do this’ and a broad societal movement to provide a ‘welcoming culture’ for these refugees. At the same time, the anti-immigrant Pegida movement emerged and the anti-immigrant political party ‘Alternative für Deutschland’ (AfD) consolidated itself. While these political mobilisations have received much attention both in public debate and in scholarship, there is less research on how established residents negotiated the accommodation of asylum seekers in urban neighbourhoods. However, these ‘arrival areas’ (Hanhörster and Wessendorf Citation2020) provide an important sphere where perspectives on newcomers and scenarios for integration are exchanged. This is relevant to migration scholarship, as we do not fully understand when diversity results in a peaceful co-existence or in conflict (Foner, Duyvendak, and Kasinitz Citation2017). Scholarship on diversity has observed how living together in difference can become normal and banal (Wessendorf Citation2013), but also captured how members of the ‘mainstream’ draw bright boundaries and contest migration and diversity. Hence, the negotiation of migration-related diversity in urban contexts challenges scholarship to provide the analytical concepts for capturing and explaining nonlinear processes and uneven dynamics. Integration and super-diversity have been prominent terms in these debates and they have been criticised for failing to capture the complete picture (Alba and Duyvendak Citation2017; Schinkel Citation2018). Suggesting an alternative approach, this article will bring into view the emic use of integration as a category of practice (Brubaker Citation2013) by established residents in situations where (super-) diversity is antagonised and contested.

Examining a situation where residents involved in urban renewal challenged the installation of a reception centre for asylum seekers in 2015, the article will ask the question: How did these residents receive and negotiate the accommodation of asylum seekers? To answer this question, the article addresses the following sub questions: Did they accept or reject the accommodation? Which role did they assign to themselves and to the state in negotiating the presence of the asylum seekers? How did established residents’ experiences with migration-related diversity in the neighbourhood inform their response to the asylum seeker reception centre?

Counter to the common assumption in the literature that migration-related diversity is either normalised or antagonised (Foner, Duyvendak, and Kasinitz Citation2017), my expectation is that there is variation in the resident’s responses. Furthermore, I expect that residents assign the responsibility for integration to asylum seekers based on a conception of integration as a one-way adaptation or assimilation of immigrants (Schinkel Citation2018), especially among people with anti-immigrant tendencies. Lastly, I expect that negative discourses about previous guest workers inform the contestation of the asylum seeker reception centre. This is in line with recent findings on the volatility of categorisations, as categorical distinctions of asylum seekers and other types of migrants are collapsed in some cases, whereas categories are fetishised in others (Vollmer and Karakayali Citation2018; Crawley and Skleparis Citation2018).

In the following, I first discuss existing conceptions of integration and superdiversity and their critiques (Section 2). The article then proceeds by delineating the context of the research: an urban renewal programme in a diverse neighbourhood on the periphery of a large German city (Section 3). After delineating the methods of the study (Section 4), the article proceeds to the analysis of established residents’ responses to the accommodation of asylum seekers (Section 5) and discusses the findings (Section 6). The article concludes by summarising the main argument and contribution to the existing debate on integration and superdiversity (Section 7).

2 Theoretical approaches

Drawing on concepts of integration or (super)diversity, existing migration scholarship seeks to capture societal processes in urban contexts informed by migration. Integration has been defined as ‘the process of becoming an accepted part of society’ (Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2016, 14), and scholars have often drawn on the metaphor of the two-way street to capture mutual accommodation of host and immigrant groups (Alexander Citation2003). The concept leaves much scope for questions about the who, how and what of integration and about its normative assumptions relating to the naturalisation of the nation state and a rigid understanding of ethnic groups (Favell Citation2001). Superdiversity in some ways can be considered as a critique of the assumption of a homogeneous native majority to which an immigrant minority is added, but highlights the complex composition of contemporary societies due to migration. Such complexity cannot be reduced to ethnic difference but requires considering various categories of difference and their interplay (Vertovec Citation2007). Existing scholarship using the concepts of integration and superdiversity often investigates the ways in which difference is negotiated in everyday life (Wessendorf Citation2013) or in public institutions (Schiller Citation2016). An ongoing critique of scholarship on integration is that the emphasis has been on the performance of immigrants themselves and that research insufficiently captures the ways how established residents are taking part in integration processes. In a recent commentary, Willem Schinkel (Citation2018) argued that we should once and for all dispose of the concept of integration because it ‘dispenses’ the established residents from integration. Furthermore, integration would transport an implicit norm that integration into ‘society’ should be achieved, thereby defining society as spaces that belong to the established residents. The reiteration of integration then becomes a means of boundary-drawing vis-à-vis the outsiders, that is, immigrants (Schinkel Citation2018).

The concept of superdiversity has been criticised as well. Alba and Duyvendak (Citation2017) raised the question ‘And what about the mainstream?’ in the context of super-diversity. They argue that an emphasis on the normalcy of super-diversity often prevents research to engage with the re-emergence of the politicisation and culturalization of difference by natives and a decreasing space for diversity (Alba and Duyvendak Citation2017, 5). In their view, we should engage more with the native working class because this is where integration often begins (Alba and Duyvendak Citation2017, 7). As Mepschen (Citation2019) argues, natives often perceive a loss of being at home and in control when immigrants settle, which goes hand in hand with a feeling of temporal and spatial displacement. This motivates the natives to draw bright boundaries vis-à-vis the ‘diverse other’ in public discourses (Mepschen Citation2019). Wekker (Citation2019) examined resistance of native residents when social workers in the local neighbourhood centre promoted a discourse of diversity as a normalcy (Wekker Citation2019). Two main reasons stick out in these critiques of concepts of integration and super-diversity: a) the silence on the role of established residents in integration processes and b) the lack of attention for instances where difference is resisted or challenged instead of being perceived as normal and banal.

While these critiques are important, others argue that doing away with the integration concept means throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Instead, the failures of the concept of integration could be corrected by bringing in established residents as agents who also integrate themselves and to conceive of integration as a relational process of different (categories of) people dealing with differences in a post-immigration societal context (Klarenbeek Citation2018). As Caglar (Citation2016) argued, we need to situate all residents (‘migrant’ and ‘non-migrant’) within a common analytical framework. They share experiences of dispossession and together build aspects of social belonging to the city (‘emplacement’) in light of uneven global power relations and processes of urban restructuring. Exchanging the focus on super-diversity with a focus on ‘the mainstream’ could be problematic, too. First of all, existing conceptions of superdiversity acknowledged the role of power and inequalities in superdiverse contexts (Vertovec Citation2015) and we know that everyday multiculturalism and everyday racism can go hand in hand (Wise Citation2005). The definition of the ‘mainstream’ is blurry and risks homogenising a large variety of people who somehow qualify as white, middle- or working-class. When focusing on the mainstream, whom are we focusing on? While it is important to analyse contestations of diversity, exchanging a focus on super-diversity with a focus on the angry white working-class implies taking only a small subgroup of established residents into consideration and assuming that they are struggling with diversity. While it is important to study instances and cases where diversity is resisted, we need to steer away from essentializing the ‘working class’ and from equating a purportedly homogeneous working class with ‘the mainstream’.

Putting recent critiques of integration and superdiversity research to the test, this article analyses the responses of residents, who were involved in the regeneration of their neighbourhood, to the accommodation of asylum seekers in the wake of the long summer of migration in 2015. It diverges from previous critiques of integration and super-diversity by paying attention to variation within responses of established residents and to their emic conceptions of integration in discourses of past and present newcomers.

3 The context

3.1. The urban renewal

The study focuses on the installation of a large asylum seeker reception centre in a neighbourhood on the outskirts of a large German city (>500.000 inhabitants) and the reactions by residents involved in the neighbourhood’s regeneration. Over the past decades, the neighbourhood has experienced de-industrialisation and social decline, motivating the urban planning department in 2008 to choose this neighbourhood for an urban regeneration programme, which is co-funded by the municipality and the regional state and envisaged to run for 8–10 years. It aims to revitalise the physical infrastructure and contribute to the revaluation of the neighbourhood.

A key element of the programme was the so-called ‘local partnership’ of local residents and urban planners, which was founded in 2009 in order ‘to ensure the sustainability of the programme’ (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008). The closed group of ‘local partners’ included selected residents, the urban planners and the staff of the neighbourhood office and they together discussed and decided on all the measures taken. The 10–15 members (there was some fluctuation over the years) met approximately every 6 weeks and in 2015 celebrated their 50th meeting.

Their meetings usually focused on the design and implementation of measures, such as the re-design of a square or of a building compound for joint building ventures, the creation of a website on the neighbourhood, or the optical improvement of the entrance areas. But in December 2015 involved residents used the meeting to contest the installation of a large asylum seeker accommodation centre in the neighbourhood – discussing it as a question of integration and taking a variety of positions.

3.2. The neighbourhood

The neighbourhood today counts approximately 18.000 inhabitants and due to its industrial past, is characterised by an amalgamation of (former) factories and industrial plants, workers’ homes and social housing complexes, as well as single-family houses. The neighbourhood has the highest share of foreigners compared to other neighbourhoods in the city (Municipality name anonymized Citation2015),Footnote1 including former guestworkers, members of traveller communities, as well as more recently arrived asylum seekers. This makes it an interesting place to study negotiations of (super-)diversity. Many residents referred to its high street, church and old town hall as important landmarks that give the neighbourhood a distinct village atmosphere.

In the same breath, residents often referred to the downturn in the neighbourhood over the past decades, both in physical and social terms. In the neighbourhood’s ‘high street’ most of the supermarkets as well as traditional speciality shops had closed down, losing the competition with large shopping malls and chain stores in the neighbourhood’s vicinity. Ethnic businesses, kebab and pizza joints, and amusement halls opened in their place. Especially some of the more long-standing inhabitants problematised this development, as they missed their old quality shoe shop, for example, and interpreted the opening of cheap(er) ethnic shops as a symptom of the decline of the neighbourhood.

Residents also pointed out that private real estate corporations had bought up most of the worker’s homes previously owned by the industries and the national mail company. They let the apartments for a small price, attracting new inhabitants with very little socio-economic capital. Guestworkers and natives living in the neighbourhood had lost their jobs and ended up living on social benefits when some of the large industries had closed their doors. Up until today, these developments have left their imprint on the neighbourhood, which has a high share of unemployed (12.9%)Footnote2 and an estimated 60% of its population relying on welfare support (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008, 66). Young people and especially those of migrant origin are prone to unemployment in the neighbourhood (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008, 66).

3.3. The installation of the asylum seeker reception centre and reactions by local residents

In 2015, the regional state (in charge of initial accommodation for asylum seekers in Germany) in consultation with the local authorities (in charge of providing accommodation after the initial accommodation phase) installed a large asylum seekers reception centre in the neighbourhood. They selected one of the closed down industrial buildings in the neighbourhood as location, with a capacity of housing up to 2000 asylum seekers. The first 1,000 asylum seekers were accommodated there in the middle of December 2015, four weeks after announcing the installation. At the first meeting of the local partnership in January 2016, one of the political representatives raised the recent decision to open a large regional reception centre for asylum seekers and said that he expected a negative effect on the neighbourhood regeneration. Other members immediately joined the problematisation of the reception centre. They complained about the responses of politicians and administrators during a public information meeting, which had been organised a few weeks earlier at a local school with the social affairs alderwoman of the municipality and the asylum coordinator of the regional state. Some of them participated in a tour of the reception centre on 29 December, but this had not changed their minds. The neighbourhood council opposed the plans for locating the reception centre in the neighbourhood, as they considered it as already particularly burdened. They landed an article in the local newspaper to argue that the reception centre would put its regeneration at risk (Local newspaper name anonymised, 24 November Citation2015).

4 Methodology

The ensuing analysis draws on data collected during ethnographic fieldwork in the neighbourhood. From autumn 2015 until summer 2016, the researcher participated in the citizen involvement process of the urban renewal programme and interviewed local partners and some other key local actors, which allowed gaining in-depth insights into the discussions during the meetings and engaging with individual views. The data I collected include field notes, reflections on the monthly meetings, interview recordings, and notes from formal and informal interviews. Twelve recorded interviews were conducted with participants in the local partnership (), with other residents, with the urban and social planners involved in the neighbourhood renewal and with the neighbourhood office personnel. The fieldwork did not contain interviews with asylum seekers themselves, as the focus of the research was to bring into view the negotiation of migration-related diversity by established residents.

Table 1. Overview of interviewees.

I spent an extensive amount of time in the neighbourhood during the fieldwork. In the days of citizen involvement events, I usually spent the day before and after and stayed overnight in the neighbourhood, renting a small room via Airbnb from a young middle-income family that had moved into one of the few new housing development projects. Next to spending time at the neighbourhood office, I became a frequent customer at a café, a bakery, and the ice cream parlour, where most of the interviews took place. I frequented two different kebab eateries and was hanging out on the main square, on the promenade along the river and on the courtyard of the primary school. Informal conversations and observations at these places allowed me to get a better sense about discourses in the neighbourhood and provided me with a relevant background of what was being discussed in everyday contexts of encounter. The following analysis delineates some of the findings from the empirical data.

5 Analysis

5.1. ‘The mainstream’ as a heterogeneous group with diverging responses to newcomers

When I started engaging with the local partnership, my first impression was that of a rather homogeneous group of middle-aged and older people of middle-class background. And when the accommodation of asylum seekers was discussed, my preliminary impression and interpretation was that I was seeing a typical display of residents being afraid of economic decline and blaming immigrants for it. Researching these individuals’ profiles and activities and reflecting on the different statements that were being made (which I had meticulously noted down during the meeting) some more nuance and ambivalences in these residents’ positionings vis-à-vis the accommodation of asylum seekers came to the fore. I identified three subgroups in the local partnership with different perspectives on and claims about the accommodation of asylum seekers in the neighbourhood: the ones describing themselves as overcharged and asking for compensation, the ones asking for social measures to prevent overburdening and to support integration, and the ones that relativise that there was an issue and providing social support themselves.

The first group claimed to have already been overcharged and in need of compensation. One of these local partnership members, Herr Fürther, argued that the share of migrants was already too high in the neighbourhood – and thus would be exceeded by the accommodation of asylum seekers. He said that there were many unemployed people, single moms and socially deprived people living in and moving to the neighbourhood. Mentioning these categories in one breath implied that these groups have something in common, namely that all of them are to be considered problematic. He also pointed out the recent increase in traveller communities, which he problematised as well. Based on these observations, he questioned the capacity of the neighbourhood to integrate the asylum seekers. In his case, he had not only a private but a professional vested interest in the area’s economic development because his business would profit from gentrification. Another member of the local partnership, Herr Gündüz, shared the perception of the neighbourhood as being overcharged by the existing share of immigrants. He had grown up as a child of Turkish guest workers in the neighbourhood and told me about his fond memories about the ways in which native Germans and Turkish immigrants had interacted on an everyday basis in the neighbourhood when he was a child. After attending primary and secondary schools in the neighbourhood, he went to a gymnasium elsewhere, then continued his studies at university and landed a good job in an international company. At the same time, he kept strong ties with the neighbourhood and was engaged in the local Turkish mosque association, drawing on his higher education and capacity to represent their claims. He problematised what he perceived as an increasing presence of immigrants in the neighbourhood over the past years. In his words:

As a Turk I wonder why are so many Turks here now, and many people wonder, where should this be leading to, when everything here is full with migrants. Back when I grew up, 6 out of 10 families in an apartment building were Germans, but they have progressively moved out. Even my mother has the feeling that there are less and less Germans and more and more immigrants. (Herr Gündüz, Line 42)

Herr Fürther and Herr Gündüz considered a high share of immigrants as a problem and hence they positioned themselves against the accommodation of asylum seekers in the area. During the meeting, they requested the city to compensate them for accommodating asylum seekers. They said that the integration courses for the asylum seekers were not enough and that ‘they’, meaning the established residents, should also get something.

The second subgroup of residents involved in the urban renewal programme asked for social support measures to prevent overcharging. They were concerned about the social implications that the large numbers of asylum seekers accommodated might have on the neighbourhood. The resident who brought up the accommodation of asylum seekers in the meeting, let us call him Herrn Schnitzler, can be considered as leader of this group. He was the elected representative of the neighbourhood and member of the Social Democratic Party, a party that is not known for promoting anti-immigrant politics. He was a soft-spoken man approaching pensioner age, identifying as protestant with two children, a person who did not search for the spotlight (I repeatedly urged him to do an interview with me but in vain). When looking closely at his speech during the meeting, his claim was that the accommodation of asylum seekers needs to be accompanied by proactive and solid supporting measures for integration, flagging different national and regional programmes that existed and that one could draw on (he mentioned the national programme ‘Soziale Stadt’ and a regional programme for community work). Such a claim – accepting the accommodation as such but requesting support measures for integration– was also made by other people in the neighbourhood. One interviewee, active in many social and cultural initiatives in the area, flagged that it creates insecurities among the local population when 2000 people are brought to the neighbourhood without any knowledge of German, and that these insecurities needed to be addressed (Frau Schuster,Footnote3 Line 20). As some other residents she highlighted the role of the state in providing measures to foster the integration of the asylum seekers, instead of assuming that residents would figure it out for themselves how to deal with this new situation.

Contrasting with the previous two groups, there were also residents who questioned the perceived negative impact on the neighbourhood and/or who themselves became active in helping asylum seekers as volunteers. I will refer to this group in the following as the ‘keep calm and do it yourself’ integrationists. When the asylum seekers arrived, a local sports association set up an initiative in the neighbourhood to provide help to the asylum seekers, in which some member of the local partnership also volunteered. This included one member of Turkish migrant background, Frau Kaya, who did a lot of volunteering work ‘out of solidarity’ for other immigrant families and children (Frau Kaya, Line 49). Some interviewees presented this helpful attitude and willingness of bottom-up initiatives as a characteristic and strength of the neighbourhood:

I think only a small share of the residents is really rejecting them. But there are questions that arise. These people are here and they should also be supported, and there is a small group that has formed with many volunteers to support the asylum seekers. And that is typical for the neighbourhood. When people feel there needs something to be done, they do something and suddenly different people start moving. It is possible to get to know many people here and one will hardly find closed doors. (Frau Schuster Line 12)

Herr Bors, a family father with a job outside of the neighbourhood, tried to put things into perspective during the meeting. He challenged the other residents to make explicit whether their fears about the impact on asylum seekers were based on concrete observations or incidents. He raised the question of whether the reception centre did put any additional strain on the neighbourhood and whether anyone had yet seen one of the newly accommodated asylum seekers. In their answers, some of the other members acknowledged that the presence of the asylum seekers had so far had very limited impact on the neighbourhood. The presence of the newcomers was only tangible in the larger supermarkets on the outskirts of the neighbourhood but hardly in the centre of the neighbourhood. Other participants, pertaining to the previous two groups, countered that there might not be a problem now, but there would be effects after some time, and they would multiply once the regional state used the maximum capacities of the reception centre.

Some statements and positionalities were more difficult to categorise and interpret and did not fall neatly into one of the three groups. This was, for instance, the case with one of the older members of the local partnership, Frau Wilkens. On the one hand, her narrative entailed a strong problematisation of the ‘Muslim community’. She was lamenting the degree to which local kindergartens and schools were overcharged by ‘Muslim children’ in the area and that the Muslim community did not participate enough in the yearly neighbourhood events or local associational life. On the other hand, she acknowledged that local residents have in the past often failed to attend social activities in the Mosque, although the Turkish Cultural Association was explicitly inviting all neighborhood residents to some of their activities (Frau Wilkens Line 47). Her narrative implied a conception of integration as something that requires the initiative and movement in both directions, and she was critical of shortcomings on both ends. One of the more anti-immigrant members of the local partnership, Herr Fürther, at some point in the discussion acknowledged a modest impact of the new asylum accommodation on his business so far and the possible fleeting negative impact on the neighbourhood image. In a similar vein, another resident said in an interview:

Of course, the asylum seekers need to be accommodated somewhere and of course no one wants them on their corner, but that is always an interplay: we need to help them on the one hand, but we also need to make sure that it does not become too concentrated in one area. And I am not happy that we have this accommodation centre in the neighbourhood, but since it was installed we have not sensed any negative influence. (Herr Mölzer, Line 24)

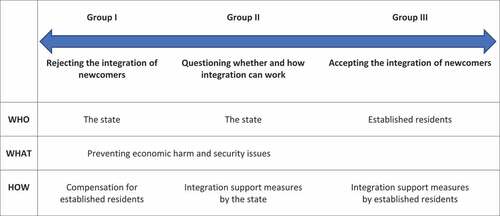

Overall, there is a clear heterogeneity in the reactions of residents, which challenges the assumption of an overall anti-immigrant positioning. What is more, the groups I identified promote different conceptions of who is responsible for integration. The first group emphasised the role of the state, thereby neglecting their own role to allow for integration, but at the same time acknowledged that integration was a possibility. The second group did not see much scope for integration, but rather wanted the state to remove the newcomers again or to be compensated for what they conceived as a burden. The third group requested the least intervention by state actors but emphasised how they themselves could play a role by volunteering and supporting the asylum seekers. Overall, there was little emphasis on integration as something that only migrants have to perform, which is often stipulated in the literature, but there was either an emphasis on the role of the state or on the inhabitants themselves.

These groups of established residents had some conceptions of what integration entails and how it could be achieved. Economic concerns figured high in the discussions, hinting at the prevalence of concerns around dispossession and emplacement among established residents. Security concerns were also referenced to, but to a lesser extent. To summarise, integration in residents’ conception was not so much about the successful integration of newcomers or the role of newcomers in the integration process. It was more about preventing an economic impact of integrating newcomers on established residents and ‘their’ neighbourhood.

5.2. Discursively associating immigrants with economic decline and security threats

The economic concerns were based on a mobilisation of experiences and established discourses on migration. An established discourse associated the economic decline and weak physical structure of the neighbourhood with the presence of large numbers of immigrants in the past. My interviewees emphasised that the closing down of the factories in the neighbourhood had left many of their guest worker employees without a job and dependent on social benefits.

The last thing that happened was that the company [name removed for anonymization] went bankrupt, leaving behind 800 unemployed. Another company [name removed for anonymization] has laid off further employees. Hence, unemployment in the neighbourhood is very high and there are many who have worked in the industries, especially unskilled workers, often immigrants, who have ended up being without a job. (Frau Schuster Line 12)

Although it was not only immigrants who lived on social benefits and ethnic shops provided crucial goods that otherwise would no longer be available in the neighbourhood (as Frau Kaya opined), immigrants were often made responsible for social problems and ethnic shops were seen as symptoms for the decline of spending power in the neighbourhood.

Based on the link between the settlement of immigrants and economic decline, the presence of asylum seekers was constructed as potential obstacle for the economic regeneration of the neighbourhood. The urban renewal programme promised a reversal of the economic downturn, giving the residents new hope and a perspective. Residents had hoped to see the neighbourhoods’ image improve and the installation of the asylum seeker reception centre in the neighbourhood in some residents’ eyes was contradicting all the efforts they had put into the neighbourhood regeneration over the past couple of years. In an interview, one resident said:

What about the neighbourhood, the people here? We fight since 2009, when it was really very bad, for creating a different image of our neighbourhood, we fight for strengthening the neighbourhood and to bring people here who are interested in the neighbourhood, more people who say this is a nice neighbourhood, perhaps I could move there (Frau Schuster Line69)

In residents’ view, the high rate of single parents, socially deprived people, and immigrants already put a burden on local institutions, such as the local schools and kindergartens. They estimated that the municipality will accommodate asylum seekers in municipal housing after the initial reception phase and were concerned about a further strain on services if the asylum seekers stayed in the long run.

Perhaps now one does not feel yet the repercussions, but at some point, these people need to be provided with more permanent accommodation and that is what many people are worried about. It is already the case that German is being spoken not very well here and now another throng comes on top of it, which will again pull us under (Herr Gündüz 54)

One resident associated the accommodation of asylum seekers with the incidents at New Years’ Eve 2015 in Cologne,Footnote4 and raised fears of what the security implications are for the neighbourhood.

Because the fear is there, since what happened in Cologne, there is even more fear. And not only among women, but also among young men. I believe one needs to communicate very clearly to the asylum seekers their rights and duties and integrate them in one way or the other. (Frau Schuster Line 70)

To sum up, negative past discourses about immigrants, associating them with economic decline, were projected onto the present accommodation of asylum seekers, and criminal behaviour of immigrants elsewhere was projected on the security situation in the neighbourhood. At the same time, a few residents in my interviews relativised past problems in the neighbourhood, arguing that things had gotten better over time. As one interviewee noted, the neighbourhood had been a meeting point for skinheads, who had threatened immigrant children in the past (Yilmaz Line 22). This was no longer the case.

6 Discussion

The article examined the responses to the accommodation of asylum seekers in an urban renewal programme in a diverse neighbourhood. It sought to find out how residents negotiated the presence of the asylum seekers and perceived of their own role in accommodating them.

My analysis showed some variation in responses and I identified three main groups of residents: Those who rejected the accommodation of the asylum seekers and requested compensation by the state (Group I), those who were worried about the impact of the accommodation and who requested social support measures by the state (Group II), and the ‘do it yourselves’ integrationists, who relativised the impact of the accommodation of asylum seekers and provided support to asylum seekers themselves (Group III).

While anti-immigrant and pro-immigrant responses have been extensively documented and analysed, my study shows that there is a space in between the extremes. Instead of a binary portrayal of openness and closure as the only alternatives in a context of (super)diversity, these findings attest that we need to acknowledge the existence of a spectrum of positions (), including everyday racism and everyday multiculturalism, but also residents who are neither rejecting nor welcoming the accommodation of asylum seekers.

The groups positioned on this spectrum conceived integration in different ways. Two (I,II) of the three groups assigned the responsibility for integration largely to the state, deferring from the role of established residents in the integration process (Schinkel Citation2018). An emphasis on the role of the state is surprising, as it does not corroborate an often-described political alienation and lack of trust in the government. The more accommodating residents (III) put a stronger emphasis on their own role in contributing to asylum seekers’ integration. In their case little reference was made to an intervention by the state. It shows that reliance on the state and active citizenship in integration is a common conceptualisation among residents.

Another main finding of the article is that residents associated integration of newcomers with an economic burden, supporting literature that conceives of emplacement as a struggle in which not only newly arrived immigrants but also established residents are involved. Established discourses about diversity in the neighbourhood, which associated guest workers with post-industrial decline were crucial for crafting this perspective on integration as countering potential economic damage through the accommodation newcomers. Further empirical research in other neighbourhoods is needed to assess whether similar perspectives can be found in other places and whether these findings can be reproduced.

As these findings also show, other types and categories of immigrants (guest workers, travellers) were used to evaluate the evaluation of asylum seekers’ presence. This confirms my expectation that residents often make no difference between types and layers of immigrants and that negative perceptions of immigrants stick across time. Whether it is asylum seeker or other types of immigrants, residents may collapse into such categories when it fits the purpose of evaluating newcomers’ integration potential.

Drawing on the example of Herr Gündüz, I could show how children of immigrants are not immune to anti-immigrant sentiments, perceiving their socio-economic position and environment as challenged by the presence of newcomers. This is a dynamic that has been described in the US-American literature on segmented assimilation, which posits an economic competition between different segments of society, in which immigrants also participate in. This literature challenges assumptions of an undifferentiated monolithic American mainstream (Portes and Zhou Citation1993). More research is needed to capture the layeredness of diversity and dynamics between past immigrants, their children and newcomers in the European context, especially given the recent arrival of large numbers of asylum seekers.

These findings contribute to the literature as that they allow us sketching a more nuanced picture of integration and (super-) diversity. They show variation in the positionings within the mainstream and concerns about dispossession and emplacement among established residents. While the small scale of the fieldwork hardly allows generalisation, the study provides an in-depth glimpse into the spectrum of reactions by residents, a spectrum that might be found in other neighbourhoods and cities as well. The research counters assumptions that residents are increasingly politically alienated and distrust the effectiveness of state policies (Mudde Citation2013). Instead, we find a strong belief in state-led integration (Scholten Citation2019), albeit there were different conceptions of what that implies: some requested outright compensation, others asked for integration support measures.

7 Conclusion

Recent critiques of concepts of integration have pointed out that research too often has focused on the responsibility of newcomers to integrate and that it has left established residents out of the picture. Critiques of superdiversity have argued that we need research that engages with the conflicts that erupt in the context of diversity. These critiques have brought forward important empirical studies and insights. Yet, we need to avoid the clichés of a homogeneous white, working-class mainstream with anti-immigrant views and a binary of normalisation and contestation in interpreting reactions to the presence of new immigrants.

This article focused on a single case study of reactions to the accommodation of asylum seekers in a large German city, but its findings are significant more broadly. Building on and expanding conceptual and empirical studies on integration and superdiversity (Schinkel Citation2018; Alba and Duyvendak Citation2017; Mepschen Citation2019; Wekker 2018), this article demonstrated that integration is mobilised by residents themselves to make sense of the presence of asylum seekers. Hence, integration remains an important emic discourse to discuss the implications of immigration. It exposed a spectrum of responses by residents, from rejecting the accommodation of asylum seekers to helping asylum seekers. The diversity of positionings of residents puts into question depictions of an overtly anti-immigrant reaction to newcomers. Akin to recent attempts at differentiating nativism (Kešić and Duyvendak Citation2019), we need to problematise assumptions of a uniform host population and differentiate the concept of the ‘mainstream’ further. Otherwise, we risk employing a ‘methodological nationalism’ and homogenising and essentializing established residents (Glick-Schiller and Caglar Citation2009). Instead, more emphasis must be put on examining how residents mobilise and contest anti-immigrant sentiments and (re-)produce an anti-immigrant narrative, as well as how they take ambiguous and undecided positions. In doing so, assumptions about integration, its economic repercussions and the state’s responsibility in compensating established residents for the accommodation of newcomers become visible and discussable.

To acknowledge the role of economic considerations in integration and to employ a common analytical lens for newcomers and established residents, a notion of ‘emplacement’ can be useful. Initially introduced to capture the efforts of immigrants of building relationships and connections within the framework of constraints and opportunities of a specific locality (Glick Schiller and Caglar Citation2016), emplacement allows also capturing such efforts by established residents alongside immigrants. For future research, emplacement implies examining how newcomers and established residents are trying to carve out a place in a shared space and how this process may entail competition and anxiety about economic marginalisation. However, as this study has shown, emplacement can also entail activities out of solidarity and a belief in reciprocity and togetherness in a neighbourhood shaped by global interconnections and interdependencies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In 2015, 39% of all residents in the neighbourhood were foreigners and 63% were people of immigrant background. Over time, there was a constant increase in the share of foreigners of the total population of the neighbourhood: from 26,3% in 1990 to 34,5% in 2007 (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008, 63) to 39% in 2015. Turks represent the largest groups among foreigners, followed by Italians and different nationalities from former Yugoslavia (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008, 63).

2. The percentage of unemployed for the overall city in 2015 was 6,4% (Municipality name anonymized Citation2008, 23).

3. All names are pseudonymized in order to ensure anonymisation.

4. On New Year’s Eve 2015, assaults (including theft, sexual attacks and violence) on women have been reported in the inner-city area of Cologne, committed predominantly by men of North African and Arabic background. These events had gained large public media attention in Germany and beyond, often highlighting the failure of the police during that night.

References

- Alba, R., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2017. “What about the Mainstream? Assimilation in Super-diverse Times.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 105–124. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406127.

- Alexander, M. 2003. “Local Policies toward Migrants as an Expression of Host-stranger Relations. A Proposed Typology.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29 (3): 411–433. doi:10.1080/13691830305610.

- Brubaker, R. 2013. “Categories of Analysis and Categories of Practice: A Note on the Study of Muslims in European Countries of Immigration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.729674.

- Caglar, A. 2016. “Still ‘Migrants’ after All Those Years: Foundational Mobilities, Temporal Frames and Emplacement of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (6): 952–969. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126085.

- Crawley, H., and D. Skleparis. 2018. “Refugees, Migrants, Neither, Both: Categorical Fetishism and the Politics of Bounding in Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224.

- Favell, A. 2001. “Integration Policy and Integration Research in Europe: A Review and Critique.” In Citizenship Today: Global Perspectives and Practices, edited by A. Aleinikoff and D. Klusmeyer, pp.349–399. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute/Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Foner, N., J. W. Duyvendak, and P. Kasinitz. 2017. “Introduction: Super-diversity in Everyday Life.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406969.

- Glick-Schiller, N., and A. Caglar. 2009. “Toward a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 177–202. doi:10.1080/13691830802586179.

- Glick-Schiller, N., and A. Caglar. 2016. “Displacement, Emplacement and Migrant Newcomers: Rethinking Urban Sociabilities within Multiscalar Power.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 23 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2015.1016520.

- Hanhörster, H., and S. Wessendorf. 2020. “The Role of Arrival Areas for Migrant Integration and Resource Access.” Urban Planning 5 (3): 1–10. doi:10.17645/up.v5i3.2891.

- Kešić, J., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2019. “The Nation under Threat: Secularist, Racial and Populist Nativism in the Netherlands.” Patterns of Prejudice 53 (5): 441–463. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2019.1656886.

- Klarenbeek, L. M. 2018. “Relational Integration: A Response to Willem Schinkel.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (20): 1–8.

- Local newspaper name anonymized. 2015. “Article from 24 November.”

- Mepschen, P. 2019. “A Discourse of Displacement: Super-diversity, Urban Citizenship, and the Politics of Autochthony in Amsterdam.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406967.

- Mudde, C. 2013. “Three Decades of Populist Radical Right Parties in Western Europe: So What?”.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x.

- Municipality name anonymized 2008. “[Title Omitted for Reasons of Anonymization].”

- Municipality name anonymized. 2015. Statistical Yearbook.

- Penninx, R., and B. Garcés-Mascareñas, Eds. 2016. Integration Processes and Policies in Europe: Contexts, Levels and Actors. Cham:Springer Open

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96.

- Schiller, M. 2016. European Cities, Municipal Organizations and Diversity: The New Politics of Difference. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schinkel, W. 2018. “Against ‘Immigrant Integration’: For an End to Neo-colonial Knowledge Production.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (31): 1–17.

- Scholten, P. 2019.“Mainstreaming versus Alienation: Conceptualizing the Role of Complexity in Migration and Diversity Policymaking.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 46:1, 108-126.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Vertovec, S. 2015. “Introduction: Formulating Diversity Studies.” In Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies, edited by S. Vertovec, pp. 1-20. Routledge: London and New York.

- Vollmer, B., and S. Karakayali. 2018. “The Volatility of the Discourse on Refugees in Germany.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 118–139.

- Wekker, F. 2019. “‘We Have to Teach Them Diversity’: On Demographic Transformations and Lived Reality in an Amsterdam Working-class Neighbourhood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 89–104.

- Wessendorf, S. 2013. “Commonplace Diversity and the Ethos of Mixing: Perceptions of Difference in a London Neighbourhood.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 20 (4): 407–422.

- Wise, A. 2005. “Hope and Belonging in a Multicultural Suburb.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 26 (1–2): 171–186.