Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between the strength of primary care and perceived access to follow-up care services among persons with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI).

Design

Data analysis of the International Spinal Cord Injury (InSCI) cross-sectional, community-based questionnaire survey conducted in 2017-2019. The association between the strength of primary care (Kringos et al., 2003) and access to health services was established using univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusted for socio-demographic and health status characteristics.

Setting

Community in eleven European countries: France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain and Switzerland.

Participants

6658 adults with chronic SCI.

Intervention

None.

Outcome measures

Share of persons with SCI that reported unmet healthcare needs as a measure of access.

Results

Twelve percent of the participants reported unmet healthcare needs: the highest in Poland (25%) and lowest in Switzerland and Spain (7%). The most prevalent access restriction was service unavailability (7%). Stronger primary care was associated with lower odds of reporting unmet healthcare needs, service unavailability, unaffordability and unacceptability. Females, persons of younger age and lower health status, had higher odds of reporting unmet needs.

Conclusions

In all investigated countries, persons with chronic SCI face access barriers, especially with service availability. Stronger primary care for the general population was also associated with better health service access for persons with SCI, which argues for further primary care strengthening.

Subject classification codes::

Introduction

Persons with chronic SCI frequently experience comorbidities and are recurrent users of health services (Citation1, Citation2), requiring a lifetime of comprehensive care (Citation3). Persons with SCI have shorter longevity (Citation4) and more difficulties accessing health services compared to the general population (Citation5–7). Among the access barriers are negative attitudes (Citation8–10), difficulties obtaining information (Citation11), long waiting times (Citation10), inadequate financing arrangements (Citation12, Citation13), inaccessible transportation (Citation14, Citation15), inappropriate medication and medical equipment (Citation16, Citation17) as well as limited provider's experience with SCI (Citation18, Citation19). Females (Citation7, Citation20), persons with immigrant background (Citation21), lower health status (Citation21, Citation22), lower income (Citation23, Citation24), living in a rural area (Citation10, Citation25) reported to experience more barriers. There is also a reverse relationship between socio-demographic factors and healthcare access, as not getting access to health services negatively affects health status, income as well as other characteristics (Citation26–28).

More than 3% of the adult population in the European Union have reported unmet healthcare needs, in which about 2% because of reasons related to the healthcare system (service cost, travel distance or waiting times), and 1% because of reasons classified as not related to the healthcare system (fear of doctors, not knowing where to get the service or lack of time) (Citation29). Lowest unmet healthcare needs in the general population of European countries are reported in Spain (0.3%), Germany and the Netherlands (1%), while the highest in Greece, Poland (9%) and Romania (7%). The cost of care is seen as a principal reason for unmet needs. Most countries with underfunded healthcare systems and a high share of patient costs (e.g. Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania) reported worse access and higher access inequalities (Citation30). Additionally, most health systems have better service access in urban than in rural settings (Citation22, Citation30).

Primary healthcare is linked to care efficiency and equity (Citation31, Citation32). In European countries, strong primary care is found to be associated with better population health and slower growth in health expenditure, yet, higher health expenditure (Citation33). It is unclear whether the positive outcomes of primary care are equally applicable for persons with SCI, whose healthcare needs, due to the SCI complexity and prevailing secondary conditions (Citation34, Citation35), are crossing the boundaries between the levels of care (Citation36, Citation37).

Internationally, there is an ongoing discussion on how to organize care for persons with chronic SCI (Citation36) as no single SCI care model is accepted (Citation3), with equal calls to promote primary (Citation18, Citation36) and specialized (Citation38) care. One of the attributes of a potentially optimal model identified in several studies is multidisciplinary SCI care (Citation3, Citation13). Access to health services did not significantly differ in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, where general care services have been acquired both through family doctors and spinal injuries specialist: in Canada more likely through a family doctor and in the United States more likely through a specialist (Citation17). Persons with SCI tend to utilize emergency care as an inappropriate substitute for primary care when less comprehensive primary care services are available (Citation39). Integrated primary care with SCI specialists’ collaboration may serve an essential function in the care continuum (Citation3).

This study aims to determine the association between the strength of primary care and access to follow-up health services among persons with chronic SCI in eleven European countries partaking in the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI). Specifically, we address the following questions: (1) what are the access restrictions among persons with chronic SCI in European countries?; (2) do healthcare systems with stronger primary care allow better healthcare access for persons with SCI?; (3) which access dimension is mainly altered by primary care strength? The study hypothesis is that primary care-oriented systems allow better access to healthcare services in persons with SCI as well (Citation31, Citation32). While the literature primarily focused on exploring access to specific health services in one region (Citation40), this study investigated access across all healthcare settings in multiple countries.

Methods

Study design and data collection

The present study is based on data from the International Spinal Cord Injury Community Survey (InSCI). InSCI is a cross-sectional, community-based questionnaire survey conducted in 22 countries worldwide during 2017–2019 (Citation41). InSCI was the first international survey describing the experience of persons with SCI living in the community. It aims to provide data for policy and practice changes targeted at strengthening rehabilitation and other services (Citation42). InSCI is part of the International Learning Health System for Spinal Cord Injury Study (LHS-SCI), which was embedded in the World Health Organization's Global Disability Plan (Citation43). LHS-SCI was launched in 2017 with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) and the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) (Citation43).

Details on the sample size, sampling design, study participants’ recruitment strategy, recruitment sources, survey administration mode, and study centers in each InSCI country have been systematically described (Citation41, Citation44, Citation45). The present study population included adults with chronic SCI living in the community across eleven European countries: France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, Switzerland. Participants were adults eighteen years old or older with non-traumatic or traumatic SCI who received first rehabilitation or acute care.

Countries participated in InSCI voluntarily after an invitation from ISPRM and ISCoS, which was given during a conference of these supporting societies. Each participating country had a national study center responsible for the questionnaire translation, cultural adaptation and data collection. Swiss Paraplegic Research in Nottwil, Switzerland, offered initial InSCI training and workshops, coordinated InSCI and provided recommendations throughout the process (Citation41). Each country that took part in InSCI has gotten ethical approval for conducting the survey, while informed consent was signed by each participant or participant's authorized representative. Sampling frames were formed from various data sources: national registries of persons with SCI, databases of academic or level I trauma hospitals, clinical records of specialized rehabilitation centers, and membership registries of organizations for persons with disability or insurance agencies (Citation41). Depending on the country, the 125-item questionnaire had different data collection options, including paper-pencil or online questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone interviews. Collected data were de-identified and saved in a secure central database (Citation41).

Five (45%) of the eleven countries relied on predefined sampling frames: Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Switzerland. These countries represent 75% of the data in this study. Despite possible limited representativeness, the results of InSCI might be the best available evidence regarding the experience of persons with SCI.

Measurements

Primary care strength

As a measure of the strength of a country’s primary care, a comprehensive classification developed through the European Commission’s project Primary Healthcare Activity Monitor for Europe (Citation46) and described by Kringos et al. (Citation47) was applied. The strength was measured by 77 indicators of primary care structure and process. The primary care process was captured by four dimensions: accessibility, comprehensiveness, continuity, and coordination. The structure of primary care consisted of three dimensions: governance, economic conditions, and workforce development. Strong primary care ensures accessible, comprehensive and well-coordinated services supported by the appropriate workforce and governance in suitable economic conditions. Different levels of development in these dimensions lead to cross-country differences in primary care strength.

Eleven countries that participated in the InSCI survey were included in the present study. These specific countries were included because an assessment of their primary care strength was available and described by Kringos et al. (Citation47): strong primary care systems (Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Spain); medium strength primary care systems (France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Poland, Romania, and Switzerland); and weak primary care systems (Greece).

Health service access

The InSCI questions on healthcare service access were adopted from the WHO World Health Survey (2001–2002) (Citation48) and WHO Model Disability Survey (2015) (Citation49). Unmet healthcare needs were a measure of access operationalized as needing but not receiving the healthcare service in the last twelve months. The access restrictions / specific reasons for not receiving the healthcare service were classified across five access dimensions: acceptability (the person was previously badly treated); approachability (the person did not know where to go or thought he or she was not sick enough to require a healthcare service); availability and accommodation (there was no service available; there was no transport to the service available; the person was denied the service; the person could not take time off work or had other commitments); affordability (the person could not afford the service cost or cost of the transportation to the service); and appropriateness (the person thought the healthcare provider's drugs or equipment or provider's skills were inadequate) (Citation50, Citation51).

Socio-demographic and health status characteristics

Education was assessed in line with the International Standard Classification of Education, summing up the total years of formal education, including school and vocational training (Citation44, Citation52). Income denoted equivalent total household income translated to country-specific income deciles, which divide the population into ten income-ranked groups (Citation53).

A summarized score of secondary health conditions was based on a modified version of the Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Health Conditions Scale (SCI-SCS) (Citation54) on experiencing health problems in the last three months. It included the following 14 health conditions: sleep problems, bowel dysfunction, urinary tract infections, bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, contractures, muscle spasms or spasticity, pressure sores or decubitus, respiratory problems, injury caused by a loss of sensation, circulatory problems, autonomic dysreflexia, postural hypotension, and pain. Each health condition was rated from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extreme problem) for all countries except for Switzerland, where a four-point scale was used. The answers in the four-point scale were weighted as 0, 1.3, 2.3 and 4, respectively, to align with the 0–4 weighting in the five-point scale. The SCI-SCS index ranges from 0 to 56.

Statistical analysis

The study was based on a predefined data analysis protocol approved by the InSCI Committee before the study started. The association of primary healthcare system strength as an independent variable and access as a dependent variable was explored by means of univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses. We adjusted for non-modifiable socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, migration background, living arrangement, assistance received with day-to-day activities from family, friends or professionals, education, income, having paid work) and health status and spinal cord injury characteristics (tetra- or paraplegia, complete or incomplete lesion, traumatic or nontraumatic etiology, years lived with injury, SCI-SCS index, self-rated health). The level of statistical significance was set to 5%. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16.1.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study participants

The analysis was conducted among 6658 participants. The survey response rates were only available for countries with predefined sampling frames as follows: Norway (42%), Switzerland (39%), the Netherlands (33%), Germany (32%), and Poland (32%).(Citation44) As presented in , the sample was predominantly male (72%), with an average age of 53. The majority were living with others (95%), receiving assistance with day-to-day activities from family, friends or professionals (76%), with high school education as the highest education level (55%), with no paid job (56%) and income in the lowest three deciles (53%). The majority of participants had paraplegia (59%) for 15 years on average, with an incomplete lesion (60%) and traumatic etiology (78%) caused predominantly by a traffic accident (25%) or a fall (15%). In the last 12 months before the survey, 50% of participants did not have inpatient stays, while 20% had one stay for at least one night, 9% had two stays, and 9% had three and more stays.

Table 1 Socio-demographic and health status characteristics, by country.

Unmet healthcare needs and access restrictions

Across all countries, 12% of participants indicated that they needed a health service in the last twelve months but had not received it (). Across all countries, the largest share of those indicating unmet needs was in Poland (25%) and the lowest in Switzerland and Spain (7%). In other countries, this percentage varied between 9 and 13%.

Table 2 Primary care strength, unmet needs and access restrictions, by country.

The most common access category for not receiving healthcare service was service availability and accommodation (7%), while affordability, appropriateness, and approachability were each reported by 3% of the participants. Acceptability was reported by 2% of the participants. The highest reporting of availability restrictions was in Poland (14%), Germany (10%), Romania and Greece (7%), and the least frequent in France (2%). Both affordability and appropriateness restrictions were most frequently reported in Poland (8% and 6% correspondingly) and least in Spain (both at 1%). Regarding approachability, the highest share of those who reported problems with it was in Poland (9%) and the lowest in Italy (1%). Acceptability issues were most frequently reported in Poland (6%) and with the least frequency (1% or below) in France, Germany, Greece, Spain, and Switzerland.

The most common reason reported for not receiving healthcare was being denied the service (4%). The largest shares of individuals that were denied a needed service lived in Poland and Germany (7%), followed by Lithuania (6%). The smallest share was found in France (1%). The other reasons reported were not being able to afford the service (3%) and no needed service available (3%). Not being able to afford the cost of the visit was most frequently reported in Italy (4%) and least in the Netherlands (1%), while no service being available was most frequently reported in Poland (6%), Italy (4%) and least frequently in France (1%). Other reasons were reported by two percent of the participants or fewer.

Association between health service access and primary care strength

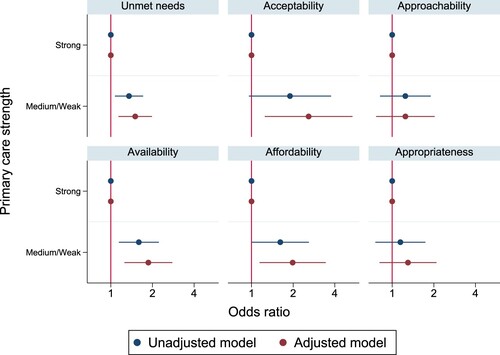

Countries with medium or weak primary care strength showed higher odds of unmet healthcare needs than countries with strong primary care ( and Supplementary Table 1). Females, those of younger age (below 46), lower SCI-SCS score and self-rated health had higher odds of reporting unmet needs. Unmet healthcare needs were not statistically significantly related to migration background, living arrangement, education, income, having paid work, SCI type, SCI degree or etiology, and years lived with SCI (Supplementary Table 1).

A statistically significant association between medium/weak primary care strength and higher odds of reporting service availability and affordability restrictions was found ( and Supplementary Table 1). In both dimensions, 46 years and older individuals with better self-rated health and lower health problem index score had lower odds of reporting service availability and affordability issues (Supplementary Table 1). In univariable and multivariable analyses, no statistically significant associations were found between the strength of primary care and the approachability or appropriateness of healthcare services. Acceptability was statistically significantly associated with the strength of primary care in a multivariable analysis when considering participants’ socio-demographic and health status characteristics. Similarly, 46 years and older individuals with better self-rated health and lower secondary health conditions index had lower odds of reporting acceptability restrictions.

Discussion

According to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study examining the association between the strength of primary care and access to healthcare services in the SCI population from an international perspective. We found that stronger primary care was associated with lower odds of reporting unmet healthcare needs. Most reported issues were with service availability and accommodation and least with acceptability. Females, those of younger age and poorer health had higher odds of reporting unmet needs.

Hence, strong primary care for the general population might also be associated with benefits for persons with SCI. Primary care seems to be equally the first point of contact for the general population and persons with chronic SCI (Citation55). In addition, strong primary care, as in Lithuania, the Netherlands and Spain, leads to greater availability of services and better coordination of patient care beyond primary care (Citation33, Citation47). A potentially optimal care model for SCI includes primary care integration (Citation3).

The share of persons with SCI reporting unmet needs (12%) in this study was lower (19%) (Citation34) or similar (11%) (Citation21) to those previously reported. In comparison to the general population in the European Union (3%) (Citation29), the proportion of reported unmet needs was significantly larger, even in countries with the lowest unmet needs among persons with SCI (7% in Switzerland and Spain). This difference was especially large for Poland (persons with SCI: 25%, general population: 9%), Germany (13%, 1%), the Netherlands (12%, 1%), and Spain (7%, 0.3%) (Citation29). Even though these estimates may not be fully comparable across studies (Citation22), it showed that unmet healthcare needs are a common problem, especially for those with complex conditions such as SCI (Citation5, Citation10). Persons with SCI tend to use many different services with high frequency (Citation2). Throughout this process, they may find their needs to be less met.

Similar to the general population in Europe (Citation22, Citation56), the two most important reasons for not receiving healthcare services were related to service availability, including being denied a healthcare service. The methodology of InSCI did not allow to determine what the study participants meant by reporting being denied a service: the provider refused to make an appointment with them, made an appointment but redirected them to another provider, did not fulfill the expectations of the patient during the appointment, etc. Denied service could mean unacceptably long waiting time, untimely service provision, provider's decision not to provide the service because of, e.g. lack of adequate skills and equipment to deal with the request or due to their negative attitudes (Citation8, Citation10, Citation19).

The second most common reason for not receiving service was the service being absent (3%), which is a frequent access barrier for those living in rural areas or with long travel distances to the healthcare facilities (Citation25). Such lack of service availability might be reported about common health needs, e.g. pain management (Citation57), and services in which gaps are commonly identified, e.g. pain treatment, complementary therapies, and mental health (Citation10, Citation20). The other specific reasons for not getting access to a healthcare service were similar to the ones previously described in the literature: not being able to afford the service (Citation5, Citation12), inadequate skills of a healthcare provider (Citation12, Citation18), inadequate drugs or equipment of a healthcare provider (Citation16, Citation17), previous bad treatment possibly due to negative attitudes of the provider (Citation8, Citation19), or not being able to afford the cost of transportation (Citation10, Citation15). The inability to take time off to attend a service was reported by 0.4% of participants, which can be seen as an issue, particularly for those who are gainfully employed and have to balance employment with medical care (Citation22).

While females represent a “minority within a minority” (Citation58) among persons with SCI (27% in this study), we found that females (Citation20, Citation22) had higher odds of reporting unmet needs. Women were found to experience more access restrictions than the general population and men with SCI or disability (Citation6, Citation7). The healthcare needs of women with SCI differ from those of men (Citation59). On average, women with SCI tend to visit a broader range of providers and more frequently rely on primary and general settings (Citation2), which were often found to be less physically accessible than specialized settings (Citation17). In this study, compared to men, there was a slightly larger share of women reporting being denied a service, unable to afford a service, not knowing where to go to request a service, and not knowing if they were sick enough to seek one. Women were more likely than men to have problems finding a suitable service and paying for it as well as getting information about their own health status (Citation60, Citation61).

Being older (Citation1, Citation22) and healthier (Citation21, Citation22) were associated with lower odds of reporting unmet needs as well as reporting service unavailability, unaffordability and unacceptability. The association of having complex health issues and requiring more services, but facing restrictions accessing appropriate affordable care and being less satisfied, was well described in the literature (Citation21, Citation22). While Kim et al. (Citation5) found that older persons with SCI experience more access barriers, this study yielded an opposite finding. This could have multiple explanations. The participants in this study were mainly men, 53 years old on average. Older adults (Citation6), as well as men, might be less inclined to report unmet needs. Older persons with more years lived with SCI utilize more homecare and fewer medical services (Citation2) while having lower expectations and higher patient satisfaction (Citation1).

The limitations of this study are the following. The study used self-reported cross-sectional data. While an extensive number of reasons for not receiving healthcare were described, other reasons frequently mentioned in the literature were not included: difficulties obtaining information, waiting times, physical inaccessibility of medical facilities, and negative attitude of the healthcare providers. In this study, we could not distinguish between access to different services. Yet, the level of unmet needs might be different for various services. For example, the lack of service availability may be mainly reported about specific services, e.g. mental health, pain management, or complementary therapies (Citation10, Citation20). The survey data collection method (e.g. interview vs. survey) altered among participating countries (Citation41), which could have led to a potential bias. The sampling frames in most countries covered a specific region only and did not represent the entire country. In certain countries, the sampling setting was limited to rehabilitation facilities (Germany, the Netherlands, Norway) or acute or general hospitals (Spain). In countries using a convenient sampling strategy (France, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Romania and Spain), bias could result from self-selection and a lower chance for the participation of individuals experiencing more access restrictions. A relatively low response rate (32–42%) reflects that important segments of the target population – particularly those with unmet health needs – could be unequally represented in the participating countries. The majority (60%) of study participants belonged to the lowest three income deciles. Hence there may not have been enough variability to test the effect of income. Still, other predictors might be more important drivers of healthcare access, overriding the effect of income.

Conclusion

In all investigated countries, persons with chronic SCI face access barriers, especially with service availability. Stronger primary care for the general population was also associated with better service access for persons with SCI, which argues for further primary care strengthening.

Abbreviations

SCI: Spinal Cord Injury; InSCI: International Spinal Cord Injury Survey; LHS-SCI: International Learning Health System for Spinal Cord Injury Study; WHO: World Health Organization; ISPRM: International Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine; ISCoS: International Spinal Cord Society; SCI-SCS: Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Health Conditions Scale.

Disclaimer statements

Authors’ contributions Study conceptualization and development: O.B. and A.G., reviewed and supplemented by P.T., V.G., and A.J. Methodology: O.B. and A.G., reviewed and supplemented by P.T., V.G., and A.J. Data analysis and interpretation: O.B. in supervision by A.G. Writing: O.B. in supervision by A.G. reviewed and supplemented by P.T., V.G., and A.J. All the authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801076, through the SSPH+ Global PhD Fellowship Program in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School of Public Health. The other funds were provided by Swiss Paraplegic Research to fund two of the research positions of authors (O.B., A.G.).

Data availability statement The data that support the findings of this study are available from InSCI Study Group but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of InSCI Study Group.

Competing interest The authors declare no competing interest relevant to this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate Ethical approval was granted in each participating country based on their regulations. Each study participant signed an informed consent form. The InSCI Study Group approved the present study based on its protocol.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (39.8 KB)Acknowledgements

This study relies on the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI). The survey is part of the International Learning Health System for Spinal Cord Injury Study (LHS-SCI), which is embedded in the World Health Organization’s Global Disability Plan. LHS-SCI was launched in 2017 with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Society for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) and the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS). The members of the InSCI Steering Committee are: Julia Patrick Engkasan (ISPRM representative), James Middleton (ISCoS representative; Member Scientific Committee; Australia), Gerold Stucki (Chair Scientific Committee), Mirjam Brach (Representative Coordinating Institute), Jerome Bickenbach (Member Scientific Committee), Christine Fekete (Member Scientific Committee), Christine Thyrian (Representative Study Center), Linamara Battistella (Brazil), Jianan Li (China), Brigitte Perrouin-Verbe (France), Christoph Gutenbrunner (Member Scientific Committee; Germany), Christina-Anastasia Rapidi (Greece), Luh Karunia Wahyuni (Indonesia), Mauro Zampolini (Italy), Eiichi Saitoh (Japan), Bum Suk Lee (Korea), Alvydas Juocevicius (Lithuania), Nazirah Hasnan (Malaysia), Abderrazak Hajjioui (Morocco), Marcel W.M. Post (Member Scientific Committee; The Netherlands), Anne Catrine Martinsen (Norway), Piotr Tederko (Poland), Daiana Popa (Romania), Conran Joseph (South Africa), Mercè Avellanet (Spain), Michael Baumberger (Switzerland), Apichana Kovindha (Thailand), Reuben Escorpizo (Member Scientific Committee, USA). We would like to recognize the contribution of persons with SCI to the study and thank them for participation and sharing their experience in the InSCI survey.

References

- Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Essig S, Brach M, Münzel N, Gemperli A. Satisfaction with access and quality of healthcare services for people with spinal cord injury living in the community. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;43(1):111–121.

- Gemperli A, Brach M, Debecker I, Eriks-Hoogland I, Scheel-Sailer A, Ronca E. Utilization of health care providers by individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021;59(4):373–380.

- Ho C, Atchison K, Noonan VK, McKenzie N, Cadel L, Ganshorn H, Rivera JMB, Yousefi C, Guilcher SJT. Models of care delivery from rehabilitation to community for spinal cord injury: a scoping review. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(6):677–697.

- Chamberlain JD, Meier S, Mader L, von Groote PM, Brinkhof MW. Mortality and longevity after a spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(3):182–198.

- Kim J-G, Nam H, Hwang B, Shin H-I. Access to medical services in Korean people with spinal cord injury. Ann Rehabil Med. 2014;38(2):174–182.

- McColl MA, Jarzynowska A, Shortt S. Unmet health care needs of people with disabilities: population level evidence. Disabil Soc. 2010;25(2):205–218.

- Matin BK, Williamson HJ, Karyani AK, Rezaei S, Soofi M, Soltani S. Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: a systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):44.

- Lagu T, Haywood C, Reimold K, DeJong C, Walker Sterling R, Iezzoni LI. ‘I am not the doctor for you': physicians’ attitudes about caring for people with disabilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(10):1387–1395.

- Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Agaronnik ND, Donelan K, Lagu T, Campbell EG. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):297–306.

- Goodridge D, Rogers M, Klassen L, Jeffery B, Knox K, Rohatinsky N, Linassi G. Access to health and support services: perspectives of people living with a long-term traumatic spinal cord injury in rural and urban areas. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1401–1410.

- Alvarado JRV, Miranda-Cantellops N, Jackson SN, Felix ER. Access limitations and level of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in a geographically-limited sample of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2022;45(5):700–709.

- Godleski M, Jha A, Coll J. Exploring access to and satisfaction with health services. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2007;12(3):56–65.

- Hall AG, Karabukayeva A, Rainey C, Kelly RJ, Patterson J, Wade J, Feldman SS. Perspectives on life following a traumatic spinal cord injury. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(3):101067.

- Reinhardt JD, Middleton J, Bökel A, Kovindha A, Kyriakides A, Hajjioui A, Kouda K, Kujawa J. Environmental barriers experienced by people with spinal cord injury across 22 countries: results from a cross-sectional survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(12):2144–2156.

- Yang Y, Gong Z, Reinhardt JD, Xu G, Xu Z, Li J. Environmental barriers and participation restrictions in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury in Jiangsu and Sichuan provinces of China: results from a cross-sectional survey. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021:1–14.

- Lofters A, Chaudhry M, Slater M, Schuler A, Milligan J, Lee J, Guilcher SJT. Preventive care among primary care patients living with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42(6):702–708.

- Donnelly C, McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, O'Brien P, Savic G, Smith K. Utilization, access and satisfaction with primary care among people with spinal cord injuries: a comparison of three countries. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(1):25–36.

- Milligan J, Lee J, Hillier L, Slonim K, Craven C. Improving primary care for persons with spinal cord injury: development of a toolkit to guide care. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;43(3):364–373.

- Clemente KAP, Silva SVD, Vieira GI, Bortoli MC, Toma TS, Ramos VD, Brito CMM. Barriers to the access of people with disabilities to health services: a scoping review. Rev Saude Publica. 2022;56:64.

- Trezzini B, Brach M, Post M, Gemperli A. Prevalence of and factors associated with expressed and unmet service needs reported by persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(6):490–500.

- Gemperli A, Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Brach M, Trezzini B. Health care utilization in persons with spinal cord injury: part 1—outpatient services. Spinal Cord. 2017;55(9):823–827.

- Fjær E, Stornes P, Borisova L, McNamara C, Eikemo T. Subjective perceptions of unmet need for health care in Europe among social groups: findings from the European social survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:82–89.

- Hamilton R, Driver S, Noorani S, Callender L, Bennett M, Monden K. Utilization and access to healthcare services among community-dwelling people living with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40(3):321–328.

- Jorge A, White MD, Agarwal N. Outcomes in socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;29(6):680–686.

- Bell N, Kidanie T, Cai B, Krause J. Geographic variation in outpatient health care service utilization after spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(2):341–346.

- Neri MT, Kroll T. Understanding the consequences of access barriers to health care: experiences of adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(2):85–96.

- Borg D, Foster M, Legg M, Jones R, Kendall E, Fleming J, Geraghty TJ. The effect of health service use, unmet need, and service obstacles on quality of life and psychological well-being in the first year after discharge from spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(7):1162–1119.

- McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O, Smith ML. Socioeconomic status and access to healthcare: interrelated drivers for healthy aging. Front Public Health. 2020;8:231.

- Eurostat. Unmet health care needs statistics. Eurostat; 2021. [accessed 2021 Oct 18]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Unmet_health_care_needs_statistics&oldid=549203.

- Baeten R, Spasova S, Vanhercke B, Coster S. Inequalities in access to healthcare: a study of national policies 2018. Brussels: European Commission; 2018:70.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Realising the potential of primary health care. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2020:208.

- Atun R. What are the advantages and disadvantages of restructuring a health care system to be more focused on primary care services? London: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004:18.

- Kringos D, Boerma W, van der Zee J, Groenewegen P. Europe's strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Aff. 2013;32(4):686–694.

- Strøm V, Månum G, Arora M, Joseph C, Kyriakides A, Le Fort M, Osterthun R, Perrouin-Verbe B, Postma K, Middleton J. Physical health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury across 21 countries worldwide. J Rehabil Med. 2022;54:jrm00302.

- van Diemen T, Crul T, van Nes I, Geertzen JH, Post M. Associations between self-efficacy and secondary health conditions in people living with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2566–2577.

- Ho C. Primary care for persons with spinal cord injury — not a novel idea but still under-developed. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(5):500–503.

- Ong B, Wilson JR, Henzel MK. Management of the patient with chronic spinal cord injury. Med Clini North Am. 2020;104(2):263–278.

- European Spinal Cord Injury Federation. Policy statement on the treatment, rehabilitation and life-long care of persons with spinal cord injuries (SCI). European Spinal Cord Injury Federation (ESCIF). 2008. [accessed 2021 Oct 18]. http://www.escif.org/policy-statement/.

- Guilcher S, Craven B, Calzavara A, McColl MA, Jaglal S. Is the emergency department an appropriate substitute for primary care for persons with traumatic spinal cord injury? Spinal Cord. 2013;51(3):202–208.

- Dawkins B, Renwick C, Ensor T, Shinkins B, Jayne D, Meads D. What factors affect patients’ ability to access healthcare? An overview of systematic reviews. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(10):1177–1188.

- Gross-Hemmi M, Post M, Ehrmann C, Fekete C, Hasnan N, Middleton J, Reinhardt JD, Strøm V, Stucki G; InSCI Group. Study protocol of the international spinal cord injury (InSCI) community survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(2 Suppl. 1):S23–S34.

- Zampolini M, Stucki G, Giustini A, Negrini S. The individual rehabilitation project: a model to strengthen clinical rehabilitation in health systems worldwide. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;56(1):1–4.

- Bickenbach J, Batistella L, Gutenbrunner C, Middleton J, Post M, Stucki G. The International Spinal Cord Injury Survey: the way forward. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(12):2227–2232.

- Fekete C, Brach M, Ehrmann C, Post M; InSCI Group; Stucki G. Cohort profile of the International Spinal Cord Injury Community Survey implemented in 22 countries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(12):2103–2111.

- InSCI Country Reports. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(2):S61–S124.

- Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Hasvold T, Hutchinson A, Lember M, Oleszczyk M, Pavlic DR, Svab I, et al. The European primary care monitor: structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:81.

- Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Dedeu T, Hasvold T, Lember M, Oleszczyk M, Pavlic DR, Svab I, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(616):e742–e750.

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Survey (WHS): WHO multi-country studies data archive. [accessed 2021 Oct 18]. https://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/catalog/whs.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Model disability survey 2015. [accessed 2021 Oct 18]. https://www.who.int/disabilities/data/mds/en/.

- Penchansky R, Thomas J. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19:127–140.

- Levesque J-F, Harris M, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):1–9.

- UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO; 2011:84.

- Oña A, Strøm V, Lee B-S, Le Fort M, Middleton J, Gutenbrunner C, Pacheco Barzallo D. Health inequalities and income for people with spinal cord injury. A comparison between and within countries. SSM Pop Health. 2021;15:100854.

- Kalpakjian C, Scelza W, Forchheimer M, Toussaint L. Preliminary reliability and validity of a Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Conditions Scale. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(2):131–139.

- Touhami D, Essig S, Scheel-Sailer A, Gemperli A. Why do community-dwelling persons with spinal cord injury visit general practitioners: a cross-sectional study of reasons for encounter in Swiss general practice. J Multidiscipl Healthc. 2022;15:2041–2052.

- Palm W, Webb E, Hernández-Quevedo C, Scarpetti G, Lessof S, Siciliani L, van Ginneken E. Gaps in coverage and access in the European union. Health Policy. 2021;125(3):341–350.

- Rubinelli S, Glässel A, Brach M. From the person's perspective: perceived problems in functioning among individuals with spinal cord injury in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(2):235–243.

- Klebine P. Women’s health — spinal cord injury model system. [assessed 15 June 2022]. https://www.uab.edu/medicine/sci/daily-living/133-health/158-women-s-health.

- McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Lawson N, Savic G. Aging, gender, and spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(3):363–367.

- McColl MA, Aiken A, McColl A, Sakakibara B, Smith K. Primary care of people with spinal cord injury: scoping review. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(11):1207–1216.

- Hughes RB, Beers L, Robinson-Whelen S. Health information seeking by women with physical disabilities: a qualitative analysis. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(2):101268.