ABSTRACT

Medical mistrust among the public was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic due to racial and social inequities in infection rates and misinformation in the media. In Boston, two initiatives were launched by the Boston University Clinical Translational Science Institute (BU CTSI), Boston Medical Center (BMC), community health centers (CHCs), and community organizations to establish longitudinal and authentic partnerships with community-research boundary spanners who remained trusted sources of information. Each initiative addressed the immediate need for community-informed and partnered COVID research and provided a structure for longitudinal partnerships. In this paper, we describe the process of envisioning how these two initiatives could move from isolation toward collective impact. We also identify opportunities to improve community-engaged research practices within an academic health system. Our approach provides a structure that other organizations can use to align initiatives and move toward boundary-crossing partnerships which foster health equity.

Introduction

In 2020, two parallel stories led to a public reckoning with racism in the U.S. –George Floyd’s murder by police officers and the gross racial and social inequities in COVID-19 infection rates (Walsh, Citation2022). These situations, combined with the rapidly changing and sometimes contradictory COVID-19 information in the media, amplified medical mistrust among the public, in particular among populations who had experienced racism and mistreatment in healthcare (Eder et al., Citation2021). Academic safety net health systems that predominately served communities of color were invited to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trials to ensure racial and ethnic diversity in research participants. The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) supported recruitment for trials through community engagement programs at more than 60 academic medical centers across the country (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [NCATS], Citation2022). Community engagement can be an effective approach to advance equity in research because it centers priorities on community needs, enables trust, and builds partnerships (Brunton et al., Citation2017; Ohmer et al., Citation2022; Wallerstein & Duran, Citation2006).

Boston Medical Center (BMC), a major partner of the NCATS funded BU CTSI, is the largest safety net hospital in New England. BMC’s patient population is majority people of color, low-income, and nearly one-third speak a language other than English (Walsh, Citation2022). At the height of the pandemic, Black residents in Boston were 1.6 times more likely than White residents to die from COVID-19 and infections rates for Latinx residents were more than two-times higher than non-Latinx-White residents (Walsh, Citation2022). Despite the diversity of BMC’s patient population, recruitment of equally diverse research participants for COVID-19 studies remained a challenge. For this reason, BMC created a Clinical Research Network (CRN) to facilitate rapid activation and management of hospital-based studies, while promoting community-engaged research values.

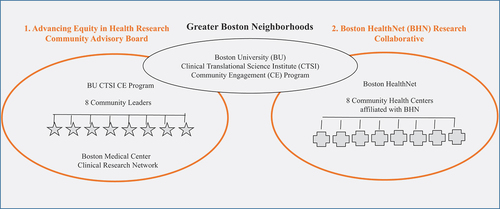

At the same time, Boston HealthNet (BHN), a BMC system that integrates CHCs with the hospitals’ leading specialists and cutting-edge technology, became inundated with requests from researchers to partner on COVID-19 studies. Amid a turbulent climate of medical mistrust, the BU CTSI, CRN, BHN, local CHCs and community organizations established two distinct initiatives: the Advancing Equity in Health Research Community Advisory Board (CAB) and the Boston HealthNet Research Collaborative (Collaborative). These initiatives were created to partner with community-research boundary spanners to address the immediate need for community-informed and partnered COVID research, and to provide a structure for longitudinal research partnerships (Ojikutu et al., Citation2021).

Community-research boundary spanners

Community-research boundary spanners are located in, representative of, and serve minoritized communities who are disproportionately impacted by racialized social policies that contribute to inequitable living conditions and produce ill health (Walsh, Citation2022). They understand local dynamics, resources, and needs which informs the development of research that is useful to the communities they serve. While the vision and justification for community-engaged research has been well articulated, the practice of nurturing longitudinal meaningful partnerships in health services research lags behind (Israel et al., Citation2006; Marrero et al., Citation2013). Isolated initiatives to increase community-researcher partnerships are unlikely to change research norms in the academic system (Israel et al., Citation2006; Kania et al., Citation2021; Marrero et al., Citation2013; Sprague Martinez et al., Citation2023). A coordinated, collective approach with multiple initiatives is more likely to amplify a message, change behavior, and bring about systems change (Christens & Inzeo, Citation2015; Kania et al., Citation2021). This paper describes the process of analyzing two initiatives to envision how they could move from isolated impact toward collective impact to change the approach to community-researcher partnerships at an academic medical center.

Collective impact

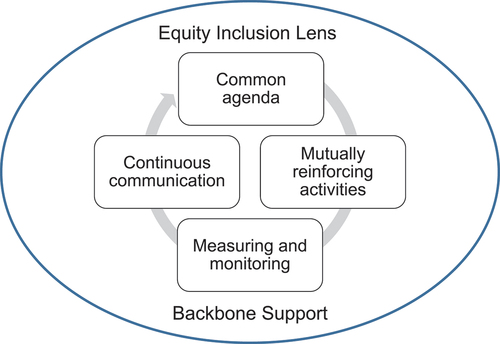

Collective impact has been defined as “the commitment of a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem” (Christens & Inzeo, Citation2015). Six key conditions have been identified as essential to collective impact, as illustrated in (Christens & Inzeo, Citation2015).

These six conditions include a common agenda, which involves creating a shared vision for change among multi-sector organizations, initiatives, and actors. These actors conduct mutually reinforcing activities that strategically link to achieve a shared vision. Backbone support typically is provided by a single organization to coordinate, facilitate, and support the collaboration process. Continuous communication among the actors builds relationships, trust, alignment, and a collective identity. Measurement and monitoring of activities is performed to continually assess progress, encourage learning, accountability, and adaptation. The final notion of centering equity is relatively new to the Collective Impact Framework and involves centering each of the other conditions on equity, to understand who has been marginalized, why, how they are experiencing the marginalization, and potential approaches that can be used to address the issue (Kania et al., Citation2021). Moreover, centering equity necessitates creating new policies, procedures, and opportunities that address the inequities and liberate the actors from the structures that prevent them from successfully collaborating on research (Kania et al., Citation2021).

The actors in the initiatives

The CAB and Collaborative are connected by the BU CTSI, which serves as a boundary spanner (). The actors in each initiative draw upon their personal experience with social, economic, and/or racial injustice and the work they do to provide mutual aid and resources in Greater Boston neighborhoods.

Actors in the CAB

The main actors in the CAB are the BU CTSI’s Community Engagement (CE) Program, BMC’s CRN, and eight community leaders from organizations that are in and serve communities in greater Boston. The BU CTSI offers a range of tools, training, services, and resources, including funding to support community-researcher partnerships, which maximize the impact of discoveries and speed the translation of research into improved health. The CRN brings technical expertise in research compliance and finance to the CAB. Community leaders bring experience and technical expertise in outreach and education gained through their professional roles in organizations that focus on local issues (e.g., youth empowerment, health advocacy, food justice, professional networks for people of color, adult education, access to resources for immigrant populations, and safe housing through emergency shelters). The community leaders were identified by the BU CTSI CE Program and the CRN as successful boundary spanners between people of color and health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their role is to provide research consultations to improve equity in specific studies and to use the lessons learned from the consultations to recommend improvements to research processes at BU and BMC.

Actors in the collaborative

The main actors in the Collaborative are the BU CTSI CE Program, the BHN, and 8 of 11 CHCs affiliated with the BHN. All 11 CHCs were invited to participate in the Collaborative. The eight CHCs who joined were inundated with requests from researchers to partner on COVID-19 studies. They wanted to prioritize research but lacked the bandwidth and infrastructure to participate. Furthermore, requests from researchers often did not align with the priorities of the CHC, or researchers approached them too late in the process to meaningfully collaborate. Actors in the Collaborative discussed these issues and decided to identify a specific person at each CHC to manage communications with researchers, a Research Liaison, who was appointed by the CHC’s CEO. The Research Liaisons represent a range of CHC roles (e.g., Program Manager, Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care Physician, Performance Improvement specialist, etc.) and have a range of experience in research. The eight CHCs initially joined the Collaborative in the spring of 2022 and remain active in the Collaborative.

Applying the collective impact framework

The coauthors involved in the CAB and Collaborative who represent community leaders (LPL, KK), Research Liaisons from CHCs (CB, AA), the BU CTSI CE Program (TB, RL, JP), CRN (RS), and BHN (AR) applied the Collective Impact Framework to the initiatives using an iterative, collaborative process. Coauthors shared ideas using e-mail correspondence, tracking and comments in MS Word, and discussion during meetings. The coauthors provide a description of the CAB and Collaborative within the context of each essential condition for collective impact to identify opportunities to move beyond isolated efforts.

Common agenda

Discrete common agendas for each initiative were articulated in Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) for the CAB and Collaborative early in the initiatives. The coauthors compared and contrasted priorities in the two MOUs to assess the similarities and differences. The common themes across the MOUs were to emphasize research based on community priorities; create opportunities for community-research communication; build trust between community members and researchers at BU and BMC; center research on equity; and build capacity for community participation in research (). This process provided us with a clear, shared vision across the CAB and Collaborative, and activities of each initiative mutually reinforce the shared values.

Table 1. Common agenda articulated through Memorandum’s of understandings (MOUs).

Mutually reinforcing activities

Researcher-CAB consultations

The primary goal of the researcher-CAB consultation is to center research on equity. The CAB consultations follow the Studio model that has been used successfully to provide input from community to enhance research design, implementation, and dissemination (Emmons et al., Citation2022; Joosten et al., Citation2015). Researchers request consultations with the CAB through the CRN or the BU CTSI CE Program. The researcher-CAB consultations involve the researcher preparing a 10-minute video to describe their research project (intent, methods, community engagement strategies, etc.) and questions they have for the CAB related to community-engaged practices. Community leaders review the video and provide written feedback to the researcher via a survey. The BU CTSI CE Program compiles the survey responses and sends them to the researcher in advance of a 45-minute Zoom-meeting consultation so that researchers can process the information in preparation for their interaction with community leaders. The Zoom meeting is facilitated by the community leaders and is structured to support bi-directional, candid conversations on thoughts or recommendations that did not make it into the written feedback.

Researcher-CHC consultations

The primary goal of the researcher-CHC consultation is to identify opportunities to partner on research that focuses on the priorities of the CHC and the populations it serves. The consultations arise when a researcher applies to partner with a CHC through a Web-based portal that was conceived of by the CHCs and developed by the BU CTSI CE Program. This portal organizes and track researchers’ requests to partner. To encourage applications that align with each CHC’s priorities, the Web-based portal provides a bio for each CHC which includes information on the primary populations they work with, the unique health issues they address and current challenges they face. This can include health impacts of homelessness, systems of care that promote social and racial health equity, treatment cost analyses, vaccine trials, educational opportunities, complex care management, and others. Research Liaisons then facilitate review of these applications, using processes that are unique to each CHC. If the CHC agrees to partner, the Research Liaison will recruit clinician champions for the project, develop community or patient advisory panels, or provide other services, depending on the needs of the study.

The equity rubric

The CAB developed a rubric to support centering equity in research during the consultation process. A workgroup comprised of three CAB members convened regularly to lead the design of the rubric. They engaged other CAB members in discussions about prototypes at monthly meetings with all CAB members. The process of developing the rubric strengthened ties among CAB members, reinforced collective identity, and further increased their understanding of the diversity in perspectives represented in the CAB. The rubric summarizes best practices for increasing equity in health research based on the literature (Emmons et al., Citation2022; Peterson et al., Citation2021), lived experiences of community leaders, and feedback from researcher end-users. It is composed of four pillars of equity: community centeredness, communication methods, institutional barriers, and intersecting factors (). Under the description of each pillar is a key set of questions and recommendations that guide researchers to incorporate diversity, equity, and inclusion principles into research plans and prioritize the needs and experiences of local stakeholders at every stage of the research design process (planning, recruitment, participation, dissemination).

Partnering on research

Partnering on research is a primary goal of the CHCs in the Collaborative. Historically, BHN CHCs did not have a research point person at each site, and they were approached to partner on research without time for them to collaborate. This minimized the CHC’s power to successfully negotiate on the design, approach, or budget of a project. Through the Collaborative, the CHCs created systems to improve their experience with partnering on research. They developed guiding principles and rules of engagement to be fully transparent with researchers about the topics and processes that would influence their decision to partner with them. Each rule of engagement is broken down by role, denoting specific expectations of the CHC and the researcher. For example, a guiding principle is “research is aligned with the health center priorities.” The rules of engagement related to the principle are “to be aware of CHC priorities identified in the bios” and “address local relevance in the Web portal application” for the researchers; and “review and update bio annually” for the CHC.

When the CHC decides to collaborate, the Research Liaison works directly with the researchers, over time, to design and implement a research approach that reflects the communities’ priorities, actively promotes health equity through inclusion of specific linguistic and cultural considerations and supports the operational needs of their specific CHC. The Research Liaison position has increased capacity for the CHCs to both participate in research and have a voice in shaping policies to better serve their organization and patients. Since the Collaborative was initiated, some CHCs have taken steps to involve Research Liaisons with forming research departments to further build capacity for research at their organization.

Building capacity for community leadership in research

Building capacity to support community leadership in research is a shared vision of the CAB and Collaborative. Actors in both initiatives are contributing ideas for the BU CTSI’s NCATS renewal proposal. They are also identifying opportunities to leverage the success with the CAB and Collaborative to expand meaningful collaborations with community organizations and safety-net health systems throughout Greater Boston, fills gaps in representation of other underserved identities (e.g., LGBTQ+, people with disabilities) and build capacity for community-academic research partnerships.

Backbone support

The collective impact condition of backbone support is typically provided by a single organization. For the CAB and the Collaborative, the BU CTSI CE Program primarily supports data collection and funds honoraria for members of the CAB. However, other forms of backbone support such as coordination, facilitation, and funding for the Collaborative are shared among the various actors.

Continuous communication

Monthly meetings

Both the CAB and the Research Liaisons hold monthly meetings which contribute to building relationships, trust, and a collective identity within their respective initiatives. The agenda for monthly CAB meetings supports communication on work performed since the last meeting, discussion and decision-making on topics prioritized by community leaders, and planning for future meetings. The CAB uses 4–6 of their monthly meetings each year for strategic planning purposes. Breakout groups are often used in CAB meetings to build relationships and support building consensus for decision-making. The agenda for the monthly Research Liaison meetings primarily focuses on data from applications that were submitted through the Web portal and learning about opportunities to build research capacity at the CHCs.

Workgroups

The CAB uses ad hoc workgroups to advance ideas into action in between monthly CAB meetings. Competing clinical demands has limited participation in workgroups to support moving ideas into action for the Collaborative.

Extra-curricular activities

Communication among actors in the CAB is further supported by participating in activities hosted by other actors (e.g. outreach to housing insecure individuals, community education forums, fundraising to support recently arrived immigrants during the holidays, etc.). Although these activities are outside the normal course of a CAB members’ role, participation facilitates making new connections, supports relationship building, and deepens trust. Additionally, CAB members gather once a year for an informal lunch or dinner to catch-up on each other’s activities outside of the CAB.

Retreats

At least two times a year, the CEOs, CMOs, and Research Liaisons from the Collaborative, and the BU CTSI CE Program gather for a strategic planning retreat to discuss applications that have been received by the Collaborative. Small group discussions are often used to support cross CHC communication among the CEOs and CMOs.

Measurement and monitoring

Measuring and monitoring for the CAB and the Collaborative is used to inform learning, not to render a definitive judgment of success or failure. For the CAB, the process of measuring and monitoring is built into the format for the monthly and workgroup meetings. In the future, this will also include a follow-up survey with researchers after a consultation. The minutes from monthly and workgroup meetings provide documentation to clarify decisions, identify issues that arise, document action items, and retain information on topics for future discussion. For research consultations, the meeting minutes reflect the key recommendations from CAB members.

For the Collaborative, measuring and monitoring is based on data collected from applications submitted through the Web-portal and from discussions with the CEOs, CMOs, and Research Liaisons from CHCs during retreats. The BU CTSI CE Program monitors the number of applications, partnership decisions, and study topics on an ongoing basis. The BHN compiles this information in a report that is shared in meetings with CEOs and CMOs at least two times a year at the strategic planning retreats and reported to Research Liaisons at the monthly forums.

Centering equity

The structures of the CAB and Collaborative were designed to have the perspectives of the community leaders and CHCs dictate the goals and activities of each initiative. We were thoughtful to avoid oppressive language, yet neither the CAB nor the Collaborative have deliberatively reflected on power dynamics. Through collaboration on this manuscript, we realized it is important to reflect upon the identities, relational practices and structural factors that are present in the initiatives, in order to minimize harm (Wallerstein et al., Citation2020). For example, power imbalances in the Collaborative may stem from organizational hierarchies. While the opinion of the Research Liaison is valued and they are the primary contact for researchers, they are not the final decision makers on whether the CHC partners on a specific project. That level of decision making typically rests with the CEO. Yet, the Research Liaison has power to influence research methods and implementation strategies at the CHC. They also make recommendations on a study’s alignment with CHC priorities and feasibility.

The CAB is also vulnerable to power imbalances that arise from traditional hierarchies in academic settings that place more value on the knowledge and experience of researchers than community leaders (Fletcher et al., Citation2021; Okun & Jones, Citation2001; Wallerstein et al., Citation2020). The equity rubric contributes to balancing power in the research consultation by setting clear expectations of the expertise that community leaders bring to a consultation. Furthermore, the structure of the researcher review process is power equalizing because the community leaders receive the researcher’s questions and presentation in advance of the Zoom meeting to give them time to ask questions, seek additional information on topics, and formulate thoughtful guidance for the researcher. Other examples of how we attempt to remove oppressive influences from the CAB and Collaborative include using joint agenda setting practices and providing compensation for all partners.

Opportunities to move toward collective impact

Throughout this process, we identified four opportunities that we can act on now to leverage successful practices in both initiatives and amplify their shared vision to bring about systems change.

Integrate the equity rubric into research liaison consultations

While equity in research is a priority of the Collaborative, Research Liaisons did not follow a structured approach in applying an equity lens. The equity rubric, developed by community leaders in the CAB, has the potential to focus every researcher-CHC consultation on actions that researchers can take to incorporate diversity, equity and inclusion principles into research plans and prioritize the needs and experience of local stakeholders. The CAB members would also benefit from a scaling-up use of the rubric because they would learn if the tool is generalizable to other research settings.

Initiate opportunities for continuous communication across the CAB and collaborative

The process of applying the Collective Impact conditions to the CAB and Collaborative highlighted the benefit of communication across the initiatives. A workgroup with cross initiative representation, community leaders from the CAB and Research Liaisons from the Collaborative, has the potential to identify other opportunities to move toward collective impact and support ongoing communication between the CAB and Collaborative (e.g., forums, retreats, etc).

Continue to identify, minimize, and address power imbalances

The CAB and Collaborative were created to liberate community leaders from the oppressive power of research hierarchies to become true partners in research. Progress has been made toward this goal, although power dynamics among the actors in the initiatives were never formally discussed. Collective impact requires that a more deliberative approach is used by embedding discussions about power in standing meetings for the CAB and Collaborative. Centering equity requires identifying where power sits in these relationships, encouraging reflexive practices to minimize harm, and intentionally addressing power imbalances among actors (Fletcher et al., Citation2021; Wallerstein et al., Citation2020).

Develop an approach to measure collective impact

Collective impact evaluation is intended to support learning that informs shifts in strategy (Cabaj, Citation2014). This approach to evaluation is already built into the CAB and Collaborative as both initiatives were designed to establish longitudinal communication structures to support authentic partnerships with community-research boundary spanners. To meet the measuring and monitoring condition of collective impact, we will need to develop an approach that measures and evaluates both initiatives and the ways they interact and evolve over time (Parkhurst & Preskill, Citation2014). This includes continuously monitoring the context, the quality and effectiveness of the structure and operations for collective impact, and the ways that mutually reinforcing activities influence research systems at BMC and BU toward a common goal (Parkhurst & Preskill, Citation2014).

Conclusion

The process of analyzing the six essential conditions for collect impact across two initiatives was useful to identify ways that working together may be more impactful. Our approach provides a structure that can be used in other settings to identify opportunities to leverage lessons learned for one initiative to support another. A coordinated, collective approach with multiple initiatives is more likely to amplify a message, change behavior, and bring about change in academic medical systems.

Acknowledgments

Co-authors represent partners from multiple sectors involved with the two initiatives discussed in this paper (CAB and Collaborative). There are numerous other partners in the initiatives, who did not participate as co-authors, but have been critical to the success of the initiatives including: Brandon Tilghman, Leah Gregory, Chloe Miller, Dorosella Green, Dieufort Fleurissant, Emily Hall, Stephen Tringale, Ivy Opoku-Mensah, Elizabeth Wolff, Bill Adams, Charlie Williams, Erika Christenson. The CAB would like to dedicate this manuscript in honor of David Tavares, Executive Director of Families in Transition at the Boston YMCA, who unexpectedly passed away in July 2023. David was a trusted colleague, devoted mentor, and exceptional friend who was a member of the CAB since it’s inception.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brunton, G., Thomas, J., O’Mara-Eves, A., Jamal, F., Oliver, S., & Kavanagh, J. (2017). Narratives of community engagement: A systematic review-derived conceptual framework for public health interventions. BMC Public Health, 17(1). Article 944. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4958-4.

- Cabaj, M. (2014). Evaluating collective impact: Five simple rules. The Philanthropist Journal, 26(1), 109–124. https://thephilanthropist.ca/2014/07/evaluating-collective-impact-five-simple-rules/

- Christens, B. D., & Inzeo, P. T. (2015). Widening the view: Situating collective impact among frameworks for community-led change. Community Development, 46(4), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2015.1061680

- Eder, M. M., The PACER Group, Millay, T. A., & Cottler, L. B. (2021). A compendium of community engagement responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1), Article e133. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.800

- Emmons, K. M., Curry, M., Lee, R. M., Pless, A., Ramanadhan, S., & Trujillo, C. (2022). Enabling community input to improve equity in and access to translational research: The community Coalition for equity in research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 6(1). Article E60. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.396.

- Fletcher, F. E., Jiang, W., & Best, A. L. (2021). Antiracist praxis in public health: A call for ethical reflections. Hastings Center Report, 51(2), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1240

- Israel, B. A., Krieger, J., Vlahov, D., Ciske, S., Foley, M., Fortin, P., Guzman, J. R., Lichtenstein, R., McGranaghan, R., Palermo, A., & Tang, G. (2006). Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban research centers. Journal of Urban Health, 83(6), 1022–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1

- Joosten, Y. A., Israel, T. L., Williams, N. A., Boone, L. R., Schlundt, D. G., Mouton, C. P., Dittus, R. S., Bernard, G. R., & Wilkins, C. H. (2015). Community engagement studios: A structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1646–1650. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- Kania, J., Williams, J., Schmitz, P., Brady, S., Kramer, M., & Juster, J. S. (2021). Centering equity in collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 20(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.48558/RN5M-CA77

- Marrero, D. G., Hardwick, E. J., Staten, L. K., Savaiano, D. A., Odell, J. D., Comer, K. F., & Saha, C. (2013). Promotion and tenure for community-engaged research: An examination of promotion and tenure support for community-engaged research at three universities collaborating through a clinical and translational science award. Clinical and Translational Science, 6(3), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12061

- National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. (2022). The Healing Power of Community Engagement. National Institute of Health. https://ncats.nih.gov/files/NCATS_Community-Engagement-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- Ohmer, M. L., Mendenhall, A. N., Mohr Carney, M., & Adams, D. (2022). Community engagement: Evolution, challenges and opportunities for change. Journal of Community Practice, 30(4), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2022.2144061

- Ojikutu, B. O., Stephenson, K. E., Mayer, K. H., & Emmons, K. M. (2021). Building trust in COVID-19 vaccines and beyond through authentic community investment. American Journal of Public Health, 111(3), 366–368. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306087

- Okun, T., & Jones, K. (2001). Dismantling racism: A workbook for social change groups. dRworks. https://www.dismantlingracism.org

- Parkhurst, M., & Preskill, H. (2014). Learning in action: Evaluating collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 12(4), A17–A19. https://doi.org/10.48558/BCC5-4275

- Peterson, A., Charles, V., Yeung, D., & Coyle, K. (2021). The health equity framework: A science- and justice-based model for public health researchers and practitioners. Health Promotion Practice, 22(6), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839920950730

- Sprague Martinez, L., Chassler, D., Lobb, R., Hakim, D., Pamphile, J., & Battaglia, T. A. (2023). A discussion among deans on advancing community engaged research. Clinical and Translational Science, 16(4), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.13478

- Wallerstein, N. B., & Duran, B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376

- Wallerstein, N., Oetzel, J. G., Sanchez-Youngman, S., Boursaw, B., Dickson, E., Kastelic, S., Koegel, P., Lucero, J. E., Magarati, M., Ortiz, K., Parker, M., Peña, J., Richmond, A., & Duran, B. (2020). Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119897075

- Walsh, K. (2022). Front Health Serv Manage, 39(2), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/HAP.0000000000000158