Introduction

Children with LGBTQ + parents often have to navigate a complex and shifting set of circumstances related to heteronormativity, transphobia, and anxieties about the erosion of the “natural” family. Family, a social policy and practice that structures modes of belonging and recognition, becomes the grounds for these children’s understanding of self. These children are often tasked with narrating their family in ways that pull from language and representations that don’t reflect their own experiences. Further, the children of these families become pedagogs, teaching others about the dynamics of gender and sexuality in their kinship structures, and are often called upon as examples of either the normalcy of LGBTQ + subjectivity or the embodiment of immorality related to the queering of family. Laws and social practices surrounding recognition of LGBTQ + family set in motion a modality of thinking that charges these children with an immense amount of responsibility and obligation. Indeed, it is their own kinship structures that often cause the occasion of social debate surrounding gender and sexual norms (Epstein Citation2018; Haines et al., Citation2018). These children, then, are queered not necessarily by their own sexuality, but by their parent’s relationships and desires (Ammaturo, Citation2019; Dyer, Citation2019).

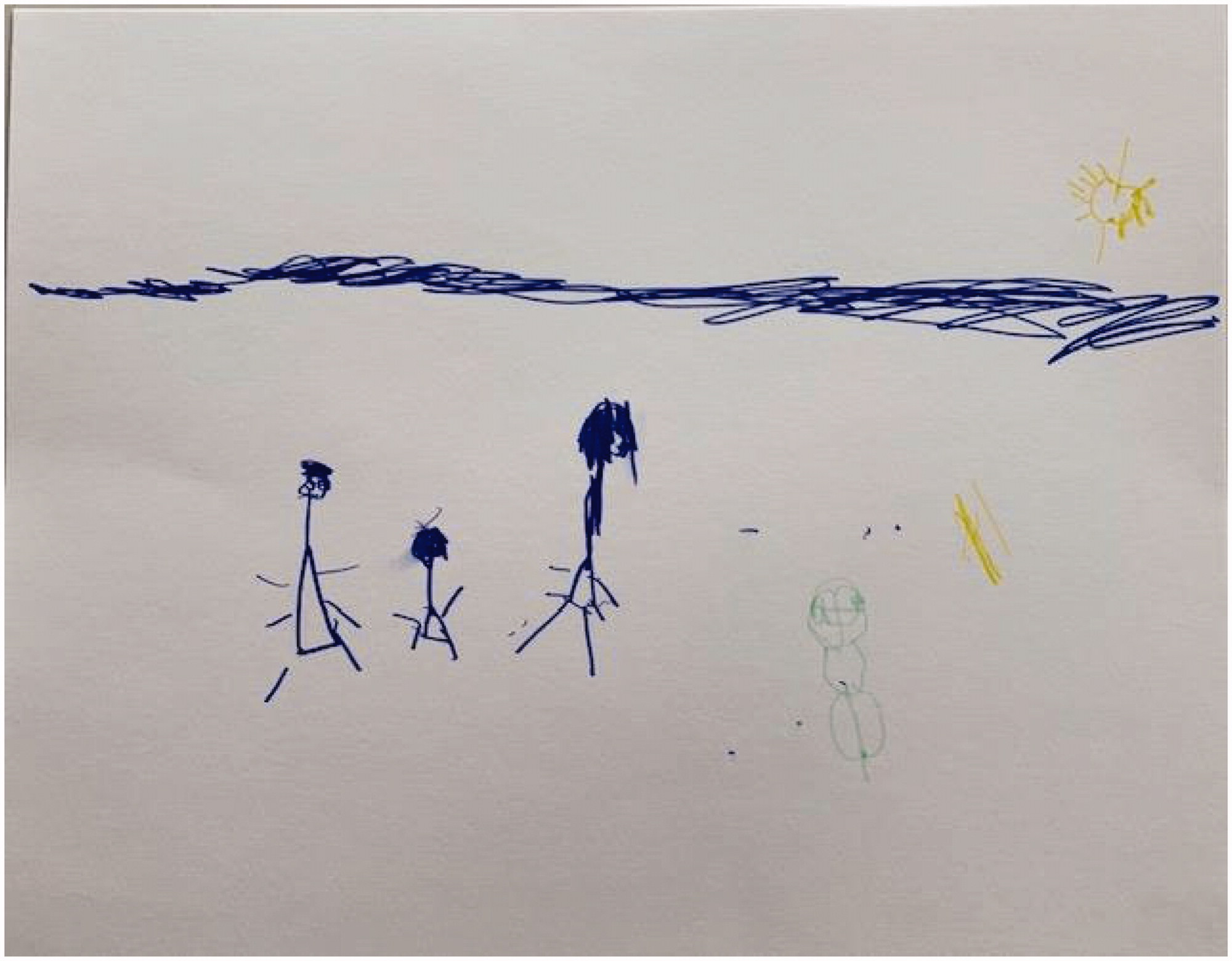

In an effort to center the experiences of these children, in this article we draw from qualitative interviews and arts-based research conducted with 30 children from Ontario, Canada, between the ages of 6 and 12, who each have at least one LGBTQ + parent. The children were asked to draw a portrait of their family and to respond to semi-structured interview questions about their kinship structures. The mingling of verbal responses to questions posed by researchers, the elicitation of family portraits, felt and observed affective dispositions, and our own exposure to theories of child development, have helped us to archive and understand the insights shared with us by the children. From them, and through the process of qualitative research, we learned that LGBTQ + family is a constitutive relationality that provides care and meaning in their lives. In conservative media and popular discourse, these children are repeatedly pointed out as exemplary of the disintegration of the normative family, but in our project, they hold their families together in aesthetic renderings of care and protection. Our study is centrally concerned with the methodological question: How does a turn to affect theory and the deployment of arts-based research methods complicate conventional qualitative research done with children? Attention to children’s affective states and the utilization of arts based methods, we find, are useful precisely because they embrace the instability of truth (rather than reify it) and thus get at the core of ambivalence that structures children with LGBTQ + parents perspectives on family.

Our research project, titled, “Drawing Queer and Trans Family: Understanding Kinship through Children’s Art” offered representational space for children with LGBTQ + parents to disrupt or trouble modalities of thought about their lives that render them in need of repair or unable to make complex meaning from their experiences. The testimonial function of their drawings helps to draw meaning from what might otherwise elude language or classification. Centrally, we were concerned with how the children interpret family, given the structure of their own may differ from hegemonic definitions of kinship, and beyond that, how they explain attachment and belonging under the terms of these relationships. The children we interviewed live in either Toronto or Ottawa, Ontario, but have had distinct experiences, in part because of race, gender, class, sexuality, migration and citizenship. These cities were chosen because they are where the researchers work, reside, and are themselves members of LGBTQ + communities. The research team consisted of two university faculty members, a PhD student, and one undergraduate student. They are white settlers, who come from families that represent a range of socio-economic backgrounds. The lead researcher in Toronto is a queer parent. Interviews and drawing sessions took place either in the child’s home or in a public library, between May and September, 2019.

Through the drawings and conversations with children, it was revealed that the children’s perspectives on family are not straightforwardly dictated by ideologies about queer and trans cultures, but involve a complex constellation of affect, power, sensation, curiosity, and social structures that have to do with the minutiae of kinship. In this article, we share findings and provide commentary on some of their drawings in order to contribute to knowledge about how children in LGBTQ families become aware of their social locations and enact everyday ways of being with and a part of kinship structures. In relation to our research, affect theory provides a language with which to register the excesses of subjectivity that cannot easily be sufficiently addressed in either arts-based methods or semi-structured interviews. Beyond the verbal offerings and aesthetic expressions given to us by the children, there is also the affective realm of fantasy, the unconscious, and the sensory experiences that offer “a critical sociality of intense feeling” (Crawley, Citation2017, p. 5).1

In creating art that expresses their understanding of family, the children gift us with aesthetic renderings of their lifeworlds, shaped by the contours of recognition, belonging and pedagogy. In the interviews, many of the children regularly positioned themselves as “normal” and insisted that their kinship structures should be normalized. Thus, our analysis of the findings identifies the core of ambivalence that often structures childhood in LGBTQ families: Their families are, according to their children, normal, and yet, they exist within a world that struggles to normalize their experiences. What’s needed, we have found, is a mode for understanding the ways that children’s insistences on normalcy can cover over a dense knot of experiences related to growing-up, gender, sexuality, schooling and subject-formation. A major impetus for our research with children who have LGBTQ + parents is to better understand the usefulness of drawing as such a mode of understanding. Arts-based research is useful because it can help to gather information beyond the limits of verbal speech. The drawings, as we will discuss, offer a different form of inhabited speech that provides insight into the affective, epistemological and pedagogical terrains of kinship.

In this article we pull from various theoretical lineages (queer theory, trans studies, childhood studies, and affect theory) to offer analysis of seven of the interviews and related drawings from the project. The seven drawings and children themselves were chosen because they represent a sample that is representative of our findings. Ultimately, this article seeks to illustrate some of the children’s experiences of queer and trans kinship, all the while calling attention to the ways that they create narratives of family that extend beyond convention. Our discussion of the children’s art and accompanying interviews emphasizes their labor as pedagogy. Throughout the project, they teach us about their lives more than we can offer them knowledge about themselves. Indeed, some of the children explained that they often had to teach peers and adults about LGBTQ families. The children, we find, are not lucidly tormented by homophobia and transphobia, but tired from having to teach others about their reality. Though the cultural spheres children in Toronto and Ottawa inhabit are increasingly marked with representation of LGBTQ subjects, and some of the neighborhoods they live in have relatively large queer and trans populations, there remain unanswered questions that children with LGBTQ parents are tasked with resolving. The children’s drawings are important because they can also lead us away from more deliberate processes of cognition and toward the affective and embodied experience of growing up with LGBTQ parents. In bringing affect theory to bear on our research, we become attuned to the unconscious, emotional, nonlinguistic and subjective exchanges that not only occur between child and researcher, but can also be contained in the artwork. The paper they draw on, for example, becomes shaded with affect and aesthetic expressions of the excesses of language. Affect, we argue, can offer the researcher a spirited conduit of insight into the child’s subjective reality.

Rather than confine our understanding of the well-being2 of children with LGBTQ parents to research about them, we invited the children to verbally and aesthetically render some of the realities of their own existence. As much as possible, we allowed them to embrace, challenge or re-route the expectations and regulations that frame their perceptions of family. We have used drawing as a form of aesthetic inquiry, alongside methods taken from the social sciences, such as semi-structured interviews. Beyond willfulness and conscious desire, drawing can tap into the creative space of fantasy and can work toward the creation of an aesthetic object with which to understand the affective excesses that leak beyond the known or spoken realities of exclusion. In creating drawings of their families and engaging in semi-structured interviews, the children have provided us a considerable amount of insight into their social and material worlds. Having introduced the overarching stakes of this research, we now move to a discussion of why we bring affect theory to bear on our research, discussing its uses and limitations for capturing the surpluses of qualitative research methods. After doing so, we introduce some of the children who offered their time and artwork to help us understand what family means to them. In centering the words, affects, and symbolic expressions of children, we embrace their capacity to resist discourses of innocence and sentimentality.

Affect, drawing and verbosity

In most of the research sessions we conducted for “Drawing Queer and Trans Family,” the children began to draw quietly, taking time to choose colors and actively deciding where on the page their marker should first make impact. As they do so, affect swirls around the room and is exchanged between researcher and child. Some of this affective energy then becomes a part of the drawing, while in other cases, it refuses to be contained. A few of the children, though, begin to speak immediately and do not pause for the duration of the session. They offer up language with ease (or perhaps use language to suppress anxiety), explaining each choice as it is made and sharing narrative details about their daily life, such as excursions they take with their family, and details about their best friends and cousins. For the children who chose not to speak while involved in the act of drawing, many of the narrative and affective excesses of their family configuration are held in their drawings. Our method and underlying theoretical framework allows the affiliations and resistances between drawing, flesh, text, interpretation, and embodiment, to become clarified. Turning to affect theory enables us to better understand the unconscious impulses that are represented in the children’s drawings, always already also mediated by culture by the time they are represented on paper. Arts-based research methods with children, we suggest, are uniquely useful for their capacity to create a potential space (Winnicott, 1971/Citation2005) for reading children’s affect.3

Affect theory does not describe a unified perspective, but refers to a body of scholarship and practice that theorizes the existence, management, sociality and sometimes, biological origin, of affect. According to Kathleen Stewart, “power is a thing of the senses” (Citation2007, p. 84) and thus, animates everyday life and is expressed in affective territories. Because the child’s affective disposition can be quite intense (tantrums, frustrations, crying, immense joy, for example) it is an area of abundant study, particularly in the fields of psychology and neuroscience (Posner, Russell, & Peterson, Citation2005; Thornton, Citation2011). Sara Ahmed moves beyond the bounded, liberal subject to write about “affective economies” in order to show “that emotions do not positively inhabit any-body as well as any-thing, meaning that “the subject” is simply one nodal point in the economy, rather than its origin and destination” (Citation2004, p. 121). Ahmed’s theorizing is particularly important for a study about the potential homophobia and transphobia experienced by LGBTQ + families. Ahmed’s theorizing diverges from those who locate affect deep in the biological structure of the individual. Throughout three volumes of his infamous study, Affect Imagery Consciousness (Tompkins, Citation1962), describes the existence of nine affects that are biologically inborn. Eve Sedgwick, the renowned queer theorist, later draws from Tomkins’ concept of affect to further the field of queer theory. As one reviews literature in the field of affect theory, it becomes apparent that a theory of affect is not reducible to a universal, agreed upon phenomenon, event, or structure. Aubrey Anable has helpfully responded to suggestions that affect theory can sometimes too heavily emphasize “the unrepresentable” or “shade too easily into purely subjective responses to the world” (Citation2018, p. 9). Anable reminds us that such imprecisions are a result of affect theory’s “fundamental stakes” of intervention: “that the legacies of structuralism and poststructuralism created theoretical impasses built around the imprecision of symbolic systems in wholly accounting for human experience” (Anable, Citation2018). Despite its tensions and contradictions, affect theory acquires utility in its effort to theorize the planes of fantasy and non- linguistic, sensory and emotional experiences that inform our understanding of both self and other.

We turn to affect theory for help thinking about and describing the shifting relations that are made and moved between children and those who research childhoods. Gregg and Seigworth write that affect is “found in those intensities that pass body to body (human, non-human, part- body and otherwise), in those resonances that circulate about, between and sometimes stick to bodies and worlds, and in the very passages or variations between these intensities and resonances themselves” (Citation2010, pp. 1–2). They suggest we think about affect as a “force of encounter,” though this encounter may not in the moment feel “especially forceful” (p. 2). In the process of conducting arts-based and qualitative research, the encounter between researcher and researched is crowded with affective content. The categories of “researcher” and “child participant” always already create a sense of hierarchy that can be affectively charged. Though not always a volitional or intentional hierarchy, the affective structure through which child and adult come to know each other are implicated in what the child feels comfortable sharing. Beyond the affective economy of exchange between researcher and child participant, there is also the affect related to the drawings. Anable, whose study of affect emerges from a critical theorizing of video games, writes: “I read video games not as containers of and for affects that float around between bodies and things but rather as media that have specific affective dimensions, legible in their images, algorithms, temporalities, and narratives, that can be interpreted and analyzed” (p. 10). For Anable, “reading for affect” is “the only method we have for apprehending something so fugitive” (p. 10). In agreement with Anable’s methodological insistences, we suggest that reading the children’s drawings for affect can provoke insight into the details of their creation. Further, the drawings can also improve an explanation of the relationship between children’s social experiences and cognition, as they provide an aesthetic resource that helps to visually render their discursive framing of family.

Though their consent was required, parents/caregivers could not be present in the research session and this was, in part, an effort to minimize their affective sway over the child’s expression. Of course, affect swirls with ideology and gets inside of us, even from a young age, so the children’s affective responses to our questions and instruction to draw their family cannot reliably be said to be immune to their parent’s affective disposition. Deeply conditioned by the instrument of affective reaction, the children arrive to the interview with somatic knowledge of how their parents want them to feel and express themselves. The feelings of curiosity, apprehension, openness and alertness that are incorporated into the child’s response to the researcher’s presence have also to do with the ways their parents have taught them to manage affect. Indeed, children’s affective life becomes a site of management, optimization, risk and education for teachers and parents. In this way, Anable’s concept of “reading for affect” is useful to us because it allows us to consider both the empirical data provided in the children’s drawings and interviews, and the potential planes of fantasy, imagination, and resistance that they offer our project. In embracing the affective terrain of research with children, we accept Chesworth’s call to understand research with children as “an emergent navigation” that requires being “reflexive to the ethical dilemmas and methodological decisions that emerged throughout the research” (Citation2018, p. 854). To provide a space that feels comfortable and safe, all the while activating a fluid and adaptive strategy for the co-productive creation of knowledge, requires attention to the affective entanglements of the children’s aesthetic production and social locations.

We also understand the drawings themselves to be aesthetic objects that inspire our own affective responses. We have regularly been affected by the children’s drawings, and through them have experienced aesthetic moments of rapport, learning, and joy. Christopher Bollas describes what he calls an aesthetic moment: “…They are fundamentally wordless occasions, notable for the density of the subject’s feeling and the fundamentally nonrepresentational knowledge of being embraced by the aesthetic object” (Citation1987, p. 31). He continues, “Time seems suspended. As the aesthetic moment constitutes a deep rapport between subject and object, it provides the person with a generative illusion of fitting with an object” (Citation1987, p. 32). Bollas’s description of aesthetic moments is useful in describing both what happens for the child while drawing and what happens for us, the researchers, when we get to view the child’s creation. In both cases, the aesthetic experience can be transformational, helping to elicit new knowledge and insight into the intractability of kinship. In asking how the concept of kinship materializes in the aesthetic objects the children create, we have begun to assess the affective traces of experience both left in the drawings and escaping beyond them.

The children themselves: Pets, pedagogy and siblings

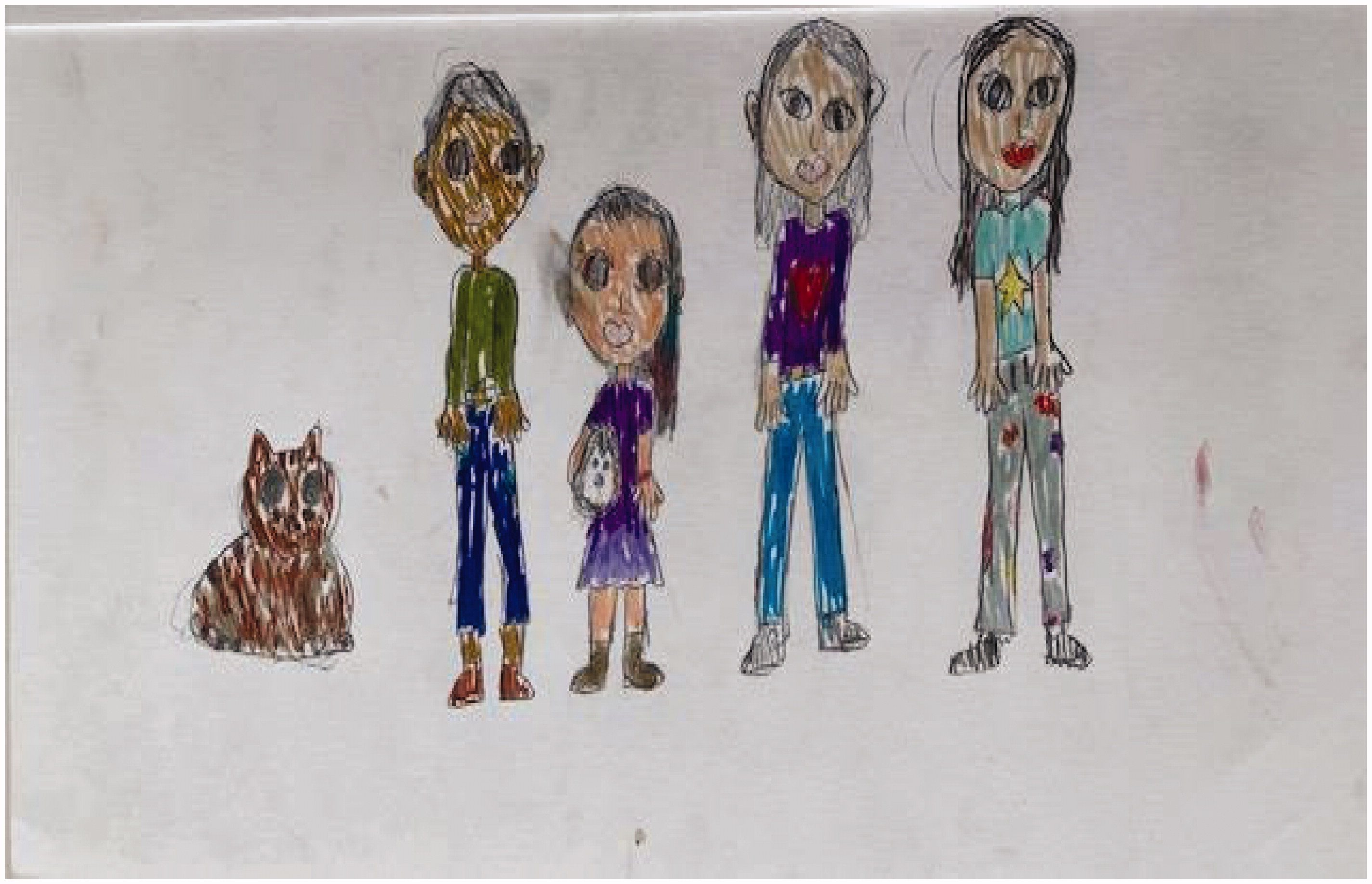

N is an 8-year-old who is very proud to have bright, died hair. Before I ask any questions, N quickly explains to me that he is a trans boy but prefers to simply be called a boy. He wears a bracelet with the trans flag colors on it and says he really likes fashion. N continues, “In the summer between SK Kindergarden and grade 1…I didn’t really feel like a girl and I didn’t feel comfortable being called a girl but I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to be called so I said I was non-binary because at the time I would say I’m neither, but, um, I just didn’t like the feeling of being called a girl so I said I was neither. I was non-binary so you should use the pronouns they/them. So that was like for a year or two and then, actually, like, this year or last year I got, like, comfortable being called a boy because I was thinking about it for a long time … So that’s basically how I transitioned but I got bullied a lot about that kind of stuff.” N has a core group of friends that “are always there” and emits an air of confidence. “I don’t really care about being transgender, I don’t even use that word all the time, I just say I’m a boy and that’s it but for people who don’t understand that I’d say I’m a transgender boy.”

N has two moms and an aunt that he adores, is Filipinx, and loves his cat. He has an acute understanding of reproduction, gender, and enjoys art. At one point N tells the researcher that a question is too vague and helps to sharpen its wording. In this moment, the child is expressly “co-creating the very questions we sought to resolve” (Meadows, Citation2018, p. 14). N seems to want to talk about his family with the researcher but also states clearly that sometimes it is exhausting: “When I say I have two moms they ask me… “how is that possible?… I say, well, it’s possible so I don’t really want to talk about it.” This is not only affective labor, but also pedagogical. The demand to articulate knowledge of his arrival into the world and conception, even, suggests that the children he encounters haven’t been given adequate templates to draw from in order to imagine a child like N.

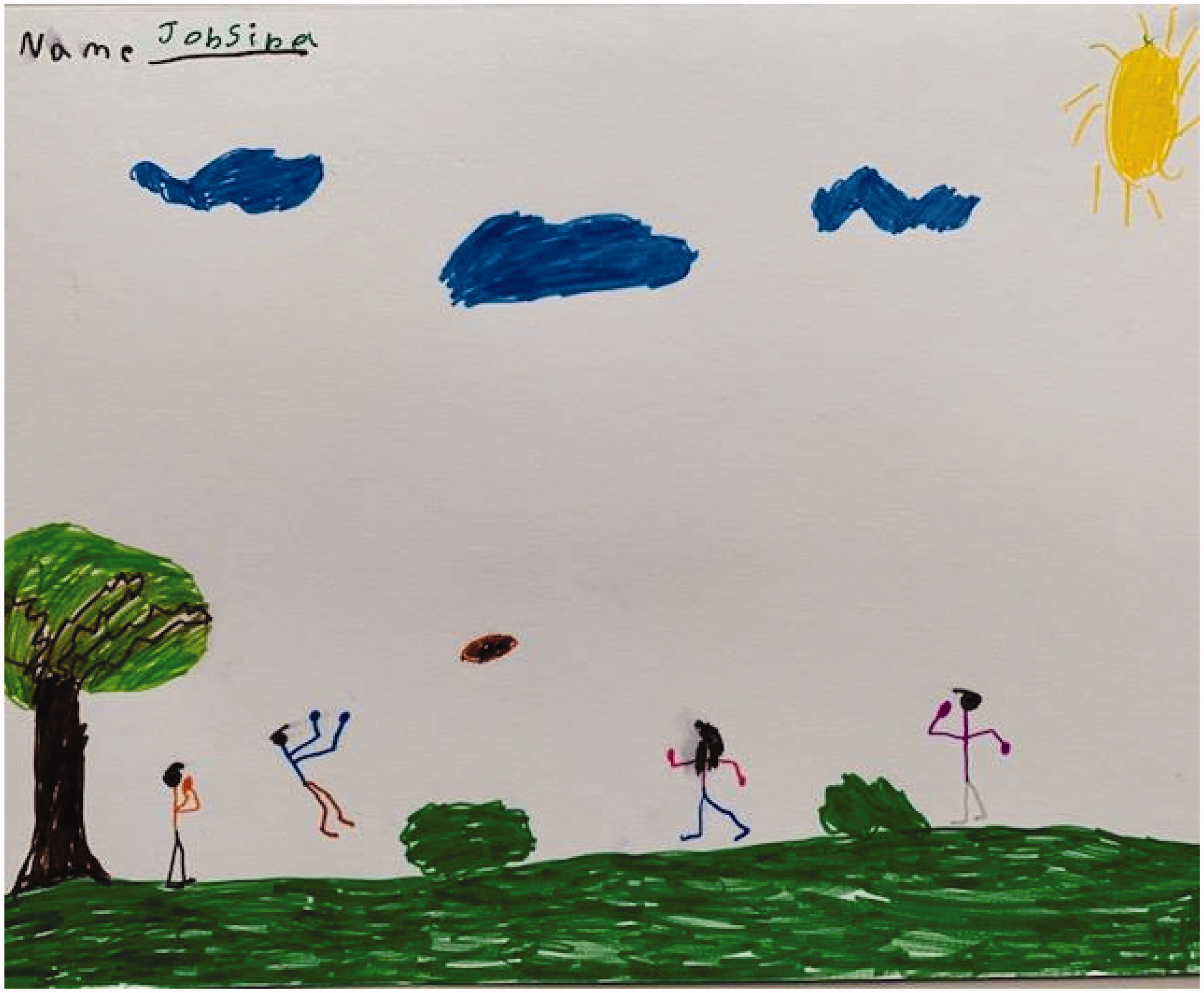

J (7) and B (11) are siblings who have been in Canada for approximately six months after migrating for reasons of well-being. The youngest moves around the room excitedly while the older sibling sits alone, quietly observing the researcher. They are excited by the range of markers at their disposal for the drawing, as many of the children are. From their drawings, you would not know they have the same family. Indeed, their drawings remind us that siblings often interpret the world as distinct from each other. They are both learning the English language and thus, their responses to interview questions are sometimes nods of the head or requests for clarity. The questions don’t always solicit verbal responses, but their drawings help to offer commentary on kinship and the social processes of belonging. In B’s drawing, he is holding his younger brother’s hand and his parents are also holding hands. B chooses a yellow marker to draw his family; he draws himself wearing a mask, which he says is to protect him from “contamination.” He likes being in Canada with his family but says he isn’t sure how long they’ve been here. He says that at school, the only question he receives about his family is if he has a brother. J draws his family playing football and chooses a brown marker to draw their faces. When asked by the researcher “Where do you go with your family?” he replies: “To Canada,” and explains that after flying from Mexico he arrived when it was night. He says that he has “21 or 22 classmates” and they are all his friends, though they never speak about his family.

J tells the researcher that his teachers don’t usually ask about his family, except on Mother’s Day, when he explains that he made a gift for “two mothers.” His sibling, B, tells the researcher that he calls his parents “Mom” and “Dad,” and draws one of his parents with a beard. Their aesthetic interpretations and verbal descriptions of family are at odds from each other, which points to a distinct understanding of their family form. The tentacular nature of family allows it to be reconstituted through their individual interpretations of their parents. Their enunciations of kinship are informed by the realities of their lives, the content of which is specified by their individual, unique fantasies and imaginations. In many ways, experiences with family underwrite and verify both children’s existences, but these experiences differ and thus, their drawings are unalike.

At 12 years old, N is one of the oldest children interviewed. She has thought a lot about her family and its gendered make-up, it seems, and answers questions with mature clarity. “I feel like I can talk to them about anything,” she says, in reference to her family. She also has a best friend that “feels like family.” N tells the researcher that upon first meeting, many people assume one of her parents must be a dad, despite the fact that she has two moms. She discloses that she has to quickly correct them when this mistake is made. “Gender is an achievement, rather than an attribute,” Tey Meadows, drawing on Judith Butler, explains. This achievement “is aimed at significant others assumed to be oriented to its production” (Citation2018, p. 8). In this moment, the 12-year-old is given the responsibility of producing and defending her parent’s gender. Meadows explains that the social processes of gendering are complex operations that both young people and adults are involved in. In her interview, N provides an example of how the children must defend their parents and provokes us to bestow value on her own work as a pedagog who must help other children widen their perception of gender.

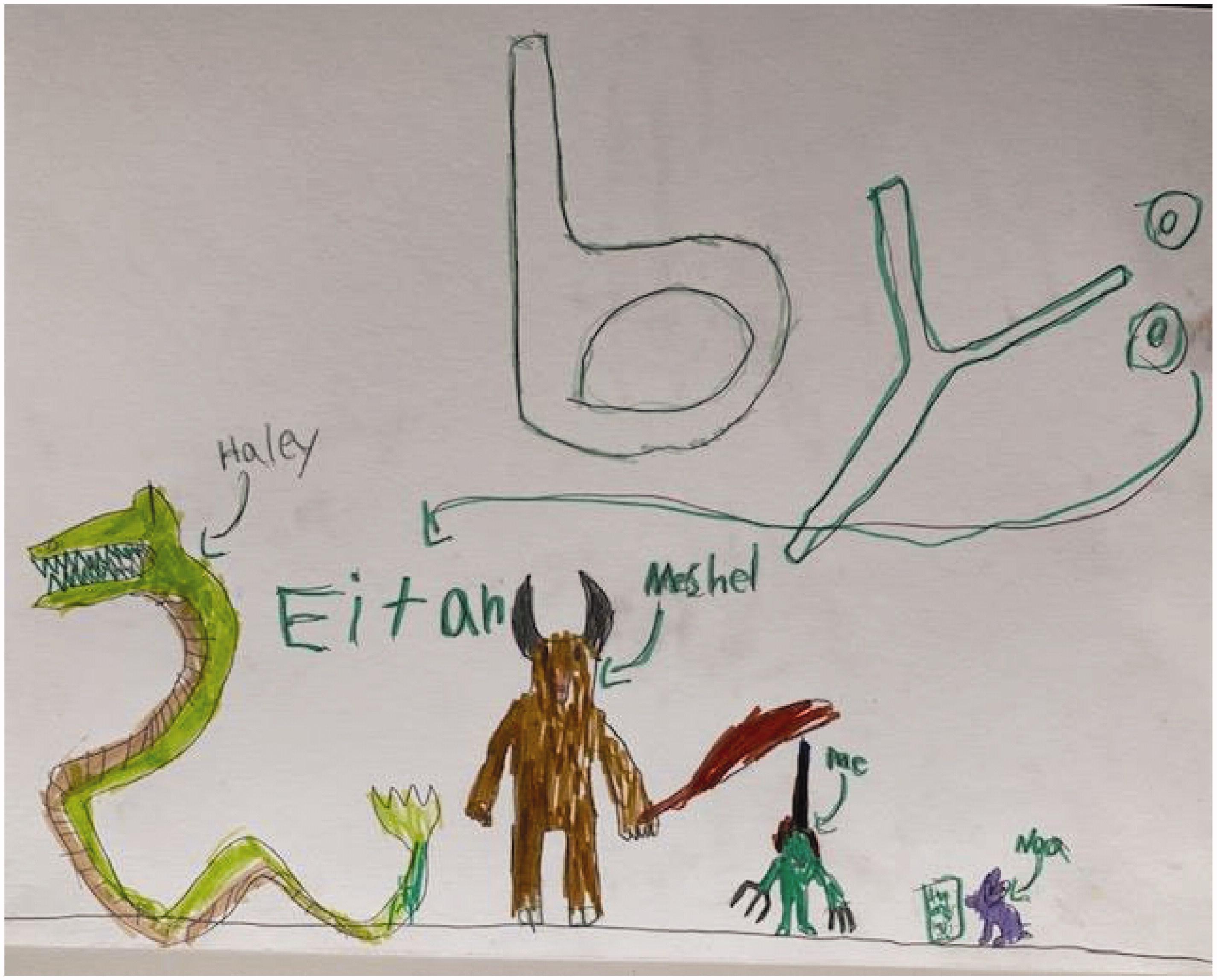

N says that kids at school used to ask a lot of questions about “how she was born, which is weird to explain, especially when I was younger.” The researcher asks if she anticipates that she’ll always have to explain that and she quickly responds, “Yes.” She continues, “My parents have a lot of friends who are, and their kids have two moms or two dads, so, um, I know a lot but not from school so I know lots of people won’t know so I’m fine answering.” She says that “she’s used to explaining a lot.” Her younger brother, E, who is 8 years old, is also interviewed and equally confident. They are White, spend a lot of time with their grandparents, and our interview takes place in a house on a street with many large homes. E seems to find a lot of pleasure in drawing and luxuriates in the offer of a representational space for communication. He draws one mom as a dragon because “she always does yoga in the morning so she’s kind of, like, flexible” and the other mom “builds a lot so she’s holding a club.” He appears in green and has spikes; his sister appears as a purple bunny because “she’s fast and she likes to read and when she was little she was always really shy.” When asked why he chose to draw his family as these characters, he says that “people are boring.” When asked if there is anything he doesn’t like about his family or could be improved he says he doesn’t like that his sibling “sings Ru Paul’s Drag Race all of the time.” He has fish but also wants a pet pig, he tells the researcher, and says the pig would be a member of the family. “Sometimes my grandfather picks me up so then they think he’s my dad” and then when he corrects them they say “It’s pretty cool” and he agrees. The researcher asks what it feels like to know people are going to ask about his family and he replies, “Just normal.”

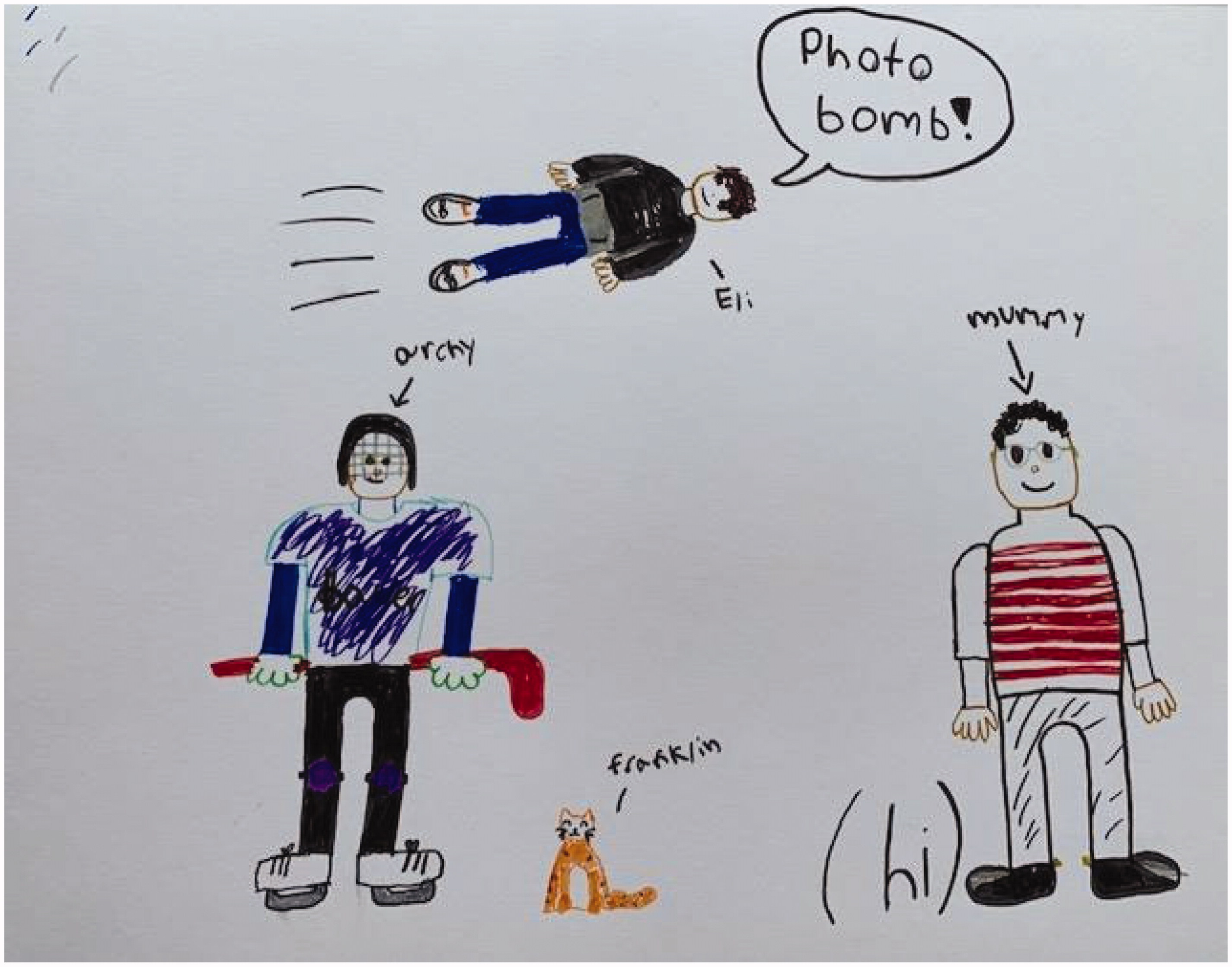

E is a 9-year-old with two moms and a cat, who he includes as a member of the family. He is affable and immediately comfortable with the researcher, excited by the task of drawing. We meet in the public library, in a private room, where he draws a picture of his family, with one mom in hockey gear. At first E is worried that he’s drawn his moms too close to each other and won’t be able to include all of the desired detail because there isn’t room. He then decides it makes sense that they are close because “they’re partners.” E likes to read, draw and play card games. He asserts that his chosen family is also important to his understanding of kinship. When asked to define chosen family, he says “it’s basically like people or friends that I am very close to” and that they are chosen by both himself and his parents. When asked what he likes about his family he says, “Well, it’s kind of cool having two moms” and diplomatically states that “They are both good parents in different ways.” E attends a school where there are other kids with two moms and two dads and says that it is a nice thing to know that they are there. One of E’s parents runs a community arts project and E shares many details about it with the researcher, obviously proud of his parent.

Z has turned 6 less than a week before he participates in the study. He jumps around the room and is excited to show off his toys. He is Romanian Indian, lives west of downtown, and goes to a school with a number of other children who have LGBTQ + parents. Though less interested in the act of drawing, Z is proud to show his to the researcher and explain that he included his favorite toy as a family member. Indeed, much of his interview involves discussion of toys and throughout he plays with one of them. And like many of the children, he also gets excited when there is an opportunity to talk about pizza. When asked what he likes about his family he says that he’s allowed to watch TV and that “he has two moms.” When asked if there is anything he dislikes, he smiles and turns our attention away from the question and toward the toy. In the interviews, patterns emerge: the children express discordant feelings of difference and normalcy. They all express a visceral discomfort when asked if there is anything they don’t like about being a member of their family, but they provide variant reasons for why they do like being in their family. Because schooling is a constitutive force in subject formation, many of the children made reference to it in their interviews. It is clear that the school cannot always adequately accommodate their subjectivity and difference but this problem is one that they seem to have normalized.

Through a combination of language, affect, and aesthetic symbolization, the children provide us with data to analyze. Many of the children include animals and toys in their representations of kinship, offering us a symbolic object with which to think about cohabitation and companionship with other species and entities. The networks of care drawn, which include toys, trees, animals, and sports, undermine emphasis on people as care givers and recipients of love. In this way, their drawings offer what Donna Haraway might deem “category-breaking speciations and knottings” (Citation2016, p. 97). They cause us to think “well about multispecies living and dying on earth at every scale of time and place” (p. 98). The children’s inclusion of toys and animals as kin is not simply play, it is a heartfelt representation of kinship. “Kin,” Haraway writes, “is a wild category that all sorts of people do their best to domesticate” (p. 2). The drawings suggest that we should all, perhaps, organize ourselves around such beliefs and naturalize the beingness of landscapes, objects of play, and animals. The children situate themselves within broader ecologies of kin, cultivating generative representations of cohabitation and reciprocal care. Children, it is said, don’t chose the family into which they are born. But, in their drawings they are able to make choices about who and what counts as kin. Their drawings become a grammatical and symbolic presentation of kinship in which these objects are pulled inside the orbit of family.

While the goal of integrating children with LGBTQ parents into schools and community spaces is often pointedly expressed, we find that much of the Labor of inclusion falls on the children themselves. In schools, there is the tendency to reveal to students that some families have two moms or two dads, but the origins of their children are obscured. That is, how the child came to be and related issues of reproduction, medical and state bureaucracy, and histories of hostility, are cast out of conversation. Within such politics of inclusion, there is often room for acknowledgement of LGBTQ families but not adequate space to address the contradictions and tensions that come with being a part of a family that has historically been without legal protections or social recognition. Ultimately, the neoliberal move toward embracing diverse family configurations can also draw attention away from structural inequalities and social phobias, and obscures its conditions of reproduction, pregnancy, and conception. Thus, the very notion of these children’s rights must be understood in relation to the very specific dynamics of medicine, reproduction, economic, racial, and gendered injustices. Differential attributions of childhood well-being are often the result of differential access to financial capital. The homes the researchers entered, for example, are material elaborations of economic inequities- some large and others small, some rented and others owned.

In relation to our study, very few of the children’s parents wanted to shield their child from knowledge of gender or sexuality, and many expressed gratitude to us for leading the children into conversations about these topics. We find, in some ways, that this also points to a failure of schools that rely on neoliberal notions of a self-governing family who creates and shares their own resources. All of the children, it seemed, were given latitude by their parents to decide how much and when they would tell others about their family. The interviews and related drawings render palpable the complexities of the imperative to teach children about gender, sexuality, and constructions of the family. Many admitted that they had searched for the researchers online and vetted them before responding to the promotional material circulated. Sinclair-Palm and Gilbert (Citation2018) point out that amidst conflicts and campaigns related to protection and discrimination of trans youth in education, “trans youth are going to school, growing up, making and losing friends, falling in and out of love, experimenting with and claiming multiple identities, and negotiating and challenging social norms” (p. 321). Similarly, in turning to and emphasizing the everydayness of family relations and children’s negotiations with the pleasures and constraints of growing up, our study finds its pace in the hopes, desires and relationships formed by children under the shadow of campaigns waged for and against their families, but also, beyond the reach of ideology and the hyper-management of children’s anticipated futures. One lesson we’ve gleaned from this study is that when we pay attention to children, and allow them self-determination, they regularly blast apart the ideals of childhood innocence that constrain recognition of their agency.

Conclusion

It matters which stories researchers tell about the nature of childhood because from the depths of these stories we build theories of child development. The task of our research has been to become capable of procuring insight into children’s realities and fantasies concerning queered kinship, all the while clearing space for them to lead the way. The pairing of arts-based research methods and affect theory has helped us to undermine some of the stale qualitative methodological tendencies to suppress the unknowable contours of children’s experiences. The children involved in our study have nurtured our ability to think both concretely and imaginatively about their realities, and to notice the affective discontinuities between what is said and what is drawn. In conducting this study, the deepest revelations have emerged from the children’s capacities to disrupt what we thought we knew about their experiences. The combination of drawing and semi-structured interviews helped us to better understand how the processes of making family and bonds of care are processed by children.

These children have helped to transform our understanding of childhood more than we have taught them about what it means to grow up with LGBTQ parents. Encoded into the narratives they produce about kinship are rich and detailed experiences with schools, peers, and extended family members. In asking whether or not children with LGBTQ parents trouble or stabilize the category of family, it has become clearer that they do both at once. As Tey Meadows points out, “Our individual selves are forged through interaction. We assume social roles with an eye to how they are received by the audiences with whom we interact” (Citation2018, p. 7). Meadows explains that, “The telling of life stories is always a social process; stories are mechanisms through which we create coherent narratives of our experience, yet they are also negotiations we undertake with others of what is true and possible” (p. 207). Understanding drawing as a mode with which to render a life story and its affective vicissitudes has allowed us to commune with children who have LGBTQ + parents. In speaking with the children and observing their art, we have come to understand that their life stories are, in many ways, negotiations with the discursive frame that is offered to them by the social world. The children’s lives are embedded in a particular moment in Ontario, Canada, where a new family law has meant legal recognition of their kinship structure, all the while cuts to social welfare and education that increase their vulnerability and disperse risk across their communities are occurring. Such complex configurations of social and emotional life cannot entirely be drawn into the scope of our research and yet, we work to better understand how the social and the affective mingle to create these children’s lifeworlds. In this context, our study carries the potential to enliven childhood studies and LGBTQ studies with the inclusion of perspectives of children with LGBTQ parent(s). Their drawings add color, texture, and knowledge to both of these fields of study.

Since debates around children’s well-being become particularly salient when the child’s parents are or have been deemed unfit or pathologized for their subjectivity, it is important to turn attention toward the opinions of these children themselves. Children are often imagined to be in need of protections and care because of their inherent innocence (James & Prout, Citation2003; Robinson, Citation2013). As Aimee Meredith Cox reminds us, “children are perceived as being in need of care and attention that are grounded in the intentions of guiding and protecting” (Citation2015, p. 11). The purported universality of childhood innocence has been widely contested in the field of child studies (Bernstein, Citation2011; Dyer, Citation2019; Gill-Peterson, Citation2018; Meiners, Citation2016; Stockton, Citation2009). Lisa Farley (Citation2018) insists that childhood and adulthood are inextricable, as she explains that “childhood is a relational concept that makes the very thought of adulthood possible, even while exposing the blurry lines between these ideas” (p. 2). Farley asks: “How can we theorize psychical complexity through a study of childhood representation?” (p. 6). She finds interest in childhoods that “travel detours and open divergent corridors of growth” (p. 7). In thinking with Cox and Farley, we have worked toward a generative coalition and allyship that gleans knowledge from children all the while struggling against the too often extractive enterprise of researching childhood. We do not aim to offer proscriptive politics for a future not yet lived, but in humility, open ourselves to the places children point us toward.

Liz Chesworth argues for “a shift in the focus of attention from method towards a more reflexive consideration of the ontological, epistemological and ethical questions regarding the researcher’s engagement with children and their everyday lives” (Citation2018, p. 852). She thus desires “a more pervasive appreciation of how uncertainty permeates throughout the research process; of how our interpretations of the significance of findings, and of how these findings are constructed, are not fixed, but ever-emerging” (p. 852). For Chesworth, too much is lost in the “tendency for task-based methods to define and limit the term for children’s engagement,” especially when often the adult is readily able to re-center the assumptions they previously held, rather than be surprised by their findings (p. 853). The proposition that children can elaborate an episteme that is invigorated, not reduced, by their meaningful inclusion in the research process is in-line with our study’s purpose. The children have been crucial interlocutors who have helped to expand our imaginaries of kinship but also, lead us into surprising territory that takes us beyond any attempt to dogmatically apply “methodological tasks.” They lead us into an appreciation for the excesses of kinship that are not contained by our intellectual frameworks or methodological training. Remaining open to being challenged by the children’s knowledge enables us to be more vulnerable to surprises and let go of a strong hold over data about the assemblage of family. Perhaps, at first we were interested in severe discontinuities that are caused by the queering of kinship but that vested hold on family was soon replaced by a desire to think with and beside the children. Caught in the contemporary moment, where questions about the details of their lives seem to proliferate, and burdened by a history of exclusion, these children, to borrow from Julietta Singh, helped us to “reorient our masterful pursuits” (Citation2017, p. 3) and follow them into ambivalence and uncertainty.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannah Dyer

Hannah Dyer is an Assistant Professor at Brock University in Child and Youth Studies.

Julia Sinclair-Palm

Julia Sinclair-Palm is an Assistant Professor at Carleton University in Childhood and Youth Studies.

Miranda Yeo

Miranda Yeo is a PhD student at Brock University in Child and Youth Studies.

Notes

1 There are numerous examples of research with children that exemplifies why relying on a child’s verbal language alone does not only limit the data collected but also infringes on their right to participate in research in a way that is both meaningful and legible to them. The infamous Piaget tests conducted with children to investigate egocentric speech is one (1923; Kubli, Citation1983; Sasso & de Morais, Citation2014). Another example is the common assertion that it is necessary to help children “find their voice.” For example, Sonja Grover’s often-cited article, “Why wont they listen to us? On giving voice to participating in social research” (Citation2004) provides a complex example of the need to change the way we, as researchers of childhood, listen, feel, and observe children’s affect and art, rather than “give language” to children.

2 In the field of psychology and related studies of children’s development, there is a tendency to use children’s “well-being” as a metric of neoliberal success. Many definitions of well-being are contingent on social class, economic status, and cultural capital, and we aim to turn away from neoliberal metrics as a marker of successful development. We aim, rather, to elaborate a definition of well-being that moves beyond positivistic tendencies to flatten a child’s development on a plane of competition or categorical equivalencies and towards an embrace of the affective energy of connection between the child and their social world.

3 Thank-you to reviewer 2 for helping to provide guidance with which to make this point more clear.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2004). Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117–139. doi: 10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

- Ammaturo, F. R. (2019). Raising queer children and children of queer parents: Children’s political agency, human rights and Hannah Arendt’s concept of ‘parental responsibility’. Sexualities, 22, 1149–1163. doi: 10.1177/1363460718781997.

- Anable, A. (2018). Playing with feelings: Video games and affect. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bernstein, R. (2011). Racial innocence: Performing American childhood from slavery to civil rights. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Bollas, C. (1987). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unknown thought. London, UK: Free Association Books.

- Chesworth, E. A. (2018). Embracing uncertainty in research with young children. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31(9), 851–862. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2018.1499982.

- Cox, A. (2015). Shapeshifters: Black girls and the choreography of citizenship. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Crawley, A. T. (2017). Blackpentecostal breath: The aesthetics of possibility. New York: Fordham.

- Dyer, H. (2019). The queer aesthetics of childhood: Asymmetries of innocence and the cultural politics of child development. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Epstein, R. (2018). Space invaders: Queer and trans bodies in fertility clinics. Sexualities, 21(7), 1039–1058. doi: 10.1177/1363460717720365.

- Farley, L. (2018). Childhood beyond pathology: A psychoanalytic study of development and diagnosis. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Gill-Peterson, J. (2018). Histories of the transgender child. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gregg, M., & Seigworth, G. J. (Eds.). (2010). The affect theory reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Grover, S. (2004). Why won’t they listen to us? On giving power and voice to children participating in social research. Childhood, 11(1), 81–93.

- Haines, K. M., Boyer, C. R., Giovanazzi, C., & Galupo, M. P. (2018). “Not a real family”: Microaggressions directed toward LGBTQ families. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(9), 1138–1151. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1406217.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- James, A., & Prout, A. (2003). Constructing and reconstructing childhood. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kubli, F. (1983). Piaget’s clinical experiments: A critical analysis and study of their implications for science teaching. European Journal of Science Education, 5(2), 123–139. doi: 10.1080/0140528830050201.

- Meadows, T. (2018). Trans kids: Being gendered in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Meiners, E.R. (2016). For the children? Protecting innocence in a carceral state. Minnesota, MN: Minnesota University Press.

- Posner, J., Russell, J. A., & Peterson, B. S. (2005). The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 17(03), 715–734. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050340.

- Robinson, K. H. (2013). Innocence, knowledge and the construction of childhood: The contradictory nature of sexuality and censorship in children’s lives. London, UK: Routledge.

- Sasso, B. A., & de Morais, A. (2014). Egocentric speech in the works of Vygotsky and Piaget: Educational implications and representations by teachers. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(8), 133–143.

- Sinclair-Palm, J., & Gilbert, J. (2018). Naming new realities: Supporting trans youth in education. Sex Education, 18(4), 321–327.

- Singh, J. (2017). Unthinking mastery: Dehumanism and decolonial entanglements. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

- Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stockton, K. B. (2009). The queer child, or growing sideways in the twentieth century. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Thornton, D. J. (2011). Neuroscience, affect, and the entrepreneurialization of motherhood. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 8(4), 399–424. doi: 10.1080/14791420.2011.610327.

- Tompkins, S. (1962). Affect imagery consciousness. Vol 1: The positive affects. New York, NY: Springer.

- Winnicott, D. W. (2005). Playing and reality. London, UK: Routledge.