ABSTRACT

Investigating learning in ongoing classroom practices involves a number of methodological challenges. One main challenge, identified by scholars in sociocultural approaches, is how to take both the individual and the environment into consideration in analyses. Although the challenge we are addressing are methodological in character, the work of coming up with a transactional methodology requires philosophical and theoretical clarifications and here we use mainly the work of John Dewey. The main ambition of this article is to present and empirically illustrate a transactional research methodology – a package of analytical models and an analytical method – that fully recognize the dynamic relations between the individual and the environmental dimensions – how they interplay in the learning process and how certain learning outcomes result from that interplay. The three models we present concerns the trajectory of learning, how the influence of the individual and environmental dimensions on students learning can be understood and approached transactionally respectively the learning outcome in terms of what the person learn when (re)creating habits. The analytical method presented and illustrated is built upon a first person perspective on language use, which dissolves some of the methodological problems when investigating the individual dimension through in situ analyses.

Introduction

Investigating learning in ongoing classroom practices involves a number of methodological challenges. One main challenge is how to take both the individual and the environment into consideration. By the individual we mean the intra-personal, i.e. the individual’s knowledge, skills, perceptions, values, etc. By the environment we include the inter-personal, institutional and physical world. By learning, we here mean experiences that result in a developed repertoire of actions enabling the individual to coordinate their activities and the environment in a more specific and purposeful way. By learning outcome and learning content we mean acquired habits and the components that makes up a habit.

While most educational researchers are likely to agree that individual processes and the environment need to be taken into consideration, it is common for one of these aspects to be positioned as superior from the beginning and to predetermine the other, thereby causing different methodological problems. If the individual is the starting point, they tend to appear to be free to form their actions independent of the environmental context. If the starting point is the environmental context, it often appears to determine the individual’s actions and there is a tendency for individual differences to disappear (see Hodkinson et al., Citation2007). Rogoff (Citation1995) concluded that:

Even when both the individual and the environment are considered, they are often regarded as separate entities rather than being mutually defined and interdependent in ways that preclude their separation as units or elements (pp. 139-140).

In a research review of cultural psychology, Lehman et al. (Citation2004) arrive at a similar conclusion, arguing that, whereas most researchers within this field admit to a mutual relationship between culture and psychological processes, two different substantial bodies of research are treated as being entirely independent. These two areas relate to research into the ways that culture influences psychological processes on the one hand, and how psychological processes contribute to the origins and persistence of cultures on the other hand. Based on their review, the authors draw attention to the need for research “that focuses more fully on the dynamic relations between psychology and culture” (p. 705).

What we would therefore like to draw attention to in this article is the need for research methodologies that fully recognize the dynamic relations between the individual and the environmental dimensions – how they interplay in the learning process and how certain learning outcomes result from that interplay. We use the word interplay in a transactional understanding. Methodologically speaking, the transactional perspective implies that it is only in and through encounters with the environment that the meaning of the environment and the actions of the individual (including language use) becomes constituted and possible to analyze. Thus, when we use the term interplay it means that we make an analytical distinction between the environmental and the individual dimensions of the meaning that is transactionally created. We make this distinction because we are interested in creating knowledge of, if, and how a specific relationship between the dimensions affects the learning outcome. Although the term interplay has its obvious drawbacks, we have chosen to use it in order to emphasize that the relationship is a dynamic one, constantly changing as the encounters unfold.

In many approaches to learning, thinking and feeling, on the one hand, and action on the other, are treated as detached processes located in the two separate realms of the inner mind and outer reality, respectively. This kind of dualism means that the individual dimension can never be investigated through in situ studies, since the mind is hidden for an external observer. The dualistic view is particularly obvious in research adopting a cognitivist perspective, where learning is analyzed in terms of the development of mental structures and conceptual change. But many scholars have also warned that dualistic tendencies can be present also in sociocultural approaches (Garrison, Citation2001; Hodkinson et al., Citation2007; Jornet et al., Citation2016; Wertsch, Citation1998). Wertsch (Citation1998), for example, maintains that the term internalization, which is often used in sociocultural studies, can be misleading, because it:

[…] encourages us to engage in the search for internal concepts, rules, and other such entities that are quite suspect in the eyes of philosophers such as Wittgenstein […]. The construct of internalization also entails a kind of opposition, between external and internal processes, that all too easily leads to the kind of body-mind dualism that has plagued philosophy and psychology for centuries. (p. 48)

In line with Roth and Jornet (Citation2013, Citation2014) and Jornet et al. (Citation2016), we argue that John Dewey’s pragmatic philosophy, and especially his concept of transaction, makes it possible to overcome the dualistic tendencies of mainstream cognitivist but also of some sociocultural approaches to learning. Taking into consideration the many basic similarities between Vygotsky’s and Dewey’s theories of human experience (Roth & Jornet, Citation2014), and the terms of mediation and transaction (Garrison, Citation2001), we believe that Dewey’s transactional perspective is a fruitful way to continue the development of the sociocultural approach.

Although it is important to develop a non-dualistic theory and models of learning, there are many questions – what we here call methodological questions – concerning how to make empirical analyses of the interplay between the individual and cultural dimensions possible that also need close attention. In order to generate detailed knowledge about how the environmental dimension influences the learning outcome (acquired habits), it is necessary to do in situ studies as has been done within sociocultural approaches. The problems that occur are connected to the individual dimension and here it becomes crucial to come up with answers on a number of questions such as the following: how is it possible – through in situ studies – to observe and generate detailed knowledge about the individual dimension of learning in its interplay with the environmental dimension? And how does the interplay between the individual and the environmental dimension in one situation influence the learning in other situations?

In this paper, we thus put specific attention to the methodological challenges when it comes to studying learning in ongoing practice (in situ studies) and especially the above-mentioned questions. We we do so because we believe it can complement the above-mentioned attempts to develop the sociocultural approach. Our ambition is to present a methodology – a package of analytical models and method – that can deal with the interplay, transactionally understood, between the individual and the environment which also takes the question of continuity and change into consideration. By analytical models we here refer to models that can generate understandings and explanations of learning taking empirical findings as point of departure. By analytical methods we mean a systematic procedure to identify essential features and relationships, i.e. empirical findings (Wolcott Citation1994, p. 24). The material for the analyses – for the systematic procedure – are processed observational data, as for example, transcripts of classroom communication. The analytical method we present and illustrate here – practical epistemology analyses (PEA) – is built upon a first-person perspective on language use, and not on learning. This means that the analytical result (the empirical findings) do not say anything about learning, but only about meaning making in encounters with the world. It is only when the results of the analyses are inserted into a learning model that we can draw conclusions of interest to learning theory/research. The models that we present concerns the trajectory of learning, the content of learning, the continuity and change in the learning process respectively the influence and interplay between the individual and environmental dimension. The advantage of this package, as we see it, is that it facilitates a theoretical as well as a systematic and empirically grounded production of knowledge that is plead for by scholars.

PEA is based on Dewey’s and Wittgenstein’s first-person perspective on language, which contrasts with the third-person perspective used in cognitivist studies, and it is designed for handling the methodological questions in focus here. Some of the models presented here are based on Dewey’s concept of habit (“habitual action-in-environment”) and we believe that this concept is a crucial component in building a suitable methodology.

The presented methodology mainly draws on research conducted within the research environment SMED (Studies of Meaning-making in Educational Discourses) over the last 15 years. The research has been carried out in various educational settings, with different age groups and different forms of meaning-making (epistemological, moral, esthetic and practical).

Transactional models of learning

Although the challenges we are addressing are methodological in character, the work of coming up with an analytical methodology requires philosophical and theoretical clarifications. This section therefore starts with an exploration of some basic aspects of Dewey’s work on action as transaction and meaning making in transaction followed by a presentation of four models that constitute one part of the transactional methodology package. This section follows by a presentation of the second part of the package, namely the analytical method. The whole package is empirically illustrated in the subsequent section.

Action as transaction

Dewey’s theory of action is highly influenced by Darwin, in the sense that everything in the world is evolving and is in the process of constant change due to organisms’ adaptations to their environment (see, Dewey, Citation1909/1983). This means that “nature is viewed as consisting of events rather than substances” (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958, xi). In this evolving universe, the fundamental aspect of life is action: “the organism, is always active; that it acts by its very constitution, and hence needs no external promise of reward or threat of evil to induce it to act” (Dewey, Citation1932/1985, p. 289). The activity of organisms can be understood in terms of their functional coordination with their environment (see, Garrison, Citation2001). This coordinative process consists of an active phase – doing – and a passive phase – undergoing the consequences of action. The relation between actions and consequences is not causal and linear in a mechanistic sense, but rather reciprocal. Dewey holds that responses from the environment are not the start of action, but that they change the direction of the action that is already taking place (Dewey, Citation1932/1985). Actions change the environment and a shift of activity is a response to changing conditions in the environment. The functional dynamic coordination is a continuous back-and-forth process in which organisms continuously readjust their actions to a constantly changing environment.Footnote1 This is Dewey’s general model for functional coordination and is valid for all living organisms. However, when it comes to human beings, we also have to add changes in actions that are induced by new ambitions, purposes and ends in view of the acting individual.

In their influential work, Knowing and the Known, Dewey and Bentley refer to this way of understanding the reciprocal relationship, created in action, between the individual and the environment as transaction (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, pp. 101–102). In introducing this perspective, Dewey and Bentley’s intention was not to create a new ontology but rather a methodology for investigating action. This relational perspective implies that the activities of an individual can never be fully understood in isolation, because they are situated within and constituted by the environment. Dewey therefore speaks about “organism-in-environment-as-a-whole” (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991). The acting individual, fellow beings, other organisms, things and phenomena in the environment are not approached as isolated and autonomous, but rather as interdependent and mutual. It is important to notice that the human is here seen as being in relation to the environment already from birth. In this way, Dewey and Bentley set the transactional perspective in contrast to the mechanistic, inter-actional perspective where things are described in terms of linear and causal interconnections between the subject and the environment as independent, already known, entities that inter-act (see, Roth & Jornet, Citation2013).

What makes Dewey’s transactional perspective particularly useful for in situ studies is that it takes radical account of the fact that the only way to acquire information about human beings is through their actions. The transactional methodology takes as point of departure the way we live through events in real life and uses what we could call a first-person perspective on interaction and language use (see further below). Consequently, in transactional investigations, the focus is on the encounters between human beings and their environment that occur in an activity, and what becomes the consequences of these encounters in terms of acquired habits. The process of encountering is described in terms of the relations between the participants that arise in the events and the functions of these relations.

Meaning making in transaction

Meaning making is a crucial part of human life. Generally speaking, in a transactional perspective, meaning emerges as a consequence of individuals’ coordinative actions, although the reason for the individual to make this coordination can be a change in the environment (physical or cultural). The perspective is in this sense a non-anthropocentric perspective. Dewey illustrates this way of approaching the interplay with a trade (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, p. 242). It is in and because of the transaction that one participant becomes a seller and the other a buyer. It is also in the nature of the transaction that the things bought and sold become goods, as well as all the other parts becoming what they are in accordance with how they participate in the process and the changes they undergo. It is in the transactional process that humans and their environment obtain their meaning. In this way, meaning is not treated as something that exists within things themselves, or in the minds of human beings, but as indissolubly connected to the relations that are created in and by action – meaning is literally something we do. Thus, meanings are practical in the sense that we use them as a means to an end; when used for a purpose something acquires meaning. In other words, meaning emerges in the process of doing and undergoing the consequences of action. As a consequence, meaning “is not indeed a psychic existence; it is primarily a property of behavior” (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958, p. 179).

Although we do not have space to elaborate on it in depth here, it is important to recognize that the pragmatist perspective on meaning and language usage is a bodily perspective (see further Andersson et al., Citation2018). Both James (Citation1912/1976), in coining the term pure experience, and Dewey, who uses the term anoetic experience (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958), have suggested that all our knowledge, concepts and so on have their origin in bodily feelings. The anoetic experiences, which is a result of transactions with the environment (physical and cultural), becomes sedimented in the meanings that result from our reflections on them. This means that meaning is relational and embodied (felt). James and Dewey’s claim about the bodily origins of our meanings has been taken further by scholars like Mark Johnson (Citation2007), who states that even: “Our most abstract concepts (such as cause, necessity, freedom, and God) have no meaning without some connection to felt experience” (p. 93). Similarly, Roth and Jornet (Citation2014) hold that: “experience includes an affective coloring that cannot be separated out from its practical and intellectual colorings” (p. 116).

Meaning is grounded in anoetic experience, in the immediate qualities of organic activities and receptivities. However, “meanings do not come into existence without language, and language implies two selves involved in a conjoint or shared undertaking” (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958, pp. 298–299). In the use of language, that is, in communication and reflection (communication with ourselves), the anoetic experiences are transformed (see, Andersson et al., Citation2018) and previously acquired and created meanings will be refined, changed and elaborated (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958, p. 166).

When communicating meaning, individuals coordinate their activities by making something in common. Meaning making is therefore to be perceived as a fundamentally social process (see, Garrison, Citation1995).

Habits and the trajectory of learning model

For decades, there has been a shift in learning research from cognitivist approaches where learning and knowing have been described in terms of structures and processes of an inner mind to a set of approaches that collectively can be named “situated cognition” emphasizing “the dynamic coupling between intelligent subject and its environment” (Roth & Jornet, Citation2013, p. 464). As cognition has strong connection to the individual mind, we believe that a fruitful way to continue this shift would be to get rid of the concept of “cognition” all together and replace it with the concept of “habit” as the unit of learning. The strength of the concept of habit is that it helps us to avoid the dualistic trap by placing learning and knowing in the sphere of action rather than in the mind: “The scientific man and the philosopher like the carpenter, the physician and politician know with their habits, not with their ‘consciousness.’ The latter is eventual, not a source” (Dewey Citation1922/2002, p. 182–183). Knowing can be understood as our responses to certain situations through specific habits, which include language games: specific ways of using language and body in relation to specific activities and life forms (Wittgenstein, Citation1953/1997). And learning can be understood as transforming and/or creating new habits, where habits are perceived predispositions to act and respond in a certain way in a specific situation. According to Dewey, habits permeate existence:

All habits are demands for certain kinds of activity; and they constitute the self. In any intelligible sense of the word will, they are will. They form our effective desires and they furnish us with our working capacities. They rule our thoughts, determining which shall appear and be strong and which shall pass from light into obscurity. (MW 14:21)

Learning can thus be described in terms of (trans)actions and meaning making resulting in a more developed and specific repertoire for coordinating activities and the environment. This development and specification can be described as the learner increases in complexity (Semetsky, Citation2008, p. 86) and the repertoire of actions can be described as acquired habits.

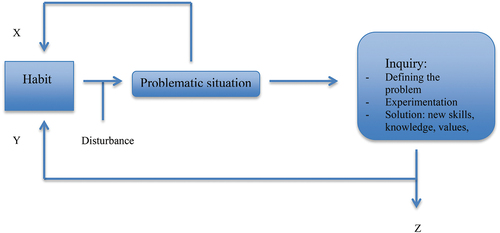

We mainly start to think when our habitual ways of acting are disturbed, i.e. situations when the habits no longer give an automatic response to a change in the environment or a wish, need etc., and we are caught up in a problem and need to create a new way of coordinating with the environment in an activity. The disturbance awakens us from our non-reflectivity to the extent that we need to re-think and re-body. Some of these disturbances can be handled within the habit that was disturbed, but some disturbances force us into what Dewey (Citation1938/1986) calls inquiry. In , below, the theoretical model of learning trajectory (LT-model) is illustrated. The LT-model has been developed by Östman et al. (Citation2019, p. 131) and demonstrates that a problematic situation occurs when a habitual way of corresponding with the environment is disturbed (Dewey, Citation1938/1986). Many different kinds of disturbances can create distinct and problematic situations: practical, intellectual, moral etc. (see, Östman et al., Citation2019, pp. 132–134). The result of a disturbance can be a consolidated or a transformed habit, or even the start of a new habit. According to the LT-model, a learning trajectory generally starts by individuals sensing a problem that makes them unable to move forward in their activity. They might find a way of solving the problem by using their own repertoire of habits. In other times they may need to start an inquiry, to reflect and discuss with peers and formulate ideas and plans for solving the problem. During this process, the problem itself becomes clearer and individuals start to define the problem. In this phase they might need to search for new information and ask others for advice. Finally, they will need to apply the result of their work to the problematic situation in order to verify their solution.

A model for what is learned when acquired a habit

In order to describe what is involved in learning a habit, we use the model of Situated Epistemic Relations (SER; Andersson et al., Citation2018; Andersson & Östman, Citation2015; Shilling, Citation2017). SER takes its departure in the idea that any educational activity is situated in specific circumstances – social, technical, material etc. – and that the educational activities promote certain perceptions and activities and exclude others. By perceptions, we here mean an attention to certain objects and the relations between objects. In an educational event all other possible objects and relations between objects should be ignored. Dewey (Citation1938/1997) calls environment the objects and the relations between the objects that we do things with in order to achieve something. He distinguishes the environment from the totality of objects within reach in the activity, which he calls the surrounding. In terms of SER, the learning of a habit involves developing specific intellectual and bodily capabilities to create an environment and doing things with this environment in order to achieve certain ends. Doing could be any learning activity in a school context. In , below, we describe the two capabilities that are involved in learning a language game, a habit: staging a relevant environment and coordinating the staged environment (see further Andersson et al., Citation2018, Ch. 3). Both of these capabilities involve making judgments. It is the judgments that make the privileging (Wertsch, Citation1998) possible: making specific staging and coordination actions, and not other ones that could be possible. A judgment cannot be made without involving values of some kind. Altogether, it means that knowledge, skills, values and feelings are involved in learning these capabilities (see further Andersson et al., Citation2018).

Table 1. The table provides a summary of the SER-model in terms of the abilities that are involved when learning a habit (an embodied language game).

It might be worth to mention here that the concepts of environment and coordination on the one hand and the concept of situation on the other are interlinked (Cole, Citation1996, pp. 131–132). Dewey (Citation1938/1997) explains:

The conceptions of situation and of interaction are inseparable from each other. An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment, whether the latter consists of persons with whom he is talking about some topic or event, the subject talked about being also part of the situation; or the toys with which he is playing; the book he is reading (in which his environing conditions at the time may be England or ancient Greece or an imaginary region); or the materials of an experiment he is performing. The environment, in other words, is whatever conditions interact with personal needs, desires, purposes, and capacities to create the experience which is had. Even when a person builds a castle in the air he is interacting with the objects which he constructs in fancy. (pp. 43-44)

A transactional model of continuity and change in learning

A central issue in educational methodological discussions is the question of the relation between consecutive learning situations or between past and new experiences – often referred to as the questions of transfer. This means that unit of analysis, in learning studies in addition to the learner and the environment, needs to involve the aspect of time (Jornet et al., Citation2016).

The time aspect is also central in the concise and powerful analysis of education that Dewey makes in Experience & Education (Dewey, Citation1938/1997) and is a crucial aspect of a transactional perspective (Altman & Rogoff, Citation1987). There, Dewey formulates what he calls the principle of continuity, or the experiential continuum: “The principle of continuity means that every experience both takes up something from those which have undergone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after” (Dewey, Citation1938/1997, p. 35). Dewey also maintains that, having undergone an experience, we enter into new experiences as “a somewhat different person.” Experiences affect our habits, not as fixed ways of doing things, but as “basic sensitivities and ways of meeting and responding to all the conditions which we meet in the living” (p. 35). This means that continuity is always accompanied by change and change is always accompanied by continuity (see, also Pepper, Citation1948/1970, pp. 232–233). Let us elaborate a bit further on this transactional perspective on continuity and change.

Rogoff (Citation1995) draws attention to how the sequential conception of time in dualistic approaches makes it difficult to explain how previous experiences participate in meaning making in new situations. Part of the problem of the mysterious bridging of separated time segments is the method of investigations used and the reasons behind them. In order to investigate learning from a dualistic perspective, which treats past experiences as fixed memory packages in the mind, it is argued that we need to know what kind of experiences people have had before they are exposed to a particular situation. We then have to determine the significance of these experiences and relate this to the results of meaning making. In other words, comparable initial and terminal meanings need to be created. Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949/1991) highlight a problem here, namely, that the entire process presupposes that we can find out about an individual’s experience without him or her being exposed to any kind of interaction, i.e. as though the individual was in a frozen state or was a single autonomous atom. So how does the transactional model on continuity and change solve this problem?

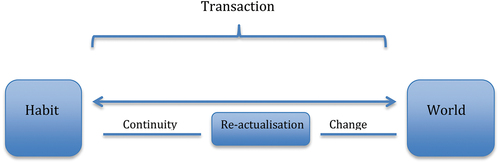

In a transactional model, the relation between consecutive learning situations is investigated in terms of continuity and change, which are understood as two simultaneous and mutual aspects of a learning event (Wickman & Östman, Citation2002a, Citation2002b; Öhman & Östman, Citation2007). In a learning practice, the continuity aspect is understood as the acquired habits that the individual re-actualizes in order to make meanings in a new situation. In a particular educational event, prior experiences can, for example, appear when individuals respond to a situation, assess it, and connect their assessments to future actions. Consequently, when meanings are made, earlier experiences can be seen as being included as part of the event, in action, in the specific situation. Since every situation and every encounter are unique, the recall of the experiences in a situation therefore includes a change: the recall is a re-actualization. Thus, the change aspect is understood in the way the individual relates the recalled experiences to what is encountered in the current educational practice. A central point of the transactional perspective is that not only the individual changes in the process of transition but also the environment: “Every experience influences in some degree the objective conditions under which further experiences are had” (Dewey, Citation1938/1997, p. 37). In the formation of relations in encounters, an individual’s previous experiences take on a different or extended meaning. Individual continuity and change are thus two sides of the same coin, and this mutuality is established when individuals coordinate their actions with the environment (see, ). In other words: in a transactional perspective the time is an internal aspect of learning rather than external as in interactional perspectives where “the analytical focus often traces the person-in-setting at different points in time, whereas the process of transition itself is not problematized” (Jornet et al., Citation2016, p. 297).

Figure 2. Transactional model of continuity and change in learning (TMCC), where in transactions between the individual and the world a re-actualization of earlier acquired habits occur. In the re-actualization the world contribute with change and the habit offers continuity.

The transactional understanding of continuity and change implies that prior experiences do not appear as fixed memory units belonging to the past, but as something that comes into existence when they are re-actualized and related to the circumstances of a present event. Any new situation is more or less different from previous situations and actions and experiences also change the very conditions of subsequent learning situations. Therefore, the individual’s experiences, habits and meanings continuously change as they become part of or make new encounters and create relations in these encounters. However, it is difficult to predict exactly which experiences individuals will recall, how they will relate these experiences to the new learning situation and what meanings they will make. Therefore, in transactional studies, the interplay between continuity and change in individuals’ meaning making is explored in relation to specific events.

A transactional model on the influence of the individual and the environmental on the content learned

Like Lave (Citation1996), we could say that learning is not an issue for learning research: it happens all the time. The mission is rather to understand why certain learning, rather than other learning, takes place in an activity. Therefore, any learning theory needs to take into account both how an individual’s earlier intellectual and bodily experiences (knowledge, skills, values, emotions etc.) and habits influence the learning outcome, and how the environment influences the individual’s learning. With environment we include social interactions, the physical/material surroundings and the cultural/institutional settings.

If we take the starting point in the transactional model of continuity and change described above, it becomes obvious that the influence of the individual and the environmental dimensions of the learning outcome cannot be dealt with in isolation. Rather, these dimensions must be seen as interplaying (bi-directional), and it is the specific interplay that influences what the learning outcome will be. In a transactional perspective, the interplay is seen as reciprocal and simultaneous as well as part of an environing activity (see, Sameroff, Citation2009, Ch. 1; Clancey, Citation2011, p. 254). The reciprocal and simultaneous interplay was above illustrated by Dewey’s example of a trade, but is perhaps even better explained by Cole and Scribner (Citation1978) in their description of Vygotsky’s work in the foreword of Mind in Society:

It is important to keep in mind that Vygotsky was not a stimulus-response learning theorist and did not intend his idea of mediated behavior to be thought of in this context. What he did intend to convey by this notion was that in higher forms of human behavior, the individual actively modifies the stimulus situation as a part of the process of responding to it: it was the entire structure of this activity which produced the behavior that Vygotsky attempted to denote by the term ‘mediating.’ (pp. 13-14)

This reciprocal relation between the individual and the situation is also emphasized by Wertsch (Citation1994), who suggests that sociocultural research should be based on the term mediated action as “humans play an active role in using and transforming cultural tools and their associated meaning systems” (p. 204). Thus, in encounters in an activity the individual and the environment assume meaning simultaneously (in the same event) and the influence on the meaning created is reciprocal. Through the emphasis on contemporaneousness and mutual, reciprocal influence, the perspective of transaction has distinct similarities with Vygotsky’s term mediation, at least if one takes the interpretation of Cole and Scribner and Wertsch seriously.

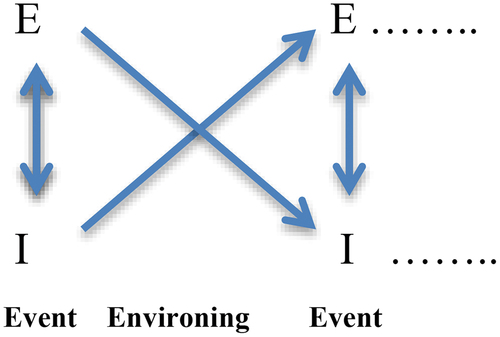

In the transactional model of influence (TM-influence) is described. In the model, the simultaneous and reciprocal influence is marked by the term event, because it is in an event that this type of influence occurs. In the model there is also an environing influence. We have borrowed the term environing from Dewey (Citation1922/1988), who uses it to point to the fact that an environment is made in action. Thus, an event creates an environment that might be attended to in a subsequent event. In the example of a trade, it could be the case that after receiving the goods the buyer asks if there exists any discount if one buys many items instead of one. Thus, the former event becomes the environment for the start of a new event, thereby creating a continuity between the events (see, ).

Figure 3. Illustrating the transactional model of influence (TM-influence), where E stands for environment and I for the individual. The vertical arrows indicate the reciprocal and simultaneous influence that happens in an event, i.e. transaction(s) between the individual and the environment. The diagonal arrows show the environing process that can occur between events, where the first event has changed the conditions – the environment and the individual – for the next event.

The analytical method in the transactional methodology

In the following we first present a crucial methodological challenge and how we have tackled it followed by a description of the analytical method of Practical epistemology analyses (PEA). The whole transactional methodology package of models and method is empirically illustrated in the subsequent section.

A methodological challenge: making the invisible visible through a first person perspective on language

There is one crucial methodological problem that needs to be solved if one wants to develop as transactional methodology, and the problem is connected to the transactional models of continuity and change respectively influence: how is it possible through in situ studies to create knowledge about the individual dimension in the bi-directional interplay. As an important part of the transactional methodology, we here present a first-person perspective on language use, which dissolves the problem of observing the interplay in ongoing practice. This perspective on language forms the basis for the analytical method that is presented in the last part of the article and used in the empirical example.

In relation to research focusing on the individual dimension of influence (cognitive research), this clarification first of all concerns the question of what is observable in action (Stenlund, Citation2000). In cognitive approaches, the mental is perceived as being separated from the outer world and language as something that is possible to separate from humans and their activities. In this perspective, language is regarded as an object – an external instrument – used for connecting meanings (concepts, ideas) with reality (referents, things). In this way, language, the meanings and the environment are described as being located in different realms and having an external relation to each other. Analyses carried out in connection with this view thus tend to treat language as an entity that is detached both from the people who are doing the acting and the environment in which they are acting. We can call this a third-person perspective on language – a perspective taken from a theoretical position that is distanced from the act of communication. This perspective makes it very difficult (and in our view impossible) to analyze the transactional relationship () through studies of action, which is necessary to do in order to get detailed knowledge on the influence of the environmental dimension on the learning outcome.

The solution to the problem, we claim, is to use a first-person perspective on language. Dewey and Wittgenstein both offer a first-person perspective. We do not have the space for elaborating on the differences and similarities between them, but we have elaborated on it in other work (see for example, Andersson et al., Citation2018). Dewey formulates the first-person perspective in the following way:

It will treat the talking and talking-products or effects of man (the namings, thinkings, arguings, reasonings, etc.) as the men themselves in action, not as some third type of entity to be inserted between the men and the things they deal with. (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, p. 11)

As pointed out in this quotation, language is not treated as a mere addition to humans and their environment, but as an aspect of human actions: language and things connected with language (talking, thinking etc.) are synonymous with man in action. What is called “mind” is accordingly something that emerges in the use of language: “Through speech a person dramatically identifies himself with potential acts and deeds // Thus mind emerges” (Dewey, Citation1929/1958/1958, p. 170). The transactional perspective can thus be seen as an alternative to mentalistic investigations in the sense of seeking explanations for people’s actions in the human “mind”:

The living, behaving, knowing organism is present. To add a “mind” to him is to try to double him up. It is double-talk; and double talk doubles no facts. (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, p. 124)

This way of treating language should not be perceived as a theoretical construction, but rather as an observation of how language functions in our daily practices (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, p. 11).

As Cavell (Citation1999) has argued, when we learn a language we do not only learn words. Simultaneously, we also learn about the world, people’s experiences, values etc. That is to say, we learn a social practice.

Accordingly, the connection between language (words, expressions etc.), meaning and environment (objects) is not to be found in theory, but in practice. When we have learned these connections, the meanings of the words used in a certain situation are already obvious. Therefore, in most cases, in our communications with our fellow humans we do not doubt or hesitate about what they know, believe, want etc., since doing this would make many of our ordinary ways of living together impossible. If we do hesitate, we often ask for clarification.

The main methodological point of this first-person perspective is that what is regarded as hidden and unobservable in a third person perspective on language is “visible” (present) in a user perspective. Thus, by using a first-person perspective on language, the inner-outer dualism tends to disappear and the re-actualization of earlier experiences that humans make can therefore be said to be, in most cases, observable in the use of language and body. As a consequence, it appears to be possible to study human beings’ actions and acquire enough information to create knowledge about the individual dimension of learning and, subsequently, about the transactional processes and influences.

Practical epistemology analyses: an analytical method

We make a distinction between analytical models and analytical methods. The function of analytical models, which are built upon theories of learning, is to generate understandings and explanations of learning taking empirical findings as point of departure. The function of analytical methods is to systematically identify essential features and relationships, i.e. empirical findings, which the models can use for generating understandings and explanations.

In the following we will briefly present an analytical method called Practical Epistemology Analysis (PEA; Östman & Wickman, Citation2001; Wickman & Östman, Citation2001, Citation2002a, Citation2002b). PEA takes its departure in the first-person perspective on language presented above and not a learning theory (Östman & Wickman, Citation2001).Footnote2 Although PEA has often been used to analyze learning knowledge as becoming part of a practical epistemology (see for example Almqvist & Östman, Citation2006; Hamza & Wickman, Citation2009, Citation2013; Lidar et al., Citation2006; Öhman & Östman, Citation2007; Rudsberg et al., Citation2013; Wickman, Citation2006), i.e. an epistemology situated within an activity (Östman & Wickman, Citation2014; Rorty, Citation1990), it has also been applied in studies of many other modes of meaning making, such as the practical (Andersson et al., Citation2015; Klaar & Öhman, Citation2012), esthetical (Maivorsdotter & Quennerstedt, Citation2012), artistic (Andersson et al., Citation2018; Larsson & Öhman, Citation2018), ethical (Östman, Citation2010; Sund & Öhman, Citation2014) and political (Van Poeck & Östman, Citation2017).

As argued above, there is an indissoluble relation between an individual’s experience and the environment in which they participate – both the individual’s experience and the environment constitute each other. This constitution happens in the event, but also through the process of environing. But this does not prevent methodological distinctions between different dimensions of the process (see, Garrison, Citation2001; Rogoff, Citation1995). Therefore, our basic empirical questions are formulated as: Which specific kinds of interplay between the individual and the environmental dimensions are created and what are the consequences of these in terms of the content learned?

As PEA is designed to analyze meaning making as individuals’ ways of coordinating with the environment in an activity with a purpose, it is necessary to acquire knowledge about the purposes that the interlocutors themselves pursue.Footnote3 Sometimes the purpose is obvious in the participants’ talk – as ends-in-view (Dewey, Citation1938/1997) – although it can also be important to ask them about the purpose. In PEA, four concepts are central: “encounter,” “gap,” “relation” and “stand fast,” all of which can be operationalized in terms of concrete actions. The term encounter is used to describe what happens when individuals transact in a situation. An encounter can involve, for example, a teacher, peers, oneself and/or the physical world. Gaps occur in these encounters and in order to fill the gap, relations (connectionsFootnote4) have to be created between what the individuals already know and what they encounter. The gaps are often obvious, for example, when the participants hesitate, ask questions, make guesses etc. On other occasions the gaps are immediately filled with relations. Sometimes the participants are unable to fill the gaps, which means that the gap lingers. What stands fast for the different individuals in the situation is what they already know (the previously acquired habits) at that particular moment in time. The stand fast becomes present in that the students use words, gestures, etc., without any hesitations, questions, etc.

An empirical illustration of the methodology

In this section we will empirically illustrate the different knowledge that can be generated by using PEA in combination with the four models, and we have made a short summary in for an overview.

Table 2. Example on what knowledge that can be generated by using the analytical method of PEA together with four different analytical models.

We will illustrate the methodology with a short discussion between two university students. The following transcript, taken from Östman and Wickman (Citation2001), is from a lesson in which the students are investigating the morphology of insects. They have received instructions from the teacher to study the insects’ antennae, mouthparts, etc. We enter the conversation when the students have observed a bumblebee in the stereomicroscope. The antennae of the bumblebee are gone (which happens to pinned insects), and they are consulting the textbook.

In we have listed the gap and the relations that are created in the specific encounter. The role of PEA is thus to generate empirical findings regarding lingering gaps, encounters that are staged, what stands fast, which relations they create, etc.

Table 3. Gaps, relations and encounters when students investigate bumblebees.

Lets start the empirical illustration by combining the result of PEA with the trajectory model of learning (LT-model). In the conversation the students express a gap: do all bumblebees have antennae? Before this expression they have encountered the bumblebee, which misses the antennae, through the microscope. Thus, they have experienced a disturbance that generates an intellectual problematic situation. They do not manage to bridge the gap immediately – the gap lingers – and therefore they start an inquiry. Malin starts this inquiry by re-actualizing her experience of animated films in relation to the bumblebee (relation A) in order to bridge the gap, and Lena agrees with her conclusion. In the next meaning exchange, Malin re-actualizes another experience for believing that bumblebees have antennae: an artist who always makes representational pictures has painted bumblebees with antennae (relation B). Through construing this relation, they have solved the problematic situation that was the start of the inquiry.

We continue the illustration with combining the findings from PEA with the transactional model of influence (TM-influence). What is obvious from the PEA is that, for the students, a lot of words and expressions stand fast, for example, bumblebee, antennae, cartoon films and paintings. In the conversation they create relations to whatever stands fast for them in order to bridge the lingering gap. They create these relations in and through transactions with the world and with their own experiences. Through the transactional event a relation is created, for example, between a real bumblebee without antennae (the environmental dimension in terms of the physical world) and specific prior experiences (the individual dimension): animated films where the bumblebees have antennae. It is of course not only the real bumblebee (the physical world) that makes up the environment in this case, but also the instruction of the teacher (the institutional dimensions) and the peer (the interpersonal dimension). The attention to the antennae is there because of the encounter with teacher and his/her instructions, and the transactional event occurs in the communication with the peer. Thus, it is the activity-specific interplay between the individual and the environmental dimension (the physical, the interpersonal and the institutional) that becomes visible in the encounters staged and the relations construed. The relations that are construed by the students can be used to create detailed knowledge on how the interplay includes a reciprocal and simultaneous influence. For example, students previous experience of bumblebees (for example, that bumblebees in cartoon films and in realistic paintings have antennae) acquire new meaning in the encounter with the real bumblebee in the specific activity – as “proofs” that bumblebees in general have antennae. At the same time, the real bumblebee gets a specific meaning in relation to previous experiences: as having no antennae.

The result of PEA, in terms of relations, in combination with the transactional model of continuity and change in learning (TMCC) can generate an understanding of the continuity and change occuring in the learning process. For example, when recalling “antennae” for the first time, they do so in relation to a real bumblebee resulting in a gap. The antennae get its meaning in relation to a real bumblebee and it is obvious that they have never done that connection before, since it creates a gap. Thus, the recall of antennae is a re-actualization: it becomes present in a unique relation. When analyzing continuity and change in learning, it is important to also recognize the environing function in meaning making, i.e. that the re-actualization (the individual dimension) that become part of a relation with the environment created in one encounter can become an environment in subsequent encounters. For example, when Lena re-actualizes bumblebee in the formulation of the questions it becomes an important part of the environment in subsequent encounters between them.

We will end the empirical illustration by using the result of PEA in combination with the model of situated epistemic relation (SER). In terms of SER – the content of learning that can become a consequence of the trajectory of learning – we can say that the students managed to stage a relevant environment – a real bumblebee and a realistically painted bumblebee. The fictional bumblebee is not a relevant bumblebee in this activity. The students also manage to coordinate with this environment in a relevant way in order to arrive at a solution, namely making an epistemologically-based generalization about whether all bumblebees have antennae or not.Footnote5 Thereby, they bridge the gap that initiated the inquiry. Thus, what the students managed to do in the inquiry is to develop relevant SER.

Conclusion

In this article we have presented and empirically illustrated a pragmatic methodology in which the transactional approach is pivotal. The methodology draws on the work that many researchers have been engaged in for the last two decades and we hope it will inspire others. It is essential to point out that our ambition here is not to present a new universal theory or an ontology, but in line with Dewey and Bentley (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1991, p. 152), to present a methodology for in situ investigations where the above mentioned ambitions are in focus.

It is also essential to point toward the fact that many of the learning phenomena that the models tries to capture are already handled by different sociocultural approaches in interesting ways. For example the work on mediation by Cole (Citation1996) and Wertsch (Citation1994) has been of great value for our work. The methodology does, of course, connect to and make use of research that have been using a transactional perspective, for example, Clancey (Citation2011), Garrison (Citation2001), Jornet et al. (Citation2016), Rogoff (Citation1995), and Shilling (Citation2017). In our view it is the package of analytical models and analytical method as a whole that contributes to the development of learning research and especially how this package can generate knowledge that scholars within sociocultural approaches – for example, Lehman et al. (Citation2004) – has been asking for. An important problem that the package tries to solve is how to create knowledge about the individual dimension of learning through in situ studies. We use two strategies in order solve this problem. The first strategy is to construe an analytical method (PEA) built upon a first person perspective on language, making what is often believed to be invisible in action – the individual dimension – to become present in transactions. By making the individual dimension present in transactions it becomes possible to create knowledge, through in situ studies and with the help of PEA, of how an activity specific interplay – a specific reciprocal relation – between the individual (intrapersonal) and the environmental (physical, interpersonal and institutional) dimension affect the learning outcome. This achievement also opens up opportunities to create knowledge on the continuity and change occurring in and between transactional events during the trajectory of learning

The second strategy is to build distinct models that can be helpful in the analytical work and that will not fall into the dualistic trap between inner and outer. We hope that by making habit central in the trajectory model of learning (LT-model) and in SER, the model to be used in analyses of the learning outcome, we have succeeded to avoid that trap (compare Cantril et al., Citation1949, p. 517).

We want to end by pointing to a general strength of the philosophical work on transaction by Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949/1991), namely that they succeeded in converting “ontological dualisms into phases of problem-solving activity” (Ryan, Citation2016, p. 290) and by doing so, their, and others, philosophical work on transaction has for us been an important inspiration source when trying to contribute to the development of the sociocultural research on learning.

Acknowledgments

The authors owe thanks to the reviewers as well as to the members of the research groups SMED (Studies of Meaning-making in Educational Discourses) for their valuable feedback and inspiring comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. This notion of continuous back-and-forth process is one of the basic ideas that Dewey uses when formulating his philosophy of esthetics and art (see further Andersson et al., Citation2018).

2. When the method was created it was mainly inspired by the work of Wittgenstein and especially his way of using a first-person perspective on language. See, Andersson et al. (Citation2018) for a comparison between Dewey and Wittgenstein regarding their approach to language.

3. It is important to notice that this methodological advice does not imply a psychological interpretation of intention. Instead we use the transactional approach illustrated by Wittgenstein as the following: “An intention is embedded in its situation, in human customs and institutions. If the technique of the game of chess did not exist, I could not intend to play a game of chess. In so far as I do intend the construction of a sentence in advance, that is made possible by the fact that I can speak the language in question” (Wittgenstein, Citation1953/1997, § 337).

4. Chris Shilling (Citation2017) is, in the context of studies in body pedagogy, suggesting that the term relation might be changed to connection in order to not risk the interpretation that ”there exists a correspondence between the institutional level” which the analyses of SER is devoted to ”and the embodied experiences associated with body pedagogics” (p. 13, Note 1).

5. It is worth noting that biology as a discipline has long been dependent on artists skilled in making ”representational” drawings in order to make generalizations about the characteristics of species.

References

- Almqvist, J., & Östman, L. (2006). Privileging and artefacts. On the use of information technology in science education. Interchange, 37 (3) , 225–250 DOI:10.1007/s10780-006-9002-z.

- Altman, B., & Rogoff, B. (1987). World views in psychology: Trait, interactional, organismic and transactional perspectives. In D. Stokols & I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp. 7–40). John Wileys & Sons.

- Andersson, J., Garrison, J., & Östman, L. (2018). Empirical philosophical investigations in education and embodied experiences. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Andersson, J., & Östman, L. (2015). A transactional way of analysing the learning of ‘tacit knowledge.’ Interchange, 46(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-015-9252-8

- Andersson, J., Östman, L., & Öhman, M. (2015). I am sailing – Towards a transactional analysis of ‘body techniques.’ Sport, Education and Society, 20(6), 722–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.802684

- Cantril, H., Ames, A., Hastorf, A. H., & Ittelson, W. H. (1949). Psychology and scientific research. III. The transactional view in psychological research. Science, New Series, 110, 517–522 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.110.2862.461.

- Cavell, S. (1999). The claim of reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality and Tragedy. Oxford University Press.

- Clancey, W. J. (2011). A transactional perspective on the practice-based science of teaching and learning. In T. Koschmann (Ed.), Theories of learning and studies of instructional practice. Explorations in the learning sciences, instructional systems and performance technologies (Vol. 1, pp. 247–278). Springer.

- Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology. A once and future discipline. Harvard University Press.

- Cole, M., & Scribner, S. (1978). Introduction. In M. Cole & S. Scribner (Eds.), L.S. Vygotsky. Mind in society. The develop- ment of higher psychological processes (pp. 1–14). Harvard University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1909/1983). The influence of Darwinism on philosophy. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The Middle Works, 1899–1924 (Vol. 4, pp. 1907–1909). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1922/1988). Human nature and conduct. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works, 1899-1924 (Vol. 14, pp. 1922). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1922/2002). Human nature and conduct: an introduction to social psychology. Prometheus Books.

- Dewey, J. (1929/1958). Experience and nature. Dover Publications.

- Dewey, J. (1932/1985). Ethics. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The Later Works, 1925–1953 (Vol. 7, pp. 1932). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938/1986). Logic: The theory of inquiry. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The Later works, 1925–1953 (Vol. 12, pp. 1938). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938/1997). Experience and education. Touchstone.

- Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. F. (1949/1991). Knowing and the known. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The Later Works, 1925-1953 (Vol. 16, pp. 1949–1952). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Garrison, J. (1995). Deweyan pragmatism and the epistemology of contemporary social constructivism. American Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 716–740. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032004716

- Garrison, J. (2001). An introduction to Dewey’s theory of functional ’trans-action’: An alternative paradigm for Activity theory. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 8(4), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0804_02

- Hamza, K. M., & Wickman, P.-O. (2009). Beyond explanations: What else do students need to understand science? Science Education, 93(6), 1026–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20343

- Hamza, K. M., & Wickman, P.-O. (2013). Supporting students’ progression in science: Continuity between the particular, the contingent, and the general. Science Education, 97(1), 113–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21042

- Hodkinson, P., Biesta, G., & James, D. (2007). Understanding learning cultures. Educational Review, 59(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910701619316

- James, W. (1912/1976). Essays in radical empiricism. Harvard University Press.

- Johnson, M. (2007). The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. The University of Chicago Press.

- Jornet, A., Roth, W.-M., & Krange, I. (2016). A transactional approach to transfer episodes. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(2), 285–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1147449

- Klaar, S., & Öhman, J. (2012). Action with friction: A transactional approach to toddlers’ physical meaning making of natural phenomena and processes in preschool. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(3), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.704765

- Larsson, C., & Öhman, J. (2018). Music improvisation as an aesthetic event: Towards a transactional approach to meaning-making. European Journal of Philosophy in Arts Education, 3(1), 121–181.

- Lave, J. (1996). The practice of learning. In S. Chaiklin & J. Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice. Perspectives on activity and context (pp. 3–32). Cambridge University Press.

- Lehman, D. R., Chiu, C.-Y., & Schaller, M. (2004). Psychology and culture. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 689–714. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141927

- Lidar, M., Lundquist, E., & Östman, L. (2006). Teaching and learning in the science classroom. Science Education, 90(1), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20092

- Maivorsdotter, N., & Quennerstedt, M. (2012). The act of running: A practical epistemology analysis of aesthetic experience in sport. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 4(3), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.693528

- Öhman, J., & Östman, L. (2007). Continuity and change in moral-meaning making: A transactional approach. Journal of Moral Education, 36(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701325258

- Östman, L. (2010). ESD and discursivity: Transactional analyses of moral meaning making and companion meanings. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504057

- Östman, L., Van Poeck, K., & Öhman, J. (2019). A transactional theory on sustainability learning. In K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, & J. Öhman (Eds.), Sustainable development teaching. Ethical and political challenges (pp. 127–139). Routledge.

- Östman, L., & Wickman, P.-O. (2001). Practical epistemology, learning and socialization. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, April 2001.

- Östman, L., & Wickman, P.-O. (2014). A pragmatic approach on epistemology, teaching and learning. Science Education, 98(3), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21105

- Pepper, S. C. (1948/1970). World hypotheses: A study in evidence (2nd edn ed.). University of California Press.

- Rogoff, B. (1995). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In J. V. Wertsch, P. Del Rio, & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural studies of mind (pp. 139–164). Cambridge University Press.

- Rorty, R. (1990). Pragmatism as anti-representationalism. In J. P. Murphy (Ed.), Pragmatism. From Peirce to Davidson (pp. 1–6). Westview Press.

- Roth, W.-M., & Jornet, A. (2013). Situated cognition. WIREs Cognitive Science, 4(5), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1242

- Roth, W.-M., & Jornet, A. (2014). Towards a theory of experience. Science Education, 98(1), 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21085

- Rudsberg, K., Öhman, J., & Östman, L. (2013). Analysing students’ learning in classroom discussions about socio-scientific issues. Science Education, 97(4), 594–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21065

- Ryan, F. X. (2016). Rethinking the human condition: Skepticism, realism, and transactional pragmatism. Contemporary Pragmatism, 13(3), 263–297. https://doi.org/10.1163/18758185-01303003

- Sameroff, A. (Ed.). (2009). The transactional model of development: How children and context shape each other. American Psychological Association.

- Semetsky, I. (2008). On the creative logic of education, or: re-reading Dewey through the lens of complexity science. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 83–95.

- Shilling, C. (2017). Embodying culture: Body pedagogics, situated encounters and empirical research. The Sociological Review, 66(1), 75–90 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026117716630

- Stenlund, S. (2000). Filosofiska uppsatser (Philosophical Essays). Norma.

- Sund, L., & Öhman, J. (2014). Swedish teachers’ ethical reflections on a study visit to Central America. Journal of Moral Education, 43(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2014.920309

- Van Poeck, K., & Östman, L. (2017). Creating space for‘the political’ in environmental and sustainability education practice: A political move analysis of educators actions. Environmental Education Research, 24 (9), 1406–1423 . https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1306835

- Wertsch, J. V. (1994). The primacy of mediated action in sociocultural studies. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1(4), 202–208 http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hmca20.

- Wertsch, J. V. (1998). Mind as action. Oxford University Press.

- Wickman, P.-O. (2006). Aesthetic experience in science education: Learning and meaning-making as situated talk and action. Erlbaum.

- Wickman, P.-O., & Östman, L. (2001). University students during practical work: Can we make the learning process intelligible? In H. Behrendt, H. Dahncke, R. Duit, W. Graber, M. Komorek, A. Kross, & P. Reiska (Eds.), Research in science education: Past, present, and future (pp. 319–324). Kluwer.

- Wickman, P.-O., & Östman, L. (2002a). Induction as an empirical problem: How students generalize during practical work. International Journal of Science Education, 24(5), 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690110074756

- Wickman, P.-O., & Östman, L. (2002b). Learning as discourse change: A sociocultural mechanism. Science Education, 86(5), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10036

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953/1997). Philosophical investigations. Blackwell.

- Wolcott, H. F. (1994). Transforming qualitative data: description, analysis, and interpretation. Sage Publications.