Abstract

Depression is a worldwide problem requiring more research on clinically effective treatments. This study was based on a conceptualization of the self as multivoiced: constituted of multiple autonomous “I-positions.” We aimed to investigate the relational patterns between voices in patients experiencing depression, and the changes which arise through psychotherapy. Transcripts from the first, middle, and final psychotherapy sessions of five individuals treated for depression—all showing reliable improvement—were analyzed. We used the qualitative method of analyzing multivoicedness (QUAM) to identify I-positions, their relationships, and how these changed over the course of the treatment. In all cases we found two opposing I-positions which were in conflict and a third which served to suppress this conflict and limit affect. At midpoint, an emotional I-position emerged which enabled a working through of previous problematic narratives. In the last session there was an increased degree of reflexivity, which heightened the level of dialogicality between existing I-positions. These findings can be used to develop treatments that can identify inner conflict and suppression, and cultivate reflexivity in patients.

Over the past two decades, depression has been identified as the most common mental health condition worldwide (Lim et al., Citation2018). One-fifth of the population in higher income countries have been estimated affected during their lifetime (Barth et al., Citation2016). In a review of the epidemiological data, Kessler and Bromet (Citation2013) found a high risk of sustained lifelong chronic persistence. Major depressive disorder is associated with inflated risk to general health, with well-established links to a broad range of physical disorders, and significantly higher risk of early death (Carney et al., Citation2002; Cuijpers & Schoevers, Citation2004; Wulsin et al., Citation1999. van Zoonen et al., Citation2014).

“Multivoicedness,” the “plural self,” and the “multiplicities of the self” are theoretical concepts which have influenced modern psychotherapy research, providing a new lens through which a variety of mental health disorders can be researched (Hermans & Dimaggio, Citation2004). This framework stretches across a range of theoretical perspectives, including constructivist (Neimeyer, Citation2006), process experiential (Greenberg and Elliott, 2003), psychodynamic (Bromberg, Citation1996; Mihalits, Citation2015), cognitive analytic (Ryle et al., Citation2007), humanistic (Rowan & Cooper, Citation1998; Cooper, Citation2003), person-centered (Stiles, Citation1997; Osatuke et al., Citation2005), and transpersonal (Rowan, Citation2010). These frameworks are informed by the tradition of dialogism, in which the self is conceptualized as a multiplicity of interacting voices engaged in communicative interchange (Bakhtin, Citation1973).

A wide variety of terms have been used to denote these “inner voices.” An I-position has been defined as a relatively autonomous part of the self which exists in an imaginal landscape of the mind (Hermans et al., Citation1993). An example of an I-position might be I-as father or I-as student. Within this framework, the “I” has the possibility to move from one position to another dependent upon temporal, spatial, and social contexts (Hermans et al., Citation1993).

I-positions may be explicit and known to the person, or they may be implicit and operating within the dialogical space undetected by other I-positions. Implicit I-positions are considered to operate at a pre-verbal level: manifesting more as embodied felt-sensations than voices (Konopka & Zhang, 2021). For instance, an I-as vulnerable I-position may not have access to words but be represented by a physical sensation of discomfort in the chest or stomach, indicating the somatization of earlier anxiety which was experienced at a pre-verbal age (Stanley, Citation2016). Implicit I-positions may be just as dominant in directing motivation, interaction, and decision-making as explicit I-positions (Centonze et al., Citation2021).

Dysfunctional relations between I-positions have been proposed as the basis for various psychopathological conditions, including depression (Dimaggio et al., Citation2007; Lysaker et al., Citation2001; Salvatore et al., Citation2005). Researchers have suggested that impoverished dialogical abilities lead to rigid, inflexible, and unadaptable intrapersonal repertoires, often resulting in one I-position dominating the others in a “monological” fashion (Dimaggio et al., Citation2010). This creates a “dictatorship” in which certain I-positions are silenced, leaving them passive and voiceless. A disorganized, cacophonic repertoire of I-positions is also seen as leading to dysfunction as the varying I-positions vie for primacy (Lysaker & Lysaker, Citation2002).

Greenberg and Watson (Citation2006) found that the most commonly occurring feature in depression was the withdrawal and premature shutting down of emotions, accompanied by a sense of disempowerment and feelings of powerlessness: a pervasive numbing. They hypothesized that such feelings were eclipsed by a self-interrupting I-position—a part that, ultimately, is striving to play a protective function (Whelton & Elliott, Citation2019). Similarly, Stiles’s assimilation theory (Stiles et al., Citation1990; Stiles et al., Citation1991; Stiles et al., Citation1992; Stiles, Citation1997; Stiles, Citation2001) suggests that depression is a consequence of the constriction of “disowned” parts of the self, including rejected emotions (Stiles et al., Citation1990; Stiles et al., Citation1991; Stiles et al., Citation1992; Stiles., 1997). For Glick et al. (Citation2004), too, the passive stances, indecisive attitudes, and negative affect that depressed patients can experience are a result of repeated—but not fully experienced—intrapsychic conflict. They suggest that, over a sustained period, assertive, agentic voices are suppressed. This, then, can impact an individual’s self-worth, as their vitality and sense of agency are curtailed by the internal mechanism which suppress emotion (Stiles, Citation1999). Analysis of psychotherapy transcripts by Osatuke et al. (Citation2007) supported this theory, suggesting that, paradoxically, submissive voices may dominate in individuals experiencing depression. Osatuke et al.’s case study analysis concluded that a key mechanism in depression was the warding off of more assertive I-positions: voices that were experienced as problematic and threatening to the other I-positions.

The existence of submissive, self-interrupting I-positions was also detected by Ribeiro et al. (Citation2014) in a course of emotion-focused therapy for major depression. They identified a cyclical movement between two opposing I-positions, ambivalence, in which one I-position wanted change and another opposed it. Burgeoning new narratives, innovative moments, were seen as carrying the potential of change. However, in poor outcome cases these innovative moments were devalued on emergence. Poor metacognitive, reflexive abilities have also been seen as leading to more restricted communication between I-positions—and in some cases reduced conscious access to the full repertoire of I-positions (Dimaggio et al., Citation2010). Hopes of better integration between the I-positions is thwarted if the repertoire is unknown to its own members, and the ideal of reaching an inner democracy (Hermans, Citation2020)—an internal landscape which is multivoiced and fully dialogical—is rendered unfeasible. This lack of integration in the internal landscape may make integration of innovative moments more difficult as I-positions fail to collaborate and acknowledge each other and their divergent views, rejecting freshly emerging innovative ideas and or ways of being.

This research and conceptualization raise the question of how psychotherapy might aid in the acceptance of these new innovative moments. A possible solution to this problem may be to support the development of meta-positions (Hermans, et al. 2004). These are novel I-positions which, on occasion, bond to an already existing I-position and, in doing, modify it. For example, I-as in recovery may have bonded onto an original I-as addict position, as an individual enters an alcohol recovery program. Over time and over the course of treatment, I-as in recovery may become I-as recovering addict, reflecting the new contextual backdrop of the individual’s world. Meta-positions are seen as having essential metacognitive abilities: the capacity to reflect on one’s self-state from the perspective of another self-state (Osatuke et al., Citation2011). Dimaggio et al. (Citation2010) suggested that newly formed meta-positions could come to the aid of rejected, ostracized, and subversive I-positions; advocating for these more marginalized voices.

However, whilst there is general agreement that improved communication between the I-positions and the development of meta-positions is a therapeutic goal, there is little research that explores this idea in practice. In part, this is due to the implicit nature of I-positions and the consequent methodological challenges of exploring these with self-report methods. To overcome this challenge, the present research used a new technique, the qualitative method of analyzing multivoicedness (QUAM) (Aveling et al., Citation2015; Kay et al., 2020), to examine the interactions between I-positions, and the changes which arise through psychotherapy, in the internal dynamic system in patients experiencing depression. We aimed to explore how I-positions relate to one another and to examine, longitudinally, what patterns of dominance, adaptation, and evolution were occurring across treatments—both successful and unsuccessful.

Method

Design

This mixed methods study fits within the overarching domain of theory-building research (Stiles, 2007). Stiles suggests that observations have the capacity to change theories in a confirming or disconfirming way, and that this may result in the strengthening or a weakening of a theory. Theory building research can refine, modify, or extend a theory through the permeation of fresh observations. Our mixed methods approach extends the original QUAM methodology by adding a quantitative component. Specifically, we used QUAM to identify all the I-positions in each case, and then we quantified these in order to identify robust longitudinal changes in the pattern of I-positions.

Data for this study was transcripts from audio-recorded psychotherapy sessions at a university-based research clinic where patients participated in up to 24 weekly sessions of pluralistic therapy for depression (Cooper & McLeod, Citation2007, 2011; McLeod & Cooper, Citation2011). Informed consent was obtained in the clinic for the use of recordings, and ethical approval was given by the respective university ethics committee. We analyzed five individual cases at the beginning, middle, and end sessions of their treatment using the QUAM. This number of participants was selected as sufficient to provide enough variability for analysis purposes while also being a manageable amount of data to conduct an in-depth dialogical analysis on.

Participants

Three of the five participants self-identified as male and two as female. Their ages ranged from 20 to 30. All five participants described themselves as being of central European ethnicity. Eligibility criteria for participants were that they met criteria for depression, as assessed by a score of ten or greater, on the Personal Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) measure of depression (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) and were deemed to be clinically recovered at the end of treatment. All participants had completed at least 23 weeks of a 24-week course of psychotherapy.

Psychotherapists

The five cases had four psychotherapists (with one of the psychotherapists working with two patients). Three of the psychotherapists self-identified as female and one as male. The psychotherapists’ ages ranged from 28 to 48. All of the psychotherapists were in the final year of a doctoral training in counseling psychology. This program focused on the development of skills in person-centered, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral practices, within an assimilative integrative framework.

Pluralistic therapy for depression

Pluralistic therapy for depression is a manualized, collaborative–integrative psychotherapy (Cooper & McLeod, Citation2007, 2011; McLeod & Cooper, 2012). It consists of one 90-minute assessment session followed by up to 24 sessions of one-to-one therapy. In this treatment, the psychotherapist draws on a range of established treatment methods (e.g., Rogerian active listening, Socratic dialogue, exploration of early childhood experiences) with the aim of tailoring the intervention to the specific goals and preferences of the client. The approach is structured around metatherapeutic communication (Papayianni & Cooper, 2017): moments of shared decision-making in which psychotherapist and client agree on the particular tasks, goals, and methods of the work.

Measures

The PHQ-9 is a brief self-report measure for detecting severity of depression symptoms in a general population. Respondents are asked to rate how bothered they have been by a range of problems over the last two weeks, such as “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” There are nine items, and responses are given on a four-point Likert Scale from Not at all (0) to Nearly every day (3). Scores are totaled, and severity of depression is rated as “none” (0–4), “mild” (5–9), “moderate” (10–14), “moderately severe” (15–19), or “severe” (20–27). The PHQ-9 has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89), good test-retest reliability (r = .84) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001), and good convergent validity against the SF-20 mental health subscale (r = 0.73).

Analysis

All psychotherapy sessions were audio recorded, listened to by the first author several times, then transcribed. The verbatim transcription included sighs, pauses, laughter, and a variety of other non-verbal sounds.

QUAM was developed to identify the I-positions within an individual’s talk (Aveling et al., Citation2015). It enables an exploration of the internal I-positions and how they interact with each other and within the individual. It also maps the “external I-positions of the individual,” and how these interact with internal I-positions within the individual’s speech. External I-positions are defined as the voices of Others which reside within the self. They represent real individuals (e.g., husband, manager) and may also include generalized Others (e.g., local community) or discourses associated with specific institutions and societal groups. A full account of the QUAM method as applied to psychotherapy research is given in Kay et al. (2020).

Stage one

This initial stage focused on the I-positions that the “self” was speaking from. Within each individual transcript, text units were identified in which the patient had: used first person pronouns (singular and plural), spoke on the behalf of a group or institution, or used first person possessives such as “my” or “our.” We then identified the beginnings and ending of coding segments by a shift in the perception of the speaker. These shifts were often punctuated by the use of “gear change-type” utterances such as “but,” “however,” or “although.” They were also often accompanied by a shift in vocal tone. Segments which appeared to emanate from the same I-position were then grouped together under an appropriate label, such as I-as autonomous or I-as responsible.

Stage two

This stage focused on detecting the voices of external Others (i.e., external I-positions). This task was undertaken by coding all speech with actual named Others or third person pronouns or possessives. Direct quotations, involving the explicit representation of the words of an Other, were coded in this way. Indirect quotations were also coded here, as more generalized way of reporting the views of others with phrases such as “they” or “most people.” The interpersonal origins of these indirect quotations were also determined at this stage. Subsequently, a reference list of Others and their coded utterances, alongside a brief characterization, was created. This was then used to search for more implicit representation of external I-positions which may be present in the form of “echoes” in the speech (Aveling et al., Citation2015).

Stage three

Stage three involved an analysis of the interaction between all the internal and external I-positions identified. A table was drawn up which presented all the I-positions and example utterances, along with a brief characterization. The interactions between I-positions, internal and external, were then analyzed. We looked at the local context around each I-position, including proximity to other I-positions and how they were situated in the data, examining closely the transcripts and listening to the audio recordings. Across all transcripts we observed the quality of the relations between I-positions, and considered the dynamic interactional patterns which occurred. Particular attention was paid to the power dynamic between I-positions and what one I-position was “doing” to another. This stage also involved an analysis of dialogical knots (Aveling et al., Citation2015): conflicting points or tensions within the dialogue. In part, these were identified through a sudden switching of one I-position to another.

Stage four

A new stage was added to QUAM in this study, in which we analyzed the data longitudinally and quantitatively. We mapped the I-positions and their interactions over the three time points. This involved counting the frequency of existing and emerging I-positions and examining what changes occurred over time, with a particular focus on which I-positions were dominant at each time point. For the purposes of this study, we defined dominance in terms of the power and control that an I-position had over other I-positions in the repertoire: a dominant I-position was seen as taking center stage in that moment in time as others were relegated backstage. This dominance was not always reflected in how long an I-position was present for. For example, a harsh, critical I-position could dominate more marginalized, vulnerable I-positions, but may be front stage for less of the time. Our assessment of dominance, therefore, relied on qualitative, analytical judgment.

Cross case quantitative analysis

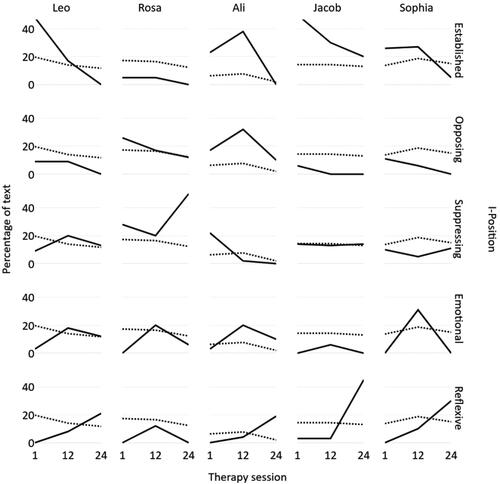

As indicated above, our QUAM also involved a quantitative assessment of the prevalence of patients’ I-positions at each time point. We did this by counting the number of times in which a distinct I-position manifested in the session: how often they were identified as emerging, reemerging, and speaking in the session. These calculations were then converted to percentages, and we created a visual graph to analyze the changes in I-positions across treatment and in relation to the patients’ PHQ-9 scores (see ). The numerator for the percentages was the number of text units that were identified with a specific I-position in a session, and the denominator was the number of text units coded as pertaining to all I-positions in that session.

Case sample: Leo

Along with our cross-case analysis, we chose to present a detailed, individual case study: Leo. This provides a clear illustration of the dynamic interactional pattern which, from our QUAM, seemed to sustain depression, and which was modified through psychotherapy. Leo was a 23 year old male of central European ethnicity who was in the final year of his postgraduate studies. At assessment, Leo scored 23 on the PHQ-9, indicating severe depression. Leo’s initial goals for psychotherapy were to be able to understand himself better, particularly in the area of interpersonal relations, and to improve his self-esteem and self-confidence.

Results

Cross-case analysis

An overview of the cross-case QUAM is provided by and . In the rows are the five cases, the columns are the I-positions, and the cells provide illustrative quotes for each I-position. This gives a qualitative sense of the content of the I-positions for each case. shows changes in the prevalence of the identified I-position across the therapy sessions, against the background of PHQ-9 depression scores.

Table 1. Identified I-positions and interactional patterns for all participants.

Across all cases, at session one, a conflictual pattern between two opposing I-positions was identified. These I-positions were labeled established and oppositional. In Ali’s case, for instance, an I-position that felt responsible for the family opposed another which desired autonomy. In Rosa’s case conflict existed between an I-position which felt embedded in a “proper family” and another which was vigilantly protecting Rosa from members within that family. Sophia engaged with medical professionals as a vulnerable ill patient in one I-position, but presented to friends and family as “everything’s perfect” in another. In one I-position, Jacob anxiously monitored himself, maintaining a vigil to keep himself under control, but in another he craved and then binge ate.

Across all cases, the affect which arose as a result of the opposing views, wants, and desires of these conflicting I-positions was then suppressed by a third I-position. We termed these suppressive I-positions. Ali’s cynic I-position, for instance, shut down emotion with its “righteous” anger, taking the higher moral ground, and attempting to render Ali’s inner conflict as irrelevant. Sophia in the I-as hopeless shutdown I-position withdrew from life and relationships altogether, explaining to the psychotherapist that everything “stops.” This curtailed her need to interact with the world, thereby avoiding conflict with others. In Rosa’s case the affect was halted by trying to eradicate herself from the world, entering a repeated narrative of how she “shouldn’t exist.” This narrative of self-blame enabled Rosa to remove her right to any emotional reactions, hence suppressing those reactions. With Jacob, the powerful conflict he experienced was suppressed by believing in bad luck: a feeling of being under a spell or curse which rendered hopeless his internal struggles. He described ghosts from the past that “won’t bloody leave me alone.”

By midpoint, as illustrated in , all patients expressed more emotion during the session. This seemed to be enabled by an emotional I-position: peaking at mid-point in all cases. It was at this stage of psychotherapy, for instance, that Leo shared his feelings of sadness in the I-as helpless I-position. Rosa expressed her rage at others in an I-as wronged I-position. Jacob lamented on how repulsed he was at himself in the I-as craving I-position, filled with self-disgust and remorse. Sophia explained the angry outbursts she had, of late, experienced with others in the I-as wronged and angry I-position. Ali, whilst in the emotional I-position of I-as self-doubt, described how vulnerable he felt whilst sitting with his own sense of uncertainty when faced with choices in life.

By endpoint, as illustrated in , four out of the five patients had demonstrated a new reflexive I-position and, except for Rosa, this was most prevalent in the last session. This I-position had a capacity for deep introspection and the ability to think about the patient’s own thinking and the thinking and intentions of others. This seemed to be a meta-position that had developed over the course of the psychotherapy process. The trajectory of the reflexive I-position, as illustrated in , increased from 0% to over 20% of all the voiced I-positions in four of the five cases, with minimal prevalence at the beginning, then steady growth by midpoint.

The reflexive I-position manifested differently for each participant. Ali, for instance, talked about a newfound sense of integration, of being “open” with others in the I-as exciting future I-position. Sophia in the I-as person in recovery I-position was reflexive and described how she had paused to consider how the past had led her into certain situations. Similarly, Jacob in the I-as vulnerable I-position was exploring past experiences and reflecting on how they had shaped him.

Rosa was the exception to the pattern of increased reflexive I-positions. Instead, a monological pattern was identified which was dominated by the suppressive I-position, I-as shouldn’t exist. Rosa’s suppressive I-position occupied 50% of her talk by endpoint: the highest measurement of any I-position detected in any session across all cases. As this increased, her emotional I-position, decreased from 20% to 6%. In Rosa’s case the last session revealed a possible return to a problematically entrenched pattern, one of intrapersonal domination by the suppressive I-position. This seemed create an impoverished dialogical landscape.

Across our sample, there were indications of a negative association between the prevalence of reflexive I-positions and levels of PHQ-9 depressive symptoms. That is, as Leo’s, Ali’s, Jacob’s, and Sophia’s reflexive I-positions emerged and became most prevalent, so levels of depression tended to reduce. By contrast, Rosa, whose reflexive I-position did not increase in prevalence, showed stable levels of depressive symptoms across treatment. Our more successful cases also tended to show a reduction or maintenance of suppressive I-positions; with Rosa, our poorer outcome case, showing a considerable increase in suppressive I-position by endpoint.

Case illustration: Leo

Leo was an exemplar of the processes identified, above. Leo had the largest drop in the prevalence of his opposing I-position: from 48% in session one, to 17% in session 12, and finally 0% at endpoint. In addition, at midpoint, there was increased prevalence of the emotional I-position: an increase of 15% from the first session to 18%. Leo also had a large increase in his reflexive I-position: from 8% at midpoint to 21% at endpoint. Leo’s case is also exemplar in terms of having the largest reduction in PHQ-9 scores: from an average of 19.7 in the first three sessions to 11.7 for the last three.

Initial session

The two opposing I-positions in Leo’s case were labeled as I-as ill patient (established) and I-as disgusted (opposing). The I-as ill patient position presented what Leo considered a needy, dysfunctional part. By contrast, I-as disgusted represented a part that had no tolerance of any perceived inadequacies. This, latter I-position was powerful in shaping the interaction and managed to direct the conversation effectively, sustaining tension with the established I-position.

In the early stage of the psychotherapy process, Leo seemed to have little ability to create helpful dialogue between these two I-positions, with either one or the other dominating. Also identified at this early stage was a third I-position, labeled I-as defensive. This was the suppressive I-position which seemed to flatten out the conflict generated between the established and opposing I-positions.

Midpoint

At midpoint a new, emotional I-position became much more prominent, labeled I-as helpless. This I-position, spoken in a barely audible whisper, was associated with the release of a small amount of affect. Shortly after its utterances, however, it was silenced by the I-as defensive position (Excerpt 1).

Excerpt 1. Midpoint dialogue between Leo and Psychotherapist.

In Excerpt 1, Leo’s affect emerged as he shared his feelings of hurt as a female friend started a romantic relationship with someone else. There is a glimpse of the I-as helpless position as he acknowledges his emotional response. Quite suddenly, however, this is shut down by the I-as defensive suppressive I-position, preventing the experience of further emotion being felt or focused upon during the session. Excerpt 1 shows, however, that Leo was becoming more able to identify, and explain to the psychotherapist, the strategies which he has historically deployed for managing the emergence of difficult emotions. This new capacity for self-reflection could be construed as the early signs of a new, reflexive I-position.

Endpoint

At endpoint there was a significant shift in the configuration of Leo’s I-positions. The oppositional I-positions (I-as ill patient and I-as disgusted) were absent. I-as defensive (the suppressive I-position) was still present but to a lesser degree as was I-as helpless (the emotional I-position). A burgeoning new reflexive I-position, I-as complicated, dominated the session, reflecting on how he had changed over the course of psychotherapy. This showed his ability to mentalize about himself and the psychotherapist.

Excerpt 2. Endpoint dialogue between Leo and Psychotherapist.

In Excerpt 2, the psychotherapist was exploring how Leo conceptualized his own process over the course of the 24 weeks. Leo used the phrase “you and I both know,” clearly indicating his perception of a shared discovery, and construction of knowledge, during the psychotherapy process. This also suggested a feeling of shared intimacy, alluding to how he felt the psychotherapist knew him in this specific I-as complicated I-position. Leo then also used the phrase “we’ve worked” which again suggests how, through interaction with the psychotherapist, Leo has taken in their shared language. That is, Leo’s use of the pronouns “we” and “we’ve” seemed to indicate that he had incorporated the inner-Other of the psychotherapist. Leo seemed to be using the psychotherapist as an external I-position or inner-Other, to reflect on the other I-positions in the internal landscape.

At endpoint, Leo shows evidence of developing a more reflexive self-inquiring stance, with a growing sense of curiosity and introspection in the I-as complicated I-position. The psychotherapist encouraged him to explain more, to explore further, and reflect on himself on a deeper level. It is possible that such encouragement had enabled the new I-as complicated individual position to form. The internalization of such psychotherapist’s utterances had, possibly, enabled Leo to contemplate his own complexity and, potentially, to move toward more of an acceptance of it. Leo’s capacity for thinking about his thinking appeared to be a burgeoning meta-position: one that could view and conceptualize the whole repertoire of I-positions.

Discussion

In contrast to Osatuke et al. (Citation2007), our research suggests that it was not the incompatibility between the two opposing I-positions which was associated with depression, but the inability to tolerate the inner conflict created by these oppositional I-positions. Freud (1909) first drew attention to the role intrapsychic conflict played in the creation of neurosis, postulating that different aspects of the self vied within for different interests, sometimes creating intolerable conflict as a result. The inability to tolerate these levels of internal conflict was seen as leading to the deployment of defense mechanisms whose function was to find compromise between these conflicting forces (Holmes, Citation1994). From a relational psychoanalytic perspective, Bromberg (2011) concurred with Freud regarding the divergent needs which different aspects of the self contained. The manifestation of this divergence during the therapy process can lead to what Bromberg describes as “self-state switch”; for example, a “not me” part previously existing dissociatively may come online and dominate, presenting an opposing view from a previous part. Bromberg argues that this part which is now participating was present previously but in a dissociated “not me” self-state. It then becomes activated and deploys a defensive stance to protect itself as it feels under threat from developments in the psychotherapy process. These theoretical ideas regarding conflict and suppression are helpful to consider in relation to the dynamic pattern we identified in this study, particularly when we consider the manifestation of what we consider to be depression: the deployment of a suppressing I-position which dominates and prevents integration and innovation in the intra-psychic landscape.

More recently models of psychotherapy such as interpersonal therapy and dynamic interpersonal therapy (DIT) have been designed to work with patients who experience depression (Klerman et al., Citation1994; Lemma et al., Citation2011). These models have a strong focus on the role interpersonal relations play in the maintenance of depression. DIT particularly draws on Blatt’s proposed distinction between two forms of depression (Citation1974; Blatt & Maroudas, Citation1992) the antecedents of which derive from interpersonal relations with others in the developmental years. These are anaclitic depression, where the individual is dominated by interpersonal issues relating to feelings of abandonment, loss, dependency, and helplessness; and introjective depression, where the individual is dominated by self-criticism, fears of failure and guilt, and issues of self-worth. If we consider the suppression I-positions we identified in this study—I-as defensive, I-as cynic, I-as hopeless shutdown, I-as cursed, and I-as shouldn’t exist—they could be categorized as fitting well within both anaclitic and introjective domains. These suppressive I-positions could be understood as being constituted out of problematic relational dynamics with others, and being the resulting residue of these interpersonal dynamics. The personification and labeling of suppressive I-positions during psychotherapy in a collaborative process between psychotherapist and patient could prove helpful, and may aid self-reflection and enhance metacognitive abilities as the patient thinks about their own thinking.

Our findings are also consistent with theory and evidence from emotion-focused therapy: that emotional I-positions are suppressed in individuals with depression and that this, in itself, creates an apathetic sense of powerlessness which then comes to dominate (Greenberg & Watson, Citation2006; Whelton & Elliott, Citation2019). Our findings also resonate with the idea of a “self-interrupting part” (Greenberg et al., 1996): an I-position in severely depressed individuals which acts to shut down access to expressive feelings, thoughts, and actions. It is also chimes with the findings of Stiles (Citation1999) that a suppressing I-position shuts down emotional needs of opposing I-positions, flattening affect and ceasing their ongoing conflict. To maintain this “stalemate”—with the suppressive I-position dominant—certain narratives may be utilized and worn like “protective garments” to maintain the status quo: leading to the patient in sessions being ambivalent toward change (Oliveira et al., Citation2016, Braga et al., Citation2018). In Leo’s case, these narratives involved others who immobilized him and suppressed his sense of agency in the world. This return to a problematic narrative has been well documented in innovative moments research (Goncalves et al., 2018).

These findings raise the question of how psychotherapy can facilitate the emergence of new adaptive and reflexive I-positions to release restricted emotions. In our analysis the release in affect seemed to peak around the midpoint, as is illustrated in . Here, we also noted a rise in PHQ-9 scores in some cases at this point: illustrating, perhaps, that the release of emotion could also elicit depressive symptoms. In releasing constricted emotion in the sessions an emotional I-position may have provided an outlet for the pent-up affect to be discharged, this process was often closely followed by a growth in the reflexive I-position (and a lowering of the PHQ-9 score). This finding is resonant with results concerning depression and the importance of processing emotions from Angus et al. (Citation2013). Angus et al.’s research found that, in order to stimulate reflexivity, patients’ emotions needed to be understood or “got in touch with.” Processing of emergent and adaptive emotions were described as central to facilitating psychological change and achieving recovery (Angus et al., Citation2017).

Taking these research findings into consideration through a dialogical lens, it is possible to suggest that experiencing emotion—in the form of emotional I-positions manifested in psychotherapy—may enable subsequent growth in reflexive capacity, as what was felt by one I-position is then reflected upon by another. Reflexive capacity is essential for the development of metacognitive abilities (Wells, Citation2011). Dimaggio et al. (2004; Citation2010) suggests it is an important aspect of psychotherapy when considering relations between I-positions and their ability to engage in dialogue. They theorize that it is essential to encourage the I-positions to engage with one another: to argue, negotiate, build upon, concur with, and discuss more fully their differing opinions, needs, wants, and desires. The metacognitive qualities needed for this entail an ability for one I-position to be aware of, and to reflect on, another. This ability was observed in what we termed the reflexive I-position, which was prevalent at endpoint in four of our five cases. The reflexive I-positions could be understood as meta-positions (Hermans, et al. 2004) that advocate for marginalized and rejected I-positions: those previously denied consideration within the repertoire. The burgeoning reflexive I-positions, associated with reductions in depressive symptoms, seemed to be fostered by the growth of the emotional I-positions, which may facilitate an increase in the breadth of dialogicality, leading to further integration.

In Rosa’s case—whose PHQ-9 score at endpoint was still in the “moderate depression” range—the reflexive I-position, which was glimpsed at midpoint, was no longer detected at endpoint. Analysis of this case at endpoint revealed what Lysaker and Lysaker (Citation2002) described as a monological internal configuration. Here, dialogical capacity was extremely reduced and the world remained constructed in a singular manner. The constellation of I-positions here enabled the creation of a consistent story, but it was a concrete narrative which would, in the words of Hermans (Citation2006), “resist any evolution and cease to provide a basis for shared understanding” (p. 8). Rosa’s suppressive I-position, I-as shouldn’t exist, took center stage, appearing more entrenched, rigid, and powerful than in the previous sessions. Considering the contrast between this case and the other four, it may be that this monological organization and absence of dialogue between I-positions, coupled with the dominance of the suppressive I-position, can be understood as hindering reflexive growth and the development of a meta-position. This supports Dimaggio et al. (Citation2010) suggestion that impoverished dialogical communication between I-positions contributes to an individual’s inability to construct an integrated view of themselves. Interestingly, in Rosa’s case, there appeared to be a rupture in the therapeutic relationship. This occurred somewhere between the midpoint and endpoint of the sessions. This rupture may have prevented the evolution of newer, more adaptive I-positions, and paved the way for the dominance of the suppressive I-position. This is because the relational dynamics with the psychotherapist resonated with the problematic interpersonal relationships Rosa had discussed in the sessions. It is possible that this, then, generated more intra-psychic conflict which needed to be suppressed.

The growth in reflexive capacity that we observed appeared to be driven, in part, by the internalization of the utterances of the psychotherapist: as external I-positions or inner-Others. In our analysis, we logged external I-positions in the client’s utterances “echoes” and “ventriloquated” speech (Aveling et al., Citation2015). Many examples of echoes from the psychotherapist were coded across cases. In Leo’s case the use of the words “we” and “we’ve” provide a good example. As Leo reflected on newly found meaning in his utterances he included the psychotherapist. In these utterances, Leo brought his psychotherapist into his process: not only in the use of “we” but also the shared understanding and newly grown meaning which he elaborated on. This appeared to be a reciprocated process as the psychotherapist then echoed back to him “there’s a lot more to you than we could cover in this amount of time.” In this sense, the complexity of the inner repertoire was co-owned, collaboratively acknowledged, and respected by both parties in the psychotherapeutic dialogue.

This detection of the language of the external I-position of the psychotherapist raises the question of whether this is beneficial to the client and, if so, how psychotherapy might facilitate this internalization process. The internalization of the psychotherapist has been linked previously to positive outcomes in psychotherapy (Blatt et al. 1997; Dorpat, Citation1974; Mitchell, 1988). Geller et al. (Citation2005) hypothesized that processes of internalization become more effective when informed by an empathic awareness of the nature of the client’s psychological boundaries: the network of intrapersonal processes which represent various domains of experience. These intrapersonal processes could be understood as the relations between external I-positions and internal I-positions. Hence, we can hypothesize that offering empathy to all I-positions may encourage each of them to be manifest, and thereby open to transformation during the psychotherapy process.

Consistent with this, Stiles (Citation1999) suggests that change processes in psychotherapy entail the “injection of new schemata” into a patient via the psychotherapist. Other researchers concur that to elicit change processes there needs to be space in the client’s intrapersonal landscape for them to take in what the psychotherapist is offering (Konopka & Van Beers, Citation2014; Moroika, 2018). Another way to understand these changes is that the internalized psychotherapist, in the form of a burgeoning external I-position, becomes bonded to an already existing I-position Hermans et al., 2004). This strengthens the external I-position’s abilities within the repertoire, as it becomes a hybridized version of its previous self, incorporating a growth in reflexive capacity and willingness to engage in dialogue with other I-positions. In Leo’s case this process may have been evident in his accepting of his own “complicatedness.” The utterances of the psychotherapist conveyed genuine interest, curiosity, and respect to this I-position, modeling, to Leo, a way of being “with” that voice.

Analyzing the cases in this study at three distinct time points revealed changes in the relative prevalence of I-positions. Considering Leo, at the midpoint as illustrated in , slivers of emotion were released in the I-as helpless I-position, and there were signs that this served as an emotional outlet. However, the dominant I-position was still I-as defensive—the suppressive I-position or “self-inhibiting part”—which blocked this affect shortly after its expression (Greenberg et al., 1993).

There are several limitations to this research. First, the restriction which existed in only analyzing sessions at three time points: beginning, middle, and end. This means that we may have missed the ongoing development of I-positions. With Leo, for instance, it is quite possible that between sessions 12 and 24 his burgeoning emotional I-position became more prominent, developing in the light of ongoing interactions with his psychotherapist. Another limitation is the small size of the sample, which makes generalizations difficult. However, it should be noted that the extant research in the field of qualitative dialogical analysis is predominantly only single case-based—this being due to the micro-analytic detail which is involved in the analysis process. Hence, at minimum, our comparison of five case studies have enabled us to reveal both commonalities and differences across cases. There is also a limitation regarding QUAM regarding the subjective decision-making process that shapes the labeling of I-positions. This limitation has been observed in other forms of qualitative research (Hill, Citation2012) and one proposed solution may be to engage in a consensual approach to the data at the early stages of the coding process. This process was adopted by Osatuke et al. (Citation2005) when analyzing multivoicedness: a group of researchers collaborated to reach consensus over the coding process. We suggest that this approach could be utilized in further QUAM research and could be conceived of as a way of testing inter-rater reliability.

Through this in-depth, longitudinal dialogical analysis we have identified patterns in how the interaction between I-positions may contribute to the maintenance of depression. Our findings suggest that growth in reflexive capacity may strengthen the possibility of the development of a hybridized meta-position for the patient. We suggest this may contribute to change in the intrapersonal repertoire of I-positions, as one I-position is able to think, negotiate, collaborate, and more profoundly accept another despite their differences. Further research should examine this internalization, in particular the process where one I-position is hybridized through bonding or fuzing with another. This research may be in relation to differing theoretical models, in order to understand how the process varies, if at all, when considering ways of working with, and understandings of, the therapeutic relationship. For further research, it may be useful to apply QUAM to different disorders. There is a wealth of research concerning depression, but less with other clinical populations. This research has revealed the dynamic patterns between voices in individuals who experience depression and has illuminated, through a dialogical analysis, how the facilitation of adaptive and reflexive I-positions may facilitate therapeutic change.

References

- Angus, L. E., & Kagan, F. (2013). Assessing client self-narrative change in emotion-focused therapy of depression: An intensive single case analysis. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 50(4), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033358

- Angus, L. E., Boritz, T., Bryntwick, E., Carpenter, N., Macaulay, C., & Khattra, J. (2017). The Narrative-Emotion Process Coding System 2.0: A multi-methodological approach to identifying and assessing narrative-emotion process markers in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 27(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1238525

- Aveling, E. L., Gillespie, A., & Cornish, F. (2015). A qualitative method for analysing multivoicedness. Qualitative Research: QR, 15(6), 670–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114557991

- Bakhtin, M. (1973). Problems of Doestoevsky’s poetics. (R. W. Rostel, Trans. 2nd ed.). Ardis.

- Barth, J., Munder, T., Gerger, H., Nüesch, E., Trelle, S., Znoj, H., Jüni, P., & Cuijpers, P. (2016). Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 14(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.140201

- Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29(1), 107–157.

- Blatt, S. J., & Maroudas, C. (1992). Convergences among psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioral theories of depression. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 9(2), 157.

- Blatt, S. J., & Behrends, R. S. (1987). Internalization, separation-individuation, and the nature of therapeutic action. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 68, 279–297.

- Braga, C., Oliveira, J. T., Ribeiro, A. P., & Gonçalves, M. M. (2018). Ambivalence resolution in emotion-focused therapy: The successful case of Sarah. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 28(3), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1169331

- Bromberg, P. M. (1996). Standing in the spaces: The multiplicity of self and the psychoanalytic relationship. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 32(4), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1996.10746334

- Bromberg, P. M. (2012). The shadow of the tsunami: And the growth of the relational mind. Routledge.

- Carney, R. M., Freedland, K. E., Miller, G. E., & Jaffe, A. S. (2002). Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: A review of potential mechanisms. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(4), 897–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00311-2

- Centonze, A., Inchausti, F., MacBeth, A., & Dimaggio, G. (2021). Changing embodied dialogical patterns in metacognitive interpersonal therapy. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 34(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2020.1717117

- Cooper, M. (2003). II" and" I-ME": Transposing Buber’s interpersonal attitudes to the intrapersonal plane. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 16(2), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530390117911

- Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2007). A pluralistic framework for counselling and psychotherapy: Implications for research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7(3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140701566282

- Cuijpers, P., & Schoevers, R. A. (2004). Increased mortality in depressive disorders: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 6(6), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-004-0007-y

- Dorpat, T. L. (1974). Internalization of the patient-analyst relationship in patients with narcissistic disorders. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 55(2), 183–191.

- Ebert, D. D., Buntrock, C., Reins, J. A., Zimmermann, J., & Cuijpers, P. (2018). Efficacy and moderators of psychological interventions in treating subclinical symptoms of depression and preventing major depressive disorder onsets: Protocol for an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open, 8(3), e018582. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018582

- Dimaggio, G., & Stiles, W. B. (2007). Psychotherapy in the light of internal multiplicity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20335

- Dimaggio, G., Hermans, H. J., & Lysaker, P. H. (2010). Health and adaptation in a multiple self: The role of absence of dialogue and poor metacognition in clinical populations. Theory & Psychology, 20(3), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354310363319

- Freud, S. (1957). The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XI (1910): Five lectures on psycho-analysis, Leonardo da Vinci and Other Works (pp. 139–152).

- Geller, J. D., Geller, J. D., Norcross, J. C., & Orlinsky, D. E. (2005). Boundaries and internalization in the psychotherapy of psychotherapists. The Psychotherapist’s Own Psychotherapy: Patient and Clinician Perspectives, 379–404.

- Glick, M. J., Osatuke, K., & Stiles, W. B (2004). Encounters between internal voices generate emotion: An elaboration of the assimilation model. In Hermans (Ed.), The dialogical self in psychotherapy (pp. 107–123). Routledge.

- Gonçalves, M. M., Ribeiro, A. P., Rosa, C., Silva, J. R., Braga, C., Magalhães, C., & Oliveira, J. T. (2018). Innovation and ambivalence: A narrative-dialogical perspective on therapeutic change. In Handbook of dialogical self theory and psychotherapy (pp. 120–134). Routledge.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2006). Emotion-focused therapy for depression. American Psychological Association.

- Hermans, H. J., Rijks, T. I., & Kempen, H. J. (1993). Imaginal dialogues in the self: Theory and method. Journal of Personality, 61(2), 207–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1993.tb01032.x

- Hermans, H. J., & Dimaggio, G. (2004). The dialogical self in psychotherapy. In The dialogical self in psychotherapy (pp. 17–26). Routledge.

- Hermans, H. J. (2006). The self as a theatre of voices: Disorganization and reorganization of a position repertoire. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530500508779

- Hermans, H. J. (2020). Inner democracy: Empowering the mind against a polarizing society. Oxford University Press.

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. American Psychological Association.

- Holmes, J. (1994). Brief dynamic psychotherapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 1(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.1.1.9

- Kay, E., Gillespie, A., & Cooper, M. (2021). Application of the qualitative method of analyzing multivoicedness to psychotherapy research: The case of “Josh. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 34(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2020.1717145

- Kessler, R. C., & Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-0319-11409

- Klerman, G. L., & Weissman, M. M. (1994). Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression: A brief, focused, specific strategy. Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

- Konopka, A., & Van Beers, W. (2014). Composition work: A method for self-investigation. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 27(3), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2014.904703

- Konopka, A., & Zhang, H. (2020). Including the ‘unspeakable’ in the democracy of the self: Accessing implicit I-positions in composition work. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 34(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2020.1717148

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Lemma, A., Target, M., & Fonagy, P. (2011). Brief dynamic interpersonal therapy: A clinician’s guide. OUP Oxford.

- Lim, G. Y., Tam, W. W., Lu, Y., Ho, C. S., Zhang, M. W., & Ho, R. C. (2018). Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x

- Lysaker, P. H., Lysaker, J. T., & Lysaker, J. T. (2001). Schizophrenia and the collapse of the dialogical self: Recovery, narrative and psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(3), 252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.3.252

- Lysaker, P. H., & Lysaker, J. T. (2002). Narrative structure in psychosis: Schizophrenia and disruptions in the dialogical self. Theory & Psychology, 12(2), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354302012002630

- McLeod, J., & Cooper, M. (2011). A protocol for systematic case study research in pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy. Counselling Psychology Review-British Psychological Society, 26(4), 47–58.

- Mihalits, D. S. (2015). Voices in between: Cultural interchange in dynamic psychotherapy. Culture & Psychology, 21(1), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X14561241

- Mitchell, S. A. (2009). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis. Harvard University Press.

- Morioka, M. (2018). 14 On the constitution of self-experience in the psychotherapeutic dialogue. In A. Konopka, H. J. Hermans, & M. M. Gonçalves (Eds.), Handbook of dialogical self theory and psychotherapy: Bridging psychotherapeutic and cultural traditions (pp. 206–219). Routledge.

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Narrating the dialogical self: Toward an expanded toolbox for the counselling psychologist. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(01), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070600655205

- Oliveira, J. T., Gonçalves, M. M., Braga, C., & Ribeiro, A. P. (2016). How to deal with ambivalence in psychotherapy: A conceptual model for case formulation. Revista de Psicoterapia, 27(104), 119–137.

- Osatuke, K., Humphreys, C. L., Glick, M. J., Graff‐Reed, R. L., Mack, L. M., & Stiles, W. B. (2005). Vocal manifestations of internal multiplicity: Mary’s voices. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 78(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608304X22364

- Osatuke, K., Mosher, J. K., Goldsmith, J. Z., Stiles, W. B., Shapiro, D. A., Hardy, G. E., & Barkham, M. (2007). Submissive voices dominate in depression: Assimilation analysis of a helpful session. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20338

- Osatuke, K., Stiles, W. B., Barkham, M., Hardy, G. E., & Shapiro, D. A. (2011). Relationship between mental states in depression: The assimilation model perspective. Psychiatry Research, 190(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.001

- Papayianni, F., & Cooper, M. (2018). Metatherapeutic communication: An exploratory analysis of therapist-reported moments of dialogue regarding the nature of the therapeutic work. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1305098

- Ribeiro, A. P., Mendes, I., Stiles, W. B., Angus, L., Sousa, I., & Gonçalves, M. M. (2014). Ambivalence in emotion-focused therapy for depression: The maintenance of problematically dominant self-narratives. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 702–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.879620

- Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. (1996). Facilitating emotional change: The moment-by-moment process. Guilford Press.

- Rowan, J., & Cooper, M. (1998). The plural self: Multiplicity in everyday life. Sage.

- Rowan, J. (2010). Personification: Using the dialogical self in psychotherapy and counselling. Routledge.

- Ryle, A., & Fawkes, L. (2007). Multiplicity of selves and others: Cognitive analytic therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20339

- Salvatore, G., Nicolò, G., & Dimaggio, G. (2005). Impoverished dialogical relationship patterns in paranoid personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2005.59.3.247

- Stanley, S. (2016). Relational and body-centered practices for healing trauma: Lifting the burdens of the past. Routledge.

- Stiles, W. B., Elliott, R., Llewelyn, S. P., Firth-Cozens, J. A., Margison, F. R., Shapiro, D. A., & Hardy, G. (1990). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.27.3.411

- Stiles, W. B., Morrison, L. A., Haw, S. K., Harper, H., Shapiro, D. A., & Firth-Cozens, J. (1991). Longitudinal study of assimilation in exploratory psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 28(2), 195. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.28.2.195

- Stiles, W., Meshot, C., Anderson, T., & Sloan, W. (1992). Assimilation of problematic experiences: The case of John Jones. Psychotherapy Research, 2(2), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503309212331332874

- Stiles, W. B. (1997). Signs and voices: Joining a conversation in progress. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01896.x

- Stiles, W. (1999). Signs and voices in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 9(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503309912331332561

- Stiles, W. B. (2001). Assimilation of problematic experiences. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.462

- van Zoonen, K., Buntrock, C., Ebert, D. D., Smit, F., Reynolds, C. F., III, Beekman, A. T., & Cuijpers, P. (2014). Preventing the onset of major depressive disorder: A meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt175

- Wells, A. (2011). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford press.

- Whelton, J., & Elliott, R. (2019). Emotion-focused therapy: Embodied dialogue between parts of the self. In A. Konopka., H. J. Hermans., & M.M. Gonçalves (Eds.), Handbook of dialogical self theory and psychotherapy: Bridging psychotherapeutic and cultural traditions (pp. 38–55). Routledge.

- Wulsin, L. R., Vaillant, G. E., & Wells, V. E. (1999). A systematic review of the mortality of depression. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199901000-00003