ABSTRACT

Nationalist populists as leaders of states that possess nuclear weapons undermine the nuclear order and increase nuclear dangers in novel, significant, and persistent ways. Such leaders talk differently about nuclear weapons; they can put nuclear policy making and crisis management in disarray; and they can weaken international alliances and multilateral nuclear institutions. The rise of nationalist populists in nuclear-armed states, including some of the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the 1968 Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, shatters the presumed distinction between responsible and irresponsible nuclear powers and complicates attempts to heal rifts in the international order. Policies to wait out populists or to balance their influence in multilateral institutions seem to have had limited success. A sustainable strategy to deal with the challenge posed by populists would need to start by recognizing that we can no longer assume that nuclear weapons are safe in the hands of some states but not in others’.

Introduction

The rise of nationalist populistsFootnote1 to power in nuclear-armed states and their allies is undermining the nuclear order and raising the risks of nuclear war. That populists such as Boris Johnson, Narendra Modi, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump were able to take charge of nuclear arsenals, including in some of the nuclear powers recognized under the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), challenges the assumption that established nuclear-weapon states behave responsibly. Nationalist populism,Footnote2 understood as a nationalist, anti-elitist, illiberal, and anti-pluralist set of ideas and politics conducted in the supposed interests of “the people”—that is, the domestic constituencies of the nationalist-populist leaders—has been on the rise globally since the mid-2000s. It has come to include the leadership of a growing number of countriesFootnote3 and has begun to influence the effectiveness of time-honored institutions of the nuclear order.

We argue that this rise of nationalist populists and their foreign and defense policies weakens the nuclear order in novel, significant, and persistent ways. Three characteristics are typical of nationalist populists’ nuclear policies: they talk differently about nuclear weapons; they have a specific way of getting involved in national decision making on nuclear-weapon issues; and their approach to international alliances and institutions is unique. The fact that nationalist-populist leaders have assumed control over nuclear weapons in countries at the core of the nuclear order shatters the presumed distinction between “responsible” and “irresponsible” nuclear powers. These leaders threaten the nuclear order built on the principled acceptance of a logic of restraint by the nuclear-weapon states.

Although it highlights the risks associated with populists’ control over nuclear weapons, this article does not aspire to a radical critique of the nuclear order.Footnote4 Our aim is to show that the rise of populists to the centers of power in nuclear-armed states challenges prevailing presumptions about nuclear risks and how they are to be managed. The view that a few responsible nuclear-armed states guard against irresponsible behavior by states mostly peripheral to the nuclear order is no longer defensible, if it ever was. Nationalist populists thus starkly expose the dangers intrinsically linked to nuclear weapons, regardless of regime type and the position of nuclear-weapon possessors in the international system.

We understand nationalist populists to be leaders who claim to implement policies to defend the interests of their constituencies, which they brand as “the people,” against supposed foreign and internal elites in order to bolster national sovereignty. Nationalist-populist leaders who had or have nuclear weapons under their control include former US President Donald Trump, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Russian President Vladimir Putin.Footnote5 We concentrate our analysis on these four nationalist-populist leaders, who have shaped foreign and defense policies—and particularly nuclear-weapon policies—in key nuclear-possessor states.Footnote6 The 2016 election of Donald Trump, a populist by any measure, is of particular significance, since the United States has consistently been the state with the largest ability to uphold and strengthen the institutions and practices that underpin the nuclear order.

Former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel and Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan are also nationalist populists. Israel, however, has a policy of nuclear opacity, under which it does not acknowledge possession of nuclear weapons.Footnote7 This made it impossible for Netanyahu to openly use nuclear weapons as a policy instrument in the same manner as other populists do. In Pakistan, the civilian leadership has only limited influence over nuclear-weapon policies because nuclear command and control rests with the armed forces.Footnote8

Chinese President Xi Jinping and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un are also often described as populists.Footnote9 Both leaders frequently use nationalist rhetoric, which resembles the populists’ style. However, we do not classify either as a nationalist populist because they do not rely on an internal in-group versus out-group dichotomy to justify their leadership. In autocratic regimes, such as those in China and North Korea, the leader holds absolute power and does not need to appeal to popular sovereignty or to employ other populist strategies.

In France, the Front National, now Rassemblement National, is an influential nationalist-populist movement. Opposition leader Marine Le Pen has promised to “restore the full meaning of the ‘force de frappe’” and reinvigorate national sovereignty through nuclear deterrence.Footnote10 A populist turn in French nuclear policies therefore remains a distinct possibility.

In two of the five nations that host US nuclear weapons under NATO nuclear-sharing arrangements, populists are in power (Turkey) or part of a government (Italy). In a third host nation, Belgium, a right-wing populist party has very recently been part of the government. In Germany, until the September 2021 parliamentary elections, a right-wing populist party was the strongest parliamentary opposition party.Footnote11

While populism, and particularly nationalist populism, has been on the rise in nuclear-armed states, three major developments in the background have reshaped the nuclear order. We understand this order to be characterized by the continuous search for accommodation between the goals of nuclear disarmament, on the one hand, and stability based on nuclear-deterrence relationships, on the other hand, through a policy of restraint and responsible behavior, particularly by the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the NPT.Footnote12 First, a more multipolar logic has begun to replace the primarily bipolar Cold War nuclear structure. In particular, the rise of new challengers to US hegemony has produced new power constellations.Footnote13 Second, new actors, including transnational non-state groups, are challenging the predominance of governments and pose new threats, particularly if those actors strive to acquire weapons of mass destruction. Third, the emergence of new military technologies has weakened strategic stability. For example, the entanglement of novel conventional and nuclear warfighting capabilities threatens to destabilize long-standing mutual-deterrence relationships, particularly between Russia and the United States, on the one hand, and between China and the United States, on the other hand.Footnote14

All three developments, and the interrelations among them, already are increasing nuclear dangers and unsettling the existing nuclear-deterrence relationships. The rise of nationalist populism and populists to power is a recent fourth development that adds to and amplifies these risks.

Our examination of the impact of the rise of nationalist populism on the nuclear order meshes with the attention given in academic literature to the role of individuals in nuclear policies. The recent shift toward the first image (that is, the analysis of international relations focusing on the impact of individual leaders as opposed to an analysis at the level of states or the international system)Footnote15 is associated with an investigation of how the perceptions and preferences of specific personality types have altered national nuclear policies and the nuclear order. We add to this literature by considering a specific type of leader, the nationalist populist, and his (rarely her) influence on nuclear issues.

The role of populism in foreign and defense policy, and particularly on nuclear policies, is seldom treated as a distinct phenomenon. This research gap has not been filled by issue-, country-, or region-specific investigations of the causes and effects of populism, which are more interested in how individual leaders have addressed particular issues than in the broad implications of the rise of nationalist populism.Footnote16

Our conception of nationalist populism overlaps with Jacques Hymans’s description of the “oppositional nationalist.”Footnote17 Hymans makes a convincing case that this type of leader has a particular affinity for nuclear weapons. However, where Hymans is interested in how leadership traits influence the decision to acquire nuclear weapons, we focus on policies affecting established nuclear arsenals. There is also a difference in framing between our idea of nationalist populism and Hymans’s notion of national-identity conceptions. The concept of “nation” is central to both frames. Yet populists equate the nation with their core domestic constituencies (and perhaps their own selves), while oppositional nationalists mostly view the nation-state as an entity in relation to other nations. Both view politics as the manifestation of an us-versus-them struggle. But nationalist populists and oppositional nationalists have different notions of the “us” (the people/nation) and different concepts of “them” (elites, other people/other nations).Footnote18

In our analysis, the Trump administration receives more attention than other nationalist-populist leaderships. This imbalance reflects the extraordinary amount of writing on an atypical US president. A focus on Trump is justified, since the United States remains the most important actor in the nuclear order. Also, Trump is often described as a prototypical populistFootnote19 who has inspired others to follow his lead and has generally increased the impact of populists in other countries. With Trump now out of office, this is a good time to take stock of his administration’s impact on the nuclear order: “Trump’s presidency offers, for good or ill, an excellent laboratory to examine whether and to what extent the assumption of government power by populists translates into foreign policy change.”Footnote20

We also consider the roles of other nationalist-populist leaders within the nuclear order and offer some observations on the implications of the rise of this phenomenon for nuclear disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation. We hope to provide a number of tentative arguments and conclusions about the distinct, dangerous, and often strange ways that populists are shaping the nuclear order.

Populist foreign and defense policy

To examine the influence of populism on foreign and defense policy, the idea of populism itself requires definition, or at least approximation. Populism is a fuzzy concept. At the most basic level, populists present themselves as atypical leaders from outside the establishment. Populists like to tell a story of how they are virtually predestined to represent and empower a silent and politically neglected majority (which they label as “the people”). But populism is neither a full-fledged political ideology nor simply a political or rhetorical style. It is rather a “thin-centered ideology.”Footnote21 Populism is inherently difficult to pin down, since populists want to maintain maximum flexibility to apply their ideas to, or combine them with, other ideologies—right, left, or drawing upon both—regardless of the underlying political system.

The notion of a populist foreign and defense policy is equally hard to delineate. Leaders’ foreign policies reflect their personal characteristics and political behavior, how they interpret the world and their role in it, how they make decisions, and how they interact with others.Footnote22 As Daniel Byman and Kenneth Pollack state, “It is individuals who build the alliances, and create the threats that maintain or destroy balances of power.”Footnote23 Populist leadership is especially personalistic; a populist leader’s beliefs and decisions can be assumed to be more influential in shaping foreign and defense policies than those of other leaders.

Nationalism, as one of the possible host ideologies of populism, adds another layer. Nationalist and populist discourses overlap; what the nation is to the nationalist, “the people” is to the populist. The concepts of sovereignty and self-determination drive both discourses, but they affect foreign and defense policies through different mechanisms.

In principle, there is a clear delineation between a given nation and all other nations. The populists’ idea of “the people” is vaguer. Populists use this ambiguous construct to evoke a group (their “base”) within a polity, juxtaposing it with “elites” at the top. According to populists, these elites are outside the group of the “real” or “true” people. Populist politicians boast about not being part of the elite class (a claim that is rarely true, in economic or educational terms) and thus claim to speak and act in the name of the people from within their ranks, implying that only they can genuinely represent them.Footnote24

Nationalist populists not only claim to speak for “the people” but also presume to define the nation. They fuse inward-looking populist discourse with a more outward-oriented nationalist ideology. This shift in the frame of reference portrays the elites as depriving the people of their sovereignty both at home and abroad.Footnote25 As Jordan Kyle and Brett Meyer put it, “foreign policy is often collateral damage of populists’ divisive approach to domestic politics.”Footnote26

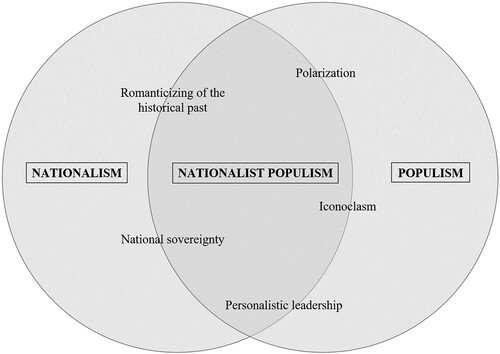

We identify the following characteristics of external policies pursued by nationalist populist leaderships:

Polarization. “Us versus them” is the predominant discourse. Restraint, empathy, and compromise are anathema.Footnote27

Romanticizing of the historical past. Populists want to revive the “national missions” of their own countries.Footnote28

Personalistic leadership. Political authority rests primarily with a single person, often the head of a movement,Footnote29 rather than within structures and institutions. Foreign and defense policies are extensions of domestic policy debates. The leader’s political messaging is direct, with “the people,” often via social or new media, while ignoring established channels of interaction with the broader public.Footnote30

National sovereignty. Populists view alliances and international institutions as constraining the freedom of nation-states.Footnote31 The short-term, narrow interest of the nation is the sole yardstick of success.Footnote32

Iconoclasm. Populists want to dismantle international organizations, which they view as the instruments of circles of elites who support international cooperation and integration. They reject cultural and economic globalization and free trade.Footnote33

These criteria do not represent a comprehensive account of the nationalist-populist phenomenon, and the checklist is not exhaustive. Some of these traits could also apply to non-populist foreign and defense policies. Nevertheless, taken together, these features of the nationalist-populist approach to international policy issues capture a unique, identifiable phenomenon: if a leader walks like a populist, talks like a populist, and acts like a populist, then he or she most likely is a populist (see ).

Here to stay: the proliferation of populism

The rise of nationalist populists to power in nuclear-weapon states is a phenomenon worthy of in-depth analysis for three reasons. First, the development is of an unprecedented scale globally. A recent overview found that there are “more populist leaders and parties in power than at almost any time in history.”Footnote34

Individuals and their beliefs and preferences, along with external systemic factors, shape foreign-policy decisions and interactions among states. However, how and to what degree populists influence nuclear policies varies between countries. Populists have risen to power in democracies, electoral autocracies,Footnote35 and other hybrid regimes. Depending on the political system, their influence may be constrained by other branches of government and by actors, such as private companies, whose interests may be inconsistent with a populist agenda. Generally speaking, the individual leader has the greatest influence on a state’s decisions and behavior in personalistic systems. By contrast, the checks and balances of pluralistic systems often constrain democratically elected leaders. Even there, however, nationalist populists increase their influence by constantly chipping away at the core values, principles, and procedures of liberal democracy, such as separation of powers, rule of law, political representation, and individual rights and freedoms.Footnote36

Second, nationalist populists have risen to power in three of the five nuclear-weapon states. The significance of that development for the nuclear order is particularly great, since these five states bear a special responsibility for maintaining and improving that order and international peace generally.Footnote37 In their parallel role as the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, their consent is necessary for enforcement of compliance with the NPT and other multilateral regimes. Their willingness to forgo nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, or their lack of willingness, sets examples for other, less influential states.

In the past, Western leaders often dismissed populism as a problem of less developed countries.Footnote38 At the same time, nuclear establishments saw the peace movement and other grassroots movements as populist—that is, non-elite groups that were challenging elitist policies supposedly based on rationality and stability.Footnote39 To be sure, the time for finger pointing is over. “Populism has not just risen in emerging democracies with weaker political parties and institutions but in systemically important democracies with long institutional histories like the United States and India,” as Kyle and Meyer observe.Footnote40 Few if any states now appear to be immune to populist challenges. Consequently, the assumption that the established nuclear-weapon states can protect the nuclear order from less responsible challengers must be revised.

Third, populism is here to stay. To be sure, populism is not a new phenomenon, and populists have challenged the nuclear order before in various ways.Footnote41 Today’s populism, additionally, is fueled by the perceived inability of states and institutions to attend to the political, economic, and cultural consequences of the global economic crisis of 2008, as well as the increase in xenophobia following the increase in conflict-induced flight and migration into Europe since 2015.Footnote42 In the context of “crises of political representation engendered by dislocations caused by globalization and other shifts in international politics” and as a “reaction to concurrent political and economic crises in a rapidly denationalized and deterritorialized world,”Footnote43 the rise of populism has been a reaction to perceived insecurity, inequality, depoliticization, and economic stagnation.

As a result, a rise of illiberalism and a wave of autocratization can be observed.Footnote44 Nationalist populists have come to power in the shadow of the crisis of the liberal international order, benefiting from the crisis and perpetuating it. The impact of nationalist populism is going to stay with us, likely beyond the lifetime of individual nationalist-populist governments. That is partly because the leaders have begun to paralyze, reshape, and dismantle existing bureaucracies. Nationalist populists define themselves as being anti-elitist (even if they themselves are members of the elite). Once they occupy the seats of power, national populists co-opt, exchange, or sideline old elites. The resulting reshuffle in the foreign and defense apparatuses sometimes resembles a purge and can lead to dramatic discontinuities in expertise. It will take time to repair the damage done to governance structures and to heal the wounds caused by political polarization.

In the nuclear world, this destabilization of institutions is particularly significant. The nationalist-populist assault weakens the influence of those who are supposed to act as “guardians of the arsenals.” The influence of nationalist-populist leaders on nuclear-weapon policies also has grown.Footnote45 When it comes to nuclear-weapon use, the dangers posed by nationalist populists are stark because in most nuclear-weapon states the head of state or government has the legal authority to order the use of nuclear weapons. But there are different shades of gray. In nuclear-armed states with presidential systems (France, Russia, and the United States), launch authority “clearly rests in the hands of one single person,” while in those with parliamentary systems (India, Israel, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom), “the decision to launch a nuclear strike would necessarily not be the sole authority of one individual, even if it is ‘legally’ (i.e. on paper).”Footnote46

Three ways populists change the nuclear order

Against this background of the characteristics of populists’ foreign and defense policies and the diffusion of populism into nuclear powers’ decision-making centers, we describe three relevant causal mechanisms through which nationalist populists influence the nuclear order. First, nationalist populists have a different way of speaking. “[T]he specific style of rhetoric used by the populists involves adversarial, emotional, patriotic, and abrasive speech through which they connect with the discontented often via grassroots, community-oriented, communicative practices and spaces.”Footnote47 For nationalist populists, the domestic audience is the most important recipient of any messaging; everything is said with a communicative purpose to please “the people,” to secure their approval and votes and therefore to retain power.

Second, nationalist populists have a particular way of making decisions, sometimes reflective of the fact that delineating “the people” from an “elite” is a constitutive element of populism. Whereas usually a small and closed group of experts and officials prepares and executes decisions in foreign and defense policy, the policy style of nationalist populists is a peculiar mix of laissez-faire on routine issues and very visible leadership when the stakes are high. As Kyle and Gultchin argue, populists seek to convince their supporters that they “see and acknowledge the crisis and that their strong leadership alone can fix it.”Footnote48

Third, nationalist populists have a distinct perspective on the international order. They view the world through a “great-power” lens that is consistent with the “realist” logic of foreign and defense policy. At the same time, nationalist populists reject the notion of an international order based on and shaped by bilateral and multilateral agreements and treaties. This is partly because the rise of nationalist populism “has brought a new persona to the global stage—the iconoclast. This deliberate rule breaker disrupts the practice of international relations, a system that depends upon consensus around norms.”Footnote49

Talking about nuclear weapons

As Alexey Arbatov has observed, “when it comes to nuclear weapons, words are deeds.”Footnote50 This is because nuclear weapons have been exploded in war only twice. All other “uses” of nuclear weapons have been limited to verbal actions, policy documents, deployment, testing, and other actions short of direct hostile use.Footnote51

Usually, nuclear messaging is the outcome of a careful and deliberate process. For example, heads of state or government typically speak about nuclear arsenals and nuclear strategy on the basis of carefully scripted and meticulously reviewed statements. Exegesis of nuclear-policy documents and speeches is the preoccupation of many nuclear analysts, based on the assumption that, especially in the nuclear world, leaders and officials have thoroughly weighed and consciously selected their words.

Nationalist populists, by contrast, often speak loosely about nuclear weapons, which complicates a “reading” of their statements.Footnote52 This concerns both style and substance, which coincide with their personalistic style of leadershipFootnote53 and their desire to flout the rules of what they deride as “political correctness.”Footnote54 Donald Trump has again led the way—for example, through his excessive tweeting on nuclear-weapon issues.Footnote55 Other nationalist populists have also deviated from previous rhetorical styles by bragging about their nuclear weapons. In April 2019, shortly after an escalation of the Pulwama crisis between India and Pakistan had been averted, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi suggested that his country was ready to use nuclear weapons against Pakistan: “Every other day they used to say ‘we have nuclear button, we have nuclear button’. What do we have then? Have we kept it for Diwali?”Footnote56 President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s October 2019 statement that it is unacceptable for Turkey not to have nuclear weapons because “[t]here is no developed nation in the world that doesn’t have them”Footnote57 is another typically populist statement, conflating strong views with half-truths or lies.

Such loose talk may have several purposes. By emphasizing nuclear weapons, nationalist populists can set themselves apart from the established elite discourse. Donald Trump boasted of having gained knowledge of nuclear weapons not through a formal education but through his uncle, a professor of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Footnote58 Thus, the US president believed that he did not need to rely on the expertise and experience of the nuclear elite. This ignorance of nuclear lessons by virtue of not “being socialized to the dangers of nuclear weapons”Footnote59 derived from the past is a trademark of nationalist populists, but is also part and parcel of a general loss of expertise in executives and parliaments in nuclear-weapon states and nuclear-allied countries.Footnote60

Nationalist populists also like to make strong statements on nuclear issues because they may believe that this impresses their main target audience—that is, their domestic power base. Thus, Putin has several times used his regular direct encounters with the Russian public to highlight the importance of nuclear weapons for Moscow’s standing in the world. In March 2018, Putin, in his speech to the Federal Assembly of Parliamentarians, policy makers, religious leaders, public figures, and members of the media, boasted about Russia’s nuclear capabilities and in true populist fashion even invited “[t]hose interested in military equipment … to suggest a name for this new weaponry, this cutting-edge” nuclear-weapon system.Footnote61

And Modi made repeated reference to India’s nuclear weapons during the 2019 parliamentary election campaign. As one analyst observed, “The context of Modi’s remarks on nuclear weapons—election rallies—matter[s], of course. With a poor economic track record since 2014, the [Bharatiya Janata Party] has rightly decided to focus on what much of the Indian public perceives as a strength: its management of national security and defense.”Footnote62

In a similar vein, nationalist populists may bring religious motives into the nuclear discourse. Thus, Putin seems to believe that “Orthodoxy and the nuclear deterrent are equally important bulwarks of Russian statehood, guaranteeing the nation’s security internally, in the case of the church, and externally, in the case of the nuclear arsenal.”Footnote63 Talking about nuclear weapons primarily in order to impress the domestic power base—rather than external actors—can increase nuclear risks in various ways.

Nationalist populists tend to trivialize nuclear risks while exaggerating the benefits of having nuclear weapons. This idealization of nuclear weapons can break down (verbal) barriers and incentivize other states to pursue nuclear weapons. The mixing of domestic and external audiences also may make it more difficult for third parties to judge the intentions behind strong statements. When Trump says that he wants to unleash “fire and fury” on North Korea, to whom is he talking?Footnote64 External observers may believe that signals are intended for domestic consumption—but they cannot be sure.

Populist decision making on nuclear weapons

In most nuclear-weapon states and under normal conditions, a small group of experts prepares decisions on the direction of nuclear-weapon policies.Footnote65 Routine nuclear policy making often remains remarkably unaffected by changes in political leadership. Secrecy and path dependencies complicate any precise analysis of the impact of the rise of nationalist populism on routine policy making. But a few tentative observations can be offered.

Routine decision making on nuclear-weapon-related issues appears to remain mostly below the radar of most nationalist populists in power. The long, deliberative processes behind nuclear-weapon policies do not lead to the quick payoffs in public attention that nationalist populist leaders typically seek. From the perspective of the guardians of the arsenal—the group of “initiated” experts with relevant security clearances—there is little reason to change that. If and when nationalist populists get involved in policy making, their instincts usually favor greater reliance on nuclear weapons. But their unruly approach to politics is not very compatible with the inertia-driven approach of the nuclear establishment. Thus, at a briefing for him at the Defense Department on July 20, 2017, Trump reportedly asked why he didn’t have as many weapons as past presidents did, pointing out that the United States at the height of Cold War had had more than 30,000 nuclear weapons, as opposed to “only” a few thousand by 2017.Footnote66

Nationalist populists’ disinterest in and absence from routine policy making may empower officials with radical views. Nuclear doctrines are a case in point. Thus, the February 2018 US Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) changed the trajectory of US nuclear-weapon policies by introducing new types of nuclear weapons. The NPR widened the scenarios under which nuclear weapons might be used, blurred boundaries between conventional and nuclear scenarios of warfighting, lowered the threshold for nuclear-weapon use, and shifted nuclear-weapon-deployment scenarios in the direction of warfare—that is, away from the idea that the only legitimate use of nuclear weapons is to deter existential threats.Footnote67 But “Trump had nothing to do with the [NPR]; it was written almost entirely inside the Pentagon, as previous reviews had been, with still less direction or input than usual from the White House,” as Fred Kaplan observed.Footnote68 So the changes can be explained partly by the “resurgence of the nuclear establishment” and its “convergence” with the rise of Trump.Footnote69

A similar hands-off attitude may explain the rash nuclear threats that Russian diplomats have issued against third countries. Such bullying appears to be possible only because the Kremlin provides the political space for it by justifying aggressive postures (and annexations) in nationalist terms.Footnote70 Thus, the hands-off approach of nationalist-populist leaders to routine issues can also have a disruptive effect on nuclear policies. While the outcome may resemble the policies of hawkish conservatives, the policy process leading to the outcome is markedly different. This difference is relevant to the effect of such policies: nationalist populists’ neglect of detail and their ignorance of strategy can make it harder for others to assess the significance of policy changes and associated messages.

Thus, bringing the nationalist populists into decision making on nuclear policy also runs the risk of their instincts ruining and counteracting the results of previous policy making, again adding a degree of unpredictability. A prime example is the January 2019 US Missile Defense Review. The document itself is the product of a multi-year interagency process. One of the key questions was whether the review should revise US and NATO policies so that they would direct missile defenses against the threat of Russian long-range missiles. The potential use of Western missile defenses in that way is a central factor influencing Russian nuclear policies. The review itself did not result in such a change of policy.Footnote71 President Trump, however, presenting the review results at a January 17, 2019, press conference, contradicted US policy by stating, “Our strategy is grounded in one overriding objective: to detect and destroy every type of missile attack against any American target, whether before or after launch. When it comes to defending America, we will not take any chances. We will only take action. There is no substitute for American military might.”Footnote72 Predictably, Russia seized on the contradictions between policies coming out of the bureaucracy and statements by the president to argue that the Trump administration was seeking to attain military dominance and justify its own expansion of nuclear capabilities.Footnote73 Nationalist-populist grandstanding thus can have the indirect effect of paving the way for competitors to react by increasing their own nuclear capabilities.

The impact of nationalist-populist decision making and “instincts” during nuclear crises is a particular cause for concern. Nationalist populists by nature tend to be risk takers, and their mistrust of their own nuclear establishments—which tend to be risk averse—may facilitate dangerous moves. Putin’s statements after the annexation of Crimea that Russia “was ready” to put nuclear forces on alert is an indication of his willingness to raise the stakes.Footnote74 Erdogan’s decision to cut off power to Incirlik Air Base, where about 50 US nuclear weapons are deployed, during the 2016 coup attempt against him is another example of ignorance of nuclear dangers during a crisis. For nationalist populists such as the Turkish president, the importance of securing the domestic power base overrides all other concerns about nuclear security.Footnote75

Even before Trump assumed office, his authority as president over the use of nuclear weapons was a source of deep concern in the United States. At one point during the Trump administration, US Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis allegedly reassured members of Congress that he personally had “inserted himself into the nuclear weapons chain of command” in order to manage Trump’s “dangerous impulses.”Footnote76 But Mattis and others who were trusted to rein in the president were soon gone.

The dramatic effects of populism on nuclear-weapon control became shockingly apparent on January 6, 2021, when protesters inspired by President Trump stormed the US Capitol to overturn the results of the November 2020 presidential election, in which Trump lost to his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden. The insurgents apparently came close to Vice President Mike Pence, who was followed by military personnel carrying the Presidential Emergency Satchel, which contains nuclear launch options and other highly classified equipment and information.Footnote77 In reaction, the speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, sought assurances from General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to prevent “an unstable president from initiating military hostilities or accessing the launch codes and ordering a nuclear strike.”Footnote78 This request came in the context of concerns about “Trump's politicization of the military” and fears the president “could use the military, either domestically or internationally, in an improper manner with the goal of influencing the election or staying in power.”Footnote79 Milley was so concerned that Trump might attack China to remain in power that, in early January 2021, he twice assured his Chinese counterpart that things were under control. Milley also told the US military leadership that any order to launch a nuclear strike by the president would have to be approved by him personally.Footnote80

The lack of traditional safeguards against a radicalization of foreign and defense policies under a nationalist-populist leader has led one former commander of a British Trident nuclear submarine to state publicly that he would not necessarily have followed nuclear launch orders from Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Andrew Corbett argued that Johnson’s government does not exhibit “the integrity or humility necessary to justify” the trust a commander needs to launch nuclear weapons. To Corbett, the British government’s “attempts to politicise key institutions of independent scrutiny within and outside of Parliament” indicate “a policy of weakening the very checks on executive impulse on which the assumption of the integrity of the political control of nuclear weapons is predicated.”Footnote81 In this way, nationalist populists lay bare and heighten the risks associated with entrusting individuals with the authority to use nuclear weapons.Footnote82

Loose talk also may complicate future crises. Thus, the nuclear rhetoric used by nationalist-populist leaders in the February 2019 Pulwama crisis between India and Pakistan was dangerous because it appeared to lower the threshold for nuclear use. As a result, both sides “may now anticipate the other readying or deploying nuclear forces far earlier than previously thought.”Footnote83

The use of Twitter—the preferred means of communication of many populistsFootnote84—during crises is particularly risky because the mixing of audiences can undercut the credibility of threats, messages may be sent without the input of experts, and such short messages are particularly prone to misinterpretation.Footnote85 Thus, a recent study finds that one way in which Twitter could facilitate inadvertent escalation in a crisis situation is through collateral messaging—that is, when “a tweet intended for a domestic audience, perhaps one meant to signal leadership or promote a ‘strongman’ image, is misinterpreted as aggressive by a foreign audience.” The report finds that “[t]his is particularly dangerous when it is at odds with other government messaging.”Footnote86

Even when populists reign, there may be a great deal of continuity at the working levels of government from day to day. Yet populists frequently see major conflicts and crises as an opportunity to create attention for their own agenda. Their interventions in policy making under such circumstances, when the stakes are particularly high, can be disruptive. For allies and foes alike, the resulting policy can be confusing. Everyday interactions with administrations led by nationalist populists may continue as usual (or even intensify because leaders do not interfere), but it remains unclear whether and when agreements reached might be accepted, altered, or canceled by nationalist populist leaderships.

Conceptualizing nuclear order

The emergence of nationalist-populist leaders in nuclear-weapon states has damaged the institutions underpinning the global order. Nationalist populists generally see global institutions and international arrangements as disadvantageous for their own countries. Their attitudes toward global nuclear regimes are instrumental, at best. The Trump administration’s May 2018 decision to cease its participation in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) negotiated with Iran is a case in point. It put the United States at odds with UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which gave the JCPOA its legal character. Noncompliance with the agreement has damaged Washington’s legitimacy as a permanent member of the Security Council. It also set a possible precedent for other (permanent) members of the Security Council, who may point to the US shift in policy to justify their own decisions to stop adhering to Security Council decisions.Footnote87

Nationalist populists do not shy away from radical moves to realize short-term gains while disregarding the long-term implications of their actions. The frame of reference for decisions on withdrawing from or violating international commitments is narrow: such decisions are justified exclusively by the (alleged) benefits for their own people or nation, while disregarding the broader regional or global implications. Putin’s indifference to the Budapest Memorandum when annexing Crimea in 2014 is an example of how a nuclear-weapon state can be willing to severely damage the credibility of security guarantees, which are a key instrument underpinning the nonproliferation regime. The Russian president violated the agreement in the hope of achieving narrow security benefits and boosting his image as protector of the Russian nation.Footnote88

Such nationalist-populist actions result in double standards. Trump punished Iran when it was complying with international nonproliferation obligations while at the same time he courted North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un, a serial violator of nonproliferation rules, and praised him as a “great leader.”

Other nationalist populists can exploit these double standards to their own advantage by invoking real or alleged injustices to justify their nationalist, self-serving policies. President Erdogan’s argument that nuclear-armed countries prevent Ankara from developing nuclear weapons is “a message that is heavily loaded with populism,” as Turkish analyst Sinan Ulgen has observed.Footnote89

Nationalist populists also argue that their ability to break with old routines is better suited to finding solutions than policies that cling to established tracks. This is consistent with their narrative that there are mainstream taboos that need to be overcome in order to address “the real issues.”

However, the nationalist populist track record of attempts to break Gordian knots is dismal. There is not a single case in which policies based on such unconventional approaches have brought about sustainable solutions to a nuclear-proliferation problem. To the contrary, the Trump administration’s approach to North Korea’s nuclear-weapon program may well turn out to be counterproductive because it strengthened the hands of those in Japan and South Korea who believe that national nuclear-weapon programs may be the best way to provide security.Footnote90

In an integrated and globalized world, spillover from populists’ agendas into the international arena occurs. Kyle and Meyer point out that, “whereas the effects of populism in power were once confined to a country’s local political institutions, the effects of today’s populism promise to be global, reshaping global financial flows, trade relations, and foreign policy for years to come.”Footnote91 Of relevance to the nuclear order is the threat that nationalist populists can pose to alliance cohesion. This is particularly true for nuclear alliances with extended-deterrence commitments. Nationalist populists tend to denounce such promises as entanglements of sovereign states. In those narratives, nuclear weapons are a way to ensure the national autarky and independence that nationalist populists value.Footnote92

Alliances and regional bodies, particularly if they involve a degree of integration that reduces national freedom of action by creating mechanisms for consultation and cooperation, are anathema to the nationalist-populist worldview. In addition, nationalist populists reject the notion that multinational institutions can provide win–win solutions by reducing transaction costs and providing stable frameworks for communication. Thus, Trump failed to appreciate that alliance relationships within NATO are based on more than a transactional cost–benefit analysis. His frequent questioning of NATO’s core purpose harmed the credibility of US security guarantees.Footnote93

This is particularly true for nuclear commitments, which in the end always depend on the US president’s decision to use, or not use, nuclear weapons. The erratic and obviously unstable personality of the president undermined the rationality of nuclear decision making and reduced Trump’s ability to consult with allies, particularly during a nuclear crisis. In addition, Trump’s “America First” worldview raised serious questions about whether he, in a crisis situation, would be willing to risk Pittsburgh for Paris.Footnote94

Conversely, nationalist-populist recipients of security assurances may create problems for alliance relations. For example, the emergence of nationalistic and populist governments in Europe makes it more difficult to maintain domestic support for collective defense in non-populist countries. Thus, Tobias Bunde has wondered whether liberal democracies would really come to the defense of their illiberal allies.Footnote95

The nationalist populists’ distrust of the elites and establishments that are responsible for the routine operation of partnerships can also undermine the effective functioning of alliances. For example, Turkey under Erdogan has to a large degree replaced the Turkish experts and officials representing Ankara at NATO headquarters with staff loyal to him, creating ruptures in alliance relationships.Footnote96

Instead of working through alliances, nationalist populists often trust their ability to arrive at better deals through personal relationships with other leaders, particularly other nationalist populists. Erdogan has been engaged in high-risk bargaining over the purchase of a Russian missile-defense system, even though this has damaged relations with NATO and Turkey’s role in nuclear-sharing arrangements. NATO as an alliance was unable to create a coherent response to this development, partly because Trump put his good personal relations with Erdogan above alliance unity.Footnote97

On the positive side, nationalist populist challenges from the outside can increase alliance cohesion. Thus, Putin’s aggressive policies have revitalized NATO’s sense of mission. Nationalist-populist challenges from within alliances can also lead to a recommitment to core purposes. Trump’s pressure on Europeans to do more on defense has certainly increased the feeling that the European allies needed to recommit to efforts on defense and deterrence, including nuclear deterrence.

But this argument can only be taken so far. It finds its limits when alliance cohesion also necessitates finding joint approaches to problems that can be solved only through cooperation. Thus, nationalist-populist leaders see arms control as “a zero-sum rather than a positive-sum game,” amplifying the problem that “members of military alliances will be reluctant, at the very least, to subordinate their parochial interests to notions of the common good.”Footnote98 As a result, the transactional perspective can damage ties that have grown over many years. Defense establishments may be well aware of such damage but, because of their limited influence under populist leaderships, can find no way of correcting such policies. Commenting on the Trump administration’s demand that South Korea pay roughly 400 percent more in 2020 than in the previous year for keeping US troops on the peninsula, a congressional aide reportedly described the dilemma this way: “The career professionals and career military: they’re beside themselves, but [Trump is] the commander in chief, so they're in a box.”Footnote99

Conclusions

Using the example of nuclear-weapon policies, we have argued that there is a specific policy style and set of ideas associated with nationalist-populist leaders that set them apart from other types of leaders. Nationalist populists speak irresponsibly about nuclear weapons, take risks, and make short-sighted decisions that are based on domestic power considerations rather than a rational view of the international environment. In an unprecedented way, the rise of nationalist populism has brought these phenomena to the centers of power in nuclear-weapon states. This development has been taking place at a time when many analysts and decision makers see nuclear risks as higher than during the Cold War.Footnote100

In several ways, the rise of nationalist populism in established nuclear-weapon states does not bode well for attempts to heal the rifts in the international order, particularly through calls on nuclear-weapon possessors to act more responsibly.Footnote101 First, nationalist populists feel committed only to their own power base. Second, a responsible nuclear-weapon state today may turn into one led by a populist tomorrow. Some of the nuclear-weapon states that previously may have been described as responsible actors are now among the most irresponsible. Third, the rise of nationalist populism is likely to continue. While some believe that the populist wave may have crested,Footnote102 nationalist populist movements in some nuclear-weapon states are still on the rise.

What can be done to limit and offset the risks that nationalist populists pose to the nuclear order?

A strategy to deal with the challenge posed by nationalist populists must start by recognizing that we cannot assume that nuclear weapons are safe in the hands of some states but not in the hands of others. This is not to say that all nuclear-weapon possessors are equally irresponsible. But populism, and particularly nationalist populism, has moved to the center of nuclear decision and policy making, blurring the presumed line between established nuclear powers at the core of the nuclear order and irresponsible newcomers at the periphery.Footnote103 The assumption that “nuclear weapons restrain the political behavior of nuclear leaders and reduce the likelihood of war among nuclear powers”Footnote104 should be reassessed when nationalist populists are in power.

In the United States, Trump’s rise to power triggered a debate about limiting the president’s power to use nuclear weapons.Footnote105 No other nuclear-armed state is debating limits on the nuclear-launch authority of its national leaders, though this may change, should nationalist populists threaten to assume control over nuclear weapons elsewhere—for example, in France.

Allies with an interest in maintaining global institutions need to develop policy responses primarily within collective-security arrangements. The nationalist-populist outlook of security providers calls into question the value of positive security guarantees. Countries dependent on nationalist-populist allies will tend to maintain and seek close relationships with their security providers simply because they lack credible alternatives. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, for example, attempted to use his good personal relationship with Trump to “tame the monster.”Footnote106 In the end, however, “bandwagoning”—aligning one’s foreign policies with those of a stronger stateFootnote107—and appeasement are risky strategies because populists are likely to put narrow national interests above alliance cohesion.

The election of Trump and Erdogan should lead to a revised risk–benefit evaluation of NATO’s nuclear-sharing arrangements. The Federal Republic of Germany has always viewed nuclear consultations as an instrument that helps keep it informed about the nuclear policies of nuclear-armed allies so it can prevent changes that it views as detrimental to its own security.Footnote108 Populists are less likely to inform allies, let alone consult them, on nuclear issues.Footnote109 This became obvious to allies when Trump in October 2018 decided to withdraw from the 1987 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty without consulting allies. Additionally, nationalist-populist leadership in host nations may pose the risk that the basing country will assume control over nuclear weapons deployed on their territory, as the example of Turkey demonstrates.Footnote110

At the global level, it is difficult to counteract nationalist populists’ influence. Multilateral regimes may be able to withstand temporary problems caused by individual noncompliant states. Some may hope that populism will simply wither away and that they can wait the populists out. But, as argued above, the underlying assumption that populism is a passing phenomenon is questionable.

The Alliance for Multilateralism, which is an “informal network of countries united in their conviction that a rules-based multilateral order is the only reliable guarantee for international stability and peace and that our common challenges can only be solved through cooperation,”Footnote111 can be understood as a way to balance and constrain the destructive policies of nationalist populists at the global level. Yet it is not clear what shared interests, apart from opposing nationalist populism, these multilateralists have.

In the meantime, multilateralists attempt to maintain ties by cooperating with the populists on issues that are deemed noncontentious. In the nuclear area, this relates, for example, to nuclear security and the prevention of terrorist attacks with chemical, biological, nuclear, or radiological weapons through better preparedness and improved resilience.

The challenge is complex. It arises from within the multilateral system but has been created by the anti-multilateralist positions of the nationalist-populist leaders of great powers. If these countries are permanent members of the UN Security Council, the problem is even more difficult to tackle.

The rise of nationalist populism is taking place in the context of an erosion of democracy, a rise of authoritarianism, and the proclaimed demise of the liberal international order. Populism is simultaneously a cause and a symptom of underlying disintegration processes often framed as democratic backsliding and the end of the US-led liberal order. Effective responses to counter nationalist-populist policies and arguments have to be proactive. States and societies cannot simply wait for nationalist populists to fail as a result of the contradictions that their policies produce. Political systems have to address the root causes of populism in order to make them more resilient to the threats populists pose and to counterbalance the risky behavior in which populists tend to engage. This is true particularly for the nuclear order, where the risks are existential.

In describing the dangers associated with the rise of nationalist populism to power in nuclear-weapon states, we have used illustrative examples to make our arguments. Future research could draw on more empirical data and hopefully describe the specifics of nationalist populists’ policies in a more comprehensive and systematic manner. While the nationalist-populist leaders described here share specific ideas and a policy style, they differ in important ways. Analyzing the different characteristics and strategies of nationalist-populist foreign and defense policy, and particularly nuclear policies, in a more systematic way would be useful to identify the ways in which these actors talk about nuclear weapons and make decisions. It would also be worthwhile to analyze in detail how nationalist-populist nuclear-weapon policies interact with the trends in the nuclear order that have increased nuclear risks over the last 30 years—the shift to a multipolar order, the growing importance of subnational actors, the weakening of strategic stability through novel technologies. We are afraid that the bleak picture we have painted would then become even darker.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, Jonas Schneider, and Benoît Pelopidas, as well as the participants in the December 2019 Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Conference in Hamburg, for their comments and valuable feedback.

Notes

1 Here, “populist” and “populism” will be used to refer to the overarching phenomenon, while “nationalist populist” and “nationalist populism” indicate the specific subtype we aim to describe and analyze.

2 Other forms or subtypes of populism, such as left-wing populism, have arisen in other contexts, at different times, and in different world regions but are outside the scope of this paper. Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser identify the end of the 19th century as the starting point for agrarian populist movements in Russia and the United States, and three populist waves that came after this. The first populist wave swept Latin America after the Great Depression and saw left-wing populists come to power in several countries, such as Juan Perón in Argentina. This phase lasted until the 1960s. The second wave, in the 1990s, affected Latin America, with, for example, Alberto Fujimori in Peru and Carlos Menem in Argentina coming to power, and European countries, with populist leaders such as Alexander Lukashenko assuming power in Belarus. The third wave began in 1998, with Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua coming to power. According to Mudde and Kaltwasser, this third wave is still ongoing. Electoral breakthroughs and the electoral persistence of populist movements, leaders, and parties are the most obvious indicators of populism’s rise to power. But populists can be formidable political forces even without such successes at the polls. See Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Populism: A Very Short Introduction (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017).

3 Prime examples are Victor Orbán in Hungary, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and the Syriza party in Greece.

4 Nick Ritchie, “A Hegemonic Nuclear Order: Understanding the Ban Treaty and the Power Politics of Nuclear Weapons,” Contemporary Security Policy, Vol. 40, No. 4 (2019), pp. 1–26; Benoît Pelopidas, “Nuclear Weapons Scholarship as a Case of Self-Censorship in Security Studies,” Journal of Global Security Studies, Vol. 1, No. 4 (2016), pp. 326–36.

5 Richard Carr, “Boris Johnson: Populists Now Run the Show, but What Exactly Are They Offering?,” The Conversation UK, July 23, 2019, <https://theconversation.com/boris-johnson-populists-now-run-the-show-but-what-exactly-are-they-offering-120808>; Manjari Chatterjee Miller, “India's Authoritarian Streak: What Modi Risks with His Divisive Populism,” Foreign Affairs, May 30, 2018, <www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2018-05-30/indias-authoritarian-streak>; Thorsten Wojczewski, “Conceptualizing the Links between Populism, Nationalism and Foreign Policy: How Modi Constructed a Nationalist, Electoral Coalition,” in Frank A. Stengel, David B. MacDonald and Dirk Nabers, eds., Populism and World Politics (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 251–74; Lionel Barber and Henry Foy, “Vladimir Putin Says Liberalism Has ‘Become Obsolete,'” Financial Times, June 28, 2019, <www.ft.com/content/670039ec-98f3-11e9-9573-ee5cbb98ed36>.

6 See, for example, Jordan Kyle and Limor Gultchin, “Populists in Power around the World,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, November 7, 2018, <https://institute.global/insight/renewing-centre/populists-power-around-world-Power-Around-the-World-.pdf>; Jordan Kyle and Yascha Mounk, “The Populist Harm to Democracy: An Empirical Assessment,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, December 26, 2018, <https://institute.global/sites/default/files/articles/The-Populist-Harm-to-Democracy-An-Empirical-Assessment.pdf>.

7 See Avner Cohen, Israel and the Bomb (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1999).

8 As Christian Wagner and Oliver Thränert conclude. ”Control over the nuclear potential remains the army leadership’s bargaining chip, with which it protects its privileged position in Pakistan.” See Oliver Thränert and Christian Wagner, “Pakistan as a Nuclear Power: Nuclear Risks, Regional Conflicts and the Dominant Role of the Military,” SWP Research Paper 2009/RP 08, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, June 2009, <www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/research_papers/2009_RP08_trt_wgn_ks.pdf>, p. 29. Since assuming office, Khan has spoken twice on the solely defensive role of the Pakistani nuclear arsenal, dismissing nuclear war as self-destructive and even suggesting giving up nuclear weapons for good—if India would do the same and the Kashmir conflict were solved. See Adnan Khan, “Imran Khan Bargains with Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons,” Geopolity, June 27, 2021, <https://thegeopolity.com/2021/06/27/imran-khan-bargains-with-pakistans-nuclear-weapons/>.

9 See, for example, Elizabeth J. Perry, “The Populist Dream of Chinese Democracy,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 74, No. 4 (2015), pp. 903–15, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S002191181500114X>; Salvatore Babones, “Xi Jinping: Communist China's First Populist President,” Forbes, October 20, 2017, <www.forbes.com/sites/salvatorebabones/2017/10/20/populism-chinese-style-xi-jinping-cements-his-status-as-chinas-first-populist-president>; Suheun Kim, “North Korea as a Populist Regime,” Democratic Erosion, October 23, 2020, <www.democratic-erosion.com/2020/10/23/north-korea-as-a-populist-regime>.

10 Marine Le Pen, “Dissuasion: Ni Élargie, Ni Concertée, Independante!“ [Deterrence: not extended, not concerted, independent!], L’Opinion, February 10, 2020, <www.lopinion.fr/edition/politique/marine-pen-rn-dissuasion-elargie-concertee-independante-211158> (translation by the authors). In France, nuclear weapons are an important pillar of national self-image and self-identification, termed “force de dissuasion nucléaire francaise” (French nuclear deterrent force), colloquially known as the “force de frappe” (strike force). See, for example, Stéfanie von Hlatky, “Revisiting France’s Nuclear Exception after its ‘Return’ to NATO,” Journal of Transatlantic Studies, Vol. 12, No. 4 (2014), pp. 392–404.

11 See David Gevarter, “Could European Populism Go Nuclear on NATO?” Council on Foreign Relations, July 19, 2018, <www.cfr.org/blog/could-european-populism-go-nuclear-NATO>.

12 William Walker, A Perpetual Menace: Nuclear Weapons and International Order (London, UK: Routledge Global Security Studies, 2012), pp. 12–13.

13 Gregory D. Koblentz, “Strategic Stability in the Second Nuclear Age,” Council on Foreign Relations, Council Special Report No. 71, November 2014, <https://cdn.cfr.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2014/11/Second%20Nuclear% 20Age_CSR71.pdf>.

14 James M. Acton, “Escalation through Entanglement: How the Vulnerability of Command-and-Control Systems Raises the Risks of an Inadvertent Nuclear War,” International Security, Vol. 43, No. 1 (2018), pp. 56–99.

15 Rachel E. Whitlark, “Nuclear Beliefs: A Leader-Focused Theory of Counter-Proliferation,” Security Studies, Vol. 26, No. 4 (2017), pp. 545–74; Matthew Fuhrmann and Michael C. Horowitz, “When Leaders Matter: Rebel Experience and Nuclear Proliferation,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 77, No. 1 (2015), pp. 72–87; Jonas Schneider, “The Study of Leaders in Nuclear Proliferation and How to Reinvigorate It,” International Studies Review, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2020), pp. 1–25; Christopher Way and Jessica L. P. Weeks, “Making It Personal: Regime Type and Nuclear Proliferation,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 58, No. 3 (2014), pp. 705–19; Elizabeth N. Saunders, "The Domestic Politics of Nuclear Choices: A Review Essay," International Security, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2019), pp. 146–84.

16 Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017); Karen Guttieri, “Populism on the World Stage,” S&F Sicherheit und Frieden, Vol. 37, No. 1 (2019), pp. 13–18; Yehuda Ben-Hur Levy, “The Undiplomats: Right-Wing Populists and Their Foreign Policies,” Center for European Reform, August 21, 2015, <www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/pdf/2015/pb_ybl_undiplo_21aug15-11804.pdf>; Catherine Kane and Caitlin McCulloch, “Populism and Foreign Policy: Deepening Divisions and Decreasing Efficiency,” Global Politics Review, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2017), pp. 39–52.

17 Jacques E. C. Hymans, The Psychology of Nuclear Proliferation: Identity, Emotions, and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

18 Hymans.

19 On the early evolution of Trump into a populist, see, for example, Uri Friedman, “What Is a Populist? And Is Donald Trump One?” Atlantic, February 27, 2017, <www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/02/what-is-populist-trump/516525>.

20 Frank Alexander Stengel, David B. MacDonald, and Dirk Nabers, “Conclusion: Populism, Foreign Policy, and World Politics,” in Frank Alexander Stengel, David B. MacDonald, and Dirk Nabers, eds., Populism and World Politics: Exploring Inter- and Transnational Dimensions (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 368.

21 See Cas Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist,” Government and Opposition, Vol. 39, No. 4 (2004), p. 544. Because of its definitional elusiveness, there is a debate on whether populism should be classified as an ideology at all.

22 Hymans, Psychology of Nuclear Proliferation; Margaret G, Hermann, “Explaining Foreign Policy Behavior Using the Personal Characteristics of Political Leaders,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 1 (1980), pp. 7–46; Daniel L. Byman and Kenneth M. Pollack, “Let Us Now Praise Great Men: Bringing the Statesman Back in,” International Security, Vol. 25, No. 4 (2001), pp. 107–46; Herbert C. Kelman, “The Role of the Individual in International Relations: Some Conceptual and Methodological Considerations,” Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 24, No. 1 (1970), pp. 1–17. See also David Cadier, “How Populism Spills over into Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Europe, January 10, 2019, <https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/78102>.

23 Byman and Pollack, “Let Us Now Praise Great Men,” p. 134.

24 See, for example, Rogers Brubaker, “Populism and Nationalism,” Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 26, No.1 (2020), pp. 44–66.

25 Brubaker, “Populism and Nationalism.”

26 Jordan Kyle and Brett Meyer, “High Tide? Populism in Power 1990–2020,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, February 7, 2020, <https://institute.global/sites/default/files/2020-02/High%20Tide%20Populism%20in%20Power%201990-2020.pdf>, p. 9.

27 This resembles Hymans’s description of oppositional nationalists as articulating a “stark black-white dichotomization of ‘us against them’.” See Hymans, The Psychology of Nuclear Proliferation, p. 25. This polarization places nationalist populism squarely in conservative US policy discourse. See J. Peter Scoblic, U.S. vs. Them: How a Half Century of Conservatism Has Undermined America's Security (New York, NY: Viking, 2008).

28 There are many examples. In the United States, Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan is the hallmark of backward-oriented policies. In Russia, Putin “[h]as skillfully appealed to tsarist and Soviet nostalgia to emphasize Russia’s rightful role as a great power.” Erdogan’s 2014 campaign slogan was “National Will, National Power.” See Angela Stent, Putin’s World: Russia against the West and with the Rest (New York, NY: Twelve, 2019), p. 42; Emre Erdogan and Sezin Öney, “And the Winner of Turkey’s Presidential Election is … Populism,” Washington Post, August 8, 2014, <www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/08/08/and-the-winner-of-turkeys-presidential-election-is-populism>.

29 T.G. Carpenter, “The Populist Surge and the Rebirth of Foreign Policy Nationalism,” SAIS Review of International Affairs, Vol. 37 (2017), pp. 33–46.

30 Kyle and Gultchin, “Populists in Power around the World,” p. 18.

31 Carpenter, “Populist Surge.”

32 Francis Fukuyama, “The Rise of Populist Nationalism,” Credit Suisse Research Institute, January 23, 2018, <www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/future-of-politics.pdf>.

33 Guttieri, “Populism on the World Stage.”

34 Kyle and Meyer, “High Tide?” p. 4.

35 Electoral autocracies, unlike full autocracies, maintain an open, liberal, and democratic façade through elections and provide populists with the necessary tie to their constituency (see, e.g., Andreas Schedler, Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2006).

36 Fukuyama, “Rise of Populist Nationalism”; Kyle and Mounk, “Populist Harm to Democracy.”

37 Walker, Perpetual Menace.

38 Hugh Gusterson, “Nuclear Weapons and the Other in the Western Imagination,” Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1999), pp. 111–43.

39 See, for example, Josef Joffe, “Peace and Populism: Why the European Anti-nuclear Movement Failed,” International Security, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1987), pp. 3–40.

40 Kyle and Meyer, “High Tide?” p. 4.

41 India and Pakistan have been ruled by various prime ministers who could be described as populists. The 1998 tests by both countries took place when populists were in power. See Arundhati Roy, “The End of Imagination,” Outlook, August 3, 1998, <www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/the-end-of-imagination/205932>.

42 This is not to say that the rise of populism is simply based on perceptions. Rather, it is an indication of an estrangement between populations, on the one hand, and political parties and institutions, on the other hand, and an inability to address these issues in established forums. On how the financial crisis of 2008 fueled the rise of populism, see, for example, J. Lawrence Broz, Jeffry Frieden, and Stephen Weymouth, “Populism in Place: The Economic Geography of the Globalization Backlash,” International Organization, Vol. 75, No. 2 (2021), pp. 464–94, <www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/populism-in-place-the-economic-geography-of-the-globalization-backlash/98ED873D925E0590CB9A78AEC68BB439>.

43 Angelos Chryssogelos, “Populism in Foreign Policy,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 2017, <doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.467>.

44 As shown by the V-Dem Institute’s Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) Index. Anna Lührmann, Juraj Medzihorsky, Garry Hindle, Staffan I. Lindberg, “New Global Data on Political Parties: V-Party,” University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy Institute: V-Dem Briefing Paper, No. 9, October 2020, <www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/b6/55/b6553f85-5c5d-45ec-be63-a48a2abe3f62/briefing_paper_9.pdf>.

45 See Janne E. Nolan, Guardians of the Arsenal: The Politics of Nuclear Strategy (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1989).

46 Jeffrey G. Lewis and Bruno Tertrais, “The Finger on the Button: The Authority to Use Nuclear Weapons in Nuclear-Armed States,” CNS Occasional Paper 45/2019, James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, February 2019, p. 32, <www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Finger-on-the-Nuclear-Button.pdf>. See also Bruce Blair, “What Exactly Would It Mean to Have Trump’s Finger on the Nuclear Button?” Politico Magazine, June 11, 2016, <www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/06/2016-donald-trump-nuclear-weapons-missiles-nukes-button-launch-foreign-policy-213955>.

47 Elena Block and Ralph Negrine, “The Populist Communication Style: Toward a Critical Framework,” International Journal of Communication, Vol. 11 (2017), p. 182.

48 Kyle and Gultchin, “Populists in Power,” p. 17.

49 Guttieri, “Populism on the World Stage,” p. 13.

50 Alexey Arbatov, “When It Comes to Nuclear Weapons, Words Are Deeds,” Carnegie Moscow Center, February 9, 2015, <http://carnegie.ru/commentary/?fa=59007>.

51 William C. Yengst, Stephen C. Lukasik, and Mark A. Jensen, “Nuclear Weapons that Went to War,” DNA-TR-96, Defense Special Weapons Agency, October 1996. Daniel Ellsberg lists 25 attempts at nuclear coercion by the United States since 1945. See Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2017), pp. 319–22.

52 The exception to this rule appears to be Boris Johnson, who has been reluctant to refer to the UK nuclear deterrent as a symbol of strength or pride.

53 Fukuyama, “Rise of Populist Nationalism.”

54 Kyle and Gultchin, “Populists in Power,” p. 13.

55 Between January 2017 and November 2019, President Trump sent 55 tweets containing the word “nuclear.” By comparison, President Barack Obama during his eight-year tenure sent two tweets containing the term “nuclear” (both supportive of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action).

56 Diwali is the Hindu festival of lights. Quoted in “Our Nuclear Weapons Are Not for Diwali: PM Modi on Pak’s Nuclear Button Threat,” India Today, April 21, 2019, <www.indiatoday.in/elections/lok-sabha-2019/story/our-nuclear-weapons-are-not-for-diwali-pm-modi-on-pak-nuclear-button-threat-1506893-2019-04-21>.

57 Ece Toksabay, “Erdogan Says It’s Unacceptable that Turkey Can't Have Nuclear Weapons,” Reuters, September 4, 2019, <www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-nuclear-erdogan/erdogan-says-its-unacceptable-that-turkey-cant-have-nuclear-weapons-idUSKCN1VP2QN>.

58 Jeffrey Michaels and Heather Williams, “The Nuclear Education of Donald J. Trump,” Contemporary Security Policy, Vol. 38, No. 1 (2017), pp. 54–77; Amy Davidson Sorkin, “Donald Trump’s Nuclear Uncle,” New Yorker, April 8, 2016, <www.newyorker.com/news/amy-davidson/donald-trumps-nuclear-uncle≥.

59 James Wood Forsyth, Jr., “Nuclear Weapons and Political Behavior,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, Vol.11, No. 3 (2017), pp. 115–28.

60 Arbatov, “When It Comes to Nuclear Weapons.”

61 Vladimir Putin, “Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly,” March 1, 2018, <http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957>.

62 Ankit Panda, “At Indian General Election Rallies, Modi Beats the Nuclear Drums,” Diplomat, April 23, 2019, <https://thediplomat.com/2019/04/at-indian-general-election-rallies-modi-beats-the-nuclear-drums/>.

63 Dmitry Adamsky, “How the Russian Church Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb: Orthodoxy’s Influence on Moscow’s Nuclear Complex,” Foreign Affairs, June 14, 2019, <www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2019-06-14/how-russian-church-learned-stop-worrying-and-love-bomb>.

64 Interpretation of such loose talk is further complicated by contradictory messaging from within the administration. Thus, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson played down Trump’s rhetoric by saying the following day that Americans should have “no concerns about this particular rhetoric of the last few days.” Peter Baker and Choe Sang-Hun, “Trump Threatens ‘Fire and Fury’ against North Korea if It Endangers U.S.,” New York Times, August 8, 2017, <www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/world/asia/north-korea-un-sanctions-nuclear-missile-united-nations.html>.

65 Nolan, Guardians of the Arsenal.

66 Trump reportedly repeated the same points several times after. See Fred Kaplan, The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2020), pp. 261–63.

67 Oliver Meier, “The U.S. Nuclear Posture Review and the Future of Nuclear Order,” European Leadership Network, March 2, 2018, <www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/commentary/the-u-s-nuclear-posture-review-and-the-future-of-nuclear-order/>.

68 Kaplan, The Bomb, p. 271.

69 Kaplan, p. 271. See also Derek Seidman, “The Revolving Door Profiteer Who Helped Shape Trump’s Nuclear Policy,” LittleSis, April 16, 2018, <https://news.littlesis.org/2018/04/16/the-revolving-door-profiteer-who-helped-shape-trumps-nuclear-policy>; Tom Sauer, “The US Nuclear Posture Review Does Not Carry Trump’s Signature,” Defense News, February 8, 2018, <www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2018/02/08/the-us-nuclear-posture-review-does-not-carry-trumps-signature/>; Kaplan, pp. 270–84.

70 In March 2015, the Russian ambassador to Denmark said that Russia would threaten Danish Navy ships with nuclear weapons should Denmark commit such vessels to NATO’s missile-defense efforts. See Teis Jensen, “Russia Threatens to Aim Nuclear Missiles at Denmark Ships if It Joins NATO Shield,” Reuters, March 22, 2015, <www.reuters.com/article/us-denmark-russia/russia-threatens-to-aim-nuclear-missiles-at-denmark-ships-if-it-joins-nato-shield-idUSKBN0MI0ML20150322>.

71 Department of Defense, “2019 Missile Defense Review,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, January 17, 2019.

72 David E. Sanger and William J. Broad, “Trump Vows to Reinvent Missile Defenses, but Offers Incremental Plans,” New York Times, January 17, 2019, <www.nytimes.com/2019/01/17/us/politics/trump-missile-defense-pentagon.html>.

73 Vladimir Isachenkov, ”Russia Warns US Missile Defense Plans Will Fuel Arms Race,” Associated Press, January 18, 2019, <https://apnews.com/98f4ebc83c174cfb9d40474e61b1a656>.

74 Thomas Grove, “Putin Says Russia Was Ready for Nuclear Confrontation over Crimea,” Reuters, March 15, 2015, <www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-putin-yanukovich/putin-says-russia-was-ready-for-nuclear-confrontation-over-crimea-idUSKBN0MB0GV20150315>.

75 Richard Sisk, “Interviews Reveal Chaos at Incirlik on Night of Coup Attempt in Turkey,” Military.com, August 3, 2016, <www.military.com/daily-news/2016/08/03/interviews-reveal-chaos-incirlik-night-coup-attempt-in-turkey.html>.

76 See the tweet by Jon B. Wolfsthal, cited in “Former Member of Obama's NSC Says Mattis Has Inserted Himself in the Nuke Chain of Command,” Daily Kos, December 21, 2018, <www.dailykos.com/stories/2018/12/20/1820616/-Former-Member-of-Obama-s-NSC-Says-Mattis-Has-Inserted-Himself-in-the-Nuke-Chain-of-Command>. In the closing days of the Nixon presidency, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger likewise asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to run any “unusual orders” from the president by him, apparently to prevent a nuclear launch on impulse by an unfit commander-in-chief. See Kaplan, The Bomb, pp. 289–329, 344–45.