ABSTRACT

Eastern Europe has seen considerable social, economic and political upheaval since 1989. Migration has been an important element of this change, with the removal of restrictions enabling individuals to move in search of opportunities. Resulting patterns of internal migration rest on a longer history of movement, linked to the communist-era pursuit of economic development and modernization. Proximity to Western Europe has seen some regions receive greater migrant flows, leading to resentment and distancing among the resident population. Focusing on rural settlements in the Banat region, southwestern Romania, this article examines how receiving communities perceive the effects of internal migration. The findings suggest entrenched stereotypes established during the communist-era remain prominent in patterns of stigmatization and maintenance of social distance. They also point to underlying tensions between the desire to protect local culture and tradition, while ensuring the continued viability of small settlements in the face of threats of depopulation.

Introduction

Graffiti in Timişoara with statements such as ‘Olteni Go East!’ raise questions around issues of identity and belonging (Radu Citation2013). The term Olteni refers to people from Oltenia in Southern Romania. The graffiti suggests migrants from the region are not welcome in the Banat region, but by telling them to go East it asserts a clear divide between Banat and less developed Eastern Romania. These attitudes can be traced to the respective histories of the regions, as Banat and neighbouring Transylvania were part of the Habsburg Empire until 1918 when they were unified with the so-called old Romanian provinces of Oltenia, Muntenia, Moldova and Dobrogea. The sense of superiority amongst the Banateni leads to a feeling that migrants from the other regions are perpetuating a form of cultural homogeneity that does not fit with locally distinct traditions and practices. Similarities with the Romanian Banat case can be found in migrants moving from Southern to Northern Italy (Biagi, Faggian, and McCann Citation2011; Gattinara Citation2016) and Eastern to Western Germany (see Buch et al. Citation2014; Bertoli, Brücker, and Fernández-Huertas Moraga Citation2016), illustrating the directionality of internal migration. Migration flows are often driven by local and regional economic disparities, which can mean competition for resources and questions about belonging. Stigmatization plays an important role in establishing and reinforcing social order, with incomers being characterized variously as rustics (Guan and Liu Citation2014) or ‘indigent, violent and uncivilized’ (Capussotti Citation2010, 121).

The case of migrants in Banat demonstrates the need to consider the more nuanced reality of internal migration, especially for the migrants settled in rural areas. Stigmatization of outsiders can be an important means of reinforcing a sense of community, meaning this may appear as a simple case of resistance to outside influences. However, the legacy of communism in Romania adds another layer of complexity, as internal migration during this period was directed by the state (Rotariu and Mezei Citation1998). Migration was a tool of economic development, with the state moving groups between regions to satisfy its interests, meaning incomers could be seen as representing the interests of the state, making them doubly unwelcome (see Rotariu and Mezei Citation1998). The fall of the regime in December 1989 provided greater opportunities for movement, but the underlying economic disparities did not disappear.

The aim of this article is to consider how select communities in the Banat region perceive the effects of internal migration on their community. It examines attitudes of people living in rural Banat to determine the extent to which stigmatization towards migrants persists and links to the preservation of local identity and culture. The article is divided into five sections. The first section examines the relationship between internal migration and stigmatization, as it relates to the desire to maintain a sense of collective identity. The study area and methods used are outlined in the third section. The context of migration to the Banat region during the communist and post-communist periods is examined in the third section. The fourth section draws on interviews with native and migrant residents of three villages in Banat to identify the patterns of stigmatization. The final section discusses the findings from the research to consider how migrants are received and perceived by Banat residents.

Collective identities, stigma and internal migration

Collective identities play an important role in shaping the characteristics of communities, establishing unwritten rules around whether individuals and groups are accepted or rejected. Defining collective identity, Hunt and Benford (Citation2004, 447) argue ‘it is a cultural representation, a set of shared meanings that are produced and reproduced, negotiated and renegotiated, in the interactions of individuals embedded in particular sociocultural contexts’. Collective identities are fluid, subject to changing expectations and values, as determined by members of the community. Benefits are derived from adherence to these norms and practices, as they reduce information costs, allowing participants to rely on general guidelines. The costs associated with maintaining a collective identity are derived from the need to police boundaries, as cohesion suggests the presence of an ‘other’ against which the group can be defined. The form of the other is not necessarily important, as Capussotti (Citation2010, 134) argues ‘otherness is above all a construction of the dominant self and not necessarily connected with the presence, values, or character of the other’.

The importance of collective identity can be illustrated by considering how it relates to trust. Trust is grounded on the expectation that another party will fulfill expectations. Repeated exposure can strengthen trust between parties, as past behaviour can serve as a guide for future behaviour, generating certainty (Möllering Citation2001). Anheier and Kendall (Citation2002, 350) capture the significance of trust in shaping relations, particularly between thick (particularistic) trust based on shared identity or experience and thin (social) trust ‘based on everyday contacts, professional and acquaintance networks … form[ing] less dense networks’. Key to the difference is the frequency and intensity of interaction. Just as collective identity relies on repeated, shared experiences, trust relations are similarly shaped by factors such as proximity and shared experiences. Unreliability and weakness of institutions that were a legacy of communism led to a reliance on informal, social relations and a wariness of outsiders (see Lagerspetz Citation2001).

Stigma serves as another mechanism by which collective identities can be maintained and strengthened, reinforcing the sense of distance from the other. Link and Phelan (Citation2001, 367) argue stigma concerns situations ‘when elements of labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination co-occur in a power situation that allows the components of stigma to unfold’. This highlights the significance of power differentials in the roles of stigmatizer and stigmatized. Sources of power are diverse, but can relate to social, economic or political resources (Link and Phelan Citation2001). Stigmatizing also simplifies the social world, allowing rapid judgements regarding the standing of individuals and groups. Being a socially embedded process, Guan and Liu (Citation2014, 77) argue that:

stigma is a deeply interactional phenomenon, taking place between people in a given context … . requires attention to the interrelations between the stigmatizer and the stigmatized, and between individual processes and social processes.

The place-based nature of stigmatization means that it can become entrenched as certain areas are associated with excluded groups, reinforcing these processes (Wacquant Citation2008) and preventing communication that can support the reduction of stigma (Yan and Bresnahan Citation2019).

Migration is a key target of stigmatization. At its simplest level, Borozan (Citation2017, 142) notes that ‘Migration refers to the movement of migration units (persons or families) in space having as a consequence a change in their place of permanent residence’. Distinguishing between international and internal migration, King and Skeldon (Citation2010, 1621) note that ‘[l]inguistic and cultural barriers … may be more evident in internal than in international moves’ in some cases. The reasons for migration vary considerably from case to case, but as Toma and Fosztó (Citation2018, 71) argue it is generally assumed that ‘mobility bring[s] the promise of upward social mobility’. This can be seen when considering internal migration where rural to urban movements feature significantly, as ‘urban centres accumulate benefits in terms of job creation … and higher levels of engagement in a variety of political and innovation networks’ attracting migrants from less favoured regions (Moldovan Citation2019, 227–8). This can lead to shifts in the demographic make-up of sending and receiving communities, as ‘local moves tend to be tied to life-cycle changes and long-distance moves to job-related reasons’ (White and Lindstrom Citation2005, 321), amplified by differences in ability to migrate (Cazzuffi and Modrego Citation2018).

Internal migration presents a challenge when it comes to patterns of stigmatization, as the extent of difference is likely to be reduced by shared national identity. Familiarity can lead to more developed forms of labelling based on small differences, as it presents greater potential challenge to the recipient community’s collective identity. Despite opportunities represented by migration, Capussotti (Citation2010, 135) reminds us there is a ‘fundamental disparity in which geographic origins, cultural resources, and economics are interwoven’. There are costs associated with migration, as newcomers lack local information and personal ties (White and Lindstrom Citation2005), although they are more able to ‘maintain close connections between home and destination’ (White Citation2007, 887). Guan and Liu (Citation2014, 78) argue that:

Knowledge of rural-to-urban migrants is … shaped, not only by present-day socio-economic realities and societal ideologies in circulation but also by long-standing understandings of the meaning of urban/rural divisions and internal migration.

This is in spite of the fact that migrants tend to be better educated and more employable (King and Skeldon Citation2010), pointing to the intangible character of stigmatization.

Study area and research method

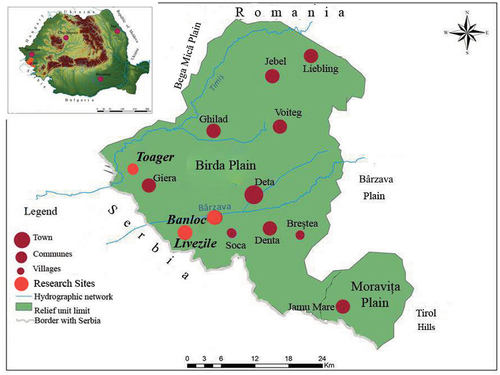

The study area near the Romania-Serbia border is one of the most ethnically diverse areas in Romania. From the physical geography point of view, it belongs to the Romanian Banat Plain, one of its subdivisions named Birda-Moravita Plain (Covaci Citation2016), in south-western Romania (see ). Since 1918 there were three stages of internal migration in the region: interwar migration, communist migration and post-communist migration. Our study is based on a mixed methods approach, combining an analysis of official sources, secondary data, and semi-structured interviews.

Figure 1. Selected research sites in the Romanian Banat region.

Part I: Official sources

We used several sources of statistical data: the last Romanian census (Romanian Census Citation2011), data provided by the Institute for National Statistics in Romania (Tempo online Citation2021), the pre-communist Romanian censuses (1930 and 1941 censuses). In communist times (1955, 1966 and 1977 censuses) and the early post-communist Romanian censuses (1992 and 2002). A first stage of our investigation was to analyse the evolution of the population and the share of migrants in the villages. This distribution was determined by the size of the villages, Banloc being a bigger settlement than Livezile and Toager. Population size of the three research sites was almost 3000 inhabitants – 2853 people – at the last official Romanian census (Romanian Census Citation2011). Generally, the selected sites are rural areas with ageing populations.

Part II: Secondary data

Secondary data provided a picture of the regions and settlements during the communist period (Baranovsky Citation1984) and an understanding of migration in the early post-communist period (Rey, Groza, and Muntele Citation1998). This data was obtained from books and online databases for detailed assessment of the village level (Varga Citation2002). Primary and secondary data were useful in presenting our narratives related to the historical context of the area and the tensions created among natives and migrants at the local level. Key periods of migration to our three research sites were early communist times (1947), mid- and late communism (1960s-1990s) and post-1990 (). Romanian migrants in Banloc came from Moldova in 1960s, Maramures in 1970s and Oltenia in 1990s. In Toager migrants came from Moldova and Bessarabia in 1947, Oltenia in 1970s and Maramures in 1980s, while in Livezile they came from Transylvania, Moldova and Oltenia in 1970s and 1980s. Excluding the post-war migrants from Moldova/Bessarabia, all the other migrants were attracted by the Banat welfare and were interested to work in agriculture.

Part III: Semi-structured interviews

The research presented here also draws on a sample of 51 semi-structured interviews (). The interviews were conducted between 30 July 2019 to 1 October 2019, with a duration of interviews between 17 and 45 minutes. Covaci conducted the interviews as part of her postdoctoral entrance at West University Timişoara. In order to ensure that participants’ were taking part willingly, they were asked to read and sign a consent form prepared by Covaci, under the guidance of Creţan and Jucu. Participants were also asked if they were willing for the interview to be recorded, six agreed and written notes being taken during the interview for the remaining 45. The interviews were conducted in the villages of Banloc (27 participants), Livezile (14 participants), and Toager (10 participants). Questions covered birthplace/region of origin, perceived social distancing towards newcomers, use of stereotypes and their frequency, and acceptance of migrants. Among the 51 interviewees 31 declared themselves as native Banateni, while 20 considered themselves to be of other Romanian origin (Transylvania (5), Oltenia (5), Moldova (3), Crişana (3) and Maramureş (4)).

The interviewing and transcribing was done by one of the authors (Covaci) who is resident in Banloc, while interpretation of the data was made by three authors (Covaci, Creţan and Jucu) initially with a fourth author (O’Brien) joining later to assist with analysis. The process of data interpretation was done through reviewing quotes assembled to several themes related to our major lines of investigation: origin of interviewees (natives or migrant), distancing towards the migrants, and cultural forms of integration towards migrants. We followed Bryman’s (Citation2016) steps in interpretation of qualitative data, selecting more precise themes from broader themes, discarding those themes and ‘lower level’ quotes which were not closely related to the aims of our article. The three themes are presented subsequently in our results section by including for every theme an assemblage of narratives based on our selection of participants’ ‘higher level’ quotes.

Patterns of internal migration in Romania

Internal migration in Romania between regions and counties, has consistently been connected to economic development. Under the communist regime, the development of urbanization, alongside the industrialization and economic development of agriculture, required people to move from rural to urban areas. Population mobility was strictly controlled by the state in order to ensure a balanced development of regions (Kligman Citation1998). Migration occurred especially from poorer regions to developed counties, where better job opportunities were located. For instance, mining areas (see Vesalon and Creţan Citation2013; Toader, Creţan, and O’Brien Citation2022) as well as metallurgical towns and cities were attractive sites for domestic migrants. Therefore, internal migration was designed as a driver for local and regional development. Patterns of mobility saw out-migration from regions such as Moldova, Oltenia, Transylvania and Maramureş. The western region of Romania and the capital Bucharest remain some of the most developed areas, meaning they continue to fuel internal migration. Even though migration occurred from urban to urban environments, from urban to rural areas, from rural to urban and from rural to rural areas, the western part of Romania was among the top migrant destination (Rotariu and Mezei Citation1998). This is because the region has been always in a state of continuous economic development both during and after communism.

In communist Romania, the rapid pace of industrialization and urbanization influenced the higher rates of migration between 1960 and 1980. The main movement was directed towards urban areas (small and medium-sized towns) and to rural areas where industrialization was implemented alongside agriculture (Baranovsky Citation1984). Regional magnetism of attraction was an important feature in communist era migration (Ianos Citation1998), meaning that alongside Banat, the highly industrialized areas of Cluj, Brasov and Bucharest were strong attractors. From 1980 a decreasing trend in internal migration was recorded due to apparent homogeneity in both industry and agriculture. In the 1980s Nicolae Ceauşescu’s idea was to pay the entirety of Romania’s foreign debt, creating a shortage of food on the Romanian markets. This brought a general impoverishment of population in all regions of Romania, which led to lower levels of internal migration. After the regime change in 1989, individuals ‘regained freedom to change the residence’ related to the need of cultural identity and individual choice (Rey, Groza, and Muntele Citation1998, 78) reshaping traditional patterns of Romanian internal migration. Over this period, the rate of internal migration was 12.9% in 1992 and 13.0% in 1996, with the western part of Romania being preferred by the newcomers next to the Bucharest region. For example, Timis and Arad counties maintained higher rates of in-migration, with 48.9% and 26.6% respectively in 1996 (see Rotariu and Mezei Citation1998). The main areas of origin continued to be counties from the Moldova region as well as counties from Oltenia (especially Gorj, Mehedinti, Olt and Dolj).

Massive industrial restructuring and deindustrialization, privatization and changes in Romanian agricultural and industrial sectors largely influenced the internal movements thus generating new paths in the local and regional movement of people. After the end of the communist regime, there was a return to rural areas, linked to urban industrial decline and failures in Romanian agriculture, as people moved in search of economically attractive areas (Rey, Groza, and Muntele Citation1998). In this regard, the western part of Romania remained attractive after communism due to its higher level of economic development based on close connection with countries from Western Europe (Popescu Citation2012). A specific instance was female migrants who came from regions such as Moldova, Transylvania and Oltenia due to textile and light industry development in small and medium-sized towns and even rural settlements of Banat. Meanwhile, the emergence of heavy industry attracted male migrants, especially from Oltenia and Transylvania (see Jucu Citation2009). These issues influenced the relevance of class and gender in the regional landscape of the Romanian in-migrants background (see Boyle and Halfacree Citation1998). Universities also played an important role in the context of inter-regional and regional migration as they are important poles of attraction both at the national scales (see Ilieș and Vlaicu Citation2014) and in the Banat region. The Polytechnical University and the West University in Timisoara were both important magnets of internal migrants to the region (Munteanu and Munteanu Citation2004) because some of the graduates and professionals remained in the region.

Against such a background, paths of cross-cultural connection have resulted in an apparent forming of cultural homogeneity among the migrants. This has resulted from the collective residence of migrants in standardized buildings designed under communism for working class reproduction (Petrovici Citation2012). Frequently migrants were adapted in their new places and often developed relevant cultural connection with the locals. However, they maintained their cultural traditions in terms of linguistic dialects, their sense of belonging, and their aspirations in the new living conditions. Considering the attitudes and beliefs about migrants illustrates the strength of identity. It is argued that ‘Olteni’ migrants to Banat and western Romania are seen as authoritarian, courageous and ambitious (Manea and Mitrache Citation2015) while ‘Banateni’ were seen as tolerant, but at the same time evincing frustration towards migrants (Both Citation2015). On the other hand, ‘Moldoveni’ are honest and hard-working but poor (Marchitan Citation2017). Although these were newspaper opinions, such references should be taken into consideration with caution, as local and regional journalist positions are defending local people and cultural values. Despite the above-mentioned homogenous co-habitation, some tensions may occur based on the cultural allegiance of different groups to their native beliefs and to their pride as being representative of one of Romania’s historical regions. Pride is evident in different local and regional cultural activities in Banat region, for instance local football fans in Timișoara perceive with cultural superiority the fans and clubs from other clubs in Romania (see Creţan Citation2019).

The question of newcomers in different areas connected to their cultural background and their integration in new rural places remain an interesting avenue in examining the cultural identity of Banat people since they co-habited for decades with different individuals and families in this region because of Romanian in-migration both under communism and afterwards. On the other hand, migrants are an active and agentic category of population and the nature of migrants accommodated in the rural Banat could generate some forms of vilification for ‘the Romanian others’ because of cultural traits. Therefore, provincialization may appear as an in-between process with both positive outcomes in the local rural identity formation and with some negative results for the post-communist citizens of rural Banat. Furthermore, as Costello (Citation2007) argues, migrants in different regions and places could be responsible for division between traditional residents and migrants, possibly resulting in tension between different cultural groups (Boyle and Halfacree Citation1998). Considering these tensions can assist in the identification of the extent to which stigmatization shapes patterns of internal migration in Romania.

‘A little coldness exists’: attitudes towards migrants in Banat

In order to understand the attitudes towards internal migrants in Banat the following section considers the reasons people migrated to the region, how they were perceived, the ability of locals to identify with incomers and how migrants are classified and discussed.

Examining the reasons for migration to the Banat region, we found the availability of economic opportunities to be a key draw. This was also recognized by residents, as the agricultural sector struggled to find workers, as residents preferred to find better paid work in nearby towns (such as Deta and Gataia). An agricultural worker (Ro19) from Livezile described the migrant experience as follows:

they came for working in agriculture of Banat, where payments were better and life standard of population was higher than in the regions they came from. IAS offered them good service and cheap renting homes in the houses nearby the factory … . Their adaptation to the Banat Plain and to the Banat Western style was not sudden, it happened gradually.

This aspect illustrates the communist migration when people from all-through Romania came to Banat for a wide range of reasons. In addition to economic opportunities the region had other attractions, since Banat region is considered a model region for inter- and multi-culturalism, providing opportunities to live in a region with a multicultural identity (see Covaci Citation2016; Creţan, Covaci, and Jucu Citation2021). Reflecting on this, an elderly resident (Ro1) of Toager noted:

Yes, the village was provincialized with people from other regions of Romania. Provincialization is an important aspect in our locality, especially after 1966 when the village was provincialized with people arriving from Transylvania, Moldova and Oltenia. I consider this issue has been beneficial for the locality, otherwise the villages would be dismantled or abandoned.

These two perspectives demonstrate the recognition of the importance of internal migration for the community.

Recognition of need did not necessarily result in acceptance, even among those with experiences of migration. This was reflected by a pensioner (Ro22) from Banloc who was forcedly resettled under the communist regime to harsh Baragan region from 1951 to 1955. Discussing the presence of migrants, she argued:

there were many who came and settled here in Banloc and also in Livezile … . I don’t think this was a good thing because they came in too higher numbers (especially Moldovans) and I think the Banat identity got lost.

The sense that the arrival of migrants from across Romania could result in the alteration of cultural values as well as of various aspects of identity and belonging was echoed by other residents. A resident (Ro24) of Toager noted:

the migration determined that the already ageing village has been refreshed, but on the other hand, Banat rural traditions have been lost … Rarely I can hear on the streets of the village people who talk with Banat accent, cannot hear the Banat dialect anymore.

Migrants, through their culture, have the power to reinforce the local and regional culture mixing their own cultural traits with the indigenous cultures thus ensuring a certain intercultural background in areas threatened with the loss of language, customs and specific ways of life. The shifting character of the population has changed the community, which was seen as a threat by some residents.

Addressing issues of social distance between the host community and migrants, a local leader (Ro33) argued:

I think that in communism when they settled here there was a social distance between the natives and the newcomers, but now it no longer exists, it doesn’t make a difference between the locals and the newcomers. In the past they didn’t communicate that much, the newcomers were more reluctant to talk to natives and the natives were very cold and stayed in closed families

Despite this apparent acceptance and the role of migrants in ensuring the viability of small settlements, tensions between local people and migrants remain, shaped by the internal spatial structure of communities, as well as their local landscapes. Discussing her attitude to migrants, a resident of Toager (Ro9) stated:

a little coldness exists because those who come were not very sociable, they deal with gossip and lies, you need to know what to talk to them about. I had very little talk to them, but I don’t have a relationship, friendship or collaboration. If you borrow something to them, they won’t give back anything and then they are not working too hard

These tensions may lead to the rejection of specific cultural attributes of individuals and groups coming from other regions.

Language and labelling were identified as important features in the relationship between migrants and residents. A prominent example of this is the use of the term ‘vinitura’, derived from ‘vinit’ in Banat dialect to mean newcomer, but in a pejorative sense. Discussing the power of the word, a teacher (Ro48) in Banloc argued ‘The term vinitura was used to show the natives’ annoyance towards those who came and took natives’ houses and jobs’. The term vinitura articulates distance and disdain towards migrants and especially to the Olteni. Furthermore, one person who was considered a mixed Banat-newcomer (Ro51) stated:

Vinitura was used more in the past only for those who were doing problems in the village (now they are not, but in the past there were battles and scandals in local bars and at CAP and IAS, especially from those who came). Even are not so keen, that we have been lazy not to give birth to many children, you know the saying: if a Banat family could make half a child, they will do it

The label also has a stickiness, meaning it is difficult for someone to cease being vinitura, with a teacher (Ro18) noting his mother who was born in Banat carried the label, as her parents were from Bihor. The term vinitura is not only specific to Banat, as Cristea, Latea, and Chelcea (Citation1996) highlighted that the local community in Santana, a village in the Arad county also used the label.

Attitudes towards migrants were also reflected in the way residents drew on stereotypes to distinguish them from Banateni. This form of stereotyping is a mechanism for reproducing social distance and reinforcing a sense of collective identity in the face of change. Discussing migrants, residents made statements like ‘people coming from Oltenia wants to be only chief/boss here and are quite lazy, while Moldovans are hard workers but like to drink too much’ (Ro22). Negative views were balanced by more positive interpretations of another participant (Ro10) who argued ‘Maramureş men deal with agriculture and animal husbandry … [they] are very jumpy, they help you even without money when they can’. This suggests differences in the way migrants from different regions are perceived. Pointing to a more nuanced reality, one participant (Ro16) argued:

We joked with expressions such ‘this stinky Oltean’ or ‘that poor Moldovan’, or even ‘tu, sarma’ [’you, wire’] for Moldovans because they came by trains from Moldova and trains were so crowded they came on the roofs functioning as a wire for the trains, but I have never used vinitura because this term is based on foolish pride of local Banat people.

In this way Banateni, are able to reflect on their own stereotypical characteristics that may hamper integration of migrants. Describing this character, a participant (Ro25) noted ‘Banat natives are more cold, selfish, they have a typical German style’, pointing to another stereotype to illustrate the point.

The attitudes of residents in Banat demonstrate the complex character of internal migration. Although they recognize the benefit of people coming to the region to work and help ensure the viability of villages at threat of depopulation, they also express concern about the implications for their traditional cultural practices. Attempts to bridge the divide between Banateni and migrants was apparent among participants, although these were shaped by attitudes towards outsiders. This was represented by a participant (Ro17) who argued:

I have always had a very good relationship with them [migrants], I also had friends from Moldova, Oltenia. I collaborated very well both at school and at work. I think it does not matter where you came from, it matters the character of every people.

This viewpoint leads us to better think about the sense of understanding of the migrants as ‘different’ but belonging to the same ethnic group of Romanians. This familiarity can be seen in the use of stereotypes that provide Banateni with a way of characterizing migrants and position themselves in response. It also demonstrates a degree of familiarity with the customs and origins of those migrating to the region, as demonstrated by a participant (Ro16) who referred to the ‘hilly and mountain areas the settlers came’ from.

Among our interviewees we identified three categories of stigma, with no clear-cut distinction on gender. A harsh stigma propagated among middle-aged and older native people with lower education. Indicators included expressions connected to the colour of a migrant’s skin (e.g. Oltenian Gypsy), the word ‘vinitura’, and the use of offensive terms against migrants. By contrast, hidden stigma propagated mainly among mid-aged local intellectuals and involved softer expressions in which the language of stigma is nuanced and included in everyday jokes and legends/stories about the migrants. Finally, latent stigma was perceived generally by the more younger native and second/third migrant generations (under 30 years-old). The younger people are more integrative and rarely used harsh forms of vilification because in recent decades there have been very few migrants established in the village. Moreover, most of the second and third generation of migrants consider themselves as ‘Banateni’. On the other hand, we could not find clear-cut connections between certain types of regional stereotypes and our interviewees profiles, because stereotypes related to migrants origins such as ‘alcoholic Moldovans’, ‘tricky Oltenians’ were circulating in the narratives of almost all interviewees with Banat roots.

Discussion

The Banat region has seen considerable in-migration, as a region with stronger economic performance than the regions of origin (see Moldovan Citation2019). This has led to a reshaping of rural settlements, as migrants replace local residents who increasingly relocate to urban areas in search of economic opportunities. A considerable volume of internal migration occurred between Romania’s regions under the communist and post-communist regimes as a consequence of social and economic conditions. A large part of this migration took place during the communist era, as a result of Ceauşescu’s drive for industrialization and urbanization. Following the end of the communist regime, rural areas offered opportunities for land acquisition, as urban areas experienced widespread deindustrialization and unemployment. The legacy of these patterns of migration are apparent in the findings outlined above, as the origin of migrants and their descendants has played an important role in determining their position within the community. This echoes Capussotti’s (Citation2010) finding that geographic origins carry with them assumptions about the individuals concerned.

The strength of collective identity was apparent in the findings, as participants referred to their position in relation to individuals and groups from other regions. Central to this was the labelling of other groups, pointing to both positive and negative aspects, such as the hardworking Moldovans and the lazy Oltenians. Drawing on Link and Phelan (Citation2001), it is clear that these labels are deployed to highlight the power differential between local residents and migrants. Similarly, the term ‘vinitura’ can be seen as a way of identifying the migrant population as a whole, making it difficult for individual migrants to escape the reach of stigmatization. As Cristea, Latea, and Chelcea (Citation1996) argued, vinitura is a form of narcissism and reproduction of superiority for the locals against the newcomers. This echoes the work of Capussotti (Citation2010) in Italy and Guan and Liu (Citation2014) in China, where migrants were labelled and marked as different. In marking out these differences, local residents are attempting to simplify the social world, creating expectations around the behaviour of certain groups, regardless of whether these are accurate. This also works to reinforce the collective identity of the native Banateni, enabling them to maintain a sense of shared characteristics and beliefs. Characterizing themselves as cold and selfish further feeds into the sense of Banateni collective identity and reinforces patterns of stigmatization, as it potentially excuses the attitudes of some.

In a related manner, the breakdown of the communist regime and the uncertainty that followed generate a need for measures to maintain connections that can ensure the achievement of goals. Drawing on Lagerspetz’s (Citation2001) classification, it is possible to argue that marking out migrants from different regions enabled people to determine who they could trust and how those bonds could be maintained. By marking migrants out as problematic and potentially untrustworthy, residents of Banat can be seen as maintaining an emphasis on closer contacts. In successive periods of communist control and post-communist fragmentation, the ability to identify those deemed trustworthy is central to success, reducing the costs of failure. While migrants are identified as necessary to ensure the survival of small communities, maintaining social distance in this way ensures that local traditions and cultural practices can be protected. They also potentially limit the possibilities for migrants to become an accepted part of the community, as they are unable to shake the labels that have been attached. These labels also influence how migrants view their new communities, complementing recent research on regional profiles of attachment and local identities in Romania. In their study of street and monument (re)naming, Rusu and Croitoru Citation2022, 144–147) pointed out significant differences between natives and internal migrants in terms of attachment to the region of residence (including the Banat) in Romania. Rusu and Croitoru argue that internal migrants self-assessed significantly lower levels of local and regional attachments as a result of discrimination, stigmatization and social distancing.

The persistence of internal migration flows demonstrates a need, regardless of the attitudes migrants face on arrival. As Toma and Fosztó (Citation2018) argue, the drive to migrate is premised on the idea that it will result in upward mobility. Shifting demographic patterns in Banat, as residents move to urban areas, results in the need for migrants to prevent depopulation and the collapse of smaller, rural communities and associated their services. This is reflected in the attitude of respondents who note the nature of change within the community and the fear that it would not survive without new residents. This results in a tension, as the arrival of migrants from other regions may sustain the community at the expense of local cultural practices and dilution of identity. This was captured in statements around the loss of recognizable features such as accent and dialect, standing in for a more fundamental loss of identity. Moreover, internalization of stigma is evident for some minority groups (such as the Roma people are) even in areas of the Banat region situated beyond the Romanian border (Creţan, Málovics, and Méreiné Berki Citation2020). To these aspects the questions of self-identity, the other and local pride are relevant aspects in defining different pathways of the local acceptance or non-acceptance of the newcomers. They, as individuals and their cultural traits and customs as well as their ways of life, are both accepted or rejected according to the local cultural values of the locals.

Conclusion

This article has examined attitudes towards internal migration in the region of Banat in Southwestern Romania. As a region with a strong traditional collective identity, Banat presents an interesting case with which to examine questions of local acceptance of migrants. Social, economic and political drivers saw migration from other regions of Romania in search of opportunities. They came to the region both under the communist regime and during the post-communist period and shared their experiences, practices, beliefs and aspirations with the local residents. In this way social and cultural relations were produced and reproduced generating different forms of acceptances or rejection. In general, such groups of migrants were accepted generating a friendly cohabitee and constructing new models of intercultural collective identities. But this general framework did not exempt the rise of some various ways of exclusion, discrimination, marginalization and even local stigmatization.

Such actions appeared as attributes of the local mentalities and identities based on the self-pride of Banateni . This is not a new or unique phenomenon since, generally, internal migration remains a key of stigmatization. What must be learned is that acceptance or, on contrary, the social distancing, discrimination or even rejection raised from the individual perception of the locals towards ‘the others’. And from ‘these others’ Olteni remain a group that face stronger forms of stigmatization, despite being a small proportion of the migrant population (5%-10%) in our selected sites of the rural Banat region. Graffiti targeting one group is perhaps more appealing in the urban space of Timişoara than in the rural areas of the Banat region. However, mentioning this regional group of origin and not others which seems be more prominent within the area is important in terms of reflecting a sort of undesirability toward the Olteni migrants. Furthermore, the crossed cultures in this region could learn from one to another and could shape new forms of identities at the local and regional scales. The findings of this study argue that these forms of particular exclusion have to be further investigated because they are meant to provide critical understandings on the intimate connection and relations between the people from different cultural backgrounds as well as to learn how we can see further migration not as a key of stigmatization but also as a process that could turn cultural differences of the people into new models of multiculturalism of the local collective identities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our respondents for their help in providing information for this article. Thanks are also due to the two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their fruitful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anheier, H., and J. Kendall. 2002. “Interpersonal Trust and Voluntary Associations: Examining Three Approaches.” British Journal of Sociology 53 (3): 343–362. doi:10.1080/0007131022000000545.

- Baranovsky, N. 1984. “Mobilitatea Teritoriala” [“Territorial Mobility”] ” In Geografia Romaniei. Geografie Umana Si Economica [Romanian Geography. Human and Economic Geography], edited by Badea, L., Cucu, V., 67–73. Editura Academiei: Bucharest.

- Bertoli, S., H. Brücker, and J. Fernández-Huertas Moraga. 2016. “The European Crisis and Migration to Germany.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 60: 61–72. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2016.06.012.

- Biagi, B., A. Faggian, and P. McCann. 2011. “Long and Short Distance Migration in Italy: The Role of Economic, Social and Environmental Characteristics.” Spatial Economic Analysis 6 (1): 111–131. doi:10.1080/17421772.2010.540035.

- Borozan, D. 2017. “Internal Migration, Regional Economic Convergence, and Growth in Croatia.” International Regional Science Review 40 (2): 141–163. doi:10.1177/0160017615572889.

- Both, S. 2015. “De Ce Sunt Bănăţenii Diferiţi” [Why are the Banaters so Different?.” Adevarul, 1 March. Accessed 19 January 2022. Available 19 January 2022 at https://adevarul.ro/locale/timisoara/de-banateanii-diferiti-ei-accepta-mai-usor-ungur-sarb-neamt-decat-oltean-moldovean–explicatii-sociologice-1_54f2f028448e03c0fd1a8b08/index.html

- Boyle, P., and K. Halfacree, ed. 1998. Migration into Rural Areas: Theories and Issues. Chichester: Wiley.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buch, T., S. Hamann, A. Niebuhr, and A. Rossen. 2014. “What Makes Cities Attractive? the Determinants of Urban Labour Migration in Germany.” Urban Studies 51 (9): 1960–1978. doi:10.1177/0042098013499796.

- Capussotti, E. 2010. “Nordisti Contro Sudisti: Internal Migration and Racism in Turin, Italy: 1950s and 1960s.” Italian Culture 28 (2): 121–138. doi:10.1179/016146210X12790095563101.

- Cazzuffi, C., and F. Modrego. 2018. “Place of Origin and Internal Migration Decisions in Mexico.” Spatial Economic Analysis 13 (1): 80–98. doi:10.1080/17421772.2017.1369148.

- Costello, L. 2007. “Going Bush: The Implications of Urban-Rural Migration.” Geographical Research 45 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00430.x.

- Covaci, R. N. 2016. “Construcţia Socială a Etniilor din Câmpia Birda-Moraviţa. Studiu Geografic” [Social Construction of Ethnicities in the Birda-Moraviţa Plain]. PhD Diss. Timișoara: West University of Timișoara.

- Creţan, R. 2019. “Who owns the name? Fandom, social inequalities and the contested renaming of a football club in Timişoara, Romania.” Urban Geography 40 (6): 805–825. doi:10.1080/02723638.2018.1472444.

- Creţan, R., G. Málovics, and B. Méreiné Berki. 2020. “On the Perpetuation and Contestation of Racial Stigmaː Urban Roma in a Disadvantaged Neighbourhood of Szeged.”Geographica Pannonica 24 (4) 294–310 doi:10.5937/gp24-28226

- Creţan, R., R.N. Covaci, and I.S. Jucu. 2021. “Articulating ‘Otherness’ within Multiethnic Rural Neighbourhoods: Encounters between Roma and Non-Roma in an East-Central European Borderland.” Identities: 1–19. Advance online Publication. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2021.1920774.

- Cristea, O., P. Latea, and L. Chelcea. 1996. “Vinituri Şi Ţigani: Identităţi Stigmatizate într-o Comunitate Multiculturală” [‘newcomers’ and ‘Gypsies’: Stigmatized Identities in a Multicultural Community ” In Minoritari, Marginali, Excluşi [Minorities, Marginal, Excluded], edited by Neculau, A., Ferreol, G., 159–169. Editura Polirom: Iaşi.

- Gattinara, P. C. 2016. The Politics of Migration in Italy: Perspectives on Local Debates and Party Competition. London: Routledge.

- Guan, J., and L. Liu. 2014. “Recasting Stigma as A Dialogical Concept: A Case Study of Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 24 (2): 75–85. doi:10.1002/casp.2152.

- Hunt, S., and R. Benford. 2004. “Collective Identity, Solidarity, and Commitment.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D. Snow, S. Soule, and H. Kriesi, 433–457. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ianos, I. 1998. “The Influence of Economic and Regional Policies on Migration in Romania.” In Romania: Migration, Socio-Economic Transformation and Perspectives of Regional Development, edited by W. Heller, 55–76. Sudosteuropa: Munchen.

- Ilieș, A., and M. Vlaicu, Eds. 2014. 50 de Ani de Geografie la Universitatea Din Oradea (1964-2014) [50 Years of Geography at the University Of Oradea, 1964-2014]. Oradea: Editura Universității din Oradea.

- Jucu, I. S. 2009. “Lugoj, the Municipality of Seven Women for a Man. From Myth to Post-Socialist Reality.” Analele Universităţii de Vest din Timişoara, Geografie 19: 133–146.

- King, R., and R. Skeldon. 2010. “‘Mind the Gap!’ Integrating Approaches to Internal and International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10): 1619–1646. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2010.489380.

- Kligman, G. 1998. The Politics of Duplicity. Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu’s Romania. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Lagerspetz, M. 2001. “From ‘Parallel Polis’ to ‘The Time of the Tribes’: Post-Socialism, Social Self-Organization and Post-Modernity.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 17 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1080/714003577.

- Link, B., and J. Phelan. 2001. “Conceptualizing Stigma.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 363–385. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363.

- Manea, M., and A. Mitrache. 2015. “Cum Sunt Oltenii Şi Oltencele? Ei - Glumeţi Şi Aprigi la Mânie, Ele - Înflăcărate Şi Rele de Gură? Mituri Analizate de Specialişti”. [How are the Oltenian Men and Women? are Men More Joking and Furious, and are Women Fiery and bad-mouthed? Myths Analysed by Specialists].” Adevarul.ro, 25 February. Accessed 20 January 2022. Available 20 January 2022 at https://adevarul.ro/locale/slatina/cum-oltenii-sioltencelee-glumeti-aprigi-manie-inflacarate-rele-gura–mituri-analizate-specialisti-1_54edbf95448e03c0fdf9c4e4/index.html

- Marchitan, A. 2017. “Cum sunt Moldovenii? Oamenii Noștri au fost Mereu Pașnici și Poate prea Toleranți [How are Moldovans? Our people were always peaceful and maybe too tolerant].” Timpul, 5 August. Accessed 20 January 2022. Available 20 January 2022 at https://timpul.md/articol/cum-sunt-moldovenii-oamenii-nostri-au-fost-mereu-pasnici-si-poate-prea-toleranti-109984.html

- Moldovan, A. 2019. “Out-Migration from Peripheries: How Cumulated Individual Strategies Affect Local Development Capacities.” In Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarization: Re-Thinking Spatial Policies in Europe, edited by T. Lang and F. Görmar, 227–252. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Möllering, G. 2001. “The Nature of Trust: From Georg Simmel to a Theory of Expectation, Interpretation and Suspension.” Sociology 35 (2): 403–420. doi:10.1177/S0038038501000190.

- Munteanu, I., and R. Munteanu. 2004. Universitatea de Vest Din Timișoara. Timișoara: Editura Universității de Vest.

- Petrovici, N. 2012. “Workers and the City: Rethinking the Geographies of Power in Post-Socialist Urbanisation.” Urban Studies 49 (11): 2377–2397. doi:10.1177/0042098011428175.

- Popescu, C. 2012. “Foreign Direct Investment and Regional Development in Romania.” Romanian Journal of Geography 56 (1): 61–70.

- Radu, C. 2013. “‘olteni, Go East!’ Pe Zidurile Timisoarei! Este Banatul Xenofob? Unii Moldoveni Sau Olteni Se Simt Discriminate [Olteni Go East! Is Written on the Walls of Timisoara. Is Banat a Xenophobic Region? Some Olteni and Moldoveni Could Feel Discriminated]”. Opinia Timisoarei, 2 April. Accessed 22 February 2021, retrieved 22 February 2021 from https://www.opiniatimisoarei.ro/olteni-go-east-pe-zidurile-timisoarei-este-banatul-xenofob-unii-moldoveni-sau-olteni-se-simt-discriminati/02/04/2013

- Rey, V., O. Groza, and I. Muntele. 1998. “Migrations and the Main Protagonists of Transition: A Stake in the Development of Romania.” In Romania: Migration, Socio-Economic Transformation and Perspectives of Regional Development, edited by W. Heller, 77–89. Sudosteuropa: Munchen.

- Romanian Census. 2011. Recensamantul Populatiei Romaniei din 2011 [Romanian Population Census 2011]. Bucharest: Institutul de Statistica.

- Rotariu, T., and E. Mezei. 1998. “Internal Migration in Romania.” In Romania: Migration, Socio-Economic Transformation and Perspectives of Regional Development, edited by W. Heller, 121–149. Sudosteuropa: Munchen.

- Rusu, M. S., and A. Croitoru. 2022. “Politici ale Memoriei în România Postsocialistă. Atitudini Sociale Față de Redenumirea Străzilor și Înlăturarea Statuilor.” In [Politics of Memory in Postsocialist Romania. Social Attitudes Towards Street Renaming and Statue Demolishing]. Institutul European: Iasi.

- Tempo online. 2021. “Date Statistice, Institutul National de Statistica Statistical data”. National Institute of Statistics, Bucharest. Available at http://statistici.insse.ro/shop/ Accessed 15 December 2020.

- Toade, R.N., R. Creţan, and T. O’Brien. 2022. “Contesting Post-Communist Development: Gold Extraction, Local Community, and Rural Decline.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 63 (4): 491–513. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2021.1913205.

- Toma, S., and L. Fosztó. 2018. “Roma within Obstructing and Transformative Spaces: Migration Processes and Social Distance in Ethnically Mixed Localities in Romania.” Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics 4 (3): 57–80. doi:10.17356/ieejsp.v4i3.396.

- Varga, E. Á. 2002. Temes Megye Településeinek Etnikai (Anyanyelvi/Nemzetiségi) Adatai 1880-1992 [Statistical Data of Ethnic Groups in Timis County, 1880-1992]. Accessed 25 June 2021. Available 25 June 2021 at http://www.kia.hu/konyvtar/erdely/erdstat/tmetn.pdf

- Vesalon, L., and R. Creţan. 2013. “Mono-Industrialism and the Struggle for Alternative Development: The Case of the Rosia Montana Gold-Mining Project.” Tijdschrift voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 104 (5): 539–555. doi:10.1111/tesg.12035.

- Wacquant, L. 2008. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Polity: Cambridge.

- White, M., and D. Lindstrom. 2005. “Internal Migration.” Handbook of Population, edited by Dudley Poston, and Michael Micklin, 311–346. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- White, A. 2007. “Internal Migration Trends in Soviet and Post-Soviet European Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies 59 (6): 887–911. doi:10.1080/09668130701489105.

- Yan, X., and M. Bresnahan. 2019. “Let Me Tell You a Story: Narrative Effects in the Communication of Stigma toward Migrant Workers in China.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 12 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1080/17513057.2018.1503319.

Appendix

a) Share of Population by Region in Research Sites (2018–2019) and period of migration

Appendix

1b: Participant characteristics