ABSTRACT

Deep canvasing is an effective organizing tactic that uses story-sharing to increase public support for equity issues. This correlational study examines 2,240 deep canvass conversations a community organization had with voters about a decarceration ballot initiative considered in Los Angeles County’s March 2020 election. We analyzed the relationships between story-sharing and emotional expression on increased support for the initiative using multivariate regression. The results suggest that story-sharing does predict attitude change, but only when combined with emotional expression. This study implies that organizers may increase their efficacy by utilizing narratives to facilitate the expression of emotions about political issues.

George Floyd, Andrés Guardado, Atatiana Jefferson, Dijon Kizzee, David McAtee, Breonna Taylor: these are just some of the people who were killed by law enforcement in 2020. The Black Lives Matter Movement has given shape to numerous protests and organizing campaigns against police violence and the carceral state more broadly, causing a shift in public consciousness (Pew Research Center, Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2016). Through its influence on the attitudes, policy preferences, and imagination of the U.S. polity, the Black Lives Matter movement is changing how carceral agendas are set and decisions are made. This influence has been particularly noteworthy on city and county governments, which have the most control over carceral institutions including police, sheriffs, and jails. The Minneapolis City Council voted to disband their police department (The Associated Press, Citation2020). San Francisco’s mayor called for all non-emergency 911 calls to be dispatched to non-police officers (Dolan, Citation2020). Los Angeles voters approved a policy that will divert 10% of unrestricted funds away from law enforcement and to community services and programs (Cosgrove & Thekmedyian, Citation2020). Thus, there is a movement toward abolitionist policies once framed as ‘too radical’ for adoption.

Abolitionist policies are characterized as those that reduce the funding and scale of carceral institutions and challenge the notion that policing, surveillance, and incarceration increase safety (Critical Resistance, Citation2020). Because abolition involves not just dismantling carceral institutions but also strengthening community health and power (Davis, Citation2005), abolitionist policies often include investments in community resources to prevent and address violence and the factors that, under our current system, often result in incarceration––such as mental health, addiction, unemployment, and houselessness.

As a complement to social movement periods that allow for mass shifts in consciousness, political interventions are needed to address the hesitations and concerns that hold people back from fully supporting a new political agenda or policy that would work toward the elimination of structural racism and promotion of decarceration––two of the Social Welfare Grand Challenges (American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare, Citation2021). Left unaddressed, these psychological holds could cause active backlash or passive lack of support for anti-racist policy change (Omi & Winant, Citation2015). By bringing together macro-level policy change and micro-level interventions, political social work can play a role in organizing to create lasting changes in dominant attitudes and policy opinions (Krings et al., Citation2019), such as through decreasing voters’ hesitations or concerns about decarceration and building support for abolitionist policies.

Policy opinions can sometimes be changed by providing new information, though this is typically only effective when a message is straightforward and individuals are already receptive to it (Slater & Rouner, Citation2006). In alignment with this knowledge, many organizing campaigns focus on providing information to likely supporters of an issue. This approach ignores the majority of U.S. voters who are persuadables––those who endorse a mix of progressive and reactionary political schema and could be moved in any political direction (Haney-López, Citation2019). With 24–39% of U.S. Americans supporting abolitionist policy proposals (Rakich, Citation2020), abolitionist organizers must find strategies to increase support among persuadables if they are to make concrete policy wins. Deep canvasing targets people who are not already supportive of a political issue, making it a compelling tactic to increase support for abolitionist policies.

Deep canvass organizing, which uses the sharing of personal stories to discuss political issues, has shown powerful evidence of sustained attitude change (Broockman & Kalla, Citation2016; Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020, Citationin press). In sharing relevant personal stories about political issues, voters often express emotions in a process akin to a brief political therapy session. This study examines a deep canvass community organizing effort aiming to increase support for Measure R, a decarceration ballot initiative approved in Los Angeles County in March 2020. Building on research on canvass organizing, narrative persuasion, and therapeutic change, we test the idea that story-sharing and emotional expression are core aspects of deep canvasing’s efficacy. Because this study does not use an experimental design, our results should be considered correlational.

Canvass organizing as a political intervention

Canvasing is a form of organizing in which volunteers are trained to knock on doors in a neighborhood and engage in political discussions with strangers. Traditional canvasing efforts focus on explaining why people should vote for a particular candidate or issue. Dominant ideology is the target of these forms of canvass organizing, in that it seeks to shift or activate the attitudes, policy opinions, and imaginations of residents. Canvasing systematically scales up micro-level interventions to target larger social systems, serving as a practical political intervention to link micro and macro levels of social change––a need that has been identified as essential in social work practice broadly and community practice specifically (Santiago et al., Citation2017). Canvasing can also serve an empowerment or leadership development function in providing community members with a concrete action they can take toward achieving a political goal, most typically in the context of an election (McKenna & Han, Citation2014).

Deep canvass conversations differ from traditional canvass conversations because they focus on the telling of personal stories rather than simply sharing information. After discussing the policy proposal and getting the resident’s opinion, the canvasser first asks about personal experiences with the issue being discussed. In the context of a decarceration policy, for example, the canvasser may ask the voter if they know someone who has been to jail or about a time someone they love experienced violence. Canvassers are instructed to ask follow-up questions of the voter to pull out more story details and attempt to elicit emotional expression about that experience. After stories have been shared, the canvasser provides specific information about the policy and only then attempts to persuade the person (Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020).

Four field experiments across eight different locations in the United States have shown that deep canvasing causes changes to both attitudes and policy opinions (Broockman & Kalla, Citation2016; Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020). Deep canvass organizing has reduced voters’ transphobia and increased support for transgender nondiscrimination policies. The intervention has also reduced anti-immigrant attitudes and increased support for pro-immigrant policies. While the effect sizes could be considered small from a statistical perspective, in practical terms they are large––which is centrally important for community practice social workers. There was little evidence of heterogeneous effects of the intervention on attitude change by voter education, economic well-being, race, partisanship, or level of political knowledge. Effects were significant regardless of whether the canvasser was an immigrant, Latinx, or transgender, showing that canvass effects are not the result of brief contact with a member of a non-dominant group. Remarkably, the attitude changes persisted for at least one to four months and effects withstood exposure to opposition messages. In the first experiment, the authors theorized that active perspective-taking––involving cognitively imagining one’s self in someone else’s situation––was responsible for the intervention’s effects (Broockman & Kalla, Citation2016).

Several experiments have examined possible explanations for the efficacy of deep canvasing. One experiment found an abbreviated information-sharing only intervention was ineffective, whereas the version with narrative sharing changed anti-immigrant attitudes and increased support for pro-immigration policies for at least four months (Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020). In building on this evidence that non-judgmental sharing of narratives was responsible for the intervention’s effects on attitude change, a series of additional experiments examined the effects of three different types of stories: perspective-getting (a voter hearing a canvasser’s story about an outgroup member), vicarious perspective-giving (a voter recounting an outgroup member’s experience), or analogic perspective-taking (a voter recalling a similar situation from their own experience; Kalla & Broockman, Citationin press). The field experiments demonstrated that the effects of a perspective-getting only intervention are comparable to those of an intervention including other types of story-sharing, suggesting that perspective-getting explains deep canvasing’s effects. However, additional evidence from a survey experiment found that analogic perspective-taking is also effective. Taken together, the results of Kalla and Broockman (Citationin press) comprehensive study suggest that perspective-getting and analogic perspective-taking are active ingredients that can explain the effects of deep canvasing. While it is clear that story-sharing plays an important role, more research is needed on specific mechanisms of deep canvasing and factors that moderate attitude change––which to date are largely unmeasured. This study contributes to this gap in knowledge, though we cannot make causal inferences given our non-experimental design.

Emotions as a moderator of narrative-sharing effects

Narrative persuasion theory explains how sharing stories can cause attitude change, given that stories are such salient forms of communication. People learn stories at a young age, easily understand their structure, and often think in the form of narratives (Green, Citation2008; Slater & Rouner, Citation2006). Through being “transported” into a narrative world, individuals integrate learnings from a story into their broader belief systems (Green & Brock, Citation2000). Narratives are particularly effective at changing attitudes when people might resist a persuasive message, as is likely with racialized and carceral attitudes. This is in part because people are much less likely to counterargue––a core barrier to persuasion attempts––when they are enjoying the flow of a story (Green, Citation2008). Rich story details and imagery as well as greater listener attention and feelings can lead to enhanced transportation and a greater persuasion effect (Green & Brock, Citation2002). Perhaps most importantly, people may personally identify or empathize with a story character, resulting in an emotional response.

Having an emotional response to a narrative can enhance its effects on attitude change (de Graaf et al., Citation2009). A narrative persuasion experiment found that people who were predisposed to approach emotions were more likely to experience transportation into a narrative, resulting in greater attitude change. Stories with high emotional content, in contrast to those with low emotional content, result in greater attitude change (Appel & Richter, Citation2010). Stronger emotions are more likely to affect behavior and result in the story being shared with others (Heath et al., Citation2001). Repeating a story out loud is itself an indicator of the integration of insights from a narrative with one’s own beliefs or attitude system.

Deep canvasing does not simply involve a canvasser sharing an issue frame or a personal story; a unique aspect of the intervention is the attempt to elicit a relevant, personal story from the person at the door. Decades of research on therapeutic interventions have provided evidence about the role of sharing stories and expressing emotions in individual-level change (Greenberg & Angus, Citation2004). Sharing stories is foundational to therapeutic change processes but is only effective to the extent that it elicits strong emotions. This element of the therapeutic process generally mirrors that of a deep canvass conversation. A person describes a past experience, possibly expressing the emotions felt at that moment, and shares its meaning. Reflecting on past experiences through stories allows for a person to access not only bottom-up emotional processing but also socially acquired cognitive schemas which were obtained or inferred from others, such as dominant ideological schema broadly and racial and political attitudes more specifically. In making apparent the schema one is holding onto while staying rooted in their personal emotions, a person is able to reconsider and make changes to their broader attitude structures and specific thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Greenberg & Angus, Citation2004). Understood in this way, then, expressing emotions has a direct effect on psychosocial change processes and enhances the effectiveness of story-sharing.

Current study

This study examines a deep canvass organizing campaign that aimed to increase support for a decarceration policy. Our research question is simple: does story-sharing or emotional expression predict attitude change toward a decarceration policy? We hypothesize that story-sharing, emotional expression, and their interaction––after controlling for other factors––predict increased support for the decarceration policy.

This examination occurs in the context of a deep canvasing campaign on a decarceration ballot initiative, Measure R. This policy aimed to decrease the jail population by diverting funds from jail expansion into community resources and giving subpoena power to the Sheriff’s Civilian Oversight Commission to investigate allegations of misconduct. In 2019–2020, 353 volunteer canvassers with a community organization, Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), and their local affiliate, White People 4 Black Lives, knocked on 18,120 doors and invited residents into a deep canvass conversation on the Measure R policy proposal. The organization strategically focused their canvasing efforts in majority White non-Latinx neighborhoods, which aligns with their focus of organizing White people on racial justice issues as part of a broader Black-led, multiracial movement.

The carceral policy opinions of White people are of particular concern to efforts to pass abolitionist policies. Through broader historical and structural processes, including the spatial construction of whiteness itself, White people are the numerical majority in all but four states and 89% of all counties (Krogstad, Citation2015; Lipsitz, Citation2006; U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2020). Due to the host of privileges provided to White people, they often register to vote and engage in politics at higher rates than other racial groups––despite some notable exceptions (McDonald, Citation2020; Public Policy Institute of California, Citation2020). White people then hold overly-proportionate political power even in areas where they are demographically in the minority (King & Smith, Citation2016). In Los Angeles County, for example, non-Latinx White people account for 43.8% of registered voters despite only being 26.1% of the population (NGP VAN, Inc, Citation2021; U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2020). In order for abolitionist organizers to advance their policy goals, it is essential that they find ways to address the attitudes of White people.

Method

Sample

Data come from 2,240 completed deep canvass conversations with LA County voters conducted from August 2019 through January 2020. See, for sample description. The sample skewed more Democrat overall (46.88%), though less so than the overall county average of 51.79% (California Secretary of State, Citation2020). The majority of participants were White (82.28%) and older (M = 59.52, SD = 15.96, 61.74% over age 55) than the average county registered voter (43.75% White and 34.41% over age 55; NGP VAN, Inc, Citation2021)––which was expected given that White voters were the strategic focal population of the community organization. The community organization chose to canvass in majority White neighborhoods that were generally accessible to canvassers––non-affluent areas with mostly single-family homes. Once neighborhoods were selected, canvassers were instructed to choose a starting point on their list of registered voters and systematically knock on every door as geographically ordered until their canvasing shift was over. Houses were occasionally skipped for safety reasons, such as a dog in the yard or explicit signage stating the person did not want to talk politics. The University of California, Los Angeles’ Institutional Review Board did not require a review of this study, given that it involved the analysis of de-identified secondary data from the community organization (#21-001831).

Table 1. Completed canvass conversation demographics

Procedure

The organization trained all canvassers on how to have deep canvass conversations and accurately record their data. Canvassers knocked on doors, first confirming the name of the voter and then introducing themselves as volunteers with SURJ who were there to discuss a local policy related to county jails that would be voted on in the upcoming election. Some voters immediately declined to engage in the discussion and others began to talk but did not complete the conversation. Full deep canvass conversations lasted an average of 15–20 minutes. After each contact, canvassers documented whether or not the person answered the door, refused to talk, or completed a full conversation; the voter’s baseline and post-conversation policy opinions; and if the voter shared a personal story or expressed emotion during the conversation. At the close of each canvass day, canvasser data were cross-checked to ensure paper and electronic data were complete and matched. Voter registration data (voter age, race, gender, and political party affiliation) and campaign information (prior canvasser experience and time into the campaign) were merged with the conversation-level data. More details on these variables will be discussed below. We used maximum likelihood multiple imputation to address missing data in our analyses of completed conversations (n = 303, 12%, 50 imputations), following the procedure described in von Hippel and Bartlett (Citation2019).

In preliminary descriptive analyses to understand the sample, we assessed the likelihood of voters answering the door, choosing to engage in a conversation with the canvasser (rather than immediately refusing), and completing a full canvass conversation in three separate logistic regression models. In each model, predictors included voter age, race, gender, and political party affiliation, prior canvasser experience, and time into the campaign. Of all those contacted (n = 16,376), 22.25% answered their doors (n = 3,643). Men were more likely to answer the door than women (OR = 1.19, p < .001); Republicans were less likely to answer the door than Democrats (OR = 0.87, p = .003), and Black, Asian, and Latinx voters were less likely to answer the door than their White counterparts (OR = 0.74; p = .01; OR = 0.71; p < .001; and OR = 0.83; p = .01). Older voters also had higher likelihood of answering the door (OR = 1.02; p < .001). For each year older, the odds of answering the door increased by 2%. For example, a voter 5 years older than average would have a 10% higher likelihood of answering the door and a voter 10 years older than average would have a 20% higher likelihood of answering the door.

Of individuals who answered the door, 17.12% refused to start the conversation. In a logistic regression examining the likelihood of engaging in a conversation rather than refusing, men were more likely to engage than women (OR = 1.42, p < .001), and Republicans were less likely to engage than Democrats (OR = 0.67, p < .001). Older adults were less likely to engage (OR = 0.99, p = .001), whereas greater time into the campaign and more canvasser experience were associated with a greater likelihood of engaging (OR = 1.08, p < .001; OR = 1.04, p < .001). Finally, of those who began a discussion, 84.69% completed the entire deep canvass conversation (n = 2,835). Canvasser experience was the only variable significantly associated with the likelihood of completing a full conversation (OR = 1.03, p = .003). For each additional time a canvasser participated, the likelihood of completing a conversation was higher by 3.44% compared to a new canvasser. Thus, for example, a canvasser who participated 4 times would have a 14% higher likelihood of completing a conversation.

Measures

Change in policy opinion

Our outcome variable is the difference in the Measure R policy opinion ratings before and after the deep canvass conversation. The canvasing script began with the following:

The initiative has two parts. The first part of the policy is about investing in alternative programs instead of building more jails. Are you in favor of or against building more jails in LA county? (voter replies) The second part of the policy is about oversight of the sheriff’s department, which oversees the jails. Specifically, it would give subpoena power to the civilian oversight commission. Are you in favor of or against increased oversight of the sheriff’s department? (voter replies). So the ballot measure would decrease our jail population by investing in alternative programs. It would also increase oversight of the sheriff’s department. On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is 100% sure you’re against this policy, 10 is 100% sure you’re in favor and in the middle is some uncertainty, where would you put yourself?

The initial policy rating is thus an 11-point Likert-type scale from 0 (100% against the policy) to 10 (100% in favor of the policy). In some early canvasing conversations, voters were asked the policy rating on each separate policy aspect. We averaged these ratings to create one overall baseline policy opinion score. This baseline policy opinion was controlled for in analyses, which is important as the intervention may have different effects on people strongly opposed to the policy than on people generally in favor. The baseline policy rating of the sample was more supportive of the policy than not (M = 6.44 on a 0–10 point scale, SD = 2.62). Of this sample, 8.01% had baseline scores opposing Measure R (score of 0–2); 37.60% supporting (score of 8–10); and 54.39% demonstrating ambivalence or being undecided (score of 3–7).

At the end of each canvasing conversation, the canvasser asked the voter, “To wrap-up let’s go back to that 0 to 10 scale, where 0 is 100% sure you’d vote against this policy, 10 is 100% sure you’d vote in favor and in the middle is some uncertainty, where would you put yourself?.” Change in Policy Opinion was constructed by subtracting the baseline policy rating from the post-canvass policy rating. Possible scores ranged from −10 to 10; the actual range in this study was −7 to 10, with negative scores representing increased opposition to the policy, higher scores representing increased support for the policy, and zeros indicating no change. The mean change score in this sample was 1.01 (SD = 1.64).

In addition to assessing change in policy opinion as a continuous variable, we also assessed change in policy opinion categorically. The policy scales were converted into categorical variables with three levels, following the model routinely used by the organizing campaign’s leadership: (0–2 = Opposed; 3–7 = Undecided/Ambivalent; 8–10 = Supportive). Of all voters who completed a canvasing conversation, 22.97% changed categories; all but 20 of these voters increased support for the decarceration policy. Of voters who did not begin with baseline support for Measure R, 35.54% substantively increased their support. We then created a binary variable to indicate if a voter moved up in a category toward support (1 = increased in support, 0 = decreased in support or did not change categories).

Personal story-sharing

Canvassers were trained to observe and report information immediately following each conversation. One of these items was “Did the person share a personal story?” (yes or no). Canvassers were instructed to choose yes if the voter told a story about a specific experience from their past related to someone who has been to jail, struggled with mental health or addiction issues, made a big mistake that could have resulted in incarceration, and/or been physically hurt by someone. Otherwise, canvassers selected no. The voter shared a personal story in 61.34% of completed conversations.

Emotional expression

Canvassers reported on the following item immediately after a conversation: “Did you make an emotional connection?” (yes or no). Canvassers were instructed to choose yes if the voter expressed any type of emotion during the conversation; this was defined as distinct from basic rapport-building, which would be expected in every conversation. Regardless of the specific type of emotion––for example, fear, anger, empathy, or pain––the canvasser simply reported “yes” for having made an emotional connection. Otherwise, canvassers selected no. Voters expressed emotions in 57.02% of all conversations.

Voter demographics

Because canvassers confirmed the name of each voter at the door, we were able to merge registered voter information with campaign data to create our model control variables of voter age, race, gender, and political party affiliation. Date of birth was used to calculate age in years at the time of the canvasing conversation. Race and gender were based on voter self-reported information at the time of registration, with White people and women serving as the reference group. Transgender and additional gender identities were not offered in the voter registration data. Political party affiliation was based on a voter’s registration with one of the following parties: Democrat, Republican, Unaffiliated, Libertarian, Green, Peace, or Other. The largest group, Democrats, was used as the reference group.

Canvasser experience

Deep canvass conversations could be more effective when they are led by an experienced canvasser; thus we control for canvasser experience. Based on campaign data, each conversation was given a value of nth time the volunteer canvasser had deep canvased with the Measure R campaign, including during several practice canvasses before the official campaign launch. Conversations with a first-time canvasser, for example, were given a value of 1. Conversations with a canvasser on their 6th day canvasing with the campaign were given a value of 6. Scores ranged from 1 to 23, with an average of 4.14 (SD = 4.37).

Time into campaign

The effectiveness of deep canvass conversations may also differ depending on the time they occurred during the campaign. In conversations toward the end of the campaign, voters are more likely to have some prior background information on the policy; whereas they are more unfamiliar with the policy when the campaign first began, nine months before election day. Each conversation was given a value of nth canvass based on how many canvass days had occurred prior . Values ranged from 1–19, with an average of 12.50 (SD = 5.10). The range of values for this variable reflects campaign breaks during holidays and their switch from deep canvasing to voter turnout canvasing in January 2020, 6 weeks before election day.

Data analysis

We used RStudio desktop version 1.3.959 to conduct analyses (RStudio Team, Citation2020). All continuous variables were assessed to determine whether they met the assumption of normality. Change in policy opinions was non-normally distributed, with skewness of 1.68 and kurtosis of 5.37. This distribution is expected given that most voters did not change their policy opinions. Linear regression is still a sound technique given our large sample size. None of the variables showed high collinearity, as assessed through bivariate correlations for continuous variables (ranged from −.03 to .20) and variance inflation factors for categorical variables (ranged from 1.04 to 3.19).

We began our analysis by using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to predict baseline policy opinion toward the decarceration policy. Next, we used a within-subjects Ordinarily Least Squares (OLS) regression design to test our hypothesis that story-sharing, emotional expression, and their interaction explain increased support for Measure R, after accounting for other factors. In the first model, change in policy opinion was regressed over story-sharing––the primary factor theorized to account for attitude change in prior literature. In the second model, policy opinion change was additionally regressed over emotional expression. In the third model, we controlled for baseline opinion; this is an important control since those who begin more supportive of the policy have less room to move than those who begin opposed. In the fourth model, we added voter age, race, gender, and partisan affiliation and additional controls for canvasser experience and time-point in the campaign. In the fifth, full model, change in policy opinion was regressed over all the previous variables and our hypothesized interaction variable between story-sharing and emotional expression. Finally, we conducted a logistic regression of the full model over a binary outcome variable demonstrating categorical change in support for the decarceration policy. The case-to-independent variable ratio for this analysis was 181 to 1 which exceeds minimum requirements for regression analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2005).

Results

Baseline policy opinion

First, OLS regression was used to predict baseline policy opinion of Measure R (see, ). The following were associated with a lower baseline score: being a man as compared to a woman (B = −0.33, p < .001), being Latinx as compared to being White (B = −0.52, p = .002). A higher baseline score was associated with being Black as compared to being White (B = 1.03, p < .001) and being a Democrat compared to other main political party affiliations. Greater time into the campaign was also associated with a lower baseline policy score (B = −0.03, p = .001), which was likely a reflection of greater political information being accessible to voters as election day approached.

Table 2. Baseline policy opinion regression results

Changes in policy opinion

displays the results from models with change in policy opinion as a continuous dependent variable. In support of our hypothesis, emotional expression significantly predicted increased support for Measure R, after accounting for other variables. Specifically, expressing emotions during a deep canvass conversation was associated with a 0.66-point increase in policy support (p < .001). Sharing a personal story, after accounting for emotional expression and baseline policy attitudes, was significantly related to policy change (B = −0.194, p = .042). Having a higher baseline policy opinion was associated with less change in policy opinion (B = −0.272, p < .001). Compared to Democrats, being a Republican or Independent was associated with decreased support for the policy (B = −0.472, p < .001 and B = −0.211, p < .01, respectively).

Table 3. Change in policy opinion regression results

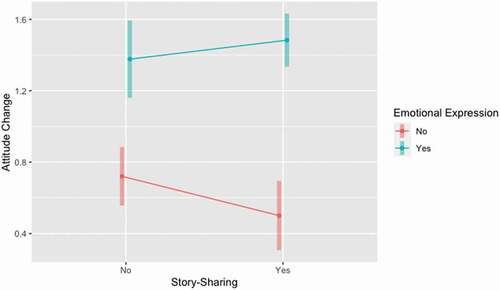

A significant interaction between story-sharing and emotional expression (B = 0.309, p = .024) predicted change in policy opinion. Further probing of the interaction showed that story-sharing paired with emotional expression related to more positive change in the policy opinion than story-sharing without emotional expression (B = 0.983, p < .001). There was a significant difference between conversations that included only story-sharing and those that included neither story-sharing nor emotional expression (B = −0.220, p = .019), with story-sharing devoid of emotional expression being associated with less change. Likewise, for voters who expressed emotion during the conversation, story-sharing had no additional effect on policy attitude change (B = 0.106, p = .285), which aligns with the strong main effect of emotional expression. graphs the effect of story-sharing on attitude change, as moderated by emotional expression. This interaction supports our hypothesis that story-sharing only predicts attitude change in the expected direction if it is combined with emotional expression.

Figure 1. Interaction effect of story-sharing and emotional expression on attitude change. Emotional expression moderates the effect of story-sharing on attitude change, with the combination of story-telling and emotional expression having a significantly larger effect than story-telling alone.

The results of the logistic models with change in policy opinion as a binary dependent variable are presented in ; these results predicted increased support from one category of policy opinion to another. Overall, 22% of the sample moved up in their categorical support for the policy. As hypothesized, emotional expression significantly predicted increased support for Measure R, after accounting for other variables. Expressing emotions during a deep canvass conversation increased the odds of substantively increasing support for the decarceration policy by a factor of 2.207 (p < .001). Sharing a personal story, when accounting for emotional expression and other factors, was not significantly related to policy change (p = .093). A one-point increase in baseline policy opinion decreased the odds of substantively increasing support for the policy by a factor of 0.731 (p < .001). Being a man (compared to being a woman) decreased the odds of substantively increasing support for the policy by a factor of 0.784 (p = .021). Being a Republican or Independent (compared to being a Democrat) decreased the odds of substantively increasing support for the policy by a factor of 0.517 (p < .001) and 0.603 (p < .001), respectively.

Table 4. Substantive changes in policy opinion logistic regression results

The interaction between story-sharing and emotional expression predicted substantive change in support for the decarceration policy, after accounting for other factors. Specifically, someone who shared a story and expressed emotions, compared to someone who did not, was 4.113 times more likely to substantively increase their support for Measure R (p < .05). This interaction pattern was similar to what was found for the continuous dependent variable (see, ). Further probing of the interaction showed that story-sharing paired with emotional expression related to more positive change in the policy opinion than story-sharing without emotional expression (B = 1.437, p < .001). There was no significant difference between conversations that included only story-sharing and those that included neither story-sharing nor emotional expression (B = −0.343, p = .093). Likewise, for voters who expressed emotion during the conversation, story-sharing had no additional effect on policy attitude change (B = 0.302, p = .075), which aligns with the strong main effect of emotional expression. This interaction again supports our hypothesis that story-sharing only predicts attitude change if it is combined with emotional expression.

Discussion

These results provide evidence that during a deep canvasing conversation, voters’ expression of emotions, alone and in concert with sharing a personal narrative, was related to increased support for the decarceration policy. This pattern of findings was consistent across continuous and categorical measures of policy change, pointing to the robustness of effects and suggesting that emotional expression during deep canvasing may prompt gradual upward movement in decarceration policy support as well as larger qualitative shifts away from opposition or ambivalent/undecided categories. Having a higher baseline policy opinion predicted less attitude change, though this is likely reflective of ceiling effects; those who began supportive of the policy had a smaller range for change possible. While there were no significant gender differences in policy opinion change using the continuous outcome measure, the logistic regression results predicted that men were less likely to categorically increase their support for the decarceration policy than women––which may relate to gender norms about sharing personal stories or expressing emotions. Identifying as Republican or Independent, relative to Democrats, predicted less increase in support for the decarceration policy, highlighting a factor that may make voters less persuadable or more resistant to change. While the intervention still had an effect on non-Democrats, a different deep canvass script could be more impactful for these voters than the one examined in this study. Other demographic factors, while predictive of answering the door, engaging with a canvasser, or completing a full conversation, did not predict change itself. This study contributes to the literature on political interventions, and specifically deep canvasing, by demonstrating the important role played by emotional expression in attitude change.

Emotional expression

Our study demonstrates the importance of emotional expression in predicting decarceration policy attitude change, adding to a literature on deep canvasing that has largely emphasized story-sharing as a primary mechanism for attitude change (Broockman & Kalla, Citation2016; Kalla & Broockman, Citation2020, Citationin press). The fact that we found strong associations with policy change using a single-item dichotomous, canvasser-reported measure of emotional expression speaks to the potential power of emotions in deep canvasing and the need to further study this factor in real-world canvasing contexts with more robust measures. Emotions have been widely acknowledged as central to attitude change in social psychological experimental studies (Van Kleef et al., Citation2015), clinical therapy settings (Greenberg & Angus, Citation2004), and in research on political persuasion (Albertson et al., Citation2020). Some theorists have argued that emotions are a primary impetus for changing attitudes (Zajonc, Citation2000), and many explanations have been proposed regarding how emotional expressions lead to attitude change, such as elongating or changing cognitive information processing, making individuals more open to counter-arguments, or motivating individuals to reduce dissonance between competing attitudes (Forgas, Citation2008). In deep canvass organizing, more research is needed that pinpoints which emotions are being expressed and how different emotions may differentially relate to attitude change (Albertson et al., Citation2020). Qualitative examination of deep canvasing conversations may be a particularly fruitful avenue for exploring these dynamic processes. Additionally, it would be both theoretically and practically important to pinpoint which aspects of deep canvasing conversations function to elicit emotions. Our findings offer some reason to believe that personal story-sharing may be a vehicle for emotional expression.

Personal stories and emotional expression

In these data, voters’ personal story-sharing, also termed analogic perspective-taking, only predicted increased support for decarceration policy when emotions were shared. Kalla and Broockman (Citationin press) concluded that perspective-getting (i.e., hearing a canvasser’s story) was a key driver of deep canvasing’s effects on attitude change, and analogic perspective-taking may play a more minor role. Our work underscores that analogic perspective-taking should not be ruled out as an important component of deep canvasing if the canvasing conversations can create the right conditions for eliciting voters’ emotional expression. The implication for theoriesy of attitude change as well as for the practice of deep canvasing is that story-sharing and emotional expression may function synergistically to build policy support. This finding aligns with narrative theory and research, which finds that stories with more emotional content are more likely to produce attitude change (Appel & Richter, Citation2010), and that emotions can help to further transport individuals into narratives, enhancing the likelihood of attitude change (Green & Brock, Citation2002). An alternative process that can neither be directly tested nor ruled out by our cross-sectional data is that personal story-sharing may facilitate voters’ emotional expression, which in turn leads to changes in attitudes. This mediational hypothesis is somewhat compatible with our pattern of findings, in that personal story-sharing was related at a bivariate level to attitude change, but the direction of the association was reversed when emotional expression and other factors were added to the models and the association was reduced to non-significance in the logistic regression model. Longitudinal data would be essential for properly testing the mediation pathway, and experimental designs that manipulate story-sharing and observe differences in emotional expression and subsequent attitude change would be particularly meaningful for demonstrating evidence for this hypothesis.

Limitations

Our findings must be viewed in the context of the study’s methodological limitations. Although this real-world canvasing data provided important insights into the role of emotional expression and story-sharing in shifting decarceration policy attitudes, the cross-sectional design precludes any causal inference. Randomized experimental designs of deep canvasing could rule out selection effects such as empathic predispositions or social desirability bias, which in our study may have been unmeasured explanations for emotional responses and reported attitude change. We assume that voters’ emotional expression preceded their policy change in the conversation at the door, yet policy change could have shaped canvassers’ memory or perceptions of emotional expression. Further, future research should continue examining the durability of attitude change and whether narrative sharing and emotional expression prompt changes in broader attitudes, other specific policy opinions, and ultimately in vote choice.

Implications and conclusion

These findings may enhance community practice aimed at building support for abolitionist policies. Policy attitudes pertaining to decarceration may be especially resistant to change given the strength of dominant ideological support for carceral institutions. This deep canvasing initiative was notable in demonstrating change in policy attitudes among adults in primarily White neighborhoods, a population that is more likely to uphold attitudes in favor of incarceration. Additionally, the ballot initiative, Measure R, was passed by Los Angeles County voters. Although we cannot say with these data whether the large-scale canvasing initiative contributed to policy change, our work joins others in demonstrating the viability of scaling up micro-level political interventions for changing policy opinions on social issues that are typically fraught with ideological divides (Krings et al., Citation2019). Targeting ideological change through deep canvasing may be an effective way to change dominant carceral logics and weaken structural racism.

More broadly, this approach has significant implications for social work community practice, demonstrating the value of merging micro-level therapeutic change with macro-level organizing to influence policy change (Santiago et al., Citation2017). This concrete intervention tool can be taught to individuals and scaled up to be used by large teams of activist-organizers to build support for a wide range of equitable social policies. Organizing through the shared exchange of narratives and emotions is akin to mobilizing squads of political therapists, which may be a viable route to meaningful change in dominant attitudes.

Acknowledegements

The authors would like to thank Showing Up for Racial Justice, AWARE-LA/White People for Black Lives, and the Measure R Campaign – the organizers who have led the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Center for Open Science (OSF) at DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/7W3PG.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albertson, B., Dun, L., & Kushner Gadarian, S. (2020). The emotional aspects of political persuasion. In E. Suhay, B. Grofman, and A. H. Trechsel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of electoral persuasion (pp. 169–183). Oxford University Press.

- American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare. (2021). Progress and plans for the Grand Challenges. University of Maryland, School of Social Work. https://view.pagetiger.com/grand-challenges-impact-report-2021/1

- Appel, M., & Richter, T. (2010). Transportation and need for affect in narrative persuasion: A mediated moderation model. Media Psychology, 13(2), 101–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15213261003799847

- Broockman, D., & Kalla, J. (2016). Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science, 352(6282), 220–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9713

- California Secretary of State. (2020). February 18, 2020—Report of registration—registration by county (p. 8). https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ror/15day-presprim-2020/county.pdf

- Cosgrove, J., & Thekmedyian, A. (2020, August 4). L.A. County to vote on diverting millions to social services—Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-08-04/l-a-county-will-vote-on-whether-to-reimagine-government-spending

- Critical Resistance. (2020). Reformist reforms vs. Abolitionist steps in policing. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59ead8f9692ebee25b72f17f/t/5b65cd58758d46d34254f22c/1533398363539/CR_NoCops_reform_vs_abolition_CRside.pdf

- Davis, A. Y. (2005). Abolition democracy: Beyond empire, prisons, and torture (1st ed.). Seven Stories Press.

- de Graaf, A., Hoeken, H., Sanders, J., & Beentjes, H. (2009). The role of dimensions of narrative engagement in narrative persuasion. Communications, 34(4), 385–405. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2009.024

- Dolan, M. (2020, June 12). London breed pushes San Francisco reforms: Police no longer will respond to noncriminal calls. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-06-12/san-francisco-police-reforms-stop-response-noncriminal-calls

- Forgas, J. P. (2008). Affect and cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 94–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00067.x

- Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

- Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2002). In the mind’s eye: Transportation-imagery model of narrative persuasion. In M. C. Green, J. J. Strange, & T. C. Brock (Eds.), Narrative Impact (pp. 315–341). Erlbaum.

- Green, M. C. (2008). Research challenges: Research challenges in narrative persuasion. Information Design Journal, 16(1), 47–52. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/idj.16.1.07gre

- Greenberg, L. S., & Angus, L. E. (2004). The contributions of emotion processes to narrative change in psychotherapy: A dialectical constructivist approach. In L. Angus & J. McLeod (Eds.), The handbook of narrative and psychotherapy (pp. 330–349). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412973496.d25

- Haney-López, I. (2019). Merge left: Fusing race and class, winning elections, and saving America. The New Press.

- Heath, C., Bell, C., & Sternberg, E. (2001). Emotional selection in memes: The case of urban legends. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1028

- Kalla, J., & Broockman, D. (2020). Reducing exclusionary attitudes through interpersonal conversation: Evidence from three field experiments. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 410–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000923

- Kalla, J., & Broockman, D. (in press). Which narrative strategies durably reduce prejudice? Evidence from field and survey experiments supporting the efficacy of perspective-getting. American Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12657

- King, D. S., & Smith, R. M. (2016). THE LAST STAND? Shelby county v. Holder, White political power, and america’s racial policy alliances. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 13(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X1500017X

- Krings, A., Fusaro, V., Nicoll, K. L., & Lee, N. Y. (2019). Social work, politics, and social policy education: Applying a multidimensional framework of Power. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1544519

- Krogstad, J. M. (2015). Reflecting a racial shift, 78 counties turned majority-minority since 2000. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/08/reflecting-a-racial-shift-78-counties-turned-majority-minority-since-2000/

- Lipsitz, G. (2006). The possessive investment in whiteness: How White people profit from identity politics (Rev. and expanded ed.). Temple University Press.

- McDonald, M. P. (2020). Voter turnout demographics—United States elections project. http://www.electproject.org/home/voter-turnout/demographics

- McKenna, E., & Han, H. (2014). Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 million volunteers transformed campaigning in America. Oxford University Press.

- NGP VAN, Inc. (2021, May 4). SmartVAN California. SmartVan California. [https://www.targetsmartvan.com]. https://www.targetsmartvan.com/CreateAList.aspx

- Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States (3rd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Pew Research Center. (2020). Majority of public favors giving civilians the power to sue police officers for misconduct. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/07/09/majority-of-public-favors-giving-civilians-the-power-to-sue-police-officers-for-misconduct/

- Public Policy Institute of California. (2020). California’s likely voters. https://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-likely-voters/

- Rakich, N. (2020, June 19). How Americans feel about ‘Defunding The Police.’ FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/americans-like-the-ideas-behind-defunding-the-police-more-than-the-slogan-itself/

- RStudio Team. (2020). RStudio: Integrated development for R. RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/

- Santiago, A. M., Soska, T. M., & Gutierrez, L. M. (2017). Improving the effectiveness of community-based interventions: Recent lessons from community practice. Journal of Community Practice, 25(2), 139–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2017.1334436

- Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2006). Entertainment—Education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2005). Using multivariate statistics (4. ed., [Nachdr.]). Allyn and Bacon.

- Taylor, K.-Y. (2016). From #BlackLivesMatter to Black liberation. Haymarket Books.

- The Associated Press. (2020, June 7). Video: Minneapolis City Council Pledges to Disband Police Dept. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/video/us/politics/100000007179116/minneapolis-city-council-police.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). 2019: American community survey one-year estimates subject tables public use microdata samples. SAS Data file. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=0100000US.050000_0500000US06037&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S0101&hidePreview=false

- Van Kleef, G. A., van den Berg, H., & Heerdink, M. W. (2015). The persuasive power of emotions: Effects of emotional expressions on attitude formation and change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1124–1142. Link to external site, this link will open in a new window. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000003

- von Hippel, P. T., & Bartlett, J. (2019). Maximum likelihood multiple imputation: Faster imputations and consistent standard errors without posterior draws. ArXiv:1210.0870 [Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.0870.

- Zajonc, R. B. (2000). Feeling and thinking: Closing the debate over the independence of affect. In Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition (pp. 31–58). Cambridge University Press.