ABSTRACT

Background:

The Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation Restrictions scale (USER-P-R) is a promising patient-reported outcome measure, but has currently not been validated in a hospital-based stroke population.

Objective

To examine psychometric properties of the USER-P-R in a hospital-based stroke population 3 months after stroke onset.

Methods

Cross-sectional study including 359 individuals with stroke recruited through 6 Dutch hospitals. The USER-P-R, EuroQol 5-dimensional 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5 L), Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Global Health Short Form (PROMIS-10), modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and two items on perceived decrease in health and activities post-stroke were administered in a telephone interview 3 months after stroke. The internal consistency, distribution, floor/ceiling effects, convergent validity and discriminant ability of the USER-P-R were calculated.

Results

Of all participants, 96.9% were living at home and 50.9% experienced no or minimal disabilities (mRS 0–1). The USER-P-R showed high internal consistency (α = 0.90) and a non-normal left-skewed distribution with a ceiling effect (21.4% maximum scores). A substantial proportion of participants with minimal disabilities (mRS 1) experienced restrictions on USER-P-R items (range 11.9–48.5%). The USER-P-R correlated strongly with the EQ-5D-5 L, PROMIS-10 and mRS. The USER-P-R showed excellent discriminant ability in more severely affected individuals with stroke, whereas its discriminant ability in less affected individuals was moderate.

Conclusions

The USER-P-R shows good measurement properties and provides additional patient-reported information, proving its usefulness as an instrument to evaluate participation after 3 months in a hospital-based stroke population.

Introduction

Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.Citation1 Due to advances in acute stroke care, such as intra-arterial thrombectomy, more individuals nowadays survive this event, but they may have to deal with chronic impairments after stroke.Citation1 Stroke patients may experience restrictions across multiple participation domains, such as work and leisure activities. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is a framework for the classification of health-related functional domains that defines participation restrictions as ‘problems an individual may have in involvement in life situations.’Citation2 Measuring participation in daily and social activities after stroke provides clinicians with valuable person-centered information on the impact of stroke on daily life, and promotes individually tailored goal-setting and shared decision making during neurorehabilitation.Citation3

Nevertheless, participation measures are not yet incorporated in current stroke audits or core outcome sets.Citation4 The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) remains the most commonly used assessment scale in clinical stroke care and stroke research, although it does not capture all aspects of outcome that are important to patients.Citation5 The use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in stroke care is increasing,Citation6 but most of these PROMs are health-related quality of life questionnaires (such as the EuroQol), which do not provide very specific information on participation in daily and social activities. In addition, the lack of consensus on the preferred participation measure may hamper regular assessment of participation.Citation7 Validation of participation measures commonly used for stroke patients, such as the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-Participation), could lead to further implementation of regular participation assessments in clinical stroke practice and stroke research.Citation6

The USER-Participation is a suitable measure to capture the multidimensional concept of participation as described in the ICF, as the items of the USER-Participation are based on the Participation chapters of the ICF.Citation8 The USER-Participation is a commonly used tool throughout Dutch stroke care and provides relevant information for clinical purposes, for example supporting individually tailored goal-setting during rehabilitation after stroke.Citation9 Recently, an expert panel advocated the use of the USER-Participation to measure participation as part of a minimum dataset of outcome measures to monitor recovery in patients with acquired brain injury.Citation10 Feasibility of the USER-Participation in stroke rehabilitation patients has been shown,Citation11 and may further improve by reducing the length of the questionnaire and focusing on participation restrictions. The Restrictions scale of the USER-Participation (USER-P-R) assesses restrictions of participation experienced, and comprises 11 items on restrictions experienced in e.g. work, household activities and social interaction.Citation12 Previous studies of the USER-P-R in stroke rehabilitation populations showed good internal consistency,Citation12–14 strong correlation with the ICF Measure of Activities and Participation-Screener (IMPACT-S)Citation12,Citation13 and the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA),Citation15 and better responsiveness than the Frenchay Activities Index and IMPACT-S.Citation8

In summary, the USER-P-R is a promising PROM to evaluate participation restrictions, but has currently only been validated in stroke rehabilitation settings. However, most people with stroke return home directly after hospital discharge without referral for inpatient rehabilitation treatment. Further validation of the USER-P-R in hospital-based stroke populations is needed to expand its applicability to all people with stroke regardless of discharge destination. Therefore, we examined the internal consistency, convergent validity and discriminant validity of the USER-P-R in a hospital-based stroke population 3 months after stroke onset.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional validation study. Recruitment took place in six Dutch hospitals between September 2017 and September 2018. Individuals who had suffered a stroke and were admitted to one of the participating hospitals were eligible for inclusion. No exclusion criteria were applied in this study. All eligible individuals received a letter informing them about this study, after which informed consent was acquired. The mRSCitation16 and all questionnairesCitation17,Citation18 were administered by a trained stroke nurse or nurse practitioner in a telephone interview 3 months after stroke.Citation19 Proxy interviews were performed if the individual with stroke was not able to answer the phone. Demographic (sex, age, marital status, residency and level of education) and stroke-related information (type and localization of stroke, severity of stroke, and activities of daily living [ADL] dependency) were obtained from medical records by the stroke nurse. The Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht declared that the study did not need formal approval under Dutch law (2017–441 C). All participating hospitals approved the study.

USER-participation restrictions scale

The USER-P-R consists of 11 items concerning difficulties experienced with vocational, leisure and social activities due to the stroke (for example, “Do you experience limitations due to your stroke in your daily life as regards household duties?”).Citation12,Citation20 For each item, four response categories are available: “not possible” (0), “with assistance” (1), “with difficulty” (2), and “without difficulty” (3). A “not applicable” option is available for all items, in case an activity is not performed for other reasons or a restriction is not attributed to the stroke. The total score of the Restrictions scale ranges from 0–100 and is based on applicable items. A higher score indicates a more favorable level of participation, i.e. fewer restrictions experienced.

Criterion measures

The EQ-5D-5 L consists of 5 items, each covering a health-related quality of life (HRQoL) domain, namely mobility, self-care, daily activities (e.g. work, study, housework, family or leisure activities), pain or discomfort and anxiety or depression; each item is scored on a 5-point scale: (1) “no problems,” (2) “slight problems,” (3) “moderate problems,” (4) “severe problems” and (5) “extreme problems/unable.”Citation21 The item scores were converted into a total value score, using the EuroQol crosswalk index value calculator, in which a perfect health score is valued as a score of 100 and a health state worse than death is valued as a negative score, anchoring death at a score of 0.Citation22 The EuroQoL has shown validity and reliability in stroke populations and is often used in cost-effectiveness analyses.Citation23–26

The PROMIS-10 consists of 10 items on physical, mental and social health and has been developed as a global health short-form questionnaire from the comprehensive PROMIS item banks.Citation27 One item regards social participation (“in general, please rate how well you carry out your usual social activities and roles, this includes activities at home, at work and in your community, and responsibilities as a parent, child, spouse, employee, friend etc.”) and is scored on a 5-point scale: (1) “poor,” (2) “fair,” (3) “good,” (4) “very good” and (5) “excellent.” The total score of the PROMIS-10 ranges from 0–100 (higher scores indicating better outcome). The PROMIS-10 has been recommended as a standard outcome measure after stroke by an international expert panel (International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement [ICHOM]).Citation28,Citation29 The PROMIS-10 has shown acceptable measurement properties in the stroke population.Citation3,Citation30,Citation31

The mRS is the most commonly used outcome measure in clinical stroke trials,Citation32 and its validity and reliability have been confirmed.Citation33 It measures disability due to stroke, incorporating body functions, activity and participation.Citation34 The mRS is a single ordinal seven-point scale (ranging from 0 to 6) that aims to categorize the level of disability after stroke.Citation21 The categories are “no symptoms” (mRS 0), “no significant disability, despite symptoms” (mRS 1), “slight disability” (mRS 2), “moderate disability: requires some help, able to walk” (mRS 3), “moderately severe disability: unable to walk, ADL dependent” (mRS 4), “severe disability: bedridden, requires constant nursing care” (mRS 5) and “death” (mRS 6). In the present study, mRS scores of 3, 4 and 5 were clustered because of the low numbers of participants in these categories.

Two self-developed items were used to evaluate patient-reported decrease in HRQoL associated with the onset of stroke. The first item asked participants to rate the decrease in health they experienced, associated with the onset of stroke. The second item asked participants to rate the decrease in activities they experienced, associated with the onset of stroke. The decrease experienced was measured on a 4-point response scale (“none,” “little,” “strong” and “very strong”) for both items. The responses “strong” and “very strong” were clustered for both items afterward, because few participants reported very strong decrease in health and activities.

Other measures

Stroke severity was assessed with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at hospital admission. Scores range from 0–42 and higher scores indicate more severe stroke.Citation35 ADL-dependency was assessed with the Barthel Index (BI) four days after stroke and at discharge from the hospital. Scores range from 0–20 and were dichotomized into “ADL dependent” (BI ≤ 17) and “ADL independent” (BI > 17). The BI is a validated measure often used in stroke research and practice.Citation36

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were used to describe participant characteristics and dependent variables. Floor and ceiling effects were considered present if > 15% of participants achieved the worst (floor effect) or best score (ceiling effect).Citation37 Internal consistency was examined by calculating Cronbach’s alpha; α > 0.70 was considered acceptable.Citation38 The USER-P-R items were dichotomized to quantify the presence of persistent restrictions across mRS levels. “With difficulty,” “with assistance,” and “not possible” were defined as “restrictions” and “without difficulty” was defined as “no restrictions.”

Bivariate associations between the USER-P-R, EQ-5D-5 L (total score and the item score regarding daily activities), PROMIS-10 (total score and the item score regarding social participation) and mRS were tested using Spearman correlations. Correlation coefficients were interpreted as weak (0.10), moderate (0.30) or strong (0.50).Citation39 A strong correlation was hypothesized and, if present, interpreted as a positive finding (convergent validity).

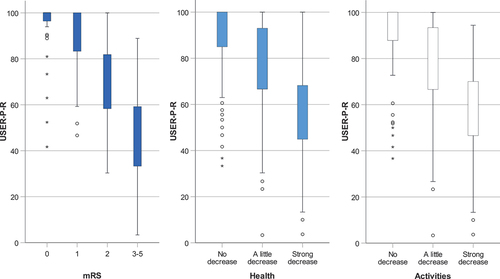

The distribution of the USER-P-R total scores across different mRS levels and the patient-reported decrease in health and activities since stroke was graphically displayed in a boxplot. High variance of USER-P-R total scores within mRS levels was interpreted as a positive finding (i.e. showing potentially relevant additional information to evaluate participation after stroke). We explored the discriminant ability of the USER-P-R by comparing mean USER-P-R scores between adjacent mRS levels and adjacent levels of patient-reported decrease in health and activities post-stroke. Effect sizes were calculated (Hedges’ g) and interpreted as weak (0.20), moderate (0.50) or strong (0.80).Citation40 An alpha <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics are presented in . A total of 360 participants were included in this study, 359 of whom completed the USER-P-R questionnaire and were available for analysis. A total of 143 participants (39.8%) were female and nearly all participants lived at home 3 months post-stroke. The majority of participants had suffered a mild ischemic stroke and most participants were ADL independent at discharge from the hospital.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n = 359).

The majority of participants had no significant disability (mRS 1) or slight disability (mRS 2), whereas only 12.1% of participants had moderate to severe disability (mRS 3–5) 3 months after stroke. Approximately one-third of participants did not report any decrease in health (36.7%) or in activities (33.1%) post-stroke. The EQ-5D-5 L showed a ceiling effect (21.2% maximum scores) and 41.8% did not experience any problems regarding daily activities. The PROMIS-10 was normally distributed (1.9% maximum scores) and few participants rated the item on social participation as “excellent” (3.9%) or “poor” (5.8%).

Internal consistency and distribution

The USER-P-R showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.90), and had a non-normal left-skewed distribution (skewness = −0.92, kurtosis = 0.23) with a ceiling effect (21.4% maximum scores). This ceiling effect in the USER-P-R mainly occurred in participants with no or no significant disabilities (mRS 0–1) 3 months after stroke and in participants who did not report any decrease in health or activities post-stroke. Participants with slight to severe disability (mRS 2–5) and participants who reported little to strong decreases in health and in activities post-stroke showed greater variation in USER-P-R scores compared to participants with no or no significant disability (mRS 0–1) and participants who did not report any decrease in health or activities post-stroke ().

Figure 1. Distribution of the USER-Participation Restrictions scale across mRS scores (dark blue) and across different levels of patient-reported decrease in health (light blue) and in daily activities (white) 3 months after stroke.

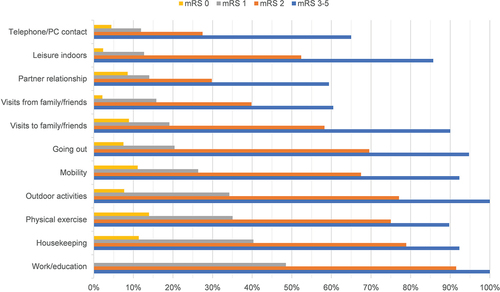

The percentage of participants experiencing restrictions regarding the items of the USER-P-R increased with higher mRS levels (). A few participants with no disabilities according to the mRS (mRS 0) experienced restrictions regarding USER-P-R items (range 0–14%), whereas a considerable percentage of participants with no significant disabilities (mRS 1) experienced restrictions on several USER-P-R items (range 11.9–48.5%), especially the items on work/education, housekeeping, physical exercise and outdoor activities (48.5%, 40.3%, 35.0% and 34.2%, respectively). Almost all participants with moderate to severe disabilities (mRS 3–5) experienced restrictions regarding USER-P-R items on work/education and outdoor activities, whereas relatively few participants experienced restrictions in social activities (such as partner relationship and visits to/from family/friends).

Figure 2. Percentage of participants experiencing restrictions regarding the items of the USER-Participation Restrictions scale across the different mRS levels.

Convergent validity

The USER-P-R showed a strong and significant negative correlation with the mRS and the EQ-5D-5 L item score regarding daily activities, and a strong and significant positive correlation with the EQ-5D-5 L total score, the PROMIS-10 total score and the PROMIS-10 item score regarding social participation ().

Table 2. Frequencies and descriptive statistics of the USER-participation restrictions scale.

Discriminant ability

The USER-P-R showed strong ability to detect differences between participants with no significant disabilities versus those with slight (mRS 1 vs. 2) and those with slight versus moderate to severe disabilities (mRS 2 vs. 3–5), whereas its ability to detect differences between participants with no versus those with no significant disabilities (mRS 0 vs. 1) was moderate (). The USER-P-R showed a strong ability to detect differences between participants who reported little versus strong decrease in health and in activities post-stroke, whereas its ability to detect differences between participants who did not report any decrease versus those who reported little decrease in health and activities post-stroke was moderate.()

Table 3. Spearman correlations (rho) between the USER-Participation Restrictions scale, the modified Rankin Scale, EQ-5D-5 L (including daily activities item score) and PROMIS-10 (including social participation item score).

Table 4. Ability of the USER-Participation Restrictions scale to discriminate between adjacent mRS levels (mRS 0 vs. mRS 1, mRS 1 vs. mRS 2, mRS 2 vs. mRS 3–5) and different levels of patient-reported decrease in health and in activities post-stroke.

Discussion

We found reasonably good measurement properties of the USER-P-R when administered 3 months post-stroke in a large hospital-based cohort of community-living participants in the Netherlands. The USER-P-R had a slight ceiling effect (21.4%), but high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.90), good convergent validity (strong correlations with the EQ-5D-5 L, PROMIS-10 and mRS), moderate discriminant ability in less severely affected individuals with stroke and excellent discriminant ability in more severely affected individuals with stroke. Many individuals with stroke experienced restrictions in USER-P-R items, even persons who had no or minimal disabilities (mRS 0–1). In summary, the USER-P-R proved a useful and valid instrument to evaluate participation after 3 months in a hospital-based stroke population.

The observed ceiling effect of the USER-P-R mainly occurred in participants with no disabilities (mRS 0), 70.2% of whom had the maximum score. In the group of participants with mild to severe disabilities after stroke (mRS 1–4), 14.1% had the maximum score. A previous study among former rehabilitation outpatients (35% with stroke or traumatic brain injury) reported a comparable ceiling effect (19%) for USER-P-R.Citation12 The discriminant ability of the USER-P-R to detect differences among less severely affected individuals with stroke (mRS 0 vs. 1, and individuals experiencing no vs. little decrease in health/activities) was only moderate, whereas excellent discriminant ability was found for more severely affected individuals with stroke (mRS 2 vs. mRS 3–5, and individuals experiencing little vs. strong decrease in health/activities). These findings indicate that the USER-P-R is most useful for stroke patients with chronic symptoms.

About 70% of the participants with minimal disabilities according to the clinician’s judgment (mRS 1) experienced restrictions regarding USER-P-R items, especially regarding the items on work (48.5%), housekeeping (40.3%), physical exercise (35.0%) and outdoor activities (34.2%). These findings show the potential of the USER-P-R to provide clinicians with valuable person-centered information on the impact of stroke on daily life, even for mildly affected stroke patients. Similar results were yielded in a comparable Dutch hospital-based stroke population (Restore4Stroke Cohort).Citation41 Despite the Restore4Stroke cohort (n = 136) also largely consisted of relatively mildly affected stroke patients, more than half of the stroke patients experienced restrictions in the USER-P-R items on work, housekeeping, physical exercise and outdoor activities at 2 and 6 months after stroke onset.Citation41 In another stroke sample recruited in Dutch rehabilitation centers after completion of a multidisciplinary individually based outpatient rehabilitation program (n = 111, median time since stroke onset = 3.4 months), persisting restrictions in USER-P-R items on physical exercise (50.0%), housekeeping (44.5%) and outdoor activities (40.9%) were most frequently reported.Citation20 Population differences (patient recruitment in hospitals vs. rehabilitation centers) and differences in the provided rehabilitation treatment may explain the slight differences between these studies.

Restrictions in social activities (partner relationship, visits to/from family or friends) were less frequent in our study. These results are in line with those of a recent study investigating the USER-Participation scores across different diagnostic groups, including stroke (n = 534) which concluded that participation restrictions were most often experienced in the productivity domain (work, education, housekeeping), followed by the leisure domain (physical exercise, going out, outdoor activities) and least often in the social domain (relationships with partner/family/friends).Citation9

To our knowledge, correlations between the USER-P-R and the mRS, EQ-5D-5 L or PROMIS-10 have not been examined previously. The weak correlation between the USER-P-R and the social participation item of the PROMIS-10, weaker than the correlation with the PROMIS-10 total score, is striking. Most participants chose the middle response category of this item (“good”), which may have reduced the correlation between the item score and the USER-P-R. This could be explained by the differences in response categories and the underlying goal of both PROMs. Maximum scores on the USER-P-R items indicate the absence of problems/difficulties in participation, whereas the maximum scores on the PROMIS-10 items indicate “excellent” HRQoL (and the middle response category already indicates “good” HRQoL outcome).

The use of PROMs for the assessment of participation after stroke, such as the USER-P-R, has many advantages, but the implementation of PROMs may face some challenges.Citation6 A systematic review of stroke-related randomized controlled trials found that only 21% used PROMs, and in case a PROM was used, they most commonly measured physical function and emotional status, and rarely measured participation.Citation42 It has been suggested that retention and response rates of PROMs in stroke aftercare could be further enhanced by reducing the size of the questionnaires.Citation11 The USER-Participation for patients with acquired brain injury has been recommended by experts as a measurement instrument for participation,Citation10 and focusing on the restrictions scale may improve the feasibility of the USER-Participation in clinical stroke care, as this scale is notably shorter (11 items), is easy to administer, and supports individually tailored goal-setting in rehabilitation after stroke. On the other hand, focusing on the restrictions scale comes at the expanse of losing potential relevant information on the frequency of participation and the satisfaction with participation after stroke.

Study limitations

The study population mainly consisted of community-living and mildly affected individuals with stroke. As a consequence, participants with mRS scores 3–5 were clustered, and no comparisons could be made between these groups. This limits the generalizability of our results to patients with more severe stroke. However, our sample does reflect the severity of stroke in the general hospital population, as mild ischemic strokes are most common.Citation19 Furthermore, restrictions in participation change over time,Citation43 meaning that administering the USER-P-R at another point in time after stroke onset could have yielded different results. Lastly, the ability of the USER-P-R to detect change over time could not be assessed in this study.

Conclusions

The USER-P-R is a valid measurement instrument to monitor participation restrictions in routine outpatient care 3 months after stroke. A considerable number of stroke patients who are “mildly affected,” according to the clinician’s judgment, still experience restrictions on USER-P-R items, especially in the productivity and leisure domains. The USER-P-R appears to be most suitable for individuals with stroke who have chronic disabilities or experience decreased HRQoL since their stroke.

Clinical implications

The USER-P-R seems appropriate as a screening instrument to detect post-stroke restrictions in participation, even in patients with minor strokes. Our findings show the importance of assessing patient-reported information on restrictions in participation during follow-up after stroke, as it provides clinicians with relevant person-centered information on the impact of stroke. Regular assessment of the USER-P-R in stroke aftercare could aid timely referral to individually tailored rehabilitation interventions and prevent long-term participation restrictions.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors have made substantive contributions to the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Corina Puppels (nurse practitioner), Wilma Pellikaan (nurse practitioner), Mariska de Kleuver (stroke nurse), Lianne van Bemmel (stroke nurse), Annemarie Mastenbroek (stroke nurse), Petra Zandbelt (nurse practitioner), Marloes van Mierlo (researcher), Ingrid den Besten (stroke nurse), Elly Greeve (stroke nurse), Hanneke van Langeveld-Pranger (stroke nurse) and Erna Bos-Verheij (stroke nurse) for including the participants, conducting telephone interviews and collecting data.

This study was performed at the following institutions:

Flevoziekenhuis, Department of Neurology, Almere, The Netherlands

Franciscus Gasthuis, Department of Neurology, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands

Rijnstate hospital, Department of Neurology, Arnhem, The Netherlands

St. Antonius hospital, Department of Neurology, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands

University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request ([email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johnson CO, Nguyen M, Roth GA, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):439–458.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1.

- World Health Organization. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health - ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization. ed.; 2001.

- Katzan IL, Thompson NR, Lapin B, Uchino K. Added value of patient-reported outcome measures in stroke clinical practice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:7. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.005356.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Hurme S, Laimi K. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) and the WHO minimal generic set of domains of functioning and health versus conventional instruments in subacute stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(9):675–682. doi:10.2340/16501977-2583.

- Taylor-Rowan M, Wilson A, Dawson J, Quinn TJ. Functional assessment for acute stroke trials: properties, analysis, and application. Front Neurol. 2018;9:(MAR):1–10. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00191.

- Reeves M, Lisabeth L, Williams L, et al. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for acute stroke: rationale, methods and future directions. Stroke. 2018;49(6):1549–1556.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018912.

- Engel-Yeger B, Tse T, Josman N, Baum C, Carey LM. Scoping review: the trajectory of recovery of participation outcomes following stroke. Behav Neurol. 2018;2018:5472018. doi:10.1155/2018/5472018.

- Van Der Zee CH, Kap A, Mishre RR, Schouten EJ, Post MWM. Responsiveness of four participation measures to changes during and after outpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(11):1003–1009. doi:10.2340/16501977-0879.

- Mol TI, van Bennekom CA, Schepers VP, et al. Differences in societal participation across diagnostic groups: secondary analyses of 8 studies using the utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. March 2021; Published online. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.02.024.

- Domensino AF, Winkens I, JCM VH, Cam VB, Van Heugten CM. Defining the content of a minimal dataset for acquired brain injury using a Delphi procedure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01286-3.

- Groeneveld IF, Goossens PH, van Meijeren-Pont W, et al. Value-based stroke rehabilitation: feasibility and results of patient-reported outcome measures in the first year after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(2):499–512.doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.10.033.

- Post MWM, Van Der Zee CH, Hennink J, Schafrat CG, JMA V-M, Van Berlekom SB. Validity of the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(6):478–485. doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.608148.

- Van Der Zee CH, Post MW, Brinkhof MW, Wagenaar RC. Comparison of the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation with the ICF measure of participation and activities screener and the WHO disability assessment schedule ii in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(1):87–93. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.236.

- Mader L, Post M, Ballert C, Michel G, Stucki G, Brinkhof M. Metric properties of the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation (USER-Participation) in persons with spinal cord injury living in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(2):165–174. doi:10.2340/16501977-2010.

- Van Der Zee CH, Baars-Elsinga A, JMA V-M, Post MWM. Responsiveness of two participation measures in an outpatient rehabilitation setting. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(3):201–208. doi:10.3109/11038128.2012.754491.

- Janssen PM, Visser NA, Dorhout Mees SM, Klijn CJ, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Comparison of telephone and face-to-face assessment of the modified Rankin Scale. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29(2):137–139. doi:10.1159/000262309.

- Lam KH, Kwa VIH. Validity of the PROMIS-10 global health assessed by telephone and on paper in minor stroke and transient ischaemic attack in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2018;8:7. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019919.

- Chatterji R, Naylor JM, Harris IA, et al. An equivalence study: are patient-completed and telephone interview equivalent modes of administration for the EuroQol survey? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017. 15(1). 10.1186/s12955-017-0596-x.

- Kuhrij LS, Wouters MWJM, van den Berg-Vos RM, de Leeuw FE, Nederkoorn PJ. The Dutch acute stroke audit: benchmarking acute stroke care in the Netherlands. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(4):361–368. doi:10.1177/2396987318787695.

- Van Der Zee CH, JMA V-M, Lindeman E, Kappelle LJ, Post MWM. Participation in the chronic phase of stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013;20(1):52–61. doi:10.1310/tsr2001-52.

- Broderick JP, Adeoye O, Elm J. Evolution of the modified rankin scale and its use in future stroke trials. Stroke. 2017;48(7):2007–2012. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017866.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715.doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008.

- Hunger M, Sabariego C, Stollenwerk B, Cieza A, Leidl R. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in German stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1205–1216. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-0024-3.

- Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–1727.doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4.

- Golicki D, Niewada M, Karlinska A, et al. Comparing responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS in stroke patients. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1555–1563.doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0873-7.

- Golicki D, Niewada M, Buczek J, et al. Validity of EQ-5D-5L in stroke. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(4):845–850.doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0834-1.

- Tucker CA, Escorpizo R, Cieza A, et al. Mapping the content of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)) using the International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(9):2431–2438.doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0691-y.

- Barile JP, Reeve BB, Smith AW, et al. Monitoring population health for healthy people 2020: evaluation of the NIH PROMIS(R) global health, CDC healthy days, and satisfaction with life instruments. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(6):1201–1211.doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0246-z.

- Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, et al. An international standard set of patient-centered outcome measures after stroke. Stroke. 2016;47(1):180–186.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898.

- Katzan IL, Lapin B. PROMIS GH (Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system global health) scale in stroke: a validation study. Stroke. 2018;49(1):147–154. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018766.

- Katzan IL, Thompson N, Uchino K. Innovations in Stroke: the Use of PROMIS and NeuroQoL scales in clinical stroke trials. Stroke. 2016;47(2):e27–30. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011377.

- Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, Lees KR. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3393–3395. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557256.

- Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1091–1096. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6.

- Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(7):603–612. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70495-1.

- Hinkle JL. Reliability and validity of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale for neuroscience nurses. Stroke. 2014;45(3):e32–4. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004243.

- Duffy L, Gajree S, Langhorne P, Stott DJ, Quinn TJ. Reliability (inter-rater agreement) of the Barthel Index for assessment of stroke survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44(2):462–468. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.678615.

- Terwee CB, Bot SDM, De Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42.doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012.

- Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;80(1):99–103. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18.

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd: Routledge (Psychology Press), Taylor & Francis Group, New York; 1988. 10.4324/9780203771587.

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4(NOV). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863.

- de Graaf JA, van Mierlo ML, Post MWM, Achterberg WP, Kappelle LJ, Visser-Meily JMA. Long-term restrictions in participation in stroke survivors under and over 70 years of age. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(6):637–645. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1271466.

- Price-Haywood EG, Harden-Barrios J, Carr C, Reddy L, Bazzano LA, van Driel ML. Patient-reported outcomes in stroke clinical trials 2002–2016: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(5):1119–1128. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-2053-7.

- Verberne DPJ, Post MWM, Köhler S, Carey LM, JMA V-M, van Heugten CM. Course of social participation in the first 2 years after stroke and its associations with demographic and stroke-related factors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2018;32(9):821–833. doi:10.1177/1545968318796341.