Abstract

Objectives. This study aimed to describe work-, lifestyle-, and health-related factors among ambulance personnel, and to analyse differences between women and men. Methods. The cross-sectional study (N = 106) included self-reported and objective measures of work, lifestyle, and health in 10 Swedish ambulance stations. The data collection comprised clinical health examination, blood samples, tests of physical capacity, and questionnaires. Results. A high proportion of the ambulance personnel reported heavy lifting, risk of accidents, threats and violence at work. A low level of smoking and alcohol use, and a high level of leisure-time physical activity were reported. The ambulance personnel had, on average, good self-rated health, high work ability and high physical capacity. However, the results also showed high proportions with risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), e.g., high blood pressure, and high levels of blood lipids. More women than men reported high work demands. Furthermore, women performed better in tests of physical capacity and had a lower level of CVD risk factors. Conclusions. Exposure to work-related factors that might affect health was common among ambulance personnel. Lifestyle- and health-related factors were somewhat contradictory, with a low proportion reporting lifestyle-related risk factors, but a high proportion having risk factors for CVD.

1. Introduction

Ambulance personnel are exposed to several factors, both work- and lifestyle-related, that might affect their health [Citation1]. Moreover, the proportion of women is increasing in the emergency medical services (EMS) [Citation2]. It is therefore of interest to understand whether work, lifestyle and health differ between female and male ambulance personnel. Work-related factors in the EMS potentially affecting health include shift work, heavy work, work in awkward positions and a lot of sedentary time in the ambulances [Citation1]. Stress during work is another work-related factor in the EMS. Stress could be related to critical incidents during patient care, but could also be of a more chronic nature, e.g., due to lack of support from superiors and colleagues, or poor communication [Citation3]. Increased risk of threats and violence during emergency assignments has been reported [Citation4]. Furthermore, an increased number of emergency assignments per work shift, with basically the same resources [Citation5,Citation6], has decreased the possibilities for recovery between assignments.

The unpredictable work, shift work and long working hours could affect food habits among EMS personnel [Citation7]. Furthermore, leisure-time physical activity, a well-known preventive factor against ill-health [Citation8], might also be affected by work-related factors such as shift work and long working hours. Betlehem et al. [Citation9] found lack of time to be the main reason why ambulance personnel did not perform leisure-time physical activity. Another lifestyle factor of interest is alcohol use, where an association has been found between high alcohol use and high levels of stress among ambulance personnel [Citation10].

Even though there are several work- and lifestyle-related factors that might affect the health of ambulance personnel, few studies have been conducted to describe work-, lifestyle-, and health-related factors in more detail for this group. One of these studies observed that 9 out of 10 ambulance personnel had at least one risk factor for CVD [Citation11]. Furthermore, in a Swedish register-based study, higher risk for CVD and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) was found among ambulance personnel compared to other professions [Citation12]. Other studies show that heavy physical work in combination with insufficient physical capacity is associated with increased risk for MSDs among ambulance personnel [Citation13,Citation14]. Associations between the psychosocial work environment and risk of impaired health have also been reported [Citation15]. Moreover, factors such as demand, control, support and different strategies used by the ambulance personnel are important for how they handle stress and anxiety [Citation16].

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been identified aiming at comparing work-, lifestyle-, and health-related factors between women and men working in the EMS. However, one study has observed an association between high physical demands and neck shoulder complaints among female ambulance personnel, with a proposed explanation being lower physical capacity among women compared to men, but also that the equipment and the ambulances are customized for men to a higher degree [Citation17].

Due to the lack of knowledge regarding the overall picture of work, lifestyle, and health among women and men in the EMS, the aim of the present study was to describe work-, lifestyle-, and health-related factors among ambulance personnel, and to analyse differences between women and men.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted with the EMS of a county in the south of Sweden. The data collection was conducted between February and August 2017, including both self-reported and objective measures of work, lifestyle and health. The EMS included 10 ambulance stations in total, organized into three divisions based on geographical location. In 2017, it consisted of approximately 170 employees, of whom 70% were registered nurses (RNs) and 30% were emergency medical technicians (EMTs). There were small differences regarding the number of employees in the three divisions (n = 49 in the smallest and n = 68 in the largest division). The population served by this EMS was about 350,000, with a population density of 34 people per km2. In 2016, when the project was initiated, the number of emergency calls in the EMS was 45,600 [Citation18].

2.2. Participants and data collection

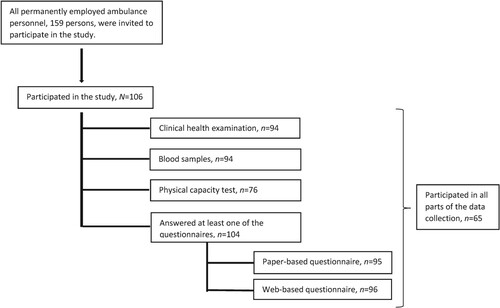

All permanently employed RNs and EMTs working with patient care, 159 persons, were invited to participate in the study. Managers and administrative personnel were excluded. In total, 106 ambulance personnel (36 women and 70 men) participated, resulting in a response rate of 67%. The response rate was higher for women than for men (77% vs 63%) and higher for RNs than for EMTs (79% vs 33%). The response rate in the divisions ranged from 61 to 73%. The data collection consisted of several parts: clinical health examination, blood samples, tests of physical capacity, and questionnaires. Since not all participants took part in all parts of the data collection, the total number of participants differs between the different parts (Figure ).

2.3. Clinical health examination and blood samples

The clinical health examination was conducted at the occupational health services in each of the three divisions. The examination was done by occupational health nurses with long experience, and included measurements of blood pressure, height, weight, waist, and hip circumference. Blood samples, to measure blood lipids, were drawn at the hospital laboratory, a few days before the clinical examination. Details regarding the included measurements and the categorization are available in the Supplemental material.

2.4. Test of physical capacity

The test of physical capacity was conducted by four ambulance personnel within the organization – the same group is also responsible for the test of physical capacity that is routinely carried out when recruiting new employees. The test included aerobic capacity, muscular strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility. This combination of tests has previously been used to evaluate physical capacity among employees in demanding occupations in general [Citation19] and in ambulance work specifically [Citation20]. Details about the included tests and the categorization are available in the Supplemental material.

2.5. Questionnaires

Two questionnaires were used, one paper-based and one web-based. The paper-based questionnaire was a standard questionnaire used by the actual occupational health service, while the web-based questionnaire was composed for this study and consisted of validated questionnaires regarding the work environment, lifestyle, and health.

Work-related factors were assessed using questions regarding the work schedule, physical demands [Citation21], risk for accidents, worries about threats and violence, psychosocial work demands, control, and support [Citation22], work stress in general, and over-commitment [Citation23]. Lifestyle-related factors were assessed regarding leisure-time physical activity, smoking and tobacco use, alcohol use [Citation24], possibility to engage in leisure activities, balance between activities in everyday life [Citation25], rest and recovery from work [Citation26], and core symptoms of insomnia [Citation27]. Health-related factors were assessed using one general question regarding self-rated health, the work ability index (WAI) [Citation28], including questions regarding self-reported diseases or health issues. Details regarding the included questionnaires and the categorization are available in the Supplemental material.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Results are presented as total numbers and proportions, or means and standard deviations, within the total sample and the sub-groups of women and men. Two-sided t tests, χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to identify statistically significant differences between women and men. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

When analysing the questions regarding rest and recovery from work, a principal component analysis with varimax rotation was performed. Three components were derived: recovery (five items); fatigue (four items); and sleep problems and worries (four items), which explained 65.5% of the variance. The question ‘do you feel energetic during a working day?’ was excluded since it loaded in all three components.

In a few cases, similar questions were included in both the paper-based and the web-based questionnaire. In the case of inconsistency between answers, the answer from the paper-based questionnaire was chosen. Missing data are not reported separately; instead, the total of valid responses for each item or measurement is presented in the results. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.

3. Results

The background characteristics of the study population regarding age, occupation, work schedule and living conditions are presented in Table . The mean age was 47.8 years and did not differ between men and women. The number of years working in EMS ranged from 1 to 39 years (M 17.5 years), with more years among men than women (19.7 years vs 13.8 years, p = 0.004). Two-thirds of the participants were working 24-h shifts and one-third were alternating 24-h shifts with day and night shifts. About one-third of the participants had other work alongside the full-time ambulance work.

Table 1. Background characteristics of the participating ambulance personnel.

3.1. Work-related factors

Self-reported data on work-related factors are presented in Table . A high proportion (80%) of the participants reported satisfaction with their work schedule, with no statistically significant difference between women and men. Physically demanding work more than half of the time was reported by 30% of the participants. Furthermore, almost 70% reported that heavy lifting was included in more than half of their work time, and more than 60% reported that more than half of their work time was performed in awkward or bending positions. A higher proportion of women reported high work demands in all these three aspects, with statistically significant differences regarding physical demands (43% vs 22%, p = 0.029) and awkward or bending positions (77% vs 55%, p = 0.031). High risks for accidents were reported by 60% of the participants. Approximately half of the participants reported sometimes or often being worried about threats and violence, and to have received threats during the last year. The proportions were higher among women than men both regarding worries about threats and violence (58% vs 38%, p = 0.050) and to have received threats (66% vs 37%, p = 0.010). High psychosocial work demands were reported by 28%, with statistically significant higher levels among women (41% vs 20%, p = 0.027). Almost 80% experienced work stress at least sometimes, and high over-commitment was reported by 37% of the participants.

. Self-reported work, lifestyle and health among the participating ambulance personnel.

3.2. Lifestyle-related factors

Moderate and vigorous leisure-time physical activity was reported by 75% of the participants (Table ), and no one reported sedentary activity during leisure time. The proportion of those smoking was 2% and the use of Scandinavian moist smokeless tobacco was reported by 10% of the participants, with no statistically significant differences between women and men. Fewer than one-third agreed that their work schedule allowed engagement in leisure activities. More than one-third reported that they did not feel enough recovery and the same number reported a high level of fatigue. Almost 50% reported a high level of sleep problems and worries, with a higher proportion among women than men (60% vs 39%, p = 0.048). The proportion of insomnia was 21%, with no significant difference between women and men.

3.3. Health-related factors

Self-reported data on health-related factors are presented in Table . The mean self-rated health was 7.5 on a 10-point scale, where 10 implies best possible health, and the mean WAI was 42.2 on a scale where 44–49 implies very good work ability. There were no differences between men and women regarding self-rated health or WAI. More than one out of four reported MSDs, while 18% reported CVD and 16% reported mental health issues. There were no differences between women and men except for mental health issues, where women more frequently reported mental health issues than men (29% vs 8%, p = 0.008).

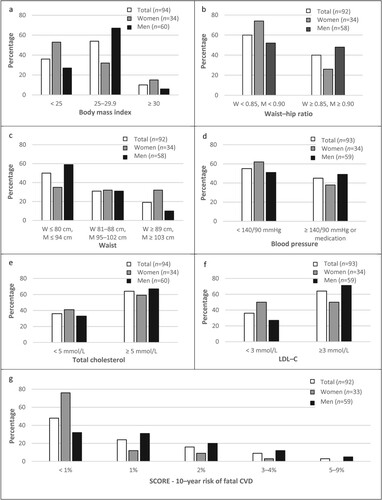

The results from the clinical health examination and blood samples are presented in Figure . Almost 65% of the participants were overweight or obese based on body mass index (BMI), with a lower proportion among women than men (47% vs 73%, p = 0.005). When measuring waist circumference, half of the participants were classified as having increased or substantially increased risk of metabolic complications, with a higher proportion among women than men (64% vs 41%, p = 0.019). According to the waist–hip ratio, 40% had abdominal obesity, with a lower proportion among women than men (26% vs 48%, p = 0.049). The proportion of high blood pressure was 45% among the participants. No statistically significant differences were noticed between women and men regarding blood pressure or total cholesterol. Almost two out of three had high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), with a lower proportion among women than men (50% vs 73%, p = 0.026). There was also a statistically significant difference regarding the 10-year risk of fatal CVD (systematic coronary risk estimation [SCORE]) between women and men, with lower risk levels for women. Almost half of the participants had the lowest risk (<1%) according to SCORE. Among the low-risk participants, there was a statistically significant higher proportion of women than men (76% vs 32%, p = 0.002).

Figure 2. (a)–(g) Proportions (%) regarding anthropometric measures, blood pressure, blood lipids and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among the participating ambulance personnel (n = 92–94). Note: LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; M = men; n = number of participants in a subsample; SCORE = systematic coronary risk estimation; W = women.

The results of the test of physical capacity are presented in Table . Women performed better than men in four of the six included tests, with better results in rowing (30% vs 4% with good or excellent results, p = 0.013), hand strength (78% vs 39% with strength of the right hand over average, p = 0.002) and the sit and reach test (12 cm vs 5 cm, p < 0.001). There was no difference among women and men regarding the lift test. In the 2-min back extension endurance test, the proportion managing the test was slightly higher among men than among women, but the difference was not statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Table 3. Physical capacity among the participating ambulance personnel.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to describe a broad range of work, lifestyle and health-related factors among ambulance personnel, and to analyse potential differences between women and men in this occupation. Few, if any, previous studies on work and health among ambulance personnel have included such extensive data based on both self-report and objective measures, and, to the best of our knowledge, none have analysed differences between women and men. The results from this study indicate that the ambulance personnel are exposed to many different work demands, both physical, e.g., heavy lifting, and psychosocial, e.g., risk of accidents, threats and violence. The clinical health examination revealed a high proportion with risk factors for CVD, e.g., high blood pressure and overweight. However, at the same time, the ambulance personnel reported high self-rated health, high WAI, high level of leisure-time physical activity and high physical capacity.

Despite the high work demands in the EMS, the ambulance personnel in this study had been working for many years in the same workplace (M 17.5 years). There are several possible reasons for this, but one could be that the work includes many rewarding elements, e.g., a high degree of variation and autonomy, but also the satisfaction of being able to assist people in need [Citation29]. The finding that women in this study had been working fewer years in the EMS than their male colleagues might be because, historically, more men than women have worked in the EMS. Even though the difference today is smaller, there are still more men than women working in the EMS, both in Sweden [Citation30] and in other countries [Citation2]. Another possible explanation could be that women leave the occupation to a higher degree than their male colleagues due to physical demands, or difficulties to combine the work with family life.

Almost one out of three of the ambulance personnel reported having other work alongside the full-time work in the EMS. One possible explanation for this is the 24-h shifts, which concentrates the work hours into a few days during the week, and thereby makes it possible to have other work outside the EMS. Similar results have been observed previously, and also associations between additional work and an increased risk of dissatisfaction at work [Citation31]. Moreover, an association between long work hours and adverse health, e.g., CVD, subjectively reported physical health and subjective fatigue, has been observed, although not specifically in the EMS [Citation32].

4.1. Work-related factors

The participants in this study reported a high degree of physical demands (30%), heavy lifting (69%) and working in bending or awkward positions (63%). The lifting and carrying of stretchers is part of the physically demanding work, but there is also much heavy equipment, e.g., monitoring devices, defibrillators, emergency cases and oxygen equipment, that needs to be carried from the ambulance to the accident scene or into the patient’s home during every emergency call. Beside the loading and lifting of stretchers, carrying of equipment has previously been rated as the second most physically demanding task in the EMS [Citation33]. The physical demands have been described as the most frequent stressors in the EMS [Citation1], but there is less evidence on how much of the work time includes physically demanding work, to which this study adds information.

A statistically significant higher proportion of women reported physical demands and awkward or bending positions during work. Possible reasons explaining this could be that women have less muscle mass than men and therefore experience relatively higher physical demands than men do. However, our results also show that women performed better than men in the physical capacity tests. It is therefore possible to hypothesize that women in the EMS need to have better physical capacity in relation to other women to manage the physical demands during work in the EMS. Another aspect to consider is whether the equipment is fitted to men’s or women’s bodies, e.g., handles on stretchers or other equipment, and whether adjustments are possible if one member of the team is tall and another short [Citation17,Citation34].

It was common to report worries about threats and violence, and even more among women, which is in line with previous results from Australia [Citation35] and the USA [Citation36]. Compared to a Swedish study from 2007 [Citation37], the present study indicates an increase in being exposed to threats in this group. However, the proportion of personnel subjected to physical violence seems to be consistent with the results from 2007.

4.2. Lifestyle-related factors

The lifestyle factors reported by the ambulance personnel in this study differed compared to the Swedish population in general [Citation38], with more physical activity during leisure time and a lower level of smoking being reported among the ambulance personnel. In contrast to earlier findings [Citation10], the risk use of alcohol in the present study was very low.

It is interesting to note that more than 70% reported that the work schedule prevented them engaging in the leisure activities they wanted to take part in. The irregular work schedule could likely be an obstacle when wanting to participate in regular activities, e.g., on a specific day of the week. However, physical activity during leisure time seemed to be prioritized among the participants, since more than 75% reported moderate or vigorous physical activity during leisure time. One reason for this could be the need for high physical capacity due to the physical demands during work.

The prevalence of self-rated insomnia symptoms in this study is consistent with the results in a randomly selected sample of working-age participants in Sweden [Citation27], indicating that ambulance personnel do not have more symptoms of insomnia than the general population in Sweden. The high proportions of sleep problems and worries might be related to other occupational stressors present in the ambulance work, e.g., shift work [Citation39]. Previous research has described associations between sleeping problems and concern about work conditions among ambulance personnel in Sweden [Citation40]. Sterud et al. [Citation1] described severe occupational tasks, e.g., taking care of injured and dying patients, and the uncertainty of not knowing what will happen during the emergency call as among the most severe stressors in the ambulance work. Together with more general organizational stressors, e.g., lack of support by co-workers or managers, also described by Sterud et al. [Citation1], these might contribute to the sleep problems and worries among the personnel.

4.3. Health-related factors

The mean value regarding self-rated health in this study was 7.5 on a 10-point scale, indicating that the ambulance personnel rated their general health as good, which is in line with results from a Danish study [Citation13] where ambulance personnel rated their health higher than the general working population. Furthermore, the WAI was rated as good or very good by 87% of the participants in this study, consistent with results from a study including Swedish health-care workers [Citation41]. Self-rated health and the WAI have previously been shown to be strong predictors of sickness absence in general populations [Citation42,Citation43].

The finding that more than one out of four of the participants reported MSDs is consistent with previous studies including ambulance personnel, where even higher proportions of musculoskeletal complaints have been reported [Citation13,Citation17]. In this study there was no difference between women and men regarding reported MSDs. Self-reported mental health issues were higher among women than men, which contradicts the results from a Norwegian study where no difference was found between women and men regarding mental health and post-traumatic stress symptoms in the EMS [Citation44].

The objectively measured health factors, i.e., the anthropometric measures used to derive indicators of overweight and obesity, blood pressure, blood lipids, the risk of CVD and the test of physical capacity, add an additional dimension when describing work, lifestyle, and health among ambulance personnel. The high proportion of hypertension (45%) and of elevated blood lipids (high total cholesterol = 64%, high LDL-C = 64%) indicates that this is a group with increased risk of CVD, with a significantly higher risk among men according to SCORE. Previous research has observed a high proportion of prehypertension and hypertension among emergency responders [Citation45], and compared to the prevalence among the general population in Sweden [Citation46] the results from the present study show higher proportion of hypertension among ambulance personnel. Possible explanations for the high proportion of hypertension are, e.g., shift work, irregular physical exertion, sedentary work, emotional demands, unhealthy diet, noise exposure, post-traumatic stress disorders, high job demands and low control at work [Citation45,Citation47–49].

The proportion of overweight and obesity (64%), defined by the BMI, is higher in the present study than among the general adult population in Sweden, where the prevalence is about 50% [Citation50]. The waist circumference and waist–hip ratio are complements to the BMI to measure body fat distribution [Citation51]. There is conflicting evidence on whether any of these measurements are more strongly associated with CVD [Citation52]. However, it is interesting to reflect upon the differences between the prevalence of increased BMI (64%), increased waist circumference (50%) and increased waist–hip ratio (40%) among the participants in this study. One possible explanation for the difference is that the physically demanding work requires larger muscles, leading to increased BMI but without the same increase in the waist circumference and waist–hip ratio. There were also significant differences between women and men for all these measurements, with more women than men having a normal BMI and waist–hip ratio, while the opposite was seen for the waist circumference, with a higher proportion of normal measures among men. One possible explanation could be the need for larger core muscles to be able to meet all of the physical demands during work. Furthermore, the need for larger core muscles might be more important among women since they normally have less muscle mass than men [Citation51].

Another finding in the present study was that the women performed significantly better than men in aerobic capacity, hand strength and flexibility. One thing that might explain some of the differences regarding this is that the results of the participants’ aerobic capacity and hand strength were categorized with consideration of sex, i.e., women and men performing the same result were sometimes classified into different categories. One conclusion regarding this could be that female ambulance personnel in this study have high physical capacity compared to other women, but this high capacity is needed to be able to manage the demands of work.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Few previous studies among ambulance personnel have included data on work, lifestyle and health based on both self-reported and objective measures, which is a strength of the current study. Most previous studies have been based on self-reported data only [Citation1,Citation3,Citation9–11,Citation13]. Furthermore, the high response rate (67%) is a strength in this study. The sample size is comparable with most other studies carried out in the EMS setting. However, the difference in response rate between RNs and EMTs (79% vs 33%) might affect the possibility to generalize the results to all ambulance personnel. Moreover, we cannot exclude that ambulance personnel with higher health awareness participated to a higher degree in the study.

This was a cross-sectional study; it is therefore not possible to draw any causal conclusions from the results. More studies with longitudinal and intervention designs are needed to determine causality between exposures and outcomes. Moreover, it should be noted that the data collection was conducted in 2017. As the work environment in the EMS may have been altered since then, the findings might not directly reflect the current situation.

In Sweden, the National Board of Health and Welfare requires that every emergency ambulance should be staffed with at least one RN [Citation53]. This might be important to consider when comparing the results to other countries where the ambulances are staffed by other occupational groups.

The results in this study are presented as work-related, lifestyle-related or health-related factors. The distinction between these factors is not definite, i.e., many of the results could belong to both lifestyle and health, or work and lifestyle, etc.

The high proportion of hypertension indicates that this is a group with increased risk of CVD. However, this was based on a single blood pressure measurement at the occupational health service. To explore the prevalence of hypertension among ambulance personnel, the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring would be preferable since this has as stronger association with CVD than one single blood pressure measurement [Citation54].

5. Conclusions

The results from this study showed that the ambulance personnel were exposed to several work-related factors potentially harmful to health, both physical, e.g., heavy lifting, and psychosocial, e.g., risk of accidents, threats and violence. Still, many of the personnel had stayed for many years in the workplace, which might indicate that the work also included positive and rewarding aspects. The lifestyle-related factors showed that a high proportion of the personnel reported moderate or vigorous activity during leisure time, but also that the work schedule affected the ability to engage in the leisure activities they wanted. Fatigue as well as sleep problems and worries were common. The health-related factors were, to some extent, contradictory; on the one hand, there was high overall health, high WAI and high physical capacity, but on the other there were high proportions of risk factors for CVD, e.g., overweight, high blood pressure, and high level of blood lipids. Some important factors differed between women and men, e.g., regarding work demands, exposure to threats and violence, physical capacity, and risk factors for CVD.

Supplemental material.docx

Download MS Word (29.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the ambulance personnel who participated in this study. In addition, they thank the occupational health services, and the group who conducted the test of physical capacity, for their help during the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data and research materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2024.2332115.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [Citation55], and approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board of Linköping (Dnr 2016/482-31). Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants included in this study.

Data availability statement

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests regarding the data can be sent to the corresponding author.

References

- Sterud T, Hem E, Ekeberg O, et al. Occupational stressors and its organizational and individual correlates: a nationwide study of Norwegian ambulance personnel. BMC Emerg Med. 2008 Dec 2;8(16).

- Crowe RP, Krebs W, Cash RE, et al. Females and minority racial/ethnic groups remain underrepresented in emergency medical services: a ten-year assessment, 2008–2017. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):180–187. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1634167.

- van der Ploeg E, Kleber RJ. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: predictors of health symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(Suppl 1):i40–i46. doi:10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i40.

- Pourshaikhian M, Abolghasem Gorji H, Aryankhesal A, et al. A systematic literature review: workplace violence against emergency medical services personnel. Arch Trauma Res. 2016;5(1):e28734.

- Hegenberg K, Trentzsch H, Gross S, et al. Use of pre-hospital emergency medical services in urban and rural municipalities over a 10 year period: an observational study based on routinely collected dispatch data. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):35. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0607-5.

- The Swedish National Audit Office. Central government activities in ambulance services (RIR 2012:20). Stockholm: The Swedish National Audit Office; 2012.

- Anstey S, Tweedie J, Lord B. Qualitative study of Queensland paramedics’ perceived influences on their food and meal choices during shift work. Nutr Diet. 2016;73(1):43–49. doi:10.1111/1747-0080.12237.

- Nocon M, Hiemann T, Muller-Riemenschneider F, et al. Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15(3):239–246. doi:10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f55e09.

- Betlehem J, Horvath A, Jeges S, et al. How healthy are ambulance personnel in Central Europe? Eval Health Prof. 2014;37(3):394–406. doi:10.1177/0163278712472501.

- Donnelly E. Work-related stress and posttraumatic stress in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(1):76–85. doi:10.3109/10903127.2011.621044.

- Hegg-Deloye S, Brassard P, Prairie J, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in paramedics. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(7):973–980. doi:10.1007/s00420-015-1028-z.

- Karlsson K, Nasic S, Lundberg L, et al. Health problems among Swedish ambulance personnel: long-term risks compared to other professions in Sweden – a longitudinal register study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2022;28(2):1130–1135. doi:10.1080/10803548.2020.1867400.

- Hansen Claus D, Rasmussen K, Kyed M, et al. Physical and psychosocial work environment factors and their association with health outcomes in Danish ambulance personnel – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):534. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-534.

- Jenkins N, Smith G, Stewart S, et al. Pre-employment physical capacity testing as a predictor for musculoskeletal injury in paramedics: a review of the literature. Work. 2016;55(3):565–575.

- Hegg-Deloye S, Brassard P, Jauvin N, et al. Current state of knowledge of post-traumatic stress, sleeping problems, obesity and cardiovascular disease in paramedics. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(3):242–247. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201672.

- Svensson A, Fridlund B. Experiences of and actions towards worries among ambulance nurses in their professional life: a critical incident study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2008;16(1):35–42. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2007.10.002.

- Aasa U, Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Angquist KA, et al. Relationships between work-related factors and disorders in the neck–shoulder and low-back region among female and male ambulance personnel. J Occup Health. 2005;47(6):481–489. doi:10.1539/joh.47.481.

- Nysam. Ambulanssjukvård nyckeltal. 2016. Stockholm: Helseplan Nysam AB; 2017.

- Hogan J. Structure of physical performance in occupational tasks. J Appl Psychol. 1991;76(4):495–507. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.495.

- Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Aasa U, Ängquist KA, et al. Prediction of development of fatigue during a simulated ambulance work task from physical performance tests. Ergonomics. 2004;47(11):1238–1250. doi:10.1080/00140130410001714751.

- Alfredsson L, Hammar N, Fransson E, et al. Job strain and major risk factors for coronary heart disease among employed males and females in a Swedish study on work, lipids and fibrinogen. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(4):238–248. doi:10.5271/sjweh.671.

- Sanne B, Torp S, Mykletun A, et al. The Swedish demand–control–support questionnaire (DCSQ): factor structure, item analyses, and internal consistency in a large population. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(3):166–174. doi:10.1080/14034940410019217.

- Siegrist J, Li J, Montano D. Psychometric properties of the effort–reward imbalance questionnaire. Duesseldorf: Department of Medical Sociology, Faculty of Medicine, Duesseldorf University; 2014.

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Håkansson C, Wagman P, Hagell P. Construct validity of a revised version of the occupational balance questionnaire. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(6):441–449.

- Gustafsson K, Lindfors P, Aronsson G, et al. Relationships between self-rating of recovery from work and morning salivary cortisol. J Occup Health. 2008;50(1):24–30. doi:10.1539/joh.50.24.

- Broman JE, Smedje H, Mallon L, et al. The minimal insomnia symptom scale (MISS): a brief measure of sleeping difficulties. Ups J Med Sci. 2008;113(2):131–142. doi:10.3109/2000-1967-221.

- Ilmarinen J. The work ability index (WAI). Occup Med. 2007;57(2):160. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqm008.

- Granter E, Wankhade P, McCann L, et al. Multiple dimensions of work intensity: ambulance work as edgework. Work Employ Soc. 2019;33(2):280–297. doi:10.1177/0950017018759207.

- Statistics Sweden. The Swedish occupational register 2017 [electronic resource]. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån; 2019.

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Chrzan K, et al. The impact of working overtime or multiple jobs in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(5):657–664. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1695301.

- van der Hulst M. Long workhours and health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29(3):171–188. doi:10.5271/sjweh.720.

- Coffey B, Macphee R, Socha D, et al. A physical demands description of paramedic work in Canada. Int J Ind Ergon. 2016;53:355–362. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2016.04.005.

- Fischer SL, Sinden KE, MacPhee RS. Identifying the critical physical demanding tasks of paramedic work: towards the development of a physical employment standard. Appl Ergon. 2017;65:233–239. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2017.06.021.

- Maguire BJ. Violence against ambulance personnel: a retrospective cohort study of national data from Safe Work Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 2018;28(1):e28011805. doi:10.17061/phrp28011805.

- Maguire BJ, Smith S. Injuries and fatalities among emergency medical technicians and paramedics in the United States. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28(4):376–382. doi:10.1017/S1049023X13003555.

- Petzäll K, Tällberg J, Lundin T, et al. Threats and violence in the Swedish pre-hospital emergency care. Int Emerg Nurs. 2011;19(1):5–11. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2010.01.004.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Folkhälsans utveckling – Årsrapport 2018 [Development of the public health – annual report 2018]. Solna: Public Health Agency of Sweden; 2018.

- Sallinen M, Kecklund G. Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness – differences between shift schedules and systems. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;2:121–133. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2900.

- Aasa U, Brulin C, Ängquist K-A, et al. Work-related psychosocial factors, worry about work conditions and health complaints among female and male ambulance personnel. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19(3):251–258. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00333.x.

- Arvidson E, Börjesson M, Ahlborg G, et al. The level of leisure time physical activity is associated with work ability – a cross sectional and prospective study of health care workers. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):855. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-855.

- Halford C, Wallman T, Welin L, et al. Effects of self-rated health on sick leave, disability pension, hospital admissions and mortality. A population-based longitudinal study of nearly 15,000 observations among Swedish women and men. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1103. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1103.

- Lundin A, Leijon O, Vaez M, et al. Predictive validity of the work ability index and its individual items in the general population. Scand J Public Health. 2017;45(4):350–356. doi:10.1177/1403494817702759.

- Reid BO, Næss-Pleym LE, Bakkelund KE, et al. A cross-sectional study of mental health-, posttraumatic stress symptoms and post exposure changes in Norwegian ambulance personnel. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2022;30(1):3–3.

- Kales SN, Tsismenakis AJ, Zhang C, et al. Blood pressure in firefighters, police officers, and other emergency responders. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(1):11–20. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.296.

- Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–980. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1.

- Parsons IT, Nicol ED, Holdsworth D, et al. Cardiovascular risk in high-hazard occupations: the role of occupational cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(4):702–713.

- Kivimaki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;380(9852):1491–1497. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5.

- Puttonen S, Harma M, Hublin C. Shift work and cardiovascular disease – pathways from circadian stress to morbidity. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36(2):96–108. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2894.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. Folkhälsans utveckling – Årsrapport 2019 [Development of the public health – annual report 2019]. Solna: Public Health Agency of Sweden; 2019.

- World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio. Report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Huxley R, Mendis S, Zheleznyakov E, et al. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk – a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(1):16–22. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.68.

- Suserud BO. A new profession in the pre-hospital care field – the ambulance nurse. Nurs Crit Care. 2005;10(6):269–271. doi:10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00129.x.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. World Medical Association; 2013.