Abstract

Context: Although spinal cord injury or disease (SCI/D) results in complex biological and psychosocial impairments that adversely impact an individual’s overall quality of sexual life, sexual health is poorly integrated into the current rehabilitation processes. Therefore, it is vital to promote sexual health as a rehabilitation priority. Herein, we describe the selection of Sexual Health structure, process and outcome indicators for adults with SCI/D in the first 18 months after rehabilitation admission.

Methods: Experts in sexual health and the SCI-High team identified key factors that influence the sexual health outcomes of rehabilitation interventions to inform Driver diagram development. This diagram informed the selection and development of indicators to promote a permissive environment for discussion of sexual health issues among regulated health care professionals (HCPs). A review of literature and psychometric properties of measurement tools facilitated final indicators selection.

Results: The structure indicator is the proportion of rehabilitation HCPs who have completed annual preliminary sexual health training. The process indicator is the proportion of SCI/D inpatients that have a documented introduction to available local sexual health resources. The outcome indicator is a sexual health patient questionnaire used to assess sexual health patient outcomes and sexual health information/educational needs. Rapid-cycle piloting verified that the indicator tools developed are feasible for implementation.

Conclusion: Successful implementation of the Sexual Health structure, process and outcome indicators will promote a permissive environment to enable open discussion, and lead to provision of equitable and optimal care related to sexual health following SCI/D. This will ultimately advance sexual health rehabilitation across the nation.

Introduction

Sexuality is, and always has been, a major priority for human beings. Beyond the basic necessity for reproduction, sexual activity is a form of social engagement, and a way to connect with others in a mentally, spiritually, and physically intimate and meaningful way.Citation1,Citation2 Although these fundamental motives do not change following spinal cord injury or disease (SCI/D), significant physiologic changes occur with respect to sensation, voluntary motor and autonomic function altering sexual arousal, orgasmic potential, ejaculation in men, and sexual positioning for both sexes.Citation3 Furthermore, the secondary health consequences of spinal cord impairment, including bladder and bowel continence and related issues, autonomic dysreflexia, nociceptive and neuropathic pain, depression, and pharmacologic management of such conditions, also affect sexual self-esteem, sexual expression, and sexual satisfaction. Despite these aforementioned impairments, sexual interest typically continues to be a priority for many. Readiness and courage are therefore required on the part of the individual with SCI/D and their current or future partner(s) to learn how to adapt to the functional changes in the body to experience a rewarding and satisfying sexual life after SCI/D.

For the purposes of this manuscript, Sexual Self-Esteem refers to a positive regard for, and confidence in, the capacity to experience one’s sexuality in a satisfying and enjoyable way; Sexual Expression refers to the way in which we present and communicate as a sexual being to the world, through feelings and behaviors around sexual acts, sexual orientation and gender identity; and, Sexual Satisfaction refers to the expression of positive sexual outcomes and relationship intimacy following sexual activity. Sexual Activity refers to sexual acts with self or partner(s), which may or may not include penetrative activity. Sexual Life refers to the physical, mental, emotional and social aspects of sexual activity, expression and relationships. Sexual Enjoyment refers to the pleasure derived from sexual activity with self or partner(s). Sexual Interest refers to sexual urge and/or motivation to seek out and/or engage in sexual activity.

It is well established that improving sexual activity and sexual self-esteem improves quality of life after SCI/D.Citation4,Citation5 Data from a large Scandinavian survey of 545 women with SCI concluded that 80% of women who continued to be sexually active after injury were able to overcome the physical restrictions and mental obstacles related to their injury, and lead active and positive sexual lives with a partner.Citation6 In men, following traumatic SCI, erectile function, ejaculation and orgasm are most severely affected, while sexual desire remains high.Citation7 Personal interviews with 33 heterosexual men with chronic SCI demonstrated that a willingness to adapt their sexual behavior, coupled with the reward of physical pleasure experienced during intercourse, can result in a positive and satisfying sex life.Citation8 High-quality SCI rehabilitation training programs for patients should address expectations for sexual activity and sexual satisfaction within their core curriculum.

A common, albeit outdated, myth is that after SCI/D, one ceases to be capable of being sexually active or loses interest in sexual activity, leading to the notion that sex should not be a rehabilitation priority. While other “more comfortable” secondary health conditions, and their related management concerns dominate rehabilitation programs and rehabilitation research, sexual and fertility rehabilitation is, and always has been, a major priority for persons with SCI/D. It is imperative that such ‘mismatch’ of priorities are more thoroughly addressed by health care professionals (HCPs) in rehabilitation settings. Until recently, sexual and fertility rehabilitation has not been a major priority for HCPs involved in the overall physical, medical and psychological rehabilitation following SCI/D. There are many contributing factors to this traditional neglect, including the personal nature and sensitivity of the subject, the discomfort experienced by HCPs when addressing the topic, and a lack of knowledge or confidence regarding the assessment and management of sexual health among HCPs. However, with the advent of Viagra® (sildenafil) for erectile dysfunction in the late 1990s, the subject of sex has been broached more openly in various media outlets, and expectations of patients with sexual health concerns have risen. Unfortunately, HCPs involved in SCI/D rehabilitation as a whole have not responded to this need with proportional effort in either clinical or research initiativesCitation9 resulting in a major gap in care.

Given that sexual health is biopsychosocial in nature, there are numerous domains in which sexual health issues will arise. This underscores the need for various disciplines (e.g. doctors, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, recreational therapists, etc.) to be informed and competent in providing fundamental sexual and rehabilitation information.Citation3 As a result of substantial variation in clinical services available, coupled with a paucity of formalized sexual rehabilitation services or prioritization of sexual health goals, concerted efforts are required, nationally, to address the current gaps in care and advance sexual health rehabilitation with the goal of improving standards of SCI/D rehabilitation in Canada by 2020.

Indicators can measure the structure, process and outcome of health care services which can evidently facilitate the sustainability of a high-quality health care system.Citation10 Structure indicators are defined by the properties of the setting in which the health care services are deliveredCitation11 while process indicators describe the specific activities involved in providing and receiving of care.Citation12 Finally, outcome indicators describe the effects of health care provided to a given individual or population (e.g. mortality, health-related quality of life, or patient satisfaction, etc.).Citation12 In combination, these indicators serve as a foundation for the development of an evaluation framework that can be widely implemented across various hospital settings as a benchmark for optimizing the overall quality of health care. Indicator data is commonly used to identify gaps and trends in care, inform priority setting and policy formulation, and monitor rehabilitation programs. Furthermore, indicators can facilitate comparisons across and between different health care settings and ensure continuous quality improvement (i.e. benchmarking) while building transparency in health care.Citation13,Citation14

The SCI Rehabilitation Care High Performance Indicators (or “SCI-High”) Project endeavors to advance SCI rehabilitation care by 2020 through consensus derived development, selection, implementation and evaluation of indicators of quality care for 11 Domains of rehabilitation care prioritized by clinicians, researchers and individuals living with chronic SCI/D. This manuscript describes the process involved in the selection, development and implementation of structure, process and outcome indicators for the Sexual Health Domain for adults with SCI/D from rehabilitation admission to 18 months post-admission.

Methods

A detailed description of the overall SCI-High Project methods and process for identifying Sexual Health as a priority Domain for SCI rehabilitation care are described in related manuscripts in this issue.Citation15,Citation16 In addition to the investigative team (www.sci-high.ca), an external advisory committee and national data strategy committee supported the global Project goals and provided oversight regarding the context for implementing all of the planned indicators.

The approach to developing the Sexual Health Domain’s structure, process and outcome indicators followed a modified, but substantially similar, approach to that described by Mainz,Citation11 which included planning and development phases: (a) formation and organization of national and local Working Groups;Citation9 (b) defining and refining the key Domain and specific target construct; (c) providing an overview/summary of existing evidence and practice; (d) developing and interpreting a Driver diagram; (e) selecting indicators; and (f) pilot testing and refinement of the Domain-specific structure, process and outcome indicators. Throughout these processes, a facilitated discussion occurred amongst the Domain-specific Working Group and the SCI-High Project Team to utilize relevant expertise on the topic, while ensuring that the broader goals of the SCI-High Project were aligned across the other 10 Domain Working Groups (as appropriate).

Sexual Health Working Group

Experts in sexual health and relevant stakeholders were invited to participate in the SCI-High Project as members of the Domain-specific Working Group based on their practical or empirical knowledge of SCI/D rehabilitation, sexual health, health service delivery and patient education. The group included sexual health/medicine practitioners, patient and family educators, physiatrists, nurses, postdoctoral fellows and a stakeholder with lived experience. The Working Group met nine times via web-enabled conference calls over an 8-month period, totaling 9 h of discussion related to the development of the indicators, and an additional 3 h thereafter, to refine the indicators and discuss manuscript preparation. Outside of the formal meetings, individual members of the Working Group completed an additional review of the prepared materials, shared resources and/or practice standards with one another, and/or conducted independent evaluations of the proposed indicators.

Driver diagram and construct definition

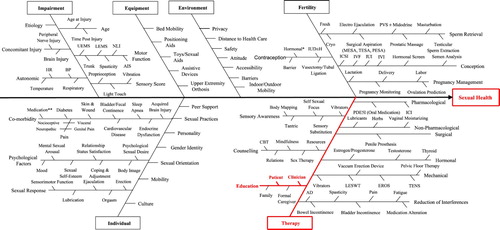

The selection of Sexual Health as a Domain of interest for indicator development emerged from a consensus-building activity intended to select the broader set of Domains being pursued within the overarching SCI-High Project.Citation9 This process involved a systematic search to collect information about SCI/D rehabilitation care related to sexual health, identification of factors that influence the outcome of rehabilitation interventions, and a scoping synthesis of the data acquired. MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL databases were searched using the terms “sexual health”, “spinal cord injury”, or both. The group initially developed four Driver diagrams that were sex and gender specific and related to sexual health. Following several cycles of Driver diagram review and refinement, all four were amalgamated into a single driver diagram (). A Driver diagram is a visual display of a high-level quality improvement goal, and a set of underpinning factors/goals. The tool helped to organize change concepts as the Working Group discerned “what changes can we make, that will result in goal attainment”. The branches in red within the final Driver diagram represent the main areas that were the focus for the development of indicators based on experts’ opinions.

Figure 1 Sexual Health Driver diagram. The impairment branch is common to the 11 SCI-High Project Domains. UEMS: upper-extremity motor score; LEMS: lower-extremity motor score; NLI: neurological level of injury; AIS: ASIA impairment scale; HR: heart rate; BP: blood pressure; IUD ± H: intrauterine devices ± hormone therapy; PVS: penile vibratory stimulation; MESA: microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration; TESA: testicular sperm aspiration; PESA: percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration; ICSI: intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF: in vitro fertilization; IUI: intrauterine insemination; IVI: intravaginal insemination; PDE5I: phosphodiesterase Type 5 inhibitors; ICI: intracervical insemination; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; LESWT: low energy shock wave therapy; EROS: Environmental Rewards Observation Scale; TENS: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; AD: autonomic dysreflexia. *Oral contraception, patches/rings, and provera. **Opioids, antidepressants, antispastic, antihypertensive, and hormones.

Following review of the systematic searches, discussions, and multiple refinements of the Driver diagram, the group agreed that creating a permissive environment among regulated HCPs in relation to sexual health was the driver most likely to advance SCI/D rehabilitation care in the near term. Based on this discussion, and reflection on current terminology related to expression of gender and sexuality, the following construct definition was created: The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.Citation12 In this context, sexuality encompasses: sexual activity, gender identity, gender roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy, contraception and reproduction. Sexual health rehabilitation requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality, self-esteem, sexual relationships, and reproductive wishes, as well as the potential to have consensual, pleasurable and safe sexual experiences.

Selection of indicators

The Working Group asked to develop/select at least one indicator each for structure, process and outcome in relation to the Sexual Health Domain. The Project Leaders stipulated that the indicators should be relevant, concise and feasible to implement (10 min or less), and aligned across the structure, process and outcome to achieve a single substantive advance in SCI/D rehabilitation care. The indicators could be measured using established or new measurement tools (i.e. questionnaires, data collection sheets, laboratory exams, and medical record data), depending on the requirements and feasibility of a given indicator.

Indicator piloting

In order to create a permissive environment, enabling open discussions and to promote sexual health (including post SCI/D sexual activity, self-esteem, expression and satisfaction), the feasibility of the structure and outcome indicators for the Sexual Health Domain were pilot tested. The indicators were reviewed and refined through multiple quality improvement Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)Citation13 cycles for quick qualitative evaluations, feedback and refinement.

Pilot study methods – structure indicator

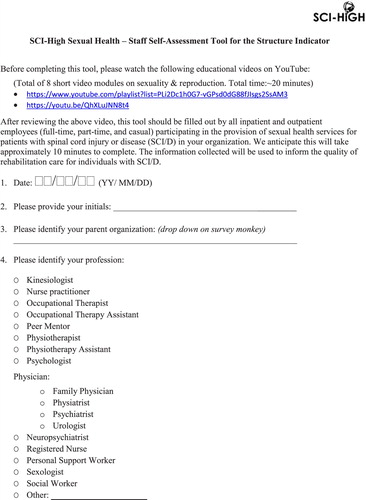

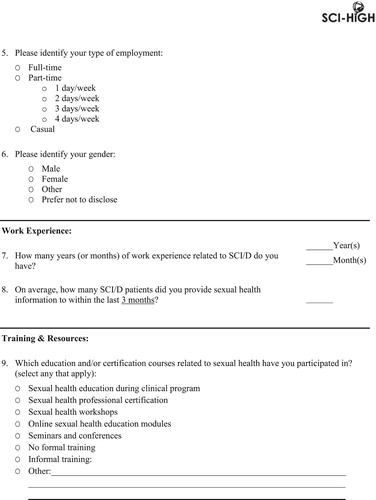

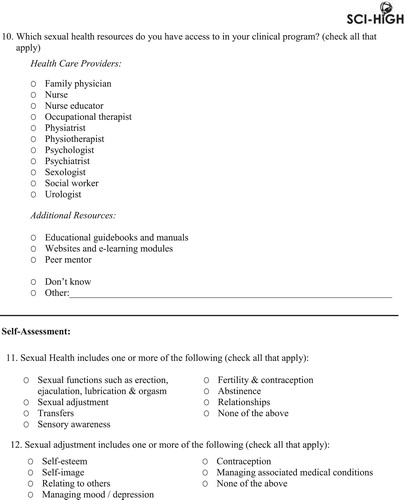

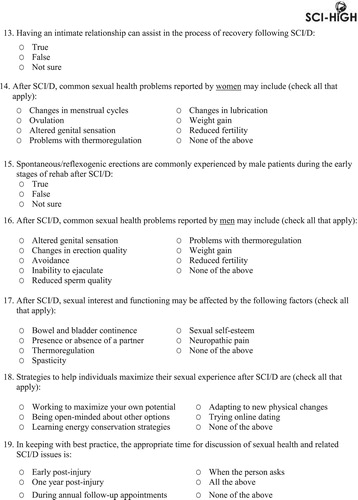

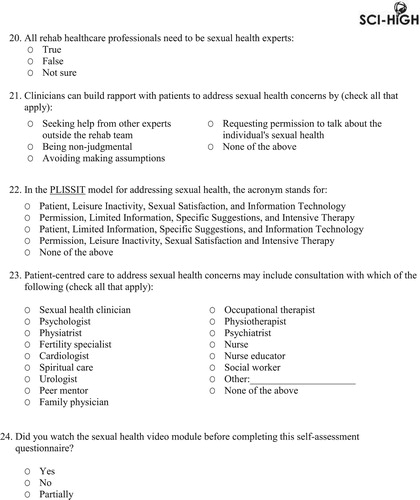

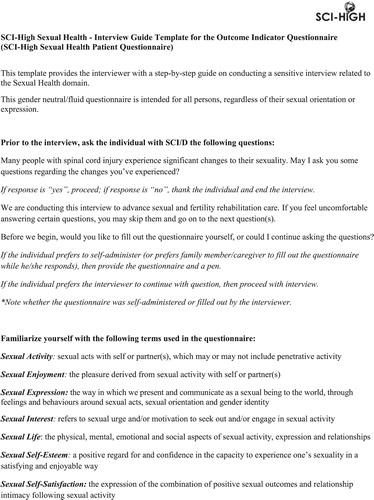

First, a pre and post-self-assessment tool was developed and implemented at a tertiary SCI rehabilitation hospital to assess the knowledge of HCPs involved in SCI/D rehabilitation and to inform sexual health training and education. HCPs were asked to participate in a day-long sexual health workshop and were provided with a sexual health education video comprised of several modules merged into one YouTube online resource. The video modules were developed by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE) project team and Facing Disability, and focused on approaching/initiating patient discussion on sexual health and directing them to appropriate sexual health resources/services (please see ). Permission to use the video modules in this manner was provided by the SCIRE project team. Prior to and following the video modules and workshop provision, a self-assessment tool was administered to HCPs to in order to assess their acquisition of sexual health knowledge, such as active learning and knowledge retention (structure indicator; ) following the training. Additionally, barriers to implementation of the self-assessment tool were noted in order to inform the Working Group.

Table 1 Sexual health video modules for the structure indicator.

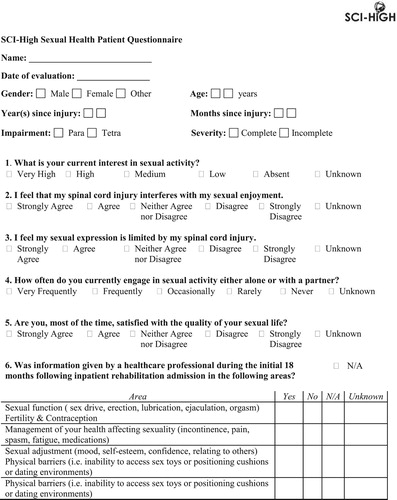

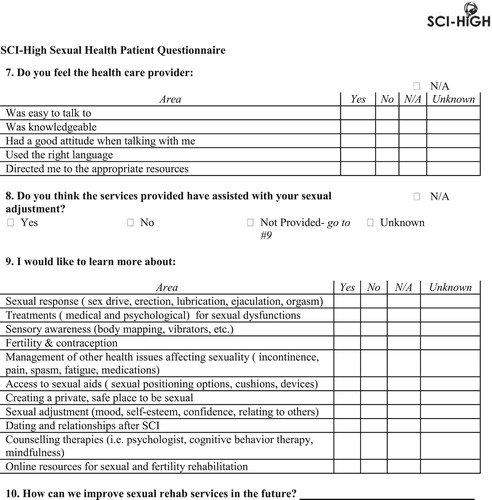

Pilot study methods – outcome indicator

Second, the feasibility of the outcome indicator (sexual health patient questionnaire) was also tested at a tertiary SCI rehabilitation hospital using rapid PDSA cycles. Components from standardized questionnaires (e.g. sexual attitude and information questionnaire, female sexual function index, sexual health inventory for men, etc.) were used to develop the sexual health patient questionnaire. Consecutive patients attending routine follow up appointments were approached by a trained evaluator to complete the questionnaire. Patients were asked if they were comfortable answering sexual health questions prior to consenting to commence with the questionnaire. Physical assistance was provided in completing the paper and pen questionnaire for individuals who could not complete it themselves (i.e. individuals with limited hand functioning). The primary goal of the PDSA cycles for the Sexual Health Domain was to pilot the feasibility of the questionnaire (outcome indicator; ). The questionnaire was designed to collect indicator data regarding sexual health patient outcomes (i.e. sexual expression, sexual self-esteem, sexual activity, and sexual satisfaction) and sexual health service delivery (i.e. quantitative data on information provided by SCI/D rehabilitation staff, staff knowledge; and quantitative and qualitative data on sexual health education/information needs). Furthermore, the feasibility and challenges of implementing the questionnaire were noted in order to inform the Working Group.

Results

The selection and refinement of structure, process and outcome indicators related to Sexual Health were primarily driven by the impetus to create a permissive environment where HCPs support and facilitate individuals with SCI/D to see themselves as sexual beings entitled to sexual satisfaction (as depicted in and the construct definition). Regarding the outcome indicator, standardized questionnaires (e.g. sexual attitude and information questionnaire, female sexual function index, sexual health inventory for men, etc.) were used to develop the sexual health patient questionnaire for the current Project. summarizes the denominators, type of indicator and timing of measurement for each of the indicators selected by the Sexual Health Working Group.

Table 2 Selected structure, process and outcome indicators for the Sexual Health Domain.

Sexual Health indicator piloting

Pilot study results – structure indicator

The pilot data regarding the level of sexual health knowledge includes results from 26 SCI/D rehabilitation HCPs who completed the structure indicator pretest and 19 HCPs who completed the post-test self-assessment tool. There was an increase in the level of knowledge as evaluated by the post-test self-assessment tool following independent review of the video module and workshop attendance. Feasibility issues and challenges experienced included: (1) concerns regarding the confidentiality and privacy of participants’ assessment of knowledge; and (2) difficulty completing the tool in electronic form (i.e. majority of the participants completed a printed hard copy of the tool).

Pilot study results – outcome indicator

The pilot data on sexual health patient outcomes and sexual health service delivery includes results from 20 individuals with SCI/D who completed the questionnaire. Questionnaires were completed within an average of 5 min. Two individuals declined participation due to feeling uncomfortable answering personal questions related to their sexual health. The majority of the participants reported that they strongly felt their injury interfered with their sexual activity, sexual interest and sexual self-esteem, with most being unsatisfied with the quality of their sexual life. With respect to the sexual health service delivery, the majority of the participants reported they were not provided with sexual health information by HCPs and that the level of staff knowledge and/or comfort was not clear. Several participants emphasized the need for timely and tailored information about sexual health (particularly fertility, treatments, counseling therapies and online resources). Feasibility issues and challenges included: (1) the impact of cognitive and motor deficits on the ability to self-administer the questionnaire; (2) inability to understand certain aspects of the questionnaire (i.e. clarifications needed on specific language [e.g. “sexual expression”], and timeframe/setting of sexual health information provided by HCP [e.g. information provided when individual was newly injured or currently, during inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation); (3) the impact of language barriers (i.e. not proficient in English) on the ability to complete the questionnaire; (4) inability to recall if they were provided with sexual health education/information (i.e. those who were several years post-injury); (5) feeling uncomfortable to discuss personal sexual health information, particularly with an evaluator of the opposite sex; and (6) questionnaire was not applicable considering the current sexual health preferences (e.g. due to age, neurological level of injury, other comorbidities, marital/family status).

Discussion

The onset of SCI/D results in complex biological and psychosocial changes that directly and secondarily negatively impact an individual’s overall quality of sexual life post SCI/D. Although improving sexual sense of self (i.e. perception/expression of oneself as a sexual being) and sexual activity improves quality of life after SCI/D,Citation4 sexual health issues are poorly integrated into the current SCI/D rehabilitation care process encompassing both inpatient and outpatient settings.Citation4,Citation14–16 The structure, process and outcome indicators selected and developed by the SCI-High Sexual Health Working Group are intended to: (1) identify learning gaps, and improve capacity amongst regulated HCPs in sexual health; (2) articulate SCI/D patients’ sexual health needs; (3) identify service delivery gaps, and better integrate sexual health into the SCI/D rehabilitation careprocess in order to create a permissive environment that enables open discussion and individual health inquiry; and, (4) improve patient sexual self-esteem, satisfaction and expression.

It is vital to recognize that in order to advance sexual health rehabilitation care, consumer priorities should first be taken into consideration. In 2004, an important survey of 681 individuals living with chronic SCI/D rated sexuality as the first (in individuals with paraplegia) and the second (in individuals with tetraplegia) of seven identified major priorities dictating quality of life after SCI/D.Citation17 This was reiterated again in 2012 by a systematic review of 24 health and life priorities for persons with SCI/D that indicated sexual function, along with motor function, bladder and bowel issues, among the top four functional recovery priorities, and that health and relationships followed as important life domains following SCI/D.Citation18 A current reviewCitation19 of a community sample of people living with SCI/D identified sexual health problems as the most common significant problem after the injury (41%), followed by chronic pain (24%). Indeed, it becomes increasingly important for regulated HCPs to dispel the prevailing myth of the injured individual’s inability to and/or lack of interest in participating in sexual activities, and promote sexual health as a rehabilitation priority. It should also be noted that individuals with SCI evolve in their readiness to gain new information related to their sexual health.Citation20 Therefore, it is essential to ensure sexual health information is provided in a timely manner and tailored to the individual’s (and spouse/partner’s) specific needs as they adapt to the new life post-SCI/D. The first step towards this initiative of addressing the needs of those living with SCI/D is creating a permissive environment to enable open discussion and individual health inquiry.

In order to assist the numerous numbers and disciplines of HCPs in the rehabilitation setting with at least initiating the discussion on sexual health concerns with the patients they care for early in their rehabilitation journey, the Sexual Health Working Group felt there should be an initiative to improve capacity (i.e. sexual health knowledge and skills). In fact, HCPs dealing with SCI/D must address sexual health and sexual treatment needs as part of the routine discussion, with the same frequency and comfort as they discuss neurogenic bowel and bladder dysfunction. Furthermore, similar to urologic or bowel care expertise, referrals to experts can be initiated to manage sexual health issues beyond the team’s expertise, but this relies upon the issues first being identified. Patients expect their physicians and other HCPs to bring up the topic of sexuality,Citation21–23 and tend not to do so themselves, thus relegating their sexual concerns as “less important” and placing the onus on the patient to initiate and sustain the conversation. Even if patients have the courage to do so, their efforts are often met with the HCPs’ discomfort, and/or feelings of inadequacy, in terms of training to deal with such issues, or their discomfort talking about sex itself. Indeed, staff and organizational training and education initiatives regarding sexual health may significantly optimize SCI/D rehabilitationCitation24 and help HCPs meet the sexual health needs of individuals with SCI/D. The indicators developed by the Sexual Health Working Group are intended to establish a new minimum threshold of sexual health knowledge among HCPs, identify available local sexual health resources, and determine the unmet sexual health needs of individuals with SCI/D in the first 18 months post inpatient rehabilitation admission. The Sexual Health Working Group’s premise was that by creating a permissive environment and articulating resources and client needs, staff may direct their continuing education hours toward developing/enhancing their knowledge and skills (e.g. understanding sexual impairment specific to SCI/D), and guide patients to available local sexual health resources as appropriate (i.e. referring patients to experts for management of sexual health issues).

A number of potential barriers with the implementation of the proposed indicators should be considered. First, it should be recognized that new terminology has been introduced that will require sustained use to increase clarity for scientists and recipients. Second, elements from existing psychometric measurement tools (e.g. sexual attitude and information questionnaire, female sexual function index, sexual health inventory for men, etc.) were used to develop the outcome indicator (sexual health patient questionnaire) for this Project. We only used items from existing standardized tools to identify gaps in rehabilitation care relating to sexual health, therefore not all constructs were addressed as originally conceived and validated. Third, the final outcome measurement tool was modified substantially due to specific feasibility restrictions, such as the 10 min time constraint for indicator implementation. Therefore, the newly developed outcome indicator requires further validation. Fourth, while the sample size (26 HCPs; 20 patients with SCI/D) may generally be low in a quantitative research study, it is deemed sufficient for multiple quality improvement PDSA cycles for quick qualitative evaluations, feedback and refinement. PDSA improvement projects do not require large samples to determine a gap in system performance. In addition, small samples can provide valuable information as well as establish validity in PDSA cycles as it may reduce inadequate infrequent data cycles due to collecting too much data in a given cycle.Citation25 Lastly, feasibility was a primary driver for the initial indicators due to the strong desire to establish communites united in their willingness to discuss sexual health, sexual activity and sexual self esteem.

Preliminary pilot data suggests that implementation of the Sexual Health indicators is feasible in identifying HCPs’ level of sexual health knowledge, determining the availability of sexual health resources and articulating the unmet sexual health needs of individuals with SCI/D living in the community. These intial indicators were intentionally designed to be feasible and to facilitate the measurement of advances in sexual health across SCI rehabilitation settings and sectors.

Conclusion

In summary, successful implementation of the selected Sexual Health indicators will concurrently promote a permissive environment and characterize the sexual health needs of individuals with SCI/D during the first 18 months following initial admission to SCI/D rehabilitation. These indicators will identify: (1) the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation HCPs who have completed preliminary sexual health training and education; (2) the proportion of SCI/D inpatients’ who have a documented introduction to available local sexual health resources; and (3) sexual health patient outcomes, and information/educational needs to enhance the quality of sexual life amongst individuals with SCI/D. The implementation of these structure, process and outcome indicators is a first step towards creating a therapeutic environment that enables open discussion and individual health enquiry, thus, leading to the provision of equitable and optimal care related to sexual health after SCI/D.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Declaration of interest Dr. B. Catharine Craven acknowledges support from the Toronto Rehab Foundation as the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Chair in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation and receipt of consulting fees from The Rick Hansen Institute. Dr. Colleen O’Connell acknowledges support from Cytokinetics, Mallincroft, Orion, Biogen, Rick Hansen Institute and ALS Canada. Dr. Colleen O’Connell has also been a receipt of consulting fees from Ipsen, MT Pharma, Tidal, and Canopy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the time, energy and expertise of Dr. Mark Bayley, Dr. Matheus J Wiest and Heather Flett from Toronto Rehabilitation Institute – University Health Network, and Dr. Sander Hitzig from St. John’s Rehab Research Program– Sunnybrook Research Institute throughout the indicator development process.

ORCID

Gaya Jeyathevan http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5525-3214

Farnoosh Farahani http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3937-7708

Anita Kaiser http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3521-7432

S. Mohammad Alavinia http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5503-9362

B. Catharine Craven http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8234-6803

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hensel DJ, Nance J, Fortenberry JD. The association between sexual health and physical, mental, and social health in adolescent women. J Adoles Health. 2016;59(4):416–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.003

- Shpancer N. Why do we have sex? We have sex more for connection than for procreation or pleasure. 2012.

- Elliott S. Sexual dysfunction and infertility in individuals with spinal cord disorders. In: Kirshblum S, Lin VW, (ed.) Spinal cord medicine. Third ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2019. p. 411–35.

- Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL. The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(5):328–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101977

- Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL. Spinal cord injury influences psychogenic as well as physical components of female sexual ability. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(5):349–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101979

- Kreuter M, Siosteen A, Biering-Sorensen F. Sexuality and sexual life in women with spinal cord injury: a controlled study. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(1):61–9. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0128

- Miranda EP, Gomes CM, de Bessa J, Jr, Najjar Abdo CH, Suzuki Bellucci CH, de Castro Filho JE, et al. Evaluation of sexual dysfunction in men with spinal cord injury using the male sexual quotient. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):947–52. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.005

- Soler JM, Navaux MA, Previnaire JG. Positive sexuality in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018;56(12):1199–206. doi: 10.1038/s41393-018-0177-9

- Craven BC, Alavinia SM, Wiest MJ, Farahani F, Hitzig SL, Flett H, et al. Methods for development of structure, process and outcome indicators for prioritized spinal cord injury rehabilitation domains: SCI-high Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S51–S67.

- Alavinia SM, Hitzig SL, Farahani F, Flett H, Bayley M, Craven BC. Prioritization of rehabilitation domains for establishing spinal cord injury high performance indicators using a modification of the Hanlon method: SCI-High Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S43–S50.

- Mainz J, Bartels PD, Laustsen S. The National Indicator Project to monitoring and improving of the medical technical care. Ugeskr Laeger. 2003;163:6401–6.

- WHO. Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 28–31 January 2002.

- Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. Second ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

- Elliott S, Hocaloski S, Carlson M. A multidisciplinary approach to sexual and fertility rehabilitation: the sexual rehabilitation framework. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23(1):49–56. doi: 10.1310/sci2301-49

- Post MW, van Leeuwen CM. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(5):382–389. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.182

- Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL, Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence Scire research T. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(8):1548–55. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2226

- Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(10):1371–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371

- Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(8):1548–55. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2226

- New PW. Secondary conditions in a community sample of people with spinal cord damage. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(6):665–70. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1138600

- Hess MJ, Hough S. Impact of spinal cord injury on sexuality: broad-based clinical practice intervention and practical application. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35(4):211–18. doi: 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000025

- Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2–3):106–17. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.548610

- Mellor RM, Greenfield SM, Dowswell G, Sheppard JP, Quinn T, McManus RJ. Health care professionals’ views on discussing sexual wellbeing with patients who have had a stroke: a qualitative study. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e78802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078802

- Stead M, Fallowfield L, Brown J, Selby P. Communication about sexual problems and sexual concerns in ovarian cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2001;323: 836–7.

- Gill KM, Hough S. Sexuality training, education and therapy in the healthcare environment: Taboo, Avoidance, discomfort or Ignorance? Sex Disabil. 2007;25:73–6. doi: 10.1007/s11195-007-9033-0

- Etchells E, Ho M, Shojania KG. Value of small sample sizes in rapid-cycle quality improvement projects. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):202–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005094