ABSTRACT

Even if most European countries have not yet joined the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), the treaty has been salient in a number of national settings. In the Netherlands, the TPNW enjoys broad societal appeal, and the Dutch parliament has, on a number of occasions, called on the government to explore options for joining the treaty. In this piece, we empirically study Dutch attitudes toward joining the TPNW. Our findings indicate that a majority of the Dutch would prefer to accede to the TPNW only if nuclear-weapon states or other NATO allies also joined, although unilateral accession received relatively strong support among the youngest respondents, women, and voters supporting the left-wing parties. The most popular option is to join the TPNW at the same time that the nuclear-weapon states do, which seems to be a rather distant prospect in the current international-security environment.

Introduction

On July 7, 2017, delegates at the headquarters of the United Nations in New York concluded negotiations on the first international agreement to ban nuclear weapons completely. To the satisfaction of many pro-disarmament governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the resulting Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was adopted with an overwhelming majority of votes. The adoption of the treaty was a major win for the NGOs, especially the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which has been heavily invested in lobbying for the treaty before and after its adoption.Footnote1 By late 2020, the treaty had attracted 50 ratifications; it entered into force on January 22, 2021. Some countries were quick to sign and ratify it, while others dismissed it entirely. The nuclear-weapon states, acting in the framework of the P5 grouping, issued a statement vowing never to join the treaty.Footnote2 Because the treaty itself has few consequences for its parties and mainly seems to be a statement of political principles toward nuclear disarmament, it is starkly different from other treaties governing nuclear weapons.Footnote3 However, within a small group of countries, the treaty’s adoption remains a contentious political issue on the domestic agenda.

Often lost in these debates are the voices of those who hold the ultimate power in democratic countries: the voters. In this article, we present the findings of a new public-opinion survey that examined citizens’ attitudes toward the TPNW in the Netherlands, the only country that attended the treaty negotiations and then voted against its adoption.Footnote4 Today, the Netherlands is one of the countries where accession to the treaty remains the subject of domestic debate. While Dutch representatives have traditionally shown a strong interest in nuclear arms control and disarmament, the small Western European country also hosts US nuclear weapons on its territory.Footnote5 Lately, local NGOs have been urging the Dutch government to opt out of its nuclear-sharing arrangement with Washington and join the TPNW, often citing popular support for a world without nuclear weapons.Footnote6

Arguably, the accession of the Netherlands could be a turning point for the TPNW, since the Netherlands would be the first NATO member state to accede to the treaty. However, for European NATO members, joining the TPNW would not be cost free. Past surveys of public opinion have showed Dutch citizens’ support for accession to the TPNW, but mostly without inquiring into whether there are conditions or circumstances that would favor or disfavor such a decision.Footnote7 We were therefore interested in learning how the Dutch think about the circumstances under which their country should join the TPNW; we sought to do this by offering them different options. This question is important for policy makers, since they (and their citizens) can expect an increasing barrage of pro-TPNW messaging by the activists and TPNW parties.Footnote8 Policy makers should understand how the citizens unpack the complexities surrounding the treaty, and whether “joining the TPNW” means for them “joining the TPNW now.”

To that end, we asked 1,603 Dutch respondents under what conditions their country should join the treaty. In addition, we looked at how political party support, age, gender, and education shaped their views. Our findings indicate that, while only a very small part of the public categorically rejects Dutch accession to the TPNW, citizens are split in their opinions on the circumstances under which the treaty should be signed. The option that received the most support among the respondents was to accede to the TPNW but only if all nuclear-weapon states also joined. A majority of the population opposed unilateral accession, even though this option received relatively strong support among the youngest respondents, women, and voters supporting the left-wing parties.

The article proceeds as follows: First, we highlight the particularities of the Dutch position toward nuclear disarmament in general and the TPNW in particular. Second, we present the design of our survey and its results. Third, we discuss the potential implications of our findings for the future of European participation in the TPNW.

The Dutch setting

The Netherlands is a country with a peculiar stance on nuclear weapons. On one hand, it is a faithful member of NATO, which declares that, “as long as nuclear weapons exist, it will remain a nuclear alliance.”Footnote9 Moreover, the Netherlands is one of the five European NATO countries hosting US nuclear weapons on its soil (along with Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Turkey), even though the Dutch government officially neither acknowledges nor denies this arrangement.Footnote10 On the other hand, the Dutch government has traditionally been a proponent of the total elimination of nuclear weapons. For example, the most recent security strategy of the Netherlands states that “our ultimate goal remains a world without nuclear weapons.”Footnote11 Yet the same document also adds that “[t]he Netherlands is dependent on nuclear deterrence for its own security. It, therefore, advocates a balanced approach to nuclear disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation.”Footnote12 The 2017–21 Coalition Agreement among the parties in the governing coalition stated that the government “actively contributes, within the framework of alliance commitments, to a world free of nuclear weapons.”Footnote13 One could argue that the Dutch government has been aiming to strike a difficult balance between the ethical perspective, in which nuclear weapons should be eliminated as soon as possible, and the political-strategic perspective, in which it understands the security dilemmas involved and tries to use its position as a state hosting US nuclear weapons to increase its influence in global debates over nuclear disarmament.Footnote14

For quite some time, the Dutch government has subscribed to a progressive, step-by-step approach to nuclear disarmament, which means achieving “global zero” through gradual multilateral measures within existing international frameworks. In line with the broader conception of Dutch foreign policy, the key element of this approach has been the strengthening of the international legal order.Footnote15 Being a relatively small state, the Netherlands traditionally favors multilateral, cooperative approaches to prevent the establishment of “the law of the strongest” as a guiding principle of the world order.

Besides the traditional focus on constructively participating in all relevant multilateral forums, another factor influenced the active participation of the Netherlands in the TPNW negotiations: influential grassroots pressure from NGOs mobilizing public opinion and parliament. In the 1970s and 1980s, Dutch NGOs were able to mobilize large parts of the Dutch population in mass rallies against the planned stationing of US nuclear missiles in the Netherlands, as a part of the popular movement called “Hollanditis” in the Dutch academic literature.Footnote16 In recent years, following ICAN's “humanitarian initiative,” which explicitly sought to shift public opinion in countries protected by the US nuclear umbrella,Footnote17 Dutch NGOs have tried to resurrect this popular anti-nuclear sentiment in the country. In recent public-opinion polls, a clear majority of Dutch citizens called for the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from the countryFootnote18 and overwhelmingly rejected the possibility of a resumption of nuclear testing in NATO countries.Footnote19 In 2015, a coalition of Dutch NGOs collected more than 45,000 signatures of Dutch citizens to request a parliamentary debate on a national prohibition of nuclear weapons, which would entail “a comprehensive ban on use, possession, development, production, financing, stationing or transport of nuclear weapons under any circumstances and on the assistance with or encouragement of prohibited activities.”Footnote20 Public pressure on the Dutch parliament consequently resulted in a parliamentary demand for the government to participate in the TPNW negotiations.Footnote21

These were the key reasons why the Netherlands joined the negotiations for the TPNW between 2013 and 2017, despite pressure from other NATO member states not to do so.Footnote22 Following the general preference for multilateralism in its foreign policy, the government held the position that the Netherlands should be engaged in the field of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation through taking part in all relevant international forums. In particular, in the TPNW negotiations, the Netherlands tried to ensure that the new treaty would include sufficient references to the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), particularly its verification system, so that the TPNW would complement the NPT rather than undermine it.Footnote23

During the final vote in the TPNW negotiations, the Netherlands was the only participating country that voted against the adoption of the treaty. In its explanation of this vote, the Dutch government identified three reasons for opposing the treaty: the TPNW obligations are incompatible with Dutch membership in NATO; the TPNW lacks robust verification provisions; and the TPNW lacks sufficient references to the NPT and thus could undermine the key instrument of nuclear nonproliferation.Footnote24 Yet the public and parliamentary debate on nuclear disarmament and the possibility of the Netherlands joining the TPNW (actively encouraged by various Dutch NGOs) has continued to this day.

Survey design and results

It was against this backdrop that, in September 2020, we launched a public-opinion survey to study Dutch views on the TPNW. We worked with Kieskompas, one of the most reputable Dutch polling companies, to distribute the survey to a panel of 1,603 Dutch adults. The panel was stratified by age, gender, education, and region to approximate the adult population of the Netherlands. To correct for sociodemographic biases that existed in the initial sample and after survey participation, we subsequently weighted the data using iterative proportional fitting (IPF) and poststratification procedures on both demographic (age, sex, education, and region) and political variables (who the respondents say they voted for during the national elections in March 2017).Footnote25 The weighting procedure yields a data set representative of the Dutch adult population with a maximum margin of error of 5.1 percent.Footnote26

We asked the respondents for their views on five options for joining the TPNW: (1) joining only when all nuclear-weapon states join; (2) joining only when the United States joins; (3) joining only when other European NATO members join; (4) never joining; or (5) joining regardless of what other allies do. Each option was assessed on a six-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”Footnote27 To provide a more straightforward interpretation of our data, we divided the six responses into two categories: “opposed” (1–3) and “in favor” (4–6).

Our results show a strong heterogeneity in public support for different scenarios. As we show in , only 13 percent of respondents felt that the Netherlands should never join the TPNW. Fifty-nine percent supported joining the treaty only when all nuclear-weapon states joined, and 49 percent agreed with the idea of acceding to the treaty only together with other NATO allies. Forty-eight percent of respondents agreed with the view that the Netherlands should join regardless of what other countries do.

Table 1. Percentage of respondents opposed and in favor in each scenario

In line with previous public-opinion polls in which Dutch citizens expressed their support for joining the TPNW,Footnote28 only a very small percentage of respondents in our survey categorically rejected Dutch accession to the ban treaty. However, our findings also suggest that Dutch citizens are split in their opinion on the circumstances under which the treaty should be signed. A slight majority of the Dutch seem to oppose unilateral action—acceding to the TPNW without nuclear-weapon states or other NATO allies. An overwhelming majority of respondents rejected the option of joining the agreement together with Washington, perhaps highlighting the declining trust in transatlantic cooperation in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency.Footnote29

The most popular option was to accede to the TPNW, but only together with the nuclear-weapon states; the level of support for this option was almost 10 percentage points higher than for the second most popular choice, joining the treaty alongside other European NATO countries. It is worth noting that, at present, the former is clearly an unrealistic option given the current international-security environment and the dismissive attitude of the nuclear-weapon states toward the treaty. To some extent, the views of the Dutch public resemble general attitudes toward global nuclear disarmament: while citizens in most countries express their support for a world without nuclear weapons, and may support intermediate steps such as a nuclear test ban,Footnote30 they are simultaneously skeptical that such a goal is realistically attainable in the current state of global politics.Footnote31

Our survey did not examine the extent to which the respondents understood that this is presently an unrealistic option. It is possible that some respondents may be genuinely convinced that it is a feasible course of action, perhaps because their knowledge of nuclear politics is not deep. These respondents may not want their country to have its hands tied (for example, in its choice of alliances) while others act unconstrained. Others may want to express aspirational support for nuclear disarmament. And yet another group may have chosen this option as a way of saving face—that is, endorsing multilateralism despite the fact that such a multilateral solution is not a viable pathway at the moment.Footnote32 Such a view also would be in line with the current Dutch government’s position—to strive for a world free of nuclear weapons but to be covered by a nuclear alliance as long as nuclear weapons exist.Footnote33 For these respondents, the support for multilateralism is a reflection of the complicated political nature of global nuclear disarmament.

Unilateral accession?

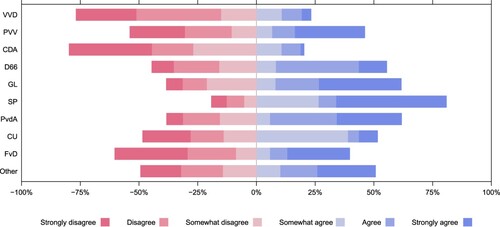

Let us now look more closely at the last scenario (unilateral accession regardless of what allies do), which is the preferred position of the disarmament NGOs. Here we see some interesting differences along political party lines.Footnote34 This scenario was viewed favorably by 48 percent of our respondents. The Netherlands has a multiparty system, in which more than a dozen parties are represented in the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer—TK). At the time of the study, four center-right parties formed the governing coalition: the culturally liberal but economically conservative People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), the right-wing Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), the liberal Democrats 66 (D66), and the religious-centrist Christian Union (CU). shows the differences in the support for unilateral accession among the voters supporting these parties.

In particular, we see that there are five political parties in which the majority of supporters agree with unilateral accession: the then-opposition parties Green Left (GL), the Socialist Party (SP) (representing far-left politics), and the Labor Party (PvdA) (representing center-left voters), and the two smaller coalition parties, D66 and CU. The three left-leaning opposition parties traditionally have been at the forefront of support for nuclear disarmament in the Netherlands. In the current House of Representatives, following the March 2021 elections, they hold less than one-fifth of the seats.Footnote35

The voters supporting the former coalition (the four center-right parties mentioned above) appear firmly opposed to unilateral accession, with 67 percent opposing it. In this regard, the voters and their representatives seem to share a very similar position. The Dutch government has recently rejected the idea of unilateral accession to the TPNW and has repeatedly underlined the need for cooperative, multilateral solutions. Coalition voters were most in favor of accession to the TPNW only when all nuclear-weapon states join as well. However, a slight majority of the voters supporting the religious-centrist CU, the smallest coalition party at the time of the study (currently occupying five seats in the 150-seat TK), were in favor of unilateral accession (52 percent of voters), as were a small majority of the voters supporting D66 (55 percent of voters), the second smallest coalition party at the time.

Among voters supporting opposition parties at the time, unilateral accession was the most strongly favored option overall as well. The voters supporting the opposition’s far-right parties—the Party for Freedom (PVV) and the Forum for Democracy (FvD)—also oppose unilateral accession to the TPNW. Voters supporting these parties are, however, also among the respondents who are most in favor of the option of not acceding to the treaty at all. Hence, their rejection of unilateral accession should be interpreted not as a preference for a multilateral solution but rather as a more general rejection of the overall treaty arrangement, in line with the far-right, more authoritarian political orientation of these parties.

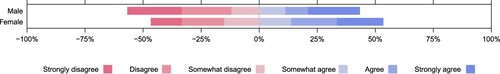

In addition, there appears to be a slight gender gap in the level of support for the unilateral accession to the treaty. While a majority of Dutch men (about 57 percent) in our survey oppose the idea of accession without regard for allies, 53 percent of Dutch women support such a step. We show these results in .

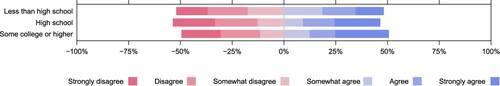

shows the differences between groups when broken down by the highest level of education the respondents achieved. Interestingly, there is no significant variation across educational groups. The respondents with at least some college education are slightly more likely to be in favor of unilateral accession—50 percent of them support this approach, compared with 47 percent of those with a high-school education and 48 percent of those with less than a high-school education—but generally there are small differences across educational groups.

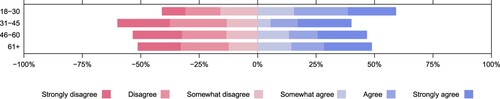

The only age group where a majority supports joining the TPNW without regard for the action of other countries is the 30-or-younger group (see ). We see that the respondents from this youngest generation are much more likely to support unilateral accession (59 percent in favor), whereas in the group between 31 and 45 years, 60 percent oppose unilateral accession. In the older age groups, the supporters and opponents of unilateral accession are more equally split. In the age groups between 31 and 60, the most popular option is to accede together with the nuclear-weapon states. For those above 60, accession only with fellow NATO member states is the top choice, closely followed by the preference to accede only together with the nuclear-weapon states, just as with those between 31 and 60 years of age. This suggests that the historical experience with the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s or the Cold War experience of nuclear drills drives support for anti-nuclear measures only to a very limited degree.

Since the Dutch government regularly presents its nuclear-weapon policy in the context of NATO doctrine on nuclear deterrence,Footnote36 we briefly turn to the option of joining the TPNW together with other European NATO states. This option received majority support among the voters supporting all parties except the far-right PVV and FvD, the PvdA, and the CU. (There, however, only a slight majority, 51 percent, disagreed.) The opposition of the far right is not surprising given that these parties are quite disdainful of the Netherlands’ engagement in alliances. Accession together with other NATO allies also has slight majority support among women (52 percent), whereas men are more likely to oppose it (53 percent). Finally, this option received strong majority support from the oldest respondents (57 percent support among those over 60 years of age), and roughly equally strong opposition from those between 46 and 60 years. The respondents who are 45 years of age or younger are roughly equally split on this option: 51 percent oppose it among respondents 18–30 years old, whereas 51 percent of respondents 31–45 years old are in favor.Footnote37

Conclusion

Our findings are in line with earlier polls conducted by some NGOs, which showed that the Dutch public is mostly sympathetic toward the idea of their country acceding to the TPNW. However, we also found that the respondents differ significantly on the conditions under which their country should join the treaty. While only a very small percentage of the Dutch population completely rejects TPNW accession, the option that received the most support in our survey is to join the treaty together with the nuclear-weapon states.

As we discussed earlier in this article, this option is unrealistic in the current international-security environment. But it does fit the traditional view of Dutch foreign policy as torn between idealism and pragmatism.Footnote38 In the case of nuclear weapons, pragmatism—which would presume that the TPNW will not rid the world of nuclear weapons as long as the countries possessing these weapons do not join the treaty—appears to prevail in the court of Dutch public opinion.

Nevertheless, our findings certainly do not preclude the possible shift of the majority opinion toward more realistic accession options. Research on the formation of attitudes toward foreign and defense policy shows that public opinion in these matters is dynamically shaped by cues from political representatives, media, international organizations, and foreign elites.Footnote39 The options to accede to the TPNW without preconditions and to join the TPNW alongside other European NATO allies both received close to 50 percent support. Future events, particularly developments in other NATO countries, may turn the tide toward majority support for accession under less restrictive conditions.

This may be particularly relevant in the case of Germany, where the Social Democrats and the Greens have recently reignited the debate about the future participation of the country in NATO’s nuclear-sharing arrangement.Footnote40 With the left-wing and Green parties most likely gaining a bigger role in the government as a result of the September 2021 elections, Germany may again be tempted to explore the possibility of the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from its territory and the country’s subsequent accession to the TPNW. Arguably, such a dramatic change in the long-standing practice of nuclear sharing in a key European NATO state would give the proponents of disarmament in the Netherlands a boost and make the option of early accession to the TPNW much more appealing for the Dutch public.

These findings show that in order to obtain a more comprehensive picture of citizens’ attitudes, it is crucial to go beyond asking about the general support for the treaty by investigating support for different accession scenarios. Disaggregating public opinion in this way provides scholars, activists, and policy makers with pertinent information about those respondents who would be content to join the treaty right away and those who are nominally in favor of the treaty but would support joining it only under conditions that are either difficult to fulfill or unrealistic.

Future research should employ cross-national comparative designs to see to what extent our findings hold in NATO countries other than the Netherlands, particularly the other four European states that host US nuclear weapons on their territory. Moreover, future studies should also use experimental designs to examine whether (and how) public attitudes toward the ban treaty can change. For example, a recent study of public views on the TPNW in Japan suggests that the Japanese public is mostly immune to “elite cues” that attempt to sway public opinion toward opposing accession to the treaty.Footnote41 At the same time, a similar study recently found that attitudes of US citizens toward the TPNW can be shifted through negative messages from political elites and group cues.Footnote42 Understanding of the impact of these persuasive messages in different national and sociodemographic contexts could be useful for both policy makers and NGOs interested in strengthening public support for nuclear disarmament and individual initiatives that bring the world closer to that goal.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Motoko Mekata, “How Transnational Civil Society Realized the Ban Treaty: An Interview with Beatrice Fihn,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2018), pp. 79–92.

2 “P5 Joint Statement on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” October 24, 2018, <www.gov.uk/government/news/p5-joint-statement-on-the-treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons>. Because the five nuclear-weapon states recognized by the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—are also the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, they sometimes are known collectively as the “P5.”

3 For an analysis of the humanitarian push in favor of the TPNW, see Rebecca Davis Gibbons, “The Humanitarian Turn in Nuclear Disarmament and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 25, Nos. 1–2 (2018), pp. 11–36. For the reasoning of many countries opposed to joining the treaty precisely because joining would have practical or political consequences for them, see Michal Onderco and Andrea Farrés Jiménez, “A Comparison of National Reviews of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” EUNPDC Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Papers, No. 76, 2021, <https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/eunpdc_no_76.pdf>.

4 Kingdom of the Netherlands, “Explanation of Vote of the Netherlands on Text of Nuclear Ban Treaty,” July 7, 2017, <https://s3.amazonaws.com/unoda-web/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Netherlands-EoV-Nuclear-Ban-Treaty.pdf>. For a broader discussion of the Dutch position on the TPNW, see Ekaterina Shirobokova, “The Netherlands and the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 25, Nos. 1–2 (2018), pp. 37–49.

5 Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons, 2019,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 75, No. 5 (2019), pp. 252–61, <https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2019.1654273>.

6 PAX No Nukes, “Verbied Kernwapens in Nederland. Voorstel Aan De Tweede Kamer. Burgerinitiatief Teken Tegen Kernwapens [Bijlage Bij Kamerstuk 34419 Nr 1]” [Ban nuclear weapons in the Netherlands. Proposal for the House of Representatives. Citizens’ initiative sign against nuclear weapons (attachment to the Chamber Record 34419 Nr 1)], February 24, 2016 , <https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/blg-688950>. Citizens’ Initiatives in the Netherlands are bottom-up instruments that allow 40,000 or more Dutch voters to request a motion to be debated in the Dutch House of Representatives.

7 But see ICAN, “NATO Public Opinion on Nuclear Weapons,” January 2021, <https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ican/pages/234/attachments/original/1611134933/ICAN_YouGov_Poll_2020.pdf?1611134933>; Kjølv Egeland and Benoît Pelopidas, “European Nuclear Weapons? Zombie Debates and Nuclear Realities,” European Security, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2021), pp. 248–49.

8 Nick Ritchie and Alexander Kmentt, “Universalising the TPNW: Challenges and Opportunities,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2021), pp. 70–93.

9 NATO, “NATO’s Nuclear Deterrence Policy and Forces,” 2020, <https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50068.htm>.

10 Kristensen and Korda, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons, 2019.”

11 Government of the Netherlands, “Integrated International Security Strategy 2018–2022,” 2018, <www.government.nl/binaries/government/documents/reports/2018/05/14/integrated-international-security-strategy-2018-2022/NL_International_Integrated_Security_Strategy_2018_2022.pdf>.

12 Government of the Netherlands, “Integrated International Security Strategy.”

13 “Vertrouwen in De Toekomst. Regeerakkoord 2017–2021” [Trust in the future. Coalition Agreement 2017–2021], 2017, p. 47, <www.tweedekamer.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/regeerakkoord20172021.pdf >.

14 Sico van der Meer, “Nederlands kernwapenbeleid: Tussen ethiek en geopolitiek” [Dutch nuclear-weapon policy: between ethics and geopolitics], Clingendael Spectator, June 26, 2019, <https://spectator.clingendael.org/nl/publicatie/nederlands-kernwapenbeleid-tussen-ethiek-en-geopolitiek>.

15 Ben Knapen, Gera Arts, Yvonne Kleistra, Martijn Klem, and Marijke Rem, Attached to the World: On the Anchoring and Strategy of Dutch Foreign Policy (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011); Rudy B. Anderweg, Galen A. Irwin, and Tom Louwerse, Governance and Politics of the Netherlands, 5th ed. (London: Red Globe Press, 2020).

16 Remco van Diepen, Hollanditis: Nederland en het kernwapendebat 1977–1987 [Hollanditis: The Netherlands and the nuclear weapons debate, 1977–1987] (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2004).

17 David J. Norman, “Transnational Civil Society and Informal Public Spheres in the Nuclear Non-proliferation Regime,” European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 25, No. 2 (2018), pp. 486–510; Gibbons, “The Humanitarian Turn”; Tilman Ruff, “Negotiating the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and the Role of ICAN,” Global Change, Peace & Security, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2018), pp. 233–41.

18 ICAN, “One Year On: European Attitudes toward the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” 2018, <https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ican/pages/714/attachments/original/1575571450/YouGov_ICAN_EUNATOTPNW2018.pdf?1575571450>.

19 Stephen Herzog, Benoît Pelopidas, Jonathon Baron, and Fabrício Fialho, “Donald Trump Could Lose the Election by Authorizing a New Nuclear Weapons Test,” National Interest, June 23, 2020, <https://nationalinterest.org/feature/donald-trump-could-lose-election-authorizing-new-nuclear-weapons-test-163328>.

20 PAX No Nukes, “Ban Nuclear Weapons in the Netherlands,” p. 4. See also Selma Van Oostwaard, “Dutch Parliament Will Discuss a Nuclear Weapons Ban,” 2016, <https://nonukes.nl/dutch-parliament-will-discuss-national-ban-nuclear-weapons/>.

21 On the grassroots pressure in the Netherlands, see Peter Buijs, “The Influence of NVMP’s Medical-Humanitarian Arguments on Dutch Nuclear Weapons Politics: The Netherlands Can Make a Difference in Reaching a Nuclear Weapons-Free World,” Medicine, Conflict and Survival, Vol. 34, No. 4 (2018), pp. 313–23.

22 Van der Meer, “Dutch Nuclear-Weapon Policy.”

23 Kingdom of the Netherlands, “Explanation of Vote.”

24 Kingdom of the Netherlands.

25 For more information on the composition of the sample, see Appendix 1. While the weighting procedure has its limits with respect to the sample’s representativeness of the general population, it is a useful method for correcting sociodemographic biases and providing fairly reliable results in survey research. For example, our original sample was originally biased toward men, older respondents, and respondents with higher levels of education. A study by the Pew Research Center has shown that the inclusion of political benchmarks in weighting procedures results in bias reduction of nearly 50 percent when analyzing political opinions. See Andrew Mercer, Arnold Lau, and Courtney Kennedy, “For Weighting Online Opt-in Samples, What Matters Most?” Pew Research Center, January 26, 2018, <https://pewrsr.ch/3heqknn>.

26 The weighting procedure and resulting margins of error at the 95 percent confidence level took into account the complex sample in accordance with the guidance of the American Association for Public Opinion Research on reporting precision for nonprobability samples by including the design effect as an inflation factor. The weights have been trimmed at the 99.5th percentile so as to reduce the impact of the highest-weight outliers.

27 See Appendix 2 for the original Dutch wording of individual items in our survey.

28 See, for example, ICAN, “One Year On.”

29 Rem Korteweg, Christopher Houtkamp, and Monika Sie Dhian Ho, “Dutch Views on Transatlantic Ties and European Security Cooperation in Times of Geopolitical Rivalry,” Clingendael Institute, September 2020, <www.clingendael.org/publication/dutch-views-transatlantic-ties-and-european-security-cooperation>.

30 Herzog et al., “Donald Trump Could Lose the Election.”

31 Michal Smetana, Marek Vranka, and Ondrej Rosendorf, “Disarming Arguments: How to Get the Public to Support Nuclear Abolition,” Survival, Vol. 63, No. 6 (forthcoming).

32 We thank one of the anonymous reviewers of this paper for valuable comments and suggestions regarding the interpretation of these findings.

33 Government of the Netherlands, “Integrated International Security Strategy.”

34 The detailed results of our survey broken down by age, gender, educational attainment, and party supported are available in Appendix 3.

35 For the composition of the Dutch House of Representatives, see <www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerleden_en_commissies/fracties>.

36 In its recent report, the Dutch government’s Advisory Council for International Affairs also discussed the Dutch nuclear task in this framework. See Advisory Council on International Affairs, “Nuclear Weapons in a New Geopolitical Reality: An Urgent Need for New Arms Control Initiatives,” January 2019, <www.advisorycouncilinternationalaffairs.nl/documents/publications/2019/01/29/nuclear-weapons-in-a-new-geopolitical-reality>.

37 Full results for all answer options can be found in Appendix 3.

38 This dilemma is sometimes captured by the metaphor of “preacher vs. merchant.” For the paradigmatic statement, see Joris Voorhoeve, Peace, Profits and Principles: A Study in Dutch Foreign Policy (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1979).

39 Matthew A. Baum and Tim Groeling, “Shot by the Messenger: Partisan Cues and Public Opinion Regarding National Security and War,” Political Behavior, Vol. 31, No. 2 (2009), pp. 157–86; Katerina Linos, “Diffusion through Democracy,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 55, No. 3 (2011), pp. 678–95; Christopher Gelpi, “Performing on Cue? The Formation of Public Opinion toward War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 54, No. 1 (2010), pp. 88–116; Matt Guardino and Danny Hayes, “Foreign Voices, Party Cues, and US Public Opinion about Military Action,” International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Vol. 30, No. 3 (2018), pp. 504–16; Danny Hayes and Matt Guardino, “Whose Views Made the News? Media Coverage and the March to War in Iraq,” Political Communication, Vol. 27, No. 1 (2010), pp. 59–87; Shoon Murray, “Broadening the Debate about War: The Inclusion of Foreign Critics in Media Coverage and Its Potential Impact on US Public Opinion,” Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 4 (2014), pp. 329–50.

40 Rafael Loss, “Germany, the Tornado, and the Future of NATO,” European Council on Foreign Relations, 2020, <www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_germany_the_tornado_and_the_future_of_nato>; Oliver Meier, “German Politicians Renew Nuclear Basing Debate,” Arms Control Today, June 2020, <www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-06/news/german-politicians-renew-nuclear-basing-debate>; Michal Onderco and Michal Smetana, “German Views on US Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Public and Elite Perspectives,” European Security, <www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09662839.2021.1941896>. For a comparison of German and Dutch views on the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons, see Michal Smetana, Michal Onderco, and Tom Etienne, “Do Germany and the Netherlands Want to Say Goodbye to US Nuclear Weapons?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol.. 77, No. 4 (2021), pp. 215–21, <www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2021.1941603>.

41 Jonathon Baron, Rebecca Davis Gibbons, and Stephen Herzog, “Japanese Public Opinion, Political Persuasion, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2020), pp. 299–309.

42 Stephen Herzog, Jonathon Baron, and Rebecca Davis Gibbons, “Anti-normative Messaging, Group Cues, and the Nuclear Ban Treaty,” Journal of Politics (forthcoming), https://doi.org/10.1086/714924.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Demographics

Appendix 2

Survey Items and Translation

In 2017 werd in de Verenigde Naties een nieuw verdrag overeengekomen dat kernwapens verbiedt. Nederland heeft dit verdrag tot dusver niet ondertekend. Onder welke voorwaarden zou Nederland tot het verdrag moeten toetreden?

| 1. | Nederland zou alleen moeten toetreden als alle kernwapenstaten tot dit verdrag toetreden. | ||||

| 2. | Nederland zou alleen samen met de Verenigde Staten moeten toetreden. | ||||

| 3. | Nederland zou alleen samen met andere Europese NAVO-bondgenoten tot dit verdrag moeten toetreden. | ||||

| 4. | Nederland zou nooit tot dit verdrag moeten toetreden. | ||||

| 5. | Nederland zou tot dit verdrag moeten toetreden, ongeacht wat zijn bondgenoten doen. | ||||

| 1. | The Netherlands should only accede if all nuclear-weapon states accede to this treaty. | ||||

| 2. | The Netherlands should only accede together with the United States. | ||||

| 3. | The Netherlands should only accede to this treaty together with other European NATO allies. | ||||

| 4. | The Netherlands should never accede to this convention. | ||||

| 5. | The Netherlands should accede to this treaty, regardless of what its allies do. | ||||

| 1. | Helemaal niet mee eens – Strongly disagree | ||||

| 2. | Niet mee eens – Disagree | ||||

| 3. | Enigszins niet mee eens – Somewhat disagree | ||||

| 4. | Enigszins mee eens – Somewhat agree | ||||

| 5. | Mee eens – Agree | ||||

| 6. | Helemaal mee eens – Strongly agree | ||||