It’s seven in the morning, and the day’s first light casts long shadows on the dirt roads of the batey. Two hours away from Santo Domingo, the rural community with roots in sugar cane has continued to grow despite being abandoned a quarter century ago by the Consejo Estatal del Azúcar, the state body overseeing sugar mill operations. One family has spent the night in funeral prayers, and the deceased woman’s son—who we’ll call Armando to protect his safety—heads out to get something for breakfast. When he returns, he hears shouts from eight police officers surrounding the house. Two young people are already detained, and the police are requesting documents from the others. Nobody tries to flee. “Why are they taking people away?” Armando questions, trying to film. “There are no criminals here!”

“Documents, moreno!” an officer yells at him, swiping to snatch away his cell phone. Armando’s brother-in-law knows one of the police and intervenes to prevent his arrest. Armando hands over his ID. “Are you in the military?” the officer asks, pointing to the words on the back of the card: “No vota.” They let Armando go and release one of the two detainees. They take the other to the police station, where they demand a ransom of 30,000 pesos, approximately $550. The man is the husband of one of Armando’s cousins. The family cannot pay, and the man is deported. Days later he will return, paying other police and soldiers along the way to be allowed to pass.

Retired cane workers face a line of police outside the Ministry of Labor in Santo Domingo, December 7, 2022. (SIMÓN RODRÍGUEZ)

Two weeks later, in the same community, another “operation” strikes at dawn. Breaking down doors despite not having a search warrant, immigration agents enter homes and get people out of their beds. They take 10 more “morenos,” among them one of Armando’s childhood friends. They steal detainees’ cell phones and ask for 15,000 pesos to release each one. Some are Haitian immigrants, and others are Dominicans with Haitian parents or grandparents.

Shortly before this second operation, President Luis Abinader had vociferously rejected calls from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to suspend mass deportations of Haitians and to make an effort to prevent racial discrimination. “The Dominican Republic is not only going to continue deportations, but it is going to increase them,” Abinader threatened. “[The country] has been economically affected [and] has shown much more solidarity [with Haiti] than all the countries in the world.” That day, November 12, 2022, Abinader signed decree 668-22, creating a special police unit to persecute foreigners occupying state or private land. This is the situation in most bateyes, often home to Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent. The decree established consequences including expulsion and a ban on re-entering the country.

The mass deportation campaign hit a record 171,000 expulsions in 2022, almost all targeting Haitians. That number is more than triple the annual average of the previous five years and 20 times more than the total number of deportations in 2011. The rate continues to rise: in the week of May 30 to June 6, 2023, 4,603 people were expelled, all Haitians except for one person from the United States and one from Poland. Among those deported are thousands of children separated from their families and hundreds of pregnant women, many of them detained in and near hospitals. Torture, rape, and murder have been reported. The government has celebrated this “successful” campaign, boosting it with the largest purchase of military equipment since 1961, the last year of the Trujillo dictatorship, in the name of containing the supposed Haitian threat.

When the Dominican government launched a deportation campaign based on racial profiling in January 2004, a human rights lawyer called the policy “Caribbean-style apartheid.” Today, not only are the numbers of mass deportations much higher, but authorities have also consolidated policies of racial oppression, such as the mass denationalization of Dominicans of Haitian descent, which Noémie Boivin has analyzed as an act of apartheid under international law. In this effort to build apartheid in the Caribbean, the Dominican state has relied for many years on an important supplier of weapons and police and military training, as well as political inspiration: the Israeli apartheid regime.

Racist Denationalization

Armando is 34 years old. He is not a foreigner or a member of the military, but the state does not consider him Dominican, which is why his ID indicates that he is not allowed to vote. His maternal grandparents arrived from Haiti in 1968, during the dictatorship of Joaquín Balaguer, to work in the sugar industry. His mother was born in the Dominican Republic, just like him. On September 23, 2013, Constitutional Court ruling 168-13 required people born in the Dominican Republic to foreign parents after 1929 to prove their parents’ immigration status to retain Dominican nationality. In practice, this court ruling was applied only to people of Haitian descent. Armando was made stateless, alongside some 200,000 other people, according to UN estimates.

Young people impacted by the ruling mobilized, pushing the government of Danilo Medina to introduce Law 169-14, which divided the people affected into two groups. Those in Group A, who already had Dominican identity documents, regained their nationality but were added to a racially segregated civil registry. Those in Group B, including Armando, lost their citizenship status but were allowed to enter a regularization plan for foreigners, with the promise that they would be eligible for naturalized citizenship in two years. Nine years after Law 169-14 was introduced, the Movimiento Reconocido, a civic network of Dominicans of Haitian descent, denounced that of the more than 8,000 people who applied for the regularization program, not one had yet been granted naturalized citizenship.

Armando’s ID expired two years ago, and there is no procedure to renew it. Like thousands of people in his situation, he fears being arrested and extorted by the military and police, or being expelled from the country. He does not have recognized political rights. He cannot go to university, have a formal job, open a bank account in his name, or receive health insurance. In the eyes of the state, he is a Haitian without a visa—an “illegal.”

According to some official estimates, most Haitian immigrants—around 700,000 people—do not have a residence visa, even after decades of working in the country. Added together, Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian immigrants represent 8 percent of the Dominican population, and their labor force is crucial in industries such as sugar and other agricultural products, construction, and ser vices. Even the government exploits Haitian workers on official construction sites, including the project to expand the wall on the border with Haiti. Initially, the authorities were in talks with Israeli companies to provide surveillance technology along the wall, which is expected to cover half of the 244-mile Haitian-Dominican border, but for economic reasons, the government ultimately opted for other providers.

The New Phase of Anti-Haitianism

A mid the 1937 massacre known as El Corte, during which the Trujillo regime murdered more than 17,000 Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent near the border, the boy who would later be known as José Francisco Peña Gómez was separated from his mother. He was less than one year old. He had Haitian ancestry on both sides of his family and was adopted and raised by another Dominican family after the massacre. From a young age, he stood out as a politician, and he played an important role in the April Revolution of 1965, which sought to restore President Juan Bosch to power after a coup two years earlier.

In August 1982, the remains of Peña Gómez’s mother, María M a r ce lin o, w er e r ep a t r i a t e d . She had taken refuge in Haiti in 1937 together with thousands of Black Dominicans and Haitians. During the burial in Santo Domingo, Peña Gómez recalled the “people fanaticized by anti-Haitianism and racism” who falsely accused him of “usurping” Dominican nationality. “Haitians are considered by certain social sectors who invoke a false Spanishness to be inferior beings, subhuman,” he said in a speech. “For this reason, for all the years of my life I have silently endured the most inconsiderate racist insults, and I have often heard people poisoned by hate shout at me: Haitian! It is a name that has acquired a pejorative and denigrating meaning … despite being the name that the inhabitants of a nation with a great history proudly bear.”

Peña Gómez died in 1998, but his words remain relevant. No leader of any of the establishment’s political parties would be able to utter similar pronouncements today. Ruling 168-13 institutionalized and expanded the practice of disputing the nationality of Dominicans of Haitian descent, which Peña Gómez suffered personally in the form of dirty political campaigns. Abinader, who claims to uplift Peña Gómez’s legacy, campaigned in 2019 calling to “prevent the merger of the Dominican Republic and Haiti” and characterizing Haitian immigration as a threat to national independence. From the beginning of his government, Abinader upheld a definition of Haitians as the “foremost threat” to the country, creating the political conditions for the current campaign of racist persecution.

Dominican apartheid is ideologically based on historical anti-Haitianism, which has its roots in colonial slaveholders’ fears of Black rebellion and their resentment over the abolition of slavery during the island’s political unification between 1822 and 1844. This is why, in the first years after the separation of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, the accusation of “negrophilia,” love of Blackness, was synonymous with treason against the Dominican homeland, much as the term “pro-Haitian” is today. Such accusations were even used to justify executions, such as that of the prominent military officer José Joaquín Puello in 1847.

Denialists of the Dominican state’s racism habitually attribute the 1937 massacre exclusively to Trujillo, as if it were an individual crime. But in addition to the fact that the massacre’s objectives had broad support among an intelligentsia that continues to hold political sway today, it is undeniable that the ethnic cleansing program has been recreated in contemporary form. The current government claims to act in the name of repelling the “demographic threat” and “Dominicanizing the border.” Article 10 of the constitution, which was reformed in 2015, establishes a border property regime that privileges “the property of Dominicans,” thus shielding the land thefts perpetrated in 1937.

Abinader is in fact more of a political heir to Balaguer, whose different presidencies spanned more than two decades. Balaguer described Haiti as the main threat to the Dominican nation. In his book La isla al revés, he disguised the goal of recolonizing Haiti under the misleading formula of a binational federation. Abinader’s constant agitating in support of international military intervention and occupation of Haiti in the name of “pacification” can be understood as a new iteration of the Balaguer-style reactionar y vision of putting an end to Haitian self-determination.

The Labor Co de, approve d in 1992 dur ing Balaguer’s last government and upheld by Abinader, prescribes the “Dominicanization of the workforce.” While the Trujillo regime required companies to employ a minimum of 70 percent Dominican workers, with exceptions for the sugar industry, the minimum introduced in the Balaguer era is 80 percent, with similar exceptions. It is a reactionary clause, designed to cover up restrictions on union organizing by creating the illusion that, in order to protect their jobs, Dominican workers must demand the persecution of Haitian workers.

Although Abinader consistently speaks of the supposed burden of Haitian immigration on the Dominican state, the evidence points to the contrary. The super-exploitation of Haitian workers in the Dominican Republic has been clear for decades. At the end of 2022, the U.S. government suspended sugar imports from Central Romana, the main sugar producer on Dominican soil, over reports its workers were forced to endure overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions, workplace harassment, miserable wages, and human trafficking. Forty years earlier, in August 1982, the UN Human Rights Commission received a report from the Anti-Slavery Society on the forced labor of Haitian immigrants in the sugar, coffee, and cotton industries. The Dominican Republic’s acting president at the time, Jacobo Majluta, reacted just like Abinader did when he came to the defense of Central Romana last year.

As Haiti suffered under the boots of foreign occupation between 2004 and 2017, Dominican business figures expanded their operations in that country, even benefiting from PetroCaribe, a financing program provided by the Venezuelan government to free up dollars for Haitian development projects. Approximately $2 billion in PetroCaribe funds were mismanaged, and one of the capitalists singled out for participating in the embezzlement was Dominican senator Félix Bautista. The Haitian crisis, far from representing a “burden” for the Dominican state, has allowed the local bourgeoisie to increase their exports to Haiti and turn the trade balance totally in their favor. It is the immigrant workers who, together with their Dominican counterparts, carry the heavy burden of poverty while producing wealth for one of the most unequal countries in the world.

Another Link in a Long Chain

After suffering two U.S. invasions, spending almost half of the 20th century under military dictatorships, and witnessing the defeat of the 1965 April Revolution, not to mention the factors of economic asymmetry and geographic proximity, the Dominican Republic remains subordinate to the United States. This explains the participation of Dominican troops in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and logistical support for the coup in Haiti a year later. During a recent visit, the U.S. deputy secretary of state praised the country as a “vibrant and energetic democracy,” even though the Biden administration has identified racist policies such as racial profiling in Dominican migration processes.

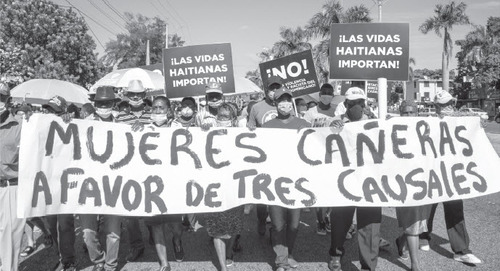

Demonstrators carry "Haitian lives matter!" placards during a demonstration against violence against women in Santo Domingo, November 25, 2021. Members of the Cane Workers' Union (UTC) hold a banner in favor of three proposed exceptions to the Dominican Republic's total abortion ban. (GUILLERMO CASADO)

This alliance with the United States has in turn brought the Dominican Republic closer to another so-called democracy: Israel. When President Donald Trump announced in 2020 that he would move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, the Dominican Foreign Ministry followed his lead. The Dominican foreign minister has repeatedly expressed his solidarity with Israel in the face of Palestinian “terrorism,” while the Israeli ambassador, Daniel Biran, recently declared that in the Dominican Republic “there is no antisemitism.”

In the Dominican Republic, Jews are generally perceived as “white.” For this reason, Trujillo offered to receive 100,000 Jewish refugees during World War II as part of his “whitening” policy, although less than 800 people ultimately benefited as government corruption hindered the arrival of refugees. However, antisemitic clichés abound among the Dominican Right and Christian fundamentalist sectors, such as conspiracy theories about supposed “globalist” plans, in which Jewish bankers and businessman George Soros figure prominently. Far-right groups openly endorse the fascist and antisemite Benito Mussolini. Although these groups are marginal, they are tolerated and participate in anti-Haitian “patriotic marches” organized by the Duartiano Institute, a state institution.

For Israel, the right-wing governments and dictatorships of Latin America and the Caribbean have been traditional clients of its arms industry, including the antisemitic dictatorship of Jorge Videla in Argentina. Israel sold arms to the Duvaliers in Haiti, the Somozas in Nicaragua, Hugo Banzer in Bolivia, Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, and Augusto Pinochet in Chile. Between the end of 1957 and the beginning of 1958, Israel sold $15 million worth of weapons to the Trujillo dictatorship, and between 1974 and 1977, it provided Uzi submachine guns to the Balaguer dictatorship. As he did in the case of his business with the Somoza dynasty, Shimon Peres, then the director general of the Israeli defense ministry and eventual prime minister, tried to justify his dealings with Trujillo based on a supposed debt of gratitude.

In the 1980s, regime forces in El Salvador used Israeli napalm to bombard campesinos, and in Guatemala, software provided by Israel helped create blacklists. Later, in Colombia, Israeli agents trained far-right paramilitaries, and spymaster Rafael “Rafi” Eitan engineered the extermination of the Unión Patriotica party while holding a position at Israel’s state chemical company. As Bishara Bahbah explains in his 1986 book Israel and Latin America: The Military Connection, Israel has long used counter-insurgency consulting as a powerful incentive in its aggressive efforts to secure arms sales.

Israel’s alliance with Abinader, then, is just one more link in a long chain. Technical cooperation between the Dominican Republic and Israel began in 1962, according to historian Lucy Margarita Arraya, the same year the Kennedy Alliance for Progress and the International Development Agency, later called USAID, launched programs in the country. In December 1963, a few weeks after the U.S.-backed coup against Bosch, the Dominican Republic signed the Jerusalem Agreement on Technical Cooperation.

At the end of 2021, while inaugurating a new Israeli Embassy in Santo Domingo, the country’s ambassador highlighted the investments of Israeli capital in cybersecurity. The Dominican National Police continues to receive Israeli trainers and advisers, even though, together with the Armed Forces, the police racked up more than 3,000 executions between 2007 and March 2019, according to the report “Lethal Patrol” by journalists Tania Molina, Mariela Mejía, and Suhelis Tejero. During the Abinader government, Dominican police and military personnel have received Israeli training in areas such as anti-terrorism, cybersecurity, border security, and repression of irregular migration. The Israeli ambassador has repeatedly described the bilateral relationship as “strategic.”

In 2016, the Dominican state became one of the clients of the Israeli company NSO, acquiring the Pegasus spyware used in dozens of countries to spy on journalists, opponents, and activists. In May 2023, it came to light that Pegasus was used three times to spy on Dominican journalist Nuria Piera between 2020 and 2021, both by the government of Medina and that of Abinader. Amnesty International verified the use of Pegasus, and Piera revealed that, at the time of the attacks, she was carrying out investigations into corruption in the Armed Forces, police, and Chamber of Accounts, an auditing body.

It is not surprising, then, that Israel was tapped as the guest of honor at this year’s Santo Domingo International Book Fair. The fair was already the subject of controversy last year, when the presentation of a children’s book by a Dominican author and activist of Haitian descent, Ana Belique, was censored for racist reasons. Cultural organizations took advantage of a public consultation with the Ministry of Culture in January 2023 to reject the tribute to Israel and ask authorities to guarantee an event free of censorship, but the response was negative.

The decision to honor Israel was announced shortly after Amnesty International published a report on Israeli apartheid against the Palestinian people, echoing a characterization Palestinian organizations and academics have used to describe the Israeli occupation for decades. Amid ongoing persecution of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent, the homage to Israel also stands as an exercise in legitimizing the Dominican apartheid project itself.

Ominous Parallels

Both the Nakba or “the catastrophe” in 1948 and El Corte or “the cutting” in 1937 were breaking points—large operations of ethnic cleansing and collective expropriation that redefined the correlation of social forces in states strategically subordinated to imperialism. Israel has since applied formal territorial segregation through a system of military zoning in the Palestinian territories, building walls, checkpoints, and other repressive devices. The Dominican state applies informal territorial segregation based on socioeconomic marginalization, which is reinforced through police, military, and migratory repression, although it also deploys devices such as walls and militarization.

The Dominican state denies the provision of basic public services in many bateyes, where homes frequently lack running water and electricity. Sanitation is precarious. At the same time, in 2023, Abinader hired the Israeli state company Mekorot to develop a water management plan in the Dominican Republic. This company has played a leading role in implementing discriminatory policies that drastically limit Palestinian access to water, precisely one of the pillars of Israeli apartheid.

The parallels between these two regimes—both seeking to perpetuate the political, military, economic, and demographic supremacy of the group associated with national identity while oppressing those defined as the enemy race—are ominous. Palestinians are denied the right to protest or even carry the Palestinian flag. Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent also face severe restrictions on their right to protest, and displaying the Haitian flag generally meets repression. While Palestinians with Israeli citizenship can vote and be elected, their political participation is effectively restricted, and there are virtually no political rights in the occupied Palestinian territories. Similarly, for some Dominicans of Haitian descent, such rights are restricted. For others, they are nonexistent.

Both states take measures to limit the oppressed racial group’s population growth, including subjecting them to a systematically disadvantaged socioeconomic situation, with reduced access to natural resources and public services. This crystallizes the function of a pool of cheap labor of Palestinians, Haitians, and Dominicans of Haitian descent. Both regimes employ racial profiling and treat entire communities as “suspicious persons,” subsequently limiting their movement. Arbitrary arrests, torture, and murders by repressive agents; official permissiveness in the face of racist lynchings and violence; and impunity for ultra-right groups that play a supporting role in the repression do not, therefore, constitute “errors” or “deviations” in a democratic framework. They instead represent the execution of a regime of racial oppression.

Dominican apartheid materializes in the misery of retired sugarcane workers who languish while the government steals the social security contributions they made over decades and denies them the pensions to which they are legally entitled. This apartheid thrives in the cane, rice, coffee, and tobacco fields and on construction sites, where exploitation persists in slavery-like conditions. Dominican unions generally refuse to accept Haitian workers or defend them in conflicts with bosses and the government. The Attorney General’s office allows the racist lynchings, the burning of houses, and arbitrary actions of politics and immigration authorities to carry on unabated.

As in Israel, incitement to genocide circulates in the mainstream media in the Dominican Republic. When Haitian organizations tried to hold a march in Santo Domingo for International Migrants Day on December 18, 2018, far-right groups threatened to attack. Authorities withdrew permission for the march. When organizations denounced the threats, the country’s largest-circulation newspaper, Diario Libre, responded in an editorial: “If Haitians begin to demonstrate in the streets, and for reasons they believe noble, the situation that was experienced in Rwanda will not only appear, but will be imposed.”

Marie, the sister of Robert Gabard, holds her brother’s death certificate. Gabard died on January 24, 2023 shortly before making it back to his home in the Dominican Republic after being deported to Haiti. (SIMÓN RODRÍGUEZ)

However, there are also noticeable differences between the two contexts. More than a system of racial oppression, Israeli apartheid is also a colonial mechanism for denying the national self-determination of the Palestinian people. The problem of national self-determination does not exist in the Dominican Republic because what Dominicans of Haitian descent demand is their recognition as Dominicans. And while there is broad Palestinian resistance, which has resorted to uprisings and general strikes in the face of Israeli oppression, the protests by workers and communities of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent have not had a comparable level of reach and radicalization. However, when there have been protests, such as one led by construction workers in Ciudad Juan Bosch in May 2022 and another in Cap Cana in February 2023, they have faced fierce repression. The Dominican army has even attacked border communities in Haitian territory such as Ti Lory, where soldiers murdered two people on March 19, 2023.

The daily violence of Dominican apartheid marks the life and death of thousands of workers like Robert Gabard, who died at age 38 on January 24, 2023. At the end of last year, Gabard was detained by immigration agents, who stole his identity documents and demanded money to release him. A few weeks later, he was detained again by police officers. Not having papers and unable to pay this time, he was handed over to immigration authorities and deported.

While walking the long distances from the border to reunite with his Dominican partner and their two young children, Gabard suffered severe abdominal pain. He was admitted to a hospital in San Juan de la Maguana, where he was diagnosed with appendicitis, but not operated on. Human traffickers offered to take him to the capital for approximately $300. His family sent him cash to pay the gangsters an advance, but they stole the money, beat him, and left him for dead in an abandoned building. He was rescued by Haitian construction workers. A community leader from San Pedro de Macorís managed to locate Gabard and travel back with him. Gabard was in severe pain, probably because of his untreated condition and the internal injuries sustained in the beating. He died shortly before reaching his home. No autopsy was performed, and the death certificate states that he died of a heart attack.

“Only Dust”

“Before or after my enemies, one day lost in the future, I too will follow in your footsteps, and then they, who cursed my name and yours because I was not born with the color of snow, will know that in the house of the dead there are neither kings nor princes, nor presidents, neither rich nor poor, neither white nor black, only dust.” These are the words with which Peña Gómez closed his speech at his mother’s grave in 1982.

Decades later, Armando imagines an equality that is not that brought by the grave. Under the unrelenting sun, he has come out to protest in front of the National Congress, along with dozens of Dominican children and grandchildren of Haitians organized through the Movimiento Reconocido and other groups. It is May 23, 2023, and Armando is mobilizing for himself, for his community, and for his four-month-old daughter. The protest was not announced in advance to avoid a far-right counter-demonstration. However, from time to time, circling slowly around the protesters like a mechanical shark, there is the unmistakable yellow truck from the General Directorate of Migration.

Translated from Spanish by NACLA.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Simón Rodríguez

Simón Rodríguez is a freelance journalist and researcher based in the Dominican Republic.