ABSTRACT

the immediate aftermath of crisis events, there is a pressing demand among the public for information about what is unfolding. In such moments “information holes” occur, people and organizations collaborate to try to fill these in real time by sharing information. In this article, we approach such gaps not merely as the product of the actual lack of information, but as generated by the algorithmically underpinned social media platforms as such, and by the user behaviors that they proliferate. The lack of information is the result of the noisy and fragmented patchwork of information that social media platforms can generate. In this paper, we draw on a case study of one particular case of a false terrorism alarm and its unfolding on Twitter, that took place in London’s Oxford Circus underground station in November of 2017. Using a combination of computational and interpretive methods – analyzing social network structure as well as textual expressions – we find that certain logics of platforms may affect emergency management and the work of emergency responders negatively.

Introduction

In today’s age of deep mediatization, more and more aspects of society are saturated with digital communication media in ways that transform our social domains in quite drastic ways (Couldry & Hepp, Citation2017). This also goes for crisis communication and emergency response. As our lives are deeply entangled with a system of variously connected digital platforms, the challenges in ensuring safe and correct information in emergencies are mounting. In the immediate aftermath of crisis events, there is a pressing demand among the public for information about what is unfolding (Mirbabaie, Bunker, Stieglitz, Marx, & Ehnis, Citation2020). In other words, there is a need to gain “situational awareness” (Sarter & Woods, Citation1991; Vieweg et al., Citation2010). This urgent need for validated knowledge in the face of shock and uncertainty is timeless but has been theorized in the digital age in terms of “information holes” (Liu, Fraustino, & Jin, Citation2016). These holes are collaboratively filled on social media by both organizations and the public, and risk becoming exploited by manipulators, for whom mis- and disinformation is an end in itself. As argued by Golebiewski and Boyd (Citation2018) holes in information flows “are a security vulnerability that must be systematically, intentionally, and thoughtfully managed.”

In the context of social media, these risks get even more emphasized, as these platforms’ logic of exponential spreadability can rapidly amplify messages, meaning that what may initially be isolated and/or minor occurrences of wrongful information can rapidly spread – in reach and volume – but also be slightly altered along the way, and thus reproduce into a much larger problem of misinformation. This is also evidenced historically as collective and mass behaviors, in specific geographic and physical locations, can be fueled by misinformation and bring situations to a boiling point before authorities have had the time to act appropriately (McDougall, Citation1920; Smelser, Citation1962). The agile and flexible response allowed by social media platforms can quickly overtake official information due to “the rigid nature of credential-bound public groups like professional crisis response” (LaLone, Kropczynski, & Tapia, Citation2018, p. 13).

In this article, we approach information holes not merely as the product of the actual lack of information, nor necessarily of any conscious and human-driven attempts to withhold information. Even though both those elements may be at play, we want to direct attention to the gaps or errors in the information as largely being generated by the algorithmically underpinned social media platforms as such, and by the user behaviors that they proliferate. The holes are indeed not always the result of having access to too little information. Rather, they are to no small degree the result of the noisy and fragmented patchwork of information that social media platforms can generate.

In the discussions to follow, we draw on a case study of one particular case of a false terrorism alarm and its unfolding on Twitter, namely an incident that took place in London’s Oxford Circus underground station in November of 2017. Our aim, more broadly, is to contribute knowledge about crisis communication in our deeply mediatized age and to do so by focusing on some aspects of how logics of social media platforms may come into play in moments of urgency. Using a combination of interpretive and computational methods – analyzing social network structure as well as textual expressions – we examine the dynamics of digital communication during this unfolding event with a particular focus on information holes and misinformation.

Emergencies and social media logics

Previous research has indeed been done on social media responses to crisis events (e.g. Eriksson, Citation2016; Eriksson Krutrök & Lindgren, Citation2018; Fischer-Preßler, Schwemmer, & Fischbach, Citation2019; Gupta, Lamba, Kumaraguru, & Joshi, Citation2013; Hagen, Keller, Neely, DePaula, & Robert-Cooperman, Citation2017; Mirbabaie & Marx, Citation2020). There is also a long-standing field of research around emergency responders’ interaction with technology and media – social and other (Hiltz, Kushma, & Plotnick, Citation2014; LaLone et al., Citation2018; Palen & Anderson, Citation2016; Reuter et al., Citation2020; Simon, Goldberg, & Adini, Citation2015). However, research about how more specific logics of social media platforms play into these processes is scarcer. Some recent research has emphasized how public reactions and the spread of information during emergencies are clearly shaped in conjunction with the platforms’ design. For example, Reuter, Stieglitz, and Imran (Citation2020) argue that while social media has great mobilizing potential during crises, for example through citizen participation and volunteerism, at the same time it may also enable more problematic phenomena such as fake news, hate speech, censorship, suppression, and discrimination.

To understand how such processes come into expression, and how this relates to the technological dimensions of the platforms, it is key to recognize the role played by the particular logic of social media. Four key elements that are formative of social media logic, according to van Dijck and Poell (Citation2013) are “popularity,” “connectivity,” “programmability,” and “datafication.” The notion of popularity relates to processes around how and why information spreads on social media. Flows of information move fast, they are governed by an economy of visibility, attention, clicks, and links – and they quickly become voluminous. Furthermore, they are susceptible to viral forms of information diffusion (Sampson, Citation2012). This relates to the notion of connectivity, by which internet communication dramatically boosts the reach, pace, and scale of communication (Castells, Citation1996).

In their study of Twitter hashtags, Stai, Milaiou, Karyotis, and Papavassiliou (Citation2018) used an epidemic model to understand hashtag spread and the ways in which certain information was propagated through retweeting practices. They argued that being an “informed” Twitter user not only implies having produced or reproduced content on the platform but also having contributed to the spread of information simply by seeing – being exposed to – tweets. Indeed, the information that starts to circulate during unfolding events may not be valid (Gupta et al., Citation2013; Starbird, Maddock, Orand, Achterman, & Mason, Citation2014), largely because social media platforms are likely to generate different forms of “noise” (Anderson, Citation2014), which obscure or block out conflicting, sometimes more accurate, information. In addition, there is an increased destabilization of information caused by developments such as spam, bots, and algorithmically constituted filter bubbles, alongside phenomena like those described in terms of “post-truth” (Kucharski, Citation2016; Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, Citation2017). In turn, these phenomena relate to the notions of programmability and datafication, described by van Dijck and Poell (Citation2013) as key components of social media logic. Communication over – as in the case of our study – Twitter is always brief and also potentially fragmented. This is both because of the set character limits of the platform and due to how algorithms contribute to who sees what (Boot, Tjong Kim Sang, & Dijkstra et al., Citation2019; Economist, The, Citation2012; Gonzales, Citation2012).

As argued by Nguyen and Nguyen (Citation2020), it is useful to draw on social amplification theory when understanding such processes on social media. They write about how dramatic or risky events that affect a community, will “interact with individual psyches and socio-cultural factors – such as the intensity of public reactions on social networks,” in ways that create a space for miscommunication. Even minor disruptions in the relay of correct information can get far-reaching consequences. Widespread uncertainty alongside a “thirst for answers” among the public can generate “informational chaos” (Nguyen & Nguyen, Citation2020, p. 445). With the case study presented in this article, we analyze how information holes, paired with the rapid and urgent pace of social media responses to emergencies, can set processes of misinformation in motion.

Case description and data

On 24 November 2017, at 16:38 (GMT), London’s Oxford Circus underground station was suddenly evacuated during the ongoing Black Friday discount shopping event, and people were told to take shelter in nearby shops on Oxford Street. Several calls were made to the police by individuals claiming to have heard multiple shots fired in Oxford Street. The reaction to this incident in the form of social media posts and emergency calls, triggered the “anti-terrorism emergency response” of the Metropolitan Police, something which was also communicated via their social media channels. In fact, the London Police have been using its social media frequently during specific societal crises, since its responses to the 2008 and 2011 London riots (Crump, Citation2011; Denef, Bayerl, & Kaptein, Citation2013).

Media reports described what followed in terms of a “stampede for cover” as “armed officers flooded the area” and social media users “went into overdrive” (Mendick & Yorke, Citation2017). About an hour after the first alarm, the police issued a statement saying that they had “not located any trace of any suspects, evidence of shots fired or casualties” (Siddique, Citation2017). The only casualties reported afterward were one or two minor injuries sustained by people stumbling to the ground as they had fled.

The UK, and London specifically, had indeed been sensitized by a number of actual terror attacks in 2017 – notably those at Westminster Bridge (March 22), Manchester Arena (May 22), London Bridge (June 3), Finsbury Park (June 19), and Parsons Green on September 15 (BBC, Citation2017; Lester, Citation2017). The UK Terror Threat Level had been increased by the government following the Parsons Green bombing to the highest level (“Critical”), but was lowered one step to “Severe” two days later. This level, meaning that “an attack is highly likely” was in effect at the time of the 2017 incident in the Oxford Circus station (Wikipedia, Citation2019).

Our dataset includes tweets posted between 09:00:00 and 23:59:59 GMT on 24 November 2017 (n = 468,342) and was collected via Twitter’s v 2.0 API using the Academic Research product track (Twitter, Citation2021). The keyword queries were for the phrases “Oxford Street” and “Oxford Circus” as well as for the hashtags “#oxfordcircus” and “#oxfordstreet.”

Even though the tweets collected are public and openly available, we have chosen to not reproduce any of them here in their original format. Instead, we have altered their wordings to prevent them from being traceable in their original form through online searches of direct phrases (Markham, Citation2012). However, in line with Williams, Burnap, and Sloan (Citation2017), tweets from organizational accounts, and public figures, have not been altered in this way, as they can be seen as constituting societal information from official accounts.

An explosive reaction

As illustrated in , tweeting activity increased suddenly and dramatically following the first report on the evacuation of the underground platform. This kind of intense reaction to emerging events is often seen on social media, and especially in relation to terrorist attacks (see for example Eriksson, Citation2016). Indeed, the first hour after the initial alarm proved to be the most intense, with a top marking of almost 2750 tweets per minute (i.e. 46 per second). In , the lighter gray plot mimics the expected diurnal variation of tweet frequencies (Grinberg, Naaman, Shaw, & Lotan, Citation2013), and the relatively high (~500/minute) frequency of tweets matching the keywords (mainly “Oxford Street”) is explained by the ongoing Black Friday shopping event. The frequency levels that are plotted in a darker shade correspond with the, roughly, three-hour period following the alarm and are illustrative of the most urgent phase of the response.

Figure 1. Number of tweets, matching the search terms, per minute 9:00 – midnight, 24 November 2017.

After removing stop words, and other generic terms such as place names, the most common words in tweets posted following the incident were “police,” “scene,” “shots,” “panic,” “run,” and “safe,” all relating to, either the incident itself, or the actions of the public present at the scene. All of these words relate to the urgency of the most acute phase of the event. For example, the use of the words “panic” and “run” relates to the actual evacuation of the underground platform, and the atmosphere of urgency which was reported on Oxford Street, and its adjacent facilities. Additionally, the word “shots” relate to the reporting from several individuals at the scene of the incident of having heard gunshots being fired.

This means that we can identify the spike in posting activity as clearly reflecting and coinciding with the crowd reaction around the false alarm in the underground. It is also worth noting that while the share of retweets increased during the event (with 76% between 17:00 and 20:00, compared to 65% 13:00–16:00), there was also an increased number of original tweets being crafted during the emergency – with 271 original tweets per minute 17:00–20:00, and 150 between 13:00 and 16:00). So, while an elevated level of retweeting contributed to the heightened number of tweets per minute, it does not appear to have been the sole driver.

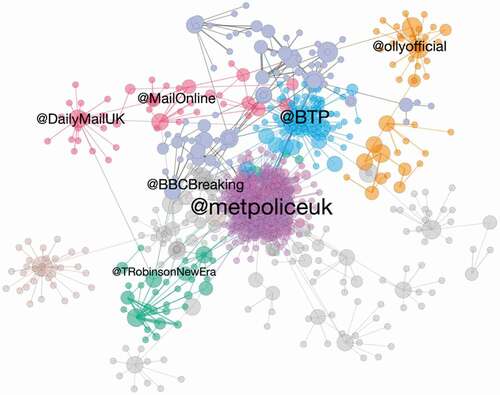

Focusing the analysis closer on the time following the alarm (16:00 to midnight) 76% of tweets posted also in that time frame were retweets, and 4% of tweets mentioned other user accounts by other means, for example through using Twitter’s quote or reply function. provides a visualization of the relational network constituted through the tweets. The network has a set of different clusters within which a relatively small number of user accounts assumed central positions in the unfolding social media response. The network analysis was carried out using NetworkX (Hagberg, Swart, & Chult, Citation2008) and visualized using Gephi (Bastian, Heymann, & Jacomy, Citation2009). It was focused on looking at relationships between Twitter accounts that were using the analyzed keywords, with relationships being defined as any form of mention (retweet, reply, quote, mention) of one account by another. The visualization was filtered by betweenness centrality and edge weights to display only the most prominent accounts and interactions across the dataset, and clusters were color coded based on modularity class.

Amplification loops

First, the communication was heavily influenced by two Twitter accounts belonging to emergency services: the Metropolitan police (@metpoliceuk) and the British Transport Police (@BTP). Their adjacent positioning in the network layout reflects that they are often referencing each other. The top most retweeted tweets in the dataset were from these emergency services. The Metropolitan police, the UK’s largest police service, has an active presence on Twitter, and the following tweet, which became the most retweeted tweet in the dataset (7947 times), was posted 38 minutes after the first reports of an incident in the Oxford Circus underground station. It labeled the situation as being potentially “terrorist related”:

Police called at 16:38 to a number of reports of shots fired on #OxfordStreet & underground at Oxford Circus tube station. Police have responded as if the incident is terrorist related. Armed and unarmed officers are on scene and dealing along with colleagues from @BTP

While tweets from emergency services can generally be assumed to be “safe” sources of reliable information on situations such as these, they were not in this case able to neither confirm nor contradict the severity of the incident. The fact that this ambiguous and tentative information was posted by a usually reliable source, due to its own lack of accurate information, contributed largely to shape the overall reaction on Twitter.

Furthermore, a couple of generally influential social media profiles were prominent in the network. One of these was singer and television presenter Olly Murs (@ollyofficial), who was one out of many Twitter users on the ground who were reporting having heard gunshots or witnessed a gunman at the scene. Another was former leader of the English Defense League, Tommy Robinson (@TRobinsonNewEra) who tweeted claiming that the alleged attack was a case of Islamist terror. Tweets such as these thereby reached the large audiences of a couple of already popular Twitter accounts with problematic (misinformed and propagandistic, respectively) information.

By extension, this propagated ambiguity and confusion as – in the absence of other information – the imperfect information got picked up and hence boosted by news outlets. Consequently, the visualization also shows how mainstream news media were central to the crisis conversation, via the Daily Mail (@DailyMailUK and @MailOnline) and The BBC (@BBCBreaking). For example, the Daily Mail reported several misinformed stories regarding a gunman present at the scene, and also about an alleged truck attack.

In turn then, the explosive reaction shown in , gained momentum. This was especially the case as large numbers of Twitter users quickly started to retweet and post about the available bits of wrongful or ambiguous information. More generally, the spreading and sharing of mainstream media reports have been shown to have implications for the ways in which online publics are able to gain situational awareness (Bruns & Burgess, Citation2012). Also in this case, crowdsourced co-amplification of such stories contributed to the confusion and urgency around the incident. In the analyzed dataset, 31% of tweets contained links to websites mainly from news sources, indicating that the sharing of information from news sources were common practice during this incident.

Similarly, many users’ practice of sharing information posted by emergency services on Twitter, also caused problems in this case. Sharing information from such, usually reliable, sources is often referred to as an ethical way of communicating online in times of crisis. In fact, there has been an increased awareness among digital publics about active ways of avoiding the spread of mis- and disinformation during crises. Because of this, many Twitter users were actively asking others to stop spreading unverified information:

The misinformation being spread on the #oxfordstreet tag is insane. Please don’t pass along info unless it’s been confirmed by witnesses or an official source. You’re not helping.

At times like this, can the Daily Mail just be banned from posting anything until facts are verified? They do not help with making wild claims that cannot be backed up. Should be ashamed of themselves. #oxfordcircus

It is noteworthy that such sentiments were indeed present, also in the heat of the moment. However, in the explosive wave of tweeting following the incident (see ), the information from emergency responders was vague and in fact, added to the uncertainty surrounding this incident. Within the first ten minutes after the first reports of the underground station’s evacuation, a bystander tweeted that there had been a fight involving several people at the Oxford Circus station, and that she had been trampled on in the altercation. “That’s why it has been evacuated,” she added. This information, however, was not able to break through the raging flood which by this point meant that more well-informed tweets were drowned out. Likely due to their dramatic and triggering character, the ambiguous emergency service tweets, mentioning gunshots and terrorism, were continuously shared and spread even long after the emergency status was officially declared a false alarm.

Discussion and future research

With this article, we have drawn on a particular case study to illustrate the usefulness of sociotechnical understandings of processes of emergency response more broadly. We mean by this that well-known and understood perspectives on the social psychology of acute events (such as the urgent need for information), can be fruitfully combined with similarly well-documented understandings of the logics of social media platforms (such as their rapid, “viral,” forms of amplification).

From such a perspective, it is clear that social media can play an important, but potentially deceptive role during crisis alerts. On the one hand, the availability and handiness of social media platforms enable people to react quickly and publicly, and to co-ordinate. It also enables them to search for information on the spot. Social media may indeed sometimes be an important source for emergency responders, and others, when it comes to understanding an unfolding crisis or emergency from the real-time perspective of individuals. But on the other hand, this is, firstly, without any guarantees that the information that if found will be accurate. Secondly, the juggernaut character of the social media machinery, once the wheels start spinning, unstoppable, can easily and rapidly make a public reaction take on a life of its own, that through omnipresent mobile devices, feeds back via algorithmically and socially boosted misinformation into potential chaos on the ground. The algorithmic element has to do with how automated recommendation systems on the platforms tend to make the popular content even more popular, by exposing it more prominently, while the social element consists in users themselves also engaging in acts to boost, e.g. by retweeting, the visibility of certain content or users (van Dijck & Poell, Citation2013, p. 7).

Our case study thus more generally aligns with the ongoing scholarly discussions about how online participation through social media offers up both opportunities and challenges for managing emergencies (Palen & Anderson, Citation2016; Reuter et al., Citation2020). More specifically, however, it directs attention to how certain logics of platforms, such as their propensity to amplify – or rather widen – gaps in flows of information, play a role in these processes. As shown in our analysis, this amplification can take place in loops where information that is fragmented, erroneous, taken out of context or out of proportion is filtered through both algorithmically driven systems that govern visibility on the platforms, and user behaviors enabled by platform affordances such as retweeting. As shown in this article, some individual tweets concerning the Oxford Circus incident were massively retweeted and spread across the platform in ways that affected the ability of digital publics to gain appropriate situational awareness.

It is interesting to note that the asynchronous element of social media streams, by which older posts can be bumped to the top of the feed through actions such as retweets, leads to a situation where new information which is potentially more reliable may become drowned out by older information, which may potentially be incorrect or misleading – and vice versa. This is especially true in these times of algorithmically ordered information streams on digital platforms, where Twitter for example does not display tweets to its users in strict chronological order but rather presents the user with “suggested content powered by a variety of signals,” where entities such as “Top Tweets” enter into the equation and have an effect on what the user sees first (Twitter, Citation2020). This may have implications both for individuals and emergency responders in gauging updated information.

This study shows the value in being aware of how platform logics may affect information streams in moments of urgency. While the practice of spreading verified information is obviously important for combating misinformation, we have shown with this case study that there is no guarantee that authorities’ own information cannot also contribute to digital noise, which in turn affects situational awareness on all levels. This has also been exemplified by Simon et al.’s (Citation2014, p. 1) discussion of the use of Twitter following the 2013 Westgate Mall terrorist attack in Kenya, where an “abundance of Twitter accounts providing official information made it difficult to synchronize and follow the flow of information.” The same can be said in the case of the Oxford Circus incident. Thus, while specific actors have been understood as more “reliable” than others, the fact that also the emergency service tweeting became a liability for ordinary citizens’ orientation during this terror alert, underlines that control over the posted information is out of the hands of the original poster once it gets sucked into the machinery.

The urgent need for information that arose as the Oxford Circus incident was first reported, can be said to have set off what Webb and Jirotka (Citation2016) refer to as a “digital wildfire” – a name for phenomena that “break out when content that is either intentionally or unintentionally misleading or provocative spreads rapidly with serious consequences.” When looking closer at the explosiveness of the Twitter reaction to the Oxford Circus situation, it is evident that the processes of misinformation were boosted further by the logics of spreadability and virality that are inherent to social media platforms (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, Citation2013; Sampson, Citation2012). In cases such as the one analyzed here it becomes clear how the work of emergency responders can be negatively affected by such processes. Noting such difficulties, St Denis et al. (Citation2020) have for example developed a machine learning classifier for automating local-level information gauging in real time, with the aim of aiding emergency responders’ own situational awareness.

More generally, Twitter has become increasingly aware of the problem of logics that allow certain information to spread disproportionately across the platform. Baym and Burgess and Baym (Citation2020) have argued, albeit in relation to political discourse and elections, that rapid-fire retweeting on the platform may cause disruption and problems. While seen, in our case, in the setting of emergency response, such processes had a huge impact here too on how the situation played out. To counteract such effects – and then once again in the context of politics – Twitter nudged its users to “quote” rather than retweet during the US election in 2020. Quoting is a separate function on the platform where users are asked not only to pass a tweet forward (as with retweets), but to add their own commentary to the original tweet (Lyons, Citation2020). This was a step toward avoiding massive retweeting cascades during ongoing events. To further scrutinize such sociotechnical mechanisms that this article has highlighted, future analyses of crisis communication on the internet have much to gain from taking more cues from emerging fields of scholarship such as software studies (Fuller, Citation2008; Kitchin & Dodge, Citation2011; Manovich, Citation2013), and platform studies (Bucher & Helmond, Citation2018; Dijck, Poell & Waal, Citation2018; Gillespie, Citation2010).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank dr. Samuel Merrill for his contributions in identifying the empirical case for this article, and for insightful comments on both our ongoing work and the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, L. (2014). Social Media Noise. In K. Harvey (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social media and politics (pp. 1167). California: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452244723

- Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009) ‘Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks’, in Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/09/paper/view/154 (Accessed: 15 May 2019).

- BBC. (2017). Timeline of british terror attacks. BBC News, June 19, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-40013040.

- Boot, A. B., Tjong Kim Sang, E., Dijkstra, K. et al. (2019). How character limit affects language usage in tweets. Palgrave Commun, 5(76), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0280-3

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2012). Local and global responses to disaster: #eqnz and the Christchurch earthquake. In P. Sugg (Ed.), Disaster and emergency management conference, conference proceed- ings (pp. 86–103). Brisbane, QLD: AST Management Pty Ltd, Brisbane Exhibition and Convention Cen- tre.

- Bucher, T., & Helmond, A. (2018). The affordances of social media platforms. In Bruns et al. (eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media, Sage Publications, 9781412962292. http://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=149a9089-49a4-454c-b935-a6ea7f2d8986.

- Burgess, J., & Baym, N. K. (2020). Twitter: A biography. New York: NYU Press.

- Castells, M. (1996). the rise of the network society. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2017). The mediated construction of reality. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Crump, J. (2011). What are the police doing on twitter? Social media, the police and the public. Policy & Internet, 3(4), 1–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2202/1944-2866.1130

- Denef, S., Bayerl, P. S., & Kaptein, N. (2013). Social media and the police: Tweeting practices of British police forces during the August 2011 riots. SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Paris, France: ACM 3471–3480.

- Economist, The (2012). Brevity: Twtr. The Economist, 31 March, 2012. https://www.economist.com/international/2012/03/31/twtr.

- Eriksson, M. (2016). Managing collective trauma on social media: The role of Twitter after the 2011 Norway attacks. Media, Culture & Society, 38(3), 365–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715608259

- Eriksson Krutrök, M., & Lindgren, S. (2018). Continued Contexts of Terror: Analyzing Temporal Patterns of Hashtag Co-Occurrence as Discursive Articulations. Social Media + Society: 4(4): 1-11.

- Fischer-Preßler, D., Schwemmer, C., & Fischbach, K. (2019). Collective Sense-Making in Times of Crisis: Connecting Terror Management Theory with Twitter User Reactions to the Berlin Terrorist Attack. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 138–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.012

- Fuller, M. (ed.). (2008). Software Studies: A Lexicon. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Gillespie, T. (2010). The Politics of ‘Platforms.’ New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

- Golebiewski, M., & Boyd, D. (2018). Data Voids: Where missing data can easily be exploited. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Data-Voids-2.0-Final.pdf

- Gonzales, J.-R. P. (2012). “Conventions of the english language in the twitterverse.” In 2011-2012. Prized Writing, 116–125. UC Davis.

- Grinberg, N., Naaman, M., Shaw, B., & Lotan, G. (2013). Extracting diurnal patterns of real world activity from social media. Proceedings of the Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media 7, 205–214.

- Gupta, A., Lamba, H., Kumaraguru, P., & Joshi, A. (2013). Faking Sandy: Characterizing and identifying fake images on twitter during hurricane sandy. Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on World Wide Web: 729–736.

- Hagberg, A., Swart, P., & Chult, D. S. (2008) Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using networkx. LA-UR-08-05495; LA-UR-08-5495. Los Alamos National Lab. (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States). Available at: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/960616 (Accessed: 29 October 2020).

- Hagen, L., Keller, T., Neely, S., DePaula, N., & Robert-Cooperman, C. (2017). Crisis communications in the age of social media: A network analysis of zika-related. Social Science Computer Review, 36(5), 523–541. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317721985

- Hiltz, S. R., Kushma, J. A., & Plotnick, L. (2014). Use of social media by us public sector emergency managers: barriers and wish lists. ISCRAM.

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable Media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Kitchin, R., & Dodge, M. (2011). Code: Software and everyday life. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10479192

- Kucharski, A. (2016). Post-Truth: Study epidemiology of fake news. Nature, 540(7634), 525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/540525a

- LaLone, N. J., Kropczynski, J., & Tapia, A. H. (2018). The symbiotic relationship of crisis response professionals and enthusiasts as demonstrated by reddit’s user-interface over time. Proceedings of the 15th ISCRAM Conference.

- Lester, N. (2017). Britain’s Year of Terror: Timeline of Attacks in 2017. Sky News, 15 September 2017. https://news.sky.com/story/britains-year-of-terror-timeline-of-attacks-in-2017-11036824 .

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

- Liu, B. F., Fraustino, J. D., & Jin, Y. (2016). Social media use during disasters: How information form and source influence intended behavioral responses. Communication Research, 43(5), 626–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565917

- Lyons, K. (2020) ‘Twitter is fighting election chaos by urging users to quote tweet instead of retweet,’ The Verge, 9 October. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2020/10/9/21509439/twitter-election-trump-quote-tweet-labels-rules-election (Accessed: 30 October 2020).

- Manovich, L. (2013). Software Takes Command. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Markham, A. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice. Information, Communication & Society, 15(3), 334–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993

- McDougall, W. (1920). The group mind. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Mendick, R., & Yorke, H. (2017). Oxford Circus: Met police end operation after thousands flee in panic over reports of ‘gunshots.’ The Telegraph, November 24, 2017. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/11/24/oxford-circus-station-evacuated-armed-police-respond-incident2/.

- Mirbabaie, M., Bunker, D., Stieglitz, S., Marx, J., & Ehnis, C. (2020). Social media in times of crisis: Learning from hurricane harvey for the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic response. Journal of Information Technology, 35(3), 195–213.

- Mirbabaie, M., & Marx, J. (2020). ‘Breaking’ news: Uncovering sense-breaking patterns in social media crisis communication during the 2017 Manchester bombing. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(3), 252–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1611924

- Nguyen, H., & Nguyen, A. (2020). Covid-19 Misinformation and the Social (Media) Amplification of Risk: A Vietnamese Perspective. Media and Communication, 8(2), 444–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.3227

- Palen, L., & Anderson, K. M. (2016). Crisis informatics—New data for extraordinary times. Science, 353(6296), 224–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2579

- Reuter, C., Stieglitz, S., & Imran, M. (2020). Social media in conflicts and crises. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(3), 241–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1629025

- Sampson, T. D. (2012). Virality: Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sarter, N. B., & Woods, D. D. (1991). Situation awareness: A critical but ill-defined phenomenon. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 1(1), 45–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0101_4

- Siddique, H. (2017). Oxford Circus: Police stood down after incident in central london. The Guardian: UK News, 24 November 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/uknews/live/2017/nov/24/oxfordcircuspolicelondon-tube-gunshots-live

- Simon, T., Goldberg, A., & Adini, B. (2015). Socializing in emergencies - a review of the use of social media in emergency situations. International Journal of Information Management, 35(5), 609–619. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.07.001

- Simon, T., Goldberg, A., Aharonson-Daniel, L., Leykin, D., Adini, B., & Gupta, V. (2014). Twitter in the cross fire—the use of social media in the westgate mall terror attack in kenya. PloS One, 9(8), e104136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104136

- Smelser, N. J. (1962). Theory of collective behaviour. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- St Denis, L. A., Hughes, A. L., Diaz, J., Solvik, K., Joseph, M. B., & Balch, J. K. (2020). ‘What I need to know is what i don’t know!’: Filtering disaster twitter data for information from local individuals, CoRe Paper – Social Media for Disaster Response and Resilience Proceedings of the 17th ISCRAM Conference, Blacksburg, VA, USA May 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343485694_%27What_I_Need_to_Know_is_What_I_Don%27t_Know%27_Filtering_Disaster_Twitter_Data_for_Information_from_Local_Individuals. Accessed: October 22, 2020.

- Stai, E., Milaiou, E., Karyotis, V., & Papavassiliou, S. (2018). Temporal dynamics of information diffusion in twitter: Modeling and experimentation. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems, 5(1), 256–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSS.2017.2784184

- Starbird, K., Maddock, J., Orand, M., Achterman, P., & Mason, R. M. (2014). Rumors, false flags, and digital vigilantes: Misinformation on twitter after the 2013 Boston marathon bombing. IConference 2014 Proceedings.

- Twitter (2020). About your Twitter timeline. Twitter. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20201026172500/https://help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/twitter-timeline (Accessed: 30 October 2020).

- Twitter (2021). Twitter API v2 for Academic Researchers. Twitter. https://developer.twitter.com/en/solutions/academic-research/products-for-researchers.

- van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding social media logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v1i1.70

- van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vieweg, S. et al. (2010) ‘Microblogging during two natural hazards events: What Twitter may contribute to situational awareness’, in CHI 2010 Proceedings, 1079–1088.

- Webb, H., & Jirotka, M. (2016). How to police ‘digital wildfires’ on social media. The Conversation. August 1, 2016. http://theconversation.com/how-to-police-digital-wildfires-on-social-media-63220. Accessed October 8 2020.

- Wikipedia. (2019). UK Threat Levels. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=UK_Threat_Levels&oldid=928551201. Accessed: November 30, 2019.

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an ethical framework for publishing twitter data in social research: Taking into account users views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology, 51(6), 1149–1168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517708140