ABSTRACT

This mixed-methods study investigated a two-year community-based research program, Strong Beginnings for Babies (SBB), designed to support families in using 10 strategies for fostering infant language development. More specifically, the study focused on families of children slated to enter high-poverty schools at kindergarten entry or receiving Medicaid. The research employed Language Environment Analysis (LENA) digital language processors to record the vocalizations/verbalizations of 22 young children as well as those of the older children and adults who interacted with them. Three coaches were hired to work closely with participating families during a series of group sessions, model language promotion strategies, and review LENA reports with families. Analyses of 249 LENA recordings indicated increases in some measures of infants’ home language environments across the program period, particularly in Year One and for families whose initial LENA scores were low. However, there was great variability in the recordings data. The analysis of qualitative data sources, such as parent surveys and interviews with coaches, provided insights into the emotions elicited by LENA data, recording challenges, and additional supports that encouraged family progress.

Children’s brains rapidly develop during the first years of life, offering a key opportunity for nurturing cognitive and linguistic development (Shonkoff and Bales Citation2011; Shonkoff and Phillips Citation2000). Infants and toddlers who receive robust language stimulation from family members develop proficient language abilities. The opposite holds true as well; young children who receive minimal language stimulation tend to be delayed in language development (Bartl-Pokorny et al. Citation2013; Hart and Risley Citation1995; Hoff Citation2012; Petscher, Justice, and Hogan Citation2018; Romeo, Leonard, et al. Citation2018; Rowe Citation2012).

By as early as two years of age, there are significant disparities in the language development of children from low-income households as compared to that of their wealthier peers (Fernald, Marchman, and Weisleder Citation2013). There are long-term effects for children who experience delays in language development, including a negative impact on the process of learning to read and comprehend, and on attainment of academic success (Hoff Citation2012). Hemphill and Tivnan (Citation2008, 426) noted, “Children whose family incomes are at or below the poverty level are especially likely to struggle with reading, a pattern that emerges early and strengthens in the elementary years.”

The amount of talk a child receives, the number of interactions with adults, and the quality of these interactions have the potential to enhance language growth (Hirsh-Pasek et al. Citation2015; Ramírez et al. Citation2019; Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013). In their longitudinal study, Hirsh-Pasek et al. (Citation2015) advocated for language interventions that go beyond a focus on the number of words spoken in the household; rather, they encouraged a parent–child “conversational duet” (1082), sometimes referred to as the “serve and return process” (Shonkoff and Bales Citation2011, 23), to best support children’s language learning. Recently, however, Sperry, Sperry, and Miller (Citation2019a) took issue with interventions centered on promoting “conversational duets,” noting that exchanges of this nature are representative of the type of talk that takes place in affluent homes in the United States and may not be the norm in lower socioeconomic households nor across various cultures. Sperry and co-authors maintained that children from less affluent homes may learn to speak with other types of exposure to language, including bystander speech.

Regardless of the type of exposure, infants must receive language from others in order to learn language. Richards et al. (Citation2017) found that many parents thought they talked to their children more than they actually did. These researchers suggested that sharing objective data about the home language environment may be helpful in motivating and empowering families to participate in language interventions. Thus, a starting point is to objectively capture and measure the home verbal environment.

The Language Environment Analysis (LENA) Research Foundation has designed technology specifically for the purpose of measuring a child’s language environment. A small digital recording device, which fits in the pocket of a vest worn by a child, is turned on at the beginning of the day. This device runs for approximately 16 h, recording the verbalizations and vocalizations uttered within a six-foot radius of the child. After the recording episode, data from the device is uploaded to a cloud-based system. Using this data, LENA software generates reports with a series of bar graphs showing the adult word count, number of conversational turns (each turn represents one initiation and one response by either a child or an adult), and number of child vocalizations for each hour the child wore the recording device. The report also provides a set of bar graphs showing the percentile of adult words spoken near the child, conversational turns, and child vocalizations for the previous and most recent full-day recordings, based on normative data from LENA (Gilkerson and Richards Citation2008). Additionally, when families improve by 10% or more from the previous recording, or perform in the 75th percentile or higher in adult word count and/or conversational turns, they earn a star on the report. Accumulation of stars can be motivating for families (LENA Citation2019).

Gilkerson and Richards (Citation2008) described the initial data collection and analyses that were used in the norming process for the adult word count, conversational turn, and child vocalization percentiles that LENA system reports provide. More than 32,000 h of recorded speech data were used to determine the percentiles according to child age. LENA technology counts vocalizations rather than words and has been found to be reliable in languages other than English (e.g., Canault et al. Citation2016; Gilkerson et al. Citation2015), including Spanish (e.g., Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013; Wood, Diehm, and Callender Citation2016).

Several studies have utilized LENA technology (e.g., Ramírez et al. Citation2019; Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013; Zhang et al. Citation2015; Zimmerman et al. Citation2009). Gilkerson, Richards, and Topping (Citation2017) studied a parenting program that used LENA technology, language promotion videos (“talking tips,” 288), and interpretation of LENA reports by coaches. Significant increases in adult word count and conversational turns were found and sustained post-intervention for parents whose baseline scores were below the 50th percentile. Parents said that LENA reports, talking tips, and coaching — in that order — most influenced their behavior (Gilkerson, Richards, and Topping Citation2017). Similarly, Suskind and colleagues (2016) studied a language intervention for parents of children from socioeconomically diverse backgrounds using LENA technology and home visits by coaches. Coaches shared LENA reports and implemented a curriculum focused on language-promotion strategies. Results indicated that children’s home language environment measures improved in the short term (Suskind et al. Citation2016).

While the Suskind et al. (Citation2016) study focused on families from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, there is a paucity of research focusing solely on families in low-income households. Because children from less advantaged backgrounds are more likely to have language delays than their affluent peers (Fernald, Marchman, and Weisleder Citation2013), researchers in the current study decided to focus on this specific population.

The current study investigated a two-year community-based research program utilizing LENA technology. The program, Strong Beginnings for Babies (SBB), was designed to support families of infants in using strategies that help foster their children’s language development. More specifically, the program focused on families receiving Medicaid or whose children were slated to attend high-poverty schools at kindergarten entry.

Purpose

The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of SBB in increasing language interactions, as measured by LENA metrics, of families with infants in low-income households. (See Knight-McKenna, Hollingsworth, and Esposito CitationIn press for findings regarding families’ preferred language promotion strategies and Hollingsworth et al. Citation2020 for analyses of family and coach responses to SBB, including benefits, challenges, and areas for improvement.) The secondary purpose of this study was to examine qualitative data (e.g., parent surveys, interviews with coaches) to help us better understand the LENA metrics results. The following research question guided the current study: To what extent was this community-based research program effective in increasing LENA measures of infants’ home language environments?

Method

We utilized quantitative and qualitative approaches to answer the research question. Our participants and procedures are described below.

Participants

Participants in this study were 22 infants, 22 mothers,Footnote1 six fathers, and three coaches. To qualify for the study, families either received Medicaid or lived in an area in which their children were slated to attend a high-poverty school upon kindergarten entry. Thirteen (59%) of the infants were only children; the other nine (41%) had up to three older siblings. The majority of families and coaches reported their ethnicity as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, and the majority of families were bilingual in Spanish and English or were monolingual Spanish speakers. In general, participating fathers had completed a higher level of education than participating mothers, and mothers in Year Two were slightly more educated: Thirty-six percent of mothers in Year Two reported having at least some college, whereas only 18% of mothers in Year One had some college. Using a point system from one to seven (one = middle school, two = some high school, three = high school diploma, four = some college, five = associate’s degree, six = bachelor’s degree, seven = master’s degree), the mean level of education for the full sample was 2.95 (some high school); for Year One it was 2.91 (some high school); and for Year Two it was 3.00 (high school diploma). All of the coaches were female and spoke English fluently; two also spoke Spanish fluently. One coach was an elementary school teacher in a bilingual English-Spanish classroom, and the other two were currently or had previously been elementary school teacher assistants. The Spanish-speaking coaches attended and worked closely with families at every session. shows demographic characteristics of study participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

Procedures for recruitment, obtaining consent, and protecting confidentiality

The lead author recruited child and family participants for SBB via community contacts and organizations, including local pediatric practices, the county health department, the local housing authority, and a non-profit organization focused on health. Recruitment proved to be challenging, and referrals to SBB were few. Therefore, families who attended initial meetings were encouraged to bring neighbors and friends to SBB sessions and received gift cards for doing so. This helped to gradually increase enrollment in the project by word of mouth.

A rolling enrollment procedure was used throughout the first half of the program each year. After the 13 scheduled sessions were held in the first year of SBB, an additional five sessions were provided for families who had begun SBB later. These sessions were referred to as “SBB Onward and Upward.” Thus, a total of 18 sessions were held in Year One. For the second year of SBB, 15 sessions were scheduled and held.

At the first session each family attended, they were given details about the study and invited to participate. In consent conversations and documents, we paid particular attention to potential concerns about home language environment recordings and confidentiality. We assured families that there was no way to listen to recordings and that once LENA reports were generated, the recordings were erased. All families who attended chose to provide consent; however, for this study, we included data only from families who attended at least eight SBB sessions (M number of sessions attended per family = 12.2, SD = 2.8). Ten other families attended fewer than eight sessions; their data were not included. A university Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all names included in this paper are pseudonyms.

One coach was known to the researchers and was recruited and hired based on the researchers’ familiarity with her teaching expertise and bilingualism. The other two coaches were recruited and hired based on recommendations from the first coach and the principal of the school hosting the SBB sessions. All coaches were given details about the study and consented to participate. Coach development involved regular meetings with the lead author, who has expertise in early language and literacy. (See Knight-McKenna, Hollingsworth, and Esposito CitationIn press for additional details regarding coach preparation.)

Program components

Coaches worked closely with participating families during a series of group sessions held in the evenings at a centrally located Title I elementary school. Eleven families participated in the first year of the program, and 11 different families participated in the second year. Families initially attended four weekly sessions, then moved to two sessions per month during the academic year, with each gathering lasting approximately two hours. The first hour was a social event for families in SBB, with a simple dinner provided. The second hour was a coaching session during which the coaches met with two to four families to model 10 language promotion strategies (adapted for use with families from Gardner-Neblett and Gallagher Citation2013 and Suskind, Suskind, and Lewinter-Suskind Citation2015). Families received books and toys related to the demonstrated strategies and targeted to the current age of their infants. Volunteers provided child care for older siblings and infants as needed and preferred by families. There was no charge to families for participation in SBB.

Between sessions, families were asked to record their infants’ home language environment for one full day using LENA digital language processors. (Once turned on, these processors recorded for 16 h before turning off automatically.) Coaches reviewed LENA reports with families and supported family members in setting their own goals for their next recording day, all the while highlighting the potential of the home context for stimulating infant language development.

Data collection and instrumentation

Quantitative LENA recordings constituted the bulk of the data for this study. Qualitative data were also analyzed for information about the effectiveness of SBB in increasing language interactions in infants’ home environments. Finally, children’s language developmental level was assessed.

Home language environment recordings

Objective information about the home language environment was obtained from digital recordings using LENA’s (Citation2019) cloud-based automated analysis system, which reports specific metrics: adult word count, conversational turns, and child vocalizations. Eight to 15 recordings (M = 11.3, SD = 2.2), ranging in length from 10 to 16 h (M = 15.8, SD = 1.0) per recording were collected from each family throughout the SBB program. Of the original 289 recordings, 22 were deleted for being too short (less than 10 h), nine were deleted because they started too late in the day (after 6 pm), and nine were deleted for other reasons (e.g., a child’s date of birth was initially entered in the system incorrectly and LENA analyzes sounds related to speech based on a child’s age; a coach wrote on a LENA report that the child was at their grandmother’s house all day and the grandmother was not a participant in the study). These deletions yielded a total of 249 recordings for analysis.

Qualitative data about recordings

Five sources of qualitative data were collected and analyzed for information about the effectiveness of SBB in increasing language interactions in infants’ home environments: parent End-of-Year (EOY) surveys, notes on LENA reports, interviews with coaches, written coach notes, and agendas for coach meetings. Details about sources of qualitative data are provided in .

Table 2. Details about sources of qualitative data.

Child language developmental level

At the end of each year of SBB, data about children’s language skills were gathered from families using the LENA Snapshot (LENA Research Foundation Citation2016), a parent-friendly assessment of receptive and expressive language development in young children (Gilkerson, Richards, Greenwood, et al. Citation2017). Family members responded “yes” or “not yet” to a series of questions about their child’s language development (e.g., “Does your child produce two or more vowel sounds, such as /ah/ or /ooh/?”; LENA Citation2016). Families were asked to check “not yet” if the child was not yet consistently demonstrating the skill and to continue answering questions until they had five consecutive “not yet” answers. As noted earlier, recruitment was challenging, and a rolling enrollment procedure was used throughout the first half of the program each year. Since families joined the program at various times, and researchers and coaches asked families to complete the time-consuming consent paperwork at their initial session, we refrained from asking them to complete the LENA Snapshot upon program entry.

Data analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 to obtain descriptive statistics, especially means (M) and standard deviations (SD), to describe and summarize the quantitative recordings data for the full sample and then for each year separately. Individual families’ scores for adult word count, conversational turns, and child vocalizations across the program period were graphed using Excel. In addition, we conducted paired-samples t tests (two-tailed) to determine whether late recordings scores were higher than early scores (i.e., whether language interactions increased significantly). To do this, we computed an early-in-the-program composite score (hereafter referred to as “early score”) for adult word count, conversational turns, and child vocalizations for each family by averaging scores from their second, third, and fourth recordings.Footnote2 We also computed a late-in-the-program composite score (“late score”) for each child by averaging the scores from their last three recordings. Early and late scores were then compared using the t tests described above.

Following quantitative analysis, we examined the qualitative data for coach and family member responses to LENA reports and for their comments regarding the recording process and scores to help us understand the numeric results. The following section provides a detailed description of the qualitative analysis.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data

To begin, qualitative data were uploaded to Dedoose, a web-based application designed to support collaborative analysis of qualitative and mixed-methods research. Three researchers who participated in the design and implementation of the SBB program and one undergraduate research assistant who did not participate in its design or implementation conducted qualitative analyses as follows: One researcher completed the initial excerpting and coding of each type of data source (e.g., interviews with coaches), and one or more other members of the research team served as additional reviewers. Reviewers noted any disagreements or questions about excerpts and codes and brought them to research team meetings for resolution through discussion.

Using a thematic analysis approach, we excerpted chunks of the data relevant to our research question (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). We then generated initial codes for data extracts, often using participants’ own words, and this process resulted in a long list of codes (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014). As we recognized similarities across codes, we grouped those together under broader root codes. Conversely, codes that were too broad were divided into subcodes. For example, initially we had a very broad code for excerpts about LENA recordings. This was subsequently divided into two subcodes: (1) what went well in recordings and (2) what did not go well/challenges. The first subcode was further divided into categories, such as parents found a good day of the week to record (schedule solutions) and parents expressed pride in their scores (parent excitement/pride). The second subcode was also further divided (e.g., baby/parent was sick, user error/failure to record). As we organized codes into root and subcodes, we looked for semantic level themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) that would help us understand the ideas and meaning of participant responses relating to our research question (Guest, MacQueen, and Namey Citation2012). We returned often to our data to check relevant excerpts against the revised coding scheme and emerging themes in a constant comparative process (Creswell Citation2013), recoding as necessary. The research team held weekly meetings across several months for the purpose of coming to consensus on the codes and themes that emerged (Saldaña Citation2013) related to the SBB program and infants’ home language environments, and to select sufficient quotes to provide a rich account of the data and evidence for our interpretations (Brantlinger et al. Citation2005; Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Results

Analyses of LENA recordings indicated increases in some measured aspects of infants’ home language environments across the program period. However, there was great variability in the recordings data. LENA results are described in detail below, followed by results of qualitative analyses undertaken to help explain the recordings data. We close this section with child language developmental level results.

Home language environment recordings

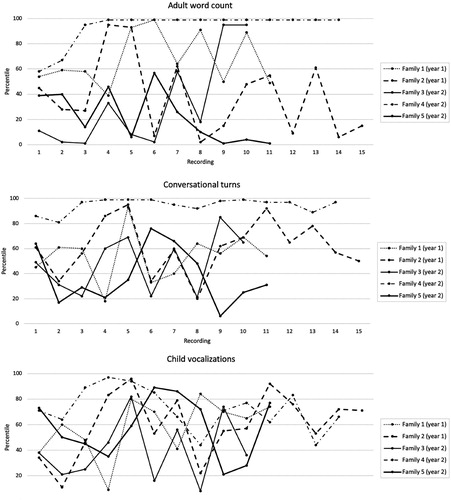

Means and standard deviations for LENA metrics (adult word count, conversational turns, and child vocalizations) were similar for the full sample and for each year, and are summarized in . The high standard deviations found for all LENA metrics provide an indication of the variability of the data. Based on visual inspection of the graphs of individual families’ LENA metrics over time, we did not find a consistent pattern of families’ initial scores being low and progressing in a linear trajectory upward over the course of the SBB program. A few families had infant language environment scores that started fairly high and generally stayed high, but most families’ scores showed multiple peaks and valleys during the SBB program period. Graphs of five families’ recordings data are provided as examples in .

Table 3. Summary of LENA recordings data and number of sessions attended.

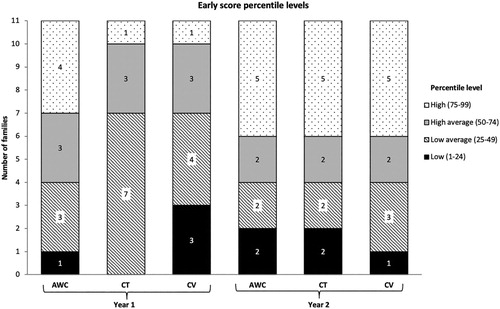

We then compared participants’ early and late program scores. Mean scores for conversational turns and child vocalizations were higher late in the program for the full sample, but results of paired-samples t tests (two-tailed) indicated these differences did not reach statistical significance. Participants in Year One began the program with lower scores than participants in Year Two. shows that more than half of the families in Year One had early conversational turns and child vocalizations scores at what LENA reports call a “low” (1st to 24th) or “low average” (25th to 49th) percentile level. By contrast, more than half of the families in Year Two had early scores for each metric at what LENA reports call a “high average” (50th to 74th) or “high” (75th to 99th) percentile level. Given that as a group, Year One participants’ early scores were lower than those of Year Two participants, we also analyzed each year separately.

Figure 2. Number of families with early scores at each percentile level for Year 1 and Year 2.

Note: AWC = adult word count; CT = conversational turns; CV = Child vocalizations.

Significant early to late score increases were found in Year One, but not in Year Two. Year One results are presented in , indicating that conversational turns were significantly higher late in the program (M early score = 265.33, SD = 93.91; M late score = 335.91, SD = 116.91; t[10] = 2.38, p < .05), as were child vocalizations (M early score = 911.94, SD = 424.66; M late score = 1256.55, SD = 408.24; t[10] = 3.95, p < .01). Adult word count did not increase significantly from early to late in the program for the full sample, Year One, or Year Two.

Table 4. Comparisons of early and late scores for Year 1.

We then analyzed early to late program differences for participants whose early scores fell at or below 50th percentile (approximately half of the full sample; n = 10 for adult word count, n = 11 for conversational turns, n = 11 for child vocalizations). Results are presented in , indicating that increases were approaching significance for conversational turns (p = .051) and child vocalizations (p = .052).

Table 5. Comparisons of early and late scores for participants starting at or below the 50th percentile (full sample).

Qualitative results relating to recordings

We examined the qualitative data for coach and family member responses to LENA reports and for their explanations about what did and did not go well with regard to the digital recording process and results. We also looked for information that could help explain the variability of scores as well as the lack of significant increase in early to late scores for Year Two and the full sample. The vast majority of this information was found in notes on LENA reports, interviews with coaches, and written coach notes (i.e., documented by coaches rather than families). In the following section, we present three main themes related to LENA recordings that emerged from the qualitative analysis: (1) LENA data elicited emotions, (2) Recording challenges, and (3) Additional supports encouraged family progress. In this section, “good scores” refer to scores that showed increases from previous reports, met set goals, or were already in the upper percentile levels. “Low scores” are those that showed decreases from previous reports, did not meet set goals, or were at low percentile levels.

LENA data elicited emotions

Review of LENA reports elicited positive emotions when scores were good and negative emotions when scores were low. Coaches and families were pleased with and proud of good scores. Conversely, they were frustrated and disappointed with low scores. We begin with responses to good scores, which were documented by all three coaches across both years of the program. Coaches frequently expressed their excitement and pride regarding families’ good scores. For example, Anita wrote:

[… I] went over the LENA reports. I was super happy with the increase that my families have shown in their LENA reports. Also, I was happy to see that all my families met their goal in the number of adult words. When it comes to number of conversational turns, Morena was the only one that met her goal but it was because her goal was more reasonable.

Concern about low scores was evident in expressions of disappointment or frustration, discussion of the variability of scores, coach encouragement for families to persevere, and family statements of commitment to improved scores. Many instances of disappointment or frustration regarding low scores were found in the data, although these were fewer in number than instances of pride and excitement (described above). Across both years of the program, all three coaches expressed their disappointment or frustration with low scores. One coach in particular discussed the variability of LENA scores that we described above in the LENA metrics results. Her notes on three LENA reports (earliest to latest) for one family included: (1) “Tiffany has made progress in her conversational turns. This recording is greatly improved. She went from 10% to 52%. She changed recording time. That made a huge difference,” (2) “Mother continues to be in the low percentiles. I am trying to reinforce the importance of the program,” and (3) “She improves, then the next score is way down.”

Documentation (by coaches) of parent disappointment was less frequent but nonetheless present in the data, as in these two excerpts: “We reviewed Eric’s latest recording results, and you could tell [Eric’s mother] was disappointed” and “When I shared with them the LENA report, they were sad, as well as I was, to see their reports.” Two coaches noted their concern that families were not talking with their infants as much as they thought they were (e.g., “She said that she talked to her baby a lot, but her scores told another story” and “We think that we talk a lot, but families learn that they need to talk more when they see the LENA report”).

All three coaches encouraged parents to persevere and reminded them of the importance of talking with their infants, getting a good recording, and aiming for higher scores (e.g., when one family scored at the 18th percentile for adult word count and 32nd percentile for conversational turns, the coach said, “I told [Charro’s] parents how this report indicated that more talking was needed”). Anita described encouraging one disappointed mother:

During the LENA reports, Olena was upset because her progress monitor showed a decrease. She was upset because she did not know what caused this decrease because she talked to Alonso the same or more than past occasions. I told her not to worry about it but instead to take the result as a motivation.

Recording challenges

Explanations given by coaches and families for low scores suggested how effortful it was for families to try to improve their LENA results. Reasons for low scores most frequently focused on families’ busy schedules and infants sleeping. Less common, but still present, were responses indicating that infant or parent illness, parent fatigue, or parent shyness interfered with increasing their scores. Finally, equipment-related issues were mentioned.

The qualitative data suggested that families’ busy home and work lives were obstacles to obtaining good LENA scores. All three coaches across both years of the program had excerpts about schedule challenges. For example, Anita noted: “Aliata’s mom’s scores are decreasing for the reasons that she is super busy with work, doctor appointments, and the fact that she is pregnant” and “Jorge shared that the day that they used the recorder they were busy doing other things so they did not talk to Aldo that much.” Petra described schedule challenges for one family in detail, along with her own takeaways from learning these details:

Arlo’s report has shown the lowest score in my group, so I wanted to have more information. Aldonza usually records around 10:00 but since she has the night shift, she said sometimes she is very tired. She takes long naps with the baby during the day because most of the time he is awake at night, and he sleeps a lot during the day. Aldonza also shared that things will change this upcoming week because her shift has changed so she will have more time to spend with the baby in the afternoon without being tired and sleepy. Having all this information was very powerful and necessary. Sometimes it is easy to assume that all families have a regular schedule. We decided to think about options for better results of the recording such as weekends, and also developing times during weekdays for the babies to be exposed to quality talking — after taking the naps, during bath time, while shopping for groceries, while changing the diaper, etc.

Rena mentioned that Veronica is sleeping more; that she wakes up early but during the day she goes back to sleep for around two hours in the morning and then some in the afternoon. She also mentioned that she is the only one that talks to Veronica most of the time because her husband gets home late. Her older sons do talk to her for a little bit but not a lot. She said that she is trying her best to talk to Veronica more.

The most common equipment-related issues were user errors, including failure to record. For example, “Mirella did not turn in the recorder because she could not find it” and

Rena shared that the reason that her scores are low is that she takes the vest off Veronica sometimes and puts it beside her. As a result, sometimes she forgets that she is recording so she leaves the vest with the recorder sitting in one place instead of carrying it with them to the other rooms.

The results described above relate to what did not go so well with the LENA recording process and results. We turn now to results relating to what went well with digital recordings.

Additional support encouraged family progress

Explanations for good scores often, though not always, noted solutions for when to conduct recordings. In addition, one coach credited the supports provided by the Onward and Upward sessions added at the end of Year One for increasing LENA scores. All three coaches documented solutions for when to record. For example, Petra wrote:

Bella is recording during the weekend so Dad can also be part of it. She said he talks a lot to the baby! This is the second report where their report is reaching new goals. Bella was very touched and emotional. She shared that since Juan was a premature baby, he has been behind in many of the milestones other kids reached at his age. However, she said language is definitely an area where he is not behind. She attributed it to the SBB program and all she has learned.

Petra noted another explanation for good scores: the five added coaching sessions at the end of Year One of the program (e.g., “I think these second round of sessions have had a positive impact on these two families and they feel more motivated to have better reports each week”). Petra further explained the benefits of these added coaching sessions for the parents and for her own coaching proficiency:

I think the success of Fina and Bella was possible due to the Onward and Upward sessions. I feel they just needed more time, more review, and a set of consecutive sessions to show growth in their reports. But above that, I feel these sessions helped me as a coach to understand and get to know more about each family’s dynamic and reflect on the expectations we set thinking that one size fits all. … We need to consider different situations and dynamics so we can provide parents with strategies, ideas, and plans that fit their needs and help them reach their goals.

Child language developmental level

Results of the LENA Snapshot at the end of each year indicated that, as a group, participating children were neither especially high nor especially low in language development. Means for percentile and standard score were in the average range (percentile M = 58.64, SD = 26.38; SS M = 104.10, SD = 7.86). provides descriptive details for Snapshot results. The Snapshot was not designed to detect language delays, though it has potential use in flagging children at risk for delays (Gilkerson, Richards, Greenwood, et al. Citation2017). At the end of the program only one participating child’s Developmental Quotient (100 × Development Age/Chronological Age) was below 77, the equal error rate threshold consistent with moderate delay as described by the latter researchers.

Table 6. End of year LENA snapshot results.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of SBB in increasing language interactions, as measured by LENA metrics, in infants’ low-income home environments, and to examine qualitative data sources for information to help explain the numeric results. Early-to-late scores for conversational turns and child vocalizations did increase for participants in Year One and for participants in the full sample whose scores were initially low (though the increases for the latter group did not strictly reach significance). Gilkerson, Richards, and Topping (Citation2017) similarly found that their intervention had a sustained positive impact on LENA scores only for those participants with fewer language interactions to begin with. Increases in child vocalizations would be expected as children develop and mature; thus, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the gains we found in child vocalizations may be attributed to the program.

The increases in conversational turns, however, may be especially important, as researchers, including neuroscientists, emphasize their centrality in early brain development. For example, independent of socioeconomic status and adult word count, children exposed to more conversational turns had higher white matter connectivity (Romeo, Segaran, et al. Citation2018). Moreover, it was the increased brain activation associated with conversational turns “that significantly explained the relation between children’s language exposure and verbal skill” (Romeo, Leonard, et al. Citation2018, 700).

Results for the full sample and for participants in Year Two differed from those described above. Rather than seeing a steady increase, results overall pointed to tremendous variability within and across families’ language environment scores throughout the program, and some families started with and maintained fairly high scores. Families who experienced high scores likely already had infant language stimulation strategies in place.

Although socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with many measures of children’s language skills, trajectories for linguistic growth are not determined solely by children’s economic circumstances. There is considerable variation in language exposure within SES groups, with some high-SES children experiencing a paucity of language exposure and some low-SES children experiencing high language exposure (Romeo, Leonard, et al. Citation2018; Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013). This is consistent with Gilkerson, Richards, Warren et al.’s (Citation2017) findings that some families from low-income backgrounds did not need the language stimulation interventions. Indeed, one explanation for the significant increases in Year One but not in Year Two of our study may be the fact that more Year Two families started with fairly high scores compared to Year One families (as illustrated in ). Some families may have chosen to participate because they had heightened knowledge of or interest in their children’s language development and had many language stimulation strategies already in place.

Alternatively, some families’ higher scores noted at the beginning of the program may have been due to the novelty of the intervention, as well as a possible halo effect. Parents were excited and more focused at the beginning of the program, with other activities and responsibilities taking priority later in the program. The Onward and Upward sessions at the end of Year One seemed especially impactful for the families who participated, especially from the coaches’ perspectives. These sessions appeared to motivate families to try for higher scores. Perhaps as coaches came to know families better, they were able to provide more targeted supports, which allowed families to make greater gains. One coach in particular noted her interest in tailoring coaching to families’ specific needs.

We went into this project anticipating that once parents learned about the benefits of attending to their babies’ language growth, they would give top priority to improving their LENA scores. We found that this was not necessarily the case, as parents were pulled to other life responsibilities. Both researchers and coaches found it challenging to respond to fluctuating parental submission of LENA recordings. This is in line with Suskind et al. (Citation2016), who found that their LENA intervention was successful in increasing both parent knowledge about the importance of language input and parent language input behavior (improved adult word count, conversational turns, child vocalizations), but that the behavior was not sustained post-intervention.

Given the importance of in-home language stimulation as a foundation for later literacy learning and academic success in the United States (Hemphill and Tivnan Citation2008), coaches and researchers searched for the most effective ways to support families in maintaining their best infant language stimulation efforts, as measured by LENA metrics. We were not successful in finding effective methods for every family. It is possible that cultural differences played a role in the communication and adoption of program goals and strategies. As Sperry, Sperry, and Miller (Citation2019b, 1304) asserted, “The practice of talking to the child in dyadic interaction is socioculturally defined … [and] does not exist in many cultures.”

Although recording seemed straightforward to researchers and coaches, it was actually difficult for families to implement on a regular basis. In the end, finding an ideal and consistent time to record was very challenging. Scheduling conflicts, family illness, infant sleep patterns, and busyness in general were frequent obstacles to families being able to submit useful recordings. Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative results revealed that stimulating infant language, as measured by LENA scores, was an effortful endeavor for families, and their success in doing so fluctuated depending upon a number of different life circumstances.

Limitations and future research

We selected appropriate participants to address the research question, examined multiple sources of data, involved several researchers in analyses, analyzed results systematically, and included quotes from participants to illustrate conclusions. All of these factors are indicators of quality and credibility within research involving qualitative data (Brantlinger et al. Citation2005). However, it is important to acknowledge that our sample size was small, and future researchers may wish to study a similar program with more participants to obtain a broader and deeper understanding of the impact of similar interventions on home language environments. Another limitation was that we did not administer the LENA Snapshot prior to SBB. Baseline, during, and end of program Snapshot measures would have allowed us to document any gains in child language developmental level across the program period.

We recommend that future researchers also obtain two or more baseline recordings before beginning a similar program, in order to determine which participants might benefit most. Consistent with other research (Gilkerson, Richards, Warren et al. Citation2017; Romeo, Leonard, et al. Citation2018; Sperry, Sperry, and Miller Citation2019b; Weisleder and Fernald Citation2013), we found striking variability in home language environment measures within a group of families from less advantaged backgrounds, reinforcing that not all families from low-income neighborhoods need language stimulation interventions. Families could be surveyed for their interest and knowledge levels prior to similar interventions and their self-reported use of language stimulation strategies in order to determine baseline interest, knowledge, and skill levels. Future research should also address the issue of determining the number of coaching sessions for obtaining optimal results.

Future research could also examine ways to address time constraints, commitment, follow-through, and other challenges for participants aiming to provide consistent language stimulation at home. For example, another round of coaching sessions (similar to Onward and Upward) or home visits could support families who face time constraints or other challenges to attending program sessions. Future research could also focus on other potential benefits for participants, such as community support, connections, and parental validation. Cultural differences should be carefully considered in future research, with attention paid to how and which recommended home language stimulation strategies are shared with families. Finally, future research could consider child vocalization and conversational turn differences based on gender.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of SBB in increasing language interactions, as measured by LENA metrics, of families with infants in low-income households. Results point to some gains but also to great variability in assessed LENA metrics overall and suggest only modest effects of the program. Coaches and families documented numerous obstacles to improving LENA scores, including busyness, infants sleeping during the day, illness in the family, parent fatigue, shy personalities, and equipment failures. Stimulating infant language to improve LENA metrics appeared to be effortful for families in this study, and they experienced fluctuating success in doing so, depending upon their life circumstances.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Mary Knight-McKenna, PhD, is an associate professor of education and director of the M.Ed. program at Elon University. Her research interests include preventing reading difficulties and fostering partnerships between families of diverse backgrounds and teacher candidates in academic service-learning settings.

Heidi L. Hollingsworth, PhD, is an associate professor of education and program coordinator for early childhood at Elon University. Her research interests include partnering with families in early childhood contexts, children’s early math and science concepts, and personnel preparation — particularly preparation involving academic service-learning and/or study abroad experiences.

Judy Esposito, PhD, is an associate professor of human service studies at Elon University. A licensed professional counselor and former school counselor, Dr. Esposito specializes in clinical supervision, empathy development, and play therapy with children and families.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper we include in the “mother” category one biological grandmother who was raising the infant.

2 The first recording yielded atypically high counts for several children, possibly due to the novelty of the recording experience and equipment. Scores fell to more typical levels in subsequent recordings. Therefore, the first recording was not included in the computation of early scores.

References

- Bartl-Pokorny, K. D., B. Marschik, S. Sachse, V. A. Green, D. Zhang, L. Van Der Meer, T. Wolin, and C. Einspieler. 2013. “Tracking Development from Early Speech-Language Acquisition to Reading Skills at Age 13.” Developmental Neurorehabilitation 16: 188–195. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2013.773101

- Brantlinger, E., R. Jimenez, J. Klingner, M. Pugach, and V. Richardson. 2005. “Qualitative Studies in Special Education.” Exceptional Children 71: 195–207. doi: 10.1177/001440290507100205

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Canault, M., M. T. LeNormand, S. Foudil, N. Loundon, and H. Thai-Van. 2016. “Reliability of the Language Environment Analysis System (LENA™) in European French.” Behavior Research Methods 48: 1109–1124. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0634-8

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Fernald, A., V. A. Marchman, and A. Weisleder. 2013. “SES Differences in Language Processing Skill and Vocabulary are Evident at 18 Months.” Developmental Science 16: 234–248. doi:10.1111/desc.1201Fernal9 doi: 10.1111/desc.12019

- Gardner-Neblett, N., and K. C. Gallagher. 2013. More Than Baby Talk: 10 Ways to Promote the Language and Communication Skills of Infants and Toddlers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute.

- Gilkerson, J., and J. A. Richards. 2008. The LENA Natural Language Study (Technical Report LTR-02-2). Boulder: LENA Foundation.

- Gilkerson, J., J. A. Richards, C. R. Greenwood, and J. K. Montgomery. 2017. “Language Assessment in a Snap: Monitoring Progress up to 36 Months.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 33: 99–115. doi:10.1177/0265659016660599.

- Gilkerson, J., J. A. Richards, and K. Topping. 2017. “Evaluation of a LENA-Based Online Intervention for Parents of Young Children.” Journal of Early Intervention 39: 281–298. doi:10.1177/1053815117718490.

- Gilkerson, J., J. A. Richards, S. F. Warren, J. K. Montgomery, C. R. Greenwood, D. Kimbrough Oller, J. H. L. Hansen, and T. D. Paul. 2017. “Mapping the Early Language Environment Using All-Day Recordings and Automated Analysis.” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 26 (2): 248–265. doi:10.1044/2016_AJSLP-15-0169.

- Gilkerson, J., Y. Zhang, D. Xu, J. A. Richards, X. Xu, F. Jiang, J. Harnsberger, and K. Topping. 2015. “Evaluating Language Environment Analysis System Performance for Chinese: A Pilot Study in Shanghai.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 58: 445–452. doi:10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-14-0014.

- Guest, G., K. M. MacQueen, and E. E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Hart, B., and T. R. Risley. 1995. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Baltimore: Brookes.

- Hemphill, L., and T. Tivnan. 2008. “The Importance of Early Vocabulary for Literacy Achievement in High-Poverty Schools.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 13: 426–451. doi:10.1080/10824660802427710.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., L. B. Adamson, R. Bakeman, M. T. Owen, R. M. Golinkoff, A. Pace, P. K. Yust, and K. Suma. 2015. “The Contribution of Early Communication Quality to Low-Income Children’s Language Success.” Psychological Science 26: 1071–1083. doi:10.1177/0956797615581493.

- Hoff, E. 2012. “Interpreting the Early Language Trajectories of Children from Low-SES and Language Minority Homes: Implications for Closing Achievement Gaps.” Developmental Psychology 49: 4–14. doi:10.1037/a0027238.

- Hollingsworth, H. L., M. Knight-McKenna, J. Esposito, and C. Redd. 2020. “Family and Coach Responses to a Program for Fostering Infant Language.” Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

- Knight-McKenna, M., H. L. Hollingsworth, and J. Esposito. In press. “Infant Language Stimulation: A Mixed-Methods Study of Families’ Preference for and Use of Ten Strategies.” Early Child Development and Care.

- LENA Research Foundation. 2016. LENA Snapshot. Boulder: LENA Research Foundation.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Petscher, Y., L. M. Justice, and T. Hogan. 2018. “Modeling the Early Language Trajectory of Language Development When the Measures Change and Its Relation to Poor Reading Comprehension.” Child Development 89: 2136–2156. doi:10.1111/cdev.12880.

- Ramírez, N. F., S. R. Lytle, M. Fish, and P. K. Kuhl. 2019. “Parent Coaching at 6 and 10 Months Improves Language Outcomes at 14 Months: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Developmental Science 22: 1–14. doi:10.1111/desc.12762.

- Richards, J. A., J. Gilkerson, D. Xu, and K. Topping. 2017. “How Much Do Parents Think They Talk to Their Child?” Journal of Early Intervention 39: 163–179. doi:10.1177/1053815117714567.

- Romeo, R. R., J. A. Leonard, S. T. Robinson, M. R. West, A. P. Mackey, M. L. Rowe, and J. D. E. Gabrieli. 2018. “Beyond the 30-Million-Word Gap: Children’s Conversational Exposure is Associated with Language-Related Brain Function.” Psychological Science 29 (5): 700–710. doi:10.1177/0956797617742725.

- Romeo, R. R., J. Segaran, J. A. Leonard, S. T. Robinson, M. R. West, A. P. Mackey, A. Yendiki, M. L. Rowe, and J. D. E. Gabrieli. 2018. “Language Exposure Relates to Structural Neural Connectivity in Childhood.” The Journal of Neuroscience 38: 7870–7877. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0484-18.2018.

- Rowe, M. L. 2012. “A Longitudinal Investigation of the Role of Quantity and Quality of Child-Directed Speech in Vocabulary Development.” Child Development 83: 1762–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01805.x

- Saldaña, J. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Shonkoff, J. P., and S. N. Bales. 2011. “Science Does Not Speak for Itself: Translating Child Development Research for the Public and Its Policymakers.” Child Development 82: 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01538.x.

- Shonkoff, J. P., and D. A. Phillips, eds. 2000. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Sperry, D. E., L. L. Sperry, and P. J. Miller. 2019a. “Language Does Matter: But There Is More to Language Than Vocabulary and Directed Speech.” Child Development 90: 993–997. doi:10.1111/cdev.13125.

- Sperry, D. E., L. L. Sperry, and P. J. Miller. 2019b. “Reexamining the Verbal Environments of Children from Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds.” Child Development 90: 1303–1318. doi:10.1111/cdev.13072.

- Suskind, D. L., K. R. Leffel, E. Graf, M. W. Hernandez, E. A. Gunderson, S. G. Sapolich, E. Suskind, L. Leininger, S. Goldin-Meadow, and S. C. Levine. 2016. “A Parent-Directed Language Intervention for Children of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study.” Journal of Child Language 43: 366–406. doi:10.1017/S0305000915000033.

- Suskind, D., B. Suskind, and L. Lewinter-Suskind. 2015. Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain: Tune in, Talk More, Take Turns. New York: Dutton.

- Weisleder, A., and A. Fernald. 2013. “Talking to Children Matters: Early Language Experience Strengthens Processing and Builds Vocabulary.” Psychological Science 24: 2143–2152. doi:10.1177/0956797613488145.

- Wood, C., E. A. Diehm, and F. Callender. 2016. “An Investigation of Language Environment Analysis Measures for Spanish-English Bilingual Preschoolers from Migrant Low-Socioeconomic-Status Backgrounds.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 47: 123–134. doi:10.1044/2015_LSHSS-14-0115.

- Zhang, Y., X. Xu, F. Jiang, J. Gilkerson, D. Xu, J. A. Richards, J. Harnsberger, and K. J. Topping. 2015. “Effects of Quantitative Linguistic Feedback to Caregivers of Young Children: A Pilot Study in China.” Communication Disorders Quarterly 37: 16–24. doi:10.1177/1525740115575771.

- Zimmerman, F. J., J. Gilkerson, J. A. Richards, D. A. Christakis, D. Xu, S. Gray, and U. Yapanel. 2009. “Teaching by Listening: The Importance of Adult-Child Conversations to Language Development.” Pediatrics 124: 342–349. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2267.