ABSTRACT

Background: The relationship between stroke survivors and family caregivers is critical for the well-being of both dyad members. Currently, there are few interventions targeted at dyads and focused on strengthening the relationship between survivors and family caregivers.

Objectives: This study reports on the development of a customizable, strengths-based, relationship-focused intervention driven by the real-world experience and advice of stroke dyads. It also describes the “tips” that survivors and family caregivers offered for dealing with relationship challenges after stroke.

Methods: Content of the intervention, including relationship tips, was derived from semi-structured interviews with N= 19 stroke dyads. A modified Delphi process with a national panel of 10 subject matter experts was used to evaluate and refine the content of the intervention and the associated screening tool.

Results: Seventeen domains of relationship challenges and tips were identified. Consensus was reached among experts that the intervention content was relevant to the goal of helping survivors and family caregivers maintain a strong relationship after stroke; (2) clear from the perspective of stroke survivors and family caregivers who would be using it; (3) accurate with respect to the advice being offered, and; (4) useful for helping stroke survivors and family caregivers improve the quality of their relationship.

Conclusions: This study extends the limited body of research about dyadic interventions after stroke. The next steps in this line of research include feasibility testing the intervention and evaluating its efficacy in a larger trial.

Introduction

Following discharge from initial hospitalization, approximately 80% of stroke survivors return home where they depend upon family members for critical support.Citation1 Although the experience of being a family caregiver is nuanced and complex, caregivers consistently report higher levels of stress than non-caregivers.Citation2 Moreover, as many as 52% of caregivers exhibit symptoms of depression that typically do not improve over the course of recovery without intervention.Citation3–Citation5 Because caregiver and survivor emotional health are intertwined,Citation6–Citation8 systematic reviews similarly conclude that approximately 31% of stroke survivors also experience depression.Citation9,Citation10

In addition to impacting the health of individuals, stroke and stroke caregiving can be challenging for relationships. Approximately 54% of families dealing with stroke experience relationship problems and as many as 38% of couples experience overt conflictCitation11 that may stem from feelings of isolation, lack of reciprocity of emotional support and tasks, decreased harmony, and communication difficulties.Citation12–Citation19 For spousal caregivers, decreased sexual intimacy also is frequently reported as a concern.Citation20,Citation21 For those who manage to maintain a strong relationship, the rewards of caregiving may be a protective factor against depression and other poor outcomes.Citation22 This reinforces the importance of facilitating and strengthening positive interactions and relations for those who may need it.

A number of interventions for stress, depression, and other negative psychosocial outcomes after stroke currently exist, most of which focus on individual survivors or caregivers. When stroke survivors exhibit depression, antidepressant medications are the primary treatment.Citation23 However, treatment for stroke caregivers has been more varied. In addition to antidepressant medication, a variety of interventions have been employed, including cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy,Citation24 skill mastery,Citation25 stress management,Citation26 provision of information,Citation27 bolstering of social support,Citation28 managing emotions and communication,Citation29 coping and problem-solving,Citation30 or different combinations of these strategies. What unifies and to some extent limits the effectiveness of these interventions, is their focus on individual survivors or family caregivers, with little attention being given to the care dyad and the relationship between care partners that may be foundational for positive outcomes.Citation7,Citation31

A growing body of literature supports the value of a dyadic approach to theory, practice, and research with chronic illness populations.Citation32–Citation34 However, there are at present very few interventions that adopt such an approach. Cheng et al.Citation35 and Bakas et al.Citation36,Citation37 conducted systematic reviews of caregiver and dyad psychosocial interventions after stroke. Dyad interventions were largely consistent with those used for survivors or caregivers alone and included various combinations of skill mastery, problem-solving, social and community support, and health maintenance or improvement for individual survivors or caregivers. Only a small number of interventions explicitly aimed to improve relational outcomes and even fewer demonstrated positive effects for both members of the dyad.Citation38–Citation40

More recently, Terrill et al.Citation41 implemented a pilot study with 11 stroke survivor-spousal caregiver dyads. In addition to individual outcomes including resilience, quality of life, and depression, the authors sought to improve relational outcomes such as positivity and negativity between dyad members. Although participant outcomes were not reported, findings demonstrated the feasibility of this dyadic, self-administered, positive psychology-based intervention and suggested that this may be a novel and promising approach. Ten of the 11 dyads who were originally enrolled completed the study, participated in at least six of the prescribed eight sessions, and perceived benefit from the intervention.Citation41

The purpose of this intervention development and validation study is to extend the limited body of research about dyadic interventions in stroke and provide insight into the lived-experiences, advice, and perceived relationship strengths of stroke survivors and family caregivers. Specifically, we describe the process that was used to validate the content of a dyadic post-stroke intervention entitled, Hand in Hand: A Partners’ Guide to Managing Stroke Together, including the 17-item Relationship Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) used to tailor the intervention materials to the needs of each dyad. We also provide examples of the strategies and advice (“tips”) dyads offered for maintaining a strong relationship after stroke that serve as the foundation for the Hand in Hand program.

Methods

Development of the hand in hand program and RAQ

The methods used for the qualitative portion of this study conform with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines.Citation42 Content of the draft Hand in Hand program and RAQ was driven by data collected during semi-structured interviews, conducted in participants’ homes by two members of the research team (study coordinator and PI), with 19 stroke dyads (11 spousal, 8 adult child-parent) recruited through the [blinded for review] Comprehensive Stroke Center. Both interviewers were middle-aged white males with a Master’s degree and PhD, respectively. Both interviewers had training and experience with research interviewing. Study participants did not know the interviewers prior to meeting them.

The interview guide and subsequent intervention materials were informed by two complementary theories about how family dyads cope with chronic illness: the Systemic Transactional Model of Stress and CopingCitation43 and the Developmental Contextual Model of Coping.Citation33 The final data consisted of approximately 25 h of audio recordings, 528 pages of transcribed interviews, and 34 summary case reports which were used to contextualize the interviews.

To be included in the study, participants had to be at least 21 years old, within 12 months of stroke, living together in the community or spending a “significant amount of time together in care-related activities” (reported by participants), without significant cognitive impairment, and capable of providing informed consent and participating in study activities. Dyads were excluded if the survivor had severe aphasia to the degree that s/he could not participate even with communication aides or, if either person had a history of severe mental illness such as suicidal tendencies, severe untreated depression, or manic depressive disorder. Data saturation was reached after 19 dyads. Approximately 68% of survivor participants were female and 68% were white, with an average age of approximately 67 years (range = 43–88 years). Approximately 53% of family caregiver participants were female and 68% were white, with an average age of approximately 56 years (range = 22–85 years).

Three members of the research team (study coordinator, PI, research assistant) analyzed the data and an outside observer provided feedback about the process on an ongoing basis. Using an interpretive description approach which includes data immersion, inductive interpretation, and an emphasis on the utility of findings for practice,Citation44 17 common relationship challenges were derived from the qualitative interviews. The draft RAQ consisted of 17 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale which ranged from Extremely Difficult (−3) to Extremely Easy (+3). For example, “In our relationship since the stroke. managing stroke-related communication issues has been … ”; “ … agreeing about how much we can each do has been … ”; “ … adjusting to the roles of ‘survivor’ and ‘caregiver’ has been … ”; etc.

Each Tip Sheet that, together, constitute the Hand in Hand program corresponded to one of the 17 relationship challenges listed in the RAQ. The Tip Sheets included information, resources, and short exercises designed to help “care partners” maintain a strong relationship after stroke. All Tip Sheets were written at the 8th grade level (determined by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level in Microsoft Word) and included illustrative quotes from stroke dyads that were gathered during the qualitative interviews. Tip Sheets 1 through 4 focused on issues that arise when one or both partners experience communication (i.e., aphasia), physical/mobility, cognitive, or emotional issues. Tip Sheets 5 through 7 focused on helping partners reach agreement about different aspects of recovery. Tip Sheets 8 through 10 dealt with helping partners work together to meet their practical and emotional needs, including the need for personal space. Tip Sheets 11 through 14 focused on adjusting to new roles and realities after stroke. Tip Sheet 15 offered advice for helping dyads deal with relationship problems that existed before stroke. Tip Sheets 16 and 17 described strategies dyads could use to get needed support from other family members, friends, peers, and professionals.

Expert panel participants and Delphi process

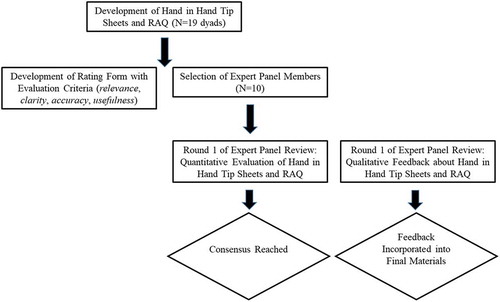

Based upon the modified Delphi processes described by Bakas et al.Citation45 and Fisher et al.,Citation46 the draft Tip Sheets and RAQ were circulated to a national panel of 10 subject matter experts: Three health-care providers, identified as experts by having at least 5 years of clinical experience with post-stroke dyads; Three researchers, identified as experts by having a doctoral degree and a strong record of publication in this area; and four “laypersons” (i.e., two-stroke survivor-family caregiver dyads). Experts completed a short demographic questionnaire that included items about their gender, age, professional discipline, academic degrees, years in the stroke recovery field (i.e., for providers and researchers), and years living with stroke (i.e., for survivors and caregivers). With a rating form developed for this study, experts then rated the extent to which the RAQ (analyzed by experts as a total questionnaire, not at the item level) and each Tip Sheet was (1) relevant to the goal of helping survivors and family caregivers maintain a strong relationship after stroke; (2) clear from the perspective of stroke survivors and family caregivers who would be using it; (3) accurate with respect to the advice being offered, and; (4) useful for helping stroke survivors and family caregivers improve the quality of their relationship. Ratings were on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree – not relevant/clear/ accurate/useful at all) to 5 (strongly agree – extremely relevant/clear/ accurate/useful). Frequencies and modal responses were calculated using SPSS v25.Citation47 depicts this process.

Experts also provided written qualitative feedback about the RAQ and Tip Sheets including which Tip Sheets they felt were the most/least helpful and why, other relationship problems that should be addressed in the program, general suggestions for making the program better, whether or not they felt the overall program would be helpful to survivors and family caregivers, and whether they would recommend the program to others. These data were organized into a single document which was then used to make suggested revisions to the program. Experts were given a $50 gift card in appreciation for their time. A professional graphic designer was used to ensure that the final materials were visually attractive. All activities were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board which consists of 19 members.

Results

presents the demographics of the expert panel which consisted of an Occupational Therapist, Nurse, and Psychologist (stroke health-care providers); a Neurologist, Nurse, and Psychologist (stroke researchers); and two-stroke survivor-family caregiver dyads (“laypersons”). Health-care providers and researchers were female and ranged in age from 36 to 68 years old. Cumulatively, these professionals had approximately 109 years of experience in the field of stroke recovery. Laypersons ranged in age from 47 to 51 and were between two and 3 years into the recovery process.

Table 1. Expert panel member demographics.

Results of the modified Delphi process are presented in . Per Fisher et al.,Citation46 expert panel agreement that the RAQ and Tip Sheets were accurate, clear, relevant, and useful was determined by at least 75% of panelists indicating “agree” or “strongly agree” for each criteria. By this standard, we achieved consensus on the RAQ and Tip Sheets in the first round of review. However, none of the intervention components produced 100% agreement among experts across all four criteria. Tip Sheets #3, #4, #5, #7, #8, #9, #13, and #14 produced the highest and most consistent ratings among experts, whereas the RAQ and Tip Sheets #1 and #15 produced the lowest and least consistent ratings.

Table 2. Expert panel ratings of intervention materials.

For all intervention components, experts provided editorial suggestions and detailed feedback about strengths of the program as well as ways to make the program better. Comments about the program’s strengths included: “I really loved Tip Sheet #5, very good.”; and, “I think [Tip Sheet] #14 is very useful because there is probably nowhere else that survivors and caregivers will encounter this.” Suggestions for improvements to the program included adding references and suggested readings to the end of each Tip Sheet, adding more “helpful worksheets – like homework or practice exercises” and using “different colors, fonts, pictures, [and] boxes, to draw the eye.” Whenever possible, we incorporated these suggestions into the final materials.

presents the broad topics of the 17 Hand in Hand Tip Sheets along with sample quotes from survivors and caregivers who participated in the semi-structured interviews. The Tip Sheets were drafted in 14-point font and varied in length from four to 10 pages. Most contained images, supplemental resources, selected references and further readings, and checklists or worksheets.

Table 3. Tip sheet topics and sample quotes from the Hand in Hand program.

Discussion

The intervention described in this study builds upon existing theoryCitation32–Citation34 and researchCitation38–Citation41 aimed at improving outcomes in both members of the care dyad. This study also provides insight into the lived experiences of stroke dyads themselves. Healthcare and other providers may find this information to be valuable as they interact with survivors and family caregivers.

Content validity of the Hand in Hand program

Based upon Fisher et al.,Citation46 we anticipated that the draft program would need to be circulated multiple times among experts before consensus could be reached. We were happily surprised to reach consensus after only one round (i.e., with at least 75% of experts indicating “agree” or “strongly agree” for each criteria). Reviewers also provided rich qualitative feedback and suggestions about how to make the program better and potentially more effective for stroke dyads. This feedback, from different disciplinary orientations (e.g., occupational therapy, nursing, psychology, medicine) and from laypersons with lived experience coping with stroke, was invaluable to the process.

Although the majority of experts agreed or strongly agreed that each component was accurate, clear, relevant, and useful on the first round of review, ratings were not uniformly positive. Where we had lower ratings from individual reviewers, we gave special consideration to that reviewer’s suggestions for improvement. For example, one expert gave a low rating to the clarity of Tip Sheet #4 and commented that the “terms/labels were not consistent”. Another reviewer gave a low rating to the relevance of Tip Sheet #11 because it was “fairly generic and needed a bit more meat to it.” This feedback was discussed among the research team and led to improvements in those Tip Sheets.

Based upon the work of Bakas et al.,Citation48 we also anticipated having to eliminate one or more Tip Sheets altogether because of redundancy in content. Reviewers did note some overlap between certain Tip Sheets (e.g., #2 and #5). However, after careful consideration and further review of our data (e.g., one expert stated, “some overlap/redundancy can be helpful”), we decided that some degree of overlap was acceptable at this stage of development. Reviewers also had suggestions for additional content (e.g., more information related to dealing with stroke when one has young children). This feedback was used to enhance the existing materials but unlike Bakas et al.,Citation47 we did not choose to develop additional Tip Sheets to accommodate these suggestions.

Strategies and advice offered by stroke dyads

Similar to other interventions that are driven by first-hand information from the populations for which they have been developed,Citation25 we found that stroke survivors and family caregivers had extremely rich and relevant tips for dealing with the relational aspects of recovery. presented a brief sample of participant quotes. The Hand in Hand program itself contains many more. We are finding that for survivors and family caregivers, these quotes help to reinforce the family-driven, strengths-based process that was used to develop the program. Our hope is that this will lead to better outcomes.

Study limitations

As with any research, the present study had limitations. First, although the principal investigator is male, the health-care providers and researchers who rated the materials and provided feedback were all female. It would have been valuable to include male providers and researchers on the expert panel, as studies suggest that provider gender can influence provider-patient interactions, patient satisfaction, and other outcomes.Citation49–Citation51 Accordingly, it may be that provider gender also influences perceptions of the relationship between patients and family caregivers. Second, the stroke survivors and family caregivers who rated the materials and provided feedback were all between 2 and 3 years into recovery and all very close in age. Research has shown that the first few months after stroke can be a tumultuous time for survivors and family caregivers as dyad members work to adjust to post-stroke life, establish new routines, and learn new ways to communicate with one another.Citation52 Thus, it may have been valuable to include stroke dyads who were closer to the illness event, as opposed to having wrestled through the relationship problems and tips presented in the Hand in Hand program months or even years before. Including dyad experts at different stages of life may also have yielded more information.

Conclusions

Examining content validity is a critical step in the development of psychosocial interventions in stroke.Citation45 This article described the process that was used to validate the content of the Hand in Hand program, a customizable intervention based upon the lived experiences of stroke survivors and their family caregivers and designed to strengthen the quality of relationship between dyad members. We also provided examples of the tips dyads offered for maintaining a strong relationship after stroke that drive the Hand in Hand program.

Presently, we are conducting a pilot RCT to test the feasibility of the Hand in Hand program. Recruitment has been steady and anecdotal data suggest that the Hand in Hand program is being well-received. We anticipate completing the feasibility study soon and depending upon the results of that study, testing the efficacy of the Hand in Hand program in a larger trial. Ultimately, we hope to make the program broadly available to survivors and family caregivers whose relationship may benefit from additional support. This would meet a great need in this community, considering the prevalence of relationship problems after stroke,Citation1,Citation11,Citation52,Citation53 the importance of a strong relationship between dyad members for prevention of depression and other poor outcomes,Citation7,Citation31 and the current lack of post-stroke interventions targeted at both members of the care dyad.Citation35–Citation37

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to [other study staff - blinded for review] for their assistance with this study and to [expert panel members - blinded for review] for the valuable feedback they provided. We also thank the stroke survivors and family caregivers who generously provided data upon which the Hand in Hand program is based.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Quinn K, Murray C, Malone C. Spousal experiences of coping with and adapting to caregiving for a partner who has a stroke: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disability Rehabil. 2014;36(3):185–198. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.783630.

- Roth DL, Brown SL, Rhodes JD, Haley WE. Reduced mortality rates among caregivers: does family caregiving provide a stress-buffering effect? Psychol Aging. 2018;33(4):619–629. doi:10.1037/pag0000224.

- Gaugler JE. The longitudinal ramifications of stroke caregiving: A systematic review. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55(2):108–125. doi:10.1037/a0019023.

- Haley W, Roth D, Hovater M, Clay O. Long-term impact of stroke on family caregiver well-being: A population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2015;84:1323–1329. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001418.

- Han B, Haley WE. Family caregiving for patients with stroke: review and analysis. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1478–1485. doi:10.1161/01.STR.30.7.1478.

- McCarthy MJ, Lyons KS, Powers LE. Expanding poststroke depression research: movement toward a dyadic perspective. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(5):450–460. doi:10.1310/tsr1805-450.

- McCarthy MJ, Powers LE, Lyons KS. Relational factors associated with depressive symptoms among stroke survivor-spouse dyads. JFamSocWork. 2012;15(4):303–320. doi:10.1080/10522158.2012.696230.

- Ostwald SK, Godwin KM, Cron SG. Predictors of life satisfaction in stroke survivors and spousal caregivers after inpatient rehabilitation. Rehabil Nurs. 2009;34(4):160–167, 174; discussion 174. doi:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2009.tb00272.x.

- Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(8):1017–1025. doi:10.1111/ijs.12357.

- Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS. Frequency of depression after stroke: A systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005;36(6):1330–1340. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000165928.19135.35.

- Daniel K, Wolfe C, Busche M, McKevitt C. What are the social consequences of stroke for working-aged adults? A systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(6):431–440. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.108.534487.

- Bäckström B, Asplund K, Sundin K. The meaning of middle-aged female spouses’ lived experience of the relationship with a partner who has suffered a stroke, during the first year postdischarge. Nurs Inq. 2010;17(3):257–268. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00490.x.

- Banks P, Pearson C. Parallel lives: younger stroke survivors and their partners coping with crisis. Sexual Relat Ther. 2004;19(4):413–429. doi:10.1080/14681990412331298009.

- Brann M, Himes KL, Dillow MR, Weber K. Dialectical tensions in stroke survivor relationships. Health Commun. 2010;25(4):323–332. doi:10.1080/10410231003773342.

- Coombs UE. Spousal caregiving for stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39(2):112–119. doi:10.1097/01376517-200704000-00008.

- DeLaune M, Brown SC Spousal responses to role changes following a stroke. MedSurg Nursing. April 2001. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A73063749/AONE?sid=googlescholar. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- Godwin KM, Ostwald SK, Cron SG, Wasserman J. Long-term health-related quality of life of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. J Neurosci Nurs. 2013;45(3):147–154. doi:10.1097/JNN.0b013e31828a410b.

- Godwin K, Swank P, Vaeth P, Ostwald S. The longitudinal and dyadic effects of mutuality on perceived stress for stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(4):423–431. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.756457.

- Visser-Meily A, Post M, Port IV, Maas C, Forstberg-Warleby G, Lindeman E. Psychosocial functioning of spouses of patients with stroke from initial inpatient rehabilitation to 3 years poststroke: course and relations with coping strategies. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1399–1404. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.108.516682.

- Giaquinto S, Buzzelli S, Di Francesco L, Nolfe G. Evaluation of sexual changes after stroke. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):302–307. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0312.

- Green TL, King KM. Experiences of male patients and wife-caregivers in the first year post-discharge following minor stroke: A descriptive qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(9):1194–1200. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.008.

- Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: a systematic review. Disability Rehabil. 2012;34(17):1413–1422. doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.650307.

- Ladwig S, Zhou Z, Xu Y, et al. Comparison of treatment rates of depression after stroke versus myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational data. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(8):754–763.doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000632.

- Hartke RJ, King RB. Telephone group intervention for older stroke caregivers. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;9(4):65–81. doi:10.1310/RX0A-6E2Y-BU8J-W0VL.

- Bakas T, Weaver MT, Austin JK, et al. Telephone Assessment and Skill-building Kit for stroke caregivers: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Stroke. 2015;46(12):3478–3487.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011099.

- King RB, Hartke RJ, Denby F. Problem-solving early intervention: A pilot study of stroke caregivers. Rehabil Nurs. 2007;32(2):68–76, 84. doi:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00154.x.

- Cameron JI, Naglie G, Green TL, et al. A feasibility and pilot randomized controlled trial of the “Timing it Right Stroke Family Support Program.”. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(11):1129–1140.doi:10.1177/0269215514564897.

- Wilz G, Barskova T. Evaluation of a cognitive behavioral group intervention program for spouses of stroke patients. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2508–2517. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.010.

- Draper B, Bowring G, Thompson C, Van Heyst J, Conroy P, Thompson J. Stress in caregivers of aphasic stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(2):122–130. doi:10.1177/0269215506071251.

- Perrin PB, Johnston A, Vogel B, et al. A culturally sensitive transition assistance program for stroke caregivers: examining caregiver mental health and stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(7):605–615.doi:10.1682/JRRD.2009.10.0170.

- Epstein-Lubow G, Beevers CG, Bishop DS, Miller IW. Family functioning is associated with depressive symptoms in caregivers of acute stroke survivors. ArchPhysMedRehabil. 2009;90(6):947–955. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2008.12.014.

- Badr H, Acitelli LK. Re-thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:44–48. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.001.

- Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental–contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. PsycholBull. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920.

- Lyons KS, Lee CS. The theory of dyadic illness management. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):8–28. doi:10.1177/1074840717745669.

- Cheng HY, Chair SY, Chau JP-C. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):30–44. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.01.005.

- Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2836–2852.doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000033.

- Bakas T, McCarthy M, Miller ET. An update on the state of the evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions. Stroke. 2017;48(5):e122–e125. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016052.

- Bishop D, Miller I, Weiner D, et al. Family intervention: telephone Tracking (FITT): A pilot stroke outcome study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21(Suppl 1):S63–74.doi:10.1310/tsr21S1-S63.

- Fens M, van Heugten CM, Beusmans G, Metsemakers J, Kester A, Limburg M. Effect of a stroke-specific follow-up care model on the quality of life of stroke patients and caregivers: A controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(1):7–15. doi:10.2340/16501977-1239.

- Ostwald SK, Godwin KM, Cron SG, Kelley CP, Hersch G, Davis S. Home-based psychoeducational and mailed information programs for stroke-caregiving dyads post-discharge: A randomized trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(1):55–62. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.777806.

- Terrill AL, Reblin M, MacKenzie JJ, et al. Development of a novel positive psychology-based intervention for couples post-stroke. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63(1):43–54.doi:10.1037/rep0000181.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping: A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: theory and empirical findings. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 1997;47:137–141.

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. ResNursHealth. 1997;20(2):169–177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199704)20:2<169::AID-NUR9>3.3.CO;2-B.

- Bakas T, Farran CJ, Austin JK, Given BA, Johnson EA, Williams LS. Content validity and satisfaction with a stroke caregiver intervention program. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41(4):368–375. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01282.x.

- Fisher RJ, Gaynor C, Kerr M, et al. A consensus on stroke early supported discharge. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1392–1397. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606285.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY. 2017; (Computer Program).

- Bakas T, Farran CJ, Austin JK, Given BA, Johnson EA, Williams LS. Stroke caregiver outcomes from the Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK). Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16(2):105–121. doi:10.1310/tsr1602-105.

- Gross R, McNeill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P. The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians’ perceptions of their patients. Women Health. 2008;48(2):123–144. doi:10.1080/03630240802313464.

- Mast MS, Hall JA, Roter DL. Disentangling physician sex and physician communication style: their effects on patient satisfaction in a virtual medical visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(1):16–22. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.020.

- Mast MS, Kadji KK. How female and male physicians’ communication is perceived differently. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(9):1697–1701. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.003.

- McCarthy MJ, Lyons KS, Schellinger J, Stapleton K, Bakas T Interpersonal relationship challenges experienced by stroke survivors and family caregivers. Social Work in Health Care. Forthcoming.

- McCarthy MJ, Bauer E. In sickness and in health: couples coping with stroke across the life span. Health Soc Work. 2015;40(3):e92–e100. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlv043.