ABSTRACT

This research scrutinizes the content, spread, and implications of disinformation in Brazil’s 2018 pre-election period. It focuses specifically on the most widely shared fake news about Lula da Silva and links these with the preexisting polarization and political radicalization, ascertaining the role of context. The research relied on a case study and mixed-methods approach that combined an online data collection of content, spread, propagators, and interactions’ analyses, with in-depth analysis of the meaning of such fake news. The results show that the most successful fake news about Lula capitalized on prior hostility toward him, several originated or were spread by conservative right-wing politicians and mainstream journalists, and that the pro-Lula fake news circulated in smaller networks and had overall less global reach. Facebook and WhatsApp were the main dissemination platforms of these contents.

Introduction

The current connotation of fake news has emerged as part of a disintermediated and fragmented social media environment and in a context of low trust in political institutions (Chadwick, Citation2013; Hermida, Citation2010; Humprecht, Citation2018; Salgado, Citation2018; Van Aelst et al., Citation2017). In addition to social media’s wide use, crisis, political polarization, radicalization, and instability are fertile ground for fake news production and propagation (e.g., Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Del Vicario et al., Citation2016). Such context-dependent conditions encourage viral dissemination (Venturini, Bounegru, Gray, & Rogers, Citation2018) and legitimize a battle of narratives (Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016; Marda & Milan, Citation2018) based on harmful content, hate speech, conspiracy, bullshit, rumors, and lies, often similar to fake news. Lewandowsky et al. (Citation2017) go further linking the reinforcement of radical and extremist political movements with the decline of social capital and trust in science, growing inequality, the rise of political polarization and the increasing importance of social media in media environments, all of which linked to fake news. The decline of trust in professional news media also explains why fake news became so popular so quickly nowadays (McChesney, Citation2012).

Our approach seeks to contribute to the understanding of the Brazilian online disinformation environment, by studying the content, spread, and implications of fake news about Lula da Silva. In the 2018 pre-election period, fake news blended with political propaganda and actual news, which made it often impossible for common citizens to distinguish between facts and lies and to uncover the real intentions behind the spread of fake information. This was particularly important in the case of former President Lula da Silva, because a considerable part of society did not approve of his intention to re-run for the 2018 election. Lula da Silva provoked extreme feelings among the population, either love or hate, and was considered the main target of fake news in Brazil (Bergamasco, Aguiar, & De Campos, Citation2018).

This research is thus guided by an exploratory research question: To what extent and in what ways has political context impacted on the production and distribution of fake news about Lula da Silva? It analyses the fake news items that circulated about Lula da Silva focusing on three dimensions: 1) Content, to check format, sources, topics, and political actors; 2) Spread, to see how content spreads through different platforms and the role of specific propagators; 3) Implications and connections to reality, to examine the links between the actual political context and fake news with the objective of further understanding the emergence and the distribution of such falsehoods, as well their impact on politics.

This approach differentiates from extant research more focused on audiences (e.g., Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Guess, Lyons, Nyhan, & Reifler, Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018; Pennycook, Cannon, & Rand, Citation2018), or on the technological affordances, including algorithms and bots (e.g., Howard, Bolsover, & Bradshaw, Citation2017; Spohr, Citation2017), and focuses instead primarily on the role of context (e.g., Humprecht, Citation2018; Jankowski, Citation2018), by following a case study approach that examines the links between fake news on Lula da Silva and Brazil’s political context.

The article is divided in four main sections, plus this Introduction. It starts with the theoretical underpinning of our approach. Then, the next section explains the research design and methodological options. The Results section explains the further details of the analysis and its main results, which are finally discussed at the light of the “context-matters” notion.

Fake news in politics

Fake news is a multifaceted and dynamic phenomenon; it develops according to technology and globalization levels, country-specific, political, social, and cultural factors (e.g., Humprecht, Citation2018). Extant literature places it within the wider context of disinformation that encompasses “fake news, rumors, deliberately factually incorrect information, politically slanted information, and hyperpartisan news” (Tucker at al., Citation2018: 2). Fake news stories often display the following components: 1) news appearance, 2) fictitious source, 3) viral reach, d) intentionality, 4) verifiable falsehood and 5) potential to generate deception (e.g., Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Tandoc, Lim, & Ling, Citation2018).

Online deceptive content has been gaining ground in recent years, partly due to the growth of far-right populism and other political extremisms and to the growing use of social media (Araújo & Prior, Citation2021; Baldwin-Philippi, Citation2019; Bimber, Citation2015; Ibsen, Citation2019; Salgado, Citation2018). Both the structure and use of social media have amplified hyper-partisanship, confrontation, antagonism, and social divisionism by propelling the creation of like-minded online communities, which are then highly fragmented among each other due to their different ideologies, ideas, beliefs, agendas, and actors. Polarization is particularly important as it refers to a division into contrasting groups or opinions (the us versus them), which has a relational nature and an instrumental political use (McCoy, Rahman, & Somer, Citation2018). It is, furthermore, a continuous process that strengthens dispute, division, conflict, and social intolerance (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Citation2018).

Studies have seek to understand how partisan and affective political polarization relates to online environments, particularly those in which the circulation and wide sharing of deceptive content is of concern (e.g., Iyengar, Sood, & Lelkes, Citation2012; Narayanan, Barash, Kollanyi, Neudert, & Howard, Citation2018; Rojas & Valenzuela, Citation2019), and found that rumors and falsehoods tend to spread faster in polarized online networks (e.g., Barberá, Jost, Nagler, Tucker, & Bonneau, Citation2015; Friggeri, Adamic, Eakles, & Cheng, Citation2014; Törnberg, Citation2018). Moreover, right-wing conservatives have been found more likely to share or engage in fake news stories (e.g., Grinberg, Joseph, Friedland, Swire-Thompson, & Lazer, Citation2019) and “sharing fake news is often linked to self-presentation and reinforcement of group identity” (Marwick, Citation2018: 477). Some adverse consequences include sowing division among different social and cultural groups, or distracting and confusing, to chip away at the minimal shared understandings required for political discussion (Chadwick & Vaccari, Citation2019: 7). The specific context does seem to hold an important role, not only in the propagation potential of messages produced and distributed online, but also in the acceptance or resistance to fake news.

Fake news stories can be seen as products of today’s complex political communication processes and placed within a specific political context (e.g., Salgado, Citation2019) that mediates their production, spread and endorsement. Moreover, the spread of fake news is often related to specific political goals (e.g., obtain leverage over opponents to win an election, etc.) and sometimes entails cherry-picking truthful aspects of reality and mixing them with falsehoods (e.g., Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Pyrhönen & Bauvois, Citation2020) to amplify impact. The incorporation of fake news in political strategies also aims to take advantage of preexisting climates of opinion, when they are seen as accommodative of a given agenda and bias, to boost their potential for online virality through cross-platform spread. In this sense, the success of fake news is largely dependent on the political environment.

The Brazilian context is particularly prolific for research about these issues. Brazil has experienced several political crises in its recent history. The series of massive popular demonstrations that happened throughout Brazil in 2013, which became known as “June Journeys” (e.g., Mendonça & Bustamante, Citation2020; Santos, Citation2019; Singer, Citation2014), instigated the demonstration of feelings of dissatisfaction among the population and against the institutions of representative democracy. This paved the way for the emergence of groups calling for the denial of party politics and seeking a return to military dictatorship. This political upheaval was reflected in the 2014 election, in which Dilma Rousseff (PT–Workers Party) won by just 3,28%. The growing climate of antipathy toward the PT, called “antipetism” (Davis & Straubhaar, Citation2020), escalated when Rousseff’s opponents questioned the 2014 electoral results.“Antipetism” is also key in understanding Rousseff’s impeachment and Jair Bolsonaro’s victory in the 2018 presidential election (a politician, who retired from the military and ran for office in the 2018 election with the support of the right-wing, conservative political party Social Liberal Party, PSL). Such political instability worsened distrust and boosted the use of social media to spread rumors and fake news with the purpose of influencing the already unstable climates of opinion.

Research has found that crises of trust in democracy tend to amplify adherence to conspiracy theories (e.g., Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, Citation2017; Hendricks & Vestergaard, Citation2019). Furthermore, the more competitive the election, the more influence the flows of information will potentially have on voters, including those that are fake news, particularly if we take into account that they are often shared among users who perceive them as true news, either because they trust the sender or because the content resembles a real news story, or both. For the purpose of this research, we have thus collected and analyzed fake news that did resemble actual news (see also Al-Rawi, Citation2019; Tandoc et al., Citation2018), that distorted political facts, that were verified and deemed false by fact-checking endeavors, and that were spread primarily online.

Methodological approach

Empirical research addressing context can contribute to the further understanding of the underlying motivations of spreading fake news and their actual impact and thus to cumulative knowledge on how this phenomenon unfolds in different cases. Our exploratory approach examines the main characteristics of fake news about Lula da Silva in an electoral context. The working hypothesis is that fake news disseminated amid climates of hostile and polarized opinions and that capitalize on actual facts by distorting them are spread quickly and broadly through diverse online platforms.

Our case study is based on a mixed-methods approach that includes web data collection and analysis (Bounegru, Gray, Venturini, & Mauri, Citation2017; Rogers, Citation2017) and qualitative content analysis, which is used to examine and describe meaning in a systematic manner (Schreier, Citation2012; Krippendorff, Citation2019). As Schreier explains, it allows that the researcher “engages in some degree of interpretation to arrive at the meaning of the data” (Schreier, Citation2012: 2). The data collection comprised the archives of fact-checking initiatives and web browsing on the relevant websites and social media platforms: we traced fake news about Lula da Silva that circulated during the pre-campaign period and then identified the profiles, accounts, pages, and platforms associated to those occurrences. The research steps are described next.

We first probed the Brazilian online environment to find occurrences (i.e., fake news about Lula da Silva) and collect their full content. Through this initial procedure, we found that fact-checking initiatives (a comprehensive list is provided in the Appendix) were important secondary data sources, as they kept updated records of all occurrences, which has allowed us to check the content and format of all fake news about Lula da Silva. Other relevant websites (please see the Appendix) were also used as data sources, as they played a role in producing and distributing these fake news items. In Lula da Silva’s case, most fake news circulated on Facebook, WhatsApp and, slightly less, on Twitter. We collected and mapped the most widely shared fake news through these platforms from January 1 to July 31, 2018, which corresponds to an extended pre-campaign period.

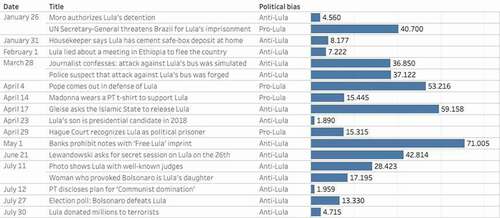

A dataset initially composed of 53 units included all items that had been considered fake news by fact-checking initiatives. The months with the highest volume of fake news in circulation about former President Lula da Silva were April and July with 16 and 13 items, respectively. In April, Lula da Silva was arrested on charges of corruption and in July a series of legal events that would determine whether Lula could be a presidential candidate in the 2018 election took place. Among the items that had been proven untrue, we then selected the ones that had achieved wider circulation and reach through social media. To guarantee consistency in the sample in its connection to the meaning of “fake news” in our approach (i.e., similarity to actual news stories), we excluded all content that could be confused with chain messages, satires and memes (ten cases); stories that were checked by one fact-checking website only (twenty-one cases); and stories that, even if checked more than once, had negligible reach and triggered rather inconsequential levels of interaction among users (four cases). Such conditions (verifiability, virality, similarity to actual news) provide greater likelihood that the false content would become “fact” and “information” in the voters’ opinion. Virality here means the widespread of content in online environments (Berger & Milkman, Citation2012; Nahon & Hemsley, 2013). The final sample for in-depth analysis was composed of eighteen units of analysis (N = 18) representing 459.096 digital interactions. provides a summary.

Table 1. Final sample

The repercussions triggered by each of these items were also taken into account. Further web searches allowed the detection of the source and the main propagators in each of these eighteen fake news items. Online searches using excerpts of the fake news’s original content (retrieved from fact-checking websites) were performed on Facebook, Twitter, and Google. On WhatsApp, because it is a closed messenger with end-to-end encryption, the search was done through secondary sources as fact-checking initiatives and other (open) social media platforms when there was evidence disclosing the fake news’s actual trajectory. This means that WhatsApp specific data was considered only when secondary sources (e.g., fact-checking websites) confirmed its relevance in the spread of a given fake news item. Although our analysis did not identify specific propagators within WhatsApp (closed platform), it did manage to collect the content of the items spread through this app.

The social monitoring platform CrowdTangle extension was used to check how many social media shares each item had triggered, i.e., which pages or accounts had shared the specific link. This allowed the identification of key propagators as well as the further data collection on relevant websites that acted as producers and distributors of the fake news content. Iramuteq software was then used for automated textual analysis that was combined with in-depth (human) content analysis, focusing on the three main dimensions of the analysis (derived from the research objectives) and ensuing six variables ().

Table 2. Overview of the analysis: dimensions and variables

The first dimension dealt with the fake news’ content to assesses the resemblance of fake news to regular news formats and the prevalence of political polarization. The second dimension dealt with spread (online virality) to investigate the trajectory of each fake news item and track the role of propagators (profiles or pages). It is important to note that information on specific individual users-propagators was disclosed only in the case of public profiles of public figures, the remaining profiles were subjected to de-identification procedures (pseudonymization). Because it was impossible to collect all data from all users involved, the study focused on the four main propagators only and on the interaction among users connected to them, levels of engagement, and overall reach. The interaction/engagement rateFootnote1 calculations were thus based on the four main propagators for each fake news item. The third dimension of analysis examined the fake news’s connection to reality both regarding its links to real facts (e.g., distortion vs. fabrication) and its repercussions on society.

These three dimensions uphold the empirical analysis of the links between the production and spread of fake news and the preexisting political and media contexts, to analyze whether/how context matters. By assessing the similarity to real news and the prevalence of polarization in content, our approach checks whether/how the content of fake news relates to specific features of context. By checking the propagation channels, our approach acknowledges the online environment’s structure and studies how the content spreads through it. By examining if the fake news story had a meaningful impact on offline politics, it stresses the interconnection between the disinformation strategies and the political context. Finally, our approach establishes whether there were clear connections between offline reality (facts and preexistent climates of opinion) and fake news.

Results

Content

The first dimension focused on the similarity of fake news items to actual news formats and on the prevalence of polarization, to ascertain the link between fake news and political context. Polarization was assessed through the political bias, the specific topic and actors mentioned in the fake news item, the existence of a clear divide, and the use of harsh, pejorative language. The political bias provides important information about the sender’s ideological spectrum, which together with content often allows the inference of the motivation behind the production and spread of a given fake news item. Following Allcott and Gentzkow (Citation2017), we coded the fake news items’ content between favorable (pro-Lula) and unfavorable (anti-Lula). Anti-Lula refers to the content whose main objective was to harm Lula da Silva’s public image and reversely pro-Lula content aimed to improve his reputation, promote his 2018 presidential candidacy, and defend him from accusations. Most cases were clearly anti-Lula (fourteen in total) and only four were pro-Lula ().

The anti-Lula posts had at least 13.125.528 interactions (likes and other emotional reactions, comments, and shares) and were mostly distributed in conservative, right-wing networks, which comprised approximately 13.072.796 followers (100,40% engagement rate). The pro-Lula posts received 68.661 interactions from predominantly leftist networks involving 223.546 followers (30,71% engagement rate). These numbers indicate that the interaction motivated by anti-Lula fake news was 190 times higher than the interaction caused by pro-Lula items. In addition, untruths put into circulation that could benefit the former president circulated through a network that was fifty-eight times smaller. Interestingly, only two fake news items, both pro-Lula, were shared simultaneously by right and left networks, with 56.015 interactions that spread through the pages and profiles of 290.008 users/followers (19,31% engagement rate).

The lexical analysis assessed the prevalence of pejorative expressions and incitements to intolerance against the political opponents. For this purpose, we used Iramuteq software to analyze fake news items and posts by the main propagators. The analysis showed that of 374 grammatical forms, many were adjectives (98). Conspiracies, such as the “communist threat,” were found in fourteen of the eighteen cases under analysis. The lexical analysis also showed that there were several cases with swear words and that the terms “national,” “terrorist,” “PT,” “communist” and “political” have appeared the most. For example, in the item with the second highest interaction levels, Gleisi Hoffmann (politician, chief of staff in Rousseff’s presidency) was called “communist” and the Arab population was considered “terrorist.” In the case of the woman who shouted at Bolsonaro and was later introduced as Lula’s daughter, the fake news item said specifically: “Drunk Lula’s daughter cursing Bolsonaro. The despair of the PT has begun.” In a fake news item related to the potential victory of Bolsonaro in all states, one of its main propagators posted the following comment: “The left will be extinguished. Swallow your cry, communists.”

By focusing on format features and sources of information, the analysis also examined how the fake news item emulated a real news story. These two elements represent forms of ascribing credibility and legitimacy to an untrue fact. We found four different types of format, with twenty occurrences, because two of the cases had two predominant formats and not just one. The most common, with seven occurrences, was the news article type, followed by five items that consisted mainly of photos, four items that included texts, images and videos, and four items with a short text format. All of these followed patterns of journalistic production. When the fake news emulated a real news article, it included headlines, journalistic jargon, and sources of information. In addition to titles that simulated real news headlines, there was also the insertion of “Breaking News,” “Scoop,” or “Exclusive” and photos to convey the impression that it was indeed fact-related. The use of third-person sentences, direct and indirect quotes from sources of information, or even “off-the-record” mentions, aim at embedding the credibility of journalism’s formats into the fake news items, and some of these elements were also found in posts. Publishing photos intends to provide some additional evidence of the rumors and untruths put into circulation.

Actual sources of information were included in eleven of these fake news items and in four of them reputable mainstream news media were used to increase the credibility of the alleged “news report.” In these cases, the French newspaper Le Monde, and the Brazilian news outlets Globo and Antagonista were cited as source of the information. Globo belongs to one of the most important news media groups in Brazil and Antagonista is a partisan news media (Levendusky, Citation2013) known for its often-polarized treatment of information and bias against Lula da Silva and PT. Journalists were presented as the news source in other cases; the Brazilian Central Bank, the United Nations, and a polling company (Paraná Pesquisa) were also cited as sources to support these “news reports.”

Spread

This dimension focused on the online spread and virality (i.e., the rapid and wide circulation of a message from one online user to another; see e.g. Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, Citation2018), namely the reach and distribution through different platforms, the main propagators (the most influential boosters), as well as the specific URLs. If we look at the circulation of fake news as a feature of the political context that has been accentuated by the digital era (Marda & Milan, Citation2018), it becomes essential to examine the online spread and reach. Törnberg (Citation2018) has also demonstrated a synergetic effect between virality and polarization.

We first determined the platform in which the fake news item originated and then identified all the secondary environments through which it had circulated. Such procedure, however, does not allow definite conclusions about the origin, because there were cases in which it was possible to detect more than one primary source. These data were collected through online searches, which included fact-checking derived data, Facebook, and Twitter. Even though WhatsApp prevents data collection by external means (it is protected with end-to-end encryption), it was included in the distribution analysis whenever the fact-checking initiatives signaled that a fake news item had been spread through it, but we did not measure reach or interaction directly through WhatsApp. Despite these constraints, the inclusion of WhatsApp in the study was considered important, due to its large number of users and to the role that it has in the spread of fake news.

The analysis has also shown that the platform that has contributed the most to spread fake news was Facebook; it was the primary route in 60% and the secondary in 22% of the cases. WhatsApp followed, being primary in 38% and secondary in 33% of the cases. Twitter was the primary source in 5% of the cases and secondary in 38%. Facebook and WhatsApp were thus primordial in spreading fake news about Lula da Silva. The explanation for this lies partly in the fact that these social media platforms have the most penetration in Brazil, but the specific features of these platforms should also play a role, as Facebook allows posting more information and therefore more details, and WhatsApp is a truly interpersonal platform with wide acceptance in Brazil. The results also revealed that the interactions around anti-Lula’s fake news occurred in a network with more than thirteen million users and were 190 times higher than pro-Lula interactions.

The analysis identified 59 profiles, pages, or groups on Facebook that played the roles of primary or secondary propagators of fake news about Lula. Eighteen of these propagators were anonymous users or influential journalists or politicians. The remaining 41 main propagators were Facebook pages or groups linked to supporters of different politicians, online movements, ideological groups, and hoax sites.

Pro-Lula fake news items (8.47% of the sample) were mostly propagated by personal profiles. The majority of anti-Lula fake news (91.52%) were propagated by a conservative right-wing network that also praised the military regime and supported Jair Bolsonaro. The fake news item with the highest spread and audience () was initially shared by the movement behind the mobilization for the impeachment of former President Rousseff, the “Movimento Brasil Livre” (MBL–Free Brazil Movement is a conservative movement, often described as the “Brazilian Tea Party”). In this case, MBL received 12.000 shares, 17.000 likes and other emotional reactions, and 1900 comments on Facebook. When it was shared through other platforms and websites, such as “Eu vivo no Brasil,” “Bolsonéas,” or “Movimento Força Brasileira,” it received at least 37.122 more interactions.

The hoax website “Pensa Brasil” was also a prominent propagator of fake news about Lula da Silva. The content posted by “Pensa Brasil” on its Facebook page was widely shared by other websites and Facebook pages, such as “República de Curitiba,” “Movimento Força Brasileira,” or “Lula de novo, NÃO,” and was disseminated through a network of almost one million followers (981.184), motivating nearly 37.000 interactions.

The analysis also showed that Facebook profiles by individual users linked to three different accounts were key in disseminating anti-Lula fake news. In one case, three fake news items were produced and initially disseminated by the same user, a supporter of the 1964 military coup in Brazil. This profile had at least 52.736 followers and the spread of Lula da Silva’s fake news stories motivated nearly 1.201.600 interactions. A single post had one of the highest engagement rates, 34.000 shares, 5500 likes, and 1200 comments.

Another important propagator was a website updated by the journalist and political columnist Augusto Nunes, who claimed that Lula da Silva had fabricated a meeting in Ethiopia to be able to flee the country. This content was spread through a network composed of at least 2.045.673 followers. Another case, in which it was claimed that the PT president had hired terrorists to release Lula, was originally propagated by a right-wing digital influencer’s Facebook page and was spread through 1.096.506 followers, motivating around 32.000 shares, 12.000 likes and 3.900 comments.

Influential users are extremely important in these dissemination processes, either as producers or simply as propagators, they confer visibility and often also legitimacy to the fake content that is being conveyed. Therefore, we also checked the participation of influential users throughout the dissemination processes. Almost half of the cases that we have analyzed (six) had at least one public figure disseminating the fake news. The intervention of public figures in these cases, not only popularized the content, but it also legitimized it. In the cases under analysis, we found well-known journalists, politicians, and digital influencers. Furthermore, the dissemination of fake content by more than one central propagator increased significantly the reach of these fake news. This happened in the case of the anti-Lula fake news item that stated that PT officials had hired terrorists to help Lula da Silva escape from prison, which was endorsed by Brazilian politicians, such as Ana Amélia, Major Olímpio, Ronaldo Caiado, Alexandre Frota and the youtuber and MBL’s activist Arthur do Val (known as “Mamãe Falei”), who was elected state representative in São Paulo in 2018. The same happened in some pro-Lula fake news items, such as those stating that the UN was preparing sanctions to Brazil due to Lula da Silva’s imprisonment and that Pope Francis was supportive of Lula, which were shared by prominent PT party members, such as Gleisi Hoffmann and federal deputy Marco Maia.

Biased information websites also played a significant role in disseminating these items: they were central in seven of the cases. The analysis of their URLs revealed that they motivated around 833.728 online interactions (727.172 on Facebook) and circulated in networks of at least 15.095.897 users. Two of the fake news items originated on a website called “Diário do Brasil” that clearly simulates a news portal. Other important means of dissemination of fake news were the hoax websites “O Detective” and “Pensa Brasil.” The latter resembles a news media outlet, but does not include any names of its editorial board and journalists. There are also examples of websites that position themselves as “alternative news media” and emulate actual news media outlets, but that are clearly aligned ideologically with right-wing movements, such as “Diário Nacional,” which is linked to MBL (Free Brazil Movement) and “Jornal do País.” In addition to these, an actual mainstream media, newsmagazine Veja, also appeared in the analysis as involved (through a political column by one of its journalists) in the spread of fake news about Lula da Silva.

We were also interested in checking whether these fake news items had caused a noticeable impact on offline politics, namely if any political, social or legal decision-making had been carried out as result of the acceptance or as repercussion of these untrue reports. Four cases provoked direct political impacts (in the sense of concrete actions). In the remaining fourteen cases, other repercussions, related to an indirect impact, were also observed, such as the rumor that banks would not accept banknotes with the “Free Lula” imprint (71.005 interactions on Facebook). Direct consequences on politics included the formal investigations by the Attorney General’s Office due to rumors of a violation of the National Security Law and Lula da Silva’s release from prison on a Sunday (rumors and images of the judge’s close relation with Lula were widely spread and had an engagement rate of 45.37%). The episode that originated from a rumor that Lula da Silva intended to flee the country caused the seizure of his passport and he was prevented from participating in a FAO-UN (Food and Agriculture Organization-United Nations) meeting in Ethiopia, despite this having been previously authorized by the Justice Department (please see a summary of the main events in ).

Table 3. Main events

Connection to reality

This dimension examined the degree of closeness between the fake news’s content and actual reality, especially those issues and events that are on the public agenda. We expect that fake news deriving directly from reality or that are closely inspired by actual facts will be more convincing and will cause strong engagement.

The analysis has shown that most fake news items (thirteen: nine anti-Lula and four pro-Lula) were closely inspired by real political events/facts. One of the most influential after Lula’s arrest claimed that PT president Gleisi Hoffmann had called terrorists from the Islamic State to release Lula da Silva from prison. This content, which circulated among 1.096.506 followers and motivated nearly 60.000 interactions (5.40% engagement rate), was a direct reaction to a legitimate video recorded by Hoffmann herself for Al Jazeera television channel in which she stated that Lula da Silva was victim of political persecution.

All of the four pro-Lula fake news items were ingrained in real events. For example, the actual seizure of Lula da Silva’s passport by the authorities motivated two related fake news: one revealing that the UN Secretary-General had threatened Brazil with sanctions, which triggered a considerably high engagement rate (77.18%); and the report that Lula da Silva was planning to attend the UN event to flee to Ethiopia (Ethiopia does not have an extradition treaty in force with Brazil), which circulated through 2.045.673 users and had at least 7.222 interactions (0.35% engagement rate).

The fake news items without connections to actual political events and facts were all anti-Lula and were related to prior rumors and conspiracy theories. These were aimed at intensifying the climate of hostility against Lula da Silva and PT: in one case, a housekeeper had said that Lula da Silva had a cement safe-deposit box larger than a swimming pool; another was a warning against “PT’s domination plan”; and in another case, Lula da Silva had donated $25 million to terrorists. The remaining two cases addressed the forthcoming 2018 election: Lula had launched his son “Lulinha” as presidential candidate; and opinion polls were predicting that Bolsonaro would win against Lula in all twenty-seven states.

Finally, we were interested in examining prior climates of opinion and their possible connection to these fake news stories about Lula da Silva, more specifically, whether fake news had emerged as a reflection of previously shared opinions, suspicions, and speculations. This is also believed to amplify the acceptance and reach of fake news, as it acts as reinforcement of ideas and beliefs (for additional information on reinforcement in political campaigns see, e.g., Lazarsfeld et al., Citation1948; Johnson-Cartee and Copeland, Citation1997), as a confirmation of information that had already been disseminated and assimilated. We collected and analyzed further data focused on preexisting opinions and rumors pro and anti-Lula to check whether any of these had been used in the fake news items. There was the construction of a narrative based on preexisting speculations in six of the eighteen fake news items ().

Table 4. Prior climates of opinion

Discussion

The expression fake news has been often used in a broader sense to refer to everything that is not completely true (e.g., Farkas & Schou, Citation2018), but we do acknowledge the usefulness of operationalizing it as a concept when studying disinformation. For the purpose of empirical research, we have delimited the concept to refer to cases of “news” that were intentionally fabricated, produced to look like real news (although verified and considered false), and that were spread through online platforms. We thus refer to political content disseminated as news, and not as political satire or opinion.

To add to knowledge about the global phenomena of politically oriented fake news (Lazer et al., Citation2018), our approach focused on fake news about Lula da Silva and explored the role that context plays in their production and propagation. We analyzed the content, spread, and implications of fake news to detect the actors behind their production, the characteristics of their content, their propagation trajectories throughout the media environments, and their impact on offline politics. Such approach demonstrated the impact of a polarized context (with the active participation of elected representatives and of mainstream journalists) in fostering climates conducive to the spread of fake news, some of which resulting from speculations and conspiracies already present in online conversations and serving purposes of political manipulation. The 2018 presidential election has further escalated a context of disinformation and misinformation, due to the systematic use of social media by different types of actors (including mainstream politicians and journalists) to spread fake news. Fake news stemmed from existing cycles of mis/disinformation in politics that were used in strategies to induce certain climates of opinion with the goals of influencing political decisions, and even delegitimizing and overthrowing opponents.

The preexisting climate of hostility and strong political polarization has influenced not only the volume of messages about Lula da Silva (many of these focused on his credibility and character), but also the actors that initiated those fake news stories: they were clearly anti or pro-Lula. The data analysis showed that the most popular fake news items circulating during the pre-election period were anti-Lula, with 13.125.528 interactions and 13.072.796 followers, versus 68.661 interactions and 223.546 followers in the pro-Lula’s items. This suggests that conservative online networks are larger and/or more engaged online, which impacts on the fake news stories that thrive more easily. In a hybrid media system (Chadwick, Citation2013), with both news media coverage and the use of social media by journalists, this escalated the climate of political tension and discredit of PT and the left, which culminated in the electoral victory of the right-wing populist candidate Jair Bolsonaro.

The analysis of fake news also showed that the resort to journalistic language and procedures is common even in the case of messages conveyed mainly through images and videos (the news-like dimension of analysis). The similarity of fake news with actual news articles is intended to legitimize the content through the credibility of journalistic work and makes false information more believable in the eyes of the public, thus gaining wider visibility and repercussion. Additionally, the strategy to build fake news stories from preexisting concrete true facts and events is aimed at coating falsehoods with a hint of reality, in order to activate reinforcement, which tends to enhance influence. We observed this strategy in some fake news, which might explain – at least in part – their online virality. In fact, all of these features of fake news contribute to explain their spread and virality . And context is key: in Brazil’s case not only there was already a climate of hostility against PT and Lula da Silva, but also Lula was one of the most debated “topics” of the pre-election period, due to his intention to re-run as presidential candidate in the 2018 election, despite the allegations of corruption and his arrest. Fake news items have emerged and blended in a specific context of affective polarization (e.g., Iyengar et al., Citation2012; Suhay, Bello-Pardo, & Maurer, Citation2018), in which sentiments such as fear, repulsion, hatred, anger, or idolatry were exacerbated, thus facilitating propagation by users. Fake news stories about Lula da Silva have functioned as meaningful syntheses incorporating preexisting narratives, which were linked to polarization and to the influential, conservative media ecosystem (Garrett, Long, & Jeong, Citation2019).

The data analysis revealed that Lula’s opponents were more successful in their use of fake news to influence the election campaign and Lula’s public credibility. In terms of spread and impact on politics, the most successful fake news items that circulated during the pre-election period were anti-Lula. These were initiated by conservative right-wing individuals and groups that extolled the virtues of the military (capitalizing on Brazil’s lack of security issue) and praised Judge Moro who ruled for Lula da Silva’s arrest before the presidential election. Internet users who supported these views formed a network of at least thirteen millions. Ordinary citizens and anonymity also play an important role; in this case, anonymous profiles were true engines for the spread of fake news about Lula da Silva. And when public figures endorsed a specific fake news, they gave it both credibility and visibility.

Confirming extant research that points to the importance of the message source in the propagation of fake news (e.g., Buchanan & Benson, Citation2019), our approach demonstrated how some well-known journalists, who are followed by readers and by other media professionals, sometimes took themselves the role of propagating agents, which very likely explains the higher impact of anti-Lula fake news items, as they were propagated in larger and more powerful networks than pro-Lula fake news items. This is all the more important, as previous studies have also shown how some influential news media outlets have a clear partisan, anti-left, approach to politics in Brazil (e.g., Albuquerque, Citation2016) and that the relation between press and politics in Brazil does bear an important influence on political action, as it happened in Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016 (Albuquerque, Citation2017). Such finding seems to challenge research that deals with fake news as naturally opposed to news media (e.g., Al-Rawi, Citation2019) and support the approaches that include journalists and journalism in the equation (e.g., Curran and Seaton, Citation2010; van Dijck & Poell, Citation2013).

These fake news items emerged in a preexisting context of disinformation and could be seen as tactics to radicalize and polarize the political environment further, especially when endorsed by prominent public figures, including journalists and politicians that strategically spread the fake news content to mobilize supporters for their side. This case also shows how disinformation can become misinformation if it is picked up and spread by individual users without knowledge of whether the content is fake, where it originated, and with what purpose. As in other settings (see e.g., Bennett & Livingston, Citation2018; Lewis & Marwick, Citation2017), disinformation and misinformation became more and more intertwined.

The research results have emphasized the links between fake news and context, which appears as influential in both their production and propagation. An approach such as this adds to knowledge on the interplay between politics and media and between disinformation and polarization in the Brazilian context and informs the state-of-the-art about how context shapes these developments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This metric allows the calculation of the probability that a given content has of inducing interaction when it appears on the user’s timeline. The calculation was done through a digital marketing formula (interactions: followersX100), and then compared with the Facebook Engagement Rate Calculator tool (The Online Advertising Guide). Available at: https://theonlineadvertisingguide.com/ad-calculators / facebook-engagement-rate-calculator/.

References

- Albuquerque, A. (2016). Voters against public opinion: The press and democracy in Brazil and South Africa. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3042–3061.

- Albuquerque, A. (2017). Protecting democracy or conspiring against it? Media and politics in Latin America: A glimpse from Brazil. Journalism, 20(7), 906–923. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917738376

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Al-Rawi, A. (2019). Gatekeeping Fake News Discourses on Mainstream Media Versus Social Media. Social Science Computer Review, 37(6): 687–704

- Araújo, B., & Prior, H. (2021). Framing political populism: The role of media in framing the election of Jair Bolsonaro. Journalism Practice, 15(2), 226–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1709881

- Baldwin-Philippi, J. (2019). The technological performance of populism. New Media & Society, 2(2), 376–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818797591

- Barberá, P., Jost, J., Nagler, J., Tucker, J., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26(10), 1531–1542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615594620

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

- Bergamasco, D., Aguiar, I., & De Campos, J. P. (2018). Lula, Temer e Moro são os maiores alvos de notícias falsas | VEJA.com. Retrieved January 12, 2018, from Revista Veja website: https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/ranking-alvos-vitimas-noticias-falsas-fake-news-politica-brasil/

- Berger, J., & Milkman, K. (2012). What makes online content viral? Strategic Direction, 28(8), sd.2012.05628haa.014. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/sd.2012.05628haa.014

- Bimber, B. (2015). The internet and political transformation: Populism, community and accelerated pluralism. Polity, 31(n. 1), 133–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3235370

- Bounegru, L., Gray, J., Venturini, T., & Mauri, M. (2017). A field to guide to fake news - A collection of recipes for those who love to cook with digital methods. Retrieved from http://fakenews.publicdatalab.org

- Buchanan, T., & Benson, V. (2019). Spreading disinformation on facebook: Do trust in message source, risk propensity, or personality affect the organic reach of “fake news”? Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511988865. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119888654

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system. Politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chadwick, A., & Vaccari, C. (2019). News sharing on UK social media: Misinformation, disinformation, and correction. Retrieved from <https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/37720Version:>.

- Curran, J., Seaton, J. (2010). Power Without Responsibility: Press, Broadcasting and the Internet in Britain. London: Routledge

- Davis, S., & Straubhaar, J. (2020). Producing antipetismo: Media activism and the rise of the radical, nationalist right in contemporary Brazil. International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 82–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519880731

- Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., … Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113

- Farkas, J., Schou, J. (2018). Fake News as a Floating Signifier: Hegemony, Antagonism, and the Politics of Falsehood. Javnost - The Public, 25(3): 298–314

- Friggeri, A., Adamic, L., Eakles, D., & Cheng, J. (2014). Rumor Cascades. Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media Adrien. Ann Harbor, Michigan, USA.

- Garrett, R., Long, J. A., & Jeong, M. S. (2019). From partisan media to misperception: Affective polarization as mediator. Journal of Communication, 69(5), 490–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz028

- Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

- Guess, A., Lyons, B., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Avoiding the echo chamber about echo chambers: Why selective exposure to like-minded political news is less prevalent than you think. Retrieved from https://kf-site-production.s3.amazonaws.com/media_elements/files/000/000/133/original/Topos_KF_White-Paper_Nyhan_V1.pdf

- Hendricks, V., Vestergaard, M., (2019). Reality Lost: Markets of Attention, Misinformation, and Manipulation. Cham: Springer

- Hermida, A. (2010). Twittering the news: The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice, 4(3), 297–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512781003640703

- Howard, P. N., Bolsover, G., & Bradshaw, S. (March, 2017). Junk news and bots during the U.S. Election: What were michigan voters sharing over twitter? COMPROP DATA MEMO. Oxford, UK. 1–5.

- Humprecht, E. (2018). Where fake news flourishes: A comparison across four Western democracies. Information, Communication & Society, 22(13): 1973-1988. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1474241

- Ibsen, M. F. (2019). The populist conjuncture: Legitimation crisis in the age of globalized capitalism. Political Studies, 67(3), 795–811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718810311

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Jankowski, N. W. (2018). Researching fake news: A selective examination of empirical studies. Javnost - The Public, 25(1–2), 248–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1418964

- Johnson-Cartee, K., Copeland, G. (1997). Inside Political Campaigns: Theory and Practice. Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger

- Khaldarova, I., & Pantti, M. (2016). Fake news: The narrative battle over the Ukrainian conflict. Journalism Practice, 10(7), 891–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1163237

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Los Angeles: Sage. 4th edition

- Lazarsfeld, P., Berelson, B., Gaudet, H. (1948). The People's Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. New York: Columbia University Press

- Lazer, D., Baum, M., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A., Greenhill, K., Menczer, F., … Zittrain, J. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359Issue (6380), 1094–1096. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

- Levendusky, M. (2013). Why do partisan media polarize viewers? American Journal of Political Science, 57(3): 611–623

- Levitsky, S., Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Crown

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U., Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the 'Post-Truth' Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4): 353–369

- Lewis, A., & Marwick, A. (2017). “Taking the red pill: Ideological motivations for spreading online disinformation.” Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem, U. of Pennsylvania Annenberg School for Communication, PA, December 15–16.

- Marda, V., & Milan, S. (2018). Window of the crowd: Multistakeholder perspectives on the fake news debate. Retrieved from http://compact-media.eu/wisdom-of-the-crowd-multistakeholder-perspective-on-the-fake-news-debate/

- Marwick, A. (2018). Why do people share fake news? A sociotechnical model of media effects. Georgetown Law Technology Review, Vol. 2.2, 474–512

- McChesney, R. W. (2012). Farewell to journalism? Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 614–626. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.683273

- McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: Common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 16–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218759576

- Mendonça, R. F., & Bustamante, M. (2020). Back to the future: Changing repertoire in contemporary protests. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 39(5), 629–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13087

- Narayanan, V., Barash, V., Kollanyi, B., Neudert, L.-M., & Howard, P. N. (2018). Polarization, Partisanship and Junk News Consumption over Social Media in the US. COMPROP DATA MEMO, Oxford, UK.

- Nelson, J. L., & Taneja, H. (2018). The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3720–3737. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818758715

- Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 1–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

- Pyrhönen, N., & Bauvois, G. (2020). Conspiracies beyond fake news. Produsing reinformation on presidential elections in the transnational hybrid media system. Sociological Inquiry, 90(4), 705–731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12339

- Rogers, R. (2017). Foundation of digital methods: Query design. In The datafied society: Studying culture through data. Amsterdam University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.5117/9789462981362

- Rojas, H., & Valenzuela, S. (2019). A call to contextualize public opinion-based research in political communication. Political Communication, 36(4), 652–659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1670897

- Salgado, S. (2018) Online media impact on politics. Views on post-truth politics and post-postmodernism. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 14(3):317–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.14.3.317_1x

- Salgado, S. (2019). Never say never … Or the value of context in political communication research. Political Communication, 36(4), 671–675. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1670902

- Santos, N. (2019). The reconfiguration of the communication environment: Twitter in the 2013 Brazilian protests. [Thesis] Université Paris II- Panthéon-Assas École.

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Singer, A. V. (2014). Rebellion in Brazil. New Left Review, 85, 19–37.

- Spohr, D. (2017). Fake news and ideological polarization: Filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Business Information Review, 34(3), 150–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382117722446

- Suhay, E., Bello-Pardo, E., & Maurer, B. (2018). B. The polarizing effects of online partisan criticism: Evidence from two experiments. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 95–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740697

- Tandoc, E. C., Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “Fake News.” Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

- Törnberg, P. (2018). Echo chambers and viral misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion. PLOS ONE, 13(n. 9), e0203958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203958

- Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., Nyhan, B. (2018). Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3144139

- Van Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., De Vreese, C., Matthes, J., … Stanyer, J. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1), 3–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551

- van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding social media logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v1i1.70

- Venturini, T., Bounegru, L., Gray, J., & Rogers, R. (2018). A reality check(-list) for digital methods. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4195–4217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769236

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 1151(6380), 1146–1151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Appendix

List of data sources

Fact-checking:

Aos Fatos

Lupa

Portal G1 (É ou Não É?)

Estadão Verifica

Buzzfeed

Boatos.Org

e-Farsas

Veja (Me engana que eu posto)

O Globo

UOL

El País

O Tempo

Piauí

A Tribuna

Correio Braziliense

O Povo

Information websites

Jornal do País

O Diário Nacional

Pensa Brasil

Diário do Brasil

O Detetive

Blog Augusto Nunes (Veja)

Social Media profiles, pages, groups:

Bolsonaro Presidente Sudoeste

Sergio Moro Brasil

7 a 1 para o Juiz Sérgio Moro

Bolsonaro Noticiando

República de Curitiba

Exército Bolsonaro

Augusto Nunes (Veja)

Movimento Do POVO Brasileiro

Eu MORO no Brasil

Jovens de Direita

Movimento Brasil Livre

Bolsonéas

Movimento Força Brasileira

Pensa Brasil

Lula de novo, NÃO

Eu Apoio a Presidente Dilma

Bia Kicks

Diário do Brasil

Direita São Paulo

Templário de Maria

Intervenção Antes Que Tardia – Curitiba

APOIO AO JUIZ SÉRGIO MORO & PROCURADOR DELTAN DALLAGNOL

Apoio à Operação Lava a Jato para deter a corrupção

OndaVermelha

Dilma Rousseff, a legítima presidenta do Brasil.

24 h online

Haroldo Filho PSL

ROTA é ROTA

Brasil Conservador

Direita BR/MT

Patriotas

Por um Brasil Melhor

Bolsonaro Presidente, Brasil Sorridente

Grupo da Página Jair Bolsonaro Presidente 2018

OPERAÇÃO LAVA JATO EU APOIO AO JUIZ SERGIO MORO

Ordem Dourada Do Brasil

APOIO AO JUIZ SÉRGIO MORO E A OPERAÇÃO LAVA JATO

Somos Todos Sérgio Moro

EU APOIO O JUIZ SERGIO MORO E APOIO A POLÍCIA FEDERAL

To comply with ethical principles, personal profiles were not named.