Abstract

Context

Community participation following spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D) can be challenging due to associated primary impairments and secondary health conditions as well as difficulties navigating both the built and social-emotional environment. To improve the quality of SCI/D rehabilitation care to optimize community participation, the SCI-High Project developed a set of structure, process and outcome indicators for adults with SCI/D in the first 18 months after rehabilitation admission.

Methods

A pan-Canadian Working Group of diverse stakeholders: (1) defined the community participation construct; (2) conducted a systematic review of available outcomes and their psychometric properties; (3) constructed a Driver diagram summarizing available evidence associated with community participation; and (4) prepared a process map. Facilitated meetings allowed selection and review of a set of structure, process and outcome indicators.

Results

The structure indicator is the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation programs with availability of transition living setting/independent living unit. The process indicators are the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation inpatients who experienced: (a) a therapeutic community outing prior to rehabilitation discharge; and, (b) those who received a pass to go home for the weekend. The intermediary and final outcome measures are the Moorong Self-Efficacy Scale and the Reintegration to Normal Living Index.

Conclusion

The proposed indicators have the potential to inform whether inpatient rehabilitation for persons with SCI/D can improve self-efficacy and lead to high levels of community participation post-rehabilitation discharge.

Introduction

One of the main markers of successful rehabilitation following spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D) is enabling an individual’s transition from inpatient clinical care to the community where a person can fully participate in diverse social roles.Citation1 For instance, meaningful participation in occupations or employment and/or the ability to engage in societal roles holds significant implications for one’s health and wellbeing,Citation2 is internationally recognized as a fundamental right for all persons, including those with a disabilityCitation3 and represents an emerging policy goal.Citation4 The most widely used definition of ‘Participation’ is the one provided by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which defines it as ‘involvement in a life situation’.Citation5 Although there is considerable debate regarding the nuances of what constitutes participation,Citation6 there is growing recognition that it is “multifaceted and influenced by perceptions, desires and choices”.Citation7 Moreover, participation encompasses a number of aspects of an individual’s life related to their social health and wellbeing, such as engagement, enfranchisement, a sense of agency at both the personal and societal level, and having social connections.Citation8 For many persons with SCI/D, however, the ability to fully participate in their community is often made difficult by their primary impairments and secondary health conditionsCitation9 and because of the lack of accessibility to both the built and social environment.Citation10,Citation11 One possible contributing factor to community participation, such as challenges in accessing transportation,Citation12 undertaking leisure/recreational activities,Citation13 and returning to work,Citation14 is that people with SCI/D often feel unprepared when being discharged from the inpatient setting back to the community.Citation15,Citation16

With the end goal of rehabilitation being to facilitate community participation, an evidence-based approach should be used by rehabilitation professionals to ensure they are providing person-centered care; however, a recent review demonstrated that most studies are of low methodological quality.Citation6 A 2012 environmental scan of Canadian rehabilitation hospitals found that standards are emerging regarding the programs, services and equipment required during SCI/D inpatient rehabilitation to facilitate community participation.Citation17 Unfortunately, there is regional disparity regarding the existing programming and the availability, capacity and complexity of outpatient services offered by rehabilitation sites to support community participation.Citation17 Some of the noted barriers included a lack of dedicated resources and rehabilitation service providers, and unclear and/or cumbersome referral processes. These processes can be further complicated by a lack of access to third-party funding that can provide additional supports to enhance community participation outcomes.Citation17,Citation18 Given the relatively poor levels of available evidence to inform clinical practice and the disparity of care to support community participation post-SCI/D, there is a need to formulate an approach that builds upon a growing consensus for quality measures to support decision-making in healthcare.Citation19

The SCI-High Project is a Canadian wide quality improvement initiative to advance knowledge and clinical care for several domains of SCI/D rehabilitative care. It aims to establish 11 sets of structure, process and outcome quality indicators for care domains during the initial 18 months following admission to inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.Citation20 The decision to use quality indicators as a driving force for national change is based on their efficacy in identifying trends, informing priority setting and policy formulation, and for monitoring rehabilitation programs and care processes.Citation19 Moreover, the use of indicators enables decision-makers to undertake comparisons across different healthcare settings while also supporting quality improvement; all of which are promote transparency in healthcare.Citation21 Hence, the objective of this specific quality improvement initiative is to describe the development of the SCI-High Community Participation indicators.

Methods

The SCI-High Project is a quality improvement initiative to advance the quality of rehabilitation care that intuitively followed from a prior environmental scan (E-Scan) of SCI/D rehabilitation services in Canada conducted between 2009 and 2012.Citation22,Citation23 The E-Scan contained 17 Domain-specific national report cards summarizing the current state of knowledge, clinical standards, and policy, which highlighted the gaps between knowledge generation and clinical application in SCI/D rehabilitation. Using the modified Hanlon method (a well-respected technique to objectively rank health priorities based on defined priority criteria and feasibility factors) and UCLA/RAND consensus methods,Citation24,Citation25 the top 11 prioritized SCI/D rehabilitation Domains were identified, which included Community Participation. A detailed description of the overall SCI-High Project (www.sci-high.ca) methods and process for identifying ‘Community Participation’ as a priority domain are described in related manuscripts.Citation20,Citation26 The development of the ‘Community Participation’ domain’s structure, process and outcome indicators followed a modified approach to that described by Mainz,Citation19 which included: (a) formation and organization of the national and local Working Groups; (b) defining and refining the key domain and specific target construct; (c) providing an overview/summary of existing evidence and practice; (d) developing and interpreting a Driver diagram; and (e) selecting indicators (structure, process and outcome indicators).

Structure indicators encompass the properties of a setting in which healthcare services are deliveredCitation27 while process indicators describe the specific activities undertaken in providing and receiving care.Citation28 Outcome indicators describe the effects of healthcare to a specific individual or population (e.g. patient satisfaction, health-related quality of life, etc.).Citation28 Throughout this process, a facilitated discussion occurred amongst the domain specific Working Group and the SCI-High Project Team to utilize relevant expertise on the topic, while ensuring that the broader goals of the SCI-High Project were aligned across the other 10 domain Working Groups (as appropriate). The selected indicators will be integrated into the larger Project framework to create a group of indicators and related best practices for routine implementation within a single rehabilitation program with project-wide report cards enabling cross site comparisons of structure, process and outcomes.

Community participation working group

Experts and relevant stakeholders were invited to participate in the SCI-High Project as members of the Community Participation Working Group based on their knowledge of SCI/D rehabilitation, community participation, health service delivery, employment and patient education. Hence, we formed a group (N = 13) composed of practitioners, physiatrists, partners from community organizations, policy leaders, rehabilitation scientists, researchers and a stakeholder with lived experience. From this Working Group, representation from the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario and Quebec was obtained. The Working Group met nine times via conference call over a 30-month period, totaling ten hours of discussion related to the development and refinement of the indicators. Outside of the formal meetings, individual members of the Working Group completed an additional review of the prepared materials, shared resources and/or practice standards with one another.

Evidence Map, Construct Definition and Selection of Indicators

The selection of Community Participation as a domain of interest emerged from a consensus-building activity to select the broader set of domains being pursued within the overarching SCI-High Project.Citation20 When developing and selecting indicators, it is also critical to not solely rely on expert opinion but to also be grounded on empirical data.Citation21 Consequently, a comprehensive literature review and intake of existing resources and guidelines pertinent to community participation post-SCI/D was undertaken, which included identifying a list of available community participation outcome measures (see ).

Table 1 Community participation outcome measures.

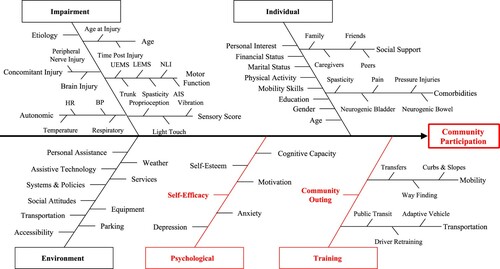

This initiative involved a systematic search to collect information about SCI/D rehabilitation care related to community participation, identification of factors that influence the outcome of rehabilitation interventions, and a scoping synthesis of the data acquired. MEDLINE and EMBASE and CINAHL databases were searched using the terms “community participation”, “community integration”, “spinal cord injury”, or both. This information was then used to create a Driver diagram to illustrate known drivers or factors that impact community participation among individuals with SCI/D (). A Driver diagram is a visual display of a high-level quality improvement goal, and a set of underpinning factors/goals.Citation43 The branches in red within the final Driver diagram represent the main areas that were the focus for development of indicators based on experts’ opinions (see Results for full description).

Figure 1 Community participation Driver diagram. The impairment branch is common to the 11 SCI-high project domains. UEMS: Upper-Extremity Motor Score, LEMS: Lower-Extremity Motor Score, NLI: Neurological Level of Injury, AIS: ASIA Impairment Scale; HR: Heart Rate, BP: Blood Pressure.

With regard to quality indicators, the Working Group was asked to develop/select at least one indicator each for structure, process and outcome that would improve community participation for patients with SCI/D. The Project Leaders stipulated that the indicators should be relevant, concise and feasible to implement nationally. For instance, this might be as easy and quick as indicating the presence of a structure indicator one per year or collecting outcome indicators that could be collected in 10 min or less per patient. Ideally, the indicators could be measured using established or new measurement tools (i.e. questionnaires, data collection sheets, laboratory exams, and medical record data), depending on the requirements and feasibility of a given indicator.

Results

Construct Definition

Similar to the processes followed by other SCI-High Working Groups,Citation44 the initial process for ensuring that the development and selection of indicators would be grounded in either theory and/or evidence was to review the construct definition and to use the Driver diagrams to critically reflect upon it. Following review of the systematic searches, discussions of other conceptualizations/definitions of community participation, and multiple refinements of the Driver diagram, the group agreed that ensuring individuals living with SCI/D are healthy, able and provided opportunities to participate fully in the life situations they deem important was the driver most likely to advance SCI/D rehabilitation care in the near term. Consequently, the group decided that grounding the construct within the (World Health Organization)Citation5 was important since it is widely recognized internationally but that examples of ‘life situations’ also be included with the definition to illustrate different aspects of participation, such as self-care, relationships with others, and engaging in other personal and professional roles. These additions were felt important given there is considerable debate about the construct and measurement of community participation.Citation8,Citation45–47 Based on these discussions, and reflection upon current terminology, the following construct definition was adopted:

Community participation is a broad construct defined by the World Health Organization as involvement in life situations. Within the ICF, a life situation encompasses several areas, including an individuals’ ability to move around their home and community, bathe and dress themselves, engage in relationships with others, participate in social activities and civic life, in addition to employment, education, recreation and leisure activities.

It should be noted that although employment is included as part of the construct definition, the Working Group made the decision to create a separate definition, aim and subset of indicators for employment.Citation48 This was due to employment being a more targeted aspect of community participation that the group felt merited additional reflection and intervention as employment rates post-SCI/D are low.Citation49,Citation50 The Working group also felt that promoting quality improvement in this sub-domain could lead to better outcomes for those individuals interested in returning to work. As well, return to work may not be relevant to the growing number of older adults who sustained their SCI/D when they had already retired or were close to doing so pre-injury. Identifying employment as a separate sub-set of the Community Participation Domain does not ascribe a higher value over other domains of community participation (e.g. recreation/leisure activities), but rather, underscores its complexity and importance of in terms of the potential for vocational re-training, need for special adaptive equipment, workplace accessibility and accommodations, employment schedule recommendations, and other financial considerations, such as loss of public or private third party funding.Citation51

Indicator Development

The selection and refinement of structure, process and outcome indicators related to the Community Participation domain were primarily driven by the impetus to promote community participation (including enhanced self-efficacy) with the goal to empower the individuals with SCI/D to participate fully in the life situations they deem important and ensure successful community integration ( and the construct definition). The decision to focus on these aspects on the Driver diagram were further reinforced by the decision to create a separate set of indicators for employment, and there was already a set of indicators on emotional wellbeing.Citation44 summarizes the denominators, type of indicator and timing of measurement for each of the indicators selected by the Community Participation Working Group.

Table 2 Selected structure, process and outcome indicators for the community participation domain.

With regard to the structure indicator, the Working Group selected the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation programs with availability of a transition living setting/independent living unit. Transitional living units (TLUs) are primary rehabilitation services that are provided either in the patient’s own home, or in a home-like setting that is separate from the inpatient hospital environment, prior to transition to living in the community.Citation52 Transitional rehabilitation services are an innovative approach to promoting continuity of care by enabling people with SCI/D to access support as required but provides them with an opportunity to: (a) re-establish family relationships that have been disrupted due to inpatient hospitalization and the need to assume or alter caregiving relationships;Citation53 (b) develop a sense of personal control and direction in their daily lives; (c) hone newly acquired skills related to the management of their SCI/D in a ‘real world’ context; and (d) develop problem-solving strategies to circumvent access and integration issues associated with returning to home.Citation52

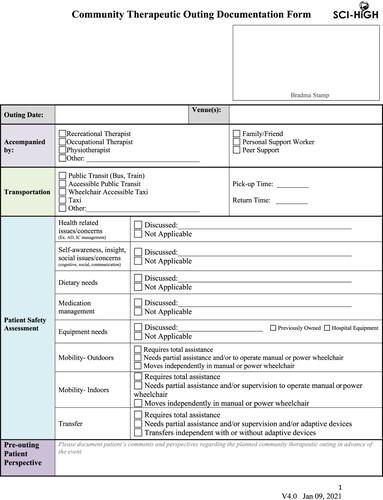

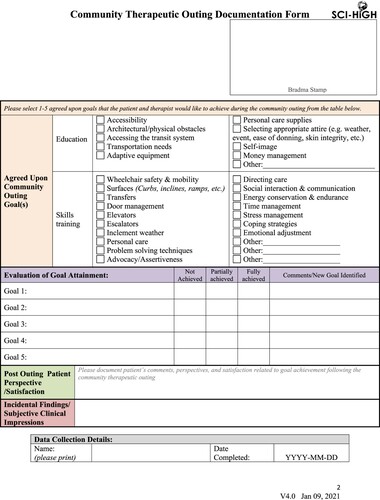

Relatedly, the selected process indicators were the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation inpatients who experienced: (a) a therapeutic community outing prior to rehabilitation discharge; and, (b) those who received a pass to go home for the weekend. With regard to a community outing, this could involve a patient participating in a formal excursion into the community accompanied by healthcare professional, such as a recreation therapist, where there is an opportunity to participate in a recreation/leisure activity and/or to practice newly acquired skills (e.g. accessing transportation). A therapeutic community outing involves joint goal setting, advance planning and an assessment of goal attainment following the therapeutic outing by the individual with SCI/D and their rehabilitation service provider. The Working Group created the Community Therapeutic Outing Documentation Form (), which allows healthcare professionals to document elements related to a community outing, such as transportation, patient safety assessment, and a pre-outing perspective. The form also allows for individuals with SCI/D to select from agreed upon community outing goals (e.g. accessing transit, adaptive equipment, directing care,) between themselves and therapists that they would like to achieve during their community outing, followed by an evaluation of these goals. A therapeutic outing is distinct from an event where an individual spontaneously elects to leave the rehabilitation center unaccompanied, with no pre-planning or post event evaluation of the therapeutic value of the outing. Weekend passes have been recommended as methods to facilitate transition to home from inpatient rehabilitation by providing patients and family members the opportunity to practice living within their home environment prior to discharge from rehabilitation. By going home for a minimum of 2 days/2 nights (e.g. Friday evening to Sunday evening) under the supervision of a family member, the person with SCI/D might identify and resolve problems that could develop after discharge.

Figure 2 SCI-High community therapeutic outing documentation form. Created for healthcare professionals to document elements related to community outing and agreed upon goals between patient and therapist to achieve during community outing.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of SCI/D rehabilitation programs for promoting better community participation outcomes, the Working Group selected outcome indicators that could help ‘predict’ who may be at risk for poor outcomes. A key mechanism associated with improved outcomes following SCI/D, such as community participation, is self-efficacyCitation54–56; (see Driver diagram – ). Self-efficacy is defined as the individual’s belief or confidence in his/her abilities to successfully execute the necessary behavior to produce the desired outcomes in the future.Citation57 Thus, the Moorong Self-Efficacy Scale (MSES)Citation58 was selected as an intermediary outcome measure to be administered to SCI/D patients prior to inpatient discharge, 3 months post-discharge and at 18 months-post rehabilitation admission.

The MSES is a scale designed for the SCI/D population that asks individuals to rate their confidence in their ability to perform 16 tasks (e.g. I can avoid having bowel accidents, I can deal with unexpected problems that come up in life, etc.) using a seven-point Likert type rating scale (1 = very uncertain to 7 = very certain). Scores range from 16 to 112, with a score of 89 or higher being indicative of high levels of self-efficacy.Citation59 The MSES has been validated for the SCI/D population.Citation60,Citation61 In addition to the MSES being designed and validated for SCI/D, the selection of this measure was deemed useful for identifying persons with low self-efficacy, which may put them at greater risk for poorer community participation.

To assess community participation, the Reintegration to Normal Living (RNL)Citation62 Index was selected as the final outcome measure. The RNL Index is an 11-item measure of community reintegration that covers such areas as participation in recreational and social activities, movement within the community, and degree of comfort the individual has in his/her role in the family and with other relationships. The scale has a few scoring options but we selected the 3-point scoring system (0 = does not describe my situation; 1 = partially describes my situation; and 2 = fully describes my situation), with a score of 17 or higher being indicative of high levels of participation.Citation63 The 3-point version was selected since it has been validated for the SCI/D population,Citation63 and data collection over the telephoneCitation64 and is also the version used as part of the Canadian’s Institute for Health Information (CIHI)’s National Rehabilitation Reporting System,Citation65 which collects data from adult inpatient rehabilitation facilities and programs in nine provinces across Canada.

Discussion

The SCI-High initiative established a set of structure, process and outcome indicators to assess community participation in adults with SCI/D in the first 18 months after inpatient rehabilitation admission. The Working Group grounded the conceptual definition of participation using the ICF classification since it is a widely used and internationally recognized framework that has been successfully applied to examine outcomes in persons with SCI/D at the individual, clinical and policy level.Citation66 Based on available evidence and expert opinion, the selected indicators (structure, process, and outcome) were deemed to be feasible, clinically relevant and likely to have the most impact on making a meaningful change in inpatient rehabilitation practice for the SCI/D population.

With regard to the structure indicator, the selection of whether a rehabilitation site has a TLU was based on making a bold statement regarding the inequity of available structures to promote community participation across the country.Citation17 For instance, the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute’s Brain and Spinal Cord Rehabilitation Program at the Lyndhurst Centre (Ontario), which has Canada’s largest SCI/D rehabilitation inpatient and outpatient programs, has a separate living unit within the hospital where patients can practice living in an ‘apartment’ with their family member(s) to obtain a brief reprieve from living in a hospital room with other patients. Alternately, other organizations have separate freestanding apartments with accessible equipment for patients and families to use or rent. Unfortunately, these types of units and/or programs are not commonplace across the country. Hence, the selection of this structure indicator is designed in part to highlight the importance and value of TLUs and to showcase the disparity of availability across the country. It is hoped that this will spur further action for other sites in other provinces to develop their own TLUs.

The process indicators describing the proportion of SCI/D rehabilitation inpatients who experienced a therapeutic community outing prior to rehabilitation discharge and those who received a pass to go home for the weekend were selected to give patients opportunities to apply knowledge and skills gained in rehabilitation in ‘real-world’ settings. In both instances, these process indicators should involve working with the patient with SCI/D to establish a goal with either their community outing and/or weekend pass. Ideally, the rehabilitation period should be one where there is active collaboration between the person with SCI/D and the rehabilitation team to set goals,Citation67 which can serve to identify the person’s needs, values and expectations regarding the rehabilitative process.Citation68 There is evidence that goal setting may also lead to improved adaptation to disability in persons recovering from stroke69, and this may also be applicable to persons recovering from SCI/D.Citation69

Unfortunately, a recent review by Maribo et al.Citation70 that examined the qualitative SCI/D literature on rehabilitation goal-setting found that despite being advocated by health professionals, collaborative goal setting did not always translate into actual practice; with goals tending to be skewed towards physical function. Consequently, some studies indicated that persons with SCI/D did not feel adequately prepared for returning home to deal with the long-term challenges of SCI/D, including vocational, financial and social domains.Citation70 A key argument related to collaborative goal-setting put forth by some of the studies included in this review,Citation70 was that establishing meaningful goals (which may extend beyond recovery of physical functioning) could lead to strengthened autonomy and self-efficacy in persons with SCI/D.Citation71–73 Hence, the use of setting goals with a community outing and/or weekend pass may promote a means for fostering a more collaborative approach to goal-setting between healthcare professionals and persons with SCI/D thereby leading to enhanced community participation outcomes.

The selection of the MSES as an intermediary outcome measure is one that is relatively easy and quick to administer but that is also validated to assess self-efficacy and is highly predictive of community participation outcomes post-SCI/D. For some individuals, the actual (or perceived) limitations associated with their SCI/D may significantly affect the injured individual’s belief in his/her capability to successfully participate in day-to-day activities.Citation61,Citation74 Individuals with high self-efficacy demonstrate active problem-solving and decision-making skills.Citation75 Conversely, decreased self-efficacy has been associated with depression and anxiety,Citation76 and lack of adherence to health and disease self-management,Citation77 which can impede successful adjustment to community living post-SCI/D.Citation55 Importantly, self-efficacy is a modifiable constructCitation78 and improvements in individuals’ self-efficacy have been used as a mechanism to enhance community integrationCitation79 and self-management behaviors among those individuals with SCI/D.Citation80 Unfortunately, there is evidence suggesting that self-efficacy among many individuals with SCI living in the community is suboptimal.Citation74 Thus, if rehabilitation is effective in enhancing self-efficacy, which may include opportunities to practice in real-world settings (e.g. community outing), then it increases the likelihood of better community participation post-rehabilitation discharge.

Finally, the selection of the RNL Index as the final outcome indicator is one that has a number of useful features for SCI/D in the Canadian rehabilitation context, which includes its adoption by provinces collecting health administrative data.Citation63 More importantly, the RNL Index is one of the few subjective measures of social participationCitation1 that is brief and easy to administer. In contrast to the objective perspective of participation, which is focused on the extent to which persons with chronic health conditions are restricted from participation by comparing their status, activities and lifestyles with those of persons of comparable backgrounds (e.g. age, sex, etc.) from the general population, subjective measures emphasize the individual’s preferences to better understand their particular needs and problems.Citation81 Hence, using the RNL Index provides a more person-centered approach to assessing the degree of how persons with SCI/D view their ability to participate in their community.

To support the national implementation of the SCI-High indicators, a meeting was held with managers of Canadian rehabilitation centers that deliver services to patients with SCI/D to review the proposed indicators for all domains, including community participation. The outcome of that meeting was their commitment to explore the adoption and implementation of the potential indicators at individual rehabilitation hospitals. One potential challenge with the roll-out of the indicators is that they have not yet been piloted, which is an important aspect of indicator development.Citation19 However, our Working Group comprised of diverse stakeholders from across the country anticipate that this set of indicators are likely to be well-received given that they should be easy to move into practice without significant additional burden to clinical care and their prior validation in the SCI/D population. Regardless, there will be opportunity for refinement and an implementation science approach (i.e. specifying what, when and how)Citation82 will be used to identify the barriers and facilitators that different sites will need to consider prior to routine implementation of the community participation. In particular, this refinement period may provide opportunities to gain more input from people with SCI/D about the selected indicators as well as to explore the roles of family caregivers in supporting community participation, which was a stakeholder perspective missing from our Working Group. As well, there may be geographic discrepancies across Canadian rehabilitation sites that may require more flexibility on how the structure and/or process indicators are recorded since larger sites in urban settings may have a large number of patients and resources to easily implement them compared to smaller rural settings; thereby leading to a more graded set of options for the site. As well, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has altered rehabilitation service delivery across the country and has limited the ability of rehabilitation programs to support therapeutic community outings and transitional living due to concerns regarding community exposure, staff and patient safety. It is likely that the pandemic may make the need for these services more challenging to justify to policy-makers and funders alike. Hence, the selected indicators will be vital to demonstrating the interconnectedness of specific domains within SCI-High and the anticipated strong associations between therapeutic outings, self-esteem and “good” community participation.

Conclusion

In summary, the use of structure, process and outcome indicators to support community participation across Canadian SCI/D rehabilitation centers holds the potential for promoting better practices to enable persons with SCI/D to optimize participation in the community post-discharge. Although the emphasis of the SCI-High initiative is a quality improvement project, the opportunity to analyze longitudinal data on changes in self-efficacy within the first 18 months from rehabilitation admission and to link it to community participation may help advance research in this domain, which has generally been found to be of low methodological quality.Citation6 Arguably, the community participation domain will be the most meaningful in demonstrating impactful change for SCI/D rehabilitative care since it will be indicative of the collective impact and efficacy of the other SCI-High domains (i.e. Cardiometablic Health, Emotional Well-Being, Sexual Health, Tissue Integrity, Urinary Tract Infection, Walking, Wheeled Mobility, Self-Management, Reaching, Grasping and Manipulation, and Employment)Citation44,Citation48,Citation83–90 being implemented across Canada.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding This work is embedded in the larger SCI-High Project funded by the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute (former Rick Hansen Institute – grant #G2015-33), Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation (ONF – grant #2018-RHI-HIGH-1057), Toronto Rehab Foundation, and Spinal Cord Injury Alberta.

Conflicts of interest Dr. B. Catharine Craven acknowledges support from the Toronto Rehab Foundation as the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Chair in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, and receipt of consulting fees from the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Dr. Vanessa K. Noonan is an employee at the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Dr. François Routhier is supported by a Fonds de la recherche du Québec – Santé Research Scholar. Dr. Sander Hitzig, Dr. Gaya Jeyathevan, Farnoosh Farahani, Dr. S. Mohammad Alavinia, Dr. François Routhier, Dr. Gary Linassi, Dr. Arif Jetha, Diana McCauley, and Maryam Omidvar report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank SCI Alberta, Dr. Dalton Wolfe from the Parkwood Research Institute, Dr. Mark Bayley, Dr. Matheus J. Wiest, Charlene Alton and Heather Flett from the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (University Health Network) for their valuable contributions during the development of the Community Participation indicators.

References

- Magasi SR, Heinemann AW, Whiteneck GG, Committee QoLP. Participation following traumatic spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for research. J Spinal Cord Med 2008;31(2):145–56.

- Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. Am J Occup Ther 2002;56(6):640–9.

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [Internet]. United Nations. 2006. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Accessible Canada Act [Internet]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/A-0.6/.

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2001. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health.

- Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P. Social and community participation following spinal cord injury: a critical review. Int J Rehabil Res 2015;38(1):1–19.

- Cobb JE, Leblond J, Dumont FS, Noreau L. Perceived influence of intrinsic/extrinsic factors on participation in life activities after spinal cord injury. Disabil Health J 2018;11(4):583–90.

- Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Whiteneck G, Bogner J, Rodriguez E. What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30(19):1445–60.

- Tonack M, Hitzig SL, Craven BC, Campbell KA, Boschen KA, McGillivray CF. Predicting life satisfaction after spinal cord injury in a Canadian sample. Spinal Cord 2008;46(5):380–5.

- Carpenter C, Forwell SJ, Jongbloed LE, Backman CL. Community participation after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(4):427–33.

- Chang FH, Wang YH, Jang Y, Wang CW. Factors associated with quality of life among people with spinal cord injury: application of the international classification of functioning, disability and health model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93(12):2264–70.

- Whiteneck G, Meade MA, Dijkers M, Tate DG, Bushnik T, Forchheimer MB. Environmental factors and their role in participation and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85(11):1793–803.

- Jorgensen S, Martin Ginis KA, Lexell J. Leisure time physical activity among older adults with long-term spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2017;55(9):848–56.

- Post MW, Reinhardt JD, Avellanet M, Escorpizo R, Engkasan JP, Schwegler U, et al. Employment among people with spinal cord injury in 22 countries across the world: results from the international spinal cord injury community survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020;101(12):2157–66.

- Dickson A, Ward R, O’Brien G, Allan D, O’Carroll R. Difficulties adjusting to post-discharge life following a spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol Health Med 2011;16(4):463–74.

- Nunnerley JL, Hay-Smith EJ, Dean SG. Leaving a spinal unit and returning to the wider community: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35(14):1164–73.

- Noonan VK, Hitzig SL, Linassi G, Craven BC. Community participation. Rehabilitation environmental scan atlas: capturing capacity in Canadian SCI rehabilitation. Vancouver: Rick Hansen Institute 2012, p. 185–92.

- Anzai K, Young J, McCallum J, Miller B, Jongbloed L. Factors influencing discharge location following high lesion spinal cord injury rehabilitation in British Columbia, Canada. Spinal Cord 2006;44(1):11–8.

- Mainz J. Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the art methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care 2003;15(Suppl. 1):i5–11.

- Craven BC, Alavinia SM, Wiest MJ, Farahani F, Hitzig SL, Flett H, et al. Methods for development of structure, process and outcome indicators for prioritized spinal cord injury rehabilitation domains: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):51–67.

- Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. The advantages and disadvantages of process-based measures of health care quality. Int J Qual Health Care 2001;13(6):469–74.

- Craven BC, Verrier M, Balioussis CWD, Hsieh J, Noonan V, et al. Rehabilitation environmental scan atlas: capturing capacity in Canadian SCI rehabilitation. Vancouver: Rick Hansen Institute; 2012. Available from: https://rickhanseninstitute.org/images/stories/ESCAN/RHESCANATLAS2012WEB_2014.pdf.

- Craven C, Balioussis C, Verrier MC, Hsieh JT, Cherban E, Rasheed A, et al. Using scoping review methods to describe current capacity and prescribe change in Canadian SCI rehabilitation service delivery. J Spinal Cord Med 2012;35(5):392–9.

- Hagglund K, Clay D, Acuff M. Community reintegration for persons with spinal cord injury living in rural America. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 1998;4(2):28–40.

- Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Jha A. New approach to study the contents and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: the SCIRehab project. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):251–9.

- Alavinia SM, Hitzig SL, Farahani F, Flett H, Bayley M, Craven BC. Prioritization of rehabilitation domains for establishing spinal cord injury high performance indicators using a modification of the Hanlon method: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):43–50.

- Idvall E, Rooke L, Hamrin E. Quality indicators in clinical nursing: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 1997;25(1):6–17.

- Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, Rosen AK, Ren XS, Christiansen CL, et al. Risk-adjusted mortality rates as a potential outcome indicator for outpatient quality assessments. Med Care 2002;40(3):237–45.

- International Network on the Disability Creation Process (INDCP). LIFE-H Available Versions and Specimens 2020 [November 12, 2020]. Available from: https://ripph.qc.ca/en/documents/life-h/life-h-specimens/.

- Mellick D, Brooks C, Harrison-Felix C, Whiteneck G. Craig handicap assessment and reporting technique (CHART): a new short form. Annual meeting of the American Public Health Association Boston, MA; 2000.

- Harrison-Felix C. The Craig hospital inventory of environmental factors; 2001. Available from: https://www tbims org/combi/chief/.

- McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, Johnston J, Minnes P. The community integration measure: development and preliminary validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(4):429–34.

- Cardol M, de Haan RJ, van den Bos GA, de Jong BA, de Groot IJ. The development of a handicap assessment questionnaire: the impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA). Clin Rehabil 1999;13(5):411–9.

- Ginis KAM, Phang SH, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP. Reliability and validity tests of the leisure time physical activity questionnaire for people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93(4):677–82.

- Fugl-Meyer AR, Bränholm I-B, Fugl-Meyer KS. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehabil 1991;5(1):25–33.

- Middleton JW, Tate RL, Geraghty TJ. Self-efficacy and spinal cord injury: psychometric properties of a new scale. Rehabil Psychol 2003;48(4):281.

- Ginis K, Latimer AE, Hicks AL, Craven BC. Development and evaluation of an activity measure for people with spinal cord injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(7):1099.

- Washburn RA, Zhu W, McAuley E, Frogley M, Figoni SF. The physical activity scale for individuals with physical disabilities: development and evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83(2):193–200.

- Noreau L, Cobb J, Bélanger LM, Dvorak MF, Leblond J, Noonan VK. Development and assessment of a community follow-up questionnaire for the Rick Hansen spinal cord injury registry. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94(9):1753–65.

- Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI. Reintegration to normal living as a proxy to quality of life. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(6):491–9.

- Neufeld S, Lysack C. The ‘risk inventory for persons with spinal cord injury’: development and preliminary validation of a risk assessment tool for spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32(3):230–8.

- Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A. SCIM–spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 1997;35(12):850–6.

- Phillips J, Simmonds L. Using fishbone analysis to investigate problems. Nurs Times 2013;109(15):18–20.

- Hitzig SL, Titman R, Orenczuk S, Clarke T, Flett H, Noonan VK, et al. Development of emotional well-being indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):85–98.

- Chang FH, Coster WJ, Helfrich CA. Community participation measures for people with disabilities: a systematic review of content from an international classification of functioning, disability and health perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94(4):771–81.

- Fougeyrollas P, Noreau L, Bergeron H, Cloutier R, Dion SA, St-Michel G. Social consequences of long term impairments and disabilities: conceptual approach and assessment of handicap. Int J Rehabil Res 1998;21(2):127–41.

- Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, Raymond E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med 2010;71(12):2141–9.

- Alavinia SM, Jetha A, Hitzig SL, McCauley D, Routhier F, Noonan VK, et al. Development of employment quality indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation care within the community participation domain: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021 [Forthcoming in this special issue].

- Holmlund L, Guidetti S, Eriksson G, Asaba E. Return to work in the context of everyday life 7-11 years after spinal cord injury – a follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40(24):2875–83.

- Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sorensen F. Return to work following spinal cord injury: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29(17):1341–75.

- O’Neill J, Dyson-Hudson TA. Employment after spinal cord injury. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 2020;8(3):141–8.

- Kendall MB, Ungerer G, Dorsett P. Bridging the gap: transitional rehabilitation services for people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25(17):1008–15.

- Jeyathevan G, Cameron JI, Craven BC, Munce SEP, Jaglal SB. Re-building relationships after a spinal cord injury: experiences of family caregivers and care recipients. BMC Neurol 2019;19(1):117.

- Craig A, Nicholson Perry K, Guest R, Tran Y, Middleton J. Adjustment following chronic spinal cord injury: determining factors that contribute to social participation. Br J Health Psychol 2015;20(4):807–23.

- Driver S, Warren AM, Reynolds M, Agtarap S, Hamilton R, Trost Z, et al. Identifying predictors of resilience at inpatient and 3-month post-spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2016;39(1):77–84.

- Guest R, Craig A, Tran Y, Middleton J. Factors predicting resilience in people with spinal cord injury during transition from inpatient rehabilitation to the community. Spinal Cord 2015;53(9):682–6.

- Bandura A, Adams NE, Beyer J. Cognitive processes mediating behavioral change. J Pers Soc Psychol 1977;35(3):125–39.

- Middleton JW, Tate RL, Geraghty TJ. Self-efficacy and spinal cord injury: psychometric properties of a new scale. Rehabil Psychol 2003;48(4):281–8.

- Middleton J, Tran Y, Craig A. Relationship between quality of life and self-efficacy in persons with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(12):1643–8.

- Middleton JW, Tran Y, Lo C, Craig A. Reexamining the validity and dimensionality of the moorong self-efficacy scale: improving its clinical utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97(12):2130–6.

- Miller SM. The measurement of self-efficacy in persons with spinal cord injury: psychometric validation of the moorong self-efficacy scale. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31(12):988–93.

- Wood-Dauphinee SL, Opzoomer MA, Williams JI, Marchand B, Spitzer WO. Assessment of global function: the reintegration to normal living index. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1988;69(8):583–90.

- Hitzig SL, Romero Escobar EM, Noreau L, Craven BC. Validation of the reintegration to normal living index for community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93(1):108–14.

- Korner-Bitensky N, Wood-Dauphinee S, Siemiatycki J, Shapiro S, Becker R. Health-related information postdischarge: telephone versus face-to-face interviewing. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75(12):1287–96.

- National Rehabilitation Reporting System Metadata [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-rehabilitation-reporting-system-metadata.

- Post MW, Kirchberger I, Scheuringer M, Wollaars MM, Geyh S. Outcome parameters in spinal cord injury research: a systematic review using the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) as a reference. Spinal Cord 2010;48(7):522–8.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil 2009;23(4):291–5.

- Siegert RJ, Levack WMM. Rehabilitation goal setting, theory, practice and evidence. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014. https://www.routledge.com/Rehabilitation-Goal-Setting-Theory-Practice-and-Evidence/Siegert-Levack/p/book/9781138075184

- Rosewilliam S, Roskell CA, Pandyan AD. A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2011;25(6):501–14.

- Maribo T, Jensen CM, Madsen LS, Handberg C. Experiences with and perspectives on goal setting in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Spinal Cord 2020;58(9):949–58.

- Angel S, Kirkevold M, Pedersen BD. Rehabilitation after spinal cord injury and the influence of the professional’s support (or lack thereof). J Clin Nurs 2011;20(11–12):1713–22.

- Barclay L. Exploring the factors that influence the goal setting process for occupational therapy intervention with an individual with spinal cord injury. Aust Occup Ther J 2002;49(1):3–13.

- Lenzen SA, Daniels R, van Bokhoven MA, van der Weijden T, Beurskens A. Disentangling self-management goal setting and action planning: a scoping review. PLoS One 2017;12(11):e0188822.

- Pang MY, Eng JJ, Lin KH, Tang PF, Hung C, Wang YH. Association of depression and pain interference with disease-management self-efficacy in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med 2009;41(13):1068–73.

- Heppner PP, Witty TE, Dixon WA. Problem-solving appraisal and human adjustment: a review of 20 years of research using the problem solving inventory. Couns Psychol 2004;32(3):344–428.

- van Diemen T, Crul T, van Nes I, Group S-S, Geertzen JH, Post MW. Associations between self-efficacy and secondary health conditions in people living with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98(12):2566–77.

- Taal E, Rasker JJ, Seydel ER, Wiegman O. Health status, adherence with health recommendations, self-efficacy and social support in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ Couns 1993;20(2–3):63–76.

- Connolly FR, Aitken LM, Tower M. An integrative review of self-efficacy and patient recovery post acute injury. J Adv Nurs 2014;70(4):714–28.

- Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A, Gordon S. Using peer mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J Clin Nurs 2011;20(3–4):351–8.

- van Diemen T, Scholten EW, van Nes IJ, Group S-S, Geertzen JH, Post MW. Self-management and self-efficacy in patients with acute spinal cord injuries: protocol for a longitudinal cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7(2):e68.

- Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Post M, Asano M. Participation after spinal cord injury: the evolution of conceptualization and measurement. J Neurol Phys Ther 2005;29(3):147–56.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50.

- Bayley MT, Kirby RL, Farahani F, Titus L, Smith C, Routhier F, et al. Development of wheeled mobility indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-High project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):130–40.

- Craven BC, Alavinia SM, Gajewski JB, Parmar R, Disher S, Ethans K, et al. Conception and development of urinary tract infection indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):205–14.

- Elliott S, Jeyathevan G, Hocaloski S, O’Connell C, Gulasingam S, Mills S, et al. Conception and development of sexual health indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):68–84.

- Flett H, Wiest MJ, Mushahwar V, Ho C, Hsieh J, Farahani F, et al. Development of Tissue Integrity indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-High project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):196–204.

- Jeyathevan G, Jaglal SB, Hitzig SL, Linassi G, Mills S, Noonan VK, et al. Conception and development of self-management indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021 [Forthcoming in this special issue].

- Kalsi-Ryan S, Kapadia N, Gagnon D, Verrier MC, Holmes J, Flett H, et al. Development of reaching, grasping & manipulation indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021 [Forthcoming in this special issue].

- Musselman KE, Verrier MC, Flett H, Nadeau S, Yang JF, Farahani F, et al. Development of walking indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):119–29.

- Wiest MJ, West C, Ditor D, Furlan JC, Miyatani M, Farahani F, et al. Development of cardiometabolic Health indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-high project. J Spinal Cord Med 2019;42(Suppl. 1):166–75.