Abstract

Based on the theory of transaction cost economics, the paper argues that by vertically organizing political exchange, populist regimes reduce market-type political transaction costs—bargaining, enforcement and information costs—of democracy. However, management-type political transaction costs—organizational costs, partly stemming from corruption—rise as populists in power leverage government control through hierarchically organized clienteles. Transaction cost economics suggest that a shift from democratic towards authoritarian populist regimes occurs when formal and informal political institutions prove unable to maintain horizontal political exchange, and demand for increased government discretion grows. This is demonstrated on Viktor Orbán’s authoritarian populist regime in Hungary.

INTRODUCTION

This paper seeks to provide an institutional economics approach to a political phenomenon: authoritarian populism in power. This is not an unprecedented research question, but it calls for some explanation: why do we need an institutional economics interpretation of a political regime run by authoritarian populists? My answer is, because we want to understand better what makes this type of governance increasingly popular globally, in both developed and developing countries. In dealing with this problem, I will rely on concepts imported from transaction cost economics and rephrased in a political context, such as vertical and horizontal political exchange and political transaction costs. As I will show, these concepts turn out to be useful if one is seeking to explain the demise of democracy and the rise of authoritarian populism. By using this conceptual apparatus, I will also be able to demonstrate why and in what sense populism is typically non-democratic even if it relies on popular vote; how it transforms democracies into a sort of democratically approved authoritarianism; why and how it relies on clientele building; and what kind of trade-offs it faces in terms of political transaction costs.

The theory, which has antecedents both in economics and in political science, will be tested on the case of Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán since 2010. I will show how Orbán has transformed the underlying structure of political exchange and what this change has meant in terms of political transaction costs. I will present the institutional conditions of Orbán’s authoritarian turn and the redistributive policies he has applied, and will also explain why his rule has so far turned out to be politically highly successful despite rising corruption. Although Hungary is in many ways an extreme case with respect to authoritarian populism, Orbán’s influence appears to be growing across Europe. Hence, understanding his success may help prevent the spread of authoritarian populism across the continent and beyond.

By examining the authoritarian populist challenge we also examine democracy and can better understand the institutional conditions for sustaining it. Once these are recognized, however, one may have to admit that democracy as a political system is not always attainable, and that sometimes authoritarian populism, sad to say, might be the relatively most democratic of available political options. This is by no means an apology for authoritarian populists, who exploit the weaknesses of democracy for their own benefit, create economic and political rents for themselves and their cronies, and damage long-term social and economic development perspectives. Yet, what they do might still be an equilibrium solution to the problem of political coordination in institutionally underdeveloped democracies.

Authoritarian populist regimes are majoritarian—or illiberal—democracies, in which minority political rights are under-institutionalized, and hence the effective threat of opposition takeover is limited, although existing.Footnote1 The major competitive advantage of such regimes is their capacity for providing direct political legitimation for incumbents without exposing them to permanent political bargaining with non-establishment groups. In this way, the bargaining, enforcement, and information costs of democracy can be reduced, while political management costs—among which the maintenance of political and business clienteles with concomitant corruption costs play prominently—might increase. This is the underlying trade-off of authoritarian populism that I will discuss both theoretically and empirically in this paper.

In what follows, I will first present a literature review and some empirical data on populism. Next, I will elaborate on the notion of political transaction costs and their applicability to populist regimes. I will then test my theoretical assumptions on contemporary Hungary as a textbook case of authoritarian populism in power. Finally, I will draw some conclusions.

WHAT IS AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM? THEORY AND EMPIRICAL DATA

Populism is a contested term that carries different meanings in political science and in everyday political conversations. In this paper, I treat it as a form of governance based on a majoritarian approach to power that entails a disrespect for minority rights—a constituent part of democracy—and hence necessarily implies a degree of authoritarianism. In this sense, for this paper, all populisms are authoritarian to some extent. I will briefly touch upon the literature on democratic populism with no ambition of creating a theoretical position toward it. I will only show that even those left-wing populists who are supposed to represent democratic populism have a dubious democratic track record.

Populism is a political ideology that questions the legitimacy of traditional political elites by claiming to be the true, and the only true, representative of the people. Populists have a Manichean worldview: political actors are either good or bad, and enemies of populism are inherently bad as they are also enemies of the people. In consequence, populists undermine political plurality by questioning the legitimacy of their rivals (Müller Citation2016; Pappas Citation2014). Furthermore, for populists, the “people” themselves represent justice and morality (Shils Citation1956); hence they claim to establish a direct, non-institutionalized link between the government and the electorate.Footnote2

Technically speaking, authoritarian populism is a modernized version of charismatic rule. In Max Weber’s classic treatment, a charismatic ruler “derives his authority not from an established order and enactments, as if it were an official competence, and not from custom or feudal fealty, as under patrimonialism. He gains and retains it solely by proving his powers in practice. He must work miracles, if he wants to be a prophet. He must perform heroic deeds, if he wants to be a warlord. Most of all, his divine mission must prove itself by bringing well-being [emphasis in the original] to his faithful followers; if they do not fare well, he obviously is not the god-sent master” (Weber Citation1978 [1922], 1114). In this sense, populist leaders are modern-day charismatic rulers who retain power as long as they are seen to work miracles: they appear to alter international relations, transform the economic system, or bring about a sense of “social justice” (Tismaneanu Citation2000). In that, they rely on their personal charisma, without which they cannot succeed: their power is personalized, and their followers depend on them personally (Gurov and Zankina Citation2013).

Theoretically speaking, populism is a “thin-centered” political ideology attached to a broader, more established ideological appeal (Stanley Citation2008). Populists typically use more elaborate and politically better- established ideologies to carve out a unique selling point in the political market. In the case of right-wing populists, this is typically nationalism or another form of right-wing authoritarianism. In the case of left-wing populists, this is typically a version of radical socialism (Mudde Citation2004).

Federico Finchelstein places populism in a context of post-totalitarianism. He argues that modern Latin American populism, most saliently embodied in Peronism,Footnote3 is the post–World War II version of totalitarianism, or “an electoral form of post-fascism” (Finchelstein Citation2014, 469). In his account, populists dismiss institutionalized constraints on executive power but are reluctant to introduce explicitly totalitarian rule. Although it embraces electoral democracy,

[i]n populism, the legitimacy of the leader is not only based in the former’s ability to represent the electorate but also on the belief that the leader’s will goes far beyond the mandate of political representation. […] The elected leaders act as the personification of popular sovereignty exerting a great degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the majorities that have elected them. […] As an authoritarian version of electoral democracy, populism invoked the name of the people to stress a form of vertical leadership, to downplay political dialogue, and to solve a perceived crisis of representation by suppressing democratic checks and balances. (Finchelstein Citation2014, 477)

Hence, populists exert autonomy vis-à-vis their own voters: they not only exert limitations on minority rights, they also reduce their accountability to the majority that elected them in the first place. They tend to rely on a perceived crisis of representation—a democratic emergency—that they solve by weakening checks and balances; hence by eliminating liberal democracy.

In another theoretically similar contribution, Takis Pappas (Citation2016) has argued that populism is “democratic illiberalism,” or in other words “populism is always democratic but never liberal” (28–29). This is because populists, on one hand, need to rely on popular legitimation so that they can claim to be the true, and the only true, voice of the people. Hence, they hold elections. On the other hand, they—being the true and the only true voice of the people—cannot concede electoral defeats. As there are no better (i.e., more credible, just, morally entitled, and so forth) representatives of the people than they themselves, any contradicting electoral results should be outright dismissed. Cases in point include Viktor Orbán, who questioned the legitimacy of both the 2002 and the 2006 Hungarian parliamentary elections, which he lost, as well as Donald Trump, who called the electoral process “rigged” before the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and declared that he would not concede defeat if his opponent won.

Yet another author treating populism as an authoritarian, anti-democratic approach to politics is Jan-Werner Müller (Citation2016), who considers it “a degraded form of democracy that promises to make good on democracy’s highest ideals (‘Let the people rule!’).” In Müller’s account, populism seeks to gain electoral support for an anti-liberal political agenda that aims at reducing people’s effective political choice. The question here is whether political regimes built and dominated in a populist fashion can be meaningfully called democracies. Müller’s answer is an emphatic no: Populists are anti-pluralists and anti-pluralists cannot be democrats, as democracy is per se about pluralism. This is in line with János Kornai (Citation2016), who argues that democracy cannot be illiberal for the same reason.

Nevertheless, an influential part of the literature—and some important political actors referring to it—consider populism a potentially important democratic force. The late Argentinian philosopher Ernesto Laclau (Citation2005) argued that populism mobilizes a politically and economically oppressed electorate against democratically unaccountable technocratic elites, multinational companies, and international institutions. Newly emerging left-wing populist parties, such as Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, occasionally make explicit references to such views, but older, more traditional left-wing parties, such as Die Linke in Germany and the Workers’ Party in Brazil, can also be considered left-wing democratic populist in this sense. Other prominent left-wing political leaders, such as Bernie Sanders in the United States and Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom, are also sometimes called progressive populists. Referring to their examples and emphasizing the structural weakness of democratic legitimation in capitalism, Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2017) endorse populism as a potentially progressive political force.

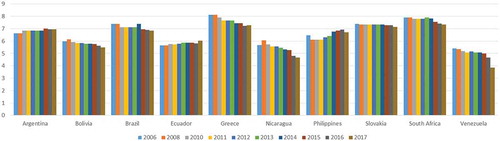

In this context, populism is meant to be democratic and at times even revolutionary. However, there is little empirical evidence for populists, whether left- or right-wing, making a country more democratic. Neither Syriza in Greece, nor the Latin American left-wing populist presidents such as Lula da Silva in Brazil, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, or Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, made democracy better performing. Instead, they appear to have overtaken existing institutions and pursued their own political agenda, adopting a majoritarian approach to power (cf. de la Torre Citation2016; Ellner Citation2012). Other left-wing populists in power, such as Robert Fico in Slovakia (Meseznikov and Gyárfásová Citation2018; Walter Citation2017), Jacob Zuma in South Africa (Gumede Citation2008; Southall Citation2009), or Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines (Heyderian Citation2018), have similarly poor democratic track records (see ).

GRAPH 1. Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index scores for countries with left-wing populist governments in some part of the 2006–2017 period.

Note: Countries are scored on a scale of 0 to 10 by EIU based on 60 indicators. Scores from 0 to 4 indicate “authoritarian regimes,” from 4 to 6 “hybrid regimes,” from 6 to 8 “flawed democracies,” and from 8 to 10 “full democracies.” Only countries with at least a score of 4 and a maximum of 8 (“hybrid regimes” and “flawed democracies”) are listed. Greece has been below 8 since 2010, first under left-wing, then right-wing, then a coalition of left-wing and right-wing populist governments. South Africa was never above 8 in this period, although approached “full democracy” status in some years. Venezuela declined to below 4, indicating outright dictatorship in 2017. Data source: EIU (https://infographics.economist.com/2018/DemocracyIndex/)

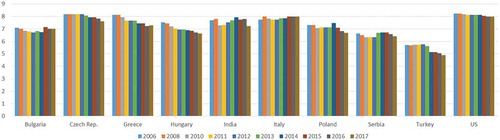

However, right-wing populism has been even more associated with democratic decay, as suggested by country cases such as Bulgaria (Gurov and Zankina Citation2013; Zankina Citation2016), the Czech RepublicFootnote4 (Pehe Citation2018), Hungary (Bozóki Citation2015; Enyedi Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2015), India (Chacko Citation2018), Italy (Verbeek and Zaslove Citation2016), Poland (Stanley Citation2018, Citation2015), Serbia (Stojanovic Citation2017), and Turkey (Boyraz Citation2018; Hadiz Citation2014; Yabanci and Taleski Citation2018), as well as the United States (Inglehart and Norris Citation2017) (see ).

GRAPH 2. Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index scores for countries with right-wing populist governments in some part of the 2006–2017 period.

Note: Countries are scored on a scale of 0 to 10 by EIU based on 60 indicators. Scores from 0 to 4 indicate “authoritarian regimes,” from 4 to 6 “hybrid regimes,” from 6 to 8 “flawed democracies,” and from 8 to 10 “full democracies.” Only countries with at least a score of 4 and a maximum of 8 (“hybrid regimes” and “flawed democracies”) are listed. Consequently, Russia did not make it to the graph as its score has been below 4 since 2011, and hence it has been considered an outright dictatorship. The Czech Republic dropped to below 8 in 2014 and has been declining ever since, in line with the growing influence of Andrej Babis, first as finance minister (2014–2017), subsequently as prime minister (2017–). Greece has been below 8 since 2010, first under left-wing, than right-wing, than a coalition of left-wing and right-wing populist governments. India and Italy were never above 8 in this period, although they approached “full democracy” status in some years. The United States dropped below 8 in 2016, the year President Trump was elected. Data source: EIU (https://infographics.economist.com/2018/DemocracyIndex/)

In short, empirical data suggest that, whether left- or right-wing, populists tend to weaken democracy by undermining the system of checks and balances and exercising a majoritarian approach to power. Their political appeal, however, does not fall from sky, but responds to tangible electoral needs. To explain the political dynamics they use and often themselves generate, I will employ the theory of transaction cost economics and adapt it to analyze political exchange in the next section. For this, I will treat authoritarian populism as a political mechanism for transforming the dominant character of political exchange by internalizing a large share of political transactions into vertical power hierarchies (such as government-sponsored clienteles), while maintaining elections (the principal form of horizontal political exchange in democracies) as a means of political legitimation.

POPULISM AND POLITICAL TRANSACTION COSTS

Institutional economics argue that most economic exchanges imply considerable transaction costs. These include (i) search and information costs, (ii) the costs of bargaining and contracting, and (iii) the costs of policing and enforcing contracts (Williamson Citation1985). Not all economic exchanges carry significant transaction costs, though. Recurring market transactions typically do not imply substantial uncertainties and hence do not impose considerable transaction costs on transacting partners (Williamson Citation1979). For example, one can buy or sell a loaf of bread in the shop around the corner with practically no information, bargaining, or enforcement costs. Efficient financial markets also carry low transaction costs: information is symmetric, market participants are numerous, and transactions are completed transparently. Note, however, that both of these latter types of transactions—buying and selling bread in a food store and buying and selling stocks on financial markets—take place in institutionally developed markets, in which contractual arrangements are standardized and mutually understood. In other words, transactions are supported by an efficient institutional environment, consisting of both formal and informal institutions.

Formal institutions include laws and formalized mechanisms of sanctioning unlawful behavior. Informal institutions are norms and customs, whose violation typically does not entail formalized sanctions yet may bring about severe financial and/or non-financial costs. In modern economies, institutions are capable of handling complex exchanges with sufficiently low transaction costs. In consequence, economic quality is closely associated to institutional quality, whereas the latter depends on both formal and informal institutions and their mutual compatibility (North Citation1991).

Governance is about the management of transaction costs. In the classic treatment by Ronald H. Coase (Citation1937), firms are conceptualized as organizations producing institutional mechanisms to handle the transaction costs of complex production processes. As producing cars, skyscrapers, or collateralized corporate loans requires the cooperation of numerous individuals adjusting their activities, they engage in collective action organized by hierarchical firms. In other words, in complex production processes, vertical integration tends to be more efficient than horizontal market relations. Yet, even this has been changing in recent decades as new information and production technologies are making loosely integrated horizontal networks increasingly competitive vis-à-vis hierarchical firms (Hámori and Szabó Citation2016).

By analogy, political governance is about the management of political transaction costs. These are the costs of political exchange in terms of reaching agreements with, and imposing political decisions on, members of society. Depending on formal and informal political institutions and their mutual compatibility, reaching agreements and enforcing them—i.e., bargaining and enforcement costs—can be substantial. In addition, disseminating political information in election campaigns and with respect to major political debates can also be costly—i.e., information costs.Footnote5

Societies deal with these costs by creating political institutions, such as constitutions, electoral rules, campaign finance regulations, formal and informal decision-making procedures, political parties, lobbying organizations, and political morale, as well as the institutional mechanisms of public discourse, including the political press.Footnote6 They determine how societies solve the problem of political coordination. Obviously, not all political systems are democratic, though. The more centralized and concentrated political power is, the lesser the role of horizontal political exchange. Up until the late eighteenth century, democratic governance practically had not existed. Political elites did not seek direct popular legitimation, and non-privileged social groups seldom demanded institutionalized power. However, with the rise of political nations and the principle of equality before the law, political governance has become increasingly dependent on explicit political consent by non-elite groups. In the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, elections as a form of allocating political power gradually came to the fore in advanced societies, with an increasing part of the adult population incorporated into the electorate (Acemoglu and Robinson Citation2000; Przeworski Citation2009).

However, as Seymour Martin Lipset (Citation1959) noted, for democracy to be sustained, a vast array of formal and informal institutions need to be in place, including a general schooling system, a meaningful public discourse, and the popular appreciation of democratic values. In their absence, democracy is likely to give way to dictatorship, as occurred in most parts of decolonized Africa in the second half of the twentieth century (Barro Citation1997). Using transaction cost economics terminology, this can be interpreted as transaction costs of horizontal political exchange being unsustainably high in the absence of supporting institutions, so that societies resort to a political system based on vertical political exchange—i.e., dictatorship.Footnote7

Autocracies are in between democracy and dictatorship: political power is to some extent contested but there are apparent constraints on political competition, in most historical cases through a limitation on franchise (cf. Kornai Citation2016). In the case of populist regimes, the franchise is unlimited but effective contestability of power remains constrained through incumbent advantages that typically prevent fair elections.Footnote8 Populist regimes rely on these elections as means of direct popular legitimation, but effectively internalize most major political exchange into vertical power hierarchies controlled by incumbents. Clientele-building plays a major role, and government-controlled clienteles tend to replace the role of formal political institutions. In this sense, populists “de-institutionalize” the political system, enabling an increased level of political discretion by office-holders while conducting vertical political exchange. Through this, government officials appear to be wielding increased authority and exercising “more efficient” power. At times of social, political, and economic emergencies, such “efficiency” tends to be particularly sought for by the electorate.

Increased discretion in decision making implies the internalization of political transactions into vertical power structures, such as government-controlled clienteles and all-encompassing political parties. As decisions are centralized and more concentrated, bargaining and enforcement costs are reduced. However, other types of political transaction costs may increase at the same time. First of all, vertical power structures need to be financed. They can be held together as long as participants enjoy the flow of government-allocated resources. Hence, populist states are not small, even if they privatize state-owned firms to friendly businesses. Second, increased discretion in decision making implies, by definition, fewer checks and balances. This not only results in fewer institutionalized constraints on bad policies, but it also creates more opportunity for corruption, which is a particularly severe problem for populist regimes. As public scrutiny over government activities is weakened, office holders and members of government-controlled clienteles have strong incentives for private profit seeking through political means (cf. Mungiu-Pippidi Citation2006, Citation2015). The financing needs of clienteles and the costs of policy distortions, including corruption, create significant political transaction costs for populist regimes—transaction costs that can be conceptualized to the analogy of management costs for firms in mainstream transaction cost economics.

Now, the efficiency of populist rule as a solution to the problem of political coordination depends on the relation between the reduction of bargaining and enforcement costs (related to democratic political markets) and the rise in political management costs (related to the internalization of political transactions into clienteles). Thus, Acemoglu and Robinson (Citation2012) are wrong: “inclusive” political and economic institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson’s term for institutional mechanisms based on horizontal exchange on both political and economic markets) are not always superior to “extractive” ones (which encompass vertical exchange). On the contrary: in most parts of the world in most periods of human history, in the absence of the institutional bases for democratic power-sharing, extraction of resources by political and economic elites has been a more efficient mechanism for governing political and economic markets than inclusion would have been.

When societies do not possess adequate institutional underpinnings of democracy and market capitalism, horizontal exchange-based political and economic coordination becomes unsustainable, and societies resort to some form of authoritarianism (i.e., vertical exchange-based coordination), among which authoritarian populism appears to be the most democratic variant. Of course, in the presence of sufficient institutional bases, democracy and market capitalism are likely to deliver a much more efficient resource allocation than authoritarianism. This is because of the unprecedented self-correcting capacity and the efficiency gains democracy and market capitalism attain through delegating allocative decisions to market participants (von Hayek Citation1945). But these advantages are dependent on the availability of market mechanisms (i.e., institutional bases of horizontal exchange), without which resource allocation is likely to get distorted.

Importantly, institutional bases of horizontal exchange do not only include formal institutions, such as laws and institutionalized decision-making processes. A host of informal institutions, such as democratic values and business morale, are also needed for democracy and market capitalism to prevail. Although quick structural reforms can create incentives for political and economic actors to pursue pro-democracy/ pro-market strategies, informal institutions typically take much longer to develop.Footnote9 Hence, the retreat of horizontal political and economic exchange in new democracies is not at all surprising. One of the most salient contemporary cases of democratic decay is Hungary, to which I turn next.

HOW DOES IT WORK? EXPLAINING THE ORBÁN REGIME

A prime example of current populist governance is Viktor Orbán’s Hungary since 2010. In this section, I present stylized facts about it and come up with an (admittedly sketchy) explanation for its remarkable political success. Whatever one thinks about Orbán, he has won three consecutive elections (in 2010, 2014, and 2018), each time gaining two-thirds of the parliamentary seats. Although conditions were obviously advantageous for him after 2010, as he had already formed a constitutional majority that had the entire political system working for him by the 2014 elections, those were still competitive elections, even if in 2014 and 2018 they were no longer fair. Opposition alternatives existed, and Orbán’s right-wing populist Fidesz party received roughly as many votes as its opponents combined.

Importantly, Fidesz has not been the only right-wing populist party in the Hungarian parliament during this period. Jobbik, an originally radical, although by now somewhat moderated party that is much younger than Fidesz,Footnote10 has also been categorized as right-wing populist in the literature (Bozóki Citation2015; Pirro Citation2014). Yet, the focus of attention here will be on Fidesz and the Orbán regime, as I am primarily interested in what has made right-wing populism a particularly successful governing force, and not so much in its (admittedly important) variants.

To explain Orbán’s success, I elaborate on three factors in particular: (i) the institutional endowments Orbán enjoyed in 2010 and subsequently developed further; (ii) the redistributive policies of the regime, which have played a crucial role in making it popular among a large part of the electorate; and (iii) the issue of corruption and how the regime has handled it. All three are related to each other as well as to the concept of political transaction costs.

Institutional Endowments

Having served as prime minister in 1998–2002, Orbán took over government in 2010 for the second time. As his right-wing populist Fidesz partyFootnote11 took two-thirds of parliamentary seats, he could alter the entire constitutional system without institutional constraints (Tóth Citation2012). A two-thirds majority was relatively easy to win in the individual constituency-based Hungarian electoral system, in which the majority principle has been dominant since 1990. In fact, governing parties attained two-thirds parliamentary majorities both at the 1994 and the 2010 elections, while receiving only 51 and 53 percent of party list votes, respectively. This was no accident: the design of the 1989–1990 democratic political system made sure that effective government was attainable, and fragmentation—or as it was called back then, referring to the example of the interwar German democracy, Weimarization—would not prevent it (Ádám Citation2018).

The founding fathers’ thinking was well-grounded: as structural reforms had alternated with populist economic measures in the late communist period, the social costs of post-communist transformation could easily discredit democratization. Hence, the new constitutional system largely sheltered the government from daily political pressures through institutions like the so-called constructive non-confidence vote, particularly high barriers of entry to the political market stemming from the principal role of individual electoral districts, and a unicameral parliament in which the opposition could not take over before the next elections. As a result, Hungary has seen no snap elections since 1990, and the number of new parliamentary parties remained spectacularly low in the entire 1990–2010 period (Enyedi Citation2016a).

All this can be interpreted as a constitutional effort to keep the bargaining and enforcement costs of democracy relatively low, so that democratic governance could be more effective and deliver positive results more swiftly and persuasively for the electorate. In between elections, the government was entitled to command a particularly strong and dominant vertical power structure with no institutionalized political rival on the scene. There has been no upper house, no directly elected president of the republic, and no strong regional self-governments either. Hence, the role of horizontal political exchange between elections was limited, with particularly rare exchanges between the government and the opposition. At the same time, because a two-thirds majority was attainable, the stakes of political competition were all the higher.Footnote12 Competing parties, in response, became all the more internally centralized and irresponsible in their economic policies. Hence, the institutional endowments that—rather consciously—limited horizontal political exchange among political actors in between elections, contributed to the phenomenon called “populist polarization” by Zsolt Enyedi (Citation2016a).

When Orbán took over with a two-thirds majority in 2010, he did not have to invent a political system based on centrally controlled, hierarchical power structures and vertical political exchange. All he had to do was further centralize the control over political and economic resources. Although the extreme centralization of power he carried out could be seen as going against the underlying idea of direct populist participation and anti-elitism, the rituals of “national consultations,” heavy government propaganda,Footnote13 and the effective monopolization of public space helped sell Orbán’s “paternalist” (Enyedi Citation2016b) or “elitist” (Antal Citation2017) populism. Equally important, though, have been the regime’s redistributive policies, which I discuss next.

Reallocation of Resources

Orbán’s electoral success both in 2014 and 2018 was to a significant extent based on his redistributive policies. His government intensified its economic role, built an extensive business clientele, and heavily reallocated resources from poorer toward richer segments of society. State ownership expanded, and income inequalities grew. While budgetary redistribution stayed as high as it was before 2010, the overall fiscal balance improved, the political cyclicality of budgetary spending eased, and public indebtedness was slowly reduced.

Through effectively balancing the budget, Orbán was able to cut the vicious circle of overspending that was characteristic of the pre-2010 democratic period. To win elections, rival political camps were willing to serve the fiscal needs of all major electoral groups in the democratic period. In meeting electoral needs, however, governments engaged in fiscal overspending that after a while generated a necessity for fiscal stabilization. This was dismissed by the opposition as unjustified budgetary restrictions, and contributed to the build-up of new electoral needs. Hence, a cycle of “electoral demand→ fiscal overspending→ budgetary restrictions→ electoral demand” was created, typical in left-wing Latin American populism (Sachs Citation1989). Orbán cut this, eliminating a major recurring economic policy risk—a move that can be interpreted as a drop in the bargaining and enforcement costs of democracy in a political transaction cost approach.

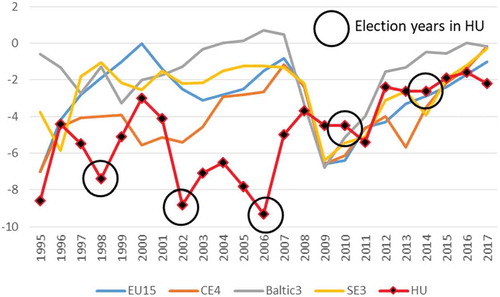

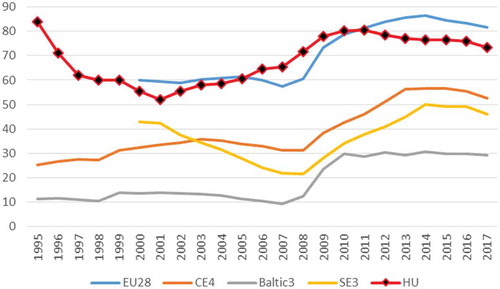

On the other hand, financing government-controlled clienteles generated increasing costs—the political management costs of the regime. This has been mainly financed through the restructuring of budgetary redistribution, but European Union (EU) funds have also been used instrumentally by the regime. While spending on social protection declined, the government spent increasingly on general public services and economic affairs—both being primary vehicles for financing a political and business clientele. In addition, government expenditures on recreation, culture, and religion—a policy area of particular importance in the symbolic reproduction of power—have increased remarkably and risen well above the regional average (see –).

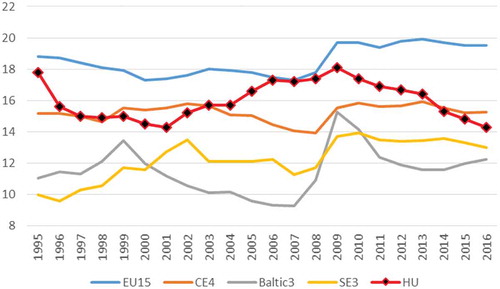

GRAPH 3. General government net lending/borrowing (i.e., the budget balance; in percent of GDP).

Note: EU15: European Union countries excluding Central and Eastern European members states, Cyprus, and Malta. CE4: arithmetic average of data for the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Baltic3: arithmetic average of data for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. SE3: arithmetic average of data for Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. HU: Hungary.Data source: Eurostat

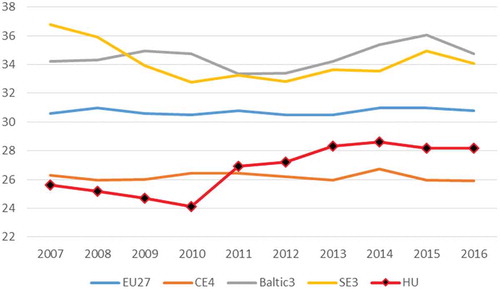

GRAPH 4. Government consolidated gross debt (in percent of GDP).

Note: EU28: All European Union member countries. CE4: arithmetic average of data for the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Baltic3: arithmetic average of data for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. SE3: arithmetic average of data for Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. HU: Hungary. Data source: Eurostat

GRAPH 5. General government spending on social protection (in percent of GDP).

Note: EU15: European Union countries excluding Central and Eastern European member states, Cyprus, and Malta. CE4: arithmetic average of data for the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Baltic3: arithmetic average of data for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. SE3: arithmetic average of data for Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. HU: Hungary. Data source: Eurostat

Orbán’s policies have explicitly favored the middle and upper-middle classes—the backbone of his regime’s support. This has been a manifestly declared policy goal: strengthening an ethno-culturally defined Hungarian middle class that supports national interests embodied in local (as opposed to global or foreign) political initiatives has ranked high in Orbán’s political discourse (Ádám and Bozóki Citation2016). A key instrument of pro–middle class policies has been the flat income tax that Orbán introduced right after taking over in 2010, bringing about a sizeable reduction in the tax burden of average and higher incomes, while increasing taxes on lower incomes. Additionally, generous income-tax holidays after the birth of children lowered the tax burden of middle-class families in particular. Generous housing finance schemes have also been introduced to the benefit of high-income families able to buy or build new houses. Finally, the polarization of state-administered pensions, started in the pre-2010 period, continued as a high replacement ratio and undifferentiated pension hikes made middle-class pensions grow faster than low-income pensions (Ádám and Simonovits Citation2017).

In contrast, lower-income big families did not have enough revenues to claim most of the tax benefits, and typically neither bought nor built new houses. Child benefits, paid after the birth of children regardless of family income, and a prime source of revenue for lower-income big families, stayed unchanged nominally while losing part of their real value, negatively impacting low-income recipients, many of them belonging to the Roma community (Inglot, Szikra, and Raţ Citation2012). In consequence, income inequalities have markedly risen in comparison to the pre-2010 period, although they remain below EU and regional averages (see ).

GRAPH 6. Gini coefficients (scale from 0 to 100, where 0 means absolute equality and 100 means absolute inequality).

Note: The Gini coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of income within a country deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A coefficient of 0 expresses perfect equality where everyone has the same income, while a coefficient of 100 expresses full inequality where only one person has all the income. EU27: European Union countries excluding Croatia. CE4: arithmetic average of data for the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Baltic3: arithmetic average of data for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. SE3: arithmetic average of data for Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. HU: Hungary, Data source: EU-SILC survey (Eurostat)

Some of Orbán’s policies have exhibited a less explicit pro–middle class bias. Utility prices were administratively cut by the government in 2012–2014, significantly boosting Orbán’s popularity and re-election chances in 2014. Cutting utility prices at first sight appears to be a pro-poor measure, and to some extent it has indeed been so. However, middle classes also enjoy lower utility prices, especially those who have large properties. Moreover, the utility price cut was part of Orbán’s scheme of redistributing markets of utility industries: these were privatized in the 1990s for large foreign firms by the then governing Socialists and Liberals, whereas Orbán aimed at renationalizing them after 2010. Cutting utility prices was an incentive for foreign firms to leave the market and relinquish their investments in an increasingly hostile business environment (Ámon and Deák Citation2015).

Orbán has also levied industry-specific taxes on banking, energy provision, telecommunication, and retail trade. Apart from raising additional budgetary revenues, these taxes have served as incentives for large foreign companies either to leave the Hungarian market or to become lenient toward the government, enabling the government to exercise increasingly direct economic control. This policy ambition has also manifested itself through the nationalization of banks and utility companies and in some cases re-privatization to friendly businesses. This was meant to support local capital accumulation and to build a business clientele through the allocation of market shares and preferential government provisions (i.e., through government-allocated rents), often at (or beyond) the edge of legalized corruption (cf. CRCB Citation2016; Fazekas and Tóth Citation2016), to which I return in the next subsection.Footnote14

The government has managed to restructure a number of other economic sectors such as food processing, construction, tourism, and passenger transportation. A controlling share in the market-leader national oil company was acquired, while the government’s controlling role in electricity production and provision was strengthened through nationalized power stations and utility companies. Hence, not only income, but also wealth has been redistributed, and a regime-friendly business clientele was created that has been prepared to finance the government-friendly private media and other politically important social and cultural activities, such as sport clubs, the building of stadiums (through a tax scheme), and politically important civil society organizations. Hence, the role of market competition has been reduced, and the reproduction of economic and political power has been placed under government control.

Logically enough, central government control over local governments has also been increased. Whereas public education and healthcare had been mostly administered by local governments before, central government agencies have taken them over since 2010. Autonomy of public universities has been severed through direct government control over finances. Mandatory private pension funds have been effectively nationalized, with an overwhelming majority of private savings having been transferred to the state-run pay-as-you-go pension system. A large-scale restructuring of the media sector has taken place, with government- friendly businesses playing an increasingly dominant role. Public media outlets have turned into government propaganda vehicles. Public administration has become directly and politically controlled by the government, and a growing influence over the judicial system has been exercised.

Another politically important policy measure has been the expansion of public work programs, in which hundreds of thousands of people have been employed who otherwise would have mostly stayed economically inactive. They earn miserable wages but enjoy some degree of income stability. To make the program more attractive, social benefits of the long-term unemployed and inactive were cut, and some of them were made dependent on participation in public work programs.

Public work programs have seldom made people more competitive on the primary labor market. Instead, participants often get stuck in these programs (Cseres-Gergely and Molnár Citation2015), making them dependent on government policies and, in particular, local authorities, who directly employ them in most public work schemes. Especially in villages and small towns, this can contribute to the re-feudalization of power relations and the strengthening of local political elites (Kertesi and Kézdi Citation2011).

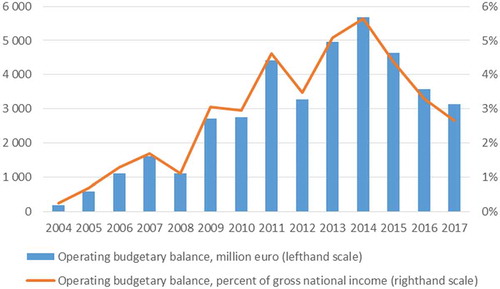

Hence, in all measures, the Orbán regime has hugely expanded the role of government-controlled clienteles. As I have stressed, clienteles have to be continuously refinanced so that they can operate as effective top-down political leverage. In resource-rich countries, such as Russia and mineral-rich African states, apart from budgetary redistribution, this is typically based on extraction of natural resources. In the case of the Orbán regime—in the absence of mineral resources—the allocation of government-controlled EU funds played a similar role, in some years approximating (or even surpassing) 5 percent of gross national income (see ).Footnote15

GRAPH 7. The balance of budgetary transfers between Hungary and the EU.

Data source: European Commission, DG Budget (http://ec.europa.eu/budget/figures/interactive/index_en.cfm)

EU funds are ideal for populist purposes as, within certain limits, the government has considerable discretion in allocating them among their clientele. Although cases of obvious corruption have been found by EU authorities, the worst that happened was that the government had to repay some funds to Brussels.Footnote16 (I return to the issue of EU funds-related corruption in the next subsection.)

Generous government provisions (to a significant extent based on EU sources), rising real wages, and an improving European business cycle have made Hungarians increasingly optimistic. Since 2013, both business and consumer sentiment indices have been improving markedly. Admittedly, an improving consumer confidence index has not been a guarantee for incumbent electoral victory in past decades. In the particular case of the post-2010 period, however, the reference period was the pre-2010 economic collapse and the concomitant fiscal stabilization, which made Orbán’s case particularly powerful.

In sum, market coordination has, in a number of ways, been sidelined since 2010, and government interference has become increasingly robust. The role of government-controlled clienteles has expanded in a number of economic sectors. Budgetary revenues and expenditures have been restructured with an explicit aim of serving the middle and upper-middle classes. Generous EU funding has contributed to the financing of clienteles, while an upturn in the European business cycle delivered a positive domestic economic effect. This has been a period characterized by improving fiscal and external accounts, low inflation, increasing employment, and rising business and consumer sentiment indices. The government took an increasingly active role in economic life, built clienteles, and reduced pro-poor redistribution. This set of state-centered, pro–middle class policies generated considerable political support in 2010–2018. One major issue, however, ha been casting a shadow over government policies during the entire period: corruption. I discuss that next.

Corruption

The link between populism and corruption has been extensively researched. The typical relationship observed is a causality running from corruption toward populism: by mobilizing against “corrupt elites,” populists gain votes as representatives of “honest and honorable people.” Hence, moral purity and an anti-corruption push are trademark populist selling points, and low-credibility democratic institutions and traditional political elites make this a particularly promising venture (Chacko Citation2018; Rohac, Kumar, and Heinö Citation2017). However, populists themselves can, of course, be corrupt—a highly relevant option if one is to analyze the Orbán regime.

As market competition is increasingly sidelined in populist regimes, loyalty to the ruling political elite and membership in government-controlled clienteles become the criteria of economic success. Although such a practice obviously goes against meritocratic standards, people and businesses go along because of a lack of viable alternatives, their individual interests, or a mix of the two. Well-functioning populist regimes can bring about straightforward systems of rent-creation, in which economic and political rents continuously reproduce each other. In fact, from an individual point of view, such a system may provide efficiency gains to competitive democracy and market capitalism. When only one elite group has an effective chance for holding power, there is a lesser risk of resources being spent on support for losing candidates. Moreover, acts of corruption are significantly less likely to be prosecuted by law-enforcement agencies and revealed by a free press. Hence, individual persons and businesses can in fact confront lower political bargaining costs of lobbying (whether through legal or illegal means) than in democracies.Footnote17 Hence, once they have become part of the clientele, people and businesses are also interested in maintaining the regime.

However, from an aggregate social point of view, a regime of institutionalized corruption is suboptimal, as it transforms public resources into private income in a non-transparent and undue way. The corruption surcharge clientele members are allowed to appropriate when obtaining overpriced public procurement commissions and government-allocated market shares is the social cost of political rent-creation. The advantage of democracy is the elimination of such rents through political and—politically institutionalized—economic competition. Hence, democracy in theory is able to select out political mechanisms that favor private utilities over public well-being.

However, as I have already shown, democracy and market capitalism are not always available institutionally, as formal and informal political institutions may not be able to sustain the dominance of horizontal exchange. In this context, corruption is only an extreme form of vertical integration of political and economic exchange: a morally unjustified—and in some cases legally banned—version of politically controlled rent allocation.

Apart from giving strong incentives for participating in government-controlled clienteles, the Orbán regime has also institutionalized corruption through dismantling the institutional safeguards against it. Both mass media and law-enforcement agencies have been placed under direct political control since 2010. Most independent media organizations have been strangled financially, with the notable exceptions of RTL Klub, Hungary’s most popular TV channel, and index.hu, the most popular on-line news site. Meanwhile, national broadcast media outlets have become either directly or indirectly government-controlled. Public radio and television channels have been placed under direct government control, and most private channels have been aligned with the government by friendly businesses. The remaining few independent publishers and broadcasters have been threatened with punishing taxes and the withdrawal of licenses, so that political leverage can be exercised over them.Footnote18

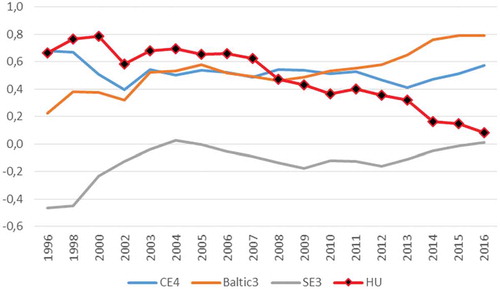

The police and the public prosecution service have also become politically controlled, with officials expected to place political loyalty above moral and professional standards. Most accusations of government officials and cronies are simply not investigated, as the prosecution service dismisses such cases as groundless. Although the judicial system is still relatively independent from the government, efforts to make judges politically complicit have been made and are expected to continue after Orbán’s third-in-a-row two-thirds victory in 2018. Hence, although the Orbán regime has been perceived to be increasingly corrupt (see ), institutional bases for fighting corruption have been largely abolished.Footnote19

GRAPH 8. World governance indicators—control of corruption estimates.

Note: Estimate of governance ranges from approximately −2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong) governance performance. CE4: arithmetic average of data for the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Baltic3: arithmetic average of data for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. SE3: arithmetic average of data for Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania. HU: Hungary. Data source: World Bank World Governance Indicators dataset (http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home)

In light of empirical data, it is not simply that perceptions have deteriorated: corrupt practices—partly legalized by the regime—have also expanded. Analyses presented by the Corruption Research Center Budapest (CRCB—an independent think tank focusing on corruption research primarily based on public procurement data) and Transparency International Hungary both suggest growing government cronyism and increasing corruption risks, particularly with respect to public procurement and government-controlled EU development funding (Martin Citation2017; Martin and Ligeti Citation2017; Tóth and Hajdu Citation2018). An amendment to the public procurement law in 2010 has made government discretion wider in public procurement decisions, and EU-funded public procurement tenders—typically financing large infrastructure projects and other highly capital-intensive developments—have been particularly exposed to high corruption risks (CRCB Citation2016). Interestingly enough, all this has exercised a limited impact on the government’s public standing.

There is a collective political process one should mention in this context that helps populists get away with corruption: the polarization of the electorate. As populist parties are leader-dominated, and populists in power—as I argued above—act as modern-day charismatic rulers, they tend to enjoy a personality cult that would be hard to reconcile with a perception of personal corruption. Voters, in consequence, have to decide whether they believe in the purity or in the greed of populists, with little room in-between. The result is a polarizing electorate and a shrinking public space devoted to rational political debate (Curini Citation2018; Pappas and Aslanidis Citation2015).

This is precisely what has happened in Hungary since the early 2000s, when Orbán started behaving as a populist and segmenting the electorate into “them” and “us.” To be fair, Manichean worldviews referring to good and bad policies based on good and bad intentions and personalities of politicians with little tolerance for dissent had been present in Hungary since at least the early 1990s—and in some sense much earlier.Footnote20 By the mid-2000s, Hungarian politics had been dominated by a non-reconcilable conflict of the left and the right, in which one’s hero was inevitably a villain for the other party, with the electorate increasingly internalizing the divide (Karácsony Citation2006; Körösényi Citation2012).Footnote21 Against this context, the “corrupt practices of the left,” through which the pro-west, pro-EU left-wing government “sold out the country” to “alien interests,” committing not simple corruption but a “political crime against the nation,” became a major right-wing political theme.Footnote22

*

In sum, the Orbán regime centralized political and economic power and made individual economic success dependent on political loyalty. Bargaining, enforcement, and information costs of democracy have been partly eliminated, and replaced by management costs of operating government-controlled clienteles. Within this latter type of political transaction costs, the social costs of rising corruption play a prominent role. Although perceptions of corruption have deteriorated over time, both the structure of private incentives and the weakening institutional bases of the anti-corruption cause have so far sheltered the regime from any major backlash. The polarization of political discourse, and subsequently the entire electorate, also helped Orbán to get away with large-scale, institutionalized corruption. Hence, political exchange has been increasingly restructured in a vertical way, with the government exercising virtually unlimited power over resource allocation, the mass media, and law enforcement. Although the legitimizing role of horizontal exchange has been maintained—elections have been held at regular intervals—it has been placed under firm government control. In short, Viktor Orbán’s authoritarian populist regime has matured.

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, I proposed a political transaction cost theory of populism. I argued that authoritarian populism is an equilibrium solution to the problem of political coordination in institutionally underdeveloped democracies. It does not eliminate democratic choice, but conditions it on vertically organized, hierarchical power structures, controlled by incumbents. The literature on populism appears to have difficulties with addressing the problem of non-democratic behavior by populist governments. After all, if populists get elected popularly, how could they be non-democratic? My answer—following Müller (Citation2016), Pappas (Citation2016), and Finchelstein (Citation2014)—is that authoritarian populists are democratically elected but not democrats: they represent an anti-institutionalist push that seeks to remove the system of checks and balances without which democracy cannot prevail.

To be sure, populism is not necessarily an evil political project, although if it wins majority support, it is likely to further weaken democracy and market capitalism. Yet, in polities characterized by weak—or weakening—democratic institutions, populist rule might be an equilibrium solution between democracy and outright dictatorship. To explain how populist regimes work, I extended the notion of political transaction costs introduced in Zankina (Citation2016) and Gurov and Zankina (Citation2013). My point of departure was that, similarly to economic exchanges, political exchanges—transactions over political power, including elections, legislation, and execution of government policies—have transaction costs as well. Furthermore, as political systems are characterized by different types of political exchanges, the structure of political transaction costs differs across them as well. Using Oliver Williamson’s (Citation1973) “markets versus hierarchies” dichotomy, I have delineated horizontal versus vertical political exchange and attendant transaction costs. In this approach, democracy can prevail as long as the political institutions supporting horizontal political exchange keep market-type political transaction costs—primarily bargaining, enforcement, and information costs—sufficiently low. This is obviously not always the case, and one way to deal with insufficient democratic institutional performance is populism—an authoritarian approach to power constrained by mechanisms of majoritarian democracy.

The appeal of majoritarianism results from its democratic credentials: after all, it is hard to call a political regime that relies on the electoral support of the majority of people a non-democracy. However, populist regimes indeed become increasingly non-democratic once they disable the system of checks and balances that constrain democratic governance and make possible the peaceful change of power.Footnote23 This is what cross-country data on populist governance suggest, as well as what we know about most individual populist regimes, including Viktor Orbán’s Hungary.

Thanks to the majoritarian institutional characteristic of Hungarian democracy laid down at the 1989–1990 democratic regime change, Orbán in 2010 could transform his simple electoral majority into the two-thirds of parliamentary seats by which he has been able to exercise virtually unlimited power ever since. As the post-1990 Hungarian democracy had always contained significant majoritarian elements to secure a stable parliamentary majority and to ensure an institutionally unchallenged role of the government, Orbán’s shift toward authoritarian populism was not shocking news for many Hungarians. On the contrary, through extensive clientele building, distorted elections, and skillfully engineered redistributive policies, Orbán was able to keep a sufficient part of the electorate on board to attain two more two-thirds victories at elections in 2014 and 2018.

With no effective checks and balances remaining in place, Orbán’s rule—as could be expected—has been associated with rising corruption that, quite remarkably, has not undermined his power. In the political transaction cost approach I proposed, this could be interpreted as indicating that a rise in political management costs—the actual efficiency loss from corruption at an aggregate level—has not been exceeding the measure of transaction cost reduction resulting from the vertical integration of political exchange. The latter primarily meant a cut in the bargaining, enforcement, and information costs that can become excessively high in institutionally underperforming democracies, as was the case in pre-2010 Hungary, where electoral victories required budgetary overspending and considerable public resources spent on financing rival political clienteles. In contrast, Orbán concentrated power over clienteles, strengthened the financial positions of the middle and upper-middle classes, and mostly eliminated cyclically recurrent fiscal stabilization needs.

Yet, in the absence of institutional mechanisms to address the growing costs of corruption, the political management costs of the regime are bound to rise in the future. As opposed to the current situation, where generous development funding from the EU provides windfall revenues to the regime, EU funding is likely to decrease in the next EU budget programming period from 2021. Other factors, such as the upturn in the European business cycle and the high demand for Hungarian labor in EU markets, may also change in the coming years. In consequence, there might be less money to finance government-controlled clienteles, while economic sentiments may start deteriorating at some time in the future.

Most likely, there will be a point in time when Hungary re-introduces democratic oversight to reduce the costs of vertical political exchange. When and how this will happen, we do not know. Populism, however, will stay with us in Hungary, as well as in other parts of the world, because mass democracies—still a relatively new form of governance in human history—will from time to time experience institutional weaknesses in the face of major structural changes of the world economy and demographics. This is likely to maintain a recurring pattern of crisis of horizontal political exchange that will be responded to with shifts toward some sort of vertical integration of power. Authoritarian populism, given its dubious yet existing democratic credentials, is likely to stay in the race for this job.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Versions of this paper were presented at the Fourth Prague Populism Conference at Charles University, Czech Republic, in May 2018, and at the “Transforming the Transformation?” conference at the Fraunhofer IMW in Leipzig, Germany in November 2018. I am grateful for questions and comments by conference participants as well as by the anonymous reviewers.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Viktor Orbán’s Hungary is an authoritarian populist regime, or to use the term of Levitsky and Way (Citation2010), a competitive authoritarian regime (I return to Levitsky and Way in note 12). Elections are not fair, but there is an actual opposition participating in them. In contrast, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, for example, where the actual opposition is barred from elections, is an outright dictatorship.

2. Direct, non-institutionalized links include leader-dominated political movements and parties, referenda, and other forms of direct political participation. For example, in Venezuela, Hugo Chavez held multi-hour-long public hearings broadcasted nationally (Ellner Citation2012).

3. Juan Peron was president of Argentina in 1946–1955 and again in 1973–1974.

4. The Czech Republic’s ruling ANO party is a member of ALDE (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe), and hence is often called “centrist populist.”

5. Anthony Downs (Citation1957) elaborates on the role of asymmetric information in democracy, with respect to lobbying (persuasion of decision-makers) and representation (collecting and disseminating information both in a top-down and a bottom-up sense) as well as rational ignorance by voters (ignorance of the detailed political programs of political parties).

6. Furubotn and Richter (Citation2005, 55–57) considers the costs of setting up and maintaining social and political organizations such as political parties and state bureaucracies as political transaction costs. Yet, in political science, very few authors use the notion of political transaction costs, notable exceptions being Gurov and Zankina (Citation2013) and Zankina (Citation2016).

7. The difference between horizontal and vertical exchange here, as in transaction cost economics, refers to whether or not an element of authority is present within the exchange relation. Horizontal exchange occurs when parties to the transaction are legally equal and hierarchically non-subordinated to each other (as in competitive markets). Vertical exchange takes place within hierarchies, such as firms and other hierarchical organizations, including governments. Hence, the notions of horizontal and vertical exchange here are conceptually unrelated to the terms of horizontal and vertical accountability in political science.

8. Hence, populist regimes in my approach are conceptually similar to competitive authoritarian regimes in the sense of Levitsky and Way (Citation2010). As they argued, these regimes “were competitive in that opposition forces used democratic institutions to contest vigorously—and, on occasion, successfully—for power. Nevertheless, they were not democratic. Electoral manipulation, unfair media access, abuse of state resources, and varying degrees of harassment and violence skewed the playing field in favor of incumbents. In other words, competition was real but unfair” (3). This characterization seamlessly fits most populist regimes, including Viktor Orbán’s Hungary that I discuss below. In this case, although physical violence against the opposition is rare, harassment is common. For a recent paper treating contemporary Hungary as a hybrid regime, see Bozóki and Hegedűs (Citation2018).

9. Douglass North famously referred to the potential mismatch between formal and informal institutions. In his 1993 Nobel lecture, he asserted with reference to the process of post-communist transition that privatization could be done overnight, but the set of informal institutions within which private property and other core capitalist institution are placed was much harder to create (North Citation1994).

10. Fidesz was established in 1988 as the first non-communist political party before the 1989–1990 regime change. Jobbik was established in 2003.

11. Fidesz has an interesting history that has to a great extent determined the fate of post-1990 Hungarian democracy. Initially a movement of young liberal intelligentsia, Fidesz first turned into a conservative-liberal party in the mid-1990s and has gradually radicalized ever since, so much so that Orbán has been labeled the leader of the European radical right by Cas Mudde (see “Orbán a radikális jobboldal vezére Európában” [Orbán is the Leader of the Radical Right in Europe], Index, June 13, 2018, https://index.hu/belfold/2018/06/13/orban_a_radikalis_jobboldal_vezere_europaban/ [in Hungarian]). The radical turn of Fidesz and the concomitant demise of Hungarian democracy appear to support Daniel Ziblatt’s (Citation2017) thesis on the role of conservative parties in creating and maintaining democracy, and the danger of their weakness in giving in to radicalization.

12. “We need to win only once but with a big margin,” said Orbán famously in 2007, after having lost two national elections in a row in 2002 and 2006 (see “Orbán Viktor nemzeti katarzist akar” [Viktor Orbán Wants a National Catharsis], Index, July 21, 2007, http://index.hu/belfold/ovibal0721/ [in Hungarian]).

13. Political preferences have been heavily manipulated through government propaganda. Mass campaigns have been waged with particularly aggressive anti-EU, anti-immigrant/anti-refugee, and anti-Soros emphases.

14. Another form of providing government-secured rents for friendly businesses was the creation of local tobacco retail monopolies that were typically allocated to Fidesz-friendly local businesses.

15. On the political economy of EU fund allocation in a comparative regional perspective, see Gergő Medve-Bálint (Citation2017, Citation2018).

16. On the corrupt allocation of government-controlled EU funds, see Transparency International Hungary’s report “Corruption Risks of EU Funds” (https://transparency.hu/en/kozszektor/kozbeszerzes/eu-s-forrasok-vedelme/unios-forrasok-korrupcios-kockazata/) as well as CRCB (Citation2016). For a story on the EU’s anticorruption body investigating the allocation of EU funds in Hungary, see Benjamin Novak, “OLAF says Hungary Should Repay $51 Million in EU Funds Paid to Prime Minister Son-in-Law’s Company” (Budapest Beacon, February 12, 2018; https://budapestbeacon.com/olaf-says-hungary-should-repay-51-million-in-eu-funds-paid-to-prime-minister-son-in-laws-company/).

17. I am grateful to József Péter Martin for this insight.

18. In Freedom House’s Freedom of the Press 2017 report, Hungarian press freedom was ranked the 85th–86th in the world, alongside Greece, out of 199 countries. This was the worst performance in the EU. See https://freedomhouse.org/report-types/freedom-press.

19. Prosecuting Viktor Orbán or any of his political and business associates is practically out of the question in an era of politically controlled prosecution service and police. Meanwhile, the Hungarian government has been opposed to the idea of creating a European Public Prosecutor’s Office. See Ministry of Justice: “Hungary Continues to Say No to Joining European Public Prosecutor’s Office,” June 5, 2018, http://www.kormany.hu/en/ministry-of-justice/news/hungary-continues-to-say-no-to-joining-european-public-prosecutor-s-office.

20. Historical roots of extreme elite polarization go back to the so-called populist–urbanite debate—a kind of Hungarian Narodnik–Zapadnik divide—on the ideal way of modernization in the 1930–1940s. This divide reappeared in a highly politicized way in the 1990s with apparent references to the so-called Jewish question concerning the role of Jewish intelligentsia and business owners in modernization and nation building (cf. Gyurgyák Citation2001; Kovács Citation1994; Laczó Citation2013).

21. The problem of extreme political polarization is not a uniquely Hungarian characteristic. For a more general discussion with particular reference to current U.S. politics, see Levitsky and Ziblatt (Citation2018).

22. A case of symbolic importance was the so-called King’s City project that was to build a giant casino and surrounding facilities in Sukoró, Center-West Hungary, by 2011. The would-be investors were prominent American Jewish businessmen, including Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress. The project had been supported by the left-wing government from 2007 to 2009, but was officially canceled in 2009. Government officials, including Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, were prosecuted following accusations of financial wrongdoing made by an opposition politician. Although charges against Gyurcsány were eventually dropped in 2012, other leading government officials were tried and some of them convicted, with two former leaders of the state asset-management company being incarcerated at the time of writing this article. This case, involving “Jewish money” and the personal participation of Gyurcsány, was ideal for criminalizing left-wing politics and the pro-west, pro-EU political elite.

23. For an alternative interpretation of the role of checks and balances, see Albertus and Menaldo (Citation2018), who consider institutional constraints on democratic governance as means of retaining power for traditional elites after democratization.

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2000. “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise? Democracy, Inequality, and Growth in Historical Perspective.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, November. 115:1167–99. doi:10.1162/003355300555042.

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Ádám, Zoltán. 2018. “What Not to Do in Transition: Institutional Roots of Authoritarian Populism—The Hungarian Case.” Paper presented at The 3rd International Economic Forum on Reform, Transition and Growth, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia.

- Ádám, Zoltán, and András Bozóki. 2016. “State and Faith: Right-Wing Populism and Nationalized Religion in Hungary.” Intersections 2 (1):98–122.

- Ádám, Zoltán, and András Simonovits. 2017. “From Democratic to Authoritarian Populism: Compariang Pre- and Post-2010 Hungarian Pension Policies.” Discussion papers MT-DP – 2017/31, Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest.

- Albertus, Michael, and Victor Menaldo. 2018. Authoritarianism and the Elite Origins of Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ámon, Ada, and András Deák. 2015. “Hungary and Russia in Economic Terms – Love, Business, Both or Neither?” In Diverging Voices, Converging Policies: The Visegrad States’ Reactions to the Russia-Ukraine Conflict, edited by Jacek Kucharczyk and Grigorij Meseznikov, 83–99. Warsaw: Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

- Antal, Attila. 2017. “The Political Theories, Preconditions and Dangers of the Governing Populism in Hungary.” Czech Journal of Political Science/Politologicky Casopis 24 (1):5–20. doi:10.5817/PC2017-1-5.

- Barro, Robert J. 1997. Determinants of Economic Growth. A Cross-Country Empirical Study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boyraz, Cemil. May, 2018. “Neoliberal Populism and Governmentality in Turkey.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 44 (4):437–52. doi:10.1177/0191453718755205.

- Bozóki, András. 2015. “The Illusion of Inclusion: Configurations of Populism in Hungary.” In Thinking through Transition: Liberal Democracy, Authoritarian Pasts, and Intellectual History in East Central Europe after 1989, edited by Michal Kopecek and Piotr Wcislik, 275–312. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Bozóki, András, and Dániel Hegedűs. 2018. “An Externally Constrained Hybrid Regime: Hungary in the European Union.” Democratization 25 (7):1173–89. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1455664.

- Chacko, Priya. 2018. “The Right Turn in India: Authoritarianism, Populism and Neoliberalisation.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (4):541–65. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1446546.

- Coase, Ronald H. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica, New Series 4 (16):386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x.

- CRCB. 2016. Competitive Intensity and Corruption Risks. Statistical Analysis of Hungarian Public Procurement – 2009-2015. Main Findings & Descriptive Statistics. Budapest, Hungary: Corruption Research Center Budapest.

- Cseres-Gergely, Zsombor, and György Molnár. 2015. “Labor Market Situation following Exit from Public Works.” In The Hungarian Labor Market 2015, edited by Károly Fazekas and Júlia Varga, 148–59. Budapest: Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Curini, Luigi. 2018. Corruption, Ideology, and Populism. The Rise of Valence Political Campaigning. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- de la Torre, Carlos. 2016. “Left-Wing Populism: Inclusion and Authoritarianism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador.” The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 23 (1):61–76. http://bjwa.brown.edu/23-1/left-wing-populism-inclusion-and-authoritarianism-in-venezuela-bolivia-and-ecuador/

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

- Ellner, Steve. 2012. “The Heyday of Radical Populism in Venezuela and Its Reappearance.” In Populism in Latin America, edited by M. L. Connif, Vol. 2012, 132–58. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2015. “Plebeians, Citoyens and Aristocrats or Where is the Bottom of Bottom-up? the Case of Hungary.” In European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession, edited by Hanspeter Kriesi and Takis Pappas, 242–57. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2016a. “Populist Polarization and Party System Institutionalization. The Role of Party Politics in De-Democratization.” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (4):210–20. doi:10.1080/10758216.2015.1113883.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2016b. “Paternalist Populism and Illiberal Elitism in Central Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies 21 (1):9–25. doi:10.1080/13569317.2016.1105402.

- Fazekas, Mihály, and István János Tóth. 2016. “From Corruption to State Capture. A New Analytical Framework with Empirical Applications from Hungary.” Political Research Quarterly 69 (2). doi:10.1177/1065912916639137.

- Finchelstein, Federico. 2014. “Returning Populism to History.” Constellations 21 (4):467–82. doi:10.1111/cons.2014.21.issue-4.

- Furubotn, Eirik G., and Rudolf Richter. 2005. Institutions and Economic Theory. The Contribution of the New Institutional Economics. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Gumede, William M. April, 2008. “Briefing: South Africa: Jacob Zuma and the Difficulties of Consolidating South Africa’s Democracy.” African Affairs 107 (427):261–71. doi:10.1093/afraf/adn018.

- Gurov, Boris, and Emilia Zankina. 2013. “Populism and the Construction of Political Charisma: Post-transition Politics in Bulgaria.” Problems of Post Communism 60 (1):3–17. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600101.

- Gyurgyák, János. 2001. A Zsidókérdés Magyarországon [The Jewish Question in Hungary]. Budapest: Osiris.

- Hadiz, Vedi R. 2014. “A New Islamic Populism and the Contradictions of Development.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 44 (1):125–43. doi:10.1080/00472336.2013.832790.

- Hámori, Balázs, and Katalin Szabó. 2016. “Reinventing Innovation.” In Constraints and Driving Forces in Economic Systems: Studies in Honour of János Kornai, edited by Balázs Hámori and Miklós Rosta, 51–76. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Heyderian, Richard Javad. 2018. The Rise of Duterte. A Populist Revolt against Elite Democracy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2017. “Trump and the Populist Authoritarian Parties: The Silent Revolution in Reverse.” Perspectives on Politics 15 (2):443–54. doi:10.1017/S1537592717000111.

- Inglot, Tomasz, Dorottya Szikra, and Cristina Raţ. 2012. “Reforming Post-Communist Welfare States.” Problems of Post-Communism 59 (6):27–49. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216590603.