ABSTRACT

After the end of the USSR, the mobility infrastructure in Tajikistan followed a trajectory of decay. Transport systems had to be reorganized, mobility practices had to be reshaped, and some areas became less accessible. Meanwhile, new international connections have emerged thanks to new political openness. Based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2014 and 2022, this paper offers an empirical analysis of the nexus between remoteness and connectivity by looking at the evolution of physical infrastructure in Tajikistan’s VMKB province over the past thirty years and discussing the rather contradictory yet simultaneous processes of internationalization and marginalization.

Introduction

In most former Soviet republics, since the end of the USSR, infrastructure provided by the administrative center has followed a trajectory of decay and neglect. Some roads have been poorly maintained and transport systems have had to be reorganized. As a result, mobility practices have had to be reshaped and some regions have become less accessible. At the same time, the collapse of the USSR has brought a complete redesigning of borders, new openings, and the emergence of unprecedented international connections. In Tajikistan’s Pamirs, a high mountain region, remoteness and connectivity have moved in different directions over the last thirty years, illustrating an often paradoxical relationship between more remoteness and more connectivity. That is what this paper explores.

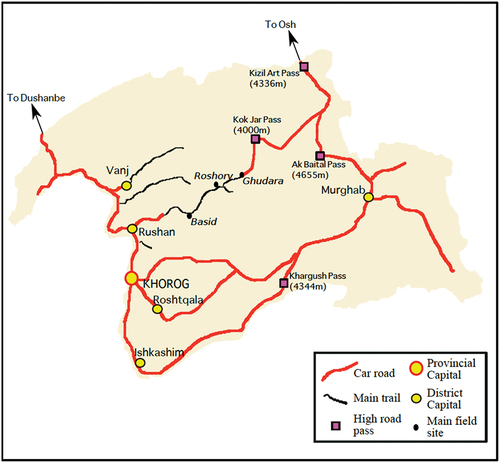

Tajikistan’s Pamirs refers to one of the country’s four provinces; it covers approximately 45 percent of the national territory. Officially known in Tajik as the Veloyat-i Mukhtori Kuheston-i Badakhshon (VMKB), meaning Autonomous Mountainous Province of Badakhshan (Russian: Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast [GBAO]), the region is indeed mainly shielded by the Pamir mountain range, which shapes a challenging topography. To the east, the province shares a 470-km-long border with the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China; to the north, a115-km border with the Osh region in Kyrgyzstan; and to the south, the province of Badakhshan in Afghanistan, with approximately 1,400 km of common border. On that southern flank, the Wakhan corridor separates Tajikistan from Pakistan by a narrow 15–65-km-wide strip (Olimova et al. Citation2006, 6).

The VMKB still qualifies as a geographically isolated province within a landlocked country, even though it has three international borders allowing it to reach global markets. Starting in the 1930s until 1991, the borders with China and Afghanistan were completely closed by the Soviet authorities in an effort to limit foreign influence. For over seven decades, the VMKB was thus entirely supplied by Moscow, where plans to physically support the development of the province were implemented to better connect it with the rest of the USSR. With the independence of Tajikistan, the province stopped being provisioned by an administrative center, but new opportunities emerged to allow for contacts with neighboring countries.

In this paper, we offer an analysis of the nexus between remoteness and connectivity by looking at the evolution of physical infrastructure in the VMKB over the past thirty years. This requires us to consider both the local scale, that of individuals impacted by the changes implied after the end of the Soviet system, and the regional level with the opening of Tajikistan’s international borders in 1991. Based on ethnographic methods and fieldwork missions conducted between 2014 and 2022, our aim is to show how the province has been influenced by the ending of a large and centralized system, which brought it back to a certain remoteness, while also showing that it has benefited from efforts to link up with globalization processes. Nonetheless, this new international opening gained over the last three decades has not spared the VMKB from various crises affecting both remoteness and connectivity.

In the first section, we provide the historical context of physical accessibility in Tajikistan’s Pamirs from Soviet times to today, to show that isolation from outside the USSR went hand in hand with increased connections within the Union. In the second section, we present new actors and initiatives that have been supporting the international connectivity of the VMKB since the beginning of the 2000s, thus introducing the province to globalized dynamics. In the last section, we focus on the internal and external factors that challenge accessibility and put into question the future of remoteness and connectivity; we therefore discuss the unstable nature of both processes.

The Problematic Physical Accessibility of the VMKB: From Soviet Integration to Internal Marginalization

The first part of this paper will give some historical background on the physical accessibility of the VMKB. Our aim is to show how the region has moved from an integrated periphery during the Soviet times to a more marginalized one after Tajikistan gained independence in 1991. While the Soviet administration attempted to connect even the most remote valleys to the centralized system through provisioning and transportation, the independent Tajikistani state has not made physical accessibility of the province a top priority. Three decades after the collapse of the USSR, there is no public transportion to or within the province, and portions of the VMKB’s roads are decaying.

The Soviet Era: Construction of Roads and Implementation of a Large-scale Provisioning System

Before the arrival of the RussiansFootnote1 in the region and before the construction of roads for cars, the physical accessibility of Badakhshan was spectacularly low, and journeys to access the region were epic (see Bliss Citation2006). The adventurous stories of travelers in the region vividly depict problematic journeys along the owringi (“foot paths leading along the slopes and cliffs” [Bliss Citation2006, 184]) and of crossing fast-flowing rivers on precarious bridges or with traditional flotation devices made of inflated animal skins. Although Pavel Louktniski praised the Soviet Union’s accomplishments in a very partisan way, we can concede that some of his descriptions might reflect the reality of the time: “The absence of roads was one of Tajikistan’s plagues. Until the October Revolution, there was not a kilometer of road in Eastern Bukharia” (Louktniski Citation1954, 31).Footnote2

The penetration of the Soviet system into the region greatly changed its accessibility. During the Soviet era, Gorno-BadakhshanFootnote3 became much more physically accessible. The Soviets established an air connection to the Pamirs even before roads were built. The first plane arrived in the region in 1929 and a proper airport was built in Khorog in 1932 (Remtilla Citation2012, 53). The Russians, and later the Soviets, also started the construction of roads to the region in order to reduce its marginalization and to establish their administrative powers. The creation of the M41 Highway reinforced the penetration of the Soviet system in the region. The M41, often referred to as the Pamir Highway (and previously known as “the great Stalin road” [Louknitski Citation1954, 224]), links Dushanbe,Footnote4 the capital of Tajikistan, to Osh, the second most populated city in Kyrgyzstan. In the Pamirs, the highway traverses Khorog, the administrative center of the VMKB, and the town of Murghab. The Osh–Khorog section opened in May 1935 after a bit more than a year of work (Kreutzmann Citation2015, 119). When the M41 opened, the Akbaital Pass (4 655 m) was “the highest pass ever crossed by a motorable road” (Kreutzmann Citation2015, 117). Till Mostowlansky explains the importance of the event: “Only when parts of the Pamir Highway were finally opened in 1933, after several years of frustration, did Gorno-Badakhshan [VMKB] finally overcome its role as a ‘deserted’ and ‘inaccessible periphery,’ as seen from a Soviet perspective” (Mostowlansky Citation2017a, 40). The Dushanbe–Khorog section, which is situated on a lower but steeper terrain, was completed later. The New York Times announced that “Soviet Opens Mountain Road” (New York Times, September 12, Citation1940), which underlines how noteworthy the construction was at that time. The Soviets urgently needed to establish the accessibility of the region for security and surveillance purposes. In 1939, the M41 was extended south of Khorog to the town of Ishkashim, an important strategic point for surveillance of the Afghan border, where a military camp was built (Kreutzmann Citation2015, 119; see ). Murghab (named Pamirskii Post during the Soviet era), approximately 300 km north of Ishakshim, was the Soviet military post of the eastern Pamirs for surveillance of the borders with China and Afghanistan. Ever since its construction, the M41 has been the main artery of the region. It enabled the first motorized vehicles in the region, the implementation of the Soviet provisioning system, and the arrival of large numbers of workers from all parts of the USSR.

Figure 1. Car roads in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast in 1986. From the Russian “Tourist Map” of 1986 (F.G. Patrunov, Po Tadzhikistanu, Profizdat, Moscow, 1987). Thanks to Markus Hauser, the Pamir Archive, http://www.mountaincartography.org/publications/papers/papers_nuria_04/hauser.pdf. © Suzy Blondin (Citation2021).

Once roads were completed in the province, but especially after the 1960s, the Moscow provisioning system or moskovskoe obespechenie, controlled and organized from Moscow, was implemented. Mostowlansky explains (Mostowlansky Citation2017a, 42) that this system provided the Pamiris with more “access to high-quality consumer goods, educational opportunities, and higher salaries and pensions” than many other areas of the USSR, in an effort to make inhabitants of peripheral areas feel included in the Union (see also Saxer Citation2019). As Frank Bliss details in his monograph, electricity was well provided for and cultural events were numerous, and even “cinemas were […] to be found in middle-sized villages” (Citation2006, 5). In the remote villages of the Bartang Valley, our older interlocutors have told us about helicopters delivering food, medicines, and different kinds of items to their villages, with pilots sometimes offering some villagers a flight to Khorog or Dushanbe on their way back. Helicopters would also come in case of an environmental disaster or health emergency. Other parts of the Pamirs, and especially the regions that shared a border with Afghanistan, enjoyed particular privileges since the region was considered a “display window” of Soviet communism for neighboring Afghan populations (Bliss Citation2006, 247). Although roads restructured the entire region, populations living at a distance from them remained marginalized. With the absence of roads, travel times were much longer and conditions much harsher, but the Soviet system promoted mobility by encouraging university studies, providing work in different parts of the Union (see Sahadeo Citation2019), and offering the GBAO [VMKB] a better connection with the rest of the Tajik Republic—and the USSR in general—through the implementation of a postal system, a telecommunications system, and the use of helicopters. At that time, low fares throughout the Soviet Union also enabled easier and more egalitarian access to mobility (Sahadeo Citation2019).

The Post-Soviet Period: Infrastructural Decay and Marginalization

In the months and years following the demise of the Soviet Union, the mobility, administrative, and economic situation in Tajikistan was rather typically post-colonial, as roads maintained by an economically powerful “colonial” state slowly deteriorated after its withdrawal (see for example Porter Citation2012 for the case of Ghana). Although the use of the terms colonial/post-colonial in the Soviet context is questionable, it is clear that the collapse of the political system under which roads were built, transport systems managed, and a large-scale provisioning system implemented led to national socio-economic turmoil that can still be felt today. Provisioning and accessibility issues were soon aggravated by civil war. As Mostowlansky (Citation2014, 191) sums up:

Due to the region’s location at the border of once hostile Afghanistan and China, Gorno-Badakhshan received generous state supplies and experienced a period of relative prosperity from the 1960s onwards. Contrasted with the post-Soviet tragedy of the Tajik civil war from 1992-1997, this period of prosperity makes Soviet rule retrospectively appear as utterly positive and uplifting from a Gorno–Badakhshan point of view.

As Martin Saxer notes, “the nexus of remoteness and connectivity is anything but stable, it evolves over time” (Citation2019, 189). In the recent history of Tajikistan’s Pamirs, it is clear that the Soviet and Tajikistani regimes have managed physical constraints and accessibility in very different manners, and remoteness has been experienced variously at different periods. While the residents of the region may have felt very included in the Soviet Union, given the influence of the state at that time and the services it provided in terms of mobility and provisioning, they nowadays cannot relate to the state in similar ways because it does not allocate the same range of services. Among the difficulties the residents of the region faced after the collapse of the USSR, the breakdown of mobility infrastructure was foremost. The lack of maintenance after the collapse of the USSR and during the civil war greatly reinforced accessibility issues (see Bliss Citation2006, 300). The civil war period is particularly remembered as a time of isolation, with the road between Dushanbe and Khorog being blocked (see Bliss Citation2006, 6) and the region being closed to the outside world. This situation remained severe until products were delivered from 1993 through Kyrgyzstan, thanks to “an enormous flotilla of trucks” (Bliss Citation2006, 7), to alleviate the humanitarian situation. Nowadays, as flights to Khorog have been suspended since 2017 (and were both scarce and uncertain prior to that, depending on the number of passengers and weather conditions), travel to the region is done from Dushanbe through the city of Kulob, from Kyrgyzstan through the Sary-Tash border, from China through the Karasu border-crossing point (BCP) (not open to foreigners), and from Afghanistan by bridges over the Panj River (Mostowlansky Citation2017a). All passengers and products coming to the region arrive by road.Footnote5 There are no public transportation connections to the region, so passengers travel with private vehicles and mostly with shared four-wheel vehicles (used as shared taxis) that can handle long trips on bumpy roads exposed to rockslides, avalanches, and floods. At certain times of the year, even though the number of private vehicles has increased, finding a seat in a car from Dushanbe and Khorog remains difficult, and although some portions of the road have been renovated, the usual travel time between Dushanbe and Khorog still ranges between twelve and fifteen hours at best.

In the VMKB, as in other ex-Soviet regions, the infrastructural decay has had severe consequences. The M41 is full of potholes over long stretches (especially from Darwoz district to Khorog), which makes traveling times particularly long and physically demanding. The state of the M41, and of other roads of the region that are poorly maintained, is a very concrete reminder of the way mobility was managed during the Soviet times and how infrastructure has been neglected since then. As Mia M. Bennett says, emphasizing the case of Russia, “from Kaliningrad to Kamchatka, rusting railway tracks, potholed roads, and crumbling concrete dramatize the collapse of societal structures both big and small” (Bennett Citation2020, 337). A vivid example of what mobility looked like during Soviet times is the presence all along the M41 of bus stops, often beautifully decorated with mosaics. Now that there is no public transportation in the region, these bus stops seem both anachronistic and out of place. They could be viewed as part of the infrastructural ruination of the former Soviet Union “fetishized” by western bloggers, journalists, or photographers and described by Bennett (332), and which shows “how political and economic disintegration reverberates through the built environment into the present” (337). Clearly, in the past 30 years, the physical accessibility of the VMKB has not constituted a priority for the government of Tajikistan (see Mögenburg Citation2021, on the political aspects of infrastructural ruin). In addition, the topography of the region makes the maintenance of roads particularly challenging and costly, especially with the increasingly adverse effects of environmental changes. As Susan L. Star explains “The normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks” (Citation1999, 382). This is not to say that the mobility infrastructure was perfectly maintained during Soviet times or that all villages were connected to the centers, but the deterioration of the M41 from 1991 to the mid-2010s—and the arrival of Chinese companies—has illustrated the physical disconnection of the region from Dushanbe. This disconnection has become particularly significant when regular flights from Dushanbe to Khorog have ceased to operate. As Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift explain (Citation2007, 17):

Maintenance and repair is an ongoing process, but it can be designed in many different ways in order to produce many different outcomes and these outcomes can be more or less efficacious: there is, in other words, a politics of repair and maintenance.

In the most remote valleys, despite the existence of a national road-maintenance department (still known as DEU, Russian for dorozhno-ekspluatatsionnoe upravlenie), repairs and maintenance are often carried out by residents, with very limited means and without any wages allocated.

Concerning public transport, different studies have shown how transport systems have been reorganized throughout the post-Soviet states, with the emergence of minibuses—marshrutki—as a bottom-up response to the lack of public transport (Sgibnev and Vozyanov Citation2016; Turdalieva and Edling Citation2018). In Tajikistan, many of our interlocutors often complained about the absence of comfort or security in marshrutki. In Khorog, the widely used “Tangen,” small minibuses imported from China, are the most common and cheapest way of moving through the city. They are often in bad condition, considering their low resistance, the poor state of roads, and frequent environmental hazards (see ). In Khorog, the contrast is sharp between the roads and vehicles in rough condition, the aging Soviet buildings, and the hypermodern and imposing infrastructure built by the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) such as the Ismaili Jamatkhana and Center, and the Aga Khan Medical Center (AKMC). Such buildings are the new expression of transnational infrastructural power in the city.

Figure 2. A flooded part of the Bartang road: Oshtorxona, between Basid and Roshorv. © Suzy Blondin, 2017.

The infrastructural neglect has indicated political abandonment of the region and significant economic decay. Today, populations, especially those living far from the M41, need to navigate through the lack of public transport and the poor state of roads. They often repair portions of road without waiting for outside support, and still commonly walk long distances when faced with the lack of motorized mobility options (Blondin Citation2020a; see ). Rural populations of the VMKB suffer greatly from the low physical access to food markets, healthcare facilities, and public services, with the resulting socioeconomic vulnerabilities including food insecurity and lack of income opportunities. The renowned remoteness of the region is often used to explain its political and cultural particularities, economic poverty, and high rate of out-migration, even as that same remoteness is also promoted in tourist brochures and advertisements for the pristine landscapes “offered” by isolated areas such as the Bartang and Wakhan valleys. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of our local interlocutors praised the remoteness of their region as a protector against the virus (as the last section of this paper further explores; see also Blondin Citation2020b).

In sum, the accessibility of Tajikistan’s Pamirs has changed rather quickly and moved in different directions over the last hundred years, from no road and no motorized transportation before the arrival of the Russians, to the construction of roads and implementation of a public transportation system during the Soviet era, and to a certain return of remoteness after the demise of the USSR. Nowadays, the poor state of roads, lack of flight connections and public transportation, and low motorization rate still pose a challenge to the accessibility of the region and participate in its sociopolitical marginalization from Dushanbe. The International Monetary Fund ranked the roads of Tajikistan among the slowest in the world in 2022, presenting, as they put it, “another obstacle to economic development” (IMF Citation2022). Infrastructural ruins in the region are remembances of a time when physical accessibility was easier, and the provisioning system materialized the connection to urban centers throughout the Soviet Union. The VMKB province remains marginalized within Tajikistan, and occasional tensions between the inhabitants of the region and state authorities highlight the distinctiveness and marginality of the province.Footnote6 The VMKB’s low physical accessibility has multiple impacts on local livelihoods in terms of socioeconomic development and opportunities, relations to the state, identity, and mobilities (Mostowlansky Citation2017a). However, physical accessibility issues have not prevented the emergence of new kinds of international connections in the past thirty years, which have significantly changed the shape of the region, and which the next section will explore.

New Borders and New Actors: The Development of International Contacts to Reconnect Tajikistan’s Pamirs

In this section, we focus on the post-1991 actors that have fostered connectivity in the Pamirs by enabling the rehabilitation of physical infrastructure and new types of exchanges. As mentioned previously, the province remains remote and is suffering from a lack of internal connections. However, the new regional context marked by the opening of former Soviet international borders has been conducive to producing exchanges with the outside world, especially in the borderlands.

The Context of the VMKB’s Opening to the World

The end of the 1990s was a historic turning point and a period of radical change for people in Tajikistan. After the end of the Soviet Union, a civil war disrupted social order in the country and destroyed essential infrastructure, including in the VMKB (Bliss Citation2006, 5). At the same time, international borders—especially those with China to the east and Afghanistan to the south—opened up, thus allowing external actors to access a region isolated from the rest of the world for almost seven decades. During the Soviet era, between 1936 and 1991, the borders with Afghanistan and China were completely closed and cross-border contacts nonexistent (Parham Citation2010, 90–91; Sadozaï Citation2021a, 5). Among these new actors, the most active in the region have been the development agencies of the AKDN, founded at the end of the 1960s by their imam, the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of Ismailis across the world. The AKDN has been implementing a large array of programs aimed at improving the livelihoods of the targeted communities, mostly in Ismaili-inhabited countries.

The fall of the USSR provided the opportunity for Ismailis of Tajikistan to reconnect with their imam (Mastibekov Citation2014, 128). In 1993, his development agencies began operating in the country under the AKDN umbrella. Tajikistan was going through an intense civil war (1992–1997) that isolated the Badakhshan province from the rest of the country even more. The imam’s intervention, through the Pamir Relief and Development Program (PRDP), allowed for communities in the VMKB to receive food delivered via Kyrgyzstan to various distribution points in the province (Aga Khan Foundation Citation1993, 1), setting the scene for the beginning of international connections. The imam, through the AKDN, was the very first actor to foster connectivity in the region. The basis for his intervention in Badakhshan certainly lies in the Ismaili doctrine, encapsulated in the Ismaili Constitution, which stipulates the concept of “universal brotherhood” uniting all Ismailis worldwide (Aga Khan IV, preamble, paragraph D, Citation1998), thus debunking national boundaries. Building upon that philosophical concept, the imam himself visited the VKMB for the first time on May 24, 1995, an event still known today in Tajikistan as the “day of light” (ruz-i nur). In his speech in Dushanbe on May 27, 1995, he declared his intention to participate in the opening of the region, explicitly mentioning the help he wished to provide to the government of Tajikistan in connecting with Pakistan and Afghanistan (Aga Khan IV Citation1995), two neighbors with large Ismaili populations and only separated by 30 km of land for the former, and a river marking the administrative border, for the latter.

“Separated by a River, Connected by History”: The Borderlands of the VMKB as an Example of Intense Connectivity in the Pamirs

The end of the civil war in 1997 reshaped the borderlands areas of the VMKB as the AKDN started to physically work on linking the Ismailis of the Pamirs to international networks. The activities taking place along the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan in Badakhshan, the name given to the two provinces on both sides of the border, are the most striking examples of effective and intense connectivity in the post-1991 Pamirs.

The major connectivity-related programs implemented after the civil war at the beginning of the 2000s are to be seen in three major sectors. First, medical mobilities have intensively connected the two banks of the river-border. They emerged in a 2010 project to compensate for the lack of infrastructure and healthcare professionals in Afghan Badakhshan by making use of expertise in Tajikistan. Under this project equipment was provided, medical centers were built, Tajikistani doctors and medical workers were sent to remote Afghan districts, samples could be analyzed in Tajikistan, and a special border regime allowed Afghan patients to be treated at the AKMC in Khorog (interview with AKMC manager, Khorog, July 2021).Footnote7

These achievements, although highly efficient as over 3 000 consultations and more than 300 surgeries were performed annually between 2010 and 2018 (Price and Hakimi Citation2019, 43), were made possible by cross-border bridges, allowing for international trade, another key sector of Tajikistan’s connectivity. According to Mostowlansky, the bridges, the first of which was built in 2002, constitute the “most visible, material aspect” of the reconnection between Afghanistan and Tajikistan (Citation2017b, 3). Besides, the bridges were key to implementing four cross-border markets located at their ends (see ). Afghan traders bring goods from Pakistan or India, and buy animal products from Central Asia to be then exported to Europe, thus making these traders actors of globalization (Marsden Citation2016, 77) and shaping the cross-border markets in Badakhshan as an international connectivity device. Local perceptions of the bridges and the markets give a positive account of their role to connect the remote province of the VMKB with the other side of the border, underlining that the majority of the population support cross-border contacts. One of our respondents living in Ishkashim explained to us that most of the people in the town did not consider the cross-border market as an issue but rather as an economic benefit, assessing that very few people had prejudice against Afghans:

Two years ago, I went [to the cross-border market] and saw the Afghan people, the Tajik people, how they are doing, how they are working, all of them. I think that this is a benefit for the people. Maybe like 10 percent have a problem with the border. (interview with a local inhabitant, Ishkashim, June 2021)

Finally, electricity provision represents yet another symbol of regional connections, as it allows Tajikistan’s hydropower energy to be exported and consumed beyond its borders. According to a concession agreement signed between Pamir Energy and the governments of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan in July 2019 (interview with the regional lead for Strategic Partnerships and Communications, Khorog, August 2019), the quadrilateral partnership plans to expand the electricity network from the VMKB to the Khyber-Pakhtunkha province along the Afghan border with Pakistan (Aga Khan Foundation Citation2021). Beyond the obvious economic aspect, the transmission lines represent a “revival of communication” (Sadozaï Citation2021a, 12) in the Pamirs, a region that once hosted a secular system of connections before the closure of international borders by the Soviet authorities. Since the 2010s, the improvement of Soviet transmission lines is very visible when traveling along the Afghan border. In general, cross-border projects in Badakhshan go beyond administrative limits in the Pamirs by overcoming barriers to foster connectivity. Hence the title given to a 2018 Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) report: “Separated by a river, connected by history” (Wilton-Steer Citation2018).

The cross-border programs implemented by the AKDN thus managed to transcend the national border separating Tajikistan from Afghanistan by putting people-to-people connectivity at the core of its principles. Reflecting upon reconnection with their co-ethnics across the border, the Cross-Border Program manager for AKF Afghanistan perceived the programs as a way to overcome remoteness, pointing out that “the cross-border bridges were the first investments that broke up the isolation, the geographic isolation of the area” (interview, Khorog, July 2021), allowing access to roads and bigger markets on the other side.

As this quote suggests, remoteness and connectivity in the Pamirs are deeply entangled. AKDN’s programs have precisely been built upon the isolation of border communities from their national administrative centers in Afghanistan and Tajikistan in order to trigger cross-border and regional connections. Based on the principles of universal brotherhood and transnationalism, the assistance provided by the Ismaili leader’s organizations has been acting on his 1995 wishes to produce connectivity in the Pamirs. A description given by a long-time employee of AKF of his perception of the cross-border programs perfectly captures their evolution over the decades:

I remember when we were working here at the initial stages, in 2009 to 2015–2016, at that time, these cross-border areas, there were no road connections on the Afghan side. […] We had to travel around 10–15 km from the riverside to the village and then at that height, it was difficult to walk, right? So we had to use different means of transportation. Now we have roads in those areas. Most areas are connected to Badakhshan now, main Badakhshan [in Tajikistan]. (interview with finance manager for AKF Afghanistan, Khorog, July 2021)

Foreign Bodies as Enablers of Tajikistan’s New Regional Connectivity

Akin to AKDN’s efforts, Japan’s state-sponsored development aid agency, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), has been very active in promoting cross-border cooperation as part of a regional development vision encouraging exchanges and connectivity between Central and South Asia, with borders as points of contact. Out of the ten JICA programs underway in 2021 in Tajikistan, two of them dealt exclusively with the border regions with Afghanistan. One project in particular, called “Project for Promoting Cross-Border Cooperation through Effective Management of Tajikistan’s Border with Afghanistan,” is dedicated to exploiting the potential of the border in the autonomous province. It aims to improve the infrastructure of six BCPs, including five in the VMKB, and two cross-border markets (Darwoz and Ishkashim).Footnote8

Projects to rehabilitate roads linking Tajikistan to Afghanistan—in particular a 190-km stretch of the A384 road linking Dushanbe to Nizhny Pyanj in the Khatlon province at the Afghan border—must be understood in connection with those directly affecting the border, since these forms of cooperation will eventually facilitate the transit of goods to the Indian Ocean (Rakhimov Citation2014, 82). In the long run, Japan’s goal would be to be able to connect Dushanbe to Kabul through the reconstruction of land roads to reduce travel time (Usmonov Citation2015, 116). The development of transport infrastructure goes hand in hand with those that promote cross-border contacts mentioned above: the border of Tajikistan in the Pamirs is seen as a contact zone to support the opening up of Tajikistan and regional trade.

China has also been taking advantage of its approximately 470-km-long border with Tajikistan in order to engage in international land trade exchanges, thus “filling the gaps in the existing transport and energy supply routes’” (Dave and Kobayashi Citation2018, 271) of this landlocked country. This endeavor sharply contrasts with the late Soviet era characterized by the absence of relations with the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic and the lack of infrastructure to connect its western façade (Parham Citation2016, 354). Meanwhile, independent Tajikistan has built upon its topographical constraints to seize the opportunity of being connected to its powerful eastern neighbor (Olimova et al. Citation2006, 30), in order to support internal economic growth as well as to access global markets. In 2004, the opening of the high-altitude plateau Karasu BCP paved the way for the development of physical connectivity. In 1999 construction had already started on the road between Kulma and Karasu (Jonson Citation2006, 85). As the only BCP between the two countries, located at the foot of the Kulma pass at 4,363 meters (Kreutzmann Citation2017, 236), Karasu allows for the connection between Dushanbe and the Chinese trade hub of Kashgar, mainly for the transportation of goods, even though “in June (2004) the first passenger bus arrived in Khorog, in Gorno-Badakhshan from Kashgar in Chinese Xinjiang, after a 700-km journey through mountainous terrain in about 24 hours” (Jonson Citation2006, 86). In other words, it provided direct access between China and Tajikistan without traversing Kyrgyzstan. Since the opening of the border and its BCP, the amount of shipped goods increased from 833 tons to 389,600 tons between 2004 and 2014 (Safarmamadova, Siemering, and Yang Citation2020, 8).Footnote9

In 2013, the official launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—and its component in Central Asia, the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB)—by Chinese leader Xi Jinping marked yet another step in the international opening of the Pamirs. In October 2018, the inauguration of a new BCP in Langar (JICA Citation2018a), at the very end of the Wakhan corridor (see ), carried a symbolic value and a pragmatic goal to merge two international transit routes—the Karakoram Highway connecting the region of Xinjiang in China to the province of Punjab in Pakistan, with the Pamir Highway linking Dushanbe to the major trade hub of Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan. In other words, the BRI will eventually connect Tajikistan with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the other regional Chinese economic trade corridor going southward to the Gwadar port. As explained to us in July 2021 by a construction worker at Langar BCP, the point of such local infrastructure is “to connect Tajikistan with Pakistan, which is very close to us,” thus indicating the opening of remote areas to massive regional projects.

Figure 4. Langar BCP and cross-border bridge between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. © Mélanie Sadozaï, 2021.

To further optimize this endeavor, Chinese companies have been rehabilitating portions of the Pamir Highway. In the summer of 2021, one could very easily observe local construction workers near the city of Qala-i Khumb in the Darwoz district, operating in Chinese trucks. In July 2022 we observed the completion of that portion into a paved and even asphalt road (see ). These were the concrete consequences of the grant allocated by China reaching over 200 million dollars to rehabilitate the Qala-i Khumb–Vanj–Rushan section of the Pamir Highway (Asia Plus, June 17, Citation2021b).Footnote10 More recently, on August 30, 2021, representatives of the China State Construction Xinjiang Construction Engineering group and the Ministry of Transport of Tajikistan signed an agreement to engage in rehabilitating another road in the Khatlon province (Asia Plus, August 30, Citation2021f), contributing to opening the VMKB to the west while integrating it physically into the BRI. These large-scale projects are not limited to developing local infrastructure; they also “link the regions of Central Asia and South Asia more closely with China […] and develop these as a transport corridor linking China to Europe” (Dave and Kobayashi Citation2018, 268).

Figure 5. Newly paved road at the entrance of Qala-i Khumb, Darwoz district of Tajikistan. © Mélanie Sadozaï, 2022.

We have outlined here the major achievements of Tajikistan’s international contacts since the end of the 1990s by using examples of visible connectivity.Footnote11 It should also be noted that many projects embody Tajikistan’s Pamirs opening at the international level. Among the initiatives supported by the AKDN, in the tourism sector, the Pamirs Eco Cultural Tourism Association (PECTA) is engaged in supporting foreign travelers in the Afghan and Tajikistani Pamirs; in education, the University of Central Asia (UCA) located in Khorog attracts researchers from Europe, Iran, and North America to teach local students, and the AKDN provides a large array of scholarships to enable Tajikistanis to study abroad; JICA also offers scholarships for Tajikistani students to be enrolled in a master’s program in Japan, via their human resources development aid (JDS) program (JICA Citation2019).

An analysis of the renewal of connections in the Pamirs through physical infrastructure should not be limited to education, economy, and health-related projects. As Hermann Kreutzmann notes, “traders from Pakistan visit Chinese markets; cultural performers from Sarikol are appreciated in Gojal [in Pakistan]. Gojali singers and dancers attend Silk Road festivals in Khorog, Tajikistan, and vice versa” (Kreutzmann Citation2017, 236). Indeed, beyond the economic benefits triggered by a new system of connections, infrastructure development over the past thirty years has also revived the ethnic and cultural bonds in the Pamirs that were cut off during Soviet times (Sadozaï Citation2021a).

Clearly, the connectivity initiatives described here sharply contrast with the accessibility issues outlined in the previous section of this paper. It is worth keeping in mind that the VMKB as a border zone seems better connected to its foreign neighbors than to the Tajikistani administrative center in Dushanbe. In the Pamirs, a strong disparity remains between the connectivity and dynamism of border areas compared to those of the valleys located away from the border, such as the Bartang, Vanj, or Yazgulom valleys: portions of roads have been built or rehabilitated, yet those living away from them remain marginalized, thus making them even more vulnerable to future challenges hitting the connectivity of the province

Future Prospects: Pressing Challenges to Accessibility and Connectivity in the VMKB

The third section of this paper reflects on the ways the issues of accessibility and connectivity in the VMKB could evolve in the next years. Here, we discuss the main elements that greatly influence the accessibility of the region and its connectivity and could further impact it in the future: climate change, financial and administrative obstacles, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the recent regime change in Afghanistan.

Internal Dynamics Affecting Accessibility and Connectivity

High mountain roads are particularly hard to maintain. They need to be protected from rockslides, landslides, avalanches, and floods. Roads in Tajikistan are regularly closed due to these hazards (Blondin Citation2020a; see also Asia Plus, July 14, Citation2021d). Protecting the region’s roads from rockslides or avalanches with fences would require massive investment, and the current climate-change trends could make things even more complicated. In mountain areas, glacial melting is likely to trigger more floods, and a change in precipitation patterns could lead to more rockslides or avalanches (see Blondin Citation2019, for a review). In the Bartang Valley, for instance, many of our interlocutors observe such trends, and notice the increasing unpredictability of weather patterns and the growing intensity of rainfalls. In Tajikistan’s Pamirs, as in many areas all over the world, climate change poses a serious threat to the mobility infrastructure and the future of mobility.

Disaster risk reduction and resilience initiatives are flourishing in the region, implemented by actors such as the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH; see AKDN Citationn.d.), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (EDA Citation2020), and the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ Citationn.d.), but it seems that the issue of accessibility is not often addressed. Such initiatives tend to aim at helping residents remain in their place of residence and adapt to the adverse effects of hazards. However, local livelihoods usually involve frequent mobility between rural and urban areas, within Khorog, or between Khorog and Dushanbe, and mobility disruptions threaten the residents’ socioeconomic opportunities and quality of life. Interestingly, a recent project presented by the AKAH (together with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] and the design firm KVA MATx) that aims at helping the residents of the Basid village, in the Bartang Valley, remain in their village and adapt to hazards, includes the construction of a Community Drone Port in order “to transport medicine and food in times of emergency” (AKDN Citation2021a). This puts into question the future of mobility in the region: will drones be the new vehicles for the provisioning of the region? In other areas worldwide, drones are increasingly used for humanitarian purposes, in order to ease remote communities’ lives (see Rejeb et al. Citation2021, for a review). A drone system could effectively facilitate provisioning and emergency relief, but it would not increase people’s mobility capacity, and would also necessitate massive investment to be implemented. Disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation initiatives would really need to take into account the residents’ needs in terms of circulation and mobility. AKAH’s ambition “to transform Khorog into a model resilient city” (AKDN Citation2020) would also require addressing the resilience of the region’s mobility infrastructure and vehicles in the face of climate change.

As evoked in the first section, repairing and maintaining roads is also particularly costly, especially when they are threatened by environmental hazards. This is a challenging issue for poor and mountainous countries like Tajikistan. In 2021, the former governor of the VMKB, Yodgor Faizov, declared that it would “take 10 or 15 years to bring GBAO roads into line with international standards” and emphasized the financial burden of such a project, declaring “unfortunately, we have not yet found financial sources to carry out repair work” (Asia Plus, August 6, Citation2021e). While numerous foreign actors appear to be addressing the issue, this is apparently not enough. Two months before Fayzov’s declaration, an Asia Plus article indicated that “Reported estimates of how much Beijing might gift Tajikistan [for rehabilitation of the Qala-i Khumb–Vanj section of Dushanbe–Khorog highway] vary from 186 million USD to 226 million USD. And it is not yet known what China will expect in return” (Asia Plus, June 14, Citation2021a). Time and money needed for the repair of the M41 highway are certainly hard to estimate, but China definitely has a huge interest in developing the connections between its territory and Dushanbe via this road. Chinese companies have long been involved in the (re)construction of roads and bridges in the Pamirs, with a usually discreet presence in the region (Saxer Citation2020). Renovated roads would surely help residents circulate within the region and to other Tajikistani provinces; however, roads are not sufficient, and the absence of public transport and the weak motorization rate in the VMKB would also need to be addressed in order to improve the residents’ mobility capacity.

In addition to weather-related and economic constraints, administrative barriers also restrict the accessibility of the region and people’s mobility to neighboring areas, and would need to be facilitated in the future. Border crossings involve long waiting times, significant fees, and multiple documents for traders crossing the China–Tajikistan border, for instance. In addition, private vehicles from Tajikistan are not allowed into China, which means additional fees and logistical constraints for Tajikistani traders. According to Khursheda Safarmamadova, Sarah Siemering, and Ye Yang (Citation2020, 12):

On the Chinese side, it takes a long time for the truckers to wait for the Chinese customs to perform the checks of goods and documents. Their hours of operation are from 11 am to 12 pm and 2 pm to 5.30 pm. Hence, only 20–30 vehicles can go through the Karasu border each day, which leads to long waiting times of one to three days. On the Tajik side, the border officials work more efficiently. Truck drivers can usually pass the border quickly when they make an informal payment of US$ 100–200.

Administrative and financial constraints to crossing the border to China severely limit economic opportunities, and there is a major trade imbalance given the differentiated economic resources of Chinese and Tajikistani traders. This is especially true for traders from Khorog, who need to travel all the way to Dushanbe for visas and other documents required to enter ChinaFootnote12 (Safarmamadova, Siemering, and Yang Citation2020, 12). Increasing cross-border connections from the VMKB would necessitate the facilitation of administrative procedures to go back and forth between neighboring countries. Besides such obstacles, major external factors also restrict the region’s connectivity and international openness.

Preserving Connections despite External Troubles’ Effects on the Province

Ever since the arrival of international actors in the VMKB, the province has been connected to its neighbors and to some extent to the world. This international opening, lacking during the Soviet era, has also made Tajikistan vulnerable to external crises, which impacts connectivity in the Pamirs and could further influence it in the coming years.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

During the 2000s, world turmoil was not necessarily felt in the Pamirs, even during the wars in Afghanistan, when the border was not massively crossed and closure for safety reasons was only temporary. It was not until the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in early 2020 that the communities of the VMKB started feeling disconnected from outside as the Tajikistani authorities completely closed all national borders. Mobility between the different provinces of Tajikistan was severely restricted in spring 2020 and daily mobility in the country reduced (see Yamada and Shimizutani Citation2022). Employees of AKF have had to put some of their programs on hold; all the cross-border markets have ceased to operate; and people have stopped traveling abroad. Locals have complained about the deterioration of their economic conditions, not only because the border with Afghanistan was closed, but because of the general impacts of the pandemic on the economy:

A lot of money comes from Russia to our sideFootnote13; since coronavirus, no work, no money. […] I heard from the oldest people that during the civil war it was not as hard as now because they could cross the border and exchange things with Afghanistan and buy food. But [with] the coronavirus, they cannot go anywhere. (interview with a local inhabitant, Ishkashim, June 2021)

On the eastern side of the province, in the district of Murghab, local communities have seriously suffered from their disconnection to Kyrgyzstan (especially to the city of Osh via the Sary-Tash border) since the closure of the border, because of strong translocal family ties and because so many of the products available on the Murghab market come from Kyrgyzstan (Ibragimova Citation2021, July, 30). The “wave of rebordering” (Radil, Castan Pinos, and Ptak Citation2020, 134) across the world following the outbreak of the pandemic led to a reduction of connectivity and cross-border exchanges, and the Pamirs region has not been spared; the situation remains uncertain at the time of this publication.

However, it is clear that the COVID-19 frictions at the borders of the Pamirs revealed two forms of remoteness, which we have characterized, first, as a protective isolation allowed by the local environmental features, and second, as a compelled isolation as a result of border closure. On the first hand, for many Pamiris being isolated was perceived positively, as they felt protected by the physical barrier of the mountains. Until the end of June 2021, our interviewees claimed that the virus had not arrived in the province, that those infected did not have a severe form, and that the virus was “imported from Dushanbe.” Whether in the Bartang Valley or in the district of Ishkashim, the recurring narrative was that of the preservation of the province due to the climate (in Tajik: havoi tozo) (fieldwork observations, May 2020 and June 2021; see also Blondin Citation2020b). Locally, such positive perceptions of remoteness reinforce (and are reinforced by) the vision of remote valleys as refuges (panogoh) against urban instability or disturbances. On the other hand, the isolation of the province escalated after the closure of all physical international borders, including those with Afghanistan to the south, China to the east, and Kyrgyzstan to the north. As trade and cross-border activities were suspended, the boundary function associated with the political border was reaffirmed with the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision to close the borders, which was almost unanimous in the world, also raised the issue of isolation, especially since this decision was taken in the capital, far from the periphery where the fallout is felt the most (Ikotun, Akhigbe, and Okunade, Citation2021). The pandemic once again has confronted the inhabitants of the Pamirs with their remoteness from the rest of the country and the particularities of the VMKB in contact with Afghanistan. While the borders of Tajikistan have gradually reopened and international trade and flows have resumed, the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan in Badakhshan remains closed at the time of this publication under the decision of the Tajikistani authorities, who fear the influence of unrest on the other side in the wake of the political change over the summer of 2021.

The New Situation in Afghanistan

Adding to that constraint, the gradual fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban between June and August 2021 created more confusion in the region and has further restricted regional exchanges. In January 2022 Tajikistan’s president Emomali Rahmon warned publicly against the risk from the activities of international terrorist groups in the northern provinces of Afghanistan, posing a threat to the entire region through Tajikistan’s southern border (Asia Plus, January 12, Citation2021g). According to President Rahmon, the situation is further complicated by the conflict within the Taliban movement along that border, as he considers them extremists. As a consequence, the border remains closed, preventing the return to connectivity.

Tajikistan’s reluctance to negotiate with the Taliban, added to the fear of terrorism spread, has had an impact in the Pamirs. The border and the BCPs remain closed, although apparently the BCP at Sher Khan Bandar in Khatlon has been allowed to open (Asia Plus, July 13, Citation2021c; Firuz and Abdullo Citation2021) and a few individuals cross due to family or health issues (fieldwork observations, July 2022). The anxiety around Taliban-related terrorism along the Tajikistan–Afghanistan border rose in 2015 when shots were heard from the Tajikistani side in Ishkashim and Darwaz districts, and in 2018, when parts of three Afghan border districts fell to the Taliban (Sadozaï Citation2021b, 2–3). Moreover, Tajikistan’s authorities are seriously concerned about the presence of the terrorist group Jamaat Ansarullah, which has been given responsibility for managing five border districts in Afghanistan. The group’s leader is a Tajikistani national; the founder of the group was also a Tajikistani citizen opposed to Rahmon’s government (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Citation2021b, September 25).

In Central Asia, lack of international connections and political will to improve the situation along national borders has led to significant economic damage. In the case of Tajikistan, the example of recurrent tensions with Kyrgyzstan highlights the direct consequences of a suspension of regional connectivity. Ever since the closure of the border with Kyrgyzstan after a deadly clash there in April 2021 (Sullivan Citation2021), one has been able to observe dozens of trucks stationed in Khorog, packed with watermelons intended to reach Kyrgyzstan’s markets, and hear complaints about the end of cross-border contacts emerging from Kyrgyz communities in the Murghab district (fieldwork observations, June 2021). With the closure of the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, the Pamirs region is all the more impacted by the absence of the trade traffic on which local communities’ economic conditions depend. The closure of cross-border markets from February 2020 onward forced Tajikistanis to shift their purchases from cross-border markets to inland Tajikistan. The effect of the pandemic cutting off supplies and limiting the flow of goods from Dushanbe, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, and China automatically led to higher prices due to reduced supply and competition. For example, in the summer of 2021, a bottle of cooking oil that would have cost 20 somoni, about 1.8 dollars, on the cross-border market would cost at least 48 somoni, about 4.2 dollars, in the stores and markets of Tajikistan (Sadozaï Citation2021b). As a result, border communities have been conducting a narrative in favor of reopening the border in order to resume economic activities with Afghanistan.

Tajikistan’s position is unique in the region, as other Central Asian states have not publicly called out the Taliban but rather work toward a normalized relationship akin to that of Russia. China, the major economic state involved in Tajikistan’s connectivity, publicly endorsed the new Taliban governance in Kabul, offering further economic support (News Wires Citation2021, August 16). The friendly relations between China, Pakistan, and the Taliban regime give a sense of the merging of large-scale projects to connect the Pamirs with its neighbors, thus allowing the CPEC to be linked to the Pamir Highway should Afghanistan become stable, under the frame of the BRI. Therefore, the future of connectivity greatly depends on the decisions of regional actors to maintain the development of international economic projects.

Supporting Connectivity as the Answer to External Troubles

Responses to external hurdles by the actors we introduced previously tend to show their willingness to continue fostering connectivity in the Pamirs in particular and in the wider region in general. Recent news and observations thus point to a possible perpetuation of the efforts to keep connecting the region as a whole.

Indeed, the Taliban have welcomed Chinese involvement in reconstructing Afghanistan and have not prevented AKDN’s agencies from operating in the borderlands (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Citation2021a, September 2, 2021; fieldwork observations, July 2021). China’s strategy toward the Taliban entangles economic aims with security goals. The BRI’s implementation depends on securing commercial routes, and consequently all borders in the region. By working hand in hand with the new government in Kabul, and also deploying a military presence in the Badakhshan region (Standish Citation2021, October 28; Markey Citation2020, 114) on top of providing financial support for infrastructure there, China can achieve two crucial tasks: securing its economic interests and ensuring stability in its immediate neighborhood. However, dealing with two governments—Tajikistan and Afghanistan—that maintain strained relations is putting pressure on the development of connectivity that nonetheless remains a common goal for all actors. At the national level, Afghanistan is in need of electricity provided by Tajikistan and Tajikistan benefits economically from exporting it; at the local level, the border communities heavily depend on exchanges with the Tajikistani side. Connectivity with Tajikistan and China through the Pamirs is not only a prerequisite for Afghanistan’s reconstruction, it is an economic need. Consequently, all actors have an interest in pursuing efforts toward a more connected region.

Nearly one month after the Taliban seized control of Kabul, the AKDN affirmed its commitment to Afghanistan in a press release (AKDN Citation2021b). At the same time, the organization’s official Twitter account displayed a post calling for four measures to keep supporting Afghanistan (AKDN Citation2021c). Those public statements confirm the long-time position of the organization when facing political instability in countries where it operates. A few days after the Taliban took control of the border districts in northern Afghanistan, an AKF program manager told us that AKDN would never leave Afghanistan or Tajikistan, but would find a way to adjust its programs to the socio-political situation. Such observations prove the importance of preserving the achievements in terms of development in general, including connectivity improvement. Since the end of the Soviet Union paved the way for a globalized world, international connectivity in the Pamirs has brought many benefits that would be hard to give up.

Reflecting on possible futures for the VMKB’s accessibility and connectivity, this section has attempted to highlight several crucial issues the province has now to face. Internally, weather-related, financial, and administrative barriers severely limit the improvement of accessibility. Externally, the region is vulnerable to events unfolding across its borders; the COVID-19 pandemic and the regime change in Afghanistan have recently put cross-border dynamics into question. Actors involved in connectivity in the Pamirs speak in favor of the development of projects and initiatives to foster regional and international trade, while the recent instances of external turmoil impacting the VMKB and Tajikistan’s official position toward them have so far adjourned those efforts. All these challenges question the future of the province in terms of cooperation and connectivity at every level, and need to be taken into account when imagining possible futures for the VMKB’s connectivity.

Conclusion

Former Soviet areas have undergone a significant restructuring of infrastructure and mobility systems. Soviet transport systems have disappeared, and many roads have been poorly maintained in the years since the collapse of the USSR. As a result, some populations have experienced a decreasing physical accessibility of their regions and declining mobility capacities. Concomitantly, some of these regions have opened up to new areas globally and have developed new ties with international actors. Through a case-study of Tajikistan’s Badakhshan Province, this paper has attempted to show how physical accessibility can quickly fluctuate, in line with political regimes and political priorities, and how processes of marginalization and openness may coexist. The physical accessibility of the VMKB has varied in the past 30 years, and remains constantly challenged by financial, weather- or pandemic-related, geopolitical, and administrative obstacles to better regional integration.

Remoteness is by definition a subjective notion. A place is always remote from another and an individual or a community may be perceived or consider themselves remote from other places, services, or networks. Our fieldwork has helped us understand how residents of Tajikistan’s Pamirs, and particularly of places far away from Khorog, have substantially felt the disconnection of their province and/or valley from the rest of Tajikistan and have gradually become involved in new international networks. For older residents, this change of paradigm has been felt more concretely. The province has moved from being Soviet-oriented to being both marginalized from Dushanbe and integrated into transnational development networks and cross-border initiatives. Interestingly, some of the AKDN’s initiatives highlight the coexistence of two contrasting dynamics: UCA in Khorog offers a top-class infrastructure, while its staff and students suffer from the difficulty of travel to Dushanbe or other Central Asian urban centersFootnote14; the Khorog Urban Resilience Program’s aim to foster the city’s resilience to climate change and to boost “sustainable economic growth and investment” would need easier access to Dushanbe and neighboring countries in order to succeed. This illuminates how an area may both appear to be remote and connected or become increasingly connected while still suffering from low physical accessibility.

Recent initiatives in terms of road building/repairing and international cooperation are changing the VMKB’s territory and offering new opportunities for local actors. However, large-scale and widely advertised projects such as the BRI carried out by the government of China should not distract us from the physical and financial challenges of improving and maintaining mountain roads, especially in a context of climate change, and from the pressing geopolitical challenges the region has to face currently. Neither should it overshadow the fact that “roads are not enough” (to quote the title of Jonathan Dawson and Ian Barwell’s Citation1993 book) and that a better accessibility of the province would also mean accessible transportation options for the residents. Nowadays, in the absence of a public transport system, a seat in a shared car remains hard to find at certain times of the year and recent fieldwork has suggested that it has recently gotten even harder. In addition, the price of a seat for a long trip remains high for most residents, even more so due to the increase of oil prices since the war in Ukraine.

An examination of the residents’ practices and perceptions in terms of mobility enables us to put remoteness into perspective. Even if residents often complain about their region’s low accessibility, some of our interlocutors in the Bartang Valley have insisted on the amenities offered by remote places, which may enjoy protection from the “dangers” of the city and provide feelings of tranquility and purity (Blondin Citation2021). Such perceptions of remoteness are often highlighted for the touristic promotion of the province. Therefore, reflecting on the possible futures of accessibility in Tajikistan’s Pamirs, crucial questions remain: How to incorporate the residents’ vision into future projects regarding their region’s roads? How to facilitate circulation and to increase socioeconomic opportunities on the other side of the border, in Dushanbe, or internationally, without undermining the perceived amenities of a sparsely populated mountain region?

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the funders for supporting this research as well as all the respondents and friends in Tajikistan who agreed to share their stories and experiences with us over the years.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Parts of this section feature in Suzy Blondin’s PhD dissertation (see Blondin Citation2021).

2. “ L’absence de routes était une des plaies du Tadjikistan. Jusqu’à la Révolution d’Octobre, il n’existait pas un kilomètre de route dans la Boukharie orientale” (translation from French to English by the authors). Eastern Boukharia refers to the eastern part of the Emirate of Bukhara.

3. Since we are talking here about the Soviet era, we use the Russian “Gorno-Badakhshan” (GBAO) instead of the VMKB, which both refer to the same administrative unit.

4. Dushanbe was called Stalinabad during the Soviet era.

5. With the exception of national and international official delegations or humanitarian convoys.

6. As recently as in November 2021, following the killing of a local resident by law enforcement officers and soon after the dismissal of former governor Yodgor Faizov, violent clashes have broken out in Khorog between local inhabitants and state authorities, further isolating the region. For more details, see: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-isolated-pamiris-fear-looming-security-crackdown.

7. The program has been on hold since the beginning of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent closure of international borders.

8. The project was launched in 2015 in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for a first phase of three years (JICA Citation2018b, 3), after entering a second three-year phase (2018–2021).

9. Concomitantly, this new flow of merchandise poured poor standard products into the Pamirs that China’s factories did not want to dump after production failure. This is particularly evident in the markets and stores of Vanj’s administrative center, and many people interviewed on the local markets complained about their bad quality, calling fruit and vegetables coming from China “chemical products” (fieldwork observations July 2022).

10. Even though those amounts are mentioned in local media outlets, the investments of the Chinese government in Tajikistan’s roads are not transparent; in particular, the conditions of the contracts are not publicly known. Our observations showed that Chinese workers are often employed as opposed to local Tajikistanis and the environmental aspects are not taken into account.

11. Other large donors have also provided assistance, including the UNDP, European governments, the US government, the PATRIP Foundation, or the Asian Development Bank among others. The bulk of money for AKDN’s activities since the 1990s came from such donors. However, they are mainly funders rather than implementation providers.

12. Such administrative constraints were further complicated by the interruption of Internet access in the region between November 2021 and March 2022 (see: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-isolated-pamiris-fear-looming-security-crackdown).

13. Referring to the remittances sent home by Tajikistani migrants working in Russia. Before the outbreak of COVID-19, in May 2020 more than 1.2 million of them were estimated in Russia, and in May 2021 approximately 810,000, according to the Main Directorate for Migration Affairs of the Russian Federation (Mkrtčân and Florinskaâ, Citation2021, 18). The total population of Tajikistan reached 9.504 million in January 2021, according to the Agency on Statistics under the President of Tajikistan (see: https://stat.tj/en).

14. This impression is based on one of the authors’ stay at the UCA in 2020 and on conversations with UCA staff and students.

References

- Aga Khan Foundation. 1993. “Tajikistan Humanitarian Assistance Project.” Quarterly Narrative Report (internal document). Unpublished.

- Aga Khan Foundation. 2021. “Pamir Energy.” AKFUSA. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.akfusa.org/our-work/pamir-energy/

- AKDN. 2020. “Building a ‘Model Resilient City’ in Khorog, Tajikistan.” AKDN.org. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.akdn.org/project/building-“model-resilient-city”-khorog-tajikistan

- AKDN. 2021a. “’Moving Together’: AKAH, MIT and KVA MATx Work on Voluntary Relocation Planning in Tajikistan.” AKDN.org. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.akdn.org/press-release/%E2%80%9Cmoving-together%E2%80%9D-akah-mit-and-kva-matx-work-voluntary-relocation-planning-tajikistan

- AKDN. 2021b. “Aga Khan Development Network Urges International Community Not to Abandon Afghanistan.” AKDN.org. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.akdn.org/press-release/aga-khan-development-network-urges-international-community-not-abandon-afghanistan

- AKDN. 2021c. “#AKDN calls for the following measures in #Afghanistan.” 13 September 2021. 4:29 pm. Tweet.

- AKDN. n. d. “Habitat.” AKDN.org. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.akdn.org/where-we-work/central-asia/tajikistan/habitat-tajikistan

- Asia Plus. 2021a. “Letters of Exchange on the Project for Rehabilitation of Qalai Khumb-Vanj Section of Dushanbe-Khorog Highway Sent to Parliament.” Asia Plus TJ, June 14. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/economic/20210614/letters-of-exchange-on-the-project-for-rehabilitation-of-qalai-khumb-vanj-section-of-dushanbe-khorog-highway-sent-to-parliament

- Asia Plus. 2021b. “China Allots US$204 Million in no-strings Aid to Tajikistan for Rehabilitation of Roads in GBAO”, Asia Plus TJ, June 17. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/economic/20210617/china-allots-us204-million-in-no-strings-aid-to-tajikistan-for-rehabilitation-of-roads-in-gbao

- Asia Plus. 2021c. “Taliban Movement Reportedly Waives Visa Requirements for Tajik Drivers at Sher Khan Bandar Crossing.” Asia Plus TJ, July 13. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/security/20210713/taliban-movement-reportedly-waives-visa-requirements-for-tajik-drivers-at-sher-khan-bandar-crossing

- Asia Plus. 2021d. “Lightning Strike Kills a Man in Romit; Mudflow Damages Seven Households in GBAO’s Rushan District.” Asia Plus TJ, July 14. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/incidents/20210714/lightning-strike-kills-a-man-in-romit-mudflow-damages-seven-households-in-gbaos-rushan-district

- Asia Plus. 2021e. “It Will Take 10 or 15 Years to Bring GBAO Roads into Line with International Standards, Says GBAO Governor.” Asia Plus TJ, August 6. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/economic/20210806/it-will-take-10-or-15-years-to-bring-gbao-roads-into-line-with-international-standards-says-gbao-governor

- Asia Plus. 2021f. “Chinese Company to Rehabilitate the Hulbuk-Temurmalik-Kangurt Highway.” Asia Plus TJ, August 30. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/economic/20210901/chinese-company-to-rehabilitate-the-hulbuk-temurmalik-kangurt-highway

- Asia Plus. 2021g. “Tajik Leader Emphasizes the Necessity of Creating a Security Belt around Afghanistan.” Asia Plus TJ, January 12. https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/security/20220112/tajik-leader-emphasizes-the-necessity-of-creating-a-security-belt-around-afghanistan

- Bennett, M. M. 2020. “The Making of Post-Post-Soviet Ruins: Infrastructure Development and Disintegration in Contemporary Russia.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 45: 332–347. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12908.

- Bliss, F. 2006. Social and Economic Change in the Pamirs (Gorno-Badakhshan, Tajikistan). Translated from German by Nicola Pacult and Sonia Guss with support of Tim Shar. London: Routledge.

- Blondin, S. 2019. “Environmental Migrations in Central Asia: A Multifaceted Approach to the Issue.” Central Asian Survey 38 (2): 275–292. doi:10.1080/02634937.2018.1519778.

- Blondin, S. 2020a. “Understanding Involuntary Immobility in the Bartang Valley of Tajikistan through the Prism of Motility.” Mobilities 15 (4): 543–558. doi:10.1080/17450101.2020.1746146.

- Blondin, S. 2020b. “Der Blick vom Pamirgebirge in Tadschikistan auf eine globale Pandemie.” Zentralasien-Analysen 141: 3–7. doi:10.31205/ZA.141.01.

- Blondin, S. 2021. “Dwelling and Circulating in a Context of Risks: (Im)mobilities and Environmental Hazards in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains.” PhD diss., University of Neuchâtel.

- Dave, B., and Y. Kobayashi. 2018. “China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative in Central Asia: Economic and Security Implications.” Asia Europe Journal 16 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1007/s10308-018-0513-x.

- Dawson, J., and I. Barwell. 1993. Roads are Not Enough: New Perspectives on Rural Transport Planning in Developing Countries. London: Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd (ITP).

- EDA. 2020. “Maximum Cooperation Needed to Manage Glacier Melt in Central Asia.” Eda.admin.ch. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.eda.admin.ch/countries/tajikistan/en/home/international-cooperation/projects.html/content/dezaprojects/SDC/en/2016/7F07194/phase1?oldPagePath=/content/countries/tajikistan/en/home/internationale-zusammenarbeit/projekte.html

- Firuz, I., and S. Abdullo. 2021. “Taliban Povliial na Geografiu Marshrutov Tadzhikskih Fur. VIDEO (Taliban Influenced the Geography of Routes of Tajik Trucks. VIDEO).” Radio Ozodi, September 19. https://rus.ozodi.org/a/31467798.html

- GIZ. n. d. “Technology-Based Climate Change Adaptation in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.” Giz.de. Accessed 12 April 2022. https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/82076.html

- Graham, S., and N. Thirft. 2007. “Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Culture and Society 24 (3): 1–25. doi:10.1177/0263276407075954.

- Ibragimova, K. 2021. “Border Closure Deepens Isolation of Tajikistan’s Pamir Highlands.” Eurasianet, July 30. https://eurasianet.org/border-closure-deepens-isolation-of-tajikistans-pamir-highlands

- Ikotun, O., A. Akhigbe, and S. Et Okunade. 2021. “Sustainability of Borders in a Post-COVID-19 World.” Politikon 48 (2): 297–311. doi:10.1080/02589346.2021.1913804.

- IMF. 2022. “Where are the World’s Fastest Roads?” www.imf.org. Accessed September 6 2022. https://www.imf.org/en/News/~/link.aspx?_id=A908C7853AC14C0F89CBA07F82427479&_z=z

- JICA. 2018a. “Government of Japan Has Handed over Border-Crossing Point ‘Langar’ to Tajikistan.” October 25. https://www.jica.go.jp/tajikistan/english/office/topics/181025.html

- JICA. 2018b. “Promoting Cross-Border Cooperation through Effective Management of Tajikistan’s Border with Afghanistan.” Project Completion Report (internal document). Unpublished.

- JICA. 2019. “Scholarship Project for Master’s Degree Program Supported by Japanese Grant Aid Start Accepting Application.” November 13. https://www.jica.go.jp/tajikistan/english/office/topics/191113.html

- Jonson, L. 2006. Tajikistan in the New Central Asia. Geopolitics, Great Power, Rivalry and Radical Islam. London/New-York: IB Tauris.

- Khan IV, A. 1995. “Speech Made by Mawlana Hazar Imam at a Public Meeting at the Concert Hall.” Ismaili.net, May 27. Accessed 12 April 2022. http://ismaili.net/timeline/1995/95052730.html

- Khan IV, A. 1998. The Constitution of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims. Geneva. http://www.ismaili.in/ismailiconstitution.pdf?i=1

- Kreutzmann, H. 2015. Pamirian Crossroads: Kirghiz and Wakhi of High Asia. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Kreutzmann, H. 2017. Wakhan Quadrangle: Exploration and Espionage during and after the Great Game. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Louknitski, P. 1954. Le Tadjikistan Soviétique. Moscow: Éditions en Langues étrangères.

- Markey, D. 2020. China’s Western Horizon. Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia. Oxford/New-York: Oxford University Press.

- Marsden, M. 2016. Trading Worlds: Afghan Merchants Across Modern Frontiers. London: Hurst.

- Mastibekov, O. 2014. Leadership and Authority in Central Asia. The Ismaili Community in Tajikistan. London/New-York: Routledge.

- Mkrtčân, N. V., and F. Û.f. 2021. “Migratsiia: Osnovnye Trendy IANVARIA-FEVRALIA 2021 Goda” (Migration: Main Trends in JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2021], Monitoring Èkonomicheskoi Situatsii v Rossii Tendentsii i Vyzovy Sotsialno Èkonomicheskogo Razvitiia (Monitoring of the Economic Situation in Russia Trends and Challenges of Socio-Economic Development).” 10 (142): 16–19. https://www.ranepa.ru/pdf/monitoring/monitoring-ekonomicheskoy-situatsii-v-rossii-10-142-iyun-2021-.pdf.html

- Mögenburg, H. 2021. “Landmarks of Indignation: Archiving Urban (Dis)connectivity at Johannesburg’s Margins.” Roadsides 5: 31–37. doi:10.26034/roadsides-202100505.

- Mostowlansky, T. 2014. “The Road Not Taken: Enabling and Limiting Mobility in the Eastern Pamirs.” Internationales Asien Forum/International Quarterly for Asian Studies 45 (1–2): 153–170. https://hasp.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/journals/iaf/article/view/3982/4091

- Mostowlansky, T. 2017a. Azan on the Moon: Entangling Modernities along Tajikistan’s Pamir Highway. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Mostowlansky, T. 2017b. “Building Bridges across the Oxus: Language, Development, and Globalization at the Tajik-Afghan Frontier.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 247: 49–70. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2017-0021.

- News Wires. 2021. “China Ready for ‘Friendly Relations’ with Taliban, Welcomes Afghan Development Projects.” France24, August 16. https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20210816-china-ready-for-friendly-relations-with-taliban-welcomes-afghan-development-projects

- New York Times. 1940. “Soviet Opens Mountain Road.” September 12. https://www.nytimes.com/1940/09/12/archives/soviet-opens-mountain-road.html

- Olimova, S., S. Kurbonov, G. Petrov, and Z. Kahhorova. 2006. “Regional Cooperation in Central Asia: A View from Tajikistan.” Problems of Economic Transition 48 (8): 5–61. doi:10.2753/PET1061-1991480901.

- Parham, S. 2010. “Controlling Borderlands? New Perspectives on State Peripheries in Southern Central Asia and Northern Afghanistan.” Finnish Institute of International Affairs Report, 26. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/125700/UPI_FIIA_26_Parham_web.pdf

- Parham, S. 2016. “The Bridge that Divides: Local Perceptions of the Connected State in the Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan–China Borderlands.” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1080/02634937.2016.1200873.